User login

Tips for Minimizing Recurrence of Seizures

Combo can fight infection, GVHD

Image courtesy of NIAID

NEW ORLEANS—Results of a phase 1 trial suggest that modified T cells can fight infection in patients who have undergone haploidentical hematopoietic

stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), and subsequent administration of a bio-inert drug can ameliorate graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) in these patients.

Researchers introduced the suicide gene inducible caspase 9 (iC9) into T cells and infused them into transplant recipients to promote immune reconstitution.

For patients who went on to develop GVHD, the researchers activated the suicide gene by administering a dose of the drug rimiducid (AP1903).

This cleared the patients of GVHD symptoms without jeopardizing the remaining T cells’ ability to fight infection.

The researchers presented these results at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy Annual Meeting and reported them in Blood.

The trial was sponsored by Baylor College of Medicine, but Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the company developing rimiducid and the so-called iC9 “safety switch,” also known as CaspaCIDe.

“We’ve shown that the therapy works, fighting viruses that threaten immune-compromised patients,” said Xiaoou Zhou, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“We have also shown that the switch can turn off the T cells that reproduce out of control, attacking the patient’s graft-vs-host disease. This study was the first to look at any potential effect on the ability of the T cells to fight infection. We found there was no compromise.”

The study included 12 patients with a median age of 10 (range, 2-50) who had undergone haplo-HSCT. They received donor-derived T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe using a dose escalation schedule from 1×104 to 5×106 cells/kg, at a median of 42 days after transplant (range, 31-82 days).

All 12 patients had more rapid immune reconstitution and fewer infections after the infusions, when compared with previously reported results in T-cell-depleted, haplo-HSCT procedures. The CaspaCIDe T cells successfully provided protection from EBV, CMV, VZV, HHV6, and BKV viruses.

The researchers said there were no immediate toxicities related to the T-cell infusions, but 4 patients went on to develop GVHD.

Treatment with rimiducid resolved the patients’ GVHD symptoms within 6 to 48 hours. The researchers found that rimiducid could eliminate the uncontrolled T cells in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral blood.

Even after the problematic T cells were killed, the remaining T cells were able to fight infection without causing further GVHD.

One patient experienced a decrease in cell counts after receiving rimiducid, but counts had normalized by 48 hours. The researchers said there were no other immediate or delayed adverse effects associated with the drug.

One patient developed cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved in 2 hours with a single dose of rimiducid.

“This study shows that infusing larger numbers of haploidentical donor T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe leads to better infection control,” Dr Zhou said. “We also showed that, if GVHD occurs, it can be rapidly controlled and eliminated by removing alloreactive cells with rimiducid in vivo, and that the productive, antiviral and anticancer cells remain, repopulate, and maintain immunity.”

“This is a significant finding that can lead to broader adoption of curative haploidentical transplants for cancers and genetic blood disorders. It also suggests that CaspaCIDe has great potential with CAR T and TCR therapies, where rapid control of dangerous T-cell-mitigated toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome, is needed to achieve wide adoption.” ![]()

Image courtesy of NIAID

NEW ORLEANS—Results of a phase 1 trial suggest that modified T cells can fight infection in patients who have undergone haploidentical hematopoietic

stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), and subsequent administration of a bio-inert drug can ameliorate graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) in these patients.

Researchers introduced the suicide gene inducible caspase 9 (iC9) into T cells and infused them into transplant recipients to promote immune reconstitution.

For patients who went on to develop GVHD, the researchers activated the suicide gene by administering a dose of the drug rimiducid (AP1903).

This cleared the patients of GVHD symptoms without jeopardizing the remaining T cells’ ability to fight infection.

The researchers presented these results at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy Annual Meeting and reported them in Blood.

The trial was sponsored by Baylor College of Medicine, but Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the company developing rimiducid and the so-called iC9 “safety switch,” also known as CaspaCIDe.

“We’ve shown that the therapy works, fighting viruses that threaten immune-compromised patients,” said Xiaoou Zhou, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“We have also shown that the switch can turn off the T cells that reproduce out of control, attacking the patient’s graft-vs-host disease. This study was the first to look at any potential effect on the ability of the T cells to fight infection. We found there was no compromise.”

The study included 12 patients with a median age of 10 (range, 2-50) who had undergone haplo-HSCT. They received donor-derived T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe using a dose escalation schedule from 1×104 to 5×106 cells/kg, at a median of 42 days after transplant (range, 31-82 days).

All 12 patients had more rapid immune reconstitution and fewer infections after the infusions, when compared with previously reported results in T-cell-depleted, haplo-HSCT procedures. The CaspaCIDe T cells successfully provided protection from EBV, CMV, VZV, HHV6, and BKV viruses.

The researchers said there were no immediate toxicities related to the T-cell infusions, but 4 patients went on to develop GVHD.

Treatment with rimiducid resolved the patients’ GVHD symptoms within 6 to 48 hours. The researchers found that rimiducid could eliminate the uncontrolled T cells in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral blood.

Even after the problematic T cells were killed, the remaining T cells were able to fight infection without causing further GVHD.

One patient experienced a decrease in cell counts after receiving rimiducid, but counts had normalized by 48 hours. The researchers said there were no other immediate or delayed adverse effects associated with the drug.

One patient developed cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved in 2 hours with a single dose of rimiducid.

“This study shows that infusing larger numbers of haploidentical donor T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe leads to better infection control,” Dr Zhou said. “We also showed that, if GVHD occurs, it can be rapidly controlled and eliminated by removing alloreactive cells with rimiducid in vivo, and that the productive, antiviral and anticancer cells remain, repopulate, and maintain immunity.”

“This is a significant finding that can lead to broader adoption of curative haploidentical transplants for cancers and genetic blood disorders. It also suggests that CaspaCIDe has great potential with CAR T and TCR therapies, where rapid control of dangerous T-cell-mitigated toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome, is needed to achieve wide adoption.” ![]()

Image courtesy of NIAID

NEW ORLEANS—Results of a phase 1 trial suggest that modified T cells can fight infection in patients who have undergone haploidentical hematopoietic

stem cell transplant (haplo-HSCT), and subsequent administration of a bio-inert drug can ameliorate graft-vs-host disease (GVHD) in these patients.

Researchers introduced the suicide gene inducible caspase 9 (iC9) into T cells and infused them into transplant recipients to promote immune reconstitution.

For patients who went on to develop GVHD, the researchers activated the suicide gene by administering a dose of the drug rimiducid (AP1903).

This cleared the patients of GVHD symptoms without jeopardizing the remaining T cells’ ability to fight infection.

The researchers presented these results at the American Society of Gene and Cell Therapy Annual Meeting and reported them in Blood.

The trial was sponsored by Baylor College of Medicine, but Bellicum Pharmaceuticals is the company developing rimiducid and the so-called iC9 “safety switch,” also known as CaspaCIDe.

“We’ve shown that the therapy works, fighting viruses that threaten immune-compromised patients,” said Xiaoou Zhou, PhD, of Baylor College of Medicine in Houston, Texas.

“We have also shown that the switch can turn off the T cells that reproduce out of control, attacking the patient’s graft-vs-host disease. This study was the first to look at any potential effect on the ability of the T cells to fight infection. We found there was no compromise.”

The study included 12 patients with a median age of 10 (range, 2-50) who had undergone haplo-HSCT. They received donor-derived T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe using a dose escalation schedule from 1×104 to 5×106 cells/kg, at a median of 42 days after transplant (range, 31-82 days).

All 12 patients had more rapid immune reconstitution and fewer infections after the infusions, when compared with previously reported results in T-cell-depleted, haplo-HSCT procedures. The CaspaCIDe T cells successfully provided protection from EBV, CMV, VZV, HHV6, and BKV viruses.

The researchers said there were no immediate toxicities related to the T-cell infusions, but 4 patients went on to develop GVHD.

Treatment with rimiducid resolved the patients’ GVHD symptoms within 6 to 48 hours. The researchers found that rimiducid could eliminate the uncontrolled T cells in the central nervous system as well as the peripheral blood.

