User login

Rivaroxaban shows advantages in AF cardioversion

BARCELONA – Rivaroxaban appears to be a safe and effective alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing elective cardioversion, according to the findings of the first-ever prospective, randomized trial of a novel oral anticoagulant for this application.

Additionally, the X-VeRT trial showed that rivaroxaban (Xarelto) may offer an attractive, highly practical advantage over warfarin, the current guideline-recommended standard of care for cardioversion: Namely, rivaroxaban enabled patients to undergo the procedure more expeditiously, Dr. Riccardo Cappato noted in presenting the X-VeRT findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, patients in the early-cardioversion arm of the trial safely underwent the procedure as early as 4 hours after taking their first 20-mg dose of rivaroxaban.

Moreover, patients in the delayed-conversion study arm, which required at least 3 consecutive weeks of effective oral anticoagulation preprocedurally, underwent cardioversion an average of 8 days earlier if randomized to rivaroxaban rather than to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. That’s because many warfarin-treated patients couldn’t maintain their international normalized ratio (INR) within the target range of 2.0-3.0 for 3 straight weeks, explained Dr. Cappato, professor of electrophysiology and chief of the arrhythmia and electrophysiology center at the University of Milan’s San Donato Polyclinic Hospital.

X-VeRT included 1,504 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) at 141 centers in 16 countries. All were scheduled for elective cardioversion. They were randomized 2:1 to rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily or to warfarin at a dose adjusted to maintain an INR of 2.0-3.0.

Of those patients, 872 were assigned to an early-cardioversion strategy. Their cardioversion took place after 1-5 days on study medication, provided transesophageal echocardiography had ruled out a left atrial thrombus or they were already on chronic warfarin with their last three INRs in the target range. The other 632 patients were cardioverted using a delayed strategy in which they had to be on study medication for 3-8 weeks before the procedure.

The primary efficacy outcome in X-VeRT was the composite rate of stroke, TIA, peripheral embolism, MI, and cardiovascular death. The incidence was 0.51% in the rivaroxaban group and not statistically different at 1.02% in the warfarin group. The primary safety outcome – major bleeding – occurred in 0.6% of rivaroxaban-treated patients and 0.8% on warfarin.

The median time to cardioversion in the early-cardioversion strategy arm was similar regardless of which drug was used. Of note, however, in the delayed-strategy group, the median time to cardioversion was 22 days in patients on rivaroxaban, compared with 30 days with warfarin.

Of patients in the delayed-strategy group, 77% of those on rivaroxaban were cardioverted as scheduled, compared with 36% on warfarin. Only one patient in the rivaroxaban group was unable to undergo cardioversion before the 8-week cutoff because of inadequate anticoagulation as defined by less than 80% compliance in pill taking; in contrast, 95 warfarin-treated patients in the delayed-strategy group weren’t cardioverted because they missed the 8-week cutoff because of problematic INRs.

In an interview, ESC spokesman Dr. Jurrien Ten Berg predicted X-VeRT will be practice changing. He believes that on the basis of these study results, many physicians will view elective cardioversion as an excellent time to switch patients from warfarin, with all its inherent problems, to rivaroxaban, especially if they qualify for early cardioversion.

"I think this will absolutely change our policy. Here we’re talking about a once-daily pill that makes it possible to do a cardioversion early, and I think that’s a major advantage. If you delay the cardioversion, anything can happen. We know the vitamin K antagonists are unreliable, especially in the first weeks, when even if the INR is fine you don’t really know if the patient is well anticoagulated. For me, the totally of evidence, including the retrospective analyses of the large atrial fibrillation stroke prevention trials, is enough now to use a NOAC for several days and then do an early cardioversion," said Dr. Ten Berg, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

Discussant Dr. Christoph Bode called X-VeRT "a landmark trial" and "brilliant work."

"This should be included in the next update of the guidelines," said Dr. Bode, professor and chair of internal medicine and cardiology at the University of Freiburg, Germany.

However, Dr. Steven Nissen took a more skeptical, albeit clearly a minority, view.

"I think this study shows neither safety nor efficacy for this regimen. There were just a handful of events in both groups, too few to draw any conclusions. I don’t think the guidelines should be changed. I think the proper interpretation of the study is that it’s inconclusive," said Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Dr. Cappato noted in response that he’d stated at the outset that X-VeRT, even at more than 1,500 patients, was underpowered statistically. Event rates in well-anticoagulated patients undergoing cardioversion are so low that a study to establish noninferiority for rivaroxaban would require 25,000-30,000 participants, which is not going to happen.

"Many physicians are already switching to NOACs [novel oral anticoagulants] for cardioversion despite the absence of good evidence. We thought bringing forward this solid, methodologically sound information from X-VeRT would provide more consistent support for those who are doing this or considering it," the cardiologist said.

Simultaneous with his presentation in Barcelona, the X-VeRT (Explore the Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Oral Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Scheduled for Cardioversion) study was published online (Eur. Heart J. 2014 [doi:10.1093/eurheart/ehu367]).

Dr. Cappato reported receiving investigator fees from and serving as a consultant to and on speakers bureaus for numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Bayer HealthCare, which sponsored X-VeRT. Dr. Bode has received honoraria from Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Ten Berg and Dr. Nissen reported having no financial conflicts.

BARCELONA – Rivaroxaban appears to be a safe and effective alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing elective cardioversion, according to the findings of the first-ever prospective, randomized trial of a novel oral anticoagulant for this application.

Additionally, the X-VeRT trial showed that rivaroxaban (Xarelto) may offer an attractive, highly practical advantage over warfarin, the current guideline-recommended standard of care for cardioversion: Namely, rivaroxaban enabled patients to undergo the procedure more expeditiously, Dr. Riccardo Cappato noted in presenting the X-VeRT findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, patients in the early-cardioversion arm of the trial safely underwent the procedure as early as 4 hours after taking their first 20-mg dose of rivaroxaban.

Moreover, patients in the delayed-conversion study arm, which required at least 3 consecutive weeks of effective oral anticoagulation preprocedurally, underwent cardioversion an average of 8 days earlier if randomized to rivaroxaban rather than to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. That’s because many warfarin-treated patients couldn’t maintain their international normalized ratio (INR) within the target range of 2.0-3.0 for 3 straight weeks, explained Dr. Cappato, professor of electrophysiology and chief of the arrhythmia and electrophysiology center at the University of Milan’s San Donato Polyclinic Hospital.

X-VeRT included 1,504 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) at 141 centers in 16 countries. All were scheduled for elective cardioversion. They were randomized 2:1 to rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily or to warfarin at a dose adjusted to maintain an INR of 2.0-3.0.

Of those patients, 872 were assigned to an early-cardioversion strategy. Their cardioversion took place after 1-5 days on study medication, provided transesophageal echocardiography had ruled out a left atrial thrombus or they were already on chronic warfarin with their last three INRs in the target range. The other 632 patients were cardioverted using a delayed strategy in which they had to be on study medication for 3-8 weeks before the procedure.

The primary efficacy outcome in X-VeRT was the composite rate of stroke, TIA, peripheral embolism, MI, and cardiovascular death. The incidence was 0.51% in the rivaroxaban group and not statistically different at 1.02% in the warfarin group. The primary safety outcome – major bleeding – occurred in 0.6% of rivaroxaban-treated patients and 0.8% on warfarin.

