User login

Is There a Link Between Diabetes and Bone Health?

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Diabetes can pose serious complications to bone health. “Clinical trials have revealed a startling elevation in fracture risk in diabetic patients,” says Liyun Wang, PhD, Associate Professor of Mechanical Engineering at the University of Delaware in Newark, Delaware. “Bone fractures can be life threatening — nearly 1 in 6 hip fracture patients dies within a year of injury.”

Because physical exercise is proven to improve bone properties and reduce fracture risk in non-diabetic people, Dr. Wang and colleagues tested its efficacy in type 1 diabetes. Their findings were published online ahead of print July 13 in Bone.

The researchers hypothesized that diabetic bone’s response to anabolic mechanical loading would be attenuated, partially due to impaired mechanosensing of osteocytes under hyperglycemia. For their study, heterozygous male and female diabetic mice and their age- and gender-matched wild-type controls were subjected to unilateral axial ulnar loading with a peak strain of 3500 με at 2 Hz and 3 minutes per day for 5 days.

Overall, the study demonstrated that exercise-induced bone formation was maintained in mildly diabetic mice at a similar level as non-diabetic controls, while the positive effects of exercise were nearly abolished in severely diabetic mice. At the cellular level, the researchers found that hyperglycemia reduced the sensitivity of osteocytes to mechanical stimulation and suppressed osteocytes’ secretion of proteins and signaling molecules that help build stronger bone.

“Our work demonstrates that diabetic bone can respond to exercise when the hyperglycemia is not severe, which suggests that mechanical interventions may be useful to improve bone health and reduce fracture risk in mildly affected diabetic patients,” said Dr. Wang. These results, along with previous findings showing adverse effects of hyperglycemia on osteoblasts and mesenchymal stem cells, suggest that failure to maintain normal glucose levels may impair bone’s responses to mechanical loading in diabetics.

To translate the findings of the study to patient care, Ms. Wang’s team has begun to collaborate with M. James Lenhard, MD, Director of the Center for Diabetes and Metabolic Diseases at Christiana Care Health System in Wilmington, Delaware.

“The plan for collaboration between the University of Delaware and Christiana Care is to evaluate these research findings in humans and expand the research to include other complications of diabetes, such as cardiovascular disease.

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Suggested Reading

Parajuli A, Liu C, Wen L, et al. Bone’s responses to mechanical loading are impaired in type 1 diabetes. Bone. 2015 July 13 [Epub ahead of print].

Generalized, well-dispersed rash • wheal development after tactile irritation • normal vital signs • Dx?

THE CASE

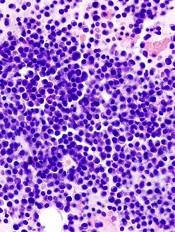

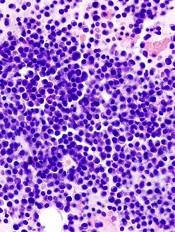

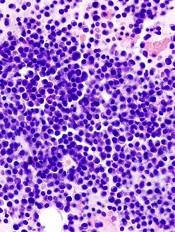

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

1. Lain EL, Hsu S. Photo quiz. Chronic, papular rash that develops a wheal when rubbed. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1493-1494.

2. Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York: Springer. 2012;47.

3. Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S-38S; discussion 38S-39S.

4. Caplan RM. Urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. JAMA. 1965;194:1077-1080.

5. Kiszewski AE, Durán-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285-290.

6. Alto WA, Clarcq L. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of mastocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3047-3054, 3059-3060.

7. Borenstein DG, Wiesel SW, Boden SD, eds. Low Back and Neck Pain: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2004.

8. Vigorita VJ. Metabolic bone disease: Part II. In: Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B, Mintz D, eds. Orthopaedic Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;197.

9. Rosenbaum RC, Frieri M, Metcalfe DD. Patterns of skeletal scintigraphy and their relationship to plasma and urinary histamine levels in systemic mastocytosis. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:859-864.

10. Islas AA, Penaranda E. Generalized brownish macules in infancy. Urticaria pigmentosa. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:987.

11. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

12. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 3:22-31.

THE CASE

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

THE CASE

A 3-year-old girl was brought to our clinic with a generalized rash over her scalp, face, neck, chest, abdomen, back, perianal area, extremities, and the plantar surface of her right foot. On physical examination, we noted many round, hyperpigmented, brown and reddish pink, well-circumscribed macules on her body (FIGURE). Only a few of these macules had appeared on the girl’s trunk within the first 3 months of her life, but since then they’d increased in number and spread to other parts of her body as she’d aged. The lesions became edematous and erythematous with tactile irritation. Darier’s sign (the development of a hive or wheal when a lesion is stroked) was present.

The patient’s vitals at the time of examination included a temperature of 98.2°F, respiratory rate of 17 breaths/min, heart rate of 92 beats/min, blood pressure of 100/66 mm Hg, and oxygen saturation level of 100% on room air. The girl’s parents said they hadn’t traveled. There was no mucosal involvement and no systemic involvement. The patient had no past surgical or medical history, was not taking any medications, and had no significant birth history. A skin biopsy was performed.

THE DIAGNOSIS

Based on the presence of a positive Darier’s sign and the results of the skin biopsy (which showed increased mast cells), we diagnosed urticaria pigmentosa (UP), which is the most common form of cutaneous mastocytosis.1

The diagnosis had been delayed for almost 3 years because of several factors. For one thing, there had been few lesions present early in the child’s life, and as a result, the parents chalked them up to “beauty marks.” Then, as the lesions started to increase in number, the parents thought bed bugs were to blame.

As time went on, the parents attempted to treat their daughter’s hives with homeopathic remedies suggested by family members. When the lesions didn’t resolve with homeopathic remedies, the parents tried over-the-counter H1 and H2 antihistamines such as diphenhydramine, loratadine, and ranitidine. When these treatments failed, the parents brought their child to our office for medical evaluation.

