User login

Measures predict outcomes of chronic HCV with compensated cirrhosis

Readily available clinical measures can be used to reliably predict long-term outcome in patients with chronic HCV infections and well-compensated advanced liver disease, Dr. Adriaan J van der Meer, of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and his colleagues report.

The researchers devised risk scores for mortality and for cirrhosis-related complications from a cohort of 405 patients, 100 of whom died during about 8 years of follow up. They then applied the model to 296 patients, 59 of whom died during 6 years of follow up. Independent predictive factors included age, male sex, platelet count, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio, the researcher said in an article published in the January issue of Gut ( Gut 2015;64:322-331).

Click here to read the article in Gut: http://gut.bmj.com/content/64/2/322.abstract

Readily available clinical measures can be used to reliably predict long-term outcome in patients with chronic HCV infections and well-compensated advanced liver disease, Dr. Adriaan J van der Meer, of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and his colleagues report.

The researchers devised risk scores for mortality and for cirrhosis-related complications from a cohort of 405 patients, 100 of whom died during about 8 years of follow up. They then applied the model to 296 patients, 59 of whom died during 6 years of follow up. Independent predictive factors included age, male sex, platelet count, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio, the researcher said in an article published in the January issue of Gut ( Gut 2015;64:322-331).

Click here to read the article in Gut: http://gut.bmj.com/content/64/2/322.abstract

Readily available clinical measures can be used to reliably predict long-term outcome in patients with chronic HCV infections and well-compensated advanced liver disease, Dr. Adriaan J van der Meer, of Erasmus University Medical Center, Rotterdam, The Netherlands, and his colleagues report.

The researchers devised risk scores for mortality and for cirrhosis-related complications from a cohort of 405 patients, 100 of whom died during about 8 years of follow up. They then applied the model to 296 patients, 59 of whom died during 6 years of follow up. Independent predictive factors included age, male sex, platelet count, and aspartate aminotransferase/alanine aminotransferase ratio, the researcher said in an article published in the January issue of Gut ( Gut 2015;64:322-331).

Click here to read the article in Gut: http://gut.bmj.com/content/64/2/322.abstract

Tiny Lesion Turns Troublesome After Trauma

Four months ago, this 23-year-old man developed a lesion on his right shoulder. It appeared, as he recalls, over the course of a week and has subsequently grown. The lesion, which is now rather large, bleeds copiously with minor trauma. It causes only modest discomfort to the patient but considerable worry to his family.

The lesion was originally tiny and tag-like; the patient initially mistook it for a tick and tried to pull it off. Not only did that fail to work, it also seemed to irritate the lesion. At that point, it started to swell, eventually transforming into the lesion he presents with today.

The patient’s history is otherwise uneventful, and he reports taking no medications. He has had minimal sun exposure but says he tans easily when he does get some sun.

EXAMINATION

The lesion, measuring 5 mm x 2.5 mm, is a dark red and pedunculated papule on the crown of the right shoulder. It looks edematous and feels firm. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

Shave biopsy is performed, using a double-edged razor to make a shallow concave defect under the lesion. The wound is cauterized.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the clinical suspicion of pyogenic granuloma, which, ironically, is neither pyogenic nor granulomatous. The condition acquired this name more than 100 years ago, based on assumptions about its origin. Microscopic examination revealed the highly vascular nature of these lesions, showing a field full of circles that represented the truncated ends of bundles of capillaries and venules. Although they are also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, the term pyogenic granuloma (PG) is still more commonly used.

PGs commonly manifest in the patient’s second or third decade of life, typically on extremities, chest, and nipples. This patient’s story is typical: His lesion began as a tag or wart that he then traumatized, creating a situation in which the body attempts (in vain) to heal the wound. Undisturbed, nearly all PGs would eventually wither and resolve with minimal scarring; however, that process is prolonged when the patient fails to “leave it alone.” (This is especially true in the case of young children.)

While this presentation is characteristic, there are other circumstances in which PGs develop. One is as a consequence of taking certain medications (eg, retinoids, antiretrovirals, and certain chemotherapy drugs). PGs are also commonly seen in the oral cavity of pregnant women in the third trimester and on the end of the umbilical stump in many newborns. Ingrown toenails are another common site; PGs will appear as glistening red, friable buttons of vascular tissue in the perionychial skin adjacent to the affected portion of the nail.

Shave biopsy is standard in such cases, not only to produce a cure but also to establish, via pathologic examination of the tissue, the correct diagnosis. (Nodular melanoma is the most prominent item in the differential; to miss that diagnosis would have dire consequences.) In terms of treatment, mere cautery or cryotherapy will not work and excision is seldom necessary. A deep shave will capture the entire lesion; if any remains, electrodessication and curettage will take care of it. Prior to such procedures, the patient (and family) needs to understand that scarring and pigment loss will occur.

In cases associated with medications or with ingrown toenails, the “cure” would be to withdraw the offending medications—although this is not always advisable for other, obvious reasons.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pyogenic granulomas (PG) have nothing to do with infection, nor are they truly granulomatous.

• PGs bleed readily with minor trauma and are often swollen and occasionally painful.

• PGs appear to represent, in most cases, the body’s frustrated attempt to heal a wound, most often a prick or pinch of a pre-existing lesion (eg, tag or mole).

• PGs are also seen in other contexts, such as with use of certain medications or in association with pregnancy.

• If treatment is attempted, the resulting specimen must be submitted for pathologic examination, since other lesions can mimic PGs (of most concern, nodular melanoma).

Four months ago, this 23-year-old man developed a lesion on his right shoulder. It appeared, as he recalls, over the course of a week and has subsequently grown. The lesion, which is now rather large, bleeds copiously with minor trauma. It causes only modest discomfort to the patient but considerable worry to his family.

The lesion was originally tiny and tag-like; the patient initially mistook it for a tick and tried to pull it off. Not only did that fail to work, it also seemed to irritate the lesion. At that point, it started to swell, eventually transforming into the lesion he presents with today.

The patient’s history is otherwise uneventful, and he reports taking no medications. He has had minimal sun exposure but says he tans easily when he does get some sun.

EXAMINATION

The lesion, measuring 5 mm x 2.5 mm, is a dark red and pedunculated papule on the crown of the right shoulder. It looks edematous and feels firm. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

Shave biopsy is performed, using a double-edged razor to make a shallow concave defect under the lesion. The wound is cauterized.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the clinical suspicion of pyogenic granuloma, which, ironically, is neither pyogenic nor granulomatous. The condition acquired this name more than 100 years ago, based on assumptions about its origin. Microscopic examination revealed the highly vascular nature of these lesions, showing a field full of circles that represented the truncated ends of bundles of capillaries and venules. Although they are also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, the term pyogenic granuloma (PG) is still more commonly used.

PGs commonly manifest in the patient’s second or third decade of life, typically on extremities, chest, and nipples. This patient’s story is typical: His lesion began as a tag or wart that he then traumatized, creating a situation in which the body attempts (in vain) to heal the wound. Undisturbed, nearly all PGs would eventually wither and resolve with minimal scarring; however, that process is prolonged when the patient fails to “leave it alone.” (This is especially true in the case of young children.)

