User login

Infliximab fails as salvage treatment for severe ulcerative colitis

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

LOS ANGELES – The inpatient use of infliximab for severe ulcerative colitis does not avoid the need for colectomy in patients who fail steroid therapy, results from a single-center study demonstrated.

In an interview at the annual meeting of the American Society of Colon and Rectal Surgeons, lead study author Dr. Rachel E. Andrew, a third-year resident in the department of surgery at Penn State Hershey Medical Center in Hershey, Pa., said that despite recent interest in providing inpatient infliximab as an alternative to surgery for those with steroid-refractory disease, 82% of those who received salvage infliximab went on to undergo a total abdominal colectomy during the same admission.

“Our findings suggest that inpatient infliximab was not effective at improving the severity of colitis in these patients,” she said. “Further, infliximab was unreliable in avoiding the need for a total colectomy in this population of ulcerative colitis patients. One difference between our study and those previously published on this subject is that our study focuses on patients with a severity of colitis that resulted in their admission to a surgery service. In terms of evaluating the benefit of infliximab and providing a reliable avoidance of colectomy, we feel that this population of ulcerative colitis patients would be most appropriate to evaluate this issue. This possible difference in patient population may explain the difference in our study findings and those previously published.”

The researchers compared colectomy rates in 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center. Their mean age was 41 years, with 155 (90%) treated with high-dose steroids alone, and with 18 (10%) having received inpatient infliximab as salvage therapy due to a lack of response to steroids alone. Of the patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

The researchers observed no statistically significant differences between the two groups regarding rates of hospital readmission, superficial, deep and organ space surgical-site infections, unplanned return to the operating room, and all complication rates (P greater than .05). Among patients who required total colectomy, hospital costs were 27% higher among those who received infliximab compared with those who received high-dose steroids alone (a mean of $19,880 vs. $14,492, respectively), but because of the small sample size of the infliximab cohort this difference did not reach statistical significance.

“In our institution, salvage infliximab has not been shown to be effective,” Dr. Andrew said. “One key difference between our findings and other studies is that our study population had a high colectomy rate; 82% is much higher than the approximately 30% colectomy rate described in many reports from colleagues in gastroenterology. While there are several potential explanations for our higher rate of colectomy, including the potential concerns that surgeons might be inclined to opt for surgery more readily than non-surgical providers, it is likely that the patients in our study had more severe forms of colitis. It might be the case that there are certain severities of colitis that are beyond the ability of infliximab to salvage, which would be an important issue in selecting which patients to provide inpatient infliximab, so as to not unnecessarily delay surgery, increase hospital costs and to avoid escalating the degree of immunosuppression without a reasonable likelihood of clinical improvement.”

Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

AT THE ASCRS ANNUAL MEETING

Key clinical point: Infliximab was not effective as inpatient salvage therapy for severe ulcerative colitis.

Major finding: Of patients who received high-dose steroids alone, 81 (52%) required total colectomy, compared with 14 (82%) who received infliximab salvage therapy (P = .046).

Data source: A study of 173 patients with severe ulcerative colitis who were admitted to the colorectal surgery service at Penn State Hershey Medical Center.

Disclosures: Dr. Andrew reported having no financial disclosures.

Troponin Leak Portends Poorer Outcomes in Congestive Heart Disease Hospitalizations

Clinical question: What is the association between detectable cardiac troponin (cTn) levels and outcomes in persons hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: There are millions of ADHF hospitalizations per year, and all-cause mortality and readmission rates are high. Efforts to better risk-stratify such patients have included measuring cTn levels and determining risk of increased length of stay, hospital readmission, and mortality.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-six observational cohort studies.

Synopsis: Compared with an undetectable cTn, detectable or elevated cTn levels were associated with greater length of stay (odds ratio [OR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01¬–1.10) and greater in-hospital death (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.27–2.91). ADHF patients with detectable or elevated cTn were also at increased risk for mortality and composite of mortality and readmission over the short, intermediate, and long term. Reviewers eventually considered the overall association of a detectable or elevated troponin with mortality and readmission as moderate (relative association measure >2.0).

Meanwhile, few studies in this analysis showed a continuous and graded relationship between cTn levels and clinical outcomes.

Limitations of the review include arbitrarily stratifying groups by the level of cTn from assays whose lower limit of detection vary. The authors also admit the various associations are likely affected by several confounders for which they could not adjust because individual participant data were unavailable.

Finally, while acknowledging patients with chronic stable heart failure often have baseline elevated cTn levels, accounting for this in the analysis was limited.

Bottom line: A detectable or elevated level of cTn during ADHF hospitalization leads to worse outcomes both during and after discharge.

Citation: Yousufuddin M, Abdalrhim AD, Wang Z, Murad MH. Cardiac troponin in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print February 18, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2558.

Clinical question: What is the association between detectable cardiac troponin (cTn) levels and outcomes in persons hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: There are millions of ADHF hospitalizations per year, and all-cause mortality and readmission rates are high. Efforts to better risk-stratify such patients have included measuring cTn levels and determining risk of increased length of stay, hospital readmission, and mortality.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-six observational cohort studies.

Synopsis: Compared with an undetectable cTn, detectable or elevated cTn levels were associated with greater length of stay (odds ratio [OR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01¬–1.10) and greater in-hospital death (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.27–2.91). ADHF patients with detectable or elevated cTn were also at increased risk for mortality and composite of mortality and readmission over the short, intermediate, and long term. Reviewers eventually considered the overall association of a detectable or elevated troponin with mortality and readmission as moderate (relative association measure >2.0).

Meanwhile, few studies in this analysis showed a continuous and graded relationship between cTn levels and clinical outcomes.

Limitations of the review include arbitrarily stratifying groups by the level of cTn from assays whose lower limit of detection vary. The authors also admit the various associations are likely affected by several confounders for which they could not adjust because individual participant data were unavailable.

Finally, while acknowledging patients with chronic stable heart failure often have baseline elevated cTn levels, accounting for this in the analysis was limited.

Bottom line: A detectable or elevated level of cTn during ADHF hospitalization leads to worse outcomes both during and after discharge.

Citation: Yousufuddin M, Abdalrhim AD, Wang Z, Murad MH. Cardiac troponin in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print February 18, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2558.

Clinical question: What is the association between detectable cardiac troponin (cTn) levels and outcomes in persons hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF)?

Background: There are millions of ADHF hospitalizations per year, and all-cause mortality and readmission rates are high. Efforts to better risk-stratify such patients have included measuring cTn levels and determining risk of increased length of stay, hospital readmission, and mortality.

Study design: Systematic review and meta-analysis.

Setting: Twenty-six observational cohort studies.

Synopsis: Compared with an undetectable cTn, detectable or elevated cTn levels were associated with greater length of stay (odds ratio [OR], 1.05; 95% CI, 1.01¬–1.10) and greater in-hospital death (OR, 2.57; 95% CI, 2.27–2.91). ADHF patients with detectable or elevated cTn were also at increased risk for mortality and composite of mortality and readmission over the short, intermediate, and long term. Reviewers eventually considered the overall association of a detectable or elevated troponin with mortality and readmission as moderate (relative association measure >2.0).

Meanwhile, few studies in this analysis showed a continuous and graded relationship between cTn levels and clinical outcomes.

Limitations of the review include arbitrarily stratifying groups by the level of cTn from assays whose lower limit of detection vary. The authors also admit the various associations are likely affected by several confounders for which they could not adjust because individual participant data were unavailable.

Finally, while acknowledging patients with chronic stable heart failure often have baseline elevated cTn levels, accounting for this in the analysis was limited.

Bottom line: A detectable or elevated level of cTn during ADHF hospitalization leads to worse outcomes both during and after discharge.

Citation: Yousufuddin M, Abdalrhim AD, Wang Z, Murad MH. Cardiac troponin in patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure: a systematic review and meta-analysis [published online ahead of print February 18, 2016]. J Hosp Med. doi:10.1002/jhm.2558.

New Guidelines for Cardiovascular Imaging in Chest Pain

Clinical question: Which cardiovascular imaging modalities can augment triage of ED patients with chest pain?

Background: Because absolute event rates for patients with chest pain and normal initial ECG findings are not low enough to drive discharge triage decisions, and findings that patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are inadvertently discharged because of less-sensitive troponin assays, there is great interest in what imaging modalities can facilitate safer triages.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Meta-analysis of studies in multiple clinical settings.

Synopsis: This guideline adopted two pathways: an early assessment pathway, which considers imaging without the need for serial biomarker analysis, and an observational pathway, which involves serial biomarker testing.

For the early assessment pathway, when ECG and/or biomarker analysis is unequivocally positive for ischemia, all rest-imaging modalities are rarely appropriate. When the initial troponin level is equivocal, both rest single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and coronary CT angiography (CCTA) are appropriate, though rest echocardiography and rest cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) may be alternatives. Resting imaging may also be appropriate when chest pain resolves prior to evaluation and/or initial ECG plus troponin is non-ischemic/normal.

In the observational pathway, for patients with ECG changes and/or serial troponins unequivocally positive for AMI, only cardiac catheterization is recommended. When serial ECGs/troponins are borderline, stress-test modalities and CCTA are appropriate. When serial ECGs/ troponins are negative, outpatient testing may be appropriate.

Bottom line: Experts recommend cardiac catheterization as the imaging modality of choice for patients with an unequivocal AMI diagnosis. When ECG and/or biomarkers are equivocal or negative, outpatient evaluation may be appropriate.

Citation: Rybicki FJ, Udelson JE, Peacock WF, et al. Appropriate utilization of cardiovascular imaging in emergency department patients with chest pain: a joint document of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria Committee and the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;(2):e1-e29. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2015.07.007.

Short Take

Family Reflections on End-of-Life Cancer Care

In this multicenter, prospective, observational study, family members of patients with advanced-stage cancer who received aggressive care at end of life were less likely to report the overall quality of end-of-life care as “excellent” or “very good.”

Citation: Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

Clinical question: Which cardiovascular imaging modalities can augment triage of ED patients with chest pain?

