User login

How To Maximize a Minimal Incision

Mini-incision carotid surgery was first reported (not necessarily performed) by Ascher et al. in 2005. In light of this report and an ever-growing patient demand for minimally invasive procedures, it is surprising that this procedure has not been widely adopted by the vascular surgical community. The reasons for this are probably multifactorial and may include a concern that cranial nerve injuries are more likely to occur as well as an added difficulty in placing a shunt or sewing in a patch. These concerns are mitigated by a thorough knowledge of the usual and variant anatomy of this area and a broad experience in carotid surgery. If performed properly, mini-incision is not synonymous with mini exposure carotid surgery.

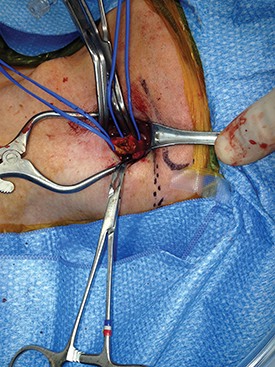

It is important to identify the carotid bifurcation with duplex ultrasound prior to making the skin incision. It is my preference to make a vertical skin incision which extends from approximately 2 cm above to below the carotid bifurcation at a slight outside to inside angle to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (some surgeons prefer a transverse skin incision). The platysma muscle is identified and divided for a short distance between forceps.

The edges of the platysma are grasped with DeBakey forceps while the skin is retracted as far inferiorly as possible.

The platysma is then divided to this point following which this is repeated at the superior aspect of the wound. The extended division of the platysma is what allows for an exposure equal to that of a much larger incision. Now adequate visualization of the common and internal carotid arteries is achieved by use of a small retractor applied alternately to the inferior and superior ends of the wound respectively.

Using this technique, I have easily been able to perform both standard and eversion endarterectomies (as in photo), place a shunt when necessary, and/or sew on a carotid patch.

Once completed the platysma is closed with an absorbable suture and skin is closed with an absorbable monofilament suture.

In my experience, patients have less postoperative pain than those with a larger neck incision. They are also exceptionally pleased with the small, barely visible, neck scar. Finally, I have used the mini-incision for my carotid surgeries for more than 10 years during which time no patient has suffered a permanent cranial nerve injury.

Dr. Dietzek is the chief of the vascular and endovascular surgery section and the Linda and Stephen R. Cohen chair in vascular surgery at Danbury Hospital, Danbury Conn. He is also a clinical associate professor of surgery at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to submit a similarly useful Tips and Tricks, contact us at [email protected].

Mini-incision carotid surgery was first reported (not necessarily performed) by Ascher et al. in 2005. In light of this report and an ever-growing patient demand for minimally invasive procedures, it is surprising that this procedure has not been widely adopted by the vascular surgical community. The reasons for this are probably multifactorial and may include a concern that cranial nerve injuries are more likely to occur as well as an added difficulty in placing a shunt or sewing in a patch. These concerns are mitigated by a thorough knowledge of the usual and variant anatomy of this area and a broad experience in carotid surgery. If performed properly, mini-incision is not synonymous with mini exposure carotid surgery.

It is important to identify the carotid bifurcation with duplex ultrasound prior to making the skin incision. It is my preference to make a vertical skin incision which extends from approximately 2 cm above to below the carotid bifurcation at a slight outside to inside angle to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (some surgeons prefer a transverse skin incision). The platysma muscle is identified and divided for a short distance between forceps.

The edges of the platysma are grasped with DeBakey forceps while the skin is retracted as far inferiorly as possible.

The platysma is then divided to this point following which this is repeated at the superior aspect of the wound. The extended division of the platysma is what allows for an exposure equal to that of a much larger incision. Now adequate visualization of the common and internal carotid arteries is achieved by use of a small retractor applied alternately to the inferior and superior ends of the wound respectively.

Using this technique, I have easily been able to perform both standard and eversion endarterectomies (as in photo), place a shunt when necessary, and/or sew on a carotid patch.

Once completed the platysma is closed with an absorbable suture and skin is closed with an absorbable monofilament suture.

In my experience, patients have less postoperative pain than those with a larger neck incision. They are also exceptionally pleased with the small, barely visible, neck scar. Finally, I have used the mini-incision for my carotid surgeries for more than 10 years during which time no patient has suffered a permanent cranial nerve injury.

Dr. Dietzek is the chief of the vascular and endovascular surgery section and the Linda and Stephen R. Cohen chair in vascular surgery at Danbury Hospital, Danbury Conn. He is also a clinical associate professor of surgery at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to submit a similarly useful Tips and Tricks, contact us at [email protected].

Mini-incision carotid surgery was first reported (not necessarily performed) by Ascher et al. in 2005. In light of this report and an ever-growing patient demand for minimally invasive procedures, it is surprising that this procedure has not been widely adopted by the vascular surgical community. The reasons for this are probably multifactorial and may include a concern that cranial nerve injuries are more likely to occur as well as an added difficulty in placing a shunt or sewing in a patch. These concerns are mitigated by a thorough knowledge of the usual and variant anatomy of this area and a broad experience in carotid surgery. If performed properly, mini-incision is not synonymous with mini exposure carotid surgery.

It is important to identify the carotid bifurcation with duplex ultrasound prior to making the skin incision. It is my preference to make a vertical skin incision which extends from approximately 2 cm above to below the carotid bifurcation at a slight outside to inside angle to the anterior border of the sternocleidomastoid muscle (some surgeons prefer a transverse skin incision). The platysma muscle is identified and divided for a short distance between forceps.

The edges of the platysma are grasped with DeBakey forceps while the skin is retracted as far inferiorly as possible.

The platysma is then divided to this point following which this is repeated at the superior aspect of the wound. The extended division of the platysma is what allows for an exposure equal to that of a much larger incision. Now adequate visualization of the common and internal carotid arteries is achieved by use of a small retractor applied alternately to the inferior and superior ends of the wound respectively.

Using this technique, I have easily been able to perform both standard and eversion endarterectomies (as in photo), place a shunt when necessary, and/or sew on a carotid patch.

Once completed the platysma is closed with an absorbable suture and skin is closed with an absorbable monofilament suture.

In my experience, patients have less postoperative pain than those with a larger neck incision. They are also exceptionally pleased with the small, barely visible, neck scar. Finally, I have used the mini-incision for my carotid surgeries for more than 10 years during which time no patient has suffered a permanent cranial nerve injury.

Dr. Dietzek is the chief of the vascular and endovascular surgery section and the Linda and Stephen R. Cohen chair in vascular surgery at Danbury Hospital, Danbury Conn. He is also a clinical associate professor of surgery at the University of Vermont College of Medicine in Burlington.

Editor’s Note: If you would like to submit a similarly useful Tips and Tricks, contact us at [email protected].

Welcome Our New Resident Editor

We are pleased to have Dr. Sapan S. Desai come on board as our Resident/Fellow Editor for the next year. Dr. Desai was selected from an excellent candidate pool who submitted their credentials as well as samples of their writings.

Dr. Desai is currently a vascular fellow at University of Texas at Houston/Memorial Hermann Hospital Houston, Tex. He did his surgical residency at Duke University where he still holds the rank of adjunct assistant professor of surgery.

He also has a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Medicine and an MBA in Health Care Management from Western Governors University, Salt Lake City. He is the founder and Executive Editor of the Journal of Surgical Radiology.

