User login

Dose intensification gets more mileage out of adjuvant chemo

SAN ANTONIO – Increasing the dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer by spacing cycles more closely or by giving drugs sequentially instead of concurrently improves outcomes, confirms a meta-analysis conducted by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG).

Results showed that depending on which specific strategy was used, women were 13%-18% less likely to experience recurrence and 11%-18% less likely to die from breast cancer if they were given dose-intensified chemotherapy instead of standard chemotherapy, he reported in a press briefing and a session at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Shortening the interval between cycles and sequential administration of anthracycline and taxane chemotherapy reduces both recurrence and death from breast cancer,” Mr. Gray summarized. “The reductions are about 15%. They were seen in both estrogen receptor [ER]–positive and ER-negative disease and did not differ significantly by any other tumor or patient characteristics.”

“The beauty of this is these are the exact same drugs and, in many cases, similar doses. It’s just the schedule that changes,” commented press briefing moderator Virginia Kaklamani, MD, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and a leader of the Breast Cancer Program at the UT Health San Antonio Cancer Center. “We used to give chemotherapy over 6 months, and with this approach, we can give it over 4 months, so the patients prefer it. The toxicity, with the growth factors for support, can be less. So everybody wins here.”

Study details

“We know that adjuvant chemotherapy can really help reduce recurrence and prevent breast cancer death. It reduces breast cancer death by about a third,” Mr. Gray noted, giving some background to the analysis. “We are still looking at ways to improve that even further. One of the approaches, which is based on cytokinetic modeling, is to try and increase the dose intensity of the chemotherapy.”

For the meta-analysis, the investigators identified trials that achieved dose intensification by reducing the interval between treatment cycles (a dose-dense approach) and/or by giving drugs sequentially rather than concurrently (allowing delivery of higher doses of each drug).

In all, seven trials, which included 10,004 women in total, tested chemotherapy given every 2 weeks (dose-dense chemotherapy) versus the same chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results showed that the former approach netted significantly lower risks of recurrence (rate ratio [RR], 0.83; P = .00004) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.86; P = .004), Mr. Gray reported. Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.3% and 2.8%, respectively. Findings were similar after adding five more trials, with another 5,508 women, that had some differences in chemotherapy treatments between arms.

Six trials, which included 11,028 women in total, tested sequential chemotherapy every 3 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy every 3 weeks. Results showed similarly that the former strategy yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.87; P = .0006) and breast cancer death (RR, 0.89; P = .03). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.2% and 2.1%, respectively.

Another six trials, which included a total of 6,532 women, tested sequential chemotherapy given every 2 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results here showed once again that the former yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.82; P = .0001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.82; P = .001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.5% and 3.9%, respectively.

Finally, a pooled analysis of all trials showed that dose intensification reduced the risk of recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .00001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.6% and 2.7%, respectively.

“That 13% reduction in breast cancer mortality may seem relatively modest, but given that taxane and anthracycline on a standard schedule reduces your chance of breast cancer death by a third, if you then reduce that by another 15%, then you have got almost 50% of breast cancer deaths by dose-dense taxane and anthracycline chemotherapy,” Mr. Gray pointed out. “So these little step-by-step improvements, it’s really important to identify them, and you get incremental gains which result in breast cancer deaths being about half of what they were 25 or 30 years ago.”

The proportional reduction in risk was similar whether tumors were ER positive or negative, but additional follow-up, especially for the positive tumors, will be important. “We do need longer follow-up in these trials, and sadly, many of the funding bodies are not providing funding for long-term follow-up,” he commented. “This is really valuable information, and we should be following these women up further, out to 20 years, given the long natural history of breast cancer.”

In terms of safety, the dose-intensification strategies were actually associated with lower risks of death without recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .02) and all-cause mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Findings were similar when analyses focused on the first year of treatment.

Tolerability and toxicities of dose-intense regimens relative to standard regimens were not evaluated by the meta-analysis because these outcomes were reported differently across trials, according to Mr. Gray. However, the investigators did perform a systematic review of health-related quality of life studies that will be part of the final manuscript.

“We found surprisingly little extra toxicity” with the dose intensification, he reported. “It’s not very much considering the extra benefits we are getting. And when you know you are getting more benefit, it makes it easy to tolerate a drug.”

“In the U.S., people have moved toward the accelerated chemotherapy much more than they have in Europe. I think people have the mindset, ‘Well, we’ve always done it this way,’ ” Mr. Gray concluded. “This evidence being so clear and definite will help change that mindset. I wouldn’t be surprised if practice in the U.K. and many other parts of Europe doesn’t switch as a result of these very definite findings.”

SAN ANTONIO – Increasing the dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer by spacing cycles more closely or by giving drugs sequentially instead of concurrently improves outcomes, confirms a meta-analysis conducted by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG).

