User login

High-Flow Oxygen after Extubation Reduces Reintubation

Clinical question: Does nasal high-flow (NHF) oxygen after extubation reduce reintubation rates in low-risk patients?

Background: NHF oxygen devices deliver warmed and humidified oxygen up to 60 liters per minutes. NHF provides positive end-expiratory pressure and dead-space washout. NHF in higher-risk post-extubation patients has been shown to have clinical benefits. Whether NHF post-extubation benefits patients at low risk of reintubation is unknown.

Study design: Randomized control trial (RCT).

Setting: Seven ICUs in Spain.

Synopsis: In this RCT, post-extubation NHF oxygen for 24 hours reduced the risk of reintubation among 527 ICU adults at low risk of reintubation when compared to conventional oxygen therapy (by nasal cannula or face mask). Patients with hypercapnia during weaning trials were excluded. The risk of reintubation was 4.9% versus 12.2% in NHF versus standard oxygen therapy, with an absolute difference of 7.2% (95% CI, 2.5–12.2%; P=0.004). ICU length of stay and mortality were not significantly different between the groups. The strengths of the study were adequate sample size, prespecified criteria for reintubation, and low number of crossover patients.

Limitations of the trial were the high percentage of surgical and neurologic cases, exclusion of patients with a variety of common comorbidities, and the inability to blind the physicians to the treatment arm of the subjects. Select patients may benefit from noninvasive ventilation to prevent reintubation, which was not studied. These results are highly relevant to post-extubation patients, with the optimum therapy for low-risk patients now appearing to be NHF.

Bottom line: NHF oxygen reduced reintubation compared to conventional oxygen therapy (nasal cannula or face mask) in extubated patients at low risk of reintubation.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711.

Clinical question: Does nasal high-flow (NHF) oxygen after extubation reduce reintubation rates in low-risk patients?

Background: NHF oxygen devices deliver warmed and humidified oxygen up to 60 liters per minutes. NHF provides positive end-expiratory pressure and dead-space washout. NHF in higher-risk post-extubation patients has been shown to have clinical benefits. Whether NHF post-extubation benefits patients at low risk of reintubation is unknown.

Study design: Randomized control trial (RCT).

Setting: Seven ICUs in Spain.

Synopsis: In this RCT, post-extubation NHF oxygen for 24 hours reduced the risk of reintubation among 527 ICU adults at low risk of reintubation when compared to conventional oxygen therapy (by nasal cannula or face mask). Patients with hypercapnia during weaning trials were excluded. The risk of reintubation was 4.9% versus 12.2% in NHF versus standard oxygen therapy, with an absolute difference of 7.2% (95% CI, 2.5–12.2%; P=0.004). ICU length of stay and mortality were not significantly different between the groups. The strengths of the study were adequate sample size, prespecified criteria for reintubation, and low number of crossover patients.

Limitations of the trial were the high percentage of surgical and neurologic cases, exclusion of patients with a variety of common comorbidities, and the inability to blind the physicians to the treatment arm of the subjects. Select patients may benefit from noninvasive ventilation to prevent reintubation, which was not studied. These results are highly relevant to post-extubation patients, with the optimum therapy for low-risk patients now appearing to be NHF.

Bottom line: NHF oxygen reduced reintubation compared to conventional oxygen therapy (nasal cannula or face mask) in extubated patients at low risk of reintubation.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711.

Clinical question: Does nasal high-flow (NHF) oxygen after extubation reduce reintubation rates in low-risk patients?

Background: NHF oxygen devices deliver warmed and humidified oxygen up to 60 liters per minutes. NHF provides positive end-expiratory pressure and dead-space washout. NHF in higher-risk post-extubation patients has been shown to have clinical benefits. Whether NHF post-extubation benefits patients at low risk of reintubation is unknown.

Study design: Randomized control trial (RCT).

Setting: Seven ICUs in Spain.

Synopsis: In this RCT, post-extubation NHF oxygen for 24 hours reduced the risk of reintubation among 527 ICU adults at low risk of reintubation when compared to conventional oxygen therapy (by nasal cannula or face mask). Patients with hypercapnia during weaning trials were excluded. The risk of reintubation was 4.9% versus 12.2% in NHF versus standard oxygen therapy, with an absolute difference of 7.2% (95% CI, 2.5–12.2%; P=0.004). ICU length of stay and mortality were not significantly different between the groups. The strengths of the study were adequate sample size, prespecified criteria for reintubation, and low number of crossover patients.

Limitations of the trial were the high percentage of surgical and neurologic cases, exclusion of patients with a variety of common comorbidities, and the inability to blind the physicians to the treatment arm of the subjects. Select patients may benefit from noninvasive ventilation to prevent reintubation, which was not studied. These results are highly relevant to post-extubation patients, with the optimum therapy for low-risk patients now appearing to be NHF.

Bottom line: NHF oxygen reduced reintubation compared to conventional oxygen therapy (nasal cannula or face mask) in extubated patients at low risk of reintubation.

Citation: Hernández G, Vaquero C, González P, et al. Effect of postextubation high-flow nasal cannula vs conventional oxygen therapy on reintubation in low-risk patients: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2016;315(13):1354-1361. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2711.

