User login

Top vascular readmission procedures

CHICAGO - Lower-extremity revascularization or amputation was among the strongest predictors of 30-day vascular surgery readmission in what is being described as the largest single-center review in this setting to date. Lower-extremity revascularization and amputations made up 63% of unplanned readmissions, though rates for endovascular lower-extremity revascularization were almost half that of open revascularization (8.2% vs. 15%).

Notably, below-knee amputations fared the worst, with a 30-day unplanned readmission rate of 24%, compared with 13.3% for above-knee amputations and 16.4% for foot amputation.

"Amputations and open lower-extremity revascularization had the highest rates of readmission in this analysis and therefore we need to focus our efforts and find additional postoperative [management] strategies for these two subgroups," Dr. Travis L. Engelbert said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The analysis involved 2,505 patients who underwent vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics in Madison from 2009 to mid-2013. The overall readmission rate was 9.7% (n = 244). Of these, 147 patients (60.2%) were readmitted to the vascular surgery service.

The most common readmitting diagnosis was wound complication or infection in 37%, said Dr. Engelbert, a vascular surgeon at the university.

Patients whose index admission was urgent rather than elective had significantly higher readmission rates (14.6% vs. 6.9%; P less than .001), as did those living remotely rather than inside Dane County, where the university is located (12% vs. 8.8%; P = .02).

Not surprisingly, higher illness severity, as calculated using the 3M APR DRG software, was significantly associated with readmission (15.6% high vs. 4.3% low severity; P less than .001).

Patients who were readmitted had a longer initial length of stay (8.5 days vs. 6.1 days; P less than .01), and were more likely to have an ICU admission (18.3% vs. 9.5% without ICU stay; P less than .05), he reported.

Based on insurance status, patients covered by Medicaid (16.8%) and Medicare (10%) were most likely to have an unplanned readmission, followed by fee-for-service patients (9.5%), self-pay (8%), and HMO (5.5%) patients (P = .02).

Dr. Engelbert observed that vascular surgery outcomes have come under scrutiny and that there has been some discussion of cutbacks in Medicare reimbursement given its high rates of readmission.

"This is already starting to happen for certain medical patient populations and if this were to happen, it would significantly affect a vascular service?s practice because a majority of our patients are covered by Medicare and have a higher readmission rate," he said.

The analysis suggests that vascular surgeons may also want to pay closer attention to discharge destination for their patients. Readmission rates were about three times higher for patients discharged to a rehabilitation facility or skilled nursing facility than for those discharged home (19.2% and 16.2% vs. 6.2%; P less than .01).

"The discharge destination matters," Dr. Engelbert said. "... We need to have improved coordination between hospitals and postdischarge destinations. And, we also might need to look at how these patients are cared for and if they are discharged to the appropriate level of care when they?re discharged to these skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities."

The effects of discharge destination (odds ratio, 1.54 skilled nursing facility), index length of stay (OR, 1.03), insurance (OR, 0.43 HMO), and lower-extremity revascularization or amputation (OR, 2.35) persisted in multivariable logistic regression analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, proximity to hospital, clinic follow-up time, urgent vs. elective admission, insurance type, procedure type, length of stay, and discharge destination.

Dr. Engelbert had no conflicts.

CHICAGO - Lower-extremity revascularization or amputation was among the strongest predictors of 30-day vascular surgery readmission in what is being described as the largest single-center review in this setting to date. Lower-extremity revascularization and amputations made up 63% of unplanned readmissions, though rates for endovascular lower-extremity revascularization were almost half that of open revascularization (8.2% vs. 15%).

Notably, below-knee amputations fared the worst, with a 30-day unplanned readmission rate of 24%, compared with 13.3% for above-knee amputations and 16.4% for foot amputation.

"Amputations and open lower-extremity revascularization had the highest rates of readmission in this analysis and therefore we need to focus our efforts and find additional postoperative [management] strategies for these two subgroups," Dr. Travis L. Engelbert said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The analysis involved 2,505 patients who underwent vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics in Madison from 2009 to mid-2013. The overall readmission rate was 9.7% (n = 244). Of these, 147 patients (60.2%) were readmitted to the vascular surgery service.

The most common readmitting diagnosis was wound complication or infection in 37%, said Dr. Engelbert, a vascular surgeon at the university.

Patients whose index admission was urgent rather than elective had significantly higher readmission rates (14.6% vs. 6.9%; P less than .001), as did those living remotely rather than inside Dane County, where the university is located (12% vs. 8.8%; P = .02).

Not surprisingly, higher illness severity, as calculated using the 3M APR DRG software, was significantly associated with readmission (15.6% high vs. 4.3% low severity; P less than .001).

Patients who were readmitted had a longer initial length of stay (8.5 days vs. 6.1 days; P less than .01), and were more likely to have an ICU admission (18.3% vs. 9.5% without ICU stay; P less than .05), he reported.

Based on insurance status, patients covered by Medicaid (16.8%) and Medicare (10%) were most likely to have an unplanned readmission, followed by fee-for-service patients (9.5%), self-pay (8%), and HMO (5.5%) patients (P = .02).

Dr. Engelbert observed that vascular surgery outcomes have come under scrutiny and that there has been some discussion of cutbacks in Medicare reimbursement given its high rates of readmission.

"This is already starting to happen for certain medical patient populations and if this were to happen, it would significantly affect a vascular service?s practice because a majority of our patients are covered by Medicare and have a higher readmission rate," he said.

The analysis suggests that vascular surgeons may also want to pay closer attention to discharge destination for their patients. Readmission rates were about three times higher for patients discharged to a rehabilitation facility or skilled nursing facility than for those discharged home (19.2% and 16.2% vs. 6.2%; P less than .01).

"The discharge destination matters," Dr. Engelbert said. "... We need to have improved coordination between hospitals and postdischarge destinations. And, we also might need to look at how these patients are cared for and if they are discharged to the appropriate level of care when they?re discharged to these skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities."

The effects of discharge destination (odds ratio, 1.54 skilled nursing facility), index length of stay (OR, 1.03), insurance (OR, 0.43 HMO), and lower-extremity revascularization or amputation (OR, 2.35) persisted in multivariable logistic regression analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, proximity to hospital, clinic follow-up time, urgent vs. elective admission, insurance type, procedure type, length of stay, and discharge destination.

Dr. Engelbert had no conflicts.

CHICAGO - Lower-extremity revascularization or amputation was among the strongest predictors of 30-day vascular surgery readmission in what is being described as the largest single-center review in this setting to date. Lower-extremity revascularization and amputations made up 63% of unplanned readmissions, though rates for endovascular lower-extremity revascularization were almost half that of open revascularization (8.2% vs. 15%).

Notably, below-knee amputations fared the worst, with a 30-day unplanned readmission rate of 24%, compared with 13.3% for above-knee amputations and 16.4% for foot amputation.

"Amputations and open lower-extremity revascularization had the highest rates of readmission in this analysis and therefore we need to focus our efforts and find additional postoperative [management] strategies for these two subgroups," Dr. Travis L. Engelbert said at the annual meeting of the Midwestern Vascular Surgical Society.

The analysis involved 2,505 patients who underwent vascular surgery at the University of Wisconsin Hospitals and Clinics in Madison from 2009 to mid-2013. The overall readmission rate was 9.7% (n = 244). Of these, 147 patients (60.2%) were readmitted to the vascular surgery service.

The most common readmitting diagnosis was wound complication or infection in 37%, said Dr. Engelbert, a vascular surgeon at the university.

Patients whose index admission was urgent rather than elective had significantly higher readmission rates (14.6% vs. 6.9%; P less than .001), as did those living remotely rather than inside Dane County, where the university is located (12% vs. 8.8%; P = .02).

Not surprisingly, higher illness severity, as calculated using the 3M APR DRG software, was significantly associated with readmission (15.6% high vs. 4.3% low severity; P less than .001).

