User login

Patient with intractable nausea and vomiting

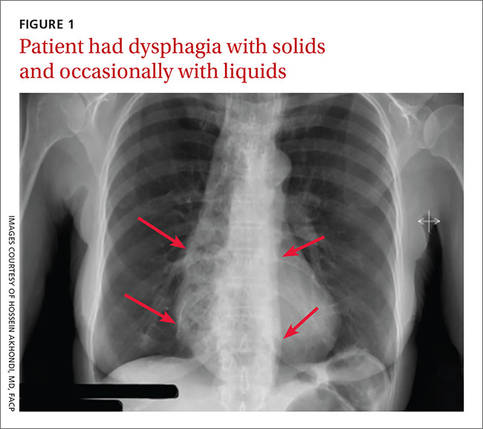

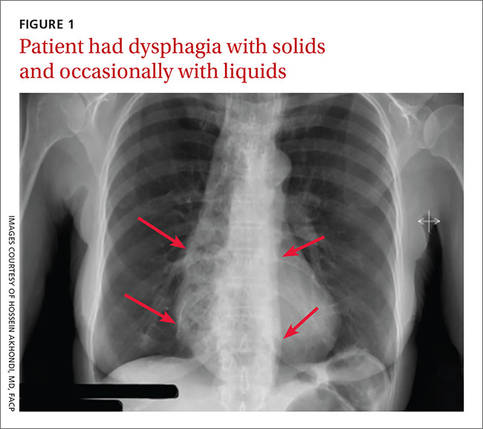

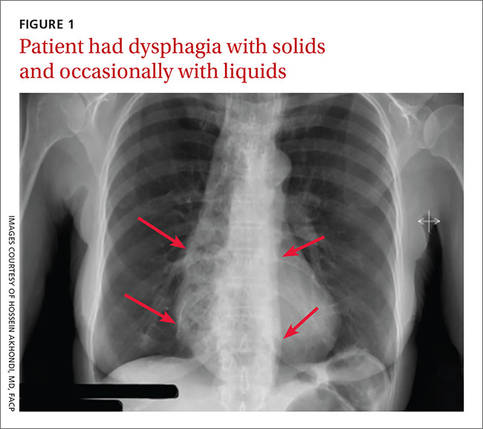

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Achalasia

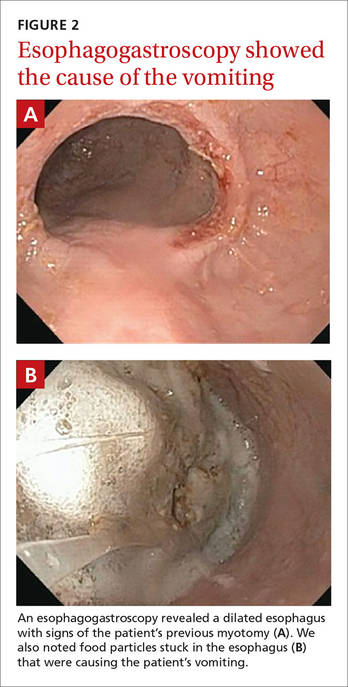

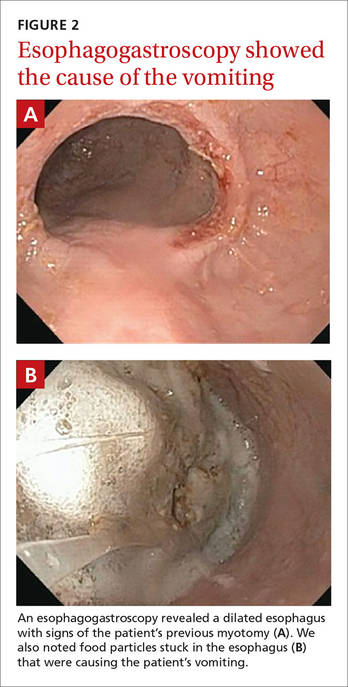

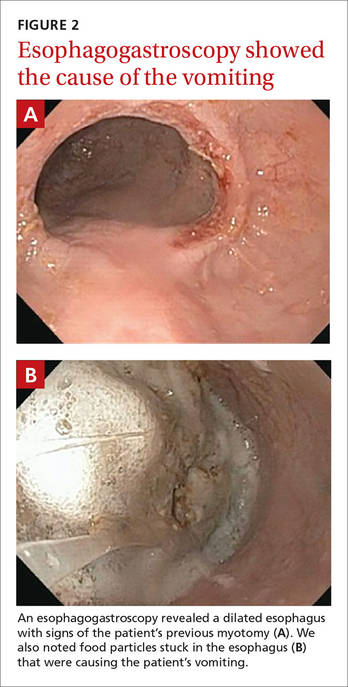

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Achalasia

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

A 53-year-old African American woman was admitted to our hospital for intractable nausea and vomiting that she’d been experiencing for a month. She also reported dysphagia with solids and occasionally with liquids. She had no chest or abdominal pain, and no fever, bleeding, diarrhea, significant weight loss, or significant travel history. The patient was not taking any medication and her physical exam was normal. The patient’s complete blood count and electrolytes were normal. We ordered a chest x-ray (FIGURE 1).

WHAT IS YOUR DIAGNOSIS?

HOW WOULD YOU TREAT THIS PATIENT?

Diagnosis: Achalasia

The radiologist who examined the x-ray noted a dilated esophagus (FIGURE 1, red arrows) with debris behind the heart shadow, which suggested achalasia. Upon further questioning, the patient reported a history of achalasia that had been treated with a myotomy 6 years ago. We performed an esophagogastroscopy, which showed a dilated esophagus with signs of the myotomy (FIGURE 2A), as well as food particles lodged in the esophagus (FIGURE 2B) that were causing the patient’s intractable vomiting.

Achalasia is a motor disorder of the esophagus smooth muscle in which the lower esophageal sphincter does not relax properly with swallowing, and the normal peristalsis of the esophagus body is replaced by abnormal contractions. Primary idiopathic achalasia is the most common form in the United States, but secondary forms caused by gastric carcinoma, lymphoma, or Chagas disease are also seen.1 The prevalence of achalasia is 1.6 per 100,000 in some populations.2 Symptoms can include dysphagia with solids and liquids, chest pain, and regurgitation.

A chest x-ray will show an absence of gastric air, and occasionally, as in this case, a tubular mass (the dilated esophagus) behind the heart and aorta. On fluoroscopy, the lower two-thirds of the esophagus does not have peristalsis and the terminal part has a bird beak appearance. Manometry will show normal or elevated pressure in the lower esophagus. Administration of cholinergic agonists will cause a marked increase in baseline pressure, as well as pain and regurgitation. Endoscopy can exclude secondary causes.

Narrowing the causes of dysphagia

The differential diagnosis is broad because there are 2 types of dysphagia: mechanical and neuromuscular.

Mechanical dysphagia is caused by a food bolus or foreign body, by intrinsic narrowing of the esophagus (from inflammation, esophageal webs, benign and malignant strictures, and tumors) or by extrinsic compression (from bone or thyroid abscesses or vascular tightening).