The median time to cardioversion in the early-cardioversion strategy arm was similar regardless of which drug was used. Of note, however, in the delayed-strategy group, the median time to cardioversion was 22 days in patients on rivaroxaban, compared with 30 days with warfarin.

Of patients in the delayed-strategy group, 77% of those on rivaroxaban were cardioverted as scheduled, compared with 36% on warfarin. Only one patient in the rivaroxaban group was unable to undergo cardioversion before the 8-week cutoff because of inadequate anticoagulation as defined by less than 80% compliance in pill taking; in contrast, 95 warfarin-treated patients in the delayed-strategy group weren’t cardioverted because they missed the 8-week cutoff because of problematic INRs.

In an interview, ESC spokesman Dr. Jurrien Ten Berg predicted X-VeRT will be practice changing. He believes that on the basis of these study results, many physicians will view elective cardioversion as an excellent time to switch patients from warfarin, with all its inherent problems, to rivaroxaban, especially if they qualify for early cardioversion.

"I think this will absolutely change our policy. Here we’re talking about a once-daily pill that makes it possible to do a cardioversion early, and I think that’s a major advantage. If you delay the cardioversion, anything can happen. We know the vitamin K antagonists are unreliable, especially in the first weeks, when even if the INR is fine you don’t really know if the patient is well anticoagulated. For me, the totally of evidence, including the retrospective analyses of the large atrial fibrillation stroke prevention trials, is enough now to use a NOAC for several days and then do an early cardioversion," said Dr. Ten Berg, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

Discussant Dr. Christoph Bode called X-VeRT "a landmark trial" and "brilliant work."

"This should be included in the next update of the guidelines," said Dr. Bode, professor and chair of internal medicine and cardiology at the University of Freiburg, Germany.

However, Dr. Steven Nissen took a more skeptical, albeit clearly a minority, view.

"I think this study shows neither safety nor efficacy for this regimen. There were just a handful of events in both groups, too few to draw any conclusions. I don’t think the guidelines should be changed. I think the proper interpretation of the study is that it’s inconclusive," said Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Dr. Cappato noted in response that he’d stated at the outset that X-VeRT, even at more than 1,500 patients, was underpowered statistically. Event rates in well-anticoagulated patients undergoing cardioversion are so low that a study to establish noninferiority for rivaroxaban would require 25,000-30,000 participants, which is not going to happen.

"Many physicians are already switching to NOACs [novel oral anticoagulants] for cardioversion despite the absence of good evidence. We thought bringing forward this solid, methodologically sound information from X-VeRT would provide more consistent support for those who are doing this or considering it," the cardiologist said.

Simultaneous with his presentation in Barcelona, the X-VeRT (Explore the Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Oral Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Scheduled for Cardioversion) study was published online (Eur. Heart J. 2014 [doi:10.1093/eurheart/ehu367]).

Dr. Cappato reported receiving investigator fees from and serving as a consultant to and on speakers bureaus for numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Bayer HealthCare, which sponsored X-VeRT. Dr. Bode has received honoraria from Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Ten Berg and Dr. Nissen reported having no financial conflicts.

BARCELONA – Rivaroxaban appears to be a safe and effective alternative to warfarin in patients with atrial fibrillation undergoing elective cardioversion, according to the findings of the first-ever prospective, randomized trial of a novel oral anticoagulant for this application.

Additionally, the X-VeRT trial showed that rivaroxaban (Xarelto) may offer an attractive, highly practical advantage over warfarin, the current guideline-recommended standard of care for cardioversion: Namely, rivaroxaban enabled patients to undergo the procedure more expeditiously, Dr. Riccardo Cappato noted in presenting the X-VeRT findings at the annual congress of the European Society of Cardiology.

Indeed, patients in the early-cardioversion arm of the trial safely underwent the procedure as early as 4 hours after taking their first 20-mg dose of rivaroxaban.

Moreover, patients in the delayed-conversion study arm, which required at least 3 consecutive weeks of effective oral anticoagulation preprocedurally, underwent cardioversion an average of 8 days earlier if randomized to rivaroxaban rather than to warfarin or another vitamin K antagonist. That’s because many warfarin-treated patients couldn’t maintain their international normalized ratio (INR) within the target range of 2.0-3.0 for 3 straight weeks, explained Dr. Cappato, professor of electrophysiology and chief of the arrhythmia and electrophysiology center at the University of Milan’s San Donato Polyclinic Hospital.

X-VeRT included 1,504 patients with nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (AF) at 141 centers in 16 countries. All were scheduled for elective cardioversion. They were randomized 2:1 to rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily or to warfarin at a dose adjusted to maintain an INR of 2.0-3.0.

Of those patients, 872 were assigned to an early-cardioversion strategy. Their cardioversion took place after 1-5 days on study medication, provided transesophageal echocardiography had ruled out a left atrial thrombus or they were already on chronic warfarin with their last three INRs in the target range. The other 632 patients were cardioverted using a delayed strategy in which they had to be on study medication for 3-8 weeks before the procedure.

The primary efficacy outcome in X-VeRT was the composite rate of stroke, TIA, peripheral embolism, MI, and cardiovascular death. The incidence was 0.51% in the rivaroxaban group and not statistically different at 1.02% in the warfarin group. The primary safety outcome – major bleeding – occurred in 0.6% of rivaroxaban-treated patients and 0.8% on warfarin.

The median time to cardioversion in the early-cardioversion strategy arm was similar regardless of which drug was used. Of note, however, in the delayed-strategy group, the median time to cardioversion was 22 days in patients on rivaroxaban, compared with 30 days with warfarin.

Of patients in the delayed-strategy group, 77% of those on rivaroxaban were cardioverted as scheduled, compared with 36% on warfarin. Only one patient in the rivaroxaban group was unable to undergo cardioversion before the 8-week cutoff because of inadequate anticoagulation as defined by less than 80% compliance in pill taking; in contrast, 95 warfarin-treated patients in the delayed-strategy group weren’t cardioverted because they missed the 8-week cutoff because of problematic INRs.

In an interview, ESC spokesman Dr. Jurrien Ten Berg predicted X-VeRT will be practice changing. He believes that on the basis of these study results, many physicians will view elective cardioversion as an excellent time to switch patients from warfarin, with all its inherent problems, to rivaroxaban, especially if they qualify for early cardioversion.

"I think this will absolutely change our policy. Here we’re talking about a once-daily pill that makes it possible to do a cardioversion early, and I think that’s a major advantage. If you delay the cardioversion, anything can happen. We know the vitamin K antagonists are unreliable, especially in the first weeks, when even if the INR is fine you don’t really know if the patient is well anticoagulated. For me, the totally of evidence, including the retrospective analyses of the large atrial fibrillation stroke prevention trials, is enough now to use a NOAC for several days and then do an early cardioversion," said Dr. Ten Berg, a cardiologist at St. Antonius Hospital, Nieuwegein, the Netherlands.

Discussant Dr. Christoph Bode called X-VeRT "a landmark trial" and "brilliant work."

"This should be included in the next update of the guidelines," said Dr. Bode, professor and chair of internal medicine and cardiology at the University of Freiburg, Germany.

However, Dr. Steven Nissen took a more skeptical, albeit clearly a minority, view.

