User login

Elective laparoscopic appendectomy in gynecologic surgery: When, why, and how

Videos provided by Teresa Tam, MD, and Gerald Harkins, MD

CASE: Should appendectomy be included in total

laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A 39-year-old mother of two continues to experience severe dysmenorrhea and persistent menorrhagia despite undergoing endometrial ablation 2 years earlier. Her obstetric and gynecologic history is remarkable for a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and failed endometrial ablation. Both her children were delivered by cesarean, and she has undergone tubal ligation. She requests hysterectomy to address the dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia once and for all.

A pelvic exam reveals an anteverted, 10-weeks’ size uterus with no adnexal masses or tenderness. After extensive discussion of the surgical procedure, the patient signs a consent for total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Would you recommend appendectomy, too?

Prophylactic removal of the appendix during a benign gynecologic procedure is known as “elective incidental appendectomy.”1 Incidental appendectomy at the time of cesarean delivery was reported initially in 1959.2 Subsequent studies of removal of a normal-appearing appendix at the time of gynecologic surgery have met with considerable debate. Proponents argue that removal of the appendix at the time of abdominal hysterectomy does not increase operative time or postoperative morbidity. More important, it does prevent future appendicitis.3-5

Some surgeons disagree, citing an increase in operative time, hospital costs, and patient morbidity as reasonable concerns. They also note that appendectomy requires an additional surgical procedure, which could increase the risk of infection and other complications and lead to adhesion formation.

Advantages of incidental appendectomy include technical ease, low patient morbidity and mortality, and significant diagnostic and protective value.6 It also prevents conflicting diagnoses, especially in patients who have chronic pelvic pain, a ruptured ovarian cyst, or endometriosis. Other patients likely to benefit from elective incidental appendectomy are those who are undergoing abdominal radiation or chemotherapy, women unable to communicate health complaints, and those who are planning to undergo complex abdominal or pelvic procedures that are likely to cause extensive adhesions.1

In this article, we describe the rationale behind this procedure, as well as the technical steps involved.

The laparoscopic approach is preferred

Appendectomy is commonly performed laparoscopically. Semm first described this approach in 1983.7 Several studies since have reported that incidental laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, easy to perform, and should be offered to patients undergoing a concomitant gynecologic procedure.8-10 Laparoscopic removal of a normal appendix does not add morbidity or prolong hospitalization, compared with diagnostic laparoscopy. A large study drawing from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database found laparoscopic removal of the appendix to be associated with lower mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and lower mean hospital charges, compared with open appendectomy.11 The same study found laparoscopic appendectomy to be the procedure of choice in both perforated and nonperforated appendicitis.

Overweight and obese patients also may benefit from the laparoscopic approach because it avoids problems associated with an open incision, such as the need for abdominal wall retraction, a longer hospital stay, and a risk of wound infection, compared with smaller incisions—especially in this high-risk population.12

Cost is another issue. Any prolonged surgical time and higher medical costs required for incidental appendectomy decrease as surgical proficiency and experience rise. The concomitant performance of endoscopic procedures can also reduce the risk associated with anesthesia for reoperations.

Endometriosis patients stand to benefit from appendectomy

There is compelling evidence that elective appendectomy is beneficial in patients who have endometriosis. Endometriosis of the bowel has been reported in 5.3% of all histologically proven endometriosis cases, with appendiceal endometriosis found in approximately 1% of women with endometriosis.13 Despite the low prevalence (2.8%) of appendiceal endometriosis,14 some studies reported a high incidence of appendiceal endometriosis when incidental appendectomy was performed. Patients who report right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, chronic pelvic pain, and ovarian endometrioma had the highest incidence of abnormal histopathologic findings.15-17 Because most women with endometriosis present with these symptoms, it is prudent to counsel patients preoperatively about the incidence of appendiceal endometriosis and to visually examine the appendix during gynecologic surgery to identify incidental appendiceal pathology.

Age may influence the appendectomy decision

The incidence of acute appendicitis is highest among people aged 10 to 19 years. The estimated lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6.7%.18 The surgical dilemma is whether to perform incidental appendectomy in the nonadolescent population, which is at lower risk for appendicitis, as a preventive measure.

We lack randomized trials on the benefit of incidental appendectomy. A retrospective study of open procedures supported incidental appendectomy in patients younger than 35 years; for patients 35 to 50, the decision was left to the clinical judgment of the surgeon, based on the patient’s clinical condition.4 The same study failed to support incidental appendectomy in women older than 50 years.

When the appendix is not easily accessible, or the surgical complexity of the gynecologic procedure prevents the surgeon from safely performing an appendectomy, it is better to complete the planned gynecologic surgery and forgo the appendectomy. It is acceptable to make the decision to refrain from the appendectomy intraoperatively if the risk of complications outweighs the likely benefits. The practice of cautionary discretion demonstrates sound judgment and avoids compromising the safety of the patient.

1. Maintain at least three laparoscopic sites

- After the laparoscopic gynecologic procedure, maintain three trocar sites—preferably, two 5-mm trocars and one 12-mm trocar.

- The first 5-mm trocar, at the umbilical incision, accommodates the laparoscopic camera. The second 5-mm trocar serves as an accessory port for laparoscopic instruments and is inserted into the RLQ.

- The 12-mm trocar in the left lower quadrant (LLQ) is also used to insert endoscopic instruments. This trocar site will be used at the conclusion of the appendectomy to accommodate the mechanical stapling device and the specimen bag for removal of the excised organ.

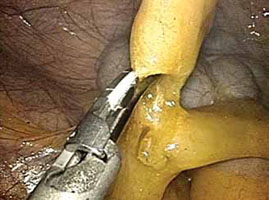

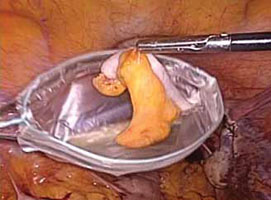

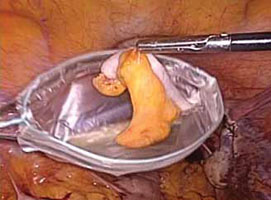

FIGURE 1: Visualize the appendix. Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix.

2. Identify the appendix

- Perform a careful visual exploration of the abdominal contents to exclude other intra-abdominal pathology.

- Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix (FIGURE 1).

- Visually inspect the appendix and identify any gross appendiceal pathology.

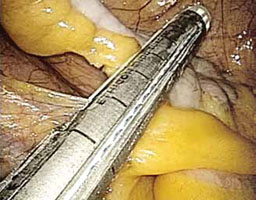

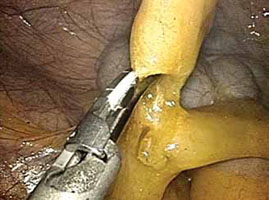

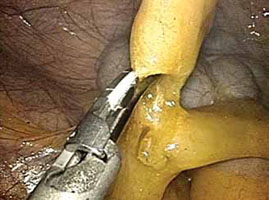

FIGURE 2: Divide the mesoappendix

Isolate, cauterize, and divide the mesoappendix using 5-mm ultrasonic shears.

3. Dissect the appendix (VIDEO 1)

- Insert an atraumatic forceps through the 5-mm right accessory trocar.

- Grasp the fatty tissue at the tip of the appendix and provide some traction.

- Elevate the appendix to facilitate visualization of the mesoappendix.

- Isolate the mesoappendix and cauterize and divide it using 5-mm ultrasonic shears inserted through the RLQ trocar (FIGURE 2).

- Release some of the upward tension from the specimen retraction by dropping the height of the instrument to prevent undue trauma and bleeding.

- Make a window between the mesentery and the base of the appendix to facilitate dissection.

- Skeletonize the mesoappendix at the junction of the appendiceal base and the cecum.

- During skeletonization, pay special attention to the appendiceal artery at the base of the mesoappendix.

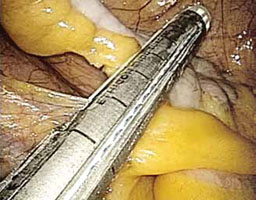

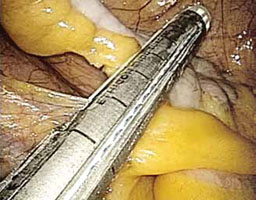

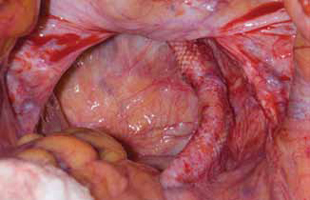

FIGURE 3: Apply the stapling device

Apply the stapling device across the base of the appendix.