We look forward to his contributions and insight into issues that pertain to residents and fellows.

Dr. Russell Samson, Medical Editor, Vascular Specialist

We are pleased to have Dr. Sapan S. Desai come on board as our Resident/Fellow Editor for the next year. Dr. Desai was selected from an excellent candidate pool who submitted their credentials as well as samples of their writings.

Dr. Desai is currently a vascular fellow at University of Texas at Houston/Memorial Hermann Hospital Houston, Tex. He did his surgical residency at Duke University where he still holds the rank of adjunct assistant professor of surgery.

He also has a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Medicine and an MBA in Health Care Management from Western Governors University, Salt Lake City. He is the founder and Executive Editor of the Journal of Surgical Radiology.

We look forward to his contributions and insight into issues that pertain to residents and fellows.

Dr. Russell Samson, Medical Editor, Vascular Specialist

We are pleased to have Dr. Sapan S. Desai come on board as our Resident/Fellow Editor for the next year. Dr. Desai was selected from an excellent candidate pool who submitted their credentials as well as samples of their writings.

Dr. Desai is currently a vascular fellow at University of Texas at Houston/Memorial Hermann Hospital Houston, Tex. He did his surgical residency at Duke University where he still holds the rank of adjunct assistant professor of surgery.

He also has a PhD from the University of Illinois at Chicago, College of Medicine and an MBA in Health Care Management from Western Governors University, Salt Lake City. He is the founder and Executive Editor of the Journal of Surgical Radiology.

We look forward to his contributions and insight into issues that pertain to residents and fellows.

Dr. Russell Samson, Medical Editor, Vascular Specialist

No sex differences in carotid revascularization outcomes?

SAN FRANCISCO – There were no significant differences in endpoints between men and women after carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting, results from a large registry study showed.

"These data suggest that, contrary to previous reports, women do not have a higher risk of adverse events after carotid revascularization," Dr. Jeffrey Jim said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting. "As such, women may derive similar benefits as men from carotid revascularization."

Carotid endarterectomy is considered by many as the gold standard treatment option for patients with severe internal carotid artery stenosis, said Dr. Jim, a vascular surgeon at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. "Its benefit over best medical therapy has been proven by several landmark randomized controlled trials," he said. "While the efficacy of carotid artery stenting compared with carotid endarterectomy remains highly debated, there is clear utility in patients with select high risk criteria. However, it’s important to remember that gender plays an important role in cardiovascular disease. Epidemiologic studies clearly show that males have a higher stroke incidence as well as prevalence rate compared with women. However, when strokes do happen in women they tend to be more severe."

In terms of revascularization, he continued, available data suggested that women have a higher risk of perioperative adverse events compared with men, "suggesting that they may not benefit as much from revascularization compared with men."

He and other members of the SVS Outcomes Committee set out to evaluate the impact of gender on the outcomes after carotid revascularization (CAE and CAS), with the primary endpoint being composite risk of death, stroke, or MI at 30 days. They used data from 9,865 patients in the SVS Vascular Registry, which was developed in 2005 as a response to CMS approval of CAS. The registry was available to all clinical facilities and individual providers. "There are no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria because it aims to capture real-world results," Dr. Jim said. The registry is closed "but it remains one of the largest databases on carotid revascularization in the country."

Of the 9,865 patients 59% were men. There was no difference in age between sexes (both had a mean age of 71 years), but men were more likely to be symptomatic compared with women (42% vs. 39%, respectively).

For disease etiology in CAS, restenosis was higher in women compared with men (29% vs. 20%), while a greater proportion of men were being treated with radiation compared with women (6.2% vs. 2.6%). For CEA, more men were symptomatic compared with women (39% vs. 36%). "This was primarily driven by the fact that slightly more men than women had a stroke in the past (22% vs. 19%)," he said.

"Among patients overall, men had a slightly higher prevalence of coronary artery disease as well as MI, while women had a higher prevalence of hypertension as well as COPD," Dr. Jim said.

The researchers found no statistically significant differences in the composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI at 30 days between men and women for either CEA (4.06% vs. 4.07%, respectively) or CAS (6.80% vs. 6.69%). The findings remained similar even after stratification by symptomatology and multivariate risk adjustment.

"In all the different ways we looked at it men and women had similar outcomes," Dr. Jim said. "This data is important. It’s representative of real-world outcomes, but there are limitations. It was an observational study done in a retrospective manner, and there is the potential for reporting bias. The most important limitation is that there is no comparison group of patients treated with best medical therapy. That’s an investigation that needs to be done going forward."

Dr. Jim said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN FRANCISCO – There were no significant differences in endpoints between men and women after carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting, results from a large registry study showed.

"These data suggest that, contrary to previous reports, women do not have a higher risk of adverse events after carotid revascularization," Dr. Jeffrey Jim said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting. "As such, women may derive similar benefits as men from carotid revascularization."

Carotid endarterectomy is considered by many as the gold standard treatment option for patients with severe internal carotid artery stenosis, said Dr. Jim, a vascular surgeon at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. "Its benefit over best medical therapy has been proven by several landmark randomized controlled trials," he said. "While the efficacy of carotid artery stenting compared with carotid endarterectomy remains highly debated, there is clear utility in patients with select high risk criteria. However, it’s important to remember that gender plays an important role in cardiovascular disease. Epidemiologic studies clearly show that males have a higher stroke incidence as well as prevalence rate compared with women. However, when strokes do happen in women they tend to be more severe."

In terms of revascularization, he continued, available data suggested that women have a higher risk of perioperative adverse events compared with men, "suggesting that they may not benefit as much from revascularization compared with men."

He and other members of the SVS Outcomes Committee set out to evaluate the impact of gender on the outcomes after carotid revascularization (CAE and CAS), with the primary endpoint being composite risk of death, stroke, or MI at 30 days. They used data from 9,865 patients in the SVS Vascular Registry, which was developed in 2005 as a response to CMS approval of CAS. The registry was available to all clinical facilities and individual providers. "There are no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria because it aims to capture real-world results," Dr. Jim said. The registry is closed "but it remains one of the largest databases on carotid revascularization in the country."

Of the 9,865 patients 59% were men. There was no difference in age between sexes (both had a mean age of 71 years), but men were more likely to be symptomatic compared with women (42% vs. 39%, respectively).

For disease etiology in CAS, restenosis was higher in women compared with men (29% vs. 20%), while a greater proportion of men were being treated with radiation compared with women (6.2% vs. 2.6%). For CEA, more men were symptomatic compared with women (39% vs. 36%). "This was primarily driven by the fact that slightly more men than women had a stroke in the past (22% vs. 19%)," he said.

"Among patients overall, men had a slightly higher prevalence of coronary artery disease as well as MI, while women had a higher prevalence of hypertension as well as COPD," Dr. Jim said.

The researchers found no statistically significant differences in the composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI at 30 days between men and women for either CEA (4.06% vs. 4.07%, respectively) or CAS (6.80% vs. 6.69%). The findings remained similar even after stratification by symptomatology and multivariate risk adjustment.

"In all the different ways we looked at it men and women had similar outcomes," Dr. Jim said. "This data is important. It’s representative of real-world outcomes, but there are limitations. It was an observational study done in a retrospective manner, and there is the potential for reporting bias. The most important limitation is that there is no comparison group of patients treated with best medical therapy. That’s an investigation that needs to be done going forward."

