User login

ACIP weighs in on meningococcal B vaccines

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted at its June 2015 meeting to make a “B” recommendation for the use of meningococcal B vaccine for individuals 16 through 23 years of age. The Committee felt that the vaccine can be used if one desires it, but at this time it should not be included in the category of a routinely recommended vaccine.

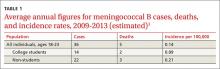

Meningococcal meningitis caused by serogroup B is a serious disease, but it is rare. From 2009 to 2013, the annual number of meningococcal B cases in individuals ages 11 to 24 years ranged from 54 to 67, with 5 to 10 deaths and 5 to 13 serious sequelae.1 Since 2009, there have been outbreaks on 7 university campuses with cases-per-outbreak numbering 2 to 13.1 These well publicized outbreaks created much disruption and an impression of increased risk among college students. But the surveillance system of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) demonstrates that the rate of infection among college students is actually lower than it is among individuals the same age who are not in college (TABLE 1).1

The combined incidence of 0.14/100,000 means that to prevent one case, 714,000 individuals need to be vaccinated; 5 million need to be vaccinated to prevent one death.1 These numbers are subject to yearly variation and would be more favorable should the incidence of the disease increase. (For a look at the historical incidence of meningococcal meningitis from all serotypes, see the FIGURE.1) The question facing ACIP was whether the current very low levels of meningococcal B disease merit widespread, routinely-recommended use of the vaccine.

A look at the 2 meningococcal B vaccines

Two meningococcal B vaccines are now licensed for use in the United States. MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Pfizer) was licensed in October 2014 as a 3-dose series given at 0, 2, and 6 months.2 MenB-4C (Bexsero, Novartis/GSK) was licensed in January 2015 and requires 2 doses at 0 and ≥1 month.3 Both vaccines induce a level of antibody production that is considered immunogenic in a high proportion of those vaccinated, but the level of immunity wanes after 6 to 24 months. The clinical significance of this drop in immunity is unknown and cannot be tested currently because of the rarity of the disease. Unfortunately, the rate of asymptomatic carriage of meningococcal B does not appear to be affected by vaccination.1

Both vaccines produce local and systemic reactions at rates higher than other recommended vaccines for this age group: pain at the injection site (83%-85%), headache (33%-35%), myalgia (30%-48%), fatigue (35%-40%), induration (28%), nausea (18%), chills (15%), and arthralgia (13%).2,3 There is some theoretical concern about the potential for autoimmune disease from the use of meningococcal B vaccines that will be studied as the vaccines are used more widely.1 In addition, the CDC estimates that serious anaphylactic reactions can occur after administration of any vaccine, estimated at about one per every million doses.1

Meningococcal serotype B bacteria consist of different strains. The 2 approved vaccines cover today’s most frequently found strains in the United States, but it’s uncertain if this will hold true in the future.

USPSTF: Screen obese/overweight adults for type 2 diabetes

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its recommendation for screening for type 2 diabetes in adults. USPSTF recommends screening adults, ages 40 to 70 years, who are obese or overweight and referring those who have abnormal blood glucose to intensive behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity.

The Task Force gave this recommendation a grade of B, meaning that it is likely to result in a moderate level of benefit from a reduction in progression to diabetes. The Task Force also emphasized that lifestyle modifications have a greater risk-reducing effect than metformin and other medications.

The recommendation rationale points out that screening might also benefit those at high risk of diabetes based on family history or race/ethnicity and does not apply to those with signs and symptoms of diabetes; testing in this latter group is considered diagnostic testing, not screening.

Screening can be done by measuring glycated hemoglobin A1c or fasting glucose or with a glucose tolerance test. The recommendation includes tables that list the cutoffs for abnormal glucose levels for impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased average glucose level. Obesity is defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and overweight as >25 kg/m2.

This new recommendation expands the list of those at risk and those who should be screened compared to the previous recommendation, but the Task Force found no evidence to support universal screening in adults as advocated by other organizations.

Source: USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed November 13, 2015.

Recommendation considerations that came into play

A number of factors affected ACIP’s recommendation decision: the low incidence of the meningococcal B disease; the large number-needed-to-vaccinate to prevent a case and a death; uncertainties regarding the duration of protection; cost, lack of effect on carriage rates, and limited safety data with the potential for serious reactions to exceed the number of cases prevented; and the severity of the disease and the concern it elicits.

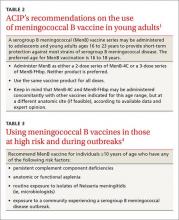

ACIP has multiple options when considering a vaccine: recommend it routinely for everyone or everyone in a defined group (A recommendation), recommend for individual decision making (B recommendation), recommend against use, and make no recommendation at all. Given that 2 meningococcal B vaccines are licensed in the United States and can be used by those who want them—and the Committee’s opinion that these vaccines should not (at this time) be included in the schedule of routinely-recommended vaccines—ACIP chose to make a B recommendation on their use (TABLE 2).1 Vaccines recommended by ACIP (both A and B recommendations) are mandated in the Affordable Care Act to be provided by commercial health insurance at no out-of-pocket expense to the patient.

A word about high-risk populations

At its February 2015 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend meningococcal B vaccine for use in high-risk populations and during outbreaks (TABLE 3).4 This recommendation—plus the most recent B recommendation for general use—comprise the totality of current recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal B disease in the United States.

1. MacNeil J. Considerations for the use of serogroup B meningococcal (MenB) vaccines in adolescents. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 24, 2015; Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2015-06/mening-03-macneil.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

2. Trumenba [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Pfizer); 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM421139.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

3. Bexsero [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics Inc; 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM431447.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

4. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted at its June 2015 meeting to make a “B” recommendation for the use of meningococcal B vaccine for individuals 16 through 23 years of age. The Committee felt that the vaccine can be used if one desires it, but at this time it should not be included in the category of a routinely recommended vaccine.

Meningococcal meningitis caused by serogroup B is a serious disease, but it is rare. From 2009 to 2013, the annual number of meningococcal B cases in individuals ages 11 to 24 years ranged from 54 to 67, with 5 to 10 deaths and 5 to 13 serious sequelae.1 Since 2009, there have been outbreaks on 7 university campuses with cases-per-outbreak numbering 2 to 13.1 These well publicized outbreaks created much disruption and an impression of increased risk among college students. But the surveillance system of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) demonstrates that the rate of infection among college students is actually lower than it is among individuals the same age who are not in college (TABLE 1).1

The combined incidence of 0.14/100,000 means that to prevent one case, 714,000 individuals need to be vaccinated; 5 million need to be vaccinated to prevent one death.1 These numbers are subject to yearly variation and would be more favorable should the incidence of the disease increase. (For a look at the historical incidence of meningococcal meningitis from all serotypes, see the FIGURE.1) The question facing ACIP was whether the current very low levels of meningococcal B disease merit widespread, routinely-recommended use of the vaccine.

A look at the 2 meningococcal B vaccines

Two meningococcal B vaccines are now licensed for use in the United States. MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Pfizer) was licensed in October 2014 as a 3-dose series given at 0, 2, and 6 months.2 MenB-4C (Bexsero, Novartis/GSK) was licensed in January 2015 and requires 2 doses at 0 and ≥1 month.3 Both vaccines induce a level of antibody production that is considered immunogenic in a high proportion of those vaccinated, but the level of immunity wanes after 6 to 24 months. The clinical significance of this drop in immunity is unknown and cannot be tested currently because of the rarity of the disease. Unfortunately, the rate of asymptomatic carriage of meningococcal B does not appear to be affected by vaccination.1

Both vaccines produce local and systemic reactions at rates higher than other recommended vaccines for this age group: pain at the injection site (83%-85%), headache (33%-35%), myalgia (30%-48%), fatigue (35%-40%), induration (28%), nausea (18%), chills (15%), and arthralgia (13%).2,3 There is some theoretical concern about the potential for autoimmune disease from the use of meningococcal B vaccines that will be studied as the vaccines are used more widely.1 In addition, the CDC estimates that serious anaphylactic reactions can occur after administration of any vaccine, estimated at about one per every million doses.1

Meningococcal serotype B bacteria consist of different strains. The 2 approved vaccines cover today’s most frequently found strains in the United States, but it’s uncertain if this will hold true in the future.