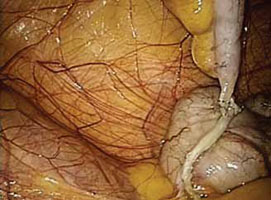

4. Resect the appendix (VIDEO 2)

- Insert an automatic stapling device through the 12-mm port and apply it across the base of the appendix (FIGURE 3).

- Apply the mechanical stapling device for 15 seconds to crush the base of the appendix and empty its contents.

- Visualize both sides of the stapler to ensure that it is placed at the base of the appendix.

- Always check the tip of the device to ensure that the jaws of the stapling device fully compress the appendix and have not inadvertently grasped other abdominal contents.

- With the stapling device compressing the base of the appendix, release some of the upward tension on the specimen by dropping the height of the retraction.

- Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base

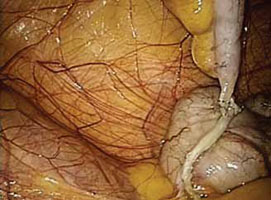

(FIGURE 4). - Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump to ensure hemostasis (FIGURE 5).

FIGURE 4: Excise the appendix

Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base.

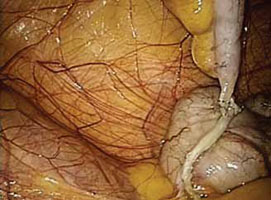

FIGURE 5: Ensure hemostasis

Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump and ensure hemostasis.

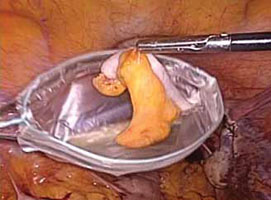

5. Remove the specimen (VIDEO 3)

- Remove the stapling device and replace it with a specimen retrieval bag, inserting it through the 12-mm port.

- Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag to prevent abdominal contamination (FIGURE 6).

- Close the specimen retrieval bag inside the abdomen.

- Refrain from removing the specimen bag through the trocar or forcefully passing the appendix through a small incision. We usually withdraw the 12-mm trocar, then remove the cinched bag containing the resected appendix under direct visualization. We take all precautionary measures to prevent breakage of the bag, which would leak appendiceal contents into the abdomen.

FIGURE 6: Remove the specimen

Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag and remove it, intact, through the patient’s abdomen.

6. Perform a few last measures

- If the surgeon chooses, suction and irrigation can be performed at the completion of the appendectomy procedure.

- Send all surgical specimens to pathology for evaluation.

- Complete the operation in the usual laparoscopic fashion. Remove all instruments, and close the 12-mm trocar port site using the Carter Thomason fascial closure device. Close the remaining port sites using 2-0 interrupted suture (Monocryl). Apply skin adhesive to all laparoscopic incisions.

- For more on surgical technique of appendectomy, see Baggish,19 Jaffe and Berger,20 and Daniell and colleagues.21

Coding for appendectomy is fairly straightforward if you know the rules, but prophylactic removal of the appendix, whether performed at the time of a laparoscopic or open abdominal primary procedure, will usually lead to reimbursement difficulties for surgeons even though CPT codes exist to report the procedure. Knowing when and how to bill and document the circumstances for removal will go a long way in getting payment for the procedure. Note that these rules apply to a single surgeon who is performing the entire surgery. When an ObGyn is performing gyn procedures, but a general surgeon is the one who removes the appendix, that surgeon will not be subject to bundling rules, but will still have to make a case with the payer for removing an otherwise normal appendix.

There are 5 codes that can be used to report an appendectomy:

- 44950 Appendectomy;

- 44955 Appendectomy; when done for indicated purpose at time of other major procedure (not as separate procedure)

- 44960 Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis

- 44970 Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy code

- 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Code 44950 represents either a stand-alone procedure or an incidental appendectomy when performed with other open abdominal procedures. Under CPT guidelines this code would only be reported 1) when this is the only procedure performed and the appendix is removed for a diagnosis other than rupture with abscess, or 2) with a modifier -52 added if the surgeon believes that an incidental appendectomy needs to be reported. Use of a modifier -52 will lead to review of the documentation by the payer, and it will be up to the surgeon to convince the payer that he should be paid for taking out an appendix that is found to be normal. Billing 44950 with other abdominal procedures without this modifier will lead to an outright denial due to bundling edits, which permanently bundle 44950 with all major abdominal procedures.

Code 44955 is the code to report when an appendectomy is performed for an indicated purpose at the time of other open abdominal procedures. For instance, the appendix may have been removed due to a finding of distention with fecalith or extensive adhesions binding the appendix to the abdominal wall. When this code is reported, no modifier is used because it is a CPT “add-on” code that can only be billed in conjunction with other procedures.

Code 44960 is only reported when no other open abdominal procedures are performed at the operative session and the reason for taking out the appendix is rupture with abscess. If rupture is found at the time of an abdominal procedure to remove a mass, for instance, code 44955 would be reported instead.

Code 44970 is the only laparoscopic approach code for an appendectomy, but it would only be reported when 1) the appendectomy was the only laparoscopic procedure performed, or 2) the appendectomy was incidental, but the surgeon felt it needed to be reported. There is no instruction about using a modifier -52 with 44970 to report an incidental appendectomy. According to the American Medical Association’s January 2012 issue of CPT Assistant, laparoscopic removal of the appendix for an indicated purpose at the time of another major laparoscopic procedure should be reported as 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Keep in mind that code 44970 is bundled into a long list of laparoscopic procedures, including codes for treating stress urinary incontinence and prolapse (CPT codes 51990–51992, 57425), sterilization procedures (CPT codes 58670–58671), hysterectomy procedures (CPT codes 58541–58544, 58548, 58550–58554, 58570–58573), myomectomy procedures (CPT code 58545–58546), as well as codes for lysis, removal of lesions and ovaries, or aspiration of lesions (CPT codes 49321–49322, 58660–58662). A modifier -59 (Distinct Procedural Service) can be reported to bypass these edits, but the payer will request documentation to ensure that the criteria for using this modifier apply. The CPT criteria include documentation of a different session, different procedure or surgery, different site or organ system, separate incision/excision, separate lesion, or separate injury (or area of injury in extensive injuries) which is not ordinarily encountered or performed on the same day by the same individual. Failure to discuss the reason for the removal in the body of the operative report will generally mean the payer will deny extra payment for the appendectomy.

—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Adequate training is essential

Surgical proficiency in laparoscopic appendectomy, like any surgical skill set, requires adequate training to ensure procedural familiarity and expertise and to encourage consistency. This training, preferably undertaken during residency, should be an essential part of obstetrics and gynecology education.

It is important to know which patient populations are at high risk for appendiceal pathology so that they can be assessed and counseled adequately prior to surgery. Among the components of patient counseling is a thorough and impartial discussion of procedural risks and benefits. Risk-benefit considerations should include the patient’s preferences so that she can be an active participant in her own health-care decisions.

Because the risks of appendectomy are minimal, and complications are rare, it is appropriate to offer elective laparoscopic appendectomy to patients scheduled to undergo benign gynecologic procedures, especially in the setting of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis.

CASE: Resolved

The patient is counseled about the benefits and risks of laparoscopic incidental appendectomy, including the fact that it may be especially beneficial in women who have endometriosis. She consents to undergo the procedure at the time of her total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Both procedures are performed safely, with no complications, and the patient’s immediate postoperative course is unremarkable. After one night of hospitalization, she is discharged home. The histopathologic report on the appendiceal specimen reveals endometriosis with fibrous obliteration of the lumen.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access 8 Surgical Technique articles published in OBG Management

in 2012.

1. Elective coincidental appendectomy. ACOG Committee Opinion#323. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1141-1142.

2. Davis ME. Gynecologic operations at cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1959;2:1095-1106.

3. Lynch CB, Sinha P, Jalloh S. Incidental appendectomy during gynecological surgery. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):261-262.

4. Snyder TE, Selanders JR. Incidental appendectomy—yes or no? A retrospective case study and review of the literature. Infec Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1998;6(1):30-37.