While this presentation is characteristic, there are other circumstances in which PGs develop. One is as a consequence of taking certain medications (eg, retinoids, antiretrovirals, and certain chemotherapy drugs). PGs are also commonly seen in the oral cavity of pregnant women in the third trimester and on the end of the umbilical stump in many newborns. Ingrown toenails are another common site; PGs will appear as glistening red, friable buttons of vascular tissue in the perionychial skin adjacent to the affected portion of the nail.

Shave biopsy is standard in such cases, not only to produce a cure but also to establish, via pathologic examination of the tissue, the correct diagnosis. (Nodular melanoma is the most prominent item in the differential; to miss that diagnosis would have dire consequences.) In terms of treatment, mere cautery or cryotherapy will not work and excision is seldom necessary. A deep shave will capture the entire lesion; if any remains, electrodessication and curettage will take care of it. Prior to such procedures, the patient (and family) needs to understand that scarring and pigment loss will occur.

In cases associated with medications or with ingrown toenails, the “cure” would be to withdraw the offending medications—although this is not always advisable for other, obvious reasons.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pyogenic granulomas (PG) have nothing to do with infection, nor are they truly granulomatous.

• PGs bleed readily with minor trauma and are often swollen and occasionally painful.

• PGs appear to represent, in most cases, the body’s frustrated attempt to heal a wound, most often a prick or pinch of a pre-existing lesion (eg, tag or mole).

• PGs are also seen in other contexts, such as with use of certain medications or in association with pregnancy.

• If treatment is attempted, the resulting specimen must be submitted for pathologic examination, since other lesions can mimic PGs (of most concern, nodular melanoma).

Four months ago, this 23-year-old man developed a lesion on his right shoulder. It appeared, as he recalls, over the course of a week and has subsequently grown. The lesion, which is now rather large, bleeds copiously with minor trauma. It causes only modest discomfort to the patient but considerable worry to his family.

The lesion was originally tiny and tag-like; the patient initially mistook it for a tick and tried to pull it off. Not only did that fail to work, it also seemed to irritate the lesion. At that point, it started to swell, eventually transforming into the lesion he presents with today.

The patient’s history is otherwise uneventful, and he reports taking no medications. He has had minimal sun exposure but says he tans easily when he does get some sun.

EXAMINATION

The lesion, measuring 5 mm x 2.5 mm, is a dark red and pedunculated papule on the crown of the right shoulder. It looks edematous and feels firm. The patient has otherwise unremarkable type IV skin.

Shave biopsy is performed, using a double-edged razor to make a shallow concave defect under the lesion. The wound is cauterized.

What is the diagnosis?

DISCUSSION

The pathology report confirmed the clinical suspicion of pyogenic granuloma, which, ironically, is neither pyogenic nor granulomatous. The condition acquired this name more than 100 years ago, based on assumptions about its origin. Microscopic examination revealed the highly vascular nature of these lesions, showing a field full of circles that represented the truncated ends of bundles of capillaries and venules. Although they are also called lobular capillary hemangiomas, the term pyogenic granuloma (PG) is still more commonly used.

PGs commonly manifest in the patient’s second or third decade of life, typically on extremities, chest, and nipples. This patient’s story is typical: His lesion began as a tag or wart that he then traumatized, creating a situation in which the body attempts (in vain) to heal the wound. Undisturbed, nearly all PGs would eventually wither and resolve with minimal scarring; however, that process is prolonged when the patient fails to “leave it alone.” (This is especially true in the case of young children.)

While this presentation is characteristic, there are other circumstances in which PGs develop. One is as a consequence of taking certain medications (eg, retinoids, antiretrovirals, and certain chemotherapy drugs). PGs are also commonly seen in the oral cavity of pregnant women in the third trimester and on the end of the umbilical stump in many newborns. Ingrown toenails are another common site; PGs will appear as glistening red, friable buttons of vascular tissue in the perionychial skin adjacent to the affected portion of the nail.

Shave biopsy is standard in such cases, not only to produce a cure but also to establish, via pathologic examination of the tissue, the correct diagnosis. (Nodular melanoma is the most prominent item in the differential; to miss that diagnosis would have dire consequences.) In terms of treatment, mere cautery or cryotherapy will not work and excision is seldom necessary. A deep shave will capture the entire lesion; if any remains, electrodessication and curettage will take care of it. Prior to such procedures, the patient (and family) needs to understand that scarring and pigment loss will occur.

In cases associated with medications or with ingrown toenails, the “cure” would be to withdraw the offending medications—although this is not always advisable for other, obvious reasons.

TAKE-HOME LEARNING POINTS

• Pyogenic granulomas (PG) have nothing to do with infection, nor are they truly granulomatous.

• PGs bleed readily with minor trauma and are often swollen and occasionally painful.

• PGs appear to represent, in most cases, the body’s frustrated attempt to heal a wound, most often a prick or pinch of a pre-existing lesion (eg, tag or mole).

• PGs are also seen in other contexts, such as with use of certain medications or in association with pregnancy.

• If treatment is attempted, the resulting specimen must be submitted for pathologic examination, since other lesions can mimic PGs (of most concern, nodular melanoma).

Studies shed new light on HSPC mobilization

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

in the bone marrow

Two new studies have revealed elements that are key to hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell (HSPC) mobilization.

In one study, investigators discovered that elevated levels of the peptide hormone angiotensin II increases HSPC mobilization in the context of vasculopathy and sickle cell disease (SCD).

In the other study, researchers found that p62, an autophagy regulator and signal organizer, is required to maintain HSPC retention in the bone marrow.

Jose Cancelas, MD, PhD, of the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine in Ohio, is the corresponding author on both studies.

In the first paper, published in Nature Communications, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues noted that patients with vasculopathies have an increase in circulating HSPCs.

“This phenomenon may represent a stress response contributing to vascular damage repair,” he said. “So the question becomes, how can we learn from these patients?”

Using mouse models of vasculopathy and vasculopathy-associated SCD, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues showed that acute and chronic elevated levels of angiotensin II resulted in an increased pool of HSPCs.

And when the researchers administered anti-angiotensin therapy, the pool of HSPCs decreased in mice and humans with SCD.

“These results indicate a new role for angiotensin in hematopoietic stem and progenitor cell trafficking under pathological conditions and define the hematopoietic consequences of anti-angiotensin therapy in vascular disease and sickle cell disease,” Dr Cancelas said.

“Every year, millions of patients receive anti-angiotensin therapies due to the harmful effects associated with chronic hyperangiotensinemia in cardiac, renal, or liver failure. Our study shows that this anti-angiotensin therapy modulates the levels of circulating stem cells and progenitors.”

In the second paper, published in Cell Reports, Dr Cancelas and his colleagues examined the role that p62 plays in HSPC mobilization.

The investigators found that, when p62 is lost in osteoblasts, mice develop a condition similar to osteoporosis in humans.

The osteoblasts cannot degrade inflammatory signals coming from macrophages. And as a consequence, the deficient osteoblasts secrete inflammatory signals that impair the retention of HSPCs in the bone marrow and allow their escape to the circulation.

Specifically, the team found that macrophages activate osteoblastic NF-kB, which results in osteopenia and HSPC egress. And p62 negatively regulates osteoblastic NF-kB activation.