Patients who were readmitted had a longer initial length of stay (8.5 days vs. 6.1 days; P less than .01), and were more likely to have an ICU admission (18.3% vs. 9.5% without ICU stay; P less than .05), he reported.

Based on insurance status, patients covered by Medicaid (16.8%) and Medicare (10%) were most likely to have an unplanned readmission, followed by fee-for-service patients (9.5%), self-pay (8%), and HMO (5.5%) patients (P = .02).

Dr. Engelbert observed that vascular surgery outcomes have come under scrutiny and that there has been some discussion of cutbacks in Medicare reimbursement given its high rates of readmission.

"This is already starting to happen for certain medical patient populations and if this were to happen, it would significantly affect a vascular service?s practice because a majority of our patients are covered by Medicare and have a higher readmission rate," he said.

The analysis suggests that vascular surgeons may also want to pay closer attention to discharge destination for their patients. Readmission rates were about three times higher for patients discharged to a rehabilitation facility or skilled nursing facility than for those discharged home (19.2% and 16.2% vs. 6.2%; P less than .01).

"The discharge destination matters," Dr. Engelbert said. "... We need to have improved coordination between hospitals and postdischarge destinations. And, we also might need to look at how these patients are cared for and if they are discharged to the appropriate level of care when they?re discharged to these skilled nursing and rehabilitation facilities."

The effects of discharge destination (odds ratio, 1.54 skilled nursing facility), index length of stay (OR, 1.03), insurance (OR, 0.43 HMO), and lower-extremity revascularization or amputation (OR, 2.35) persisted in multivariable logistic regression analysis that controlled for age, sex, race, proximity to hospital, clinic follow-up time, urgent vs. elective admission, insurance type, procedure type, length of stay, and discharge destination.

Dr. Engelbert had no conflicts.

Veith's Views: The Blacksnake Phenomenon

Two young men went camping in the wilderness. One of them went off to gather firewood. He returned an hour later, staggering, badly battered, very bloody and with his clothes in tatters. His friend asked what happened. "I ran into a blacksnake" was the reply. "Everyone knows that blacksnakes are harmless," his friend retorted. "They are not so harmless if they make you jump off a cliff."

How does this story apply to vascular surgery and vascular disease patients? It is very relevant to the management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis, small aneurysms, or nondisabling intermittent claudication -- all conditions that are not dangerous and in most cases cause no serious harm.

Let's look first at asymptomatic carotid stenosis. A healthy, totally asymptomatic 58-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors undergoes a carotid screening exam by a commercial mobile laboratory service. He is told that he has a moderate carotid stenosis and a proper carotid duplex is recommended. This is obtained in the office of a "vascular specialist," and it shows that the patient has a "50%-60% narrowing of his left internal carotid artery." The vascular specialist advises him to have a "minimally invasive" carotid stent placed. This is performed in the local hospital by the vascular specialist. The patient has a "minor stroke" with near complete recovery within 2 months except for some persistent difficulty with fine movements of his right hand and some difficulty finding words. Although the man is able to keep his job, he is not as skilled at it as he was.

This patient is a victim of the blacksnake phenomenon. Although his carotid stenosis had more than a 95% chance of causing him no future harm, he suffered a somewhat disabling stroke that he would not have had if he had not undergone the screening exam. In other words the detection of the lesion and its unnecessary invasive treatment lead to a problem that otherwise would not have occurred.

Another example of a potential blacksnake phenomenon occurred in a 74-year-old retired hand surgeon with a 4.1-cm (diameter) abdominal aortic aneurysm. In 2004 this patient saw a vascular surgeon who was then chief of service at a major university center that was just beginning to perform EVAR. The patient had favorable anatomy for EVAR, and the vascular surgeon apparently wished to increase his limited experience with the procedure. The patient was advised to have the EVAR procedure "as soon as possible." He sought a second opinion and was advised to have his aneurysm observed periodically. Ten years later the patient remains well, and the aneurysm still has a diameter of 4.1 cm. If this patient had had an urgent EVAR in 2004 and had had any complication, it would have been a clear example of the blacksnake phenomenon. The fact-based second opinion and the patient's willingness to follow the appropriately conservative option spared him any exposure to the risk of treating a largely harmless condition. Harm from the blacksnake phenomenon was avoided.

Another patient who was spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon was a 58-year-old hypertensive hyperlipidemic smoker who had had a coronary artery bypass and who sought a second opinion for treatment of two block left calf claudication. The patient had had three endovascular procedures by a "vascular specialist" for a long superficial femoral artery occlusion which was causing the same symptom. All three interventions had failed, and a bypass had been suggested by the same specialist. The second opinion work-up revealed that the patient shockingly had not been placed on statins, had not been advised to stop smoking, and was not being treated for his hypertension by his intervening vascular specialist or the cardiologist who had referred the patient for his three interventions. Nor had he been told that his uncorrected femoral artery occlusion posed little risk to his limb or his life. The vascular surgeon providing the second opinion advised no treatment for the femoral occlusion, but placed the patient on statins, anti-hypertensives, and other medical measures. Had the patient undergone a fourth intervention or a bypass for the femoral occlusion, his risks would have been substantial. Avoiding these risks spared the patient the likelihood of being victimized by the blacksnake phenomenon.

All these cases are real. Yet all are examples of an actual or potential blacksnake phenomenon which can and does occur commonly in our system of vascular care. These cases emphasize that patients can be harmed by the blacksnake phenomenon, which results from the benign natural history of many vascular lesions which are better left uncorrected. Fixing such lesions simply because they exist and are detected causes more harm than benefit to patients. Many self-appointed vascular specialists are not fully aware of this benign natural history. Others, it seems, choose to ignore it, perhaps for bad motives. However, it behooves all specialists that treat non-coronary vascular disease to be aware of the natural history of various lesions and conditions, so that they do not treat patients with them unnecessarily or for the wrong reasons.

Moreover, they must be aware of and utilize optimal medical treatments for these lesions and conditions. In that way patients can be spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon, and real vascular specialists can provide the best overall care for their patients.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

Two young men went camping in the wilderness. One of them went off to gather firewood. He returned an hour later, staggering, badly battered, very bloody and with his clothes in tatters. His friend asked what happened. "I ran into a blacksnake" was the reply. "Everyone knows that blacksnakes are harmless," his friend retorted. "They are not so harmless if they make you jump off a cliff."

How does this story apply to vascular surgery and vascular disease patients? It is very relevant to the management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis, small aneurysms, or nondisabling intermittent claudication -- all conditions that are not dangerous and in most cases cause no serious harm.

Let's look first at asymptomatic carotid stenosis. A healthy, totally asymptomatic 58-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors undergoes a carotid screening exam by a commercial mobile laboratory service. He is told that he has a moderate carotid stenosis and a proper carotid duplex is recommended. This is obtained in the office of a "vascular specialist," and it shows that the patient has a "50%-60% narrowing of his left internal carotid artery." The vascular specialist advises him to have a "minimally invasive" carotid stent placed. This is performed in the local hospital by the vascular specialist. The patient has a "minor stroke" with near complete recovery within 2 months except for some persistent difficulty with fine movements of his right hand and some difficulty finding words. Although the man is able to keep his job, he is not as skilled at it as he was.

This patient is a victim of the blacksnake phenomenon. Although his carotid stenosis had more than a 95% chance of causing him no future harm, he suffered a somewhat disabling stroke that he would not have had if he had not undergone the screening exam. In other words the detection of the lesion and its unnecessary invasive treatment lead to a problem that otherwise would not have occurred.

