User login

Intraoperative Hypotension Predicts Postoperative Mortality

Clinical question: What blood pressure deviations during surgery are predictive of mortality?

Background: Despite the widely assumed importance of blood pressure (BP) management on postoperative outcomes, there are no accepted thresholds requiring intervention.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Six Veterans’ Affairs hospitals, 2001-2008.

Synopsis: Intraoperative BP data from 18,756 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery were linked with procedure, patient-related risk factors, and 30-day mortality data from the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Overall 30-day mortality was 1.8%. Using three different methods for defining hyper- or hypotension (based on standard deviations from the mean in this population, absolute thresholds suggested by medical literature, or by changes from baseline BP), no measure of hypertension predicted mortality; however, after adjusting for 10 preoperative patient-related risk factors, extremely low BP for five minutes or more (whether defined as systolic BP <70 mmHg, mean arterial pressure <49 mmHg, or diastolic BP <30 mmHg) was associated with 30-day mortality, with statistically significant odds ratios in the 2.4-3.2 range.

Because this is an observational study, no causal relationship can be established from these data. Low BPs could be markers for sicker patients with increased mortality, despite researchers’ efforts to adjust for known preoperative risks.

Bottom line: Intraoperative hypotension lasting five minutes or more, but not intraoperative hypertension, predicts 30-day mortality.

Citation: Monk TG, Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(2):307-319.

Clinical question: What blood pressure deviations during surgery are predictive of mortality?

Background: Despite the widely assumed importance of blood pressure (BP) management on postoperative outcomes, there are no accepted thresholds requiring intervention.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Six Veterans’ Affairs hospitals, 2001-2008.

Synopsis: Intraoperative BP data from 18,756 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery were linked with procedure, patient-related risk factors, and 30-day mortality data from the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Overall 30-day mortality was 1.8%. Using three different methods for defining hyper- or hypotension (based on standard deviations from the mean in this population, absolute thresholds suggested by medical literature, or by changes from baseline BP), no measure of hypertension predicted mortality; however, after adjusting for 10 preoperative patient-related risk factors, extremely low BP for five minutes or more (whether defined as systolic BP <70 mmHg, mean arterial pressure <49 mmHg, or diastolic BP <30 mmHg) was associated with 30-day mortality, with statistically significant odds ratios in the 2.4-3.2 range.

Because this is an observational study, no causal relationship can be established from these data. Low BPs could be markers for sicker patients with increased mortality, despite researchers’ efforts to adjust for known preoperative risks.

Bottom line: Intraoperative hypotension lasting five minutes or more, but not intraoperative hypertension, predicts 30-day mortality.

Citation: Monk TG, Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(2):307-319.

Clinical question: What blood pressure deviations during surgery are predictive of mortality?

Background: Despite the widely assumed importance of blood pressure (BP) management on postoperative outcomes, there are no accepted thresholds requiring intervention.

Study design: Retrospective cohort.

Setting: Six Veterans’ Affairs hospitals, 2001-2008.

Synopsis: Intraoperative BP data from 18,756 patients undergoing major noncardiac surgery were linked with procedure, patient-related risk factors, and 30-day mortality data from the VA Surgical Quality Improvement Program database. Overall 30-day mortality was 1.8%. Using three different methods for defining hyper- or hypotension (based on standard deviations from the mean in this population, absolute thresholds suggested by medical literature, or by changes from baseline BP), no measure of hypertension predicted mortality; however, after adjusting for 10 preoperative patient-related risk factors, extremely low BP for five minutes or more (whether defined as systolic BP <70 mmHg, mean arterial pressure <49 mmHg, or diastolic BP <30 mmHg) was associated with 30-day mortality, with statistically significant odds ratios in the 2.4-3.2 range.

Because this is an observational study, no causal relationship can be established from these data. Low BPs could be markers for sicker patients with increased mortality, despite researchers’ efforts to adjust for known preoperative risks.

Bottom line: Intraoperative hypotension lasting five minutes or more, but not intraoperative hypertension, predicts 30-day mortality.

Citation: Monk TG, Bronsert MR, Henderson WG, et al. Association between intraoperative hypotension and hypertension and 30-day postoperative mortality in noncardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2015;123(2):307-319.

Caprini Risk Assessment Tool Can Distinguish High Risk of VTE in Critically Ill Surgical Patients

Clinical question: Is the Caprini Risk Assessment Model for VTE risk valid in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: Critically ill surgical patients are at increased risk of developing VTE. Chemoprophylaxis decreases VTE risk, but benefits must be balanced against bleeding risk. Rapid and accurate risk stratification supports decisions about prophylaxis; however, data regarding appropriate risk stratification are limited.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Surgical ICU (SICU) at a single, U.S. academic medical center, 2007-2013.

Synopsis: Among 4,844 consecutive admissions, the in-hospital VTE rate was 7.5% (364). Using a previously validated, computer-generated, retrospective risk score based on the 2005 Caprini model, patients were most commonly at moderate risk for VTE upon ICU admission (32%). Fifteen percent (723) were extremely high risk. VTE incidence increased linearly with increasing Caprini scores. Data were abstracted from multiple electronic sources.

Younger age, recent sepsis or pneumonia, central venous access on ICU admission, personal VTE history, and operative procedure were significantly associated with inpatient VTE events. The proportion of patients who received chemoprophylaxis postoperatively was similar regardless of VTE risk. Patients at higher risk were more likely to receive chemoprophylaxis preoperatively.

Results from this retrospective, single-center study suggest that Caprini is a valid tool to predict inpatient VTE risk in this population. Inclusion of multiple risk factors may make calculation of this score prohibitive in other settings unless it can be computer generated.

Bottom line: Caprini risk scores accurately distinguish critically ill surgical patients at high risk of VTE from those at lower risk.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1841.

Clinical question: Is the Caprini Risk Assessment Model for VTE risk valid in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: Critically ill surgical patients are at increased risk of developing VTE. Chemoprophylaxis decreases VTE risk, but benefits must be balanced against bleeding risk. Rapid and accurate risk stratification supports decisions about prophylaxis; however, data regarding appropriate risk stratification are limited.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Surgical ICU (SICU) at a single, U.S. academic medical center, 2007-2013.

Synopsis: Among 4,844 consecutive admissions, the in-hospital VTE rate was 7.5% (364). Using a previously validated, computer-generated, retrospective risk score based on the 2005 Caprini model, patients were most commonly at moderate risk for VTE upon ICU admission (32%). Fifteen percent (723) were extremely high risk. VTE incidence increased linearly with increasing Caprini scores. Data were abstracted from multiple electronic sources.

Younger age, recent sepsis or pneumonia, central venous access on ICU admission, personal VTE history, and operative procedure were significantly associated with inpatient VTE events. The proportion of patients who received chemoprophylaxis postoperatively was similar regardless of VTE risk. Patients at higher risk were more likely to receive chemoprophylaxis preoperatively.

Results from this retrospective, single-center study suggest that Caprini is a valid tool to predict inpatient VTE risk in this population. Inclusion of multiple risk factors may make calculation of this score prohibitive in other settings unless it can be computer generated.

Bottom line: Caprini risk scores accurately distinguish critically ill surgical patients at high risk of VTE from those at lower risk.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1841.

Clinical question: Is the Caprini Risk Assessment Model for VTE risk valid in critically ill surgical patients?

Background: Critically ill surgical patients are at increased risk of developing VTE. Chemoprophylaxis decreases VTE risk, but benefits must be balanced against bleeding risk. Rapid and accurate risk stratification supports decisions about prophylaxis; however, data regarding appropriate risk stratification are limited.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Surgical ICU (SICU) at a single, U.S. academic medical center, 2007-2013.

Synopsis: Among 4,844 consecutive admissions, the in-hospital VTE rate was 7.5% (364). Using a previously validated, computer-generated, retrospective risk score based on the 2005 Caprini model, patients were most commonly at moderate risk for VTE upon ICU admission (32%). Fifteen percent (723) were extremely high risk. VTE incidence increased linearly with increasing Caprini scores. Data were abstracted from multiple electronic sources.