5. Salom EM, Schey D, Penalver M, et al. The safety of incidental appendectomy at the time of abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1563-1568.

6. Lee JH, Choi JS, Jeon SW. Laparoscopic incidental appendectomy during laparoscopic surgery for ovarian endometrioma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):28.e1-5.

7. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15(2):59-64.

8. O’Hanlan KA, Fisher DT, O’Holleran MS. 257 incidental appendectomies during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. JSLS. 2007;11(4):428-431.

9. Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Incidental appendectomy during videolaseroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(3):559-564.

10. Song JY, Yordan E, Rotman C. Incidental appendectomy during endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2009;13(3):376-383.

11. Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006-2008. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(12):2226-2231.

12. Jarnagin BK. The vermiform appendix in relation to gynecology. In: Rock JA Jones HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Chapter 42. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

13. Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(5):727-730.

14. Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, Stratton P. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(2):298-303.

15. Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, Marziali M, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):206-209.

16. Harris RS, Foster WG, Surrey MW, Agarwal SK. Appendiceal disease in women with endometriosis and right lower quadrant pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):536-541.

17. Wie HJ, Lee JH, Kyung MS, Jung US, Choi JS. Is incidental appendectomy necessary in women with ovarian endometrioma? Aust NZ J Obstet Gyn. 2008;48(1):107-111.

18. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

19. Baggish MS. Appendectomy. In: Baggish MS Karram MM, eds. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Chapter 100. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2006.

20. Jaffe BM, Berger DH. The appendix. In: Brunicardi F Andersen D, Billiar T, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. Chapter 30. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

21. Daniell JF, Gurley LD, Kurtz BR, Chamber JF. The use of an automatic stapling device for laparoscopic appendectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78(4):721-723.

Videos provided by Teresa Tam, MD, and Gerald Harkins, MD

CASE: Should appendectomy be included in total

laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A 39-year-old mother of two continues to experience severe dysmenorrhea and persistent menorrhagia despite undergoing endometrial ablation 2 years earlier. Her obstetric and gynecologic history is remarkable for a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and failed endometrial ablation. Both her children were delivered by cesarean, and she has undergone tubal ligation. She requests hysterectomy to address the dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia once and for all.

A pelvic exam reveals an anteverted, 10-weeks’ size uterus with no adnexal masses or tenderness. After extensive discussion of the surgical procedure, the patient signs a consent for total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Would you recommend appendectomy, too?

Prophylactic removal of the appendix during a benign gynecologic procedure is known as “elective incidental appendectomy.”1 Incidental appendectomy at the time of cesarean delivery was reported initially in 1959.2 Subsequent studies of removal of a normal-appearing appendix at the time of gynecologic surgery have met with considerable debate. Proponents argue that removal of the appendix at the time of abdominal hysterectomy does not increase operative time or postoperative morbidity. More important, it does prevent future appendicitis.3-5

Some surgeons disagree, citing an increase in operative time, hospital costs, and patient morbidity as reasonable concerns. They also note that appendectomy requires an additional surgical procedure, which could increase the risk of infection and other complications and lead to adhesion formation.

Advantages of incidental appendectomy include technical ease, low patient morbidity and mortality, and significant diagnostic and protective value.6 It also prevents conflicting diagnoses, especially in patients who have chronic pelvic pain, a ruptured ovarian cyst, or endometriosis. Other patients likely to benefit from elective incidental appendectomy are those who are undergoing abdominal radiation or chemotherapy, women unable to communicate health complaints, and those who are planning to undergo complex abdominal or pelvic procedures that are likely to cause extensive adhesions.1

In this article, we describe the rationale behind this procedure, as well as the technical steps involved.

The laparoscopic approach is preferred

Appendectomy is commonly performed laparoscopically. Semm first described this approach in 1983.7 Several studies since have reported that incidental laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, easy to perform, and should be offered to patients undergoing a concomitant gynecologic procedure.8-10 Laparoscopic removal of a normal appendix does not add morbidity or prolong hospitalization, compared with diagnostic laparoscopy. A large study drawing from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database found laparoscopic removal of the appendix to be associated with lower mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and lower mean hospital charges, compared with open appendectomy.11 The same study found laparoscopic appendectomy to be the procedure of choice in both perforated and nonperforated appendicitis.

Overweight and obese patients also may benefit from the laparoscopic approach because it avoids problems associated with an open incision, such as the need for abdominal wall retraction, a longer hospital stay, and a risk of wound infection, compared with smaller incisions—especially in this high-risk population.12

Cost is another issue. Any prolonged surgical time and higher medical costs required for incidental appendectomy decrease as surgical proficiency and experience rise. The concomitant performance of endoscopic procedures can also reduce the risk associated with anesthesia for reoperations.

Endometriosis patients stand to benefit from appendectomy

There is compelling evidence that elective appendectomy is beneficial in patients who have endometriosis. Endometriosis of the bowel has been reported in 5.3% of all histologically proven endometriosis cases, with appendiceal endometriosis found in approximately 1% of women with endometriosis.13 Despite the low prevalence (2.8%) of appendiceal endometriosis,14 some studies reported a high incidence of appendiceal endometriosis when incidental appendectomy was performed. Patients who report right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, chronic pelvic pain, and ovarian endometrioma had the highest incidence of abnormal histopathologic findings.15-17 Because most women with endometriosis present with these symptoms, it is prudent to counsel patients preoperatively about the incidence of appendiceal endometriosis and to visually examine the appendix during gynecologic surgery to identify incidental appendiceal pathology.

Age may influence the appendectomy decision

The incidence of acute appendicitis is highest among people aged 10 to 19 years. The estimated lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6.7%.18 The surgical dilemma is whether to perform incidental appendectomy in the nonadolescent population, which is at lower risk for appendicitis, as a preventive measure.

We lack randomized trials on the benefit of incidental appendectomy. A retrospective study of open procedures supported incidental appendectomy in patients younger than 35 years; for patients 35 to 50, the decision was left to the clinical judgment of the surgeon, based on the patient’s clinical condition.4 The same study failed to support incidental appendectomy in women older than 50 years.

When the appendix is not easily accessible, or the surgical complexity of the gynecologic procedure prevents the surgeon from safely performing an appendectomy, it is better to complete the planned gynecologic surgery and forgo the appendectomy. It is acceptable to make the decision to refrain from the appendectomy intraoperatively if the risk of complications outweighs the likely benefits. The practice of cautionary discretion demonstrates sound judgment and avoids compromising the safety of the patient.

1. Maintain at least three laparoscopic sites

- After the laparoscopic gynecologic procedure, maintain three trocar sites—preferably, two 5-mm trocars and one 12-mm trocar.

- The first 5-mm trocar, at the umbilical incision, accommodates the laparoscopic camera. The second 5-mm trocar serves as an accessory port for laparoscopic instruments and is inserted into the RLQ.

- The 12-mm trocar in the left lower quadrant (LLQ) is also used to insert endoscopic instruments. This trocar site will be used at the conclusion of the appendectomy to accommodate the mechanical stapling device and the specimen bag for removal of the excised organ.

FIGURE 1: Visualize the appendix. Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix.

2. Identify the appendix

- Perform a careful visual exploration of the abdominal contents to exclude other intra-abdominal pathology.

- Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix (FIGURE 1).

- Visually inspect the appendix and identify any gross appendiceal pathology.

FIGURE 2: Divide the mesoappendix

Isolate, cauterize, and divide the mesoappendix using 5-mm ultrasonic shears.

3. Dissect the appendix (VIDEO 1)

- Insert an atraumatic forceps through the 5-mm right accessory trocar.

- Grasp the fatty tissue at the tip of the appendix and provide some traction.

- Elevate the appendix to facilitate visualization of the mesoappendix.

- Isolate the mesoappendix and cauterize and divide it using 5-mm ultrasonic shears inserted through the RLQ trocar (FIGURE 2).

- Release some of the upward tension from the specimen retraction by dropping the height of the instrument to prevent undue trauma and bleeding.

- Make a window between the mesentery and the base of the appendix to facilitate dissection.

- Skeletonize the mesoappendix at the junction of the appendiceal base and the cecum.

- During skeletonization, pay special attention to the appendiceal artery at the base of the mesoappendix.

FIGURE 3: Apply the stapling device

Apply the stapling device across the base of the appendix.