USPSTF: Screen obese/overweight adults for type 2 diabetes

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its recommendation for screening for type 2 diabetes in adults. USPSTF recommends screening adults, ages 40 to 70 years, who are obese or overweight and referring those who have abnormal blood glucose to intensive behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity.

The Task Force gave this recommendation a grade of B, meaning that it is likely to result in a moderate level of benefit from a reduction in progression to diabetes. The Task Force also emphasized that lifestyle modifications have a greater risk-reducing effect than metformin and other medications.

The recommendation rationale points out that screening might also benefit those at high risk of diabetes based on family history or race/ethnicity and does not apply to those with signs and symptoms of diabetes; testing in this latter group is considered diagnostic testing, not screening.

Screening can be done by measuring glycated hemoglobin A1c or fasting glucose or with a glucose tolerance test. The recommendation includes tables that list the cutoffs for abnormal glucose levels for impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased average glucose level. Obesity is defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and overweight as >25 kg/m2.

This new recommendation expands the list of those at risk and those who should be screened compared to the previous recommendation, but the Task Force found no evidence to support universal screening in adults as advocated by other organizations.

Source: USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed November 13, 2015.

Recommendation considerations that came into play

A number of factors affected ACIP’s recommendation decision: the low incidence of the meningococcal B disease; the large number-needed-to-vaccinate to prevent a case and a death; uncertainties regarding the duration of protection; cost, lack of effect on carriage rates, and limited safety data with the potential for serious reactions to exceed the number of cases prevented; and the severity of the disease and the concern it elicits.

ACIP has multiple options when considering a vaccine: recommend it routinely for everyone or everyone in a defined group (A recommendation), recommend for individual decision making (B recommendation), recommend against use, and make no recommendation at all. Given that 2 meningococcal B vaccines are licensed in the United States and can be used by those who want them—and the Committee’s opinion that these vaccines should not (at this time) be included in the schedule of routinely-recommended vaccines—ACIP chose to make a B recommendation on their use (TABLE 2).1 Vaccines recommended by ACIP (both A and B recommendations) are mandated in the Affordable Care Act to be provided by commercial health insurance at no out-of-pocket expense to the patient.

A word about high-risk populations

At its February 2015 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend meningococcal B vaccine for use in high-risk populations and during outbreaks (TABLE 3).4 This recommendation—plus the most recent B recommendation for general use—comprise the totality of current recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal B disease in the United States.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) voted at its June 2015 meeting to make a “B” recommendation for the use of meningococcal B vaccine for individuals 16 through 23 years of age. The Committee felt that the vaccine can be used if one desires it, but at this time it should not be included in the category of a routinely recommended vaccine.

Meningococcal meningitis caused by serogroup B is a serious disease, but it is rare. From 2009 to 2013, the annual number of meningococcal B cases in individuals ages 11 to 24 years ranged from 54 to 67, with 5 to 10 deaths and 5 to 13 serious sequelae.1 Since 2009, there have been outbreaks on 7 university campuses with cases-per-outbreak numbering 2 to 13.1 These well publicized outbreaks created much disruption and an impression of increased risk among college students. But the surveillance system of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) demonstrates that the rate of infection among college students is actually lower than it is among individuals the same age who are not in college (TABLE 1).1

The combined incidence of 0.14/100,000 means that to prevent one case, 714,000 individuals need to be vaccinated; 5 million need to be vaccinated to prevent one death.1 These numbers are subject to yearly variation and would be more favorable should the incidence of the disease increase. (For a look at the historical incidence of meningococcal meningitis from all serotypes, see the FIGURE.1) The question facing ACIP was whether the current very low levels of meningococcal B disease merit widespread, routinely-recommended use of the vaccine.

A look at the 2 meningococcal B vaccines

Two meningococcal B vaccines are now licensed for use in the United States. MenB-FHbp (Trumenba, Pfizer) was licensed in October 2014 as a 3-dose series given at 0, 2, and 6 months.2 MenB-4C (Bexsero, Novartis/GSK) was licensed in January 2015 and requires 2 doses at 0 and ≥1 month.3 Both vaccines induce a level of antibody production that is considered immunogenic in a high proportion of those vaccinated, but the level of immunity wanes after 6 to 24 months. The clinical significance of this drop in immunity is unknown and cannot be tested currently because of the rarity of the disease. Unfortunately, the rate of asymptomatic carriage of meningococcal B does not appear to be affected by vaccination.1

Both vaccines produce local and systemic reactions at rates higher than other recommended vaccines for this age group: pain at the injection site (83%-85%), headache (33%-35%), myalgia (30%-48%), fatigue (35%-40%), induration (28%), nausea (18%), chills (15%), and arthralgia (13%).2,3 There is some theoretical concern about the potential for autoimmune disease from the use of meningococcal B vaccines that will be studied as the vaccines are used more widely.1 In addition, the CDC estimates that serious anaphylactic reactions can occur after administration of any vaccine, estimated at about one per every million doses.1

Meningococcal serotype B bacteria consist of different strains. The 2 approved vaccines cover today’s most frequently found strains in the United States, but it’s uncertain if this will hold true in the future.

USPSTF: Screen obese/overweight adults for type 2 diabetes

The United States Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recently updated its recommendation for screening for type 2 diabetes in adults. USPSTF recommends screening adults, ages 40 to 70 years, who are obese or overweight and referring those who have abnormal blood glucose to intensive behavioral counseling to promote a healthful diet and physical activity.

The Task Force gave this recommendation a grade of B, meaning that it is likely to result in a moderate level of benefit from a reduction in progression to diabetes. The Task Force also emphasized that lifestyle modifications have a greater risk-reducing effect than metformin and other medications.

The recommendation rationale points out that screening might also benefit those at high risk of diabetes based on family history or race/ethnicity and does not apply to those with signs and symptoms of diabetes; testing in this latter group is considered diagnostic testing, not screening.

Screening can be done by measuring glycated hemoglobin A1c or fasting glucose or with a glucose tolerance test. The recommendation includes tables that list the cutoffs for abnormal glucose levels for impaired fasting glucose, impaired glucose tolerance, and increased average glucose level. Obesity is defined as a body mass index ≥30 kg/m2 and overweight as >25 kg/m2.

This new recommendation expands the list of those at risk and those who should be screened compared to the previous recommendation, but the Task Force found no evidence to support universal screening in adults as advocated by other organizations.

Source: USPSTF. Final recommendation statement. Abnormal blood glucose and type 2 diabetes mellitus: screening. Available at: http://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/RecommendationStatementFinal/screening-for-abnormal-blood-glucose-and-type-2-diabetes. Accessed November 13, 2015.

Recommendation considerations that came into play

A number of factors affected ACIP’s recommendation decision: the low incidence of the meningococcal B disease; the large number-needed-to-vaccinate to prevent a case and a death; uncertainties regarding the duration of protection; cost, lack of effect on carriage rates, and limited safety data with the potential for serious reactions to exceed the number of cases prevented; and the severity of the disease and the concern it elicits.