Younger age, recent sepsis or pneumonia, central venous access on ICU admission, personal VTE history, and operative procedure were significantly associated with inpatient VTE events. The proportion of patients who received chemoprophylaxis postoperatively was similar regardless of VTE risk. Patients at higher risk were more likely to receive chemoprophylaxis preoperatively.

Results from this retrospective, single-center study suggest that Caprini is a valid tool to predict inpatient VTE risk in this population. Inclusion of multiple risk factors may make calculation of this score prohibitive in other settings unless it can be computer generated.

Bottom line: Caprini risk scores accurately distinguish critically ill surgical patients at high risk of VTE from those at lower risk.

Citation: Obi AT, Pannucci CJ, Nackashi A, et al. Validation of the Caprini venous thromboembolism risk assessment model in critically ill surgical patients. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(10):941-948. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.1841.

Adherence to Restrictive Red Blood Cell Transfusion Guidelines Improved with Peer Feedback

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted approach involving clinician education, peer email feedback, and monthly audit data improve adherence to restrictive red blood cell (RBC) transfusion guidelines?

Background: Randomized controlled trials and professional society guidelines support adoption of RBC transfusion strategies in stable, low-risk patients. Studies suggest that education and feedback from specialists may decrease inappropriate transfusion practices, but peer-to-peer feedback has not yet been explored.

Study design: Prospective, interventional study.

Setting: Tertiary care center SICU, single U.S. academic center.

Synopsis: All stable, low-risk SICU patients receiving RBC transfusions were included in this study. Intervention consisted of educational lectures to clinicians, dissemination of monthly aggregate audit transfusion data, and direct email feedback from a colleague to clinicians ordering transfusions outside of guidelines. Six-month intervention data were compared with six months of pre-intervention data.

During the intervention, total transfusions decreased by 36%, from 284 units to 181 units, and percentage of transfusions outside restrictive guidelines decreased to 2% from 25% (P<0.001). Six months after the end of the intervention period, transfusions outside restrictive guidelines increased back to 17%, suggesting a lack of permanent change in transfusion practices.

Bottom line: A multifaceted approach involving education, peer-to-peer feedback, and monthly audits improved adherence to restrictive RBC transfusion guidelines; however, changes were not sustained.

Citation: Yeh DD, Naraghi L, Larentzakis A, et al. Peer-to-peer physician feedback improves adherence to blood transfusion guidelines in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(1):65-70.

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted approach involving clinician education, peer email feedback, and monthly audit data improve adherence to restrictive red blood cell (RBC) transfusion guidelines?

Background: Randomized controlled trials and professional society guidelines support adoption of RBC transfusion strategies in stable, low-risk patients. Studies suggest that education and feedback from specialists may decrease inappropriate transfusion practices, but peer-to-peer feedback has not yet been explored.

Study design: Prospective, interventional study.

Setting: Tertiary care center SICU, single U.S. academic center.

Synopsis: All stable, low-risk SICU patients receiving RBC transfusions were included in this study. Intervention consisted of educational lectures to clinicians, dissemination of monthly aggregate audit transfusion data, and direct email feedback from a colleague to clinicians ordering transfusions outside of guidelines. Six-month intervention data were compared with six months of pre-intervention data.

During the intervention, total transfusions decreased by 36%, from 284 units to 181 units, and percentage of transfusions outside restrictive guidelines decreased to 2% from 25% (P<0.001). Six months after the end of the intervention period, transfusions outside restrictive guidelines increased back to 17%, suggesting a lack of permanent change in transfusion practices.

Bottom line: A multifaceted approach involving education, peer-to-peer feedback, and monthly audits improved adherence to restrictive RBC transfusion guidelines; however, changes were not sustained.

Citation: Yeh DD, Naraghi L, Larentzakis A, et al. Peer-to-peer physician feedback improves adherence to blood transfusion guidelines in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(1):65-70.

Clinical question: Can a multifaceted approach involving clinician education, peer email feedback, and monthly audit data improve adherence to restrictive red blood cell (RBC) transfusion guidelines?

Background: Randomized controlled trials and professional society guidelines support adoption of RBC transfusion strategies in stable, low-risk patients. Studies suggest that education and feedback from specialists may decrease inappropriate transfusion practices, but peer-to-peer feedback has not yet been explored.

Study design: Prospective, interventional study.

Setting: Tertiary care center SICU, single U.S. academic center.

Synopsis: All stable, low-risk SICU patients receiving RBC transfusions were included in this study. Intervention consisted of educational lectures to clinicians, dissemination of monthly aggregate audit transfusion data, and direct email feedback from a colleague to clinicians ordering transfusions outside of guidelines. Six-month intervention data were compared with six months of pre-intervention data.

During the intervention, total transfusions decreased by 36%, from 284 units to 181 units, and percentage of transfusions outside restrictive guidelines decreased to 2% from 25% (P<0.001). Six months after the end of the intervention period, transfusions outside restrictive guidelines increased back to 17%, suggesting a lack of permanent change in transfusion practices.

Bottom line: A multifaceted approach involving education, peer-to-peer feedback, and monthly audits improved adherence to restrictive RBC transfusion guidelines; however, changes were not sustained.

Citation: Yeh DD, Naraghi L, Larentzakis A, et al. Peer-to-peer physician feedback improves adherence to blood transfusion guidelines in the surgical intensive care unit. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2015;79(1):65-70.

Corticosteroids Improve Outcomes in Community- Acquired Pneumonia

Clinical question: Are adjunctive corticosteroids beneficial for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Numerous studies have tried to determine whether or not adjunctive corticosteroids for CAP treatment in hospitalized patients improve outcomes. Although recent trials have suggested that corticosteroids may improve morbidity and mortality, prior meta-analyses have failed to show a benefit, and steroids are not currently routinely recommended for this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, predominantly from Europe.

Synopsis: Analysis of 1,974 patients suggested a decrease in all-cause mortality (relative risk (RR) 0.67, 95% CI 0.45-1.01) with adjunctive corticosteroids. Subgroup analysis for severe CAP (six studies, n=388) suggested a greater mortality benefit (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.2-0.77). There was a decrease in the risk of mechanical ventilation (five studies, n=1060, RR 0.45, CI, 0.26-0.79), ICU admission (three studies, n=950, RR 0.69, 95% CI, 0.46-1.03), and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (four studies, n=945, RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10-0.56).

Both hospital length of stay (LOS) and time to clinical stability (hemodynamically stable with no hypoxia) were significantly decreased (mean decrease LOS one day; time to clinical stability 1.22 days). Adverse effects were rare but included increased rates of hyperglycemia requiring treatment (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.01-2.19). There was no increased frequency of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, neuropsychiatric complications, or rehospitalization.

Bottom line: Adjunctive corticosteroids for inpatient CAP treatment decrease morbidity and mortality, particularly in severe disease, and decrease LOS and time to clinical stability with few adverse reactions.

Citation: Siemieniuk RA, Meade MO, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):519-528.

Clinical question: Are adjunctive corticosteroids beneficial for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Numerous studies have tried to determine whether or not adjunctive corticosteroids for CAP treatment in hospitalized patients improve outcomes. Although recent trials have suggested that corticosteroids may improve morbidity and mortality, prior meta-analyses have failed to show a benefit, and steroids are not currently routinely recommended for this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, predominantly from Europe.

Synopsis: Analysis of 1,974 patients suggested a decrease in all-cause mortality (relative risk (RR) 0.67, 95% CI 0.45-1.01) with adjunctive corticosteroids. Subgroup analysis for severe CAP (six studies, n=388) suggested a greater mortality benefit (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.2-0.77). There was a decrease in the risk of mechanical ventilation (five studies, n=1060, RR 0.45, CI, 0.26-0.79), ICU admission (three studies, n=950, RR 0.69, 95% CI, 0.46-1.03), and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (four studies, n=945, RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10-0.56).

