User login

Survey shines new light on weighty comorbidity burden in adult atopic dermatitis

VIENNA – Newly enhanced appreciation of the profound burden of comorbidities associated with adult atopic dermatitis (AD) is provided by the Liberty AD-AWARE study, investigators said at a joint program of the International Eczema Council and the International Psoriasis Council held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“I think the only reason we thought psoriasis is a systemic disease and atopic dermatitis is not is because people were researching it much more in psoriasis. I think atopic dermatitis will emerge as potentially more systemic than psoriasis, including the comorbidities. It’s just a matter of time before the evidence is put forth for atopic dermatitis,” predicted Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky noted that 85% of cases of AD begin before 5 years of age. Many cases resolve later in childhood, but for others it becomes a chronic lifelong condition. And while the burden of AD has been well characterized in the pediatric population, that’s not so in affected adults. This was the impetus for the Liberty AD-AWARE (Adults With Atopic Dermatitis Reporting on their Experience) study, an Internet-based cross-sectional survey of more than 1,500 adults with AD receiving their care from dermatologists at eight major U.S. academic medical centers.

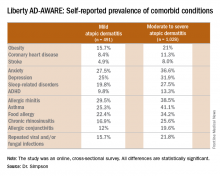

Eric L. Simpson, MD, a coinvestigator with Dr. Guttman-Yassky in Liberty AD-AWARE, observed that the study documented self-reported high rates of a range of psychiatric, cardiovascular, allergic, respiratory, and infectious diseases in participants. And while a cross-sectional study can’t establish causality, it’s important to appreciate that rates of these comorbidities were across the board significantly higher in the 1,028 patients with moderate to severe AD over the prior 12 months than in the 491 classified as having mild AD.

These associations between AD and mental health problems have been confirmed in other studies. For example, a recent analysis of data on more than 354,000 children and nearly 35,000 adults in the United States demonstrated that AD was independently associated with a 14% increased likelihood of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and a 61% increased risk in adults. Those risks of ADHD rose far higher in individuals with severe AD and sleep disruption (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:920-9).

A number of theories have been put forth to explain these associations, including altered brain development stemming from early exposure to inflammatory cytokines or perhaps shared genetic predisposition, but Dr. Simpson proposed a simpler explanation which carries more optimistic implications.

“I suspect the mental health problems associated with adult atopic dermatitis are probably nonspecific sequelae of any chronic skin disorder involving severe itch and sleep disturbances,” said Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Moreover, there is good reason to believe that novel therapies targeting inflammation more effectively than what’s been available to date may help improve mental health outcomes, as well as asthma in affected adults with AD, he added. He cited a phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study for which he was lead investigator. In this trial, 16 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, a first-in-class investigational blocker of the interleukin-4/interleukin-13 signaling pathway, not only resulted in significant reductions in itch and sleep problems, it also decreased anxiety and depression symptoms and improved multiple validated measures of health-related quality of life (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75[3]:506-15).

Liberty AD-AWARE provides hints of the profound cumulative negative impact moderate to severe AD can have on a patient’s life course. Among the group with moderate to severe disease, 7.5% said AD had a large negative effect on their pursuit of an education, 10.7% said their disease had influenced their career choice “a lot/very much,” 13.3% were unemployed for reasons other than being retired or a student, and 17.1% reported an annual family income of less than $25,000. All these rates were multifold higher than in patients with mild AD in the study, which didn’t include a non-AD control group.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky observed that 42% of the moderate to severe AD group in Liberty AD-AWARE reported their current treatments were ineffective at controlling their disease, even though study participants were presumably receiving high-quality care at academic medical centers. Twenty-eight percent of patients with inadequately controlled AD had used phototherapy or an immunomodulatory drug within the past 7 days, underscoring the limitations of those forms of therapy in patients with more severe AD as well as the need for new and better treatments.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has played a key role in the paradigm shift regarding understanding of the pathogenesis of AD as involving not just disordered skin barrier function but also immunologic impairment. She was senior author of a study that showed the nonlesional skin of patients with AD is characterized by high-level expression of inflammatory cytokines, whereas the nonlesional skin of psoriasis patients is not, an observation that serves to highlight the need for proactive treatments for AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Apr;127[4]:954-64.e1-4). Later, she and her coworkers demonstrated that AD is characterized by greater levels of T-cell activation among central and effector CD4+ and CD8+CLA+ and CD8+CLA– memory cell subsets (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Jul;136[1]:208-11).

More recently, she was also senior author of a landmark study that provides a mechanism to account for the reason AD patients would potentially have more comorbid illnesses than psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that AD is accompanied by systemic expansion of transitional and chronically activated memory B cells, plasmablasts, and IgE-expressing memory B cells in both skin and blood. In other words, AD is characterized by a greater level of systemic immune activation, compared with psoriasis, where activated T cells are largely confined to the skin, and activated central memory B cells don’t figure prominently (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Jan;137[1]:118-29.e5).

