User login

Hospitalist Sign‐out

Hospital medicine is a main component of healthcare in the United States and is growing.[1] In 1995, 9% of inpatient care performed by general internists to Medicare patients was provided by hospitalists; by 2006, this had increased to 37%.[2] The estimated 30,000 practicing hospitalists account for 19% of all practicing general internists[2, 3, 4] and have had a major impact on the treatment of inpatients at US hospitals.[5] Other specialties are adopting the hospital‐based physician model.[6, 7] The hospitalist model does have unique challenges. One notable aspect of hospitalist care, which is frequently shift based, is the transfer of care among providers at shift change.

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognizes patient handoffs/sign‐outs as a core competency for hospitalists,[8] but there is little literature evaluating hospitalist sign‐out quality.[9] A systematic review in 2009 found no studies of hospitalist handoffs.[8] Furthermore, early work suggests that hospitalist handoffs are not consistently effective.[10] In a recent survey, 13% of hospitalists reported they had received an incomplete handoff, and 16% of hospitalists reported at least 1 near‐miss attributed to incomplete communication.[11] Last, hospitalists perform no better than housestaff on evaluations of sign‐out quality.[12]

Cross‐coverage situations, in which sign‐out is key, have been shown to place patients at risk.[13, 14] One study showed 7.1 problems related to sign‐out per 100 patient‐days.[15] Failure during sign‐out can ultimately threaten patient safety.[16] Therefore, evaluating the quality of hospitalist sign‐outs by assessing how well the sign‐out prepares the night team for overnight events is necessary to improve hospitalist sign‐outs and ultimately increase patient safety.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study took place at YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH), the primary teaching affiliate for the Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, Connecticut. YNHH is a 966‐bed, urban, academic medical center. The Hospitalist Service is a nonteaching service composed of 56.1 full‐time‐equivalent (FTE) attending physicians and 26.8 FTE midlevel providers. In fiscal year 2012, the YNHH Hospitalist Service cared for 13,764 discharges, or approximately 70% of general medical discharges. Similar patients are cared for by both hospitalists and housestaff. Patients on the hospitalist service are assigned an attending physician as well as a midlevel provider during the daytime. Between the departure of the day team and the arrival of the night team, typically a 2‐hour window, a skeleton crew covers the entire service and admits patients. The same skeleton crew coverage plan exists in the approximately 2.5‐hour morning gap between the departure of the night team and arrival of the day team. Overnight, care is generally provided by attending hospitalist physicians alone. Clinical fellows and internal medicine residents occasionally fill the night hospitalist role.

Sign‐out Procedure

The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses a written sign‐out[17] created via template built into the electronic health record (EHR), Sunrise Clinical Manager (version 5.5; Allscripts, Chicago, IL) and is the major mechanism for shift‐to‐shift information transfer. A free text summary of the patient's medical course and condition is created by the provider preparing the sign‐out, as is a separate list of to do items. The free text box is titled History (general hospital course, new events of the day, overall clinical condition). A representative narrative example is, 87 y/o gentleman PMHx AF on coumadin, diastolic CHF (EF 40%), NIDDM2, first degree AV block, GIB in setting of supratherapeutic INR, depression, COPD p/w worsening low back pain in setting of L1 compression frx of? age. HD stable. An option exists to include a medication list pulled from the active orders in the EHR when the sign‐out report is printed. The sign‐out is typically created by the hospitalist attending on the day of admission and then updated daily by the mid‐level provider under the supervision of the attending physician, in accordance with internal standards set by the service. Formal sign‐out training is included as part of orientation for new hires, and ongoing sign‐out education is provided, as needed, by a physician assistant charged with continuous quality improvement for the entire service. The service maintains an expectation for the entire team to provide accurate and updated sign‐out at every shift change. Attending hospitalists or mid‐level providers update the sign‐out on weekends. Because the day team has generally left the hospital prior to the arrival of the night team, verbal sign‐out occurs rarely. Should a verbal sign‐out be given to the night team, it will be provided by the daytime team directly to the night team either via telephone or the day team member staying in the hospital until arrival of the night team.

Participants

All full‐time and regularly scheduled part‐time attending physicians on the YNHH hospitalist night team were eligible to participate. We excluded temporary physicians on service, including clinical fellows and resident moonlighters. Hospitalists could not participate more than once. Written informed consent was obtained of all hospitalists at the start of their shift.