4. Resect the appendix (VIDEO 2)

- Insert an automatic stapling device through the 12-mm port and apply it across the base of the appendix (FIGURE 3).

- Apply the mechanical stapling device for 15 seconds to crush the base of the appendix and empty its contents.

- Visualize both sides of the stapler to ensure that it is placed at the base of the appendix.

- Always check the tip of the device to ensure that the jaws of the stapling device fully compress the appendix and have not inadvertently grasped other abdominal contents.

- With the stapling device compressing the base of the appendix, release some of the upward tension on the specimen by dropping the height of the retraction.

- Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base

(FIGURE 4). - Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump to ensure hemostasis (FIGURE 5).

FIGURE 4: Excise the appendix

Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base.

FIGURE 5: Ensure hemostasis

Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump and ensure hemostasis.

5. Remove the specimen (VIDEO 3)

- Remove the stapling device and replace it with a specimen retrieval bag, inserting it through the 12-mm port.

- Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag to prevent abdominal contamination (FIGURE 6).

- Close the specimen retrieval bag inside the abdomen.

- Refrain from removing the specimen bag through the trocar or forcefully passing the appendix through a small incision. We usually withdraw the 12-mm trocar, then remove the cinched bag containing the resected appendix under direct visualization. We take all precautionary measures to prevent breakage of the bag, which would leak appendiceal contents into the abdomen.

FIGURE 6: Remove the specimen

Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag and remove it, intact, through the patient’s abdomen.

6. Perform a few last measures

- If the surgeon chooses, suction and irrigation can be performed at the completion of the appendectomy procedure.

- Send all surgical specimens to pathology for evaluation.

- Complete the operation in the usual laparoscopic fashion. Remove all instruments, and close the 12-mm trocar port site using the Carter Thomason fascial closure device. Close the remaining port sites using 2-0 interrupted suture (Monocryl). Apply skin adhesive to all laparoscopic incisions.

- For more on surgical technique of appendectomy, see Baggish,19 Jaffe and Berger,20 and Daniell and colleagues.21

Coding for appendectomy is fairly straightforward if you know the rules, but prophylactic removal of the appendix, whether performed at the time of a laparoscopic or open abdominal primary procedure, will usually lead to reimbursement difficulties for surgeons even though CPT codes exist to report the procedure. Knowing when and how to bill and document the circumstances for removal will go a long way in getting payment for the procedure. Note that these rules apply to a single surgeon who is performing the entire surgery. When an ObGyn is performing gyn procedures, but a general surgeon is the one who removes the appendix, that surgeon will not be subject to bundling rules, but will still have to make a case with the payer for removing an otherwise normal appendix.

There are 5 codes that can be used to report an appendectomy:

- 44950 Appendectomy;

- 44955 Appendectomy; when done for indicated purpose at time of other major procedure (not as separate procedure)

- 44960 Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis

- 44970 Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy code

- 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Code 44950 represents either a stand-alone procedure or an incidental appendectomy when performed with other open abdominal procedures. Under CPT guidelines this code would only be reported 1) when this is the only procedure performed and the appendix is removed for a diagnosis other than rupture with abscess, or 2) with a modifier -52 added if the surgeon believes that an incidental appendectomy needs to be reported. Use of a modifier -52 will lead to review of the documentation by the payer, and it will be up to the surgeon to convince the payer that he should be paid for taking out an appendix that is found to be normal. Billing 44950 with other abdominal procedures without this modifier will lead to an outright denial due to bundling edits, which permanently bundle 44950 with all major abdominal procedures.

Code 44955 is the code to report when an appendectomy is performed for an indicated purpose at the time of other open abdominal procedures. For instance, the appendix may have been removed due to a finding of distention with fecalith or extensive adhesions binding the appendix to the abdominal wall. When this code is reported, no modifier is used because it is a CPT “add-on” code that can only be billed in conjunction with other procedures.

Code 44960 is only reported when no other open abdominal procedures are performed at the operative session and the reason for taking out the appendix is rupture with abscess. If rupture is found at the time of an abdominal procedure to remove a mass, for instance, code 44955 would be reported instead.

Code 44970 is the only laparoscopic approach code for an appendectomy, but it would only be reported when 1) the appendectomy was the only laparoscopic procedure performed, or 2) the appendectomy was incidental, but the surgeon felt it needed to be reported. There is no instruction about using a modifier -52 with 44970 to report an incidental appendectomy. According to the American Medical Association’s January 2012 issue of CPT Assistant, laparoscopic removal of the appendix for an indicated purpose at the time of another major laparoscopic procedure should be reported as 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Keep in mind that code 44970 is bundled into a long list of laparoscopic procedures, including codes for treating stress urinary incontinence and prolapse (CPT codes 51990–51992, 57425), sterilization procedures (CPT codes 58670–58671), hysterectomy procedures (CPT codes 58541–58544, 58548, 58550–58554, 58570–58573), myomectomy procedures (CPT code 58545–58546), as well as codes for lysis, removal of lesions and ovaries, or aspiration of lesions (CPT codes 49321–49322, 58660–58662). A modifier -59 (Distinct Procedural Service) can be reported to bypass these edits, but the payer will request documentation to ensure that the criteria for using this modifier apply. The CPT criteria include documentation of a different session, different procedure or surgery, different site or organ system, separate incision/excision, separate lesion, or separate injury (or area of injury in extensive injuries) which is not ordinarily encountered or performed on the same day by the same individual. Failure to discuss the reason for the removal in the body of the operative report will generally mean the payer will deny extra payment for the appendectomy.

—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Adequate training is essential

Surgical proficiency in laparoscopic appendectomy, like any surgical skill set, requires adequate training to ensure procedural familiarity and expertise and to encourage consistency. This training, preferably undertaken during residency, should be an essential part of obstetrics and gynecology education.

It is important to know which patient populations are at high risk for appendiceal pathology so that they can be assessed and counseled adequately prior to surgery. Among the components of patient counseling is a thorough and impartial discussion of procedural risks and benefits. Risk-benefit considerations should include the patient’s preferences so that she can be an active participant in her own health-care decisions.

Because the risks of appendectomy are minimal, and complications are rare, it is appropriate to offer elective laparoscopic appendectomy to patients scheduled to undergo benign gynecologic procedures, especially in the setting of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis.

CASE: Resolved

The patient is counseled about the benefits and risks of laparoscopic incidental appendectomy, including the fact that it may be especially beneficial in women who have endometriosis. She consents to undergo the procedure at the time of her total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Both procedures are performed safely, with no complications, and the patient’s immediate postoperative course is unremarkable. After one night of hospitalization, she is discharged home. The histopathologic report on the appendiceal specimen reveals endometriosis with fibrous obliteration of the lumen.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access 8 Surgical Technique articles published in OBG Management

in 2012.

Videos provided by Teresa Tam, MD, and Gerald Harkins, MD

CASE: Should appendectomy be included in total

laparoscopic hysterectomy?

A 39-year-old mother of two continues to experience severe dysmenorrhea and persistent menorrhagia despite undergoing endometrial ablation 2 years earlier. Her obstetric and gynecologic history is remarkable for a diagnosis of chronic pelvic pain, endometriosis, and failed endometrial ablation. Both her children were delivered by cesarean, and she has undergone tubal ligation. She requests hysterectomy to address the dysmenorrhea and menorrhagia once and for all.

A pelvic exam reveals an anteverted, 10-weeks’ size uterus with no adnexal masses or tenderness. After extensive discussion of the surgical procedure, the patient signs a consent for total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Would you recommend appendectomy, too?

Prophylactic removal of the appendix during a benign gynecologic procedure is known as “elective incidental appendectomy.”1 Incidental appendectomy at the time of cesarean delivery was reported initially in 1959.2 Subsequent studies of removal of a normal-appearing appendix at the time of gynecologic surgery have met with considerable debate. Proponents argue that removal of the appendix at the time of abdominal hysterectomy does not increase operative time or postoperative morbidity. More important, it does prevent future appendicitis.3-5

Some surgeons disagree, citing an increase in operative time, hospital costs, and patient morbidity as reasonable concerns. They also note that appendectomy requires an additional surgical procedure, which could increase the risk of infection and other complications and lead to adhesion formation.