ACIP has multiple options when considering a vaccine: recommend it routinely for everyone or everyone in a defined group (A recommendation), recommend for individual decision making (B recommendation), recommend against use, and make no recommendation at all. Given that 2 meningococcal B vaccines are licensed in the United States and can be used by those who want them—and the Committee’s opinion that these vaccines should not (at this time) be included in the schedule of routinely-recommended vaccines—ACIP chose to make a B recommendation on their use (TABLE 2).1 Vaccines recommended by ACIP (both A and B recommendations) are mandated in the Affordable Care Act to be provided by commercial health insurance at no out-of-pocket expense to the patient.

A word about high-risk populations

At its February 2015 meeting, ACIP voted to recommend meningococcal B vaccine for use in high-risk populations and during outbreaks (TABLE 3).4 This recommendation—plus the most recent B recommendation for general use—comprise the totality of current recommendations for the prevention of meningococcal B disease in the United States.

1. MacNeil J. Considerations for the use of serogroup B meningococcal (MenB) vaccines in adolescents. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 24, 2015; Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2015-06/mening-03-macneil.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

2. Trumenba [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Pfizer); 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM421139.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

3. Bexsero [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics Inc; 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM431447.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

4. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

1. MacNeil J. Considerations for the use of serogroup B meningococcal (MenB) vaccines in adolescents. Presented at: Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices; June 24, 2015; Atlanta, GA. Available at: http://www.cdc.gov/vaccines/acip/meetings/downloads/slides-2015-06/mening-03-macneil.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

2. Trumenba [package insert]. Philadelphia, PA: Wyeth Pharmaceuticals Inc. (Pfizer); 2014. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM421139.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

3. Bexsero [package insert]. Cambridge, MA: Novartis Vaccines and Diagnostics Inc; 2015. Available at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/BiologicsBloodVaccines/Vaccines/ApprovedProducts/UCM431447.pdf. Accessed October 14, 2015.

4. Folaranmi T, Rubin L, Martin SW, et al. Use of serogroup B meningococcal vaccines in persons aged ≥10 years at increased risk for serogroup B meningococcal disease: recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, 2015. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2015;64:608-612.

Being honest about diagnostic uncertainty

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Like everyone else’s grandmother, mine gave me all kinds of advice while I was growing up. Some tips I still remember.

One came when I was home for Thanksgiving during my first year of medical school. She was frustrated over her recent visit to an internist. He kept ordering more tests but wouldn’t answer questions about what might be causing her symptoms.

She told me that, if I didn’t know what was going on, to just say so. As a patient, she felt that an honest answer was better than silence.

Today, as a doctor, I agree with her. So, while I may still be doing tests to crack the case, I have no problem, when asked what I think is going on, with saying “I don’t know.”

This approach isn’t perfect for everyone. Some docs (and patients) may see it as a sign of incompetence or weakness, thinking that admitting fallibility is a breach of the relationship or that with some tests the doctor becomes omniscient. Of course, that’s far from the truth.

In my experience, patients prefer the honesty of my saying “I don’t know.” I’m not saying I’ll never know, I’m just saying that, at present, I’m still looking for the answer.

Nobody likes being in the dark about their health, but at the same time they don’t want to feel their doctor is keeping a secret from them. By making it clear that I’m not, I’m hoping to keep a strong therapeutic relationship. I promise them that when I know, they’ll know, and that I’m honest when stumped. If I need to refer elsewhere for an answer, I have no problem doing that. Medicine, and neurology in particular, is a complex field. If every diagnosis were a slam-dunk, we wouldn’t need specialists and subspecialists (and even subsubspecialists).

Most people know and understand that, recognize the inherent uncertainty of this job, and know that I don’t know. I promise them that “I don’t know” doesn’t mean I’m done looking, it just means I’m going to keep trying. That’s the best anyone can do. Right, Granny?

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Cardiovascular Disease: From Milestones to Innovations

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Introduction: The transition from milestones to innovations

Maan a. Fares, MD

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: History and current indications

Ahmad Zeeshan, MD; E. Murat Tuzcu, MD; Amar Krishnaswamy, MD; Samir Kapadia, MD; and Stephanie Mick, MD

Evolving strategies to prevent stroke and thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation

Ayman Hussein, MD; Walid Saliba, MD; and Oussama Wazni, MD

Stroke management and the impact of mobile stroke treatment units

Peter A. Rasmussen, MD

Biomarkers: Their potential in the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure

Barbara Heil, MD, and W.H. Wilson Tang, MD

Clinical challenges in diagnosing and managing adult hypertension

Joel Handler, MD

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Introduction: The transition from milestones to innovations

Maan a. Fares, MD

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: History and current indications

Ahmad Zeeshan, MD; E. Murat Tuzcu, MD; Amar Krishnaswamy, MD; Samir Kapadia, MD; and Stephanie Mick, MD

Evolving strategies to prevent stroke and thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation

Ayman Hussein, MD; Walid Saliba, MD; and Oussama Wazni, MD

Stroke management and the impact of mobile stroke treatment units

Peter A. Rasmussen, MD

Biomarkers: Their potential in the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure

Barbara Heil, MD, and W.H. Wilson Tang, MD

Clinical challenges in diagnosing and managing adult hypertension

Joel Handler, MD

Supplement Editor:

Maan A. Fares, MD

Contents

Introduction: The transition from milestones to innovations

Maan a. Fares, MD

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: History and current indications

Ahmad Zeeshan, MD; E. Murat Tuzcu, MD; Amar Krishnaswamy, MD; Samir Kapadia, MD; and Stephanie Mick, MD

Evolving strategies to prevent stroke and thromboembolism in nonvalvular atrial fibrillation

Ayman Hussein, MD; Walid Saliba, MD; and Oussama Wazni, MD

Stroke management and the impact of mobile stroke treatment units

Peter A. Rasmussen, MD

Biomarkers: Their potential in the diagnosis and treatment of heart failure

Barbara Heil, MD, and W.H. Wilson Tang, MD

Clinical challenges in diagnosing and managing adult hypertension

Joel Handler, MD

Introduction: The transition from milestones to innovations

Physicians who were educated and began practicing in the 20th century have witnessed some of the most significant innovations and discoveries in the history of healthcare. While major surgical and therapeutic milestones defined the previous century, our current century is defined by the high-speed pace of technological innovations that affect the practice of medicine. For example, the proliferation of hand-held communication devices now provides immediate access to a wealth of healthcare information. Ultimately, recollecting information will be less necessary and far less valuable than understanding the concepts behind it. The challenge for providers is to recognize how to incorporate these innovations into the traditional model of treating diseases with the goal of improving outcomes and containing costs.

With that objective in mind, the articles in this Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement on cardiovascular disease aim to not only review traditional treatment models for cardiovascular disease but, more importantly, to address the broad implications of new innovations on day-to-day clinical practice.

Stephanie Mick, MD, and colleagues look at how the emergence of new devices and technologies has dramatically improved the treatment of severe aortic valve stenosis and expanded the patient population eligible for aortic valve replacement. The authors review the expanded array of surgical approaches to transcatheter aortic valve replacement and the development of new devices in light of their impact on reducing the risks and improving the outcomes associated with this therapy.

Oussama Wazni, MD, and colleagues present evidence underlying the evolving strategies to prevent serious complications of stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Newer anticoagulants are changing the strategic picture. The article includes discussion of the safety and efficacy of the available anticoagulants, as well as nonpharmacologic approaches, and considers how the new data and medications affect traditional treatment models. The authors integrate the data into an evidence-based appraisal of how to best use these innovations to reduce stroke risk in this patient population.