Neuromuscular dysphagia is either a swallowing reflex problem, a disorder of the pharyngeal and striated esophagus muscles, or an esophageal smooth muscle disorder.3 Close attention to the patient’s history and physical exam is key to zeroing in on the proper diagnosis.

On the other hand, food impaction in the esophagus almost always indicates certain etiologies. Benign esophageal stenosis caused by Schatzki rings (B rings) or by peptic strictures is the most common cause of food impaction, followed by esophageal webs, extrinsic compression, surgical anastomosis, esophagitis (eg, eosinophilic esophagitis), and motor disorders, such as achalasia.

First-line therapy is surgery; pharmacologic Tx is least effective

Treatment should be individualized by age, gender, and patient preference; however, there is no definitive treatment for this condition. First-line therapy includes graded pneumatic dilation or laparoscopic myotomy with a partial fundoplication.4 Botulinum toxin injection in the lower esophageal sphincter is recommended for patients who are not good candidates for surgery or dilation.5

Pharmacologic therapy, the least effective treatment option, is recommended for patients who are unwilling or unable to undergo myotomy and/or dilation and do not respond to botulinum toxin.6,7 Long-acting nitrates such as isosorbide, calcium channel blockers such as nifedipine, and phosphodiesterase-5 (PDE5) inhibitors such as sildenafil reduce lower esophageal sphincter tone and pressure.

Both nifedipine and isosorbide should be taken sublingually before meals (30 minutes and 10 minutes, respectively). The effects of nifedipine and isosorbide, however, are partial, and these agents do not provide complete relief from symptoms.6 PDE5 use has been limited and results are inconclusive.

Our patient. The food particles in the patient’s esophagus were removed during endoscopy, and she stopped vomiting completely. Based on the findings and clinical picture, the patient most likely suffered from mega-esophagus (an end-stage dilated malfunctioning esophagus). Our patient was discharged to follow-up with her gastroenterologist.

Because there is no definitive treatment for achalasia, the patient was counseled about the need for continuous monitoring and dietary precautions, including modification of food texture or change of fluid viscosity. Food may be chopped, minced, or pureed, and fluids may be thickened.

CORRESPONDENCE

Hossein Akhondi, MD, FACP, Georgetown University, 1010 Mass Ave, NW, Unit 904, Washington, DC 20001; [email protected].

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

1. Richter JE. Esophageal motility disorder achalasia. Curr Opin Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2013;21:535-542.

2. O’Neill OM, Johnston BT, Coleman HG. Achalasia: a review of clinical diagnosis, epidemiology, treatment and outcomes. World J Gastroenterol. 2013;19:5806-5812.

3. Ott R, Bajbouj M, Feussner H, et al. [Dysphagia—what is important for primary diagnosis in private practice?]. MMW Fortschr Med. 2014;156:54-57.

4. Yaghoobi M. Treatment of patients with new diagnosis of achalasia: laparoscopic Heller’s myotomy may be more effective than pneumatic dilation. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;80:360.

5. Blatnik JA, Ponsky JL. Advances in the treatment of achalasia. Curr Treat Options Gastroenterol. 2014;12:49-58.

6. Vaezi MF, Pandolfino JE, Vela MF. ACG clinical guideline: diagnosis and management of achalasia. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108:1238-1249.

7. Vaezi MF, Richter JE. Current therapies for achalasia: comparison and efficacy. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1998;27:21-35.

Tips and algorithms to get your patient's BP to goal

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT),1 a study of more than 9000 patients published late last year, was stopped prematurely when it became clear that those receiving intensive treatment (systolic target 120 mm Hg) had significantly lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, cardiovascular death, and other severe heart disease than those getting standard treatment (systolic target 140 mm Hg). Participants had an elevated cardiovascular risk at baseline (age ≥75 years, history of cardiovascular disease [CVD], chronic kidney disease [CKD], or elevated 10-year Framingham CVD risk score ≥15%); those with diabetes, history of stroke, or polycystic kidney disease were excluded.

Although serious adverse events were not significantly different between the intensive and standard treatment groups, syncope, acute renal failure, electrolyte abnormalities, and hyponatremia were all statistically more common in the aggressively treated group. (To learn more, see “Is lower BP worth it in higher-risk patients with diabetes or coronary disease?” Clinical Inquiries, J Fam Pract. 2016;65:129-131.)

Taking an aggressive approach. This trial shined a light on an important topic in medicine—the aggressive treatment of hypertension. And while this article will not discuss the finer points of the SPRINT trial or the limitations of generalizing aggressive treatment to the broad population of patients with hypertension, it will outline important considerations for physicians who wish to aggressively treat hypertension. I offer recommendations based on my 34 years of clinical practice and experience as a co-investigator on a number of hypertension studies to help you better balance each patient’s risks (eg, age, frailty, fall risk) and potential benefits (prevention of stroke, MI, and congestive heart failure).

Taking an aggressive approach, however, starts with ensuring that the diagnosis and treatment are based on accurate measures.

How accurate are your BP readings?

Measuring BP in clinical practice is markedly different from measurements taken in a research setting.2 This can result in large, clinically significant differences in readings and adversely affect treatment decisions.

Quiet time, multiple readings

SPRINT used techniques similar to those followed by other hypertension outcomes studies I’ve been involved in—methods that are rare in medical practice. Each study participant sat quietly in a chair for 5 minutes prior to the first BP reading. In addition, the researchers used an automatic oscillatory BP device (Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, Ill), recording the average of 3 readings.

Practices that compromise accuracy. In clinical practice, BP is rarely measured after the patient has had 5 minutes of rest in a quiet room. Nor are readings done in triplicate. Instead, BP is typically measured while patient and clinician are engaged in conversation, often using a BP cuff that is too small (in my experience, most Americans require a large cuff).

BP is usually taken shortly after the patient has walked, frequently with some difficulty, from the waiting area to the exam room. Often, too, patients are weighed before their BP is measured, a common source of concern that can lead to a short-term rise in pressure. (Conversely, rapid deflation during the auscultatory measurement [>2 mm Hg/sec] can have the opposite effect, resulting in under-reading the true value.)

Compounding matters is the failure to consider the approximately 20% of patients who develop White Coat Syndrome. Such individuals, who typically have elevated office measurements but normal out-of-office readings, may develop further hypotensive symptoms if their treatment is based solely on in-office findings. Overtreatment of frail patients who often have marked orthostatic hypotension is an additional concern.

How to get more accurate readings

It’s clear that taking the treatments that led to optimal outcomes in clinical trials and applying them to clinic patients based on their office measurements is likely to result in overtreatment, leading to hypotension and endangering patients. The following steps, however, can ensure more accurate readings and thus, a proper starting place for treatment.

Use an oscillatory device. I suggest that clinical practices switch to oscillatory digital devices like those used in virtually all clinical research studies I’ve been involved in for the past 20 years. There are oscillatory digital devices designed for medical offices that automatically record BP readings. However, these are much more expensive.2 The home oscillatory devices I’m referring to can be purchased for each exam room, with various sized cuffs.

Go slow, repeat as needed. Have the rooming staff or medical assistant measure BP only after the patient interview is complete. The patient should sit down, with both feet on the floor, legs uncrossed.

