User login

Overcoming an obstacle to RBC development

Researchers have discovered a natural barrier to hematopoiesis and a way to circumvent it, according to a paper published in Blood.

The group found that components of the exosome complex—exosc8 and exosc9—suppress red blood cell (RBC) maturation.

“From a fundamental perspective, this is very important because this mechanism counteracts the development of precursor cells into red blood cells, thereby establishing a balance between developed cells and the progenitor population,” said study author Emery Bresnick, PhD, of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, Wisconsin.

“In the context of translation, if you want to maximize the output of end-stage red blood cells, which we’re not able to do at this time, our study provides a rational approach involving lowering the levels of these subunits.”

Specifically, the researchers found that GATA-1 and Foxo3 can repress the exosome components, thereby allowing for RBC maturation.

The barrier explained

Dr Bresnick and his colleagues noted that the primary obstacle in converting hematopoietic stem cells into RBCs involves late-stage maturation.

“The problem isn’t simply getting erythroid precursors produced by the bucket, but understanding how these cells systematically lose their nuclei and organelles to become a red blood cell, the final product,” Dr Bresnick said.

“This is the bottleneck, even in the stem cell world of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. We know little about how the cell orchestrates the intricate processes that constitute late-stage maturation.”

At the end of RBC development, the erythroid precursor must eject its own genetic material via enucleation. Although it’s clear why enucleation is important (making the cell more flexible and allowing it to carry more oxygen), exactly how the cell does it has been unclear.

Besides ejecting the nucleus, the cell must be cleared of other organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This process (autophagy) is linked to a pair of transcription factors—GATA1 and Foxo3—that control gene expression important in RBC development.

Because they knew GATA1 and Foxo3 promote autophagy, Dr Bresnick and his colleagues wondered if the proteins these transcription factors repress play an important role in cell maturation.

This led them to identify exosc8 and exosc9, two units of the exosome that ultimately established the development barrier.

The researchers plan to continue studying the exosome because many RNAs in the cell are not degraded by the exosome. Determining exactly how the exosome decides what RNA to dispose of may provide an even better understanding of the newly discovered barrier.

“One goal we have is to establish the specific RNA targets the exosome is regulating that are responsible for the blockade,” Dr Bresnick said. “In doing so, we might even uncover targets that are easier to manipulate than the exosome itself.” ![]()

Researchers have discovered a natural barrier to hematopoiesis and a way to circumvent it, according to a paper published in Blood.

The group found that components of the exosome complex—exosc8 and exosc9—suppress red blood cell (RBC) maturation.

“From a fundamental perspective, this is very important because this mechanism counteracts the development of precursor cells into red blood cells, thereby establishing a balance between developed cells and the progenitor population,” said study author Emery Bresnick, PhD, of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, Wisconsin.

“In the context of translation, if you want to maximize the output of end-stage red blood cells, which we’re not able to do at this time, our study provides a rational approach involving lowering the levels of these subunits.”

Specifically, the researchers found that GATA-1 and Foxo3 can repress the exosome components, thereby allowing for RBC maturation.

The barrier explained

Dr Bresnick and his colleagues noted that the primary obstacle in converting hematopoietic stem cells into RBCs involves late-stage maturation.

“The problem isn’t simply getting erythroid precursors produced by the bucket, but understanding how these cells systematically lose their nuclei and organelles to become a red blood cell, the final product,” Dr Bresnick said.

“This is the bottleneck, even in the stem cell world of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. We know little about how the cell orchestrates the intricate processes that constitute late-stage maturation.”

At the end of RBC development, the erythroid precursor must eject its own genetic material via enucleation. Although it’s clear why enucleation is important (making the cell more flexible and allowing it to carry more oxygen), exactly how the cell does it has been unclear.

Besides ejecting the nucleus, the cell must be cleared of other organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This process (autophagy) is linked to a pair of transcription factors—GATA1 and Foxo3—that control gene expression important in RBC development.

Because they knew GATA1 and Foxo3 promote autophagy, Dr Bresnick and his colleagues wondered if the proteins these transcription factors repress play an important role in cell maturation.

This led them to identify exosc8 and exosc9, two units of the exosome that ultimately established the development barrier.

The researchers plan to continue studying the exosome because many RNAs in the cell are not degraded by the exosome. Determining exactly how the exosome decides what RNA to dispose of may provide an even better understanding of the newly discovered barrier.

“One goal we have is to establish the specific RNA targets the exosome is regulating that are responsible for the blockade,” Dr Bresnick said. “In doing so, we might even uncover targets that are easier to manipulate than the exosome itself.” ![]()

Researchers have discovered a natural barrier to hematopoiesis and a way to circumvent it, according to a paper published in Blood.

The group found that components of the exosome complex—exosc8 and exosc9—suppress red blood cell (RBC) maturation.

“From a fundamental perspective, this is very important because this mechanism counteracts the development of precursor cells into red blood cells, thereby establishing a balance between developed cells and the progenitor population,” said study author Emery Bresnick, PhD, of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health in Madison, Wisconsin.

“In the context of translation, if you want to maximize the output of end-stage red blood cells, which we’re not able to do at this time, our study provides a rational approach involving lowering the levels of these subunits.”

Specifically, the researchers found that GATA-1 and Foxo3 can repress the exosome components, thereby allowing for RBC maturation.

The barrier explained

Dr Bresnick and his colleagues noted that the primary obstacle in converting hematopoietic stem cells into RBCs involves late-stage maturation.

“The problem isn’t simply getting erythroid precursors produced by the bucket, but understanding how these cells systematically lose their nuclei and organelles to become a red blood cell, the final product,” Dr Bresnick said.

“This is the bottleneck, even in the stem cell world of embryonic and induced pluripotent stem cells. We know little about how the cell orchestrates the intricate processes that constitute late-stage maturation.”

At the end of RBC development, the erythroid precursor must eject its own genetic material via enucleation. Although it’s clear why enucleation is important (making the cell more flexible and allowing it to carry more oxygen), exactly how the cell does it has been unclear.

Besides ejecting the nucleus, the cell must be cleared of other organelles, such as the endoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. This process (autophagy) is linked to a pair of transcription factors—GATA1 and Foxo3—that control gene expression important in RBC development.

Because they knew GATA1 and Foxo3 promote autophagy, Dr Bresnick and his colleagues wondered if the proteins these transcription factors repress play an important role in cell maturation.

This led them to identify exosc8 and exosc9, two units of the exosome that ultimately established the development barrier.

The researchers plan to continue studying the exosome because many RNAs in the cell are not degraded by the exosome. Determining exactly how the exosome decides what RNA to dispose of may provide an even better understanding of the newly discovered barrier.

“One goal we have is to establish the specific RNA targets the exosome is regulating that are responsible for the blockade,” Dr Bresnick said. “In doing so, we might even uncover targets that are easier to manipulate than the exosome itself.” ![]()

Health Canada approves dabigatran for VTE

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

Health Canada has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Dabigatran is a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor that has been on the market for more than 5 years and is approved in more than 100 countries.

Health Canada’s latest approval of dabigatran is based on results from four phase 3 trials—RE-MEDY, RE-SONATE, and RE-COVER I and II.

The trials suggested that dabigatran given at 150 mg twice daily can treat and prevent a recurrence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

RE-COVER I

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms. However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events.

VTE recurred in 2.4% of patients treated with dabigatran and 2.1% of patients who received warfarin (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Bleeding events occurred in 16.1% of patients who received dabigatran and 21.9% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001). Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% and 1.9% of patients, respectively (P=0.38).

The numbers of deaths, acute coronary syndromes, and abnormal liver-function tests were similar between the treatment arms. But adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 9.0% of dabigatran-treated patients and 6.8% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.05).