Acute strokes have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality worldwide. Findings that stress the importance of reducing the “time to treatment”—the shorter the time, the better the outcomes—have pushed treatment approaches to center stage. A key factor is the time it takes for patients to arrive in the emergency department. One way to reduce this time is to take the treatment to the patient. Peter A. Rasmussen, MD, looks at how innovations in scanning technologies and wireless data transmissions have led to the development of spe- cially equipped mobile stroke units that can accurately differentiate the types of stroke and enable practitioners to more quickly begin appropriate thromboembolic therapy and reduce the time to therapy.

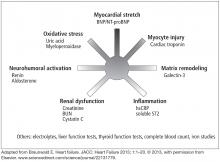

Barbara Heil, MD, and W. H. Wilson Tang, MD, review the use of cardiac biomarkers to diagnose and treat heart failure. Studies have shown the efficacy of using biomarkers to identify high-risk patients, but various factors limit their diagnostic accuracy and clinical adaptability. The authors summarize the data and explain how to incorporate biomarkers into clinical practice.

Hypertension control remains an elusive goal for practitioners. Joel Handler, MD, reviews how new evidence and innovations are revising the diagnostic guidelines and the recommended treatment strategies. He discusses innovations associated with out-of-office monitoring and new data from clinical trials that are changing the clinical practice model. He also addresses the controversy regarding systolic blood pressure goals in elderly patients and how these data have affected evidence-based guidelines.

We hope you find this supplement both informative and thought-provoking.

Physicians who were educated and began practicing in the 20th century have witnessed some of the most significant innovations and discoveries in the history of healthcare. While major surgical and therapeutic milestones defined the previous century, our current century is defined by the high-speed pace of technological innovations that affect the practice of medicine. For example, the proliferation of hand-held communication devices now provides immediate access to a wealth of healthcare information. Ultimately, recollecting information will be less necessary and far less valuable than understanding the concepts behind it. The challenge for providers is to recognize how to incorporate these innovations into the traditional model of treating diseases with the goal of improving outcomes and containing costs.

With that objective in mind, the articles in this Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement on cardiovascular disease aim to not only review traditional treatment models for cardiovascular disease but, more importantly, to address the broad implications of new innovations on day-to-day clinical practice.

Stephanie Mick, MD, and colleagues look at how the emergence of new devices and technologies has dramatically improved the treatment of severe aortic valve stenosis and expanded the patient population eligible for aortic valve replacement. The authors review the expanded array of surgical approaches to transcatheter aortic valve replacement and the development of new devices in light of their impact on reducing the risks and improving the outcomes associated with this therapy.

Oussama Wazni, MD, and colleagues present evidence underlying the evolving strategies to prevent serious complications of stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Newer anticoagulants are changing the strategic picture. The article includes discussion of the safety and efficacy of the available anticoagulants, as well as nonpharmacologic approaches, and considers how the new data and medications affect traditional treatment models. The authors integrate the data into an evidence-based appraisal of how to best use these innovations to reduce stroke risk in this patient population.

Acute strokes have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality worldwide. Findings that stress the importance of reducing the “time to treatment”—the shorter the time, the better the outcomes—have pushed treatment approaches to center stage. A key factor is the time it takes for patients to arrive in the emergency department. One way to reduce this time is to take the treatment to the patient. Peter A. Rasmussen, MD, looks at how innovations in scanning technologies and wireless data transmissions have led to the development of spe- cially equipped mobile stroke units that can accurately differentiate the types of stroke and enable practitioners to more quickly begin appropriate thromboembolic therapy and reduce the time to therapy.

Barbara Heil, MD, and W. H. Wilson Tang, MD, review the use of cardiac biomarkers to diagnose and treat heart failure. Studies have shown the efficacy of using biomarkers to identify high-risk patients, but various factors limit their diagnostic accuracy and clinical adaptability. The authors summarize the data and explain how to incorporate biomarkers into clinical practice.

Hypertension control remains an elusive goal for practitioners. Joel Handler, MD, reviews how new evidence and innovations are revising the diagnostic guidelines and the recommended treatment strategies. He discusses innovations associated with out-of-office monitoring and new data from clinical trials that are changing the clinical practice model. He also addresses the controversy regarding systolic blood pressure goals in elderly patients and how these data have affected evidence-based guidelines.

We hope you find this supplement both informative and thought-provoking.

Physicians who were educated and began practicing in the 20th century have witnessed some of the most significant innovations and discoveries in the history of healthcare. While major surgical and therapeutic milestones defined the previous century, our current century is defined by the high-speed pace of technological innovations that affect the practice of medicine. For example, the proliferation of hand-held communication devices now provides immediate access to a wealth of healthcare information. Ultimately, recollecting information will be less necessary and far less valuable than understanding the concepts behind it. The challenge for providers is to recognize how to incorporate these innovations into the traditional model of treating diseases with the goal of improving outcomes and containing costs.

With that objective in mind, the articles in this Cleveland Clinic Journal of Medicine supplement on cardiovascular disease aim to not only review traditional treatment models for cardiovascular disease but, more importantly, to address the broad implications of new innovations on day-to-day clinical practice.

Stephanie Mick, MD, and colleagues look at how the emergence of new devices and technologies has dramatically improved the treatment of severe aortic valve stenosis and expanded the patient population eligible for aortic valve replacement. The authors review the expanded array of surgical approaches to transcatheter aortic valve replacement and the development of new devices in light of their impact on reducing the risks and improving the outcomes associated with this therapy.

Oussama Wazni, MD, and colleagues present evidence underlying the evolving strategies to prevent serious complications of stroke and thromboembolism in patients with atrial fibrillation. Newer anticoagulants are changing the strategic picture. The article includes discussion of the safety and efficacy of the available anticoagulants, as well as nonpharmacologic approaches, and considers how the new data and medications affect traditional treatment models. The authors integrate the data into an evidence-based appraisal of how to best use these innovations to reduce stroke risk in this patient population.

Acute strokes have a significant impact on morbidity and mortality worldwide. Findings that stress the importance of reducing the “time to treatment”—the shorter the time, the better the outcomes—have pushed treatment approaches to center stage. A key factor is the time it takes for patients to arrive in the emergency department. One way to reduce this time is to take the treatment to the patient. Peter A. Rasmussen, MD, looks at how innovations in scanning technologies and wireless data transmissions have led to the development of spe- cially equipped mobile stroke units that can accurately differentiate the types of stroke and enable practitioners to more quickly begin appropriate thromboembolic therapy and reduce the time to therapy.

Barbara Heil, MD, and W. H. Wilson Tang, MD, review the use of cardiac biomarkers to diagnose and treat heart failure. Studies have shown the efficacy of using biomarkers to identify high-risk patients, but various factors limit their diagnostic accuracy and clinical adaptability. The authors summarize the data and explain how to incorporate biomarkers into clinical practice.

Hypertension control remains an elusive goal for practitioners. Joel Handler, MD, reviews how new evidence and innovations are revising the diagnostic guidelines and the recommended treatment strategies. He discusses innovations associated with out-of-office monitoring and new data from clinical trials that are changing the clinical practice model. He also addresses the controversy regarding systolic blood pressure goals in elderly patients and how these data have affected evidence-based guidelines.

We hope you find this supplement both informative and thought-provoking.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: History and current indications

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has established itself as an effective way of treating high-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. With new generations of existing valves and newer alternative devices, the procedure promises to become increasingly safer. The field is evolving rapidly and it will be important for interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons alike to stay abreast of developments. This article reviews the history of this promising procedure and examines its use in current practice.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In 1980, Danish researcher H. R. Anderson reported developing and testing a balloon-expandable valve in animals.1 The technology was eventually acquired and further developed by Edwards Life Sciences (Irvine, California).