"I think this study shows neither safety nor efficacy for this regimen. There were just a handful of events in both groups, too few to draw any conclusions. I don’t think the guidelines should be changed. I think the proper interpretation of the study is that it’s inconclusive," said Dr. Nissen, chair of the department of cardiovascular medicine at the Cleveland Clinic.

Dr. Cappato noted in response that he’d stated at the outset that X-VeRT, even at more than 1,500 patients, was underpowered statistically. Event rates in well-anticoagulated patients undergoing cardioversion are so low that a study to establish noninferiority for rivaroxaban would require 25,000-30,000 participants, which is not going to happen.

"Many physicians are already switching to NOACs [novel oral anticoagulants] for cardioversion despite the absence of good evidence. We thought bringing forward this solid, methodologically sound information from X-VeRT would provide more consistent support for those who are doing this or considering it," the cardiologist said.

Simultaneous with his presentation in Barcelona, the X-VeRT (Explore the Efficacy and Safety of Once-Daily Oral Rivaroxaban for the Prevention of Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation Scheduled for Cardioversion) study was published online (Eur. Heart J. 2014 [doi:10.1093/eurheart/ehu367]).

Dr. Cappato reported receiving investigator fees from and serving as a consultant to and on speakers bureaus for numerous pharmaceutical companies, including Bayer HealthCare, which sponsored X-VeRT. Dr. Bode has received honoraria from Bayer HealthCare. Dr. Ten Berg and Dr. Nissen reported having no financial conflicts.

AT THE ESC CONGRESS 2014

Key clinical point: Patients in atrial fibrillation were able to safely undergo cardioversion as early as 4 hours after taking their first 20-mg dose of oral rivaroxaban.

Major finding: Patients with AF assigned to rivaroxaban in conjunction with cardioversion had a 0.51% rate of major cardiovascular events, similar to the 1.02% rate in patients on warfarin or other vitamin K antagonists. These rates weren’t statistically different; nor were the major bleeding rates in the two groups.

Data source: X-VeRT was a randomized, prospective, open-label, phase IIIb clinical trial involving 1,504 patients at 141 centers in 16 countries.

Disclosures: The X-VeRT trial was sponsored by Bayer HealthCare. The presenter serves as a consultant to and on speakers bureaus for Bayer and other pharmaceutical companies.

Extending Therapy for Breast Cancer

Laronna Colbert, MD, discusses how recent breast cancer studies "have the potential to change current practice standards" for breast cancer.

"This is really a dynamic field of study," Colbert said during her 2013 AVAHO Meeting presentation. "Hopefully, we can continue to make advancements for these patients."

Laronna Colbert, MD, discusses how recent breast cancer studies "have the potential to change current practice standards" for breast cancer.

"This is really a dynamic field of study," Colbert said during her 2013 AVAHO Meeting presentation. "Hopefully, we can continue to make advancements for these patients."

Laronna Colbert, MD, discusses how recent breast cancer studies "have the potential to change current practice standards" for breast cancer.

"This is really a dynamic field of study," Colbert said during her 2013 AVAHO Meeting presentation. "Hopefully, we can continue to make advancements for these patients."

Treating Metastatic Lung Cancer

Rafael Santana-Davila, MD, discusses how understanding the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) will help physicians better serve the veteran population.

"NSCLC is the second most common cancer—second to prostate cancer—in the VA and, more importantly, the most common cause of cancer death in our veterans." Santana-Davila said during his 2013 AVAHO meeting presentation. "The main goal of the treatment is to improve quality of life and extend survival as much as possible."

Rafael Santana-Davila, MD, discusses how understanding the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) will help physicians better serve the veteran population.

"NSCLC is the second most common cancer—second to prostate cancer—in the VA and, more importantly, the most common cause of cancer death in our veterans." Santana-Davila said during his 2013 AVAHO meeting presentation. "The main goal of the treatment is to improve quality of life and extend survival as much as possible."

Rafael Santana-Davila, MD, discusses how understanding the treatment of non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) will help physicians better serve the veteran population.

"NSCLC is the second most common cancer—second to prostate cancer—in the VA and, more importantly, the most common cause of cancer death in our veterans." Santana-Davila said during his 2013 AVAHO meeting presentation. "The main goal of the treatment is to improve quality of life and extend survival as much as possible."

Calcium – Making deposits for a healthy adulthood

Likely, one of the most important roles of a pediatrician is to maximize health in childhood and positively impact health in adulthood. Bone density is one of the few things that can be maximized in adolescence. By maximizing bone density, we can directly slow and reduce the osteopenia that occurs later in life and the osteoporosis that 10 million Americans struggle with annually.

The physiology of calcium absorption changes throughout life. In early adolescence, the absorption is greater than the elimination. Between 30 and 50 years of age, absorption and elimination are about equal, but as we enter into the sixth decade of life, there is significant bone loss. Studies have shown that bone density is maximized by age 30 years, and little change is made later in life despite supplementation (Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;47:617-22). The greatest amount of bone loss occurs after the age of 65 years, and fractures after this age are predominantly at cortical sites.

Consumption of the appropriate amounts of calcium can be difficult given the inadequacies of most adolescents’ diet. The recommended daily intake is 1,200-1,500 mg of elemental calcium. But, absorption of calcium is quite variable and is dependent on other factors to be in place for it to be maximized.

The two most common form of calcium are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate malate. Calcium carbonate requires a higher pH of the stomach, and therefore needs to be taken with food. Calcium carbonate is more cost effective but is also associated with more side effects such as gas and bloating. Calcium citrate malate is found in many juices that are fortified with calcium, can be taken with or without food, is better absorbed with chronic conditions, and is thought to be protective against stone formation (J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1996;15:313-6; Adv. Food. Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346).

Common sources of calcium include milk, yogurt, cheese, Chinese cabbage, kale, broccoli, and spinach. Appropriate levels of vitamin D are important to maximize the absorption of calcium, and recent studies have shown that 40% of adolescents are deficient in vitamin D (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004;158:531-7; Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162:513-9). Many other adolescents are lactose intolerant or have a milk protein allergy, which also limit the calcium sources. Soymilk has similar levels of calcium, compared with whole milk. Almond-coconut milk has double the amount of calcium, compared with whole milk, so it is a great substitute for those who are lactose intolerant.

Oxalic acids are found in food such as spinach, collard greens, and sweet potatoes, all of which are rich in calcium, but the oxalic acid reduces the absorption of the calcium. Consumption of large amounts of tea and coffee also can reduce calcium absorption, so despite consuming appropriate amounts of calcium, limited amounts become bioavailable.

If using calcium supplements, ingesting less than or equal to 500 mg is better than taking 1,000 mg at once because it is better absorbed (Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346). Orange juice, apple juice, and cereals are fortified with calcium so these also are great sources that usually are accepted by adolescents.

Calcium is a critical dietary supplement that is needed for strong bones, metabolic functions, nerve transmission, and vascular contraction and vasodilation. Long-term deficiency will result in disease, and fragility of the bones. Early supplementation and calcium rich diets can ensure maximum bone development, but if parents are not educated on the appropriate delivery, this opportunity could be missed.