Dr. Jim said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

SAN FRANCISCO – There were no significant differences in endpoints between men and women after carotid endarterectomy or carotid artery stenting, results from a large registry study showed.

"These data suggest that, contrary to previous reports, women do not have a higher risk of adverse events after carotid revascularization," Dr. Jeffrey Jim said at the Society for Vascular Surgery Annual Meeting. "As such, women may derive similar benefits as men from carotid revascularization."

Carotid endarterectomy is considered by many as the gold standard treatment option for patients with severe internal carotid artery stenosis, said Dr. Jim, a vascular surgeon at Washington University School of Medicine, St. Louis. "Its benefit over best medical therapy has been proven by several landmark randomized controlled trials," he said. "While the efficacy of carotid artery stenting compared with carotid endarterectomy remains highly debated, there is clear utility in patients with select high risk criteria. However, it’s important to remember that gender plays an important role in cardiovascular disease. Epidemiologic studies clearly show that males have a higher stroke incidence as well as prevalence rate compared with women. However, when strokes do happen in women they tend to be more severe."

In terms of revascularization, he continued, available data suggested that women have a higher risk of perioperative adverse events compared with men, "suggesting that they may not benefit as much from revascularization compared with men."

He and other members of the SVS Outcomes Committee set out to evaluate the impact of gender on the outcomes after carotid revascularization (CAE and CAS), with the primary endpoint being composite risk of death, stroke, or MI at 30 days. They used data from 9,865 patients in the SVS Vascular Registry, which was developed in 2005 as a response to CMS approval of CAS. The registry was available to all clinical facilities and individual providers. "There are no specific inclusion or exclusion criteria because it aims to capture real-world results," Dr. Jim said. The registry is closed "but it remains one of the largest databases on carotid revascularization in the country."

Of the 9,865 patients 59% were men. There was no difference in age between sexes (both had a mean age of 71 years), but men were more likely to be symptomatic compared with women (42% vs. 39%, respectively).

For disease etiology in CAS, restenosis was higher in women compared with men (29% vs. 20%), while a greater proportion of men were being treated with radiation compared with women (6.2% vs. 2.6%). For CEA, more men were symptomatic compared with women (39% vs. 36%). "This was primarily driven by the fact that slightly more men than women had a stroke in the past (22% vs. 19%)," he said.

"Among patients overall, men had a slightly higher prevalence of coronary artery disease as well as MI, while women had a higher prevalence of hypertension as well as COPD," Dr. Jim said.

The researchers found no statistically significant differences in the composite endpoint of death, stroke, and MI at 30 days between men and women for either CEA (4.06% vs. 4.07%, respectively) or CAS (6.80% vs. 6.69%). The findings remained similar even after stratification by symptomatology and multivariate risk adjustment.

"In all the different ways we looked at it men and women had similar outcomes," Dr. Jim said. "This data is important. It’s representative of real-world outcomes, but there are limitations. It was an observational study done in a retrospective manner, and there is the potential for reporting bias. The most important limitation is that there is no comparison group of patients treated with best medical therapy. That’s an investigation that needs to be done going forward."

Dr. Jim said that he had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

From the Vascular Community

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

From the Vascular Community

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

In November, Dr. George Andros was honored with the MedStar Georgetown 2013 Distinguished Achievement Award in Diabetic Limb Salvage at this year’s Diabetic Limb Salvage Conference in Washington, D.C. Dr. Andros is pictured with his award between DLS Conference co-chairs Dr. Christopher E. Attinger (left) and Dr. John S. Steinberg (right).

Dr. Andros is a founding partner of Los Angeles Vascular Specialists and is founder and medical director of the Amputation Prevention Center at Valley Presbyterian Hospital in Van Nuys, Calif.

For the last 14 years, Dr. Andros has been co-chair of the Diabetic Foot Global Conference (DFCon), held in Los Angeles. He is also the emeritus medical editor of Vascular Specialist .

No Benefit to Addition of Pentoxifylline to Steroids for Treatment of Severe Alcoholic Hepatitis

Clinical question

Does the combination of prednisolone and pentoxifylline improve survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Bottom line

Although pentoxifylline and prednisolone have both been demonstrated to be effective individual treatments for alcoholic hepatitis, the combination of both did not improve survival more than prednisolone alone. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Mathurin P, Louvet A, Duhamel A, et al. Prednisolone with vs without pentoxifylline and survival of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310(10):1033-1041.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Current guidelines recommend the use of either prednisolone or pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. The benefit of the combination of these 2 medications in this setting is unclear. These investigators enrolled patients who were current heavy alcohol users and who had biopsy-proven alcoholic hepatitis with a Maddrey score of 32 or more. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive prednisolone 40 mg daily plus pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily (n = 133) or prednisolone 40 mg daily plus placebo (n = 137). Treatment lasted for 28 days and follow-up was 100% at 6 months. The patients had a mean age of 51 years and an average Maddrey score in the 50s (indicating severe disease). No significant difference was detected in 6-month survival between the 2 groups in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses. Overall, there were 82 deaths in the cohort at 6 months -- 40 in the pentoxifylline-prednisolone group and 42 in the placebo-prednisolone group. The risk of hepatorenal syndrome was decreased at 1 month in the combination therapy group as compared with the placebo group (3.1% vs 11.7%; P = .007), but this difference did not remain significant at 6 months. It is important to note, however, that this study was not powered to detect a difference in the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does the combination of prednisolone and pentoxifylline improve survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Bottom line

Although pentoxifylline and prednisolone have both been demonstrated to be effective individual treatments for alcoholic hepatitis, the combination of both did not improve survival more than prednisolone alone. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Mathurin P, Louvet A, Duhamel A, et al. Prednisolone with vs without pentoxifylline and survival of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310(10):1033-1041.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Current guidelines recommend the use of either prednisolone or pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. The benefit of the combination of these 2 medications in this setting is unclear. These investigators enrolled patients who were current heavy alcohol users and who had biopsy-proven alcoholic hepatitis with a Maddrey score of 32 or more. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive prednisolone 40 mg daily plus pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily (n = 133) or prednisolone 40 mg daily plus placebo (n = 137). Treatment lasted for 28 days and follow-up was 100% at 6 months. The patients had a mean age of 51 years and an average Maddrey score in the 50s (indicating severe disease). No significant difference was detected in 6-month survival between the 2 groups in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses. Overall, there were 82 deaths in the cohort at 6 months -- 40 in the pentoxifylline-prednisolone group and 42 in the placebo-prednisolone group. The risk of hepatorenal syndrome was decreased at 1 month in the combination therapy group as compared with the placebo group (3.1% vs 11.7%; P = .007), but this difference did not remain significant at 6 months. It is important to note, however, that this study was not powered to detect a difference in the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does the combination of prednisolone and pentoxifylline improve survival in patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis?