Both hospital length of stay (LOS) and time to clinical stability (hemodynamically stable with no hypoxia) were significantly decreased (mean decrease LOS one day; time to clinical stability 1.22 days). Adverse effects were rare but included increased rates of hyperglycemia requiring treatment (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.01-2.19). There was no increased frequency of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, neuropsychiatric complications, or rehospitalization.

Bottom line: Adjunctive corticosteroids for inpatient CAP treatment decrease morbidity and mortality, particularly in severe disease, and decrease LOS and time to clinical stability with few adverse reactions.

Citation: Siemieniuk RA, Meade MO, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):519-528.

Clinical question: Are adjunctive corticosteroids beneficial for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia (CAP)?

Background: Numerous studies have tried to determine whether or not adjunctive corticosteroids for CAP treatment in hospitalized patients improve outcomes. Although recent trials have suggested that corticosteroids may improve morbidity and mortality, prior meta-analyses have failed to show a benefit, and steroids are not currently routinely recommended for this population.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis of 13 RCTs, predominantly from Europe.

Synopsis: Analysis of 1,974 patients suggested a decrease in all-cause mortality (relative risk (RR) 0.67, 95% CI 0.45-1.01) with adjunctive corticosteroids. Subgroup analysis for severe CAP (six studies, n=388) suggested a greater mortality benefit (RR 0.39, 95% CI 0.2-0.77). There was a decrease in the risk of mechanical ventilation (five studies, n=1060, RR 0.45, CI, 0.26-0.79), ICU admission (three studies, n=950, RR 0.69, 95% CI, 0.46-1.03), and development of acute respiratory distress syndrome (four studies, n=945, RR 0.24, 95% CI 0.10-0.56).

Both hospital length of stay (LOS) and time to clinical stability (hemodynamically stable with no hypoxia) were significantly decreased (mean decrease LOS one day; time to clinical stability 1.22 days). Adverse effects were rare but included increased rates of hyperglycemia requiring treatment (RR 1.49, 95% CI 1.01-2.19). There was no increased frequency of gastrointestinal hemorrhage, neuropsychiatric complications, or rehospitalization.

Bottom line: Adjunctive corticosteroids for inpatient CAP treatment decrease morbidity and mortality, particularly in severe disease, and decrease LOS and time to clinical stability with few adverse reactions.

Citation: Siemieniuk RA, Meade MO, Alonso-Coello P, et al. Corticosteroid therapy for patients hospitalized with community-acquired pneumonia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163(7):519-528.

Standard Triple Therapy for H. Pylori Lowest Ranked among 14 Treatment Regimens

Clinical question: How do current Helicobacter pylori treatments compare in efficacy and tolerance?

Background: Efficacy of standard “triple therapy” for H. pylori (proton pump inhibitor plus clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole) is declining due to the development of antibiotic resistance. Different medication combinations and/or time courses are currently used, but comparative effectiveness of these treatments has not been evaluated comprehensively.

Study design: Systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Setting: Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Embase databases.

Synopsis: One hundred forty-three RCTs evaluating a total of 14 treatments for H. pylori were identified. Network meta-analysis was performed to rank order treatments for efficacy (eradication rate of H. pylori) and tolerance (adverse event occurrence rate). Seven days of “concomitant treatment” (proton pump inhibitor plus three antibiotics) ranked the highest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.89-0.98), though this treatment group comprised a very small proportion of overall participants and studies and may be subject to bias. Seven days of standard “triple therapy” ranked the lowest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.73; 95% CI 0.71-0.75).

Of note, subgroup analysis showed variation in efficacy rankings by geographic location, suggesting that findings may not be universally applicable. Only two treatments showed significantly different adverse event occurrence rates compared to standard “triple therapy,” indicating overall similar tolerance for most treatments.

Bottom line: Several treatment regimens may be more effective than standard H. pylori “triple therapy” and equally well tolerated.

Citation: Li BZ, Threapleton DE, Wang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness and tolerance of treatments for Helicobacter pylori: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h4052.

Clinical question: How do current Helicobacter pylori treatments compare in efficacy and tolerance?

Background: Efficacy of standard “triple therapy” for H. pylori (proton pump inhibitor plus clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole) is declining due to the development of antibiotic resistance. Different medication combinations and/or time courses are currently used, but comparative effectiveness of these treatments has not been evaluated comprehensively.

Study design: Systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Setting: Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Embase databases.

Synopsis: One hundred forty-three RCTs evaluating a total of 14 treatments for H. pylori were identified. Network meta-analysis was performed to rank order treatments for efficacy (eradication rate of H. pylori) and tolerance (adverse event occurrence rate). Seven days of “concomitant treatment” (proton pump inhibitor plus three antibiotics) ranked the highest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.89-0.98), though this treatment group comprised a very small proportion of overall participants and studies and may be subject to bias. Seven days of standard “triple therapy” ranked the lowest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.73; 95% CI 0.71-0.75).

Of note, subgroup analysis showed variation in efficacy rankings by geographic location, suggesting that findings may not be universally applicable. Only two treatments showed significantly different adverse event occurrence rates compared to standard “triple therapy,” indicating overall similar tolerance for most treatments.

Bottom line: Several treatment regimens may be more effective than standard H. pylori “triple therapy” and equally well tolerated.

Citation: Li BZ, Threapleton DE, Wang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness and tolerance of treatments for Helicobacter pylori: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h4052.

Clinical question: How do current Helicobacter pylori treatments compare in efficacy and tolerance?

Background: Efficacy of standard “triple therapy” for H. pylori (proton pump inhibitor plus clarithromycin and amoxicillin or metronidazole) is declining due to the development of antibiotic resistance. Different medication combinations and/or time courses are currently used, but comparative effectiveness of these treatments has not been evaluated comprehensively.

Study design: Systematic review and network meta-analysis.

Setting: Cochrane Library, PubMed, and Embase databases.

Synopsis: One hundred forty-three RCTs evaluating a total of 14 treatments for H. pylori were identified. Network meta-analysis was performed to rank order treatments for efficacy (eradication rate of H. pylori) and tolerance (adverse event occurrence rate). Seven days of “concomitant treatment” (proton pump inhibitor plus three antibiotics) ranked the highest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.94; 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.89-0.98), though this treatment group comprised a very small proportion of overall participants and studies and may be subject to bias. Seven days of standard “triple therapy” ranked the lowest in efficacy (eradication rate 0.73; 95% CI 0.71-0.75).

Of note, subgroup analysis showed variation in efficacy rankings by geographic location, suggesting that findings may not be universally applicable. Only two treatments showed significantly different adverse event occurrence rates compared to standard “triple therapy,” indicating overall similar tolerance for most treatments.

Bottom line: Several treatment regimens may be more effective than standard H. pylori “triple therapy” and equally well tolerated.

Citation: Li BZ, Threapleton DE, Wang JY, et al. Comparative effectiveness and tolerance of treatments for Helicobacter pylori: systematic review and network meta-analysis. BMJ. 2015;351:h4052.

Social Isolation, Polypharmacy Predict Medication Noncompliance Post-Discharge in Cardiac Patients

Clinical question: What are predictors of primary medication nonadherence after discharge?

Background: Primary nonadherence occurs when a patient receives a prescription at hospital discharge but does not fill it. Predictors of post-discharge primary nonadherence could serve as useful targets to guide adherence interventions.

Study design: RCT, secondary analysis.

Setting: Two tertiary care, U.S. academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study database, investigators conducted a secondary analysis of adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome or acute decompensated heart failure who received pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation, discharge counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and a follow-up phone call. The prevalence of primary nonadherence one to four days post-discharge was 9.4% among 341 patients. In subsequent multivariate analysis, significant factors for noncompliance were living alone (odds ratio 2.2, 95% CI 1.01-4.8, P=0.047) and more than 10 total discharge medications (odds ratio 2.3, 95% CI 1.05-4.98, P=0.036).