The Liberty AD-AWARE study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. Dr. Simpson and Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to those and other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – Newly enhanced appreciation of the profound burden of comorbidities associated with adult atopic dermatitis (AD) is provided by the Liberty AD-AWARE study, investigators said at a joint program of the International Eczema Council and the International Psoriasis Council held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“I think the only reason we thought psoriasis is a systemic disease and atopic dermatitis is not is because people were researching it much more in psoriasis. I think atopic dermatitis will emerge as potentially more systemic than psoriasis, including the comorbidities. It’s just a matter of time before the evidence is put forth for atopic dermatitis,” predicted Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky noted that 85% of cases of AD begin before 5 years of age. Many cases resolve later in childhood, but for others it becomes a chronic lifelong condition. And while the burden of AD has been well characterized in the pediatric population, that’s not so in affected adults. This was the impetus for the Liberty AD-AWARE (Adults With Atopic Dermatitis Reporting on their Experience) study, an Internet-based cross-sectional survey of more than 1,500 adults with AD receiving their care from dermatologists at eight major U.S. academic medical centers.

Eric L. Simpson, MD, a coinvestigator with Dr. Guttman-Yassky in Liberty AD-AWARE, observed that the study documented self-reported high rates of a range of psychiatric, cardiovascular, allergic, respiratory, and infectious diseases in participants. And while a cross-sectional study can’t establish causality, it’s important to appreciate that rates of these comorbidities were across the board significantly higher in the 1,028 patients with moderate to severe AD over the prior 12 months than in the 491 classified as having mild AD.

These associations between AD and mental health problems have been confirmed in other studies. For example, a recent analysis of data on more than 354,000 children and nearly 35,000 adults in the United States demonstrated that AD was independently associated with a 14% increased likelihood of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and a 61% increased risk in adults. Those risks of ADHD rose far higher in individuals with severe AD and sleep disruption (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:920-9).

A number of theories have been put forth to explain these associations, including altered brain development stemming from early exposure to inflammatory cytokines or perhaps shared genetic predisposition, but Dr. Simpson proposed a simpler explanation which carries more optimistic implications.

“I suspect the mental health problems associated with adult atopic dermatitis are probably nonspecific sequelae of any chronic skin disorder involving severe itch and sleep disturbances,” said Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Moreover, there is good reason to believe that novel therapies targeting inflammation more effectively than what’s been available to date may help improve mental health outcomes, as well as asthma in affected adults with AD, he added. He cited a phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study for which he was lead investigator. In this trial, 16 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, a first-in-class investigational blocker of the interleukin-4/interleukin-13 signaling pathway, not only resulted in significant reductions in itch and sleep problems, it also decreased anxiety and depression symptoms and improved multiple validated measures of health-related quality of life (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75[3]:506-15).

Liberty AD-AWARE provides hints of the profound cumulative negative impact moderate to severe AD can have on a patient’s life course. Among the group with moderate to severe disease, 7.5% said AD had a large negative effect on their pursuit of an education, 10.7% said their disease had influenced their career choice “a lot/very much,” 13.3% were unemployed for reasons other than being retired or a student, and 17.1% reported an annual family income of less than $25,000. All these rates were multifold higher than in patients with mild AD in the study, which didn’t include a non-AD control group.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky observed that 42% of the moderate to severe AD group in Liberty AD-AWARE reported their current treatments were ineffective at controlling their disease, even though study participants were presumably receiving high-quality care at academic medical centers. Twenty-eight percent of patients with inadequately controlled AD had used phototherapy or an immunomodulatory drug within the past 7 days, underscoring the limitations of those forms of therapy in patients with more severe AD as well as the need for new and better treatments.