Results from RE-COVER were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

RE-COVER II

The RE-COVER II trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths. This outcome occurred in 2.3% of dabigatran-treated patients and 2.2% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Major bleeding occurred 1.2% of patients who received dabigatran and 1.7% of patients who received warfarin. Any bleeding occurred in 15.6% and 22.1% of patients, respectively.

Overall, rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms.

Results from RE-COVER II were published in Circulation in 2013.

RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial showed that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

VTE recurred in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 1.3% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.01 for noninferiority). And the rate of clinically relevant or major bleeding was lower with dabigatran than with warfarin—at 5.6% and 10.2%, respectively (P<0.001).

Results of the RE-SONATE trial showed that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding.

VTE recurred in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 5.6% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001). Clinically relevant or major bleeding occurred in 5.3% of patients in the dabigatran and 1.8% of patients in the placebo arm (P=0.001).

Safety concerns with dabigatran

Over the years, the safety of dabigatran has been called into question, as serious bleeding events have been reported in patients taking the drug.

However, results of two investigations by the US Food and Drug Administration—one reported in 2012 and one reported this year—have suggested the benefits of dabigatran outweigh the risks.

Recently, a series of papers published in The BMJ raised concerns about dabigatran, claiming the drug’s developer underreported adverse events and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy. The developer, Boehringer Ingelheim, denied these allegations.

For more information on dabigatran, see its product monograph. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

Health Canada has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Dabigatran is a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor that has been on the market for more than 5 years and is approved in more than 100 countries.

Health Canada’s latest approval of dabigatran is based on results from four phase 3 trials—RE-MEDY, RE-SONATE, and RE-COVER I and II.

The trials suggested that dabigatran given at 150 mg twice daily can treat and prevent a recurrence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

RE-COVER I

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms. However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events.

VTE recurred in 2.4% of patients treated with dabigatran and 2.1% of patients who received warfarin (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Bleeding events occurred in 16.1% of patients who received dabigatran and 21.9% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001). Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% and 1.9% of patients, respectively (P=0.38).

The numbers of deaths, acute coronary syndromes, and abnormal liver-function tests were similar between the treatment arms. But adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 9.0% of dabigatran-treated patients and 6.8% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.05).

Results from RE-COVER were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

RE-COVER II

The RE-COVER II trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths. This outcome occurred in 2.3% of dabigatran-treated patients and 2.2% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Major bleeding occurred 1.2% of patients who received dabigatran and 1.7% of patients who received warfarin. Any bleeding occurred in 15.6% and 22.1% of patients, respectively.

Overall, rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms.

Results from RE-COVER II were published in Circulation in 2013.

RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial showed that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

VTE recurred in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 1.3% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.01 for noninferiority). And the rate of clinically relevant or major bleeding was lower with dabigatran than with warfarin—at 5.6% and 10.2%, respectively (P<0.001).

Results of the RE-SONATE trial showed that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding.

VTE recurred in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 5.6% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001). Clinically relevant or major bleeding occurred in 5.3% of patients in the dabigatran and 1.8% of patients in the placebo arm (P=0.001).

Safety concerns with dabigatran

Over the years, the safety of dabigatran has been called into question, as serious bleeding events have been reported in patients taking the drug.

However, results of two investigations by the US Food and Drug Administration—one reported in 2012 and one reported this year—have suggested the benefits of dabigatran outweigh the risks.

Recently, a series of papers published in The BMJ raised concerns about dabigatran, claiming the drug’s developer underreported adverse events and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy. The developer, Boehringer Ingelheim, denied these allegations.

For more information on dabigatran, see its product monograph. ![]()

Credit: Kevin MacKenzie

Health Canada has approved dabigatran etexilate (Pradaxa) for the treatment and prevention of venous thromboembolism (VTE).

Dabigatran is a novel, reversible, oral direct thrombin inhibitor that has been on the market for more than 5 years and is approved in more than 100 countries.

Health Canada’s latest approval of dabigatran is based on results from four phase 3 trials—RE-MEDY, RE-SONATE, and RE-COVER I and II.

The trials suggested that dabigatran given at 150 mg twice daily can treat and prevent a recurrence of deep vein thrombosis or pulmonary embolism.

RE-COVER I

In the first RE-COVER trial, dabigatran proved noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence, and rates of major bleeding were similar between the treatment arms. However, patients were more likely to discontinue dabigatran due to adverse events.

VTE recurred in 2.4% of patients treated with dabigatran and 2.1% of patients who received warfarin (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Bleeding events occurred in 16.1% of patients who received dabigatran and 21.9% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001). Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% and 1.9% of patients, respectively (P=0.38).

The numbers of deaths, acute coronary syndromes, and abnormal liver-function tests were similar between the treatment arms. But adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation occurred in 9.0% of dabigatran-treated patients and 6.8% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.05).

Results from RE-COVER were presented at ASH 2009 and published in NEJM.

RE-COVER II

The RE-COVER II trial suggested that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin for preventing VTE recurrence and related deaths. This outcome occurred in 2.3% of dabigatran-treated patients and 2.2% of warfarin-treated patients (P<0.001 for noninferiority).

Major bleeding occurred 1.2% of patients who received dabigatran and 1.7% of patients who received warfarin. Any bleeding occurred in 15.6% and 22.1% of patients, respectively.

Overall, rates of death, adverse events, and acute coronary syndromes were similar between the treatment arms.

Results from RE-COVER II were published in Circulation in 2013.

RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE

The RE-MEDY and RE-SONATE trials were designed to evaluate dabigatran as extended VTE prophylaxis. Results of both trials were reported in a single NEJM article published in 2013.

The RE-MEDY trial showed that dabigatran was noninferior to warfarin as extended prophylaxis for recurrent VTE, and warfarin presented a significantly higher risk of bleeding.

VTE recurred in 1.8% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 1.3% of patients in the warfarin arm (P=0.01 for noninferiority). And the rate of clinically relevant or major bleeding was lower with dabigatran than with warfarin—at 5.6% and 10.2%, respectively (P<0.001).

Results of the RE-SONATE trial showed that dabigatran was superior to placebo for preventing recurrent VTE, although the drug significantly increased the risk of major or clinically relevant bleeding.

VTE recurred in 0.4% of patients in the dabigatran arm and 5.6% of patients in the placebo arm (P<0.001). Clinically relevant or major bleeding occurred in 5.3% of patients in the dabigatran and 1.8% of patients in the placebo arm (P=0.001).

Safety concerns with dabigatran

Over the years, the safety of dabigatran has been called into question, as serious bleeding events have been reported in patients taking the drug.

However, results of two investigations by the US Food and Drug Administration—one reported in 2012 and one reported this year—have suggested the benefits of dabigatran outweigh the risks.

Recently, a series of papers published in The BMJ raised concerns about dabigatran, claiming the drug’s developer underreported adverse events and withheld data showing that monitoring and dose adjustment could improve the safety of dabigatran without compromising its efficacy. The developer, Boehringer Ingelheim, denied these allegations.

For more information on dabigatran, see its product monograph. ![]()

ID Consult: National immunization coverage and measles

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. For most pediatricians, it is also a very busy month as patients prepare for the start of the new school year. So how are we doing?

On August 28, 2013, vaccination coverage of U.S. children aged 19-35 months was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review (2014; 63:741-8) based on results from the National Information Survey (NIS), which provides national, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage estimates. NIS has monitored vaccination coverage since 1994 for all 50 states and assists in tracking the progress of achieving our national goals. It also can identify problem areas that may require special interventions. Survey data was obtained by a random telephone survey using both landline and cellular phones to households that have children born between January 2010 and May 2012. The verbal interview was followed by a survey mailed to the vaccine provider to confirm the verbal vaccine history.