Background: Because absolute event rates for patients with chest pain and normal initial ECG findings are not low enough to drive discharge triage decisions, and findings that patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are inadvertently discharged because of less-sensitive troponin assays, there is great interest in what imaging modalities can facilitate safer triages.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Meta-analysis of studies in multiple clinical settings.

Synopsis: This guideline adopted two pathways: an early assessment pathway, which considers imaging without the need for serial biomarker analysis, and an observational pathway, which involves serial biomarker testing.

For the early assessment pathway, when ECG and/or biomarker analysis is unequivocally positive for ischemia, all rest-imaging modalities are rarely appropriate. When the initial troponin level is equivocal, both rest single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and coronary CT angiography (CCTA) are appropriate, though rest echocardiography and rest cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) may be alternatives. Resting imaging may also be appropriate when chest pain resolves prior to evaluation and/or initial ECG plus troponin is non-ischemic/normal.

In the observational pathway, for patients with ECG changes and/or serial troponins unequivocally positive for AMI, only cardiac catheterization is recommended. When serial ECGs/troponins are borderline, stress-test modalities and CCTA are appropriate. When serial ECGs/ troponins are negative, outpatient testing may be appropriate.

Bottom line: Experts recommend cardiac catheterization as the imaging modality of choice for patients with an unequivocal AMI diagnosis. When ECG and/or biomarkers are equivocal or negative, outpatient evaluation may be appropriate.

Citation: Rybicki FJ, Udelson JE, Peacock WF, et al. Appropriate utilization of cardiovascular imaging in emergency department patients with chest pain: a joint document of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria Committee and the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;(2):e1-e29. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2015.07.007.

Short Take

Family Reflections on End-of-Life Cancer Care

In this multicenter, prospective, observational study, family members of patients with advanced-stage cancer who received aggressive care at end of life were less likely to report the overall quality of end-of-life care as “excellent” or “very good.”

Citation: Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

Clinical question: Which cardiovascular imaging modalities can augment triage of ED patients with chest pain?

Background: Because absolute event rates for patients with chest pain and normal initial ECG findings are not low enough to drive discharge triage decisions, and findings that patients with acute myocardial infarction (AMI) are inadvertently discharged because of less-sensitive troponin assays, there is great interest in what imaging modalities can facilitate safer triages.

Study design: Clinical guideline.

Setting: Meta-analysis of studies in multiple clinical settings.

Synopsis: This guideline adopted two pathways: an early assessment pathway, which considers imaging without the need for serial biomarker analysis, and an observational pathway, which involves serial biomarker testing.

For the early assessment pathway, when ECG and/or biomarker analysis is unequivocally positive for ischemia, all rest-imaging modalities are rarely appropriate. When the initial troponin level is equivocal, both rest single-photon emission computed tomography (SPECT) and coronary CT angiography (CCTA) are appropriate, though rest echocardiography and rest cardiovascular magnetic resonance (CMR) may be alternatives. Resting imaging may also be appropriate when chest pain resolves prior to evaluation and/or initial ECG plus troponin is non-ischemic/normal.

In the observational pathway, for patients with ECG changes and/or serial troponins unequivocally positive for AMI, only cardiac catheterization is recommended. When serial ECGs/troponins are borderline, stress-test modalities and CCTA are appropriate. When serial ECGs/ troponins are negative, outpatient testing may be appropriate.

Bottom line: Experts recommend cardiac catheterization as the imaging modality of choice for patients with an unequivocal AMI diagnosis. When ECG and/or biomarkers are equivocal or negative, outpatient evaluation may be appropriate.

Citation: Rybicki FJ, Udelson JE, Peacock WF, et al. Appropriate utilization of cardiovascular imaging in emergency department patients with chest pain: a joint document of the American College of Radiology Appropriateness Criteria Committee and the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;(2):e1-e29. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2015.07.007.

Short Take

Family Reflections on End-of-Life Cancer Care

In this multicenter, prospective, observational study, family members of patients with advanced-stage cancer who received aggressive care at end of life were less likely to report the overall quality of end-of-life care as “excellent” or “very good.”

Citation: Wright AA, Keating NL, Ayanian JZ, et al. Family perspectives on aggressive cancer care near the end of life. JAMA. 2016;315(3):284-292.

EC broadens indication for ibrutinib

Photo from Janssen Biotech

The European Commission (EC) has broadened the indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to include newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug had already been approved in the European Union to treat adults with CLL who have received at least one prior therapy and adults with previously untreated CLL who have 17p deletion or TP53 mutation and are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Ibrutinib is now approved for all patients with CLL.

The EC is following the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), which had previously sent its endorsement to the EC.

This approval also follows the decision by the US Food and Drug Administration in March to approve the expanded use of ibrutinib capsules for treatment-naïve patients with CLL.

Ibrutinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma, adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who have received at least one prior therapy, and previously untreated adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

RESONATE-2 trial

The expanded ibrutinib indication is based on data from the phase 3, randomized, open-label RESONATE-2 trial, published in NEJM in 2015.

Results from the RESONATE-2 study showed that ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.05 to 0.56; P=0.001).

Ninety-eight percent of patients were still alive after 2 years, compared to 85% percent for patients randomized to the chlorambucil arm.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was not reached for patients receiving ibrutinib versus 18.9 months for those in the chlorambucil arm. This represented a statistically significant 84% reduction in the risk of death or progression in the ibrutinib arm (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.09 to 0.28; P<0.001).

“Ibrutinib has shown remarkable improvements in overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rates compared with chlorambucil,” said Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, one of the RESONATE-2 investigators.

The overall safety of ibrutinib in the treatment-naïve CLL patient population was consistent with previously reported studies.

The most common adverse events for ibrutinib of any grade occurring in 20% or more of the patients were diarrhea (42%), fatigue (30%), cough (22%), and nausea (22%).

“The RESONATE-2 data indicate that ibrutinib can provide a much-needed first line treatment alternative for many patients,” Dr Ghia affirmed.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International, a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen affiliates market ibrutinib in all approved countries except the US. In the US, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Pharmacyclics co-market it. ![]()

Photo from Janssen Biotech

The European Commission (EC) has broadened the indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to include newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug had already been approved in the European Union to treat adults with CLL who have received at least one prior therapy and adults with previously untreated CLL who have 17p deletion or TP53 mutation and are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Ibrutinib is now approved for all patients with CLL.

The EC is following the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), which had previously sent its endorsement to the EC.

This approval also follows the decision by the US Food and Drug Administration in March to approve the expanded use of ibrutinib capsules for treatment-naïve patients with CLL.

Ibrutinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma, adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who have received at least one prior therapy, and previously untreated adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

RESONATE-2 trial

The expanded ibrutinib indication is based on data from the phase 3, randomized, open-label RESONATE-2 trial, published in NEJM in 2015.

Results from the RESONATE-2 study showed that ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.05 to 0.56; P=0.001).

Ninety-eight percent of patients were still alive after 2 years, compared to 85% percent for patients randomized to the chlorambucil arm.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was not reached for patients receiving ibrutinib versus 18.9 months for those in the chlorambucil arm. This represented a statistically significant 84% reduction in the risk of death or progression in the ibrutinib arm (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.09 to 0.28; P<0.001).

“Ibrutinib has shown remarkable improvements in overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rates compared with chlorambucil,” said Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, one of the RESONATE-2 investigators.

The overall safety of ibrutinib in the treatment-naïve CLL patient population was consistent with previously reported studies.

The most common adverse events for ibrutinib of any grade occurring in 20% or more of the patients were diarrhea (42%), fatigue (30%), cough (22%), and nausea (22%).

“The RESONATE-2 data indicate that ibrutinib can provide a much-needed first line treatment alternative for many patients,” Dr Ghia affirmed.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International, a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen affiliates market ibrutinib in all approved countries except the US. In the US, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Pharmacyclics co-market it. ![]()

Photo from Janssen Biotech

The European Commission (EC) has broadened the indication for ibrutinib (Imbruvica) to include newly diagnosed patients with chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL).

The drug had already been approved in the European Union to treat adults with CLL who have received at least one prior therapy and adults with previously untreated CLL who have 17p deletion or TP53 mutation and are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

Ibrutinib is now approved for all patients with CLL.

The EC is following the recommendation of the European Medicines Agency’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP), which had previously sent its endorsement to the EC.

This approval also follows the decision by the US Food and Drug Administration in March to approve the expanded use of ibrutinib capsules for treatment-naïve patients with CLL.

Ibrutinib is also approved to treat adults with relapsed or refractory mantle cell lymphoma, adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who have received at least one prior therapy, and previously untreated adults with Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia who are unsuitable for chemo-immunotherapy.

RESONATE-2 trial

The expanded ibrutinib indication is based on data from the phase 3, randomized, open-label RESONATE-2 trial, published in NEJM in 2015.

Results from the RESONATE-2 study showed that ibrutinib significantly prolonged overall survival (OS) (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.05 to 0.56; P=0.001).

Ninety-eight percent of patients were still alive after 2 years, compared to 85% percent for patients randomized to the chlorambucil arm.

Median progression-free survival (PFS) was not reached for patients receiving ibrutinib versus 18.9 months for those in the chlorambucil arm. This represented a statistically significant 84% reduction in the risk of death or progression in the ibrutinib arm (HR=0.16, 95 percent CI 0.09 to 0.28; P<0.001).

“Ibrutinib has shown remarkable improvements in overall survival, progression-free survival, and response rates compared with chlorambucil,” said Paolo Ghia, MD, PhD, one of the RESONATE-2 investigators.

The overall safety of ibrutinib in the treatment-naïve CLL patient population was consistent with previously reported studies.

The most common adverse events for ibrutinib of any grade occurring in 20% or more of the patients were diarrhea (42%), fatigue (30%), cough (22%), and nausea (22%).

“The RESONATE-2 data indicate that ibrutinib can provide a much-needed first line treatment alternative for many patients,” Dr Ghia affirmed.