Limitations to this study include biases from patient-reported outcomes, lack of patient copayment data, and limited characterization of discharge medication type.

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized for cardiac events, social isolation and polypharmacy predict primary medication nonadherence to discharge medications despite intensive pharmacist counseling.

Citation: Wooldridge K, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, Dittus RS, Kripalani S. Refractory primary medication nonadherence: prevalence and predictors after pharmacist counseling at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print August 21, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2446.

Clinical question: What are predictors of primary medication nonadherence after discharge?

Background: Primary nonadherence occurs when a patient receives a prescription at hospital discharge but does not fill it. Predictors of post-discharge primary nonadherence could serve as useful targets to guide adherence interventions.

Study design: RCT, secondary analysis.

Setting: Two tertiary care, U.S. academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study database, investigators conducted a secondary analysis of adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome or acute decompensated heart failure who received pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation, discharge counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and a follow-up phone call. The prevalence of primary nonadherence one to four days post-discharge was 9.4% among 341 patients. In subsequent multivariate analysis, significant factors for noncompliance were living alone (odds ratio 2.2, 95% CI 1.01-4.8, P=0.047) and more than 10 total discharge medications (odds ratio 2.3, 95% CI 1.05-4.98, P=0.036).

Limitations to this study include biases from patient-reported outcomes, lack of patient copayment data, and limited characterization of discharge medication type.

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized for cardiac events, social isolation and polypharmacy predict primary medication nonadherence to discharge medications despite intensive pharmacist counseling.

Citation: Wooldridge K, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, Dittus RS, Kripalani S. Refractory primary medication nonadherence: prevalence and predictors after pharmacist counseling at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print August 21, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2446.

Clinical question: What are predictors of primary medication nonadherence after discharge?

Background: Primary nonadherence occurs when a patient receives a prescription at hospital discharge but does not fill it. Predictors of post-discharge primary nonadherence could serve as useful targets to guide adherence interventions.

Study design: RCT, secondary analysis.

Setting: Two tertiary care, U.S. academic hospitals.

Synopsis: Using the Pharmacist Intervention for Low Literacy in Cardiovascular Disease (PILL-CVD) study database, investigators conducted a secondary analysis of adults hospitalized for acute coronary syndrome or acute decompensated heart failure who received pharmacist-assisted medication reconciliation, discharge counseling, low-literacy adherence aids, and a follow-up phone call. The prevalence of primary nonadherence one to four days post-discharge was 9.4% among 341 patients. In subsequent multivariate analysis, significant factors for noncompliance were living alone (odds ratio 2.2, 95% CI 1.01-4.8, P=0.047) and more than 10 total discharge medications (odds ratio 2.3, 95% CI 1.05-4.98, P=0.036).

Limitations to this study include biases from patient-reported outcomes, lack of patient copayment data, and limited characterization of discharge medication type.

Bottom line: Among patients hospitalized for cardiac events, social isolation and polypharmacy predict primary medication nonadherence to discharge medications despite intensive pharmacist counseling.

Citation: Wooldridge K, Schnipper JL, Goggins K, Dittus RS, Kripalani S. Refractory primary medication nonadherence: prevalence and predictors after pharmacist counseling at hospital discharge [published online ahead of print August 21, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2446.

Inpatient Navigators Reduce Length of Stay without Increasing Readmissions

Clinical question: Does a patient navigator (PN) who facilitates communication between patients and providers impact hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmissions?

Background: Increasing complexity of hospitalization challenges the safety of care transitions. There are few studies about the effectiveness of innovations targeting both communication and transitional care planning.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Single academic health center in Canada, 2010-2014.

Synopsis: PNs, dedicated team-based facilitators not responsible for clinical care, served as liaisons between patients and providers on general medicine teams. They rounded with medical teams, tracked action items, expedited tests and consults, and proactively served as direct primary contacts for patients/families during and after hospitalization. PNs had no specified prior training; they underwent on-the-job training with regular feedback.

Researchers matched 7,841 hospitalizations (5,628 with PN; 2,213 without) by case mix, age, and resource intensity. LOS and 30-day readmissions were primary outcomes. Hospitalizations with PNs were 21% shorter (1.3 days; 6.2 v 7.5 days, P<0.001) than those without PNs.

There were no differences in 30-day readmission rates (13.1 v 13.8%, P=0.48). In this single center study in Canada, the impact of PN salaries (the only program cost) relative to savings is unknown.

Bottom line: Inpatient navigators streamline communication and decrease LOS without increasing readmissions. Additional cost-benefit analyses are needed.

Citation: Kwan JL, Morgan MW, Stewart TE, Bell CM. Impact of an innovative patient navigator program on length of stay and 30-day readmission [published online ahead of print August 10, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2442.

Clinical question: Does a patient navigator (PN) who facilitates communication between patients and providers impact hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmissions?

Background: Increasing complexity of hospitalization challenges the safety of care transitions. There are few studies about the effectiveness of innovations targeting both communication and transitional care planning.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Single academic health center in Canada, 2010-2014.

Synopsis: PNs, dedicated team-based facilitators not responsible for clinical care, served as liaisons between patients and providers on general medicine teams. They rounded with medical teams, tracked action items, expedited tests and consults, and proactively served as direct primary contacts for patients/families during and after hospitalization. PNs had no specified prior training; they underwent on-the-job training with regular feedback.

Researchers matched 7,841 hospitalizations (5,628 with PN; 2,213 without) by case mix, age, and resource intensity. LOS and 30-day readmissions were primary outcomes. Hospitalizations with PNs were 21% shorter (1.3 days; 6.2 v 7.5 days, P<0.001) than those without PNs.

There were no differences in 30-day readmission rates (13.1 v 13.8%, P=0.48). In this single center study in Canada, the impact of PN salaries (the only program cost) relative to savings is unknown.

Bottom line: Inpatient navigators streamline communication and decrease LOS without increasing readmissions. Additional cost-benefit analyses are needed.

Citation: Kwan JL, Morgan MW, Stewart TE, Bell CM. Impact of an innovative patient navigator program on length of stay and 30-day readmission [published online ahead of print August 10, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2442.

Clinical question: Does a patient navigator (PN) who facilitates communication between patients and providers impact hospital length of stay (LOS) and readmissions?

Background: Increasing complexity of hospitalization challenges the safety of care transitions. There are few studies about the effectiveness of innovations targeting both communication and transitional care planning.

Study design: Retrospective, cohort study.

Setting: Single academic health center in Canada, 2010-2014.

Synopsis: PNs, dedicated team-based facilitators not responsible for clinical care, served as liaisons between patients and providers on general medicine teams. They rounded with medical teams, tracked action items, expedited tests and consults, and proactively served as direct primary contacts for patients/families during and after hospitalization. PNs had no specified prior training; they underwent on-the-job training with regular feedback.

Researchers matched 7,841 hospitalizations (5,628 with PN; 2,213 without) by case mix, age, and resource intensity. LOS and 30-day readmissions were primary outcomes. Hospitalizations with PNs were 21% shorter (1.3 days; 6.2 v 7.5 days, P<0.001) than those without PNs.

There were no differences in 30-day readmission rates (13.1 v 13.8%, P=0.48). In this single center study in Canada, the impact of PN salaries (the only program cost) relative to savings is unknown.

Bottom line: Inpatient navigators streamline communication and decrease LOS without increasing readmissions. Additional cost-benefit analyses are needed.

Citation: Kwan JL, Morgan MW, Stewart TE, Bell CM. Impact of an innovative patient navigator program on length of stay and 30-day readmission [published online ahead of print August 10, 2015]. J Hosp Med. doi: 10.1002/jhm.2442.

Dexamethasone Potential Therapy for Asthma Exacerbations in Pediatric Inpatients

Clinical question: In children hospitalized in a non-ICU setting with asthma exacerbation, how effective is dexamethasone compared to prednisone/prednisolone?