Highlights

Vaccination coverage of at least 90 %, a goal of Healthy People 2020, was achieved for receipt of one or more dose of MMR (91.9%); three or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) (90.8 %); three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine (92.7%) and one or more doses of varicella vaccine (91.2%).

Coverage for the following vaccines failed to meet this goal: four or more doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (DTaP) (83.1%); four or more doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) (82%); and a full series of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) (82%). Coverage for the remaining vaccines also fell short of their respective targeted goals: two or more doses of hepatitis A vaccine (54.7%; target 85%); rotavirus (72.6%; target 80%); and hepatitis B birth dose (74.2%; target 85%).

Compared with 2012, coverage remained stable for the four vaccines that achieved at least 90% coverage. For those that did not, rotavirus was the only vaccine in 2013 that had an increase (4%) in coverage. Of note, there was an increase in the birth dose of 2.6% for Hep B.

Children living at or below the poverty level had lower vaccination coverage, compared with those living at or above this level for several vaccines, including four or more doses of DTaP; full series of Hib vaccine, four or more doses of PCV, and rotavirus vaccine. Coverage was between 8% and 12.6% points lower for these vaccines.

Measles

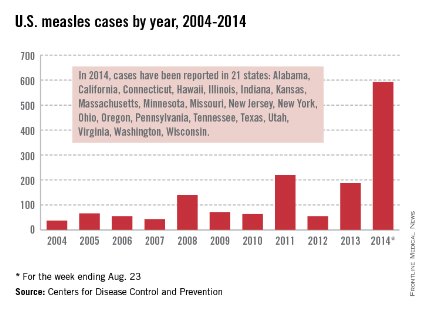

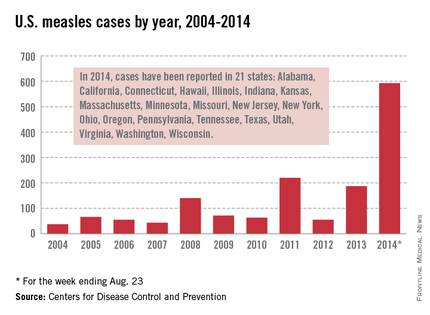

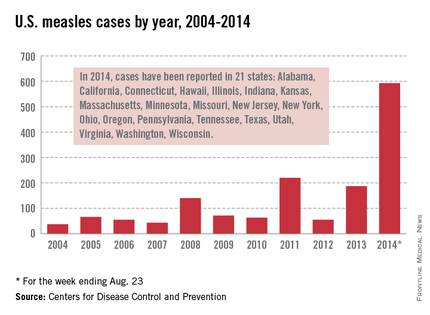

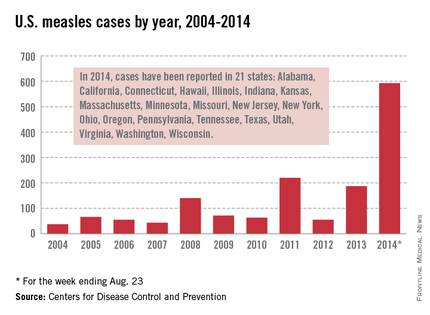

Let’s take a closer look at measles. Nationally, almost 92 % of children received at least one dose of MMR. However, coverage varied by state – an observation unchanged from 2012. New Hampshire had the highest coverage at 96.3% and three states had coverage of only 86% (Colorado, Ohio, and West Virginia). Overall 17 states had immunization rates less than 90%. Additionally, 1 in 12 children did not receive their first dose of MMR on time. Why the concern? In 2013, there were 187 cases of measles including 11 outbreaks. A total of 82% occurred in unvaccinated individuals, and another 9% were unaware of their immunization status.

As of Aug. 25, 2014, there were 595 cases of measles in the United States in 21 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. This is the highest number of cases reported since endemic measles was eliminated in 2000. There were as a result of 18 outbreaks, representing 89% of the reported cases. Cases are occurring even in states where immunization rates are reported to be at least 90% – a reminder that there can be pockets of low or nonimmunizing communities that leave its citizens vulnerable to outbreaks when a highly contagious virus is introduced.

Since endemic measles was eliminated 14 years ago in the United States, many health care providers have never seen a case of measles or may not realize the impact it once had on our public health system. Prior to the initiation of the measles vaccination program in 1963, 3-4 million cases of measles occurred annually in the United States with 400-500 deaths and 48,000 hospitalizations. Approximately another 1,000 individuals were left disabled secondary to measles encephalitis. Once the vaccine was introduced, the incidence of measles declined 98%, according to "Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases," 12th ed., second printing. (Washington, D.C: Public Health Foundation, 2012). Between 1989 and 1991, there was a resurgence of measles resulting in approximately 55,000 cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 123 deaths. The resurgence was caused primarily by the failure to vaccinate uninsured children at the recommended 12-15 months of age. Children younger than 5 years of age accounted for 45% of all cases. The Vaccines for Children Program was created in 1993 as a direct response to the resurgence of measles. It would ensure that no child would contract a vaccine preventable disease because of inability to pay.

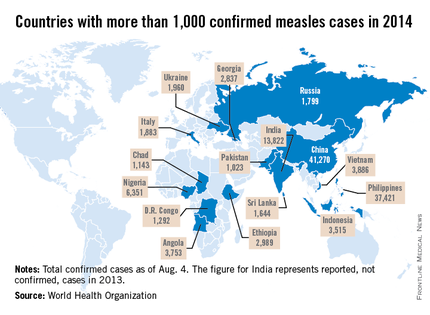

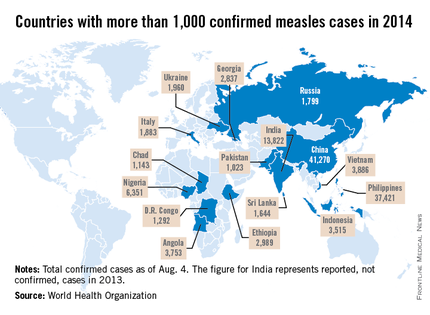

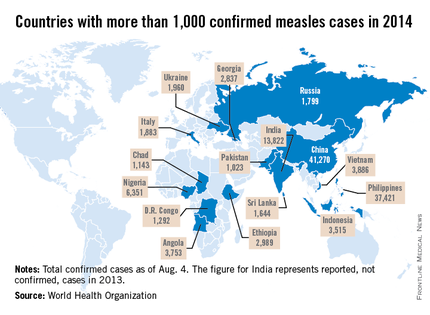

Measles remains endemic in multiple countries worldwide that are travel destinations for many Americans. In 2013, 99% of 159 U.S. cases were import related. An overwhelming majority of infections occurred in unvaccinated individuals. In 2014, this trend continues, with the majority of cases occurring in unvaccinated international travelers who return infected and spread disease to susceptible persons including children in their communities (MMWR 2014:63;496-9). Of the 288 cases reported in by May 23, 2014, 97% were associated with importations from 18 countries.

High immunization coverage must be maintained to prevent and sustain measles elimination in the United States. As a reminder, all children aged 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR ideally 2 weeks prior to international travel. When the infant is at least 12 months of age, they should receive two additional doses of MMR or MMRV according to the routine immunization schedule. Those children older than 12 months of age should receive two doses of MMR. The second can be administered as soon as 4 weeks after the first dose. It is not uncommon for families to travel internationally and fail to mention it to you. Many have been told their child’s immunizations are up to date, not realizing that international travel may alter that definition. It behooves primary care providers to develop strategies to facilitate discussions regarding sharing international travel plans in a timely manner.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. For most pediatricians, it is also a very busy month as patients prepare for the start of the new school year. So how are we doing?