Another example of a potential blacksnake phenomenon occurred in a 74-year-old retired hand surgeon with a 4.1-cm (diameter) abdominal aortic aneurysm. In 2004 this patient saw a vascular surgeon who was then chief of service at a major university center that was just beginning to perform EVAR. The patient had favorable anatomy for EVAR, and the vascular surgeon apparently wished to increase his limited experience with the procedure. The patient was advised to have the EVAR procedure "as soon as possible." He sought a second opinion and was advised to have his aneurysm observed periodically. Ten years later the patient remains well, and the aneurysm still has a diameter of 4.1 cm. If this patient had had an urgent EVAR in 2004 and had had any complication, it would have been a clear example of the blacksnake phenomenon. The fact-based second opinion and the patient's willingness to follow the appropriately conservative option spared him any exposure to the risk of treating a largely harmless condition. Harm from the blacksnake phenomenon was avoided.

Another patient who was spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon was a 58-year-old hypertensive hyperlipidemic smoker who had had a coronary artery bypass and who sought a second opinion for treatment of two block left calf claudication. The patient had had three endovascular procedures by a "vascular specialist" for a long superficial femoral artery occlusion which was causing the same symptom. All three interventions had failed, and a bypass had been suggested by the same specialist. The second opinion work-up revealed that the patient shockingly had not been placed on statins, had not been advised to stop smoking, and was not being treated for his hypertension by his intervening vascular specialist or the cardiologist who had referred the patient for his three interventions. Nor had he been told that his uncorrected femoral artery occlusion posed little risk to his limb or his life. The vascular surgeon providing the second opinion advised no treatment for the femoral occlusion, but placed the patient on statins, anti-hypertensives, and other medical measures. Had the patient undergone a fourth intervention or a bypass for the femoral occlusion, his risks would have been substantial. Avoiding these risks spared the patient the likelihood of being victimized by the blacksnake phenomenon.

All these cases are real. Yet all are examples of an actual or potential blacksnake phenomenon which can and does occur commonly in our system of vascular care. These cases emphasize that patients can be harmed by the blacksnake phenomenon, which results from the benign natural history of many vascular lesions which are better left uncorrected. Fixing such lesions simply because they exist and are detected causes more harm than benefit to patients. Many self-appointed vascular specialists are not fully aware of this benign natural history. Others, it seems, choose to ignore it, perhaps for bad motives. However, it behooves all specialists that treat non-coronary vascular disease to be aware of the natural history of various lesions and conditions, so that they do not treat patients with them unnecessarily or for the wrong reasons.

Moreover, they must be aware of and utilize optimal medical treatments for these lesions and conditions. In that way patients can be spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon, and real vascular specialists can provide the best overall care for their patients.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

Two young men went camping in the wilderness. One of them went off to gather firewood. He returned an hour later, staggering, badly battered, very bloody and with his clothes in tatters. His friend asked what happened. "I ran into a blacksnake" was the reply. "Everyone knows that blacksnakes are harmless," his friend retorted. "They are not so harmless if they make you jump off a cliff."

How does this story apply to vascular surgery and vascular disease patients? It is very relevant to the management of asymptomatic carotid stenosis, small aneurysms, or nondisabling intermittent claudication -- all conditions that are not dangerous and in most cases cause no serious harm.

Let's look first at asymptomatic carotid stenosis. A healthy, totally asymptomatic 58-year-old man with no cardiovascular risk factors undergoes a carotid screening exam by a commercial mobile laboratory service. He is told that he has a moderate carotid stenosis and a proper carotid duplex is recommended. This is obtained in the office of a "vascular specialist," and it shows that the patient has a "50%-60% narrowing of his left internal carotid artery." The vascular specialist advises him to have a "minimally invasive" carotid stent placed. This is performed in the local hospital by the vascular specialist. The patient has a "minor stroke" with near complete recovery within 2 months except for some persistent difficulty with fine movements of his right hand and some difficulty finding words. Although the man is able to keep his job, he is not as skilled at it as he was.

This patient is a victim of the blacksnake phenomenon. Although his carotid stenosis had more than a 95% chance of causing him no future harm, he suffered a somewhat disabling stroke that he would not have had if he had not undergone the screening exam. In other words the detection of the lesion and its unnecessary invasive treatment lead to a problem that otherwise would not have occurred.

Another example of a potential blacksnake phenomenon occurred in a 74-year-old retired hand surgeon with a 4.1-cm (diameter) abdominal aortic aneurysm. In 2004 this patient saw a vascular surgeon who was then chief of service at a major university center that was just beginning to perform EVAR. The patient had favorable anatomy for EVAR, and the vascular surgeon apparently wished to increase his limited experience with the procedure. The patient was advised to have the EVAR procedure "as soon as possible." He sought a second opinion and was advised to have his aneurysm observed periodically. Ten years later the patient remains well, and the aneurysm still has a diameter of 4.1 cm. If this patient had had an urgent EVAR in 2004 and had had any complication, it would have been a clear example of the blacksnake phenomenon. The fact-based second opinion and the patient's willingness to follow the appropriately conservative option spared him any exposure to the risk of treating a largely harmless condition. Harm from the blacksnake phenomenon was avoided.

Another patient who was spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon was a 58-year-old hypertensive hyperlipidemic smoker who had had a coronary artery bypass and who sought a second opinion for treatment of two block left calf claudication. The patient had had three endovascular procedures by a "vascular specialist" for a long superficial femoral artery occlusion which was causing the same symptom. All three interventions had failed, and a bypass had been suggested by the same specialist. The second opinion work-up revealed that the patient shockingly had not been placed on statins, had not been advised to stop smoking, and was not being treated for his hypertension by his intervening vascular specialist or the cardiologist who had referred the patient for his three interventions. Nor had he been told that his uncorrected femoral artery occlusion posed little risk to his limb or his life. The vascular surgeon providing the second opinion advised no treatment for the femoral occlusion, but placed the patient on statins, anti-hypertensives, and other medical measures. Had the patient undergone a fourth intervention or a bypass for the femoral occlusion, his risks would have been substantial. Avoiding these risks spared the patient the likelihood of being victimized by the blacksnake phenomenon.

All these cases are real. Yet all are examples of an actual or potential blacksnake phenomenon which can and does occur commonly in our system of vascular care. These cases emphasize that patients can be harmed by the blacksnake phenomenon, which results from the benign natural history of many vascular lesions which are better left uncorrected. Fixing such lesions simply because they exist and are detected causes more harm than benefit to patients. Many self-appointed vascular specialists are not fully aware of this benign natural history. Others, it seems, choose to ignore it, perhaps for bad motives. However, it behooves all specialists that treat non-coronary vascular disease to be aware of the natural history of various lesions and conditions, so that they do not treat patients with them unnecessarily or for the wrong reasons.

Moreover, they must be aware of and utilize optimal medical treatments for these lesions and conditions. In that way patients can be spared exposure to the blacksnake phenomenon, and real vascular specialists can provide the best overall care for their patients.

Dr. Veith is Professor of Surgery at New York University Medical Center and the Cleveland Clinic. He is an associate medical editor for Vascular Specialist.

The ideas and opinions expressed in Vascular Specialist do not necessarily reflect those of the Society or Publisher.

Diastolic heart failure and TOPCAT

The TOPCAT study, reported at the recent American Heart Association meeting in Dallas, examined the murky world of our understanding of heart failure occurring in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

That seeming paradox has been the subject of physiologic and therapeutic controversy for some time. The realization that at least half of the patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure have normal or even supernormal left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF) has raised the therapeutic importance of this clinical entity. Of even more importance is the fact that patients with HFpEF exhibit morbidity and mortality similar to those heart failure patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF).

In an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:251-9), the 1-year mortality was 29% for HFpEF and 32% for HFrEF. Patients with HFpEF were more likely to be female (65.7% vs. 34.6%) and to have hypertension and atrial fibrillation than were those with HFrEF (62.7% vs. 48% and 41.3% vs. 28.5%, respectively).

Although we have significantly impacted mortality in patients who have HFrEF with the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardiac defibrillators, and medical therapy with beta-blockers and renin angiotensin inhibitors, we have failed to modify clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF.