Ibrutinib is co-developed by Cilag GmbH International, a member of the Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies, and Pharmacyclics LLC, an AbbVie company. Janssen affiliates market ibrutinib in all approved countries except the US. In the US, Janssen Biotech, Inc. and Pharmacyclics co-market it. ![]()

Sodium influx may be key to killing Plasmodium parasites

invading an RBC

Credit: St Jude Children's

Research Hospital

Two new anti-malaria drug candidates with different mechanisms of action—a pyrazoleamide and a spiroindolone—promote an influx of sodium ions into Plasmodium parasites that have invaded red blood cells and multiply there.

Within minutes, the increase in sodium kills the parasites, investigators believe, by changing its outer membrane and promoting division before its genome has been replicated.

Akhil Vaidya, PhD, of Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, and members of the research team published details of their findings in PLOS Pathogens.

The Plasmodium plasma membrane contains very low levels of cholesterol, which is a major lipid component of most other cell membranes.

Saponin, a detergent that can dissolve cholesterol-containing membranes, dissolves red blood cells infected by Plasmodium and releases intact parasites into the bloodstream. The detergent is unable to destroy the parasites because their membranes have low cholesterol content.

However, when researchers exposed the parasite cell membranes to the 2 drugs, they became permeable by saponin. The researchers deemed this to be a function of the increased amount of cholesterol incorporated into the parasite membrane.

“We believe that the cholesterol makes the parasite rigid, and then the parasite can no longer pass through very small spaces in the bloodstream,” Dr Vaidya said. The parasite cannot continue its lifecycle if it cannot enter red blood cells.

Researchers also discovered that when drug exposure is short, the changes in membrane composition are reversible. The parasites regain their resistance to saponin most likely because the additional membrane cholesterol washes off.

After 2 hours of treatment with either drug, many of the parasites had fragmented nuclei and interior membranes. Researchers did not observe any sign of multiplication of the parasite genome, which is necessary to create daughter cells and precedes other cell division events.

The researchers were surprised by the findings. They had assumed that the spiroindolone, KAE609 (cipargamin), which is being investigated in clinical trials, killed parasites through a different mechanism.

The investigators maintain that by understanding exactly how new drug candidates stop malaria, they will learn more about the parasite’s vulnerabilities and be able to determine the origin of drug resistance as soon as it arises.

“We want to find the best ways to keep new drugs effective as long as we can,” Dr Vaidya said.

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AI98413 and Medicines for Malaria Venture Grant MMV/08/0027. ![]()

invading an RBC

Credit: St Jude Children's

Research Hospital

Two new anti-malaria drug candidates with different mechanisms of action—a pyrazoleamide and a spiroindolone—promote an influx of sodium ions into Plasmodium parasites that have invaded red blood cells and multiply there.

Within minutes, the increase in sodium kills the parasites, investigators believe, by changing its outer membrane and promoting division before its genome has been replicated.

Akhil Vaidya, PhD, of Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, and members of the research team published details of their findings in PLOS Pathogens.

The Plasmodium plasma membrane contains very low levels of cholesterol, which is a major lipid component of most other cell membranes.

Saponin, a detergent that can dissolve cholesterol-containing membranes, dissolves red blood cells infected by Plasmodium and releases intact parasites into the bloodstream. The detergent is unable to destroy the parasites because their membranes have low cholesterol content.

However, when researchers exposed the parasite cell membranes to the 2 drugs, they became permeable by saponin. The researchers deemed this to be a function of the increased amount of cholesterol incorporated into the parasite membrane.

“We believe that the cholesterol makes the parasite rigid, and then the parasite can no longer pass through very small spaces in the bloodstream,” Dr Vaidya said. The parasite cannot continue its lifecycle if it cannot enter red blood cells.

Researchers also discovered that when drug exposure is short, the changes in membrane composition are reversible. The parasites regain their resistance to saponin most likely because the additional membrane cholesterol washes off.

After 2 hours of treatment with either drug, many of the parasites had fragmented nuclei and interior membranes. Researchers did not observe any sign of multiplication of the parasite genome, which is necessary to create daughter cells and precedes other cell division events.

The researchers were surprised by the findings. They had assumed that the spiroindolone, KAE609 (cipargamin), which is being investigated in clinical trials, killed parasites through a different mechanism.

The investigators maintain that by understanding exactly how new drug candidates stop malaria, they will learn more about the parasite’s vulnerabilities and be able to determine the origin of drug resistance as soon as it arises.

“We want to find the best ways to keep new drugs effective as long as we can,” Dr Vaidya said.

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AI98413 and Medicines for Malaria Venture Grant MMV/08/0027. ![]()

invading an RBC

Credit: St Jude Children's

Research Hospital

Two new anti-malaria drug candidates with different mechanisms of action—a pyrazoleamide and a spiroindolone—promote an influx of sodium ions into Plasmodium parasites that have invaded red blood cells and multiply there.

Within minutes, the increase in sodium kills the parasites, investigators believe, by changing its outer membrane and promoting division before its genome has been replicated.

Akhil Vaidya, PhD, of Drexel University College of Medicine in Philadelphia, and members of the research team published details of their findings in PLOS Pathogens.

The Plasmodium plasma membrane contains very low levels of cholesterol, which is a major lipid component of most other cell membranes.

Saponin, a detergent that can dissolve cholesterol-containing membranes, dissolves red blood cells infected by Plasmodium and releases intact parasites into the bloodstream. The detergent is unable to destroy the parasites because their membranes have low cholesterol content.

However, when researchers exposed the parasite cell membranes to the 2 drugs, they became permeable by saponin. The researchers deemed this to be a function of the increased amount of cholesterol incorporated into the parasite membrane.

“We believe that the cholesterol makes the parasite rigid, and then the parasite can no longer pass through very small spaces in the bloodstream,” Dr Vaidya said. The parasite cannot continue its lifecycle if it cannot enter red blood cells.

Researchers also discovered that when drug exposure is short, the changes in membrane composition are reversible. The parasites regain their resistance to saponin most likely because the additional membrane cholesterol washes off.

After 2 hours of treatment with either drug, many of the parasites had fragmented nuclei and interior membranes. Researchers did not observe any sign of multiplication of the parasite genome, which is necessary to create daughter cells and precedes other cell division events.

The researchers were surprised by the findings. They had assumed that the spiroindolone, KAE609 (cipargamin), which is being investigated in clinical trials, killed parasites through a different mechanism.

The investigators maintain that by understanding exactly how new drug candidates stop malaria, they will learn more about the parasite’s vulnerabilities and be able to determine the origin of drug resistance as soon as it arises.

“We want to find the best ways to keep new drugs effective as long as we can,” Dr Vaidya said.

This study was funded by National Institutes of Health Grant R01-AI98413 and Medicines for Malaria Venture Grant MMV/08/0027. ![]()

IVC and Mortality in ADHF

Heart failure costs the United States an excess of $30 billion annually, and costs are projected to increase to nearly $70 billion by 2030.[1] Heart failure accounts for over 1 million hospitalizations and is the leading cause of hospitalization in patients >65 years of age.[2] After hospitalization, approximately 50% of patients are readmitted within 6 months of hospital discharge.[3] Mortality rates from heart failure have improved but remain high.[4] Approximately 50% of patients diagnosed with heart failure die within 5 years, and the overall 1‐year mortality rate is 30%.[1]

Prognostic markers and scoring systems for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) continue to emerge, but few bedside tools are available to clinicians. Age, brain natriuretic peptide, and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) levels have been shown to correlate with postdischarge rates of readmission and mortality.[5] A study evaluating the prognostic value of a bedside inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound exam demonstrated that lack of improvement in IVC distention from admission to discharge was associated with higher 30‐day readmission rates.[6] Two studies using data from comprehensive transthoracic echocardiograms in heart failure patients demonstrated that a dilated, noncollapsible IVC is associated with higher risk of mortality; however, it is well recognized that obtaining comprehensive transthoracic echocardiograms in all patients hospitalized with heart failure is neither cost‐effective nor practical.[7]

In recent years, multiple studies have emerged demonstrating that noncardiologists can perform focused cardiac ultrasound exams with high reproducibility and accuracy to guide management of patients with ADHF.[8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14] However, it is unknown whether IVC characteristics from a focused cardiac ultrasound exam performed by a noncardiologist can predict mortality of patients hospitalized with ADHF. The aim of this study was to assess whether a hospitalist‐performed focused ultrasound exam to measure the IVC diameter at admission and discharge can predict mortality in a general medicine ward population hospitalized with ADHF.

METHODS

Study Design

A prospective, observational study of patients admitted to a general medicine ward with ADHF between January 2012 and March 2013 was performed using convenience sampling. The setting was a 247‐bed, university‐affiliated hospital in Madrid, Spain. Inclusion criteria were adult patients admitted with a primary diagnosis of ADHF per the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) criteria.[15] Exclusion criteria were admission to the intensive care unit for mechanical ventilation, need for chronic hemodialysis, or a noncardiac terminal illness with a life expectancy of less than 3 months. All patients provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. This study complies with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by the local ethics committee.

The primary outcome was all‐cause mortality at 90 days after hospitalization. The secondary outcomes were hospital readmission at 90 and 180 days, and mortality at 180 days. Patients were prospectively followed up at 30, 60, 90, and 180 days after discharge by telephone interview or by review of the patient's electronic health record. Patients who died within 90 days of discharge were categorized as nonsurvivors, whereas those alive at 90 days were categorized as survivors.