Data Collection

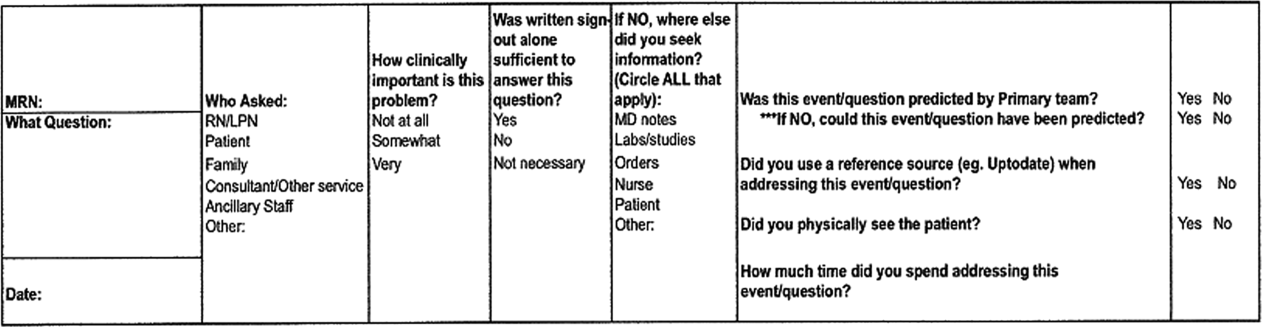

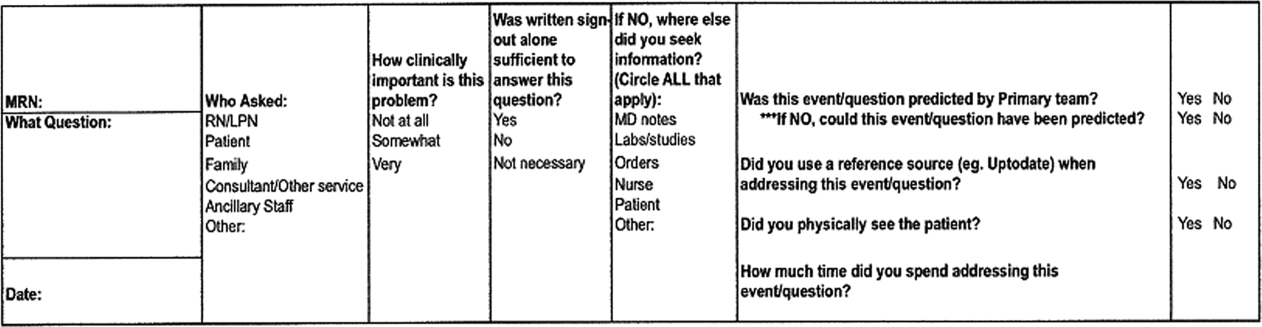

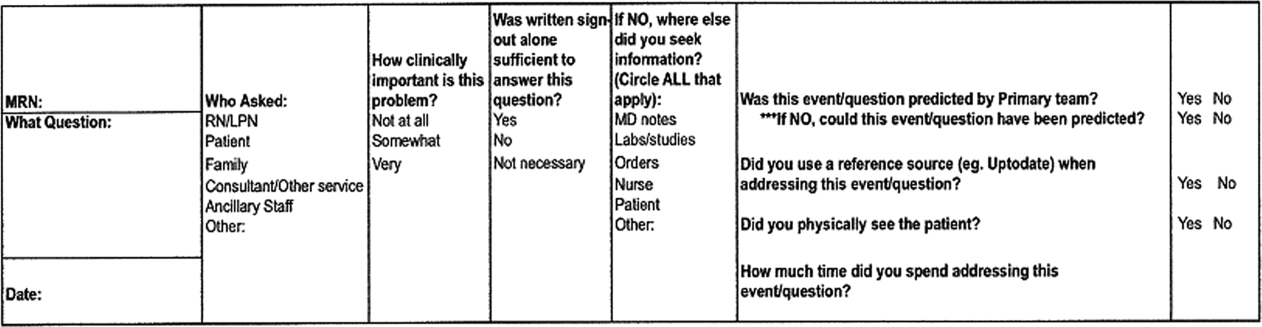

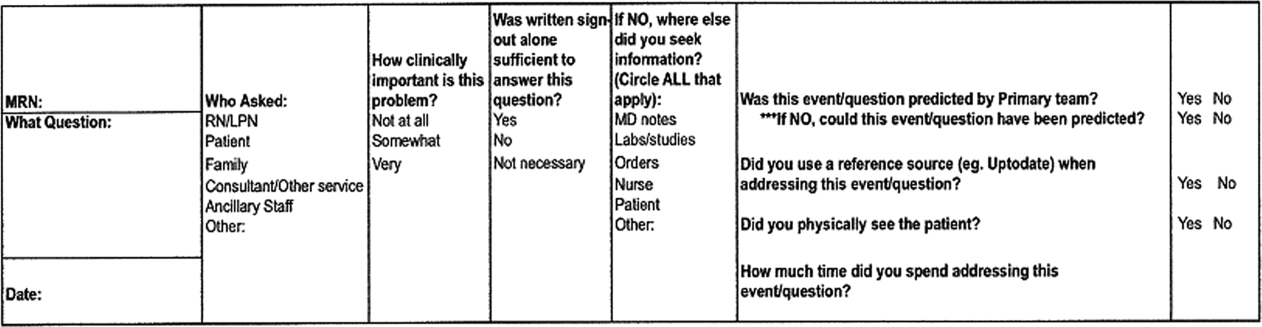

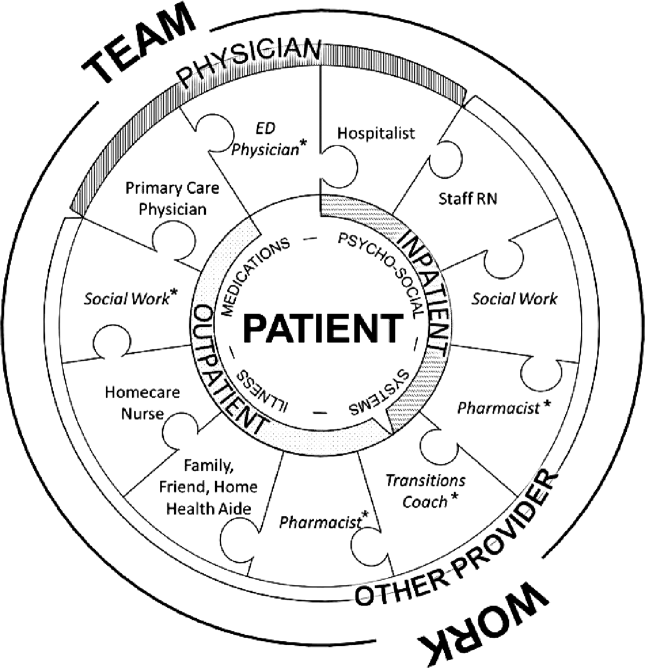

Hospitalists who consented were provided a single pocket card during their shift. For every inquiry that involved a patient that the hospitalist was covering, the hospitalist recorded who originated the inquiry, the clinical significance, the sufficiency of written sign‐out, which information was used other than the written sign‐out, and information regarding the anticipation of the event by the daytime team (Figure 1).

Data were collected on 6 days and distributed from April 30, 2012 through June 12, 2012. Dates were chosen based on staffing to maximize the number of eligible physicians each night and included both weekdays and weekend days. The written sign‐out for the entire service was printed for each night data collection took place.

Main Predictors

Our main predictor variables were characteristics of the inquiry (topic area, clinical importance of the inquiry as assessed by the hospitalist), characteristics of the patient (days since admission), and characteristics of the written sign‐out (whether it included any anticipatory guidance and a composite quality score). We identified elements of the composite quality score based on prior research and expert recommendations.[8, 18, 19, 20] To create the composite quality score, we gave 1 point for each of the following elements: diagnosis or presenting symptoms, general hospital course (a description of any event occurring during hospitalization but prior to date of data collection), current clinical condition (a description of objective data, symptoms, or stability/trajectory in the last 24 hours), and whether the sign‐out had been updated within the last 24 hours. The composite score could range from 0 to 4.

Main Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome measure was the quality and utility of the written‐only sign‐out as defined via a subjective assessment of sufficiency by the covering physician (ie, whether the written sign‐out was adequate to answer the query without seeking any supplemental information). For this outcome, we excluded inquiries for which hospitalists had determined a sign‐out was not necessary to address the inquiry or event.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used a cutoff of P<0.05 for statistical significance; all tests were 2‐tailed. We assessed characteristics of overnight inquiries using descriptive statistics and determined the association of the main predictors with sufficient sign‐out using 2 tests. We constructed a multivariate logistic regression model using a priori‐determined clinically relevant predictors to test predictors of sign‐out sufficiency. The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University.

RESULTS

Hospitalists recorded 124 inquiries about 96 patients. Altogether, 15 of 19 (79%) eligible hospitalists returned surveys. Of the 96 patients, we obtained the written sign‐out for 68 (71%). The remainder were new patients for whom the sign‐out had not yet been prepared, or patients who had not yet been assigned to the hospitalist service at the time the sign‐out report was printed.

Hospitalists referenced the sign‐out for 89 (74%) inquiries, and the sign‐out was considered sufficient to respond to 27 (30%) of these inquiries (ie, the sign‐out was adequate to answer the inquiry without any supplemental information). Hospitalists physically saw the patient for 14 (12%) inquiries. Nurses were the originator for most inquiries (102 [82%]). The most common inquiry topics were medications (55 [45%]), plan of care (26 [21%]) and clinical changes (26 [21%]). Ninety‐five (77%) inquiries were considered to be somewhat or very clinically important by the hospitalist (Table 1).

| Inquiry originator, No. (% of 124) | |

| Nurse | 102 (82) |

| Patient | 13 (10) |

| Consultant | 6 (5) |

| Respiratory therapy | 3 (2) |

| Inquiry subject, No. (% of 122) | |

| Medication | 55 (45) |

| Plan of care | 26 (21) |

| Clinical change | 26 (21) |

| Order reconciliation | 15 (12) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Clinical importance of inquiry, No. (% of 123) | |

| Very | 33 (27) |

| Somewhat | 62 (50) |

| Not at all | 28 (23) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Sufficiency of sign‐out alone in answering inquiry, No. (% of 121) | |

| Yes | 27 (22) |

| No | 62 (51) |

| Sign‐out not necessary for inquiry | 32 (26) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Days since admission, No. (% of 124) | |

| Less than 2 | 69 (44.4) |

| 2 or more | 55 (55.6) |

| Reference(s) used when sign‐out insufficient, No. (% of 62) | |

| Physician notes | 37 (60) |

| Nurse | 11 (18) |

| Labs/studies | 10 (16) |

| Orders | 9 (15) |

| Patient | 7 (11) |

| Other | 7 (11) |

| Was the event predicted by the primary team? No. (% of 119) | |

| Yes | 17 (14) |

| No | 102 (86) |

| Missing | 5 |

| If no, could this event have been predicted, No. (% of 102) | |

| Yes | 47 (46) |

| No | 55 (54) |

| Of all events that could have been predicted, how many were predicted? No. (% of 64) | |

| Predicted | 17 (27) |

| Not predicted | 47 (73) |

| Did you physically see the patient? No. (% of 117) | |

| Yes | 14 (12) |

| No | 103 (88) |

| Missing | 7 |

| Composite score, No. (% of 68) | |

| 0 or 1 | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 3 (4) |

| 3 | 31 (46) |

| 4 | 34 (50) |

| Anticipatory guidance/to‐do tasks, No. (% of 96) | |

| 0 | 69(72) |

| 1 | 21 (22) |

| 2 or more | 6 (6) |

No written sign‐outs had a composite score of 0 or 1; 3 (4%) had a composite score of 2; 31 (46%) had a composite score of 3; and 34 (50%) had a composite score of 4. Seventy‐two percent of written sign‐outs included neither anticipatory guidance nor tasks, 21% had 1 anticipatory guidance item or task, and 6% had 2 or more anticipatory guidance items and/or tasks.

The primary team caring for a patient did not predict 102 (86%) inquiries, and hospitalists rated 47 (46%) of those unpredicted events as possible for the primary team to predict. Five responses to this question were incomplete and excluded. Of the 64 events predicted by the primary team or rated as predictable by the night hospitalists, 17 (27%) were predicted by the primary team (Table 1).