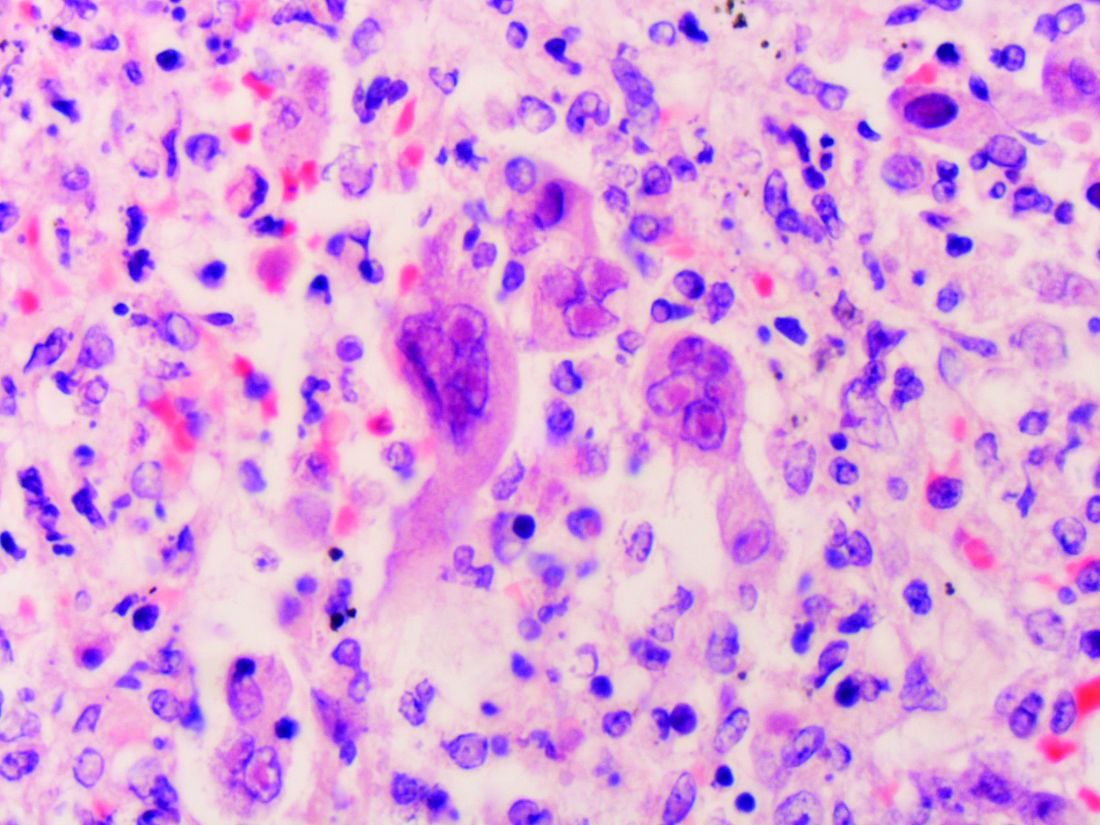

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has played a key role in the paradigm shift regarding understanding of the pathogenesis of AD as involving not just disordered skin barrier function but also immunologic impairment. She was senior author of a study that showed the nonlesional skin of patients with AD is characterized by high-level expression of inflammatory cytokines, whereas the nonlesional skin of psoriasis patients is not, an observation that serves to highlight the need for proactive treatments for AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Apr;127[4]:954-64.e1-4). Later, she and her coworkers demonstrated that AD is characterized by greater levels of T-cell activation among central and effector CD4+ and CD8+CLA+ and CD8+CLA– memory cell subsets (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Jul;136[1]:208-11).

More recently, she was also senior author of a landmark study that provides a mechanism to account for the reason AD patients would potentially have more comorbid illnesses than psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that AD is accompanied by systemic expansion of transitional and chronically activated memory B cells, plasmablasts, and IgE-expressing memory B cells in both skin and blood. In other words, AD is characterized by a greater level of systemic immune activation, compared with psoriasis, where activated T cells are largely confined to the skin, and activated central memory B cells don’t figure prominently (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Jan;137[1]:118-29.e5).

The Liberty AD-AWARE study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. Dr. Simpson and Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to those and other pharmaceutical companies.

VIENNA – Newly enhanced appreciation of the profound burden of comorbidities associated with adult atopic dermatitis (AD) is provided by the Liberty AD-AWARE study, investigators said at a joint program of the International Eczema Council and the International Psoriasis Council held in conjunction with the annual congress of the European Academy of Dermatology and Venereology.

“I think the only reason we thought psoriasis is a systemic disease and atopic dermatitis is not is because people were researching it much more in psoriasis. I think atopic dermatitis will emerge as potentially more systemic than psoriasis, including the comorbidities. It’s just a matter of time before the evidence is put forth for atopic dermatitis,” predicted Emma Guttman-Yassky, MD, PhD, professor and vice chair of the department of dermatology at Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky noted that 85% of cases of AD begin before 5 years of age. Many cases resolve later in childhood, but for others it becomes a chronic lifelong condition. And while the burden of AD has been well characterized in the pediatric population, that’s not so in affected adults. This was the impetus for the Liberty AD-AWARE (Adults With Atopic Dermatitis Reporting on their Experience) study, an Internet-based cross-sectional survey of more than 1,500 adults with AD receiving their care from dermatologists at eight major U.S. academic medical centers.

Eric L. Simpson, MD, a coinvestigator with Dr. Guttman-Yassky in Liberty AD-AWARE, observed that the study documented self-reported high rates of a range of psychiatric, cardiovascular, allergic, respiratory, and infectious diseases in participants. And while a cross-sectional study can’t establish causality, it’s important to appreciate that rates of these comorbidities were across the board significantly higher in the 1,028 patients with moderate to severe AD over the prior 12 months than in the 491 classified as having mild AD.

These associations between AD and mental health problems have been confirmed in other studies. For example, a recent analysis of data on more than 354,000 children and nearly 35,000 adults in the United States demonstrated that AD was independently associated with a 14% increased likelihood of attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder in children and a 61% increased risk in adults. Those risks of ADHD rose far higher in individuals with severe AD and sleep disruption (Br J Dermatol. 2016 Nov;175[5]:920-9).

A number of theories have been put forth to explain these associations, including altered brain development stemming from early exposure to inflammatory cytokines or perhaps shared genetic predisposition, but Dr. Simpson proposed a simpler explanation which carries more optimistic implications.

“I suspect the mental health problems associated with adult atopic dermatitis are probably nonspecific sequelae of any chronic skin disorder involving severe itch and sleep disturbances,” said Dr. Simpson, professor of dermatology at Oregon Health & Science University, Portland.

Moreover, there is good reason to believe that novel therapies targeting inflammation more effectively than what’s been available to date may help improve mental health outcomes, as well as asthma in affected adults with AD, he added. He cited a phase IIb, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study for which he was lead investigator. In this trial, 16 weeks of treatment with dupilumab, a first-in-class investigational blocker of the interleukin-4/interleukin-13 signaling pathway, not only resulted in significant reductions in itch and sleep problems, it also decreased anxiety and depression symptoms and improved multiple validated measures of health-related quality of life (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016 Sep;75[3]:506-15).