The following data were recorded on admission: age, gender, blood pressure, heart rate, functional class per New York Heart Association (NYHA) classification, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, atrial fibrillation, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease), primary etiology of heart failure, medications, electrocardiogram, NT‐terminal pro‐BNP, hemoglobin, albumin, creatinine, sodium, measurement of performance of activities of daily living (modified Barthel index), and comorbidity score (age‐adjusted Charlson score). A research coordinator interviewed subjects to gather data to calculate a modified Barthel index.[16] Age‐adjusted Charlson comorbidity scores were calculated using age and diagnoses per International Classification of Diseases, Ninth Revision coding.[17]

IVC Measurement

An internal medicine hospitalist with expertise in point‐of‐care ultrasonography (G.G.C.) performed all focused cardiac ultrasound exams to measure the IVC diameter and collapsibility at the time of admission and discharge. This physician was not involved in the inpatient medical management of study subjects. A second physician (N.J.S.) randomly reviewed 10% of the IVC images for quality assurance. Admission IVC measurements were acquired within 24 hours of arrival to the emergency department after the on‐call medical team was contacted to admit the patient. Measurement of the IVC maximum (IVCmax) and IVC minimum (IVCmin) diameters was obtained just distal to the hepatic veinIVC junction, or 2 cm from the IVCright atrial junction using a long‐axis view of the IVC. Measurement of the IVC diameter was consistent with the technique recommended by the American Society of Echocardiography and European Society of Echocardiography guidelines.[18, 19] The IVC collapsibility index (IVCCI) was calculated as (IVCmaxIVCmin)/IVCmax per guidelines.[18] Focused cardiac ultrasound exams were performed using a General Electric Logiq E device (GE Healthcare, Little Chalfont, United Kingdom) with a 3.5 MHz curvilinear transducer. Inpatient medical management by the primary medical team was guided by protocols from the ESC guidelines on the treatment of ADHF.[15] A comprehensive transthoracic echocardiogram (TTE) was performed on all study subjects by the echocardiography laboratory within 24 hours of hospitalization as part of the study protocol. One of 3 senior cardiologists read all comprehensive TTEs. NT‐proBNP was measured on admission and discharge by electrochemiluminescence.

Statistical Analysis

We calculated the required sample size based on published mortality and readmission rates. For our primary outcome of 90‐day mortality, we calculated a required sample size of 64 to achieve 80% power based on 90‐day and 1‐year mortality rates of 21% and 33%, respectively, among Spanish elderly patients (age 70 years) hospitalized with ADHF.[20] For our secondary outcome of 90‐day readmissions, we calculated a sample size of 28 based on a 41% readmission rate.[21] Therefore, our target subject enrollment was at least 70 patients to achieve a power of 80%.

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 17.0 statistical package (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL). Subject characteristics that were categorical variables (demographics and comorbidities) were summarized as counts and percentages. Continuous variables, including IVC measurements, were summarized as means with standard deviations. Differences between categorical variables were analyzed using the Fisher exact test. Survival curves with log‐rank statistics were used to perform survival analysis. The nonparametric Mann‐Whitney U test was used to assess associations between the change in IVCCI, and readmissions and mortality at 90 and 180 days. Predictors of readmission and death were evaluated using a multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis. Given the limited number of primary outcome events, we used age, IVC diameter, and log NT‐proBNP in the multivariate regression analysis based on past studies showing prognostic significance of these variables.[6, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28] Optimal cutoff values for IVC diameter for death and readmission prediction were determined by constructing receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and calculating the area under the curve (AUC) for different IVC diameters. NT‐proBNP values were log‐transformed to minimize skewing as reported in previous studies.[29]

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

Ninety‐seven patients admitted with ADHF were recruited for the study. Optimal acoustic windows to measure the IVC diameter were acquired in 90 patients (93%). Because measurement of discharge IVC diameter was required to calculate the change from admission to discharge, 8 patients who died during initial hospitalization were excluded from the final data analysis. An additional two patients were excluded due to missing discharge NT‐proBNP measurement or missing comprehensive echocardiogram data. The study cohort from whom data were analyzed included 80 of 97 total patients (82%).

Baseline demographic, clinical, laboratory, and comprehensive echocardiographic characteristics of nonsurvivors and survivors at 90 days are demonstrated in Table 1. Eleven patients (13.7%) died during the first 90 days postdischarge, and all deaths were due to cardiovascular complications. Nonsurvivors were older (86 vs 76 years; P = 0.02), less independent in performance of their activities of daily living (Barthel index of 58.1 vs 81.9; P = 0.01), and were more likely to have advanced heart failure with an NYHA functional class of III or IV (72% vs 33%; P = 0.016). Atrial fibrillation (90% vs 55%; P = 0.008) and lower systolic blood pressure (127 mm Hg vs 147 mm Hg; P = 0.01) were more common in nonsurvivors than survivors, and fewer nonsurvivors were taking a ‐blocker (18% vs 59%; P = 0.01). Baseline comprehensive echocardiographic findings were similar between the survivors and nonsurvivors, except left atrial diameter was larger in nonsurvivors versus survivors (54 mm vs 49 mm; P = 0.04).

| Total Cohort, n = 80 | Nonsurvivors, n = 11 | Survivors, n = 69 | P Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||

| Demographics | ||||

| Age, y* | 78 (13) | 86 (7) | 76 (14) | 0.02 |

| Men, n (%) | 34 (42) | 3 (27) | 26 (38) | 0.3 |

| Vital signs* | ||||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 94 (23) | 99 (26) | 95 (23) | 0.5 |

| SBP, mm Hg | 141 (27) | 127 (22) | 147 (25) | 0.01 |

| Comorbidities, n (%) | ||||

| Hypertension | 72 (90) | 10 (91) | 54 (78) | 0.3 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 35 (44) | 3 (27) | 26 (38) | 0.3 |

| Atrial fibrillation | 48 (60) | 10 (90) | 38 (55) | 0.008 |

| COPD | 22 (27) | 3 (27) | 16 (23) | 0.5 |

| Etiology of heart failure | ||||

| Ischemic | 20 (25) | 1 (9) | 16 (23) | 0.1 |

| Hypertensive | 22 (27) | 2 (18) | 18 (26) | 0.4 |

| Valvulopathy | 29 (36) | 7 (64) | 19 (27) | 0.07 |

| Other | 18 (22) | 1 (9) | 16 (23) | 0.09 |

| NYHA IIIIV | 38 (47) | 8 (72) | 23 (33) | 0.016 |

| Charlson score* | 7.5 (2) | 9.0 (3) | 7.1 (2) | 0.02 |

| Barthel index* | 76 (31) | 58 (37) | 81.9 (28) | 0.01 |

| Medications | ||||

| ‐blocker | 44 (55) | 2 (18) | 41 (59) | 0.01 |

| ACE inhibitor/ARB | 48 (60) | 3 (27) | 35 (51) | 0.1 |

| Loop diuretic | 78 (97) | 10 (91) | 67 (97) | 0.9 |

| Aldosterone antagonist | 31 (39) | 4 (36) | 21 (30) | 0.4 |

| Lab results* | ||||

| Sodium, mmol/L | 137 (4.8) | 138 (6) | 139 (4) | 0.6 |

| Creatinine, umol/L | 1.24 (0.4) | 1.40 (0.5) | 1.17 (0.4) | 0.1 |

| eGFR, mL/min | 57.8 (20) | 51.2 (20) | 60.2 (19) | 0.1 |

| Albumin, g/L | 3.4 (0.4) | 3.3 (0.38) | 3.5 (0.41) | 0.1 |

| Hemoglobin, g/dL | 12.0 (2) | 10.9 (1.8) | 12.5 (2.0) | 0.01 |

| Echo parameters* | ||||

| LVEF, % | 52.1 (15) | 51.9 (17) | 51.6 (15) | 0.9 |

| LA diameter, mm | 50.1 (10) | 54 (11) | 49 (11) | 0.04 |

| RVDD, mm | 32.0 (11) | 34 (10) | 31 (11) | 0.2 |

| TAPSE, mm | 18.5 (7) | 17.4 (4) | 18.8 (7) | 0.6 |

| PASP, mm Hg | 51.2 (16) | 53.9 (17) | 50.2 (17) | 0.2 |

| Admission* | ||||

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 8,816 (14,260) | 9,413 (5,703) | 8,762 (15,368) | 0.81 |

| Log NT‐proBNP | 3.66 (0.50) | 3.88 (0.31 | 3.62 (0.52) | 0.11 |

| IVCmax, cm | 2.12 (0.59) | 2.39 (0.37) | 2.06 (0.59) | 0.02 |

| IVCmin, cm | 1.63 (0.69) | 1.82 (0.66) | 1.56 (0.67) | 0.25 |

| IVCCI, % | 25.7 (0.16) | 25.9 (17.0) | 26.2 (16.0) | 0.95 |

| Discharge* | ||||

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 3,132 (3,093) | 4,693 (4,383) | 2,909 (2,847) | 0.08 |

| Log NT‐proBNP | 3.27 (0.49) | 3.51 (0.37) | 3.23 (0.50) | 0.08 |

| IVCmax, cm | 1.87 (0.68) | 1.97 (0.54) | 1.81 (0.66) | 0.45 |

| IVCmin, cm | 1.33 (0.75) | 1.40 (0.65) | 1.27 (0.71) | 0.56 |

| IVCCI, % | 33.1 (0.20) | 32.0 (21.0) | 34.2 (19.0) | 0.74 |

From admission to discharge, the total study cohort demonstrated a highly statistically significant reduction in NT‐proBNP (8816 vs 3093; P 0.001), log NT‐proBNP (3.66 vs 3.27; P 0.001), IVCmax (2.12 vs 1.87; P 0.001), IVCmin (1.63 vs 1.33; P 0.001), and IVCCI (25.7% vs 33.1%; P 0.001). The admission and discharge NT‐proBNP and IVC characteristics of the survivors and nonsurvivors are displayed in Table 2. The only statistically significant difference between nonsurvivors and survivors was the admission IVCmax (2.39 vs 2.06; P = 0.02). There was not a statistically significant difference in the discharge IVCmax between nonsurvivors and survivors.

