User login

Using maternal triglyceride levels as a marker for pregnancy risk

It is widely known and taught that maternal blood lipid levels increase slightly during pregnancy. Lipid values throughout pregnancy, however, have not been well described, making it difficult to ascertain which changes are normal and which changes may be potentially troubling for the mother and/or the baby.

Similarly, the association between pregnancy outcomes and lipid levels prior to conception and during pregnancy has been studied only minimally. In both areas, more research is needed.

Yet despite the need for more research, it now appears that the mother’s lipid profile – particularly her triglyceride levels before and during pregnancy – warrants our attention. Results from several clinical studies suggest that elevated maternal triglyceride (TG) levels may be associated with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and preeclampsia. Since these conditions can contribute to the development of peri- and postpartum complications and increase the mother’s risk of developing subsequent type 2 diabetes and systemic hypertension, a mother’s lipid profile – just like her glucose levels – may help us define who is at high risk of pregnancy complications and later adverse effects.

Research findings

In addition to assessing fetal health during pregnancy, ob.gyns. routinely measure and monitor maternal blood pressure, weight gain, and blood sugar, which fluctuate during normal pregnancies.

We have found that lipid levels, notably maternal TG, total cholesterol, and the major particles of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) also vary during pregnancy, with a nadir during the first trimester, followed by a gradual increase and a peaking before delivery.

It is well known that severely elevated blood pressure, gestational weight, or glucose can signify a pregnancy at risk for adverse outcomes. However, our research has shown that high levels of TGs, but not the levels of HDLs, LDLs, or total cholesterol, during pregnancy also are associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:482.e1-8).

In our study, the rate of preeclampsia or GDM increased with maternal TG level, from 7.2% in women who had the lowest levels (<25th percentile) to 19.8% in women who had the highest levels (>75th percentile).

We found that TG levels in the upper quartile also were associated with a significantly higher risk of preeclampsia, compared with the lower quartile (relative risk, 1.87).

Similarly, among women without diagnosed GDM, those with TG levels in the upper quartile were more likely to have a fasting glucose level of 100 mg/dL or more, compared with the intermediate group (TG level between the 25th and 75th percentiles) and the lower quartile. Women with the highest TG levels also were more likely to have infants classified as large for gestational age.

Our findings are consistent with a review that showed a positive association between elevated maternal TG and the risk of preeclampsia (BJOG 2006;113:379-86), as well as a cohort study that found plasma TG levels in the first trimester were independently and linearly associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, and large-for-gestational age (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:3917-25).

Interestingly, the cohort study did not show an association between elevated maternal TG levels, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and body mass index. This suggests that weight gain and TG may be independent risk factors.

In practice

At this point in time, without defined cut-off values and well-tested interventions, there is no recommendation regarding maternal lipid measurement during pregnancy. We have shown, however, that maternal TG levels above 140 mg/dL at 3 months’ gestation and TG levels of 200 mg/dL or more at 6 months’ gestation are very high and may indicate a high-risk pregnancy.

Like all ob.gyns., we advise women before pregnancy to lose weight and to normalize blood glucose levels before attempting to conceive to reduce pregnancy complications, but we also encourage our patients to lower their TG levels. Given the observed associations between higher TG levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we now routinely measure maternal lipids as well as blood glucose in our pregnant patients. We also test lipid levels in pregnant women who have other risk factors such as GDM in a prior pregnancy or chronic high blood pressure.

It is possible that lifestyle programs (such as those involving diet, weight reduction, and physical activity) prior to and during pregnancy, with a focus not only on maintaining a healthy weight but also on lowering TG levels, may help to further prevent complications during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Although more research is needed, lowering TGs with cholesterol-reducing drugs also may help improve pregnancy outcomes. Indeed, there is currently a study investigating the pharmacologic treatment of high lipids during pregnancy.

For now, we should advise our patients who have higher TG levels in pregnancy to improve their diets and levels of physical activity. We also should monitor these patients for the increased likelihood of developing GDM and preeclampsia because higher lipid profiles appear to equate to a higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Finally, our attention to lipid profiles should extend beyond birth, since the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease may be influenced by preeclampsia and potentially by the lipid changes that escalate with the condition.

Dr. Wiznitzer reported having no financial disclosures related to this Master Class.

It is widely known and taught that maternal blood lipid levels increase slightly during pregnancy. Lipid values throughout pregnancy, however, have not been well described, making it difficult to ascertain which changes are normal and which changes may be potentially troubling for the mother and/or the baby.

Similarly, the association between pregnancy outcomes and lipid levels prior to conception and during pregnancy has been studied only minimally. In both areas, more research is needed.

Yet despite the need for more research, it now appears that the mother’s lipid profile – particularly her triglyceride levels before and during pregnancy – warrants our attention. Results from several clinical studies suggest that elevated maternal triglyceride (TG) levels may be associated with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and preeclampsia. Since these conditions can contribute to the development of peri- and postpartum complications and increase the mother’s risk of developing subsequent type 2 diabetes and systemic hypertension, a mother’s lipid profile – just like her glucose levels – may help us define who is at high risk of pregnancy complications and later adverse effects.

Research findings

In addition to assessing fetal health during pregnancy, ob.gyns. routinely measure and monitor maternal blood pressure, weight gain, and blood sugar, which fluctuate during normal pregnancies.

We have found that lipid levels, notably maternal TG, total cholesterol, and the major particles of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) also vary during pregnancy, with a nadir during the first trimester, followed by a gradual increase and a peaking before delivery.

It is well known that severely elevated blood pressure, gestational weight, or glucose can signify a pregnancy at risk for adverse outcomes. However, our research has shown that high levels of TGs, but not the levels of HDLs, LDLs, or total cholesterol, during pregnancy also are associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:482.e1-8).

In our study, the rate of preeclampsia or GDM increased with maternal TG level, from 7.2% in women who had the lowest levels (<25th percentile) to 19.8% in women who had the highest levels (>75th percentile).

We found that TG levels in the upper quartile also were associated with a significantly higher risk of preeclampsia, compared with the lower quartile (relative risk, 1.87).

Similarly, among women without diagnosed GDM, those with TG levels in the upper quartile were more likely to have a fasting glucose level of 100 mg/dL or more, compared with the intermediate group (TG level between the 25th and 75th percentiles) and the lower quartile. Women with the highest TG levels also were more likely to have infants classified as large for gestational age.

Our findings are consistent with a review that showed a positive association between elevated maternal TG and the risk of preeclampsia (BJOG 2006;113:379-86), as well as a cohort study that found plasma TG levels in the first trimester were independently and linearly associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, and large-for-gestational age (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:3917-25).

Interestingly, the cohort study did not show an association between elevated maternal TG levels, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and body mass index. This suggests that weight gain and TG may be independent risk factors.

In practice

At this point in time, without defined cut-off values and well-tested interventions, there is no recommendation regarding maternal lipid measurement during pregnancy. We have shown, however, that maternal TG levels above 140 mg/dL at 3 months’ gestation and TG levels of 200 mg/dL or more at 6 months’ gestation are very high and may indicate a high-risk pregnancy.

Like all ob.gyns., we advise women before pregnancy to lose weight and to normalize blood glucose levels before attempting to conceive to reduce pregnancy complications, but we also encourage our patients to lower their TG levels. Given the observed associations between higher TG levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we now routinely measure maternal lipids as well as blood glucose in our pregnant patients. We also test lipid levels in pregnant women who have other risk factors such as GDM in a prior pregnancy or chronic high blood pressure.