If the reading is elevated, the staffer should show the patient how to repeat the measurement, then prepare to leave the room, advising him or her to sit quietly for 3 to 5 minutes before doing so. This method is both practical and time efficient. Occasionally, oscillometric measures result in an extremely elevated diastolic reading; in such a case, I recommend that a clinician manually remeasure BP.

Incorporate home monitoring. Out-of-office readings are important, not only for the initial diagnosis of hypertension, but for clinical management of established hypertension, as well.3 Guidelines from both the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) call for 24-hour ambulatory monitoring to establish a hypertension diagnosis.3,4 Accuracy is imperative, as this is commonly a lifelong diagnosis that should not be established based on a few, often inaccurately measured office readings.

Home monitoring improves BP control and correlates more closely with ambulatory monitoring than with office readings.5,6 I use an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Bellevue, Wash.) to have patients send me their home BP readings, but commercially available software programs, if available, and smart phone apps may be used instead.

My preference is to have patients measure and record their BP at breakfast and dinnertime (always after a 3-to-5-minute rest) for a month after any change in the medication regimen (FIGURE), and then send the chart to the office. (There are other protocols for how often and how long to monitor home BP, but this is the format I use.) Adjustments in medications can be continued based on the home readings until the goal is reached.

I advise all patients I treat for hypertension to check their BP on the first day of each month and record the measurements for review at their next office visit.

What to consider for optimal treatment

Screening patients for concurrent disease and hypertensive end-organ damage, of course, should be routine for primary care physicians. Baseline tests should include a complete blood count, electrolytes with creatinine clearance, and an electrocardiogram. A review of a recent echocardiogram and spot urine for microalbuminuria will also be useful, if clinically indicated.

Cost, compliance, and concurrent disease. Generic drugs with a long half-life to ensure 24-hour coverage are the optimal choice due to both cost and compliance. Some agents may be chosen because they also treat concurrent disease—a beta-blocker for a patient with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or migraines, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for diabetes, a diuretic for fluid overload, or spironolactone for systolic congestive heart failure.

Single agent or combination?

Most single drugs lower BP by approximately 10 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic, with 2-drug combinations lowering pressure by 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively.7 Amlodipine, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan medoxomil, all of which have long half-lives, are approximately 50% more potent than other antihypertensive agents.

When the target BP is a reduction ≥20/10 mm Hg, starting with dual drug therapy is often useful. In such cases, it is prudent not only to be sure that BP has been accurately measured, but to begin with half-tablet doses for several days to allow the patient to acclimate to the change in pressure. Beta-blockers, central sympatholytic drugs, direct vasodilators, and alpha antagonists are not considered first-, second-, or third-line agents.

Spironolactone, an aldosterone receptor antagonist, is very useful in resistant hypertension,8 defined as inadequate BP control despite a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and thiazide diuretic. (For more information, see "Resistant hypertension? Time to consider this fourth-line drug.") Patients on spironolactone require electrolyte monitoring due to the risks of hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, especially in combination with an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

I advocate monitoring such patients after one month, although every 2 weeks for at least the first 6 weeks of treatment is prudent for patients with CKD. Mild hyperkalemia (<5.5 mEq/L) or hyponatremia (>130 mEq/L) is well tolerated, but conditions associated with sudden dehydration, such as diarrhea or vomiting, can rapidly worsen these imbalances and be clinically significant.

Treatment algorithms can help

SPRINT and other hypertension trials have used algorithm-based drug additions to reach the desired goals. In SPRINT, one or more antihypertensive drug classes with the strongest evidence to prevent cardiovascular disease outcomes were initiated and adjusted at the discretion of the investigators. The initial drug classes were thiazide-type diuretics (chlorthalidone was preferred unless advanced CKD was present, and then loop diuretics), calcium channel blockers (amlodipine preferred), ACE inhibitors (lisinopril was preferred), and ARBs (losartan or azilsartan medoxomil preferred).

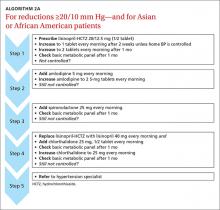

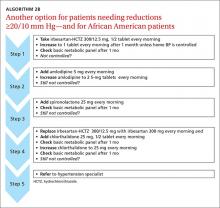

The algorithms in this article may be considered for the treatment of hypertension. They are based on my experience, as well as on guidance from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.9

ALGORITHM 1 is suitable for patients who initially need only 10/5 mm Hg lowering.10ALGORITHM 2A may be used for patients for whom you wish to lower BP by ≥20/10 mm Hg. I also recommend 2A for patients of Asian descent; that’s because ARBs are preferable to ACE inhibitors, which are associated with a high incidence of cough in this patient population. Either ALGORITHM 2A or 2B may be used for African-American patients with hypertension, as ACE inhibitors and ARBs alone are less effective for this group.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Yarows, MD, FACP, FASH, IHA Chelsea Family and Internal Medicine, 128 Van Buren St, Chelsea, MI 48118; [email protected].

1. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

2. Myers MG, Goodwin M, Dawes M, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in the office: recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension. 2010;55:195-200.

3. Siu A. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. McCormack T, Krause T. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:163-164.

5. Cuspidi C, Meani S, Fusi V, et al. Home blood pressure measurement and its relationship with blood pressure control in a large selected hypertensive population. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:725–731.

6. Mansoor GA, White WB. Self-measured home blood pressure in predicting ambulatory hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1017-1022.

7. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low-dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003:326:1427.

8. Bloch MJ, Basile JN. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to diagnose hypertension—an idea whose time has come. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:89-91.

9. National Institutes of Health. JNC 7 Express. The Seventh Report of the Joint Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/express.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2016.

10. Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with chlorthalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension. 2015;65:1041-1046.

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT),1 a study of more than 9000 patients published late last year, was stopped prematurely when it became clear that those receiving intensive treatment (systolic target 120 mm Hg) had significantly lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, cardiovascular death, and other severe heart disease than those getting standard treatment (systolic target 140 mm Hg). Participants had an elevated cardiovascular risk at baseline (age ≥75 years, history of cardiovascular disease [CVD], chronic kidney disease [CKD], or elevated 10-year Framingham CVD risk score ≥15%); those with diabetes, history of stroke, or polycystic kidney disease were excluded.

Although serious adverse events were not significantly different between the intensive and standard treatment groups, syncope, acute renal failure, electrolyte abnormalities, and hyponatremia were all statistically more common in the aggressively treated group. (To learn more, see “Is lower BP worth it in higher-risk patients with diabetes or coronary disease?” Clinical Inquiries, J Fam Pract. 2016;65:129-131.)

Taking an aggressive approach. This trial shined a light on an important topic in medicine—the aggressive treatment of hypertension. And while this article will not discuss the finer points of the SPRINT trial or the limitations of generalizing aggressive treatment to the broad population of patients with hypertension, it will outline important considerations for physicians who wish to aggressively treat hypertension. I offer recommendations based on my 34 years of clinical practice and experience as a co-investigator on a number of hypertension studies to help you better balance each patient’s risks (eg, age, frailty, fall risk) and potential benefits (prevention of stroke, MI, and congestive heart failure).

Taking an aggressive approach, however, starts with ensuring that the diagnosis and treatment are based on accurate measures.