Results showed that depending on which specific strategy was used, women were 13%-18% less likely to experience recurrence and 11%-18% less likely to die from breast cancer if they were given dose-intensified chemotherapy instead of standard chemotherapy, he reported in a press briefing and a session at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Shortening the interval between cycles and sequential administration of anthracycline and taxane chemotherapy reduces both recurrence and death from breast cancer,” Mr. Gray summarized. “The reductions are about 15%. They were seen in both estrogen receptor [ER]–positive and ER-negative disease and did not differ significantly by any other tumor or patient characteristics.”

“The beauty of this is these are the exact same drugs and, in many cases, similar doses. It’s just the schedule that changes,” commented press briefing moderator Virginia Kaklamani, MD, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and a leader of the Breast Cancer Program at the UT Health San Antonio Cancer Center. “We used to give chemotherapy over 6 months, and with this approach, we can give it over 4 months, so the patients prefer it. The toxicity, with the growth factors for support, can be less. So everybody wins here.”

Study details

“We know that adjuvant chemotherapy can really help reduce recurrence and prevent breast cancer death. It reduces breast cancer death by about a third,” Mr. Gray noted, giving some background to the analysis. “We are still looking at ways to improve that even further. One of the approaches, which is based on cytokinetic modeling, is to try and increase the dose intensity of the chemotherapy.”

For the meta-analysis, the investigators identified trials that achieved dose intensification by reducing the interval between treatment cycles (a dose-dense approach) and/or by giving drugs sequentially rather than concurrently (allowing delivery of higher doses of each drug).

In all, seven trials, which included 10,004 women in total, tested chemotherapy given every 2 weeks (dose-dense chemotherapy) versus the same chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results showed that the former approach netted significantly lower risks of recurrence (rate ratio [RR], 0.83; P = .00004) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.86; P = .004), Mr. Gray reported. Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.3% and 2.8%, respectively. Findings were similar after adding five more trials, with another 5,508 women, that had some differences in chemotherapy treatments between arms.

Six trials, which included 11,028 women in total, tested sequential chemotherapy every 3 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy every 3 weeks. Results showed similarly that the former strategy yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.87; P = .0006) and breast cancer death (RR, 0.89; P = .03). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.2% and 2.1%, respectively.

Another six trials, which included a total of 6,532 women, tested sequential chemotherapy given every 2 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results here showed once again that the former yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.82; P = .0001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.82; P = .001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.5% and 3.9%, respectively.

Finally, a pooled analysis of all trials showed that dose intensification reduced the risk of recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .00001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.6% and 2.7%, respectively.

“That 13% reduction in breast cancer mortality may seem relatively modest, but given that taxane and anthracycline on a standard schedule reduces your chance of breast cancer death by a third, if you then reduce that by another 15%, then you have got almost 50% of breast cancer deaths by dose-dense taxane and anthracycline chemotherapy,” Mr. Gray pointed out. “So these little step-by-step improvements, it’s really important to identify them, and you get incremental gains which result in breast cancer deaths being about half of what they were 25 or 30 years ago.”

The proportional reduction in risk was similar whether tumors were ER positive or negative, but additional follow-up, especially for the positive tumors, will be important. “We do need longer follow-up in these trials, and sadly, many of the funding bodies are not providing funding for long-term follow-up,” he commented. “This is really valuable information, and we should be following these women up further, out to 20 years, given the long natural history of breast cancer.”

In terms of safety, the dose-intensification strategies were actually associated with lower risks of death without recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .02) and all-cause mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Findings were similar when analyses focused on the first year of treatment.

Tolerability and toxicities of dose-intense regimens relative to standard regimens were not evaluated by the meta-analysis because these outcomes were reported differently across trials, according to Mr. Gray. However, the investigators did perform a systematic review of health-related quality of life studies that will be part of the final manuscript.

“We found surprisingly little extra toxicity” with the dose intensification, he reported. “It’s not very much considering the extra benefits we are getting. And when you know you are getting more benefit, it makes it easy to tolerate a drug.”

“In the U.S., people have moved toward the accelerated chemotherapy much more than they have in Europe. I think people have the mindset, ‘Well, we’ve always done it this way,’ ” Mr. Gray concluded. “This evidence being so clear and definite will help change that mindset. I wouldn’t be surprised if practice in the U.K. and many other parts of Europe doesn’t switch as a result of these very definite findings.”

SAN ANTONIO – Increasing the dose intensity of adjuvant chemotherapy for breast cancer by spacing cycles more closely or by giving drugs sequentially instead of concurrently improves outcomes, confirms a meta-analysis conducted by the Early Breast Cancer Trialists’ Collaborative Group (EBCTCG).

Results showed that depending on which specific strategy was used, women were 13%-18% less likely to experience recurrence and 11%-18% less likely to die from breast cancer if they were given dose-intensified chemotherapy instead of standard chemotherapy, he reported in a press briefing and a session at the San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium.

“Shortening the interval between cycles and sequential administration of anthracycline and taxane chemotherapy reduces both recurrence and death from breast cancer,” Mr. Gray summarized. “The reductions are about 15%. They were seen in both estrogen receptor [ER]–positive and ER-negative disease and did not differ significantly by any other tumor or patient characteristics.”