It is possible that lifestyle programs (such as those involving diet, weight reduction, and physical activity) prior to and during pregnancy, with a focus not only on maintaining a healthy weight but also on lowering TG levels, may help to further prevent complications during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Although more research is needed, lowering TGs with cholesterol-reducing drugs also may help improve pregnancy outcomes. Indeed, there is currently a study investigating the pharmacologic treatment of high lipids during pregnancy.

For now, we should advise our patients who have higher TG levels in pregnancy to improve their diets and levels of physical activity. We also should monitor these patients for the increased likelihood of developing GDM and preeclampsia because higher lipid profiles appear to equate to a higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Finally, our attention to lipid profiles should extend beyond birth, since the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease may be influenced by preeclampsia and potentially by the lipid changes that escalate with the condition.

Dr. Wiznitzer reported having no financial disclosures related to this Master Class.

It is widely known and taught that maternal blood lipid levels increase slightly during pregnancy. Lipid values throughout pregnancy, however, have not been well described, making it difficult to ascertain which changes are normal and which changes may be potentially troubling for the mother and/or the baby.

Similarly, the association between pregnancy outcomes and lipid levels prior to conception and during pregnancy has been studied only minimally. In both areas, more research is needed.

Yet despite the need for more research, it now appears that the mother’s lipid profile – particularly her triglyceride levels before and during pregnancy – warrants our attention. Results from several clinical studies suggest that elevated maternal triglyceride (TG) levels may be associated with gestational diabetes mellitus (GDM) and preeclampsia. Since these conditions can contribute to the development of peri- and postpartum complications and increase the mother’s risk of developing subsequent type 2 diabetes and systemic hypertension, a mother’s lipid profile – just like her glucose levels – may help us define who is at high risk of pregnancy complications and later adverse effects.

Research findings

In addition to assessing fetal health during pregnancy, ob.gyns. routinely measure and monitor maternal blood pressure, weight gain, and blood sugar, which fluctuate during normal pregnancies.

We have found that lipid levels, notably maternal TG, total cholesterol, and the major particles of high-density lipoproteins (HDLs) and low-density lipoproteins (LDLs) also vary during pregnancy, with a nadir during the first trimester, followed by a gradual increase and a peaking before delivery.

It is well known that severely elevated blood pressure, gestational weight, or glucose can signify a pregnancy at risk for adverse outcomes. However, our research has shown that high levels of TGs, but not the levels of HDLs, LDLs, or total cholesterol, during pregnancy also are associated with an increased risk for preeclampsia and gestational diabetes mellitus (Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2009;201:482.e1-8).

In our study, the rate of preeclampsia or GDM increased with maternal TG level, from 7.2% in women who had the lowest levels (<25th percentile) to 19.8% in women who had the highest levels (>75th percentile).

We found that TG levels in the upper quartile also were associated with a significantly higher risk of preeclampsia, compared with the lower quartile (relative risk, 1.87).

Similarly, among women without diagnosed GDM, those with TG levels in the upper quartile were more likely to have a fasting glucose level of 100 mg/dL or more, compared with the intermediate group (TG level between the 25th and 75th percentiles) and the lower quartile. Women with the highest TG levels also were more likely to have infants classified as large for gestational age.

Our findings are consistent with a review that showed a positive association between elevated maternal TG and the risk of preeclampsia (BJOG 2006;113:379-86), as well as a cohort study that found plasma TG levels in the first trimester were independently and linearly associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension, preeclampsia, and large-for-gestational age (J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2012;97:3917-25).

Interestingly, the cohort study did not show an association between elevated maternal TG levels, adverse pregnancy outcomes, and body mass index. This suggests that weight gain and TG may be independent risk factors.

In practice

At this point in time, without defined cut-off values and well-tested interventions, there is no recommendation regarding maternal lipid measurement during pregnancy. We have shown, however, that maternal TG levels above 140 mg/dL at 3 months’ gestation and TG levels of 200 mg/dL or more at 6 months’ gestation are very high and may indicate a high-risk pregnancy.

Like all ob.gyns., we advise women before pregnancy to lose weight and to normalize blood glucose levels before attempting to conceive to reduce pregnancy complications, but we also encourage our patients to lower their TG levels. Given the observed associations between higher TG levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes, we now routinely measure maternal lipids as well as blood glucose in our pregnant patients. We also test lipid levels in pregnant women who have other risk factors such as GDM in a prior pregnancy or chronic high blood pressure.

It is possible that lifestyle programs (such as those involving diet, weight reduction, and physical activity) prior to and during pregnancy, with a focus not only on maintaining a healthy weight but also on lowering TG levels, may help to further prevent complications during pregnancy and adverse birth outcomes. Although more research is needed, lowering TGs with cholesterol-reducing drugs also may help improve pregnancy outcomes. Indeed, there is currently a study investigating the pharmacologic treatment of high lipids during pregnancy.

For now, we should advise our patients who have higher TG levels in pregnancy to improve their diets and levels of physical activity. We also should monitor these patients for the increased likelihood of developing GDM and preeclampsia because higher lipid profiles appear to equate to a higher risk of adverse outcomes.

Finally, our attention to lipid profiles should extend beyond birth, since the long-term risk of cardiovascular disease may be influenced by preeclampsia and potentially by the lipid changes that escalate with the condition.

Dr. Wiznitzer reported having no financial disclosures related to this Master Class.

Best lipid levels in pregnancy still unclear

As ob.gyns., we often focus on optimizing our patients’ reproductive health. Research has shown, however, that the condition of a woman’s health prior to conception can be just as – if not more – important to her pregnancy and her lifelong well-being. For example, we have established that women who take the daily recommended dose of folic acid (400 mcg), even outside of pregnancy, have a reduced risk for neural tube defects in their infants.

Last year, we devoted a series of Master Class columns to the crucial need to properly manage maternal weight gain and blood sugar levels before, during, and after gestation to improve pregnancy outcomes. We also have seen that intensive glycemic and weight control in women can reduce their risk of fetal and maternal complications.

However, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality remain cardiovascular diseases, both in the developing and developed world. One of the key contributors to poor heart and vascular health is high cholesterol. Although the body needs cholesterol, just as it needs sugar, excess lipids in the blood can lead to infarction and stroke.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the desirable total cholesterol levels, including low- and high-density lipids and triglycerides, for men and nonpregnant women fall below 200 mg/dL. What remain less clear are the desired lipid levels for pregnant women.

We have known for decades that cholesterol concentrations increase during pregnancy, possibly by as much as 50%. We do not, however, have a firm understanding of what may constitute normally higher lipid concentrations and what may signal risk to the health of the baby or mother. Additionally, while we may run a lipid panel when we order a blood test, ob.gyns. do not routinely monitor a women’s cholesterol.

Since excess lipids, obesity, and heart disease often occur in the same patient and have become increasingly prevalent in our society, it may be time to reexamine any correlations between maternal lipid levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

To comment on this reemerging area, we invited Dr. Arnon Wiznitzer, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women and deputy director of the Rabin Medical Center, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University. Dr. Wiznitzer’s extensive experience working with women who have diabetes in pregnancy led him to examine other comorbidities, including lipids, which might confound good pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

As ob.gyns., we often focus on optimizing our patients’ reproductive health. Research has shown, however, that the condition of a woman’s health prior to conception can be just as – if not more – important to her pregnancy and her lifelong well-being. For example, we have established that women who take the daily recommended dose of folic acid (400 mcg), even outside of pregnancy, have a reduced risk for neural tube defects in their infants.

