User login

Highlights From the 2015 CMSC Annual Meeting

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

Click here to download the PDF.

NSAIDS May Increase Kidney Risks with High Blood Pressure

(Reuters Health) - Patients with hypertension who regularly take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may increase their risk of developing chronic kidney disease, a study from Taiwan suggests.

The researchers examined data on more than 30,000 people with hypertension and found that those who'd been taking NSAIDs for at least three months were 32% more likely to have chronic kidney disease than participants who didn't use NSAIDs.

In addition, participants who typically took NSAIDs more than once a day had a 23% greater risk of developing chronic kidney disease than people who didn't use the pills.

Even if patients used NSAIDs for less than three months, they still had an 18% higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease, the study found.

"Our results suggest that NSAID duration plays a role in chronic kidney disease among subjects with hypertension," said senior study author Hui-Ju Tsai, a scientist at the Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes in Zhunan.

"Physicians should exercise caution when administering NSAIDs to people with hypertension and closely monitor renal function," Tsai said by email.

One shortcoming of the study is a lack of blood test data to confirm the severity of kidney disease, the authors noted online July 13 in Hypertension. It's also possible that some patients with kidney disease weren't identified due to a lack of clinical or laboratory data.

In addition, the study only tracked prescription NSAID use. In Taiwan, the vast majority of people taking these drugs get prescriptions because the cost is much lower than it would be for over-the-counter versions of the drugs, the authors point out.

While past research has suggested that kidney damage linked to NSAIDs might be reversed if the drugs are stopped, the current study points to the possibility that long-term use of these painkillers might lead to permanently impaired renal function, said Dr. Liffert Vogt, a nephrologist at Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

NSAIDs can cause the kidney to retain salts and water, prompting a rise in blood pressure and potentially making medications to lower hypertension ineffective, Vogt, who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"When a patient is already treated with a blood pressure lowering drug, NSAIDs should be avoided," Vogt said. "The negative effects of NSAIDs on the kidneys can be explained by their effects on blood pressure control."

(Reuters Health) - Patients with hypertension who regularly take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may increase their risk of developing chronic kidney disease, a study from Taiwan suggests.

The researchers examined data on more than 30,000 people with hypertension and found that those who'd been taking NSAIDs for at least three months were 32% more likely to have chronic kidney disease than participants who didn't use NSAIDs.

In addition, participants who typically took NSAIDs more than once a day had a 23% greater risk of developing chronic kidney disease than people who didn't use the pills.

Even if patients used NSAIDs for less than three months, they still had an 18% higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease, the study found.

"Our results suggest that NSAID duration plays a role in chronic kidney disease among subjects with hypertension," said senior study author Hui-Ju Tsai, a scientist at the Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes in Zhunan.

"Physicians should exercise caution when administering NSAIDs to people with hypertension and closely monitor renal function," Tsai said by email.

One shortcoming of the study is a lack of blood test data to confirm the severity of kidney disease, the authors noted online July 13 in Hypertension. It's also possible that some patients with kidney disease weren't identified due to a lack of clinical or laboratory data.

In addition, the study only tracked prescription NSAID use. In Taiwan, the vast majority of people taking these drugs get prescriptions because the cost is much lower than it would be for over-the-counter versions of the drugs, the authors point out.

While past research has suggested that kidney damage linked to NSAIDs might be reversed if the drugs are stopped, the current study points to the possibility that long-term use of these painkillers might lead to permanently impaired renal function, said Dr. Liffert Vogt, a nephrologist at Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

NSAIDs can cause the kidney to retain salts and water, prompting a rise in blood pressure and potentially making medications to lower hypertension ineffective, Vogt, who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"When a patient is already treated with a blood pressure lowering drug, NSAIDs should be avoided," Vogt said. "The negative effects of NSAIDs on the kidneys can be explained by their effects on blood pressure control."

(Reuters Health) - Patients with hypertension who regularly take non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) may increase their risk of developing chronic kidney disease, a study from Taiwan suggests.

The researchers examined data on more than 30,000 people with hypertension and found that those who'd been taking NSAIDs for at least three months were 32% more likely to have chronic kidney disease than participants who didn't use NSAIDs.

In addition, participants who typically took NSAIDs more than once a day had a 23% greater risk of developing chronic kidney disease than people who didn't use the pills.

Even if patients used NSAIDs for less than three months, they still had an 18% higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease, the study found.

"Our results suggest that NSAID duration plays a role in chronic kidney disease among subjects with hypertension," said senior study author Hui-Ju Tsai, a scientist at the Institute of Population Health Sciences, National Health Research Institutes in Zhunan.

"Physicians should exercise caution when administering NSAIDs to people with hypertension and closely monitor renal function," Tsai said by email.

One shortcoming of the study is a lack of blood test data to confirm the severity of kidney disease, the authors noted online July 13 in Hypertension. It's also possible that some patients with kidney disease weren't identified due to a lack of clinical or laboratory data.

In addition, the study only tracked prescription NSAID use. In Taiwan, the vast majority of people taking these drugs get prescriptions because the cost is much lower than it would be for over-the-counter versions of the drugs, the authors point out.

While past research has suggested that kidney damage linked to NSAIDs might be reversed if the drugs are stopped, the current study points to the possibility that long-term use of these painkillers might lead to permanently impaired renal function, said Dr. Liffert Vogt, a nephrologist at Academic Medical Center at the University of Amsterdam in The Netherlands.

NSAIDs can cause the kidney to retain salts and water, prompting a rise in blood pressure and potentially making medications to lower hypertension ineffective, Vogt, who wasn't involved in the study, said by email.

"When a patient is already treated with a blood pressure lowering drug, NSAIDs should be avoided," Vogt said. "The negative effects of NSAIDs on the kidneys can be explained by their effects on blood pressure control."

PHM15: Urinary Tract Infection (UTI) Management in Febrile Infants

Drs. Pate and Engel presented a hot topic in pediatric hospital medicine, sparking fruitful conversation about current evidence, identified gaps, and controversies regarding the management of febrile infants with urinary tract infections. After the American Academy of Pediatrics published the updated clinical guideline in 2011, controversies about radioimaging, duration of treatment, and pursuit of laboratory evaluations arose. These controversies continue today, and value and gold standard tests are now being questioned. Should urine culture truly be the gold standard to define a UTI?

The current evidence (applying to 2 month-2 years) in a nutshell includes:

- Oral and parental antibiotics are equally efficacious,

- Duration of treatment is a wide range of 7-14 days,

- Positive UA indicating inflammation/infection and a culture >50,000 uropathogens/ml is needed to make the diagnosis, and

- Febrile infants with first UTI should get a renal ultrasound; only if the ultrasound is abnormal should patients get a Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG).

Since the guideline was published in 2011, there has been continued disagreement between pediatricians and pediatric urologists. When thinking about high-value care, what value is added by doing the renal ultrasound and/or VCUG? The research over the last couple of years shows that although there is concern that UTIs lead to renal scarring and chronic kidney disease, in the absence of structural kidney abnormalities, recurrent UTIs cause at most 0.3% of chronic kidney disease. The takehome point from the 2014 RIVUR study is:

- The treatment group had significantly higher rates of resistance organisms (63% ppx 19% placebo).

- The NNT with prophylaxis in children with VUR is 9 children for 2 years to prevent 1 UTI, or 6570 days of antibiotics to prevent one 7-14 day course.

The RIVUR study raised more questions:

- Is there a difference in outcome if a child had concurrent bacteremia?

- There is no significant difference in clinical presentation between an isolated UTI and an infant with bacteremia. Those patients with bacteremia received longer duration of parenteral antibiotics, but the number of days were highly variable and outcomes were excellent overall regardless.