“The beauty of this is these are the exact same drugs and, in many cases, similar doses. It’s just the schedule that changes,” commented press briefing moderator Virginia Kaklamani, MD, a professor of medicine in the division of hematology/oncology at the University of Texas Health Science Center San Antonio and a leader of the Breast Cancer Program at the UT Health San Antonio Cancer Center. “We used to give chemotherapy over 6 months, and with this approach, we can give it over 4 months, so the patients prefer it. The toxicity, with the growth factors for support, can be less. So everybody wins here.”

Study details

“We know that adjuvant chemotherapy can really help reduce recurrence and prevent breast cancer death. It reduces breast cancer death by about a third,” Mr. Gray noted, giving some background to the analysis. “We are still looking at ways to improve that even further. One of the approaches, which is based on cytokinetic modeling, is to try and increase the dose intensity of the chemotherapy.”

For the meta-analysis, the investigators identified trials that achieved dose intensification by reducing the interval between treatment cycles (a dose-dense approach) and/or by giving drugs sequentially rather than concurrently (allowing delivery of higher doses of each drug).

In all, seven trials, which included 10,004 women in total, tested chemotherapy given every 2 weeks (dose-dense chemotherapy) versus the same chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results showed that the former approach netted significantly lower risks of recurrence (rate ratio [RR], 0.83; P = .00004) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.86; P = .004), Mr. Gray reported. Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.3% and 2.8%, respectively. Findings were similar after adding five more trials, with another 5,508 women, that had some differences in chemotherapy treatments between arms.

Six trials, which included 11,028 women in total, tested sequential chemotherapy every 3 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy every 3 weeks. Results showed similarly that the former strategy yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.87; P = .0006) and breast cancer death (RR, 0.89; P = .03). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.2% and 2.1%, respectively.

Another six trials, which included a total of 6,532 women, tested sequential chemotherapy given every 2 weeks versus concurrent chemotherapy given every 3 weeks. Results here showed once again that the former yielded lower risks of recurrence (RR, 0.82; P = .0001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.82; P = .001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 4.5% and 3.9%, respectively.

Finally, a pooled analysis of all trials showed that dose intensification reduced the risk of recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .00001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Absolute gains at 10 years were 3.6% and 2.7%, respectively.

“That 13% reduction in breast cancer mortality may seem relatively modest, but given that taxane and anthracycline on a standard schedule reduces your chance of breast cancer death by a third, if you then reduce that by another 15%, then you have got almost 50% of breast cancer deaths by dose-dense taxane and anthracycline chemotherapy,” Mr. Gray pointed out. “So these little step-by-step improvements, it’s really important to identify them, and you get incremental gains which result in breast cancer deaths being about half of what they were 25 or 30 years ago.”

The proportional reduction in risk was similar whether tumors were ER positive or negative, but additional follow-up, especially for the positive tumors, will be important. “We do need longer follow-up in these trials, and sadly, many of the funding bodies are not providing funding for long-term follow-up,” he commented. “This is really valuable information, and we should be following these women up further, out to 20 years, given the long natural history of breast cancer.”

In terms of safety, the dose-intensification strategies were actually associated with lower risks of death without recurrence (RR, 0.85; P less than .02) and all-cause mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001). Findings were similar when analyses focused on the first year of treatment.

Tolerability and toxicities of dose-intense regimens relative to standard regimens were not evaluated by the meta-analysis because these outcomes were reported differently across trials, according to Mr. Gray. However, the investigators did perform a systematic review of health-related quality of life studies that will be part of the final manuscript.

“We found surprisingly little extra toxicity” with the dose intensification, he reported. “It’s not very much considering the extra benefits we are getting. And when you know you are getting more benefit, it makes it easy to tolerate a drug.”

“In the U.S., people have moved toward the accelerated chemotherapy much more than they have in Europe. I think people have the mindset, ‘Well, we’ve always done it this way,’ ” Mr. Gray concluded. “This evidence being so clear and definite will help change that mindset. I wouldn’t be surprised if practice in the U.K. and many other parts of Europe doesn’t switch as a result of these very definite findings.”

REPORTING FROM SABCS 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Compared with standard chemotherapy, dose-intense chemotherapy using various strategies reduced the risk of recurrence (rate ratio, 0.85; P less than .00001) and breast cancer mortality (RR, 0.87; P less than .00001).

Data source: A meta-analysis of individual patient data from 25 randomized trials among 34,122 women with early-stage breast cancer.

Disclosures: Mr. Gray disclosed that he had no relevant conflicts of interest.

Reducing the Stigma of HIV Testing With Online Support

Adolescents are one of the highest risk groups for HIV, but they often don’t want to talk about it. They also don’t want to get tested—of 40% of high school students who had had intercourse, only 10% had been tested, according to a CDC study.

Are online forums the solution? They offer anonymity along with information, and many adolescents—if not most—are used to getting information from social media. Researchers from University of California in Davis, say there’s a real need for a reliable source of advice on the subject for that audience. Most online forums for adolescent message boards and websites revolve around pregnancy and birth control rather than STDs.

