User login

Paclitaxel-Associated Melanonychia

To the Editor:

Taxane-based chemotherapy including paclitaxel and docetaxel is commonly used to treat solid tumor malignancies including lung, breast, ovarian, and bladder cancers.1 Taxanes work by interrupting normal microtubule function by inducing tubulin polymerization and inhibiting microtubule depolymerization, thereby leading to cell cycle arrest at the gap 2 (premitotic) and mitotic phase and the blockade of cell division.2

Cutaneous side effects have been reported with taxane-based therapies, including alopecia, skin rash and erythema, and desquamation of the hands and feet (hand-foot syndrome).3 Nail changes also have been reported to occur in 0% to 44% of treated patients,4 with one study reporting an incidence as high as 50.5%.5 Nail abnormalities that have been described primarily include onycholysis, and less frequently Beau lines, subungual hemorrhagic bullae, subungual hyperkeratosis, splinter hemorrhages, acute paronychia, and pigmentary changes such as nail bed dyschromia. Among the taxanes, nail abnormalities are more commonly seen with docetaxel; few reports address paclitaxel-induced nail changes.4 Onycholysis, diffuse fingernail orange discoloration, Beau lines, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and brown discoloration of 3 fingernail beds sparing the lunula have been reported with paclitaxel.6-9 We report a unique case of paclitaxel-associated melanonychia.

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of multiple myeloma and breast cancer who was being treated with paclitaxel for breast cancer presented with nail changes including nail darkening since initiating paclitaxel. She was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2010 and received bortezomib, dexamethasone, and an autologous stem cell transplant in August 2011. She never achieved complete remission but had been on lenalidomide with stable disease. She underwent a lumpectomy in December 2012, which revealed intraductal carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in situ that was estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative and ERBB2 (formerly HER2) positive. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) to complete 12 cycles and trastuzumab (6 mg/kg) every 3 weeks. While on paclitaxel, she developed grade 2 neuropathy of the hands, leading to subsequent dose reduction at week 9. She denied any other changes to her medications. On clinical examination she had diffuse and well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis involving all 20 nails (Figure, A and B). A nail clipping of the right hallux nail was sent for analysis. Pathology results showed evidence of scattered clusters of brown melanin pigment in the nail plate. Periodic acid–Schiff staining revealed numerous yeasts at the nail base but no infiltrating hyphae. Iron stain was negative for hemosiderin. The right index finger was injected with triamcinolone acetonide to treat the onycholysis. Four months after completing the paclitaxel, she began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in all nails (Figure, C and D).

|

| |

|

|

Initial appearance of diffuse, well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (A) and left hand (B). Four months after completing paclitaxel, the patient began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (C) and left hand (D). |

The highly proliferating cells that comprise the nail matrix epithelium mature, differentiate, and keratinize to form the nail plate and are susceptible to the antimitotic effects of systemic chemotherapy. As a result, systemic chemotherapies may lead to abnormal nail plate production and keratinization of the nail plate, causing the clinical manifestations of Beau lines, onychomadesis, and leukonychia.10

Melanonychia is the development of melanin pigmentation of the nail plate and is typically caused by matrix melanin deposition through the activation of nail matrix melanocytes. There are 3 patterns of melanonychia: longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse. A single nail plate can involve more than one pattern of melanonychia and several nails may be affected. Longitudinal melanonychia typically develops from the activation of a group of melanocytes in the nail matrix, while diffuse pigmentation arises from diffuse melanocyte activation.11 Longitudinal melanonychia is common in darker-pigmented individuals12 and can be associated with systemic diseases.10 Transverse melanonychia has been reported in association with medications including many chemotherapy agents, and each band of transverse melanonychia may correspond to a cycle of therapy.11 Drug-induced melanonychia can affect several nails and tends to resolve after completion of therapy. Melanonychia has previously been described with vincristine, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, dacarbazine, methotrexate, and electron beam therapy.11 Nail pigmentation changes have been reported with docetaxel; a patient developed blue discoloration on the right and left thumb lunulae that improved 3 months after discontinuation of docetaxel therapy.13 While on docetaxel, another patient developed acral erythema, onycholysis, and longitudinal melanonychia in photoexposed areas, which was thought to be secondary to possible photosensitization.14 Possible explanations for paclitaxel-induced melanonychia include a direct toxic effect on the nail bed or nail matrix, focal stimulation of nail matrix melanocytes, or photosensitization. Drug-induced melanonychia commonly appears 3 to 8 weeks after drug intake and typically resolves 6 to 8 weeks after drug discontinuation.15

Predictors of taxane-related nail changes have been studied.5 Taxane-induced nail toxicity was more prevalent in patients who were female, had a history of diabetes mellitus, had received capecitabine with docetaxel, and had a diagnosis of breast or gynecological cancer. The nail changes increased with greater number of taxane cycles administered, body mass index, and severity of treatment-related neuropathy.5 Although nail changes often are temporary and typically resolve with drug withdrawal, they may persist in some patients.16 Possible measures have been proposed to prevent taxane-induced nail toxicity including frozen gloves,17 nail cutting, and avoiding potential fingernail irritants.18

It is possible that the nails of our darker-skinned patient may have been affected by some degree of melanonychia prior to starting the therapy, which cannot be ruled out. However, according to the patient, she only noticed the change after starting paclitaxel, raising the possibility of either new, worsening, or more diffuse involvement following initiation of paclitaxel therapy. Additionally, she was receiving weekly administration of paclitaxel and experienced severe neuropathy, both predictors of nail toxicity.5 No reports of melanonychia from lenalidomide have been reported in the literature indexed for MEDLINE. Although these nail changes are not life threatening, clinicians should be aware of these side effects, as they are cosmetically distressing to many patients and can impact quality of life.19

1. Crown J, O’Leary M. The taxanes: an update. Lancet. 2000;356:507-508.

2. Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by Taxol. Nature. 1979;277:665-667.

3. Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:545-570.

4. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

5. Can G, Aydiner A, Cavdar I. Taxane-induced nail changes: predictors and efficacy of the use of frozen gloves and socks in the prevention of nail toxicity. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:270-275.

6. Lüftner D, Flath B, Akrivakis C, et al. Dose-intensified weekly paclitaxel induces multiple nail disorders. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1139-1141.

7. Hussain S, Anderson DN, Salvatti ME, et al. Onycholysis as a complication of systemic chemotherapy. report of five cases associated with prolonged weekly paclitaxel therapy and review of the literature. Cancer. 2000;88:2367-2371.

8. Almagro M, Del Pozo J, Garcia-Silva J, et al. Nail alterations secondary to paclitaxel therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:146-147.