On August 28, 2013, vaccination coverage of U.S. children aged 19-35 months was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review (2014; 63:741-8) based on results from the National Information Survey (NIS), which provides national, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage estimates. NIS has monitored vaccination coverage since 1994 for all 50 states and assists in tracking the progress of achieving our national goals. It also can identify problem areas that may require special interventions. Survey data was obtained by a random telephone survey using both landline and cellular phones to households that have children born between January 2010 and May 2012. The verbal interview was followed by a survey mailed to the vaccine provider to confirm the verbal vaccine history.

Highlights

Vaccination coverage of at least 90 %, a goal of Healthy People 2020, was achieved for receipt of one or more dose of MMR (91.9%); three or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) (90.8 %); three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine (92.7%) and one or more doses of varicella vaccine (91.2%).

Coverage for the following vaccines failed to meet this goal: four or more doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (DTaP) (83.1%); four or more doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) (82%); and a full series of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) (82%). Coverage for the remaining vaccines also fell short of their respective targeted goals: two or more doses of hepatitis A vaccine (54.7%; target 85%); rotavirus (72.6%; target 80%); and hepatitis B birth dose (74.2%; target 85%).

Compared with 2012, coverage remained stable for the four vaccines that achieved at least 90% coverage. For those that did not, rotavirus was the only vaccine in 2013 that had an increase (4%) in coverage. Of note, there was an increase in the birth dose of 2.6% for Hep B.

Children living at or below the poverty level had lower vaccination coverage, compared with those living at or above this level for several vaccines, including four or more doses of DTaP; full series of Hib vaccine, four or more doses of PCV, and rotavirus vaccine. Coverage was between 8% and 12.6% points lower for these vaccines.

Measles

Let’s take a closer look at measles. Nationally, almost 92 % of children received at least one dose of MMR. However, coverage varied by state – an observation unchanged from 2012. New Hampshire had the highest coverage at 96.3% and three states had coverage of only 86% (Colorado, Ohio, and West Virginia). Overall 17 states had immunization rates less than 90%. Additionally, 1 in 12 children did not receive their first dose of MMR on time. Why the concern? In 2013, there were 187 cases of measles including 11 outbreaks. A total of 82% occurred in unvaccinated individuals, and another 9% were unaware of their immunization status.

As of Aug. 25, 2014, there were 595 cases of measles in the United States in 21 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. This is the highest number of cases reported since endemic measles was eliminated in 2000. There were as a result of 18 outbreaks, representing 89% of the reported cases. Cases are occurring even in states where immunization rates are reported to be at least 90% – a reminder that there can be pockets of low or nonimmunizing communities that leave its citizens vulnerable to outbreaks when a highly contagious virus is introduced.

Since endemic measles was eliminated 14 years ago in the United States, many health care providers have never seen a case of measles or may not realize the impact it once had on our public health system. Prior to the initiation of the measles vaccination program in 1963, 3-4 million cases of measles occurred annually in the United States with 400-500 deaths and 48,000 hospitalizations. Approximately another 1,000 individuals were left disabled secondary to measles encephalitis. Once the vaccine was introduced, the incidence of measles declined 98%, according to "Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases," 12th ed., second printing. (Washington, D.C: Public Health Foundation, 2012). Between 1989 and 1991, there was a resurgence of measles resulting in approximately 55,000 cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 123 deaths. The resurgence was caused primarily by the failure to vaccinate uninsured children at the recommended 12-15 months of age. Children younger than 5 years of age accounted for 45% of all cases. The Vaccines for Children Program was created in 1993 as a direct response to the resurgence of measles. It would ensure that no child would contract a vaccine preventable disease because of inability to pay.

Measles remains endemic in multiple countries worldwide that are travel destinations for many Americans. In 2013, 99% of 159 U.S. cases were import related. An overwhelming majority of infections occurred in unvaccinated individuals. In 2014, this trend continues, with the majority of cases occurring in unvaccinated international travelers who return infected and spread disease to susceptible persons including children in their communities (MMWR 2014:63;496-9). Of the 288 cases reported in by May 23, 2014, 97% were associated with importations from 18 countries.

High immunization coverage must be maintained to prevent and sustain measles elimination in the United States. As a reminder, all children aged 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR ideally 2 weeks prior to international travel. When the infant is at least 12 months of age, they should receive two additional doses of MMR or MMRV according to the routine immunization schedule. Those children older than 12 months of age should receive two doses of MMR. The second can be administered as soon as 4 weeks after the first dose. It is not uncommon for families to travel internationally and fail to mention it to you. Many have been told their child’s immunizations are up to date, not realizing that international travel may alter that definition. It behooves primary care providers to develop strategies to facilitate discussions regarding sharing international travel plans in a timely manner.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

August was National Immunization Awareness Month. For most pediatricians, it is also a very busy month as patients prepare for the start of the new school year. So how are we doing?

On August 28, 2013, vaccination coverage of U.S. children aged 19-35 months was published in Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Review (2014; 63:741-8) based on results from the National Information Survey (NIS), which provides national, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage estimates. NIS has monitored vaccination coverage since 1994 for all 50 states and assists in tracking the progress of achieving our national goals. It also can identify problem areas that may require special interventions. Survey data was obtained by a random telephone survey using both landline and cellular phones to households that have children born between January 2010 and May 2012. The verbal interview was followed by a survey mailed to the vaccine provider to confirm the verbal vaccine history.

Highlights

Vaccination coverage of at least 90 %, a goal of Healthy People 2020, was achieved for receipt of one or more dose of MMR (91.9%); three or more doses of hepatitis B vaccine (HepB) (90.8 %); three or more doses of poliovirus vaccine (92.7%) and one or more doses of varicella vaccine (91.2%).

Coverage for the following vaccines failed to meet this goal: four or more doses of diphtheria, tetanus, and pertussis vaccine (DTaP) (83.1%); four or more doses of pneumococcal conjugate vaccine (PCV) (82%); and a full series of Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) (82%). Coverage for the remaining vaccines also fell short of their respective targeted goals: two or more doses of hepatitis A vaccine (54.7%; target 85%); rotavirus (72.6%; target 80%); and hepatitis B birth dose (74.2%; target 85%).

Compared with 2012, coverage remained stable for the four vaccines that achieved at least 90% coverage. For those that did not, rotavirus was the only vaccine in 2013 that had an increase (4%) in coverage. Of note, there was an increase in the birth dose of 2.6% for Hep B.

Children living at or below the poverty level had lower vaccination coverage, compared with those living at or above this level for several vaccines, including four or more doses of DTaP; full series of Hib vaccine, four or more doses of PCV, and rotavirus vaccine. Coverage was between 8% and 12.6% points lower for these vaccines.

Measles

Let’s take a closer look at measles. Nationally, almost 92 % of children received at least one dose of MMR. However, coverage varied by state – an observation unchanged from 2012. New Hampshire had the highest coverage at 96.3% and three states had coverage of only 86% (Colorado, Ohio, and West Virginia). Overall 17 states had immunization rates less than 90%. Additionally, 1 in 12 children did not receive their first dose of MMR on time. Why the concern? In 2013, there were 187 cases of measles including 11 outbreaks. A total of 82% occurred in unvaccinated individuals, and another 9% were unaware of their immunization status.