Liberty AD-AWARE provides hints of the profound cumulative negative impact moderate to severe AD can have on a patient’s life course. Among the group with moderate to severe disease, 7.5% said AD had a large negative effect on their pursuit of an education, 10.7% said their disease had influenced their career choice “a lot/very much,” 13.3% were unemployed for reasons other than being retired or a student, and 17.1% reported an annual family income of less than $25,000. All these rates were multifold higher than in patients with mild AD in the study, which didn’t include a non-AD control group.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky observed that 42% of the moderate to severe AD group in Liberty AD-AWARE reported their current treatments were ineffective at controlling their disease, even though study participants were presumably receiving high-quality care at academic medical centers. Twenty-eight percent of patients with inadequately controlled AD had used phototherapy or an immunomodulatory drug within the past 7 days, underscoring the limitations of those forms of therapy in patients with more severe AD as well as the need for new and better treatments.

Dr. Guttman-Yassky has played a key role in the paradigm shift regarding understanding of the pathogenesis of AD as involving not just disordered skin barrier function but also immunologic impairment. She was senior author of a study that showed the nonlesional skin of patients with AD is characterized by high-level expression of inflammatory cytokines, whereas the nonlesional skin of psoriasis patients is not, an observation that serves to highlight the need for proactive treatments for AD (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011 Apr;127[4]:954-64.e1-4). Later, she and her coworkers demonstrated that AD is characterized by greater levels of T-cell activation among central and effector CD4+ and CD8+CLA+ and CD8+CLA– memory cell subsets (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015 Jul;136[1]:208-11).

More recently, she was also senior author of a landmark study that provides a mechanism to account for the reason AD patients would potentially have more comorbid illnesses than psoriasis patients. The investigators demonstrated that AD is accompanied by systemic expansion of transitional and chronically activated memory B cells, plasmablasts, and IgE-expressing memory B cells in both skin and blood. In other words, AD is characterized by a greater level of systemic immune activation, compared with psoriasis, where activated T cells are largely confined to the skin, and activated central memory B cells don’t figure prominently (J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2016 Jan;137[1]:118-29.e5).

The Liberty AD-AWARE study was sponsored by Sanofi and Regeneron. Dr. Simpson and Dr. Guttman-Yassky reported receiving research grants from and serving as consultants to those and other pharmaceutical companies.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE EADV CONGRESS

Reasons for noncompliance to ketogenic diet explored

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

HOUSTON – More than one-third of children discontinued the ketogenic diet prior to completion of a 3-month trial because of reported difficulty, a single-center study showed.

The findings underscore the importance of carefully screening patients and their families prior to initiating the ketogenic diet, lead author Gogi Kumar, MD, said in an interview at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society. “We always talk about how and when the ketogenic diet should be used, but we don’t talk about the barriers to continuing the diet, like the socioeconomic aspects that determine the feasibility of continuing the diet,” said Dr. Kumar, a pediatric neurologist at Dayton (Ohio) Children’s Hospital. “If it’s a single mom who has two jobs and has a kid with intractable epilepsy, she cannot do it because ketogenic diets are complex and very intense. If the child has a gastrostomy tube and you can feed them a formula it might work, but then you have to bring them in for multiple lab tests. The family has to be very committed. They have to have resources.”

The mean age of study participants was 7.4 years, and feeding was accomplished orally in 43%, by tube in 40%, and both routes in 17%. Of the patients who were started on a ketogenic diet, 57% continued on the diet for more than 3 months. Overall, 55% of patients experienced at least a 50% reduction in seizures, while 45% experienced less than a 50% reduction in seizures.

Dr. Kumar went on to report that 15 patients (43%) discontinued the diet before the 3-month trial period. Of these 15 patients, 3 had adverse effects after initiation of the diet and the remaining 12 reported stopping the diet because of difficulty, 1 of whom also reported cost as a barrier. Of the 12 patients who stopped the diet because of difficulty, 8 were on the classic ketogenic diet and 4 were on other diet therapies. All were oral eaters and 50% lived in a single-parent household or had shared parenting in multiple households with poor communication. The remaining 50% had married parents, of whom 25% were teenagers who did not want to commit to the diet and 25% were children with parents who found the diet difficult. Of families who discontinued the diet early, 58% of parents had difficulty learning how to manage the complexity of the ketogenic diet and/or had limited cooking skills.

“Before you try someone on the ketogenic diet, we should evaluate the family’s educational level, their commitment, and their support systems so that we can help them overcome any barriers. It is important to have social workers as part of the ketogenic diet team to help with the process,” Dr. Kumar said. She reported having no financial disclosures.

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: More than one-third of children (43%) discontinued the ketogenic diet before the end of a 3-month trial period.

Data source: A prospective evaluation of 64 patients with intractable epilepsy and their families who were educated about the ketogenic diet at Dayton Children’s Hospital.

Disclosures: Dr. Kumar reported having no financial disclosures.

First visit for tuberous sclerosis complex comes months before diagnosis

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – Many patients who eventually receive a diagnosis of tuberous sclerosis complex present with related complaints for months, or even years, before their condition is recognized and correctly diagnosed, according to a retrospective study.

The study, presented at the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society, found that patients with tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC) first sought care for TSC-related conditions an average of 7 months before they were diagnosed with the condition. Younger patients received the correct diagnosis sooner than did older patients: Treatment for TSC-related conditions preceded the diagnosis for 3.4 months for those aged 4 years or younger, compared with 5.5 months for those aged 25-29 years, and 21 months for those aged 80 years or older.