9. Flory SM, Solimando DA Jr, Webster GF, et al. Onycholysis associated with weekly administration of paclitaxel. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:584-586.

10. Hinds G, Thomas VD. Malignancy and cancer treatment-related hair and nail changes. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:59-68.

11. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Practice. 2009;15:143-55.

12. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

13. Halvorson CR, Erickson CL, Gaspari AA. A rare manifestation of nail changes with docetaxel therapy. Skinmed. 2010;8:179-180.

14. Ferreira O, Baudrier T, Mota A, et al. Docetaxel-induced acral erythema and nail changes distributed to photoexposed areas. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2010;29:296-299.

15. Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Drug reactions affecting the nail unit: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:215-221.

16. Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail disorders: incidence, management and prognosis. Drug Saf. 1999;21:187-201.

17. Scotté F, Tourani JM, Banu E, et al. Multicenter study of a frozen glove to prevent docetaxel-induced onycholysis and cutaneous toxicity of the hand. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4424-4429.

18. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2009;15:143-155.

19. Hackbarth M, Haas N, Fotopoulou C, et al. Chemotherapy-induced dermatological toxicity: frequencies and impact on quality of life in women’s cancers. results of a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:267-273.

To the Editor:

Taxane-based chemotherapy including paclitaxel and docetaxel is commonly used to treat solid tumor malignancies including lung, breast, ovarian, and bladder cancers.1 Taxanes work by interrupting normal microtubule function by inducing tubulin polymerization and inhibiting microtubule depolymerization, thereby leading to cell cycle arrest at the gap 2 (premitotic) and mitotic phase and the blockade of cell division.2

Cutaneous side effects have been reported with taxane-based therapies, including alopecia, skin rash and erythema, and desquamation of the hands and feet (hand-foot syndrome).3 Nail changes also have been reported to occur in 0% to 44% of treated patients,4 with one study reporting an incidence as high as 50.5%.5 Nail abnormalities that have been described primarily include onycholysis, and less frequently Beau lines, subungual hemorrhagic bullae, subungual hyperkeratosis, splinter hemorrhages, acute paronychia, and pigmentary changes such as nail bed dyschromia. Among the taxanes, nail abnormalities are more commonly seen with docetaxel; few reports address paclitaxel-induced nail changes.4 Onycholysis, diffuse fingernail orange discoloration, Beau lines, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and brown discoloration of 3 fingernail beds sparing the lunula have been reported with paclitaxel.6-9 We report a unique case of paclitaxel-associated melanonychia.

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of multiple myeloma and breast cancer who was being treated with paclitaxel for breast cancer presented with nail changes including nail darkening since initiating paclitaxel. She was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2010 and received bortezomib, dexamethasone, and an autologous stem cell transplant in August 2011. She never achieved complete remission but had been on lenalidomide with stable disease. She underwent a lumpectomy in December 2012, which revealed intraductal carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in situ that was estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative and ERBB2 (formerly HER2) positive. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) to complete 12 cycles and trastuzumab (6 mg/kg) every 3 weeks. While on paclitaxel, she developed grade 2 neuropathy of the hands, leading to subsequent dose reduction at week 9. She denied any other changes to her medications. On clinical examination she had diffuse and well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis involving all 20 nails (Figure, A and B). A nail clipping of the right hallux nail was sent for analysis. Pathology results showed evidence of scattered clusters of brown melanin pigment in the nail plate. Periodic acid–Schiff staining revealed numerous yeasts at the nail base but no infiltrating hyphae. Iron stain was negative for hemosiderin. The right index finger was injected with triamcinolone acetonide to treat the onycholysis. Four months after completing the paclitaxel, she began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in all nails (Figure, C and D).

|

| |

|

|

Initial appearance of diffuse, well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (A) and left hand (B). Four months after completing paclitaxel, the patient began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (C) and left hand (D). |

The highly proliferating cells that comprise the nail matrix epithelium mature, differentiate, and keratinize to form the nail plate and are susceptible to the antimitotic effects of systemic chemotherapy. As a result, systemic chemotherapies may lead to abnormal nail plate production and keratinization of the nail plate, causing the clinical manifestations of Beau lines, onychomadesis, and leukonychia.10

Melanonychia is the development of melanin pigmentation of the nail plate and is typically caused by matrix melanin deposition through the activation of nail matrix melanocytes. There are 3 patterns of melanonychia: longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse. A single nail plate can involve more than one pattern of melanonychia and several nails may be affected. Longitudinal melanonychia typically develops from the activation of a group of melanocytes in the nail matrix, while diffuse pigmentation arises from diffuse melanocyte activation.11 Longitudinal melanonychia is common in darker-pigmented individuals12 and can be associated with systemic diseases.10 Transverse melanonychia has been reported in association with medications including many chemotherapy agents, and each band of transverse melanonychia may correspond to a cycle of therapy.11 Drug-induced melanonychia can affect several nails and tends to resolve after completion of therapy. Melanonychia has previously been described with vincristine, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, dacarbazine, methotrexate, and electron beam therapy.11 Nail pigmentation changes have been reported with docetaxel; a patient developed blue discoloration on the right and left thumb lunulae that improved 3 months after discontinuation of docetaxel therapy.13 While on docetaxel, another patient developed acral erythema, onycholysis, and longitudinal melanonychia in photoexposed areas, which was thought to be secondary to possible photosensitization.14 Possible explanations for paclitaxel-induced melanonychia include a direct toxic effect on the nail bed or nail matrix, focal stimulation of nail matrix melanocytes, or photosensitization. Drug-induced melanonychia commonly appears 3 to 8 weeks after drug intake and typically resolves 6 to 8 weeks after drug discontinuation.15

Predictors of taxane-related nail changes have been studied.5 Taxane-induced nail toxicity was more prevalent in patients who were female, had a history of diabetes mellitus, had received capecitabine with docetaxel, and had a diagnosis of breast or gynecological cancer. The nail changes increased with greater number of taxane cycles administered, body mass index, and severity of treatment-related neuropathy.5 Although nail changes often are temporary and typically resolve with drug withdrawal, they may persist in some patients.16 Possible measures have been proposed to prevent taxane-induced nail toxicity including frozen gloves,17 nail cutting, and avoiding potential fingernail irritants.18