Background: Asthma is the second most common reason for hospital admission in childhood.1 National guidelines recommend treatment with systemic corticosteroids in addition to beta-agonists.2 Traditionally, prednisone/prednisolone has been used for asthma exacerbations, but multiple recent studies in ED settings have shown equal efficacy with dexamethasone for mild to moderate exacerbations. Benefits of dexamethasone use include a longer half-life (so single dose or two-day courses can be used), good enteral absorption, general palatability, less emesis, and better adherence. To this point, no studies have compared dexamethasone with prednisone/prednisolone therapy in hospitalized children.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Freestanding, tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors used the PHIS (Pediatric Health Information System) database, which includes clinical and billing data from 42 children’s hospitals, to compare children who received dexamethasone to those who were treated with prednisone/prednisolone therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Patients were included if they were aged four to 17 years, were hospitalized between January 2007 and December 2012 with ICD-9 code for a principal diagnosis of asthma, and received either dexamethasone or prednisone/prednisolone.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Management in the ICU at the time of admission;

- All patient refined diagnosis related groups (APR-DRG) severity level moderate or extreme;

- Complex chronic conditions;

- Secondary diagnosis other than asthma requiring steroids, or treatment with racemic epinephrine;

- Only the first admission was included out of multiple hospitalizations within a 30-day period; and/or

- Patient was treated with both dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone.

The primary outcome evaluated was length of stay (LOS); secondary outcomes included readmissions, cost, and transfer to ICU during hospitalization. The authors compared the overall groups, then performed 1:1 propensity score matching to address residual confounding; this statistical technique closely matches patient characteristics between cohorts.

Overall, there were 40,257 hospitalizations, with 1,166 children (2.9%) receiving dexamethasone and 39,091 (97.1%) receiving prednisone/prednisolone. The use of dexamethasone varied greatly between hospitals (35/42 hospitals used dexamethasone, with rates ranging from 0.047% to 77.4%).

In the post-match cohort, 1,284 patients were evaluated, 642 in each group. In this cohort, patients with dexamethasone had significantly shorter LOS (67.4% had LOS less than one day vs. 59.5% in the prednisone/prednisolone group; 6.7% of dexamethasone patients had LOS of more than three days vs. 12% of prednisone/prednisolone patients). Costs were lower for the dexamethasone group, both for the index admission and for episode admission (defined as index admission plus seven-day readmissions). There was no difference in readmissions between the groups, and no patients in this cohort were transferred to the ICU.

There are several limitations to this study. Dexamethasone use varied widely among participating hospitals. The data source did not permit access to dosing, duration, or compliance with therapy and could not compare albuterol use between groups. The findings may not be generalizable to all populations, because it excluded patients with high severity and medical complexity and only evaluated tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Bottom line: Dexamethasone is a potential alternative therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Further studies are needed to evaluate effectiveness, including dosing, frequency, and duration.

Citation: Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.

References

- Yu H, Wier LM, Elixhauser A. Hospital stays for children, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #118. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2011. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–Summary Report 2007. Accessed November 1, 2015.

Clinical question: In children hospitalized in a non-ICU setting with asthma exacerbation, how effective is dexamethasone compared to prednisone/prednisolone?

Background: Asthma is the second most common reason for hospital admission in childhood.1 National guidelines recommend treatment with systemic corticosteroids in addition to beta-agonists.2 Traditionally, prednisone/prednisolone has been used for asthma exacerbations, but multiple recent studies in ED settings have shown equal efficacy with dexamethasone for mild to moderate exacerbations. Benefits of dexamethasone use include a longer half-life (so single dose or two-day courses can be used), good enteral absorption, general palatability, less emesis, and better adherence. To this point, no studies have compared dexamethasone with prednisone/prednisolone therapy in hospitalized children.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Freestanding, tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors used the PHIS (Pediatric Health Information System) database, which includes clinical and billing data from 42 children’s hospitals, to compare children who received dexamethasone to those who were treated with prednisone/prednisolone therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Patients were included if they were aged four to 17 years, were hospitalized between January 2007 and December 2012 with ICD-9 code for a principal diagnosis of asthma, and received either dexamethasone or prednisone/prednisolone.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Management in the ICU at the time of admission;

- All patient refined diagnosis related groups (APR-DRG) severity level moderate or extreme;

- Complex chronic conditions;

- Secondary diagnosis other than asthma requiring steroids, or treatment with racemic epinephrine;

- Only the first admission was included out of multiple hospitalizations within a 30-day period; and/or

- Patient was treated with both dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone.

The primary outcome evaluated was length of stay (LOS); secondary outcomes included readmissions, cost, and transfer to ICU during hospitalization. The authors compared the overall groups, then performed 1:1 propensity score matching to address residual confounding; this statistical technique closely matches patient characteristics between cohorts.

Overall, there were 40,257 hospitalizations, with 1,166 children (2.9%) receiving dexamethasone and 39,091 (97.1%) receiving prednisone/prednisolone. The use of dexamethasone varied greatly between hospitals (35/42 hospitals used dexamethasone, with rates ranging from 0.047% to 77.4%).

In the post-match cohort, 1,284 patients were evaluated, 642 in each group. In this cohort, patients with dexamethasone had significantly shorter LOS (67.4% had LOS less than one day vs. 59.5% in the prednisone/prednisolone group; 6.7% of dexamethasone patients had LOS of more than three days vs. 12% of prednisone/prednisolone patients). Costs were lower for the dexamethasone group, both for the index admission and for episode admission (defined as index admission plus seven-day readmissions). There was no difference in readmissions between the groups, and no patients in this cohort were transferred to the ICU.

There are several limitations to this study. Dexamethasone use varied widely among participating hospitals. The data source did not permit access to dosing, duration, or compliance with therapy and could not compare albuterol use between groups. The findings may not be generalizable to all populations, because it excluded patients with high severity and medical complexity and only evaluated tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Bottom line: Dexamethasone is a potential alternative therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Further studies are needed to evaluate effectiveness, including dosing, frequency, and duration.

Citation: Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.

References

- Yu H, Wier LM, Elixhauser A. Hospital stays for children, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #118. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2011. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–Summary Report 2007. Accessed November 1, 2015.

Clinical question: In children hospitalized in a non-ICU setting with asthma exacerbation, how effective is dexamethasone compared to prednisone/prednisolone?

Background: Asthma is the second most common reason for hospital admission in childhood.1 National guidelines recommend treatment with systemic corticosteroids in addition to beta-agonists.2 Traditionally, prednisone/prednisolone has been used for asthma exacerbations, but multiple recent studies in ED settings have shown equal efficacy with dexamethasone for mild to moderate exacerbations. Benefits of dexamethasone use include a longer half-life (so single dose or two-day courses can be used), good enteral absorption, general palatability, less emesis, and better adherence. To this point, no studies have compared dexamethasone with prednisone/prednisolone therapy in hospitalized children.

Study design: Multicenter, retrospective cohort study.

Setting: Freestanding, tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Synopsis: The authors used the PHIS (Pediatric Health Information System) database, which includes clinical and billing data from 42 children’s hospitals, to compare children who received dexamethasone to those who were treated with prednisone/prednisolone therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Patients were included if they were aged four to 17 years, were hospitalized between January 2007 and December 2012 with ICD-9 code for a principal diagnosis of asthma, and received either dexamethasone or prednisone/prednisolone.

Exclusion criteria included:

- Management in the ICU at the time of admission;

- All patient refined diagnosis related groups (APR-DRG) severity level moderate or extreme;

- Complex chronic conditions;

- Secondary diagnosis other than asthma requiring steroids, or treatment with racemic epinephrine;

- Only the first admission was included out of multiple hospitalizations within a 30-day period; and/or

- Patient was treated with both dexamethasone and prednisone/prednisolone.