Last year, we devoted a series of Master Class columns to the crucial need to properly manage maternal weight gain and blood sugar levels before, during, and after gestation to improve pregnancy outcomes. We also have seen that intensive glycemic and weight control in women can reduce their risk of fetal and maternal complications.

However, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality remain cardiovascular diseases, both in the developing and developed world. One of the key contributors to poor heart and vascular health is high cholesterol. Although the body needs cholesterol, just as it needs sugar, excess lipids in the blood can lead to infarction and stroke.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the desirable total cholesterol levels, including low- and high-density lipids and triglycerides, for men and nonpregnant women fall below 200 mg/dL. What remain less clear are the desired lipid levels for pregnant women.

We have known for decades that cholesterol concentrations increase during pregnancy, possibly by as much as 50%. We do not, however, have a firm understanding of what may constitute normally higher lipid concentrations and what may signal risk to the health of the baby or mother. Additionally, while we may run a lipid panel when we order a blood test, ob.gyns. do not routinely monitor a women’s cholesterol.

Since excess lipids, obesity, and heart disease often occur in the same patient and have become increasingly prevalent in our society, it may be time to reexamine any correlations between maternal lipid levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

To comment on this reemerging area, we invited Dr. Arnon Wiznitzer, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women and deputy director of the Rabin Medical Center, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University. Dr. Wiznitzer’s extensive experience working with women who have diabetes in pregnancy led him to examine other comorbidities, including lipids, which might confound good pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

As ob.gyns., we often focus on optimizing our patients’ reproductive health. Research has shown, however, that the condition of a woman’s health prior to conception can be just as – if not more – important to her pregnancy and her lifelong well-being. For example, we have established that women who take the daily recommended dose of folic acid (400 mcg), even outside of pregnancy, have a reduced risk for neural tube defects in their infants.

Last year, we devoted a series of Master Class columns to the crucial need to properly manage maternal weight gain and blood sugar levels before, during, and after gestation to improve pregnancy outcomes. We also have seen that intensive glycemic and weight control in women can reduce their risk of fetal and maternal complications.

However, the leading causes of morbidity and mortality remain cardiovascular diseases, both in the developing and developed world. One of the key contributors to poor heart and vascular health is high cholesterol. Although the body needs cholesterol, just as it needs sugar, excess lipids in the blood can lead to infarction and stroke.

According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the desirable total cholesterol levels, including low- and high-density lipids and triglycerides, for men and nonpregnant women fall below 200 mg/dL. What remain less clear are the desired lipid levels for pregnant women.

We have known for decades that cholesterol concentrations increase during pregnancy, possibly by as much as 50%. We do not, however, have a firm understanding of what may constitute normally higher lipid concentrations and what may signal risk to the health of the baby or mother. Additionally, while we may run a lipid panel when we order a blood test, ob.gyns. do not routinely monitor a women’s cholesterol.

Since excess lipids, obesity, and heart disease often occur in the same patient and have become increasingly prevalent in our society, it may be time to reexamine any correlations between maternal lipid levels and adverse pregnancy outcomes.

To comment on this reemerging area, we invited Dr. Arnon Wiznitzer, professor and chairman of the department of obstetrics and gynecology at Helen Schneider Hospital for Women and deputy director of the Rabin Medical Center, Sackler Faculty of Medicine, Tel Aviv University. Dr. Wiznitzer’s extensive experience working with women who have diabetes in pregnancy led him to examine other comorbidities, including lipids, which might confound good pregnancy outcomes.

Dr. Reece, who specializes in maternal-fetal medicine, is vice president for medical affairs at the University of Maryland, Baltimore, as well as the John Z. and Akiko K. Bowers Distinguished Professor and dean of the school of medicine. Dr. Reece said he had no relevant financial disclosures. He is the medical editor of this column. Contact him at [email protected].

Jury still out on combo for elderly AML

Photo courtesy of NIH

VIENNA—A 2-drug combination can produce complete responses (CRs) in elderly patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but whether the treatment confers a survival benefit remains to be seen.

The combination consists of the HDAC inhibitor pracinostat and the antineoplastic agent azacitidine.

In a phase 2 study, the treatment produced CRs in nearly a third of AML patients, and follow-up has shown that responses improve over time.

However, the median overall survival has not been reached.

“The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine continues to demonstrate compelling clinical activity in these elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML,” said Daniel P. Gold, PhD, President and Chief Executive Officer of MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

“While the overall survival trend in this study is encouraging, we believe that longer follow-up is needed to gain an accurate survival estimate. Ultimately, this survival estimate will be critical in determining the development path forward for this combination. We look forward to providing an update when these data mature, which we expect to occur later this year.”

The current data were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract P568*). The trial was sponsored by MEI Pharma.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML. Fifty-four percent of patients had intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 42% had high-risk, and 4% were not evaluable.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

To date, half of patients have discontinued treatment, 8% due to death, 36% because of progressive disease, 32% due to adverse events, and 24% for other reasons.

Response and survival

Thus far, 54% of patients (n=27) have achieved the primary endpoint of CR plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Thirty-two percent of patients had a CR, 14% had a CRi, 8% achieved MLFS, and 6% had a partial response (PR) or PR with incomplete count recovery (PRi).

Among the 27 patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 63% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and 7% had a PR/PRi. Among the 21 patients with high-risk cytogenetics, 48% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and none had a PR/PRi.

The researchers said these response rates compare favorably with previous studies of azacitidine alone in this patient population. In this trial, most responses occurred within the first 2 cycles of therapy and continued to improve with ongoing therapy.

The median overall survival has not yet been reached. Sixty-four percent of patients (n=32) are still being followed (range, 6-15 months).

The survival rate of patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics appears greater than that for patients with high-risk cytogenetics, though neither subset of patients has reached median survival.

The 60-day mortality rate was 10% (n=5).

Safety and tolerability

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were nausea (66%), constipation (58%), fatigue (48%), febrile neutropenia (40%), thrombocytopenia (32%), diarrhea (30%), vomiting (28%), decreased appetite (28%), anemia (26%), hypokalemia (26%), neutropenia (24%), pyrexia (24%), dizziness (24%), dyspnea (24%), and rash (20%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 8 patients. Two of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other events included grade 3 peripheral motor neuropathy (which was resolved), grade 3 parainfluenza (resolved with sequelae), grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation (resolved), grade 2 failure to thrive (not resolved), grade 3 mucositis (not resolved), and grade 2 fatigue (not resolved).

AEs resulting in dose reductions were frequently due to disease, according to the researchers.

The team also noted that nearly half of the patients in this study (n=22) have received pracinostat and azacitidine beyond 6 months, and 5 patients have received it for more than a year, which reflects long-term tolerability. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of NIH

VIENNA—A 2-drug combination can produce complete responses (CRs) in elderly patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but whether the treatment confers a survival benefit remains to be seen.

The combination consists of the HDAC inhibitor pracinostat and the antineoplastic agent azacitidine.

In a phase 2 study, the treatment produced CRs in nearly a third of AML patients, and follow-up has shown that responses improve over time.

However, the median overall survival has not been reached.

“The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine continues to demonstrate compelling clinical activity in these elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML,” said Daniel P. Gold, PhD, President and Chief Executive Officer of MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

“While the overall survival trend in this study is encouraging, we believe that longer follow-up is needed to gain an accurate survival estimate. Ultimately, this survival estimate will be critical in determining the development path forward for this combination. We look forward to providing an update when these data mature, which we expect to occur later this year.”