Advantages of incidental appendectomy include technical ease, low patient morbidity and mortality, and significant diagnostic and protective value.6 It also prevents conflicting diagnoses, especially in patients who have chronic pelvic pain, a ruptured ovarian cyst, or endometriosis. Other patients likely to benefit from elective incidental appendectomy are those who are undergoing abdominal radiation or chemotherapy, women unable to communicate health complaints, and those who are planning to undergo complex abdominal or pelvic procedures that are likely to cause extensive adhesions.1

In this article, we describe the rationale behind this procedure, as well as the technical steps involved.

The laparoscopic approach is preferred

Appendectomy is commonly performed laparoscopically. Semm first described this approach in 1983.7 Several studies since have reported that incidental laparoscopic appendectomy is safe, easy to perform, and should be offered to patients undergoing a concomitant gynecologic procedure.8-10 Laparoscopic removal of a normal appendix does not add morbidity or prolong hospitalization, compared with diagnostic laparoscopy. A large study drawing from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS) database found laparoscopic removal of the appendix to be associated with lower mortality, fewer complications, shorter hospitalization, and lower mean hospital charges, compared with open appendectomy.11 The same study found laparoscopic appendectomy to be the procedure of choice in both perforated and nonperforated appendicitis.

Overweight and obese patients also may benefit from the laparoscopic approach because it avoids problems associated with an open incision, such as the need for abdominal wall retraction, a longer hospital stay, and a risk of wound infection, compared with smaller incisions—especially in this high-risk population.12

Cost is another issue. Any prolonged surgical time and higher medical costs required for incidental appendectomy decrease as surgical proficiency and experience rise. The concomitant performance of endoscopic procedures can also reduce the risk associated with anesthesia for reoperations.

Endometriosis patients stand to benefit from appendectomy

There is compelling evidence that elective appendectomy is beneficial in patients who have endometriosis. Endometriosis of the bowel has been reported in 5.3% of all histologically proven endometriosis cases, with appendiceal endometriosis found in approximately 1% of women with endometriosis.13 Despite the low prevalence (2.8%) of appendiceal endometriosis,14 some studies reported a high incidence of appendiceal endometriosis when incidental appendectomy was performed. Patients who report right lower quadrant (RLQ) pain, chronic pelvic pain, and ovarian endometrioma had the highest incidence of abnormal histopathologic findings.15-17 Because most women with endometriosis present with these symptoms, it is prudent to counsel patients preoperatively about the incidence of appendiceal endometriosis and to visually examine the appendix during gynecologic surgery to identify incidental appendiceal pathology.

Age may influence the appendectomy decision

The incidence of acute appendicitis is highest among people aged 10 to 19 years. The estimated lifetime risk of appendicitis is 6.7%.18 The surgical dilemma is whether to perform incidental appendectomy in the nonadolescent population, which is at lower risk for appendicitis, as a preventive measure.

We lack randomized trials on the benefit of incidental appendectomy. A retrospective study of open procedures supported incidental appendectomy in patients younger than 35 years; for patients 35 to 50, the decision was left to the clinical judgment of the surgeon, based on the patient’s clinical condition.4 The same study failed to support incidental appendectomy in women older than 50 years.

When the appendix is not easily accessible, or the surgical complexity of the gynecologic procedure prevents the surgeon from safely performing an appendectomy, it is better to complete the planned gynecologic surgery and forgo the appendectomy. It is acceptable to make the decision to refrain from the appendectomy intraoperatively if the risk of complications outweighs the likely benefits. The practice of cautionary discretion demonstrates sound judgment and avoids compromising the safety of the patient.

1. Maintain at least three laparoscopic sites

- After the laparoscopic gynecologic procedure, maintain three trocar sites—preferably, two 5-mm trocars and one 12-mm trocar.

- The first 5-mm trocar, at the umbilical incision, accommodates the laparoscopic camera. The second 5-mm trocar serves as an accessory port for laparoscopic instruments and is inserted into the RLQ.

- The 12-mm trocar in the left lower quadrant (LLQ) is also used to insert endoscopic instruments. This trocar site will be used at the conclusion of the appendectomy to accommodate the mechanical stapling device and the specimen bag for removal of the excised organ.

FIGURE 1: Visualize the appendix. Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix.

2. Identify the appendix

- Perform a careful visual exploration of the abdominal contents to exclude other intra-abdominal pathology.

- Identify the cecum and ileocolic junction to locate the appendix (FIGURE 1).

- Visually inspect the appendix and identify any gross appendiceal pathology.

FIGURE 2: Divide the mesoappendix

Isolate, cauterize, and divide the mesoappendix using 5-mm ultrasonic shears.

3. Dissect the appendix (VIDEO 1)

- Insert an atraumatic forceps through the 5-mm right accessory trocar.

- Grasp the fatty tissue at the tip of the appendix and provide some traction.

- Elevate the appendix to facilitate visualization of the mesoappendix.

- Isolate the mesoappendix and cauterize and divide it using 5-mm ultrasonic shears inserted through the RLQ trocar (FIGURE 2).

- Release some of the upward tension from the specimen retraction by dropping the height of the instrument to prevent undue trauma and bleeding.

- Make a window between the mesentery and the base of the appendix to facilitate dissection.

- Skeletonize the mesoappendix at the junction of the appendiceal base and the cecum.

- During skeletonization, pay special attention to the appendiceal artery at the base of the mesoappendix.

FIGURE 3: Apply the stapling device

Apply the stapling device across the base of the appendix.

4. Resect the appendix (VIDEO 2)

- Insert an automatic stapling device through the 12-mm port and apply it across the base of the appendix (FIGURE 3).

- Apply the mechanical stapling device for 15 seconds to crush the base of the appendix and empty its contents.

- Visualize both sides of the stapler to ensure that it is placed at the base of the appendix.

- Always check the tip of the device to ensure that the jaws of the stapling device fully compress the appendix and have not inadvertently grasped other abdominal contents.

- With the stapling device compressing the base of the appendix, release some of the upward tension on the specimen by dropping the height of the retraction.

- Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base

(FIGURE 4). - Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump to ensure hemostasis (FIGURE 5).

FIGURE 4: Excise the appendix

Activate the stapling device and completely excise the appendix from its base.

FIGURE 5: Ensure hemostasis

Thoroughly inspect the appendiceal stump and ensure hemostasis.

5. Remove the specimen (VIDEO 3)

- Remove the stapling device and replace it with a specimen retrieval bag, inserting it through the 12-mm port.

- Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag to prevent abdominal contamination (FIGURE 6).

- Close the specimen retrieval bag inside the abdomen.

- Refrain from removing the specimen bag through the trocar or forcefully passing the appendix through a small incision. We usually withdraw the 12-mm trocar, then remove the cinched bag containing the resected appendix under direct visualization. We take all precautionary measures to prevent breakage of the bag, which would leak appendiceal contents into the abdomen.

FIGURE 6: Remove the specimen

Place the amputated appendix in the specimen retrieval bag and remove it, intact, through the patient’s abdomen.

6. Perform a few last measures

- If the surgeon chooses, suction and irrigation can be performed at the completion of the appendectomy procedure.

- Send all surgical specimens to pathology for evaluation.

- Complete the operation in the usual laparoscopic fashion. Remove all instruments, and close the 12-mm trocar port site using the Carter Thomason fascial closure device. Close the remaining port sites using 2-0 interrupted suture (Monocryl). Apply skin adhesive to all laparoscopic incisions.

- For more on surgical technique of appendectomy, see Baggish,19 Jaffe and Berger,20 and Daniell and colleagues.21

Coding for appendectomy is fairly straightforward if you know the rules, but prophylactic removal of the appendix, whether performed at the time of a laparoscopic or open abdominal primary procedure, will usually lead to reimbursement difficulties for surgeons even though CPT codes exist to report the procedure. Knowing when and how to bill and document the circumstances for removal will go a long way in getting payment for the procedure. Note that these rules apply to a single surgeon who is performing the entire surgery. When an ObGyn is performing gyn procedures, but a general surgeon is the one who removes the appendix, that surgeon will not be subject to bundling rules, but will still have to make a case with the payer for removing an otherwise normal appendix.