An excellent resource is the National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements website. This site gives a wealth of information for sources and consumption of calcium. Another excellent resource for parents to use to guide them to make healthier choices is the U.S. Department of Agriculture site, www.choosemyplate.gov. Parents are looking for quick simple ways to maximize their children’s diet and ensure they are getting everything they need to be healthy adults. Becoming familiar with the basics will allow you to give informed advice that will significantly affect their children’s future.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

Likely, one of the most important roles of a pediatrician is to maximize health in childhood and positively impact health in adulthood. Bone density is one of the few things that can be maximized in adolescence. By maximizing bone density, we can directly slow and reduce the osteopenia that occurs later in life and the osteoporosis that 10 million Americans struggle with annually.

The physiology of calcium absorption changes throughout life. In early adolescence, the absorption is greater than the elimination. Between 30 and 50 years of age, absorption and elimination are about equal, but as we enter into the sixth decade of life, there is significant bone loss. Studies have shown that bone density is maximized by age 30 years, and little change is made later in life despite supplementation (Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;47:617-22). The greatest amount of bone loss occurs after the age of 65 years, and fractures after this age are predominantly at cortical sites.

Consumption of the appropriate amounts of calcium can be difficult given the inadequacies of most adolescents’ diet. The recommended daily intake is 1,200-1,500 mg of elemental calcium. But, absorption of calcium is quite variable and is dependent on other factors to be in place for it to be maximized.

The two most common form of calcium are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate malate. Calcium carbonate requires a higher pH of the stomach, and therefore needs to be taken with food. Calcium carbonate is more cost effective but is also associated with more side effects such as gas and bloating. Calcium citrate malate is found in many juices that are fortified with calcium, can be taken with or without food, is better absorbed with chronic conditions, and is thought to be protective against stone formation (J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1996;15:313-6; Adv. Food. Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346).

Common sources of calcium include milk, yogurt, cheese, Chinese cabbage, kale, broccoli, and spinach. Appropriate levels of vitamin D are important to maximize the absorption of calcium, and recent studies have shown that 40% of adolescents are deficient in vitamin D (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004;158:531-7; Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162:513-9). Many other adolescents are lactose intolerant or have a milk protein allergy, which also limit the calcium sources. Soymilk has similar levels of calcium, compared with whole milk. Almond-coconut milk has double the amount of calcium, compared with whole milk, so it is a great substitute for those who are lactose intolerant.

Oxalic acids are found in food such as spinach, collard greens, and sweet potatoes, all of which are rich in calcium, but the oxalic acid reduces the absorption of the calcium. Consumption of large amounts of tea and coffee also can reduce calcium absorption, so despite consuming appropriate amounts of calcium, limited amounts become bioavailable.

If using calcium supplements, ingesting less than or equal to 500 mg is better than taking 1,000 mg at once because it is better absorbed (Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346). Orange juice, apple juice, and cereals are fortified with calcium so these also are great sources that usually are accepted by adolescents.

Calcium is a critical dietary supplement that is needed for strong bones, metabolic functions, nerve transmission, and vascular contraction and vasodilation. Long-term deficiency will result in disease, and fragility of the bones. Early supplementation and calcium rich diets can ensure maximum bone development, but if parents are not educated on the appropriate delivery, this opportunity could be missed.

An excellent resource is the National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements website. This site gives a wealth of information for sources and consumption of calcium. Another excellent resource for parents to use to guide them to make healthier choices is the U.S. Department of Agriculture site, www.choosemyplate.gov. Parents are looking for quick simple ways to maximize their children’s diet and ensure they are getting everything they need to be healthy adults. Becoming familiar with the basics will allow you to give informed advice that will significantly affect their children’s future.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

Likely, one of the most important roles of a pediatrician is to maximize health in childhood and positively impact health in adulthood. Bone density is one of the few things that can be maximized in adolescence. By maximizing bone density, we can directly slow and reduce the osteopenia that occurs later in life and the osteoporosis that 10 million Americans struggle with annually.

The physiology of calcium absorption changes throughout life. In early adolescence, the absorption is greater than the elimination. Between 30 and 50 years of age, absorption and elimination are about equal, but as we enter into the sixth decade of life, there is significant bone loss. Studies have shown that bone density is maximized by age 30 years, and little change is made later in life despite supplementation (Eur. J. Clin. Nutr. 1993;47:617-22). The greatest amount of bone loss occurs after the age of 65 years, and fractures after this age are predominantly at cortical sites.

Consumption of the appropriate amounts of calcium can be difficult given the inadequacies of most adolescents’ diet. The recommended daily intake is 1,200-1,500 mg of elemental calcium. But, absorption of calcium is quite variable and is dependent on other factors to be in place for it to be maximized.

The two most common form of calcium are calcium carbonate and calcium citrate malate. Calcium carbonate requires a higher pH of the stomach, and therefore needs to be taken with food. Calcium carbonate is more cost effective but is also associated with more side effects such as gas and bloating. Calcium citrate malate is found in many juices that are fortified with calcium, can be taken with or without food, is better absorbed with chronic conditions, and is thought to be protective against stone formation (J. Am. Coll. Nutr. 1996;15:313-6; Adv. Food. Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346).

Common sources of calcium include milk, yogurt, cheese, Chinese cabbage, kale, broccoli, and spinach. Appropriate levels of vitamin D are important to maximize the absorption of calcium, and recent studies have shown that 40% of adolescents are deficient in vitamin D (Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2004;158:531-7; Arch. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2008;162:513-9). Many other adolescents are lactose intolerant or have a milk protein allergy, which also limit the calcium sources. Soymilk has similar levels of calcium, compared with whole milk. Almond-coconut milk has double the amount of calcium, compared with whole milk, so it is a great substitute for those who are lactose intolerant.

Oxalic acids are found in food such as spinach, collard greens, and sweet potatoes, all of which are rich in calcium, but the oxalic acid reduces the absorption of the calcium. Consumption of large amounts of tea and coffee also can reduce calcium absorption, so despite consuming appropriate amounts of calcium, limited amounts become bioavailable.

If using calcium supplements, ingesting less than or equal to 500 mg is better than taking 1,000 mg at once because it is better absorbed (Adv. Food Nutr. Res. 2008;54:219-346). Orange juice, apple juice, and cereals are fortified with calcium so these also are great sources that usually are accepted by adolescents.

Calcium is a critical dietary supplement that is needed for strong bones, metabolic functions, nerve transmission, and vascular contraction and vasodilation. Long-term deficiency will result in disease, and fragility of the bones. Early supplementation and calcium rich diets can ensure maximum bone development, but if parents are not educated on the appropriate delivery, this opportunity could be missed.

An excellent resource is the National Institutes of Health, Office of Dietary Supplements website. This site gives a wealth of information for sources and consumption of calcium. Another excellent resource for parents to use to guide them to make healthier choices is the U.S. Department of Agriculture site, www.choosemyplate.gov. Parents are looking for quick simple ways to maximize their children’s diet and ensure they are getting everything they need to be healthy adults. Becoming familiar with the basics will allow you to give informed advice that will significantly affect their children’s future.

Dr. Pearce is a pediatrician in Frankfort, Ill. E-mail her at [email protected].

Preclinical results support blood transfusions containing fibronectin

Credit: UAB Hospital

The protein fibronectin is instrumental in stopping bleeding and preventing life-threatening blood clots, according to preclinical research published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Experiments in mice revealed that plasma fibronectin (pFn) can switch from supporting hemostasis to inhibiting thrombosis.