It is possible that the nails of our darker-skinned patient may have been affected by some degree of melanonychia prior to starting the therapy, which cannot be ruled out. However, according to the patient, she only noticed the change after starting paclitaxel, raising the possibility of either new, worsening, or more diffuse involvement following initiation of paclitaxel therapy. Additionally, she was receiving weekly administration of paclitaxel and experienced severe neuropathy, both predictors of nail toxicity.5 No reports of melanonychia from lenalidomide have been reported in the literature indexed for MEDLINE. Although these nail changes are not life threatening, clinicians should be aware of these side effects, as they are cosmetically distressing to many patients and can impact quality of life.19

To the Editor:

Taxane-based chemotherapy including paclitaxel and docetaxel is commonly used to treat solid tumor malignancies including lung, breast, ovarian, and bladder cancers.1 Taxanes work by interrupting normal microtubule function by inducing tubulin polymerization and inhibiting microtubule depolymerization, thereby leading to cell cycle arrest at the gap 2 (premitotic) and mitotic phase and the blockade of cell division.2

Cutaneous side effects have been reported with taxane-based therapies, including alopecia, skin rash and erythema, and desquamation of the hands and feet (hand-foot syndrome).3 Nail changes also have been reported to occur in 0% to 44% of treated patients,4 with one study reporting an incidence as high as 50.5%.5 Nail abnormalities that have been described primarily include onycholysis, and less frequently Beau lines, subungual hemorrhagic bullae, subungual hyperkeratosis, splinter hemorrhages, acute paronychia, and pigmentary changes such as nail bed dyschromia. Among the taxanes, nail abnormalities are more commonly seen with docetaxel; few reports address paclitaxel-induced nail changes.4 Onycholysis, diffuse fingernail orange discoloration, Beau lines, subungual distal hyperkeratosis, and brown discoloration of 3 fingernail beds sparing the lunula have been reported with paclitaxel.6-9 We report a unique case of paclitaxel-associated melanonychia.

A 54-year-old black woman with a history of multiple myeloma and breast cancer who was being treated with paclitaxel for breast cancer presented with nail changes including nail darkening since initiating paclitaxel. She was diagnosed with multiple myeloma in 2010 and received bortezomib, dexamethasone, and an autologous stem cell transplant in August 2011. She never achieved complete remission but had been on lenalidomide with stable disease. She underwent a lumpectomy in December 2012, which revealed intraductal carcinoma with ductal carcinoma in situ that was estrogen receptor and progesterone receptor negative and ERBB2 (formerly HER2) positive. She was started on weekly paclitaxel (80 mg/m2) to complete 12 cycles and trastuzumab (6 mg/kg) every 3 weeks. While on paclitaxel, she developed grade 2 neuropathy of the hands, leading to subsequent dose reduction at week 9. She denied any other changes to her medications. On clinical examination she had diffuse and well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis involving all 20 nails (Figure, A and B). A nail clipping of the right hallux nail was sent for analysis. Pathology results showed evidence of scattered clusters of brown melanin pigment in the nail plate. Periodic acid–Schiff staining revealed numerous yeasts at the nail base but no infiltrating hyphae. Iron stain was negative for hemosiderin. The right index finger was injected with triamcinolone acetonide to treat the onycholysis. Four months after completing the paclitaxel, she began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in all nails (Figure, C and D).

|

| |

|

|

Initial appearance of diffuse, well-demarcated, brown-black, longitudinal and transverse bands beginning at the proximal nail plate and progressing distally, with onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (A) and left hand (B). Four months after completing paclitaxel, the patient began to notice lightening of the nails and improvement of the onycholysis in the nails on the right hand (C) and left hand (D). |

The highly proliferating cells that comprise the nail matrix epithelium mature, differentiate, and keratinize to form the nail plate and are susceptible to the antimitotic effects of systemic chemotherapy. As a result, systemic chemotherapies may lead to abnormal nail plate production and keratinization of the nail plate, causing the clinical manifestations of Beau lines, onychomadesis, and leukonychia.10

Melanonychia is the development of melanin pigmentation of the nail plate and is typically caused by matrix melanin deposition through the activation of nail matrix melanocytes. There are 3 patterns of melanonychia: longitudinal, transverse, and diffuse. A single nail plate can involve more than one pattern of melanonychia and several nails may be affected. Longitudinal melanonychia typically develops from the activation of a group of melanocytes in the nail matrix, while diffuse pigmentation arises from diffuse melanocyte activation.11 Longitudinal melanonychia is common in darker-pigmented individuals12 and can be associated with systemic diseases.10 Transverse melanonychia has been reported in association with medications including many chemotherapy agents, and each band of transverse melanonychia may correspond to a cycle of therapy.11 Drug-induced melanonychia can affect several nails and tends to resolve after completion of therapy. Melanonychia has previously been described with vincristine, doxorubicin, hydroxyurea, cyclophosphamide, 5-fluorouracil, bleomycin, dacarbazine, methotrexate, and electron beam therapy.11 Nail pigmentation changes have been reported with docetaxel; a patient developed blue discoloration on the right and left thumb lunulae that improved 3 months after discontinuation of docetaxel therapy.13 While on docetaxel, another patient developed acral erythema, onycholysis, and longitudinal melanonychia in photoexposed areas, which was thought to be secondary to possible photosensitization.14 Possible explanations for paclitaxel-induced melanonychia include a direct toxic effect on the nail bed or nail matrix, focal stimulation of nail matrix melanocytes, or photosensitization. Drug-induced melanonychia commonly appears 3 to 8 weeks after drug intake and typically resolves 6 to 8 weeks after drug discontinuation.15

Predictors of taxane-related nail changes have been studied.5 Taxane-induced nail toxicity was more prevalent in patients who were female, had a history of diabetes mellitus, had received capecitabine with docetaxel, and had a diagnosis of breast or gynecological cancer. The nail changes increased with greater number of taxane cycles administered, body mass index, and severity of treatment-related neuropathy.5 Although nail changes often are temporary and typically resolve with drug withdrawal, they may persist in some patients.16 Possible measures have been proposed to prevent taxane-induced nail toxicity including frozen gloves,17 nail cutting, and avoiding potential fingernail irritants.18

It is possible that the nails of our darker-skinned patient may have been affected by some degree of melanonychia prior to starting the therapy, which cannot be ruled out. However, according to the patient, she only noticed the change after starting paclitaxel, raising the possibility of either new, worsening, or more diffuse involvement following initiation of paclitaxel therapy. Additionally, she was receiving weekly administration of paclitaxel and experienced severe neuropathy, both predictors of nail toxicity.5 No reports of melanonychia from lenalidomide have been reported in the literature indexed for MEDLINE. Although these nail changes are not life threatening, clinicians should be aware of these side effects, as they are cosmetically distressing to many patients and can impact quality of life.19

1. Crown J, O’Leary M. The taxanes: an update. Lancet. 2000;356:507-508.

2. Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by Taxol. Nature. 1979;277:665-667.

3. Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:545-570.

4. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

5. Can G, Aydiner A, Cavdar I. Taxane-induced nail changes: predictors and efficacy of the use of frozen gloves and socks in the prevention of nail toxicity. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:270-275.

6. Lüftner D, Flath B, Akrivakis C, et al. Dose-intensified weekly paclitaxel induces multiple nail disorders. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1139-1141.

7. Hussain S, Anderson DN, Salvatti ME, et al. Onycholysis as a complication of systemic chemotherapy. report of five cases associated with prolonged weekly paclitaxel therapy and review of the literature. Cancer. 2000;88:2367-2371.

8. Almagro M, Del Pozo J, Garcia-Silva J, et al. Nail alterations secondary to paclitaxel therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:146-147.

9. Flory SM, Solimando DA Jr, Webster GF, et al. Onycholysis associated with weekly administration of paclitaxel. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:584-586.

10. Hinds G, Thomas VD. Malignancy and cancer treatment-related hair and nail changes. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:59-68.

11. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Practice. 2009;15:143-55.

12. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

13. Halvorson CR, Erickson CL, Gaspari AA. A rare manifestation of nail changes with docetaxel therapy. Skinmed. 2010;8:179-180.

14. Ferreira O, Baudrier T, Mota A, et al. Docetaxel-induced acral erythema and nail changes distributed to photoexposed areas. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2010;29:296-299.

15. Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Drug reactions affecting the nail unit: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:215-221.

16. Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail disorders: incidence, management and prognosis. Drug Saf. 1999;21:187-201.

17. Scotté F, Tourani JM, Banu E, et al. Multicenter study of a frozen glove to prevent docetaxel-induced onycholysis and cutaneous toxicity of the hand. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4424-4429.

18. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2009;15:143-155.

19. Hackbarth M, Haas N, Fotopoulou C, et al. Chemotherapy-induced dermatological toxicity: frequencies and impact on quality of life in women’s cancers. results of a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:267-273.

1. Crown J, O’Leary M. The taxanes: an update. Lancet. 2000;356:507-508.

2. Schiff PB, Fant J, Horwitz SB. Promotion of microtubule assembly in vitro by Taxol. Nature. 1979;277:665-667.

3. Heidary N, Naik H, Burgin S. Chemotherapeutic agents and the skin: an update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2008;58:545-570.

4. Minisini AM, Tosti A, Sobrero AF, et al. Taxane-induced nail changes: incidence, clinical presentation and outcome. Ann Oncol. 2003;14:333-337.

5. Can G, Aydiner A, Cavdar I. Taxane-induced nail changes: predictors and efficacy of the use of frozen gloves and socks in the prevention of nail toxicity. Eur J Oncol Nurs. 2012;16:270-275.

6. Lüftner D, Flath B, Akrivakis C, et al. Dose-intensified weekly paclitaxel induces multiple nail disorders. Ann Oncol. 1998;9:1139-1141.

7. Hussain S, Anderson DN, Salvatti ME, et al. Onycholysis as a complication of systemic chemotherapy. report of five cases associated with prolonged weekly paclitaxel therapy and review of the literature. Cancer. 2000;88:2367-2371.

8. Almagro M, Del Pozo J, Garcia-Silva J, et al. Nail alterations secondary to paclitaxel therapy. Eur J Dermatol. 2000;10:146-147.

9. Flory SM, Solimando DA Jr, Webster GF, et al. Onycholysis associated with weekly administration of paclitaxel. Ann Pharmacother. 1999;33:584-586.

10. Hinds G, Thomas VD. Malignancy and cancer treatment-related hair and nail changes. Dermatol Clin. 2008;26:59-68.

11. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Practice. 2009;15:143-55.

12. Buka R, Friedman KA, Phelps RG, et al. Childhood longitudinal melanonychia: case reports and review of the literature. Mt Sinai J Med. 2001;68:331-335.

13. Halvorson CR, Erickson CL, Gaspari AA. A rare manifestation of nail changes with docetaxel therapy. Skinmed. 2010;8:179-180.

14. Ferreira O, Baudrier T, Mota A, et al. Docetaxel-induced acral erythema and nail changes distributed to photoexposed areas. Cutan Ocul Toxicol. 2010;29:296-299.

15. Piraccini BM, Iorizzo M. Drug reactions affecting the nail unit: diagnosis and management. Dermatol Clin. 2007;25:215-221.

16. Piraccini BM, Tosti A. Drug-induced nail disorders: incidence, management and prognosis. Drug Saf. 1999;21:187-201.

17. Scotté F, Tourani JM, Banu E, et al. Multicenter study of a frozen glove to prevent docetaxel-induced onycholysis and cutaneous toxicity of the hand. J Clin Oncol. 2005;23:4424-4429.

18. Gilbar P, Hain A, Peereboom VM. Nail toxicity induced by cancer chemotherapy. J Oncol Pharm Pract. 2009;15:143-155.

19. Hackbarth M, Haas N, Fotopoulou C, et al. Chemotherapy-induced dermatological toxicity: frequencies and impact on quality of life in women’s cancers. results of a prospective study. Support Care Cancer. 2008;16:267-273.

Verrucous Kaposi Sarcoma in an HIV-Positive Man

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

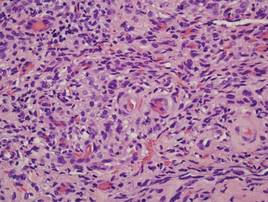

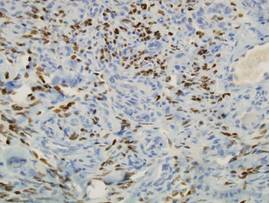

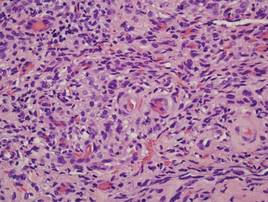

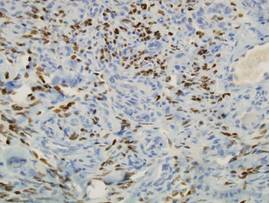

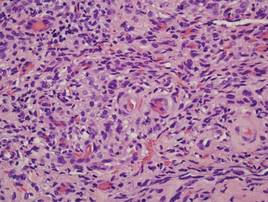

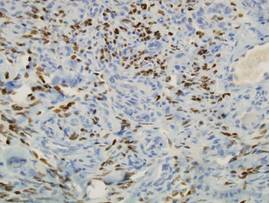

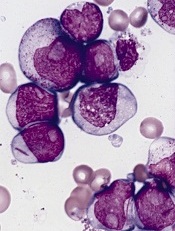

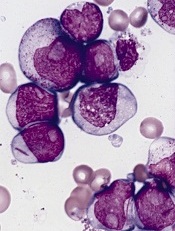

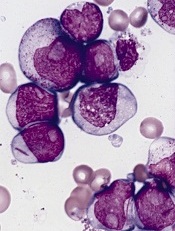

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

To the Editor:

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma (VKS) is an uncommon variant of Kaposi sarcoma (KS) that rarely is seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature. It is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1 We present a case of VKS in a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)–positive man with cutaneous lesions that demonstrated minimal response to treatment with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, doxorubicin, paclitaxel, and alitretinoin.