DISCUSSION

UP is a chronic skin disorder in which there is an abnormal proliferation of mast cells in the dermis of the skin. It is considered an orphan disease.1 UP that presents in children is most often benign. Approximately 50% of cases occur before 6 months of age and 25% occur before puberty.2 The lesions are often self-limited and completely resolve in approximately 50% of patients by puberty.3 By adulthood, the lesions either resolve or some lightly colored non-urticating macules remain; however, some patients will continue to have a positive Darier’s sign.4

Dermatologic symptoms. A patient with UP may present with brown or reddish maculopapules, papules, nodules, pruritus, and flushing of the face. Darier’s sign is usually seen in cases of UP; in a study of mastocytosis in children, Darier’s sign was present in 94% of cases.5 Lesions are more prominent in areas where clothes can rub the skin, and they often vary in size and appearance. The presence of lesions can vary from localized and scant to hundreds located over the entire body. UP can be difficult to identify when the lesions are limited, which can lead to delayed diagnosis and treatment.6

Systemic involvement. UP also can affect the skeleton, bone marrow, liver, spleen, lymph nodes, gastrointestinal tract, kidneys, cardiovascular system, and/or central nervous system. Skeletal involvement may manifest as osteoporosis or bone pain in 10% to 20% of patients with UP.7 Bone marrow involvement may progress to anemia or mast cell leukemia. UP can result in hepatomegaly or enlarged lymph nodes. Patients may experience nausea, diarrhea, or abdominal pain if the gastrointestinal tract is affected. Cardiovascular involvement may manifest as tachycardia and shock.8

Diagnosis of UP is made based on the physical exam findings noted earlier, as well as skin biopsy laboratory results. Skin biopsy will reveal increased mast cells. In up to two-thirds of patients who have systemic involvement, laboratory testing will show elevated urine histamine levels, as well as elevated serum concentrations of tryptase.9

UP can appear similar to many other skin conditions

The differential diagnosis of UP can include urticaria, atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, pityriasis rosea, an allergic reaction/drug eruption, Henoch-Schonlein purpura, erythema multiforme, fifth disease, folliculitis, guttate psoriasis, miliaria rubra, insect bites, viral exanthem, lichen planus, and scabies.10,11 In addition to the clinical appearance of the rash, these conditions can be distinguished from UP by skin biopsy and other relevant tests, as well as a thorough history.

Treatment options include antihistamines, corticosteroids, PUVA

Patients with UP should be instructed to avoid precipitating factors such as temperature changes, friction, alcohol ingestion, aspirin, physical exertion, or opiates. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA (psoralen plus ultraviolet A photochemotherapy).3 PUVA is normally avoided in pediatric patients because it is associated with an increased risk of skin cancer later in life.12

Our patient. We prescribed a topical corticosteroid, 0.05% betamethasone dipropionate cream, and oral cromolyn sodium 100 mg qid for our patient, but this failed to significantly improve the macules. The patient and parents grew increasingly anxious. Ultimately, the parents decided to have their daughter treated with PUVA in limited amounts. Topical psoralen was also used. After 2 months of treatment, the patient’s lesions substantially improved and many of them disappeared. In addition, the parents were educated on the importance of sunscreen and limiting their daughter’s exposure to the sun, when possible.

THE TAKEAWAY

UP can be diagnosed by taking a thorough history and conducting a physical examination; a skin biopsy that reveals increased mast cells will confirm the diagnosis. UP is usually self-limited and resolves in about one-half of patients by puberty. Treatment options include H1 and H2 antihistamines, cromolyn sodium, topical corticosteroids, and PUVA. Patients should be referred to a specialist if their symptoms become severe, systemic UP is suspected, or they do not respond to therapy.

1. Lain EL, Hsu S. Photo quiz. Chronic, papular rash that develops a wheal when rubbed. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1493-1494.

2. Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York: Springer. 2012;47.

3. Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S-38S; discussion 38S-39S.

4. Caplan RM. Urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. JAMA. 1965;194:1077-1080.

5. Kiszewski AE, Durán-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285-290.

6. Alto WA, Clarcq L. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of mastocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3047-3054, 3059-3060.

7. Borenstein DG, Wiesel SW, Boden SD, eds. Low Back and Neck Pain: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2004.

8. Vigorita VJ. Metabolic bone disease: Part II. In: Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B, Mintz D, eds. Orthopaedic Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;197.

9. Rosenbaum RC, Frieri M, Metcalfe DD. Patterns of skeletal scintigraphy and their relationship to plasma and urinary histamine levels in systemic mastocytosis. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:859-864.

10. Islas AA, Penaranda E. Generalized brownish macules in infancy. Urticaria pigmentosa. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:987.

11. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

12. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 3:22-31.

1. Lain EL, Hsu S. Photo quiz. Chronic, papular rash that develops a wheal when rubbed. Am Fam Physician. 2004;69:1493-1494.

2. Jain S. Dermatology: Illustrated Study Guide and Comprehensive Board Review. New York: Springer. 2012;47.

3. Soter NA. The skin in mastocytosis. J Invest Dermatol. 1991;96:32S-38S; discussion 38S-39S.

4. Caplan RM. Urticaria pigmentosa and systemic mastocytosis. JAMA. 1965;194:1077-1080.

5. Kiszewski AE, Durán-Mckinster C, Orozco-Covarrubias L, et al. Cutaneous mastocytosis in children: a clinical analysis of 71 cases. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2004;18:285-290.

6. Alto WA, Clarcq L. Cutaneous and systemic manifestations of mastocytosis. Am Fam Physician. 1999;59:3047-3054, 3059-3060.

7. Borenstein DG, Wiesel SW, Boden SD, eds. Low Back and Neck Pain: Comprehensive Diagnosis and Management. 3rd ed. Philadelphia, Pa: Elsevier; 2004.

8. Vigorita VJ. Metabolic bone disease: Part II. In: Vigorita VJ, Ghelman B, Mintz D, eds. Orthopaedic Pathology. 2nd ed. Philadelphia, PA: Walter Kluwer Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. 2008;197.

9. Rosenbaum RC, Frieri M, Metcalfe DD. Patterns of skeletal scintigraphy and their relationship to plasma and urinary histamine levels in systemic mastocytosis. J Nucl Med. 1984;25:859-864.

10. Islas AA, Penaranda E. Generalized brownish macules in infancy. Urticaria pigmentosa. Am Fam Physician. 2009;80:987.

11. Ely JW, Seabury Stone M. The generalized rash: part I. Differential diagnosis. Am Fam Physician. 2010;81:726-734.

12. Archier E, Devaux S, Castela E, et al. Carcinogenic risks of psoralen UV-A therapy and narrowband UV-B therapy in chronic plaque psoriasis: a systematic literature review. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2012;26 Suppl 3:22-31.

Infection prevention

Not a long ago, I received a call from a friend working in a local pediatric clinic. One of her partners had just seen a young child with an unusual rash. The diagnosis? Crusted scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, the mite that causes typical scabies, also causes crusted or Norwegian scabies. These terms refer to severe infestations that occur in individuals who are immune compromised or debilitated. The rash is characterized by vesicles and thick crusts and may or may not be itchy. Because patients with crusted scabies can be infested with as many as 2 million mites, transmission from very brief skin-to-skin contact is possible, and outbreaks have occurred in health care facilities and other institutional settings.