Bottom line

Although pentoxifylline and prednisolone have both been demonstrated to be effective individual treatments for alcoholic hepatitis, the combination of both did not improve survival more than prednisolone alone. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Mathurin P, Louvet A, Duhamel A, et al. Prednisolone with vs without pentoxifylline and survival of patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis: A randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2013;310(10):1033-1041.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (double-blinded)

Funding source

Government

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

Current guidelines recommend the use of either prednisolone or pentoxifylline for the treatment of severe alcoholic hepatitis. The benefit of the combination of these 2 medications in this setting is unclear. These investigators enrolled patients who were current heavy alcohol users and who had biopsy-proven alcoholic hepatitis with a Maddrey score of 32 or more. Patients were randomized, using concealed allocation, to receive prednisolone 40 mg daily plus pentoxifylline 400 mg 3 times daily (n = 133) or prednisolone 40 mg daily plus placebo (n = 137). Treatment lasted for 28 days and follow-up was 100% at 6 months. The patients had a mean age of 51 years and an average Maddrey score in the 50s (indicating severe disease). No significant difference was detected in 6-month survival between the 2 groups in either the intention-to-treat or per-protocol analyses. Overall, there were 82 deaths in the cohort at 6 months -- 40 in the pentoxifylline-prednisolone group and 42 in the placebo-prednisolone group. The risk of hepatorenal syndrome was decreased at 1 month in the combination therapy group as compared with the placebo group (3.1% vs 11.7%; P = .007), but this difference did not remain significant at 6 months. It is important to note, however, that this study was not powered to detect a difference in the incidence of hepatorenal syndrome.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Preventive PCI During Treatment for Acute STEMI Reduces Future Cardiovascular Events (PRAMI)

Clinical question

Does preventive percutaneous coronary intervention of noninfarct but stenosed arteries improve outcomes in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction?

Bottom line

Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of noninfarct, stenosed arteries duing treatment for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is effective in decreasing long-term cardiovascular events. You would need to treat 7 patients with preventive PCI to avoid one such event. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al, for the PRAMI Investigators. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2013;369(12):1115-1123.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source

Foundation

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

This study enrolled 465 patients with acute STEMI who received successful PCI to the infarct artery and were noted to have stenosis greater than 50% in other noninfarct coronary arteries during angiography. Patients with history of, or indications for, coronary artery bypass grafting and those in cardiogenic shock were excluded. Using concealed allocation, the investigators randomized patients to receive no further PCI or immediate preventive PCI to noninfarct arteries. The 2 groups had similar comorbidities and a mean age of 62 years. The use of drug-eluting stents and medical therapy after discharge were also similar between groups. The primary outcome was the composite of death from cardiac causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or refractory angina. Mean follow-up was 2 years and analysis was by intention to treat. The trial was stopped early because of highly significant results favoring preventive PCI. Overall, there was a 9% event rate in the preventive PCI group as compared with 23% in the other group (hazard ratio = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.21-0.58; P < .001). The individual components of the primary outcome showed similar results, although the reduction in cardiac death was not statistically significant (P = .07). As expected, the procedure time and contrast volume used were higher in the preventive PCI group, but the complication rates, including contrast-induced nephropathy, did not differ between groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does preventive percutaneous coronary intervention of noninfarct but stenosed arteries improve outcomes in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction?

Bottom line

Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of noninfarct, stenosed arteries duing treatment for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is effective in decreasing long-term cardiovascular events. You would need to treat 7 patients with preventive PCI to avoid one such event. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al, for the PRAMI Investigators. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2013;369(12):1115-1123.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source

Foundation

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

This study enrolled 465 patients with acute STEMI who received successful PCI to the infarct artery and were noted to have stenosis greater than 50% in other noninfarct coronary arteries during angiography. Patients with history of, or indications for, coronary artery bypass grafting and those in cardiogenic shock were excluded. Using concealed allocation, the investigators randomized patients to receive no further PCI or immediate preventive PCI to noninfarct arteries. The 2 groups had similar comorbidities and a mean age of 62 years. The use of drug-eluting stents and medical therapy after discharge were also similar between groups. The primary outcome was the composite of death from cardiac causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or refractory angina. Mean follow-up was 2 years and analysis was by intention to treat. The trial was stopped early because of highly significant results favoring preventive PCI. Overall, there was a 9% event rate in the preventive PCI group as compared with 23% in the other group (hazard ratio = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.21-0.58; P < .001). The individual components of the primary outcome showed similar results, although the reduction in cardiac death was not statistically significant (P = .07). As expected, the procedure time and contrast volume used were higher in the preventive PCI group, but the complication rates, including contrast-induced nephropathy, did not differ between groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

Clinical question

Does preventive percutaneous coronary intervention of noninfarct but stenosed arteries improve outcomes in patients with acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction?

Bottom line

Preventive percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of noninfarct, stenosed arteries duing treatment for acute ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) is effective in decreasing long-term cardiovascular events. You would need to treat 7 patients with preventive PCI to avoid one such event. (LOE = 1b)

Reference

Wald DS, Morris JK, Wald NJ, et al, for the PRAMI Investigators. Randomized trial of preventive angioplasty in myocardial infarction. N Engl J Med 2013;369(12):1115-1123.

Study design

Randomized controlled trial (single-blinded)

Funding source

Foundation

Allocation

Concealed

Setting

Inpatient (any location) with outpatient follow-up

Synopsis

This study enrolled 465 patients with acute STEMI who received successful PCI to the infarct artery and were noted to have stenosis greater than 50% in other noninfarct coronary arteries during angiography. Patients with history of, or indications for, coronary artery bypass grafting and those in cardiogenic shock were excluded. Using concealed allocation, the investigators randomized patients to receive no further PCI or immediate preventive PCI to noninfarct arteries. The 2 groups had similar comorbidities and a mean age of 62 years. The use of drug-eluting stents and medical therapy after discharge were also similar between groups. The primary outcome was the composite of death from cardiac causes, nonfatal myocardial infarction, or refractory angina. Mean follow-up was 2 years and analysis was by intention to treat. The trial was stopped early because of highly significant results favoring preventive PCI. Overall, there was a 9% event rate in the preventive PCI group as compared with 23% in the other group (hazard ratio = 0.35; 95% CI, 0.21-0.58; P < .001). The individual components of the primary outcome showed similar results, although the reduction in cardiac death was not statistically significant (P = .07). As expected, the procedure time and contrast volume used were higher in the preventive PCI group, but the complication rates, including contrast-induced nephropathy, did not differ between groups.

Dr. Kulkarni is an assistant professor of hospital medicine at Northwestern University in Chicago.

A one-size-fits-all fenestrated graft for iliac aneurysms?

CHICAGO – A novel bifurcated covered stent graft limb that uses an off-the-shelf graft can treat large common iliac aneurysms, while preserving good pelvic blood flow.

The alternative endovascular approach has been performed on 15 patients since April 2011, with a success rate of 100%. Bilateral stent grafts were placed in four patients.

The all-male cohort has been able to maintain appropriate exercise tolerance and remains free from erectile dysfunction, pelvic ischemia, buttock claudication, and paralysis.

"These people do well,extremely well," Dr. Patrick Kelly said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Several iliac branch grafts are currently under investigation, including the Cook Zenith Branch iliac endovascular graft. They promise to preserve flow to the internal iliac artery and thus reduce the potential for ischemic sequelae resulting from iliac embolization. Depending on patient anatomy, however, the internal iliac may become jailed upon deployment of the main body graft, said Dr. Kelly of Sanford Health, Sioux Falls, S.D. The fenestrated systems are also limited by bridging stent technology and the relatively short bridging stent.