| Admission | Discharge | Difference (DischargeAdmission) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nonsurvivors | Survivors | P Value | Nonsurvivors | Survivors | P Value | Nonsurvivors | Survivors | P Value | |

| |||||||||

| NT‐proBNP, pg/mL | 9,413 (5,703) | 8,762 (15,368) | 0.81 | 4,693 (4,383) | 2,909 (2,847) | 0.08 | 3,717 5,043 | 5,026 11,507 | 0.7 |

| Log NT‐proBNP | 3.88 0.31 | 3.62 0.52 | 0.11 | 3.51 0.37 | 3.23 0.50 | 0.08 | 0.29 0.36 | 0.38 0.37 | 0.4 |

| IVCmax, cm | 2.39 0.37 | 2.06 0.59 | 0.02 | 1.97 0.54 | 1.81 0.66 | 0.45 | 0.39 0.56 | 0.25 0.51 | 0.4 |

| IVCmin, cm | 1.82 0.66 | 1.56 0.67 | 0.25 | 1.40 0.65 | 1.27 0.71 | 0.56 | 0.37 0.52 | 0.30 0.64 | 0.7 |

| IVCCI, % | 25.9 17.0 | 26.2 16.0 | 0.95 | 32.0 21.0 | 34.2 19.0 | 0.74 | 3.7 7.9 | 8.3 22 | 0.5 |

Outcomes

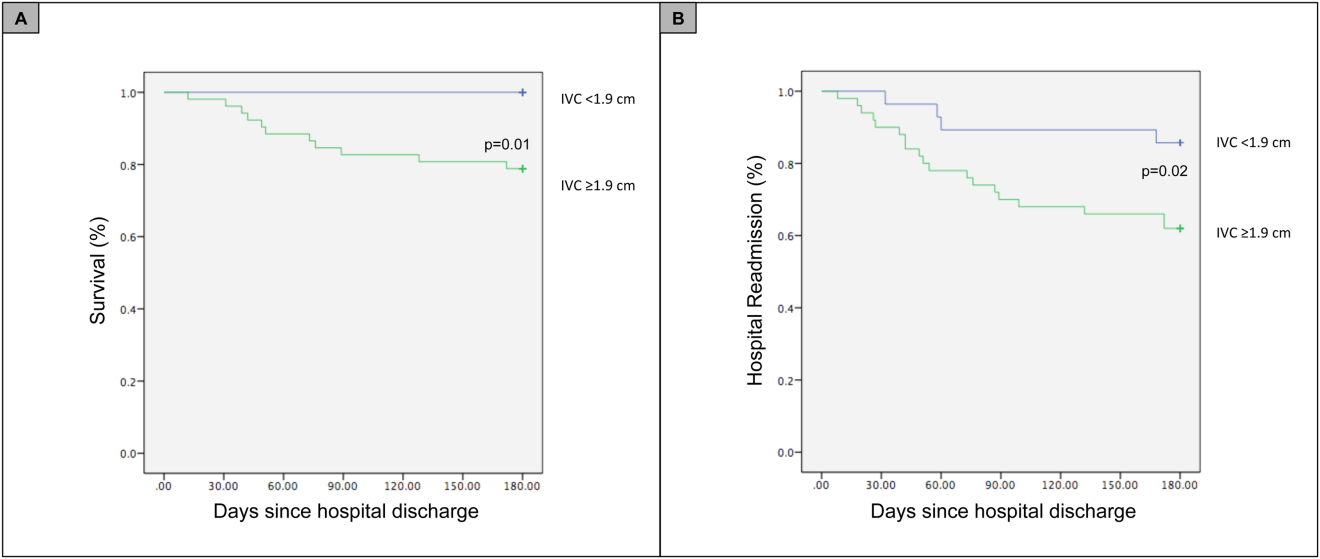

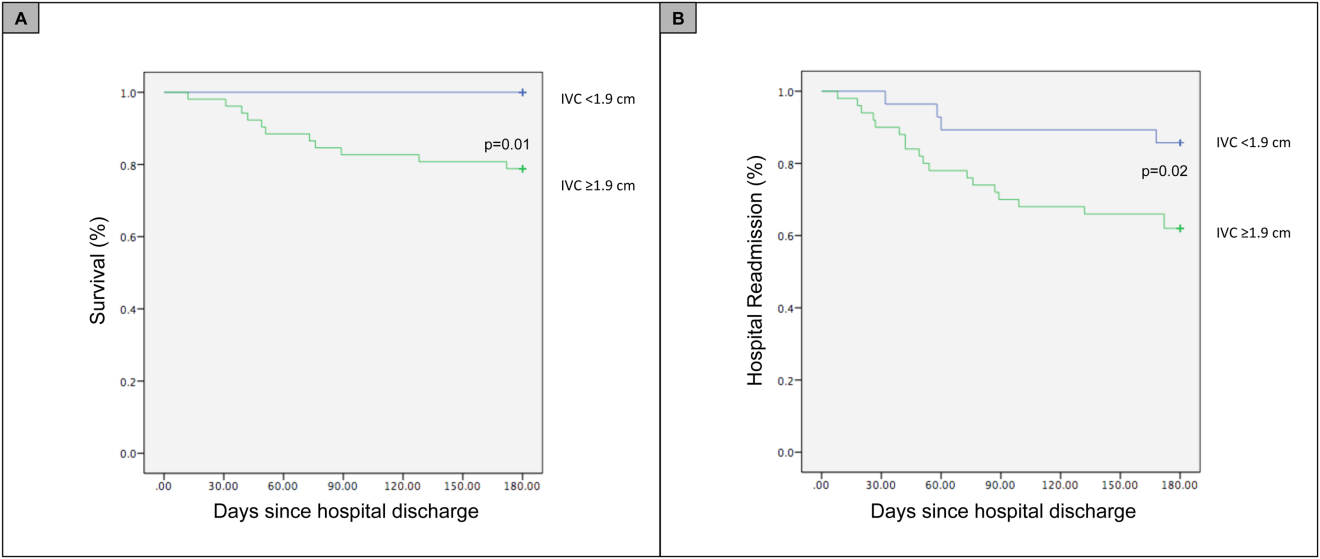

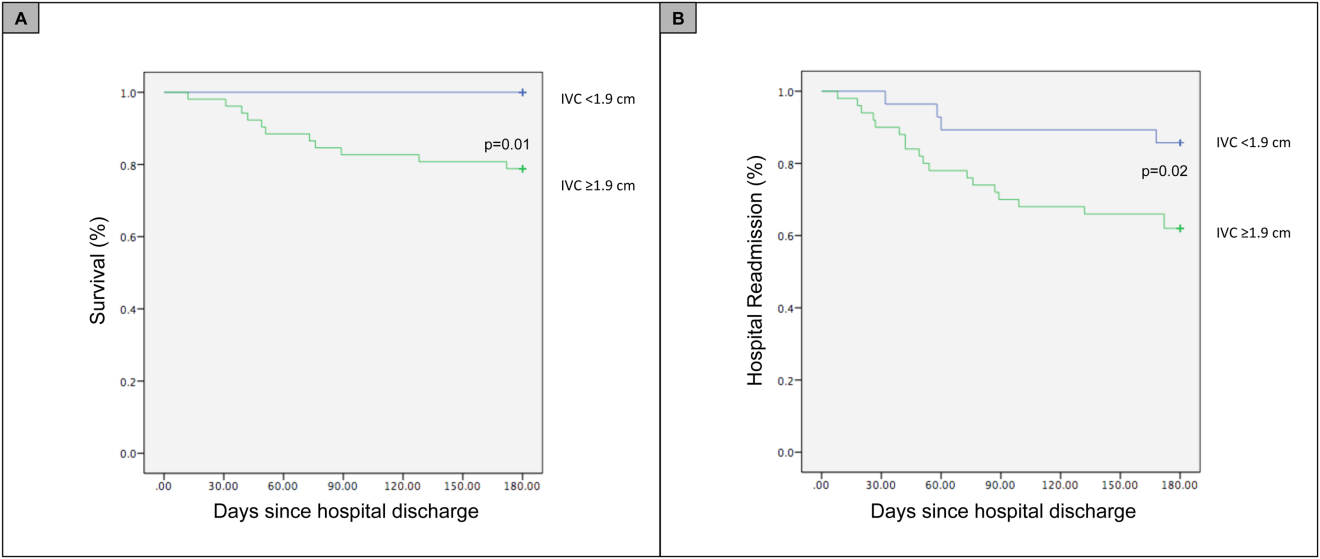

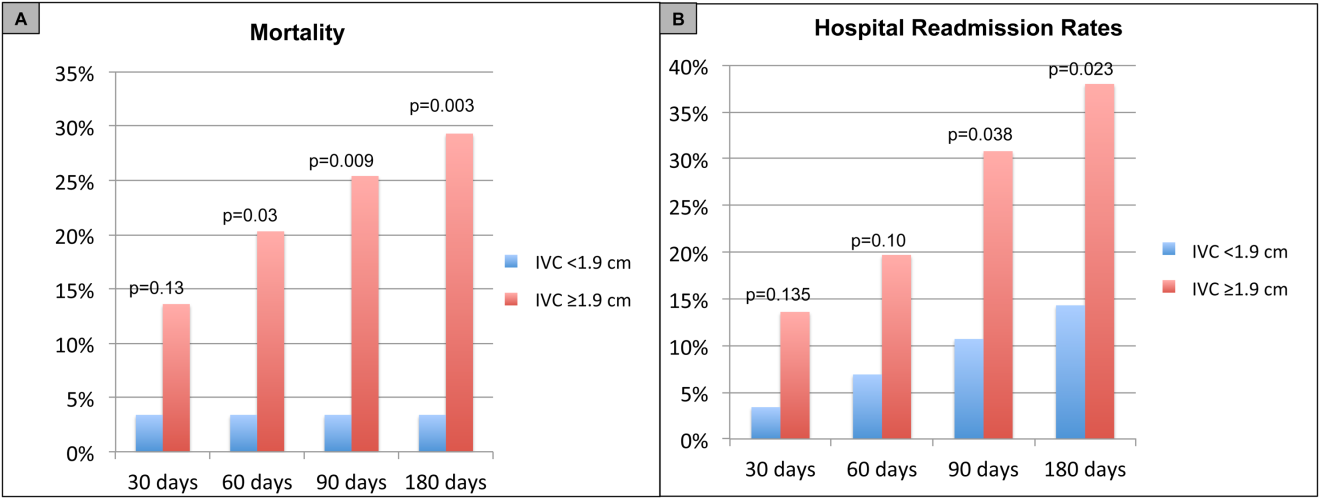

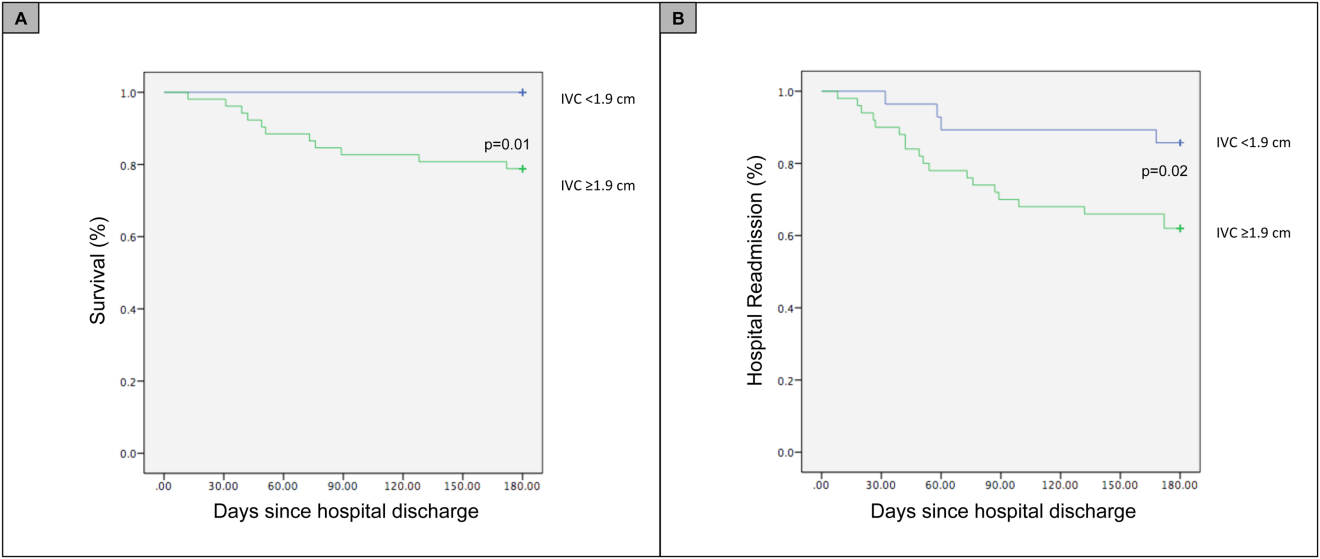

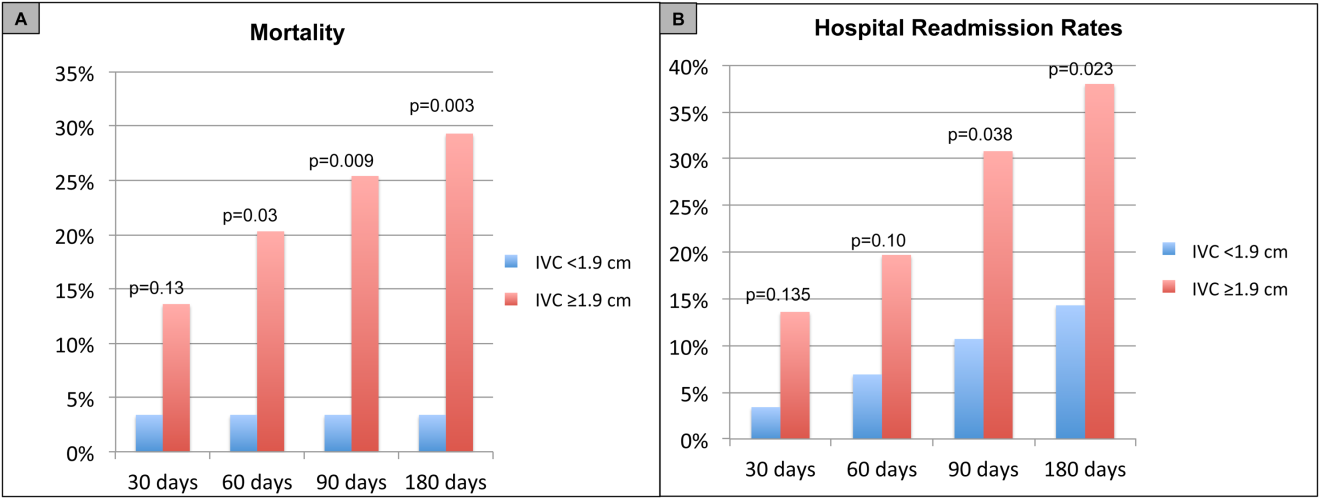

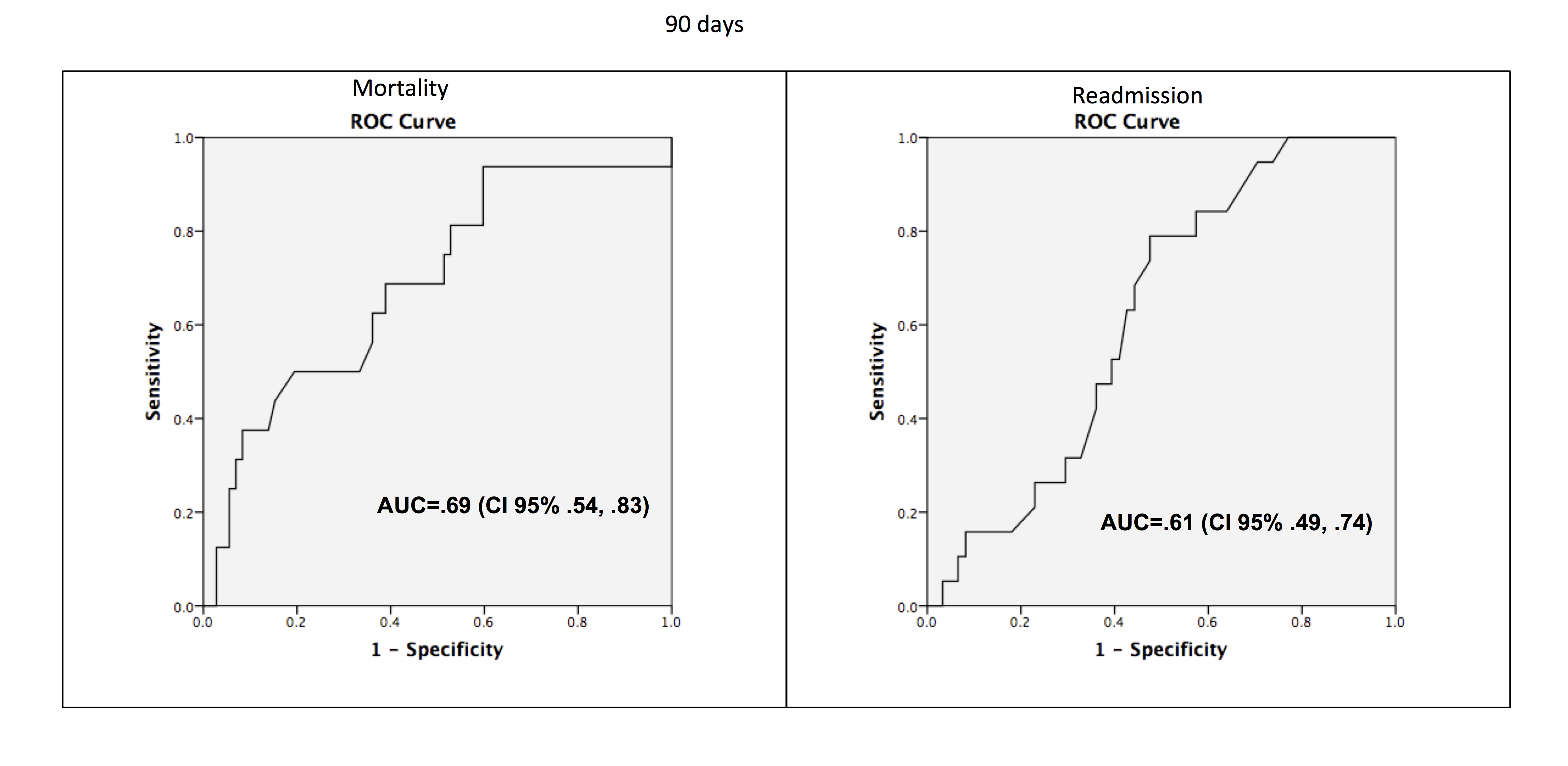

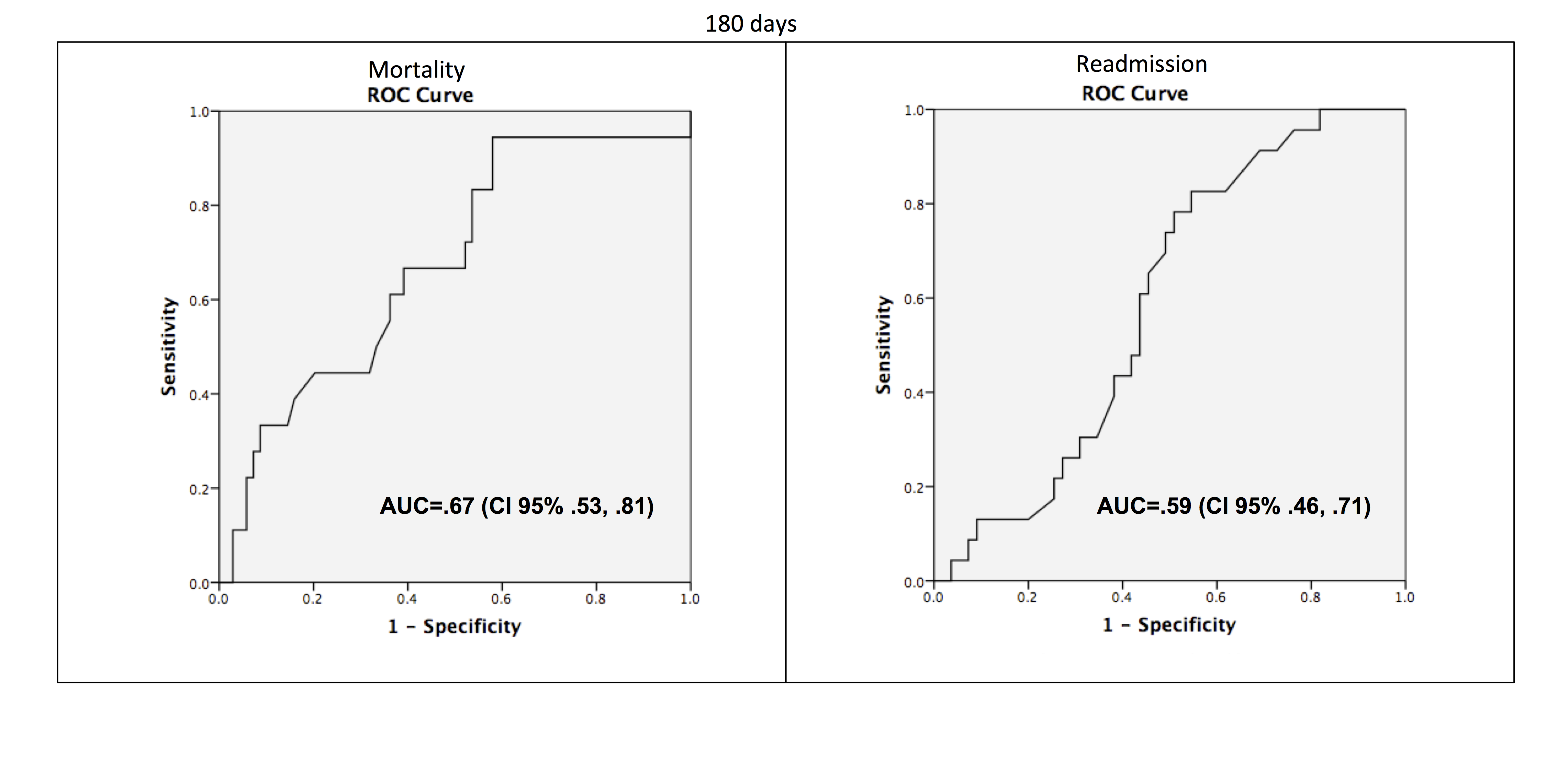

For the primary outcome of 90‐day mortality, the ROC curves showed a similar AUC for the admission IVCmax diameter (AUC: 0.69; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.53‐0.85), log NT‐proBNP at discharge (AUC: 0.67; 95% CI: 0.49‐0.85), and log NT‐proBNP at admission (AUC: 0.69; 95% CI: 0.52‐0.85). The optimal cutoff value for the admission IVCmax diameter to predict mortality was 1.9 cm (sensitivity 100%, specificity 38%) based on the ROC curves (see Supporting Information, Appendices 1 and 2, in the online version of this article). An admission IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm was associated with a higher mortality rate at 90 days (25.4% vs 3.4%; P = 0.009) and 180 days (29.3% vs 3.4%; P = 0.003). The Cox survival curves showed significantly lower survival rates in patients with an admission IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm (74.1 vs 96.7%; P = 0.012) (Figures 1 and 2). Based on the multivariate Cox proportional hazards regression analysis with age, IVCmax diameter, and log NT‐proBNP at admission, the admission IVCmax diameter and age were independent predictors of 90‐ and 180‐day mortality. The hazard ratios for death by age, admission IVCmax diameter, and log NT‐proBNP are shown in Table 3.

| Endpoint | Variable | HR (95% CI) | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| |||

| 90‐day mortality | Age | 1.14 (1.031.26) | 0.009 |

| IVC diameter at admission | 5.88 (1.2128.1) | 0.025 | |

| Log NT‐proBNP at admission | 1.00 (1.001.00) | 0.910 | |

| 90‐day readmission | Age | 1.06 (1.001.12) | 0.025 |

| IVC diameter at admission | 3.20 (1.248.21) | 0.016 | |

| Log NT‐proBNP at discharge | 1.00 (1.001.00) | 0.910 | |

| 180‐day mortality | Age | 1.12 (1.031.22) | 0.007 |

| IVC diameter at admission | 4.77 (1.2118.7) | 0.025 | |

| Log NT‐proBNP at admission | 1.00 (1.001.00) | 0.610 | |

| 180‐day readmission | Age | 1.06 (1.011.11) | 0.009 |