Dr Cancelas noted that patients with inflammatory diseases often have osteopenia. So this research may provide insight into that phenomenon and help explain why patients with chronic inflammatory diseases have higher levels of circulating HSPCs. ![]()

EC supports continued use of ponatinib

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Credit: Rhoda Baer

The European Commission (EC) has concluded that ponatinib (Iclusig) should continue to be prescribed in accordance with its already approved indications.

After trial results suggested the drug poses an increased risk of thrombotic events, the European Medicines Agency’s (EMA) Pharmacovigilance Risk Assessment Committee (PRAC) conducted a review of available ponatinib data.

Results of that review suggested the benefits of ponatinib outweigh the risks. So the committee said the drug should be prescribed as indicated.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recently endorsed this recommendation, and, now, the EC has followed suit. The EC’s decision is legally binding.

Ponatinib is approved in the European Union to treat adults with chronic phase, accelerated phase, or blast phase chronic myeloid leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib or nilotinib, who are intolerant to dasatinib or nilotinib and for whom subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

The drug is also approved to treat adults with Philadelphia-chromosome positive acute lymphoblastic leukemia who are resistant to dasatinib, who cannot tolerate dasatinib and subsequent treatment with imatinib is not clinically appropriate, or who have the T315I mutation.

In October 2013, extended follow-up data from the PACE trial revealed that ponatinib-treated patients had a higher incidence of arterial and venous thrombotic events than was observed when the drug first gained approval. So one ponatinib trial was discontinued, and the rest were placed on partial clinical hold.

Soon after, ponatinib was pulled from the US market. The drug ultimately returned to the marketplace with new recommendations designed to decrease the risk of thrombotic events.

The EMA also revised its recommendations for ponatinib—discouraging use of the drug in certain patients, providing advice for managing comorbidities, and suggesting patient monitoring—but kept the drug on the market.

In October 2014, the PRAC concluded its 11-month review of ponatinib data, confirming that the benefit-risk profile of the drug was favorable in its approved indications and recommending that the indications remain unchanged.

However, the PRAC also said the risk of vascular occlusive events with ponatinib is likely dose-related. So the committee recommended that healthcare professionals monitor ponatinib-treated patients and consider dose reductions or discontinuing the drug in certain patients.

The CHMP endorsed these recommendations, and, now, the EC has as well. This is a legally binding decision for ponatinib to continue to be prescribed in Europe in accordance with its already approved indications.

Ponatinib is being developed by ARIAD Pharmaceuticals, Inc. ![]()

Combining bed nets and vaccines may worsen malaria risk

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

New research suggests that combining the use of malaria vaccines and insecticide-treated bed nets may actually increase the incidence of malaria.

The researchers used a mathematical model of malaria transmission to examine potential interactions between vaccines and bed nets.

They found that using insecticide-treated bed nets along with pre-erythrocytic vaccines (PEVs) or blood-stage vaccines (BSVs) increased the number of malaria cases.

However, using bed nets in conjunction with transmission-blocking vaccines (TBVs) resulted in fewer cases of malaria and increased the probability of eliminating the disease.

“The joint use of bed nets and vaccines will not always lead to consistent increases in the efficacy of malaria control,” said study author Mercedes Pascual, PhD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Specifically, our study suggests that the combined use of some malaria vaccines with bed nets can lead to increased morbidity and mortality in older age classes.”

Dr Pascual and her colleagues described this research in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team noted that the malaria vaccine candidates currently under development fall into 3 categories, each focusing on a different stage of the malaria life cycle.

PEVs aim to reduce the chances that a person will be infected when bitten by a disease-carrying mosquito. BSVs don’t block infection but try to reduce the level of disease severity and the number of fatalities.

And TBVs don’t protect vaccinated individuals against infection or illness, but they prevent mosquitoes from spreading the disease to others after biting a vaccinated person.

Dr Pascual and her colleagues found that using bed nets in communities treated with BSVs can increase levels of morbidity—to levels even higher than those expected in the absence of nets. Furthermore, BSVs can’t promote malaria elimination on their own.

PEVs can promote malaria elimination, but the researchers found regions of decreased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were low and increased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were high.

This suggests that higher levels of PEV coverage and bed net use could result in malaria elimination, but it would involve crossing a peak of enhanced morbidity.

Finally, the researchers found that using bed nets in communities treated with TBVs always leads to significant decreases in morbidity and increases the probability of malaria elimination.

“Ironically, the vaccines that work best with bed nets are the ones that do not protect the vaccinated host—the bed net does that—but instead block transmission of malaria in mosquitoes that have found an opportunity to bite vaccinated hosts,” said study author Yael Artzy-Randrup, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

Unraveling the interactions between bed nets and vaccines is especially challenging due to the complex and transient nature of malaria immunity, the researchers noted.

A child’s first malaria infection can result in severe, sometimes fatal, illness. If the child survives, he or she will gain partial immunity that reduces the risk of severe illness in the future.

Additional bites from infected mosquitoes can help the child retain that immunity, which would otherwise wane after 1 to 2 years. But the combination of bed nets and certain vaccines can undermine that natural immunity.

“This complexity is at the heart of why it has been so hard to develop any sort of malaria vaccine,” said study author Andrew Dobson, DPhil, of Princeton University in New Jersey. ![]()

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

New research suggests that combining the use of malaria vaccines and insecticide-treated bed nets may actually increase the incidence of malaria.

The researchers used a mathematical model of malaria transmission to examine potential interactions between vaccines and bed nets.

They found that using insecticide-treated bed nets along with pre-erythrocytic vaccines (PEVs) or blood-stage vaccines (BSVs) increased the number of malaria cases.

However, using bed nets in conjunction with transmission-blocking vaccines (TBVs) resulted in fewer cases of malaria and increased the probability of eliminating the disease.

“The joint use of bed nets and vaccines will not always lead to consistent increases in the efficacy of malaria control,” said study author Mercedes Pascual, PhD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Specifically, our study suggests that the combined use of some malaria vaccines with bed nets can lead to increased morbidity and mortality in older age classes.”

Dr Pascual and her colleagues described this research in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team noted that the malaria vaccine candidates currently under development fall into 3 categories, each focusing on a different stage of the malaria life cycle.

PEVs aim to reduce the chances that a person will be infected when bitten by a disease-carrying mosquito. BSVs don’t block infection but try to reduce the level of disease severity and the number of fatalities.

And TBVs don’t protect vaccinated individuals against infection or illness, but they prevent mosquitoes from spreading the disease to others after biting a vaccinated person.

Dr Pascual and her colleagues found that using bed nets in communities treated with BSVs can increase levels of morbidity—to levels even higher than those expected in the absence of nets. Furthermore, BSVs can’t promote malaria elimination on their own.

PEVs can promote malaria elimination, but the researchers found regions of decreased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were low and increased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were high.

This suggests that higher levels of PEV coverage and bed net use could result in malaria elimination, but it would involve crossing a peak of enhanced morbidity.

Finally, the researchers found that using bed nets in communities treated with TBVs always leads to significant decreases in morbidity and increases the probability of malaria elimination.

“Ironically, the vaccines that work best with bed nets are the ones that do not protect the vaccinated host—the bed net does that—but instead block transmission of malaria in mosquitoes that have found an opportunity to bite vaccinated hosts,” said study author Yael Artzy-Randrup, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

Unraveling the interactions between bed nets and vaccines is especially challenging due to the complex and transient nature of malaria immunity, the researchers noted.