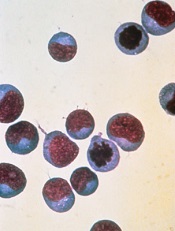

Study explains how a mutation spurs AML development

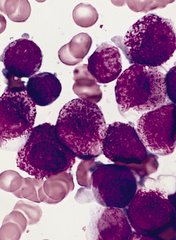

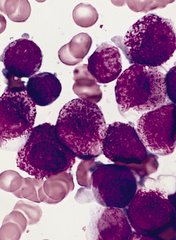

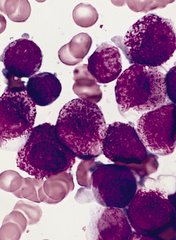

A set of faulty genetic instructions keeps hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) from maturing and contributes to the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Cancer Cell.

Researchers found that a mutation in the gene DNMT3A removes a “brake” on the activity of stemness genes, which leads to the creation of immature precursor cells that can become AML cells.

Specifically, the DNMT3A mutational hotspot at Arg882 (DNMT3AR882H) cooperates with an NRAS mutation (NRASG12D) to transform HSPCs and induce AML development.

“Due to a large-scale cancer sequencing project, the DNMT3A gene is now appreciated to be one of the top 3 most frequently mutated genes in human acute myeloid leukemia, and yet the role of its mutation in the disease has remained far from clear,” said G. Greg Wang, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill.

“Our findings not only provide a deeper understanding of how this prevalent mutation contributes to the development of AML, but it also offers useful information on how to develop new strategies to treat AML patients.”

In an attempt to understand how the DNMT3A mutation helps drive AML, Dr Wang and his colleagues created one of the first laboratory AML models for studying somatic mutations in DNMT3A.

The DNMT3A gene codes for a protein that binds to specific sections of DNA with a chemical tag that can influence the activity and expression of the underlying genes in cells.

The researchers found that DNMT3AR882H caused AML cells to have a different pattern of chemical tags that affect how the genetic code is interpreted and how the cell develops.

In cancerous cells with DNMT3AR882H, a set of gene enhancers for several stemness genes—including Meis1, Mn1, and the Hoxa gene cluster—were left unchecked. Therefore, HSPCs were left with a constant “on” switch, allowing the cells to “forget” to mature.

“In acute myeloid leukemia, the expression of these stemness genes are aberrantly maintained at a higher level,” Dr Wang said. “As a result, cells ‘forget’ to proceed to normal differentiation and maturation, generating immature precursor blood cells and a prelude to full-blown cancer.”

The researchers also found that, while the DNMT3A mutation is required for AML development, the mutation itself is not sufficient to cause cancer alone. DNMT3AR882H cooperates with another mutation, NRASG12D.

“We found the RAS mutation stimulates these immature blood cells to be hyper-proliferate,” said study author Rui Lu, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“However, these cells cannot maintain their stem cell properties. While the DNMT3A mutation itself does not have hyper-proliferative effects, [it] does promote stemness properties and generates leukemia stem/initiating cells together with the RAS mutation.”

The researchers also reported testing a potential treatment in cells with the DNMT3A mutation. They found that AML cells with DNMT3AR882H were sensitive to inhibitors of DOT1L, a cellular enzyme involved in modulation of gene expression activities.

As DOT1L inhibitors are currently under clinical investigation, this finding suggests a potential strategy for treating DNMT3A-mutated AML. ![]()

A set of faulty genetic instructions keeps hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) from maturing and contributes to the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Cancer Cell.

Researchers found that a mutation in the gene DNMT3A removes a “brake” on the activity of stemness genes, which leads to the creation of immature precursor cells that can become AML cells.

Specifically, the DNMT3A mutational hotspot at Arg882 (DNMT3AR882H) cooperates with an NRAS mutation (NRASG12D) to transform HSPCs and induce AML development.

“Due to a large-scale cancer sequencing project, the DNMT3A gene is now appreciated to be one of the top 3 most frequently mutated genes in human acute myeloid leukemia, and yet the role of its mutation in the disease has remained far from clear,” said G. Greg Wang, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill.

“Our findings not only provide a deeper understanding of how this prevalent mutation contributes to the development of AML, but it also offers useful information on how to develop new strategies to treat AML patients.”

In an attempt to understand how the DNMT3A mutation helps drive AML, Dr Wang and his colleagues created one of the first laboratory AML models for studying somatic mutations in DNMT3A.

The DNMT3A gene codes for a protein that binds to specific sections of DNA with a chemical tag that can influence the activity and expression of the underlying genes in cells.

The researchers found that DNMT3AR882H caused AML cells to have a different pattern of chemical tags that affect how the genetic code is interpreted and how the cell develops.

In cancerous cells with DNMT3AR882H, a set of gene enhancers for several stemness genes—including Meis1, Mn1, and the Hoxa gene cluster—were left unchecked. Therefore, HSPCs were left with a constant “on” switch, allowing the cells to “forget” to mature.

“In acute myeloid leukemia, the expression of these stemness genes are aberrantly maintained at a higher level,” Dr Wang said. “As a result, cells ‘forget’ to proceed to normal differentiation and maturation, generating immature precursor blood cells and a prelude to full-blown cancer.”

The researchers also found that, while the DNMT3A mutation is required for AML development, the mutation itself is not sufficient to cause cancer alone. DNMT3AR882H cooperates with another mutation, NRASG12D.