How accurate are your BP readings?

Measuring BP in clinical practice is markedly different from measurements taken in a research setting.2 This can result in large, clinically significant differences in readings and adversely affect treatment decisions.

Quiet time, multiple readings

SPRINT used techniques similar to those followed by other hypertension outcomes studies I’ve been involved in—methods that are rare in medical practice. Each study participant sat quietly in a chair for 5 minutes prior to the first BP reading. In addition, the researchers used an automatic oscillatory BP device (Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, Ill), recording the average of 3 readings.

Practices that compromise accuracy. In clinical practice, BP is rarely measured after the patient has had 5 minutes of rest in a quiet room. Nor are readings done in triplicate. Instead, BP is typically measured while patient and clinician are engaged in conversation, often using a BP cuff that is too small (in my experience, most Americans require a large cuff).

BP is usually taken shortly after the patient has walked, frequently with some difficulty, from the waiting area to the exam room. Often, too, patients are weighed before their BP is measured, a common source of concern that can lead to a short-term rise in pressure. (Conversely, rapid deflation during the auscultatory measurement [>2 mm Hg/sec] can have the opposite effect, resulting in under-reading the true value.)

Compounding matters is the failure to consider the approximately 20% of patients who develop White Coat Syndrome. Such individuals, who typically have elevated office measurements but normal out-of-office readings, may develop further hypotensive symptoms if their treatment is based solely on in-office findings. Overtreatment of frail patients who often have marked orthostatic hypotension is an additional concern.

How to get more accurate readings

It’s clear that taking the treatments that led to optimal outcomes in clinical trials and applying them to clinic patients based on their office measurements is likely to result in overtreatment, leading to hypotension and endangering patients. The following steps, however, can ensure more accurate readings and thus, a proper starting place for treatment.

Use an oscillatory device. I suggest that clinical practices switch to oscillatory digital devices like those used in virtually all clinical research studies I’ve been involved in for the past 20 years. There are oscillatory digital devices designed for medical offices that automatically record BP readings. However, these are much more expensive.2 The home oscillatory devices I’m referring to can be purchased for each exam room, with various sized cuffs.

Go slow, repeat as needed. Have the rooming staff or medical assistant measure BP only after the patient interview is complete. The patient should sit down, with both feet on the floor, legs uncrossed.

If the reading is elevated, the staffer should show the patient how to repeat the measurement, then prepare to leave the room, advising him or her to sit quietly for 3 to 5 minutes before doing so. This method is both practical and time efficient. Occasionally, oscillometric measures result in an extremely elevated diastolic reading; in such a case, I recommend that a clinician manually remeasure BP.

Incorporate home monitoring. Out-of-office readings are important, not only for the initial diagnosis of hypertension, but for clinical management of established hypertension, as well.3 Guidelines from both the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) call for 24-hour ambulatory monitoring to establish a hypertension diagnosis.3,4 Accuracy is imperative, as this is commonly a lifelong diagnosis that should not be established based on a few, often inaccurately measured office readings.

Home monitoring improves BP control and correlates more closely with ambulatory monitoring than with office readings.5,6 I use an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Bellevue, Wash.) to have patients send me their home BP readings, but commercially available software programs, if available, and smart phone apps may be used instead.

My preference is to have patients measure and record their BP at breakfast and dinnertime (always after a 3-to-5-minute rest) for a month after any change in the medication regimen (FIGURE), and then send the chart to the office. (There are other protocols for how often and how long to monitor home BP, but this is the format I use.) Adjustments in medications can be continued based on the home readings until the goal is reached.

I advise all patients I treat for hypertension to check their BP on the first day of each month and record the measurements for review at their next office visit.

What to consider for optimal treatment

Screening patients for concurrent disease and hypertensive end-organ damage, of course, should be routine for primary care physicians. Baseline tests should include a complete blood count, electrolytes with creatinine clearance, and an electrocardiogram. A review of a recent echocardiogram and spot urine for microalbuminuria will also be useful, if clinically indicated.

Cost, compliance, and concurrent disease. Generic drugs with a long half-life to ensure 24-hour coverage are the optimal choice due to both cost and compliance. Some agents may be chosen because they also treat concurrent disease—a beta-blocker for a patient with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or migraines, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for diabetes, a diuretic for fluid overload, or spironolactone for systolic congestive heart failure.

Single agent or combination?

Most single drugs lower BP by approximately 10 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic, with 2-drug combinations lowering pressure by 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively.7 Amlodipine, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan medoxomil, all of which have long half-lives, are approximately 50% more potent than other antihypertensive agents.

When the target BP is a reduction ≥20/10 mm Hg, starting with dual drug therapy is often useful. In such cases, it is prudent not only to be sure that BP has been accurately measured, but to begin with half-tablet doses for several days to allow the patient to acclimate to the change in pressure. Beta-blockers, central sympatholytic drugs, direct vasodilators, and alpha antagonists are not considered first-, second-, or third-line agents.

Spironolactone, an aldosterone receptor antagonist, is very useful in resistant hypertension,8 defined as inadequate BP control despite a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and thiazide diuretic. (For more information, see "Resistant hypertension? Time to consider this fourth-line drug.") Patients on spironolactone require electrolyte monitoring due to the risks of hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, especially in combination with an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

I advocate monitoring such patients after one month, although every 2 weeks for at least the first 6 weeks of treatment is prudent for patients with CKD. Mild hyperkalemia (<5.5 mEq/L) or hyponatremia (>130 mEq/L) is well tolerated, but conditions associated with sudden dehydration, such as diarrhea or vomiting, can rapidly worsen these imbalances and be clinically significant.

Treatment algorithms can help

SPRINT and other hypertension trials have used algorithm-based drug additions to reach the desired goals. In SPRINT, one or more antihypertensive drug classes with the strongest evidence to prevent cardiovascular disease outcomes were initiated and adjusted at the discretion of the investigators. The initial drug classes were thiazide-type diuretics (chlorthalidone was preferred unless advanced CKD was present, and then loop diuretics), calcium channel blockers (amlodipine preferred), ACE inhibitors (lisinopril was preferred), and ARBs (losartan or azilsartan medoxomil preferred).

The algorithms in this article may be considered for the treatment of hypertension. They are based on my experience, as well as on guidance from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.9

ALGORITHM 1 is suitable for patients who initially need only 10/5 mm Hg lowering.10ALGORITHM 2A may be used for patients for whom you wish to lower BP by ≥20/10 mm Hg. I also recommend 2A for patients of Asian descent; that’s because ARBs are preferable to ACE inhibitors, which are associated with a high incidence of cough in this patient population. Either ALGORITHM 2A or 2B may be used for African-American patients with hypertension, as ACE inhibitors and ARBs alone are less effective for this group.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Yarows, MD, FACP, FASH, IHA Chelsea Family and Internal Medicine, 128 Van Buren St, Chelsea, MI 48118; [email protected].