That was the reason for my friend’s call. “What do we do for the doctors and nurses in the clinic who saw the patient?” she wanted to know.

“Everyone wore gloves, right?” I asked. There was silence on the other end of the phone.

After a quick consultation with our health department, every health care provider (HCP) who touched the patient without gloves was treated preemptively with topical permethrin. None went on to develop scabies. The experience prompted me to think about the challenges of infection prevention in ambulatory care.

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings,” Pediatrics 2007;20[3]:650-65) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Guide to Infection Prevention for Outpatient Settings: Minimum Expectations for Safe Care) have published recommendations for infection prevention in outpatient settings. Both organizations emphasize the importance of standard precautions. According to the CDC, standard precautions “are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.” They are designed to protect HCPs, as well as prevent us from spreading infections among patients. Standard precautions include:

• Hand hygiene.

• Use of personal protective equipment (gloves, gowns, masks).

• Safe injection practices.

• Safe handling of potentially contaminated equipment or surfaces in the patient environment.

• Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette.

Some of these elements are likely second nature to office-based pediatricians. Hands must be cleaned before and after every patient encounter or an encounter with the patient’s immediate environment. “Cover your cough” signs have become ubiquitous in ambulatory care waiting rooms, even as we acknowledge the difficulties associated with expecting toddlers to wear masks or use a tissue to contain their coughs and sneezes.

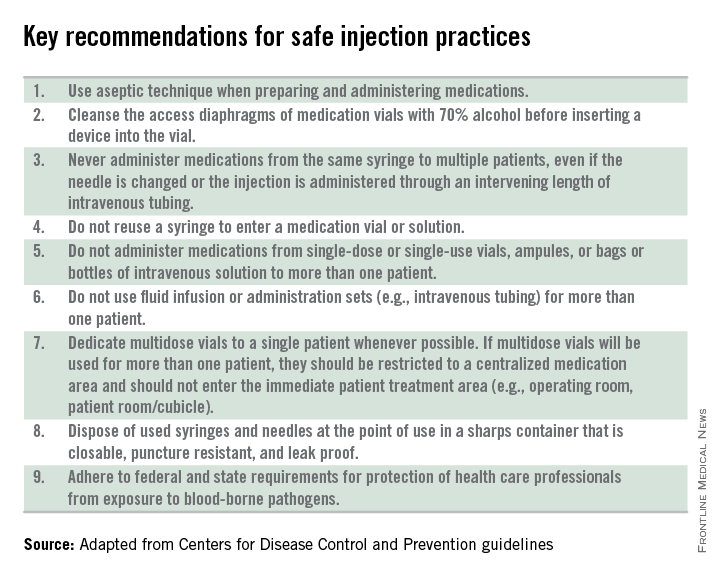

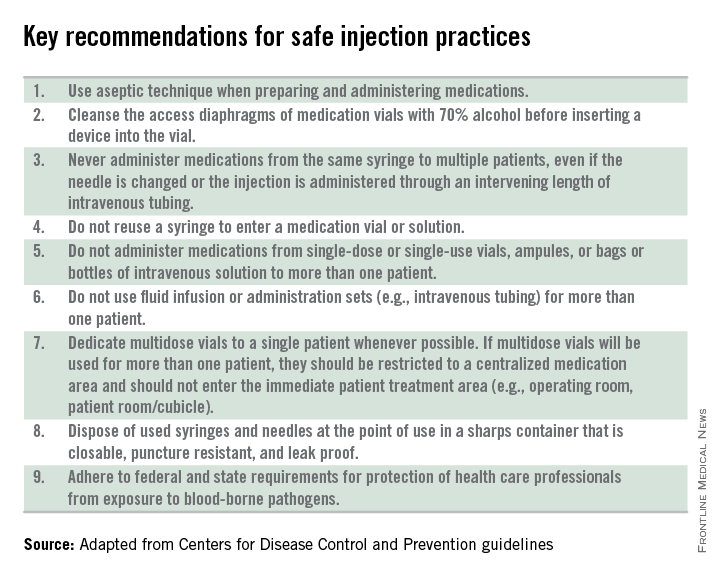

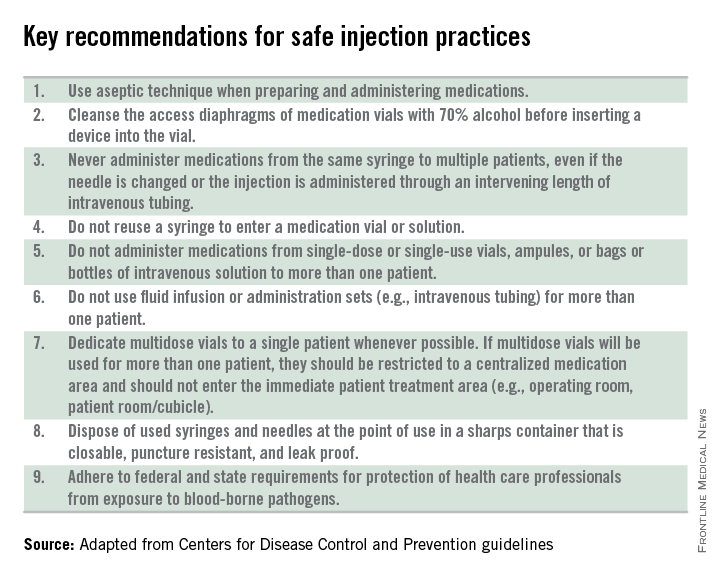

Other elements of standard precautions may receive increased attention because the consequences of noncompliance are perceived to be dangerous or severe. For example, we know that failure to reliably employ safe injection practices (see table) has resulted in transmission of blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B and C, in ambulatory settings.

In my experience, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the ambulatory setting is the element of standard precautions that is the least understood and perhaps the most underutilized. It’s certainly easier in the inpatient setting, where we use transmission-based precautions, and colorful isolation signs instruct us to put on gown and gloves when we visit the patient with viral gastroenteritis, or gown, gloves, and mask for the child with acute viral respiratory tract infection. In the office, we expect the HCP to anticipate what kind of contact with blood or body fluids is likely and choose PPE accordingly.

Of course, anticipation can be tricky. Gowns, for example, are only required during procedures or activities when contact with blood and body fluids is likely. In routine office-based care, these sorts of procedures are uncommon. Incision and drainage of an abscess is one example of a procedure that might warrant protection of one’s clothing with a gown. Conversely, the need for a mask might arise several times a day, as these are worn to protect the mouth, nose, and eyes “during procedures that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood or other body fluids.” Examination of a coughing patient is a common “procedure” likely to results in sprays of saliva. Use of a mask can protect the examiner from potential exposures to Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and a host of respiratory viruses.