The primary outcome evaluated was length of stay (LOS); secondary outcomes included readmissions, cost, and transfer to ICU during hospitalization. The authors compared the overall groups, then performed 1:1 propensity score matching to address residual confounding; this statistical technique closely matches patient characteristics between cohorts.

Overall, there were 40,257 hospitalizations, with 1,166 children (2.9%) receiving dexamethasone and 39,091 (97.1%) receiving prednisone/prednisolone. The use of dexamethasone varied greatly between hospitals (35/42 hospitals used dexamethasone, with rates ranging from 0.047% to 77.4%).

In the post-match cohort, 1,284 patients were evaluated, 642 in each group. In this cohort, patients with dexamethasone had significantly shorter LOS (67.4% had LOS less than one day vs. 59.5% in the prednisone/prednisolone group; 6.7% of dexamethasone patients had LOS of more than three days vs. 12% of prednisone/prednisolone patients). Costs were lower for the dexamethasone group, both for the index admission and for episode admission (defined as index admission plus seven-day readmissions). There was no difference in readmissions between the groups, and no patients in this cohort were transferred to the ICU.

There are several limitations to this study. Dexamethasone use varied widely among participating hospitals. The data source did not permit access to dosing, duration, or compliance with therapy and could not compare albuterol use between groups. The findings may not be generalizable to all populations, because it excluded patients with high severity and medical complexity and only evaluated tertiary care children’s hospitals.

Bottom line: Dexamethasone is a potential alternative therapy for asthma exacerbations in the inpatient setting. Further studies are needed to evaluate effectiveness, including dosing, frequency, and duration.

Citation: Parikh K, Hall M, Mittal V, et al. Comparative effectiveness of dexamethasone versus prednisone in children hospitalized with asthma. J Pediatr. 2015;167(3):639-644.

References

- Yu H, Wier LM, Elixhauser A. Hospital stays for children, 2009. HCUP statistical brief #118. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. August 2011. Accessed November 1, 2015.

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. National Asthma Education and Prevention Program expert panel report 3 (EPR-3): guidelines for the diagnosis and management of asthma–Summary Report 2007. Accessed November 1, 2015.

What Are the Strategies for Secondary Stroke Prevention after Transient Ischemic Attack?

Case

Mr. G is an 80-year-old man with a pacemaker, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin, and tachy-brady syndrome. He presented after experiencing episodes in which he was unable to speak and had weakness on his right side. He had a normal neurological exam upon arrival to the ED, and his blood pressure was 160/80 mm Hg.

Overview

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are brief interruptions in brain perfusion that do not result in permanent neurologic damage. Up to half a million TIAs occur each year in the U.S., and they account for one third of acute cerebrovascular disease.1 While the term suggests that TIAs are benign, they are in fact an important warning sign of impending stroke and are essentially analogous to unstable angina. Some 10% of TIAs convert to full strokes within 90 days, but growing evidence suggests appropriate interventions can decrease this risk to 3%.2

Unfortunately, the symptoms of TIA have usually resolved by the time patients arrive at the hospital, which makes them challenging to diagnose. This article provides a summary of how to diagnose TIA accurately, using a focused history informed by cerebrovascular localization; how to triage, evaluate, and risk stratify patients; and how to implement preventative strategies.

Review of the Data

Classically, TIAs are defined as lasting less than 24 hours; however, 24 hours is an arbitrary number, and most TIAs last less than one hour.1 Furthermore, this definition has evolved with advances in neuroimaging that reveal that up to 50% of classically defined TIAs have evidence of infarct on MRI.1 There is no absolute temporal cut-off after which infarct is always seen on MRI, but longer duration of symptoms correlates with a higher likelihood of infarct. To reconcile these observations, a recently proposed definition stipulates that a true TIA lasts no more than one hour and does not show evidence of infarct on MRI.3

The causes of TIA are identical to those for ischemic stroke. Cerebral ischemia can result from an embolus, arterial thrombosis, or hypoperfusion due to arterial stenosis. Emboli can be cardiac, most commonly due to AF, or non-cardiac, stemming from a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic arch, the carotid or vertebral artery, or an intracranial vessel. Atherosclerotic disease in the carotid arteries or intracranial vessels can also lead to thrombosis and occlusion or flow-related TIAs as a result of severe stenosis.

Risk factors for TIA mirror those for heart disease. Non-modifiable risk factors include older age, black race, male sex, and family history of stroke. Modifiable factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco smoking, diabetes, and AF.4

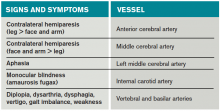

Most of the time, patients’ symptoms will have resolved by the time they are evaluated by a physician. Therefore, the diagnosis of TIA relies almost exclusively on the patient history. Eliciting a good history helps physicians determine whether the episode of transient neurologic dysfunction was caused by cerebral ischemia, as opposed to another mechanism, such as migraine or seizure. This calls for a basic understanding of cerebrovascular anatomy (see Table 1).

Types of Ischemia

Anterior cerebral artery ischemia causes contralateral leg weakness because it supplies the medial frontal and parietal lobes, where the legs in the sensorimotor homunculus are represented. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemia causes contralateral face and arm weakness out of proportion to leg weakness. Ischemia in Broca’s area of the brain, which is supplied by the left MCA, may also cause expressive aphasia. Transient monocular blindness is a TIA of the retina due to atheroemboli originating from the internal carotid artery. Vertebrobasilar TIA is less common than anterior circulation TIA and manifests with brainstem symptoms that include diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, vertigo, gait imbalance, and weakness. In general, language and motor symptoms are more specific for cerebral ischemia and therefore more worrisome for TIA than sensory symptoms.5

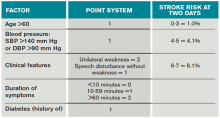

Once a clinical diagnosis of TIA is made, an ABCD2 score (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, presence of diabetes) can be used to predict the short-term risk of subsequent stroke (see Table 2).6,7 A general rule of thumb is to admit patients who present within 72 hours of the event and have an ABCD2 score of three or higher for observation, work-up, and initiation of secondary prevention.1

Although only a small percentage of patients with TIA will have a stroke during the period of observation in the hospital, this approach may be cost effective based on the assumption that hospitalized patients are more likely to receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator.8 The decision should also be guided by clinical judgment. It is reasonable to admit a patient whose diagnostic workup cannot be rapidly completed.1

The workup for TIA includes routine labs, EKG with cardiac monitoring, and brain imaging. Labs are useful to evaluate for other mimics of TIA such as hyponatremia and glucose abnormalities. In addition, risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes should be evaluated with fasting lipid panel and blood glucose. The purpose of EKG and telemetry is to identify MI and capture paroxysmal AF. The goal of imaging is to ascertain the presence of vascular disease and to exclude a non-ischemic etiology. While less likely to cause transient neurologic symptoms, a hemorrhagic event must be ruled out, as it would trigger a different management pathway.