The current data were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract P568*). The trial was sponsored by MEI Pharma.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML. Fifty-four percent of patients had intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 42% had high-risk, and 4% were not evaluable.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

To date, half of patients have discontinued treatment, 8% due to death, 36% because of progressive disease, 32% due to adverse events, and 24% for other reasons.

Response and survival

Thus far, 54% of patients (n=27) have achieved the primary endpoint of CR plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Thirty-two percent of patients had a CR, 14% had a CRi, 8% achieved MLFS, and 6% had a partial response (PR) or PR with incomplete count recovery (PRi).

Among the 27 patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 63% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and 7% had a PR/PRi. Among the 21 patients with high-risk cytogenetics, 48% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and none had a PR/PRi.

The researchers said these response rates compare favorably with previous studies of azacitidine alone in this patient population. In this trial, most responses occurred within the first 2 cycles of therapy and continued to improve with ongoing therapy.

The median overall survival has not yet been reached. Sixty-four percent of patients (n=32) are still being followed (range, 6-15 months).

The survival rate of patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics appears greater than that for patients with high-risk cytogenetics, though neither subset of patients has reached median survival.

The 60-day mortality rate was 10% (n=5).

Safety and tolerability

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were nausea (66%), constipation (58%), fatigue (48%), febrile neutropenia (40%), thrombocytopenia (32%), diarrhea (30%), vomiting (28%), decreased appetite (28%), anemia (26%), hypokalemia (26%), neutropenia (24%), pyrexia (24%), dizziness (24%), dyspnea (24%), and rash (20%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 8 patients. Two of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other events included grade 3 peripheral motor neuropathy (which was resolved), grade 3 parainfluenza (resolved with sequelae), grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation (resolved), grade 2 failure to thrive (not resolved), grade 3 mucositis (not resolved), and grade 2 fatigue (not resolved).

AEs resulting in dose reductions were frequently due to disease, according to the researchers.

The team also noted that nearly half of the patients in this study (n=22) have received pracinostat and azacitidine beyond 6 months, and 5 patients have received it for more than a year, which reflects long-term tolerability. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Photo courtesy of NIH

VIENNA—A 2-drug combination can produce complete responses (CRs) in elderly patients with newly diagnosed acute myeloid leukemia (AML), but whether the treatment confers a survival benefit remains to be seen.

The combination consists of the HDAC inhibitor pracinostat and the antineoplastic agent azacitidine.

In a phase 2 study, the treatment produced CRs in nearly a third of AML patients, and follow-up has shown that responses improve over time.

However, the median overall survival has not been reached.

“The combination of pracinostat and azacitidine continues to demonstrate compelling clinical activity in these elderly patients with newly diagnosed AML,” said Daniel P. Gold, PhD, President and Chief Executive Officer of MEI Pharma, the company developing pracinostat.

“While the overall survival trend in this study is encouraging, we believe that longer follow-up is needed to gain an accurate survival estimate. Ultimately, this survival estimate will be critical in determining the development path forward for this combination. We look forward to providing an update when these data mature, which we expect to occur later this year.”

The current data were presented at the 20th Congress of the European Hematology Association (abstract P568*). The trial was sponsored by MEI Pharma.

The study included 50 patients who had a median age of 75 (range, 66-84). Sixty-six percent of patients had de novo AML, and 34% had secondary AML. Fifty-four percent of patients had intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 42% had high-risk, and 4% were not evaluable.

The patients received pracinostat at 60 mg orally on days 1, 3, and 5 of each week for 21 days of each 28-day cycle. They received azacitidine subcutaneously or intravenously on days 1-7 or days 1-5 and 8-9 (per site preference) of each 28-day cycle.

To date, half of patients have discontinued treatment, 8% due to death, 36% because of progressive disease, 32% due to adverse events, and 24% for other reasons.

Response and survival

Thus far, 54% of patients (n=27) have achieved the primary endpoint of CR plus CR with incomplete count recovery (CRi) plus morphologic leukemia-free state (MLFS).

Thirty-two percent of patients had a CR, 14% had a CRi, 8% achieved MLFS, and 6% had a partial response (PR) or PR with incomplete count recovery (PRi).

Among the 27 patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics, 63% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and 7% had a PR/PRi. Among the 21 patients with high-risk cytogenetics, 48% achieved a CR/CRi/MLFS, and none had a PR/PRi.

The researchers said these response rates compare favorably with previous studies of azacitidine alone in this patient population. In this trial, most responses occurred within the first 2 cycles of therapy and continued to improve with ongoing therapy.

The median overall survival has not yet been reached. Sixty-four percent of patients (n=32) are still being followed (range, 6-15 months).

The survival rate of patients with intermediate-risk cytogenetics appears greater than that for patients with high-risk cytogenetics, though neither subset of patients has reached median survival.

The 60-day mortality rate was 10% (n=5).

Safety and tolerability

The most common treatment-emergent adverse events (AEs) were nausea (66%), constipation (58%), fatigue (48%), febrile neutropenia (40%), thrombocytopenia (32%), diarrhea (30%), vomiting (28%), decreased appetite (28%), anemia (26%), hypokalemia (26%), neutropenia (24%), pyrexia (24%), dizziness (24%), dyspnea (24%), and rash (20%).

Treatment-emergent AEs led to discontinuation in 8 patients. Two of these patients developed sepsis that proved fatal.

The other events included grade 3 peripheral motor neuropathy (which was resolved), grade 3 parainfluenza (resolved with sequelae), grade 3 prolonged QTc/atrial fibrillation (resolved), grade 2 failure to thrive (not resolved), grade 3 mucositis (not resolved), and grade 2 fatigue (not resolved).

AEs resulting in dose reductions were frequently due to disease, according to the researchers.

The team also noted that nearly half of the patients in this study (n=22) have received pracinostat and azacitidine beyond 6 months, and 5 patients have received it for more than a year, which reflects long-term tolerability. ![]()

*Information in the abstract differs from that presented at the meeting.

Letter to the Editor

I thank Locke et al. for their article published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.[1] It summarized well the challenges created by the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program. It is encouraging that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have proposed a different payment method to address the contingency‐fee payment controversy. The new method would require the RACs to be paid after a provider's challenge has passed a second level of a 5‐level appeals process.[2] This, however, has been protested by 1 of the RACs, and a federal appeals court has agreed with the protest.[3] Furthermore, the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) is receiving more requests for hearings than the administrative law judges can adjudicate in a timely manner. OMHA is currently projecting a 20‐ to 24‐week delay in entering new requests into their case processing system. The average processing time for appeals decided in fiscal year 2015 was 547.1 days.[4] Financial impacts of the status issue have thus far only affected hospitals and patients, whereas physician reimbursement has been sheltered. This may change if the RACs request to utilize the CMS manual changes announced in Transmittal 541,[5] which allows certain auditors to deny or recoup payment for procedures performed as inpatients that were not medically necessary. Hospitals have increased the cohorts of observation patients on a single unit or implemented different discharge planning processes for inpatients versus observation. However, patient quality outcomes are not available yet on these approaches.