There are 5 codes that can be used to report an appendectomy:

- 44950 Appendectomy;

- 44955 Appendectomy; when done for indicated purpose at time of other major procedure (not as separate procedure)

- 44960 Appendectomy; for ruptured appendix with abscess or generalized peritonitis

- 44970 Laparoscopy, surgical, appendectomy code

- 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Code 44950 represents either a stand-alone procedure or an incidental appendectomy when performed with other open abdominal procedures. Under CPT guidelines this code would only be reported 1) when this is the only procedure performed and the appendix is removed for a diagnosis other than rupture with abscess, or 2) with a modifier -52 added if the surgeon believes that an incidental appendectomy needs to be reported. Use of a modifier -52 will lead to review of the documentation by the payer, and it will be up to the surgeon to convince the payer that he should be paid for taking out an appendix that is found to be normal. Billing 44950 with other abdominal procedures without this modifier will lead to an outright denial due to bundling edits, which permanently bundle 44950 with all major abdominal procedures.

Code 44955 is the code to report when an appendectomy is performed for an indicated purpose at the time of other open abdominal procedures. For instance, the appendix may have been removed due to a finding of distention with fecalith or extensive adhesions binding the appendix to the abdominal wall. When this code is reported, no modifier is used because it is a CPT “add-on” code that can only be billed in conjunction with other procedures.

Code 44960 is only reported when no other open abdominal procedures are performed at the operative session and the reason for taking out the appendix is rupture with abscess. If rupture is found at the time of an abdominal procedure to remove a mass, for instance, code 44955 would be reported instead.

Code 44970 is the only laparoscopic approach code for an appendectomy, but it would only be reported when 1) the appendectomy was the only laparoscopic procedure performed, or 2) the appendectomy was incidental, but the surgeon felt it needed to be reported. There is no instruction about using a modifier -52 with 44970 to report an incidental appendectomy. According to the American Medical Association’s January 2012 issue of CPT Assistant, laparoscopic removal of the appendix for an indicated purpose at the time of another major laparoscopic procedure should be reported as 44979, Unlisted laparoscopy procedure, appendix.

Keep in mind that code 44970 is bundled into a long list of laparoscopic procedures, including codes for treating stress urinary incontinence and prolapse (CPT codes 51990–51992, 57425), sterilization procedures (CPT codes 58670–58671), hysterectomy procedures (CPT codes 58541–58544, 58548, 58550–58554, 58570–58573), myomectomy procedures (CPT code 58545–58546), as well as codes for lysis, removal of lesions and ovaries, or aspiration of lesions (CPT codes 49321–49322, 58660–58662). A modifier -59 (Distinct Procedural Service) can be reported to bypass these edits, but the payer will request documentation to ensure that the criteria for using this modifier apply. The CPT criteria include documentation of a different session, different procedure or surgery, different site or organ system, separate incision/excision, separate lesion, or separate injury (or area of injury in extensive injuries) which is not ordinarily encountered or performed on the same day by the same individual. Failure to discuss the reason for the removal in the body of the operative report will generally mean the payer will deny extra payment for the appendectomy.

—MELANIE WITT, RN, CPC, COBGC, MA

Ms. Witt is an independent coding and documentation consultant and former program manager, department of coding and nomenclature, American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Adequate training is essential

Surgical proficiency in laparoscopic appendectomy, like any surgical skill set, requires adequate training to ensure procedural familiarity and expertise and to encourage consistency. This training, preferably undertaken during residency, should be an essential part of obstetrics and gynecology education.

It is important to know which patient populations are at high risk for appendiceal pathology so that they can be assessed and counseled adequately prior to surgery. Among the components of patient counseling is a thorough and impartial discussion of procedural risks and benefits. Risk-benefit considerations should include the patient’s preferences so that she can be an active participant in her own health-care decisions.

Because the risks of appendectomy are minimal, and complications are rare, it is appropriate to offer elective laparoscopic appendectomy to patients scheduled to undergo benign gynecologic procedures, especially in the setting of chronic pelvic pain and endometriosis.

CASE: Resolved

The patient is counseled about the benefits and risks of laparoscopic incidental appendectomy, including the fact that it may be especially beneficial in women who have endometriosis. She consents to undergo the procedure at the time of her total laparoscopic hysterectomy.

Both procedures are performed safely, with no complications, and the patient’s immediate postoperative course is unremarkable. After one night of hospitalization, she is discharged home. The histopathologic report on the appendiceal specimen reveals endometriosis with fibrous obliteration of the lumen.

We want to hear from you! Tell us what you think.

CLICK HERE to access 8 Surgical Technique articles published in OBG Management

in 2012.

1. Elective coincidental appendectomy. ACOG Committee Opinion#323. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1141-1142.

2. Davis ME. Gynecologic operations at cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1959;2:1095-1106.

3. Lynch CB, Sinha P, Jalloh S. Incidental appendectomy during gynecological surgery. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):261-262.

4. Snyder TE, Selanders JR. Incidental appendectomy—yes or no? A retrospective case study and review of the literature. Infec Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1998;6(1):30-37.

5. Salom EM, Schey D, Penalver M, et al. The safety of incidental appendectomy at the time of abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1563-1568.

6. Lee JH, Choi JS, Jeon SW. Laparoscopic incidental appendectomy during laparoscopic surgery for ovarian endometrioma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):28.e1-5.

7. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15(2):59-64.

8. O’Hanlan KA, Fisher DT, O’Holleran MS. 257 incidental appendectomies during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. JSLS. 2007;11(4):428-431.

9. Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Incidental appendectomy during videolaseroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(3):559-564.

10. Song JY, Yordan E, Rotman C. Incidental appendectomy during endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2009;13(3):376-383.

11. Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006-2008. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(12):2226-2231.

12. Jarnagin BK. The vermiform appendix in relation to gynecology. In: Rock JA Jones HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Chapter 42. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

13. Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(5):727-730.

14. Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, Stratton P. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(2):298-303.

15. Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, Marziali M, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):206-209.

16. Harris RS, Foster WG, Surrey MW, Agarwal SK. Appendiceal disease in women with endometriosis and right lower quadrant pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):536-541.

17. Wie HJ, Lee JH, Kyung MS, Jung US, Choi JS. Is incidental appendectomy necessary in women with ovarian endometrioma? Aust NZ J Obstet Gyn. 2008;48(1):107-111.

18. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

19. Baggish MS. Appendectomy. In: Baggish MS Karram MM, eds. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Chapter 100. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2006.

20. Jaffe BM, Berger DH. The appendix. In: Brunicardi F Andersen D, Billiar T, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. Chapter 30. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

21. Daniell JF, Gurley LD, Kurtz BR, Chamber JF. The use of an automatic stapling device for laparoscopic appendectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78(4):721-723.

1. Elective coincidental appendectomy. ACOG Committee Opinion#323. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106(5 Pt 1):1141-1142.

2. Davis ME. Gynecologic operations at cesarean section. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 1959;2:1095-1106.

3. Lynch CB, Sinha P, Jalloh S. Incidental appendectomy during gynecological surgery. Int J Gynecol Obstet. 1997;59(3):261-262.

4. Snyder TE, Selanders JR. Incidental appendectomy—yes or no? A retrospective case study and review of the literature. Infec Dis Obstet Gynecol. 1998;6(1):30-37.

5. Salom EM, Schey D, Penalver M, et al. The safety of incidental appendectomy at the time of abdominal hysterectomy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189(6):1563-1568.

6. Lee JH, Choi JS, Jeon SW. Laparoscopic incidental appendectomy during laparoscopic surgery for ovarian endometrioma. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2011;204(1):28.e1-5.

7. Semm K. Endoscopic appendectomy. Endoscopy. 1983;15(2):59-64.

8. O’Hanlan KA, Fisher DT, O’Holleran MS. 257 incidental appendectomies during total laparoscopic hysterectomy. JSLS. 2007;11(4):428-431.

9. Nezhat C, Nezhat F. Incidental appendectomy during videolaseroscopy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1991;165(3):559-564.

10. Song JY, Yordan E, Rotman C. Incidental appendectomy during endoscopic surgery. JSLS. 2009;13(3):376-383.

11. Masoomi H, Mills S, Dolich MO, et al. Comparison of outcomes of laparoscopic versus open appendectomy in adults: data from the Nationwide Inpatient Sample (NIS), 2006-2008. J Gastrointest Surg. 2011;15(12):2226-2231.