Imaging for TIA

There are two primary modes of brain imaging: computed tomography (CT) and MRI. Most patients who are suspected to have had a TIA undergo CT scan, and an infarct is seen about 20% of the time.1 The presence of an infarct usually correlates with the duration of symptoms and has prognostic value. In one study, a new infarct was associated with four times higher risk of stroke in the subsequent 90 days.9 Diffusion-weighted imaging, an MR-based technique, is the preferred modality when it is available because of its higher sensitivity and specificity for identifying acute lesions.1 In an international and multicenter study, incorporating imaging data increased the discriminatory power of stroke prediction.10

Extracranial imaging is mandatory to rule out carotid stenosis as a potential etiology of TIA. The least invasive modality is ultrasound, which can detect carotid stenosis with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 80%.1 While both the intra- and extracranial vasculature can be concurrently assessed using MR- or CT-angiography (CTA), this is not usually necessary in the acute setting, because only detecting carotid stenosis will result in a management change.1

Carotid endarterectomy is standard for symptomatic patients with greater than 70% stenosis and is a consideration for symptomatic patients with greater than 50% stenosis if it is the most probable explanation for the ischemic event.11 Despite a comprehensive workup, about 50% of TIA cases remain cryptogenic.12 In some of these patients, AF can be detected using extended ambulatory cardiac monitoring.12

The goal of admitting high-risk patients is to expedite workup and initiate therapy. Two studies have shown that immediate initiation of preventative treatment significantly reduces the risk of stroke by as much as 80%.13,14 Unless there is a specific indication for anticoagulation, all TIA patients should be started on an antiplatelet agent such as aspirin or clopidogrel. A large randomized trial conducted in China and published in 2013 demonstrated that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 21 days, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy, reduced the risk of stroke compared to aspirin monotherapy. An international multicenter trial designed to test the efficacy of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy is ongoing, and if the benefit of this approach is confirmed, this will likely become the standard of care. Evidence-based indications for anticoagulation after TIA are restricted to AF and mural thrombus in the setting of recent MI. Patients with implanted mechanical devices, including left ventricular assist devices and metal heart valves, should also receive anticoagulation.15

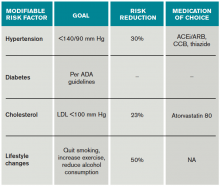

Risk factors should also be targeted in every case. Hypertension should be treated with a goal of lower than 140/90 mm Hg (or 130/80 mm Hg in diabetics and those with renal disease). Studies have shown that patients who are discharged with a blood pressure lower than 140/90 mm Hg are more likely to maintain this blood pressure at one-year follow-up.16 The choice of medication is less well studied, but drugs that act on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and thiazides are generally preferred.15 Treatment with a statin is recommended after cerebrovascular ischemic events, with a goal LDL under 100. This reduces risk of secondary stroke by about 20%.17

At discharge, it is also important to counsel patients on their role in preventing strokes. As with many diseases, making lifestyle changes is key to stroke prevention. Encourage smoking cessation and an increase in physical activity, and discourage heavy alcohol use. The association between smoking and the risk for first stroke is well established. Moderate to high-intensity exercise can reduce secondary stroke risk by as much as 50%18 (see Table 3). While light alcohol consumption can be protective against strokes, heavy use is strongly discouraged. Emerging data suggest obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be another modifiable risk factor for stroke and TIA, so screening for potential OSA and referral may be needed.15

Back to the Case

When Mr. G arrived at the ED, his symptoms had resolved. Based on the history of expressive aphasia and right-sided weakness, he most likely had a TIA in the left MCA territory. Hemorrhage was ruled out with a non-contrast head CT. His pacemaker precluded obtaining an MRI. CTA revealed diffuse atherosclerotic disease without evidence of carotid stenosis. His ABCD2 score was six given his age, blood pressure, weakness, and symptom duration, and he was admitted for an expedited workup. His sodium and glucose were within normal limits. His hemoglobin A1c was 6.5%, his LDL was 120, and his international normalized ratio (INR) was therapeutic at 2.1. His TIA may have been due to AF, despite a therapeutic INR, because warfarin does not fully eliminate the stroke risk. It might also have been caused by intracranial atherosclerosis.

Two days later, the patient was discharged on atorvastatin at 80 mg, and his lisinopril was increased for blood pressure control. For his age group, A1c of 6.5% was acceptable, and he was not initiated on glycemic control.

Bottom Line

TIAs are diagnosed based on patient history. Urgent initiation of secondary prevention is important to reduce the short-term risk of stroke and should be implemented by the time of discharge from the hospital.

Dr. Zeng is a hospitalist in the department of internal medicine at Vanderbilt University Medical Center in Nashville, and Dr. Douglas is associate professor in the department of neurology at the University of California at San Francisco.

References

- Easton JD, Saver JL, Albers GW, et al. Definition and evaluation of transient ischemic attack: a scientific statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association Stroke Council; Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia; Council on Cardiovascular Radiology and Intervention; Council on Cardiovascular Nursing; and the Interdisciplinary Council on Peripheral Vascular Disease. The American Academy of Neurology affirms the value of this statement as an educational tool for neurologists. Stroke. 2009;40(6):2276-2293.

- Sundararajan V, Thrift AG, Phan TG, Choi PM, Clissold B, Srikanth VK. Trends over time in the risk of stroke after an incident transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2014;45(11):3214-3218.

- Albers GW, Caplan LR, Easton JD, et al. Transient ischemic attack–proposal for a new definition. N Engl J Med. 2002;347(21):1713-1716.

- Grysiewicz RA, Thomas K, Pandey DK. Epidemiology of ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke: incidence, prevalence, mortality, and risk factors. Neurol Clin. 2008;26(4):871-895, vii.

- Johnston SC, Sidney S, Bernstein AL, Gress DR. A comparison of risk factors for recurrent TIA and stroke in patients diagnosed with TIA. Neurology. 2003;60(2):280-285.

- Tsivgoulis G, Stamboulis E, Sharma VK, et al. Multicenter external validation of the ABCD2 score in triaging TIA patients. Neurology. 2010;74(17):1351-1357.

- Johnston SC, Rothwell PM, Nguyen-Huynh MN, et al. Validation and refinement of scores to predict very early stroke risk after transient ischaemic attack. Lancet. 2007;369(9558):283-292.

- Nguyen-Huynh MN, Johnston SC. Is hospitalization after TIA cost-effective on the basis of treatment with tPA? Neurology. 2005;65(11):1799-1801.

- Douglas VC, Johnston CM, Elkins J, Sidney S, Gress DR, Johnston SC. Head computed tomography findings predict short-term stroke risk after transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 2003;34(12):2894-2898.

- Giles MF, Albers GW, Amarenco P, et al. Addition of brain infarction to the ABCD2 Score (ABCD2I): a collaborative analysis of unpublished data on 4574 patients. Stroke. 2010;41(9):1907-1913.

- Lanzino G, Rabinstein AA, Brown RD Jr. Treatment of carotid artery stenosis: medical therapy, surgery, or stenting? Mayo Clin Proc. 2009;84(4):362-387; quiz 367-368.

- Gladstone DJ, Spring M, Dorian P, et al. Atrial fibrillation in patients with cryptogenic stroke. N Engl J Med. 2014;370(26):2467-2477.

- Lavallée PC, Meseguer E, Abboud H, et al. A transient ischaemic attack clinic with round-the-clock access (SOS-TIA): feasibility and effects. Lancet Neurol. 2007;6(11):953-960.

- Rothwell PM, Giles MF, Chandratheva A, et al. Effect of urgent treatment of transient ischaemic attack and minor stroke on early recurrent stroke (EXPRESS study): a prospective population-based sequential comparison. Lancet. 2007;370(9596):1432-1442.

- Kernan WN, Ovbiagele B, Black HR, et al. Guidelines for the prevention of stroke in patients with stroke and transient ischemic attack: a guideline for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/American Stroke Association. Stroke. 2014;45(7):2160-2236.

- Roumie CL, Zillich AJ, Bravata DM, et al. Hypertension treatment intensification among stroke survivors with uncontrolled blood pressure. Stroke. 2015;46(2):465-470.

- Amarenco P, Bogousslavsky J, Callahan A, et al. High-dose atorvastatin after stroke or transient ischemic attack. N Engl J Med. 2006;355(6):549-559.

- Lennon O, Galvin R, Smith K, Doody C, Blake C. Lifestyle interventions for secondary disease prevention in stroke and transient ischaemic attack: a systematic review. Eur J Prev Cardiol. 2014;21(8):1026-1039.

Case

Mr. G is an 80-year-old man with a pacemaker, peripheral artery disease, atrial fibrillation (AF) on warfarin, and tachy-brady syndrome. He presented after experiencing episodes in which he was unable to speak and had weakness on his right side. He had a normal neurological exam upon arrival to the ED, and his blood pressure was 160/80 mm Hg.