While the AAP has been careful to point out that gloves are not needed for the routine care of well children, they should be used when “there is the potential to contact blood, body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or potentially infectious material.” In our world, potentially infectious material might include a cluster of vesicles thought to be herpes simplex, the honey-crusted lesions of impetigo, or the weeping, crusted rash of Norwegian scabies.

My own office had a powerful reminder about the importance of standard precautions last year when we were referred a young infant with recurrent fevers and a mostly dry, peeling rash. As we learned in medical school, the mucocutanous lesions of congenital syphilis can be highly contagious. In accordance with AAP recommendations, all HCPs who examined this child without the protection of gloves underwent serologic testing for syphilis. Fortunately, there were no transmissions!

Published data about infectious disease exposures and the transmission of infectious diseases in the outpatient setting, either from patients to health care workers or among patients, are largely limited to outbreak or case reports. A 1991 review identified 53 reports of infectious disease transmission in outpatient settings between 1961 and 1990 (JAMA 1991;265(18): 2377-81). Transmission occurred in medical and dental offices, clinics, emergency departments, ophthalmology offices, and alternative care settings that included chiropractic clinics and an acupuncture practice. A variety of pathogens were involved, including measles, adenovirus, hepatitis B, atypical mycobacteria, and Streptococcus pyogenes. The authors concluded that many of the outbreaks and episodes of transmission could have been prevented “if existing infection control guidelines,” including what we now consider standard precautions, had been utilized. Many reports published in the intervening 25 years have come to similar conclusions.

So why don’t HCPs yet follow standard precautions, including appropriate use of PPE? The reasons are complex and multifactorial. We’re all busy and lack of time is a common complaint. Gowns, gloves, masks, and alcohol hand gel aren’t always readily available. Some HCPs may not be knowledgeable about the elements of standard precautions while others may not understand the risks to themselves and their patients associated with nonadherence. Finally, some organizations have not established clear expectations related to infection prevention and compliance with AAP and CDC recommendations.

Several years ago, at the very beginning of the H1N1 influenza epidemic, a colleague of mine working in a pediatric practice saw a patient complaining of fever, lethargy, and myalgia. Not surprisingly, the patient’s rapid influenza test was positive. My colleague recalls that she was handed the result before she ever walked into the room – without any PPE – to see the patient.

“This was different than my usual routine at the hospital,” she told me. The expectation at the hospital was gown, gloves, and masks for any patient with influenza or influenzalike illness. At the office though, there was no such expectation, and providers did not routinely wear masks, even when seeing patients with respiratory symptoms. My colleague wasn’t reckless or rebellious. She was simply conforming to the culture in that office, and following the behavioral cues of more senior physicians in the practice. Subsequently, she developed severe influenza infection requiring a prolonged hospital stay.

It’s time to change the culture. As a first step, perform a quick audit in the office, using the AAP’s “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings” as a guide.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Not a long ago, I received a call from a friend working in a local pediatric clinic. One of her partners had just seen a young child with an unusual rash. The diagnosis? Crusted scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, the mite that causes typical scabies, also causes crusted or Norwegian scabies. These terms refer to severe infestations that occur in individuals who are immune compromised or debilitated. The rash is characterized by vesicles and thick crusts and may or may not be itchy. Because patients with crusted scabies can be infested with as many as 2 million mites, transmission from very brief skin-to-skin contact is possible, and outbreaks have occurred in health care facilities and other institutional settings.

That was the reason for my friend’s call. “What do we do for the doctors and nurses in the clinic who saw the patient?” she wanted to know.

“Everyone wore gloves, right?” I asked. There was silence on the other end of the phone.

After a quick consultation with our health department, every health care provider (HCP) who touched the patient without gloves was treated preemptively with topical permethrin. None went on to develop scabies. The experience prompted me to think about the challenges of infection prevention in ambulatory care.

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings,” Pediatrics 2007;20[3]:650-65) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Guide to Infection Prevention for Outpatient Settings: Minimum Expectations for Safe Care) have published recommendations for infection prevention in outpatient settings. Both organizations emphasize the importance of standard precautions. According to the CDC, standard precautions “are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.” They are designed to protect HCPs, as well as prevent us from spreading infections among patients. Standard precautions include:

• Hand hygiene.

• Use of personal protective equipment (gloves, gowns, masks).

• Safe injection practices.

• Safe handling of potentially contaminated equipment or surfaces in the patient environment.

• Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette.

Some of these elements are likely second nature to office-based pediatricians. Hands must be cleaned before and after every patient encounter or an encounter with the patient’s immediate environment. “Cover your cough” signs have become ubiquitous in ambulatory care waiting rooms, even as we acknowledge the difficulties associated with expecting toddlers to wear masks or use a tissue to contain their coughs and sneezes.

Other elements of standard precautions may receive increased attention because the consequences of noncompliance are perceived to be dangerous or severe. For example, we know that failure to reliably employ safe injection practices (see table) has resulted in transmission of blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B and C, in ambulatory settings.

In my experience, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the ambulatory setting is the element of standard precautions that is the least understood and perhaps the most underutilized. It’s certainly easier in the inpatient setting, where we use transmission-based precautions, and colorful isolation signs instruct us to put on gown and gloves when we visit the patient with viral gastroenteritis, or gown, gloves, and mask for the child with acute viral respiratory tract infection. In the office, we expect the HCP to anticipate what kind of contact with blood or body fluids is likely and choose PPE accordingly.

Of course, anticipation can be tricky. Gowns, for example, are only required during procedures or activities when contact with blood and body fluids is likely. In routine office-based care, these sorts of procedures are uncommon. Incision and drainage of an abscess is one example of a procedure that might warrant protection of one’s clothing with a gown. Conversely, the need for a mask might arise several times a day, as these are worn to protect the mouth, nose, and eyes “during procedures that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood or other body fluids.” Examination of a coughing patient is a common “procedure” likely to results in sprays of saliva. Use of a mask can protect the examiner from potential exposures to Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and a host of respiratory viruses.

While the AAP has been careful to point out that gloves are not needed for the routine care of well children, they should be used when “there is the potential to contact blood, body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or potentially infectious material.” In our world, potentially infectious material might include a cluster of vesicles thought to be herpes simplex, the honey-crusted lesions of impetigo, or the weeping, crusted rash of Norwegian scabies.

My own office had a powerful reminder about the importance of standard precautions last year when we were referred a young infant with recurrent fevers and a mostly dry, peeling rash. As we learned in medical school, the mucocutanous lesions of congenital syphilis can be highly contagious. In accordance with AAP recommendations, all HCPs who examined this child without the protection of gloves underwent serologic testing for syphilis. Fortunately, there were no transmissions!