A 48-year-old man with a history of untreated HIV presented with a persistent eruption of heavily scaled, hyperpigmented, nonindurated, thin plaques in an ichthyosiform pattern on the bilateral lower legs and ankles of 4 years’ duration (Figure 1). He also had a number of soft, compressible, cystlike plaques without much overlying epidermal change on the lower extremities. He denied any prior episodes of skin breakdown, drainage, or secondary infection. Findings from the physical examination were otherwise unremarkable.

Two punch biopsies were performed on the lower legs, one from a scaly plaque and the other from a cystic area. The epidermis was hyperkeratotic and mildly hyperplastic with slitlike vascular spaces. A dense cellular proliferation of spindle-shaped cells was present in the dermis (Figure 2). Minimal cytologic atypia was noted. Immunohistochemical staining for human herpesvirus 8 (HHV-8) was strongly positive (Figure 3). Histologically, the cutaneous lesions were consistent with VKS.

At the current presentation, the CD4 count was 355 cells/mm3 and the viral load was 919,223 copies/mL. The CD4 count and viral load initially had been responsive to efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir therapy; 17 months prior to the current presentation, the CD4 count was 692 cells/mm3 and the viral load was less than 50 copies/mL. However, the cutaneous lesions persisted despite therapy with efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir, alitretinoin gel, and intralesional chemotherapeutic agents such as doxorubicin and paclitaxel.

Kaposi sarcoma, first described by Moritz Kaposi in 1872, represents a group of vascular neoplasms. Multiple subtypes have been described including classic, African endemic, transplant/AIDS associated, anaplastic, lymphedematous, hyperkeratotic/verrucous, keloidal, micronodular, pyogenic granulomalike, ecchymotic, and intravascular.1-3 Human herpesvirus 8 is associated with all clinical subtypes of KS.3 Immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1 has been shown in the literature to be highly sensitive and specific for KS and can potentially facilitate the diagnosis of KS among patients with similarly appearing dermatologic conditions, such as angiosarcoma, kaposiform hemangioendothelioma, or verrucous hemangioma.1,4 Human herpesvirus 8 infects endothelial cells and induces the proliferation of vascular spindle cells via the secretion of basic fibroblast growth factor and vascular endothelial growth factor.5 Human herpesvirus 8 also can lead to lymph vessel obstruction and lymph node enlargement by infecting cells within the lymphatic system. In addition, chronic lymphedema can itself lead to verruciform epidermal hyperplasia and hyperkeratosis, which has a clinical presentation similar to VKS.1

AIDS-associated KS typically starts as 1 or more purple-red macules that rapidly progress into papules, nodules, and plaques.1 These lesions have a predilection for the head, neck, trunk, and mucous membranes. Albeit a rare presentation, VKS is strongly associated with lymphedema in patients with AIDS.1,3,5 Previously, KS was often the presenting clinical manifestation of HIV infection, but since the use of highly active antiretroviral therapy (HAART) has become the standard of care, the incidence as well as the morbidity and mortality associated with KS has substantially decreased.1,5-7 Notably, in HIV patients who initially do not have signs or symptoms of KS, HHV-8 positivity is predictive of the development of KS within 2 to 4 years.6

In the literature, good prognostic indicators for KS include CD4 count greater than 150 cells/mm3, only cutaneous involvement, and negative B symptoms (eg, temperature >38°C, night sweats, unintentional weight loss >10% of normal body weight within 6 months).7 Kaposi sarcoma cannot be completely cured but can be appropriately managed with medical intervention. All KS subtypes are sensitive to radiation therapy; recalcitrant localized lesions can be treated with excision, cryotherapy, alitretinoin gel, laser ablation, or locally injected interferon or chemotherapeutic agents (eg, vincristine, vinblastine, actinomycin D).5,6 Liposomal anthracyclines (doxorubicin) and paclitaxel are first- and second-line agents for advanced KS, respectively.6

In HIV-associated KS, lesions frequently involute with the initiation of HAART; however, the cutaneous lesions in our patient persisted despite initiation of efavirenz-emtricitabine-tenofovir. He also was given intralesional doxorubicin andpaclitaxel as well as topical alitretinoin but did not experience complete resolution of the cutaneous lesions. It is possible that patients with VKS are recalcitrant to typical treatment modalities and therefore may require unconventional therapies to achieve maximal clearance of cutaneous lesions.

Verrucous Kaposi sarcoma is a rare presentation of KS that is infrequently seen in clinical practice or reported in the literature.3 A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the search term verrucous Kaposi sarcoma yielded 13 articles, one of which included a case series of 5 patients with AIDS and hyperkeratotic KS in Germany in the 1990s.5 Four of the articles were written in French, German, or Portuguese.8-11 The remainder of the articles discussed variants of KS other than VKS.

Although most patients with HIV and KS effectively respond to HAART, it may be possible that VKS is more difficult to treat. In addition, immunohistochemical staining for HHV-8, in particular HHV-8 latent nuclear antigen-1, may be useful to diagnose KS in HIV patients with uncharacteristic or indeterminate cutaneous lesions. Further research is needed to identify and delineate various efficacious therapeutic options for recalcitrant KS, particularly VKS.

Acknowledgment

We are indebted to Antoinette F. Hood, MD, Norfolk, Virginia, who digitized our patient’s histopathology slides.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

1. Grayson W, Pantanowitz L. Histological variants of cutaneous Kaposi sarcoma. Diagn Pathol. 2008;3:31.

2. Amodio E, Goedert JJ, Barozzi P, et al. Differences in Kaposi sarcoma-associated herpesvirus-specific and herpesvirus-non-specific immune responses in classic Kaposi sarcoma cases and matched controls in Sicily. Cancer Sci. 2011;102:1769-1773.

3. Fagone S, Cavaleri A, Camuto M, et al. Hyperkeratotic Kaposi sarcoma with leg lymphedema after prolonged corticosteroid therapy for SLE. case report and review of the literature. Minerva Med. 2001;92:177-202.