- How accurate is UA in the diagnosis of urinary tract infections in infants less than 3 months of age?

- Urinalysis in those infants

- Could inflammatory markers accurately identify infants at high risk for more severe disease?

- Not really.

Guidelines were reviewed, controversies were discussed, and questions were proposed. The session ended with tools to take home to help change hospital practice, and quality-UTI projects metrics were shared, as this is the next AAP VIP project about to launch.

Key Takeaways:

- The guidelines represent a living and dynamic tool that integrates the best evidence we have.

- There is new research evolving and lessons to be learned.

Dr. Hopkins is an academic pediatric hospitalist and instructor at All Children's Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine, St. Petersburg, Fla.

Drs. Pate and Engel presented a hot topic in pediatric hospital medicine, sparking fruitful conversation about current evidence, identified gaps, and controversies regarding the management of febrile infants with urinary tract infections. After the American Academy of Pediatrics published the updated clinical guideline in 2011, controversies about radioimaging, duration of treatment, and pursuit of laboratory evaluations arose. These controversies continue today, and value and gold standard tests are now being questioned. Should urine culture truly be the gold standard to define a UTI?

The current evidence (applying to 2 month-2 years) in a nutshell includes:

- Oral and parental antibiotics are equally efficacious,

- Duration of treatment is a wide range of 7-14 days,

- Positive UA indicating inflammation/infection and a culture >50,000 uropathogens/ml is needed to make the diagnosis, and

- Febrile infants with first UTI should get a renal ultrasound; only if the ultrasound is abnormal should patients get a Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG).

Since the guideline was published in 2011, there has been continued disagreement between pediatricians and pediatric urologists. When thinking about high-value care, what value is added by doing the renal ultrasound and/or VCUG? The research over the last couple of years shows that although there is concern that UTIs lead to renal scarring and chronic kidney disease, in the absence of structural kidney abnormalities, recurrent UTIs cause at most 0.3% of chronic kidney disease. The takehome point from the 2014 RIVUR study is:

- The treatment group had significantly higher rates of resistance organisms (63% ppx 19% placebo).

- The NNT with prophylaxis in children with VUR is 9 children for 2 years to prevent 1 UTI, or 6570 days of antibiotics to prevent one 7-14 day course.

The RIVUR study raised more questions:

- Is there a difference in outcome if a child had concurrent bacteremia?

- There is no significant difference in clinical presentation between an isolated UTI and an infant with bacteremia. Those patients with bacteremia received longer duration of parenteral antibiotics, but the number of days were highly variable and outcomes were excellent overall regardless.

- How accurate is UA in the diagnosis of urinary tract infections in infants less than 3 months of age?

- Urinalysis in those infants

- Could inflammatory markers accurately identify infants at high risk for more severe disease?

- Not really.

Guidelines were reviewed, controversies were discussed, and questions were proposed. The session ended with tools to take home to help change hospital practice, and quality-UTI projects metrics were shared, as this is the next AAP VIP project about to launch.

Key Takeaways:

- The guidelines represent a living and dynamic tool that integrates the best evidence we have.

- There is new research evolving and lessons to be learned.

Dr. Hopkins is an academic pediatric hospitalist and instructor at All Children's Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine, St. Petersburg, Fla.

Drs. Pate and Engel presented a hot topic in pediatric hospital medicine, sparking fruitful conversation about current evidence, identified gaps, and controversies regarding the management of febrile infants with urinary tract infections. After the American Academy of Pediatrics published the updated clinical guideline in 2011, controversies about radioimaging, duration of treatment, and pursuit of laboratory evaluations arose. These controversies continue today, and value and gold standard tests are now being questioned. Should urine culture truly be the gold standard to define a UTI?

The current evidence (applying to 2 month-2 years) in a nutshell includes:

- Oral and parental antibiotics are equally efficacious,

- Duration of treatment is a wide range of 7-14 days,

- Positive UA indicating inflammation/infection and a culture >50,000 uropathogens/ml is needed to make the diagnosis, and

- Febrile infants with first UTI should get a renal ultrasound; only if the ultrasound is abnormal should patients get a Voiding Cystourethrogram (VCUG).

Since the guideline was published in 2011, there has been continued disagreement between pediatricians and pediatric urologists. When thinking about high-value care, what value is added by doing the renal ultrasound and/or VCUG? The research over the last couple of years shows that although there is concern that UTIs lead to renal scarring and chronic kidney disease, in the absence of structural kidney abnormalities, recurrent UTIs cause at most 0.3% of chronic kidney disease. The takehome point from the 2014 RIVUR study is:

- The treatment group had significantly higher rates of resistance organisms (63% ppx 19% placebo).

- The NNT with prophylaxis in children with VUR is 9 children for 2 years to prevent 1 UTI, or 6570 days of antibiotics to prevent one 7-14 day course.

The RIVUR study raised more questions:

- Is there a difference in outcome if a child had concurrent bacteremia?

- There is no significant difference in clinical presentation between an isolated UTI and an infant with bacteremia. Those patients with bacteremia received longer duration of parenteral antibiotics, but the number of days were highly variable and outcomes were excellent overall regardless.

- How accurate is UA in the diagnosis of urinary tract infections in infants less than 3 months of age?

- Urinalysis in those infants

- Could inflammatory markers accurately identify infants at high risk for more severe disease?

- Not really.

Guidelines were reviewed, controversies were discussed, and questions were proposed. The session ended with tools to take home to help change hospital practice, and quality-UTI projects metrics were shared, as this is the next AAP VIP project about to launch.

Key Takeaways:

- The guidelines represent a living and dynamic tool that integrates the best evidence we have.

- There is new research evolving and lessons to be learned.

Dr. Hopkins is an academic pediatric hospitalist and instructor at All Children's Hospital Johns Hopkins Medicine, St. Petersburg, Fla.

VTE-related penalties may be unfair

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Imposing financial penalties on hospitals based on the incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be unfair, according to researchers.

They argue that pay-for-performance systems should take VTE prevention efforts into account, instead of simply tallying the number of hospital-acquired VTEs.

They say the current system fails to account for VTEs that occur despite appropriate use of preventive therapies.

The researchers expressed this viewpoint and disclosed research supporting it in a letter to JAMA Surgery.

“We have a big problem with current pay-for-performance systems based on ‘numbers-only’ total counts of clots, because even when hospitals do everything they can to prevent venous thromboembolism events, they are still being dinged for patients who develop these clots,” said Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“Our study of patients just at The Johns Hopkins Hospital identifies a need to dramatically re-evaluate the venous thromboembolism outcome and process measures. Nearly half of the venous thromboembolism events identified by the state program in the records we reviewed were not truly preventable because patients received best practice prevention and still developed blood clots.”

Dr Haut and his colleagues reviewed case records for 128 patients treated between July 2010 and June 2011 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and who developed hospital-acquired VTE. All 128 were flagged by the Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions pay-for-performance program.

The researchers looked for evidence that all of the VTEs could have been prevented. They found that 36 patients (28%) had nonpreventable, catheter-related upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT), leaving 92 patients (72%) with clots that were potentially preventable.

Of those 92 patients, 45 had a DVT, 43 had a pulmonary embolism (PE), and 4 had a DVT and PE.

Seventy-nine of the 92 patients (86%) were prescribed optimal thromboprophylaxis, yet only 43 (47%) received “defect-free care,” the researchers found.

Of the 49 patients (53%) who received suboptimal care, 13 (27%) were not prescribed risk-appropriate anticoagulants, and 36 (73%) missed at least one dose of appropriately prescribed medication.

Dr Haut noted that a team of physicians, nurses, quality care researchers, and pharmacists at Johns Hopkins has been studying VTE prevention for the past decade.