Published data about infectious disease exposures and the transmission of infectious diseases in the outpatient setting, either from patients to health care workers or among patients, are largely limited to outbreak or case reports. A 1991 review identified 53 reports of infectious disease transmission in outpatient settings between 1961 and 1990 (JAMA 1991;265(18): 2377-81). Transmission occurred in medical and dental offices, clinics, emergency departments, ophthalmology offices, and alternative care settings that included chiropractic clinics and an acupuncture practice. A variety of pathogens were involved, including measles, adenovirus, hepatitis B, atypical mycobacteria, and Streptococcus pyogenes. The authors concluded that many of the outbreaks and episodes of transmission could have been prevented “if existing infection control guidelines,” including what we now consider standard precautions, had been utilized. Many reports published in the intervening 25 years have come to similar conclusions.

So why don’t HCPs yet follow standard precautions, including appropriate use of PPE? The reasons are complex and multifactorial. We’re all busy and lack of time is a common complaint. Gowns, gloves, masks, and alcohol hand gel aren’t always readily available. Some HCPs may not be knowledgeable about the elements of standard precautions while others may not understand the risks to themselves and their patients associated with nonadherence. Finally, some organizations have not established clear expectations related to infection prevention and compliance with AAP and CDC recommendations.

Several years ago, at the very beginning of the H1N1 influenza epidemic, a colleague of mine working in a pediatric practice saw a patient complaining of fever, lethargy, and myalgia. Not surprisingly, the patient’s rapid influenza test was positive. My colleague recalls that she was handed the result before she ever walked into the room – without any PPE – to see the patient.

“This was different than my usual routine at the hospital,” she told me. The expectation at the hospital was gown, gloves, and masks for any patient with influenza or influenzalike illness. At the office though, there was no such expectation, and providers did not routinely wear masks, even when seeing patients with respiratory symptoms. My colleague wasn’t reckless or rebellious. She was simply conforming to the culture in that office, and following the behavioral cues of more senior physicians in the practice. Subsequently, she developed severe influenza infection requiring a prolonged hospital stay.

It’s time to change the culture. As a first step, perform a quick audit in the office, using the AAP’s “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings” as a guide.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Not a long ago, I received a call from a friend working in a local pediatric clinic. One of her partners had just seen a young child with an unusual rash. The diagnosis? Crusted scabies.

Sarcoptes scabiei var. hominis, the mite that causes typical scabies, also causes crusted or Norwegian scabies. These terms refer to severe infestations that occur in individuals who are immune compromised or debilitated. The rash is characterized by vesicles and thick crusts and may or may not be itchy. Because patients with crusted scabies can be infested with as many as 2 million mites, transmission from very brief skin-to-skin contact is possible, and outbreaks have occurred in health care facilities and other institutional settings.

That was the reason for my friend’s call. “What do we do for the doctors and nurses in the clinic who saw the patient?” she wanted to know.

“Everyone wore gloves, right?” I asked. There was silence on the other end of the phone.

After a quick consultation with our health department, every health care provider (HCP) who touched the patient without gloves was treated preemptively with topical permethrin. None went on to develop scabies. The experience prompted me to think about the challenges of infection prevention in ambulatory care.

Both the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP Committee on Infectious Diseases, “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings,” Pediatrics 2007;20[3]:650-65) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (Guide to Infection Prevention for Outpatient Settings: Minimum Expectations for Safe Care) have published recommendations for infection prevention in outpatient settings. Both organizations emphasize the importance of standard precautions. According to the CDC, standard precautions “are the minimum infection prevention practices that apply to all patient care, regardless of suspected or confirmed infection status of the patient, in any setting where health care is delivered.” They are designed to protect HCPs, as well as prevent us from spreading infections among patients. Standard precautions include:

• Hand hygiene.

• Use of personal protective equipment (gloves, gowns, masks).

• Safe injection practices.

• Safe handling of potentially contaminated equipment or surfaces in the patient environment.

• Respiratory hygiene/cough etiquette.

Some of these elements are likely second nature to office-based pediatricians. Hands must be cleaned before and after every patient encounter or an encounter with the patient’s immediate environment. “Cover your cough” signs have become ubiquitous in ambulatory care waiting rooms, even as we acknowledge the difficulties associated with expecting toddlers to wear masks or use a tissue to contain their coughs and sneezes.

Other elements of standard precautions may receive increased attention because the consequences of noncompliance are perceived to be dangerous or severe. For example, we know that failure to reliably employ safe injection practices (see table) has resulted in transmission of blood-borne pathogens, including hepatitis B and C, in ambulatory settings.

In my experience, the use of personal protective equipment (PPE) in the ambulatory setting is the element of standard precautions that is the least understood and perhaps the most underutilized. It’s certainly easier in the inpatient setting, where we use transmission-based precautions, and colorful isolation signs instruct us to put on gown and gloves when we visit the patient with viral gastroenteritis, or gown, gloves, and mask for the child with acute viral respiratory tract infection. In the office, we expect the HCP to anticipate what kind of contact with blood or body fluids is likely and choose PPE accordingly.

Of course, anticipation can be tricky. Gowns, for example, are only required during procedures or activities when contact with blood and body fluids is likely. In routine office-based care, these sorts of procedures are uncommon. Incision and drainage of an abscess is one example of a procedure that might warrant protection of one’s clothing with a gown. Conversely, the need for a mask might arise several times a day, as these are worn to protect the mouth, nose, and eyes “during procedures that are likely to generate splashes or sprays of blood or other body fluids.” Examination of a coughing patient is a common “procedure” likely to results in sprays of saliva. Use of a mask can protect the examiner from potential exposures to Bordetella pertussis, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, and a host of respiratory viruses.

While the AAP has been careful to point out that gloves are not needed for the routine care of well children, they should be used when “there is the potential to contact blood, body fluids, mucous membranes, nonintact skin, or potentially infectious material.” In our world, potentially infectious material might include a cluster of vesicles thought to be herpes simplex, the honey-crusted lesions of impetigo, or the weeping, crusted rash of Norwegian scabies.

My own office had a powerful reminder about the importance of standard precautions last year when we were referred a young infant with recurrent fevers and a mostly dry, peeling rash. As we learned in medical school, the mucocutanous lesions of congenital syphilis can be highly contagious. In accordance with AAP recommendations, all HCPs who examined this child without the protection of gloves underwent serologic testing for syphilis. Fortunately, there were no transmissions!