The researchers noted that higher levels of stigma surrounding HIV correlate with lower levels of HIV testing. Even the testing is stigmatized, because many people feel just getting the test creates the impression that they are promiscuous, for instance. They also fear what the test may tell them and that it might be used against them in employment or health insurance.

The researchers analyzed 201 threads and 319 posts. Among 7 forums, 2 (POZ, MedHelp) were monitored by counselors, and 4 (DailyStrength, eHealth Forum, HealingWell, and HealthBoards) were monitored by members. One (The Body) was monitored by counselors and members.

In 13 threads, users displayed a “self-stigmatizing attitude” toward HIV testing, mainly because of the fear of being diagnosed. Others feared losing employment or having relationships affected. Notably, no adolescents asked about HIV testing in the forums targeted at their age groups. It is important to increase the visibility of HIV-related resources in adolescents’ forums, the researchers say; the lack of available information online may “perpetuate the taboo among this population by conveying a deeper stigma toward HIV.”

The study showed that the level of stigmatization differed significantly based on who monitored the session: The threads maintained by members had fewer stigmatized posts. The researchers suggest that if health care professionals get more involved by collaborating with forums to provide more content and framing HIV testing as a regular preventive checkup, they may reduce the stigma. Health care professionals also may be able to identify those who suspect they have HIV and encourage them to get tested. Health care professionals also can initiate threads that invite open discussion of HIV-related topics in sexual education forums devoted to adolescents. The researchers say breaking the online silence will lead more people to timely testing.

Source:

Ho CL, Pan W, Taylor LD. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017;55(12):34-43.

doi: 10.3928/02793695-20170905-01.

Adolescents are one of the highest risk groups for HIV, but they often don’t want to talk about it. They also don’t want to get tested—of 40% of high school students who had had intercourse, only 10% had been tested, according to a CDC study.

Are online forums the solution? They offer anonymity along with information, and many adolescents—if not most—are used to getting information from social media. Researchers from University of California in Davis, say there’s a real need for a reliable source of advice on the subject for that audience. Most online forums for adolescent message boards and websites revolve around pregnancy and birth control rather than STDs.

The researchers noted that higher levels of stigma surrounding HIV correlate with lower levels of HIV testing. Even the testing is stigmatized, because many people feel just getting the test creates the impression that they are promiscuous, for instance. They also fear what the test may tell them and that it might be used against them in employment or health insurance.

The researchers analyzed 201 threads and 319 posts. Among 7 forums, 2 (POZ, MedHelp) were monitored by counselors, and 4 (DailyStrength, eHealth Forum, HealingWell, and HealthBoards) were monitored by members. One (The Body) was monitored by counselors and members.

In 13 threads, users displayed a “self-stigmatizing attitude” toward HIV testing, mainly because of the fear of being diagnosed. Others feared losing employment or having relationships affected. Notably, no adolescents asked about HIV testing in the forums targeted at their age groups. It is important to increase the visibility of HIV-related resources in adolescents’ forums, the researchers say; the lack of available information online may “perpetuate the taboo among this population by conveying a deeper stigma toward HIV.”

The study showed that the level of stigmatization differed significantly based on who monitored the session: The threads maintained by members had fewer stigmatized posts. The researchers suggest that if health care professionals get more involved by collaborating with forums to provide more content and framing HIV testing as a regular preventive checkup, they may reduce the stigma. Health care professionals also may be able to identify those who suspect they have HIV and encourage them to get tested. Health care professionals also can initiate threads that invite open discussion of HIV-related topics in sexual education forums devoted to adolescents. The researchers say breaking the online silence will lead more people to timely testing.

Source:

Ho CL, Pan W, Taylor LD. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017;55(12):34-43.

doi: 10.3928/02793695-20170905-01.

Adolescents are one of the highest risk groups for HIV, but they often don’t want to talk about it. They also don’t want to get tested—of 40% of high school students who had had intercourse, only 10% had been tested, according to a CDC study.

Are online forums the solution? They offer anonymity along with information, and many adolescents—if not most—are used to getting information from social media. Researchers from University of California in Davis, say there’s a real need for a reliable source of advice on the subject for that audience. Most online forums for adolescent message boards and websites revolve around pregnancy and birth control rather than STDs.

The researchers noted that higher levels of stigma surrounding HIV correlate with lower levels of HIV testing. Even the testing is stigmatized, because many people feel just getting the test creates the impression that they are promiscuous, for instance. They also fear what the test may tell them and that it might be used against them in employment or health insurance.

The researchers analyzed 201 threads and 319 posts. Among 7 forums, 2 (POZ, MedHelp) were monitored by counselors, and 4 (DailyStrength, eHealth Forum, HealingWell, and HealthBoards) were monitored by members. One (The Body) was monitored by counselors and members.

In 13 threads, users displayed a “self-stigmatizing attitude” toward HIV testing, mainly because of the fear of being diagnosed. Others feared losing employment or having relationships affected. Notably, no adolescents asked about HIV testing in the forums targeted at their age groups. It is important to increase the visibility of HIV-related resources in adolescents’ forums, the researchers say; the lack of available information online may “perpetuate the taboo among this population by conveying a deeper stigma toward HIV.”