His alternative modified bifurcated limb divides the common iliac flow into the internal and external iliac arteries, while excluding the common iliac artery aneurysm.

"The pros are that it uses an off-the-shelf [graft], should be able to handle virtually any anatomy, can be used to treat either existing EVAR or previous open repairs, and has multiple off-ramps, so you don’t jail yourself," he said. "The cons: It requires arm access – although I’m not sure that’s a con – and it requires three stents."

Operative details

The bifurcated limb is created by sewing an 8-mm and 10-mm covered stent graft to the distal end of a standard 16 x 20 x 82-mm stent graft limb. The distal ends of both the 8-mm and 10-mm grafts are left free, allowing flexibility and easier selection of the internal iliac artery, he said.

Once the graft is resheathed using a spiral wire technique, a traditional infrarenal abdominal aneurysm repair is performed. In order to exclude the common iliac aneurysm, the graft is oriented with the 8-mm limb toward the internal iliac and with the distal end of the 8-mm limb being deployed 2-3 cm above the origin of the internal iliac artery. The internal iliac artery is selected from an arm approach, through the 8-mm limb of the bifurcated stent graft limb.

Angiograms are performed and a 3-cm covered, self-expanding bridge stent graft is deployed. The 10-mm limb is used to extend the graft into the external iliac, thus completing exclusion of the common iliac aneurysm, while preserving both the internal and external iliac arteries, Dr. Kelly said.

Thus far, occlusion of the external iliac artery has been reported in one patient, and there were no recurring endoleaks. There was a type 3 endoleak between the main body and bridging stent that was visible on diagnostic angiography, but it resolved after being reballooned and patent flow was established upon completion angiography, Dr. Kelly explained. There was also a retrograde fill that was fixed 1 year postoperatively by extending the limb to obtain a healthy seal.

The average patient age was 65.4 years (range, 46-87 years); fluoroscopy time, 46 minutes (range, 29-91 minutes); and average length of stay 3.1 days (range, 1-9 days).

This compares with an average hospital stay of 4-7 days for the tried-and-true method of open aneurysm repair, which has bleeding rates of 30% or more, colonic ischemia in 20%-30%, and paraplegia in 2%-3%, Dr. Kelly noted.

Audience reaction

Dr. Rebecca Kelso of the Cleveland Clinic, who co-moderated the session, was enthusiastic about the novel approach.

"The potential for it is quite significant, because the other main competitive device he mentioned that’s on the market still has anatomic limitations for use," she said in an interview. "So if he has something that can be used in any patient, no matter what the circumstances, that has significant implications for being available commercially for everyone."

Fellow moderator Dr. Patrick J. Geraghty of Washington University, St. Louis, remarked that while the approach uses a standardized graft, it is somewhat tailored since the length and the diameter of the grafts extending into the external and internal iliac arteries can be chosen separately. That said, the one-size-fits-all approach is particularly appealing because it could simplify treatment planning and reduce treatment delays.

"If you have a patient who is symptomatic and you have an off-the-shelf component, you could potentially treat them within the next 24 hours," he said in an interview. "The current turnaround time for the fenestrated system is about a month or so, so it would shorten treatment delays and might lead to a broader application of the technology."

A potentially shorter hospital length of stay could also reduce hospital costs, Dr. Kelso noted.

While the audience appeared equally enthusiastic about the results, some members questioned whether results on a physician-modified graft without an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) should be presented at the meeting in light of recent warnings by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that such interventions involve the use of significant-risk devices and need to be conducted under an IDE. Dr. Kelly responded that he is currently working with the FDA to obtain an IDE.

Earlier this year, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology became the first medical societies to receive an IDE to study alternative access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement using the STS/ACC TVT Registry.

Dr. Kelly and Dr. Kelso reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Geraghty disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Bard/Lutonix.

| |

Dr. John F. Eidt |

Vascular surgeons are like cobblers – we try to make the perfect pair of shoes for each customer. While all aneurysm operations are similar in principle, in reality each successful operation depends on a unique blend of surgical skill and experience applied to the individual anatomy of each patient. By combining endovascular and open surgical skills, vascular surgeons are enticed to develop ever more innovative solutions for complex problems. Dr. Kelly should be congratulated for thinking outside the box and applying his imagination and skill to the solution of this common clinical scenario. While I am intrigued by the technique, I will reserve my enthusiastic endorsement because of the relatively high cost and the fact the common iliac artery must be sufficiently large to accommodate the physician-modified bifurcated graft. Others have described the use of a "stacked" Gore Excluder device to achieve a similar result. And the Cook Iliac Branched Device is nearing approval. In the long run, the FDA needs to adopt policies that encourage rather than discourage innovation in the develop- ment of novel surgical treatments. The current onerous IDE process is excessively complex and expensive. Physician-modified endografts fill an important gap in our ability to deliver quality, customized care for every patient. And there is no evidence that innovation in vascular surgery has been harmful to patients. After all, every operation is "physician modified."

Dr. John F. Eidt is a vascular surgeon at the Greenville (South Carolina) Health System, and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

| |

Dr. John F. Eidt |

Vascular surgeons are like cobblers – we try to make the perfect pair of shoes for each customer. While all aneurysm operations are similar in principle, in reality each successful operation depends on a unique blend of surgical skill and experience applied to the individual anatomy of each patient. By combining endovascular and open surgical skills, vascular surgeons are enticed to develop ever more innovative solutions for complex problems. Dr. Kelly should be congratulated for thinking outside the box and applying his imagination and skill to the solution of this common clinical scenario. While I am intrigued by the technique, I will reserve my enthusiastic endorsement because of the relatively high cost and the fact the common iliac artery must be sufficiently large to accommodate the physician-modified bifurcated graft. Others have described the use of a "stacked" Gore Excluder device to achieve a similar result. And the Cook Iliac Branched Device is nearing approval. In the long run, the FDA needs to adopt policies that encourage rather than discourage innovation in the develop- ment of novel surgical treatments. The current onerous IDE process is excessively complex and expensive. Physician-modified endografts fill an important gap in our ability to deliver quality, customized care for every patient. And there is no evidence that innovation in vascular surgery has been harmful to patients. After all, every operation is "physician modified."

Dr. John F. Eidt is a vascular surgeon at the Greenville (South Carolina) Health System, and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

| |

Dr. John F. Eidt |

Vascular surgeons are like cobblers – we try to make the perfect pair of shoes for each customer. While all aneurysm operations are similar in principle, in reality each successful operation depends on a unique blend of surgical skill and experience applied to the individual anatomy of each patient. By combining endovascular and open surgical skills, vascular surgeons are enticed to develop ever more innovative solutions for complex problems. Dr. Kelly should be congratulated for thinking outside the box and applying his imagination and skill to the solution of this common clinical scenario. While I am intrigued by the technique, I will reserve my enthusiastic endorsement because of the relatively high cost and the fact the common iliac artery must be sufficiently large to accommodate the physician-modified bifurcated graft. Others have described the use of a "stacked" Gore Excluder device to achieve a similar result. And the Cook Iliac Branched Device is nearing approval. In the long run, the FDA needs to adopt policies that encourage rather than discourage innovation in the develop- ment of novel surgical treatments. The current onerous IDE process is excessively complex and expensive. Physician-modified endografts fill an important gap in our ability to deliver quality, customized care for every patient. And there is no evidence that innovation in vascular surgery has been harmful to patients. After all, every operation is "physician modified."