Published data about infectious disease exposures and the transmission of infectious diseases in the outpatient setting, either from patients to health care workers or among patients, are largely limited to outbreak or case reports. A 1991 review identified 53 reports of infectious disease transmission in outpatient settings between 1961 and 1990 (JAMA 1991;265(18): 2377-81). Transmission occurred in medical and dental offices, clinics, emergency departments, ophthalmology offices, and alternative care settings that included chiropractic clinics and an acupuncture practice. A variety of pathogens were involved, including measles, adenovirus, hepatitis B, atypical mycobacteria, and Streptococcus pyogenes. The authors concluded that many of the outbreaks and episodes of transmission could have been prevented “if existing infection control guidelines,” including what we now consider standard precautions, had been utilized. Many reports published in the intervening 25 years have come to similar conclusions.

So why don’t HCPs yet follow standard precautions, including appropriate use of PPE? The reasons are complex and multifactorial. We’re all busy and lack of time is a common complaint. Gowns, gloves, masks, and alcohol hand gel aren’t always readily available. Some HCPs may not be knowledgeable about the elements of standard precautions while others may not understand the risks to themselves and their patients associated with nonadherence. Finally, some organizations have not established clear expectations related to infection prevention and compliance with AAP and CDC recommendations.

Several years ago, at the very beginning of the H1N1 influenza epidemic, a colleague of mine working in a pediatric practice saw a patient complaining of fever, lethargy, and myalgia. Not surprisingly, the patient’s rapid influenza test was positive. My colleague recalls that she was handed the result before she ever walked into the room – without any PPE – to see the patient.

“This was different than my usual routine at the hospital,” she told me. The expectation at the hospital was gown, gloves, and masks for any patient with influenza or influenzalike illness. At the office though, there was no such expectation, and providers did not routinely wear masks, even when seeing patients with respiratory symptoms. My colleague wasn’t reckless or rebellious. She was simply conforming to the culture in that office, and following the behavioral cues of more senior physicians in the practice. Subsequently, she developed severe influenza infection requiring a prolonged hospital stay.

It’s time to change the culture. As a first step, perform a quick audit in the office, using the AAP’s “Infection prevention and control in pediatric ambulatory settings” as a guide.

Dr. Bryant is a pediatrician specializing in infectious diseases at the University of Louisville (Ky.) and Kosair Children’s Hospital, also in Louisville. She had no relevant financial disclosures.

Variations in blood cancer survival across Europe

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

VIENNA—Results of the EUROCARE-5 study have revealed regional differences in survival for European patients with hematologic malignancies.

The data showed regional variations in 5-year relative survival rates for a number of cancers.

But the differences were particularly pronounced for leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), and plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs).

Milena Sant, MD, of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan, Italy, presented these results at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (LBA 1).

Data from this study have also been published in several articles in the October 2015 issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

EUROCARE-5 includes records from 22 million cancer patients diagnosed between 1978 and 2007. The latest data encompass more than 10 million patients (ages 15 and older) diagnosed from 1995 to 2007 and followed up to 2008.

The data came from 107 cancer registries in 29 countries. The researchers estimated 5-year relative survival and trends from 1999 to 2007 according to region—Ireland/UK, Northern Europe, Central Europe, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe.

“In general, 5-year relative survival—survival that is adjusted for causes of death other than cancer—increased steadily over time in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe, for most cancers,” Dr Sant said.

“However, the most dramatic geographical variations were observed for cancers of the blood where there have been recent advances in treatment, such as chronic myeloid and lymphocytic leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 2 of its subtypes (follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and multiple myeloma. Hodgkin lymphoma was the exception, with smaller regional variations and a fairly good prognosis in most countries.”

Hodgkin lymphoma and NHL

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was highest for Hodgkin lymphoma, at 80.8% (40,625 cases). Five-year survival was 79.4% in Ireland and the UK, 85% in Northern countries, and 74.3% in Eastern Europe, which was significantly below the European average (P<0.0001).

For NHL, the 5-year relative survival was 59.4% (329,204 cases). Survival rates for NHL patients ranged from 49.7% in Eastern Europe to 63.3% in Northern Europe.

CLL/SLL

For chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), the 5-year relative survival was 70.4% (81,914 cases). CLL/SLL survival ranged from 58% in Eastern Europe to about 74% in Central and Northern Europe.

The researchers noted that between-country variations in CLL/SLL survival were high in all regions. Outliers that were significantly below the regional average were Austria (67%), Croatia (52%), and Bulgaria (45.5%).

PCNs

PCNs included multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, and plasma cell leukemias. The 5-year relative survival for all PCNs was 39.2% (94,024 cases).

PCN survival rates were lowest in Eastern Europe (31.7%), slightly higher in the UK/Ireland (35.9%), and between 39.1% and 42% in the rest of Europe.

Myeloid leukemias

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was poorest for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), at 17.1% (57,026 cases).

AML survival rates in Ireland/UK (15.0%) and Eastern Europe (13.0%) were significantly below the European average. But AML survival in Sweden, Belgium, France, and Germany was significantly higher than the average (P<0.005).

Five-year relative survival for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was 52.9% (17,713 cases).

Of all the hematologic malignancies, the survival gap between Eastern Europe and the rest of Europe was highest for CML. Five-year survival for CML patients was 33% in Eastern Europe and ranged from 51% to 58% in the rest of Europe.

The researchers also said there were striking survival variations by country in all areas. They found significant deviations from the regional average in Sweden (69.7%), Scotland (64.6%), France (71.7%), Austria (48.2%), Croatia (37.8%), Estonia (48.9%), Czech Republic (45.2%), and Latvia (22.1%).

“Results from EUROCARE can help to identify regions of low survival where action is needed to improve patients’ outcomes,” Dr Sant noted.

“Population-based survival information is essential for physicians, policy-makers, administrators, researchers, and patient organizations who deal with the needs of cancer patients, as well as with the issue of the growing expenditure on healthcare.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

VIENNA—Results of the EUROCARE-5 study have revealed regional differences in survival for European patients with hematologic malignancies.

The data showed regional variations in 5-year relative survival rates for a number of cancers.

But the differences were particularly pronounced for leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), and plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs).

Milena Sant, MD, of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan, Italy, presented these results at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (LBA 1).

Data from this study have also been published in several articles in the October 2015 issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

EUROCARE-5 includes records from 22 million cancer patients diagnosed between 1978 and 2007. The latest data encompass more than 10 million patients (ages 15 and older) diagnosed from 1995 to 2007 and followed up to 2008.

The data came from 107 cancer registries in 29 countries. The researchers estimated 5-year relative survival and trends from 1999 to 2007 according to region—Ireland/UK, Northern Europe, Central Europe, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe.