As of Aug. 25, 2014, there were 595 cases of measles in the United States in 21 states, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Immunization and Respiratory Diseases. This is the highest number of cases reported since endemic measles was eliminated in 2000. There were as a result of 18 outbreaks, representing 89% of the reported cases. Cases are occurring even in states where immunization rates are reported to be at least 90% – a reminder that there can be pockets of low or nonimmunizing communities that leave its citizens vulnerable to outbreaks when a highly contagious virus is introduced.

Since endemic measles was eliminated 14 years ago in the United States, many health care providers have never seen a case of measles or may not realize the impact it once had on our public health system. Prior to the initiation of the measles vaccination program in 1963, 3-4 million cases of measles occurred annually in the United States with 400-500 deaths and 48,000 hospitalizations. Approximately another 1,000 individuals were left disabled secondary to measles encephalitis. Once the vaccine was introduced, the incidence of measles declined 98%, according to "Epidemiology and Prevention of Vaccine-Preventable Diseases," 12th ed., second printing. (Washington, D.C: Public Health Foundation, 2012). Between 1989 and 1991, there was a resurgence of measles resulting in approximately 55,000 cases, 11,000 hospitalizations, and 123 deaths. The resurgence was caused primarily by the failure to vaccinate uninsured children at the recommended 12-15 months of age. Children younger than 5 years of age accounted for 45% of all cases. The Vaccines for Children Program was created in 1993 as a direct response to the resurgence of measles. It would ensure that no child would contract a vaccine preventable disease because of inability to pay.

Measles remains endemic in multiple countries worldwide that are travel destinations for many Americans. In 2013, 99% of 159 U.S. cases were import related. An overwhelming majority of infections occurred in unvaccinated individuals. In 2014, this trend continues, with the majority of cases occurring in unvaccinated international travelers who return infected and spread disease to susceptible persons including children in their communities (MMWR 2014:63;496-9). Of the 288 cases reported in by May 23, 2014, 97% were associated with importations from 18 countries.

High immunization coverage must be maintained to prevent and sustain measles elimination in the United States. As a reminder, all children aged 6-11 months should receive one dose of MMR ideally 2 weeks prior to international travel. When the infant is at least 12 months of age, they should receive two additional doses of MMR or MMRV according to the routine immunization schedule. Those children older than 12 months of age should receive two doses of MMR. The second can be administered as soon as 4 weeks after the first dose. It is not uncommon for families to travel internationally and fail to mention it to you. Many have been told their child’s immunizations are up to date, not realizing that international travel may alter that definition. It behooves primary care providers to develop strategies to facilitate discussions regarding sharing international travel plans in a timely manner.

Dr. Word is a pediatric infectious disease specialist and director of the Houston Travel Medicine Clinic. She had no relevant financial disclosures. Write to Dr. Word at [email protected].

LISTEN NOW: Greg Maynard, MD, SFHM, Chats about SHM's Mentored Implementation Programs

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Maynard

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Maynard

Click here to listen to excerpts of our interview with Dr. Maynard

Right-sided living donor kidney transplant found safe

SAN FRANCISCO – The practice of preferentially using left instead of right kidneys in living donor kidney transplantation may no longer be justified in the era of contemporary laparoscopic surgery, suggests a national study reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"The current approach in many centers is to prefer left living donor nephrectomy due to longer vessel length...Right donor nephrectomy, at least in our center and I think in most centers, has generally been reserved for cases of multiple or complex vessels on the left or incidental anatomical abnormalities on the right like cysts or stones," commented presenting author Dr. Tim E. Taber of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Only one in seven of the roughly 59,000 living donor kidney transplants studied was performed using a right kidney. However, most short- and long-term outcomes were statistically indistinguishable between recipients of left and right kidneys, and the differences that were significant were small, he reported at the congress sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"Our [study] is the largest national analysis or most recent large data analysis done on this subject in today’s surgical era of established laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies. There may be a minor risk for slightly inferior outcomes with right versus left kidneys," Dr. Taber concluded.

"Right-donor nephrectomy continues to be performed with great reluctance," he added. Yet, "under the accepted principles of live-donor nephrectomy, with enough surgical expertise, right-donor nephrectomy can be performed successfully. Right kidneys seem to have a very small difference, if any, in outcomes as compared to left kidneys. Surgical expertise and experience should be tailored toward this aspect."

A session attendee from Brazil commented, "We [prefer] to choose the right kidney in situations where we have one artery on the right side and multiple arteries on the left side." In these cases, his group uses an approach to the vasculature adopted from pancreas transplantation. "We have identical results with the right and left side," he reported.

Dr. Lloyd E. Ratner, director of renal and pancreatic transplantation at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, who also attended the session, said, "I feel somewhat responsible for causing this problem with the right kidney because we were the ones that originally described the higher thrombosis rate with the right kidney with the laparoscopic donor nephrectomies. And I think it scared everyone off from this topic."

As several attendees noted, "there are surgical ways of getting around this," he agreed, offering two more options. "The first is that if we get a short vein, we’re not reluctant at all to put a piece of Dacron onto it, so you don’t even need to dig out the saphenous and cause additional time or morbidity to the patient. And the nice thing about the Dacron grafts is that they are corrugated and they don’t collapse. They also stretch, so you don’t need to cut them exactly precisely," he said.

"And number two is when you are stapling ... it’s often useful to be able to staple onto the cava and not get the vein in one staple byte." By using two passes in the appropriate configuration, "you actually get a cuff of cava, then you have plenty of vein," he explained.

In the study, Dr. Taber and colleagues retrospectively analyzed data from 58,599 adult living donor kidney transplants performed during 2000-2009 and captured in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. In 86% of cases, surgeons used the donor’s left kidney.

Recipients of left and right kidneys were statistically indistinguishable with respect to hospital length of stay, treatment for acute rejection within 6 months, acute rejection as a cause of graft failure, inadequate urine production in the first 24 hours, primary graft failure, graft thrombosis or surgical complication as a contributory cause of graft failure, and 1-year graft survival.

Those receiving a right kidney did have significant but small increases in rates of delayed graft function, as defined by the need for dialysis within 7 days of transplantation (5.7% vs. 4.2%), lack of decline in serum creatinine in the first 24 hours (19.7% vs. 16.4%), treatment for acute rejection within 1 year (12.7% vs. 11.8%), and graft thrombosis as the cause of graft failure (1.1% vs. 0.8%).

The Kaplan-Meier cumulative rate of graft survival was better for left kidneys than for right kidneys (P = .006), but "these are essentially superimposed numbers," said Dr. Taber, who disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the research.

The study had limitations, such as its retrospective design, lack of more detailed information about donor and recipient outcomes, and reliance on data as reported by centers, he acknowledged. Also, such large studies may pick up small differences that are not clinically meaningful.

"With ever-increasing demands for living donor transplantation, right-donor nephrectomies are being considered more often. Every effort should be made to leave the donor with the higher-functioning kidney, but at the same time maximizing the living donor pool," Dr. Taber concluded.

Dr. Taber disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – The practice of preferentially using left instead of right kidneys in living donor kidney transplantation may no longer be justified in the era of contemporary laparoscopic surgery, suggests a national study reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"The current approach in many centers is to prefer left living donor nephrectomy due to longer vessel length...Right donor nephrectomy, at least in our center and I think in most centers, has generally been reserved for cases of multiple or complex vessels on the left or incidental anatomical abnormalities on the right like cysts or stones," commented presenting author Dr. Tim E. Taber of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Only one in seven of the roughly 59,000 living donor kidney transplants studied was performed using a right kidney. However, most short- and long-term outcomes were statistically indistinguishable between recipients of left and right kidneys, and the differences that were significant were small, he reported at the congress sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"Our [study] is the largest national analysis or most recent large data analysis done on this subject in today’s surgical era of established laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies. There may be a minor risk for slightly inferior outcomes with right versus left kidneys," Dr. Taber concluded.