I thank Locke et al. for their article published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.[1] It summarized well the challenges created by the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program. It is encouraging that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have proposed a different payment method to address the contingency‐fee payment controversy. The new method would require the RACs to be paid after a provider's challenge has passed a second level of a 5‐level appeals process.[2] This, however, has been protested by 1 of the RACs, and a federal appeals court has agreed with the protest.[3] Furthermore, the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) is receiving more requests for hearings than the administrative law judges can adjudicate in a timely manner. OMHA is currently projecting a 20‐ to 24‐week delay in entering new requests into their case processing system. The average processing time for appeals decided in fiscal year 2015 was 547.1 days.[4] Financial impacts of the status issue have thus far only affected hospitals and patients, whereas physician reimbursement has been sheltered. This may change if the RACs request to utilize the CMS manual changes announced in Transmittal 541,[5] which allows certain auditors to deny or recoup payment for procedures performed as inpatients that were not medically necessary. Hospitals have increased the cohorts of observation patients on a single unit or implemented different discharge planning processes for inpatients versus observation. However, patient quality outcomes are not available yet on these approaches.

I thank Locke et al. for their article published in the Journal of Hospital Medicine.[1] It summarized well the challenges created by the Recovery Audit Contractor (RAC) program. It is encouraging that the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) have proposed a different payment method to address the contingency‐fee payment controversy. The new method would require the RACs to be paid after a provider's challenge has passed a second level of a 5‐level appeals process.[2] This, however, has been protested by 1 of the RACs, and a federal appeals court has agreed with the protest.[3] Furthermore, the Office of Medicare Hearings and Appeals (OMHA) is receiving more requests for hearings than the administrative law judges can adjudicate in a timely manner. OMHA is currently projecting a 20‐ to 24‐week delay in entering new requests into their case processing system. The average processing time for appeals decided in fiscal year 2015 was 547.1 days.[4] Financial impacts of the status issue have thus far only affected hospitals and patients, whereas physician reimbursement has been sheltered. This may change if the RACs request to utilize the CMS manual changes announced in Transmittal 541,[5] which allows certain auditors to deny or recoup payment for procedures performed as inpatients that were not medically necessary. Hospitals have increased the cohorts of observation patients on a single unit or implemented different discharge planning processes for inpatients versus observation. However, patient quality outcomes are not available yet on these approaches.

Is there such a thing as good TV?

I was 7 years old when my family got its first television. I can’t recall the year, but I know that we were one of the last houses in our neighborhood to have a color TV. As parents, my wife and I kept our children on a moderate viewing diet, mostly “Captain Kangaroo” and “Sesame Street” when they were young. Until they were teenagers, they believed that only televisions in motel rooms received cartoons. Now, as parents, they are more restrictive with their children than we were with them. One family doesn’t even own a television.

A few years ago, my wife and I cut back our cable service to “basic” and, other than a few sporting events and a rare show on PBS, our TV sits unused in our living room. Five months out of the year, we have no television at all – when we’re in our cottage by the ocean.

Our trajectory from being enthusiastic viewers to television abstainers seems to be not that unusual among our peers. At dinner parties, I often hear, “There is nothing worth watching on television. It’s all junk and commercials.” Could the same condemnation be voiced about television for young children? Could there be some benefit for preschoolers in watching an “educational” show such as “Sesame Street”? Or is it all garbage, even for the very young?

A recently and much ballyhooed study by two economists suggests that, at least as “Sesame Street” is concerned, television can have a positive effect on young children. You may have read the headline: “Study: Kids can learn as much from ‘Sesame Street’ as from preschool” (Washington Post, June 7, 2015).

The researchers exploited a quirk of the precable landscape when some markets could not tune into some shows, including “Sesame Street,” because they were receiving only a UHF signal. Analyzing the data over several years, the economists found that, in communities where children had the opportunity to watch “Sesame Street,” those children had a “14% drop in the likelihood of being behind in school.” That association appeared to fade by the time the children reached high school. To claim that “Sesame Street” is at least as good as preschool based on these numbers seems to me to be a bit of a stretch. It may be that UHF-watching kids watched more professional wrestling, and this encouraged them to be more disruptive in school.

We must remember that these researchers are economists, and we should take anything they conclude with a grain of salt. But let’s say that there may be something to their conclusion that there is an association between “Sesame Street” viewing and school readiness. Does this mean that we should be developing more shows on the “Sesame Street” model, and that young children should be watching educational television several hours a day? Is there a dose effect? Or does this apparent association simply suggest that we should be improving preschools?

For decades, pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics were focused on content and giving too little attention to the amount of screen time. This has improved slightly in the last few years, but the fact remains that television is a passive and sedentary activity that is threatening the health of our nation. It is robbing millions of Americans of precious hours of restorative sleep. It is giving even more millions an easy and addictive way to avoid doing something else. Instead, the addicts spend hours each day watching other people doing something. I always have suspected that the introduction of color to television is the culprit. Black-and-white TV was interesting to a point, but I don’t recall it being addictive. Most of us will watch for hours anything that is colorful and moves.

“Sesame Street” is and has been a wonderful show, and I suspect it has helped millions of children learn things they may not have been exposed to at home. But in one sense, educational programming could be considered a gateway drug. Once the set goes on, many parents don’t have the fortitude to shut it off. We should think twice before claiming that it is on a par with preschool.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.”

I was 7 years old when my family got its first television. I can’t recall the year, but I know that we were one of the last houses in our neighborhood to have a color TV. As parents, my wife and I kept our children on a moderate viewing diet, mostly “Captain Kangaroo” and “Sesame Street” when they were young. Until they were teenagers, they believed that only televisions in motel rooms received cartoons. Now, as parents, they are more restrictive with their children than we were with them. One family doesn’t even own a television.

A few years ago, my wife and I cut back our cable service to “basic” and, other than a few sporting events and a rare show on PBS, our TV sits unused in our living room. Five months out of the year, we have no television at all – when we’re in our cottage by the ocean.

Our trajectory from being enthusiastic viewers to television abstainers seems to be not that unusual among our peers. At dinner parties, I often hear, “There is nothing worth watching on television. It’s all junk and commercials.” Could the same condemnation be voiced about television for young children? Could there be some benefit for preschoolers in watching an “educational” show such as “Sesame Street”? Or is it all garbage, even for the very young?

A recently and much ballyhooed study by two economists suggests that, at least as “Sesame Street” is concerned, television can have a positive effect on young children. You may have read the headline: “Study: Kids can learn as much from ‘Sesame Street’ as from preschool” (Washington Post, June 7, 2015).

The researchers exploited a quirk of the precable landscape when some markets could not tune into some shows, including “Sesame Street,” because they were receiving only a UHF signal. Analyzing the data over several years, the economists found that, in communities where children had the opportunity to watch “Sesame Street,” those children had a “14% drop in the likelihood of being behind in school.” That association appeared to fade by the time the children reached high school. To claim that “Sesame Street” is at least as good as preschool based on these numbers seems to me to be a bit of a stretch. It may be that UHF-watching kids watched more professional wrestling, and this encouraged them to be more disruptive in school.

We must remember that these researchers are economists, and we should take anything they conclude with a grain of salt. But let’s say that there may be something to their conclusion that there is an association between “Sesame Street” viewing and school readiness. Does this mean that we should be developing more shows on the “Sesame Street” model, and that young children should be watching educational television several hours a day? Is there a dose effect? Or does this apparent association simply suggest that we should be improving preschools?

For decades, pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics were focused on content and giving too little attention to the amount of screen time. This has improved slightly in the last few years, but the fact remains that television is a passive and sedentary activity that is threatening the health of our nation. It is robbing millions of Americans of precious hours of restorative sleep. It is giving even more millions an easy and addictive way to avoid doing something else. Instead, the addicts spend hours each day watching other people doing something. I always have suspected that the introduction of color to television is the culprit. Black-and-white TV was interesting to a point, but I don’t recall it being addictive. Most of us will watch for hours anything that is colorful and moves.