“In general, 5-year relative survival—survival that is adjusted for causes of death other than cancer—increased steadily over time in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe, for most cancers,” Dr Sant said.

“However, the most dramatic geographical variations were observed for cancers of the blood where there have been recent advances in treatment, such as chronic myeloid and lymphocytic leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 2 of its subtypes (follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and multiple myeloma. Hodgkin lymphoma was the exception, with smaller regional variations and a fairly good prognosis in most countries.”

Hodgkin lymphoma and NHL

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was highest for Hodgkin lymphoma, at 80.8% (40,625 cases). Five-year survival was 79.4% in Ireland and the UK, 85% in Northern countries, and 74.3% in Eastern Europe, which was significantly below the European average (P<0.0001).

For NHL, the 5-year relative survival was 59.4% (329,204 cases). Survival rates for NHL patients ranged from 49.7% in Eastern Europe to 63.3% in Northern Europe.

CLL/SLL

For chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), the 5-year relative survival was 70.4% (81,914 cases). CLL/SLL survival ranged from 58% in Eastern Europe to about 74% in Central and Northern Europe.

The researchers noted that between-country variations in CLL/SLL survival were high in all regions. Outliers that were significantly below the regional average were Austria (67%), Croatia (52%), and Bulgaria (45.5%).

PCNs

PCNs included multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, and plasma cell leukemias. The 5-year relative survival for all PCNs was 39.2% (94,024 cases).

PCN survival rates were lowest in Eastern Europe (31.7%), slightly higher in the UK/Ireland (35.9%), and between 39.1% and 42% in the rest of Europe.

Myeloid leukemias

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was poorest for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), at 17.1% (57,026 cases).

AML survival rates in Ireland/UK (15.0%) and Eastern Europe (13.0%) were significantly below the European average. But AML survival in Sweden, Belgium, France, and Germany was significantly higher than the average (P<0.005).

Five-year relative survival for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was 52.9% (17,713 cases).

Of all the hematologic malignancies, the survival gap between Eastern Europe and the rest of Europe was highest for CML. Five-year survival for CML patients was 33% in Eastern Europe and ranged from 51% to 58% in the rest of Europe.

The researchers also said there were striking survival variations by country in all areas. They found significant deviations from the regional average in Sweden (69.7%), Scotland (64.6%), France (71.7%), Austria (48.2%), Croatia (37.8%), Estonia (48.9%), Czech Republic (45.2%), and Latvia (22.1%).

“Results from EUROCARE can help to identify regions of low survival where action is needed to improve patients’ outcomes,” Dr Sant noted.

“Population-based survival information is essential for physicians, policy-makers, administrators, researchers, and patient organizations who deal with the needs of cancer patients, as well as with the issue of the growing expenditure on healthcare.” ![]()

chemotherapy

Photo by Rhoda Baer

VIENNA—Results of the EUROCARE-5 study have revealed regional differences in survival for European patients with hematologic malignancies.

The data showed regional variations in 5-year relative survival rates for a number of cancers.

But the differences were particularly pronounced for leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphomas (NHLs), and plasma cell neoplasms (PCNs).

Milena Sant, MD, of the Fondazione IRCCS Istituto Nazionale dei Tumori in Milan, Italy, presented these results at the 2015 European Cancer Congress (LBA 1).

Data from this study have also been published in several articles in the October 2015 issue of the European Journal of Cancer.

EUROCARE-5 includes records from 22 million cancer patients diagnosed between 1978 and 2007. The latest data encompass more than 10 million patients (ages 15 and older) diagnosed from 1995 to 2007 and followed up to 2008.

The data came from 107 cancer registries in 29 countries. The researchers estimated 5-year relative survival and trends from 1999 to 2007 according to region—Ireland/UK, Northern Europe, Central Europe, Southern Europe, and Eastern Europe.

“In general, 5-year relative survival—survival that is adjusted for causes of death other than cancer—increased steadily over time in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe, for most cancers,” Dr Sant said.

“However, the most dramatic geographical variations were observed for cancers of the blood where there have been recent advances in treatment, such as chronic myeloid and lymphocytic leukemias, non-Hodgkin lymphoma and 2 of its subtypes (follicular and diffuse large B-cell lymphoma), and multiple myeloma. Hodgkin lymphoma was the exception, with smaller regional variations and a fairly good prognosis in most countries.”

Hodgkin lymphoma and NHL

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was highest for Hodgkin lymphoma, at 80.8% (40,625 cases). Five-year survival was 79.4% in Ireland and the UK, 85% in Northern countries, and 74.3% in Eastern Europe, which was significantly below the European average (P<0.0001).

For NHL, the 5-year relative survival was 59.4% (329,204 cases). Survival rates for NHL patients ranged from 49.7% in Eastern Europe to 63.3% in Northern Europe.

CLL/SLL

For chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL), the 5-year relative survival was 70.4% (81,914 cases). CLL/SLL survival ranged from 58% in Eastern Europe to about 74% in Central and Northern Europe.

The researchers noted that between-country variations in CLL/SLL survival were high in all regions. Outliers that were significantly below the regional average were Austria (67%), Croatia (52%), and Bulgaria (45.5%).

PCNs

PCNs included multiple myeloma, plasmacytoma, and plasma cell leukemias. The 5-year relative survival for all PCNs was 39.2% (94,024 cases).

PCN survival rates were lowest in Eastern Europe (31.7%), slightly higher in the UK/Ireland (35.9%), and between 39.1% and 42% in the rest of Europe.

Myeloid leukemias

Of all the hematologic malignancies, 5-year relative survival was poorest for patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML), at 17.1% (57,026 cases).

AML survival rates in Ireland/UK (15.0%) and Eastern Europe (13.0%) were significantly below the European average. But AML survival in Sweden, Belgium, France, and Germany was significantly higher than the average (P<0.005).

Five-year relative survival for chronic myeloid leukemia (CML) was 52.9% (17,713 cases).

Of all the hematologic malignancies, the survival gap between Eastern Europe and the rest of Europe was highest for CML. Five-year survival for CML patients was 33% in Eastern Europe and ranged from 51% to 58% in the rest of Europe.

The researchers also said there were striking survival variations by country in all areas. They found significant deviations from the regional average in Sweden (69.7%), Scotland (64.6%), France (71.7%), Austria (48.2%), Croatia (37.8%), Estonia (48.9%), Czech Republic (45.2%), and Latvia (22.1%).

“Results from EUROCARE can help to identify regions of low survival where action is needed to improve patients’ outcomes,” Dr Sant noted.