Team members have implemented programs to monitor patients in need of VTE prophylaxis through the hospital’s electronic health record system, and they conducted special training for nurses and patients to stress the importance of taking every dose of prescribed medication.

“We know we’re not going to get the VTE rate to 0, but my goal is to have every single one of these events—when they happen—occur when the patient receives best-practice, defect-free care,” Dr Haut said.

The current VTE care goal set by agencies like the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is that one dose of VTE prophylaxis is given to patients within the first day of hospitalization. But Dr Haut said this is not enough.

“To reduce preventable harm, policymakers need to re-evaluate how they penalize hospitals and improve the measures they use to assess VTE prevention performance,” he said. “In addition, clinicians need to ensure that patients receive all prescribed preventive therapies.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Imposing financial penalties on hospitals based on the incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be unfair, according to researchers.

They argue that pay-for-performance systems should take VTE prevention efforts into account, instead of simply tallying the number of hospital-acquired VTEs.

They say the current system fails to account for VTEs that occur despite appropriate use of preventive therapies.

The researchers expressed this viewpoint and disclosed research supporting it in a letter to JAMA Surgery.

“We have a big problem with current pay-for-performance systems based on ‘numbers-only’ total counts of clots, because even when hospitals do everything they can to prevent venous thromboembolism events, they are still being dinged for patients who develop these clots,” said Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“Our study of patients just at The Johns Hopkins Hospital identifies a need to dramatically re-evaluate the venous thromboembolism outcome and process measures. Nearly half of the venous thromboembolism events identified by the state program in the records we reviewed were not truly preventable because patients received best practice prevention and still developed blood clots.”

Dr Haut and his colleagues reviewed case records for 128 patients treated between July 2010 and June 2011 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and who developed hospital-acquired VTE. All 128 were flagged by the Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions pay-for-performance program.

The researchers looked for evidence that all of the VTEs could have been prevented. They found that 36 patients (28%) had nonpreventable, catheter-related upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT), leaving 92 patients (72%) with clots that were potentially preventable.

Of those 92 patients, 45 had a DVT, 43 had a pulmonary embolism (PE), and 4 had a DVT and PE.

Seventy-nine of the 92 patients (86%) were prescribed optimal thromboprophylaxis, yet only 43 (47%) received “defect-free care,” the researchers found.

Of the 49 patients (53%) who received suboptimal care, 13 (27%) were not prescribed risk-appropriate anticoagulants, and 36 (73%) missed at least one dose of appropriately prescribed medication.

Dr Haut noted that a team of physicians, nurses, quality care researchers, and pharmacists at Johns Hopkins has been studying VTE prevention for the past decade.

Team members have implemented programs to monitor patients in need of VTE prophylaxis through the hospital’s electronic health record system, and they conducted special training for nurses and patients to stress the importance of taking every dose of prescribed medication.

“We know we’re not going to get the VTE rate to 0, but my goal is to have every single one of these events—when they happen—occur when the patient receives best-practice, defect-free care,” Dr Haut said.

The current VTE care goal set by agencies like the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is that one dose of VTE prophylaxis is given to patients within the first day of hospitalization. But Dr Haut said this is not enough.

“To reduce preventable harm, policymakers need to re-evaluate how they penalize hospitals and improve the measures they use to assess VTE prevention performance,” he said. “In addition, clinicians need to ensure that patients receive all prescribed preventive therapies.” ![]()

Photo courtesy of the CDC

Imposing financial penalties on hospitals based on the incidence of hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism (VTE) may be unfair, according to researchers.

They argue that pay-for-performance systems should take VTE prevention efforts into account, instead of simply tallying the number of hospital-acquired VTEs.

They say the current system fails to account for VTEs that occur despite appropriate use of preventive therapies.

The researchers expressed this viewpoint and disclosed research supporting it in a letter to JAMA Surgery.

“We have a big problem with current pay-for-performance systems based on ‘numbers-only’ total counts of clots, because even when hospitals do everything they can to prevent venous thromboembolism events, they are still being dinged for patients who develop these clots,” said Elliott R. Haut, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

“Our study of patients just at The Johns Hopkins Hospital identifies a need to dramatically re-evaluate the venous thromboembolism outcome and process measures. Nearly half of the venous thromboembolism events identified by the state program in the records we reviewed were not truly preventable because patients received best practice prevention and still developed blood clots.”

Dr Haut and his colleagues reviewed case records for 128 patients treated between July 2010 and June 2011 at The Johns Hopkins Hospital and who developed hospital-acquired VTE. All 128 were flagged by the Maryland Hospital Acquired Conditions pay-for-performance program.

The researchers looked for evidence that all of the VTEs could have been prevented. They found that 36 patients (28%) had nonpreventable, catheter-related upper extremity deep vein thrombosis (DVT), leaving 92 patients (72%) with clots that were potentially preventable.

Of those 92 patients, 45 had a DVT, 43 had a pulmonary embolism (PE), and 4 had a DVT and PE.

Seventy-nine of the 92 patients (86%) were prescribed optimal thromboprophylaxis, yet only 43 (47%) received “defect-free care,” the researchers found.

Of the 49 patients (53%) who received suboptimal care, 13 (27%) were not prescribed risk-appropriate anticoagulants, and 36 (73%) missed at least one dose of appropriately prescribed medication.

Dr Haut noted that a team of physicians, nurses, quality care researchers, and pharmacists at Johns Hopkins has been studying VTE prevention for the past decade.

Team members have implemented programs to monitor patients in need of VTE prophylaxis through the hospital’s electronic health record system, and they conducted special training for nurses and patients to stress the importance of taking every dose of prescribed medication.

“We know we’re not going to get the VTE rate to 0, but my goal is to have every single one of these events—when they happen—occur when the patient receives best-practice, defect-free care,” Dr Haut said.

The current VTE care goal set by agencies like the Joint Commission and the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services is that one dose of VTE prophylaxis is given to patients within the first day of hospitalization. But Dr Haut said this is not enough.

“To reduce preventable harm, policymakers need to re-evaluate how they penalize hospitals and improve the measures they use to assess VTE prevention performance,” he said. “In addition, clinicians need to ensure that patients receive all prescribed preventive therapies.” ![]()

Tool identifies optimal TKI for cancers

Photo courtesy of the

University of Colorado

Researchers say they have developed a tool that allows us to determine which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) will be most effective against a certain type of cancer.

The tool, known as the Kinase Addiction Ranker (KAR), predicts the genetic abnormalities that are driving the cancer in any population of cells and chooses the best TKI or combination of TKIs to target these abnormalities.

The researchers described the tool in Bioinformatics.

“A lot of [TKIs] inhibit a lot more than what they’re supposed to inhibit,” said study author Aik Choon Tan, PhD, of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

“Maybe drug A was designed to inhibit kinase B, but it also inhibits kinase C and D as well. Our approach centers on exploiting the promiscuity of these drugs, the ‘drug spillover.’”

For each TKI, there is a signature describing the kinases each drug fully or partially inhibits. Dr Tan and his colleagues combined these kinase inhibition signatures with the results of high-throughput screening. They used the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database to determine which TKIs have already proven active against which cancer cell lines.

The result is KAR, which does 2 things. For any cancer cell line, the program ranks the kinases that are most important to the growth of the disease. Then, the program recommends the combination of existing TKIs that is likely to do the most good against the implicated kinases.

Dr Tan and his colleagues tested KAR using samples from 151 leukemia patients and found that, among the kinases analyzed, FLT3 had the highest variance in sensitivity to TKIs.