“Sesame Street” is and has been a wonderful show, and I suspect it has helped millions of children learn things they may not have been exposed to at home. But in one sense, educational programming could be considered a gateway drug. Once the set goes on, many parents don’t have the fortitude to shut it off. We should think twice before claiming that it is on a par with preschool.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.”

I was 7 years old when my family got its first television. I can’t recall the year, but I know that we were one of the last houses in our neighborhood to have a color TV. As parents, my wife and I kept our children on a moderate viewing diet, mostly “Captain Kangaroo” and “Sesame Street” when they were young. Until they were teenagers, they believed that only televisions in motel rooms received cartoons. Now, as parents, they are more restrictive with their children than we were with them. One family doesn’t even own a television.

A few years ago, my wife and I cut back our cable service to “basic” and, other than a few sporting events and a rare show on PBS, our TV sits unused in our living room. Five months out of the year, we have no television at all – when we’re in our cottage by the ocean.

Our trajectory from being enthusiastic viewers to television abstainers seems to be not that unusual among our peers. At dinner parties, I often hear, “There is nothing worth watching on television. It’s all junk and commercials.” Could the same condemnation be voiced about television for young children? Could there be some benefit for preschoolers in watching an “educational” show such as “Sesame Street”? Or is it all garbage, even for the very young?

A recently and much ballyhooed study by two economists suggests that, at least as “Sesame Street” is concerned, television can have a positive effect on young children. You may have read the headline: “Study: Kids can learn as much from ‘Sesame Street’ as from preschool” (Washington Post, June 7, 2015).

The researchers exploited a quirk of the precable landscape when some markets could not tune into some shows, including “Sesame Street,” because they were receiving only a UHF signal. Analyzing the data over several years, the economists found that, in communities where children had the opportunity to watch “Sesame Street,” those children had a “14% drop in the likelihood of being behind in school.” That association appeared to fade by the time the children reached high school. To claim that “Sesame Street” is at least as good as preschool based on these numbers seems to me to be a bit of a stretch. It may be that UHF-watching kids watched more professional wrestling, and this encouraged them to be more disruptive in school.

We must remember that these researchers are economists, and we should take anything they conclude with a grain of salt. But let’s say that there may be something to their conclusion that there is an association between “Sesame Street” viewing and school readiness. Does this mean that we should be developing more shows on the “Sesame Street” model, and that young children should be watching educational television several hours a day? Is there a dose effect? Or does this apparent association simply suggest that we should be improving preschools?

For decades, pediatricians and the American Academy of Pediatrics were focused on content and giving too little attention to the amount of screen time. This has improved slightly in the last few years, but the fact remains that television is a passive and sedentary activity that is threatening the health of our nation. It is robbing millions of Americans of precious hours of restorative sleep. It is giving even more millions an easy and addictive way to avoid doing something else. Instead, the addicts spend hours each day watching other people doing something. I always have suspected that the introduction of color to television is the culprit. Black-and-white TV was interesting to a point, but I don’t recall it being addictive. Most of us will watch for hours anything that is colorful and moves.

“Sesame Street” is and has been a wonderful show, and I suspect it has helped millions of children learn things they may not have been exposed to at home. But in one sense, educational programming could be considered a gateway drug. Once the set goes on, many parents don’t have the fortitude to shut it off. We should think twice before claiming that it is on a par with preschool.

Dr. Wilkoff practiced primary care pediatrics in Brunswick, Maine, for nearly 40 years. He has authored several books on behavioral pediatrics, including “Coping with a Picky Eater.”

ICD-10 Race to the Finish: 8 High Priorities in the 11th Hour

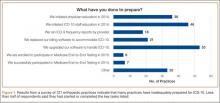

As late as mid-April 2015, a survey of 121 orthopedic practices indicated that 30% had done nothing to start preparing for ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision).1 That’s scary. And even the practices that had begun to prepare had not completed a number of key tasks (Figure 1).

Certainly, the will-they-or-won’t-they possibility of another congressional delay had many practices sitting on their hands this year. But now that the October 1, 2015, implementation is set in stone, this lack of inertia has many practices woefully behind. If your practice is one of many that hasn’t mapped your common ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) codes to ICD-10 codes, completed payer testing, or attended training, it’s time for a “full-court press.”

Being unprepared for ICD-10 will cause more than just an increase in claim denials. If your surgery schedule is booked a few months out, your staff will need to pre-authorize cases using ICD-10 as early as August 1—and they won’t be able to do that if you haven’t dictated the clinical terms required to choose an ICD-10 code. Without an understanding of ICD-10, severity of illness coding will suffer, and that will affect your bundled and value-based payments. And, if you don’t provide an adequate diagnosis when sending patients off-site for physical therapy, you’ll soon be getting phone calls from their billing staff demanding more specifics.

The clock is ticking and time is short. Here’s a prioritized list of what needs to get done.

1. Generate an ICD-9 frequency report

Identifying which diagnosis codes are the most frequently used, and therefore drive a significant portion of practice revenue, is an absolute must. The data will help prioritize training and code-mapping activities.

Most practices generate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code-frequency reports regularly, but few have ever run an ICD-9 code-frequency report. Call your vendor and ask for assistance, as there are multiple ways to run this report and they vary by practice management system. Sort the data elements and generate the ICD-9 frequency report by:

- Primary diagnosis.

- Unique patient.

- Revenue. (If your practice management system can’t give you diagnosis data by revenue, which enables you to focus on the codes that generate the most revenue, generate it by charges.)

The result should be a report that identifies the 20 to 25 diagnosis codes (or charges, depending on the reports generated) that drive the most revenue for the practice. Use the data to focus and prioritize your training and code-mapping activities.

2. Schedule training

Forget about “general” ICD-10 training courses. You need orthopedic-specific guidance. That’s because ICD-10 for orthopedics is more complex than for other specialties. Dictating fractures under ICD-10 is not so simple. Selecting an injury code requires confidence in correctly using the seventh character.

“Everyone who uses diagnosis codes must have baseline knowledge: surgeons, billing staff, surgical coordinators, and clinical team,” according to Sarah Wiskerchen, MBA, CPC, consultant and ICD-10 educator with KarenZupko & Associates (KZA). Training must include the practical details of ICD-10, such as assigning laterality, understanding the system architecture, and limiting the use of unspecified codes.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) offers a self-paced, online training series that provides details for the top 3 diagnosis codes for each subspecialty. The 10-program course, ICD-10-CM: By the Numbers, is available at www.aaos.org ($299 for members, $399 for nonmembers). If you prefer live instruction, there is one more AAOS-sponsored, regional ICD-10 workshop left before the October 1 deadline, and more may be added. (Details at www.karenzupko.com)

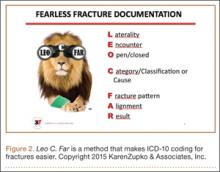

These courses provide highly specific and granular ICD-10 knowledge and incorporate the use of Code-X, an AAOS-developed software tool. They also feature tools for handling the complexities of fractures and injury codes, such as Leo C. Far, an acronym developed by KZA consultant and coding educator Margie Maley, BSN, MS, to make ICD-10 diagnosis coding for fractures easier (Figure 2).

Some subspecialty societies also offer ICD-10 training. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand (www.assh.org), for example, offers a series of webinars and member-developed ICD-9-to-ICD-10 code maps.