“Population-based survival information is essential for physicians, policy-makers, administrators, researchers, and patient organizations who deal with the needs of cancer patients, as well as with the issue of the growing expenditure on healthcare.” ![]()

mAb produces ‘encouraging’ results in MM

multiple myeloma

ROME—Combination therapy incorporating a novel monoclonal antibody (mAb) can provide “encouraging, long-lasting tumor control” in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to investigators.

The mAb, MOR202, was also considered to be well-tolerated in this ongoing phase 1/2a study.

Early results from this study were presented at the 15th International Myeloma Workshop (poster #156). The study was sponsored by MorphoSys AG, makers of MOR202. The poster is available on the company’s website.

MOR202 is a HuCAL-derived mAb directed against CD38. In the phase 1/2a study, 50 MM patients have received the drug thus far.

At baseline, the patients’ median age was 67. They had received a median of 4 prior therapies, including bortezomib (98%), lenalidomide (92%), melphalan (92%), cyclophosphamide (76%), doxorubicin (60%), thalidomide (32%), pomalidomide (14%), carfilzomib (6%), elotuzumab (4%), and panobinostat (4%). Seventy-six percent had received a stem cell transplant.

Study design

The study consists of several parts and dosing cohorts in which the investigators are assessing MOR202 alone or in combination with other agents.

Treatment in Part A consists of a 2-hour intravenous infusion of MOR202 once every 2 weeks at several different doses: 0.01 mg/kg , 0.04 mg/kg, 0.15 mg/kg, 0.5 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, 4.0 mg/kg, 8.0 mg/kg, or 16.0 mg/kg.

Part B is a 2-hour intravenous infusion of MOR202 once a week at 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, or 16 mg/kg.

Part C is dexamethasone plus MOR202 once a week at 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, or 16 mg/kg.

Part D is pomalidomide, dexamethasone, and MOR202 once a week at 8 mg/kg or 16 mg/kg.

Part E is lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and MOR202 once a week at 8 mg/kg or 16 mg/kg.

In the confirmatory cohorts, patients receive MOR202 with or without dexamethasone once a week or once every 2 weeks, MOR202 with pomalidomide and dexamethasone once a week, or MOR202 with lenalidomide and dexamethasone once a week.

Efficacy

Of the 50 patients treated thus far, 27 were evaluable for efficacy. One patient achieved a very good partial response, 2 had a partial response, and 2 had a minor response. Eleven patients had stable disease, and 11 progressed.

The very good partial response occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 4 mg/kg plus dexamethasone.

One partial response occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 8 mg/kg plus dexamethasone. The other occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 8 mg/kg plus dexamethasone and pomalidomide.

One minor response occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 8 mg/kg plus dexamethasone and lenalidomide. The other occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 16 mg/kg plus dexamethasone.

“[T]he preliminary efficacy seen so far with MOR202 as single agent and in combinations is promising,” said investigator Marc-Steffen Raab, MD, of Heidelberg University Hospital and the German Cancer Research Center DKFZ in Heidelberg, Germany.

Safety

All 50 patients were evaluable for safety. Ninety-eight percent experienced an adverse event (AE), 66% of which were grade 3 or higher.

The most frequent AEs (overall and grade 3 or higher) were anemia (34%, 6%), leukopenia (30%, 10%), neutropenia (20%, 10%), thrombocytopenia (18%, 8%), fatigue (30%, 0%), nausea (22%, 0%), diarrhea (20%, 0%), and headache (16%, 0%).

Thirty-six percent of patients discontinued MOR202 due to treatment-emergent AEs. However, only 6% (n=3) of these AEs were considered possibly related to MOR202.

Infusion-related reactions occurred in 15 patients (30%). One of these patients received dexamethasone as well and experienced an infusion-related reaction (grade 1).

In the absence of dexamethasone, nearly all infusion reactions were grade 1-2. The exception was 1 patient with a grade 3 reaction that was mainly limited to the first infusion.

The maximum tolerated dose of MOR202 has not been reached.

“Considering the low rate of infusion reactions, even in cohorts without dexamethasone, the short infusion time, and other aspects, MOR202 may turn out to be an excellent choice in terms of safety and tolerability,” Dr Raab concluded. ![]()

multiple myeloma

ROME—Combination therapy incorporating a novel monoclonal antibody (mAb) can provide “encouraging, long-lasting tumor control” in heavily pretreated patients with relapsed/refractory multiple myeloma (MM), according to investigators.

The mAb, MOR202, was also considered to be well-tolerated in this ongoing phase 1/2a study.

Early results from this study were presented at the 15th International Myeloma Workshop (poster #156). The study was sponsored by MorphoSys AG, makers of MOR202. The poster is available on the company’s website.

MOR202 is a HuCAL-derived mAb directed against CD38. In the phase 1/2a study, 50 MM patients have received the drug thus far.

At baseline, the patients’ median age was 67. They had received a median of 4 prior therapies, including bortezomib (98%), lenalidomide (92%), melphalan (92%), cyclophosphamide (76%), doxorubicin (60%), thalidomide (32%), pomalidomide (14%), carfilzomib (6%), elotuzumab (4%), and panobinostat (4%). Seventy-six percent had received a stem cell transplant.

Study design

The study consists of several parts and dosing cohorts in which the investigators are assessing MOR202 alone or in combination with other agents.

Treatment in Part A consists of a 2-hour intravenous infusion of MOR202 once every 2 weeks at several different doses: 0.01 mg/kg , 0.04 mg/kg, 0.15 mg/kg, 0.5 mg/kg, 1.5 mg/kg, 4.0 mg/kg, 8.0 mg/kg, or 16.0 mg/kg.

Part B is a 2-hour intravenous infusion of MOR202 once a week at 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, or 16 mg/kg.

Part C is dexamethasone plus MOR202 once a week at 4 mg/kg, 8 mg/kg, or 16 mg/kg.

Part D is pomalidomide, dexamethasone, and MOR202 once a week at 8 mg/kg or 16 mg/kg.

Part E is lenalidomide, dexamethasone, and MOR202 once a week at 8 mg/kg or 16 mg/kg.

In the confirmatory cohorts, patients receive MOR202 with or without dexamethasone once a week or once every 2 weeks, MOR202 with pomalidomide and dexamethasone once a week, or MOR202 with lenalidomide and dexamethasone once a week.

Efficacy

Of the 50 patients treated thus far, 27 were evaluable for efficacy. One patient achieved a very good partial response, 2 had a partial response, and 2 had a minor response. Eleven patients had stable disease, and 11 progressed.

The very good partial response occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 4 mg/kg plus dexamethasone.

One partial response occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 8 mg/kg plus dexamethasone. The other occurred in a patient receiving weekly MOR202 at 8 mg/kg plus dexamethasone and pomalidomide.