4. Cheuk W, Wong KO, Wong CS, et al. Immunostaining for human herpesvirus 8 latent nuclear antigen-1 helps distinguish Kaposi sarcoma from its mimickers. Am J Clin Pathol. 2004;121:335-342.

5. Hengge UR, Stocks K, Goos M. Acquired immune deficiency syndrome-related hyperkeratotic Kaposi’s sarcoma with severe lymphedema: report of 5 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2000;142:501-505.

6. James WD, Berger TG, Elston DM, eds. Andrews’ Diseases of the Skin: Clinical Dermatology. 10th ed. Philadelphia, PA: WB Saunders; 2006.

7. Thomas S, Sindhu CB, Sreekumar S, et al. AIDS associated Kaposi’s Sarcoma. J Assoc Physicians India. 2011;59:387-389.

8. Mukai MM, Chaves T, Caldas L, et al. Primary Kaposi’s sarcoma of the penis [in Portuguese]. An Bras Dermatol. 2009;84:524-526.

9. Weidauer H, Tilgen W, Adler D. Kaposi’s sarcoma of the larynx [in German]. Laryngol Rhinol Otol (Stuttg). 1986;65:389-391.

10. Basset A. Clinical aspects of Kaposi’s disease [in French]. Bull Soc Pathol Exot Filiales. 1984;77(4, pt 2):529-532.

11. Wlotzke U, Hohenleutner U, Landthaler M. Dermatoses in leg amputees [in German]. Hautarzt. 1996;47:493-501.

A disturbing conversation with another health care provider

One of my pet peeves is when a patient or colleague speaks ill of another health care provider. I find it unbecoming behavior that often (though not always) speaks more to the character of the speaker than that of the object of anger/derision/dissatisfaction. I recently had the misfortune of interacting with a nurse practitioner who behaved in this manner. (The evidence of my hypocrisy does not escape me.)

A patient had been having some vague complaints for about 5 years, including myalgias, headaches, and fatigue. She remembers a tick bite that preceded the onset of symptoms. She tested negative for Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses multiple times, but after seeing many different doctors she finally saw an infectious disease doctor who often treats patients for what he diagnoses as a chronic Lyme infection. The patient was on antibiotics for about 5 years. But because she didn’t really feel any better, she started questioning the diagnosis.

I explained to the patient why I thought that fibromyalgia might explain her symptoms. She looked this up on the Internet and found that the disease described her symptoms completely. She was happy to stop antibiotic treatment. However, in the interest of leaving no stone unturned, I referred her to a neurologist for her headaches.

The nurse practitioner who evaluated her sent her for a brain single-photon emission computed tomography scan that showed “multifocal regions of decreased uptake, distribution suggestive of vasculitis or multi-infarct dementia.” The NP then informed the patient of this result, said it was consistent with CNS Lyme, and asked her to return to the infectious disease doctor who then put her back on oral antibiotics.

The patient brought this all to my attention, asking for an opinion. I thought she probably had small vessel changes because she had hyperlipidemia and was a heavy smoker. But I was curious about the decision to label this as CNS Lyme, so I thought I would touch base with the NP. What ensued was possibly one of the most disturbing conversations I’ve had with another health care provider since I started practice.

She didn’t think she needed a lumbar puncture to confirm her diagnosis. She hadn’t bothered to order Lyme serologies or to look for previous results. “We take the patient’s word for it,” she smugly told me. She had full confidence that her diagnosis was correct, because “we see this all the time.” When I said I thought, common things being common, that the cigarette smoking was the most likely culprit for the changes, her response was: “Common things being common, Lyme disease is pretty common around here.” On the question of why the patient was getting oral antibiotics rather than IV antibiotics per Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for CNS Lyme, the response I got was again, that she sees this “all the time, and they do respond to oral antibiotics.”

I think the worst part was that when I pointed out that the preponderance of other doctors (two primary care physicians, two infectious disease doctors, another neurologist, another rheumatologist, and myself) did not agree with the diagnosis, her reply was to say that “the ID docs around here are way too conservative when it comes to treating chronic Lyme.”

Of course, she could very well be correct in her diagnosis. However, the conceit with which she so readily accused the ID specialists of being “too conservative” when she clearly did not do the necessary work herself (LP, serologies, etc.) just rubs me the wrong way. Lazy and arrogant make a horrible combination.

I politely disagreed and ended the conversation, but I was so worked up about the situation that I decided to write about it, thereby demonstrating the same bad behavior I claim to dislike. I am afraid at this stage in my professional development magnanimity is not a quality that I yet possess. Hopefully, I will not have many opportunities to demonstrate my lack of it.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

One of my pet peeves is when a patient or colleague speaks ill of another health care provider. I find it unbecoming behavior that often (though not always) speaks more to the character of the speaker than that of the object of anger/derision/dissatisfaction. I recently had the misfortune of interacting with a nurse practitioner who behaved in this manner. (The evidence of my hypocrisy does not escape me.)

A patient had been having some vague complaints for about 5 years, including myalgias, headaches, and fatigue. She remembers a tick bite that preceded the onset of symptoms. She tested negative for Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses multiple times, but after seeing many different doctors she finally saw an infectious disease doctor who often treats patients for what he diagnoses as a chronic Lyme infection. The patient was on antibiotics for about 5 years. But because she didn’t really feel any better, she started questioning the diagnosis.

I explained to the patient why I thought that fibromyalgia might explain her symptoms. She looked this up on the Internet and found that the disease described her symptoms completely. She was happy to stop antibiotic treatment. However, in the interest of leaving no stone unturned, I referred her to a neurologist for her headaches.

The nurse practitioner who evaluated her sent her for a brain single-photon emission computed tomography scan that showed “multifocal regions of decreased uptake, distribution suggestive of vasculitis or multi-infarct dementia.” The NP then informed the patient of this result, said it was consistent with CNS Lyme, and asked her to return to the infectious disease doctor who then put her back on oral antibiotics.

The patient brought this all to my attention, asking for an opinion. I thought she probably had small vessel changes because she had hyperlipidemia and was a heavy smoker. But I was curious about the decision to label this as CNS Lyme, so I thought I would touch base with the NP. What ensued was possibly one of the most disturbing conversations I’ve had with another health care provider since I started practice.