Seizures and skin conditions were common initial diagnoses among TSC patients, with 27% of patients aged 0-4 years being diagnosed with seizures prior to receiving their TSC diagnosis. The likelihood of prediagnosis visits for seizures decreased to less than 6% for older age groups. Seizures remained common post-TSC diagnosis among younger patients, with 38% of patients aged 0-4 years having any seizure diagnosis, while the rate fell through the lifespan to zero for those aged 80 or older.

James Wheless, MD, and his associates examined claims and enrollment data records from 2,163 patients diagnosed with TSC between January 2000 and December 2011. In addition to the frequently-diagnosed seizures seen in many TSC patients, skin conditions were diagnosed in 16.3% of patients before their eventual TSC diagnosis.

Other early conditions associated with TSC, according to the study’s multivariable analysis, included bone cysts, anxiety, and ADHD. However, wrote Dr. Wheless, chief of the department of pediatric neurology at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center, Memphis, and his coauthors, “at any point in time, patients with seizures were 2.9 times more likely to receive a TSC diagnosis than patients without seizures.”

The study was drawn from U.S. health plan databases that included both commercial and Medicare Advantage enrollees, and included patients through the lifespan. The date of the first recorded TSC diagnosis was the index date, and patients had to have at least 12 months of prediagnosis health plan enrollment to be included, or 6 months for those aged 2 years or younger. Data were collected for all pre-index visits (some of which stretched back to 1993), and for visits in the 12 months after the index visit.

The proportion of female patients ranged from fewer than half for those under 15 years (0-4 years, 46%; 5-9 years, 43%; 10-14 years, 48%) to 64% for those aged 80 years or older (P less than .001).

Dr. Wheless and his coauthors noted that the claims data used for the analysis “may not adequately capture clinical characteristics such as disease severity,” and that some patient data may have been lost if patients were disenrolled for periods of time during the study period.

The findings of the poster may prompt clinicians to consider TSC as a diagnosis; though rare, occurring in 1-2 per 6,000 live births, it’s thought to be an underrecognized disease entity. “Understanding the initial diagnoses experienced by TSC patients may help lead to earlier diagnosis and treatment of TSC,” Dr. Wheless and his coauthors wrote.

Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum, and one is employed by Novartis.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

FROM AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Patients were seen an average of 6.9 months before they received their TSC diagnosis.

Data source: Retrospective review of claims and enrollment data from 2,163 patients with tuberous sclerosis.

Disclosures: Novartis funded the study. Four study authors are employed by Optum; one is employed by Novartis.

Physicians and EHR time

Clinical question: How much time do ambulatory-care physicians spend on electronic health records (EHRs)?

Background: There is growing concern about physicians’ increased time and effort allocated to the EHR and decreased clinical face time and meaningful interaction with patients. Prior studies have shown that increased physician EHR task load is associated with increased physician stress and dissatisfaction.

Setting: Ambulatory-care practices.

Synopsis: Fifty-seven physicians from 16 practices in four U.S. states participated and were observed for more than 430 office hours. Additionally, 21 physicians completed a self-reported after-hours diary. During office hours, physicians spent 49.2% of their total time on the EHR and desk work and only 27% on face time with patients. While in the exam room, physicians spent 52.9% of the time on direct clinical face time and 37% on the EHR and desk work. Self-reported diaries showed an additional 1-2 hours of follow-up work on the EHR. These observations might not be generalizable to other practices. No formal statistical comparisons by physicians, practice, or EHR characteristics were done.

Bottom line: Ambulatory-care physicians appear to spend more time with EHR tasks and desk work than clinical face time with patients.

Citation: Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion studies in 4 specialties [published online ahead of print Sept. 6, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 165(11):753-760.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: How much time do ambulatory-care physicians spend on electronic health records (EHRs)?

Background: There is growing concern about physicians’ increased time and effort allocated to the EHR and decreased clinical face time and meaningful interaction with patients. Prior studies have shown that increased physician EHR task load is associated with increased physician stress and dissatisfaction.

Setting: Ambulatory-care practices.

Synopsis: Fifty-seven physicians from 16 practices in four U.S. states participated and were observed for more than 430 office hours. Additionally, 21 physicians completed a self-reported after-hours diary. During office hours, physicians spent 49.2% of their total time on the EHR and desk work and only 27% on face time with patients. While in the exam room, physicians spent 52.9% of the time on direct clinical face time and 37% on the EHR and desk work. Self-reported diaries showed an additional 1-2 hours of follow-up work on the EHR. These observations might not be generalizable to other practices. No formal statistical comparisons by physicians, practice, or EHR characteristics were done.

Bottom line: Ambulatory-care physicians appear to spend more time with EHR tasks and desk work than clinical face time with patients.

Citation: Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion studies in 4 specialties [published online ahead of print Sept. 6, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 165(11):753-760.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Clinical question: How much time do ambulatory-care physicians spend on electronic health records (EHRs)?

Background: There is growing concern about physicians’ increased time and effort allocated to the EHR and decreased clinical face time and meaningful interaction with patients. Prior studies have shown that increased physician EHR task load is associated with increased physician stress and dissatisfaction.

Setting: Ambulatory-care practices.