12. Jarnagin BK. The vermiform appendix in relation to gynecology. In: Rock JA Jones HW, eds. TeLinde’s Operative Gynecology. 10th ed. Chapter 42. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

13. Weed JC, Ray JE. Endometriosis of the bowel. Obstet Gynecol. 1987;69(5):727-730.

14. Gustofson RL, Kim N, Liu S, Stratton P. Endometriosis and the appendix: a case series and comprehensive review of the literature. Fertil Steril. 2006;86(2):298-303.

15. Berker B, Lashay N, Davarpanah R, Marziali M, Nezhat CH, Nezhat C. Laparoscopic appendectomy in patients with endometriosis. J Minim Invasive Gynecol. 2005;12(3):206-209.

16. Harris RS, Foster WG, Surrey MW, Agarwal SK. Appendiceal disease in women with endometriosis and right lower quadrant pain. J Am Assoc Gynecol Laparosc. 2001;8(4):536-541.

17. Wie HJ, Lee JH, Kyung MS, Jung US, Choi JS. Is incidental appendectomy necessary in women with ovarian endometrioma? Aust NZ J Obstet Gyn. 2008;48(1):107-111.

18. Addiss DG, Shaffer N, Fowler BS, Tauxe RV. The epidemiology of appendicitis and appendectomy in the United States. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(5):910-925.

19. Baggish MS. Appendectomy. In: Baggish MS Karram MM, eds. Atlas of Pelvic Anatomy and Gynecologic Surgery. 2nd ed. Chapter 100. Philadelphia, PA: Saunders; 2006.

20. Jaffe BM, Berger DH. The appendix. In: Brunicardi F Andersen D, Billiar T, et al, eds. Schwartz’s Principles of Surgery. 9th ed. Chapter 30. New York, NY: McGraw Hill Professional; 2010.

21. Daniell JF, Gurley LD, Kurtz BR, Chamber JF. The use of an automatic stapling device for laparoscopic appendectomy. Obstet Gynecol 1991;78(4):721-723.

Allergic rhinitis: What’s best for your patient?

• Use nasal steroids to treat allergic rhinitis (AR) in adults. A

• Recommend nasal saline irrigation to reduce symptoms in children and adults with seasonal rhinitis. A

• Consider immunotherapy for adults and children with severe AR that does not respond to conventional pharmacotherapy or allergen avoidance measures. C

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

CASE A man in his 30s with allergic rhinitis (AR) at predictable times of the year with high pollen counts reports only modest symptom relief with a nasal steroid preparation after 3 weeks of use. He comes to see you because he’s “tired of feeling lousy all of the time.”

What management options would you consider?

There is a plethora of treatment options for patients like this one, and considerable variation in clinical practice when it comes to AR.1 The good news is that there are several recent guidelines for treating AR patients, whose symptoms (and underlying cause) can vary widely.

The following review—and accompanying algorithm—provides evidence-based recommendations that can help you refine your approach to AR.

Two guidelines, and several Cochrane reviews

Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma (ARIA), a sentinel rhinitis treatment guideline, was published in 2001 and updated in 2008 and 2010.2-4 The British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology Standards of Care Committee (BSACI) published guidelines for rhinitis management in 2008 and guidelines for immunotherapy in 2011.5,6 In addition, several Cochrane reviews have been performed.7-12 The ALGORITHM1-6 combines these recommendations. The TABLE2-12 itemizes the recommendations made by each guideline.

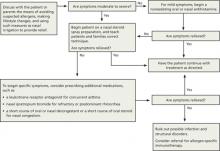

ALGORITHM

An evidence-based approach to treating allergic rhinitis1-6

Based on recommendations from ARIA and BSACI guidelines and Cochrane reviews

ARIA, Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma; BSACI, British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology Standards of Care Committee.

TABLE

Treatment recommendations/suggestions for allergic rhinitis2-12

| TREATMENT RECOMMENDATIONS/SUGGESTIONS | ARIA 2001 | ARIA 2008 | ARIA 2010 | BSACI 2008 | BSACI 2011 | COCHRANE REVIEWS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General principles of treatment | ||||||

| Maintenance therapy is required for persistent AR as medications have little effect after cessation. | X | |||||

| Patient education | ||||||

| Standardized patient education improves disease-specific quality of life. | X | |||||

| Nasal steroids | ||||||

| NS are the most effective monotherapy for all symptoms of AR, seasonal and perennial,* including nasal congestion. | X | |||||

| NS are recommended for AR treatment in adults and suggested for children. | X | |||||

| NS are the treatment of choice for moderate to severe persistent* AR and for treatment failures with antihistamines alone. | X | |||||

| NS are suggested over oral antihistamines in adults and children for seasonal AR. | X | |||||

| NS are suggested over oral antihistamines for adults and children with persistent AR. | X | |||||

| NS are recommended rather than nasal antihistamines. | X | |||||

| NS are recommended over oral leukotriene receptor antagonists for seasonal AR. | X | |||||

| NS are the most effective treatment of AR for children. | X | |||||

| There is insufficient evidence for or against the use of oral antihistamines plus NS vs NS alone in children with AR. | X (2010) | |||||

| Intermittent* NS use may be beneficial in children. | X | |||||

| Avoid NS with high bioavailability (betamethasone) in children, as regular use for >1 year may decrease growth rate. | X | |||||

| Antihistamines | ||||||

| New-generation oral nonsedating antihistamines that do not affect cytochrome P450 are recommended for the treatment of patients with AR. | X | |||||

| Oral or topical antihistamines are first-line treatment for mild to moderate intermittent and moderate persistent AR. | X | |||||

| When NS alone do not control moderate to severe persistent AR, may add oral or topical antihistamines. | X | |||||

| New-generation oral antihistamines are suggested over nasal antihistamines for children and adults, and for children with seasonal or persistent AR. | X | |||||

| Oral antihistamines are suggested over oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in patients with seasonal AR and in preschool children with persistent AR. | X | |||||

| Nasal antihistamines are suggested over nasal chromones (the need to use chromones 4 times daily may limit adherence). | X | |||||

| Nasal antihistamine use is suggested for children and adults with seasonal AR. | X | |||||

| Patients with persistent AR should avoid using nasal antihistamines until more data on efficacy and safety are available. | X | |||||

| In children, weigh adverse effects of antihistamines against the general malaise caused by AR. | X | |||||

| Treatment with once-daily, long-acting antihistamines rather than multiple daily dosing may improve adherence in children. | X | |||||

| Continuous administration of antihistamines is optimal in children, rather than as needed. | X | |||||

| Intraocular antihistamines or intraocular chromones are suggested for patients with ocular symptoms. | X | |||||

| Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists | ||||||

| Oral leukotriene receptor antagonists are suggested for children and adults with seasonal AR and for preschool children with persistent AR. | X | |||||

| Avoid oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in adults with persistent AR. | X | |||||

| Decongestants | ||||||

| For adults with severe nasal obstruction, a short course (<5 days) of a nasal decongestant, along with other drugs, is suggested. | X | |||||

| Nasal decongestants may be useful for eustachian tube dysfunction when flying, for children with acute otitis media with middle ear pain, to relieve congestion after an upper respiratory infection, and to improve nasal patency prior to NS use. | X | |||||

| Regular oral decongestant use is not suggested. | X | X | ||||

| Avoid decongestants in pregnant patients. | X | |||||

| Avoid using nasal decongestants in preschool children. | X | |||||

| Chromones | ||||||

| Limited use of chromones is recommended for children and adults with mild symptoms. | X | |||||

| Chromones are less effective than NS or antihistamines. | X | |||||

| Nasal antihistamines are suggested over nasal chromones. | X | |||||

| Intraocular antihistamines or intraocular chromones are suggested for ocular symptoms. Due to the excellent safety of these agents, chromones may be tried before antihistamines. | X | |||||

| Nasal saline | ||||||

| Nasal saline irrigation reduces symptoms in children and adults with seasonal rhinitis. | X | |||||

| Oral, intramuscular steroids | ||||||

| A short course of oral glucocorticosteroids is suggested for patients with AR and moderate to severe nasal or ocular symptoms not controlled with other treatments. | X | |||||

| Oral steroids are rarely indicated, but a short course (5-10 days) may be used for severe nasal congestion, uncontrolled symptoms on conventional pharmacotherapy, or important social/work events. | X | |||||