But EPHA5, EPHA3, and BTK were the kinases most commonly associated with drug sensitivity. They had significant associations in 72%, 58%, and 54% of the patient samples, respectively.

The researchers said the frequency of BTK dependence they observed is interesting given the fact that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib produced favorable results in a phase 1b/2 trial of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The progression-free survival rate at 26 months was 75% in that trial.

Dr Tan and his colleagues said this was consistent with their findings, which showed that 70% of CLL patient data had a significant association between BTK inhibition and drug sensitivity.

The researchers also found that KAR could predict TKI sensitivity in 21 lung cancer cell lines. In addition, the tool was able to recommend a combination of TKIs that hindered proliferation in the lung cancer cell line H1581. KAR suggested ponatinib and the experimental anticancer agent AZD8055, and experiments showed that these drugs synergistically reduced proliferation in H1581.

KAR is available for download on the Tan lab’s website. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

University of Colorado

Researchers say they have developed a tool that allows us to determine which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) will be most effective against a certain type of cancer.

The tool, known as the Kinase Addiction Ranker (KAR), predicts the genetic abnormalities that are driving the cancer in any population of cells and chooses the best TKI or combination of TKIs to target these abnormalities.

The researchers described the tool in Bioinformatics.

“A lot of [TKIs] inhibit a lot more than what they’re supposed to inhibit,” said study author Aik Choon Tan, PhD, of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

“Maybe drug A was designed to inhibit kinase B, but it also inhibits kinase C and D as well. Our approach centers on exploiting the promiscuity of these drugs, the ‘drug spillover.’”

For each TKI, there is a signature describing the kinases each drug fully or partially inhibits. Dr Tan and his colleagues combined these kinase inhibition signatures with the results of high-throughput screening. They used the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database to determine which TKIs have already proven active against which cancer cell lines.

The result is KAR, which does 2 things. For any cancer cell line, the program ranks the kinases that are most important to the growth of the disease. Then, the program recommends the combination of existing TKIs that is likely to do the most good against the implicated kinases.

Dr Tan and his colleagues tested KAR using samples from 151 leukemia patients and found that, among the kinases analyzed, FLT3 had the highest variance in sensitivity to TKIs.

But EPHA5, EPHA3, and BTK were the kinases most commonly associated with drug sensitivity. They had significant associations in 72%, 58%, and 54% of the patient samples, respectively.

The researchers said the frequency of BTK dependence they observed is interesting given the fact that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib produced favorable results in a phase 1b/2 trial of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The progression-free survival rate at 26 months was 75% in that trial.

Dr Tan and his colleagues said this was consistent with their findings, which showed that 70% of CLL patient data had a significant association between BTK inhibition and drug sensitivity.

The researchers also found that KAR could predict TKI sensitivity in 21 lung cancer cell lines. In addition, the tool was able to recommend a combination of TKIs that hindered proliferation in the lung cancer cell line H1581. KAR suggested ponatinib and the experimental anticancer agent AZD8055, and experiments showed that these drugs synergistically reduced proliferation in H1581.

KAR is available for download on the Tan lab’s website. ![]()

Photo courtesy of the

University of Colorado

Researchers say they have developed a tool that allows us to determine which tyrosine kinase inhibitor (TKI) will be most effective against a certain type of cancer.

The tool, known as the Kinase Addiction Ranker (KAR), predicts the genetic abnormalities that are driving the cancer in any population of cells and chooses the best TKI or combination of TKIs to target these abnormalities.

The researchers described the tool in Bioinformatics.

“A lot of [TKIs] inhibit a lot more than what they’re supposed to inhibit,” said study author Aik Choon Tan, PhD, of the University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus in Aurora.

“Maybe drug A was designed to inhibit kinase B, but it also inhibits kinase C and D as well. Our approach centers on exploiting the promiscuity of these drugs, the ‘drug spillover.’”

For each TKI, there is a signature describing the kinases each drug fully or partially inhibits. Dr Tan and his colleagues combined these kinase inhibition signatures with the results of high-throughput screening. They used the Genomics of Drug Sensitivity in Cancer database to determine which TKIs have already proven active against which cancer cell lines.

The result is KAR, which does 2 things. For any cancer cell line, the program ranks the kinases that are most important to the growth of the disease. Then, the program recommends the combination of existing TKIs that is likely to do the most good against the implicated kinases.

Dr Tan and his colleagues tested KAR using samples from 151 leukemia patients and found that, among the kinases analyzed, FLT3 had the highest variance in sensitivity to TKIs.

But EPHA5, EPHA3, and BTK were the kinases most commonly associated with drug sensitivity. They had significant associations in 72%, 58%, and 54% of the patient samples, respectively.

The researchers said the frequency of BTK dependence they observed is interesting given the fact that the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib produced favorable results in a phase 1b/2 trial of patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL). The progression-free survival rate at 26 months was 75% in that trial.

Dr Tan and his colleagues said this was consistent with their findings, which showed that 70% of CLL patient data had a significant association between BTK inhibition and drug sensitivity.

The researchers also found that KAR could predict TKI sensitivity in 21 lung cancer cell lines. In addition, the tool was able to recommend a combination of TKIs that hindered proliferation in the lung cancer cell line H1581. KAR suggested ponatinib and the experimental anticancer agent AZD8055, and experiments showed that these drugs synergistically reduced proliferation in H1581.

KAR is available for download on the Tan lab’s website. ![]()

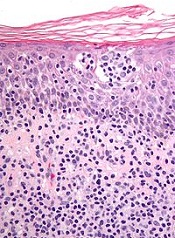

Analysis reveals ‘distinctive biology’ of CTCL

New research suggests cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is driven by a plethora of genetic mutations.

Investigators conducted a genomic analysis of normal and cancer cells from patients with CTCL and identified mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis.

They also found that somatic copy number variants (SCNVs) driving CTCL outnumbered somatic single-nucleotide variants (SSNVs) by more than 10 to 1.

The team reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

They performed exome and whole-genome DNA sequencing and RNA sequencing on purified CTCL cells and matched normal cells. And they identified genes implicated in CTCL pathogenesis by looking for:

- Genes with recurrent SSNVs altering the same amino acid more often than expected by chance

- Genes with SSNVs previously identified as recurrent mutations in other cancers

- Genes having a significantly increased burden of protein-altering SSNVs

- SCNVs that occurred more often than expected by chance.

This revealed mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis—TP53, ZEB1, ARID1A, DNMT3A, CDKN2A, FAS, NFKB2, CD28, RHOA, PLCG1, STAT5B, BRAF, ATM, CTCF, TNFAIP3, PRKCQ, and IRF4.

The investigators noted that these are genes involved in T-cell activation, apoptosis, NF-κB signaling, chromatin remodeling, and DNA damage response.

The team also discovered “a striking bias” for SCNVs as drivers of CTCL. They identified 12 statistically significant chromosome-arm SCNVs and 36 significant focal SCNVs.

Collectively, these SCNVs occurred 473 times in the CTCL samples analyzed—a mean of 7.5 focal deletions, 1.6 broad deletions, 1.0 focal amplification, and 1.8 broad amplifications per CTCL.

On the other hand, there were 38 SSNVs in CTCL driver genes—1.0 per tumor.

So, according to these data, SCNVs comprise 92% of all driver mutations in CTCL—a mean of 11.8 pathogenic SCNVs vs 1.0 SSNV per CTCL.

“This cancer has a very distinctive biology,” said Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

And decoding this biology has revealed potential treatment approaches, according to Dr Choi and his colleagues.