The study showed that the level of stigmatization differed significantly based on who monitored the session: The threads maintained by members had fewer stigmatized posts. The researchers suggest that if health care professionals get more involved by collaborating with forums to provide more content and framing HIV testing as a regular preventive checkup, they may reduce the stigma. Health care professionals also may be able to identify those who suspect they have HIV and encourage them to get tested. Health care professionals also can initiate threads that invite open discussion of HIV-related topics in sexual education forums devoted to adolescents. The researchers say breaking the online silence will lead more people to timely testing.

Source:

Ho CL, Pan W, Taylor LD. J Psychosoc Nurs Ment Health Serv. 2017;55(12):34-43.

doi: 10.3928/02793695-20170905-01.

Method may improve HSC mobilization, engraftment

New research suggests a 2-drug combination might improve hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) for donors and recipients.

Researchers found that a single dose of the drugs provides HSC mobilization that rivals 5-day treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).

And the combination mobilizes HSCs that have higher engraftment efficiency than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

Jonathan Hoggatt, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell.

“Our new method of harvesting stem cells requires only a single injection and mobilizes the cells needed in 15 minutes,” Dr Hoggatt said. “So in the time it takes to boil an egg, we are able to acquire the number of stem cells produced by the current standard 5-day protocol. This means less pain, time off work, and lifestyle disruption for the donor, more convenience for the clinical staff, and more predictability for the harvesting procedure.”

Dr Hoggatt and his colleagues have investigated ways to enhance HSC donation for several years. In a previous study, the researchers found that a CXCR2 agonist called GRO-beta induced rapid movement of HSCs from the marrow into the blood in animal models.

Initial experiments in the current study revealed that GRO-beta injections were safe and well tolerated in human volunteers but had only a modest effect in mobilizing HSCs. Therefore, the team tried combining GRO-beta with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (plerixafor).

The researchers found that simultaneous administration of both drugs rapidly (within 15 minutes) produced a quantity of HSCs equal to that provided by the 5-day G-CSF protocol.

When transplanted in mice, the HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta prompted faster reconstitution of bone marrow and recovery of immune cell populations than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

The HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta showed patterns of gene expression similar to those of fetal HSCs.

“These highly engraftable hematopoietic stem cells produced by our new strategy are essentially the A+ students of bone marrow stem cells,” Dr Hoggatt said. “Finding that they express genes similar to those of fetal liver HSCs . . . suggests that they will be very good at moving into an empty bone marrow space and rapidly dividing to fill the marrow and produce blood. Now, we need to test the combination in a clinical trial to confirm its safety and effectiveness in humans.” ![]()

New research suggests a 2-drug combination might improve hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) for donors and recipients.

Researchers found that a single dose of the drugs provides HSC mobilization that rivals 5-day treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).

And the combination mobilizes HSCs that have higher engraftment efficiency than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

Jonathan Hoggatt, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell.

“Our new method of harvesting stem cells requires only a single injection and mobilizes the cells needed in 15 minutes,” Dr Hoggatt said. “So in the time it takes to boil an egg, we are able to acquire the number of stem cells produced by the current standard 5-day protocol. This means less pain, time off work, and lifestyle disruption for the donor, more convenience for the clinical staff, and more predictability for the harvesting procedure.”

Dr Hoggatt and his colleagues have investigated ways to enhance HSC donation for several years. In a previous study, the researchers found that a CXCR2 agonist called GRO-beta induced rapid movement of HSCs from the marrow into the blood in animal models.

Initial experiments in the current study revealed that GRO-beta injections were safe and well tolerated in human volunteers but had only a modest effect in mobilizing HSCs. Therefore, the team tried combining GRO-beta with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (plerixafor).

The researchers found that simultaneous administration of both drugs rapidly (within 15 minutes) produced a quantity of HSCs equal to that provided by the 5-day G-CSF protocol.

When transplanted in mice, the HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta prompted faster reconstitution of bone marrow and recovery of immune cell populations than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

The HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta showed patterns of gene expression similar to those of fetal HSCs.

“These highly engraftable hematopoietic stem cells produced by our new strategy are essentially the A+ students of bone marrow stem cells,” Dr Hoggatt said. “Finding that they express genes similar to those of fetal liver HSCs . . . suggests that they will be very good at moving into an empty bone marrow space and rapidly dividing to fill the marrow and produce blood. Now, we need to test the combination in a clinical trial to confirm its safety and effectiveness in humans.” ![]()

New research suggests a 2-drug combination might improve hematopoietic stem cell transplant (HSCT) for donors and recipients.

Researchers found that a single dose of the drugs provides HSC mobilization that rivals 5-day treatment with granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF).

And the combination mobilizes HSCs that have higher engraftment efficiency than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

Jonathan Hoggatt, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, and his colleagues reported these findings in Cell.