The Systolic Blood Pressure Intervention Trial (SPRINT),1 a study of more than 9000 patients published late last year, was stopped prematurely when it became clear that those receiving intensive treatment (systolic target 120 mm Hg) had significantly lower rates of myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, cardiovascular death, and other severe heart disease than those getting standard treatment (systolic target 140 mm Hg). Participants had an elevated cardiovascular risk at baseline (age ≥75 years, history of cardiovascular disease [CVD], chronic kidney disease [CKD], or elevated 10-year Framingham CVD risk score ≥15%); those with diabetes, history of stroke, or polycystic kidney disease were excluded.

Although serious adverse events were not significantly different between the intensive and standard treatment groups, syncope, acute renal failure, electrolyte abnormalities, and hyponatremia were all statistically more common in the aggressively treated group. (To learn more, see “Is lower BP worth it in higher-risk patients with diabetes or coronary disease?” Clinical Inquiries, J Fam Pract. 2016;65:129-131.)

Taking an aggressive approach. This trial shined a light on an important topic in medicine—the aggressive treatment of hypertension. And while this article will not discuss the finer points of the SPRINT trial or the limitations of generalizing aggressive treatment to the broad population of patients with hypertension, it will outline important considerations for physicians who wish to aggressively treat hypertension. I offer recommendations based on my 34 years of clinical practice and experience as a co-investigator on a number of hypertension studies to help you better balance each patient’s risks (eg, age, frailty, fall risk) and potential benefits (prevention of stroke, MI, and congestive heart failure).

Taking an aggressive approach, however, starts with ensuring that the diagnosis and treatment are based on accurate measures.

How accurate are your BP readings?

Measuring BP in clinical practice is markedly different from measurements taken in a research setting.2 This can result in large, clinically significant differences in readings and adversely affect treatment decisions.

Quiet time, multiple readings

SPRINT used techniques similar to those followed by other hypertension outcomes studies I’ve been involved in—methods that are rare in medical practice. Each study participant sat quietly in a chair for 5 minutes prior to the first BP reading. In addition, the researchers used an automatic oscillatory BP device (Omron Healthcare, Lake Forest, Ill), recording the average of 3 readings.

Practices that compromise accuracy. In clinical practice, BP is rarely measured after the patient has had 5 minutes of rest in a quiet room. Nor are readings done in triplicate. Instead, BP is typically measured while patient and clinician are engaged in conversation, often using a BP cuff that is too small (in my experience, most Americans require a large cuff).

BP is usually taken shortly after the patient has walked, frequently with some difficulty, from the waiting area to the exam room. Often, too, patients are weighed before their BP is measured, a common source of concern that can lead to a short-term rise in pressure. (Conversely, rapid deflation during the auscultatory measurement [>2 mm Hg/sec] can have the opposite effect, resulting in under-reading the true value.)

Compounding matters is the failure to consider the approximately 20% of patients who develop White Coat Syndrome. Such individuals, who typically have elevated office measurements but normal out-of-office readings, may develop further hypotensive symptoms if their treatment is based solely on in-office findings. Overtreatment of frail patients who often have marked orthostatic hypotension is an additional concern.

How to get more accurate readings

It’s clear that taking the treatments that led to optimal outcomes in clinical trials and applying them to clinic patients based on their office measurements is likely to result in overtreatment, leading to hypotension and endangering patients. The following steps, however, can ensure more accurate readings and thus, a proper starting place for treatment.

Use an oscillatory device. I suggest that clinical practices switch to oscillatory digital devices like those used in virtually all clinical research studies I’ve been involved in for the past 20 years. There are oscillatory digital devices designed for medical offices that automatically record BP readings. However, these are much more expensive.2 The home oscillatory devices I’m referring to can be purchased for each exam room, with various sized cuffs.

Go slow, repeat as needed. Have the rooming staff or medical assistant measure BP only after the patient interview is complete. The patient should sit down, with both feet on the floor, legs uncrossed.

If the reading is elevated, the staffer should show the patient how to repeat the measurement, then prepare to leave the room, advising him or her to sit quietly for 3 to 5 minutes before doing so. This method is both practical and time efficient. Occasionally, oscillometric measures result in an extremely elevated diastolic reading; in such a case, I recommend that a clinician manually remeasure BP.

Incorporate home monitoring. Out-of-office readings are important, not only for the initial diagnosis of hypertension, but for clinical management of established hypertension, as well.3 Guidelines from both the US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) and the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) call for 24-hour ambulatory monitoring to establish a hypertension diagnosis.3,4 Accuracy is imperative, as this is commonly a lifelong diagnosis that should not be established based on a few, often inaccurately measured office readings.

Home monitoring improves BP control and correlates more closely with ambulatory monitoring than with office readings.5,6 I use an Excel spreadsheet (Microsoft, Bellevue, Wash.) to have patients send me their home BP readings, but commercially available software programs, if available, and smart phone apps may be used instead.

My preference is to have patients measure and record their BP at breakfast and dinnertime (always after a 3-to-5-minute rest) for a month after any change in the medication regimen (FIGURE), and then send the chart to the office. (There are other protocols for how often and how long to monitor home BP, but this is the format I use.) Adjustments in medications can be continued based on the home readings until the goal is reached.

I advise all patients I treat for hypertension to check their BP on the first day of each month and record the measurements for review at their next office visit.

What to consider for optimal treatment

Screening patients for concurrent disease and hypertensive end-organ damage, of course, should be routine for primary care physicians. Baseline tests should include a complete blood count, electrolytes with creatinine clearance, and an electrocardiogram. A review of a recent echocardiogram and spot urine for microalbuminuria will also be useful, if clinically indicated.

Cost, compliance, and concurrent disease. Generic drugs with a long half-life to ensure 24-hour coverage are the optimal choice due to both cost and compliance. Some agents may be chosen because they also treat concurrent disease—a beta-blocker for a patient with heart failure with reduced ejection fraction or migraines, an angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor/angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB) for diabetes, a diuretic for fluid overload, or spironolactone for systolic congestive heart failure.

Single agent or combination?

Most single drugs lower BP by approximately 10 mm Hg systolic and 5 mm Hg diastolic, with 2-drug combinations lowering pressure by 20 mm Hg and 10 mm Hg, respectively.7 Amlodipine, chlorthalidone, and azilsartan medoxomil, all of which have long half-lives, are approximately 50% more potent than other antihypertensive agents.

When the target BP is a reduction ≥20/10 mm Hg, starting with dual drug therapy is often useful. In such cases, it is prudent not only to be sure that BP has been accurately measured, but to begin with half-tablet doses for several days to allow the patient to acclimate to the change in pressure. Beta-blockers, central sympatholytic drugs, direct vasodilators, and alpha antagonists are not considered first-, second-, or third-line agents.

Spironolactone, an aldosterone receptor antagonist, is very useful in resistant hypertension,8 defined as inadequate BP control despite a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and thiazide diuretic. (For more information, see "Resistant hypertension? Time to consider this fourth-line drug.") Patients on spironolactone require electrolyte monitoring due to the risks of hyponatremia and hyperkalemia, especially in combination with an ACE inhibitor or ARB.

I advocate monitoring such patients after one month, although every 2 weeks for at least the first 6 weeks of treatment is prudent for patients with CKD. Mild hyperkalemia (<5.5 mEq/L) or hyponatremia (>130 mEq/L) is well tolerated, but conditions associated with sudden dehydration, such as diarrhea or vomiting, can rapidly worsen these imbalances and be clinically significant.