3. Crosswalk your common codes from ICD-9 to ICD-10

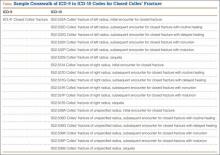

Crosswalking is the process of mapping your most commonly used ICD-9 codes to their equivalent ICD-10 codes. This exercise familiarizes your team with ICD-10 language and terms, and gives a sense of which ICD-9 codes expand to just 1 or 2 ICD-10 codes and which codes expand into 10 or more codes—as some injury codes do (Table).

“Attempting to map the codes before completing ICD-10 training is like trying to write a letter in Greek when you only speak English,” Wiskerchen warns. “So start this process after at least some of your team have grasped the fundamentals of ICD-10.” This is where the data from your ICD-9 frequency report comes in. Use it to prioritize which codes to map first with a goal of mapping your top 25 ICD-9 codes to their ICD-10 equivalents by August 31.

Invest in good tools to support your mapping efforts. Avoid general mapping equivalent (GEM) coding tools, which are free for a good reason—they are incomplete and don’t always lead you to the correct ICD-10 code. Instead, purchase resources from credible sources, such as the American Medical Association (AMA; www.ama-assn.org). The AMA publishes ICD-10-CM 2016: The Complete Official Codebook as well as ICD-10-CM Mappings 2016, which links ICD-9 codes to all valid ICD-10 alternatives. The AMA also offers electronic ICD-10-CM Express Reference Mapping Cards for multiple specialties.

Practice makes perfect and crosswalking from ICD-9 to ICD-10 is one of the best ways for your team to become aware of the nuances in the new coding system. Like learning a new language, “speaking” ICD-10 does not become automatic just because you’ve attended training or completed the coding maps. Training teaches the architecture of the new coding system. Mapping provides a structured way to become familiar with the codes the practice will use most often. Once these 2 primary pieces are understood and assimilated, most physicians find that dictating the necessary new terms becomes quite easy.

4. Conduct a gap analysis to identify the ICD-10 terms missing from each provider’s current documentation

Conduct the gap analysis after your team has completed training, and once you’ve at least begun the process of mapping codes from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Here’s how:

- Generate a CPT frequency report.

- Select the top 5 procedures for each physician.

- Pull 2 patients’ notes for each of the top procedures.

- Review the notes and try to select ICD-10 code(s).

If key ICD-10 terms are not included in current documentation, physicians should modify the templates or macros they rely on for dictation.

“This simple exercise makes it obvious which clinical information physicians must add for ICD-10,” Wiskerchen says. For example, if the patient had an arthroscopy, but the note doesn’t specify on which leg, that’s a clear indication that the physician must dictate laterality. “The gap analysis is a great way to coach physicians about the clinical details to document, so staff can bill under ICD-10,” Wiskerchen says.

5. Contact technology vendors

Given the number of new ICD-10 codes in orthopedics, paper cheat sheets will be obsolete. Instead, you’ll need to rely on pull-down menus and/or search fields in the electronic health record (EHR) and practice management systems.

“Get clarity about how the new features and workflow processes will work in your systems,” suggests Wiskerchen. “Ask questions such as: Which features will be added or changed to accommodate the new codes? Will there be new screens or pick lists for ICD-10, or search fields? How will new screens and features change our current workflow? And schedule any necessary training as soon as possible.”

In addition to software upgrades and training, vendors and clearinghouses offer an array of services to help practices make the transition. Some vendors even provide help coordinating your internal plan with their new product features and training. Contact vendors to find out what they offer.

6. Use completed code maps to build diagnosis code databases, EHR templates, charge tickets, pick lists, prompters, and other coding tools

“Provide the code crosswalks and results of your documentation gap analysis to the IT [information technology] team so they can get started,” Wiskerchen advises. “And assign a physician or midlevel provider to work with IT so that the tools are clinically accurate.”

7. Schedule testing with clearinghouses and payers

“Successful testing indicates that your hard work has paid off, and that claims will be processed with few, if any, ICD-10–related hiccups,” Wiskerchen says. Essentially, the testing confirms that your ICD-10 code database, pick lists, vendor features, and other coding fields are working properly. “Testing with a clearinghouse is good. Testing directly with the payer is even better, if you are a direct submitter and it is allowed,” Wiskerchen suggests. Contact your clearinghouse and/or payers for testing opportunities prior to October 1.

8. Develop a plan for a potential cash flow crunch

So what happens if your best efforts in the 11th hour still aren’t enough to get your practice to the ICD-10 finish line? Prepare for the possibility of increased claim denials and temporary cash flow stalls, and put a plan in place to deal with them.

Start now by cleaning up as much of the accounts receivable as possible, and moving patient collections up front. Ask the billing team for a weekly status update of the largest unpaid balances in the 60-day aging column, and what has been done to appeal or otherwise address them. Analyze denial patterns and trends and fix their causes at the source—some may be ICD-10–related, others may simply be a gap in the reimbursement process that needs improvement.

Use payer cost estimators to calculate patient out-of-pocket cost and to collect unmet deductibles, coinsurance, and noncovered services prior to surgery. The surgeon-developed iPhone app Health Insurance Arithmetic2 ($1.99 in the iTunes Store) can help staff do this math on one, simple screen.

Finally, secure a line of credit to guard against a claim denial pile up this fall. A line of credit mitigates financial risk by making cash available quickly, should you need it to cover temporary revenue shortfalls, meet payroll, or pay operational expenses. It’s not too late to meet with your banker and apply for this protection, and the peace of mind may even help you sleep better.

1. KarenZupko & Associates, Inc. Pre-course survey of Q1 2015 coding and reimbursement workshop attendees. [Workshops are cosponsored by the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.] Unpublished data, April 2015.

2. Health Insurance Arithmetic. iTunes Store website. https://itunes.apple.com/us/app/healthinsurancearithmetic/id953262818. Accessed May 12, 2015.

As late as mid-April 2015, a survey of 121 orthopedic practices indicated that 30% had done nothing to start preparing for ICD-10 (International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision).1 That’s scary. And even the practices that had begun to prepare had not completed a number of key tasks (Figure 1).

Certainly, the will-they-or-won’t-they possibility of another congressional delay had many practices sitting on their hands this year. But now that the October 1, 2015, implementation is set in stone, this lack of inertia has many practices woefully behind. If your practice is one of many that hasn’t mapped your common ICD-9 (International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision) codes to ICD-10 codes, completed payer testing, or attended training, it’s time for a “full-court press.”

Being unprepared for ICD-10 will cause more than just an increase in claim denials. If your surgery schedule is booked a few months out, your staff will need to pre-authorize cases using ICD-10 as early as August 1—and they won’t be able to do that if you haven’t dictated the clinical terms required to choose an ICD-10 code. Without an understanding of ICD-10, severity of illness coding will suffer, and that will affect your bundled and value-based payments. And, if you don’t provide an adequate diagnosis when sending patients off-site for physical therapy, you’ll soon be getting phone calls from their billing staff demanding more specifics.

The clock is ticking and time is short. Here’s a prioritized list of what needs to get done.

1. Generate an ICD-9 frequency report

Identifying which diagnosis codes are the most frequently used, and therefore drive a significant portion of practice revenue, is an absolute must. The data will help prioritize training and code-mapping activities.