Dr. John F. Eidt is a vascular surgeon at the Greenville (South Carolina) Health System, and an associate medical editor of Vascular Specialist.

CHICAGO – A novel bifurcated covered stent graft limb that uses an off-the-shelf graft can treat large common iliac aneurysms, while preserving good pelvic blood flow.

The alternative endovascular approach has been performed on 15 patients since April 2011, with a success rate of 100%. Bilateral stent grafts were placed in four patients.

The all-male cohort has been able to maintain appropriate exercise tolerance and remains free from erectile dysfunction, pelvic ischemia, buttock claudication, and paralysis.

"These people do well,extremely well," Dr. Patrick Kelly said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Several iliac branch grafts are currently under investigation, including the Cook Zenith Branch iliac endovascular graft. They promise to preserve flow to the internal iliac artery and thus reduce the potential for ischemic sequelae resulting from iliac embolization. Depending on patient anatomy, however, the internal iliac may become jailed upon deployment of the main body graft, said Dr. Kelly of Sanford Health, Sioux Falls, S.D. The fenestrated systems are also limited by bridging stent technology and the relatively short bridging stent.

His alternative modified bifurcated limb divides the common iliac flow into the internal and external iliac arteries, while excluding the common iliac artery aneurysm.

"The pros are that it uses an off-the-shelf [graft], should be able to handle virtually any anatomy, can be used to treat either existing EVAR or previous open repairs, and has multiple off-ramps, so you don’t jail yourself," he said. "The cons: It requires arm access – although I’m not sure that’s a con – and it requires three stents."

Operative details

The bifurcated limb is created by sewing an 8-mm and 10-mm covered stent graft to the distal end of a standard 16 x 20 x 82-mm stent graft limb. The distal ends of both the 8-mm and 10-mm grafts are left free, allowing flexibility and easier selection of the internal iliac artery, he said.

Once the graft is resheathed using a spiral wire technique, a traditional infrarenal abdominal aneurysm repair is performed. In order to exclude the common iliac aneurysm, the graft is oriented with the 8-mm limb toward the internal iliac and with the distal end of the 8-mm limb being deployed 2-3 cm above the origin of the internal iliac artery. The internal iliac artery is selected from an arm approach, through the 8-mm limb of the bifurcated stent graft limb.

Angiograms are performed and a 3-cm covered, self-expanding bridge stent graft is deployed. The 10-mm limb is used to extend the graft into the external iliac, thus completing exclusion of the common iliac aneurysm, while preserving both the internal and external iliac arteries, Dr. Kelly said.

Thus far, occlusion of the external iliac artery has been reported in one patient, and there were no recurring endoleaks. There was a type 3 endoleak between the main body and bridging stent that was visible on diagnostic angiography, but it resolved after being reballooned and patent flow was established upon completion angiography, Dr. Kelly explained. There was also a retrograde fill that was fixed 1 year postoperatively by extending the limb to obtain a healthy seal.

The average patient age was 65.4 years (range, 46-87 years); fluoroscopy time, 46 minutes (range, 29-91 minutes); and average length of stay 3.1 days (range, 1-9 days).

This compares with an average hospital stay of 4-7 days for the tried-and-true method of open aneurysm repair, which has bleeding rates of 30% or more, colonic ischemia in 20%-30%, and paraplegia in 2%-3%, Dr. Kelly noted.

Audience reaction

Dr. Rebecca Kelso of the Cleveland Clinic, who co-moderated the session, was enthusiastic about the novel approach.

"The potential for it is quite significant, because the other main competitive device he mentioned that’s on the market still has anatomic limitations for use," she said in an interview. "So if he has something that can be used in any patient, no matter what the circumstances, that has significant implications for being available commercially for everyone."

Fellow moderator Dr. Patrick J. Geraghty of Washington University, St. Louis, remarked that while the approach uses a standardized graft, it is somewhat tailored since the length and the diameter of the grafts extending into the external and internal iliac arteries can be chosen separately. That said, the one-size-fits-all approach is particularly appealing because it could simplify treatment planning and reduce treatment delays.

"If you have a patient who is symptomatic and you have an off-the-shelf component, you could potentially treat them within the next 24 hours," he said in an interview. "The current turnaround time for the fenestrated system is about a month or so, so it would shorten treatment delays and might lead to a broader application of the technology."

A potentially shorter hospital length of stay could also reduce hospital costs, Dr. Kelso noted.

While the audience appeared equally enthusiastic about the results, some members questioned whether results on a physician-modified graft without an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) should be presented at the meeting in light of recent warnings by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that such interventions involve the use of significant-risk devices and need to be conducted under an IDE. Dr. Kelly responded that he is currently working with the FDA to obtain an IDE.

Earlier this year, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology became the first medical societies to receive an IDE to study alternative access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement using the STS/ACC TVT Registry.

Dr. Kelly and Dr. Kelso reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Geraghty disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Bard/Lutonix.

CHICAGO – A novel bifurcated covered stent graft limb that uses an off-the-shelf graft can treat large common iliac aneurysms, while preserving good pelvic blood flow.

The alternative endovascular approach has been performed on 15 patients since April 2011, with a success rate of 100%. Bilateral stent grafts were placed in four patients.

The all-male cohort has been able to maintain appropriate exercise tolerance and remains free from erectile dysfunction, pelvic ischemia, buttock claudication, and paralysis.

"These people do well,extremely well," Dr. Patrick Kelly said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

Several iliac branch grafts are currently under investigation, including the Cook Zenith Branch iliac endovascular graft. They promise to preserve flow to the internal iliac artery and thus reduce the potential for ischemic sequelae resulting from iliac embolization. Depending on patient anatomy, however, the internal iliac may become jailed upon deployment of the main body graft, said Dr. Kelly of Sanford Health, Sioux Falls, S.D. The fenestrated systems are also limited by bridging stent technology and the relatively short bridging stent.

His alternative modified bifurcated limb divides the common iliac flow into the internal and external iliac arteries, while excluding the common iliac artery aneurysm.

"The pros are that it uses an off-the-shelf [graft], should be able to handle virtually any anatomy, can be used to treat either existing EVAR or previous open repairs, and has multiple off-ramps, so you don’t jail yourself," he said. "The cons: It requires arm access – although I’m not sure that’s a con – and it requires three stents."

Operative details

The bifurcated limb is created by sewing an 8-mm and 10-mm covered stent graft to the distal end of a standard 16 x 20 x 82-mm stent graft limb. The distal ends of both the 8-mm and 10-mm grafts are left free, allowing flexibility and easier selection of the internal iliac artery, he said.

Once the graft is resheathed using a spiral wire technique, a traditional infrarenal abdominal aneurysm repair is performed. In order to exclude the common iliac aneurysm, the graft is oriented with the 8-mm limb toward the internal iliac and with the distal end of the 8-mm limb being deployed 2-3 cm above the origin of the internal iliac artery. The internal iliac artery is selected from an arm approach, through the 8-mm limb of the bifurcated stent graft limb.

Angiograms are performed and a 3-cm covered, self-expanding bridge stent graft is deployed. The 10-mm limb is used to extend the graft into the external iliac, thus completing exclusion of the common iliac aneurysm, while preserving both the internal and external iliac arteries, Dr. Kelly said.