For example, the presence of mutations activating the NF-κB pathway suggests NF-κB inhibitors such as bortezomib may have therapeutic potential in CTCL, and the presence of CD28 mutations suggests inhibitors such as abatacept may be effective against the disease. ![]()

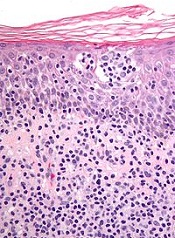

New research suggests cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is driven by a plethora of genetic mutations.

Investigators conducted a genomic analysis of normal and cancer cells from patients with CTCL and identified mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis.

They also found that somatic copy number variants (SCNVs) driving CTCL outnumbered somatic single-nucleotide variants (SSNVs) by more than 10 to 1.

The team reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

They performed exome and whole-genome DNA sequencing and RNA sequencing on purified CTCL cells and matched normal cells. And they identified genes implicated in CTCL pathogenesis by looking for:

- Genes with recurrent SSNVs altering the same amino acid more often than expected by chance

- Genes with SSNVs previously identified as recurrent mutations in other cancers

- Genes having a significantly increased burden of protein-altering SSNVs

- SCNVs that occurred more often than expected by chance.

This revealed mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis—TP53, ZEB1, ARID1A, DNMT3A, CDKN2A, FAS, NFKB2, CD28, RHOA, PLCG1, STAT5B, BRAF, ATM, CTCF, TNFAIP3, PRKCQ, and IRF4.

The investigators noted that these are genes involved in T-cell activation, apoptosis, NF-κB signaling, chromatin remodeling, and DNA damage response.

The team also discovered “a striking bias” for SCNVs as drivers of CTCL. They identified 12 statistically significant chromosome-arm SCNVs and 36 significant focal SCNVs.

Collectively, these SCNVs occurred 473 times in the CTCL samples analyzed—a mean of 7.5 focal deletions, 1.6 broad deletions, 1.0 focal amplification, and 1.8 broad amplifications per CTCL.

On the other hand, there were 38 SSNVs in CTCL driver genes—1.0 per tumor.

So, according to these data, SCNVs comprise 92% of all driver mutations in CTCL—a mean of 11.8 pathogenic SCNVs vs 1.0 SSNV per CTCL.

“This cancer has a very distinctive biology,” said Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

And decoding this biology has revealed potential treatment approaches, according to Dr Choi and his colleagues.

For example, the presence of mutations activating the NF-κB pathway suggests NF-κB inhibitors such as bortezomib may have therapeutic potential in CTCL, and the presence of CD28 mutations suggests inhibitors such as abatacept may be effective against the disease. ![]()

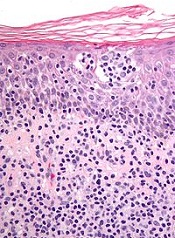

New research suggests cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL) is driven by a plethora of genetic mutations.

Investigators conducted a genomic analysis of normal and cancer cells from patients with CTCL and identified mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis.

They also found that somatic copy number variants (SCNVs) driving CTCL outnumbered somatic single-nucleotide variants (SSNVs) by more than 10 to 1.

The team reported these findings in Nature Genetics.

They performed exome and whole-genome DNA sequencing and RNA sequencing on purified CTCL cells and matched normal cells. And they identified genes implicated in CTCL pathogenesis by looking for:

- Genes with recurrent SSNVs altering the same amino acid more often than expected by chance

- Genes with SSNVs previously identified as recurrent mutations in other cancers

- Genes having a significantly increased burden of protein-altering SSNVs

- SCNVs that occurred more often than expected by chance.

This revealed mutations in 17 genes that are implicated in CTCL pathogenesis—TP53, ZEB1, ARID1A, DNMT3A, CDKN2A, FAS, NFKB2, CD28, RHOA, PLCG1, STAT5B, BRAF, ATM, CTCF, TNFAIP3, PRKCQ, and IRF4.

The investigators noted that these are genes involved in T-cell activation, apoptosis, NF-κB signaling, chromatin remodeling, and DNA damage response.

The team also discovered “a striking bias” for SCNVs as drivers of CTCL. They identified 12 statistically significant chromosome-arm SCNVs and 36 significant focal SCNVs.

Collectively, these SCNVs occurred 473 times in the CTCL samples analyzed—a mean of 7.5 focal deletions, 1.6 broad deletions, 1.0 focal amplification, and 1.8 broad amplifications per CTCL.

On the other hand, there were 38 SSNVs in CTCL driver genes—1.0 per tumor.

So, according to these data, SCNVs comprise 92% of all driver mutations in CTCL—a mean of 11.8 pathogenic SCNVs vs 1.0 SSNV per CTCL.

“This cancer has a very distinctive biology,” said Jaehyuk Choi, MD, PhD, of the Yale School of Medicine in New Haven, Connecticut.

And decoding this biology has revealed potential treatment approaches, according to Dr Choi and his colleagues.

For example, the presence of mutations activating the NF-κB pathway suggests NF-κB inhibitors such as bortezomib may have therapeutic potential in CTCL, and the presence of CD28 mutations suggests inhibitors such as abatacept may be effective against the disease. ![]()

Drones can transport blood samples

Robert Chalmers launch drone

Photo courtesy of

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Small drones can safely transport blood samples, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that 40 minutes of travel on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

The team said that’s promising news for people living in rural and economically impoverished areas that lack passable roads because drones can give healthcare workers quick access to lab tests needed for diagnoses and treatments.

“Biological samples can be very sensitive and fragile,” said study author Timothy Amukele, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

That sensitivity makes even the pneumatic tube systems used by many hospitals, for example, unsuitable for transporting blood for certain purposes.

Of particular concern related to the use of drones, Dr Amukele noted, is the sudden acceleration that marks the launch of the vehicle and the jostling when the drone lands on its belly.

“Such movements could have destroyed blood cells or prompted blood to coagulate, and I thought all kinds of blood tests might be affected, but our study shows they weren’t . . . ,” he said.

For the study, which Dr Amukele believes is the first rigorous examination of the impact of drone transport on biological samples, his team collected 6 blood samples from each of 56 healthy adult volunteers at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The samples were then driven to a flight site an hour’s drive from the hospital on days when the temperature was in the 70s. There, half of the samples were packaged for flight, with a view to protecting them for the in-flight environment and preventing leakage.

Those samples were then loaded into a hand-launched, fixed-wing drone and flown around for periods of 6 to 38 minutes. Owing to Federal Aviation Administration rules, the flights were conducted in an unpopulated area, stayed below 100 meters (328 feet) and were in the line of sight of the certified pilot.

The other samples were driven back from the drone flight field to The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Core Laboratory, where they underwent the 33 most common laboratory tests that account for around 80% of all such tests done. A few of the tests performed were for sodium, glucose, and red blood cell count.

Comparing lab results of the flown versus nonflown blood samples, the investigators found that the flight did not have a significant impact.

Dr Amukele and his team noted that one blood test—the bicarbonate test—did yield different results for some of the flown versus nonflown samples. Dr Amukele said the team isn’t sure why, but the reason could be because the blood sat around for up to 8 hours before being tested.

There were no consistent differences between flown versus nonflown blood, he said, and it’s unknown whether the out-of-range results were due to the time lag or because of the drone transport.

“The ideal way to test that would be to fly the blood around immediately after drawing it, but neither the FAA nor Johns Hopkins would like drones flying around the hospital,” he said.

Given the successful results of this proof-of-concept study, Dr Amukele said the likely next step is a pilot study in a location in Africa where healthcare clinics are sometimes 60 or more miles away from labs.

“A drone could go 100 kilometers in 40 minutes,” he noted. “They’re less expensive than motorcycles and are not subject to traffic delays, and the technology already exists for the drone to be programmed to home to certain GPS coordinates, like a carrier pigeon.”