The researchers said these findings suggest transfusions containing pFn may control bleeding in humans, particularly in association with anticoagulant therapy.

“Most treatments that help the body stop bleeding can actually cause blood clots, and many treatments to prevent excessive blood clots increase [the] risk of bleeding out,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

“But when given to mice after an injury or to mice treated with blood thinners—which frequently lead to bleeding complications—fibronectin seems to offer a win-win solution.”

Dr Ni and his colleagues began this research by generating mice deficient in both fibrinogen (Fg) and von Willebrand factor (VWF), as well as mice deficient in both VWF and pFn. They then compared these mice to untreated wild-type mice and anticoagulant-treated wild-type mice.

The team discovered that pFn is vital for controlling bleeding in the context of Fg deficiency and supports hemostasis in the context of VWF deficiency. pFn deposition occurred before platelet accumulation (the first wave of hemostasis) in both wild-type and deficient mice.

However, pFn switched its function with regard to platelet aggregation based on the presence or absence of fibrin. pFn inhibited platelet aggregation when fibrin was absent and promoted aggregation when linked with fibrin.

The researchers found that pFn can control the diameter of fibrin fibers, increase the mechanical strength of a blood clot, and be actively involved in thrombosis.

The team said these results provide a solution for the controversy surrounding pFn’s function in hemostasis and establish pFn as a unique regulatory factor in thrombosis. The findings also suggest transfusions containing pFn may prove particularly effective in controlling bleeding.

“Fibrinogen has been shown to help the body stop bleeding, but our research indicates that less-refined blood products that include fibronectin and fibrinogen may help stop bleeding even more effectively,” Dr Ni said. “And, as an added bonus, fibronectin likely also reduces the risk of life-threatening blood clots from forming.”

“There is a lot of work to be done, but we might find that the less expensive and less processed form of donor blood may be more effective for transfusions. We’ve shown that fibronectin might play a role in improving results from transfusions and should not be discarded during blood product processing. It may be also an important protein in transfusions for stopping bleeding, particularly for patients who receive blood thinners during surgeries.” ![]()

Credit: UAB Hospital

The protein fibronectin is instrumental in stopping bleeding and preventing life-threatening blood clots, according to preclinical research published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Experiments in mice revealed that plasma fibronectin (pFn) can switch from supporting hemostasis to inhibiting thrombosis.

The researchers said these findings suggest transfusions containing pFn may control bleeding in humans, particularly in association with anticoagulant therapy.

“Most treatments that help the body stop bleeding can actually cause blood clots, and many treatments to prevent excessive blood clots increase [the] risk of bleeding out,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

“But when given to mice after an injury or to mice treated with blood thinners—which frequently lead to bleeding complications—fibronectin seems to offer a win-win solution.”

Dr Ni and his colleagues began this research by generating mice deficient in both fibrinogen (Fg) and von Willebrand factor (VWF), as well as mice deficient in both VWF and pFn. They then compared these mice to untreated wild-type mice and anticoagulant-treated wild-type mice.

The team discovered that pFn is vital for controlling bleeding in the context of Fg deficiency and supports hemostasis in the context of VWF deficiency. pFn deposition occurred before platelet accumulation (the first wave of hemostasis) in both wild-type and deficient mice.

However, pFn switched its function with regard to platelet aggregation based on the presence or absence of fibrin. pFn inhibited platelet aggregation when fibrin was absent and promoted aggregation when linked with fibrin.

The researchers found that pFn can control the diameter of fibrin fibers, increase the mechanical strength of a blood clot, and be actively involved in thrombosis.

The team said these results provide a solution for the controversy surrounding pFn’s function in hemostasis and establish pFn as a unique regulatory factor in thrombosis. The findings also suggest transfusions containing pFn may prove particularly effective in controlling bleeding.

“Fibrinogen has been shown to help the body stop bleeding, but our research indicates that less-refined blood products that include fibronectin and fibrinogen may help stop bleeding even more effectively,” Dr Ni said. “And, as an added bonus, fibronectin likely also reduces the risk of life-threatening blood clots from forming.”

“There is a lot of work to be done, but we might find that the less expensive and less processed form of donor blood may be more effective for transfusions. We’ve shown that fibronectin might play a role in improving results from transfusions and should not be discarded during blood product processing. It may be also an important protein in transfusions for stopping bleeding, particularly for patients who receive blood thinners during surgeries.” ![]()

Credit: UAB Hospital

The protein fibronectin is instrumental in stopping bleeding and preventing life-threatening blood clots, according to preclinical research published in The Journal of Clinical Investigation.

Experiments in mice revealed that plasma fibronectin (pFn) can switch from supporting hemostasis to inhibiting thrombosis.

The researchers said these findings suggest transfusions containing pFn may control bleeding in humans, particularly in association with anticoagulant therapy.

“Most treatments that help the body stop bleeding can actually cause blood clots, and many treatments to prevent excessive blood clots increase [the] risk of bleeding out,” said study author Heyu Ni, MD, of St Michael’s Hospital in Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

“But when given to mice after an injury or to mice treated with blood thinners—which frequently lead to bleeding complications—fibronectin seems to offer a win-win solution.”

Dr Ni and his colleagues began this research by generating mice deficient in both fibrinogen (Fg) and von Willebrand factor (VWF), as well as mice deficient in both VWF and pFn. They then compared these mice to untreated wild-type mice and anticoagulant-treated wild-type mice.

The team discovered that pFn is vital for controlling bleeding in the context of Fg deficiency and supports hemostasis in the context of VWF deficiency. pFn deposition occurred before platelet accumulation (the first wave of hemostasis) in both wild-type and deficient mice.

However, pFn switched its function with regard to platelet aggregation based on the presence or absence of fibrin. pFn inhibited platelet aggregation when fibrin was absent and promoted aggregation when linked with fibrin.

The researchers found that pFn can control the diameter of fibrin fibers, increase the mechanical strength of a blood clot, and be actively involved in thrombosis.

The team said these results provide a solution for the controversy surrounding pFn’s function in hemostasis and establish pFn as a unique regulatory factor in thrombosis. The findings also suggest transfusions containing pFn may prove particularly effective in controlling bleeding.

“Fibrinogen has been shown to help the body stop bleeding, but our research indicates that less-refined blood products that include fibronectin and fibrinogen may help stop bleeding even more effectively,” Dr Ni said. “And, as an added bonus, fibronectin likely also reduces the risk of life-threatening blood clots from forming.”

“There is a lot of work to be done, but we might find that the less expensive and less processed form of donor blood may be more effective for transfusions. We’ve shown that fibronectin might play a role in improving results from transfusions and should not be discarded during blood product processing. It may be also an important protein in transfusions for stopping bleeding, particularly for patients who receive blood thinners during surgeries.” ![]()

Many new additions in ESC’s latest guidelines for PE

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has published new guidelines for managing patients with pulmonary embolism (PE).

The guidelines now include recommendations for all new oral anticoagulants, a risk-stratification algorithm, new advice on managing PE in specific patient populations, and age-specific D-dimer cutoffs, among other additions.

The guidelines were presented at the ESC Congress 2014 and published in the European Heart Journal and on the ESC website.

Previous ESC Guidelines on acute PE were published in 2000 and 2008.

“These are the first major international guidelines with a complete set of recommendations on the use of new oral anticoagulants in VTE [venous thromboembolism],” said guidelines author Stavros Konstantinides, MD, PhD, of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany.