| IVC diameter at admission | 2.56 (1.145.74) | 0.022 | |

| Log NT‐proBNP at discharge | 1.00 (1.001.00) | 0.610 | |

For the secondary outcome of 90‐day readmissions, 19 patients (24%) were readmitted, and the mean index admission IVCmax diameter was significantly greater in patients who were readmitted (2.36 vs 1.98 cm; P = 0.04). The ROC curves for readmission at 90 days showed that an index admission IVCmax diameter of 1.9 cm had the greatest AUC (0.61; 95% CI: 0.49‐0.74). The optimal cutoff value of an index admission IVCmax to predict readmission was also 1.9 cm (sensitivity 94%, specificity 42%) (see Supporting Information, Appendices 1 and 2, in the online version of this article). The Cox survival analysis showed that patients with an index admission IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm had a higher readmission rate at 90 days (30.8% vs 10.7%; P = 0.04) and 180 days (38.0 vs 14.3%; P = 0.02) (Figures 1 and 2). Using a multivariate Cox proportional regression analysis, the hazard ratios for the variables of age, admission IVCmax diameter, and log NT‐proBNP are shown in Table 3.

DISCUSSION

Our study found that a dilated IVC at admission is associated with a poor prognosis after hospitalization for ADHF. Patients with a dilated IVC 1.9 cm at admission had higher mortality and readmission rates at 90 and 180 days postdischarge.

The effect of a dilated IVC on mortality may be mediated through unrecognized right ventricular disease with or without significant pulmonary hypertension, supporting the notion that right heart function is an important determinant of prognosis in patients with ADHF.[30, 31] Similar to elevated jugular venous distension, bedside ultrasound examination of the IVC diameter can serve as a rapid and noninvasive measurement of right atrial pressure.[32] Elevated right atrial pressure is most often due to elevated left ventricular filling pressure transmitted via the pulmonary vasculature, but it is important to note that right‐ and left‐sided cardiac pressures are often discordant in heart failure patients.[33, 34]

Few studies have evaluated the prognostic value of IVC diameter and collapsibility in patients with heart failure. Nath et al.[24] evaluated the prognostic value of IVC diameter in stable veterans referred for outpatient echocardiography. Patients with a dilated IVC >2 cm that did not collapse with inspiration had higher 90‐day and 1‐year mortality rates. A subsequent study by Pellicori et al.[22] investigated the relationship between IVC diameter and other prognostic markers in stable cardiac patients. Pellicori et al. demonstrated that IVC diameter and serum NT‐proBNP levels were independent predictors of a composite endpoint of cardiovascular death or heart failure hospitalization at 1 year.[22] Most recently, Lee et al.[23] evaluated whether a dilated IVC in patients with a history of advanced systolic heart failure with a reduced ejection fraction of 30% and repeated hospitalizations (2) predicted worsening renal failure and adverse cardiovascular outcomes (death or hospitalization for ADHF). The study concluded that age, IVC diameter >2.1 cm, and worsening renal failure predicted cardiovascular death or hospitalization for ADHF.[23]