She didn’t think she needed a lumbar puncture to confirm her diagnosis. She hadn’t bothered to order Lyme serologies or to look for previous results. “We take the patient’s word for it,” she smugly told me. She had full confidence that her diagnosis was correct, because “we see this all the time.” When I said I thought, common things being common, that the cigarette smoking was the most likely culprit for the changes, her response was: “Common things being common, Lyme disease is pretty common around here.” On the question of why the patient was getting oral antibiotics rather than IV antibiotics per Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for CNS Lyme, the response I got was again, that she sees this “all the time, and they do respond to oral antibiotics.”

I think the worst part was that when I pointed out that the preponderance of other doctors (two primary care physicians, two infectious disease doctors, another neurologist, another rheumatologist, and myself) did not agree with the diagnosis, her reply was to say that “the ID docs around here are way too conservative when it comes to treating chronic Lyme.”

Of course, she could very well be correct in her diagnosis. However, the conceit with which she so readily accused the ID specialists of being “too conservative” when she clearly did not do the necessary work herself (LP, serologies, etc.) just rubs me the wrong way. Lazy and arrogant make a horrible combination.

I politely disagreed and ended the conversation, but I was so worked up about the situation that I decided to write about it, thereby demonstrating the same bad behavior I claim to dislike. I am afraid at this stage in my professional development magnanimity is not a quality that I yet possess. Hopefully, I will not have many opportunities to demonstrate my lack of it.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

One of my pet peeves is when a patient or colleague speaks ill of another health care provider. I find it unbecoming behavior that often (though not always) speaks more to the character of the speaker than that of the object of anger/derision/dissatisfaction. I recently had the misfortune of interacting with a nurse practitioner who behaved in this manner. (The evidence of my hypocrisy does not escape me.)

A patient had been having some vague complaints for about 5 years, including myalgias, headaches, and fatigue. She remembers a tick bite that preceded the onset of symptoms. She tested negative for Lyme disease and other tick-borne illnesses multiple times, but after seeing many different doctors she finally saw an infectious disease doctor who often treats patients for what he diagnoses as a chronic Lyme infection. The patient was on antibiotics for about 5 years. But because she didn’t really feel any better, she started questioning the diagnosis.

I explained to the patient why I thought that fibromyalgia might explain her symptoms. She looked this up on the Internet and found that the disease described her symptoms completely. She was happy to stop antibiotic treatment. However, in the interest of leaving no stone unturned, I referred her to a neurologist for her headaches.

The nurse practitioner who evaluated her sent her for a brain single-photon emission computed tomography scan that showed “multifocal regions of decreased uptake, distribution suggestive of vasculitis or multi-infarct dementia.” The NP then informed the patient of this result, said it was consistent with CNS Lyme, and asked her to return to the infectious disease doctor who then put her back on oral antibiotics.

The patient brought this all to my attention, asking for an opinion. I thought she probably had small vessel changes because she had hyperlipidemia and was a heavy smoker. But I was curious about the decision to label this as CNS Lyme, so I thought I would touch base with the NP. What ensued was possibly one of the most disturbing conversations I’ve had with another health care provider since I started practice.

She didn’t think she needed a lumbar puncture to confirm her diagnosis. She hadn’t bothered to order Lyme serologies or to look for previous results. “We take the patient’s word for it,” she smugly told me. She had full confidence that her diagnosis was correct, because “we see this all the time.” When I said I thought, common things being common, that the cigarette smoking was the most likely culprit for the changes, her response was: “Common things being common, Lyme disease is pretty common around here.” On the question of why the patient was getting oral antibiotics rather than IV antibiotics per Infectious Diseases Society of America guidelines for CNS Lyme, the response I got was again, that she sees this “all the time, and they do respond to oral antibiotics.”

I think the worst part was that when I pointed out that the preponderance of other doctors (two primary care physicians, two infectious disease doctors, another neurologist, another rheumatologist, and myself) did not agree with the diagnosis, her reply was to say that “the ID docs around here are way too conservative when it comes to treating chronic Lyme.”

Of course, she could very well be correct in her diagnosis. However, the conceit with which she so readily accused the ID specialists of being “too conservative” when she clearly did not do the necessary work herself (LP, serologies, etc.) just rubs me the wrong way. Lazy and arrogant make a horrible combination.

I politely disagreed and ended the conversation, but I was so worked up about the situation that I decided to write about it, thereby demonstrating the same bad behavior I claim to dislike. I am afraid at this stage in my professional development magnanimity is not a quality that I yet possess. Hopefully, I will not have many opportunities to demonstrate my lack of it.

Dr. Chan practices rheumatology in Pawtucket, R.I.

Avoiding disillusionment

The holiday season, despite the hustle and bustle, can be a time of reflection. Thanksgiving is a time to reflect on what you have. The secular version of Christmas is a deep plunge into materialism and getting the things you desire. Then come those New Year’s resolutions in which you swear off material things and promise yourself you will become the person you have always wanted to be.

For those in academic settings educating the next cohort of physicians, this time of year has its own rituals. Undergraduate and medical school applications are being reviewed. Medical students are interviewing for residencies. Match day for residents seeking subspecialty fellowships occurs in mid-December. The other residents are starting to interview for real jobs. Overall, a vast undertaking occurs in which talents and aspirations are matched with finite and practical opportunities.

My goal is to advocate for the health of children, so I am concerned about how well pediatrics attracts the best and brightest minds. The best training programs in the world are still going to produce mediocre doctors if we start with mediocre talent. The stakes in recruiting talent are huge. The Washington Post has been running a series on the disappearance of the middle class. Some articles have lamented that the finance sector has recently siphoned off the best and brightest minds to make money by pushing money, rather than creating new technology, products, and jobs (“A black hole for our best and brightest,” by Jim Tankersley on Dec. 14, 2014). My second concern is nourishing the ideals and aspirations of those physician seedlings. Few people keep all their New Year’s resolutions for the entire year, but even partial credit can be important progress in a balanced life.

First, we need to attract people to science. There is a recognized shortage of high school students going into STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). Various programs have been created to attract high school students, and particularly women, to those fields (“Women flocking to statistics, the newly hot, high-tech field of data science,” by Brigid Schulte, the Washington Post, Dec. 19, 2014). This then needs to be reinforced in college. For instance, the analysis of big data in health care is a burgeoning field. We need statisticians who can do the work.

Then we need to attract people to medicine. I’ve been in a few conversations recently about a book titled “Doctored: The Disillusionment of the American Physician,” by Dr. Sandeep Jauhar. I haven’t read more than a few excerpts from the book. An abbreviated version is the author’s essay, “Why Doctors Are Sick of Their Profession,” in the Wall Street Journal (Aug. 29, 2014).