“For each drug, we provide detailed recommendations on how and when to use it, and whether it should be first-line treatment or an alternative to standard treatment.”

Managing specific patients

For the first time, the guidelines include formal recommendations for managing PE in pregnancy and in cancer patients.

The guidelines also highlight recently identified risk factors for VTE, including in vitro fertilization, which increases the risk of VTE in early pregnancy.

And the guidelines include a new chapter on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Risk stratification

Another first with the new guidelines is the inclusion of an algorithm for risk stratification. It incorporates all available tools and provides recommendations for managing patients according to risk.

“Patients with PE or suspected PE who are in shock are at high risk, but at least 95% of patients are at intermediate or low risk, and defining how to manage them has not been clear,” Dr Konstantinides said.

“Previously, we used echocardiography and/or a CT scan to evaluate the right ventricle but did not combine this information with clinical data. These topics have advanced in the past 6 years, and now we can integrate clinical scores of severity, imaging with echo and CT, and biomarkers to define levels of risk.”

“And, more importantly, we now have solid evidence to give recommendations on rescue rather than primary thrombolysis in patients at intermediate risk of early adverse outcome. We are also now able to recommend how to identify low-risk patients [who] may be considered for early discharge despite a confirmed PE episode.”

D-dimer cutoffs

Another new addition to the guidelines is age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs, which have been introduced to identify patients of all ages who do not require anticoagulation.

Until now, anticoagulation could be withheld in patients with D-dimer levels less than 500 µg/L, but D-dimer rises naturally with age.

The guidelines reference evidence suggesting that, for patients older than 50, the cutoff may now be their age times 10. For example, in a 65-year-old, the cutoff would be 650 µg/L.

“These guidelines provide the most comprehensive recommendations ever for the diagnosis and treatment of PE,” Dr Konstantinides concluded. “Clinicians can confidently risk-stratify their patients with suspected PE and provide appropriate treatment including the new oral anticoagulants.” ![]()

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has published new guidelines for managing patients with pulmonary embolism (PE).

The guidelines now include recommendations for all new oral anticoagulants, a risk-stratification algorithm, new advice on managing PE in specific patient populations, and age-specific D-dimer cutoffs, among other additions.

The guidelines were presented at the ESC Congress 2014 and published in the European Heart Journal and on the ESC website.

Previous ESC Guidelines on acute PE were published in 2000 and 2008.

“These are the first major international guidelines with a complete set of recommendations on the use of new oral anticoagulants in VTE [venous thromboembolism],” said guidelines author Stavros Konstantinides, MD, PhD, of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany.

“For each drug, we provide detailed recommendations on how and when to use it, and whether it should be first-line treatment or an alternative to standard treatment.”

Managing specific patients

For the first time, the guidelines include formal recommendations for managing PE in pregnancy and in cancer patients.

The guidelines also highlight recently identified risk factors for VTE, including in vitro fertilization, which increases the risk of VTE in early pregnancy.

And the guidelines include a new chapter on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Risk stratification

Another first with the new guidelines is the inclusion of an algorithm for risk stratification. It incorporates all available tools and provides recommendations for managing patients according to risk.

“Patients with PE or suspected PE who are in shock are at high risk, but at least 95% of patients are at intermediate or low risk, and defining how to manage them has not been clear,” Dr Konstantinides said.

“Previously, we used echocardiography and/or a CT scan to evaluate the right ventricle but did not combine this information with clinical data. These topics have advanced in the past 6 years, and now we can integrate clinical scores of severity, imaging with echo and CT, and biomarkers to define levels of risk.”

“And, more importantly, we now have solid evidence to give recommendations on rescue rather than primary thrombolysis in patients at intermediate risk of early adverse outcome. We are also now able to recommend how to identify low-risk patients [who] may be considered for early discharge despite a confirmed PE episode.”

D-dimer cutoffs

Another new addition to the guidelines is age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs, which have been introduced to identify patients of all ages who do not require anticoagulation.

Until now, anticoagulation could be withheld in patients with D-dimer levels less than 500 µg/L, but D-dimer rises naturally with age.

The guidelines reference evidence suggesting that, for patients older than 50, the cutoff may now be their age times 10. For example, in a 65-year-old, the cutoff would be 650 µg/L.

“These guidelines provide the most comprehensive recommendations ever for the diagnosis and treatment of PE,” Dr Konstantinides concluded. “Clinicians can confidently risk-stratify their patients with suspected PE and provide appropriate treatment including the new oral anticoagulants.” ![]()

The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) has published new guidelines for managing patients with pulmonary embolism (PE).

The guidelines now include recommendations for all new oral anticoagulants, a risk-stratification algorithm, new advice on managing PE in specific patient populations, and age-specific D-dimer cutoffs, among other additions.

The guidelines were presented at the ESC Congress 2014 and published in the European Heart Journal and on the ESC website.

Previous ESC Guidelines on acute PE were published in 2000 and 2008.

“These are the first major international guidelines with a complete set of recommendations on the use of new oral anticoagulants in VTE [venous thromboembolism],” said guidelines author Stavros Konstantinides, MD, PhD, of the Johannes Gutenberg University Mainz in Germany.

“For each drug, we provide detailed recommendations on how and when to use it, and whether it should be first-line treatment or an alternative to standard treatment.”

Managing specific patients

For the first time, the guidelines include formal recommendations for managing PE in pregnancy and in cancer patients.

The guidelines also highlight recently identified risk factors for VTE, including in vitro fertilization, which increases the risk of VTE in early pregnancy.

And the guidelines include a new chapter on the diagnosis and treatment of chronic thromboembolic pulmonary hypertension.

Risk stratification

Another first with the new guidelines is the inclusion of an algorithm for risk stratification. It incorporates all available tools and provides recommendations for managing patients according to risk.

“Patients with PE or suspected PE who are in shock are at high risk, but at least 95% of patients are at intermediate or low risk, and defining how to manage them has not been clear,” Dr Konstantinides said.

“Previously, we used echocardiography and/or a CT scan to evaluate the right ventricle but did not combine this information with clinical data. These topics have advanced in the past 6 years, and now we can integrate clinical scores of severity, imaging with echo and CT, and biomarkers to define levels of risk.”

“And, more importantly, we now have solid evidence to give recommendations on rescue rather than primary thrombolysis in patients at intermediate risk of early adverse outcome. We are also now able to recommend how to identify low-risk patients [who] may be considered for early discharge despite a confirmed PE episode.”

D-dimer cutoffs

Another new addition to the guidelines is age-adjusted D-dimer cutoffs, which have been introduced to identify patients of all ages who do not require anticoagulation.

Until now, anticoagulation could be withheld in patients with D-dimer levels less than 500 µg/L, but D-dimer rises naturally with age.

The guidelines reference evidence suggesting that, for patients older than 50, the cutoff may now be their age times 10. For example, in a 65-year-old, the cutoff would be 650 µg/L.

“These guidelines provide the most comprehensive recommendations ever for the diagnosis and treatment of PE,” Dr Konstantinides concluded. “Clinicians can confidently risk-stratify their patients with suspected PE and provide appropriate treatment including the new oral anticoagulants.” ![]()

Fusion proteins enable expansion of HSPCs

Credit: Chad McNeeley

A new technique has allowed researchers to expand hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from multiple sources.