Synopsis: Fifty-seven physicians from 16 practices in four U.S. states participated and were observed for more than 430 office hours. Additionally, 21 physicians completed a self-reported after-hours diary. During office hours, physicians spent 49.2% of their total time on the EHR and desk work and only 27% on face time with patients. While in the exam room, physicians spent 52.9% of the time on direct clinical face time and 37% on the EHR and desk work. Self-reported diaries showed an additional 1-2 hours of follow-up work on the EHR. These observations might not be generalizable to other practices. No formal statistical comparisons by physicians, practice, or EHR characteristics were done.

Bottom line: Ambulatory-care physicians appear to spend more time with EHR tasks and desk work than clinical face time with patients.

Citation: Sinsky C, Colligan L, Li L, et al. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice: a time and motion studies in 4 specialties [published online ahead of print Sept. 6, 2016]. Ann Intern Med. 165(11):753-760.

Dr. Briones is an assistant professor at the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine and medical director of the hospitalist service at the University of Miami Hospital.

Machine learning beats clinical prediction of temporal lobe epilepsy surgery outcomes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

HOUSTON – A machine learning interpretation of presurgical MRI studies did a better job of predicting which patients would have a successful outcome after anterior temporal lobectomy for temporal lobe epilepsy than did commonly-used clinical indicators in a prospective cohort study.

Xiaosong He, PhD, and his associates used two different machine learning classification methods to find two markers for thalamocortical connectedness that best predicted a good surgical outcome for temporal lobe epilepsy (TLE) in a small sample of patients. They presented their findings during a poster session of the annual meeting of the American Epilepsy Society.

After selecting a variety of possible predictors and building a model using resting state functional MRI (rsfMRI) data from 48 patients, the investigators then validated the prediction accuracies with rsfMRI data from 8 patients.

In predicting which TLE patients would have a good surgical outcome, models built with machine learning techniques using rsfMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%. By comparison, models using clinical predictors only had sensitivity of 66% to 83% and specificity of 29% to 33%.

Dr. He and his coauthors dichotomized the surgical outcome for 56 patients who underwent TLE surgery into good outcome (n = 35) for those achieving and Engel class I and poor outcome (n = 21, class II-IV) at 1 year post surgery. All patients had a 5-minute rsfMRI scan before surgery.

MRI has been helpful in elucidating the importance of thalamocortical network pathology in TLE. Dr. He and his associates had previously used rsfMRI to examine the strength of functional connectivity between thalamic regions and their corresponding cortical regions in patients with TLE. Analysis of rsfMRI data of “both the left and right TLE groups showed that compared to controls there was a pattern of decreased thalamocortical [functional connectivity] in multiple thalamic segments,” wrote Dr. He and his collaborators (Epilepsia. 2015;56[10]:1571-9).

For the validation cohort, the two measures of connectedness found most predictive of a good surgical outcome were degree centrality and eigenvector centrality. In the graph theory and network analysis used in mapping functional connectivity, centrality refers to how highly connected one node, or data point, is to other data.

In the present study, the investigators used the Automated Anatomical Labeling cortical parcellation map to identify 45 cortical regions of interest per hemisphere, for a total of 90 cortical regions. They built a matrix with five topological parameters (global efficiency, global clustering coefficient, degree centrality, betweenness centrality, and eigenvector centrality) and the 90 cortical regions, yielding 272 variables. When nine commonly-used clinical predictors of surgical outcome (age, gender, handedness, laterality of TLE, epilepsy onset age and duration, seizure focality, interictal-spike type, and the presence of hippocampal sclerosis) were included, the model was made up of 281 variables.

The investigators used two different machine learning classification methods, called support vector machine and random forest, to build models that included various combinations of the 281 variables based on data from the initial 48 patients. The models were then tested with data from the remaining 8 patients.

Of the 35 patients with a good outcome, 18 had a left-sided epileptogenic temporal lobe; for the 21 patients with a poor outcome, the left temporal lobe was epileptogenic in 8. The mean age was similar for both groups: 41.25 years in those with good outcome, and 38.58 years in those with a poor outcome. Age at epilepsy onset also was similar, with each group having had epilepsy for about 17 years at the time of surgery. A total of 15 of the 20 patients with good outcome had seizure focality, compared with 10 of the 11 with poor outcome. Of those with a good outcome, 29 had an ipsilateral interactive spike, while 15 of those with poor outcomes had an ipsilateral interactive spike.

Since the random forest model best predicted surgical outcomes in the small sample size tested, the investigators plan to further fine-tune the random forest parameters to increase the robustness of their model.

Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

[email protected]

On Twitter @karioakes

AT AES 2016

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Models built with machine learning techniques using resting state fMRI functional connectivity values had sensitivity ranging from 80% to 89% and specificity ranging from 52% to 57%.

Data source: A prospective study of 56 patients with temporal lobe epilepsy.

Disclosures: Dr. He reported no conflicts of interest.

USPSTF nixes routine genital herpes screening

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

It’s disappointing that the performance of screening tests hasn’t improved during the 10 years since the last USPSTF Recommendation Statement.

These findings should serve as a call to action for federal health agencies and their partners in industry to prioritize the development of better tests and stem the continuing epidemic of genital herpes.

Another important step would be to work vigorously to reduce the pervasive stigma of this disease, which also hinders management and control efforts. The public continues to harbor misperceptions about the severity of genital herpes and the availability of effective treatment, which adds to disproportionate stigmatization of those infected.