Drones have already been tested as carriers of medicines to clinics in remote areas, but whether and how drones will be used in flights over populated areas will depend on laws and regulations. ![]()

Robert Chalmers launch drone

Photo courtesy of

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Small drones can safely transport blood samples, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that 40 minutes of travel on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

The team said that’s promising news for people living in rural and economically impoverished areas that lack passable roads because drones can give healthcare workers quick access to lab tests needed for diagnoses and treatments.

“Biological samples can be very sensitive and fragile,” said study author Timothy Amukele, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

That sensitivity makes even the pneumatic tube systems used by many hospitals, for example, unsuitable for transporting blood for certain purposes.

Of particular concern related to the use of drones, Dr Amukele noted, is the sudden acceleration that marks the launch of the vehicle and the jostling when the drone lands on its belly.

“Such movements could have destroyed blood cells or prompted blood to coagulate, and I thought all kinds of blood tests might be affected, but our study shows they weren’t . . . ,” he said.

For the study, which Dr Amukele believes is the first rigorous examination of the impact of drone transport on biological samples, his team collected 6 blood samples from each of 56 healthy adult volunteers at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The samples were then driven to a flight site an hour’s drive from the hospital on days when the temperature was in the 70s. There, half of the samples were packaged for flight, with a view to protecting them for the in-flight environment and preventing leakage.

Those samples were then loaded into a hand-launched, fixed-wing drone and flown around for periods of 6 to 38 minutes. Owing to Federal Aviation Administration rules, the flights were conducted in an unpopulated area, stayed below 100 meters (328 feet) and were in the line of sight of the certified pilot.

The other samples were driven back from the drone flight field to The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Core Laboratory, where they underwent the 33 most common laboratory tests that account for around 80% of all such tests done. A few of the tests performed were for sodium, glucose, and red blood cell count.

Comparing lab results of the flown versus nonflown blood samples, the investigators found that the flight did not have a significant impact.

Dr Amukele and his team noted that one blood test—the bicarbonate test—did yield different results for some of the flown versus nonflown samples. Dr Amukele said the team isn’t sure why, but the reason could be because the blood sat around for up to 8 hours before being tested.

There were no consistent differences between flown versus nonflown blood, he said, and it’s unknown whether the out-of-range results were due to the time lag or because of the drone transport.

“The ideal way to test that would be to fly the blood around immediately after drawing it, but neither the FAA nor Johns Hopkins would like drones flying around the hospital,” he said.

Given the successful results of this proof-of-concept study, Dr Amukele said the likely next step is a pilot study in a location in Africa where healthcare clinics are sometimes 60 or more miles away from labs.

“A drone could go 100 kilometers in 40 minutes,” he noted. “They’re less expensive than motorcycles and are not subject to traffic delays, and the technology already exists for the drone to be programmed to home to certain GPS coordinates, like a carrier pigeon.”

Drones have already been tested as carriers of medicines to clinics in remote areas, but whether and how drones will be used in flights over populated areas will depend on laws and regulations. ![]()

Robert Chalmers launch drone

Photo courtesy of

Johns Hopkins Medicine

Small drones can safely transport blood samples, according to a study published in PLOS ONE.

Investigators found that 40 minutes of travel on hobby-sized drones did not affect the results of common and routine blood tests.

The team said that’s promising news for people living in rural and economically impoverished areas that lack passable roads because drones can give healthcare workers quick access to lab tests needed for diagnoses and treatments.

“Biological samples can be very sensitive and fragile,” said study author Timothy Amukele, MD, PhD, of the Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, Maryland.

That sensitivity makes even the pneumatic tube systems used by many hospitals, for example, unsuitable for transporting blood for certain purposes.

Of particular concern related to the use of drones, Dr Amukele noted, is the sudden acceleration that marks the launch of the vehicle and the jostling when the drone lands on its belly.

“Such movements could have destroyed blood cells or prompted blood to coagulate, and I thought all kinds of blood tests might be affected, but our study shows they weren’t . . . ,” he said.

For the study, which Dr Amukele believes is the first rigorous examination of the impact of drone transport on biological samples, his team collected 6 blood samples from each of 56 healthy adult volunteers at The Johns Hopkins Hospital.

The samples were then driven to a flight site an hour’s drive from the hospital on days when the temperature was in the 70s. There, half of the samples were packaged for flight, with a view to protecting them for the in-flight environment and preventing leakage.

Those samples were then loaded into a hand-launched, fixed-wing drone and flown around for periods of 6 to 38 minutes. Owing to Federal Aviation Administration rules, the flights were conducted in an unpopulated area, stayed below 100 meters (328 feet) and were in the line of sight of the certified pilot.

The other samples were driven back from the drone flight field to The Johns Hopkins Hospital’s Core Laboratory, where they underwent the 33 most common laboratory tests that account for around 80% of all such tests done. A few of the tests performed were for sodium, glucose, and red blood cell count.

Comparing lab results of the flown versus nonflown blood samples, the investigators found that the flight did not have a significant impact.

Dr Amukele and his team noted that one blood test—the bicarbonate test—did yield different results for some of the flown versus nonflown samples. Dr Amukele said the team isn’t sure why, but the reason could be because the blood sat around for up to 8 hours before being tested.

There were no consistent differences between flown versus nonflown blood, he said, and it’s unknown whether the out-of-range results were due to the time lag or because of the drone transport.

“The ideal way to test that would be to fly the blood around immediately after drawing it, but neither the FAA nor Johns Hopkins would like drones flying around the hospital,” he said.

Given the successful results of this proof-of-concept study, Dr Amukele said the likely next step is a pilot study in a location in Africa where healthcare clinics are sometimes 60 or more miles away from labs.

“A drone could go 100 kilometers in 40 minutes,” he noted. “They’re less expensive than motorcycles and are not subject to traffic delays, and the technology already exists for the drone to be programmed to home to certain GPS coordinates, like a carrier pigeon.”

Drones have already been tested as carriers of medicines to clinics in remote areas, but whether and how drones will be used in flights over populated areas will depend on laws and regulations. ![]()

10 Tips for Hospitalists to Achieve an Effective Medical Consult

A medical consult is an amazing way to learn. Consultation challenges us to practice our best medicine while also exposing us to innovations in other specialties. It can forge new and productive relationships with physicians from all specialties. At its best, it is the purest of medicine or, as some put it, “medicine without the drama.”

As hospitalists, we are increasingly asked to be medical consultants and co-managers. Yet most training programs spend very little time educating residents on what makes a high-quality consultation. One of the first articles written on this subject was by Lee Goldman and colleagues in 1983. In this article, Goldman sets out 10 commandments for effective consultation.1

Many of the lessons in these 10 commandments continue to ring true today. As primary providers, we know that consulting another service can run the gamut from being pleasant, helpful, and enlightening to being the most frustrating, slam-the-phone-down experience of the day. In this article, we update these commandments to create five golden rules for medical consultations that ensure that your referring providers’ experiences are purely positive.

One warning about communication: If you do not agree with the primary team’s plan of care, make sure you discuss these concerns instead of just writing them in the chart. Any teaching moments should be reserved for those who are open to that discussion, not forced on providers who are not receptive to it at that time.

Five Golden Rules

1 Listen and determine the needs of your customer.

Understanding the needs of your requesting physician is paramount to being an effective consultant, and the first step is to determine the physician’s question. Some referring providers want the bird’s eye view of a general medicine consult, whereas others have just one specific question. In one study stratified by specialty, 59% of surgeons preferred a general medicine consult, while most non-surgeons preferred a focused consult.2

Next, establish the timeframe: Is it emergent, urgent, or routine? One rule of thumb is that all consults should be seen within 24 hours. But many consults need to be seen more quickly, or even immediately. For example, you may be correct to assume that a patient is stable enough to wait for your consult, but perhaps the lack of pre-operative medical assessment will cause her to lose her spot on the OR schedule. The orthopedic surgeon now operates late into the night. Truly understanding the needs of your referring provider might have avoided that scenario.