Even after the problematic T cells were killed, the remaining T cells were able to fight infection without causing further GVHD.

One patient experienced a decrease in cell counts after receiving rimiducid, but counts had normalized by 48 hours. The researchers said there were no other immediate or delayed adverse effects associated with the drug.

One patient developed cytokine release syndrome, but this was resolved in 2 hours with a single dose of rimiducid.

“This study shows that infusing larger numbers of haploidentical donor T cells engineered with CaspaCIDe leads to better infection control,” Dr Zhou said. “We also showed that, if GVHD occurs, it can be rapidly controlled and eliminated by removing alloreactive cells with rimiducid in vivo, and that the productive, antiviral and anticancer cells remain, repopulate, and maintain immunity.”

“This is a significant finding that can lead to broader adoption of curative haploidentical transplants for cancers and genetic blood disorders. It also suggests that CaspaCIDe has great potential with CAR T and TCR therapies, where rapid control of dangerous T-cell-mitigated toxicities, such as cytokine release syndrome, is needed to achieve wide adoption.” ![]()

Group learns how protein promotes AML

A few years ago, researchers discovered that inhibiting the protein BRD4 can treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the mechanism that explains how the protein works has remained a mystery.

Now, investigators have discovered the larger signaling pathway to which BRD4 belongs. The team said their discovery points to additional therapeutic targets for AML and other malignancies.

The group described this work in Molecular Cell.

BRD4: A retrospective

In 2011, Christopher Vakoc, MD, PhD, of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, and his colleagues identified potential drug targets for AML using RNA interference. Out of that screen came BRD4 and the realization that leukemia cells were “extremely sensitive” to inhibition of this protein.

In a bit of serendipity, drugs to inhibit BRD4 had just been developed for other purposes. Dr Vakoc and his colleagues tested these drugs and found that one in particular, JQ1, worked well against a mouse model of aggressive AML.

In the past few years, several groups have reported similar therapeutic results in mice using JQ1 and closely related drugs.

“It’s been very satisfying to see that other groups have independently validated our findings,” Dr Vakoc said.

Due to the evidence of their effectiveness in mice, inhibitors of BRD4 moved into clinical trials starting in 2013. Currently, there are 12 active clinical trials targeting BRD4 in leukemia and other cancers, including one sponsored by a company to which Dr Vakoc has licensed JQ1.

“Once we published the first paper in 2011, the main objective in our lab has been to understand why these drugs work,” Dr Vakoc said. “Knowing the mechanism of action of a drug is essential to making the drug better because there will likely be many generations of BRD4 inhibitors.”

JQ1 and BRD4: How they work

In the current study, Dr Vakoc and his colleagues discovered that BRD4 works very closely with transcription factors that bind to DNA and selectively control the activity of certain genes. The transcription factors control blood formation and essentially give blood cells their “identity.”

The researchers found that JQ1 can make leukemia cells shed their leukemia characteristics and differentiate into normal white blood cells. The team also identified an intermediary molecule called p300 between BRD4 and the leukemia-associated transcription factors.

Active areas of research in Dr Vakoc’s lab include exploring other players in the pathway, particularly the molecules that BRD4 controls, and learning more about the transcription factors.

“This new work is leading us to realize that transcription factors are the masters of the biological universe,” Dr Vakoc said. “Clearly, they are driving the cancer phenotype.” ![]()

A few years ago, researchers discovered that inhibiting the protein BRD4 can treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the mechanism that explains how the protein works has remained a mystery.

Now, investigators have discovered the larger signaling pathway to which BRD4 belongs. The team said their discovery points to additional therapeutic targets for AML and other malignancies.

The group described this work in Molecular Cell.

BRD4: A retrospective

In 2011, Christopher Vakoc, MD, PhD, of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, and his colleagues identified potential drug targets for AML using RNA interference. Out of that screen came BRD4 and the realization that leukemia cells were “extremely sensitive” to inhibition of this protein.

In a bit of serendipity, drugs to inhibit BRD4 had just been developed for other purposes. Dr Vakoc and his colleagues tested these drugs and found that one in particular, JQ1, worked well against a mouse model of aggressive AML.

In the past few years, several groups have reported similar therapeutic results in mice using JQ1 and closely related drugs.

“It’s been very satisfying to see that other groups have independently validated our findings,” Dr Vakoc said.

Due to the evidence of their effectiveness in mice, inhibitors of BRD4 moved into clinical trials starting in 2013. Currently, there are 12 active clinical trials targeting BRD4 in leukemia and other cancers, including one sponsored by a company to which Dr Vakoc has licensed JQ1.

“Once we published the first paper in 2011, the main objective in our lab has been to understand why these drugs work,” Dr Vakoc said. “Knowing the mechanism of action of a drug is essential to making the drug better because there will likely be many generations of BRD4 inhibitors.”

JQ1 and BRD4: How they work

In the current study, Dr Vakoc and his colleagues discovered that BRD4 works very closely with transcription factors that bind to DNA and selectively control the activity of certain genes. The transcription factors control blood formation and essentially give blood cells their “identity.”

The researchers found that JQ1 can make leukemia cells shed their leukemia characteristics and differentiate into normal white blood cells. The team also identified an intermediary molecule called p300 between BRD4 and the leukemia-associated transcription factors.

Active areas of research in Dr Vakoc’s lab include exploring other players in the pathway, particularly the molecules that BRD4 controls, and learning more about the transcription factors.

“This new work is leading us to realize that transcription factors are the masters of the biological universe,” Dr Vakoc said. “Clearly, they are driving the cancer phenotype.” ![]()

A few years ago, researchers discovered that inhibiting the protein BRD4 can treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML). However, the mechanism that explains how the protein works has remained a mystery.

Now, investigators have discovered the larger signaling pathway to which BRD4 belongs. The team said their discovery points to additional therapeutic targets for AML and other malignancies.

The group described this work in Molecular Cell.

BRD4: A retrospective

In 2011, Christopher Vakoc, MD, PhD, of Cold Spring Harbor Laboratory in Cold Spring Harbor, New York, and his colleagues identified potential drug targets for AML using RNA interference. Out of that screen came BRD4 and the realization that leukemia cells were “extremely sensitive” to inhibition of this protein.

In a bit of serendipity, drugs to inhibit BRD4 had just been developed for other purposes. Dr Vakoc and his colleagues tested these drugs and found that one in particular, JQ1, worked well against a mouse model of aggressive AML.

In the past few years, several groups have reported similar therapeutic results in mice using JQ1 and closely related drugs.

“It’s been very satisfying to see that other groups have independently validated our findings,” Dr Vakoc said.

Due to the evidence of their effectiveness in mice, inhibitors of BRD4 moved into clinical trials starting in 2013. Currently, there are 12 active clinical trials targeting BRD4 in leukemia and other cancers, including one sponsored by a company to which Dr Vakoc has licensed JQ1.

“Once we published the first paper in 2011, the main objective in our lab has been to understand why these drugs work,” Dr Vakoc said. “Knowing the mechanism of action of a drug is essential to making the drug better because there will likely be many generations of BRD4 inhibitors.”

JQ1 and BRD4: How they work

In the current study, Dr Vakoc and his colleagues discovered that BRD4 works very closely with transcription factors that bind to DNA and selectively control the activity of certain genes. The transcription factors control blood formation and essentially give blood cells their “identity.”

The researchers found that JQ1 can make leukemia cells shed their leukemia characteristics and differentiate into normal white blood cells. The team also identified an intermediary molecule called p300 between BRD4 and the leukemia-associated transcription factors.

Active areas of research in Dr Vakoc’s lab include exploring other players in the pathway, particularly the molecules that BRD4 controls, and learning more about the transcription factors.

“This new work is leading us to realize that transcription factors are the masters of the biological universe,” Dr Vakoc said. “Clearly, they are driving the cancer phenotype.” ![]()

Genome editing increases hemoglobin production

Scientists have found they can use a genome-editing technique to increase hemoglobin production, and they described this method in Nature Communications.

The team used transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) to introduce the hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH)-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines.

This served to switch on the fetal hemoglobin gene and increase hemoglobin production.