“We found the RAS mutation stimulates these immature blood cells to be hyper-proliferate,” said study author Rui Lu, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“However, these cells cannot maintain their stem cell properties. While the DNMT3A mutation itself does not have hyper-proliferative effects, [it] does promote stemness properties and generates leukemia stem/initiating cells together with the RAS mutation.”

The researchers also reported testing a potential treatment in cells with the DNMT3A mutation. They found that AML cells with DNMT3AR882H were sensitive to inhibitors of DOT1L, a cellular enzyme involved in modulation of gene expression activities.

As DOT1L inhibitors are currently under clinical investigation, this finding suggests a potential strategy for treating DNMT3A-mutated AML. ![]()

A set of faulty genetic instructions keeps hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells (HSPCs) from maturing and contributes to the development of acute myeloid leukemia (AML), according to research published in Cancer Cell.

Researchers found that a mutation in the gene DNMT3A removes a “brake” on the activity of stemness genes, which leads to the creation of immature precursor cells that can become AML cells.

Specifically, the DNMT3A mutational hotspot at Arg882 (DNMT3AR882H) cooperates with an NRAS mutation (NRASG12D) to transform HSPCs and induce AML development.

“Due to a large-scale cancer sequencing project, the DNMT3A gene is now appreciated to be one of the top 3 most frequently mutated genes in human acute myeloid leukemia, and yet the role of its mutation in the disease has remained far from clear,” said G. Greg Wang, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center in Chapel Hill.

“Our findings not only provide a deeper understanding of how this prevalent mutation contributes to the development of AML, but it also offers useful information on how to develop new strategies to treat AML patients.”

In an attempt to understand how the DNMT3A mutation helps drive AML, Dr Wang and his colleagues created one of the first laboratory AML models for studying somatic mutations in DNMT3A.

The DNMT3A gene codes for a protein that binds to specific sections of DNA with a chemical tag that can influence the activity and expression of the underlying genes in cells.

The researchers found that DNMT3AR882H caused AML cells to have a different pattern of chemical tags that affect how the genetic code is interpreted and how the cell develops.

In cancerous cells with DNMT3AR882H, a set of gene enhancers for several stemness genes—including Meis1, Mn1, and the Hoxa gene cluster—were left unchecked. Therefore, HSPCs were left with a constant “on” switch, allowing the cells to “forget” to mature.

“In acute myeloid leukemia, the expression of these stemness genes are aberrantly maintained at a higher level,” Dr Wang said. “As a result, cells ‘forget’ to proceed to normal differentiation and maturation, generating immature precursor blood cells and a prelude to full-blown cancer.”

The researchers also found that, while the DNMT3A mutation is required for AML development, the mutation itself is not sufficient to cause cancer alone. DNMT3AR882H cooperates with another mutation, NRASG12D.

“We found the RAS mutation stimulates these immature blood cells to be hyper-proliferate,” said study author Rui Lu, PhD, of the University of North Carolina Lineberger Comprehensive Cancer Center.

“However, these cells cannot maintain their stem cell properties. While the DNMT3A mutation itself does not have hyper-proliferative effects, [it] does promote stemness properties and generates leukemia stem/initiating cells together with the RAS mutation.”

The researchers also reported testing a potential treatment in cells with the DNMT3A mutation. They found that AML cells with DNMT3AR882H were sensitive to inhibitors of DOT1L, a cellular enzyme involved in modulation of gene expression activities.

As DOT1L inhibitors are currently under clinical investigation, this finding suggests a potential strategy for treating DNMT3A-mutated AML. ![]()

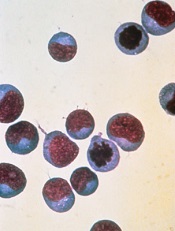

EMA recommends authorization of T-cell product

Image courtesy of NIAID

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended granting conditional marketing authorization for a T-cell product known as Zalmoxis.

Zalmoxis is intended for use as an adjunctive therapy to aid immune reconstitution and help treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adults receiving a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant to treat hematologic malignancy.

Zalmoxis consists of allogeneic T cells genetically modified with a retroviral vector encoding for a truncated form of the human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (ΔLNGFR) and the herpes simplex I virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK Mut2).

This modification makes the T cells susceptible to treatment with the drug ganciclovir. So if a patient develops GVHD, he can be treated with ganciclovir, which should kill the modified T cells and prevent further development of the disease.

Zalmoxis is being developed by MolMed S.p.A.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recommended conditional approval for Zalmoxis. Conditional approval is one of the agency’s main mechanisms to facilitate earlier access to medicines that fulfill unmet medical needs.

Conditional approval allows the EMA to recommend a medicine for marketing authorization before the availability of confirmatory clinical trial data, if the benefits of making this medicine available to patients immediately outweigh the risks inherent in the lack of comprehensive data.

Zalmoxis was also assessed by the Committee on Advanced Therapies (CAT), the EMA’s specialized scientific committee for advanced therapy medicinal products, such as gene or cell therapies.

At its June 2016 meeting, the CAT recommended a conditional marketing authorization for Zalmoxis. The CHMP then considered the CAT’s recommendation and agreed with it.