There are of course times when you really can’t get to a consult expeditiously, but you must let the referring provider know. Ultimately, once you agree upon the urgency, all parties, including the patient, will know when to expect the consultant at the bedside.

2 Look for yourself, and do it yourself.

We practice in an age in which we spend more time in front of computers than in front of patients. As Lee and colleagues write, “A consultant should not expect to make brilliant diagnostic conclusions based on an assessment of data that are already in the chart. Usually, if the answer could be deduced from this information, the consultations would not have been called.”1 Effective consultants always obtain their own history and physical—your special expertise may allow you to extract overlooked information.

In addition, simply leaving recommendations to repeat tests or obtain records often delays care. If you feel the information is vital, take it upon yourself to obtain it. This may include contacting outside primary care providers or medicine subspecialists, or getting outside records.

Although we are not the primary provider, our goal must always be to do what is best for our patients.

3 Make brief, detailed plans with contingencies.

Recommendations can easily be lost in the deluge of information bombarding the primary care team. Our goal is not only to make recommendations, but also to have them followed.

In a study looking at which aspects of a consultation lead to increased compliance, researchers noted that if dose and duration of therapy were not specified, 64% of recommendations were implemented.3 When only one was specified, implementation increased to 85%, and when both were specified, implementation rates increased to 100%. Sadly, only 15% of over 200 consults had both duration and dose in their recommendations. Another study on compliance found that when five or fewer recommendations were specified, compliance increased from 79% to 96%.4

Contingency plans are a way of life for hospitalists when we sign out. Consultations are no different. Patients we consult on are often critically ill, and their status is dynamic. Anticipating problems and giving recommendations if those problems arise can save valuable time later for both you and your colleagues.

As consultants, we often feel compelled to “do something,” yet we know as primary providers how frustrating it is to have a consultant ask for a battery of tests or treatments that don’t address the big picture. Never be afraid to recommend continuing current management if it is appropriate or even to recommend stopping treatment or avoiding additional testing when it does not help the patient.

In summary, consults are most effective when they are brief (five or fewer recommendations), are detailed, and provide contingency plans. What good is a great consultation if it is not followed?

4 Communicate, communicate, communicate.

When 323 surgeons and non-surgeons were surveyed, both groups agreed that initial recommendations should be discussed verbally. Direct verbal communication allows the primary team to provide important information that you may have missed. In addition, discussing recommendations improves compliance and allows everyone to agree on the next plan of action and provide a unified plan to the patient, improving patient satisfaction and adherence.

Lastly and most importantly, opening the lines of communication between consultant and requesting physician creates effective consulting relationships.

Developing this relationship with other services may mean that the next time you call them for a consult, you will already have good rapport to build on.

One warning about communication: If you do not agree with the primary team’s plan of care, make sure you discuss these concerns instead of just writing them in the chart. Any teaching moments should be reserved for those who are open to that discussion, not forced on providers who are not receptive to it at that time.

5 Follow up.

Several studies have shown that follow-up notes improve compliance with recommendations.3,5 Follow-up is also important to ensure that critical recommendations are followed and that any changes in patient status can be addressed. Furthermore, following up can provide valuable feedback on your own initial clinical judgment. Finally, it is bad practice to recommend testing and then sign off before these tests are completed. Either you feel they are important to patient care and worth obtaining, or they are not needed.

Following these five golden rules can ensure that you are the consultant who gives other physicians the satisfying experience of an effective and great consult. If it’s done right, the experience of a general medicine consult is the purest of medicine.

Dr. Chang is assistant professor, inpatient medicine clerkship director, and director of education in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor and director of medicine consult preoperative services in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755.

- Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, Mercado DL. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271-275.

- Horwitz RI, Henes CG, Horwitz SM. Developing strategies for improving the diagnostic and management efficacy of medical consultations. J Chron Dis. 1983;36(2):213-218.

- Sears CL, Charlson ME. The effectiveness of a consultation: compliance with initial recommendations. Am J Med. 1983;74(5):870-876.

- MacKenzie TB, Popkin MK, Callies AL, Jorgensen CR, Cohn JN. The effectiveness of cardiology consultations. Concordance with diagnostic and drug recommendations. Chest. 1981;79(1):16-22.

A medical consult is an amazing way to learn. Consultation challenges us to practice our best medicine while also exposing us to innovations in other specialties. It can forge new and productive relationships with physicians from all specialties. At its best, it is the purest of medicine or, as some put it, “medicine without the drama.”

As hospitalists, we are increasingly asked to be medical consultants and co-managers. Yet most training programs spend very little time educating residents on what makes a high-quality consultation. One of the first articles written on this subject was by Lee Goldman and colleagues in 1983. In this article, Goldman sets out 10 commandments for effective consultation.1

Many of the lessons in these 10 commandments continue to ring true today. As primary providers, we know that consulting another service can run the gamut from being pleasant, helpful, and enlightening to being the most frustrating, slam-the-phone-down experience of the day. In this article, we update these commandments to create five golden rules for medical consultations that ensure that your referring providers’ experiences are purely positive.

One warning about communication: If you do not agree with the primary team’s plan of care, make sure you discuss these concerns instead of just writing them in the chart. Any teaching moments should be reserved for those who are open to that discussion, not forced on providers who are not receptive to it at that time.

Five Golden Rules

1 Listen and determine the needs of your customer.

Understanding the needs of your requesting physician is paramount to being an effective consultant, and the first step is to determine the physician’s question. Some referring providers want the bird’s eye view of a general medicine consult, whereas others have just one specific question. In one study stratified by specialty, 59% of surgeons preferred a general medicine consult, while most non-surgeons preferred a focused consult.2

Next, establish the timeframe: Is it emergent, urgent, or routine? One rule of thumb is that all consults should be seen within 24 hours. But many consults need to be seen more quickly, or even immediately. For example, you may be correct to assume that a patient is stable enough to wait for your consult, but perhaps the lack of pre-operative medical assessment will cause her to lose her spot on the OR schedule. The orthopedic surgeon now operates late into the night. Truly understanding the needs of your referring provider might have avoided that scenario.

There are of course times when you really can’t get to a consult expeditiously, but you must let the referring provider know. Ultimately, once you agree upon the urgency, all parties, including the patient, will know when to expect the consultant at the bedside.

2 Look for yourself, and do it yourself.

We practice in an age in which we spend more time in front of computers than in front of patients. As Lee and colleagues write, “A consultant should not expect to make brilliant diagnostic conclusions based on an assessment of data that are already in the chart. Usually, if the answer could be deduced from this information, the consultations would not have been called.”1 Effective consultants always obtain their own history and physical—your special expertise may allow you to extract overlooked information.

In addition, simply leaving recommendations to repeat tests or obtain records often delays care. If you feel the information is vital, take it upon yourself to obtain it. This may include contacting outside primary care providers or medicine subspecialists, or getting outside records.

Although we are not the primary provider, our goal must always be to do what is best for our patients.

3 Make brief, detailed plans with contingencies.

Recommendations can easily be lost in the deluge of information bombarding the primary care team. Our goal is not only to make recommendations, but also to have them followed.