“Our laboratory study provides a proof of concept that changing just one letter of DNA in a gene could alleviate the symptoms of sickle cell anemia and thalassemia—inherited diseases in which people have damaged hemoglobin,” said Merlin Crossley, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia.

“Because the good genetic variation we introduced already exists in nature, this approach should be effective and safe. However, more research is needed before it can be tested in people as a possible cure for serious blood diseases.”

Dr Crossley and his colleagues introduced the HPFH-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines using TALENs, which can be designed to cut a gene at a specific point, as well as provide the desired piece of donor DNA for insertion.

“Breaks in DNA can be lethal to cells, so they have in-built machinery to repair any nicks as soon as possible, by grabbing any spare DNA that seems to match . . . ,” Dr Crossley explained.

“We exploited this effect. When our genome-editing protein cuts the DNA, the cell quickly replaces it with the donor DNA that we have also provided.”

The researchers pointed out that the HPFH-175T4C point mutation increased fetal globin expression via de novo recruitment of the activator TAL1, which promoted chromatin looping of distal enhancers to the modified γ-globin promoter.

The team also said that, if their editing technique proves safe and effective in hematopoietic stem cells, it could offer significant advantages over other approaches used to treat hemoglobin disorders, such as conventional gene therapy. ![]()

Scientists have found they can use a genome-editing technique to increase hemoglobin production, and they described this method in Nature Communications.

The team used transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) to introduce the hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH)-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines.

This served to switch on the fetal hemoglobin gene and increase hemoglobin production.

“Our laboratory study provides a proof of concept that changing just one letter of DNA in a gene could alleviate the symptoms of sickle cell anemia and thalassemia—inherited diseases in which people have damaged hemoglobin,” said Merlin Crossley, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia.

“Because the good genetic variation we introduced already exists in nature, this approach should be effective and safe. However, more research is needed before it can be tested in people as a possible cure for serious blood diseases.”

Dr Crossley and his colleagues introduced the HPFH-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines using TALENs, which can be designed to cut a gene at a specific point, as well as provide the desired piece of donor DNA for insertion.

“Breaks in DNA can be lethal to cells, so they have in-built machinery to repair any nicks as soon as possible, by grabbing any spare DNA that seems to match . . . ,” Dr Crossley explained.

“We exploited this effect. When our genome-editing protein cuts the DNA, the cell quickly replaces it with the donor DNA that we have also provided.”

The researchers pointed out that the HPFH-175T4C point mutation increased fetal globin expression via de novo recruitment of the activator TAL1, which promoted chromatin looping of distal enhancers to the modified γ-globin promoter.

The team also said that, if their editing technique proves safe and effective in hematopoietic stem cells, it could offer significant advantages over other approaches used to treat hemoglobin disorders, such as conventional gene therapy. ![]()

Scientists have found they can use a genome-editing technique to increase hemoglobin production, and they described this method in Nature Communications.

The team used transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) to introduce the hereditary persistence of fetal hemoglobin (HPFH)-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines.

This served to switch on the fetal hemoglobin gene and increase hemoglobin production.

“Our laboratory study provides a proof of concept that changing just one letter of DNA in a gene could alleviate the symptoms of sickle cell anemia and thalassemia—inherited diseases in which people have damaged hemoglobin,” said Merlin Crossley, PhD, of the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia.

“Because the good genetic variation we introduced already exists in nature, this approach should be effective and safe. However, more research is needed before it can be tested in people as a possible cure for serious blood diseases.”

Dr Crossley and his colleagues introduced the HPFH-175T4C point mutation into erythroid cell lines using TALENs, which can be designed to cut a gene at a specific point, as well as provide the desired piece of donor DNA for insertion.

“Breaks in DNA can be lethal to cells, so they have in-built machinery to repair any nicks as soon as possible, by grabbing any spare DNA that seems to match . . . ,” Dr Crossley explained.

“We exploited this effect. When our genome-editing protein cuts the DNA, the cell quickly replaces it with the donor DNA that we have also provided.”

The researchers pointed out that the HPFH-175T4C point mutation increased fetal globin expression via de novo recruitment of the activator TAL1, which promoted chromatin looping of distal enhancers to the modified γ-globin promoter.

The team also said that, if their editing technique proves safe and effective in hematopoietic stem cells, it could offer significant advantages over other approaches used to treat hemoglobin disorders, such as conventional gene therapy. ![]()

FDA grants drug orphan designation for AML

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for GMI-1271 to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

GMI-1271, an E-selectin antagonist, has shown promise in preclinical research and proven safe in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers, according to GlycoMimetics, Inc., the company developing the drug.

Now, the company is recruiting adults with AML in a phase 1/2 study to test GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy.

“Having the FDA designate GMI-1271 as an orphan drug for the treatment of AML is an important accomplishment for GlycoMimetics,” said Helen Thackray, MD, vice president of clinical development and chief medical officer at GlycoMimetics. “This is a significant regulatory milestone for our program.”

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program is designed to promote the development of drugs intended to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with benefits such as a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, protocol assistance, the ability to apply for research funding, tax credits for certain research expenses, and regulatory fee waivers.

Research with GMI-1271

Preclinical research presented at ASH 2013 suggested that GMI-1271 was able to overcome chemotherapy resistance in AML cells in vitro. The drug also reduced the leukemic burden in mouse models of AML when given in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

Murine research presented at ASH 2014 suggested that, by inhibiting E-selectin, GMI-1271 may increase leukemic stem cells’ sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs.

At the same meeting, researchers presented preclinical data on GMI-1271 as a treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, and venous thromboembolism.

In November 2014, GlycoMimetics announced results of phase 1 trial of GMI-1271 in healthy volunteers. Twenty-eight adults were enrolled in cohorts to receive the drug at 3 dose levels.

The company said subjects tolerated GMI-1271 well, and pharmacokinetics were as predicted based on preclinical research.

A multicenter, phase 1/2 trial of GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy is now recruiting adult patients with AML. ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for GMI-1271 to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

GMI-1271, an E-selectin antagonist, has shown promise in preclinical research and proven safe in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers, according to GlycoMimetics, Inc., the company developing the drug.

Now, the company is recruiting adults with AML in a phase 1/2 study to test GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy.

“Having the FDA designate GMI-1271 as an orphan drug for the treatment of AML is an important accomplishment for GlycoMimetics,” said Helen Thackray, MD, vice president of clinical development and chief medical officer at GlycoMimetics. “This is a significant regulatory milestone for our program.”

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program is designed to promote the development of drugs intended to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with benefits such as a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, protocol assistance, the ability to apply for research funding, tax credits for certain research expenses, and regulatory fee waivers.

Research with GMI-1271

Preclinical research presented at ASH 2013 suggested that GMI-1271 was able to overcome chemotherapy resistance in AML cells in vitro. The drug also reduced the leukemic burden in mouse models of AML when given in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

Murine research presented at ASH 2014 suggested that, by inhibiting E-selectin, GMI-1271 may increase leukemic stem cells’ sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs.

At the same meeting, researchers presented preclinical data on GMI-1271 as a treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, and venous thromboembolism.

In November 2014, GlycoMimetics announced results of phase 1 trial of GMI-1271 in healthy volunteers. Twenty-eight adults were enrolled in cohorts to receive the drug at 3 dose levels.

The company said subjects tolerated GMI-1271 well, and pharmacokinetics were as predicted based on preclinical research.

A multicenter, phase 1/2 trial of GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy is now recruiting adult patients with AML. ![]()

Image by Lance Liotta

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan designation for GMI-1271 to treat acute myeloid leukemia (AML).

GMI-1271, an E-selectin antagonist, has shown promise in preclinical research and proven safe in a phase 1 trial of healthy volunteers, according to GlycoMimetics, Inc., the company developing the drug.

Now, the company is recruiting adults with AML in a phase 1/2 study to test GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy.

“Having the FDA designate GMI-1271 as an orphan drug for the treatment of AML is an important accomplishment for GlycoMimetics,” said Helen Thackray, MD, vice president of clinical development and chief medical officer at GlycoMimetics. “This is a significant regulatory milestone for our program.”