This has not been for a lack of trying. Several randomized clinical trials have been conducted with all of the drugs currently being used for HFrEF without any definitive results. An important problem in treating this population has been the heterogeneity of patients and multiple comorbidities, including chronic renal and pulmonary disease, acute hypertension, and atrial fibrillation that patients with HFpEF experience with the acute event. In addition, many of these patients are already receiving a multiplicity of concurrent therapies that have been approved for HFrEF for management.

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of HFpEF also remains cloudy. Both left and right ventricular hypertrophy with concomitant decrease in ventricular diastolic relaxation is the common observed echocardiographic abnormality. We have not as yet developed therapy for the treatment of diastolic dysfunction. Aldosterone antagonists, previously shown to be beneficial in patients with HFrEF, have emerged as likely candidates to improve HFpEF. Small clinical studies have shown improvement in diastolic function in elderly patients with hypertension and chronic renal disease. Consequently, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute embarked on the TOPCAT study in 2006.

TOPCAT randomized 3,345 symptomatic heart failure patients who had a heart failure hospitalization in the previous year and with evidence of fluid retention, a left ventricular ejection fraction of more than 45%, controlled systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg, and elevated brain natriuretic peptide to treatment with placebo or spironolactone at 25 or 50 mg daily. A history of hypertension was present in 91%, coronary artery disease in 57%, atrial fibrillation in 35%, chronic renal disease in 35%, and diabetes in 32%. Patients included in the study had a mean LVEF of 56%; two thirds were in New York Heart Association class II and one third were in NYHA class III.

Over 80% of patients were receiving an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, beta-blockers, and a diuretic. The mean dose of spironolactone was 25 mg. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal hospitalization or resuscitated cardiac arrest in the placebo and treated groups (20.4% and 18.6%, respectively). There was a significant decrease in heart failure hospitalization in the placebo compared to spironolactone patients (14.2% vs. 12.0%; P = .042). Both hyperkalemia greater than 5.5 mmol/L and an increase in serum creatinine were observed in the treated patients.

The striking observation in this trial, as it has been in previous trials, is the disparity between the epidemiologic mortality and the randomized controlled trial experience: 29% annual mortality in Olmsted County, compared with the 10.2% three-year mortality in TOPCAT. It appears that we are studying two separate diseases. And we are. After all the exclusion criteria included in the design of TOPCAT, we are unable to encapsulate the population at risk in this complex heart failure syndrome.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The TOPCAT study, reported at the recent American Heart Association meeting in Dallas, examined the murky world of our understanding of heart failure occurring in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

That seeming paradox has been the subject of physiologic and therapeutic controversy for some time. The realization that at least half of the patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure have normal or even supernormal left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF) has raised the therapeutic importance of this clinical entity. Of even more importance is the fact that patients with HFpEF exhibit morbidity and mortality similar to those heart failure patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF).

In an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:251-9), the 1-year mortality was 29% for HFpEF and 32% for HFrEF. Patients with HFpEF were more likely to be female (65.7% vs. 34.6%) and to have hypertension and atrial fibrillation than were those with HFrEF (62.7% vs. 48% and 41.3% vs. 28.5%, respectively).

Although we have significantly impacted mortality in patients who have HFrEF with the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardiac defibrillators, and medical therapy with beta-blockers and renin angiotensin inhibitors, we have failed to modify clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF.

This has not been for a lack of trying. Several randomized clinical trials have been conducted with all of the drugs currently being used for HFrEF without any definitive results. An important problem in treating this population has been the heterogeneity of patients and multiple comorbidities, including chronic renal and pulmonary disease, acute hypertension, and atrial fibrillation that patients with HFpEF experience with the acute event. In addition, many of these patients are already receiving a multiplicity of concurrent therapies that have been approved for HFrEF for management.

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of HFpEF also remains cloudy. Both left and right ventricular hypertrophy with concomitant decrease in ventricular diastolic relaxation is the common observed echocardiographic abnormality. We have not as yet developed therapy for the treatment of diastolic dysfunction. Aldosterone antagonists, previously shown to be beneficial in patients with HFrEF, have emerged as likely candidates to improve HFpEF. Small clinical studies have shown improvement in diastolic function in elderly patients with hypertension and chronic renal disease. Consequently, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute embarked on the TOPCAT study in 2006.

TOPCAT randomized 3,345 symptomatic heart failure patients who had a heart failure hospitalization in the previous year and with evidence of fluid retention, a left ventricular ejection fraction of more than 45%, controlled systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg, and elevated brain natriuretic peptide to treatment with placebo or spironolactone at 25 or 50 mg daily. A history of hypertension was present in 91%, coronary artery disease in 57%, atrial fibrillation in 35%, chronic renal disease in 35%, and diabetes in 32%. Patients included in the study had a mean LVEF of 56%; two thirds were in New York Heart Association class II and one third were in NYHA class III.

Over 80% of patients were receiving an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, beta-blockers, and a diuretic. The mean dose of spironolactone was 25 mg. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal hospitalization or resuscitated cardiac arrest in the placebo and treated groups (20.4% and 18.6%, respectively). There was a significant decrease in heart failure hospitalization in the placebo compared to spironolactone patients (14.2% vs. 12.0%; P = .042). Both hyperkalemia greater than 5.5 mmol/L and an increase in serum creatinine were observed in the treated patients.

The striking observation in this trial, as it has been in previous trials, is the disparity between the epidemiologic mortality and the randomized controlled trial experience: 29% annual mortality in Olmsted County, compared with the 10.2% three-year mortality in TOPCAT. It appears that we are studying two separate diseases. And we are. After all the exclusion criteria included in the design of TOPCAT, we are unable to encapsulate the population at risk in this complex heart failure syndrome.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

The TOPCAT study, reported at the recent American Heart Association meeting in Dallas, examined the murky world of our understanding of heart failure occurring in patients with preserved left ventricular ejection fraction.

That seeming paradox has been the subject of physiologic and therapeutic controversy for some time. The realization that at least half of the patients admitted to the hospital with heart failure have normal or even supernormal left ventricular ejection fraction (HFpEF) has raised the therapeutic importance of this clinical entity. Of even more importance is the fact that patients with HFpEF exhibit morbidity and mortality similar to those heart failure patients with reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (HFrEF).

In an epidemiologic study in Olmsted County, Minnesota (N. Engl. J. Med. 2006;355:251-9), the 1-year mortality was 29% for HFpEF and 32% for HFrEF. Patients with HFpEF were more likely to be female (65.7% vs. 34.6%) and to have hypertension and atrial fibrillation than were those with HFrEF (62.7% vs. 48% and 41.3% vs. 28.5%, respectively).

Although we have significantly impacted mortality in patients who have HFrEF with the use of cardiac resynchronization therapy, implantable cardiac defibrillators, and medical therapy with beta-blockers and renin angiotensin inhibitors, we have failed to modify clinical outcomes in patients with HFpEF.

This has not been for a lack of trying. Several randomized clinical trials have been conducted with all of the drugs currently being used for HFrEF without any definitive results. An important problem in treating this population has been the heterogeneity of patients and multiple comorbidities, including chronic renal and pulmonary disease, acute hypertension, and atrial fibrillation that patients with HFpEF experience with the acute event. In addition, many of these patients are already receiving a multiplicity of concurrent therapies that have been approved for HFrEF for management.

Our understanding of the pathophysiology of HFpEF also remains cloudy. Both left and right ventricular hypertrophy with concomitant decrease in ventricular diastolic relaxation is the common observed echocardiographic abnormality. We have not as yet developed therapy for the treatment of diastolic dysfunction. Aldosterone antagonists, previously shown to be beneficial in patients with HFrEF, have emerged as likely candidates to improve HFpEF. Small clinical studies have shown improvement in diastolic function in elderly patients with hypertension and chronic renal disease. Consequently, the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute embarked on the TOPCAT study in 2006.