“Our new method of harvesting stem cells requires only a single injection and mobilizes the cells needed in 15 minutes,” Dr Hoggatt said. “So in the time it takes to boil an egg, we are able to acquire the number of stem cells produced by the current standard 5-day protocol. This means less pain, time off work, and lifestyle disruption for the donor, more convenience for the clinical staff, and more predictability for the harvesting procedure.”

Dr Hoggatt and his colleagues have investigated ways to enhance HSC donation for several years. In a previous study, the researchers found that a CXCR2 agonist called GRO-beta induced rapid movement of HSCs from the marrow into the blood in animal models.

Initial experiments in the current study revealed that GRO-beta injections were safe and well tolerated in human volunteers but had only a modest effect in mobilizing HSCs. Therefore, the team tried combining GRO-beta with the CXCR4 antagonist AMD3100 (plerixafor).

The researchers found that simultaneous administration of both drugs rapidly (within 15 minutes) produced a quantity of HSCs equal to that provided by the 5-day G-CSF protocol.

When transplanted in mice, the HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta prompted faster reconstitution of bone marrow and recovery of immune cell populations than HSCs mobilized by G-CSF.

The HSCs mobilized by AMD3100 and GRO-beta showed patterns of gene expression similar to those of fetal HSCs.

“These highly engraftable hematopoietic stem cells produced by our new strategy are essentially the A+ students of bone marrow stem cells,” Dr Hoggatt said. “Finding that they express genes similar to those of fetal liver HSCs . . . suggests that they will be very good at moving into an empty bone marrow space and rapidly dividing to fill the marrow and produce blood. Now, we need to test the combination in a clinical trial to confirm its safety and effectiveness in humans.” ![]()

Procedure deemed unnecessary in most DVT patients

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis is largely inappropriate as first-line treatment for patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

The team found that anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis was no more effective than anticoagulation alone for preventing post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS).

Additionally, patients who received pharmacomechanical thrombolysis had a higher risk of major bleeding.

The researchers reported these findings in NEJM.

The trial, known as the ATTRACT study, was designed to determine whether performing pharmacomechanical thrombolysis as part of initial treatment for patients with DVT would reduce the number of patients who later develop PTS.

“The clinical research in deep vein thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome is very important to the clinical community and of interest to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI],” said Andrei Kindzelski, MD, PhD, the NHLBI program officer for the ATTRACT trial.

“This landmark study, conducted at 56 clinical sites, demonstrated, in an unbiased manner, no benefits of catheter-directed thrombolysis as a first-line deep vein thrombosis treatment, enabling patients to avoid an unnecessary medical procedure. At the same time, ATTRACT identified a potential future research need in more targeted use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in specific patient groups.”

The study included 692 patients who were randomized to receive anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Anticoagulation consisted of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin for at least 5 days, overlapped with long-term warfarin, as well as the prescription of elastic compression stockings.

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis consisted of catheter-mediated or device-mediated intrathrombus delivery of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and thrombus aspiration or maceration, with or without stenting.

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the development of PTS between 6 and 24 months of follow-up.

There was no significant difference in PTS incidence between the treatment arms. PTS occurred in 47% (157/336) of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 48% (171/355) of patients in the control group (risk ratio=0.96, P=0.56).

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis did reduce the severity of PTS, however. The incidence of moderate-to-severe PTS was 24% in the control group and 18% in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group (risk ratio=0.73; P=0.04).

Severity scores for PTS were significantly lower in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group than the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up (P<0.01 for each time point).

There was no significant difference between the treatment arms in the incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) over the 24-month follow-up period. Recurrent VTE was observed in 12% of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 8% of controls (P=0.09).

On the other hand, there was a significant increase in the incidence of major bleeding within 10 days in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group. The incidence was 1.7% (n=6) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 0.3% (n=1) in the control group (P=0.049).

“None of us was surprised to find that this treatment [pharmacomechanical thrombolysis] is riskier than blood-thinning drugs alone,” said study author Suresh Vedantham, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“To justify that extra risk, we would have had to show a dramatic improvement in long-term outcomes, and the study didn’t show that. We saw some improvement in disease severity but not enough to justify the risks for most patients.”

While the results indicate that most patients should not undergo pharmacomechanical thrombolysis, the data also hint that the benefits may outweigh the risks in some patients, such as those with exceptionally large clots.

“This is the first large, rigorous study to examine the ability of imaging-guided treatment to address post-thrombotic syndrome,” Dr Vedantham said. “This study will advance patient care by helping many people avoid an unnecessary procedure.”

“The findings are also interesting because there is the suggestion that at least some patients may have benefited. Sorting that out is going to be very important.”

For now, pharmacomechanical thrombolysis should be reserved for use as a second-line treatment for some carefully selected patients who are experiencing particularly severe limitations of leg function from DVT and who are not responding to anticoagulation alone, Dr Vedantham added.

This research was sponsored by NHLBI. Additional funding was provided by Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), and Genentech, which provided recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for the study. Compression stockings were donated by BSN Medical. ![]()

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis is largely inappropriate as first-line treatment for patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

The team found that anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis was no more effective than anticoagulation alone for preventing post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS).

Additionally, patients who received pharmacomechanical thrombolysis had a higher risk of major bleeding.