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation to answer the majority of order reconciliation inquiries (5 [71%]), but was less effective at helping to answer inquiries about clinical change (7 [29%]), medications (10 [28%]), and plan of care (5 [24%]) (P=0.001). (Table 2) Ninety‐five events were rated as either very or somewhat clinically important, but this did not affect the likelihood of sign‐out being sufficient in isolation relative to the not at all clinically important group. Specifically, 33% of sign‐outs were rated sufficient in the very important group, 19% in the somewhat important group, and 50% in the not at all group (P=0.059).

| Predictor | Number of inquiries (%) for which sign‐out was sufficient in isolationb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Question topic | 0.001 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | 5/7 (71) | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 7/24 (29) | ||

| Medicationa (with clinical question) | 10/36 (28) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, procedure) | 5/21 (24) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.059 | ||

| Not at all | 8 (50) | ||

| Somewhat | 8 (19) | ||

| Very | 10 (33) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.015 | ||

| Less than 2 days | 21 (40) | ||

| 2 or more days | 6 (16) | ||

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.006 | ||

| 2 or more | 3 (60) | ||

| 1 | 3 (14) | ||

| 0 | 21 (34) | ||

| Composite score | 0.144 | ||

| <4 | 5 (15) | ||

| 4 | 10 (29) | ||

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation more frequently for inquiries about patients admitted <2 days prior to data collection than for inquiries about patients admitted more than 2 days prior to data collection (21 [40%] vs 6 [16%], respectively) (P=0.015) (Table 2).

Sign‐outs with 2 or more anticipatory guidance items were considered sufficient in isolation more often than sign‐outs with 1 or fewer anticipatory guidance item (60% for 2 or more, 14% for 1, 34% for 0; P=0.006) (Table 2). The composite score was grouped into 2 categoriesscore <4 and score=4with no statistical difference in sign‐out sufficiency between the 2 groups (P=0.22) (Table 2).

In multivariable analysis, no predictor variable was significantly associated with sufficient sign‐out (Table 3).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question topic | 0.58 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | Reference | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 0.29 (0.01 6.70) | ||

| Medication (+/‐ vitals or symptoms) | 0.17 (0.01 3.83) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, IV, CPAP, procedure) | 0.15 (0.01 3.37) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.85 | ||

| Not at All | Reference | ||

| Somewhat | 0.69 (0.12 4.04) | ||

| Very | 0.57 (0.08 3.88) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.332 (0.09 1.19) | 0.074 | |

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.26 | ||

| 2 or more | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.13 (0.01 1.51) | ||

| 0 | 0.21 (0.02 2.11) | ||

| Composite Score | 0.22 | ||

| <4 | Reference | ||

| 4 | 2.2 (0.62 7.77) |

DISCUSSION

In this study of written sign‐out among hospitalists and physician‐extenders on a hospitalist service, we found that the sign‐out was used to answer three‐quarters of overnight inquiries, despite the advanced level of training (completion of all postgraduate medical education) of the covering clinicians and the presence of a robust EHR. The effectiveness of the written sign‐out, however, was not as consistently high as its use. Overall, the sign‐out was sufficient to answer less than a third of inquiries in which it was referenced. Thus, although most studies of sign‐out quality have focused on trainees, our results make it clear that hospitalists also rely on sign‐out, and its effectiveness can be improved.

There are few studies of attending‐level sign‐outs. Hinami et al. found that nearly 1 in 5 hospitalists was uncertain of the care plan after assuming care of a new set of patients, despite having received a handoff from the departing hospitalist.[11] Handoffs between emergency physicians and hospitalists have repeatedly been noted to have content omissions and to contribute to adverse events.[7, 12, 21, 22] Ilan et al. videotaped attending handoffs in the intensive care unit and found that they did not follow any of 3 commonly recommended structures; however, this study did not assess the effectiveness of the handoffs.[23] Williams et al. found that the transfer of patient information among surgical team members, including attending surgeons, was suboptimal, and these problems were commonly related to decreased surgeon familiarity with a particular patient, a theme common to hospital medicine, and a contributor to adverse events and decreased efficiency.[24]

This study extends the literature in several ways. By studying overnight events, we generate a comprehensive view of the information sources hospitalists use to care for patients overnight. Interestingly, our results were similar to the overnight information‐gathering habits of trainees in a study of pediatric trainees.[25] Furthermore, by linking each inquiry to the accompanying written sign‐out, we are able to analyze which characteristics of a written sign‐out are associated with sign‐out effectiveness, and we are able to describe the utility of written sign‐out to answer different types of clinical scenarios.

Our data show that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out to care for patients overnight, with the physician note being the most‐utilized secondary reference used by covering physicians. The written sign‐out was most useful for order clarification compared to other topics, and the patient was only seen for 12% of inquiries. Most notable, however, was the suggestion that sign‐outs with more anticipatory guidance were more likely to be effective for overnight care, as were sign‐outs created earlier in the hospital course. Future efforts to improve the utility of the written sign‐out might focus on these items, whether through training or audit/feedback.

The use of electronic handoff tools has been shown to increase the ease of use, efficiency, and perceptions of patient safety and quality in several studies.[3, 26, 27] This study relied on an electronic tool as the only means of information transfer during sign‐out. Without the confounding effect of verbal information transfer, we are better able to understand the efficacy of the written component alone. Nonetheless, most expert opinion statements as well as The Joint Commission include a recommendation for verbal and written components to handoff communication.[8, 20, 28, 29, 30] It is possible that sign‐outs would more often have been rated sufficient if the handoff process had reliably included verbal handoff. Future studies are warranted to compare written‐only to written‐plus‐verbal sign‐out, to determine the added benefit of verbal communication. With a robust EHR, it is also an open question whether sign‐out needs to be sufficient to answer overnight inquiries or whether it would be acceptable or even preferable to have overnight staff consistently review the EHR directly, especially as the physician notes are the most common nonsign‐out reference used. Nonetheless, the fact that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out despite the availability of other information sources suggests that hospitalists find specific benefit in written sign‐out.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, the limited collection time period, and the single‐site nature. The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses only written documents to sign out, so the external validity to programs that use verbal sign‐out is limited. The written‐only nature, however, removes the variable of the discussion at time of sign‐out, improving the purity of the written sign‐out assessment. We did not assess workload, which might have affected sign‐out quality. The interpretation of the composite score is limited, due to little variation in scoring in our sample, as well as lack of validation in other studies. An additional limitation is that sign‐outs are not entirely drafted by the hospitalist attendings. Hospitalists draft the initial sign‐out document, but it is updated on subsequent days by the mid‐level provider under the direction of the hospitalist attending. It is therefore possible that sign‐outs maintained directly by hospitalists would have been of different quality. In this regard it is interesting to note that in a different study of verbal sign‐out we were not able to detect a difference in quality among hospitalists, trainees, and midlevels.[12] Last, hindsight bias may be present, as the covering physician's perspective of the event includes more information than available to the provider creating the sign‐out document.

Overall, we found that attending hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out documents to address overnight inquiries, but those sign‐outs are not reliably effective. Future work to better understand the roles of written and verbal components in sign‐out is needed to help improve the safety of overnight care.

Disclosures

Disclosures: Dr. Horwitz is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Horwitz is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). Dr. Fogerty had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Schoenfeld was a medical student at the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut at the time of the study. She is now a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

- , , , . The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(2):75–80.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , et al. The Veterans Affairs shift change physician‐to‐physician handoff project. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):62–71.

- , . The evolution and future of hospital medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):418–423.

- . The hospitalist movement—time to move on. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2627–2629.

- , , . Invited article: is it time for neurohospitalists? Neurology. 2008;70(15):1282–1288.

- , , , . Survey of obstetric and gynecologic hospitalists and laborists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):177.e171–e174.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48–56.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , , . Understanding communication during hospitalist service changes: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):535–540.

- , , , et al. Development of a handoff evaluation tool for shift‐to‐shift physician handoffs: the handoff CEX. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):191–200.

- , , , , . Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(11):866–872.

- , , , et al. Effect of short call admission on length of stay and quality of care for acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2637–2644.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , et al. An institution‐wide handoff task force to standardise and improve physician handoffs. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(10):863–871.

- , , , , . What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign‐out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248–255.

- , , , . Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(11):1173–1177.

- , , , . A theoretical framework and competency‐based approach to improving handoffs. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):11–14.

- , , . Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(10):884–894.

- , , , , , . Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6):701–710.e704.

- , , , , , . Handover patterns: an observational study of critical care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:11.

- , , , et al. Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):159–169.