A child’s first malaria infection can result in severe, sometimes fatal, illness. If the child survives, he or she will gain partial immunity that reduces the risk of severe illness in the future.

Additional bites from infected mosquitoes can help the child retain that immunity, which would otherwise wane after 1 to 2 years. But the combination of bed nets and certain vaccines can undermine that natural immunity.

“This complexity is at the heart of why it has been so hard to develop any sort of malaria vaccine,” said study author Andrew Dobson, DPhil, of Princeton University in New Jersey. ![]()

Credit: Caitlin Kleiboer

New research suggests that combining the use of malaria vaccines and insecticide-treated bed nets may actually increase the incidence of malaria.

The researchers used a mathematical model of malaria transmission to examine potential interactions between vaccines and bed nets.

They found that using insecticide-treated bed nets along with pre-erythrocytic vaccines (PEVs) or blood-stage vaccines (BSVs) increased the number of malaria cases.

However, using bed nets in conjunction with transmission-blocking vaccines (TBVs) resulted in fewer cases of malaria and increased the probability of eliminating the disease.

“The joint use of bed nets and vaccines will not always lead to consistent increases in the efficacy of malaria control,” said study author Mercedes Pascual, PhD, of the University of Michigan in Ann Arbor.

“Specifically, our study suggests that the combined use of some malaria vaccines with bed nets can lead to increased morbidity and mortality in older age classes.”

Dr Pascual and her colleagues described this research in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The team noted that the malaria vaccine candidates currently under development fall into 3 categories, each focusing on a different stage of the malaria life cycle.

PEVs aim to reduce the chances that a person will be infected when bitten by a disease-carrying mosquito. BSVs don’t block infection but try to reduce the level of disease severity and the number of fatalities.

And TBVs don’t protect vaccinated individuals against infection or illness, but they prevent mosquitoes from spreading the disease to others after biting a vaccinated person.

Dr Pascual and her colleagues found that using bed nets in communities treated with BSVs can increase levels of morbidity—to levels even higher than those expected in the absence of nets. Furthermore, BSVs can’t promote malaria elimination on their own.

PEVs can promote malaria elimination, but the researchers found regions of decreased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were low and increased morbidity when PEV vaccination levels were high.

This suggests that higher levels of PEV coverage and bed net use could result in malaria elimination, but it would involve crossing a peak of enhanced morbidity.

Finally, the researchers found that using bed nets in communities treated with TBVs always leads to significant decreases in morbidity and increases the probability of malaria elimination.

“Ironically, the vaccines that work best with bed nets are the ones that do not protect the vaccinated host—the bed net does that—but instead block transmission of malaria in mosquitoes that have found an opportunity to bite vaccinated hosts,” said study author Yael Artzy-Randrup, PhD, of the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

Unraveling the interactions between bed nets and vaccines is especially challenging due to the complex and transient nature of malaria immunity, the researchers noted.

A child’s first malaria infection can result in severe, sometimes fatal, illness. If the child survives, he or she will gain partial immunity that reduces the risk of severe illness in the future.

Additional bites from infected mosquitoes can help the child retain that immunity, which would otherwise wane after 1 to 2 years. But the combination of bed nets and certain vaccines can undermine that natural immunity.

“This complexity is at the heart of why it has been so hard to develop any sort of malaria vaccine,” said study author Andrew Dobson, DPhil, of Princeton University in New Jersey. ![]()

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin effective in transplant patients with compensated recurrent HCV

Patients who develop HCV infections after liver transplant may respond to a 24-week course of sofosbuvir and ribavirin, Dr. Michael Charlton, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported.

The researchers enrolled and treated 40 liver transplant patients with compensated recurrent HCV infection of any genotype; 83% had HCV genotype 1, 40% had cirrhosis (based on biopsy), and 88% had been previously treated with interferon. All patients received 24 weeks of sofosbuvir 400 mg daily and ribavirin starting at 400 mg daily, which was adjusted according to creatinine clearance and hemoglobin values, the researchers said in the January 2015 issue of Gastroenterology.

After 12 weeks, 28 of 40 had a sustained virologic response (70%; 90% confidence interval: 56%−82%). Relapse accounted for all cases of virologic failure. No patients had detectable viral resistance during or after treatment.

Click here to read the study: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25304641

Patients who develop HCV infections after liver transplant may respond to a 24-week course of sofosbuvir and ribavirin, Dr. Michael Charlton, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported.

The researchers enrolled and treated 40 liver transplant patients with compensated recurrent HCV infection of any genotype; 83% had HCV genotype 1, 40% had cirrhosis (based on biopsy), and 88% had been previously treated with interferon. All patients received 24 weeks of sofosbuvir 400 mg daily and ribavirin starting at 400 mg daily, which was adjusted according to creatinine clearance and hemoglobin values, the researchers said in the January 2015 issue of Gastroenterology.

After 12 weeks, 28 of 40 had a sustained virologic response (70%; 90% confidence interval: 56%−82%). Relapse accounted for all cases of virologic failure. No patients had detectable viral resistance during or after treatment.

Click here to read the study: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25304641

Patients who develop HCV infections after liver transplant may respond to a 24-week course of sofosbuvir and ribavirin, Dr. Michael Charlton, of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn., and his colleagues reported.

The researchers enrolled and treated 40 liver transplant patients with compensated recurrent HCV infection of any genotype; 83% had HCV genotype 1, 40% had cirrhosis (based on biopsy), and 88% had been previously treated with interferon. All patients received 24 weeks of sofosbuvir 400 mg daily and ribavirin starting at 400 mg daily, which was adjusted according to creatinine clearance and hemoglobin values, the researchers said in the January 2015 issue of Gastroenterology.

After 12 weeks, 28 of 40 had a sustained virologic response (70%; 90% confidence interval: 56%−82%). Relapse accounted for all cases of virologic failure. No patients had detectable viral resistance during or after treatment.

Click here to read the study: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25304641

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin prevent HCV recurrence after liver transplantation

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin given before liver transplantation prevented most cases of post-transplant HCV recurrence, according to Dr. Michael P. Curry, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and his colleagues.

Up to 48 weeks of sofosbuvir (400 mg) and ribavirin were given to hepatocellular carcinoma patients on organ transplant waitlists. The patients had HCV of any genotype and cirrhosis (Child–Turcotte–Pugh score of 7 or less). The primary end point of the study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01559844) was the proportion of 43 patients who had HCV-RNA levels of less than 25 IU/ml at transplant and at 12 weeks after transplant.

Of the 43 patients, 30 (70%) had a post-transplantation virologic response at 12 weeks, 10 (23%) had recurrent infection, and 3 (7%) died, the researchers reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

Click here to read the entire article: http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085%2814%2901145-7/fulltext

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin given before liver transplantation prevented most cases of post-transplant HCV recurrence, according to Dr. Michael P. Curry, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and his colleagues.

Up to 48 weeks of sofosbuvir (400 mg) and ribavirin were given to hepatocellular carcinoma patients on organ transplant waitlists. The patients had HCV of any genotype and cirrhosis (Child–Turcotte–Pugh score of 7 or less). The primary end point of the study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01559844) was the proportion of 43 patients who had HCV-RNA levels of less than 25 IU/ml at transplant and at 12 weeks after transplant.