Edward W. Hook III, MD, is in the department of microbiology at the University of Alabama at Birmingham. He reported ties to Hologic, Roche Molecular, Becton Dickinson, and Cepheid. Dr. Hook made these remarks in an editorial accompanying the USPSTF Recommendation Statement (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2493-4).

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

Asymptomatic adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms of this approach outweigh the benefits, according to an updated US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) Recommendation Statement published online in JAMA.

The USPSTF last addressed screening for herpes simplex virus (HSV) in a 2005 Recommendation Statement, which advised against routine screening of asymptomatic patients at that time. “A small number” of clinical trials examined the issue since then, so the group commissioned a review of the literature through October 2016 to incorporate any new findings into the update, said Kirsten Bibbins-Domingo, MD, PhD, chair of the USPSTF and lead author of the update, and her associates.

Dr. Feltner and her colleagues concluded that current serologic screening tests produce a high rate of false-positive results – as much as 50% – and that those in turn lead to psychosocial harms such as distress and disruption of personal relationships, as well as increased costs and potential medical harm associated with confirmatory testing and unnecessary treatment.

Given the false-positive rates of the most widely used screening tests and the 15% prevalence of genital herpes in the general population, “screening 10,000 persons would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.” Moreover, confirmatory testing is offered only at a single research laboratory, said Dr. Bibbins-Domingo, professor of medicine at the University of California, San Francisco, and her associates on the Task Force.

Based on these findings and given the natural history and epidemiology of genital herpes, they characterized the potential benefits of routine screening as “no greater than small,” and the harms as “at least moderate” (JAMA. 2016 Dec 20;316[23]:2525-30. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.16776).

The American Academy of Family Physicians, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology, and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention also recommend against routine HSV screening of adolescents and adults, including pregnant women, the investigators noted.

The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

FROM JAMA

Key clinical point: Asymptomatic adults and adolescents should not undergo routine serologic screening for genital herpes because the harms outweigh the benefits, according to an updated USPSTF recommendation statement.

Major finding: Given the nearly 50% false-positive rate of current screening tests, screening 10,000 members of the general population would result in approximately 1,485 true-positive and 1,445 false-positive results.

Data source: A systematic review of 17 studies involving 9,736 participants regarding the accuracy, benefits, and harms of HSV screening.

Disclosures: The USPSTF is an independent, voluntary group that evaluates preventive health care services and is funded by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality by mandate of the U.S. Congress. The authors’ financial disclosures are available at www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org.

Pritelivir beats valacyclovir at suppressing genital HSV-2 infection

A 1-month course of pritelivir reduced genital HSV-2 shedding more than valacyclovir did in a small phase II clinical trial, according to a report published online in JAMA.

Previous phase I studies suggested that oral daily pritelivir was safe and tolerable in the patient population under evaluation (healthy adults with four to nine annual genital HSV-2 recurrences). Researchers performed this randomized, double-blind, crossover trial to assess the drug’s efficacy in 91 adults (mean age 48 years) who had frequent recurrences of genital symptoms and lesions. Study participants at four U.S. clinical research centers received pritelivir or valacyclovir for 28 days, followed by a washout period, then a 28-day course of the other drug, said lead investigator Anna Wald, MD, of the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and her associates.

The primary endpoint – the number of swabs that tested positive for HSV-2 relative to the total number of swabs collected – was 2.4% during pritelivir treatment and 5.3% during valacyclovir treatment, a significant difference (relative risk, 0.42). Genital lesions were reported on 1.9% of days during pritelivir treatment, compared with 3.9% of days during valacyclovir treatment (RR, 0.40). In addition, the frequency of subclinical shedding also was significantly lower with pritelivir (1.8% vs. 4.1%), while the percentage of episodes resolving within 24 hours was significantly higher (87% vs. 69%).

The rate and severity of adverse events were similar between the two study groups. There were no serious adverse events or deaths. Compared with valacyclovir, pritelivir was associated with more statistically significant but clinically irrelevant changes in lymphocyte counts and creatinine levels. One patient in each study group developed mild allergic reactions thought to be possibly related to treatment, which resolved upon discontinuation of the study drugs.

AiCuris, maker of pritelivir, supported the study. Dr. Wald reported ties to AiCuris, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Gilead, Vical, Genocea, and Admedus; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

A 1-month course of pritelivir reduced genital HSV-2 shedding more than valacyclovir did in a small phase II clinical trial, according to a report published online in JAMA.

Previous phase I studies suggested that oral daily pritelivir was safe and tolerable in the patient population under evaluation (healthy adults with four to nine annual genital HSV-2 recurrences). Researchers performed this randomized, double-blind, crossover trial to assess the drug’s efficacy in 91 adults (mean age 48 years) who had frequent recurrences of genital symptoms and lesions. Study participants at four U.S. clinical research centers received pritelivir or valacyclovir for 28 days, followed by a washout period, then a 28-day course of the other drug, said lead investigator Anna Wald, MD, of the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and her associates.

The primary endpoint – the number of swabs that tested positive for HSV-2 relative to the total number of swabs collected – was 2.4% during pritelivir treatment and 5.3% during valacyclovir treatment, a significant difference (relative risk, 0.42). Genital lesions were reported on 1.9% of days during pritelivir treatment, compared with 3.9% of days during valacyclovir treatment (RR, 0.40). In addition, the frequency of subclinical shedding also was significantly lower with pritelivir (1.8% vs. 4.1%), while the percentage of episodes resolving within 24 hours was significantly higher (87% vs. 69%).