- , , , , . Answering questions on call: Pediatric resident physicians' use of handoffs and other resources. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:328–333.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(4):538–545.

- , , , et al. Resident sign‐out and patient hand‐offs: opportunities for improvement. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(2):105–111.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(11):646–655.

- , , , et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):411–418.

- The Joint Commission. 2013 Comprehensive Accreditation Manuals. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2012.

Hospital medicine is a main component of healthcare in the United States and is growing.[1] In 1995, 9% of inpatient care performed by general internists to Medicare patients was provided by hospitalists; by 2006, this had increased to 37%.[2] The estimated 30,000 practicing hospitalists account for 19% of all practicing general internists[2, 3, 4] and have had a major impact on the treatment of inpatients at US hospitals.[5] Other specialties are adopting the hospital‐based physician model.[6, 7] The hospitalist model does have unique challenges. One notable aspect of hospitalist care, which is frequently shift based, is the transfer of care among providers at shift change.

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognizes patient handoffs/sign‐outs as a core competency for hospitalists,[8] but there is little literature evaluating hospitalist sign‐out quality.[9] A systematic review in 2009 found no studies of hospitalist handoffs.[8] Furthermore, early work suggests that hospitalist handoffs are not consistently effective.[10] In a recent survey, 13% of hospitalists reported they had received an incomplete handoff, and 16% of hospitalists reported at least 1 near‐miss attributed to incomplete communication.[11] Last, hospitalists perform no better than housestaff on evaluations of sign‐out quality.[12]

Cross‐coverage situations, in which sign‐out is key, have been shown to place patients at risk.[13, 14] One study showed 7.1 problems related to sign‐out per 100 patient‐days.[15] Failure during sign‐out can ultimately threaten patient safety.[16] Therefore, evaluating the quality of hospitalist sign‐outs by assessing how well the sign‐out prepares the night team for overnight events is necessary to improve hospitalist sign‐outs and ultimately increase patient safety.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study took place at YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH), the primary teaching affiliate for the Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, Connecticut. YNHH is a 966‐bed, urban, academic medical center. The Hospitalist Service is a nonteaching service composed of 56.1 full‐time‐equivalent (FTE) attending physicians and 26.8 FTE midlevel providers. In fiscal year 2012, the YNHH Hospitalist Service cared for 13,764 discharges, or approximately 70% of general medical discharges. Similar patients are cared for by both hospitalists and housestaff. Patients on the hospitalist service are assigned an attending physician as well as a midlevel provider during the daytime. Between the departure of the day team and the arrival of the night team, typically a 2‐hour window, a skeleton crew covers the entire service and admits patients. The same skeleton crew coverage plan exists in the approximately 2.5‐hour morning gap between the departure of the night team and arrival of the day team. Overnight, care is generally provided by attending hospitalist physicians alone. Clinical fellows and internal medicine residents occasionally fill the night hospitalist role.

Sign‐out Procedure

The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses a written sign‐out[17] created via template built into the electronic health record (EHR), Sunrise Clinical Manager (version 5.5; Allscripts, Chicago, IL) and is the major mechanism for shift‐to‐shift information transfer. A free text summary of the patient's medical course and condition is created by the provider preparing the sign‐out, as is a separate list of to do items. The free text box is titled History (general hospital course, new events of the day, overall clinical condition). A representative narrative example is, 87 y/o gentleman PMHx AF on coumadin, diastolic CHF (EF 40%), NIDDM2, first degree AV block, GIB in setting of supratherapeutic INR, depression, COPD p/w worsening low back pain in setting of L1 compression frx of? age. HD stable. An option exists to include a medication list pulled from the active orders in the EHR when the sign‐out report is printed. The sign‐out is typically created by the hospitalist attending on the day of admission and then updated daily by the mid‐level provider under the supervision of the attending physician, in accordance with internal standards set by the service. Formal sign‐out training is included as part of orientation for new hires, and ongoing sign‐out education is provided, as needed, by a physician assistant charged with continuous quality improvement for the entire service. The service maintains an expectation for the entire team to provide accurate and updated sign‐out at every shift change. Attending hospitalists or mid‐level providers update the sign‐out on weekends. Because the day team has generally left the hospital prior to the arrival of the night team, verbal sign‐out occurs rarely. Should a verbal sign‐out be given to the night team, it will be provided by the daytime team directly to the night team either via telephone or the day team member staying in the hospital until arrival of the night team.

Participants

All full‐time and regularly scheduled part‐time attending physicians on the YNHH hospitalist night team were eligible to participate. We excluded temporary physicians on service, including clinical fellows and resident moonlighters. Hospitalists could not participate more than once. Written informed consent was obtained of all hospitalists at the start of their shift.

Data Collection

Hospitalists who consented were provided a single pocket card during their shift. For every inquiry that involved a patient that the hospitalist was covering, the hospitalist recorded who originated the inquiry, the clinical significance, the sufficiency of written sign‐out, which information was used other than the written sign‐out, and information regarding the anticipation of the event by the daytime team (Figure 1).

Data were collected on 6 days and distributed from April 30, 2012 through June 12, 2012. Dates were chosen based on staffing to maximize the number of eligible physicians each night and included both weekdays and weekend days. The written sign‐out for the entire service was printed for each night data collection took place.

Main Predictors

Our main predictor variables were characteristics of the inquiry (topic area, clinical importance of the inquiry as assessed by the hospitalist), characteristics of the patient (days since admission), and characteristics of the written sign‐out (whether it included any anticipatory guidance and a composite quality score). We identified elements of the composite quality score based on prior research and expert recommendations.[8, 18, 19, 20] To create the composite quality score, we gave 1 point for each of the following elements: diagnosis or presenting symptoms, general hospital course (a description of any event occurring during hospitalization but prior to date of data collection), current clinical condition (a description of objective data, symptoms, or stability/trajectory in the last 24 hours), and whether the sign‐out had been updated within the last 24 hours. The composite score could range from 0 to 4.

Main Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome measure was the quality and utility of the written‐only sign‐out as defined via a subjective assessment of sufficiency by the covering physician (ie, whether the written sign‐out was adequate to answer the query without seeking any supplemental information). For this outcome, we excluded inquiries for which hospitalists had determined a sign‐out was not necessary to address the inquiry or event.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used a cutoff of P<0.05 for statistical significance; all tests were 2‐tailed. We assessed characteristics of overnight inquiries using descriptive statistics and determined the association of the main predictors with sufficient sign‐out using 2 tests. We constructed a multivariate logistic regression model using a priori‐determined clinically relevant predictors to test predictors of sign‐out sufficiency. The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University.

RESULTS

Hospitalists recorded 124 inquiries about 96 patients. Altogether, 15 of 19 (79%) eligible hospitalists returned surveys. Of the 96 patients, we obtained the written sign‐out for 68 (71%). The remainder were new patients for whom the sign‐out had not yet been prepared, or patients who had not yet been assigned to the hospitalist service at the time the sign‐out report was printed.

Hospitalists referenced the sign‐out for 89 (74%) inquiries, and the sign‐out was considered sufficient to respond to 27 (30%) of these inquiries (ie, the sign‐out was adequate to answer the inquiry without any supplemental information). Hospitalists physically saw the patient for 14 (12%) inquiries. Nurses were the originator for most inquiries (102 [82%]). The most common inquiry topics were medications (55 [45%]), plan of care (26 [21%]) and clinical changes (26 [21%]). Ninety‐five (77%) inquiries were considered to be somewhat or very clinically important by the hospitalist (Table 1).