Of the 43 patients, 30 (70%) had a post-transplantation virologic response at 12 weeks, 10 (23%) had recurrent infection, and 3 (7%) died, the researchers reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

Click here to read the entire article: http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085%2814%2901145-7/fulltext

Sofosbuvir and ribavirin given before liver transplantation prevented most cases of post-transplant HCV recurrence, according to Dr. Michael P. Curry, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, and his colleagues.

Up to 48 weeks of sofosbuvir (400 mg) and ribavirin were given to hepatocellular carcinoma patients on organ transplant waitlists. The patients had HCV of any genotype and cirrhosis (Child–Turcotte–Pugh score of 7 or less). The primary end point of the study (ClinicalTrials.gov: NCT01559844) was the proportion of 43 patients who had HCV-RNA levels of less than 25 IU/ml at transplant and at 12 weeks after transplant.

Of the 43 patients, 30 (70%) had a post-transplantation virologic response at 12 weeks, 10 (23%) had recurrent infection, and 3 (7%) died, the researchers reported in the January issue of Gastroenterology.

Click here to read the entire article: http://www.gastrojournal.org/article/S0016-5085%2814%2901145-7/fulltext

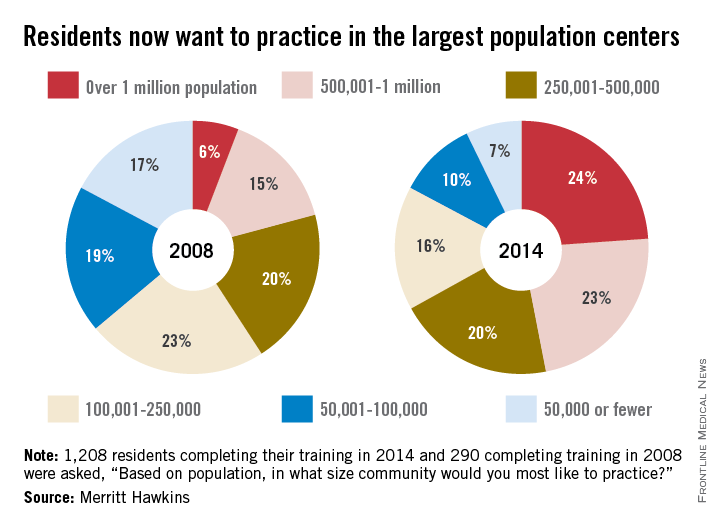

Residents looking to work in larger cities

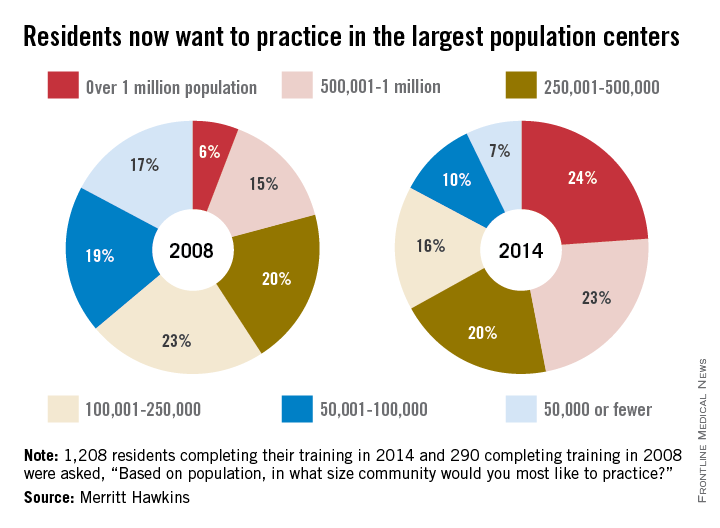

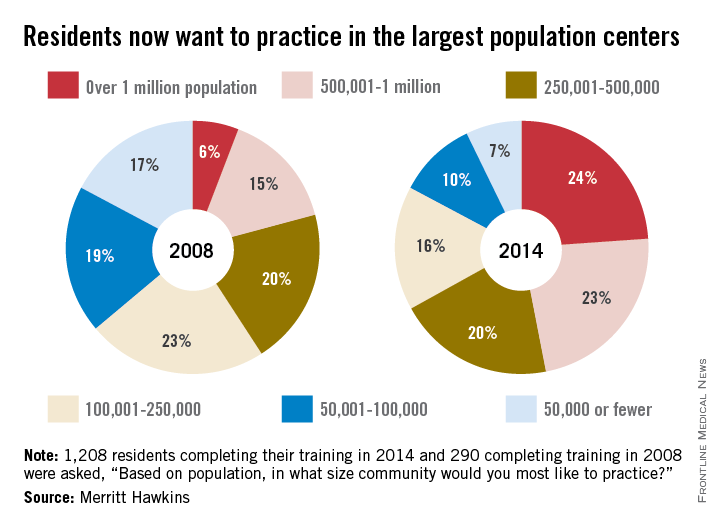

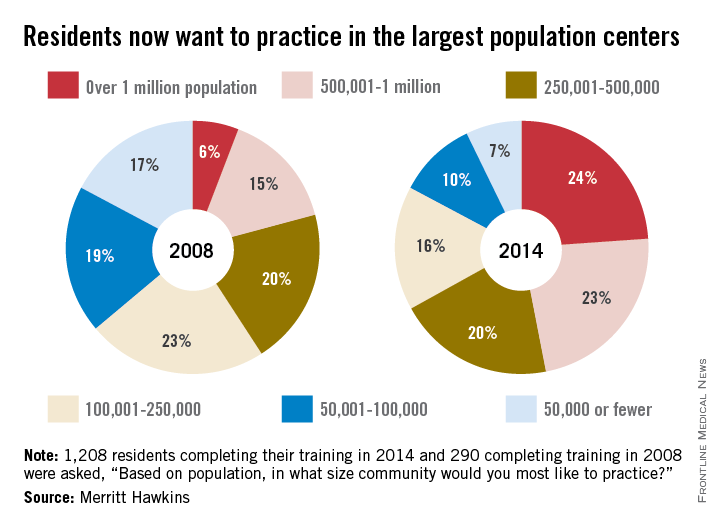

Since 2008, residents’ preference for their future practice location has shifted from smaller cities and rural areas to large population centers, according to findings reported by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

In a survey of residents who completed their training in 2014, 24% said that they wanted to practice in a community with a population of more than 1 million, compared with 6% in 2008, while 23% of residents chose the next-highest level of population – 500,001 to 1 million – compared with 15% in 2008, according to Merritt Hawkins.

As for the smaller communities, residents who wanted to practice in a area of 50,000 or fewer dropped from 17% in 2008 to 7% in 2014. Support for communities of 50,001-100,000 fell from 19% in 2008 to 10% in 2014, the company said. Only 1% of residents wanted to practice in a community of 10,000 people or fewer in 2014.

Residents’ reservations about practicing in rural areas more often are related to their “concerns about being on a clinical ‘island’ without specialty support, information technology, and other resources than they may be about the amenities of rural communities,” Merritt Hawkins said in its analysis of the 1,208 survey responses.

Since 2008, residents’ preference for their future practice location has shifted from smaller cities and rural areas to large population centers, according to findings reported by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

In a survey of residents who completed their training in 2014, 24% said that they wanted to practice in a community with a population of more than 1 million, compared with 6% in 2008, while 23% of residents chose the next-highest level of population – 500,001 to 1 million – compared with 15% in 2008, according to Merritt Hawkins.