Our study demonstrated that an admission IVCmax 1.9 cm in hospitalized ADHF patients predicted higher postdischarge mortality at 90 and 180 days. Our findings are consistent with the above‐mentioned studies with a few important differences. First, all of our patients were hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. Nath et al. and Pellicori et al. evaluated stable ambulatory patients seen in an echocardiography lab and cardiology clinic, respectively. Only 12.1% of patients in the Nath study had a history of heart failure, and none were reported to have ADHF. More importantly, our study improves our understanding of patients with heart failure with a preserved ejection fraction, an important gap in the literature. The mean ejection fraction of patients in our study was 52% consistent with heart failure with preserved ejection fraction, whereas patients in the Pellicori et al. and Lee et al. studies had heart failure with reduced (42%) or severely reduced (30%) ejection fraction, respectively. We did not anticipate finding heart failure with preserved ejection fraction in the majority of patients, but our study's findings will add to our understanding of this increasingly common type of heart failure.

Compared to previous studies that utilized a registered diagnostic cardiac sonographer to obtain a comprehensive TTE to prognosticate patients, our study utilized point‐of‐care ultrasonography. Nath et al. commented that obtaining a comprehensive echocardiogram on every patient with ADHF is unlikely to be cost‐effective or feasible. Our study utilized a more realistic approach with a frontline internal medicinetrained hospitalist acquiring and interpreting images of the IVC at the bedside using a basic portable ultrasound machine.

Our study did not show that plasma natriuretic peptides levels are predictive of death or readmission after hospitalization for ADHF as shown in previous studies.[22, 35, 36] The small sample size, relatively low event rate, or predominance of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction may explain this inconsistency with prior studies.

Previous studies have reported hospital readmission rates for ADHF of 30% to 44% after 1 to 6 months.[6, 37] Goonewardena et al. showed a 41.3% readmission rate at 30 days in patients with severely reduced left ventricular ejection fraction (mean 29%), and readmitted patients had an IVCmax diameter >2 cm and an IVC collapsibility 50% on admission and discharge.[6] Carbone et al. demonstrated absence of improvement in the minimum IVC diameter from admission to discharge using hand‐carried ultrasound in patients with ischemic heart disease (ejection fraction 33%) predicted readmission at 60 days.[38] Hospital readmission rates in our study are consistent with these previously published studies. We found readmission rates for patients with ADHF and an admission IVCmax 1.9 cm to be 30.8% and 38.0% after 90 and 180 days, respectively.

