User login

In reply: The role of sentinel lymph node biopsy after excision of melanomas

In Reply: Thank you for your important question. Examination of the excision specimen of the patient’s primary cutaneous melanoma lesion demonstrated a Breslow depth of 1.92 mm. He did indeed undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy at the time of excision. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen was negative for evidence of metastatic melanoma. Despite this, he obviously developed metastatic disease several years later.

As you allude to, sentinel lymph node biopsy is an important minimally invasive procedure in patients with melanoma. Morton et al1 compared it with nodal observation and found that in patients with at least intermediate-thickness cutaneous melanoma, sentinel node biopsy significantly prolonged disease-free survival for all patients and improved melanoma-specific survival rates for patients with nodal metastases from intermediate-thickness melanomas (1.2–3.5 mm).1 However, it remains an imperfect procedure, and a percentage of patients develop recurrence or metastasis despite a negative biopsy. In a recent study by Jones et al,2 16% of melanoma patients in a cohort with a negative sentinel node biopsy developed recurrence.2 In these unfortunate patients, medications such as CTLA-4 inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors now offer hope for prolonged survival.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al, for the MSLT Group. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:599–609.

- Jones EL, Jones TS, Nathan Pearlman NW, et al. Long-term follow-up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg 2013; 148:456–461.

In Reply: Thank you for your important question. Examination of the excision specimen of the patient’s primary cutaneous melanoma lesion demonstrated a Breslow depth of 1.92 mm. He did indeed undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy at the time of excision. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen was negative for evidence of metastatic melanoma. Despite this, he obviously developed metastatic disease several years later.

As you allude to, sentinel lymph node biopsy is an important minimally invasive procedure in patients with melanoma. Morton et al1 compared it with nodal observation and found that in patients with at least intermediate-thickness cutaneous melanoma, sentinel node biopsy significantly prolonged disease-free survival for all patients and improved melanoma-specific survival rates for patients with nodal metastases from intermediate-thickness melanomas (1.2–3.5 mm).1 However, it remains an imperfect procedure, and a percentage of patients develop recurrence or metastasis despite a negative biopsy. In a recent study by Jones et al,2 16% of melanoma patients in a cohort with a negative sentinel node biopsy developed recurrence.2 In these unfortunate patients, medications such as CTLA-4 inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors now offer hope for prolonged survival.

In Reply: Thank you for your important question. Examination of the excision specimen of the patient’s primary cutaneous melanoma lesion demonstrated a Breslow depth of 1.92 mm. He did indeed undergo sentinel lymph node biopsy at the time of excision. Histologic examination of the biopsy specimen was negative for evidence of metastatic melanoma. Despite this, he obviously developed metastatic disease several years later.

As you allude to, sentinel lymph node biopsy is an important minimally invasive procedure in patients with melanoma. Morton et al1 compared it with nodal observation and found that in patients with at least intermediate-thickness cutaneous melanoma, sentinel node biopsy significantly prolonged disease-free survival for all patients and improved melanoma-specific survival rates for patients with nodal metastases from intermediate-thickness melanomas (1.2–3.5 mm).1 However, it remains an imperfect procedure, and a percentage of patients develop recurrence or metastasis despite a negative biopsy. In a recent study by Jones et al,2 16% of melanoma patients in a cohort with a negative sentinel node biopsy developed recurrence.2 In these unfortunate patients, medications such as CTLA-4 inhibitors and PD-1 inhibitors now offer hope for prolonged survival.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al, for the MSLT Group. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:599–609.

- Jones EL, Jones TS, Nathan Pearlman NW, et al. Long-term follow-up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg 2013; 148:456–461.

- Morton DL, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al, for the MSLT Group. Final trial report of sentinel-node biopsy versus nodal observation in melanoma. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:599–609.

- Jones EL, Jones TS, Nathan Pearlman NW, et al. Long-term follow-up and survival of patients following a recurrence of melanoma after a negative sentinel lymph node biopsy result. JAMA Surg 2013; 148:456–461.

Long-acting reversible contraception: Who, what, when, and how

› Suggest long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine devices (IUDs), as a first-line method of contraception to most women, including adolescents and nulliparous women. A

› Offer immediate post-placental insertion of LARC when counseling women who have barriers to seeking contraception at a postpartum visit or are unlikely to return for a postpartum visit. B

› Treat sexually transmitted infections in most cases without removing an IUD that is already in place. Consider removing the IUD, however, if there is no clinical improvement after 2 to 3 days of antibiotics. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The number of women using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in the United States has been increasing, with current use accounting for approximately 18% of reversible contraception, according to the National Survey of Family Growth.1,2 LARC includes any method of contraception that lasts ≥3 years, is easily reversed, and does not rely on the user to maintain efficacy. Five LARC devices are available in the United States: 4 intrauterine devices (IUDs) and one subdermal implant.

The number of women using LARC is surprisingly low, given that it is considered a first-line contraceptive method for most women and adolescents,3 and when compared with other forms of reversible contraception, is more efficacious,4-6 has higher satisfaction rates,7-9 and higher rates of continuation.9 In fact, the Contraceptive CHOICE Project—a St. Louis community-based research program promoting and enabling access to reversible contraceptive methods—has shown that when appropriate counseling is provided and cost barriers are removed, up to 79% of women choose LARC as their preferred method of contraception.10

CASES › Jenny, who is 16 years old, comes to your office with her mother to discuss contraceptive options. She is nulliparous, has regular menses, and, aside from a body mass index (BMI) of 28, has no medical problems. Her mother is concerned about Jenny becoming pregnant while she is still in high school.

Maria D, a 32-year-old G2P1, comes in for a prenatal visit with her husband. She tells you that after delivery she is interested in a long-acting contraceptive, but is planning on breastfeeding and does not want anything to interfere with that.

What LARC options do these and other patients have?

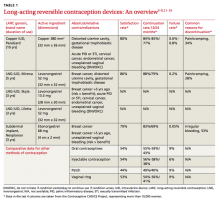

The 4 IUDs and one implant approved for use are all viable options depending on a patient’s preference and comorbidities (TABLE 1).3-9,11-15 The copper IUD is the oldest method of LARC available and the only one that is nonhormonal. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use up to 10 years,11 but studies support its effectiveness for up to 12 years.16

The remaining IUDs (Skyla, Liletta, Mirena) contain varying amounts of the progestin levonorgestrel (LNG), released by each device at a slightly different rate that declines over time. Skyla releases a significantly lower dose of hormone than Liletta or Mirena.12-14 Skyla and Liletta are FDA-approved for up to 3 years of use,12,13 and Liletta is currently undergoing trials to gain approval for use up to 5 years. Mirena is FDA-approved for use up to 5 years,14 but studies have shown that it can be effective for 7 years.4,16

The only implant available in the US is Nexplanon, a plastic rod containing 68 mg of etonorgestrel. It is inserted subdermally and is FDA-approved for use up to 3 years.15

Through systemic hormonal effects, the primary mechanism of action of the implant is prevention of ovulation. Additionally, the implant has been shown to inhibit endometrial proliferation and cervical mucus thickening, both of which may contribute to the implant’s overall effectiveness.17 In contrast, both the copper IUD and the LNG-IUDs work primarily by preventing fertilization. The LNG-IUDs also exhibit local hormonal effects (endometrial atrophy and thickened cervical mucus) that contribute to their effectiveness.17

Who is eligible for LARC?