Treatment algorithms can help

SPRINT and other hypertension trials have used algorithm-based drug additions to reach the desired goals. In SPRINT, one or more antihypertensive drug classes with the strongest evidence to prevent cardiovascular disease outcomes were initiated and adjusted at the discretion of the investigators. The initial drug classes were thiazide-type diuretics (chlorthalidone was preferred unless advanced CKD was present, and then loop diuretics), calcium channel blockers (amlodipine preferred), ACE inhibitors (lisinopril was preferred), and ARBs (losartan or azilsartan medoxomil preferred).

The algorithms in this article may be considered for the treatment of hypertension. They are based on my experience, as well as on guidance from the Seventh Report of the Joint National Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure.9

ALGORITHM 1 is suitable for patients who initially need only 10/5 mm Hg lowering.10ALGORITHM 2A may be used for patients for whom you wish to lower BP by ≥20/10 mm Hg. I also recommend 2A for patients of Asian descent; that’s because ARBs are preferable to ACE inhibitors, which are associated with a high incidence of cough in this patient population. Either ALGORITHM 2A or 2B may be used for African-American patients with hypertension, as ACE inhibitors and ARBs alone are less effective for this group.

CORRESPONDENCE

Steven Yarows, MD, FACP, FASH, IHA Chelsea Family and Internal Medicine, 128 Van Buren St, Chelsea, MI 48118; [email protected].

1. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

2. Myers MG, Goodwin M, Dawes M, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in the office: recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension. 2010;55:195-200.

3. Siu A. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. McCormack T, Krause T. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:163-164.

5. Cuspidi C, Meani S, Fusi V, et al. Home blood pressure measurement and its relationship with blood pressure control in a large selected hypertensive population. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:725–731.

6. Mansoor GA, White WB. Self-measured home blood pressure in predicting ambulatory hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1017-1022.

7. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low-dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003:326:1427.

8. Bloch MJ, Basile JN. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to diagnose hypertension—an idea whose time has come. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:89-91.

9. National Institutes of Health. JNC 7 Express. The Seventh Report of the Joint Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/express.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2016.

10. Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with chlorthalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension. 2015;65:1041-1046.

1. SPRINT Research Group, Wright JT, Williamson JD, Whelton PK, et al. A randomized trial of intensive versus standard blood-pressure control. N Engl J Med. 2015;373:2103-2116.

2. Myers MG, Goodwin M, Dawes M, et al. Measurement of blood pressure in the office: recognizing the problem and proposing the solution. Hypertension. 2010;55:195-200.

3. Siu A. Screening for high blood pressure in adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. Ann Intern Med. 2015;163:778-786.

4. McCormack T, Krause T. Management of hypertension in adults in primary care: NICE guideline. Br J Gen Pract. 2012;62:163-164.

5. Cuspidi C, Meani S, Fusi V, et al. Home blood pressure measurement and its relationship with blood pressure control in a large selected hypertensive population. J Hum Hypertens. 2004;18:725–731.

6. Mansoor GA, White WB. Self-measured home blood pressure in predicting ambulatory hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2004;17:1017-1022.

7. Law MR, Wald NJ, Morris JK, et al. Value of low-dose combination treatment with blood pressure lowering drugs: analysis of 354 randomised trials. BMJ. 2003:326:1427.

8. Bloch MJ, Basile JN. Ambulatory blood pressure monitoring to diagnose hypertension—an idea whose time has come. J Am Soc Hypertens. 2016;10:89-91.

9. National Institutes of Health. JNC 7 Express. The Seventh Report of the Joint Committee on Prevention, Detection, Evaluation, and Treatment of High Blood Pressure. Available at: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/files/docs/guidelines/express.pdf. Accessed February 26, 2016.

10. Roush GC, Ernst ME, Kostis JB, et al. Head-to-head comparisons of hydrochlorothiazide with chlorthalidone: antihypertensive and metabolic effects. Hypertension. 2015;65:1041-1046.

Resistant hypertension? Time to consider this fourth-line drug

When a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic fails to achieve the target blood pressure, try adding spironolactone.

Strength of recommendation

C: Based on a high-quality disease-oriented randomized controlled trial.1

Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2059–2068.

Illustrative case

Willie S, a 56-year-old with chronic essential hypertension, has been on an optimally dosed 3-drug regimen of an ACE inhibitor, a calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic for more than 3 months, but his blood pressure is still not at goal.

What is the best antihypertensive agent to add to his regimen?

Resistant hypertension—defined as inadequate blood pressure (BP) control despite a triple regimen of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker (CCB), and thiazide diuretic—affects an estimated 5% to 30% of those being treated for hypertension.1,2 Guidelines from the 8th Joint National Committee (JNC-8) on the management of high BP, released in 2014, recommend beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or aldosterone antagonists (AAs) as equivalent choices for a fourth-line agent. The recommendation is based on expert opinion.3

Hypertension guidelines from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, released in 2011, recommend an AA if BP targets have not been met with the triple regimen. This recommendation, however, is based on lower-quality evidence, without comparison with beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or other drug classes.4

More evidence since guideline’s release

A 2015 meta-analysis of 15 studies and a total of more than 1200 participants (3 randomized controlled trials [RCTs], one nonrandomized placebo-controlled comparative trial, and 11 single-arm observational studies) demonstrated the effectiveness of the AAs spironolactone and eplerenone on resistant hypertension.5 In the 4 comparative studies, AAs decreased office systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 24.3 mm Hg (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.65-39.87; P=.002) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) by 7.8 mm Hg (95% CI, 3.79-11.79; P=.0001) more than placebo. In the 11 single arm studies, AAs reduced SBP by 22.74 mm Hg (95% CI, 18.21-27.27; P <.00001), and DBP by 10.49 mm Hg (95% CI, 8.85–12.13; P <.00001).

The previous year, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial examined the effect of low-dose (25 mg) spironolactone compared with placebo in 161 patients with resistant hypertension.6 At 8 weeks, 73% of those receiving spironolactone reached a goal SBP <140 mm Hg vs 41% of patients on placebo (P=.001). The same proportion (73%) achieved a goal DBP <90 mm Hg in the spironolactone group, compared with 63% of those in the placebo group (P=.223).

Ambulatory BP was likewise assessed and found to be significantly improved among those receiving spironolactone vs placebo, with a decrease in SBP of 9.8 mm Hg (95% CI, -14.2 to -5.4; P<.001), and a 3.2 mm Hg decline in DBP (95% CI, -5.9 to -0.5; P=.013).6

STUDY SUMMARY

First study to compare spironolactone with other drugs

The study by Williams et al—a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial conducted in the UK—was the first RCT to directly compare spironolactone with other medications for the treatment of resistant hypertension in adults already on triple therapy with an ACE inhibitor or ARB, a CCB, and a thiazide diuretic.1 The trial randomized 335 individuals with a mean age of 61.4 years (age range 18 to 79), 69% of whom were male; 314 were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.1

Enrollment criteria for resistant hypertension specified a clinic-recorded SBP of ≥140 mm Hg (or ≥135 mm Hg in those with diabetes) and home SBP (in 18 readings over 4 days) of ≥130 mm Hg.1 To ensure fidelity to treatment protocols, the investigators directly observed therapy, took tablet counts, measured serum ACE activity, and assessed BP measurement technique, with all participants adhering to a minimum of 3 months on a maximally dosed triple regimen.