The recommendation has been sent to the European Commission, which will adopt a decision on marketing authorization that will apply to the European Economic Area.

If Zalmoxis is granted conditional marketing authorization, MolMed S.p.A. must provide the EMA with results from an ongoing phase 3 trial (TK008; NCT00914628).

Until the complete data from this trial are available, the CAT and the CHMP will review the benefits and risks of Zalmoxis annually to determine whether the conditional marketing authorization can be maintained.

Zalmoxis was designated as an orphan medicinal product in 2003. Orphan designation gives drug developers access to incentives such as fee reductions for scientific advice and the opportunity to obtain 10 years of market exclusivity for an authorized orphan-designated medicine. ![]()

Image courtesy of NIAID

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended granting conditional marketing authorization for a T-cell product known as Zalmoxis.

Zalmoxis is intended for use as an adjunctive therapy to aid immune reconstitution and help treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adults receiving a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant to treat hematologic malignancy.

Zalmoxis consists of allogeneic T cells genetically modified with a retroviral vector encoding for a truncated form of the human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (ΔLNGFR) and the herpes simplex I virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK Mut2).

This modification makes the T cells susceptible to treatment with the drug ganciclovir. So if a patient develops GVHD, he can be treated with ganciclovir, which should kill the modified T cells and prevent further development of the disease.

Zalmoxis is being developed by MolMed S.p.A.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recommended conditional approval for Zalmoxis. Conditional approval is one of the agency’s main mechanisms to facilitate earlier access to medicines that fulfill unmet medical needs.

Conditional approval allows the EMA to recommend a medicine for marketing authorization before the availability of confirmatory clinical trial data, if the benefits of making this medicine available to patients immediately outweigh the risks inherent in the lack of comprehensive data.

Zalmoxis was also assessed by the Committee on Advanced Therapies (CAT), the EMA’s specialized scientific committee for advanced therapy medicinal products, such as gene or cell therapies.

At its June 2016 meeting, the CAT recommended a conditional marketing authorization for Zalmoxis. The CHMP then considered the CAT’s recommendation and agreed with it.

The recommendation has been sent to the European Commission, which will adopt a decision on marketing authorization that will apply to the European Economic Area.

If Zalmoxis is granted conditional marketing authorization, MolMed S.p.A. must provide the EMA with results from an ongoing phase 3 trial (TK008; NCT00914628).

Until the complete data from this trial are available, the CAT and the CHMP will review the benefits and risks of Zalmoxis annually to determine whether the conditional marketing authorization can be maintained.

Zalmoxis was designated as an orphan medicinal product in 2003. Orphan designation gives drug developers access to incentives such as fee reductions for scientific advice and the opportunity to obtain 10 years of market exclusivity for an authorized orphan-designated medicine. ![]()

Image courtesy of NIAID

The European Medicines Agency (EMA) has recommended granting conditional marketing authorization for a T-cell product known as Zalmoxis.

Zalmoxis is intended for use as an adjunctive therapy to aid immune reconstitution and help treat graft-versus-host disease (GVHD) in adults receiving a haploidentical hematopoietic stem cell transplant to treat hematologic malignancy.

Zalmoxis consists of allogeneic T cells genetically modified with a retroviral vector encoding for a truncated form of the human low affinity nerve growth factor receptor (ΔLNGFR) and the herpes simplex I virus thymidine kinase (HSV-TK Mut2).

This modification makes the T cells susceptible to treatment with the drug ganciclovir. So if a patient develops GVHD, he can be treated with ganciclovir, which should kill the modified T cells and prevent further development of the disease.

Zalmoxis is being developed by MolMed S.p.A.

The EMA’s Committee for Medicinal Products for Human Use (CHMP) recommended conditional approval for Zalmoxis. Conditional approval is one of the agency’s main mechanisms to facilitate earlier access to medicines that fulfill unmet medical needs.

Conditional approval allows the EMA to recommend a medicine for marketing authorization before the availability of confirmatory clinical trial data, if the benefits of making this medicine available to patients immediately outweigh the risks inherent in the lack of comprehensive data.

Zalmoxis was also assessed by the Committee on Advanced Therapies (CAT), the EMA’s specialized scientific committee for advanced therapy medicinal products, such as gene or cell therapies.

At its June 2016 meeting, the CAT recommended a conditional marketing authorization for Zalmoxis. The CHMP then considered the CAT’s recommendation and agreed with it.

The recommendation has been sent to the European Commission, which will adopt a decision on marketing authorization that will apply to the European Economic Area.

If Zalmoxis is granted conditional marketing authorization, MolMed S.p.A. must provide the EMA with results from an ongoing phase 3 trial (TK008; NCT00914628).

Until the complete data from this trial are available, the CAT and the CHMP will review the benefits and risks of Zalmoxis annually to determine whether the conditional marketing authorization can be maintained.