LARC is suitable for the vast majority of women of reproductive age. For most multiparous women ≥20 years, all LARC devices are classified as category 1 (use without restriction) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC).3 For women <20 years, the implant is also considered category 1, but IUDs in this age group are classified as category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) because of concerns about an increased risk of IUD expulsion and the increased prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in adolescents.3 Contraindications to use of LARC vary depending on the method chosen (TABLE 1).3

There has been concern about the efficacy of implants in overweight women because the original trials of subdermal implants excluded women >130% of ideal body weight. However, according to the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, overweight and obese women enrolled in its program did not experience reduced contraceptive efficacy when using the implant when compared with normal-weight women.18

When can LARC devices be inserted?

LARC device insertion is possible at any time during the menstrual cycle. An algorithm to guide initiation of LARC is available through the Reproductive Health Access Project’s Web site at http://www.reproductiveaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/quickstart_algorithm.pdf.

Rule out pregnancy before placing any LARC device. The copper IUD can be inserted at any time during the menstrual cycle without the need for back-up contraception.11,19 In contrast, for LNG-IUDs, back-up contraception is recommended for 7 days unless the insertion is done during the first 7 days of the menstrual cycle.12-14,19

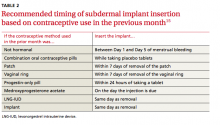

For the implant, recommendations about when to insert are based on a woman’s previous method of contraception (TABLE 2).15 If insertion is done at a time other than when recommended, advise patients to use barrier protection for 7 days after insertion.4,15,19

Other issues often arise and cause concern about whether and when a LARC device can be inserted, including the possibility of undiagnosed STI, time elapsed since delivery, and advisability of use when breastfeeding.

Sexually transmitted infections and IUDs

Whether or not a woman chooses to receive an IUD, follow routine CDC guidelines in determining if a patient is a candidate for STI screening.20 If a woman wants an IUD and routine screening is recommended, you can perform screening on the day of IUD insertion.4,19 For women with an IUD already in place who are diagnosed with an STI, treat the infection while leaving the IUD in place.19 For women with a known or suspected STI who do not have an IUD already, treat the STI before inserting the IUD. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises postponing insertion of an IUD until a negative STI test result is obtained 3 to 4 weeks after treatment completion.4

Breastfeeding concerns and timing of insertion postpartum

The US MEC classifies insertion of the copper IUD as category 1 for all postpartum women, regardless of breastfeeding status, if placed >4 weeks postpartum or immediately postpartum (defined as within 10 minutes of the delivery of the placenta). IUD placement is category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) if placed ≥10 minutes after placental delivery (until 4 weeks postpartum) because of an increased risk of expulsion.3

The US MEC also considers use of the implant and LNG-IUDs in breastfeeding women as category 1 if the device is placed at ≥4 weeks postpartum. Insertion at <4 weeks postpartum is considered category 2 because of concerns for decreased breast milk supply.3 However, studies on whether progestin-containing LARC devices affect breastfeeding have yielded varying results. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 69 breastfeeding women using the implant, breastfeeding duration and milk production were not dependent on the timing of insertion after delivery.21 Another RCT of 96 women using LNG-IUDs showed fewer women continued to breastfeed at 6 months when their LNG-IUD was inserted immediately postpartum, compared with waiting 6 weeks.22

In addition to a concern about breast milk supply, breastfeeding women have a higher risk for uterine perforation from IUDs, especially during the first 36 weeks after delivery.23

Several studies have shown that there is a lower repeat pregnancy rate among women who receive immediate postpartum LARC placement.24 However, even if IUD insertion is performed immediately postpartum, there is a higher expulsion rate than when the IUD is inserted ≥4 weeks postpartum. The expulsion rates for insertion <10 minutes after vaginal delivery range from 9.5% to 15% for the copper IUD to as high as 24% for the LNG-IUDs. Expulsion rates for all IUDs are slightly lower for cesarean delivery.4,25,26 ACOG supports immediate post-placental placement for women with barriers to postpartum care or limited access to contraception.4

How can I help my patients make an informed choice?

Provide counseling on efficacy, common adverse effects, risks, and complications.

Efficacy is high

The failure rate of LARC is equal to, or lower than, that of female sterilization and is significantly lower than that of oral contraceptives (TABLE 1).4-6 Not only are LARC devices extremely effective, they have a higher rate of satisfaction than any other reversible contraceptive (TABLE 1).7,8

Common adverse effects

The most common adverse effect seen with all LARC devices is an alteration in menstrual bleeding, and a frequent adverse effect with IUDs is pain. Vaginitis is less common and can be seen with any of the devices. The progestin-containing LARC devices are associated with hormonal effects: vaginitis, headache, weight gain, acne, breast pain, hair loss, and emotional lability.12-15

Copper IUD. Many women using the copper IUD experience either a transient increase in menstrual bleeding lasting for a few months or inter-menstrual bleeding that tends to continue for the duration of use.4,17 However, according to data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of the copper IUD is pain and cramping.9

LNG-IUDs. Like the copper IUD, many users of LNG-IUDs experience an initial increase in menstrual bleeding. However, unlike the other LARC devices, 20% to 33% of Mirena users are likely to experience amenorrhea after one year of use and 70% at 2 years.4,14 According to package inserts, amenorrhea after 3 years is less common with both Skyla (12%) and Liletta (38%).12,13 As with the copper IUD, based on data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of LNG-IUDs is pain and cramping.9

Subdermal implant. Changes in menses in women using the subdermal implant range from amenorrhea (22%) to prolonged bleeding (18%).15,17 Although it is difficult to predict which pattern a particular woman will experience, heavier women are more likely to have heavier bleeding patterns, and initial bleeding patterns are predictive of future ones.4 The most common reason women choose to discontinue use of the implant is abnormal bleeding.4,9,27,28

Newer IUDs do not increase risk of STIs

Many patients and clinicians erroneously believe that IUDs increase the risk of STIs and therefore assume that patients with a history of STI are not appropriate candidates for an IUD.29 There is a slightly increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the first 21 days after insertion of an IUD. However, in contrast to older IUDs, currently available IUDs do not increase the general risk for STIs.17,30

Risk of infertility is nil

There is no risk of infertility from use of currently available LARCs. For those who want to become pregnant, fertility typically returns immediately after removal of the device, regardless of which method of LARC is used.11-15,30

Complications of IUD insertion

Uterine perforation. Uterine perforation occurs in 0.8 to 2.1 per 1000 women, usually at the time of IUD placement. If IUD strings are not visible during a speculum examination, locate the IUD with ultrasound.4,17,30 If the IUD is in the abdomen, refer to a gynecologist for laparoscopic removal and select another form of contraception for use in the interim.30

Expulsion. Rates of expulsion are low, occurring in less than 10% of women4,17 and are not affected by parity or BMI.31 Expulsion rates are higher when the IUD is inserted immediately postpartum.4,25,26 Adolescents also have a 2-fold higher risk of uterine expulsion than older women.31

Ectopic pregnancy. Although a woman’s overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is not increased by using an IUD,4 it is true that if a woman becomes pregnant with an IUD in place, the pregnancy is more likely to be ectopic. Thus, if pregnancy is confirmed in a woman with an IUD in place, rule out ectopic pregnancy.