The FDA’s orphan drug designation program is designed to promote the development of drugs intended to treat diseases affecting fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

Orphan designation provides a drug’s developer with benefits such as a 7-year period of marketing exclusivity if the drug is approved, protocol assistance, the ability to apply for research funding, tax credits for certain research expenses, and regulatory fee waivers.

Research with GMI-1271

Preclinical research presented at ASH 2013 suggested that GMI-1271 was able to overcome chemotherapy resistance in AML cells in vitro. The drug also reduced the leukemic burden in mouse models of AML when given in combination with daunorubicin and cytarabine.

Murine research presented at ASH 2014 suggested that, by inhibiting E-selectin, GMI-1271 may increase leukemic stem cells’ sensitivity to chemotherapeutic drugs.

At the same meeting, researchers presented preclinical data on GMI-1271 as a treatment for chronic myeloid leukemia, multiple myeloma, and venous thromboembolism.

In November 2014, GlycoMimetics announced results of phase 1 trial of GMI-1271 in healthy volunteers. Twenty-eight adults were enrolled in cohorts to receive the drug at 3 dose levels.

The company said subjects tolerated GMI-1271 well, and pharmacokinetics were as predicted based on preclinical research.

A multicenter, phase 1/2 trial of GMI-1271 in combination with chemotherapy is now recruiting adult patients with AML. ![]()

Who is going to make the wise choice?

Failure of academic medicine to improve value will undermine professionalism and threaten autonomy because outside forces, such as insurers and regulators, will surely impose change if academic leaders and physicians fail. [1]

The verdict is indoctors order too many tests. This problem is most prominent in academic health centers (AHCs), where the use of testing resources is higher than in community hospitals.[2] Most prior attempts to improve the value of care at AHCs have been driven by faculty and hospital administration in a top‐down fashion with only transient success.[3] We believe that successful and sustainable change should start with the housestaff, who are training in a system afflicted by wasteful overuse of healthcare resources. Therefore, we created a housestaff‐led initiative called the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee to change the culture of academic medicine. If AHCs are going to start choosing wisely, housestaff must be part of the engine behind the change.

FORMING THE VANDERBILT CHOOSING WISELY STEERING COMMITTEE

The idea for the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee (VCWSC) was born in December 2013 during a monthly Graduate Medical Education Committee meeting involving housestaff and faculty representatives from multiple subspecialties. At that time, the national Choosing Wisely campaign was in full stride, with more than 50 organizations having proposed top 5 lists of tests and procedures that should be questioned.[4] Several participants at the meeting decided to create a steering committee to integrate these proposals into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Housestaff have formed the core of the VCWSC from the beginning. The initial members were residents on the Graduate Medical Education Committee, including a fifth‐year radiology resident and a second‐year internal medicine resident who served as the first co‐chairs. More housestaff were recruited by email and word‐of‐mouth. Currently, the committee is composed of residents from the departments of internal medicine, radiology, pediatrics, neurology, anesthesiology, pathology, and general surgery. These residents perform all of the committee's vital functions, including organizing biweekly meetings, brainstorming and carrying out high‐value care initiatives, and recruiting new members. Of course, this committee would not have the authority to create real change without the guidance of numerous faculty supporters, including the designated institutional official and the associate vice chancellor for health affairs. However, we firmly believe that the primary reason this committee has been successful is that it is led by housestaff.

THE IMPORTANCE OF HOUSESTAFF LEADERSHIP

Residents are at the front line of care delivery at academic health centers (AHCs). Innumerable tests and procedures at these institutions are ordered and performed by housestaff. Therefore, culture change in academic medicine will not occur without housestaff culture change. Unfortunately, residents have been shown to have a lower level of competency with regard to high‐value care than more experienced providers.[5] The housestaff‐led VCWSC is uniquely positioned to address this problem by using personal experience and peer‐to‐peer communication to address the fears, biases, and knowledge gaps that cause trainees to waste healthcare resources. Resident members of the VCWSC wrestle daily with the temptation to overtest to avoid missing something or make a rare diagnosis. They are familiar with the systems that encourage overutilization, like shortcuts in ordering software that allow automatically recurring orders. Perhaps most importantly, they are able to discuss high‐value care with other trainees as equals, instead of trying to enforce compliance with a set of restrictions put in place by supervisors.

A SYSTEMATIC STRATEGY FOR EFFECTING CHANGE

To successfully implement high‐value care initiatives, the VCWSC follows a strategy proposed by John Kotter for effecting change in large organizations.[6] According to Kotter, it is critical to create a vision for change, communicate the vision effectively, and empower others to act on the vision. The VCWSC's vision for change is to encourage optimal medical practice by implementing Choosing Wisely top 5 recommendations. To communicate this vision, the VCWSC follows the rhetorical style of the national Choosing Wisely campaign. The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation researched this rhetoric extensively in the years leading up to the development of the top 5 lists. They found that simply asking providers to judiciously distribute healthcare resources often created a feeling of patient abandonment. Instead, providers are much more likely to respond to messages that encourage wise choices that enhance professional fulfillment, patient well‐being, and the overall quality of care.[4] Therefore, the VCWSC emphasizes these same values in its e‐mails, fliers, and presentations. Importantly, the VCWSC does not directly limit providers abilities to order tests or perform procedures. Instead, the VCWSC uses education and data to empower others to act on the Choosing Wisely vision for high‐value care.

After communicating the vision for change, Kotter recommends sustaining the vision by creating short‐term wins.[6] To demonstrate these wins, the VCWSC collects data on the effects of its initiatives and celebrates the success of individuals and teams through regular widely distributed emails. Initially this involved manually counting the number of tests ordered by many providers. Fortunately, experts from the Department of Bioinformatics partnered with the VCWSC to create an automated data collection system that is much more efficient, enabling the committee to quickly collect and analyze data on tests and procedures at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. These data are fed back to participants in various initiatives, and they are used to demonstrate the efficacy of these initiatives to others throughout the medical center, thus garnering trust and encouraging others to participate in VCWSC projects. With enough short‐term wins, the VCWSC hopes to achieve Kotter's ultimate goal, which is to consolidate and institutionalize changes to have a lasting impact.[6]

REDUCING DAILY LABSAN EARLY SUCCESS OF THE VCWSC

One example of the committee's early success is the reduction of routine complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMPs) on internal medicine services, as recommended in the Choosing Wisely top 5 list proposed by the Society of Hospital Medicine. Prior studies on reducing routine labs required interventions like displaying charges at the time of test ordering,[7, 8] using financial incentives,[2, 9] and eliminating the ability to order recurring daily labs.[10] Instead of replicating these efforts, the VCWSC decided to use an educational campaign and real‐time data feedback to focus on the root of the problema culture of overtesting. After obtaining the support of the internal medicine residency program leadership, the VCWSC distributed an evidence‐based flier (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article) summarizing the harms of and misconceptions surrounding excessive lab testing. These data were also presented at housestaff conferences.

Following this initial educational intervention, the VCWSC began tracking the labs ordered for patients on housestaff internal medicine teams to see what proportion have a BMP or CBC drawn each day of their hospitalization. Each week, the teams are sent an email with their lab rate compared to the lab rates of analogous teams. At the end of each month, all internal medicine housestaff and faculty are notified which teams had the lowest lab rate for the month. The VCWSC does not attempt to define an unnecessary lab or offer incentives; the teams are simply reminded that ordering fewer labs can be good for patient care. Since the initiative began, the teams have succeeded in reducing the percentage of patients receiving a CBC and BMP each day from an average of 90% to below 70%.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Moving forward, the VCWSC hopes to further engrain the culture of Choosing Wisely into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The labs initiative has expanded to many services including surgery, neurology, and the medical intensive care unit. Other initiatives are focusing on excessive telemetry monitoring and daily chest radiographs in intensive care units. In addition, the VCWSC is collaborating with other AHCs to help them implement their own Choosing Wisely projects.