The team developed fusion proteins and introduced them to HSPCs ex vivo.

This approach expanded cell populations whether HSPCs were derived from cord blood, bone marrow, or peripheral blood.

The potential clinical applications for this work range from immunodeficiency disorders to hematologic and other malignancies, according to the researchers.

Yosef Refaeli, PhD, of Taiga Biotechnologies, Inc. in Aurora, Colorado, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

The team first cultured human or murine HSPCs with a pair of fusion proteins—the protein transduction domain of the HIV-1 transactivation protein (Tat) and either the Open Reading Frame for human MYC or a truncated form of human Bcl-2 that was deleted for the unstructured loop domain.

With this technique, the researchers were able to elicit an 87-fold expansion of HSPCs from mouse bone marrow, a 16.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human cord blood, a 13.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human peripheral blood cells mobilized by G-CSF, and a 10-fold expansion of HSPCs from human bone marrow.

The team then tested the biological function of the expanded cells, and they found the cells gave rise to BFU-E, CFU-M, CFU-G, and CFU-GM colonies in vitro.

When transplanted into irradiated mice, the expanded cells gave rise to mature hematopoietic populations and a self-renewing cell population that was able to support hematopoiesis upon serial transplantation.

The researchers said these results suggest their technique may be an attractive approach to expand human HSPCs ex vivo for clinical use.

The team’s goal now is to move the technology from the lab into clinical trials. Taiga Biotechnologies is in the process of setting up clinical trials testing this approach. ![]()

Credit: Chad McNeeley

A new technique has allowed researchers to expand hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from multiple sources.

The team developed fusion proteins and introduced them to HSPCs ex vivo.

This approach expanded cell populations whether HSPCs were derived from cord blood, bone marrow, or peripheral blood.

The potential clinical applications for this work range from immunodeficiency disorders to hematologic and other malignancies, according to the researchers.

Yosef Refaeli, PhD, of Taiga Biotechnologies, Inc. in Aurora, Colorado, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

The team first cultured human or murine HSPCs with a pair of fusion proteins—the protein transduction domain of the HIV-1 transactivation protein (Tat) and either the Open Reading Frame for human MYC or a truncated form of human Bcl-2 that was deleted for the unstructured loop domain.

With this technique, the researchers were able to elicit an 87-fold expansion of HSPCs from mouse bone marrow, a 16.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human cord blood, a 13.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human peripheral blood cells mobilized by G-CSF, and a 10-fold expansion of HSPCs from human bone marrow.

The team then tested the biological function of the expanded cells, and they found the cells gave rise to BFU-E, CFU-M, CFU-G, and CFU-GM colonies in vitro.

When transplanted into irradiated mice, the expanded cells gave rise to mature hematopoietic populations and a self-renewing cell population that was able to support hematopoiesis upon serial transplantation.

The researchers said these results suggest their technique may be an attractive approach to expand human HSPCs ex vivo for clinical use.

The team’s goal now is to move the technology from the lab into clinical trials. Taiga Biotechnologies is in the process of setting up clinical trials testing this approach. ![]()

Credit: Chad McNeeley

A new technique has allowed researchers to expand hematopoietic stem and progenitor cells (HSPCs) from multiple sources.

The team developed fusion proteins and introduced them to HSPCs ex vivo.

This approach expanded cell populations whether HSPCs were derived from cord blood, bone marrow, or peripheral blood.

The potential clinical applications for this work range from immunodeficiency disorders to hematologic and other malignancies, according to the researchers.

Yosef Refaeli, PhD, of Taiga Biotechnologies, Inc. in Aurora, Colorado, and his colleagues described this work in PLOS ONE.

The team first cultured human or murine HSPCs with a pair of fusion proteins—the protein transduction domain of the HIV-1 transactivation protein (Tat) and either the Open Reading Frame for human MYC or a truncated form of human Bcl-2 that was deleted for the unstructured loop domain.

With this technique, the researchers were able to elicit an 87-fold expansion of HSPCs from mouse bone marrow, a 16.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human cord blood, a 13.6-fold expansion of HSPCs from human peripheral blood cells mobilized by G-CSF, and a 10-fold expansion of HSPCs from human bone marrow.

The team then tested the biological function of the expanded cells, and they found the cells gave rise to BFU-E, CFU-M, CFU-G, and CFU-GM colonies in vitro.

When transplanted into irradiated mice, the expanded cells gave rise to mature hematopoietic populations and a self-renewing cell population that was able to support hematopoiesis upon serial transplantation.

The researchers said these results suggest their technique may be an attractive approach to expand human HSPCs ex vivo for clinical use.

The team’s goal now is to move the technology from the lab into clinical trials. Taiga Biotechnologies is in the process of setting up clinical trials testing this approach. ![]()

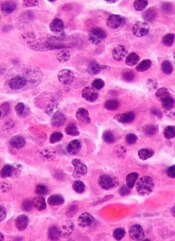

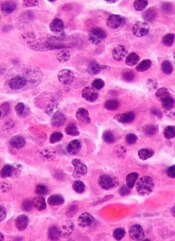

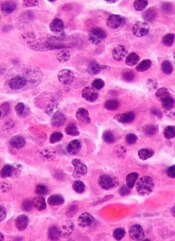

Studies advance understanding of plasma cells

Murine studies have revealed signaling molecules that appear to play crucial roles in plasma cell development and survival.

Investigators found the adaptor protein DOK3 promotes the differentiation of plasma cells, and the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP1 enables plasma cell migration.

The team said these discoveries advance our understanding of plasma cells and may help us improve treatment for multiple myeloma and autoimmune disorders.

In PNAS, Kong-Peng Lam, PhD, of the Bioprocessing Technology Institute in Singapore, and his colleagues reported their discovery that DOK3 plays an important role in the formation of plasma cells.

The team found that calcium signaling inhibits the expression of PDL1 and PDL2, membrane proteins that are essential for plasma cell formation.

But DOK3 can promote the production of plasma cells by reducing the effects of calcium signaling on these proteins. And conversely, the absence of DOK3 results in defective plasma cell formation.

In Nature Communications, Dr Lam and his colleagues reported their discovery that SHP1 signaling is important for the long-term survival of plasma cells.

The researchers found that, in the absence of SHP1, plasma cells fail to migrate from the spleen to the bone marrow. This can impair the body’s immune response and increase susceptibility to infections and diseases.

However, Dr Lam and his colleagues were able to rectify the defective immune response caused by SHP1 deletion with antibody injections, a result that might aid the development of therapeutics for autoimmune disorders.

On the other hand, targeting SHP1 might be a strategy to treat multiple myeloma, in which the accumulation of cancerous plasma cells in the bone marrow is undesirable.

“These findings allow better understanding of plasma cells and their role in the immune system,” Dr Lam said. “The identification of these targets not only paves the way for development of therapeutics for those with autoimmune diseases and multiple myeloma but also impacts the development of immunological agents for combating infections.” ![]()

Murine studies have revealed signaling molecules that appear to play crucial roles in plasma cell development and survival.

Investigators found the adaptor protein DOK3 promotes the differentiation of plasma cells, and the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP1 enables plasma cell migration.

The team said these discoveries advance our understanding of plasma cells and may help us improve treatment for multiple myeloma and autoimmune disorders.