The FDA and the World Health Organization recommend that if an intrauterine pregnancy is confirmed with an IUD in place and the strings are visible, the IUD should be removed.4 Although removing the IUD increases the risk of spontaneous abortion (SAB) as compared with pregnancies without an IUD in place, the risk of SAB is still lower than if the IUD is left in place.4 Additional risks of continuing a pregnancy with an IUD in place include increased risks of preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and septic abortion.4,30

Complications of subdermal implant insertion

After insertion of the implant, women usually experience temporary bruising and soreness at the insertion site. Less than 1% of women develop an infection or hematoma.17 There is a low risk of nerve damage if the implant is inserted too deeply.15 Removal of the subdermal implant is recommended if pregnancy occurs.15

CASE DECISIONS › Jenny has been using oral contraceptive pills, but not regularly. You suggest that LARC may be a better option and counsel her that if she does choose an IUD or the implant, it is likely that her menses will change. You provide information and reassurance that LARC is safe to use in adolescents. Jenny says she would like to try an implant. Six months later, Jenny returns and says the implant is working well. She has some irregular bleeding, but it is not bothersome.

You review with Ms. D the types of LARC devices available and reassure her that all are safe to use once breastfeeding is established. Ms. D says she would like to use an IUD and elects to wait until her postpartum visit to have an IUD inserted. Ms. D returns 6 months after IUD insertion; breastfeeding is going well, and she has not had any menstrual bleeding since delivery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn Kolman, MD, 2800 East Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected]

1. Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-44: United States 2011-2013. NCHS data brief, no. 173. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014.

2. Branum AM, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among US women aged 15-44. NCHS data brief, no. 188. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:184-196.

5. Pickle S, Wu J, Burbank-Schmitt E. Prevention of unintended pregnancy: a focus on long-acting reversible contraception. Prim Care. 2014;41:239-260.

6. Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998-2007.

7. Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

8. O’Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1083-1091.

9. Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, et al. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

10. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

11. ParaGard T 380A. (intrauterine copper contraceptive) [package insert]. Sellersville, PA : Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 2013.

12. Skyla (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Wayne, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2013.

13. Liletta (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ : Actavis Pharma, Inc., 2015.

14. Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Whippany, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2014.

15. Nexplanon (etongestrel implant) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co Inc.; 2014.

16. Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89:495-503.

17. Stoddard A, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Efficacy and safety of long-acting reversible contraception. Drugs. 2011;71:969-980.

18. Xu H, Wade JA, Peipert JF, et al. Contraceptive failure rates of etonogestrel subdermal implants in overweight and obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:21-26.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-60.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-110.

21. Gurtcheff SE, Turok DK, Stoddard G, et al. Lactogenesis after early postpartum use of the contraceptive implant: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1114-1121.

22. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504.

23. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

24. Tocce K, Sheeder J, Python J, et al. Long acting reversible contraception in postpartum adolescents: early initiation of etonogestrel implant is superior to IUDs in the outpatient setting. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:59-63.

25. Mwalwanda CS, Black KI. Immediate post-partum initiation of intrauterine contraception and implants: a review of the safety and guidelines for use. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:331-337.

26. Sober, S, Schreiber CA. Postpartum contraception. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:763-776.

27. Dickerson LM, Diaz VA, Jordon J, et al. Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long-acting reversible contraception. Fam Med. 2013;45:701-707.

28. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM. Complications and continuation rates associated with 2 types of long-acting contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:e1-e8.

29. Kavanaugh ML, Frowirth L, Jerman J, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: patient and provider perspectives. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;86:86-95.

30. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

31. Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, et al. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:718-726.

› Suggest long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine devices (IUDs), as a first-line method of contraception to most women, including adolescents and nulliparous women. A

› Offer immediate post-placental insertion of LARC when counseling women who have barriers to seeking contraception at a postpartum visit or are unlikely to return for a postpartum visit. B

› Treat sexually transmitted infections in most cases without removing an IUD that is already in place. Consider removing the IUD, however, if there is no clinical improvement after 2 to 3 days of antibiotics. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The number of women using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in the United States has been increasing, with current use accounting for approximately 18% of reversible contraception, according to the National Survey of Family Growth.1,2 LARC includes any method of contraception that lasts ≥3 years, is easily reversed, and does not rely on the user to maintain efficacy. Five LARC devices are available in the United States: 4 intrauterine devices (IUDs) and one subdermal implant.

The number of women using LARC is surprisingly low, given that it is considered a first-line contraceptive method for most women and adolescents,3 and when compared with other forms of reversible contraception, is more efficacious,4-6 has higher satisfaction rates,7-9 and higher rates of continuation.9 In fact, the Contraceptive CHOICE Project—a St. Louis community-based research program promoting and enabling access to reversible contraceptive methods—has shown that when appropriate counseling is provided and cost barriers are removed, up to 79% of women choose LARC as their preferred method of contraception.10

CASES › Jenny, who is 16 years old, comes to your office with her mother to discuss contraceptive options. She is nulliparous, has regular menses, and, aside from a body mass index (BMI) of 28, has no medical problems. Her mother is concerned about Jenny becoming pregnant while she is still in high school.

Maria D, a 32-year-old G2P1, comes in for a prenatal visit with her husband. She tells you that after delivery she is interested in a long-acting contraceptive, but is planning on breastfeeding and does not want anything to interfere with that.

What LARC options do these and other patients have?

The 4 IUDs and one implant approved for use are all viable options depending on a patient’s preference and comorbidities (TABLE 1).3-9,11-15 The copper IUD is the oldest method of LARC available and the only one that is nonhormonal. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use up to 10 years,11 but studies support its effectiveness for up to 12 years.16

The remaining IUDs (Skyla, Liletta, Mirena) contain varying amounts of the progestin levonorgestrel (LNG), released by each device at a slightly different rate that declines over time. Skyla releases a significantly lower dose of hormone than Liletta or Mirena.12-14 Skyla and Liletta are FDA-approved for up to 3 years of use,12,13 and Liletta is currently undergoing trials to gain approval for use up to 5 years. Mirena is FDA-approved for use up to 5 years,14 but studies have shown that it can be effective for 7 years.4,16

The only implant available in the US is Nexplanon, a plastic rod containing 68 mg of etonorgestrel. It is inserted subdermally and is FDA-approved for use up to 3 years.15

Through systemic hormonal effects, the primary mechanism of action of the implant is prevention of ovulation. Additionally, the implant has been shown to inhibit endometrial proliferation and cervical mucus thickening, both of which may contribute to the implant’s overall effectiveness.17 In contrast, both the copper IUD and the LNG-IUDs work primarily by preventing fertilization. The LNG-IUDs also exhibit local hormonal effects (endometrial atrophy and thickened cervical mucus) that contribute to their effectiveness.17

Who is eligible for LARC?

LARC is suitable for the vast majority of women of reproductive age. For most multiparous women ≥20 years, all LARC devices are classified as category 1 (use without restriction) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC).3 For women <20 years, the implant is also considered category 1, but IUDs in this age group are classified as category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) because of concerns about an increased risk of IUD expulsion and the increased prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in adolescents.3 Contraindications to use of LARC vary depending on the method chosen (TABLE 1).3

There has been concern about the efficacy of implants in overweight women because the original trials of subdermal implants excluded women >130% of ideal body weight. However, according to the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, overweight and obese women enrolled in its program did not experience reduced contraceptive efficacy when using the implant when compared with normal-weight women.18

When can LARC devices be inserted?

LARC device insertion is possible at any time during the menstrual cycle. An algorithm to guide initiation of LARC is available through the Reproductive Health Access Project’s Web site at http://www.reproductiveaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/quickstart_algorithm.pdf.