A CALL FOR MORE HOUSESTAFF CHOOSING WISELY INITIATIVES

Housestaff are perfectly positioned to lead a change in the culture of academic medicine toward high‐value care. The VCWSC has already seen promising results, and we hope that similar initiatives will be created at AHCs across the country. By following John Kotter's recommendations for implementing change and using the Choosing Wisely top 5 lists as a guide, housestaff‐run committees like the VCWSC have the potential to change the culture of medicine at every AHC. If we do not want outside regulators to decide the future of academic medicine, we must find a way to cut down on wasteful spending and unnecessary testing. Residents everywhere, let us choose wisely together.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study acknowledge the faculty, residents, and medical students who have supported the efforts of the Vanderbilt University Choosing Wisely Steering Committee.

Disclosures: Dr. Brady serves on the board of the ACGME but receives no financial payment other than compensation for travel expenses to board meetings. He also was Chair of the Board for the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare in 2014.

- , , Teaching value in academic environments. Shifting the ivory tower. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1671–1672.

- , , , , A trial of two strategies to modify the test‐ordering behavior of medical residents. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(23):1330–1336.

- , , , Techniques to improve physicians' use of diagnostic tests: a new conceptual framework. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2020–2027.

- , , Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990–995.

- , , , , , “Choosing Wisely” in an academic department of medicine [published online June 26, 2014]. Am J Med Qual. doi:10.1177/1062860614540982.

- Leading change; why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 1995;March‐April:57–67.

- , , , et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903–908.

- , , The effect on test ordering of informing physicians of the charges for outpatient diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1499–1504.

- , , , et al. Targeted reduction in neurosurgical laboratory utilization: resident‐led effort at a single academic institution. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(1):173–177.

- , , , et al. The impact of peer management on test‐ordering behavior. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):196–204.

Failure of academic medicine to improve value will undermine professionalism and threaten autonomy because outside forces, such as insurers and regulators, will surely impose change if academic leaders and physicians fail. [1]

The verdict is indoctors order too many tests. This problem is most prominent in academic health centers (AHCs), where the use of testing resources is higher than in community hospitals.[2] Most prior attempts to improve the value of care at AHCs have been driven by faculty and hospital administration in a top‐down fashion with only transient success.[3] We believe that successful and sustainable change should start with the housestaff, who are training in a system afflicted by wasteful overuse of healthcare resources. Therefore, we created a housestaff‐led initiative called the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee to change the culture of academic medicine. If AHCs are going to start choosing wisely, housestaff must be part of the engine behind the change.

FORMING THE VANDERBILT CHOOSING WISELY STEERING COMMITTEE

The idea for the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee (VCWSC) was born in December 2013 during a monthly Graduate Medical Education Committee meeting involving housestaff and faculty representatives from multiple subspecialties. At that time, the national Choosing Wisely campaign was in full stride, with more than 50 organizations having proposed top 5 lists of tests and procedures that should be questioned.[4] Several participants at the meeting decided to create a steering committee to integrate these proposals into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Housestaff have formed the core of the VCWSC from the beginning. The initial members were residents on the Graduate Medical Education Committee, including a fifth‐year radiology resident and a second‐year internal medicine resident who served as the first co‐chairs. More housestaff were recruited by email and word‐of‐mouth. Currently, the committee is composed of residents from the departments of internal medicine, radiology, pediatrics, neurology, anesthesiology, pathology, and general surgery. These residents perform all of the committee's vital functions, including organizing biweekly meetings, brainstorming and carrying out high‐value care initiatives, and recruiting new members. Of course, this committee would not have the authority to create real change without the guidance of numerous faculty supporters, including the designated institutional official and the associate vice chancellor for health affairs. However, we firmly believe that the primary reason this committee has been successful is that it is led by housestaff.

THE IMPORTANCE OF HOUSESTAFF LEADERSHIP

Residents are at the front line of care delivery at academic health centers (AHCs). Innumerable tests and procedures at these institutions are ordered and performed by housestaff. Therefore, culture change in academic medicine will not occur without housestaff culture change. Unfortunately, residents have been shown to have a lower level of competency with regard to high‐value care than more experienced providers.[5] The housestaff‐led VCWSC is uniquely positioned to address this problem by using personal experience and peer‐to‐peer communication to address the fears, biases, and knowledge gaps that cause trainees to waste healthcare resources. Resident members of the VCWSC wrestle daily with the temptation to overtest to avoid missing something or make a rare diagnosis. They are familiar with the systems that encourage overutilization, like shortcuts in ordering software that allow automatically recurring orders. Perhaps most importantly, they are able to discuss high‐value care with other trainees as equals, instead of trying to enforce compliance with a set of restrictions put in place by supervisors.

A SYSTEMATIC STRATEGY FOR EFFECTING CHANGE

To successfully implement high‐value care initiatives, the VCWSC follows a strategy proposed by John Kotter for effecting change in large organizations.[6] According to Kotter, it is critical to create a vision for change, communicate the vision effectively, and empower others to act on the vision. The VCWSC's vision for change is to encourage optimal medical practice by implementing Choosing Wisely top 5 recommendations. To communicate this vision, the VCWSC follows the rhetorical style of the national Choosing Wisely campaign. The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation researched this rhetoric extensively in the years leading up to the development of the top 5 lists. They found that simply asking providers to judiciously distribute healthcare resources often created a feeling of patient abandonment. Instead, providers are much more likely to respond to messages that encourage wise choices that enhance professional fulfillment, patient well‐being, and the overall quality of care.[4] Therefore, the VCWSC emphasizes these same values in its e‐mails, fliers, and presentations. Importantly, the VCWSC does not directly limit providers abilities to order tests or perform procedures. Instead, the VCWSC uses education and data to empower others to act on the Choosing Wisely vision for high‐value care.

After communicating the vision for change, Kotter recommends sustaining the vision by creating short‐term wins.[6] To demonstrate these wins, the VCWSC collects data on the effects of its initiatives and celebrates the success of individuals and teams through regular widely distributed emails. Initially this involved manually counting the number of tests ordered by many providers. Fortunately, experts from the Department of Bioinformatics partnered with the VCWSC to create an automated data collection system that is much more efficient, enabling the committee to quickly collect and analyze data on tests and procedures at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. These data are fed back to participants in various initiatives, and they are used to demonstrate the efficacy of these initiatives to others throughout the medical center, thus garnering trust and encouraging others to participate in VCWSC projects. With enough short‐term wins, the VCWSC hopes to achieve Kotter's ultimate goal, which is to consolidate and institutionalize changes to have a lasting impact.[6]

REDUCING DAILY LABSAN EARLY SUCCESS OF THE VCWSC

One example of the committee's early success is the reduction of routine complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMPs) on internal medicine services, as recommended in the Choosing Wisely top 5 list proposed by the Society of Hospital Medicine. Prior studies on reducing routine labs required interventions like displaying charges at the time of test ordering,[7, 8] using financial incentives,[2, 9] and eliminating the ability to order recurring daily labs.[10] Instead of replicating these efforts, the VCWSC decided to use an educational campaign and real‐time data feedback to focus on the root of the problema culture of overtesting. After obtaining the support of the internal medicine residency program leadership, the VCWSC distributed an evidence‐based flier (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article) summarizing the harms of and misconceptions surrounding excessive lab testing. These data were also presented at housestaff conferences.

Following this initial educational intervention, the VCWSC began tracking the labs ordered for patients on housestaff internal medicine teams to see what proportion have a BMP or CBC drawn each day of their hospitalization. Each week, the teams are sent an email with their lab rate compared to the lab rates of analogous teams. At the end of each month, all internal medicine housestaff and faculty are notified which teams had the lowest lab rate for the month. The VCWSC does not attempt to define an unnecessary lab or offer incentives; the teams are simply reminded that ordering fewer labs can be good for patient care. Since the initiative began, the teams have succeeded in reducing the percentage of patients receiving a CBC and BMP each day from an average of 90% to below 70%.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Moving forward, the VCWSC hopes to further engrain the culture of Choosing Wisely into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The labs initiative has expanded to many services including surgery, neurology, and the medical intensive care unit. Other initiatives are focusing on excessive telemetry monitoring and daily chest radiographs in intensive care units. In addition, the VCWSC is collaborating with other AHCs to help them implement their own Choosing Wisely projects.