"Right-donor nephrectomy continues to be performed with great reluctance," he added. Yet, "under the accepted principles of live-donor nephrectomy, with enough surgical expertise, right-donor nephrectomy can be performed successfully. Right kidneys seem to have a very small difference, if any, in outcomes as compared to left kidneys. Surgical expertise and experience should be tailored toward this aspect."

A session attendee from Brazil commented, "We [prefer] to choose the right kidney in situations where we have one artery on the right side and multiple arteries on the left side." In these cases, his group uses an approach to the vasculature adopted from pancreas transplantation. "We have identical results with the right and left side," he reported.

Dr. Lloyd E. Ratner, director of renal and pancreatic transplantation at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, who also attended the session, said, "I feel somewhat responsible for causing this problem with the right kidney because we were the ones that originally described the higher thrombosis rate with the right kidney with the laparoscopic donor nephrectomies. And I think it scared everyone off from this topic."

As several attendees noted, "there are surgical ways of getting around this," he agreed, offering two more options. "The first is that if we get a short vein, we’re not reluctant at all to put a piece of Dacron onto it, so you don’t even need to dig out the saphenous and cause additional time or morbidity to the patient. And the nice thing about the Dacron grafts is that they are corrugated and they don’t collapse. They also stretch, so you don’t need to cut them exactly precisely," he said.

"And number two is when you are stapling ... it’s often useful to be able to staple onto the cava and not get the vein in one staple byte." By using two passes in the appropriate configuration, "you actually get a cuff of cava, then you have plenty of vein," he explained.

In the study, Dr. Taber and colleagues retrospectively analyzed data from 58,599 adult living donor kidney transplants performed during 2000-2009 and captured in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. In 86% of cases, surgeons used the donor’s left kidney.

Recipients of left and right kidneys were statistically indistinguishable with respect to hospital length of stay, treatment for acute rejection within 6 months, acute rejection as a cause of graft failure, inadequate urine production in the first 24 hours, primary graft failure, graft thrombosis or surgical complication as a contributory cause of graft failure, and 1-year graft survival.

Those receiving a right kidney did have significant but small increases in rates of delayed graft function, as defined by the need for dialysis within 7 days of transplantation (5.7% vs. 4.2%), lack of decline in serum creatinine in the first 24 hours (19.7% vs. 16.4%), treatment for acute rejection within 1 year (12.7% vs. 11.8%), and graft thrombosis as the cause of graft failure (1.1% vs. 0.8%).

The Kaplan-Meier cumulative rate of graft survival was better for left kidneys than for right kidneys (P = .006), but "these are essentially superimposed numbers," said Dr. Taber, who disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the research.

The study had limitations, such as its retrospective design, lack of more detailed information about donor and recipient outcomes, and reliance on data as reported by centers, he acknowledged. Also, such large studies may pick up small differences that are not clinically meaningful.

"With ever-increasing demands for living donor transplantation, right-donor nephrectomies are being considered more often. Every effort should be made to leave the donor with the higher-functioning kidney, but at the same time maximizing the living donor pool," Dr. Taber concluded.

Dr. Taber disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

SAN FRANCISCO – The practice of preferentially using left instead of right kidneys in living donor kidney transplantation may no longer be justified in the era of contemporary laparoscopic surgery, suggests a national study reported at the 2014 World Transplant Congress.

"The current approach in many centers is to prefer left living donor nephrectomy due to longer vessel length...Right donor nephrectomy, at least in our center and I think in most centers, has generally been reserved for cases of multiple or complex vessels on the left or incidental anatomical abnormalities on the right like cysts or stones," commented presenting author Dr. Tim E. Taber of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

Only one in seven of the roughly 59,000 living donor kidney transplants studied was performed using a right kidney. However, most short- and long-term outcomes were statistically indistinguishable between recipients of left and right kidneys, and the differences that were significant were small, he reported at the congress sponsored by the American Society of Transplant Surgeons.

"Our [study] is the largest national analysis or most recent large data analysis done on this subject in today’s surgical era of established laparoscopic living donor nephrectomies. There may be a minor risk for slightly inferior outcomes with right versus left kidneys," Dr. Taber concluded.

"Right-donor nephrectomy continues to be performed with great reluctance," he added. Yet, "under the accepted principles of live-donor nephrectomy, with enough surgical expertise, right-donor nephrectomy can be performed successfully. Right kidneys seem to have a very small difference, if any, in outcomes as compared to left kidneys. Surgical expertise and experience should be tailored toward this aspect."

A session attendee from Brazil commented, "We [prefer] to choose the right kidney in situations where we have one artery on the right side and multiple arteries on the left side." In these cases, his group uses an approach to the vasculature adopted from pancreas transplantation. "We have identical results with the right and left side," he reported.

Dr. Lloyd E. Ratner, director of renal and pancreatic transplantation at Columbia University Medical Center in New York, who also attended the session, said, "I feel somewhat responsible for causing this problem with the right kidney because we were the ones that originally described the higher thrombosis rate with the right kidney with the laparoscopic donor nephrectomies. And I think it scared everyone off from this topic."

As several attendees noted, "there are surgical ways of getting around this," he agreed, offering two more options. "The first is that if we get a short vein, we’re not reluctant at all to put a piece of Dacron onto it, so you don’t even need to dig out the saphenous and cause additional time or morbidity to the patient. And the nice thing about the Dacron grafts is that they are corrugated and they don’t collapse. They also stretch, so you don’t need to cut them exactly precisely," he said.

"And number two is when you are stapling ... it’s often useful to be able to staple onto the cava and not get the vein in one staple byte." By using two passes in the appropriate configuration, "you actually get a cuff of cava, then you have plenty of vein," he explained.

In the study, Dr. Taber and colleagues retrospectively analyzed data from 58,599 adult living donor kidney transplants performed during 2000-2009 and captured in the United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) database. In 86% of cases, surgeons used the donor’s left kidney.

Recipients of left and right kidneys were statistically indistinguishable with respect to hospital length of stay, treatment for acute rejection within 6 months, acute rejection as a cause of graft failure, inadequate urine production in the first 24 hours, primary graft failure, graft thrombosis or surgical complication as a contributory cause of graft failure, and 1-year graft survival.

Those receiving a right kidney did have significant but small increases in rates of delayed graft function, as defined by the need for dialysis within 7 days of transplantation (5.7% vs. 4.2%), lack of decline in serum creatinine in the first 24 hours (19.7% vs. 16.4%), treatment for acute rejection within 1 year (12.7% vs. 11.8%), and graft thrombosis as the cause of graft failure (1.1% vs. 0.8%).

The Kaplan-Meier cumulative rate of graft survival was better for left kidneys than for right kidneys (P = .006), but "these are essentially superimposed numbers," said Dr. Taber, who disclosed no conflicts of interest related to the research.

The study had limitations, such as its retrospective design, lack of more detailed information about donor and recipient outcomes, and reliance on data as reported by centers, he acknowledged. Also, such large studies may pick up small differences that are not clinically meaningful.

"With ever-increasing demands for living donor transplantation, right-donor nephrectomies are being considered more often. Every effort should be made to leave the donor with the higher-functioning kidney, but at the same time maximizing the living donor pool," Dr. Taber concluded.

Dr. Taber disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM THE 2014 WORLD TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

Key clinical point: Choices of kidney to transplant may not need to hinge on left or right donor organ as a deciding factor.

Major Finding: Recipients of left and right kidneys were statistically indistinguishable with respect to hospital length of stay, treatment for acute rejection within 6 months, acute rejection as a cause of graft failure, inadequate urine production in the first 24 hours, and primary graft failure for acute rejection.