Diabetes prevalence was 14%; tobacco use was 7.8%; and average weight was 93.5 kg (205.7 lbs).1 Because of the expected inverse relationship between plasma renin and response to AAs, plasma renin was measured at baseline to test whether resistant hypertension was primarily due to sodium retention.1

Participants underwent 4, 12-week rotations

All participants began the trial with 4 weeks of placebo, followed by randomization to 12-week rotations of once daily oral treatment with 1) spironolactone 25 to 50 mg, 2) doxazosin modified release 4 to 8 mg, 3) bisoprolol 5 to 10 mg, and 4) placebo.1 Six weeks after initiation of each study medication, participants were titrated to the higher dose. There was no washout period between cycles.

The primary outcome was mean SBP measured at home on 4 consecutive days prior to the study visits on Weeks 6 and 12. Participants were required to have at least 6 BP measurements per each 6-week period in order to establish a valid average. Primary endpoints included: the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and placebo, the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and the mean of the other 2 drugs, and the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and each of the other 2 drugs.

The results: Spironolactone lowered SBP more than placebo, doxazosin, and bisoprolol (TABLE),1 and clinic measurements were consistent with home BP readings.

Overall, 58% of participants achieved goal SBP <135 mm Hg on spironolactone, compared with 42% on doxazosin, 44% on bisoprolol, and 24% on placebo.1 The effectiveness of spironolactone on SBP reduction was shown to exhibit an inverse relationship to plasma renin levels, a finding that was not apparent with the other 2 study drugs. However, spironolactone had a superior BP lowering effect throughout nearly the entire renin distribution of the cohort. The mean difference between spironolactone and placebo was -10.2 mm Hg; compared with the other drugs, spironolactone lowered SBP, on average, by 5.64 mm Hg more than bisoprolol and doxazosin; 5.3 mm Hg more than doxazosin alone, and 5.98 mm Hg more than bisoprolol alone.

Only 1% of trial participants had to discontinue spironolactone due to adverse events—the same proportion of withdrawals as that for bisoprolol and placebo and 3 times less than for doxazosin.1

WHAT’S NEW

Evidence of spironolactone’s superiority

This is the first RCT to compare spironolactone with 2 other commonly used fourth-line antihypertensives—bisoprolol and doxazosin—in patients with resistant hypertension. The study demonstrated clear superiority of spironolactone in achieving carefully measured ambulatory and clinic-recorded BP targets vs a beta-blocker or an alpha-blocker.

CAVEATS

Findings do not apply across the board

Spironolactone is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment. Although multiple drug trials have demonstrated the drug’s safety and effectiveness, especially in patients with resistant hypertension, we should factor in the need for monitoring electrolytes and renal function within weeks of initiating treatment and periodically thereafter.7,8 In this study, spironolactone increased potassium levels, on average, by 0.45 mmol/L. No gynecomastia (typically seen in about 6% of men) was found in those taking spironolactone for a 12-week cycle.1

This single trial enrolled mostly Caucasian men with a mean age of 61 years. Although smaller observational studies that included African American patients have shown promising results for spironolactone, the question of external validity or applicability to a diverse population has yet to be decisively answered.9

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential for adverse reactions, lack of patient-oriented results

The evidence supporting this change in practice has been accumulating for the past few years. However, physicians treating patients with resistant hypertension may have concerns about hyperkalemia, gynecomastia, and effects on renal function. More patient-oriented evidence is likewise needed to assist with the revision of guidelines and wider adoption of AAs by primary care providers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

1. Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2059-2068.

2. Rosa J, Widimsky P, Tousek P, et al. Randomized comparison of renal denervation versus intensified pharmacotherapy including spironolactone in true-resistant hypertension: six-month results from the Prague-15 Study. Hypertension. 2015;65:407-413.

3. James PA, Oparil S, Carter BL, et al. 2014 evidence-based guideline for the management of high blood pressure in adults. JAMA. 2014;311:507-520.

4. Hypertension in adults: diagnosis and management (Clinical Guideline CG127). (NICE), National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2011. Available at: https://www.nice.org.uk/guidance/cg127. Accessed March 4, 2016.

5. Dahal K, Kunwar S, Rijal J, et al. The effects of aldosterone antagonists in patients with resistant hypertension: a meta-analysis of randomized and nonrandomized studies. Am J Hypertens. 2015;28:1376-1385.

6. Václavík J, Sedlák R, Jarkovský J, et al. Effect of spironolactone in resistant arterial hypertension: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial (ASPIRANT-EXT). Medicine (Baltimore). 2014;93:e162.

7. Wei L, Struthers AD, Fahey T, et al. Spironolactone use and renal toxicity: population based longitudinal analysis. BMJ. 2010;340:c1768.

8. Oxlund CS, Henriksen JE, Tarnow L, et al. Low dose spironolactone reduces blood pressure in patients with resistant hypertension and type 2 diabetes mellitus. J Hypertens. 2013;31:2094-2102.

9. Nishizaka M, Zaman MA, Calhoun DA. Efficacy of low-dose spironolactone in subjects with resistant hypertension. Am J Hypertens. 2003;16:925-930.

When a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic fails to achieve the target blood pressure, try adding spironolactone.

Strength of recommendation

C: Based on a high-quality disease-oriented randomized controlled trial.1

Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2059–2068.

Illustrative case

Willie S, a 56-year-old with chronic essential hypertension, has been on an optimally dosed 3-drug regimen of an ACE inhibitor, a calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic for more than 3 months, but his blood pressure is still not at goal.

What is the best antihypertensive agent to add to his regimen?

Resistant hypertension—defined as inadequate blood pressure (BP) control despite a triple regimen of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker (CCB), and thiazide diuretic—affects an estimated 5% to 30% of those being treated for hypertension.1,2 Guidelines from the 8th Joint National Committee (JNC-8) on the management of high BP, released in 2014, recommend beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or aldosterone antagonists (AAs) as equivalent choices for a fourth-line agent. The recommendation is based on expert opinion.3

Hypertension guidelines from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, released in 2011, recommend an AA if BP targets have not been met with the triple regimen. This recommendation, however, is based on lower-quality evidence, without comparison with beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or other drug classes.4

More evidence since guideline’s release

A 2015 meta-analysis of 15 studies and a total of more than 1200 participants (3 randomized controlled trials [RCTs], one nonrandomized placebo-controlled comparative trial, and 11 single-arm observational studies) demonstrated the effectiveness of the AAs spironolactone and eplerenone on resistant hypertension.5 In the 4 comparative studies, AAs decreased office systolic blood pressure (SBP) by 24.3 mm Hg (95% confidence interval [CI], 8.65-39.87; P=.002) and diastolic blood pressure (DBP) by 7.8 mm Hg (95% CI, 3.79-11.79; P=.0001) more than placebo. In the 11 single arm studies, AAs reduced SBP by 22.74 mm Hg (95% CI, 18.21-27.27; P <.00001), and DBP by 10.49 mm Hg (95% CI, 8.85–12.13; P <.00001).