A CALL FOR MORE HOUSESTAFF CHOOSING WISELY INITIATIVES

Housestaff are perfectly positioned to lead a change in the culture of academic medicine toward high‐value care. The VCWSC has already seen promising results, and we hope that similar initiatives will be created at AHCs across the country. By following John Kotter's recommendations for implementing change and using the Choosing Wisely top 5 lists as a guide, housestaff‐run committees like the VCWSC have the potential to change the culture of medicine at every AHC. If we do not want outside regulators to decide the future of academic medicine, we must find a way to cut down on wasteful spending and unnecessary testing. Residents everywhere, let us choose wisely together.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study acknowledge the faculty, residents, and medical students who have supported the efforts of the Vanderbilt University Choosing Wisely Steering Committee.

Disclosures: Dr. Brady serves on the board of the ACGME but receives no financial payment other than compensation for travel expenses to board meetings. He also was Chair of the Board for the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare in 2014.

Failure of academic medicine to improve value will undermine professionalism and threaten autonomy because outside forces, such as insurers and regulators, will surely impose change if academic leaders and physicians fail. [1]

The verdict is indoctors order too many tests. This problem is most prominent in academic health centers (AHCs), where the use of testing resources is higher than in community hospitals.[2] Most prior attempts to improve the value of care at AHCs have been driven by faculty and hospital administration in a top‐down fashion with only transient success.[3] We believe that successful and sustainable change should start with the housestaff, who are training in a system afflicted by wasteful overuse of healthcare resources. Therefore, we created a housestaff‐led initiative called the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee to change the culture of academic medicine. If AHCs are going to start choosing wisely, housestaff must be part of the engine behind the change.

FORMING THE VANDERBILT CHOOSING WISELY STEERING COMMITTEE

The idea for the Vanderbilt Choosing Wisely Steering Committee (VCWSC) was born in December 2013 during a monthly Graduate Medical Education Committee meeting involving housestaff and faculty representatives from multiple subspecialties. At that time, the national Choosing Wisely campaign was in full stride, with more than 50 organizations having proposed top 5 lists of tests and procedures that should be questioned.[4] Several participants at the meeting decided to create a steering committee to integrate these proposals into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

Housestaff have formed the core of the VCWSC from the beginning. The initial members were residents on the Graduate Medical Education Committee, including a fifth‐year radiology resident and a second‐year internal medicine resident who served as the first co‐chairs. More housestaff were recruited by email and word‐of‐mouth. Currently, the committee is composed of residents from the departments of internal medicine, radiology, pediatrics, neurology, anesthesiology, pathology, and general surgery. These residents perform all of the committee's vital functions, including organizing biweekly meetings, brainstorming and carrying out high‐value care initiatives, and recruiting new members. Of course, this committee would not have the authority to create real change without the guidance of numerous faculty supporters, including the designated institutional official and the associate vice chancellor for health affairs. However, we firmly believe that the primary reason this committee has been successful is that it is led by housestaff.

THE IMPORTANCE OF HOUSESTAFF LEADERSHIP

Residents are at the front line of care delivery at academic health centers (AHCs). Innumerable tests and procedures at these institutions are ordered and performed by housestaff. Therefore, culture change in academic medicine will not occur without housestaff culture change. Unfortunately, residents have been shown to have a lower level of competency with regard to high‐value care than more experienced providers.[5] The housestaff‐led VCWSC is uniquely positioned to address this problem by using personal experience and peer‐to‐peer communication to address the fears, biases, and knowledge gaps that cause trainees to waste healthcare resources. Resident members of the VCWSC wrestle daily with the temptation to overtest to avoid missing something or make a rare diagnosis. They are familiar with the systems that encourage overutilization, like shortcuts in ordering software that allow automatically recurring orders. Perhaps most importantly, they are able to discuss high‐value care with other trainees as equals, instead of trying to enforce compliance with a set of restrictions put in place by supervisors.

A SYSTEMATIC STRATEGY FOR EFFECTING CHANGE

To successfully implement high‐value care initiatives, the VCWSC follows a strategy proposed by John Kotter for effecting change in large organizations.[6] According to Kotter, it is critical to create a vision for change, communicate the vision effectively, and empower others to act on the vision. The VCWSC's vision for change is to encourage optimal medical practice by implementing Choosing Wisely top 5 recommendations. To communicate this vision, the VCWSC follows the rhetorical style of the national Choosing Wisely campaign. The American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation researched this rhetoric extensively in the years leading up to the development of the top 5 lists. They found that simply asking providers to judiciously distribute healthcare resources often created a feeling of patient abandonment. Instead, providers are much more likely to respond to messages that encourage wise choices that enhance professional fulfillment, patient well‐being, and the overall quality of care.[4] Therefore, the VCWSC emphasizes these same values in its e‐mails, fliers, and presentations. Importantly, the VCWSC does not directly limit providers abilities to order tests or perform procedures. Instead, the VCWSC uses education and data to empower others to act on the Choosing Wisely vision for high‐value care.

After communicating the vision for change, Kotter recommends sustaining the vision by creating short‐term wins.[6] To demonstrate these wins, the VCWSC collects data on the effects of its initiatives and celebrates the success of individuals and teams through regular widely distributed emails. Initially this involved manually counting the number of tests ordered by many providers. Fortunately, experts from the Department of Bioinformatics partnered with the VCWSC to create an automated data collection system that is much more efficient, enabling the committee to quickly collect and analyze data on tests and procedures at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. These data are fed back to participants in various initiatives, and they are used to demonstrate the efficacy of these initiatives to others throughout the medical center, thus garnering trust and encouraging others to participate in VCWSC projects. With enough short‐term wins, the VCWSC hopes to achieve Kotter's ultimate goal, which is to consolidate and institutionalize changes to have a lasting impact.[6]

REDUCING DAILY LABSAN EARLY SUCCESS OF THE VCWSC

One example of the committee's early success is the reduction of routine complete blood counts (CBCs) and basic metabolic panels (BMPs) on internal medicine services, as recommended in the Choosing Wisely top 5 list proposed by the Society of Hospital Medicine. Prior studies on reducing routine labs required interventions like displaying charges at the time of test ordering,[7, 8] using financial incentives,[2, 9] and eliminating the ability to order recurring daily labs.[10] Instead of replicating these efforts, the VCWSC decided to use an educational campaign and real‐time data feedback to focus on the root of the problema culture of overtesting. After obtaining the support of the internal medicine residency program leadership, the VCWSC distributed an evidence‐based flier (see Supporting Information in the online version of this article) summarizing the harms of and misconceptions surrounding excessive lab testing. These data were also presented at housestaff conferences.

Following this initial educational intervention, the VCWSC began tracking the labs ordered for patients on housestaff internal medicine teams to see what proportion have a BMP or CBC drawn each day of their hospitalization. Each week, the teams are sent an email with their lab rate compared to the lab rates of analogous teams. At the end of each month, all internal medicine housestaff and faculty are notified which teams had the lowest lab rate for the month. The VCWSC does not attempt to define an unnecessary lab or offer incentives; the teams are simply reminded that ordering fewer labs can be good for patient care. Since the initiative began, the teams have succeeded in reducing the percentage of patients receiving a CBC and BMP each day from an average of 90% to below 70%.

FUTURE DIRECTIONS

Moving forward, the VCWSC hopes to further engrain the culture of Choosing Wisely into daily practice at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. The labs initiative has expanded to many services including surgery, neurology, and the medical intensive care unit. Other initiatives are focusing on excessive telemetry monitoring and daily chest radiographs in intensive care units. In addition, the VCWSC is collaborating with other AHCs to help them implement their own Choosing Wisely projects.