Rule out pregnancy before placing any LARC device. The copper IUD can be inserted at any time during the menstrual cycle without the need for back-up contraception.11,19 In contrast, for LNG-IUDs, back-up contraception is recommended for 7 days unless the insertion is done during the first 7 days of the menstrual cycle.12-14,19

For the implant, recommendations about when to insert are based on a woman’s previous method of contraception (TABLE 2).15 If insertion is done at a time other than when recommended, advise patients to use barrier protection for 7 days after insertion.4,15,19

Other issues often arise and cause concern about whether and when a LARC device can be inserted, including the possibility of undiagnosed STI, time elapsed since delivery, and advisability of use when breastfeeding.

Sexually transmitted infections and IUDs

Whether or not a woman chooses to receive an IUD, follow routine CDC guidelines in determining if a patient is a candidate for STI screening.20 If a woman wants an IUD and routine screening is recommended, you can perform screening on the day of IUD insertion.4,19 For women with an IUD already in place who are diagnosed with an STI, treat the infection while leaving the IUD in place.19 For women with a known or suspected STI who do not have an IUD already, treat the STI before inserting the IUD. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises postponing insertion of an IUD until a negative STI test result is obtained 3 to 4 weeks after treatment completion.4

Breastfeeding concerns and timing of insertion postpartum

The US MEC classifies insertion of the copper IUD as category 1 for all postpartum women, regardless of breastfeeding status, if placed >4 weeks postpartum or immediately postpartum (defined as within 10 minutes of the delivery of the placenta). IUD placement is category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) if placed ≥10 minutes after placental delivery (until 4 weeks postpartum) because of an increased risk of expulsion.3

The US MEC also considers use of the implant and LNG-IUDs in breastfeeding women as category 1 if the device is placed at ≥4 weeks postpartum. Insertion at <4 weeks postpartum is considered category 2 because of concerns for decreased breast milk supply.3 However, studies on whether progestin-containing LARC devices affect breastfeeding have yielded varying results. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 69 breastfeeding women using the implant, breastfeeding duration and milk production were not dependent on the timing of insertion after delivery.21 Another RCT of 96 women using LNG-IUDs showed fewer women continued to breastfeed at 6 months when their LNG-IUD was inserted immediately postpartum, compared with waiting 6 weeks.22

In addition to a concern about breast milk supply, breastfeeding women have a higher risk for uterine perforation from IUDs, especially during the first 36 weeks after delivery.23

Several studies have shown that there is a lower repeat pregnancy rate among women who receive immediate postpartum LARC placement.24 However, even if IUD insertion is performed immediately postpartum, there is a higher expulsion rate than when the IUD is inserted ≥4 weeks postpartum. The expulsion rates for insertion <10 minutes after vaginal delivery range from 9.5% to 15% for the copper IUD to as high as 24% for the LNG-IUDs. Expulsion rates for all IUDs are slightly lower for cesarean delivery.4,25,26 ACOG supports immediate post-placental placement for women with barriers to postpartum care or limited access to contraception.4

How can I help my patients make an informed choice?

Provide counseling on efficacy, common adverse effects, risks, and complications.

Efficacy is high

The failure rate of LARC is equal to, or lower than, that of female sterilization and is significantly lower than that of oral contraceptives (TABLE 1).4-6 Not only are LARC devices extremely effective, they have a higher rate of satisfaction than any other reversible contraceptive (TABLE 1).7,8

Common adverse effects

The most common adverse effect seen with all LARC devices is an alteration in menstrual bleeding, and a frequent adverse effect with IUDs is pain. Vaginitis is less common and can be seen with any of the devices. The progestin-containing LARC devices are associated with hormonal effects: vaginitis, headache, weight gain, acne, breast pain, hair loss, and emotional lability.12-15

Copper IUD. Many women using the copper IUD experience either a transient increase in menstrual bleeding lasting for a few months or inter-menstrual bleeding that tends to continue for the duration of use.4,17 However, according to data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of the copper IUD is pain and cramping.9

LNG-IUDs. Like the copper IUD, many users of LNG-IUDs experience an initial increase in menstrual bleeding. However, unlike the other LARC devices, 20% to 33% of Mirena users are likely to experience amenorrhea after one year of use and 70% at 2 years.4,14 According to package inserts, amenorrhea after 3 years is less common with both Skyla (12%) and Liletta (38%).12,13 As with the copper IUD, based on data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of LNG-IUDs is pain and cramping.9

Subdermal implant. Changes in menses in women using the subdermal implant range from amenorrhea (22%) to prolonged bleeding (18%).15,17 Although it is difficult to predict which pattern a particular woman will experience, heavier women are more likely to have heavier bleeding patterns, and initial bleeding patterns are predictive of future ones.4 The most common reason women choose to discontinue use of the implant is abnormal bleeding.4,9,27,28

Newer IUDs do not increase risk of STIs

Many patients and clinicians erroneously believe that IUDs increase the risk of STIs and therefore assume that patients with a history of STI are not appropriate candidates for an IUD.29 There is a slightly increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the first 21 days after insertion of an IUD. However, in contrast to older IUDs, currently available IUDs do not increase the general risk for STIs.17,30

Risk of infertility is nil

There is no risk of infertility from use of currently available LARCs. For those who want to become pregnant, fertility typically returns immediately after removal of the device, regardless of which method of LARC is used.11-15,30

Complications of IUD insertion

Uterine perforation. Uterine perforation occurs in 0.8 to 2.1 per 1000 women, usually at the time of IUD placement. If IUD strings are not visible during a speculum examination, locate the IUD with ultrasound.4,17,30 If the IUD is in the abdomen, refer to a gynecologist for laparoscopic removal and select another form of contraception for use in the interim.30

Expulsion. Rates of expulsion are low, occurring in less than 10% of women4,17 and are not affected by parity or BMI.31 Expulsion rates are higher when the IUD is inserted immediately postpartum.4,25,26 Adolescents also have a 2-fold higher risk of uterine expulsion than older women.31

Ectopic pregnancy. Although a woman’s overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is not increased by using an IUD,4 it is true that if a woman becomes pregnant with an IUD in place, the pregnancy is more likely to be ectopic. Thus, if pregnancy is confirmed in a woman with an IUD in place, rule out ectopic pregnancy.

The FDA and the World Health Organization recommend that if an intrauterine pregnancy is confirmed with an IUD in place and the strings are visible, the IUD should be removed.4 Although removing the IUD increases the risk of spontaneous abortion (SAB) as compared with pregnancies without an IUD in place, the risk of SAB is still lower than if the IUD is left in place.4 Additional risks of continuing a pregnancy with an IUD in place include increased risks of preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and septic abortion.4,30

Complications of subdermal implant insertion

After insertion of the implant, women usually experience temporary bruising and soreness at the insertion site. Less than 1% of women develop an infection or hematoma.17 There is a low risk of nerve damage if the implant is inserted too deeply.15 Removal of the subdermal implant is recommended if pregnancy occurs.15

CASE DECISIONS › Jenny has been using oral contraceptive pills, but not regularly. You suggest that LARC may be a better option and counsel her that if she does choose an IUD or the implant, it is likely that her menses will change. You provide information and reassurance that LARC is safe to use in adolescents. Jenny says she would like to try an implant. Six months later, Jenny returns and says the implant is working well. She has some irregular bleeding, but it is not bothersome.