TOPCAT randomized 3,345 symptomatic heart failure patients who had a heart failure hospitalization in the previous year and with evidence of fluid retention, a left ventricular ejection fraction of more than 45%, controlled systolic blood pressure of less than 140 mm Hg, and elevated brain natriuretic peptide to treatment with placebo or spironolactone at 25 or 50 mg daily. A history of hypertension was present in 91%, coronary artery disease in 57%, atrial fibrillation in 35%, chronic renal disease in 35%, and diabetes in 32%. Patients included in the study had a mean LVEF of 56%; two thirds were in New York Heart Association class II and one third were in NYHA class III.

Over 80% of patients were receiving an ACE inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker, beta-blockers, and a diuretic. The mean dose of spironolactone was 25 mg. There was no significant difference in the primary outcome of cardiovascular death, nonfatal hospitalization or resuscitated cardiac arrest in the placebo and treated groups (20.4% and 18.6%, respectively). There was a significant decrease in heart failure hospitalization in the placebo compared to spironolactone patients (14.2% vs. 12.0%; P = .042). Both hyperkalemia greater than 5.5 mmol/L and an increase in serum creatinine were observed in the treated patients.

The striking observation in this trial, as it has been in previous trials, is the disparity between the epidemiologic mortality and the randomized controlled trial experience: 29% annual mortality in Olmsted County, compared with the 10.2% three-year mortality in TOPCAT. It appears that we are studying two separate diseases. And we are. After all the exclusion criteria included in the design of TOPCAT, we are unable to encapsulate the population at risk in this complex heart failure syndrome.

Dr. Goldstein, medical editor of Cardiology News, is professor of medicine at Wayne State University and division head emeritus of cardiovascular medicine at Henry Ford Hospital, both in Detroit. He is on data safety monitoring committees for the National Institutes of Health and several pharmaceutical companies.