Alain Cribier started early work in humans in 2002 in France.2 He used a transfemoral arterial access to approach the aortic valve transseptally, but this procedure was associated with high rates of mortality and stroke.3 At the same time, in the United States, animal studies were being carried out by Lars G. Svensson, Todd Dewey, and Michael Mack to develop a transapical method of implantation,4,5 while John Webb and colleagues were also developing a transapical aortic valve implantation technique,6,7 and later went on to develop a retrograde transfemoral technique. This latter technique became feasible once Edwards developed a catheter that could be flexed to get around the aortic arch and across the aortic valve.

As the Edwards balloon-expandable valve (Sapien) was being developed, a nitinol-based self-expandable valve system was introduced by Medtronic: the CoreValve. Following feasibility studies,5,8 the safety and efficacy of these valves were established thorough the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial and the US Core Valve Pivotal Trial. These valves are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients for whom conventional surgery would pose an extreme or high risk.9–11

CLINICAL TRIALS OF TAVR

The two landmark prospective randomized trials of TAVR were the PARTNER trial and CoreValve Pivotal Trial.

The PARTNER trial consisted of two parts: PARTNER A, which compared the Sapien balloon-expandable transcatheter valve with surgical aortic valve replacement in patients at high surgical risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons [STS] score > 10%), and PARTNER B, which compared TAVR with medical therapy in patients who could not undergo surgery (combined risk of serious morbidity or death of 50% or more, and two surgeons agreeing that the patient was inoperable).

Similarly, the CoreValve Pivotal Trial compared the self-expandable transcatheter valve with conventional medical and surgical treatment.

TAVR is comparable to surgery in outcomes, with caveats

In the PARTNER A trial, mortality rates were similar between patients who underwent Sapien TAVR and those who underwent surgical valve replacement at 30 days (3.4% and 6.5%, P = .07), 1 year (24.2% and 26.8%), and 2 years (33.9% and 35.0%). The patients in this group were randomized to either Sapien TAVR or surgery (Table 1).10,12

The combined rate of stroke and transient ischemic attack was higher in the patients assigned to TAVR at 30 days (5.5% with TAVR vs 2.4% with surgery, P = .04) and at 1 year (8.3% with TAVR vs 4.3% with surgery, P = .04). The difference was of small significance at 2 years (11.2% vs 6.5%, P = .05). At 30 days, the rate of major vascular complications was higher with TAVR (11.0% vs 3.2%), while surgery was associated with more frequent major bleeding episodes (19.5% vs 9.3%) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (16.0% vs 8.6%). The rate of new pacemaker requirement at 30 days was similar between the TAVR and surgical groups (3.8% vs 3.6%). Moderate or severe paravalvular aortic regurgitation was more common after TAVR at 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years. This aortic insufficiency was associated with increased late mortality.10,12

In the US CoreValve High Risk Study, no difference was found in the 30-day mortality rate in patients at high surgical risk randomized to CoreValve TAVR or surgery (3.3% and 4.5%) (Table 1). Surprisingly, the 1-year mortality rate was lower in the TAVR group than in the surgical group (14.1% vs 18.9%, respectively), a finding sustained at 2 years in data presented at the American College of Cardiology conference in March 2015.13–16

TAVR is superior to medical management, but the risk of stroke is higher

In the PARTNER B trial, inoperable patients were randomly assigned to undergo TAVR with a Sapien valve or medical management. TAVR resulted in lower mortality rates at 1 year (30.7% vs 50.7%) and 2 years (43.4% vs 68.0%) compared with medical management (Table 1).17 Of note, medical management included balloon valvuloplasty. The rate of the composite end point of death or repeat hospitalization was also lower with TAVR compared with medical therapy (44.1% vs 71.6%, respectively, at 1 year and 56.7% and 87.9%, respectively, at 2 years).17 The TAVR group had a higher stroke rate than the medical therapy group at 30 days (11.2% vs 5.5%, respectively) and at 2 years (13.8% vs 5.5%).17 Survival improved with TAVR in patients with an STS score of less than 15% but not in those with an STS score of 15% or higher.9

The very favorable results from the PARTNER trial rendered a randomized trial comparing self-expanding (CoreValve) TAVR and medical therapy unethical. Instead, a prospective single-arm study, the CoreValve Extreme Risk US Pivotal Trial, was used to compare the 12-month rate of death or major stroke with CoreValve TAVR vs a prespecified estimate of this rate with medical therapy.14 In about 500 patients who had a CoreValve attempt, the rate of all-cause mortality or major stroke at 1 year was significantly lower than the prespecified expected rate (26% vs 43%), reinforcing the results from the PARTNER Trial.14

Five-year outcomes

The 5-year PARTNER clinical and valve performance outcomes were published recently18 and continued to demonstrate equivalent outcomes for high-risk patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement or TAVR; there were no significant differences in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, stroke, or need for readmission to the hospital. The functional outcomes were similar as well, and no differences were demonstrated between surgical and TAVR valve performance.

Of note, moderate or severe aortic regurgitation occurred in 14% of patients in the TAVR group compared with 1% in the surgical aortic valve replacement group (P < .0001). This was associated with increased 5-year risk of death in the TAVR group (72.4% in those with moderate or severe aortic regurgitation vs 56.6% in those with mild aortic regurgitation or less; P = .003).

If the available randomized data are combined with observational reports, overall mortality and stroke rates are comparable between surgical aortic valve replacement and balloon-expandable or self-expandable TAVR in high-risk surgical candidates. Vascular complications, aortic regurgitation and permanent pacemaker insertion occur more frequently after TAVR, while major bleeding is more likely to occur after surgery.19 As newer generations of valves are developed, it is expected that aortic regurgitation and pacemaker rates will decrease over time. Indeed, trial data presented at the American College of Cardiology meeting in March 2015 for the third-generation Sapien valve (Sapien S3) showed only a 3.0% to 4.2% rate of significant paravalvular leak.

Contemporary valve comparison data

The valve used in the original PARTNER data was the first-generation Sapien valve. Since then, the second generation of this valve, the Sapien XT, has been introduced and is the model currently used in the United States (with the third-generation valve mentioned above, the Sapien S3, still available only through clinical trials). Thus, the two contemporary valves available for commercial use in the United States are the Edwards Sapien XT and Medtronic CoreValve. There are limited data comparing these valves head-to-head, but one recent trial attempted to do just that.

The Comparison of Transcatheter Heart Valves in High Risk Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis: Medtronic CoreValve vs Edwards Sapien XT (CHOICE) trial compared the Edwards Sapien XT and CoreValve devices. Two hundred and forty-one patients were randomized. The primary end point of this trial was “device success” (a composite end point of four components: successful vascular access and deployment of the device with retrieval of the delivery system, correct position of the device, intended performance of the valve without moderate or severe insufficiency, and only one valve implanted in the correct anatomical location).

In this trial, the balloon-expandable Sapien XT valve showed a significantly higher device success rate than the self-expanding CoreValve, due to a significantly lower rate of aortic regurgitation (4.1% vs 18.3%, P < .001) and the less frequent need for implantation of more than one valve (0.8% vs 5.8%, P = .03). Placement of a permanent pacemaker was considerably less frequent in the balloon-expandable valve group (17.3% vs 37.6%, P = .001).20

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS AND EVALUATION CRITERIA

Currently, TAVR is indicated for patients with symptomatic severe native aortic valve stenosis who are deemed at high risk or inoperable by a heart team including interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. The CoreValve was also recently approved for valve-in-valve insertion in high-risk or inoperable patients with a prosthetic aortic valve in place.