Overview

Transient ischemic attacks (TIAs) are brief interruptions in brain perfusion that do not result in permanent neurologic damage. Up to half a million TIAs occur each year in the U.S., and they account for one third of acute cerebrovascular disease.1 While the term suggests that TIAs are benign, they are in fact an important warning sign of impending stroke and are essentially analogous to unstable angina. Some 10% of TIAs convert to full strokes within 90 days, but growing evidence suggests appropriate interventions can decrease this risk to 3%.2

Unfortunately, the symptoms of TIA have usually resolved by the time patients arrive at the hospital, which makes them challenging to diagnose. This article provides a summary of how to diagnose TIA accurately, using a focused history informed by cerebrovascular localization; how to triage, evaluate, and risk stratify patients; and how to implement preventative strategies.

Review of the Data

Classically, TIAs are defined as lasting less than 24 hours; however, 24 hours is an arbitrary number, and most TIAs last less than one hour.1 Furthermore, this definition has evolved with advances in neuroimaging that reveal that up to 50% of classically defined TIAs have evidence of infarct on MRI.1 There is no absolute temporal cut-off after which infarct is always seen on MRI, but longer duration of symptoms correlates with a higher likelihood of infarct. To reconcile these observations, a recently proposed definition stipulates that a true TIA lasts no more than one hour and does not show evidence of infarct on MRI.3

The causes of TIA are identical to those for ischemic stroke. Cerebral ischemia can result from an embolus, arterial thrombosis, or hypoperfusion due to arterial stenosis. Emboli can be cardiac, most commonly due to AF, or non-cardiac, stemming from a ruptured atherosclerotic plaque in the aortic arch, the carotid or vertebral artery, or an intracranial vessel. Atherosclerotic disease in the carotid arteries or intracranial vessels can also lead to thrombosis and occlusion or flow-related TIAs as a result of severe stenosis.

Risk factors for TIA mirror those for heart disease. Non-modifiable risk factors include older age, black race, male sex, and family history of stroke. Modifiable factors include hypertension, hyperlipidemia, tobacco smoking, diabetes, and AF.4

Most of the time, patients’ symptoms will have resolved by the time they are evaluated by a physician. Therefore, the diagnosis of TIA relies almost exclusively on the patient history. Eliciting a good history helps physicians determine whether the episode of transient neurologic dysfunction was caused by cerebral ischemia, as opposed to another mechanism, such as migraine or seizure. This calls for a basic understanding of cerebrovascular anatomy (see Table 1).

Types of Ischemia

Anterior cerebral artery ischemia causes contralateral leg weakness because it supplies the medial frontal and parietal lobes, where the legs in the sensorimotor homunculus are represented. Middle cerebral artery (MCA) ischemia causes contralateral face and arm weakness out of proportion to leg weakness. Ischemia in Broca’s area of the brain, which is supplied by the left MCA, may also cause expressive aphasia. Transient monocular blindness is a TIA of the retina due to atheroemboli originating from the internal carotid artery. Vertebrobasilar TIA is less common than anterior circulation TIA and manifests with brainstem symptoms that include diplopia, dysarthria, dysphagia, vertigo, gait imbalance, and weakness. In general, language and motor symptoms are more specific for cerebral ischemia and therefore more worrisome for TIA than sensory symptoms.5

Once a clinical diagnosis of TIA is made, an ABCD2 score (age, blood pressure, clinical features, duration of TIA, presence of diabetes) can be used to predict the short-term risk of subsequent stroke (see Table 2).6,7 A general rule of thumb is to admit patients who present within 72 hours of the event and have an ABCD2 score of three or higher for observation, work-up, and initiation of secondary prevention.1

Although only a small percentage of patients with TIA will have a stroke during the period of observation in the hospital, this approach may be cost effective based on the assumption that hospitalized patients are more likely to receive intravenous tissue plasminogen activator.8 The decision should also be guided by clinical judgment. It is reasonable to admit a patient whose diagnostic workup cannot be rapidly completed.1

The workup for TIA includes routine labs, EKG with cardiac monitoring, and brain imaging. Labs are useful to evaluate for other mimics of TIA such as hyponatremia and glucose abnormalities. In addition, risk factors such as hyperlipidemia and diabetes should be evaluated with fasting lipid panel and blood glucose. The purpose of EKG and telemetry is to identify MI and capture paroxysmal AF. The goal of imaging is to ascertain the presence of vascular disease and to exclude a non-ischemic etiology. While less likely to cause transient neurologic symptoms, a hemorrhagic event must be ruled out, as it would trigger a different management pathway.

Imaging for TIA

There are two primary modes of brain imaging: computed tomography (CT) and MRI. Most patients who are suspected to have had a TIA undergo CT scan, and an infarct is seen about 20% of the time.1 The presence of an infarct usually correlates with the duration of symptoms and has prognostic value. In one study, a new infarct was associated with four times higher risk of stroke in the subsequent 90 days.9 Diffusion-weighted imaging, an MR-based technique, is the preferred modality when it is available because of its higher sensitivity and specificity for identifying acute lesions.1 In an international and multicenter study, incorporating imaging data increased the discriminatory power of stroke prediction.10

Extracranial imaging is mandatory to rule out carotid stenosis as a potential etiology of TIA. The least invasive modality is ultrasound, which can detect carotid stenosis with a sensitivity and specificity approaching 80%.1 While both the intra- and extracranial vasculature can be concurrently assessed using MR- or CT-angiography (CTA), this is not usually necessary in the acute setting, because only detecting carotid stenosis will result in a management change.1

Carotid endarterectomy is standard for symptomatic patients with greater than 70% stenosis and is a consideration for symptomatic patients with greater than 50% stenosis if it is the most probable explanation for the ischemic event.11 Despite a comprehensive workup, about 50% of TIA cases remain cryptogenic.12 In some of these patients, AF can be detected using extended ambulatory cardiac monitoring.12

The goal of admitting high-risk patients is to expedite workup and initiate therapy. Two studies have shown that immediate initiation of preventative treatment significantly reduces the risk of stroke by as much as 80%.13,14 Unless there is a specific indication for anticoagulation, all TIA patients should be started on an antiplatelet agent such as aspirin or clopidogrel. A large randomized trial conducted in China and published in 2013 demonstrated that dual antiplatelet therapy with aspirin and clopidogrel for 21 days, followed by clopidogrel monotherapy, reduced the risk of stroke compared to aspirin monotherapy. An international multicenter trial designed to test the efficacy of short-term dual antiplatelet therapy is ongoing, and if the benefit of this approach is confirmed, this will likely become the standard of care. Evidence-based indications for anticoagulation after TIA are restricted to AF and mural thrombus in the setting of recent MI. Patients with implanted mechanical devices, including left ventricular assist devices and metal heart valves, should also receive anticoagulation.15

Risk factors should also be targeted in every case. Hypertension should be treated with a goal of lower than 140/90 mm Hg (or 130/80 mm Hg in diabetics and those with renal disease). Studies have shown that patients who are discharged with a blood pressure lower than 140/90 mm Hg are more likely to maintain this blood pressure at one-year follow-up.16 The choice of medication is less well studied, but drugs that act on the renin-angiotensin-aldosterone system and thiazides are generally preferred.15 Treatment with a statin is recommended after cerebrovascular ischemic events, with a goal LDL under 100. This reduces risk of secondary stroke by about 20%.17

At discharge, it is also important to counsel patients on their role in preventing strokes. As with many diseases, making lifestyle changes is key to stroke prevention. Encourage smoking cessation and an increase in physical activity, and discourage heavy alcohol use. The association between smoking and the risk for first stroke is well established. Moderate to high-intensity exercise can reduce secondary stroke risk by as much as 50%18 (see Table 3). While light alcohol consumption can be protective against strokes, heavy use is strongly discouraged. Emerging data suggest obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) may be another modifiable risk factor for stroke and TIA, so screening for potential OSA and referral may be needed.15

Back to the Case