UCSF Hospitalist Mini‐College

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

Program Description

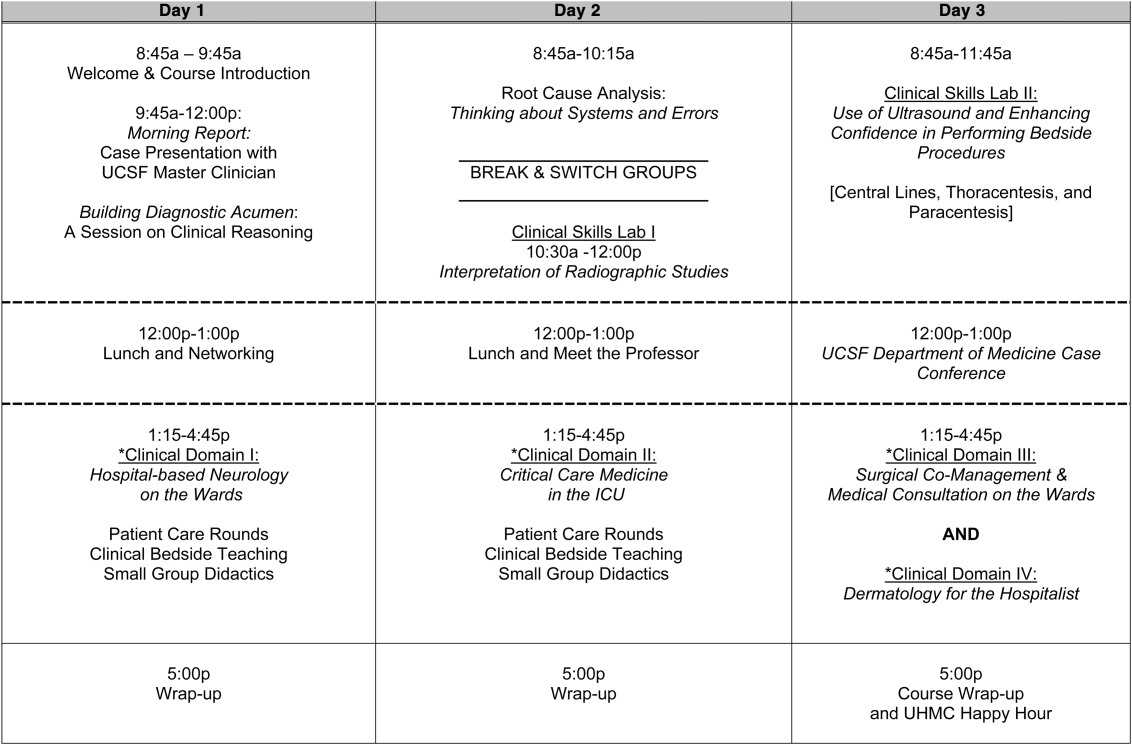

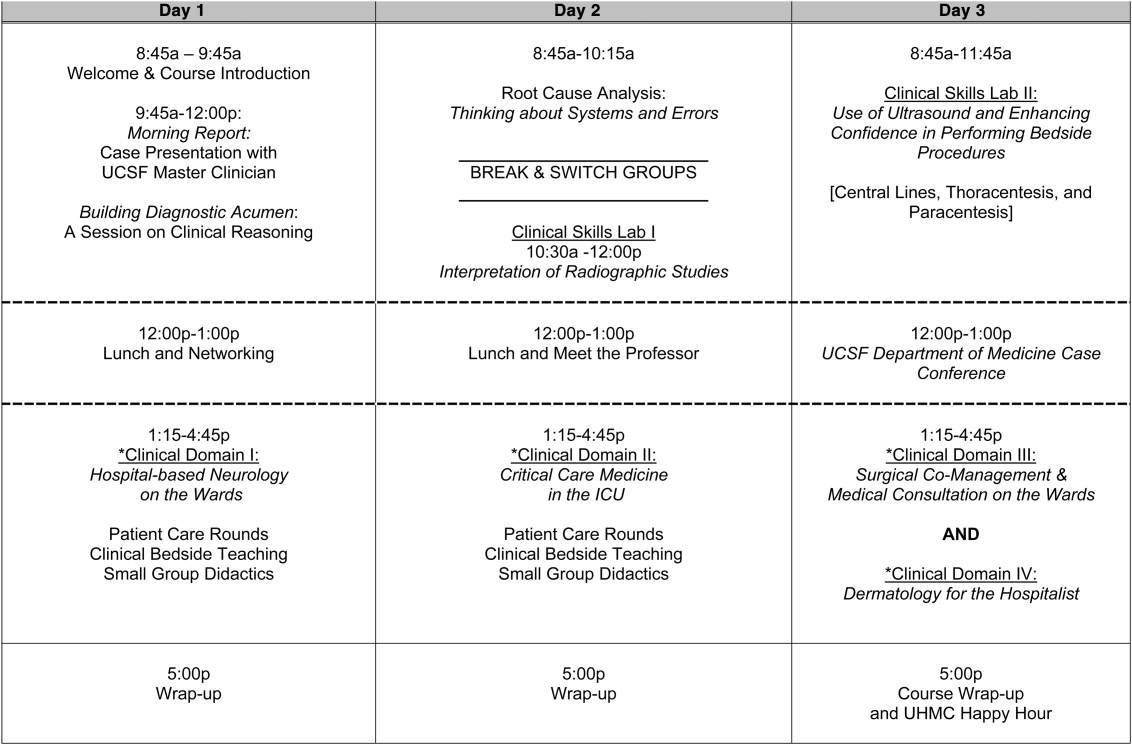

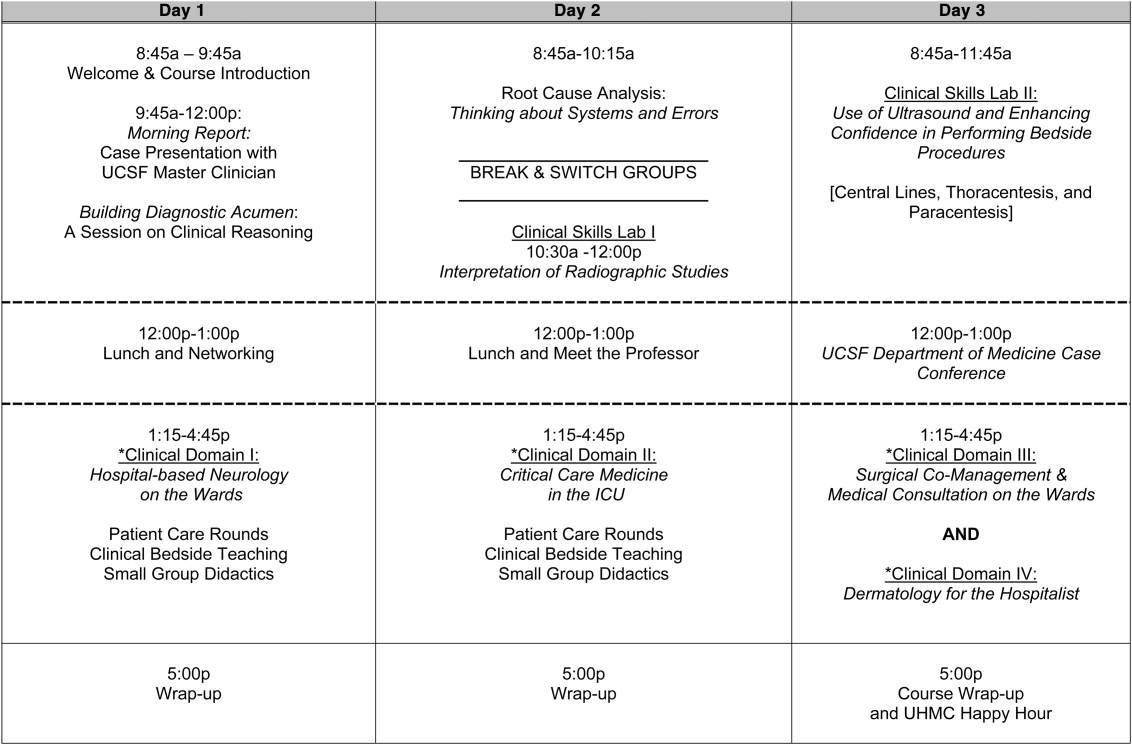

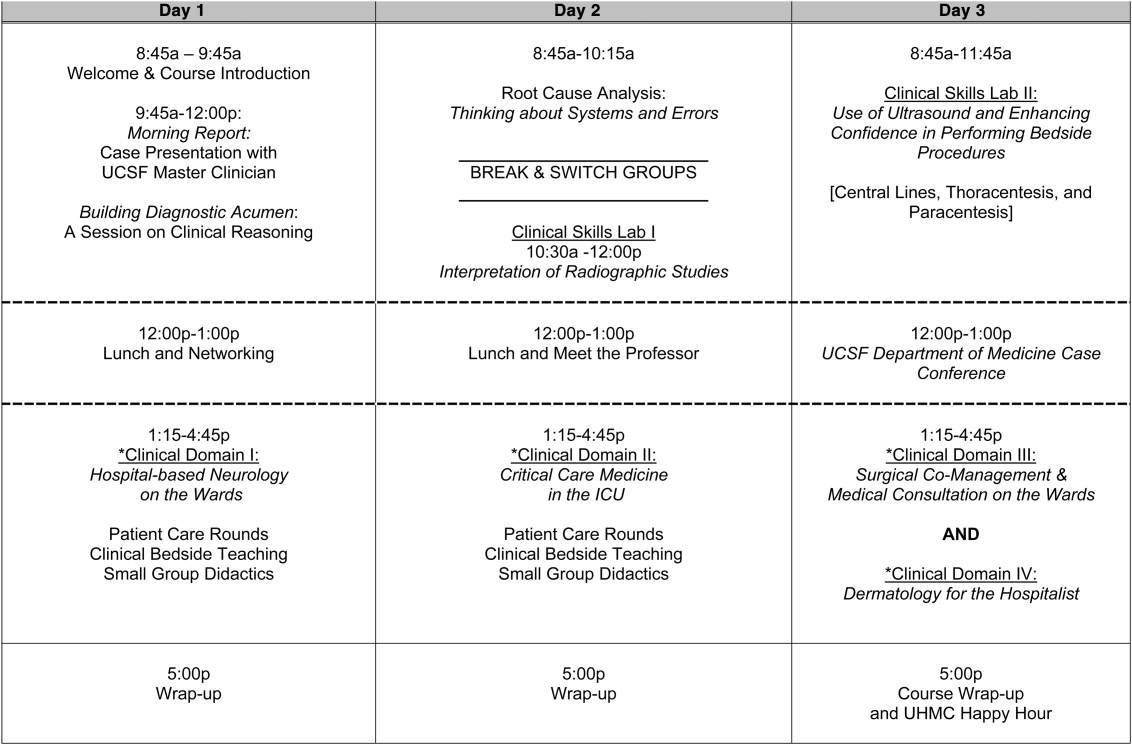

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics

During the first 5 years of the UHMC, 152 participants enrolled and completed the program; 91% completed the pre‐UHMC survey and 89% completed the postcourse evaluation. Table 1 describes the self‐reported participant demographics, including years in practice, number of hospitalist jobs, overall job satisfaction, and time spent doing clinical work. Overall, 68% of all participants had been self‐described hospitalists for 4 years, with 62% holding only 1 hospitalist job during that time; 77% reported being pretty or very satisfied with their jobs, and 72% reported clinical care as the attribute they love most in their job. Table 2 highlights the type of work attendees participate in within their clinical practice. More than half manage patients with neurologic disorders and care for critically ill patients, whereas virtually all perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=4) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average (n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| How long have you been a hospitalist? | 2 years | 52% | 35% | 37% | 30% | 25% | 36% |

| 24 years | 26% | 39% | 30% | 30% | 38% | 32% | |

| 510 years | 11% | 17% | 15% | 26% | 29% | 20% | |

| >10 years | 11% | 9% | 18% | 14% | 8% | 12% | |

| How many hospitalist jobs have you had? | 1 | 63% | 61% | 62% | 62% | 58% | 62% |

| 2 to 3 | 37% | 35% | 23% | 35% | 29% | 32% | |

| >3 | 0% | 4% | 15% | 1% | 13% | 5% | |

| How satisfied are you with your current position? | Not satisfied | 1% | 4% | 4% | 4% | 0% | 4% |

| Somewhat satisfied | 11% | 13% | 39% | 17% | 17% | 19% | |

| Pretty satisfied | 59% | 52% | 35% | 57% | 38% | 48% | |

| Very satisfied | 26% | 30% | 23% | 22% | 46% | 29% | |

| What do you love most about your job? | Clinical care | 85% | 61% | 65% | 84% | 67% | 72% |

| Teaching | 1% | 17% | 12% | 1% | 4% | 7% | |

| QI or safety work | 0% | 4% | 0% | 1% | 8% | 3% | |

| Other (not specified) | 14% | 18% | 23% | 14% | 21% | 18% | |

| What percent of your time is spent doing clinical care? | 100% | 39% | 36% | 52% | 46% | 58% | 46% |

| 75%100% | 58% | 50% | 37% | 42% | 33% | 44% | |

| 5075% | 0% | 9% | 11% | 12% | 4% | 7% | |

| 25%50% | 4% | 5% | 0% | 0% | 5% | 3% | |

| 25% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | 0% | |

| Question | Response Options | 2008 (n=24) | 2009 (n=26) | 2010 (n=29) | 2011 (n=31) | 2012 (n=28) | Average(n=138) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||

| Do you primarily manage patients with neurologic disorders in your hospital? | Yes | 62% | 50% | 62% | 62% | 63% | 60% |

| Do you primarily manage critically ill ICU patients in your hospital? | Yes and without an intensivist | 19% | 23% | 19% | 27% | 21% | 22% |

| Yes but with an intensivist | 54% | 50% | 44% | 42% | 67% | 51% | |

| No | 27% | 27% | 37% | 31% | 13% | 27% | |

| Do you perform preoperative medical evaluations and medical consultation? | Yes | 96% | 91% | 96% | 96% | 92% | 94% |

| Which of the following describes your role in the care of surgical patients? | Traditional medical consultant | 33% | 28% | 28% | 30% | 24% | 29% |

| Comanagement (shared responsibility with surgeon) | 33% | 34% | 42% | 39% | 35% | 37% | |

| Attending of record with surgeon acting as consultant | 26% | 24% | 26% | 30% | 35% | 28% | |

| Do you have bedside ultrasound available in your daily practice? | Yes | 38% | 32% | 52% | 34% | 38% | 39% |