Thus far, occlusion of the external iliac artery has been reported in one patient, and there were no recurring endoleaks. There was a type 3 endoleak between the main body and bridging stent that was visible on diagnostic angiography, but it resolved after being reballooned and patent flow was established upon completion angiography, Dr. Kelly explained. There was also a retrograde fill that was fixed 1 year postoperatively by extending the limb to obtain a healthy seal.

The average patient age was 65.4 years (range, 46-87 years); fluoroscopy time, 46 minutes (range, 29-91 minutes); and average length of stay 3.1 days (range, 1-9 days).

This compares with an average hospital stay of 4-7 days for the tried-and-true method of open aneurysm repair, which has bleeding rates of 30% or more, colonic ischemia in 20%-30%, and paraplegia in 2%-3%, Dr. Kelly noted.

Audience reaction

Dr. Rebecca Kelso of the Cleveland Clinic, who co-moderated the session, was enthusiastic about the novel approach.

"The potential for it is quite significant, because the other main competitive device he mentioned that’s on the market still has anatomic limitations for use," she said in an interview. "So if he has something that can be used in any patient, no matter what the circumstances, that has significant implications for being available commercially for everyone."

Fellow moderator Dr. Patrick J. Geraghty of Washington University, St. Louis, remarked that while the approach uses a standardized graft, it is somewhat tailored since the length and the diameter of the grafts extending into the external and internal iliac arteries can be chosen separately. That said, the one-size-fits-all approach is particularly appealing because it could simplify treatment planning and reduce treatment delays.

"If you have a patient who is symptomatic and you have an off-the-shelf component, you could potentially treat them within the next 24 hours," he said in an interview. "The current turnaround time for the fenestrated system is about a month or so, so it would shorten treatment delays and might lead to a broader application of the technology."

A potentially shorter hospital length of stay could also reduce hospital costs, Dr. Kelso noted.

While the audience appeared equally enthusiastic about the results, some members questioned whether results on a physician-modified graft without an Investigational Device Exemption (IDE) should be presented at the meeting in light of recent warnings by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration that such interventions involve the use of significant-risk devices and need to be conducted under an IDE. Dr. Kelly responded that he is currently working with the FDA to obtain an IDE.

Earlier this year, the Society of Thoracic Surgeons and the American College of Cardiology became the first medical societies to receive an IDE to study alternative access for transcatheter aortic valve replacement using the STS/ACC TVT Registry.

Dr. Kelly and Dr. Kelso reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Geraghty disclosed relationships with Cook Medical and Bard/Lutonix.

Local anesthesia aids hemodynamic stability for CEA

CHICAGO – Patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy with cervical block anesthesia had fewer hemodynamic fluctuations and required less vasoactive medications than those under general anesthesia in a retrospective evaluation.

"Under cervical block anesthesia, carotid endarterectomy can be performed with a better hemodynamic profile," Dr. Marika Y. Gassner, a resident with Henry Ford Macomb Hospital, Clinton Township, Mich., said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The practice switched in 2003 from using general anesthesia for the majority of carotid endarterectomy to performing more than 90% of cases under local cervical block anesthesia (CBA). Exceptions include patients who are extremely nervous, unable to communicate in English, or who have plaque extending above C2.

The investigators organized the retrospective cohort study after initial observations suggested patients under CBA had less intraoperative hypotension or fluctuations in mean arterial pressure below 65 mm Hg. Vasoactive therapy demands were also lower. For example, anesthesia records showed that several doses of beta-blockers and ephedrine were required for a patient under general anesthesia, while a patient under CBA had only a single dose of midazolam (Versed) early in the procedure, she said.

Other advantages of CBA include continuous feedback on neurologic status/cerebral perfusion, endotracheal intubation not required, shorter operative times, and reduced use of shunts, Dr. Gassner said.

The analysis included 651 patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy by a single surgeon at two suburban teaching hospitals, with 397 under general anesthesia (GA) and 254 under CBA.

The CBA and GA groups were similar in age (71.26 vs. 70.97 years) and incidence of coronary artery disease (57% vs. 56%), hypertension (77% vs. 75%), and renal failure (3.5% vs. 4.0%). The GA group, however, had significantly more females (39% vs. 46.6%), and a higher incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (16% vs. 23%), nicotine abuse, (50% vs. 63%), and symptomatic patients (41.3% vs. 54%).

The incidence of intraoperative hypotension (systolic BP less than 100 mm HG) was 0.52% with CBA and 17.84% with GA (P less than .001), Dr. Gassner said.

Mean arterial pressure changes of 20% or more per patient occurred in 20% and 41%, respectively (P less than .001).

Vasopressors were required during surgery in 51.13% of the GA group and 36.22% of the CBA group (P = .0002), and antihypertensive medications in 64% and 73.6% (P = .0085). Drugs from both categories were required by significantly fewer CBA patients (22.5% vs. 33.75%; P = .045), she said.

There were no deaths in either group. Postoperative complications were higher in the GA than the CBA group including myocardial infarction (4 vs. 0 events), stroke (6 vs. 0 events), hematoma (7 vs. 2 events), and return to the OR (7 vs. 0 events). The difference did not reach statistical significance because of the sample size, Dr. Gassner said.

Earlier in the presentation, she observed that there was no difference in the primary composite endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death at 30 days in the randomized GALA (general anaesthesia vs. local anaesthesia for carotid surgery) trial conducted at 95 centers in 24 countries (Lancet 2008;372:2132-42).

"If they couldn’t find it [a survival advantage] in GALA with 3,500 patients, we couldn’t find it here," Dr. Gassner said, adding that a randomized trial powered to look at late mortality is needed.

The group has no current plans to conduct such a study or a cost analysis, although a subsequent analysis of the GALA data revealed a cost savings of about $283 favoring carotid endarterectomy using local anesthesia (Br. J. Surg. 2010;97:1218-25).

Dr. Gassner and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy with cervical block anesthesia had fewer hemodynamic fluctuations and required less vasoactive medications than those under general anesthesia in a retrospective evaluation.

"Under cervical block anesthesia, carotid endarterectomy can be performed with a better hemodynamic profile," Dr. Marika Y. Gassner, a resident with Henry Ford Macomb Hospital, Clinton Township, Mich., said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The practice switched in 2003 from using general anesthesia for the majority of carotid endarterectomy to performing more than 90% of cases under local cervical block anesthesia (CBA). Exceptions include patients who are extremely nervous, unable to communicate in English, or who have plaque extending above C2.

The investigators organized the retrospective cohort study after initial observations suggested patients under CBA had less intraoperative hypotension or fluctuations in mean arterial pressure below 65 mm Hg. Vasoactive therapy demands were also lower. For example, anesthesia records showed that several doses of beta-blockers and ephedrine were required for a patient under general anesthesia, while a patient under CBA had only a single dose of midazolam (Versed) early in the procedure, she said.

Other advantages of CBA include continuous feedback on neurologic status/cerebral perfusion, endotracheal intubation not required, shorter operative times, and reduced use of shunts, Dr. Gassner said.

The analysis included 651 patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy by a single surgeon at two suburban teaching hospitals, with 397 under general anesthesia (GA) and 254 under CBA.