Data Source: A national retrospective cohort study of 58,599 adult living donor kidney transplants done during 2000-2009

Disclosures: Dr. Taber disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

Abstracts Presented at the 2014 AVAHO Annual Meeting

A new treatment strategy for high-risk MDS/AML

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Preclinical research has revealed a potential therapeutic strategy for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

In experiments with human cells and mouse models of del(5q) AML/MDS, researchers found that an NF-κB signaling network fueled the survival and growth of leukemic cells.

But the team could inhibit this network by targeting p62, thereby impeding leukemic cell expansion and inducing apoptosis.

Daniel Starczynowski PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues described this work in Cell Reports.

“Unfortunately, a large portion of del(5q) AML and MDS patients have an increased number of bone marrow blasts and additional chromosomal mutations,” Dr Starczynowski said.

“These patients have very poor prognosis because the disease is very resistant to available treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation. Finding new therapies is important, and this study identifies new therapeutic possibilities.”

Dr Starczynowski and his colleagues began this research by focusing on miR-146a, a microRNA previously shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS/AML.

The team found the loss of miR-146a in leukemic cells results in derepression of TRAF6, a mediator of NF-κB activation, which implicates this molecular complex in the aggressive nature of del(5q) MDS/AML.

So the researchers theorized that inhibiting the TRAF6/NF-κB axis might help treat aggressive forms of del(5q) MDS/AML with low miR-146a expression. The problem was that past attempts to directly inhibit NF-κB had not exactly proven successful.

Fortunately, chromosome deletions that target tumor suppressor genes also involve multiple neighboring genes. So the team examined the expression of all genes residing within chromosome 5q from del(5q) and control CD34+ cells, with the goal of finding a more suitable therapeutic target.

To determine which of the genes they identified are necessary for del(5q) leukemic cell function, the researchers knocked down each gene and examined leukemic progenitor function. They found that only knockdown of SQSTM1/p62 resulted in reduced colony formation.

So the team tested inhibition/knockdown of p62 as an experimental treatment strategy in miR-146alow MDS/AML cell lines, primary del(5q) AML samples, and mouse models of AML/MDS.

They found that targeting p62 reduced the number of leukemic cell colonies by 80% in human AML/MDS cells. And in mice, targeting p62 prevented the expansion of leukemic cells and significantly delayed mortality.

These results suggest that interfering with the p62-TRAF6 signaling complex represents a therapeutic option in miR-146a-deficient and aggressive del(5q) MDS/AML.

However, Dr Starczynowski noted that additional research is needed to further verify these findings and learn more about the molecular processes involved. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Preclinical research has revealed a potential therapeutic strategy for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

In experiments with human cells and mouse models of del(5q) AML/MDS, researchers found that an NF-κB signaling network fueled the survival and growth of leukemic cells.

But the team could inhibit this network by targeting p62, thereby impeding leukemic cell expansion and inducing apoptosis.

Daniel Starczynowski PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues described this work in Cell Reports.

“Unfortunately, a large portion of del(5q) AML and MDS patients have an increased number of bone marrow blasts and additional chromosomal mutations,” Dr Starczynowski said.

“These patients have very poor prognosis because the disease is very resistant to available treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation. Finding new therapies is important, and this study identifies new therapeutic possibilities.”

Dr Starczynowski and his colleagues began this research by focusing on miR-146a, a microRNA previously shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS/AML.

The team found the loss of miR-146a in leukemic cells results in derepression of TRAF6, a mediator of NF-κB activation, which implicates this molecular complex in the aggressive nature of del(5q) MDS/AML.

So the researchers theorized that inhibiting the TRAF6/NF-κB axis might help treat aggressive forms of del(5q) MDS/AML with low miR-146a expression. The problem was that past attempts to directly inhibit NF-κB had not exactly proven successful.

Fortunately, chromosome deletions that target tumor suppressor genes also involve multiple neighboring genes. So the team examined the expression of all genes residing within chromosome 5q from del(5q) and control CD34+ cells, with the goal of finding a more suitable therapeutic target.

To determine which of the genes they identified are necessary for del(5q) leukemic cell function, the researchers knocked down each gene and examined leukemic progenitor function. They found that only knockdown of SQSTM1/p62 resulted in reduced colony formation.

So the team tested inhibition/knockdown of p62 as an experimental treatment strategy in miR-146alow MDS/AML cell lines, primary del(5q) AML samples, and mouse models of AML/MDS.

They found that targeting p62 reduced the number of leukemic cell colonies by 80% in human AML/MDS cells. And in mice, targeting p62 prevented the expansion of leukemic cells and significantly delayed mortality.

These results suggest that interfering with the p62-TRAF6 signaling complex represents a therapeutic option in miR-146a-deficient and aggressive del(5q) MDS/AML.

However, Dr Starczynowski noted that additional research is needed to further verify these findings and learn more about the molecular processes involved. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

Preclinical research has revealed a potential therapeutic strategy for high-risk acute myeloid leukemia (AML) and myelodysplastic syndrome (MDS).

In experiments with human cells and mouse models of del(5q) AML/MDS, researchers found that an NF-κB signaling network fueled the survival and growth of leukemic cells.

But the team could inhibit this network by targeting p62, thereby impeding leukemic cell expansion and inducing apoptosis.

Daniel Starczynowski PhD, of Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center in Ohio, and his colleagues described this work in Cell Reports.

“Unfortunately, a large portion of del(5q) AML and MDS patients have an increased number of bone marrow blasts and additional chromosomal mutations,” Dr Starczynowski said.

“These patients have very poor prognosis because the disease is very resistant to available treatments such as chemotherapy and radiation. Finding new therapies is important, and this study identifies new therapeutic possibilities.”

Dr Starczynowski and his colleagues began this research by focusing on miR-146a, a microRNA previously shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of del(5q) MDS/AML.

The team found the loss of miR-146a in leukemic cells results in derepression of TRAF6, a mediator of NF-κB activation, which implicates this molecular complex in the aggressive nature of del(5q) MDS/AML.

So the researchers theorized that inhibiting the TRAF6/NF-κB axis might help treat aggressive forms of del(5q) MDS/AML with low miR-146a expression. The problem was that past attempts to directly inhibit NF-κB had not exactly proven successful.

Fortunately, chromosome deletions that target tumor suppressor genes also involve multiple neighboring genes. So the team examined the expression of all genes residing within chromosome 5q from del(5q) and control CD34+ cells, with the goal of finding a more suitable therapeutic target.

To determine which of the genes they identified are necessary for del(5q) leukemic cell function, the researchers knocked down each gene and examined leukemic progenitor function. They found that only knockdown of SQSTM1/p62 resulted in reduced colony formation.

So the team tested inhibition/knockdown of p62 as an experimental treatment strategy in miR-146alow MDS/AML cell lines, primary del(5q) AML samples, and mouse models of AML/MDS.

They found that targeting p62 reduced the number of leukemic cell colonies by 80% in human AML/MDS cells. And in mice, targeting p62 prevented the expansion of leukemic cells and significantly delayed mortality.

These results suggest that interfering with the p62-TRAF6 signaling complex represents a therapeutic option in miR-146a-deficient and aggressive del(5q) MDS/AML.

However, Dr Starczynowski noted that additional research is needed to further verify these findings and learn more about the molecular processes involved. ![]()

Regimen confers PFS benefit in newly diagnosed MM

Credit: CDC

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, a regimen of continuous lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone conferred the greatest progression-free survival (PFS) benefit among patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received this regimen had a significantly longer median PFS than patients who received a fixed course of lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide.