You review with Ms. D the types of LARC devices available and reassure her that all are safe to use once breastfeeding is established. Ms. D says she would like to use an IUD and elects to wait until her postpartum visit to have an IUD inserted. Ms. D returns 6 months after IUD insertion; breastfeeding is going well, and she has not had any menstrual bleeding since delivery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn Kolman, MD, 2800 East Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected]

› Suggest long-acting reversible contraception (LARC), including intrauterine devices (IUDs), as a first-line method of contraception to most women, including adolescents and nulliparous women. A

› Offer immediate post-placental insertion of LARC when counseling women who have barriers to seeking contraception at a postpartum visit or are unlikely to return for a postpartum visit. B

› Treat sexually transmitted infections in most cases without removing an IUD that is already in place. Consider removing the IUD, however, if there is no clinical improvement after 2 to 3 days of antibiotics. A

Strength of recommendation (SOR)

A Good-quality patient-oriented evidence

B Inconsistent or limited-quality patient-oriented evidence

C Consensus, usual practice, opinion, disease-oriented evidence, case series

The number of women using long-acting reversible contraception (LARC) in the United States has been increasing, with current use accounting for approximately 18% of reversible contraception, according to the National Survey of Family Growth.1,2 LARC includes any method of contraception that lasts ≥3 years, is easily reversed, and does not rely on the user to maintain efficacy. Five LARC devices are available in the United States: 4 intrauterine devices (IUDs) and one subdermal implant.

The number of women using LARC is surprisingly low, given that it is considered a first-line contraceptive method for most women and adolescents,3 and when compared with other forms of reversible contraception, is more efficacious,4-6 has higher satisfaction rates,7-9 and higher rates of continuation.9 In fact, the Contraceptive CHOICE Project—a St. Louis community-based research program promoting and enabling access to reversible contraceptive methods—has shown that when appropriate counseling is provided and cost barriers are removed, up to 79% of women choose LARC as their preferred method of contraception.10

CASES › Jenny, who is 16 years old, comes to your office with her mother to discuss contraceptive options. She is nulliparous, has regular menses, and, aside from a body mass index (BMI) of 28, has no medical problems. Her mother is concerned about Jenny becoming pregnant while she is still in high school.

Maria D, a 32-year-old G2P1, comes in for a prenatal visit with her husband. She tells you that after delivery she is interested in a long-acting contraceptive, but is planning on breastfeeding and does not want anything to interfere with that.

What LARC options do these and other patients have?

The 4 IUDs and one implant approved for use are all viable options depending on a patient’s preference and comorbidities (TABLE 1).3-9,11-15 The copper IUD is the oldest method of LARC available and the only one that is nonhormonal. It is approved by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for use up to 10 years,11 but studies support its effectiveness for up to 12 years.16

The remaining IUDs (Skyla, Liletta, Mirena) contain varying amounts of the progestin levonorgestrel (LNG), released by each device at a slightly different rate that declines over time. Skyla releases a significantly lower dose of hormone than Liletta or Mirena.12-14 Skyla and Liletta are FDA-approved for up to 3 years of use,12,13 and Liletta is currently undergoing trials to gain approval for use up to 5 years. Mirena is FDA-approved for use up to 5 years,14 but studies have shown that it can be effective for 7 years.4,16

The only implant available in the US is Nexplanon, a plastic rod containing 68 mg of etonorgestrel. It is inserted subdermally and is FDA-approved for use up to 3 years.15

Through systemic hormonal effects, the primary mechanism of action of the implant is prevention of ovulation. Additionally, the implant has been shown to inhibit endometrial proliferation and cervical mucus thickening, both of which may contribute to the implant’s overall effectiveness.17 In contrast, both the copper IUD and the LNG-IUDs work primarily by preventing fertilization. The LNG-IUDs also exhibit local hormonal effects (endometrial atrophy and thickened cervical mucus) that contribute to their effectiveness.17

Who is eligible for LARC?

LARC is suitable for the vast majority of women of reproductive age. For most multiparous women ≥20 years, all LARC devices are classified as category 1 (use without restriction) in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) US Medical Eligibility Criteria (US MEC).3 For women <20 years, the implant is also considered category 1, but IUDs in this age group are classified as category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) because of concerns about an increased risk of IUD expulsion and the increased prevalence of sexually transmitted infections (STIs) in adolescents.3 Contraindications to use of LARC vary depending on the method chosen (TABLE 1).3

There has been concern about the efficacy of implants in overweight women because the original trials of subdermal implants excluded women >130% of ideal body weight. However, according to the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, overweight and obese women enrolled in its program did not experience reduced contraceptive efficacy when using the implant when compared with normal-weight women.18

When can LARC devices be inserted?

LARC device insertion is possible at any time during the menstrual cycle. An algorithm to guide initiation of LARC is available through the Reproductive Health Access Project’s Web site at http://www.reproductiveaccess.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/quickstart_algorithm.pdf.

Rule out pregnancy before placing any LARC device. The copper IUD can be inserted at any time during the menstrual cycle without the need for back-up contraception.11,19 In contrast, for LNG-IUDs, back-up contraception is recommended for 7 days unless the insertion is done during the first 7 days of the menstrual cycle.12-14,19

For the implant, recommendations about when to insert are based on a woman’s previous method of contraception (TABLE 2).15 If insertion is done at a time other than when recommended, advise patients to use barrier protection for 7 days after insertion.4,15,19

Other issues often arise and cause concern about whether and when a LARC device can be inserted, including the possibility of undiagnosed STI, time elapsed since delivery, and advisability of use when breastfeeding.

Sexually transmitted infections and IUDs

Whether or not a woman chooses to receive an IUD, follow routine CDC guidelines in determining if a patient is a candidate for STI screening.20 If a woman wants an IUD and routine screening is recommended, you can perform screening on the day of IUD insertion.4,19 For women with an IUD already in place who are diagnosed with an STI, treat the infection while leaving the IUD in place.19 For women with a known or suspected STI who do not have an IUD already, treat the STI before inserting the IUD. The American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) advises postponing insertion of an IUD until a negative STI test result is obtained 3 to 4 weeks after treatment completion.4

Breastfeeding concerns and timing of insertion postpartum

The US MEC classifies insertion of the copper IUD as category 1 for all postpartum women, regardless of breastfeeding status, if placed >4 weeks postpartum or immediately postpartum (defined as within 10 minutes of the delivery of the placenta). IUD placement is category 2 (recommended with the caution that advantages usually outweigh risks) if placed ≥10 minutes after placental delivery (until 4 weeks postpartum) because of an increased risk of expulsion.3

The US MEC also considers use of the implant and LNG-IUDs in breastfeeding women as category 1 if the device is placed at ≥4 weeks postpartum. Insertion at <4 weeks postpartum is considered category 2 because of concerns for decreased breast milk supply.3 However, studies on whether progestin-containing LARC devices affect breastfeeding have yielded varying results. In one randomized controlled trial (RCT) of 69 breastfeeding women using the implant, breastfeeding duration and milk production were not dependent on the timing of insertion after delivery.21 Another RCT of 96 women using LNG-IUDs showed fewer women continued to breastfeed at 6 months when their LNG-IUD was inserted immediately postpartum, compared with waiting 6 weeks.22

In addition to a concern about breast milk supply, breastfeeding women have a higher risk for uterine perforation from IUDs, especially during the first 36 weeks after delivery.23

Several studies have shown that there is a lower repeat pregnancy rate among women who receive immediate postpartum LARC placement.24 However, even if IUD insertion is performed immediately postpartum, there is a higher expulsion rate than when the IUD is inserted ≥4 weeks postpartum. The expulsion rates for insertion <10 minutes after vaginal delivery range from 9.5% to 15% for the copper IUD to as high as 24% for the LNG-IUDs. Expulsion rates for all IUDs are slightly lower for cesarean delivery.4,25,26 ACOG supports immediate post-placental placement for women with barriers to postpartum care or limited access to contraception.4

How can I help my patients make an informed choice?