| Inquiry originator, No. (% of 124) | |

| Nurse | 102 (82) |

| Patient | 13 (10) |

| Consultant | 6 (5) |

| Respiratory therapy | 3 (2) |

| Inquiry subject, No. (% of 122) | |

| Medication | 55 (45) |

| Plan of care | 26 (21) |

| Clinical change | 26 (21) |

| Order reconciliation | 15 (12) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Clinical importance of inquiry, No. (% of 123) | |

| Very | 33 (27) |

| Somewhat | 62 (50) |

| Not at all | 28 (23) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Sufficiency of sign‐out alone in answering inquiry, No. (% of 121) | |

| Yes | 27 (22) |

| No | 62 (51) |

| Sign‐out not necessary for inquiry | 32 (26) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Days since admission, No. (% of 124) | |

| Less than 2 | 69 (44.4) |

| 2 or more | 55 (55.6) |

| Reference(s) used when sign‐out insufficient, No. (% of 62) | |

| Physician notes | 37 (60) |

| Nurse | 11 (18) |

| Labs/studies | 10 (16) |

| Orders | 9 (15) |

| Patient | 7 (11) |

| Other | 7 (11) |

| Was the event predicted by the primary team? No. (% of 119) | |

| Yes | 17 (14) |

| No | 102 (86) |

| Missing | 5 |

| If no, could this event have been predicted, No. (% of 102) | |

| Yes | 47 (46) |

| No | 55 (54) |

| Of all events that could have been predicted, how many were predicted? No. (% of 64) | |

| Predicted | 17 (27) |

| Not predicted | 47 (73) |

| Did you physically see the patient? No. (% of 117) | |

| Yes | 14 (12) |

| No | 103 (88) |

| Missing | 7 |

| Composite score, No. (% of 68) | |

| 0 or 1 | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 3 (4) |

| 3 | 31 (46) |

| 4 | 34 (50) |

| Anticipatory guidance/to‐do tasks, No. (% of 96) | |

| 0 | 69(72) |

| 1 | 21 (22) |

| 2 or more | 6 (6) |

No written sign‐outs had a composite score of 0 or 1; 3 (4%) had a composite score of 2; 31 (46%) had a composite score of 3; and 34 (50%) had a composite score of 4. Seventy‐two percent of written sign‐outs included neither anticipatory guidance nor tasks, 21% had 1 anticipatory guidance item or task, and 6% had 2 or more anticipatory guidance items and/or tasks.

The primary team caring for a patient did not predict 102 (86%) inquiries, and hospitalists rated 47 (46%) of those unpredicted events as possible for the primary team to predict. Five responses to this question were incomplete and excluded. Of the 64 events predicted by the primary team or rated as predictable by the night hospitalists, 17 (27%) were predicted by the primary team (Table 1).

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation to answer the majority of order reconciliation inquiries (5 [71%]), but was less effective at helping to answer inquiries about clinical change (7 [29%]), medications (10 [28%]), and plan of care (5 [24%]) (P=0.001). (Table 2) Ninety‐five events were rated as either very or somewhat clinically important, but this did not affect the likelihood of sign‐out being sufficient in isolation relative to the not at all clinically important group. Specifically, 33% of sign‐outs were rated sufficient in the very important group, 19% in the somewhat important group, and 50% in the not at all group (P=0.059).

| Predictor | Number of inquiries (%) for which sign‐out was sufficient in isolationb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Question topic | 0.001 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | 5/7 (71) | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 7/24 (29) | ||

| Medicationa (with clinical question) | 10/36 (28) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, procedure) | 5/21 (24) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.059 | ||

| Not at all | 8 (50) | ||

| Somewhat | 8 (19) | ||

| Very | 10 (33) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.015 | ||

| Less than 2 days | 21 (40) | ||

| 2 or more days | 6 (16) | ||

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.006 | ||

| 2 or more | 3 (60) | ||

| 1 | 3 (14) | ||

| 0 | 21 (34) | ||

| Composite score | 0.144 | ||

| <4 | 5 (15) | ||

| 4 | 10 (29) | ||

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation more frequently for inquiries about patients admitted <2 days prior to data collection than for inquiries about patients admitted more than 2 days prior to data collection (21 [40%] vs 6 [16%], respectively) (P=0.015) (Table 2).

Sign‐outs with 2 or more anticipatory guidance items were considered sufficient in isolation more often than sign‐outs with 1 or fewer anticipatory guidance item (60% for 2 or more, 14% for 1, 34% for 0; P=0.006) (Table 2). The composite score was grouped into 2 categoriesscore <4 and score=4with no statistical difference in sign‐out sufficiency between the 2 groups (P=0.22) (Table 2).

In multivariable analysis, no predictor variable was significantly associated with sufficient sign‐out (Table 3).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question topic | 0.58 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | Reference | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 0.29 (0.01 6.70) | ||

| Medication (+/‐ vitals or symptoms) | 0.17 (0.01 3.83) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, IV, CPAP, procedure) | 0.15 (0.01 3.37) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.85 | ||

| Not at All | Reference | ||

| Somewhat | 0.69 (0.12 4.04) | ||

| Very | 0.57 (0.08 3.88) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.332 (0.09 1.19) | 0.074 | |

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.26 | ||

| 2 or more | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.13 (0.01 1.51) | ||

| 0 | 0.21 (0.02 2.11) | ||

| Composite Score | 0.22 | ||

| <4 | Reference | ||

| 4 | 2.2 (0.62 7.77) |

DISCUSSION

In this study of written sign‐out among hospitalists and physician‐extenders on a hospitalist service, we found that the sign‐out was used to answer three‐quarters of overnight inquiries, despite the advanced level of training (completion of all postgraduate medical education) of the covering clinicians and the presence of a robust EHR. The effectiveness of the written sign‐out, however, was not as consistently high as its use. Overall, the sign‐out was sufficient to answer less than a third of inquiries in which it was referenced. Thus, although most studies of sign‐out quality have focused on trainees, our results make it clear that hospitalists also rely on sign‐out, and its effectiveness can be improved.

There are few studies of attending‐level sign‐outs. Hinami et al. found that nearly 1 in 5 hospitalists was uncertain of the care plan after assuming care of a new set of patients, despite having received a handoff from the departing hospitalist.[11] Handoffs between emergency physicians and hospitalists have repeatedly been noted to have content omissions and to contribute to adverse events.[7, 12, 21, 22] Ilan et al. videotaped attending handoffs in the intensive care unit and found that they did not follow any of 3 commonly recommended structures; however, this study did not assess the effectiveness of the handoffs.[23] Williams et al. found that the transfer of patient information among surgical team members, including attending surgeons, was suboptimal, and these problems were commonly related to decreased surgeon familiarity with a particular patient, a theme common to hospital medicine, and a contributor to adverse events and decreased efficiency.[24]

This study extends the literature in several ways. By studying overnight events, we generate a comprehensive view of the information sources hospitalists use to care for patients overnight. Interestingly, our results were similar to the overnight information‐gathering habits of trainees in a study of pediatric trainees.[25] Furthermore, by linking each inquiry to the accompanying written sign‐out, we are able to analyze which characteristics of a written sign‐out are associated with sign‐out effectiveness, and we are able to describe the utility of written sign‐out to answer different types of clinical scenarios.

Our data show that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out to care for patients overnight, with the physician note being the most‐utilized secondary reference used by covering physicians. The written sign‐out was most useful for order clarification compared to other topics, and the patient was only seen for 12% of inquiries. Most notable, however, was the suggestion that sign‐outs with more anticipatory guidance were more likely to be effective for overnight care, as were sign‐outs created earlier in the hospital course. Future efforts to improve the utility of the written sign‐out might focus on these items, whether through training or audit/feedback.

The use of electronic handoff tools has been shown to increase the ease of use, efficiency, and perceptions of patient safety and quality in several studies.[3, 26, 27] This study relied on an electronic tool as the only means of information transfer during sign‐out. Without the confounding effect of verbal information transfer, we are better able to understand the efficacy of the written component alone. Nonetheless, most expert opinion statements as well as The Joint Commission include a recommendation for verbal and written components to handoff communication.[8, 20, 28, 29, 30] It is possible that sign‐outs would more often have been rated sufficient if the handoff process had reliably included verbal handoff. Future studies are warranted to compare written‐only to written‐plus‐verbal sign‐out, to determine the added benefit of verbal communication. With a robust EHR, it is also an open question whether sign‐out needs to be sufficient to answer overnight inquiries or whether it would be acceptable or even preferable to have overnight staff consistently review the EHR directly, especially as the physician notes are the most common nonsign‐out reference used. Nonetheless, the fact that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out despite the availability of other information sources suggests that hospitalists find specific benefit in written sign‐out.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, the limited collection time period, and the single‐site nature. The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses only written documents to sign out, so the external validity to programs that use verbal sign‐out is limited. The written‐only nature, however, removes the variable of the discussion at time of sign‐out, improving the purity of the written sign‐out assessment. We did not assess workload, which might have affected sign‐out quality. The interpretation of the composite score is limited, due to little variation in scoring in our sample, as well as lack of validation in other studies. An additional limitation is that sign‐outs are not entirely drafted by the hospitalist attendings. Hospitalists draft the initial sign‐out document, but it is updated on subsequent days by the mid‐level provider under the direction of the hospitalist attending. It is therefore possible that sign‐outs maintained directly by hospitalists would have been of different quality. In this regard it is interesting to note that in a different study of verbal sign‐out we were not able to detect a difference in quality among hospitalists, trainees, and midlevels.[12] Last, hindsight bias may be present, as the covering physician's perspective of the event includes more information than available to the provider creating the sign‐out document.