The STS risk score is a reasonable preliminary risk assessment tool and is applicable to most patients being evaluated for aortic valve replacement. The STS risk score represents the percentage risk of unfavorable outcomes based on certain clinical variables. A calculator is available at riskcalc.sts.org. Patients considered at high risk are those with an STS operative risk score of 8% or higher or a postoperative 30-day risk of death of 15% or higher.

It is important to remember, though, that the STS score does not account for certain severe surgical risk factors. These include the presence of a "porcelain aorta" (heavy circumferential calcification of the ascending aorta precluding cross-clamping), history of mediastinal radiation, “hostile chest” (kyphoscoliosis, other deformities, previous coronary artery bypass grafting with adhesion of internal mammary artery to the back of sternum), severely compromised respiratory function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second < 1 L or < 40% predicted, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide < 30%), severe pulmonary hypertension, severe liver disease (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 8–20), severe dementia, severe cerebrovascular disease, and frailty.

With regard to this last risk factor, frailty is not simply old age but rather a measurable characteristic akin to weakness or disability. Several tests exist to measure frailty, including the “eyeball test” (the physician’s subjective assessment), Mini-Mental State Examination, gait speed/15-foot walk test, hand grip strength, serum albumin, and assessment of activities of daily living. Formal frailty testing is recommended during the course of a TAVR workup.

Risk assessment and patient suitability for TAVR is ultimately determined by the combined judgment of the heart valve team using both the STS score and consideration of these other factors.

Implantation approaches

Today, TAVR could be performed by several approaches: transfemoral arterial, transapical, transaortic via partial sternotomy or right anterior thoracotomy,21,22 transcarotid,23–25 and transaxillary or subclavian.26,27 Less commonly, transfemoral-venous routes have been performed utilizing either transseptal28 or caval-aortic puncture.29

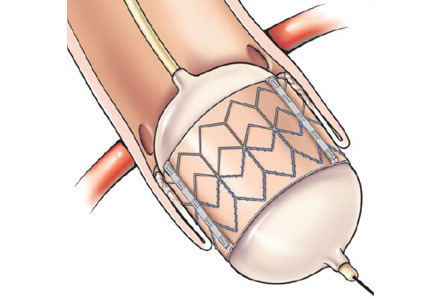

The transfemoral approach is used most commonly by most institutions, including Cleveland Clinic. It allows for a completely percutaneous insertion and, in select cases, without endotracheal intubation and general anesthesia (Figure 1).

In patients with difficult femoral access due to severe calcification, extreme tortuosity, or small diameter, alternative access routes become a consideration. In this situation, at our institution, we favor the transaortic approach in patients who have not undergone cardiac surgery in the past, while the transapical approach is used in patients who had previous cardiac surgery. With the transapical approach, we have found the outcomes similar to those of transfemoral TAVR after propensity matching.30,31 Although there is a learning curve,32 transapical TAVR can be performed with very limited mortality and morbidity. In a recent series at Cleveland Clinic, the mortality rate with the transapical approach was 1.2%, renal failure occurred in 4.7%, and a pacemaker was placed in 5.9% of patients; there were no strokes.33 This approach can be utilized for simultaneous additional procedures like transcatheter mitral valve reimplantation and percutaneous coronary interventions.34–36

- Andersen HR, Knudsen LL, Hasenkam JM. Transluminal implantation of artificial heart valves. Description of a new expandable aortic valve and initial results with implantation by catheter technique in closed chest pigs. Eur Heart J 1992; 13:704– 708.

- Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Bash A, et al. Percutaneous transcatheter implantation of an aortic valve prosthesis for calcific aortic stenosis: first human case descrip- tion. Circulation 2002; 106:3006–3008.

- Cribier A, Eltchaninoff H, Tron C, et al. Early experience with percutaneous transcatheter implantation of heart valve prosthesis for the treatment of end-stage inoperable patients with calcific aortic stenosis. J Am Coll Cardiol 2004; 43:698– 703.

- Dewey TM, Walther T, Doss M, et al. Transapical aortic valve implantation: an animal feasibility study. Ann Thorac Surg 2006; 82:110–116.

- Svensson LG, Dewey T, Kapadia S, et al. United States feasibility study of trans- catheter insertion of a stented aortic valve by the left ventricular apex. Ann Thorac Surg 2008; 86:46–54.

- Lichtenstein SV, Cheung A, Ye J, et al. Transapical transcatheter aortic valve im- plantation in humans: initial clinical experience. Circulation 2006; 114:591–596.

- Webb JG, Pasupati S, Hyumphries K, et al. Percutaneous transarterial aortic valve replacement in selected high-risk patients with aortic stenosis. Circulation 2007; 116:755–763.

- Leon MB, Kodali S, Williams M, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with critical aortic stenosis: rationale, device descriptions, early clinical experiences, and perspectives. Semin Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2006; 18:165–174.

- Leon MB, Smith CR, Mack M, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve implantation for aortic stenosis in patients who cannot undergo sur- gery. N Engl J Med 2010; 363:1597–1607.

- Smith CR, Leon MB, Mack MJ, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Transcatheter versus surgical aortic-valve replacement in high-risk patients. N Engl J Med 2011; 364:2187–2198.

- Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ, et al; U.S. CoreValve Clinical Investigators. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis. N Engl J Med 2014; 370:1790–1798.

- Kodali SK, Williams MR, Smith CR, et al; PARTNER Trial Investigators. Two- year outcomes after transcatheter or surgical aortic-valve replacement. N Engl J Med 2012; 366:1686–1695.

- Reardon M, et al. A randomized comparison of self-expanding

- Popma JJ, Adams DH, Reardon MJ, et al; CoreValve United States Clinical In- vestigators. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement using a self-expanding biopros- thesis in patients with severe aortic stenosis at extreme risk for surgery. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:1972–1981.

- Adams DH, Popma JJ, Reardon MJ. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis (letter). N Engl J Med 2014; 371:967–968.

- Kaul S. Transcatheter aortic-valve replacement with a self-expanding prosthesis (letter). N Engl J Med 2014; 371:967.

- Makkar RR, Fontana GP, Jilaihawi H, et al. Transcathether aortic-valve re- placement for inoperable severe aortic stenosis. N Engl J Med 2012; 366: 1696–704.

- Mack MJ, Leon MB, Smith CR, et al; PARTNER 1 trial investigators. 5-year outcomes of transcatheter aortic valve replacement or surgical aortic valve re- placement for high surgical risk patients with aortic stenosis (PARTNER 1): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2015; 385:2477–2484.

- Cao C, Ang SC, Indraratna P, et al. Systematic review and meta-analysis of trans- catheter aortic valve implantation versus surgical aortic valve replacement for severe aortic stenosis. Ann Cardiothorac Surg 2013; 2:10–23.

- Abdel-Wahab M, Mehilli J, Frerker C, et al; CHOICE investigators. Comparison of balloon-expandable vs self-expandable valves in patients undergoing transcath- eter aortic valve replacement: the CHOICE randomized clinical trial. JAMA 2014; 311:1503–1514.

- Okuyama K, Jilaihawi H, Mirocha J, et al. Alternative access for balloon-ex- pandable transcatheter aortic valve replacement: comparison of the transaortic approach using right anterior thoracotomy to partial J-sternotomy. J Thorac Car- diovasc Surg 2014; 149:789–797.

- Lardizabal JA, O’Neill BP, Desai HV, et al. The transaortic approach for transcath- eter aortic valve replacement: initial clinical experience in the United States. J Am Coll Cardiol 2013; 61:2341–2345.