Participant Experience

Overall, participants rated the quality of the UHMC course highly (4.65; 15 scale). The neurology clinical domain (4.83) and clinical reasoning session (4.72) were the highest‐rated sessions. Compared to all UCSF CME course offerings between January 2010 and September 2012, the UHMC rated higher than the cumulative overall rating from those 227 courses (4.65 vs 4.44). For UCSF CME courses offered in 2011 and 2012, 78% of participants (n=11,447) reported a high or definite likelihood to change practice. For UHMC participants during the same time period (n=57), 98% reported a similar likelihood to change practice. Table 3 provides selected participant comments from their postcourse evaluations.

|

| Great pearls, broad ranging discussion of many controversial and common topics, and I loved the teaching format. |

| I thought the conception of the teaching model was really effectivehands‐on exams in small groups, each demonstrating a different part of the neurologic exam, followed by presentation and discussion, and ending in bedside rounds with the teaching faculty. |

| Excellent review of key topicswide variety of useful and practical points. Very high application value. |

| Great course. I'd take it again and again. It was a superb opportunity to review technique, equipment, and clinical decision making. |

| Overall outstanding course! Very informative and fun. Format was great. |

| Forward and clinically relevant. Like the bedside teaching and how they did it.The small size of the course and the close attention paid by the faculty teaching the course combined with the opportunity to see and examine patients in the hospital was outstanding. |

DISCUSSION

We developed an innovative CME program that brought participants to an academic health center for a participatory, hands‐on, and small‐group experience. They learned about topics relevant to today's hospitalists, rated the experience very highly, and reported a nearly unanimous likelihood to change their practice. Reflecting on our program's first 5 years, there were several lessons learned that may guide others committed to providing a similar CME experience.

First, hospital medicine is a dynamic field. Conducting a needs assessment to match clinical topics to what attendees required in their own practice was critical. Iterative changes from year to year reflected formal participant feedback as well as informal conversations with the teaching faculty. For instance, attendees were not only interested in the clinical topics but often wanted to see examples of clinical pathways, order sets, and other systems in place to improve care for patients with common conditions. Our participant presurvey also helped identify and reinforce the curricular topics that teaching faculty focused on each year. Being responsive to the changing needs of hospitalists and the environment is a crucial part of providing a relevant CME experience.

We also used an innovative approach to teaching, founded in adult and effective CME learning principles. CME activities are geared toward adult physicians, and studies of their effectiveness recommend that sessions should be interactive and utilize multiple modalities of learning.[12] When attendees actively participate and are provided an opportunity to practice skills, it may have a positive effect on patient outcomes.[13] All UHMC faculty were required to couple presentations of the latest evidence for clinical topics with small‐group and hands‐on learning modalities. This also required that we utilize a teaching faculty known for both their clinical expertise and teaching recognition. Together, the learning modalities and the teaching faculty likely accounted for the highly rated course experience and likelihood to change practice.

Finally, our course brought participants to an academic medical center and into the mix of clinical care as opposed to the more traditional hotel venue. This was necessary to deliver the curriculum as described, but also had the unexpected benefit of energizing the participants. Many had not been in a teaching setting since their residency training, and bringing them back into this milieu motivated them to learn and share their inspiration. As there are no published studies of CME experiences in the clinical environment, this observation is noteworthy and deserves to be explored and evaluated further.

What are the limitations of our approach to bringing CME to the bedside? First, the economics of an intensive 3‐day course with a maximum of 33 attendees are far different than those of a large hotel‐based offering. There are no exhibitors or outside contributions. The cost of the course to participants is $2500 (discounted if attending the larger course as well), which is 2 to 3 times higher than most traditional CME courses of the same length. Although the cost is high, the course has sold out each year with a waiting list. Part of the cost is also faculty time. The time, preparation, and need to teach on the fly to meet the differing participant educational needs is fundamentally different than delivering a single lecture in a hotel conference room. Not surprisingly, our faculty enjoy this teaching opportunity and find it equally unique and valuable; no faculty have dropped out of teaching the course, and many describe it as 1 of the teaching highlights of the year. Scalability of the UHMC is challenging for these reasons, but our model could be replicated in other teaching institutions, even as a local offering for their own providers.

In summary, we developed a hospital‐based, highly interactive, small‐group CME course that emphasizes case‐based teaching. The course has sold out each year, and evaluations suggest that it is highly valued and is meeting curricular goals better than more traditional CME courses. We hope our course description and success may motivate others to consider moving beyond the traditional CME for hospitalists and explore further innovations. With the field growing and changing at a rapid pace, innovative CME experiences will be necessary to assure that hospitalists continue to provide exemplary and safe care to their patients.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Kapo Tam for her program management of the UHMC, and Katherine Li and Zachary Martin for their invaluable administrative support and coordination. The authors are also indebted to faculty colleagues for their time and roles in teaching within the program. They include Gupreet Dhaliwal, Andy Josephson, Vanja Douglas, Michelle Milic, Brian Daniels, Quinny Cheng, Lindy Fox, Diane Sliwka, Ralph Wang, and Thomas Urbania.

Disclosure: Nothing to report.

- , . The emerging role of “hospitalists” in the American health care system. N Engl J Med. 1996;337(7):514–517.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Membership2/HospitalFocusedPractice/Hospital_Focused_Pra.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Hospital medicine fellowships: works in progress. Am J Med. 2006;119(1):72.e1–e7.

- Society of Hospital Medicine. Core competencies in hospital medicine. Available at: http://www.hospitalmedicine.org/Content/NavigationMenu/Education/CoreCurriculum/Core_Competencies.htm. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , . The expanding role of hospitalists in the United States. Swiss Med Wkly. 2006;136(37‐38);591–596.

- Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education. CME content: definition and examples Available at: http://www.accme.org/requirements/accreditation‐requirements‐cme‐providers/policies‐and‐definitions/cme‐content‐definition‐and‐examples. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- , , , . Changing physician performance. A systematic review of the effect of continuing medical education strategies. JAMA. 1995;274(9):700–705.

- , . Continuing medical education and the physician as a learner: guide to the evidence. JAMA. 2002;288(9):1057–1060.

- , , , , . Barriers to innovation in continuing medical eduation. J Contin Educ Health Prof. 2008;28(3):148–156.

- . Adult learning theory for the 21st century. In: Merriam S. Thrid Update on Adult Learning Theory: New Directions for Adult and Continuing Education. San Francisco, CA: Jossey‐Bass; 2008:93–98.

- .UCSF management of the hospitalized patient CME course. Available at: http://www.ucsfcme.com/2014/MDM14P01/info.html. Accessed October 1, 2013.

- Continuing medical education effect on practice performance: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);42S–48S.

- Continuing medical education effect on clinical outcomes: effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College or Chest Physicians evidence‐based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135(3 suppl);49S–55S.

I hear and I forget, I see and I remember, I do and I understand.