Overall, we found that attending hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out documents to address overnight inquiries, but those sign‐outs are not reliably effective. Future work to better understand the roles of written and verbal components in sign‐out is needed to help improve the safety of overnight care.

Disclosures

Disclosures: Dr. Horwitz is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Horwitz is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). Dr. Fogerty had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Schoenfeld was a medical student at the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut at the time of the study. She is now a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

Hospital medicine is a main component of healthcare in the United States and is growing.[1] In 1995, 9% of inpatient care performed by general internists to Medicare patients was provided by hospitalists; by 2006, this had increased to 37%.[2] The estimated 30,000 practicing hospitalists account for 19% of all practicing general internists[2, 3, 4] and have had a major impact on the treatment of inpatients at US hospitals.[5] Other specialties are adopting the hospital‐based physician model.[6, 7] The hospitalist model does have unique challenges. One notable aspect of hospitalist care, which is frequently shift based, is the transfer of care among providers at shift change.

The Society of Hospital Medicine recognizes patient handoffs/sign‐outs as a core competency for hospitalists,[8] but there is little literature evaluating hospitalist sign‐out quality.[9] A systematic review in 2009 found no studies of hospitalist handoffs.[8] Furthermore, early work suggests that hospitalist handoffs are not consistently effective.[10] In a recent survey, 13% of hospitalists reported they had received an incomplete handoff, and 16% of hospitalists reported at least 1 near‐miss attributed to incomplete communication.[11] Last, hospitalists perform no better than housestaff on evaluations of sign‐out quality.[12]

Cross‐coverage situations, in which sign‐out is key, have been shown to place patients at risk.[13, 14] One study showed 7.1 problems related to sign‐out per 100 patient‐days.[15] Failure during sign‐out can ultimately threaten patient safety.[16] Therefore, evaluating the quality of hospitalist sign‐outs by assessing how well the sign‐out prepares the night team for overnight events is necessary to improve hospitalist sign‐outs and ultimately increase patient safety.

METHODS

Study Setting

The study took place at YaleNew Haven Hospital (YNHH), the primary teaching affiliate for the Yale School of Medicine, in New Haven, Connecticut. YNHH is a 966‐bed, urban, academic medical center. The Hospitalist Service is a nonteaching service composed of 56.1 full‐time‐equivalent (FTE) attending physicians and 26.8 FTE midlevel providers. In fiscal year 2012, the YNHH Hospitalist Service cared for 13,764 discharges, or approximately 70% of general medical discharges. Similar patients are cared for by both hospitalists and housestaff. Patients on the hospitalist service are assigned an attending physician as well as a midlevel provider during the daytime. Between the departure of the day team and the arrival of the night team, typically a 2‐hour window, a skeleton crew covers the entire service and admits patients. The same skeleton crew coverage plan exists in the approximately 2.5‐hour morning gap between the departure of the night team and arrival of the day team. Overnight, care is generally provided by attending hospitalist physicians alone. Clinical fellows and internal medicine residents occasionally fill the night hospitalist role.

Sign‐out Procedure

The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses a written sign‐out[17] created via template built into the electronic health record (EHR), Sunrise Clinical Manager (version 5.5; Allscripts, Chicago, IL) and is the major mechanism for shift‐to‐shift information transfer. A free text summary of the patient's medical course and condition is created by the provider preparing the sign‐out, as is a separate list of to do items. The free text box is titled History (general hospital course, new events of the day, overall clinical condition). A representative narrative example is, 87 y/o gentleman PMHx AF on coumadin, diastolic CHF (EF 40%), NIDDM2, first degree AV block, GIB in setting of supratherapeutic INR, depression, COPD p/w worsening low back pain in setting of L1 compression frx of? age. HD stable. An option exists to include a medication list pulled from the active orders in the EHR when the sign‐out report is printed. The sign‐out is typically created by the hospitalist attending on the day of admission and then updated daily by the mid‐level provider under the supervision of the attending physician, in accordance with internal standards set by the service. Formal sign‐out training is included as part of orientation for new hires, and ongoing sign‐out education is provided, as needed, by a physician assistant charged with continuous quality improvement for the entire service. The service maintains an expectation for the entire team to provide accurate and updated sign‐out at every shift change. Attending hospitalists or mid‐level providers update the sign‐out on weekends. Because the day team has generally left the hospital prior to the arrival of the night team, verbal sign‐out occurs rarely. Should a verbal sign‐out be given to the night team, it will be provided by the daytime team directly to the night team either via telephone or the day team member staying in the hospital until arrival of the night team.

Participants

All full‐time and regularly scheduled part‐time attending physicians on the YNHH hospitalist night team were eligible to participate. We excluded temporary physicians on service, including clinical fellows and resident moonlighters. Hospitalists could not participate more than once. Written informed consent was obtained of all hospitalists at the start of their shift.

Data Collection

Hospitalists who consented were provided a single pocket card during their shift. For every inquiry that involved a patient that the hospitalist was covering, the hospitalist recorded who originated the inquiry, the clinical significance, the sufficiency of written sign‐out, which information was used other than the written sign‐out, and information regarding the anticipation of the event by the daytime team (Figure 1).

Data were collected on 6 days and distributed from April 30, 2012 through June 12, 2012. Dates were chosen based on staffing to maximize the number of eligible physicians each night and included both weekdays and weekend days. The written sign‐out for the entire service was printed for each night data collection took place.

Main Predictors

Our main predictor variables were characteristics of the inquiry (topic area, clinical importance of the inquiry as assessed by the hospitalist), characteristics of the patient (days since admission), and characteristics of the written sign‐out (whether it included any anticipatory guidance and a composite quality score). We identified elements of the composite quality score based on prior research and expert recommendations.[8, 18, 19, 20] To create the composite quality score, we gave 1 point for each of the following elements: diagnosis or presenting symptoms, general hospital course (a description of any event occurring during hospitalization but prior to date of data collection), current clinical condition (a description of objective data, symptoms, or stability/trajectory in the last 24 hours), and whether the sign‐out had been updated within the last 24 hours. The composite score could range from 0 to 4.

Main Outcome Measures

Our primary outcome measure was the quality and utility of the written‐only sign‐out as defined via a subjective assessment of sufficiency by the covering physician (ie, whether the written sign‐out was adequate to answer the query without seeking any supplemental information). For this outcome, we excluded inquiries for which hospitalists had determined a sign‐out was not necessary to address the inquiry or event.

Statistical Analysis

Data analysis was conducted using SAS 9.2 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We used a cutoff of P<0.05 for statistical significance; all tests were 2‐tailed. We assessed characteristics of overnight inquiries using descriptive statistics and determined the association of the main predictors with sufficient sign‐out using 2 tests. We constructed a multivariate logistic regression model using a priori‐determined clinically relevant predictors to test predictors of sign‐out sufficiency. The study was approved by the Human Investigation Committee of Yale University.

RESULTS

Hospitalists recorded 124 inquiries about 96 patients. Altogether, 15 of 19 (79%) eligible hospitalists returned surveys. Of the 96 patients, we obtained the written sign‐out for 68 (71%). The remainder were new patients for whom the sign‐out had not yet been prepared, or patients who had not yet been assigned to the hospitalist service at the time the sign‐out report was printed.