- Thourani VH, Gunter RL, Neravetla S, et al. Use of transaortic, transapical, and transcarotid transcatheter aortic valve replacement in inoperable patients. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96:1349–1357.

- Azmoun A, Amabile N, Ramadan R, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation through carotid artery access under local anaesthesia. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg 2014; 46: 693–698.

- Rajagopal R, More RS, Roberts DH. Transcatheter aortic valve implantation through a transcarotid approach under local anesthesia. Catheter Cardiovasc In- terv 2014; 84:903–907.

- Fraccaro C, Napodano M, Tarantini G, et al. Expanding the eligibility for trans- catheter aortic valve implantation the trans-subclavian retrograde approach using: the III generation CoreValve revalving system. JACC Cardiovasc Interv 2009; 2:828–333.

- Petronio AS, De Carlo M, Bedogni F, et al. Safety and efficacy of the subclavian approach for transcatheter aortic valve implantation with the CoreValve revalving system. Circ Cardiovasc Interv 2010; 3:359–366.

- Cohen MG, Singh V, Martinez CA, et al. Transseptal antegrade transcatheter aor- tic valve replacement for patients with no other access approach—a contemporary experience. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv 2013; 82:987–993.

- Greenbaum AB, O’Neill WW, Paone G, et al. Caval-aortic access to allow trans- catheter aortic valve replacement in otherwise ineligible patients: initial human experience. J Am Coll Cardiol 2014; 63:2795–2804.

- D’Onofrio A, Salizzoni S, Agrifoglio M, et al. Medium term outcomes of trans- apical aortic valve implantation: results from the Italian Registry of Trans-Apical Aortic Valve Implantation. Ann Thorac Surg 2013; 96:830–835.

- Johansson M, Nozohoor S, Kimblad PO, Harnek J, Olivecrona GK, Sjögren J. Transapical versus transfemoral aortic valve implantation: a comparison of survival and safety. Ann Thorac Surg 2011; 91:57–63.

- Kempfert J, Rastan A, Holzhey D, et al. Transapical aortic valve implantation: analysis of risk factors and learning experience in 299 patients. Circulation 2011; 124(suppl):S124–S129.

- Aguirre J, Waskowski R, Poddar K, et al. Transcatheter aortic valve replacement: experience with the transapical approach, alternate access sites, and concomitant cardiac repairs. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 148:1417–1422.

- Al Kindi AH, Salhab KF, Roselli EE, Kapadia S, Tuzcu EM, Svensson LG. Alternative access options for transcatheter aortic valve replacement in patients with no conventional access and chest pathology. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2014; 147:644–651.

- Salhab KF, Al Kindi AH, Lane JH, et al. Concomitant percutaneous coronary intervention and transcatheter aortic valve replacement: safe and feasible replace- ment alternative approaches in high-risk patients with severe aortic stenosis and coronary artery disease. J Card Surg 2013; 28:481–483.

- Al Kindi AH, Salhab KF, Kapadia S, et al. Simultaneous transapical transcatheter aortic and mitral valve replacement in a high-risk patient with a previous mitral bioprosthesis. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg 2012; 144:e90–e91.

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has established itself as an effective way of treating high-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. With new generations of existing valves and newer alternative devices, the procedure promises to become increasingly safer. The field is evolving rapidly and it will be important for interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons alike to stay abreast of developments. This article reviews the history of this promising procedure and examines its use in current practice.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In 1980, Danish researcher H. R. Anderson reported developing and testing a balloon-expandable valve in animals.1 The technology was eventually acquired and further developed by Edwards Life Sciences (Irvine, California).

Alain Cribier started early work in humans in 2002 in France.2 He used a transfemoral arterial access to approach the aortic valve transseptally, but this procedure was associated with high rates of mortality and stroke.3 At the same time, in the United States, animal studies were being carried out by Lars G. Svensson, Todd Dewey, and Michael Mack to develop a transapical method of implantation,4,5 while John Webb and colleagues were also developing a transapical aortic valve implantation technique,6,7 and later went on to develop a retrograde transfemoral technique. This latter technique became feasible once Edwards developed a catheter that could be flexed to get around the aortic arch and across the aortic valve.

As the Edwards balloon-expandable valve (Sapien) was being developed, a nitinol-based self-expandable valve system was introduced by Medtronic: the CoreValve. Following feasibility studies,5,8 the safety and efficacy of these valves were established thorough the Placement of Aortic Transcatheter Valves (PARTNER) trial and the US Core Valve Pivotal Trial. These valves are currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for patients for whom conventional surgery would pose an extreme or high risk.9–11

CLINICAL TRIALS OF TAVR

The two landmark prospective randomized trials of TAVR were the PARTNER trial and CoreValve Pivotal Trial.

The PARTNER trial consisted of two parts: PARTNER A, which compared the Sapien balloon-expandable transcatheter valve with surgical aortic valve replacement in patients at high surgical risk (Society of Thoracic Surgeons [STS] score > 10%), and PARTNER B, which compared TAVR with medical therapy in patients who could not undergo surgery (combined risk of serious morbidity or death of 50% or more, and two surgeons agreeing that the patient was inoperable).

Similarly, the CoreValve Pivotal Trial compared the self-expandable transcatheter valve with conventional medical and surgical treatment.

TAVR is comparable to surgery in outcomes, with caveats

In the PARTNER A trial, mortality rates were similar between patients who underwent Sapien TAVR and those who underwent surgical valve replacement at 30 days (3.4% and 6.5%, P = .07), 1 year (24.2% and 26.8%), and 2 years (33.9% and 35.0%). The patients in this group were randomized to either Sapien TAVR or surgery (Table 1).10,12

The combined rate of stroke and transient ischemic attack was higher in the patients assigned to TAVR at 30 days (5.5% with TAVR vs 2.4% with surgery, P = .04) and at 1 year (8.3% with TAVR vs 4.3% with surgery, P = .04). The difference was of small significance at 2 years (11.2% vs 6.5%, P = .05). At 30 days, the rate of major vascular complications was higher with TAVR (11.0% vs 3.2%), while surgery was associated with more frequent major bleeding episodes (19.5% vs 9.3%) and new-onset atrial fibrillation (16.0% vs 8.6%). The rate of new pacemaker requirement at 30 days was similar between the TAVR and surgical groups (3.8% vs 3.6%). Moderate or severe paravalvular aortic regurgitation was more common after TAVR at 30 days, 1 year, and 2 years. This aortic insufficiency was associated with increased late mortality.10,12

In the US CoreValve High Risk Study, no difference was found in the 30-day mortality rate in patients at high surgical risk randomized to CoreValve TAVR or surgery (3.3% and 4.5%) (Table 1). Surprisingly, the 1-year mortality rate was lower in the TAVR group than in the surgical group (14.1% vs 18.9%, respectively), a finding sustained at 2 years in data presented at the American College of Cardiology conference in March 2015.13–16

TAVR is superior to medical management, but the risk of stroke is higher

In the PARTNER B trial, inoperable patients were randomly assigned to undergo TAVR with a Sapien valve or medical management. TAVR resulted in lower mortality rates at 1 year (30.7% vs 50.7%) and 2 years (43.4% vs 68.0%) compared with medical management (Table 1).17 Of note, medical management included balloon valvuloplasty. The rate of the composite end point of death or repeat hospitalization was also lower with TAVR compared with medical therapy (44.1% vs 71.6%, respectively, at 1 year and 56.7% and 87.9%, respectively, at 2 years).17 The TAVR group had a higher stroke rate than the medical therapy group at 30 days (11.2% vs 5.5%, respectively) and at 2 years (13.8% vs 5.5%).17 Survival improved with TAVR in patients with an STS score of less than 15% but not in those with an STS score of 15% or higher.9

The very favorable results from the PARTNER trial rendered a randomized trial comparing self-expanding (CoreValve) TAVR and medical therapy unethical. Instead, a prospective single-arm study, the CoreValve Extreme Risk US Pivotal Trial, was used to compare the 12-month rate of death or major stroke with CoreValve TAVR vs a prespecified estimate of this rate with medical therapy.14 In about 500 patients who had a CoreValve attempt, the rate of all-cause mortality or major stroke at 1 year was significantly lower than the prespecified expected rate (26% vs 43%), reinforcing the results from the PARTNER Trial.14

Five-year outcomes

The 5-year PARTNER clinical and valve performance outcomes were published recently18 and continued to demonstrate equivalent outcomes for high-risk patients who underwent surgical aortic valve replacement or TAVR; there were no significant differences in all-cause mortality, cardiovascular mortality, stroke, or need for readmission to the hospital. The functional outcomes were similar as well, and no differences were demonstrated between surgical and TAVR valve performance.