Most practices generate Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code-frequency reports regularly, but few have ever run an ICD-9 code-frequency report. Call your vendor and ask for assistance, as there are multiple ways to run this report and they vary by practice management system. Sort the data elements and generate the ICD-9 frequency report by:

- Primary diagnosis.

- Unique patient.

- Revenue. (If your practice management system can’t give you diagnosis data by revenue, which enables you to focus on the codes that generate the most revenue, generate it by charges.)

The result should be a report that identifies the 20 to 25 diagnosis codes (or charges, depending on the reports generated) that drive the most revenue for the practice. Use the data to focus and prioritize your training and code-mapping activities.

2. Schedule training

Forget about “general” ICD-10 training courses. You need orthopedic-specific guidance. That’s because ICD-10 for orthopedics is more complex than for other specialties. Dictating fractures under ICD-10 is not so simple. Selecting an injury code requires confidence in correctly using the seventh character.

“Everyone who uses diagnosis codes must have baseline knowledge: surgeons, billing staff, surgical coordinators, and clinical team,” according to Sarah Wiskerchen, MBA, CPC, consultant and ICD-10 educator with KarenZupko & Associates (KZA). Training must include the practical details of ICD-10, such as assigning laterality, understanding the system architecture, and limiting the use of unspecified codes.

The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS) offers a self-paced, online training series that provides details for the top 3 diagnosis codes for each subspecialty. The 10-program course, ICD-10-CM: By the Numbers, is available at www.aaos.org ($299 for members, $399 for nonmembers). If you prefer live instruction, there is one more AAOS-sponsored, regional ICD-10 workshop left before the October 1 deadline, and more may be added. (Details at www.karenzupko.com)

These courses provide highly specific and granular ICD-10 knowledge and incorporate the use of Code-X, an AAOS-developed software tool. They also feature tools for handling the complexities of fractures and injury codes, such as Leo C. Far, an acronym developed by KZA consultant and coding educator Margie Maley, BSN, MS, to make ICD-10 diagnosis coding for fractures easier (Figure 2).

Some subspecialty societies also offer ICD-10 training. The American Society for Surgery of the Hand (www.assh.org), for example, offers a series of webinars and member-developed ICD-9-to-ICD-10 code maps.

3. Crosswalk your common codes from ICD-9 to ICD-10

Crosswalking is the process of mapping your most commonly used ICD-9 codes to their equivalent ICD-10 codes. This exercise familiarizes your team with ICD-10 language and terms, and gives a sense of which ICD-9 codes expand to just 1 or 2 ICD-10 codes and which codes expand into 10 or more codes—as some injury codes do (Table).

“Attempting to map the codes before completing ICD-10 training is like trying to write a letter in Greek when you only speak English,” Wiskerchen warns. “So start this process after at least some of your team have grasped the fundamentals of ICD-10.” This is where the data from your ICD-9 frequency report comes in. Use it to prioritize which codes to map first with a goal of mapping your top 25 ICD-9 codes to their ICD-10 equivalents by August 31.

Invest in good tools to support your mapping efforts. Avoid general mapping equivalent (GEM) coding tools, which are free for a good reason—they are incomplete and don’t always lead you to the correct ICD-10 code. Instead, purchase resources from credible sources, such as the American Medical Association (AMA; www.ama-assn.org). The AMA publishes ICD-10-CM 2016: The Complete Official Codebook as well as ICD-10-CM Mappings 2016, which links ICD-9 codes to all valid ICD-10 alternatives. The AMA also offers electronic ICD-10-CM Express Reference Mapping Cards for multiple specialties.

Practice makes perfect and crosswalking from ICD-9 to ICD-10 is one of the best ways for your team to become aware of the nuances in the new coding system. Like learning a new language, “speaking” ICD-10 does not become automatic just because you’ve attended training or completed the coding maps. Training teaches the architecture of the new coding system. Mapping provides a structured way to become familiar with the codes the practice will use most often. Once these 2 primary pieces are understood and assimilated, most physicians find that dictating the necessary new terms becomes quite easy.

4. Conduct a gap analysis to identify the ICD-10 terms missing from each provider’s current documentation

Conduct the gap analysis after your team has completed training, and once you’ve at least begun the process of mapping codes from ICD-9 to ICD-10. Here’s how:

- Generate a CPT frequency report.

- Select the top 5 procedures for each physician.

- Pull 2 patients’ notes for each of the top procedures.

- Review the notes and try to select ICD-10 code(s).

If key ICD-10 terms are not included in current documentation, physicians should modify the templates or macros they rely on for dictation.

“This simple exercise makes it obvious which clinical information physicians must add for ICD-10,” Wiskerchen says. For example, if the patient had an arthroscopy, but the note doesn’t specify on which leg, that’s a clear indication that the physician must dictate laterality. “The gap analysis is a great way to coach physicians about the clinical details to document, so staff can bill under ICD-10,” Wiskerchen says.

5. Contact technology vendors

Given the number of new ICD-10 codes in orthopedics, paper cheat sheets will be obsolete. Instead, you’ll need to rely on pull-down menus and/or search fields in the electronic health record (EHR) and practice management systems.

“Get clarity about how the new features and workflow processes will work in your systems,” suggests Wiskerchen. “Ask questions such as: Which features will be added or changed to accommodate the new codes? Will there be new screens or pick lists for ICD-10, or search fields? How will new screens and features change our current workflow? And schedule any necessary training as soon as possible.”

In addition to software upgrades and training, vendors and clearinghouses offer an array of services to help practices make the transition. Some vendors even provide help coordinating your internal plan with their new product features and training. Contact vendors to find out what they offer.

6. Use completed code maps to build diagnosis code databases, EHR templates, charge tickets, pick lists, prompters, and other coding tools

“Provide the code crosswalks and results of your documentation gap analysis to the IT [information technology] team so they can get started,” Wiskerchen advises. “And assign a physician or midlevel provider to work with IT so that the tools are clinically accurate.”

7. Schedule testing with clearinghouses and payers

“Successful testing indicates that your hard work has paid off, and that claims will be processed with few, if any, ICD-10–related hiccups,” Wiskerchen says. Essentially, the testing confirms that your ICD-10 code database, pick lists, vendor features, and other coding fields are working properly. “Testing with a clearinghouse is good. Testing directly with the payer is even better, if you are a direct submitter and it is allowed,” Wiskerchen suggests. Contact your clearinghouse and/or payers for testing opportunities prior to October 1.

8. Develop a plan for a potential cash flow crunch

So what happens if your best efforts in the 11th hour still aren’t enough to get your practice to the ICD-10 finish line? Prepare for the possibility of increased claim denials and temporary cash flow stalls, and put a plan in place to deal with them.

Start now by cleaning up as much of the accounts receivable as possible, and moving patient collections up front. Ask the billing team for a weekly status update of the largest unpaid balances in the 60-day aging column, and what has been done to appeal or otherwise address them. Analyze denial patterns and trends and fix their causes at the source—some may be ICD-10–related, others may simply be a gap in the reimbursement process that needs improvement.

Use payer cost estimators to calculate patient out-of-pocket cost and to collect unmet deductibles, coinsurance, and noncovered services prior to surgery. The surgeon-developed iPhone app Health Insurance Arithmetic2 ($1.99 in the iTunes Store) can help staff do this math on one, simple screen.

Finally, secure a line of credit to guard against a claim denial pile up this fall. A line of credit mitigates financial risk by making cash available quickly, should you need it to cover temporary revenue shortfalls, meet payroll, or pay operational expenses. It’s not too late to meet with your banker and apply for this protection, and the peace of mind may even help you sleep better.