Provide counseling on efficacy, common adverse effects, risks, and complications.

Efficacy is high

The failure rate of LARC is equal to, or lower than, that of female sterilization and is significantly lower than that of oral contraceptives (TABLE 1).4-6 Not only are LARC devices extremely effective, they have a higher rate of satisfaction than any other reversible contraceptive (TABLE 1).7,8

Common adverse effects

The most common adverse effect seen with all LARC devices is an alteration in menstrual bleeding, and a frequent adverse effect with IUDs is pain. Vaginitis is less common and can be seen with any of the devices. The progestin-containing LARC devices are associated with hormonal effects: vaginitis, headache, weight gain, acne, breast pain, hair loss, and emotional lability.12-15

Copper IUD. Many women using the copper IUD experience either a transient increase in menstrual bleeding lasting for a few months or inter-menstrual bleeding that tends to continue for the duration of use.4,17 However, according to data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of the copper IUD is pain and cramping.9

LNG-IUDs. Like the copper IUD, many users of LNG-IUDs experience an initial increase in menstrual bleeding. However, unlike the other LARC devices, 20% to 33% of Mirena users are likely to experience amenorrhea after one year of use and 70% at 2 years.4,14 According to package inserts, amenorrhea after 3 years is less common with both Skyla (12%) and Liletta (38%).12,13 As with the copper IUD, based on data from the Contraceptive CHOICE Project, the most common reason cited for early discontinuation of LNG-IUDs is pain and cramping.9

Subdermal implant. Changes in menses in women using the subdermal implant range from amenorrhea (22%) to prolonged bleeding (18%).15,17 Although it is difficult to predict which pattern a particular woman will experience, heavier women are more likely to have heavier bleeding patterns, and initial bleeding patterns are predictive of future ones.4 The most common reason women choose to discontinue use of the implant is abnormal bleeding.4,9,27,28

Newer IUDs do not increase risk of STIs

Many patients and clinicians erroneously believe that IUDs increase the risk of STIs and therefore assume that patients with a history of STI are not appropriate candidates for an IUD.29 There is a slightly increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease (PID) in the first 21 days after insertion of an IUD. However, in contrast to older IUDs, currently available IUDs do not increase the general risk for STIs.17,30

Risk of infertility is nil

There is no risk of infertility from use of currently available LARCs. For those who want to become pregnant, fertility typically returns immediately after removal of the device, regardless of which method of LARC is used.11-15,30

Complications of IUD insertion

Uterine perforation. Uterine perforation occurs in 0.8 to 2.1 per 1000 women, usually at the time of IUD placement. If IUD strings are not visible during a speculum examination, locate the IUD with ultrasound.4,17,30 If the IUD is in the abdomen, refer to a gynecologist for laparoscopic removal and select another form of contraception for use in the interim.30

Expulsion. Rates of expulsion are low, occurring in less than 10% of women4,17 and are not affected by parity or BMI.31 Expulsion rates are higher when the IUD is inserted immediately postpartum.4,25,26 Adolescents also have a 2-fold higher risk of uterine expulsion than older women.31

Ectopic pregnancy. Although a woman’s overall risk of ectopic pregnancy is not increased by using an IUD,4 it is true that if a woman becomes pregnant with an IUD in place, the pregnancy is more likely to be ectopic. Thus, if pregnancy is confirmed in a woman with an IUD in place, rule out ectopic pregnancy.

The FDA and the World Health Organization recommend that if an intrauterine pregnancy is confirmed with an IUD in place and the strings are visible, the IUD should be removed.4 Although removing the IUD increases the risk of spontaneous abortion (SAB) as compared with pregnancies without an IUD in place, the risk of SAB is still lower than if the IUD is left in place.4 Additional risks of continuing a pregnancy with an IUD in place include increased risks of preterm labor, chorioamnionitis, and septic abortion.4,30

Complications of subdermal implant insertion

After insertion of the implant, women usually experience temporary bruising and soreness at the insertion site. Less than 1% of women develop an infection or hematoma.17 There is a low risk of nerve damage if the implant is inserted too deeply.15 Removal of the subdermal implant is recommended if pregnancy occurs.15

CASE DECISIONS › Jenny has been using oral contraceptive pills, but not regularly. You suggest that LARC may be a better option and counsel her that if she does choose an IUD or the implant, it is likely that her menses will change. You provide information and reassurance that LARC is safe to use in adolescents. Jenny says she would like to try an implant. Six months later, Jenny returns and says the implant is working well. She has some irregular bleeding, but it is not bothersome.

You review with Ms. D the types of LARC devices available and reassure her that all are safe to use once breastfeeding is established. Ms. D says she would like to use an IUD and elects to wait until her postpartum visit to have an IUD inserted. Ms. D returns 6 months after IUD insertion; breastfeeding is going well, and she has not had any menstrual bleeding since delivery.

CORRESPONDENCE

Karyn Kolman, MD, 2800 East Ajo Way, Room 3006, Tucson, AZ 85713; [email protected]

1. Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-44: United States 2011-2013. NCHS data brief, no. 173. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014.

2. Branum AM, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among US women aged 15-44. NCHS data brief, no. 188. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:184-196.

5. Pickle S, Wu J, Burbank-Schmitt E. Prevention of unintended pregnancy: a focus on long-acting reversible contraception. Prim Care. 2014;41:239-260.

6. Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998-2007.

7. Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

8. O’Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1083-1091.

9. Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, et al. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

10. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

11. ParaGard T 380A. (intrauterine copper contraceptive) [package insert]. Sellersville, PA : Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 2013.

12. Skyla (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Wayne, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2013.

13. Liletta (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ : Actavis Pharma, Inc., 2015.

14. Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Whippany, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2014.

15. Nexplanon (etongestrel implant) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co Inc.; 2014.

16. Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89:495-503.

17. Stoddard A, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Efficacy and safety of long-acting reversible contraception. Drugs. 2011;71:969-980.

18. Xu H, Wade JA, Peipert JF, et al. Contraceptive failure rates of etonogestrel subdermal implants in overweight and obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:21-26.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-60.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-110.

21. Gurtcheff SE, Turok DK, Stoddard G, et al. Lactogenesis after early postpartum use of the contraceptive implant: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1114-1121.

22. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504.

23. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

24. Tocce K, Sheeder J, Python J, et al. Long acting reversible contraception in postpartum adolescents: early initiation of etonogestrel implant is superior to IUDs in the outpatient setting. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:59-63.

25. Mwalwanda CS, Black KI. Immediate post-partum initiation of intrauterine contraception and implants: a review of the safety and guidelines for use. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:331-337.

26. Sober, S, Schreiber CA. Postpartum contraception. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:763-776.

27. Dickerson LM, Diaz VA, Jordon J, et al. Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long-acting reversible contraception. Fam Med. 2013;45:701-707.

28. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM. Complications and continuation rates associated with 2 types of long-acting contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:e1-e8.

29. Kavanaugh ML, Frowirth L, Jerman J, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: patient and provider perspectives. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;86:86-95.

30. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

31. Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, et al. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:718-726.

1. Daniels K, Daugherty J, Jones J. Current contraceptive status among women aged 15-44: United States 2011-2013. NCHS data brief, no. 173. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2014.

2. Branum AM, Jones J. Trends in long-acting reversible contraception use among US women aged 15-44. NCHS data brief, no. 188. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics, 2015.

3. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US medical eligibility criteria for contraceptive use, 2010. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-86.

4. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 121: Long-acting reversible contraception: Implants and intrauterine devices. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;118:184-196.

5. Pickle S, Wu J, Burbank-Schmitt E. Prevention of unintended pregnancy: a focus on long-acting reversible contraception. Prim Care. 2014;41:239-260.

6. Winner B, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Effectiveness of long-acting reversible contraception. N Engl J Med. 2012;366:1998-2007.

7. Peipert JF, Zhao Q, Allsworth JE, et al. Continuation and satisfaction of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1105-1113.

8. O’Neil-Callahan M, Peipert JF, Zhao Q, et al. Twenty-four-month continuation of reversible contraception. Obstet Gynecol. 2013;122:1083-1091.

9. Grunloh DS, Casner T, Secura GM, et al. Characteristics associated with discontinuation of long-acting reversible contraception within the first 6 months of use. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

10. Birgisson NE, Zhao Q, Secura GM, et al. Preventing unintended pregnancy: the contraceptive CHOICE project in review. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24:349-353.

11. ParaGard T 380A. (intrauterine copper contraceptive) [package insert]. Sellersville, PA : Teva Pharmaceuticals USA, Inc., 2013.

12. Skyla (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Wayne, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2013.

13. Liletta (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Parsippany, NJ : Actavis Pharma, Inc., 2015.

14. Mirena (levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system) [package insert]. Whippany, NJ : Bayer HealthCare Pharmaceuticals, Inc., 2014.

15. Nexplanon (etongestrel implant) [package insert]. Whitehouse Station, NJ: Merck & Co Inc.; 2014.

16. Wu JP, Pickle S. Extended use of the intrauterine device: a literature review and recommendations for clinical practice. Contraception. 2014;89:495-503.

17. Stoddard A, McNicholas C, Peipert JF. Efficacy and safety of long-acting reversible contraception. Drugs. 2011;71:969-980.

18. Xu H, Wade JA, Peipert JF, et al. Contraceptive failure rates of etonogestrel subdermal implants in overweight and obese women. Obstet Gynecol. 2012;120:21-26.

19. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). US selected practice recommendations for contraceptive use. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2013;62:1-60.

20. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). Sexually transmitted disease treatment guidelines. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2010;59:1-110.

21. Gurtcheff SE, Turok DK, Stoddard G, et al. Lactogenesis after early postpartum use of the contraceptive implant: a randomized controlled trial. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:1114-1121.

22. Chen BA, Reeves MF, Creinin MD, et al. Postplacental or delayed levonorgestrel intrauterine device insertion and breast-feeding duration. Contraception. 2011;84:499-504.

23. Heinemann K, Reed S, Moehner S, et al. Risk of uterine perforation with levonorgestrel-releasing and copper intrauterine devices in the European Active Surveillance Study on Intrauterine Devices. Contraception. 2015;91:274-279.

24. Tocce K, Sheeder J, Python J, et al. Long acting reversible contraception in postpartum adolescents: early initiation of etonogestrel implant is superior to IUDs in the outpatient setting. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2012;25:59-63.

25. Mwalwanda CS, Black KI. Immediate post-partum initiation of intrauterine contraception and implants: a review of the safety and guidelines for use. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2013;53:331-337.

26. Sober, S, Schreiber CA. Postpartum contraception. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2014;57:763-776.

27. Dickerson LM, Diaz VA, Jordon J, et al. Satisfaction, early removal, and side effects associated with long-acting reversible contraception. Fam Med. 2013;45:701-707.

28. Berenson AB, Tan A, Hirth JM. Complications and continuation rates associated with 2 types of long-acting contraception. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2015;212:e1-e8.

29. Kavanaugh ML, Frowirth L, Jerman J, et al. Long-acting reversible contraception for adolescents and young adults: patient and provider perspectives. J Pediatr Adolesc Gynecol. 2013;86:86-95.

30. Espey E, Ogburn T. Long-acting reversible contraceptives: intrauterine devices and the contraceptive implant. Obstet Gynecol. 2011;117:705-719.

31. Madden T, McNicholas C, Zhao Q, et al. Association of age and parity with intrauterine device expulsion. Obstet Gynecol. 2014;124:718-726.

Treating pain in a patient with addiction

Delayed cancer diagnosis tied to care dissatisfaction

Photo courtesy of NIH

Patients who make 3 or more trips to the general practitioner (GP) before they are referred for cancer tests are more likely to be dissatisfied with subsequent care, according to research published in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

Researchers analyzed survey responses from nearly 60,000 cancer patients and found that about 23% had visited their GP 3 or more times before they were referred for cancer tests.

These patients were more likely than patients with 1 or 2 GP visits to report negative experiences with regard to many different aspects of their care.

“This research shows that first impressions go a long way in determining how cancer patients view their experience of cancer treatment,” said study author Georgios Lyratzopoulos, MD, of University College London in the UK.

“A negative experience of diagnosis can trigger loss of confidence in their care throughout the cancer journey. When they occur, diagnostic delays are largely due to cancer symptoms being extremely hard to distinguish from other diseases, combined with a lack of accurate and easy-to-use tests. New diagnostic tools to help doctors decide which patients need referring are vital to improve the care experience for even more cancer patients.”

Dr Lyratzopoulos and his colleagues initially analyzed survey data from 73,462 cancer patients, but 15,355 of those patients (21%) had not seen a GP prior to their cancer diagnosis.

Of the 58,107 patients who had at least 1 primary care consultation, 44,827 (77%) had seen their GP once or twice before referral for cancer tests, and 13,280 (23%) had seen the GP 3 or more times.

The researchers analyzed patients’ responses to 12 survey questions that assessed satisfaction with various aspects of their cancer care.

And results showed that patients who had seen their GP 3 or more times before referral were significantly more likely than patients with 1 to 2 GP visits to report negative experiences across 10 of the 12 aspects of care.

The 12 aspects of care and patient responses (for 3+ GP visits and 1-2 visits, respectively) were as follows:

- Dissatisfied with overall care: 16% vs 9% (adjusted* odds ratio [aOR]=1.44, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the way they were informed of their cancer: 22% vs 14% (aOR=1.38, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with their involvement in decision-making: 32% vs 25% (aOR=1.13, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their doctors: 19% vs 12% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their nurses: 36% vs 27% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Thought doctors/nurses deliberately withheld information: 16% vs 10% (aOR=1.27, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with staff support: 41% vs 27% (aOR=1.68, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with integration of various caregivers (GP, hospital doctors/nurses, specialist nurses, etc): 45% vs 32% (aOR=1.48, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the amount of time they had to wait at appointments with their hospital doctor: 31% vs 28% (aOR=1.10, P=0.007)

- Said their GP did not receive enough information about their condition or hospital treatment: 8% vs 5% (aOR=1.36, P<0.001)

- Said they did not receive clear written information about what they should or should not do after leaving the hospital: 20% vs 14% (aOR=1.06, P=0.100)

- Said they did not receive the name of a Clinical Nurse Specialist who would be in charge of their care: 11% vs 9% (aOR=1.00, P=0.894).

“This is the first time we’ve had direct feedback from patients on such a large scale to show how the timeliness of their diagnosis colors their experience of the care they later receive,” said Sara Hiom, of Cancer Research UK, which supported this study.

“It’s another good reason to highlight the importance of diagnosing cancer as quickly as possible, not just to give patients the best chances of survival, but also to improve their experience of the care they receive throughout their cancer journey.” ![]()

*The odds ratio was adjusted for patient age, sex, ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, and response tendency (likelihood of giving a positive or negative response to questions).