The previous year, a randomized, placebo-controlled trial examined the effect of low-dose (25 mg) spironolactone compared with placebo in 161 patients with resistant hypertension.6 At 8 weeks, 73% of those receiving spironolactone reached a goal SBP <140 mm Hg vs 41% of patients on placebo (P=.001). The same proportion (73%) achieved a goal DBP <90 mm Hg in the spironolactone group, compared with 63% of those in the placebo group (P=.223).

Ambulatory BP was likewise assessed and found to be significantly improved among those receiving spironolactone vs placebo, with a decrease in SBP of 9.8 mm Hg (95% CI, -14.2 to -5.4; P<.001), and a 3.2 mm Hg decline in DBP (95% CI, -5.9 to -0.5; P=.013).6

STUDY SUMMARY

First study to compare spironolactone with other drugs

The study by Williams et al—a double-blind, randomized placebo-controlled crossover trial conducted in the UK—was the first RCT to directly compare spironolactone with other medications for the treatment of resistant hypertension in adults already on triple therapy with an ACE inhibitor or ARB, a CCB, and a thiazide diuretic.1 The trial randomized 335 individuals with a mean age of 61.4 years (age range 18 to 79), 69% of whom were male; 314 were included in the intention-to-treat analysis.1

Enrollment criteria for resistant hypertension specified a clinic-recorded SBP of ≥140 mm Hg (or ≥135 mm Hg in those with diabetes) and home SBP (in 18 readings over 4 days) of ≥130 mm Hg.1 To ensure fidelity to treatment protocols, the investigators directly observed therapy, took tablet counts, measured serum ACE activity, and assessed BP measurement technique, with all participants adhering to a minimum of 3 months on a maximally dosed triple regimen.

Diabetes prevalence was 14%; tobacco use was 7.8%; and average weight was 93.5 kg (205.7 lbs).1 Because of the expected inverse relationship between plasma renin and response to AAs, plasma renin was measured at baseline to test whether resistant hypertension was primarily due to sodium retention.1

Participants underwent 4, 12-week rotations

All participants began the trial with 4 weeks of placebo, followed by randomization to 12-week rotations of once daily oral treatment with 1) spironolactone 25 to 50 mg, 2) doxazosin modified release 4 to 8 mg, 3) bisoprolol 5 to 10 mg, and 4) placebo.1 Six weeks after initiation of each study medication, participants were titrated to the higher dose. There was no washout period between cycles.

The primary outcome was mean SBP measured at home on 4 consecutive days prior to the study visits on Weeks 6 and 12. Participants were required to have at least 6 BP measurements per each 6-week period in order to establish a valid average. Primary endpoints included: the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and placebo, the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and the mean of the other 2 drugs, and the difference in home SBP between spironolactone and each of the other 2 drugs.

The results: Spironolactone lowered SBP more than placebo, doxazosin, and bisoprolol (TABLE),1 and clinic measurements were consistent with home BP readings.

Overall, 58% of participants achieved goal SBP <135 mm Hg on spironolactone, compared with 42% on doxazosin, 44% on bisoprolol, and 24% on placebo.1 The effectiveness of spironolactone on SBP reduction was shown to exhibit an inverse relationship to plasma renin levels, a finding that was not apparent with the other 2 study drugs. However, spironolactone had a superior BP lowering effect throughout nearly the entire renin distribution of the cohort. The mean difference between spironolactone and placebo was -10.2 mm Hg; compared with the other drugs, spironolactone lowered SBP, on average, by 5.64 mm Hg more than bisoprolol and doxazosin; 5.3 mm Hg more than doxazosin alone, and 5.98 mm Hg more than bisoprolol alone.

Only 1% of trial participants had to discontinue spironolactone due to adverse events—the same proportion of withdrawals as that for bisoprolol and placebo and 3 times less than for doxazosin.1

WHAT’S NEW

Evidence of spironolactone’s superiority

This is the first RCT to compare spironolactone with 2 other commonly used fourth-line antihypertensives—bisoprolol and doxazosin—in patients with resistant hypertension. The study demonstrated clear superiority of spironolactone in achieving carefully measured ambulatory and clinic-recorded BP targets vs a beta-blocker or an alpha-blocker.

CAVEATS

Findings do not apply across the board

Spironolactone is contraindicated in patients with severe renal impairment. Although multiple drug trials have demonstrated the drug’s safety and effectiveness, especially in patients with resistant hypertension, we should factor in the need for monitoring electrolytes and renal function within weeks of initiating treatment and periodically thereafter.7,8 In this study, spironolactone increased potassium levels, on average, by 0.45 mmol/L. No gynecomastia (typically seen in about 6% of men) was found in those taking spironolactone for a 12-week cycle.1

This single trial enrolled mostly Caucasian men with a mean age of 61 years. Although smaller observational studies that included African American patients have shown promising results for spironolactone, the question of external validity or applicability to a diverse population has yet to be decisively answered.9

CHALLENGES TO IMPLEMENTATION

Potential for adverse reactions, lack of patient-oriented results

The evidence supporting this change in practice has been accumulating for the past few years. However, physicians treating patients with resistant hypertension may have concerns about hyperkalemia, gynecomastia, and effects on renal function. More patient-oriented evidence is likewise needed to assist with the revision of guidelines and wider adoption of AAs by primary care providers.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

The PURLs Surveillance System was supported in part by Grant Number UL1RR024999 from the National Center For Research Resources, a Clinical Translational Science Award to the University of Chicago. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Center For Research Resources or the National Institutes of Health.

When a triple regimen of an ACE inhibitor or ARB, calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic fails to achieve the target blood pressure, try adding spironolactone.

Strength of recommendation

C: Based on a high-quality disease-oriented randomized controlled trial.1

Williams B, MacDonald TM, Morant S, et al. Spironolactone versus placebo, bisoprolol, and doxazosin to determine the optimal treatment for drug-resistant hypertension (PATHWAY-2): a randomised, double-blind, crossover trial. Lancet. 2015;386:2059–2068.

Illustrative case

Willie S, a 56-year-old with chronic essential hypertension, has been on an optimally dosed 3-drug regimen of an ACE inhibitor, a calcium channel blocker, and a thiazide diuretic for more than 3 months, but his blood pressure is still not at goal.

What is the best antihypertensive agent to add to his regimen?

Resistant hypertension—defined as inadequate blood pressure (BP) control despite a triple regimen of angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitor or angiotensin receptor blocker (ARB), calcium channel blocker (CCB), and thiazide diuretic—affects an estimated 5% to 30% of those being treated for hypertension.1,2 Guidelines from the 8th Joint National Committee (JNC-8) on the management of high BP, released in 2014, recommend beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or aldosterone antagonists (AAs) as equivalent choices for a fourth-line agent. The recommendation is based on expert opinion.3

Hypertension guidelines from the UK’s National Institute for Health and Care Excellence, released in 2011, recommend an AA if BP targets have not been met with the triple regimen. This recommendation, however, is based on lower-quality evidence, without comparison with beta-blockers, alpha-blockers, or other drug classes.4

More evidence since guideline’s release