Important limitations of our study are the small sample size and single institution setting. A larger sample size may have demonstrated that change in IVC diameter and NT‐proBNP levels from admission to discharge to be predictive of mortality or readmission. Further, we found an IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm to be the optimal cutoff to predict mortality, which is less than an IVCmax diameter >2.0 cm reported in other studies. The relatively smaller IVC diameter in Spanish heart failure patients may be explained by the lower body mass index of this population. An IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm was found to be the optimal cutoff to predict an elevated right atrial pressure >10 mm Hg in a study of Japanese cardiac patients with a relatively lower body mass index.[39] Another limitation is the timing of the admission IVC measurement within the first 24 hours of arrival to the hospital rather than immediately upon arrival to the emergency department. We were not able to control for interventions given in the emergency department prior to the measurement of the admission IVC, including doses of diuretics. Further, unlike the comprehensive TTEs in the United States, TTEs in Spain do not routinely include an assessment of the IVC. Therefore, we were not able to compare our bedside IVC measurements to those from a comprehensive TTE. An important limitation of our regression analysis is the inclusion of only 3 variables. The selection of variables (age, NT‐proBNP, and IVC diameter) was based on prior studies demonstrating their prognostic value.[6, 22, 25] Due to the low event rate (n = 11), we could not include in the regression model other variables that differed significantly between nonsurvivors and survivors, including NYHA class, presence of atrial fibrillation, and use of ‐blockers.

Perhaps in a larger study population the admission IVCmax diameter may not be as predictive of 90‐day mortality as other variables. The findings of our exploratory analysis should be confirmed in a future study with a larger sample size.

The clinical implications of our study are 3‐fold. First, our study demonstrates that IVC images acquired by a hospitalist at the bedside using a portable ultrasound machine can be used to predict postdischarge mortality and readmission of patients with ADHF. Second, the predominant type of heart failure in our study was heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Currently, approximately 50% of patients hospitalized with ADHF have heart failure with preserved ejection fraction.[40] Our study adds to the understanding of prognosis of these patients whose heart failure pathophysiology is not well understood. Finally, palliative care services are underutilized in patients with advanced heart failure.[41, 42] IVC measurements and other prognostic markers in heart failure may guide discussions about goals of care with patients and families, and facilitate timely referrals for palliative care services.

CONCLUSIONS

Point‐of‐care ultrasound evaluation of IVC diameter at the time of admission can be used to prognosticate patients hospitalized with acute decompensated heart failure. An admission IVCmax diameter 1.9 cm is associated with a higher rate of 90‐day and 180‐day readmission and mortality after hospitalization. Future studies should evaluate the combination of IVC characteristics with other markers of severity of illness to prognosticate patients with heart failure.

Disclosures

This study was supported by a grant from the Madrid‐Castilla la Mancha Society of Internal Medicine. Dr. Restrepo is partially supported by award number K23HL096054 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute or the National Institutes of Health. The authors report no conflicts of interest.

- , , , et al. Heart disease and stroke statistics—2015 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2015;131(4):e29–e322.

- , , . Hospitalization for congestive heart failure: United States, 2000–2010. NCHS Data Brief. 2012(108):1–8.

- , . Rehospitalization for heart failure: predict or prevent? Circulation. 2012;126(4):501–506.

- , , , et al. Generalizability and longitudinal outcomes of a national heart failure clinical registry: Comparison of Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) and non‐ADHERE Medicare beneficiaries. Am Heart J. 2010;160(5):885–892.

- , , , et al. Prognostic markers of acute decompensated heart failure: the emerging roles of cardiac biomarkers and prognostic scores. Arch Cardiovasc Dis. 2015;108(1):64–74.

- , , , et al. Comparison of hand‐carried ultrasound assessment of the inferior vena cava and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide for predicting readmission after hospitalization for acute decompensated heart failure. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2008;1(5):595–601.

- , , , , . Echocardiography in acute heart failure: current perspectives. J Card Fail. 2016;22(1):82–94.

- , , , , . Usefulness of a hand‐held ultrasound device for bedside examination of left ventricular function. Am J Cardiol. 2002;90(9):1038–1039.

- , , , , , . Feasibility of point‐of‐care echocardiography by internal medicine house staff. Am Heart J. 2004;147(3):476–481.

- , , , , , . The use of small personal ultrasound devices by internists without formal training in echocardiography. Eur J Echocardiogr. 2003;4(2):141–147.

- , , , et al. Diagnostic accuracy of hospitalist‐performed hand‐carried ultrasound echocardiography after a brief training program. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(6):340–349.

- , , , . Point‐of‐care multi‐organ ultrasound improves diagnostic accuracy in adults presenting to the emergency department with acute dyspnea. West J Emerg Med. 2016;17(1):46–53.

- , , , , , . Acute heart failure: the role of focused emergency cardiopulmonary ultrasound in identification and early management. Eur J Heart Fail. 2015;17(12):1223–1227.

- , , , et al. Hand‐carried echocardiography by hospitalists: a randomized trial. Am J Med. 2011;124(8):766–774.

- , , , et al. ESC guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008: the Task Force for the diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic heart failure 2008 of the European Society of Cardiology. Developed in collaboration with the Heart Failure Association of the ESC (HFA) and endorsed by the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine (ESICM). Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(10):933–989.

- , , , , , . Adaptation of the modified Barthel Index for use in physical medicine and rehabilitation in Turkey. Scand J Rehabil Med. 2000;32(2):87–92.

- , , , . Complications, comorbidities, and mortality: improving classification and prediction. Health Serv Res. 1997;32(2):229–238; discussion 239–242.

- , , , et al. Guidelines for the echocardiographic assessment of the right heart in adults: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography endorsed by the European Association of Echocardiography, a registered branch of the European Society of Cardiology, and the Canadian Society of Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2010;23(7):685–713; quiz 786–688.

- , , , et al. Recommendations for chamber quantification: a report from the American Society of Echocardiography's Guidelines and Standards Committee and the Chamber Quantification Writing Group, developed in conjunction with the European Association of Echocardiography, a branch of the European Society of Cardiology. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2005;18(12):1440–1463.

- , , , , . Mortality and functional evolution at one year after hospital admission due to heart failure (HF) in elderly patients. Arch Gerontol Geriatr. 2012;54(1):261–265.

- , , , et al. Early and long‐term outcomes of heart failure in elderly persons, 2001–2005. Arch Intern Med. 2008;168(22):2481–2488.

- , , , et al. IVC diameter in patients with chronic heart failure: relationships and prognostic significance. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;6(1):16–28.

- , , , et al. Prognostic significance of dilated inferior vena cava in advanced decompensated heart failure. Int J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2014;30(7):1289–1295.

- , , . A dilated inferior vena cava is a marker of poor survival. Am Heart J. 2006;151(3):730–735.

- , , , et al. Predischarge B‐type natriuretic peptide assay for identifying patients at high risk of re‐admission after decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2004;43(4):635–641.

- , , , et al. A rapid bedside test for B‐type peptide predicts treatment outcomes in patients admitted for decompensated heart failure: a pilot study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37(2):386–391.

- , , , , , . N‐terminal‐pro‐brain natriuretic peptide predicts outcome after hospital discharge in heart failure patients. Circulation. 2004;110(15):2168–2174.

- , , , , , . Lowered B‐type natriuretic peptide in response to levosimendan or dobutamine treatment is associated with improved survival in patients with severe acutely decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2009;53(25):2343–2348.

- , , , . Long‐term clinical variation of NT‐proBNP in stable chronic heart failure patients. Eur Heart J. 2007;28(2):177–182.

- , , , et al. Right atrial volume index in chronic systolic heart failure and prognosis. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2009;2(5):527–534.

- , , , et al. Pulmonary pressures and death in heart failure: a community study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2012;59(3):222–231.

- , , , et al. A comparison by medicine residents of physical examination versus hand‐carried ultrasound for estimation of right atrial pressure. Am J Cardiol. 2007;99(11):1614–1616.

- , , . Noninvasive estimation of right atrial pressure from the inspiratory collapse of the inferior vena cava. Am J Cardiol. 1990;66(4):493–496.

- , , , , , . Relationship between right and left‐sided filling pressures in 1000 patients with advanced heart failure. J Heart Lung Transplant. 1999;18(11):1126–1132.

- , , , et al. Admission B‐type natriuretic peptide levels and in‐hospital mortality in acute decompensated heart failure. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;49(19):1943–1950.

- , , , et al. State of the art: using natriuretic peptide levels in clinical practice. Eur J Heart Fail. 2008;10(9):824–839.

- , , , et al. Readmission after hospitalization for congestive heart failure among Medicare beneficiaries. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157(1):99–104.

- , , , et al. Inferior vena cava parameters predict re‐admission in ischaemic heart failure. Eur J Clin Invest. 2014;44(4):341–349.

- , , , et al. Estimation of right atrial pressure on inferior vena cava ultrasound in Asian patients. Circ J. 2014;78(4):962–966.

- , , , , . Clinical presentation, management, and in‐hospital outcomes of patients admitted with acute decompensated heart failure with preserved systolic function: a report from the Acute Decompensated Heart Failure National Registry (ADHERE) Database. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47(1):76–84.

- , , , , . Palliative care referral among patients hospitalized with advanced heart failure. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(10):1115–1120.

- , , . Engaging heart failure clinicians to increase palliative care referrals: overcoming barriers, improving techniques. J Palliat Med. 2014;17(7):753–760.

Heart failure costs the United States an excess of $30 billion annually, and costs are projected to increase to nearly $70 billion by 2030.[1] Heart failure accounts for over 1 million hospitalizations and is the leading cause of hospitalization in patients >65 years of age.[2] After hospitalization, approximately 50% of patients are readmitted within 6 months of hospital discharge.[3] Mortality rates from heart failure have improved but remain high.[4] Approximately 50% of patients diagnosed with heart failure die within 5 years, and the overall 1‐year mortality rate is 30%.[1]

Prognostic markers and scoring systems for acute decompensated heart failure (ADHF) continue to emerge, but few bedside tools are available to clinicians. Age, brain natriuretic peptide, and N‐terminal pro‐brain natriuretic peptide (NT‐proBNP) levels have been shown to correlate with postdischarge rates of readmission and mortality.[5] A study evaluating the prognostic value of a bedside inferior vena cava (IVC) ultrasound exam demonstrated that lack of improvement in IVC distention from admission to discharge was associated with higher 30‐day readmission rates.[6] Two studies using data from comprehensive transthoracic echocardiograms in heart failure patients demonstrated that a dilated, noncollapsible IVC is associated with higher risk of mortality; however, it is well recognized that obtaining comprehensive transthoracic echocardiograms in all patients hospitalized with heart failure is neither cost‐effective nor practical.[7]