The researchers reported these findings in NEJM.

The trial, known as the ATTRACT study, was designed to determine whether performing pharmacomechanical thrombolysis as part of initial treatment for patients with DVT would reduce the number of patients who later develop PTS.

“The clinical research in deep vein thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome is very important to the clinical community and of interest to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI],” said Andrei Kindzelski, MD, PhD, the NHLBI program officer for the ATTRACT trial.

“This landmark study, conducted at 56 clinical sites, demonstrated, in an unbiased manner, no benefits of catheter-directed thrombolysis as a first-line deep vein thrombosis treatment, enabling patients to avoid an unnecessary medical procedure. At the same time, ATTRACT identified a potential future research need in more targeted use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in specific patient groups.”

The study included 692 patients who were randomized to receive anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Anticoagulation consisted of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin for at least 5 days, overlapped with long-term warfarin, as well as the prescription of elastic compression stockings.

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis consisted of catheter-mediated or device-mediated intrathrombus delivery of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and thrombus aspiration or maceration, with or without stenting.

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the development of PTS between 6 and 24 months of follow-up.

There was no significant difference in PTS incidence between the treatment arms. PTS occurred in 47% (157/336) of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 48% (171/355) of patients in the control group (risk ratio=0.96, P=0.56).

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis did reduce the severity of PTS, however. The incidence of moderate-to-severe PTS was 24% in the control group and 18% in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group (risk ratio=0.73; P=0.04).

Severity scores for PTS were significantly lower in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group than the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up (P<0.01 for each time point).

There was no significant difference between the treatment arms in the incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) over the 24-month follow-up period. Recurrent VTE was observed in 12% of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 8% of controls (P=0.09).

On the other hand, there was a significant increase in the incidence of major bleeding within 10 days in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group. The incidence was 1.7% (n=6) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 0.3% (n=1) in the control group (P=0.049).

“None of us was surprised to find that this treatment [pharmacomechanical thrombolysis] is riskier than blood-thinning drugs alone,” said study author Suresh Vedantham, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“To justify that extra risk, we would have had to show a dramatic improvement in long-term outcomes, and the study didn’t show that. We saw some improvement in disease severity but not enough to justify the risks for most patients.”

While the results indicate that most patients should not undergo pharmacomechanical thrombolysis, the data also hint that the benefits may outweigh the risks in some patients, such as those with exceptionally large clots.

“This is the first large, rigorous study to examine the ability of imaging-guided treatment to address post-thrombotic syndrome,” Dr Vedantham said. “This study will advance patient care by helping many people avoid an unnecessary procedure.”

“The findings are also interesting because there is the suggestion that at least some patients may have benefited. Sorting that out is going to be very important.”

For now, pharmacomechanical thrombolysis should be reserved for use as a second-line treatment for some carefully selected patients who are experiencing particularly severe limitations of leg function from DVT and who are not responding to anticoagulation alone, Dr Vedantham added.

This research was sponsored by NHLBI. Additional funding was provided by Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), and Genentech, which provided recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for the study. Compression stockings were donated by BSN Medical. ![]()

Researchers have found evidence to suggest that pharmacomechanical catheter-directed thrombolysis is largely inappropriate as first-line treatment for patients with acute proximal deep vein thrombosis (DVT).

The team found that anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis was no more effective than anticoagulation alone for preventing post-thrombotic syndrome (PTS).

Additionally, patients who received pharmacomechanical thrombolysis had a higher risk of major bleeding.

The researchers reported these findings in NEJM.

The trial, known as the ATTRACT study, was designed to determine whether performing pharmacomechanical thrombolysis as part of initial treatment for patients with DVT would reduce the number of patients who later develop PTS.

“The clinical research in deep vein thrombosis and post-thrombotic syndrome is very important to the clinical community and of interest to the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute [NHLBI],” said Andrei Kindzelski, MD, PhD, the NHLBI program officer for the ATTRACT trial.

“This landmark study, conducted at 56 clinical sites, demonstrated, in an unbiased manner, no benefits of catheter-directed thrombolysis as a first-line deep vein thrombosis treatment, enabling patients to avoid an unnecessary medical procedure. At the same time, ATTRACT identified a potential future research need in more targeted use of catheter-directed thrombolysis in specific patient groups.”

The study included 692 patients who were randomized to receive anticoagulation alone or anticoagulation plus pharmacomechanical thrombolysis.

Anticoagulation consisted of unfractionated heparin, enoxaparin, dalteparin, or tinzaparin for at least 5 days, overlapped with long-term warfarin, as well as the prescription of elastic compression stockings.

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis consisted of catheter-mediated or device-mediated intrathrombus delivery of recombinant tissue plasminogen activator and thrombus aspiration or maceration, with or without stenting.

Results

The study’s primary outcome was the development of PTS between 6 and 24 months of follow-up.

There was no significant difference in PTS incidence between the treatment arms. PTS occurred in 47% (157/336) of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 48% (171/355) of patients in the control group (risk ratio=0.96, P=0.56).