Zalmoxis was designated as an orphan medicinal product in 2003. Orphan designation gives drug developers access to incentives such as fee reductions for scientific advice and the opportunity to obtain 10 years of market exclusivity for an authorized orphan-designated medicine. ![]()

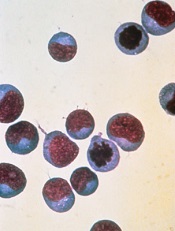

Febrile, Immunocompromised Man With Rash

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

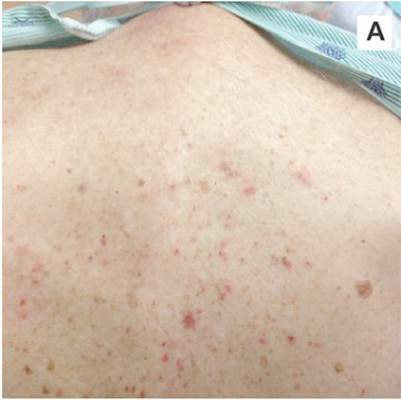

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

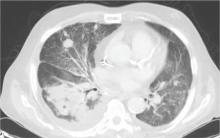

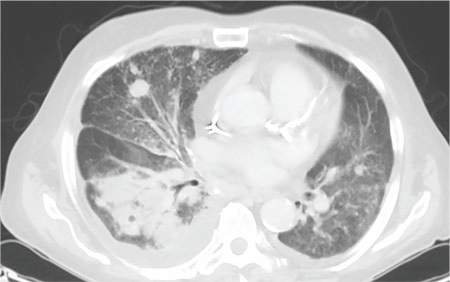

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|

|

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

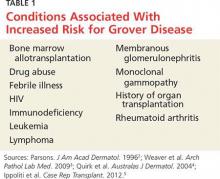

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

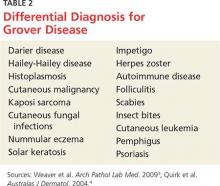

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

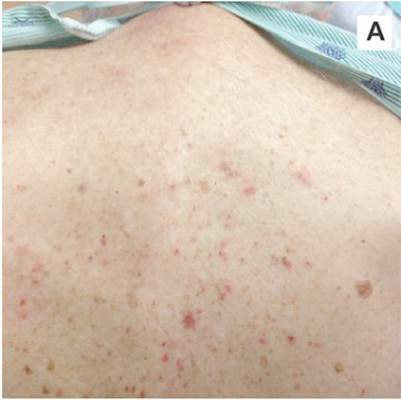

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|

|

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

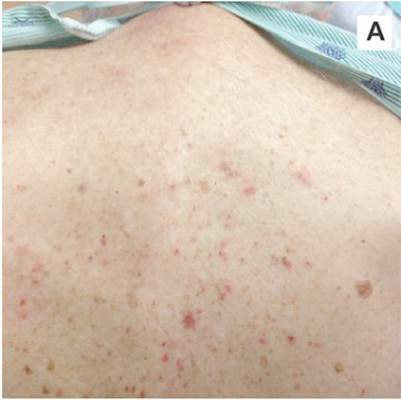

IN THIS ARTICLE

- Conditions associated with increased risk for case disease

- Outcome for the case patient

- Differential diagnosis

A 78-year-old white man with chronic lymphocytic leukemia is admitted to the hospital with worsening cough, shortness of breath, and fever. His medical history is significant for pneumonia caused by Pneumocystis jirovecii in the past year. In the weeks preceding hospital admission, the patient developed an erythematous rash over his trunk (see photographs).

During the man’s hospital stay, this eruption becomes increasingly pruritic and spreads to his proximal extremities. His pulmonary symptoms improve slightly following the initiation of broad-spectrum antibiotic therapy (piperacillin/tazobactam and vancomycin), but CT performed one week after admission reveals worsening pulmonary disease (see image). The radiologist’s differential diagnosis includes neoplasm, fungal infection, Kaposi sarcoma, and autoimmune disease.

|

|

| A. The patient's back shows a distribution of lesions, with areas of excoriation caused by scratching. | B. A close-up reveals erythematous papules and keratotic papules. |

Suspecting that the progressive rash is related to the systemic process, the provider orders a punch biopsy in an effort to reach a diagnosis with minimally invasive studies. When the patient’s clinical status further declines, he undergoes video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery to obtain an excisional biopsy of one of the pulmonary nodules. Subsequent analysis reveals fungal organisms consistent with histoplasmosis. Interestingly, in the histologic review of the skin biopsy, focal acantholytic dyskeratosis—suggestive of Grover disease—is identified.

Continue for discussion >>

DISCUSSION

Grover disease (GD), also known as transient acantholytic dermatosis, is a skin condition of uncertain pathophysiology. Its clinical presentation can be difficult to distinguish from other dermopathies.1,2

Incidence

GD most commonly appears in fair-skinned persons of late middle age, with men affected at two to three times the rate seen in women.1,2 Although GD has been documented in patients ranging in age from 4 to 100, this dermopathy is rare in younger patients.1-3 Persons with a prior history of atopic dermatitis, contact dermatitis, or xerosis cutis are at increased risk for GD—likely due to an increased dermatologic sensitivity to irritants resulting from the aforementioned disorders.1,4 Risk for GD is also elevated in patients with chronic medical conditions, immunodeficiency, febrile illnesses, or malignancies (see Table 1).2-5

The true incidence of GD is not known; biopsy-proven GD is uncommon, and specific data on the incidence and prevalence of the condition are lacking. Swiss researchers who reviewed more than 30,000 skin biopsies in the late 1990s noted only 24 diagnosed cases of GD, and similar findings have been reported in the United States.1,6 However, the variable presentation and often mild nature of GD may result in cases of misdiagnosis, lack of diagnosis, or empiric treatment in the absence of a formal diagnosis.7

Causative factors

Although the pathophysiology of GD is uncertain, the most likely cause is an occlusion of the eccrine glands.3 This is followed by acantholysis, or separation of keratinocytes within the epidermis, which in turn leads to the development of vesicular lesions.