A CALL FOR MORE HOUSESTAFF CHOOSING WISELY INITIATIVES

Housestaff are perfectly positioned to lead a change in the culture of academic medicine toward high‐value care. The VCWSC has already seen promising results, and we hope that similar initiatives will be created at AHCs across the country. By following John Kotter's recommendations for implementing change and using the Choosing Wisely top 5 lists as a guide, housestaff‐run committees like the VCWSC have the potential to change the culture of medicine at every AHC. If we do not want outside regulators to decide the future of academic medicine, we must find a way to cut down on wasteful spending and unnecessary testing. Residents everywhere, let us choose wisely together.

Acknowledgements

The authors of this study acknowledge the faculty, residents, and medical students who have supported the efforts of the Vanderbilt University Choosing Wisely Steering Committee.

Disclosures: Dr. Brady serves on the board of the ACGME but receives no financial payment other than compensation for travel expenses to board meetings. He also was Chair of the Board for the American Academy on Communication in Healthcare in 2014.

- , , Teaching value in academic environments. Shifting the ivory tower. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1671–1672.

- , , , , A trial of two strategies to modify the test‐ordering behavior of medical residents. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(23):1330–1336.

- , , , Techniques to improve physicians' use of diagnostic tests: a new conceptual framework. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2020–2027.

- , , Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990–995.

- , , , , , “Choosing Wisely” in an academic department of medicine [published online June 26, 2014]. Am J Med Qual. doi:10.1177/1062860614540982.

- Leading change; why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 1995;March‐April:57–67.

- , , , et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903–908.

- , , The effect on test ordering of informing physicians of the charges for outpatient diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1499–1504.

- , , , et al. Targeted reduction in neurosurgical laboratory utilization: resident‐led effort at a single academic institution. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(1):173–177.

- , , , et al. The impact of peer management on test‐ordering behavior. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):196–204.

- , , Teaching value in academic environments. Shifting the ivory tower. JAMA. 2013;310(16):1671–1672.

- , , , , A trial of two strategies to modify the test‐ordering behavior of medical residents. N Engl J Med. 1980;303(23):1330–1336.

- , , , Techniques to improve physicians' use of diagnostic tests: a new conceptual framework. JAMA. 1998;280(23):2020–2027.

- , , Engaging physicians and consumers in conversations about treatment overuse and waste: a short history of the Choosing Wisely campaign. Acad Med. 2014;89(7):990–995.

- , , , , , “Choosing Wisely” in an academic department of medicine [published online June 26, 2014]. Am J Med Qual. doi:10.1177/1062860614540982.

- Leading change; why transformation efforts fail. Harv Bus Rev. 1995;March‐April:57–67.

- , , , et al. Impact of providing fee data on laboratory test ordering: a controlled clinical trial. JAMA Intern Med. 2013;173(10):903–908.

- , , The effect on test ordering of informing physicians of the charges for outpatient diagnostic tests. N Engl J Med. 1990;322(21):1499–1504.

- , , , et al. Targeted reduction in neurosurgical laboratory utilization: resident‐led effort at a single academic institution. J Neurosurg. 2014;120(1):173–177.

- , , , et al. The impact of peer management on test‐ordering behavior. Ann Intern Med. 2004;141(3):196–204.

After Great Recession, women at higher risk of anxiety

Women in the United States were more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety after the Great Recession than during or before the recession, according to Rada K. Dagher, Ph.D., and her associates.

During the recession, the odds ratio for an anxiety diagnosis in women was slightly higher than it was before the downturn, but not by a significant amount. Afterward, the OR nationwide was 1.17. Women living in the Northeast and Midwest were at a significantly higher risk than were women living in the other regions of the country, with ORs of 1.43 and 1.53, respectively. Women who were unemployed or whose household income stood at less than 100% of the federal poverty level also were at a higher risk.

In contrast, depression was less likely during and after the recession in both men and women. Men had a lower risk of an anxiety diagnosis and lower Kessler 6 scores post recession as well. In addition, a low household income and unemployment had little to no effect on mental illness risk, although men living in the Northeast were more likely to suffer from depression post recession, with an OR of 1.17.

“In general, past studies suggest higher vulnerability of men to the negative mental health consequences of economic recessions. However, this may not be the case anymore given the increasingly high labor force participation rate of women and work becoming an important part of the self-identity of the majority of women,” the investigators noted.

Future studies should investigate why depression diagnoses were lower, and whether those findings can be attributed to fewer visits to mental health providers, higher levels of social support, or “more time for exercise and leisure activities,” they wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124103).

Women in the United States were more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety after the Great Recession than during or before the recession, according to Rada K. Dagher, Ph.D., and her associates.

During the recession, the odds ratio for an anxiety diagnosis in women was slightly higher than it was before the downturn, but not by a significant amount. Afterward, the OR nationwide was 1.17. Women living in the Northeast and Midwest were at a significantly higher risk than were women living in the other regions of the country, with ORs of 1.43 and 1.53, respectively. Women who were unemployed or whose household income stood at less than 100% of the federal poverty level also were at a higher risk.

In contrast, depression was less likely during and after the recession in both men and women. Men had a lower risk of an anxiety diagnosis and lower Kessler 6 scores post recession as well. In addition, a low household income and unemployment had little to no effect on mental illness risk, although men living in the Northeast were more likely to suffer from depression post recession, with an OR of 1.17.

“In general, past studies suggest higher vulnerability of men to the negative mental health consequences of economic recessions. However, this may not be the case anymore given the increasingly high labor force participation rate of women and work becoming an important part of the self-identity of the majority of women,” the investigators noted.

Future studies should investigate why depression diagnoses were lower, and whether those findings can be attributed to fewer visits to mental health providers, higher levels of social support, or “more time for exercise and leisure activities,” they wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124103).

Women in the United States were more likely to be diagnosed with anxiety after the Great Recession than during or before the recession, according to Rada K. Dagher, Ph.D., and her associates.

During the recession, the odds ratio for an anxiety diagnosis in women was slightly higher than it was before the downturn, but not by a significant amount. Afterward, the OR nationwide was 1.17. Women living in the Northeast and Midwest were at a significantly higher risk than were women living in the other regions of the country, with ORs of 1.43 and 1.53, respectively. Women who were unemployed or whose household income stood at less than 100% of the federal poverty level also were at a higher risk.

In contrast, depression was less likely during and after the recession in both men and women. Men had a lower risk of an anxiety diagnosis and lower Kessler 6 scores post recession as well. In addition, a low household income and unemployment had little to no effect on mental illness risk, although men living in the Northeast were more likely to suffer from depression post recession, with an OR of 1.17.

“In general, past studies suggest higher vulnerability of men to the negative mental health consequences of economic recessions. However, this may not be the case anymore given the increasingly high labor force participation rate of women and work becoming an important part of the self-identity of the majority of women,” the investigators noted.

Future studies should investigate why depression diagnoses were lower, and whether those findings can be attributed to fewer visits to mental health providers, higher levels of social support, or “more time for exercise and leisure activities,” they wrote.

Find the full study in PLoS ONE (doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0124103).