The CBA and GA groups were similar in age (71.26 vs. 70.97 years) and incidence of coronary artery disease (57% vs. 56%), hypertension (77% vs. 75%), and renal failure (3.5% vs. 4.0%). The GA group, however, had significantly more females (39% vs. 46.6%), and a higher incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (16% vs. 23%), nicotine abuse, (50% vs. 63%), and symptomatic patients (41.3% vs. 54%).

The incidence of intraoperative hypotension (systolic BP less than 100 mm HG) was 0.52% with CBA and 17.84% with GA (P less than .001), Dr. Gassner said.

Mean arterial pressure changes of 20% or more per patient occurred in 20% and 41%, respectively (P less than .001).

Vasopressors were required during surgery in 51.13% of the GA group and 36.22% of the CBA group (P = .0002), and antihypertensive medications in 64% and 73.6% (P = .0085). Drugs from both categories were required by significantly fewer CBA patients (22.5% vs. 33.75%; P = .045), she said.

There were no deaths in either group. Postoperative complications were higher in the GA than the CBA group including myocardial infarction (4 vs. 0 events), stroke (6 vs. 0 events), hematoma (7 vs. 2 events), and return to the OR (7 vs. 0 events). The difference did not reach statistical significance because of the sample size, Dr. Gassner said.

Earlier in the presentation, she observed that there was no difference in the primary composite endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death at 30 days in the randomized GALA (general anaesthesia vs. local anaesthesia for carotid surgery) trial conducted at 95 centers in 24 countries (Lancet 2008;372:2132-42).

"If they couldn’t find it [a survival advantage] in GALA with 3,500 patients, we couldn’t find it here," Dr. Gassner said, adding that a randomized trial powered to look at late mortality is needed.

The group has no current plans to conduct such a study or a cost analysis, although a subsequent analysis of the GALA data revealed a cost savings of about $283 favoring carotid endarterectomy using local anesthesia (Br. J. Surg. 2010;97:1218-25).

Dr. Gassner and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

CHICAGO – Patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy with cervical block anesthesia had fewer hemodynamic fluctuations and required less vasoactive medications than those under general anesthesia in a retrospective evaluation.

"Under cervical block anesthesia, carotid endarterectomy can be performed with a better hemodynamic profile," Dr. Marika Y. Gassner, a resident with Henry Ford Macomb Hospital, Clinton Township, Mich., said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The practice switched in 2003 from using general anesthesia for the majority of carotid endarterectomy to performing more than 90% of cases under local cervical block anesthesia (CBA). Exceptions include patients who are extremely nervous, unable to communicate in English, or who have plaque extending above C2.

The investigators organized the retrospective cohort study after initial observations suggested patients under CBA had less intraoperative hypotension or fluctuations in mean arterial pressure below 65 mm Hg. Vasoactive therapy demands were also lower. For example, anesthesia records showed that several doses of beta-blockers and ephedrine were required for a patient under general anesthesia, while a patient under CBA had only a single dose of midazolam (Versed) early in the procedure, she said.

Other advantages of CBA include continuous feedback on neurologic status/cerebral perfusion, endotracheal intubation not required, shorter operative times, and reduced use of shunts, Dr. Gassner said.

The analysis included 651 patients who underwent carotid endarterectomy by a single surgeon at two suburban teaching hospitals, with 397 under general anesthesia (GA) and 254 under CBA.

The CBA and GA groups were similar in age (71.26 vs. 70.97 years) and incidence of coronary artery disease (57% vs. 56%), hypertension (77% vs. 75%), and renal failure (3.5% vs. 4.0%). The GA group, however, had significantly more females (39% vs. 46.6%), and a higher incidence of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (16% vs. 23%), nicotine abuse, (50% vs. 63%), and symptomatic patients (41.3% vs. 54%).

The incidence of intraoperative hypotension (systolic BP less than 100 mm HG) was 0.52% with CBA and 17.84% with GA (P less than .001), Dr. Gassner said.

Mean arterial pressure changes of 20% or more per patient occurred in 20% and 41%, respectively (P less than .001).

Vasopressors were required during surgery in 51.13% of the GA group and 36.22% of the CBA group (P = .0002), and antihypertensive medications in 64% and 73.6% (P = .0085). Drugs from both categories were required by significantly fewer CBA patients (22.5% vs. 33.75%; P = .045), she said.

There were no deaths in either group. Postoperative complications were higher in the GA than the CBA group including myocardial infarction (4 vs. 0 events), stroke (6 vs. 0 events), hematoma (7 vs. 2 events), and return to the OR (7 vs. 0 events). The difference did not reach statistical significance because of the sample size, Dr. Gassner said.

Earlier in the presentation, she observed that there was no difference in the primary composite endpoint of stroke, myocardial infarction, or death at 30 days in the randomized GALA (general anaesthesia vs. local anaesthesia for carotid surgery) trial conducted at 95 centers in 24 countries (Lancet 2008;372:2132-42).

"If they couldn’t find it [a survival advantage] in GALA with 3,500 patients, we couldn’t find it here," Dr. Gassner said, adding that a randomized trial powered to look at late mortality is needed.

The group has no current plans to conduct such a study or a cost analysis, although a subsequent analysis of the GALA data revealed a cost savings of about $283 favoring carotid endarterectomy using local anesthesia (Br. J. Surg. 2010;97:1218-25).

Dr. Gassner and her coauthors reported having no financial disclosures.

IUDs, OCs, STDs... OMG!!!

Let’s face it, most of us when we entered into pediatrics envisioned bouncing babies, adorable toddlers, and snotty-nosed children drawing us pictures that adorned the walls of our office. Never did we imagine sitting in a room across from a stone-faced teenage girl to talk about birth control.

But, reality quickly sets in, and staying up to date with the latest recommendation on birth control is imperative or you need to make the proper referral. Knowing the laws of your state about birth control, which govern your ability to administer contraception without parental consent, is vital. The Guttmacher website gives you a concise list for each state. Parental involvement is always encouraged, but may be the obstacle that prevents the patient from having the discussion.

Abstinence is the only foolproof way to avoid pregnancy, yet many of us forget to discuss it during our conversation. With statistics like 40% of teens report to having engaged in some level of sexual activity by age 15, it is not far-fetched to believe that there are teens who just assume all of their peers are having sex (Hatcher, R.A., et al. Contraceptive Technology, 20th revised ed. New York: Ardent Media, 2011). It is important that teens know that the majority of teens are not having sex, and saying "No" is an option. But teens will need support and help in developing the skills to incorporate abstinence into their relationships.

Discussing the health risk of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and the possibility of infertility has a strong impact. Being clear on the risks of contracting human papillomavirus with the subsequent risk of cervical cancer associated with having multiple sexual partners, as well as the risk of contracting an incurable disease such as HIV, can be very persuasive.

Discussing condoms, how they protect against sexually transmitted diseases, and the value of dual protection is also important.

With pregnancy rates lower than 1% with perfect and typical use, long-acting reversible contraceptive (LARC) methods "are the best reversible methods for preventing unintended pregnancy, rapid repeat pregnancy, and abortion in young women," according to the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists committee opinion No. 539, written by the Committee on Adolescent Health Care Long-Acting Reversible Contraception Working Group (Obstet. Gynecol. 2012;120:983-8). Complications of these methods – intrauterine devices (IUDs) and the contraceptive implant – are rare and are similar in adolescents and older women, yet LARCs are underused in the younger age group.