There were enough inaccuracies in that article to dissuade me from reading further, but your mileage may differ. There are data to both support and refute most of his assertions. I believe he is correct that there have been some Faustian bargains made by the past two generations of doctors. Medicine welcomed the improved revenues from Medicare and Medicaid coverage. Those programs improved access, justice, health outcomes, and especially doctors’ incomes, but at a steep price to society. The Golden Goose Dr. Jauhar cited was indeed killed. The following generation of doctors has had to deal with managed care, preapprovals, and denials of payment, along with other cost controls. It was irrational to think that all that money from the government to physicians was going to flow indefinitely without strings. In a related development, the resulting paperwork has crushed solo office practice. Rather than being entrepreneurs, recently boarded pediatricians are trending toward larger group practices and salaried positions. So that affects the degree of independence in a medical career.

In pediatrics, physicians invest considerable time to open career paths into subspecialty areas that interest them, even if the income and lifestyle aren’t better and don’t justify the time and expense of further training. Pediatric hospital medicine is progressing toward becoming a boarded subspecialty with 2-year fellowships. Will that attract the best and brightest of the residents?

Continuing medical education is needed to maintain a knowledge base and a skill set. I assert there also needs to be continuing examination and reinforcement of one’s ideals and life goals. As a pediatrician, I am biased toward believing that maintaining a recommended daily allowance of that activity outperforms making New Year’s resolutions. We all know that crash diets rarely work in the long run.

What practical steps can be taken in the pediatrician’s office? Put up posters that encourage STEM education. Ask adolescents about their plans. The health and life expectancy of your patient will be related far more to his or her career choice than to the discovery of the next medicine to treat chronic hepatitis C. Spending just a moment of each adolescent well visit to explore his/her aspirations also may be just the medicine you need to avoid disillusionment. Maybe you will even inspire a bright teenager to become a pediatrician.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He is also listserv moderator for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine. E-mail him at [email protected].

The holiday season, despite the hustle and bustle, can be a time of reflection. Thanksgiving is a time to reflect on what you have. The secular version of Christmas is a deep plunge into materialism and getting the things you desire. Then come those New Year’s resolutions in which you swear off material things and promise yourself you will become the person you have always wanted to be.

For those in academic settings educating the next cohort of physicians, this time of year has its own rituals. Undergraduate and medical school applications are being reviewed. Medical students are interviewing for residencies. Match day for residents seeking subspecialty fellowships occurs in mid-December. The other residents are starting to interview for real jobs. Overall, a vast undertaking occurs in which talents and aspirations are matched with finite and practical opportunities.

My goal is to advocate for the health of children, so I am concerned about how well pediatrics attracts the best and brightest minds. The best training programs in the world are still going to produce mediocre doctors if we start with mediocre talent. The stakes in recruiting talent are huge. The Washington Post has been running a series on the disappearance of the middle class. Some articles have lamented that the finance sector has recently siphoned off the best and brightest minds to make money by pushing money, rather than creating new technology, products, and jobs (“A black hole for our best and brightest,” by Jim Tankersley on Dec. 14, 2014). My second concern is nourishing the ideals and aspirations of those physician seedlings. Few people keep all their New Year’s resolutions for the entire year, but even partial credit can be important progress in a balanced life.

First, we need to attract people to science. There is a recognized shortage of high school students going into STEM fields (science, technology, engineering, and math). Various programs have been created to attract high school students, and particularly women, to those fields (“Women flocking to statistics, the newly hot, high-tech field of data science,” by Brigid Schulte, the Washington Post, Dec. 19, 2014). This then needs to be reinforced in college. For instance, the analysis of big data in health care is a burgeoning field. We need statisticians who can do the work.

Then we need to attract people to medicine. I’ve been in a few conversations recently about a book titled “Doctored: The Disillusionment of the American Physician,” by Dr. Sandeep Jauhar. I haven’t read more than a few excerpts from the book. An abbreviated version is the author’s essay, “Why Doctors Are Sick of Their Profession,” in the Wall Street Journal (Aug. 29, 2014).

There were enough inaccuracies in that article to dissuade me from reading further, but your mileage may differ. There are data to both support and refute most of his assertions. I believe he is correct that there have been some Faustian bargains made by the past two generations of doctors. Medicine welcomed the improved revenues from Medicare and Medicaid coverage. Those programs improved access, justice, health outcomes, and especially doctors’ incomes, but at a steep price to society. The Golden Goose Dr. Jauhar cited was indeed killed. The following generation of doctors has had to deal with managed care, preapprovals, and denials of payment, along with other cost controls. It was irrational to think that all that money from the government to physicians was going to flow indefinitely without strings. In a related development, the resulting paperwork has crushed solo office practice. Rather than being entrepreneurs, recently boarded pediatricians are trending toward larger group practices and salaried positions. So that affects the degree of independence in a medical career.

In pediatrics, physicians invest considerable time to open career paths into subspecialty areas that interest them, even if the income and lifestyle aren’t better and don’t justify the time and expense of further training. Pediatric hospital medicine is progressing toward becoming a boarded subspecialty with 2-year fellowships. Will that attract the best and brightest of the residents?

Continuing medical education is needed to maintain a knowledge base and a skill set. I assert there also needs to be continuing examination and reinforcement of one’s ideals and life goals. As a pediatrician, I am biased toward believing that maintaining a recommended daily allowance of that activity outperforms making New Year’s resolutions. We all know that crash diets rarely work in the long run.

What practical steps can be taken in the pediatrician’s office? Put up posters that encourage STEM education. Ask adolescents about their plans. The health and life expectancy of your patient will be related far more to his or her career choice than to the discovery of the next medicine to treat chronic hepatitis C. Spending just a moment of each adolescent well visit to explore his/her aspirations also may be just the medicine you need to avoid disillusionment. Maybe you will even inspire a bright teenager to become a pediatrician.

Dr. Powell is a pediatric hospitalist and clinical ethics consultant living in St. Louis. He is also listserv moderator for the American Academy of Pediatrics Section on Hospital Medicine. E-mail him at [email protected].

The holiday season, despite the hustle and bustle, can be a time of reflection. Thanksgiving is a time to reflect on what you have. The secular version of Christmas is a deep plunge into materialism and getting the things you desire. Then come those New Year’s resolutions in which you swear off material things and promise yourself you will become the person you have always wanted to be.

For those in academic settings educating the next cohort of physicians, this time of year has its own rituals. Undergraduate and medical school applications are being reviewed. Medical students are interviewing for residencies. Match day for residents seeking subspecialty fellowships occurs in mid-December. The other residents are starting to interview for real jobs. Overall, a vast undertaking occurs in which talents and aspirations are matched with finite and practical opportunities.