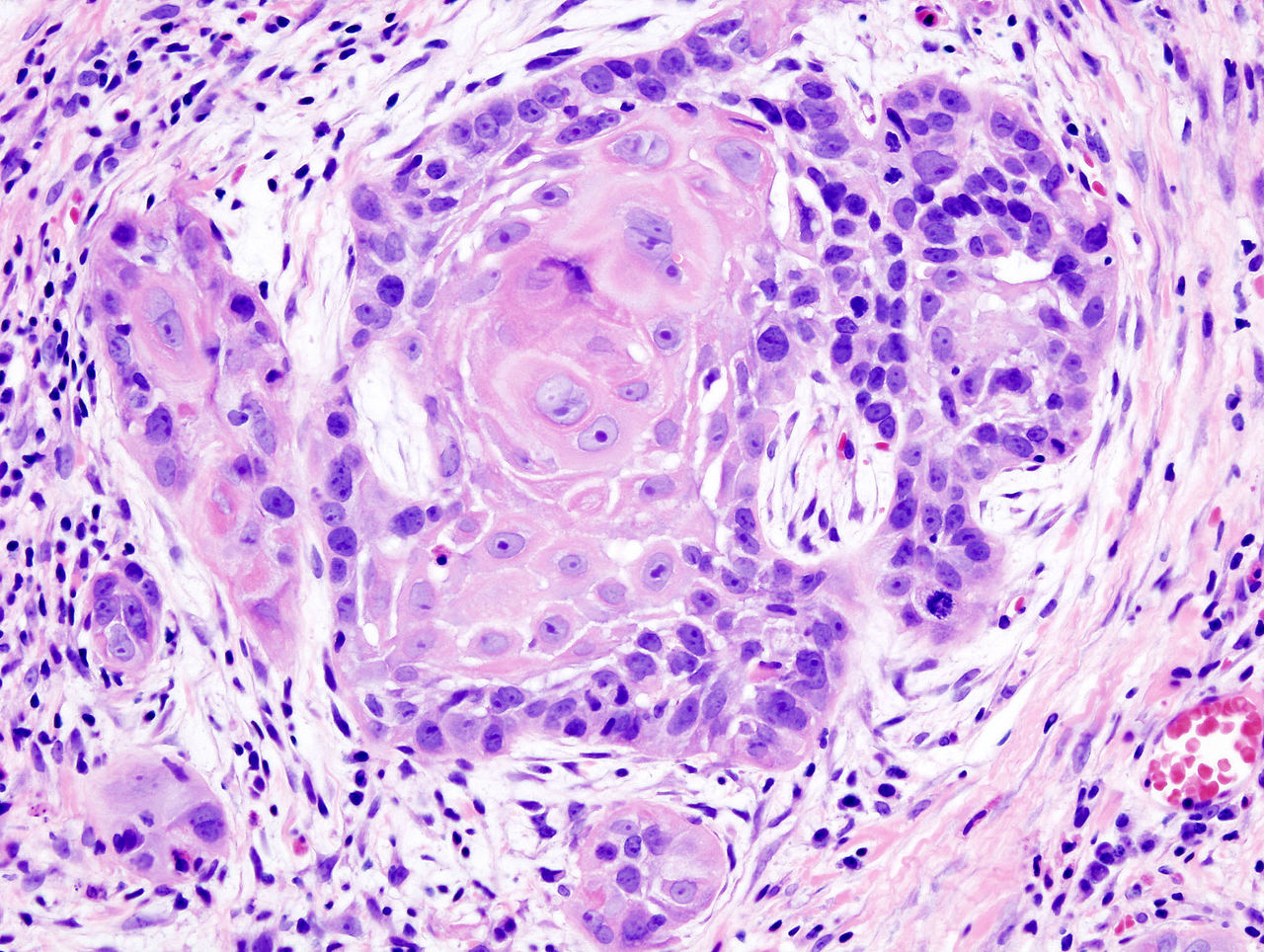

Oral cancer survival lower with positive margins, public insurance

In patients who underwent surgical treatment for stage I or II oral cavity squamous cell cancer, positive tumor margin, the use of radiation or chemotherapy, treatment in a nonacademic facility, and having public health insurance were significantly associated with lower 5-year survival rates, according to a retrospective analysis published online in the JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The findings suggest that some factors associated with lower 5-year survival rates “may be targets for quality improvement efforts,” wrote Alexander L. Luryi of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

Seventy percent of 6,830 patients who underwent surgery for stage I or II oral cavity squamous cell cancer (OCSCC) from 2003 to 2006 survived 5 years, according to information from the National Cancer Data Base.

Multivariate analysis showed higher survival rates were significantly associated with neck dissection (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .003). Lower survival rates were significantly associated with radiation therapy (HR, 1.31; P < .001), chemotherapy (HR, 1.34; P = .03), nonprivate insurance (HR Medicaid, 1.96; HR Medicare, 1.45; P < .001), and nonacademic treatment facility (HR, 1.13; P = .03).

Care at academic centers compared with nonacademic centers was associated with improved survival, possibly due to health care provider expertise, the study authors noted (JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015 May 14 [doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0719]).

Survival rates were lower in patients treated at nonacademic cancer centers, but multivariate analysis showed no association between facility-based case volume and survival. Patients insured through Medicaid and Medicare had significantly lower 5-year survival rates (P < .001 for both). That finding may be the result of inconsistent treatment and follow-up, the investigators said, or worse baseline health among that patient population.

Controversy exists over the relationship between positive margins and outcomes, and the implications for aggressiveness of surgery. The study found positive margins were significantly associated with poorer outcomes, the researchers noted, which supports the use of aggressive surgery in early OCSCC to achieve negative margins.

Radiation and chemotherapy were linked to worse outcomes, and those therapies were possibly indicators of less aggressive resection in localized disease. The analysis could not adjust for potential confounding effects of perineural and lymphovascular invasion, because the information was not recorded in the National Cancer Data Base.

The study indicated a positive impact by neck dissection on survival. Patients with occult neck disease who underwent neck dissection likely would have been restaged to stage III or higher and removed from the early stage sample, the authors explained, which would account for higher survival rates for those remaining. Prospective trials are needed to determine the role of elective neck dissection in early OCSCC, the researchers added.

The William U. Gardner Memorial Research Fund at Yale University supported the study. Dr. Luryi and coauthors reported having no disclosures.

In patients who underwent surgical treatment for stage I or II oral cavity squamous cell cancer, positive tumor margin, the use of radiation or chemotherapy, treatment in a nonacademic facility, and having public health insurance were significantly associated with lower 5-year survival rates, according to a retrospective analysis published online in the JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The findings suggest that some factors associated with lower 5-year survival rates “may be targets for quality improvement efforts,” wrote Alexander L. Luryi of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.

Seventy percent of 6,830 patients who underwent surgery for stage I or II oral cavity squamous cell cancer (OCSCC) from 2003 to 2006 survived 5 years, according to information from the National Cancer Data Base.

Multivariate analysis showed higher survival rates were significantly associated with neck dissection (hazard ratio, 0.85; P = .003). Lower survival rates were significantly associated with radiation therapy (HR, 1.31; P < .001), chemotherapy (HR, 1.34; P = .03), nonprivate insurance (HR Medicaid, 1.96; HR Medicare, 1.45; P < .001), and nonacademic treatment facility (HR, 1.13; P = .03).

Care at academic centers compared with nonacademic centers was associated with improved survival, possibly due to health care provider expertise, the study authors noted (JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2015 May 14 [doi:10.1001/jamaoto.2015.0719]).

Survival rates were lower in patients treated at nonacademic cancer centers, but multivariate analysis showed no association between facility-based case volume and survival. Patients insured through Medicaid and Medicare had significantly lower 5-year survival rates (P < .001 for both). That finding may be the result of inconsistent treatment and follow-up, the investigators said, or worse baseline health among that patient population.

Controversy exists over the relationship between positive margins and outcomes, and the implications for aggressiveness of surgery. The study found positive margins were significantly associated with poorer outcomes, the researchers noted, which supports the use of aggressive surgery in early OCSCC to achieve negative margins.

Radiation and chemotherapy were linked to worse outcomes, and those therapies were possibly indicators of less aggressive resection in localized disease. The analysis could not adjust for potential confounding effects of perineural and lymphovascular invasion, because the information was not recorded in the National Cancer Data Base.

The study indicated a positive impact by neck dissection on survival. Patients with occult neck disease who underwent neck dissection likely would have been restaged to stage III or higher and removed from the early stage sample, the authors explained, which would account for higher survival rates for those remaining. Prospective trials are needed to determine the role of elective neck dissection in early OCSCC, the researchers added.

The William U. Gardner Memorial Research Fund at Yale University supported the study. Dr. Luryi and coauthors reported having no disclosures.

In patients who underwent surgical treatment for stage I or II oral cavity squamous cell cancer, positive tumor margin, the use of radiation or chemotherapy, treatment in a nonacademic facility, and having public health insurance were significantly associated with lower 5-year survival rates, according to a retrospective analysis published online in the JAMA Otolaryngology–Head & Neck Surgery.

The findings suggest that some factors associated with lower 5-year survival rates “may be targets for quality improvement efforts,” wrote Alexander L. Luryi of Yale University, New Haven, Conn., and colleagues.