Confucius

Hospital medicine, first described in 1996,[1] is the fastest growing specialty in United States medical history, now with approximately 40,000 practitioners.[2] Although hospitalists undoubtedly learned many of their key clinical skills during residency training, there is no hospitalist‐specific residency training pathway and a limited number of largely research‐oriented fellowships.[3] Furthermore, hospitalists are often asked to care for surgical patients, those with acute neurologic disorders, and patients in intensive care units, while also contributing to quality improvement and patient safety initiatives.[4] This suggests that the vast majority of hospitalists have not had specific training in many key competencies for the field.[5]

Continuing medical education (CME) has traditionally been the mechanism to maintain, develop, or increase the knowledge, skills, and professional performance of physicians.[6] Most CME activities, including those for hospitalists, are staged as live events in hotel conference rooms or as local events in a similarly passive learning environment (eg, grand rounds and medical staff meetings). Online programs, audiotapes, and expanding electronic media provide increasing and alternate methods for hospitalists to obtain their required CME. All of these activities passively deliver content to a group of diverse and experienced learners. They fail to take advantage of adult learning principles and may have little direct impact on professional practice.[7, 8] Traditional CME is often derided as a barrier to innovative educational methods for these reasons, as adults learn best through active participation, when the information is relevant and practically applied.[9, 10]

To provide practicing hospitalists with necessary continuing education, we designed the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Hospitalist Mini‐College (UHMC). This 3‐day course brings adult learners to the bedside for small‐group and active learning focused on content areas relevant to today's hospitalists. We describe the development, content, outcomes, and lessons learned from UHMC's first 5 years.

METHODS

Program Development

We aimed to develop a program that focused on curricular topics that would be highly valued by practicing hospitalists delivered in an active learning small‐group environment. We first conducted an informal needs assessment of community‐based hospitalists to better understand their roles and determine their perceptions of gaps in hospitalist training compared to current requirements for practice. We then reviewed available CME events targeting hospitalists and compared these curricula to the gaps discovered from the needs assessment. We also reviewed the Society of Hospital Medicine's core competencies to further identify gaps in scope of practice.[4] Finally, we reviewed the literature to identify CME curricular innovations in the clinical setting and found no published reports.

Program Setting, Participants, and Faculty

The UHMC course was developed and offered first in 2008 as a precourse to the UCSF Management of the Hospitalized Medicine course, a traditional CME offering that occurs annually in a hotel setting.[11] The UHMC takes place on the campus of UCSF Medical Center, a 600‐bed academic medical center in San Francisco. Registered participants were required to complete limited credentialing paperwork, which allowed them to directly observe clinical care and interact with hospitalized patients. Participants were not involved in any clinical decision making for the patients they met or examined. The course was limited to a maximum of 33 participants annually to optimize active participation, small‐group bedside activities, and a personalized learning experience. UCSF faculty selected to teach in the UHMC were chosen based on exemplary clinical and teaching skills. They collaborated with course directors in the development of their session‐specific goals and curriculum.

Program Description

Figure 1 is a representative calendar view of the 3‐day UHMC course. The curricular topics were selected based on the findings from our needs assessment, our ability to deliver that curriculum using our small‐group active learning framework, and to minimize overlap with content of the larger course. Course curriculum was refined annually based on participant feedback and course director observations.

The program was built on a structure of 4 clinical domains and 2 clinical skills labs. The clinical domains included: (1) Hospital‐Based Neurology, (2) Critical Care Medicine in the Intensive Care Unit, (3) Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation, and (4) Hospital‐Based Dermatology. Participants were divided into 3 groups of 10 participants each and rotated through each domain in the afternoons. The clinical skills labs included: (1) Interpretation of Radiographic Studies and (2) Use of Ultrasound and Enhancing Confidence in Performing Bedside Procedures. We also developed specific sessions to teach about patient safety and to allow course attendees to participate in traditional academic learning vehicles (eg, a Morning Report and Morbidity and Mortality case conference). Below, we describe each session's format and content.

Clinical Domains

Hospital‐Based Neurology

Attendees participated in both bedside evaluation and case‐based discussions of common neurologic conditions seen in the hospital. In small groups of 5, participants were assigned patients to examine on the neurology ward. After their evaluations, they reported their findings to fellow participants and the faculty, setting the foundation for discussion of clinical management, review of neuroimaging, and exploration of current evidence to inform the patient's diagnosis and management. Participants and faculty then returned to the bedside to hone neurologic examination skills and complete the learning process. Given the unpredictability of what conditions would be represented on the ward in a given day, review of commonly seen conditions was always a focus, such as stroke, seizures, delirium, and neurologic examination pearls.

Critical Care

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions of common clinical conditions with similar review of current evidence, relevant imaging, and bedside exam pearls for the intubated patient. For this domain, attendees also participated in an advanced simulation tutorial in ventilator management, which was then applied at the bedside of intubated patients. Specific topics covered include sepsis, decompensated chronic obstructive lung disease, vasopressor selection, novel therapies in critically ill patients, and use of clinical pathways and protocols for improved quality of care.

Surgical Comanagement and Medical Consultation

Attendees participated in case‐based discussions applying current evidence to perioperative controversies and the care of the surgical patient. They also discussed the expanding role of the hospitalist in nonmedical patients.

Hospital‐Based Dermatology

Attendees participated in bedside evaluation of acute skin eruptions based on available patients admitted to the hospital. They discussed the approach to skin eruptions, key diagnoses, and when dermatologists should be consulted for their expertise. Specific topics included drug reactions, the red leg, life‐threating conditions (eg, Stevens‐Johnson syndrome), and dermatologic examination pearls. This domain was added in 2010.

Clinical Skills Labs

Radiology

In groups of 15, attendees reviewed common radiographs that hospitalists frequently order or evaluate (eg, chest x‐rays; kidney, ureter, and bladder; placement of endotracheal or feeding tube). They also reviewed the most relevant and not‐to‐miss findings on other commonly ordered studies such as abdominal or brain computerized tomography scans.

Hospital Procedures With Bedside Ultrasound

Attendees participated in a half‐day session to gain experience with the following procedures: paracentesis, lumbar puncture, thoracentesis, and central lines. They participated in an initial overview of procedural safety followed by hands‐on application sessions, in which they rotated through clinical workstations in groups of 5. At each work station, they were provided an opportunity to practice techniques, including the safe use of ultrasound on both live (standardized patients) and simulation models.

Other Sessions

Building Diagnostic Acumen and Clinical Reasoning

The opening session of the UHMC reintroduces attendees to the traditional academic morning report format, in which a case is presented and participants are asked to assess the information, develop differential diagnoses, discuss management options, and consider their own clinical reasoning skills. This provides frameworks for diagnostic reasoning, highlights common cognitive errors, and teaches attendees how to develop expertise in their own diagnostic thinking. The session also sets the stage and expectation for active learning and participation in the UHMC.

Root Cause Analysis and Systems Thinking

As the only nonclinical session in the UHMC, this session introduces participants to systems thinking and patient safety. Attendees participate in a root cause analysis role play surrounding a serious medical error and discuss the implications, their reflections, and then propose solutions through interactive table discussions. The session also emphasizes the key role hospitalists should play in improving patient safety.

Clinical Case Conference

Attendees participated in the weekly UCSF Department of Medicine Morbidity and Mortality conference. This is a traditional case conference that brings together learners, expert discussants, and an interesting or challenging case. This allows attendees to synthesize much of the course learning through active participation in the case discussion. Rather than creating a new conference for the participants, we brought the participants to the existing conference as part of their UHMC immersion experience.

Meet the Professor

Attendees participated in an informal discussion with a national leader (R.M.W.) in hospital medicine. This allowed for an interactive exchange of ideas and an understanding of the field overall.

Online Search Strategies

This interactive computer lab session allowed participants to explore the ever‐expanding number of online resources to answer clinical queries. This session was replaced in 2010 with the dermatology clinical domain based on participant feedback.

Program Evaluation

Participants completed a pre‐UHMC survey that provided demographic information and attributes about themselves, their clinical practice, and experience. Participants also completed course evaluations consistent with Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education standards following the program. The questions asked for each activity were rated on a 1‐to‐5 scale (1=poor, 5=excellent) and also included open‐ended questions to assess overall experiences.

RESULTS

Participant Demographics