In a study looking at which aspects of a consultation lead to increased compliance, researchers noted that if dose and duration of therapy were not specified, 64% of recommendations were implemented.3 When only one was specified, implementation increased to 85%, and when both were specified, implementation rates increased to 100%. Sadly, only 15% of over 200 consults had both duration and dose in their recommendations. Another study on compliance found that when five or fewer recommendations were specified, compliance increased from 79% to 96%.4

Contingency plans are a way of life for hospitalists when we sign out. Consultations are no different. Patients we consult on are often critically ill, and their status is dynamic. Anticipating problems and giving recommendations if those problems arise can save valuable time later for both you and your colleagues.

As consultants, we often feel compelled to “do something,” yet we know as primary providers how frustrating it is to have a consultant ask for a battery of tests or treatments that don’t address the big picture. Never be afraid to recommend continuing current management if it is appropriate or even to recommend stopping treatment or avoiding additional testing when it does not help the patient.

In summary, consults are most effective when they are brief (five or fewer recommendations), are detailed, and provide contingency plans. What good is a great consultation if it is not followed?

4 Communicate, communicate, communicate.

When 323 surgeons and non-surgeons were surveyed, both groups agreed that initial recommendations should be discussed verbally. Direct verbal communication allows the primary team to provide important information that you may have missed. In addition, discussing recommendations improves compliance and allows everyone to agree on the next plan of action and provide a unified plan to the patient, improving patient satisfaction and adherence.

Lastly and most importantly, opening the lines of communication between consultant and requesting physician creates effective consulting relationships.

Developing this relationship with other services may mean that the next time you call them for a consult, you will already have good rapport to build on.

One warning about communication: If you do not agree with the primary team’s plan of care, make sure you discuss these concerns instead of just writing them in the chart. Any teaching moments should be reserved for those who are open to that discussion, not forced on providers who are not receptive to it at that time.

5 Follow up.

Several studies have shown that follow-up notes improve compliance with recommendations.3,5 Follow-up is also important to ensure that critical recommendations are followed and that any changes in patient status can be addressed. Furthermore, following up can provide valuable feedback on your own initial clinical judgment. Finally, it is bad practice to recommend testing and then sign off before these tests are completed. Either you feel they are important to patient care and worth obtaining, or they are not needed.

Following these five golden rules can ensure that you are the consultant who gives other physicians the satisfying experience of an effective and great consult. If it’s done right, the experience of a general medicine consult is the purest of medicine.

Dr. Chang is assistant professor, inpatient medicine clerkship director, and director of education in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai Medical Center in New York City. Dr. Gabriel is assistant professor and director of medicine consult preoperative services in the division of hospital medicine at Mount Sinai.

References

- Goldman L, Lee T, Rudd P. Ten commandments for effective consultations. Arch Intern Med. 1983;143(9):1753-1755.

- Salerno SM, Hurst FP, Halvorson S, Mercado DL. Principles of effective consultation: an update for the 21st-century consultant. Arch Intern Med. 2007;167(3):271-275.

- Horwitz RI, Henes CG, Horwitz SM. Developing strategies for improving the diagnostic and management efficacy of medical consultations. J Chron Dis. 1983;36(2):213-218.

- Sears CL, Charlson ME. The effectiveness of a consultation: compliance with initial recommendations. Am J Med. 1983;74(5):870-876.

- MacKenzie TB, Popkin MK, Callies AL, Jorgensen CR, Cohn JN. The effectiveness of cardiology consultations. Concordance with diagnostic and drug recommendations. Chest. 1981;79(1):16-22.

A medical consult is an amazing way to learn. Consultation challenges us to practice our best medicine while also exposing us to innovations in other specialties. It can forge new and productive relationships with physicians from all specialties. At its best, it is the purest of medicine or, as some put it, “medicine without the drama.”

As hospitalists, we are increasingly asked to be medical consultants and co-managers. Yet most training programs spend very little time educating residents on what makes a high-quality consultation. One of the first articles written on this subject was by Lee Goldman and colleagues in 1983. In this article, Goldman sets out 10 commandments for effective consultation.1

Many of the lessons in these 10 commandments continue to ring true today. As primary providers, we know that consulting another service can run the gamut from being pleasant, helpful, and enlightening to being the most frustrating, slam-the-phone-down experience of the day. In this article, we update these commandments to create five golden rules for medical consultations that ensure that your referring providers’ experiences are purely positive.

One warning about communication: If you do not agree with the primary team’s plan of care, make sure you discuss these concerns instead of just writing them in the chart. Any teaching moments should be reserved for those who are open to that discussion, not forced on providers who are not receptive to it at that time.

Five Golden Rules

1 Listen and determine the needs of your customer.

Understanding the needs of your requesting physician is paramount to being an effective consultant, and the first step is to determine the physician’s question. Some referring providers want the bird’s eye view of a general medicine consult, whereas others have just one specific question. In one study stratified by specialty, 59% of surgeons preferred a general medicine consult, while most non-surgeons preferred a focused consult.2

Next, establish the timeframe: Is it emergent, urgent, or routine? One rule of thumb is that all consults should be seen within 24 hours. But many consults need to be seen more quickly, or even immediately. For example, you may be correct to assume that a patient is stable enough to wait for your consult, but perhaps the lack of pre-operative medical assessment will cause her to lose her spot on the OR schedule. The orthopedic surgeon now operates late into the night. Truly understanding the needs of your referring provider might have avoided that scenario.

There are of course times when you really can’t get to a consult expeditiously, but you must let the referring provider know. Ultimately, once you agree upon the urgency, all parties, including the patient, will know when to expect the consultant at the bedside.

2 Look for yourself, and do it yourself.

We practice in an age in which we spend more time in front of computers than in front of patients. As Lee and colleagues write, “A consultant should not expect to make brilliant diagnostic conclusions based on an assessment of data that are already in the chart. Usually, if the answer could be deduced from this information, the consultations would not have been called.”1 Effective consultants always obtain their own history and physical—your special expertise may allow you to extract overlooked information.

In addition, simply leaving recommendations to repeat tests or obtain records often delays care. If you feel the information is vital, take it upon yourself to obtain it. This may include contacting outside primary care providers or medicine subspecialists, or getting outside records.

Although we are not the primary provider, our goal must always be to do what is best for our patients.

3 Make brief, detailed plans with contingencies.

Recommendations can easily be lost in the deluge of information bombarding the primary care team. Our goal is not only to make recommendations, but also to have them followed.

In a study looking at which aspects of a consultation lead to increased compliance, researchers noted that if dose and duration of therapy were not specified, 64% of recommendations were implemented.3 When only one was specified, implementation increased to 85%, and when both were specified, implementation rates increased to 100%. Sadly, only 15% of over 200 consults had both duration and dose in their recommendations. Another study on compliance found that when five or fewer recommendations were specified, compliance increased from 79% to 96%.4

Contingency plans are a way of life for hospitalists when we sign out. Consultations are no different. Patients we consult on are often critically ill, and their status is dynamic. Anticipating problems and giving recommendations if those problems arise can save valuable time later for both you and your colleagues.

As consultants, we often feel compelled to “do something,” yet we know as primary providers how frustrating it is to have a consultant ask for a battery of tests or treatments that don’t address the big picture. Never be afraid to recommend continuing current management if it is appropriate or even to recommend stopping treatment or avoiding additional testing when it does not help the patient.

In summary, consults are most effective when they are brief (five or fewer recommendations), are detailed, and provide contingency plans. What good is a great consultation if it is not followed?

4 Communicate, communicate, communicate.

When 323 surgeons and non-surgeons were surveyed, both groups agreed that initial recommendations should be discussed verbally. Direct verbal communication allows the primary team to provide important information that you may have missed. In addition, discussing recommendations improves compliance and allows everyone to agree on the next plan of action and provide a unified plan to the patient, improving patient satisfaction and adherence.

Lastly and most importantly, opening the lines of communication between consultant and requesting physician creates effective consulting relationships.