In PNAS, Kong-Peng Lam, PhD, of the Bioprocessing Technology Institute in Singapore, and his colleagues reported their discovery that DOK3 plays an important role in the formation of plasma cells.

The team found that calcium signaling inhibits the expression of PDL1 and PDL2, membrane proteins that are essential for plasma cell formation.

But DOK3 can promote the production of plasma cells by reducing the effects of calcium signaling on these proteins. And conversely, the absence of DOK3 results in defective plasma cell formation.

In Nature Communications, Dr Lam and his colleagues reported their discovery that SHP1 signaling is important for the long-term survival of plasma cells.

The researchers found that, in the absence of SHP1, plasma cells fail to migrate from the spleen to the bone marrow. This can impair the body’s immune response and increase susceptibility to infections and diseases.

However, Dr Lam and his colleagues were able to rectify the defective immune response caused by SHP1 deletion with antibody injections, a result that might aid the development of therapeutics for autoimmune disorders.

On the other hand, targeting SHP1 might be a strategy to treat multiple myeloma, in which the accumulation of cancerous plasma cells in the bone marrow is undesirable.

“These findings allow better understanding of plasma cells and their role in the immune system,” Dr Lam said. “The identification of these targets not only paves the way for development of therapeutics for those with autoimmune diseases and multiple myeloma but also impacts the development of immunological agents for combating infections.” ![]()

Murine studies have revealed signaling molecules that appear to play crucial roles in plasma cell development and survival.

Investigators found the adaptor protein DOK3 promotes the differentiation of plasma cells, and the protein-tyrosine phosphatase SHP1 enables plasma cell migration.

The team said these discoveries advance our understanding of plasma cells and may help us improve treatment for multiple myeloma and autoimmune disorders.

In PNAS, Kong-Peng Lam, PhD, of the Bioprocessing Technology Institute in Singapore, and his colleagues reported their discovery that DOK3 plays an important role in the formation of plasma cells.

The team found that calcium signaling inhibits the expression of PDL1 and PDL2, membrane proteins that are essential for plasma cell formation.

But DOK3 can promote the production of plasma cells by reducing the effects of calcium signaling on these proteins. And conversely, the absence of DOK3 results in defective plasma cell formation.

In Nature Communications, Dr Lam and his colleagues reported their discovery that SHP1 signaling is important for the long-term survival of plasma cells.

The researchers found that, in the absence of SHP1, plasma cells fail to migrate from the spleen to the bone marrow. This can impair the body’s immune response and increase susceptibility to infections and diseases.

However, Dr Lam and his colleagues were able to rectify the defective immune response caused by SHP1 deletion with antibody injections, a result that might aid the development of therapeutics for autoimmune disorders.

On the other hand, targeting SHP1 might be a strategy to treat multiple myeloma, in which the accumulation of cancerous plasma cells in the bone marrow is undesirable.

“These findings allow better understanding of plasma cells and their role in the immune system,” Dr Lam said. “The identification of these targets not only paves the way for development of therapeutics for those with autoimmune diseases and multiple myeloma but also impacts the development of immunological agents for combating infections.” ![]()

Negotiation Skills for Physicians

Summary

Physicians suffer from “arrested development,” said Dr. Chiang, a hospitalist and chief of inpatient services at Boston Children’s Hospital, during a PHM2014 workshop on the basics of negotiation. Dr. Chiang was referring to the fact that in several professional realms, including negotiation, most physicians have not had the traditional experience of interviewing and negotiating for jobs after high school or college.

An understanding of several negotiation concepts can help the negotiator achieve an agreeable solution. Awareness of values and limits prior to the actual discussion or negotiation will increase the chance of a successful negotiation. Examples of some of these concepts are:

- Best alternative to a negotiation agreement (BATNA). This is the course of action if negotiations fail. The negotiator should not accept a worse resolution than the BATNA.

- Reservation value (RV). This is the lowest value a negotiator will accept in a deal.

- Zone of possible agreement (ZOPA). This is the intellectual zone between two parties in a negotiation where an agreement can be reached.

The twin tasks of negotiation are a) learning about the true ZOPA in advance and b) determining how to influence the other person’s perception of this zone.

There are several negotiation methods and strategies of influence that can be used to support your position or goals. For example, status quo bias is very common. Addressing the specific reason a person is not willing to change from the status quo enables progress.

While it is important to advocate for one’s position, fairness is an important variable in reaching an agreement. Fairness often is not universally defined. Communication is essential in understanding each group’s position.

Summary

Physicians suffer from “arrested development,” said Dr. Chiang, a hospitalist and chief of inpatient services at Boston Children’s Hospital, during a PHM2014 workshop on the basics of negotiation. Dr. Chiang was referring to the fact that in several professional realms, including negotiation, most physicians have not had the traditional experience of interviewing and negotiating for jobs after high school or college.

An understanding of several negotiation concepts can help the negotiator achieve an agreeable solution. Awareness of values and limits prior to the actual discussion or negotiation will increase the chance of a successful negotiation. Examples of some of these concepts are:

- Best alternative to a negotiation agreement (BATNA). This is the course of action if negotiations fail. The negotiator should not accept a worse resolution than the BATNA.

- Reservation value (RV). This is the lowest value a negotiator will accept in a deal.

- Zone of possible agreement (ZOPA). This is the intellectual zone between two parties in a negotiation where an agreement can be reached.

The twin tasks of negotiation are a) learning about the true ZOPA in advance and b) determining how to influence the other person’s perception of this zone.

There are several negotiation methods and strategies of influence that can be used to support your position or goals. For example, status quo bias is very common. Addressing the specific reason a person is not willing to change from the status quo enables progress.

While it is important to advocate for one’s position, fairness is an important variable in reaching an agreement. Fairness often is not universally defined. Communication is essential in understanding each group’s position.

Summary

Physicians suffer from “arrested development,” said Dr. Chiang, a hospitalist and chief of inpatient services at Boston Children’s Hospital, during a PHM2014 workshop on the basics of negotiation. Dr. Chiang was referring to the fact that in several professional realms, including negotiation, most physicians have not had the traditional experience of interviewing and negotiating for jobs after high school or college.

An understanding of several negotiation concepts can help the negotiator achieve an agreeable solution. Awareness of values and limits prior to the actual discussion or negotiation will increase the chance of a successful negotiation. Examples of some of these concepts are:

- Best alternative to a negotiation agreement (BATNA). This is the course of action if negotiations fail. The negotiator should not accept a worse resolution than the BATNA.

- Reservation value (RV). This is the lowest value a negotiator will accept in a deal.

- Zone of possible agreement (ZOPA). This is the intellectual zone between two parties in a negotiation where an agreement can be reached.

The twin tasks of negotiation are a) learning about the true ZOPA in advance and b) determining how to influence the other person’s perception of this zone.

There are several negotiation methods and strategies of influence that can be used to support your position or goals. For example, status quo bias is very common. Addressing the specific reason a person is not willing to change from the status quo enables progress.

While it is important to advocate for one’s position, fairness is an important variable in reaching an agreement. Fairness often is not universally defined. Communication is essential in understanding each group’s position.

Best Practices in Pulsed Dye Laser Treatment

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."

For more information, access Dr. Ezra's article from the August 2014 issue, "Linear Scarring Following Treatment With a 595-nm Pulsed Dye Laser."