As for the smaller communities, residents who wanted to practice in a area of 50,000 or fewer dropped from 17% in 2008 to 7% in 2014. Support for communities of 50,001-100,000 fell from 19% in 2008 to 10% in 2014, the company said. Only 1% of residents wanted to practice in a community of 10,000 people or fewer in 2014.

Residents’ reservations about practicing in rural areas more often are related to their “concerns about being on a clinical ‘island’ without specialty support, information technology, and other resources than they may be about the amenities of rural communities,” Merritt Hawkins said in its analysis of the 1,208 survey responses.

Since 2008, residents’ preference for their future practice location has shifted from smaller cities and rural areas to large population centers, according to findings reported by physician recruitment firm Merritt Hawkins.

In a survey of residents who completed their training in 2014, 24% said that they wanted to practice in a community with a population of more than 1 million, compared with 6% in 2008, while 23% of residents chose the next-highest level of population – 500,001 to 1 million – compared with 15% in 2008, according to Merritt Hawkins.

As for the smaller communities, residents who wanted to practice in a area of 50,000 or fewer dropped from 17% in 2008 to 7% in 2014. Support for communities of 50,001-100,000 fell from 19% in 2008 to 10% in 2014, the company said. Only 1% of residents wanted to practice in a community of 10,000 people or fewer in 2014.

Residents’ reservations about practicing in rural areas more often are related to their “concerns about being on a clinical ‘island’ without specialty support, information technology, and other resources than they may be about the amenities of rural communities,” Merritt Hawkins said in its analysis of the 1,208 survey responses.

Coexisting Frailty, Cognitive Impairment, and Heart Failure: Implications for Clinical Care

From the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, GA.

Abstract

- Objective: To review some of the proposed pathways that increase frailty risk in older persons with heart failure and to discuss tools that may be used to assess for changes in physical and cognitive functioning in this population in order to assist with appropriate and timely intervention.

- Methods: Review of the literature.

- Results: Heart failure is the only cardiovascular disease that is increasing by epidemic proportions, largely due to an aging society and therapeutic advances in disease management. Because heart failure is largely a cardiogeriatric syndrome, age-related syndromes such as frailty and cognitive impairment are common in heart failure patients. Compared with age-matched counterparts, older adults with heart failure 4 to 6 times more likely to be frail or cognitively impaired. The reason for the high prevalence of frailty and cognitive impairment in this population is not well known but may likely reflect the synergistic effects of heart failure and aging, which may heighten vulnerability to stressors and accelerate loss of physiologic reserve. Despite the high prevalence of frailty and cognitive impairment in the heart failure population, these conditions are not routinely screened for in clinical practice settings and guidelines on optimal assessment strategies are lacking.

- Conclusion: Persons with heart failure are at an increased risk for frailty, which may worsen symptoms, impair self-management, and lead to worse heart failure outcomes. Early detection of frailty and cognitive impairment may be an opportunity for intervention and a key strategy for improving clinical outcomes in older adults with heart failure.

Approximately 5.7 million persons in the United States are diagnosed with heart failure, and the number of reported new cases is expected to increase to over 700,000 cases annually by the year 2040 [1]. This rising incidence is fueled by an aging population; by the year 2030, 1 in 5 Americans will be over 65 years of age [2]. Heart failure is prevalent among those 65 years of age and older and is the most common reason for hospitalization in this age-group. High readmission rates, approaching 50% over 6 months, are a major contributor to the the escalating economic burden associated with heart failure [3].

Persons with heart failure are more likely to be frail and experience cognitive impairment than their age-matched counterparts without heart failure. The reasons for this are not well known but may be related to hemodynamic, vascular, and inflammatory changes occurring as heart failure progresses. In this paper, we review the link between frailty and cognitive impairment in heart failure, instruments that may be useful for early detection, and interventions such as exercise that may be beneficial for attenuating both conditions.

Frailty in Heart Failure

Epidemiology

Frailty is a heightened vulnerability to stressors in the presence of low physiological reserve [4]. When exposed to stressors, persons who are frail have a much higher probability for disproportionate decompensation, negative events, functional decline, disability, and mortality [5]. Among persons with heart failure, frailty may predispose them to decompensate at a lower threshold, requiring more frequent hospitalizations. Persons with heart failure are more likely to be frail than their age-matched counterparts without heart failure [6,7].

Frailty is a powerful predictor of poor clinical outcomes and mortality in cardiovascular disease [8,9]. Compared with the non-frail, frail persons with heart failure have increased rates of mortality (16.9% vs 4.8%) and increased rates of heart failure hospitalization (20.5% vs 13.3%) [10]. Frailty has also been shown to predict falls, disability, and hospitalization in heart failure patients [6,9,11] and was found to have a negative linear relationship with health-related quality of life [12]. Frail heart failure patients are also more likely to have comorbidities such diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, atrial fibrillation, depression, anemia, and chronic kidney disease [9,13].

Pathophysiology

There is significant overlap in the underlying pathological mechanisms of heart failure and frailty. Symptoms of heart failure, such as dyspnea, fatigue, and muscle loss, mirror components that occur with frailty. Further, cardiac cachexia, a metabolic syndrome in advanced heart failure characterized by a loss of muscle mass, is very similar to the sarcopenia that occurs in frailty.

Frailty, characterized by an increased physiologic vulnerability to stressors, may predispose frail persons with heart failure to exacerbation and worsening of heart failure due to greater susceptibility to the harmful pathophysiologic processes in heart failure, such as inflammation and autonomic dysfunction. Proposed pathophysiologic pathways in frailty include free radicals and oxidative stress, cumulative DNA damage, decreased telomere length, and nuclear fragmentation [14,15]. Frailty has been associated with low-grade chronic inflammation and increased inflammatory cytokines, such as C-reactive protein, tumor necrosis factor–alpha (TNFα), interleukin-6 (IL-6)and fibrinogen [16–18]. Heart failure also is associated with a low-grade and chronic cardiac inflammatory response that is correlated with disease progression [19].

Inflammation. IL-6 is detectable in a higher proportion of persons who are frail compared to non-frail [16] and is the most highly correlated biomarker with frailty. In addition, among those with detectable IL-6 levels, those categorized as frail have higher IL-6 levels compared to those who are non-frail [16,20]. Individuals categorized as frail were found to have significantly higher levels of TNFα than those who were non-frail [16,20]. Increased IL-6 levels are associated with decreased muscle strength, while increased TNFα levels are associated with decreased skeletal muscle protein synthesis [21,22], thus contributing to frailty.

Oxidative stress. Protein carbonyls result from protein oxidation promoted by reactive oxygen species and are markers of oxidative stress. Protein carbonylation is implicated in the pathogenesis of the loss of skeletal muscle mass; high serum protein carbonyls are associated with poor grip strength [23]. 8-OHdG is an oxidized nucleoside indicative of oxidative damage to DNA and a measure of oxidative stress. Accumulation of 8-OHdG in skeletal muscle leads to loss of muscle mass and is associated with decreased hand grip strength in the elderly [24]. Higher serum levels of 8-OHdG are present in older adults who are frail as compared to those who are non-frail [25].