Though diagnosed most often in the winter, GD has also been associated with exposure to sunlight, heat, xerosis, and diaphoresis.1,3 Hospitalized or bedridden patients are at risk for occlusion of the eccrine glands and thus for GD. Use of certain therapies, including sulfadoxine/pyrimethamine (an antimalarial treatment), ionizing radiation, and interleukin-4, may also be precursors for the condition.2

Other exacerbating factors have been suggested, but reports are largely limited to case studies and other anecdotal publications.2 Concrete data regarding the etiology and pathophysiology of GD are still relatively scarce.

Clinical presentation

Patients with GD present with pruritic dermatitis on the trunk and proximal extremities, most classically on the anterior chest and mid back.2,3 The severity of the rash does not necessarily correlate to the degree of pruritus. Some patients report only mild pruritus, while others experience debilitating discomfort and pain. In most cases, erythematous and violaceous papules and vesicles appear first, followed by keratotic erosions.3

GD is a self-limited disorder that often resolves within a few weeks, although some cases will persist for several months.3,5 Severity and duration of symptoms appear to be correlated with increasing age; elderly patients experience worse pruritus for longer periods than do younger patients.2

Although the condition is sometimes referred to as transient acantholytic dermatosis, there are three typical presentations of GD: transient eruptive, persistent pruritic, and chronic asymptomatic.4 Transient eruptive GD presents suddenly, with intense pruritus, and tends to subside over several weeks. Persistent pruritic disease generally causes a milder pruritus, with symptoms that last for several months and are not well controlled by medication. Chronic asymptomatic GD can be difficult to treat medically, yet this form of the disease typically causes little to no irritation and requires minimal therapeutic intervention.4

Systemic symptoms of GD have not been observed. Pruritus and rash are the main features in most affected patients. However, pruritic papulovesicular eruptions are commonly seen in other conditions with similar characteristics (see Table 2,3,4), and GD is comparatively rare. While clinical appearance alone may suggest a diagnosis of GD, further testing may be needed to eliminate other conditions from the differential.

Treatment and prognosis

In the absence of randomized therapeutic trials for GD, there are no strict guidelines for treatment. When irritation, inflammation, and pruritus become bothersome, several interventions may be considered. The first step may consist of efforts to modify aggravating factors, such as dry skin, occlusion, excess heat, and rapid temperature changes. Indeed, for mild cases of GD, this may be all that is required.

The firstline pharmacotherapy for GD is medium- to high-potency topical corticosteroids, which reduce inflammation and pruritus in approximately half of affected patients.3,6,8 Topical emollients and oral antihistamines can also provide symptom relief. Vitamin D analogues are considered secondline therapy, and retinoids (both topical and systemic) have also been shown to reduce GD severity.3,4,8

Severe, refractory cases may require more aggressive systemic therapy with corticosteroids or retinoids. For pruritic relief, several weeks of oral corticosteroids may be necessary—and GD may rebound after treatment ceases.3,4 Therefore, oral corticosteroids should only be considered for severe or persistent cases, since the systemic adverse effects (eg, immunosuppression, weight gain, dysglycemia) of these drugs may outweigh the benefits in patients with GD. Other interventions, including phototherapy and immunosuppressive drugs (eg, etanercept) have also demonstrated benefit in select patients.4,9,10

The self-limited nature of GD, along with its lack of systemic symptoms, is associated with a generally benign course of disease and no long-term sequelae.3,5

Continue to outcome for the case patient >>

OUTCOME FOR THE CASE PATIENT

This case involved an immunocompromised patient with systemic symptoms, vasculitic cutaneous lesions, and significant pulmonary disease. The differential diagnosis was extensive, and diagnosis based on clinical grounds alone was extremely challenging. In these circumstances, diagnostic testing was essential to reach a final diagnosis.

In this case, the skin biopsy yielded a diagnosis of GD, and the rash was found to be unrelated to the patient’s systemic and pulmonary symptoms. The providers were then able to focus on the diagnosis of histoplasmosis, with only minimal intervention for the patient’s GD (ie, oral diphenhydramine prn for pruritus).

CONCLUSION

In many cases of GD, skin biopsy can guide providers when the history and physical examination do not yield a clear diagnosis. The histopathology of affected tissue can provide invaluable information about an underlying disease process, particularly in complex cases such as this patient’s. Skin biopsy provides a minimally invasive opportunity to obtain a diagnosis in patients with a condition that affects multiple organ systems, and its use should be considered in disease processes with cutaneous manifestations.

REFERENCES

1. Scheinfeld N, Mones J. Seasonal variation of transient acantholytic dyskeratosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2006;55(2): 263-268.

2. Parsons JM. Transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): a global perspective. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1996;35(5 part 1):653-666.

3. Weaver J, Bergfeld WF. Grover disease (transient acantholytic dermatosis). Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2009;133(9):1490-1494.