Hospitalists referenced the sign‐out for 89 (74%) inquiries, and the sign‐out was considered sufficient to respond to 27 (30%) of these inquiries (ie, the sign‐out was adequate to answer the inquiry without any supplemental information). Hospitalists physically saw the patient for 14 (12%) inquiries. Nurses were the originator for most inquiries (102 [82%]). The most common inquiry topics were medications (55 [45%]), plan of care (26 [21%]) and clinical changes (26 [21%]). Ninety‐five (77%) inquiries were considered to be somewhat or very clinically important by the hospitalist (Table 1).

| Inquiry originator, No. (% of 124) | |

| Nurse | 102 (82) |

| Patient | 13 (10) |

| Consultant | 6 (5) |

| Respiratory therapy | 3 (2) |

| Inquiry subject, No. (% of 122) | |

| Medication | 55 (45) |

| Plan of care | 26 (21) |

| Clinical change | 26 (21) |

| Order reconciliation | 15 (12) |

| Missing | 2 |

| Clinical importance of inquiry, No. (% of 123) | |

| Very | 33 (27) |

| Somewhat | 62 (50) |

| Not at all | 28 (23) |

| Missing | 1 |

| Sufficiency of sign‐out alone in answering inquiry, No. (% of 121) | |

| Yes | 27 (22) |

| No | 62 (51) |

| Sign‐out not necessary for inquiry | 32 (26) |

| Missing | 3 |

| Days since admission, No. (% of 124) | |

| Less than 2 | 69 (44.4) |

| 2 or more | 55 (55.6) |

| Reference(s) used when sign‐out insufficient, No. (% of 62) | |

| Physician notes | 37 (60) |

| Nurse | 11 (18) |

| Labs/studies | 10 (16) |

| Orders | 9 (15) |

| Patient | 7 (11) |

| Other | 7 (11) |

| Was the event predicted by the primary team? No. (% of 119) | |

| Yes | 17 (14) |

| No | 102 (86) |

| Missing | 5 |

| If no, could this event have been predicted, No. (% of 102) | |

| Yes | 47 (46) |

| No | 55 (54) |

| Of all events that could have been predicted, how many were predicted? No. (% of 64) | |

| Predicted | 17 (27) |

| Not predicted | 47 (73) |

| Did you physically see the patient? No. (% of 117) | |

| Yes | 14 (12) |

| No | 103 (88) |

| Missing | 7 |

| Composite score, No. (% of 68) | |

| 0 or 1 | 0 (0) |

| 2 | 3 (4) |

| 3 | 31 (46) |

| 4 | 34 (50) |

| Anticipatory guidance/to‐do tasks, No. (% of 96) | |

| 0 | 69(72) |

| 1 | 21 (22) |

| 2 or more | 6 (6) |

No written sign‐outs had a composite score of 0 or 1; 3 (4%) had a composite score of 2; 31 (46%) had a composite score of 3; and 34 (50%) had a composite score of 4. Seventy‐two percent of written sign‐outs included neither anticipatory guidance nor tasks, 21% had 1 anticipatory guidance item or task, and 6% had 2 or more anticipatory guidance items and/or tasks.

The primary team caring for a patient did not predict 102 (86%) inquiries, and hospitalists rated 47 (46%) of those unpredicted events as possible for the primary team to predict. Five responses to this question were incomplete and excluded. Of the 64 events predicted by the primary team or rated as predictable by the night hospitalists, 17 (27%) were predicted by the primary team (Table 1).

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation to answer the majority of order reconciliation inquiries (5 [71%]), but was less effective at helping to answer inquiries about clinical change (7 [29%]), medications (10 [28%]), and plan of care (5 [24%]) (P=0.001). (Table 2) Ninety‐five events were rated as either very or somewhat clinically important, but this did not affect the likelihood of sign‐out being sufficient in isolation relative to the not at all clinically important group. Specifically, 33% of sign‐outs were rated sufficient in the very important group, 19% in the somewhat important group, and 50% in the not at all group (P=0.059).

| Predictor | Number of inquiries (%) for which sign‐out was sufficient in isolationb | p value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| Question topic | 0.001 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | 5/7 (71) | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 7/24 (29) | ||

| Medicationa (with clinical question) | 10/36 (28) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, procedure) | 5/21 (24) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.059 | ||

| Not at all | 8 (50) | ||

| Somewhat | 8 (19) | ||

| Very | 10 (33) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.015 | ||

| Less than 2 days | 21 (40) | ||

| 2 or more days | 6 (16) | ||

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.006 | ||

| 2 or more | 3 (60) | ||

| 1 | 3 (14) | ||

| 0 | 21 (34) | ||

| Composite score | 0.144 | ||

| <4 | 5 (15) | ||

| 4 | 10 (29) | ||

Sign‐out was considered sufficient in isolation more frequently for inquiries about patients admitted <2 days prior to data collection than for inquiries about patients admitted more than 2 days prior to data collection (21 [40%] vs 6 [16%], respectively) (P=0.015) (Table 2).

Sign‐outs with 2 or more anticipatory guidance items were considered sufficient in isolation more often than sign‐outs with 1 or fewer anticipatory guidance item (60% for 2 or more, 14% for 1, 34% for 0; P=0.006) (Table 2). The composite score was grouped into 2 categoriesscore <4 and score=4with no statistical difference in sign‐out sufficiency between the 2 groups (P=0.22) (Table 2).

In multivariable analysis, no predictor variable was significantly associated with sufficient sign‐out (Table 3).

| Adjusted OR (95% CI) | p value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Question topic | 0.58 | ||

| Order reconciliation (oxygen/telemetry) | Reference | ||

| Clinical change (vitals, symptoms, labs) | 0.29 (0.01 6.70) | ||

| Medication (+/‐ vitals or symptoms) | 0.17 (0.01 3.83) | ||

| Plan of care (discharge, goals of care, IV, CPAP, procedure) | 0.15 (0.01 3.37) | ||

| Clinically important | 0.85 | ||

| Not at All | Reference | ||

| Somewhat | 0.69 (0.12 4.04) | ||

| Very | 0.57 (0.08 3.88) | ||

| Days since admission | 0.332 (0.09 1.19) | 0.074 | |

| Anticipatory guidance and tasks | 0.26 | ||

| 2 or more | Reference | ||

| 1 | 0.13 (0.01 1.51) | ||

| 0 | 0.21 (0.02 2.11) | ||

| Composite Score | 0.22 | ||

| <4 | Reference | ||

| 4 | 2.2 (0.62 7.77) |

DISCUSSION

In this study of written sign‐out among hospitalists and physician‐extenders on a hospitalist service, we found that the sign‐out was used to answer three‐quarters of overnight inquiries, despite the advanced level of training (completion of all postgraduate medical education) of the covering clinicians and the presence of a robust EHR. The effectiveness of the written sign‐out, however, was not as consistently high as its use. Overall, the sign‐out was sufficient to answer less than a third of inquiries in which it was referenced. Thus, although most studies of sign‐out quality have focused on trainees, our results make it clear that hospitalists also rely on sign‐out, and its effectiveness can be improved.

There are few studies of attending‐level sign‐outs. Hinami et al. found that nearly 1 in 5 hospitalists was uncertain of the care plan after assuming care of a new set of patients, despite having received a handoff from the departing hospitalist.[11] Handoffs between emergency physicians and hospitalists have repeatedly been noted to have content omissions and to contribute to adverse events.[7, 12, 21, 22] Ilan et al. videotaped attending handoffs in the intensive care unit and found that they did not follow any of 3 commonly recommended structures; however, this study did not assess the effectiveness of the handoffs.[23] Williams et al. found that the transfer of patient information among surgical team members, including attending surgeons, was suboptimal, and these problems were commonly related to decreased surgeon familiarity with a particular patient, a theme common to hospital medicine, and a contributor to adverse events and decreased efficiency.[24]

This study extends the literature in several ways. By studying overnight events, we generate a comprehensive view of the information sources hospitalists use to care for patients overnight. Interestingly, our results were similar to the overnight information‐gathering habits of trainees in a study of pediatric trainees.[25] Furthermore, by linking each inquiry to the accompanying written sign‐out, we are able to analyze which characteristics of a written sign‐out are associated with sign‐out effectiveness, and we are able to describe the utility of written sign‐out to answer different types of clinical scenarios.

Our data show that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out to care for patients overnight, with the physician note being the most‐utilized secondary reference used by covering physicians. The written sign‐out was most useful for order clarification compared to other topics, and the patient was only seen for 12% of inquiries. Most notable, however, was the suggestion that sign‐outs with more anticipatory guidance were more likely to be effective for overnight care, as were sign‐outs created earlier in the hospital course. Future efforts to improve the utility of the written sign‐out might focus on these items, whether through training or audit/feedback.

The use of electronic handoff tools has been shown to increase the ease of use, efficiency, and perceptions of patient safety and quality in several studies.[3, 26, 27] This study relied on an electronic tool as the only means of information transfer during sign‐out. Without the confounding effect of verbal information transfer, we are better able to understand the efficacy of the written component alone. Nonetheless, most expert opinion statements as well as The Joint Commission include a recommendation for verbal and written components to handoff communication.[8, 20, 28, 29, 30] It is possible that sign‐outs would more often have been rated sufficient if the handoff process had reliably included verbal handoff. Future studies are warranted to compare written‐only to written‐plus‐verbal sign‐out, to determine the added benefit of verbal communication. With a robust EHR, it is also an open question whether sign‐out needs to be sufficient to answer overnight inquiries or whether it would be acceptable or even preferable to have overnight staff consistently review the EHR directly, especially as the physician notes are the most common nonsign‐out reference used. Nonetheless, the fact that hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out despite the availability of other information sources suggests that hospitalists find specific benefit in written sign‐out.