Measurement of Frailty in the Clinical Setting

Frailty has been conceptualized in a number of studies using different models and measures; however, there continues to be a lack of consensus on the definition and operationalization of frailty. Prior research has led to the development of several validated models of frailty that have demonstrated good prediction of adverse outcomes in older adults. Some models, such as the Fried phenotype [6], focus solely on the physical dimension, while other models take a multidimensional approach.Single-item measures (eg, gait speed, 6-minute walk test, handgrip strength) are also commonly used to screen for frailty, but a frailty measure that incorporates more than 1 physical dimension may be more sensitive and reliable. In our opinion, the ideal measure of frailty would consist of a brief assessment that can be serially performed in most clinical practice settings that can identify change in function over time. The incorporation of sensitive physical function measures that can detect frailty early has the potential to slow physical function decline by preserving physiological thresholds.

Cognitive Impairment in Heart Failure

Epidemiology

Cognitive impairment occurs frequently in patients with heart failure, and the presence of cognitive impairment in persons with heart failure has been shown to heighten risk for adverse clinical outcomes, disability, poor quality of life, and mortality [26,27]. Heart failure negatively influences cognitive functioning in most domains [28–32]. The most common domains adversely affected by heart failure and aging are memory and executive function. Deficits in these domains can substantially diminish patient ability to carry out essential self-care behaviors [30,32].

The most common form of cognitive impairment seen in patients with heart failure is mild cognitive impairment (MCI), which is a measurable deficit with memory or another core cognitive domain. Up to 60% of persons with heart failure have been reported to have MCI. Patients with MCI have cognitive deficits that are more pronounced than those seen in normal aging, but lack other symptoms of dementia, such as impaired judgment or reasoning. MCI often will not impede patients’ ability to carry out the activities of daily living (ADLs) independently, but patients may have difficulty in performing some instrumental activities of daily living (IADLs), such as remembering medications, scheduling provider appointments. Dementia, a decline in cognitive ability severe enough to hinder an individual’s ability to perform ADLs or IADLs or engage in social activities or occupational responsibilities, occurs in approximately 25% of persons with heart failure [33].

Persons with heart failure have a fourfold greater likelihood of developing CI than persons without heart failure. Several cohort studies have shown that persons with heart failure had lower performance on cognitive tests than individuals without heart failure [34,35] and were 50% more likely to progress to dementia.

Assessment Tools

Although a comprehensive neurocognitive battery would aid in detecting cognitive impairment in heart failure, few clinical practice settings have the resources to perform such a detailed and time-consuming measurement. Most studies in heart failure have relied on global screening questionnaires such as the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) [36] to assess cognitive functioning in persons with heart failure and in other cardiovascular disorders. Global cognitive measures, however, often lack sensitivity for detecting subtle cognitive deficits such as seen in MCI [28–30]. Screening that measures executive function may be the most beneficial for busy clinical settings, since declines in this domain are well established as contributing to poor outcomes in persons with heart failure.

The Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA) is a rapid screening test designed to detect MCI. It assesses different cognitive domains, including attention, memory, language, and executive function [37]. The MoCA lends itself to use in clinical setting because it is brief, requires little training to administer, and is easy to score. This instrument has been used successfully to assess MCI in persons with heart failure and may be more sensitive than the MMSE in identifying clinically relevant cognitive dysfunction. In 2013 study, Cameron et al [38] administered the MMSE and MoCA to 93 hospitalized heart failure patients and found that the MoCA classified 41% of patients as cognitively impaired that were not classified using the MMSE. For persons with a vascular cognitive deficit, the MMSE has been portrayed as an inadequate screening test due to lack of sensitivity for visuospatial and executive function deficits. Because the MoCA was designed to be more sensitive to such deficits, it may be a superior screening method for persons with heart failure. Although previous studies support the use of the MoCA in persons with heart failure, more research is needed in larger, more diverse heart failure samples with a wide range of cognitive deficits.

A Reasonable Clinical Assessment Approach

Considering the link between heart failure, frailty, and MCI, incorporating simple physical performance measures with cognitive screening may be an effective strategy to identify persons at risk for frailty. Two clinically relevant physical performance-based measures of frailty are proposed: the Fried phenotype (mentioned earlier) and the Short Physical Performance Battery (SBBP). In addition, cognitive screening using the MoCA is recommended as part of the routine examination for determining possible MCI or more severe cognitive deficits. The predictive validity of measuring physical frailty is enhanced when cognitive impairment is included in the assessment [36,39].

The performance-based measures included in this review have previously demonstrated excellent psychometric properties as well as sensitivity for change that is clinically meaningful. Minimal detectable change (MDC), a threshold score that refers to the minimal amount of change outside of error that reflects true change by a patient between 2 time points (rather than variation in measurement), is important for interpreting level of risk for frailty and is included for each instrument [40,41]. If a more brief frailty examination is needed, cut-points for gait speed and handgrip have been used effectively in a number of studies as a threshold for determining frailty, including in older patients with cardiovascular disease and in heart failure [8,42,43].

Fried Frailty Phenotype

The Fried phenotype is an appropriate method of measuring frailty in a clinical setting due to its wide application across diverse populations and consistent identification of adverse outcomes [44]. This model is derived from a frailty model proposed by Fried et al [6] in which a phenotypic cycle exists that includes disease, sarcopenia, decreased walking speed, chronic undernutrition, decreased total energy expenditure, senescent musculoskeletal changes, decreased resting metabolic rate, weight loss and decreased maximal oxygen consumption. Frailty exists when a critical mass of these cycle components are identified in an individual [6].

To validate the model, Fried et al used data from the Cardiovascular Health Study and used the model to show association with a 3-year and 7-year incidence of mobility and ADL disability among 4317 community-dwelling men and women aged 65 years and older, independent of comorbidities. Several studies have directly tested the frailty phenotype model alone and in comparison to other models of frailty in large prospective studies across different populations, such as the Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe (SHARE) [45], the European Male Aging Study [46], and the Canadian Health Study of Aging [47]. While these studies found the prevalence of frailty to vary across the populations, they all validated the Fried model and found no significant differences in the predictive ability of the Fried model and other models of frailty. The Frailty Consensus conference evaluated the different models of frailty and determined that the Fried model is a validated construct of frailty and is acceptable for use in the identification of individuals who are frail or likely to become frail [48]. Thus, the Fried et al frailty phenotype model is considered to be a standard measure of frailty in older individuals.

Short Physical Performance Battery

In other chronic illness populations, the SPPB has also been used as a predictor of outcomes before, during, or after hospitalization. Valpato et al [53], for example, used the SPPB to assess older adults (mean age, 78 yr) admitted to the hospital with a diagnosis of heart failure (64%), pneumonia (13%), chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (16%), or minor stroke (6.6%) at admission (baseline) and discharge. Patients with the lowest SPPB quartile scores at hospital discharge had a fivefold greater risk of rehospitalization or mortality compared to the highest quartile. In addition, those who had an early decline in SPPB scores 1 month after hospital discharge had greater limitations in performing activities of daily living and a significantly greater probability of being re-hospitalized or death during the 1-year follow-up period. These studies suggest that the SPPB at the first follow-up outpatient visit following hospital discharge may be beneficial for identifying need for further intervention or the need for more frequent follow-up care. Although the SPPB is not part of the Fried et al phenotype, it may provide additional information concerning risk for falls and lower extremity strength that may be beneficial in the evaluation of some persons with heart failure [54]. The SPPB along with instructions and normative data are available for clinical use at no charge at www.grc.nia.nih.gov/branches/ledb/sppb/index.htm.