The rate and severity of adverse events were similar between the two study groups. There were no serious adverse events or deaths. Compared with valacyclovir, pritelivir was associated with more statistically significant but clinically irrelevant changes in lymphocyte counts and creatinine levels. One patient in each study group developed mild allergic reactions thought to be possibly related to treatment, which resolved upon discontinuation of the study drugs.

AiCuris, maker of pritelivir, supported the study. Dr. Wald reported ties to AiCuris, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Gilead, Vical, Genocea, and Admedus; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

A 1-month course of pritelivir reduced genital HSV-2 shedding more than valacyclovir did in a small phase II clinical trial, according to a report published online in JAMA.

Previous phase I studies suggested that oral daily pritelivir was safe and tolerable in the patient population under evaluation (healthy adults with four to nine annual genital HSV-2 recurrences). Researchers performed this randomized, double-blind, crossover trial to assess the drug’s efficacy in 91 adults (mean age 48 years) who had frequent recurrences of genital symptoms and lesions. Study participants at four U.S. clinical research centers received pritelivir or valacyclovir for 28 days, followed by a washout period, then a 28-day course of the other drug, said lead investigator Anna Wald, MD, of the University of Washington and the Fred Hutchinson Cancer Research Center, Seattle, and her associates.

The primary endpoint – the number of swabs that tested positive for HSV-2 relative to the total number of swabs collected – was 2.4% during pritelivir treatment and 5.3% during valacyclovir treatment, a significant difference (relative risk, 0.42). Genital lesions were reported on 1.9% of days during pritelivir treatment, compared with 3.9% of days during valacyclovir treatment (RR, 0.40). In addition, the frequency of subclinical shedding also was significantly lower with pritelivir (1.8% vs. 4.1%), while the percentage of episodes resolving within 24 hours was significantly higher (87% vs. 69%).

The rate and severity of adverse events were similar between the two study groups. There were no serious adverse events or deaths. Compared with valacyclovir, pritelivir was associated with more statistically significant but clinically irrelevant changes in lymphocyte counts and creatinine levels. One patient in each study group developed mild allergic reactions thought to be possibly related to treatment, which resolved upon discontinuation of the study drugs.

AiCuris, maker of pritelivir, supported the study. Dr. Wald reported ties to AiCuris, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Gilead, Vical, Genocea, and Admedus; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

[email protected]

On Twitter @idpractitioner

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among genital swabs, 2.4% tested positive for HSV-2 during pritelivir treatment and 5.3% did during valacyclovir treatment (relative risk, 0.42).

Data source: A randomized, double-blind, crossover trial involving 91 adults with frequently recurring genital HSV-2.

Disclosures: AiCuris, maker of pritelivir, supported the study. Dr. Wald reported ties to AiCuris, Amgen, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Gilead, Vical, Genocea, and Admedus; her associates reported ties to numerous industry sources.

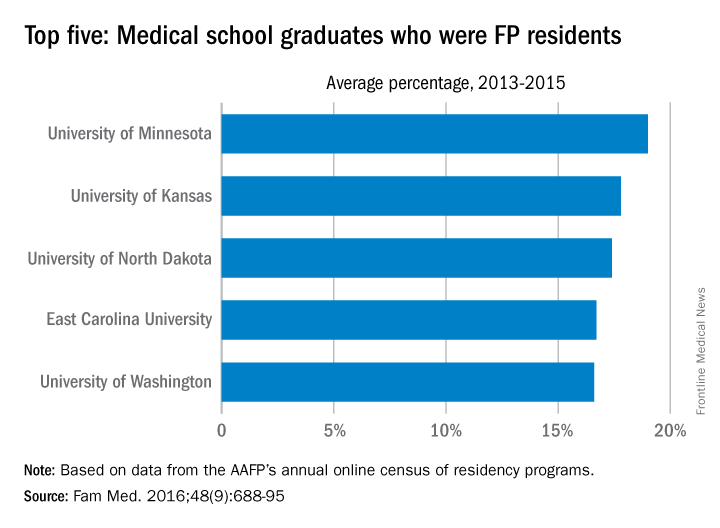

University of Minnesota producing more than its fair share of FPs

, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Data from the AAFP’s annual survey of family medicine residency programs showed that, over a 3-year period from 2013 to 2015, 19% of the University of Minnesota’s medical school graduates entered a family medicine residency, reported Stanley M. Kozakowski, MD, and his associates (Fam Med. 2016;48[9]:688-95).

In 2015, the University of Minnesota produced 42 graduates who became FP residents, the highest number for any of the 134 U.S. medical schools granting MD degrees in family medicine. Among schools granting DO degrees, however, the leader for 2015 was Des Moines University, which had 68 students (32.7%) enter family medicine, the investigators said. Of the 2,463 individuals who were first-year family medicine residents in 2015, 1,640 graduated from MD-granting schools and 823 graduated from DO-granting schools.

, according to the American Academy of Family Physicians.

Data from the AAFP’s annual survey of family medicine residency programs showed that, over a 3-year period from 2013 to 2015, 19% of the University of Minnesota’s medical school graduates entered a family medicine residency, reported Stanley M. Kozakowski, MD, and his associates (Fam Med. 2016;48[9]:688-95).