4. Quirk CJ, Heenan PJ. Grover’s disease: 34 years on. Australas J Dermatol. 2004;45(2):83-86.

5. Ippoliti G, Paulli M, Lucioni M, et al. Grover’s disease after heart transplantation: a case report. Case Rep Transplant. 2012;2012:126592.

6. Streit M, Paredes BE, Braathen LR, Brand CU. Transitory acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease): an analysis of the clinical spectrum based on 21 histologically assessed cases [in German]. Hautarzt. 2000;51:244-249.

7. Joshi R, Taneja A. Grover’s disease with acrosyringeal acantholysis: a rare histological presentation of an uncommon disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2014;59(6):621-623.

8. Riemann H, High WA. Grover’s disease (transient and persistent acantholytic dermatosis). UpToDate. 2015. www.uptodate.com/contents/grovers-disease-transient-and-persistent-acantholytic-dermatosis. Accessed June 4, 2016.

9. Breuckmann F, Appelhans C, Altmeyer P, Kreuter A. Medium-dose ultraviolet A1 phototherapy in transient acantholytic dermatosis (Grover’s disease). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2005;52(1):169-170.

10. Norman R, Chau V. Use of etanercept in treating pruritus and preventing new lesions in Grover disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64(4):796-798.

Peds, FPs flunk screening children for obstructive sleep apnea

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

DENVER – A high degree of unwarranted practice variation exists among pediatricians and family physicians with regard to screening children for obstructive sleep apnea in accord with current evidence-based practice guidelines, Sarah M. Honaker, Ph.D., said at the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and American Academy of Sleep Medicine recommend that children with frequent snoring be referred for a sleep study or to a sleep specialist or otolaryngologist because of the damaging consequences of living with untreated obstructive sleep apnea (OSA). But Dr. Honaker’s study of 8,135 children aged 1-12 years seen at five university-affiliated urban primary care pediatric clinics demonstrated that the identification rate of suspected OSA was abysmally low, and physician practice on this score varied enormously.

“There is a critical need to develop enhanced implementation strategies to support primary care providers’ adherence to evidence-based practice for pediatric OSA,” declared Dr. Honaker of Indiana University in Indianapolis.

She and her coinvestigators have developed a computer decision support system designed to do just that. Known as CHICA, for Child Health Improvement through Computer Automation, the system works like this: While in the clinic waiting room, the parent is handed a computer tablet and asked to complete 20 yes/no items designed to identify priority areas for the primary care provider to address during the current visit. The items are individually tailored based upon the child’s age, past medical history, and previous responses.

One item asks if the child snores three or more nights per week, a well-established indicator of increased risk for OSA. If the answer is yes, CHICA instantly sends a prompt to the child’s electronic medical record noting that the parent reports the child is a frequent snorer and this might indicate OSA.

The primary care provider can either ignore the prompt or respond during or after the visit in one of three ways: “I am concerned about OSA,” “I do not suspect OSA,” or “The parent in the examining room denies hearing frequent snoring.”

The mean age of the patients in Dr. Honaker’s study was 5.8 years, and 83% of the 8,135 children had Medicaid coverage. Parental cooperation with CHICA was high: 98.5% of parents addressed the snoring question. They reported that 28.5% of the children snored at least 3 nights per week, generating a total of 1,094 CHICA prompts to the primary care providers. Forty-four percent of providers didn’t respond to the prompt, which Dr. Honaker said is a typical rate for this sort of computerized assist intervention. Of those who did respond, only 15.9% indicated they suspected OSA. Sixty-three percent declared they didn’t suspect OSA, and the remainder said the parent in the examining room didn’t report frequent snoring.

Although responding providers indicated they suspected OSA in 15.9% of the children, that’s a low figure for frequent snorers. Moreover, 31% of children who got the CHICA frequent snoring prompt were overweight or obese, and 17% had attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder symptoms, both known risk factors for OSA. Some of the kids had both risk factors, but 39% had at least one in addition to their frequent snoring, Dr. Honaker noted.

The investigators carried out multivariate logistic regression analyses of child, provider, and clinic characteristics in search of predictors associated with physician concern that a child might have OSA. It turned out that none of the provider characteristics had any bearing on this endpoint. It didn’t matter if a physician’s specialty was pediatrics or family medicine. Providers had been in practice for 3-42 years, with a mean of 15.1 years, but years in practice weren’t associated with a physician’s rate of identification of possible pediatric OSA. Individual provider rates varied enormously, though. Some physicians never suspected OSA, others did so in nearly 50% of children flagged by the CHICA prompt.

“It’s not clear that type of training plays a large role in this area,” she commented.

The only relevant patient factor was age: children aged 1-2.5 years were 73% less likely to generate physician suspicion of OSA.

“Surprisingly, none of the patient health factors were predictive. So having ADHD symptoms or being overweight or obese did not make it more likely that a child would elicit concern for OSA,” Dr. Honaker observed.

However, which of the five clinics the child attended turned out to make a big difference. Rates of suspected OSA in children with a CHICA snoring prompt ranged from a low of 5% at one clinic to 27% at another.

Dr. Honaker’s recent review of the literature led her to conclude that the Indiana University experience is hardly unique. Despite documented high rates of pediatric sleep disorders in primary care settings, screening and treatment rates are low. Primary care physicians receive little training in sleep medicine (Sleep Med Rev. 2016;25:31-9).