Of note, moderate or severe aortic regurgitation occurred in 14% of patients in the TAVR group compared with 1% in the surgical aortic valve replacement group (P < .0001). This was associated with increased 5-year risk of death in the TAVR group (72.4% in those with moderate or severe aortic regurgitation vs 56.6% in those with mild aortic regurgitation or less; P = .003).

If the available randomized data are combined with observational reports, overall mortality and stroke rates are comparable between surgical aortic valve replacement and balloon-expandable or self-expandable TAVR in high-risk surgical candidates. Vascular complications, aortic regurgitation and permanent pacemaker insertion occur more frequently after TAVR, while major bleeding is more likely to occur after surgery.19 As newer generations of valves are developed, it is expected that aortic regurgitation and pacemaker rates will decrease over time. Indeed, trial data presented at the American College of Cardiology meeting in March 2015 for the third-generation Sapien valve (Sapien S3) showed only a 3.0% to 4.2% rate of significant paravalvular leak.

Contemporary valve comparison data

The valve used in the original PARTNER data was the first-generation Sapien valve. Since then, the second generation of this valve, the Sapien XT, has been introduced and is the model currently used in the United States (with the third-generation valve mentioned above, the Sapien S3, still available only through clinical trials). Thus, the two contemporary valves available for commercial use in the United States are the Edwards Sapien XT and Medtronic CoreValve. There are limited data comparing these valves head-to-head, but one recent trial attempted to do just that.

The Comparison of Transcatheter Heart Valves in High Risk Patients with Severe Aortic Stenosis: Medtronic CoreValve vs Edwards Sapien XT (CHOICE) trial compared the Edwards Sapien XT and CoreValve devices. Two hundred and forty-one patients were randomized. The primary end point of this trial was “device success” (a composite end point of four components: successful vascular access and deployment of the device with retrieval of the delivery system, correct position of the device, intended performance of the valve without moderate or severe insufficiency, and only one valve implanted in the correct anatomical location).

In this trial, the balloon-expandable Sapien XT valve showed a significantly higher device success rate than the self-expanding CoreValve, due to a significantly lower rate of aortic regurgitation (4.1% vs 18.3%, P < .001) and the less frequent need for implantation of more than one valve (0.8% vs 5.8%, P = .03). Placement of a permanent pacemaker was considerably less frequent in the balloon-expandable valve group (17.3% vs 37.6%, P = .001).20

PREOPERATIVE CONSIDERATIONS AND EVALUATION CRITERIA

Currently, TAVR is indicated for patients with symptomatic severe native aortic valve stenosis who are deemed at high risk or inoperable by a heart team including interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons. The CoreValve was also recently approved for valve-in-valve insertion in high-risk or inoperable patients with a prosthetic aortic valve in place.

The STS risk score is a reasonable preliminary risk assessment tool and is applicable to most patients being evaluated for aortic valve replacement. The STS risk score represents the percentage risk of unfavorable outcomes based on certain clinical variables. A calculator is available at riskcalc.sts.org. Patients considered at high risk are those with an STS operative risk score of 8% or higher or a postoperative 30-day risk of death of 15% or higher.

It is important to remember, though, that the STS score does not account for certain severe surgical risk factors. These include the presence of a "porcelain aorta" (heavy circumferential calcification of the ascending aorta precluding cross-clamping), history of mediastinal radiation, “hostile chest” (kyphoscoliosis, other deformities, previous coronary artery bypass grafting with adhesion of internal mammary artery to the back of sternum), severely compromised respiratory function (forced expiratory volume in 1 second < 1 L or < 40% predicted, diffusing capacity for carbon monoxide < 30%), severe pulmonary hypertension, severe liver disease (Model for End-stage Liver Disease score 8–20), severe dementia, severe cerebrovascular disease, and frailty.

With regard to this last risk factor, frailty is not simply old age but rather a measurable characteristic akin to weakness or disability. Several tests exist to measure frailty, including the “eyeball test” (the physician’s subjective assessment), Mini-Mental State Examination, gait speed/15-foot walk test, hand grip strength, serum albumin, and assessment of activities of daily living. Formal frailty testing is recommended during the course of a TAVR workup.

Risk assessment and patient suitability for TAVR is ultimately determined by the combined judgment of the heart valve team using both the STS score and consideration of these other factors.

Implantation approaches

Today, TAVR could be performed by several approaches: transfemoral arterial, transapical, transaortic via partial sternotomy or right anterior thoracotomy,21,22 transcarotid,23–25 and transaxillary or subclavian.26,27 Less commonly, transfemoral-venous routes have been performed utilizing either transseptal28 or caval-aortic puncture.29

The transfemoral approach is used most commonly by most institutions, including Cleveland Clinic. It allows for a completely percutaneous insertion and, in select cases, without endotracheal intubation and general anesthesia (Figure 1).

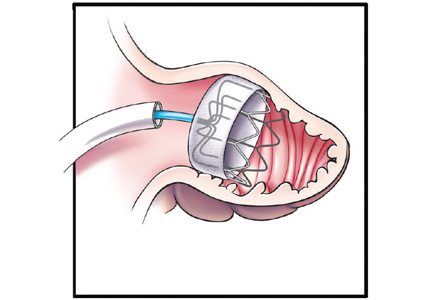

In patients with difficult femoral access due to severe calcification, extreme tortuosity, or small diameter, alternative access routes become a consideration. In this situation, at our institution, we favor the transaortic approach in patients who have not undergone cardiac surgery in the past, while the transapical approach is used in patients who had previous cardiac surgery. With the transapical approach, we have found the outcomes similar to those of transfemoral TAVR after propensity matching.30,31 Although there is a learning curve,32 transapical TAVR can be performed with very limited mortality and morbidity. In a recent series at Cleveland Clinic, the mortality rate with the transapical approach was 1.2%, renal failure occurred in 4.7%, and a pacemaker was placed in 5.9% of patients; there were no strokes.33 This approach can be utilized for simultaneous additional procedures like transcatheter mitral valve reimplantation and percutaneous coronary interventions.34–36

Transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) has established itself as an effective way of treating high-risk patients with severe aortic valve stenosis. With new generations of existing valves and newer alternative devices, the procedure promises to become increasingly safer. The field is evolving rapidly and it will be important for interventional cardiologists and cardiac surgeons alike to stay abreast of developments. This article reviews the history of this promising procedure and examines its use in current practice.

HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE

In 1980, Danish researcher H. R. Anderson reported developing and testing a balloon-expandable valve in animals.1 The technology was eventually acquired and further developed by Edwards Life Sciences (Irvine, California).