Interventions for Frailty in Heart Failure

Interventions to address frailty have included exercise training, comprehensive geriatric assessment and management services, social support systems, nutrition, and drugs; however, few intervention studies have examined frailty in heart failure [8]. Restoration of physical function through aerobic exercise and resistance training has shown benefit in frail older adults [55–57] and in persons with heart failure [58]. Maintaining and/or restoring physical function through aerobic and resistance exercise training may be the key to preventing further decline or potentially reversing frailty in older adults with heart failure.

Aerobic exercise has been shown to be beneficial for both frail older adults and frail persons with heart failure [18]. In a study of community-dwelling frail older adults aged 65 and older, a combined aerobic and resistance exercise intervention, performed over 16 weeks, demonstrated significant improvement in frailty scores during the 1-year follow-up in contrast to worsening frailty measures in the control group [57].

Older adults with heart failure experience a much lower exercise tolerance largely due to a 50% to 75% decrease in aerobic capacity in addition to the well-known alterations in peripheral musculoskeletal performance that contribute to fatigue and greater symptom severity. Aerobic exercise has been shown to be beneficial for most heart failure patients by altering the peripheral and central mechanisms, such as inflammatory cytokines, that contribute to heart failure exacerbations, worsened symptom severity, and poor clinical outcomes [59–62].Lower rates of hospitalization, improved physical function, and enhanced health-related quality of life are reported in heart failure patients who routinely exercise [59]. Resistance training has been shown to improve physical function in frail older adults [55]. Further, the use of TheraBand exercise bands in resistance training demonstrated improvement in physical function among frail older adults [56].

Exercise also appears to exert a positive effect on cognition, particularly executive functioning, and may also have a protective effect against cognitive decline with aging and among those with heart failure. The underlying mechanism for improvement in cognition remains poorly understood but is likely related to improved cardiac function, cerebral perfusion, and oxygenation, although this has not been clearly established. Larson et al (2006) evaluated the frequency of participation in a variety of physical activities (eg, walking, bicycling and swimming) over 6 years in 1740 older adults [63]. Older adults who exercised more than 3 times per week during initial assessment were 34% less likely to be diagnosed with dementia than those who exercised fewer than 3 times per week. Several meta-analyses in recent years have shown a consistent and positive relationship between aerobic exercise and cognition [64,65]. Importantly, findings from meta-analyses have shown a moderate effect size (> 0.5) from aerobic training, which was similar for normal and cognitively impaired adults [64].

Implications for Clinical Care

A systematic assessment performed periodically using physical and cognitive measures that may identify prefrailty may be the best strategy for preventing further functional loss, limitations, and disability in persons with heart failure. Persons with heart failure ideally should be evaluated annually for physical function, since a decline has been consistently shown to be a strong predictor of adverse health outcomes, disability, and death [6,66]. Cognitive function should also be assessed routinely in persons with heart failure, particularly when first diagnosed, when changes in treatment regimen occur, and with worsening disease severity, since these events have been shown to occur before changes in cognition [31]. Incorporating geriatric performance-based measures in heart failure management would allow for more treatment strategies aimed at improving physical function, cognitive outcomes, and quality of life. Further, identifying frailty in heart failure is an important component of clinical decision-making when determining if a patient can tolerate therapies such as implantable defibrillators, cardiac resynchronization therapy, or left ventricular assist device placement.

In older adults, performance measures are well established and commonly used as part of geriatric assessment to evaluate physical and cognitive functioning. Performance-based measures may be particularly beneficial in older adults with heart failure to monitor serial changes in physical function. Performance measures in clinical settings require staff time but little training, space, equipment, or risk. As performance measures become more common in practice settings, MDC thresholds may need to be re-evaluated based on the characteristics of the population [67].

For persons with heart failure whose screening outcomes suggest MCI, more comprehensive neuropsychological testing should be available as well as provision of resources to optimize functional independence. Early identification of impaired cognition may lower risk of poor self-management through simplification of medication regimens or providing resources to help manage other regimens essential for optimal heart failure care. It is also important to recognize that depressive symptoms are common in persons with heart failure and are highly correlated with cognitive impairment in this population. Screening for depressive symptoms therefore, may also enhance identification of persons with heart failure at risk for frailty [4,28].

Conclusion

Effective appraisal and development of effective interventions are essential in older adults with heart failure who are at high risk for frailty and cognitive impairment. This will become increasingly important as the population ages and the incidence of heart failure rises proportionately. Although curative treatments for frailty and cognitive impairment are not available, interdisciplinary interventions such as exercise and comprehensive geriatric assessment may improve outcomes in older persons with heart failure [68]. Information gained from objective, simple, inexpensive physical performance measures, when used in combination with cognitive screening, may enhance the ability to evaluate change that signal onset of frailty or cognitive impairment [54,69,70]. The high morbidity and mortality associated with frailty and cognitive impairment indicate that it should be a priority for future research as a strategy to improve clinical outcomes, enhance quality of life, and lower health care costs in this growing population.

Corresponding author: Rebecca Gary, PhD, RN, Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, Emory University, Atlanta, GA 30322, [email protected].

Funding/support: B. Butts was partially funded for this work through National Institutes of Health/National

Institute of Nursing Research Grant #T32NR012715.

1. Velagaleti RS and Vasan RS. Heart failure in the twenty-first century: is it a coronary artery disease or hypertension problem. Cardiol Clin 2007;25:487–95.

2. Vincent GK, Velkoff VA. The next four decades. The older population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. United States Census Bureau Report No: P25-1138. U.S. Department of Commerce; May 2010.

3. Butler J, Kalogeropoulos A. Worsening heart failure hospitalization epidemic we do not know how to prevent and we do not know how to treat. J Am Coll Cardiol 2008;52:435–7.

4. Gary R. Evaluation of frailty in older adults with cardiovascular disease: incorporating physical performance measures. J Cardiovasc Nurs 2012;27:120–131.

5. Shamliyan T, Talley KM, Ramakrishnan R, Kane RL. Association of frailty with survival: a systematic literature review. Age Res Rev 2013;12:719–36.

6. Fried LP, Tangen CM, Walston J, et al. Frailty in older adults: evidence for a phenotype. J Gerontol Med Sci 2001; 56:M146–M156.

7. Newman AB, Gottdiener JS, Mcburnie MA, et al. Associations of subclinical cardiovascular disease with frailty. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci 2001;56:M158–66.

8. Afilalo J, Karunananthan S, Eisenberg MJ, et al. Role of frailty in patients with cardiovascular disease. Am J Cardiol 2009; 103:1616–21.

9. Cacciatore F, Abete P, Maella F, et al. Frailty predicts long-term mortality in elderly subjects with chronic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest 2008;35:723–30.

10. Lupón J, González B, Santaeugenia S, et al. Prognostic implication of frailty and depressive symptoms in an outpatient population with heart failure. Rev Españ Cardiol 2008;61:835–42.

11. Rich MW. Heart failure in the oldest patients: the impact of comorbid conditions. Am J Geriatr Cardiol 2007;14:134–41.