Photo courtesy of NIH

Patients who make 3 or more trips to the general practitioner (GP) before they are referred for cancer tests are more likely to be dissatisfied with subsequent care, according to research published in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

Researchers analyzed survey responses from nearly 60,000 cancer patients and found that about 23% had visited their GP 3 or more times before they were referred for cancer tests.

These patients were more likely than patients with 1 or 2 GP visits to report negative experiences with regard to many different aspects of their care.

“This research shows that first impressions go a long way in determining how cancer patients view their experience of cancer treatment,” said study author Georgios Lyratzopoulos, MD, of University College London in the UK.

“A negative experience of diagnosis can trigger loss of confidence in their care throughout the cancer journey. When they occur, diagnostic delays are largely due to cancer symptoms being extremely hard to distinguish from other diseases, combined with a lack of accurate and easy-to-use tests. New diagnostic tools to help doctors decide which patients need referring are vital to improve the care experience for even more cancer patients.”

Dr Lyratzopoulos and his colleagues initially analyzed survey data from 73,462 cancer patients, but 15,355 of those patients (21%) had not seen a GP prior to their cancer diagnosis.

Of the 58,107 patients who had at least 1 primary care consultation, 44,827 (77%) had seen their GP once or twice before referral for cancer tests, and 13,280 (23%) had seen the GP 3 or more times.

The researchers analyzed patients’ responses to 12 survey questions that assessed satisfaction with various aspects of their cancer care.

And results showed that patients who had seen their GP 3 or more times before referral were significantly more likely than patients with 1 to 2 GP visits to report negative experiences across 10 of the 12 aspects of care.

The 12 aspects of care and patient responses (for 3+ GP visits and 1-2 visits, respectively) were as follows:

- Dissatisfied with overall care: 16% vs 9% (adjusted* odds ratio [aOR]=1.44, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the way they were informed of their cancer: 22% vs 14% (aOR=1.38, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with their involvement in decision-making: 32% vs 25% (aOR=1.13, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their doctors: 19% vs 12% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their nurses: 36% vs 27% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Thought doctors/nurses deliberately withheld information: 16% vs 10% (aOR=1.27, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with staff support: 41% vs 27% (aOR=1.68, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with integration of various caregivers (GP, hospital doctors/nurses, specialist nurses, etc): 45% vs 32% (aOR=1.48, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the amount of time they had to wait at appointments with their hospital doctor: 31% vs 28% (aOR=1.10, P=0.007)

- Said their GP did not receive enough information about their condition or hospital treatment: 8% vs 5% (aOR=1.36, P<0.001)

- Said they did not receive clear written information about what they should or should not do after leaving the hospital: 20% vs 14% (aOR=1.06, P=0.100)

- Said they did not receive the name of a Clinical Nurse Specialist who would be in charge of their care: 11% vs 9% (aOR=1.00, P=0.894).

“This is the first time we’ve had direct feedback from patients on such a large scale to show how the timeliness of their diagnosis colors their experience of the care they later receive,” said Sara Hiom, of Cancer Research UK, which supported this study.

“It’s another good reason to highlight the importance of diagnosing cancer as quickly as possible, not just to give patients the best chances of survival, but also to improve their experience of the care they receive throughout their cancer journey.” ![]()

*The odds ratio was adjusted for patient age, sex, ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, and response tendency (likelihood of giving a positive or negative response to questions).

Photo courtesy of NIH

Patients who make 3 or more trips to the general practitioner (GP) before they are referred for cancer tests are more likely to be dissatisfied with subsequent care, according to research published in the European Journal of Cancer Care.

Researchers analyzed survey responses from nearly 60,000 cancer patients and found that about 23% had visited their GP 3 or more times before they were referred for cancer tests.

These patients were more likely than patients with 1 or 2 GP visits to report negative experiences with regard to many different aspects of their care.

“This research shows that first impressions go a long way in determining how cancer patients view their experience of cancer treatment,” said study author Georgios Lyratzopoulos, MD, of University College London in the UK.

“A negative experience of diagnosis can trigger loss of confidence in their care throughout the cancer journey. When they occur, diagnostic delays are largely due to cancer symptoms being extremely hard to distinguish from other diseases, combined with a lack of accurate and easy-to-use tests. New diagnostic tools to help doctors decide which patients need referring are vital to improve the care experience for even more cancer patients.”

Dr Lyratzopoulos and his colleagues initially analyzed survey data from 73,462 cancer patients, but 15,355 of those patients (21%) had not seen a GP prior to their cancer diagnosis.

Of the 58,107 patients who had at least 1 primary care consultation, 44,827 (77%) had seen their GP once or twice before referral for cancer tests, and 13,280 (23%) had seen the GP 3 or more times.

The researchers analyzed patients’ responses to 12 survey questions that assessed satisfaction with various aspects of their cancer care.

And results showed that patients who had seen their GP 3 or more times before referral were significantly more likely than patients with 1 to 2 GP visits to report negative experiences across 10 of the 12 aspects of care.

The 12 aspects of care and patient responses (for 3+ GP visits and 1-2 visits, respectively) were as follows:

- Dissatisfied with overall care: 16% vs 9% (adjusted* odds ratio [aOR]=1.44, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the way they were informed of their cancer: 22% vs 14% (aOR=1.38, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with their involvement in decision-making: 32% vs 25% (aOR=1.13, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their doctors: 19% vs 12% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Lack of confidence/trust in their nurses: 36% vs 27% (aOR=1.22, P<0.001)

- Thought doctors/nurses deliberately withheld information: 16% vs 10% (aOR=1.27, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with staff support: 41% vs 27% (aOR=1.68, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with integration of various caregivers (GP, hospital doctors/nurses, specialist nurses, etc): 45% vs 32% (aOR=1.48, P<0.001)

- Dissatisfied with the amount of time they had to wait at appointments with their hospital doctor: 31% vs 28% (aOR=1.10, P=0.007)

- Said their GP did not receive enough information about their condition or hospital treatment: 8% vs 5% (aOR=1.36, P<0.001)

- Said they did not receive clear written information about what they should or should not do after leaving the hospital: 20% vs 14% (aOR=1.06, P=0.100)

- Said they did not receive the name of a Clinical Nurse Specialist who would be in charge of their care: 11% vs 9% (aOR=1.00, P=0.894).

“This is the first time we’ve had direct feedback from patients on such a large scale to show how the timeliness of their diagnosis colors their experience of the care they later receive,” said Sara Hiom, of Cancer Research UK, which supported this study.

“It’s another good reason to highlight the importance of diagnosing cancer as quickly as possible, not just to give patients the best chances of survival, but also to improve their experience of the care they receive throughout their cancer journey.” ![]()

*The odds ratio was adjusted for patient age, sex, ethnicity, cancer diagnosis, and response tendency (likelihood of giving a positive or negative response to questions).

Pentoxifylline beat placebo in acute pancreatitis trial

Patients with acute pancreatitis who received pentoxifylline had fewer ICU admissions and shorter ICU and hospital stays than placebo-treated controls, according to a small, randomized double-blind trial reported in Gastroenterology.

“We showed that a single-institution drug trial for acute pancreatitis is feasible and that pentoxifylline is safe, cheap, and might have efficacy,” wrote Dr. Santhi Vege and his associates at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “This sets the stage for a larger trial of this drug in all patients with acute pancreatitis, to realize the goal of finding an effective drug that can be given within 24 hours of diagnosis in any setting.”