Limitations of this study include the relatively small sample size, the limited collection time period, and the single‐site nature. The YNHH Hospitalist Service uses only written documents to sign out, so the external validity to programs that use verbal sign‐out is limited. The written‐only nature, however, removes the variable of the discussion at time of sign‐out, improving the purity of the written sign‐out assessment. We did not assess workload, which might have affected sign‐out quality. The interpretation of the composite score is limited, due to little variation in scoring in our sample, as well as lack of validation in other studies. An additional limitation is that sign‐outs are not entirely drafted by the hospitalist attendings. Hospitalists draft the initial sign‐out document, but it is updated on subsequent days by the mid‐level provider under the direction of the hospitalist attending. It is therefore possible that sign‐outs maintained directly by hospitalists would have been of different quality. In this regard it is interesting to note that in a different study of verbal sign‐out we were not able to detect a difference in quality among hospitalists, trainees, and midlevels.[12] Last, hindsight bias may be present, as the covering physician's perspective of the event includes more information than available to the provider creating the sign‐out document.

Overall, we found that attending hospitalists rely heavily on written sign‐out documents to address overnight inquiries, but those sign‐outs are not reliably effective. Future work to better understand the roles of written and verbal components in sign‐out is needed to help improve the safety of overnight care.

Disclosures

Disclosures: Dr. Horwitz is supported by the National Institute on Aging (K08 AG038336) and by the American Federation for Aging Research through the Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award Program. Dr. Horwitz is also a Pepper Scholar with support from the Claude D. Pepper Older Americans Independence Center at Yale University School of Medicine (#P30AG021342 NIH/NIA). Dr. Fogerty had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis. The authors do not have conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Schoenfeld was a medical student at the Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, Connecticut at the time of the study. She is now a resident at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, Massachusetts.

- , , , . The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(2):75–80.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , et al. The Veterans Affairs shift change physician‐to‐physician handoff project. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):62–71.

- , . The evolution and future of hospital medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):418–423.

- . The hospitalist movement—time to move on. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2627–2629.

- , , . Invited article: is it time for neurohospitalists? Neurology. 2008;70(15):1282–1288.

- , , , . Survey of obstetric and gynecologic hospitalists and laborists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):177.e171–e174.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48–56.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , , . Understanding communication during hospitalist service changes: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):535–540.

- , , , et al. Development of a handoff evaluation tool for shift‐to‐shift physician handoffs: the handoff CEX. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):191–200.

- , , , , . Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(11):866–872.

- , , , et al. Effect of short call admission on length of stay and quality of care for acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2637–2644.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , et al. An institution‐wide handoff task force to standardise and improve physician handoffs. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(10):863–871.

- , , , , . What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign‐out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248–255.

- , , , . Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(11):1173–1177.

- , , , . A theoretical framework and competency‐based approach to improving handoffs. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):11–14.

- , , . Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(10):884–894.

- , , , , , . Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6):701–710.e704.

- , , , , , . Handover patterns: an observational study of critical care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:11.

- , , , et al. Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):159–169.

- , , , , . Answering questions on call: Pediatric resident physicians' use of handoffs and other resources. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:328–333.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(4):538–545.

- , , , et al. Resident sign‐out and patient hand‐offs: opportunities for improvement. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(2):105–111.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(11):646–655.

- , , , et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):411–418.

- The Joint Commission. 2013 Comprehensive Accreditation Manuals. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2012.

- , , , . The status of hospital medicine groups in the United States. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(2):75–80.

- , , , . Growth in the care of older patients by hospitalists in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(11):1102–1112.

- , , , et al. The Veterans Affairs shift change physician‐to‐physician handoff project. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2010;36(2):62–71.

- , . The evolution and future of hospital medicine. Mt Sinai J Med. 2008;75(5):418–423.

- . The hospitalist movement—time to move on. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2627–2629.

- , , . Invited article: is it time for neurohospitalists? Neurology. 2008;70(15):1282–1288.

- , , , . Survey of obstetric and gynecologic hospitalists and laborists. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2010;203(2):177.e171–e174.

- , , , , , . Hospitalist handoffs: a systematic review and task force recommendations. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(7):433–440.

- , , , , . Core competencies in hospital medicine: development and methodology. J Hosp Med. 2006;1(1):48–56.

- , , , , . Gaining efficiency and satisfaction in the handoff process. J Hosp Med. 2010;5(9):547–552.

- , , , . Understanding communication during hospitalist service changes: a mixed methods study. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(9):535–540.

- , , , et al. Development of a handoff evaluation tool for shift‐to‐shift physician handoffs: the handoff CEX. J Hosp Med. 2013;8(4):191–200.

- , , , , . Does housestaff discontinuity of care increase the risk for preventable adverse events? Ann Intern Med. 1994;121(11):866–872.

- , , , et al. Effect of short call admission on length of stay and quality of care for acute decompensated heart failure. Circulation. 2008;117(20):2637–2644.

- , , , , . Consequences of inadequate sign‐out for patient care. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(16):1755–1760.

- , , , , . Communication failures in patient sign‐out and suggestions for improvement: a critical incident analysis. Qual Saf Health Care. 2005;14(6):401–407.

- , , , et al. An institution‐wide handoff task force to standardise and improve physician handoffs. BMJ Qual Saf. 2012;21(10):863–871.

- , , , , . What are covering doctors told about their patients? Analysis of sign‐out among internal medicine house staff. Qual Saf Health Care. 2009;18(4):248–255.

- , , , . Transfers of patient care between house staff on internal medicine wards: a national survey. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166(11):1173–1177.

- , , , . A theoretical framework and competency‐based approach to improving handoffs. Qual Saf Health Care. 2008;17(1):11–14.

- , , . Communicating in the “gray zone”: perceptions about emergency physician hospitalist handoffs and patient safety. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(10):884–894.

- , , , , , . Dropping the baton: a qualitative analysis of failures during the transition from emergency department to inpatient care. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;53(6):701–710.e704.

- , , , , , . Handover patterns: an observational study of critical care physicians. BMC Health Serv Res. 2012;12:11.

- , , , et al. Surgeon information transfer and communication: factors affecting quality and efficiency of inpatient care. Ann Surg. 2007;245(2):159–169.

- , , , , . Answering questions on call: Pediatric resident physicians' use of handoffs and other resources. J Hosp Med. 2013;8:328–333.

- , , , , . A randomized, controlled trial evaluating the impact of a computerized rounding and sign‐out system on continuity of care and resident work hours. J Am Coll Surg. 2005;200(4):538–545.

- , , , et al. Resident sign‐out and patient hand‐offs: opportunities for improvement. Teach Learn Med. 2011;23(2):105–111.

- , . A model for building a standardized hand‐off protocol. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2006;32(11):646–655.

- , , , et al. The patient handoff: a comprehensive curricular blueprint for resident education to improve continuity of care. Acad Med. 2012;87(4):411–418.

- The Joint Commission. 2013 Comprehensive Accreditation Manuals. Oak Brook, IL: The Joint Commission; 2012.

© 2013 Society of Hospital Medicine

Stearic acid

Stearic acid, a waxlike fatty acid also known as octadecanoic acid, is an important component of stratum corneum lipids. Stearic acid is also found in cocoa butter, shea butter, and other vegetable fats, as well as animal tallow. As an FDA-approved ingredient in several cosmetic products, it is used as a surfactant and emulsifying agent for fragrance and as the base for other fatty acid ingredients that are synthesized into emollients and lubricants. Stearic acid is used most often to thicken and retain the shape of soaps (indirectly, through saponification of triglycerides composed of stearic acid esters), and it is also used in shampoos, shaving creams, and detergents.

There is limited evidence for the potential of exogenously produced stearic acid to play a significant role as a topical dermatologic therapeutic agent. Stearic acid is thought to be associated with behenyltrimethylammonium chloride through salt bridges, and the combination is believed to have the capacity to build bilayer vesicles with the aid of hinokitiol (beta-thujaplicin), a natural monoterpenoid found in the wood of trees in the Cupressaceae family that has been shown to exert topical inhibitory activity against Chlamydia trachomatis (Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2005;49:2519-21). These vesicles, used to enhance the skin permeation of hinokitiol, were tested in hairless mice and appear to have the potential to promote hair growth (Drug Dev. Ind. Pharm. 2010;36:556-62).