Results of this study appear in The New England Journal of Medicine. The research was previously presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Hôpital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this study. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), to 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or to melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and with Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 35.0 months with continuous Rd compared with 22.3 months for MPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001) and 22.1 months for Rd18 (HR=0.60, P<0.001).

The median time to disease progression was 32.5 months for patients receiving continuous Rd compared with 23.9 months (HR=0.68, P<0.001) for MPT and 21.9 months for Rd18 (HR=0.62, P<0.001).

The median PFS was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT. This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (HR=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival demonstrated a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

At the time of the analysis (May 24, 2013), 23% of patients in the continuous Rd arm were still on therapy.

Grade 3/4 adverse events that occurred in at least 8% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, Rd18 arm, or MPT arm included neutropenia (28%, 26%, 45%, respectively), anemia (18%, 16%, 19%), thrombocytopenia (8%, 8%,11%), febrile neutropenia (1%, 3%, 3%), leukopenia (5%, 6%, 10%), infection (29%, 22%, 17%), pneumonia (8%, 8%, 6%), deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (8%, 6%, 5%), asthenia (8%, 6%, 6%), fatigue (7%, 9%, 6%), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (1%, <1%, 9%).

Grade 3/4 cardiac disorders occurred in 12% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, 7% in the Rd18 arm, and 9% in the MPT arm.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm. ![]()

Credit: CDC

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, a regimen of continuous lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone conferred the greatest progression-free survival (PFS) benefit among patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received this regimen had a significantly longer median PFS than patients who received a fixed course of lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide.

Results of this study appear in The New England Journal of Medicine. The research was previously presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Hôpital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this study. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), to 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or to melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and with Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 35.0 months with continuous Rd compared with 22.3 months for MPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001) and 22.1 months for Rd18 (HR=0.60, P<0.001).

The median time to disease progression was 32.5 months for patients receiving continuous Rd compared with 23.9 months (HR=0.68, P<0.001) for MPT and 21.9 months for Rd18 (HR=0.62, P<0.001).

The median PFS was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT. This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (HR=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival demonstrated a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

At the time of the analysis (May 24, 2013), 23% of patients in the continuous Rd arm were still on therapy.

Grade 3/4 adverse events that occurred in at least 8% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, Rd18 arm, or MPT arm included neutropenia (28%, 26%, 45%, respectively), anemia (18%, 16%, 19%), thrombocytopenia (8%, 8%,11%), febrile neutropenia (1%, 3%, 3%), leukopenia (5%, 6%, 10%), infection (29%, 22%, 17%), pneumonia (8%, 8%, 6%), deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (8%, 6%, 5%), asthenia (8%, 6%, 6%), fatigue (7%, 9%, 6%), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (1%, <1%, 9%).

Grade 3/4 cardiac disorders occurred in 12% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, 7% in the Rd18 arm, and 9% in the MPT arm.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm. ![]()

Credit: CDC

In the phase 3 FIRST trial, a regimen of continuous lenalidomide and low-dose dexamethasone conferred the greatest progression-free survival (PFS) benefit among patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (MM).

Patients who received this regimen had a significantly longer median PFS than patients who received a fixed course of lenalidomide plus low-dose dexamethasone or a combination of melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide.

Results of this study appear in The New England Journal of Medicine. The research was previously presented at the 2013 ASH Annual Meeting. The study was supported by Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome and Celgene Corporation, the makers of lenalidomide.

Thierry Facon, MD, of Hôpital Claude Huriez in Lille, France, and his colleagues enrolled 1623 patients on this study. They were newly diagnosed with MM and not eligible for stem cell transplant.

Patients were randomized to receive lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd) in 28-day cycles until disease progression (n=535), to 18 cycles of lenalidomide and dexamethasone (Rd18) for 72 weeks (n=541), or to melphalan, prednisone, and thalidomide (MPT) for 72 weeks (n=547).

Response rates were significantly better with continuous Rd (75%) and with Rd18 (73%) than with MPT (62%, P<0.001 for both comparisons). Complete response rates were 15%, 14%, and 9%, respectively.

The median duration of response was 35.0 months with continuous Rd compared with 22.3 months for MPT (hazard ratio [HR]=0.63, P<0.001) and 22.1 months for Rd18 (HR=0.60, P<0.001).

The median time to disease progression was 32.5 months for patients receiving continuous Rd compared with 23.9 months (HR=0.68, P<0.001) for MPT and 21.9 months for Rd18 (HR=0.62, P<0.001).

The median PFS was 25.5 months with continuous Rd, 20.7 months with Rd18, and 21.2 months with MPT. This resulted in a 28% reduction in the risk of progression or death for patients treated with continuous Rd compared with those treated with MPT (HR=0.72, P<0.001) and a 30% reduction compared with Rd18 (HR=0.70, P<0.001).

The pre-planned interim analysis of overall survival demonstrated a 22% reduction in the risk of death for continuous Rd vs MPT (HR=0.78, P=0.02), but the difference did not cross the pre-specified superiority boundary (P<0.0096).

At the time of the analysis (May 24, 2013), 23% of patients in the continuous Rd arm were still on therapy.

Grade 3/4 adverse events that occurred in at least 8% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, Rd18 arm, or MPT arm included neutropenia (28%, 26%, 45%, respectively), anemia (18%, 16%, 19%), thrombocytopenia (8%, 8%,11%), febrile neutropenia (1%, 3%, 3%), leukopenia (5%, 6%, 10%), infection (29%, 22%, 17%), pneumonia (8%, 8%, 6%), deep vein thrombosis and/or pulmonary embolism (8%, 6%, 5%), asthenia (8%, 6%, 6%), fatigue (7%, 9%, 6%), and peripheral sensory neuropathy (1%, <1%, 9%).

Grade 3/4 cardiac disorders occurred in 12% of patients in the continuous Rd arm, 7% in the Rd18 arm, and 9% in the MPT arm.

The incidence of invasive second primary malignancies was 3% in patients taking continuous Rd, 6% in patients taking Rd18, and 5% in those taking MPT. The overall incidence of solid tumors was identical in the continuous Rd and MPT arms (3%) and 5% in the Rd18 arm. ![]()

Deaths from childhood cancer on decline in UK

Credit: Logan Tuttle

The rate of children dying from cancer in the UK has dropped 22% in the last decade, according to new figures published by Cancer Research UK.

From 2001 to 2003, 328 children died from cancer each year. But from 2010 to 2012, the annual death toll from childhood cancers decreased to 258.

The steepest decline in mortality was among leukemia patients. Death rates across all forms of leukemia combined dropped by 47%, from 102 to 53 deaths each year.

For acute lymphoblastic leukemia, the annual mortality rate decreased by 52%, falling from 63 to 29 deaths per year. For acute myeloid leukemia, the death rate fell by 33%, from 30 to 20 deaths per year. And for chronic myeloid leukemia, the death rate decreased by 74%, from 2 deaths per year to 1.

Annual mortality rates decreased for lymphoma patients as well. For all lymphomas, the death rate decreased by 31%, falling from 15 to 11 deaths per year. And for non-Hodgkin lymphomas, the rate dropped 35%, from 14 to 10 deaths per year.

Much of this success is due to new combinations of chemotherapy drugs, but efforts to improve imaging and radiotherapy techniques has also played a part, according to Cancer Research UK.

“It’s very encouraging to see that fewer children are dying of cancer, but a lot more needs to be done,” said Pam Kearns, director of the Cancer Research UK Clinical Trials Unit in Birmingham.

“Many children who survive cancer will live with the long-term side effects of their treatment that can have an impact throughout their adult lives, so it’s vital that we find kinder and even more effective treatments for them.”