| Avoid intramuscular steroids. | X | X | ||||

| Ipratropium | ||||||

| Nasal ipratropium is suggested for treatment of rhinorrhea for patients with persistent AR. | X | |||||

| Allergen-specific immunotherapy | ||||||

| Immunotherapy is effective for adults and children with severe AR who do not respond to conventional pharmacotherapy or allergen avoidance measures. | X | |||||

| SCIT is suggested for adults with seasonal AR and those with persistent AR due to house dust mites. | X | |||||

| SCIT is efficacious for patients with seasonal AR due to pollens, resulting in decreased symptoms and medication use with few severe adverse reactions. | X (2007) | |||||

| SLIT is suggested for adults with AR due to pollen, although other alternatives may be equally reasonable. | X | |||||

| SLIT is safe and efficacious for AR treatment, decreasing symptoms and medication requirements. | X (2003) | |||||

| Nasal immunotherapy is suggested for adults with AR due to pollens. | X | |||||

| For pregnant patients, maintenance ASI may be continued, but starting ASI or increasing the dose is contraindicated. | X | |||||

| SCIT is suggested for children with AR. | X | |||||

| SCIT should not be started before 5 years of age. | X | |||||

| Based on preliminary studies, SLIT is safe, but more studies are needed in children. | X | |||||

| SLIT and NIT are suggested for children with AR due to pollens, acknowledging that other alternatives may be equally reasonable. SLIT should not be given to children with AR due to HDM unless being done for research. | X | |||||

| Lifestyle changes | ||||||

| Avoid single chemical or physical preventive and combination preventive methods to reduce HDM exposure. | X | |||||

| Allergen avoidance may decrease AR symptoms, but more research is needed. | X (2010) | |||||

| Achieving substantial reductions in HDM load may decrease AR symptoms. | X (2012) | |||||

| Avoidance of mold or animal dander is recommended for patients who are allergic to them. | X | |||||

| Nasal filters can reduce symptoms of AR during ragweed and grass pollen seasons. | X | |||||

| Complementary and alternative medicine | ||||||

| Avoid homeopathy, acupuncture, butterbur, herbal medicines, and phototherapy. | X | |||||

| AR, allergic rhinitis; ARIA, Allergic Rhinitis and its Impact on Asthma; ASI, allergen-specific immunotherapy; BSACI, British Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology Standards of Care Committee; HDM, house dust mites; NIT, nasal immunotherapy; NS, nasal steroids; SCIT, subcutaneous immunotherapy; SLIT, sublingual immunotherapy. *ARIA 2008 recommended changing the classification of AR from seasonal and perennial (frequent nonseasonal nasal or ocular symptoms) to intermittent (symptoms lasting <4 days per week or <4 weeks per year) or persistent (symptoms >4 days per week and >4 weeks per year).3 AR severity is classified as mild or moderate to severe.2,3 | ||||||

The summary that follows provides a more detailed look at the recommendations, with a review of the pathophysiology of AR (“Phases of allergic rhinitis”2,3,5,8,13-15).

The early phase of allergic rhinitis (AR) occurs within minutes of allergen exposure. Mast cell degranulation releases histamine and other inflammatory mediators that cause sneezing, pruritus, rhinorrhea, and nasal congestion.3,8,13 The late phase, beginning at 4 hours and peaking 6 to 12 hours after exposure, is believed to be due to recruitment of circulating leukocytes—particularly eosinophils. Leukocyte activation causes additional inflammatory mediators to be released, which primarily causes nasal congestion—often the most bothersome symptom of AR.2,5,8,13,14 Other presenting symptoms may include feeling “fuzzy” or tired, chronic viral infections, sniffing, eye rubbing, blinking, congested voice, snoring, or dark skin beneath the eyes (allergic shiners).15

Of note: This summary preserves the terminology used in ARIA 2010. Specifically, the ARIA guideline uses the term suggest for conditional recommendations and recommend for strong recommendations.4 That same language is used here.

Nasal steroids: First-line Tx for moderate to severe symptoms

BSACI indicates that nasal steroids (NS) are the treatment of choice for moderate to severe persistent AR (symptoms lasting >4 days per week or >4 weeks per year).5 ARIA 2010 suggests NS as first-line treatment rather than oral antihistamines for adults and children with seasonal (related to outdoor allergens such as pollens or molds) and persistent AR.4 ARIA 2008 finds NS are the most effective treatment for children.3 Steroids reduce inflammation by decreasing inflammatory cell migration and inhibiting cytokine release.16 They are the most effective monotherapy for all symptoms of AR, including nasal congestion, which antihistamines do not treat effectively.13,16 NS also treat ocular symptoms of allergy effectively.15,17

The ARIA 2010 guideline also recommends using NS rather than nasal antihistamines and leukotriene receptor antagonists.4 Combination therapy (eg, NS with the addition of nasal antihistamines) is an option for severe or persistent AR, but it appears to be no more effective than monotherapy with NS.16 A 2010 Cochrane review determined there is insufficient evidence for or against the use of oral antihistamines plus NS vs NS alone in children with AR.7 Intermittent steroid use may be beneficial in children.5

Steroids begin working 6 to 8 hours after the first dose, although symptom reduction may take days and maximal effect up to 2 weeks.5 Treatment failure may be due to poor technique that can cause local adverse effects (ie, dryness, irritation, epistaxis). Technique-related failure occurs in up to 10% of users.5,15 Educating patients and families about correct technique with steroid spray may decrease nonadherence due to irritation and epistaxis.18 Tell them to shake the bottle well, look down, aim the nozzle toward the outside wall of the nostril using the opposite hand, and spray while sniffing lightly.5

Any steroid is appropriate for adults. For children ≥2 years of age, consider fluticasone propionate, mometasone furoate, or triamcinolone acetonide.3 These medications have lower systemic bioavailability and a decreased risk of such adverse effects as hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis suppression and growth retardation.15 Budesonide is appropriate for those ≥6 years.19-21 Avoid regular use of betamethasone, which has high bioavailability, for >1 year in children, as it may decrease their growth rate.3 Beclomethasone, fluticasone, and budesonide have been used widely and safely for pregnant women with asthma.5

Antihistamines are first-line Tx for mild symptoms

ARIA 2010 recommends new-generation oral nonsedating antihistamines that do not affect cytochrome P450 for mild AR,4 such as cetirizine, levocetirizine, loratadine, desloratadine, and fexofenadine. First-generation antihistamines can reduce symptoms, but are not first-line treatment as they cause sedation, fatigue, decreased cognitive function, and reduced academic and work performance.3-5 ARIA 2010 further suggests choosing oral antihistamines over oral leukotriene receptor antagonists in patients with seasonal AR and in preschool children with persistent AR.4

BSACI recommends oral or topical antihistamines as first-line treatment for mild to moderate symptoms lasting <4 days per week or <4 weeks per year and moderate persistent AR.5 When steroids alone do not control moderate to severe persistent AR, BSACI recommends adding oral or topical antihistamines.5 Oral and topical antihistamines decrease histamine-related symptoms of itching, rhinorrhea, and sneezing, but do not significantly decrease nasal congestion.15

Nasal antihistamines (levocabastine, azelastine) have a rapid onset of action and few adverse effects.3 ARIA 2010 suggests nasal antihistamines over nasal chromones (inhibitors of mast cell degranulation) and notes that the need to use chromones 4 times daily may limit adherence.4 The same guidelines suggest nasal antihistamine use for children and adults with seasonal AR and suggest not using nasal antihistamines for patients with persistent AR until more data on efficacy and safety are available.4

Alezastine is approved for individuals ≥5 years, and olopatadine is approved for individuals ≥6 years for the treatment of AR.16,22,23 A pediatric review article noted nasal antihistamine (azelastine) plus nasal fluticasone was more efficacious than NS alone.15

In children, weigh adverse effects of antihistamines against the general malaise caused by AR.3 Do not use first-generation antihistamines due to the sedation that may interfere with learning.15 Treatment with once-daily, long-acting antihistamines rather than multiple daily dosing may improve adherence in children.5 Continuous administration, rather than as needed, is optimal treatment in children.5 Cetirizine, loratadine, and levocetirizine have been studied and are effective and safe in children.3 Levocetirizine has proven safe and efficacious for children ≥2 years.24 Fexofenadine was found to be effective and safe for those ≥6 years.25