What’s next for CHICA?

Dr. Honaker and coworkers have developed a beefed up CHICA decision support system known as the CHICA OSA Module. In addition to generating a prompt in the medical record if a parent indicates the child snores three or more nights per week, additional OSA signs and symptoms, if present, will be noted on the screen, along with a comment that American Academy of Pediatrics guidelines recommend referral when OSA is suspected. Dr. Honaker plans to conduct a controlled trial in which some clinics get the CHICA OSA Module while others use the older CHICA system.

Her study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. She reported having no financial conflicts.

AT SLEEP 2016

Key clinical point: Huge unwarranted practice variations exist in primary care physicians’ adherence to evidence-based guidelines for identification of obstructive sleep apnea in children.

Major finding: Although 39% of a large group of children reportedly snored at least three nights per week and had at least one additional major risk factor for obstructive sleep apnea, only 15.9% of the children elicited suspicion of the disorder on the part of primary care providers despite an electronic prompt.

Data source: This was an observational study in which 8,135 children aged 1-12 years were screened for obstructive sleep apnea using a computer-assisted decision support system known as CHICA, linked to the patients’ electronic medical record.

Disclosures: The study was funded by the American Sleep Medicine Foundation. The presenter reported having no financial conflicts.

IVUS has role for annular sizing in TAVR

PARIS – Intravascular ultrasound can reliably be used in lieu of multidetector computerized tomography for the key task of annular sizing in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, Dr. Diaa Hakim declared at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Multidetector CT (MDCT) is considered the standard imaging method for this purpose. But the requirement for contrast media makes MDCT problematic for patients with chronic kidney disease, who can easily be driven into acute kidney injury through exposure to this material.

Moreover, renal failure is common among patients with a failing native aortic valve. Interventionalists who perform transaortic valve replacement (TAVR) are encountering renal failure more and more frequently as the nonsurgical treatment takes off in popularity. An alternative imaging method is sorely needed, observed Dr. Hakim of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Unlike MDCT, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) doesn’t require contrast. And in Dr. Hakim’s head-to-head comparative trial conducted in 50 consecutive TAVR patients who underwent annular sizing by both methods, there were no significant differences between the two in measurements of maximum and minimum annular diameter, mean annular diameter, or annular area.

The decision as to the size of the replacement aortic valve was based upon MDCT, which was performed first. Then came IVUS carried out with a Boston Science Atlantis PV Peripheral IVUS catheter at 8-French and 15 Hz. The catheter was advanced over the guidewire, then pullback imaging was obtained automatically from the left ventricular outflow tract to the aortic root. The IVUS measurements were made at the level of basal attachment of the aortic valve cusps, which was quite close to the same point as the MDCT measurements.

Post TAVR, 37 of the 50 patients had no or trivial paravalvular regurgitation. Six patients developed acute kidney injury.

Asked if he believes IVUS now enables operators to routinely skip MDCT for TAVR patients, Dr. Hakim replied, “Not for the moment.” In patients with chronic kidney disease, yes, but in order for IVUS for annular sizing to expand beyond that population it will be necessary for device makers to develop an IVUS catheter with better visualization, a device designed specifically to see all the details of the aortic valve and annulus. He noted that the Atlantis PV Peripheral IVUS catheter employed in his study was designed for the aorta, not the aortic valve. It doesn’t provide optimal imaging of the valve cusps, nor can it measure paravalvular regurgitation after valve implantation.

How much time does IVUS for annular sizing add to the TAVR procedure? “Five minutes, no more,” according to Dr. Hakim.

He reported having no financial conflicts regarding this study, conducted free of commercial support.

PARIS – Intravascular ultrasound can reliably be used in lieu of multidetector computerized tomography for the key task of annular sizing in patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement, Dr. Diaa Hakim declared at the annual congress of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions.

Multidetector CT (MDCT) is considered the standard imaging method for this purpose. But the requirement for contrast media makes MDCT problematic for patients with chronic kidney disease, who can easily be driven into acute kidney injury through exposure to this material.

Moreover, renal failure is common among patients with a failing native aortic valve. Interventionalists who perform transaortic valve replacement (TAVR) are encountering renal failure more and more frequently as the nonsurgical treatment takes off in popularity. An alternative imaging method is sorely needed, observed Dr. Hakim of the University of Alabama at Birmingham.

Unlike MDCT, intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) doesn’t require contrast. And in Dr. Hakim’s head-to-head comparative trial conducted in 50 consecutive TAVR patients who underwent annular sizing by both methods, there were no significant differences between the two in measurements of maximum and minimum annular diameter, mean annular diameter, or annular area.

The decision as to the size of the replacement aortic valve was based upon MDCT, which was performed first. Then came IVUS carried out with a Boston Science Atlantis PV Peripheral IVUS catheter at 8-French and 15 Hz. The catheter was advanced over the guidewire, then pullback imaging was obtained automatically from the left ventricular outflow tract to the aortic root. The IVUS measurements were made at the level of basal attachment of the aortic valve cusps, which was quite close to the same point as the MDCT measurements.

Post TAVR, 37 of the 50 patients had no or trivial paravalvular regurgitation. Six patients developed acute kidney injury.