Pharmacomechanical thrombolysis did reduce the severity of PTS, however. The incidence of moderate-to-severe PTS was 24% in the control group and 18% in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group (risk ratio=0.73; P=0.04).

Severity scores for PTS were significantly lower in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group than the control group at 6, 12, 18, and 24 months of follow-up (P<0.01 for each time point).

There was no significant difference between the treatment arms in the incidence of recurrent venous thromboembolism (VTE) over the 24-month follow-up period. Recurrent VTE was observed in 12% of patients in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group and 8% of controls (P=0.09).

On the other hand, there was a significant increase in the incidence of major bleeding within 10 days in the pharmacomechanical-thrombolysis group. The incidence was 1.7% (n=6) in the pharmacomechanical thrombolysis group and 0.3% (n=1) in the control group (P=0.049).

“None of us was surprised to find that this treatment [pharmacomechanical thrombolysis] is riskier than blood-thinning drugs alone,” said study author Suresh Vedantham, MD, of Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, Missouri.

“To justify that extra risk, we would have had to show a dramatic improvement in long-term outcomes, and the study didn’t show that. We saw some improvement in disease severity but not enough to justify the risks for most patients.”

While the results indicate that most patients should not undergo pharmacomechanical thrombolysis, the data also hint that the benefits may outweigh the risks in some patients, such as those with exceptionally large clots.

“This is the first large, rigorous study to examine the ability of imaging-guided treatment to address post-thrombotic syndrome,” Dr Vedantham said. “This study will advance patient care by helping many people avoid an unnecessary procedure.”

“The findings are also interesting because there is the suggestion that at least some patients may have benefited. Sorting that out is going to be very important.”

For now, pharmacomechanical thrombolysis should be reserved for use as a second-line treatment for some carefully selected patients who are experiencing particularly severe limitations of leg function from DVT and who are not responding to anticoagulation alone, Dr Vedantham added.

This research was sponsored by NHLBI. Additional funding was provided by Boston Scientific, Covidien (now Medtronic), and Genentech, which provided recombinant tissue plasminogen activator for the study. Compression stockings were donated by BSN Medical. ![]()

Gene-based Zika vaccine proves immunogenic in healthy adults

An experimental Zika vaccine is safe and induces an immune response in healthy adults, according to research published in The Lancet.

Investigators tested 2 potential Zika vaccines, VRC5288 and VRC5283, in a pair of phase 1 trials.

Both vaccines were considered well-tolerated, but one of them, VRC5283, induced a greater immune response than the other.

Both vaccines were developed by investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Now, NIAID is leading an international effort to evaluate VRC5283 in a phase 2/2b trial.

“Following early reports that Zika infection during pregnancy can lead to birth defects, NIAID scientists rapidly created one of the first investigational Zika vaccines using a DNA-based platform and began initial studies in healthy adults less than 1 year later,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD.

To create their vaccines, the investigators inserted into plasmids genes that encode proteins found on the surface of the Zika virus.

The team developed 2 different plasmids for clinical testing: VRC5288 (Zika virus and Japanese encephalitis virus chimera) and VRC5283 (wild-type Zika virus).

In August 2016, NIAID initiated a phase 1 trial of the VRC5288 plasmid in 80 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 35. Subjects received a 4 mg dose via a needle and syringe injection in the arm muscle.

They received doses of VRC5288 at 0 and 8 weeks; 0 and 12 weeks; 0, 4, and 8 weeks; or 0, 4, and 20 weeks.

In December 2016, NIAID initiated a separate trial testing the VRC5283 plasmid. This study enrolled 45 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 50.

Subjects in this trial received 4 mg doses of VRC5283 at 0, 4, and 8 weeks. They were vaccinated in 3 different ways—via single-dose needle and syringe injection in 1 arm, via split-dose needle and syringe injection in each arm, or via needle-free injection in each arm.

Safety

The vaccinations were considered safe and well-tolerated in both trials, although some participants experienced mild to moderate reactions.

Local reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included pain/tenderness (mild—46% and 73%, moderate—0% and 7%), mild swelling (1% and 7%), and mild redness (6% and 2%).

Systemic reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included malaise (mild—25% and 33%, moderate—3% and 4%), myalgia (mild—18% and 13%, moderate—4% and 7%), headache (mild—19% and 29%, moderate—4% and 4%), chills (mild—6% and 2%, moderate—1% and 2%), nausea (mild—8% and 4%, moderate—1% and 0%), and joint pain (mild—5% and 16%, moderate—0% and 2%).

Immunogenicity

The investigators analyzed blood samples from all subjects 4 weeks after their final vaccinations.

The team found that 60% to 89% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5288, and 77% to 100% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5283.

Subjects who received VRC5283 via the needle-free injector all generated a neutralizing antibody response and had the highest levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Subjects who received VRC5283 in a split-dose administered to both arms had more robust immune responses than those receiving the full dose in 1 arm.

“NIAID has begun phase 2 testing of this candidate to determine if it can prevent Zika virus infection, and the promising phase 1 data . . . support its continued development,” Dr Fauci said. ![]()

An experimental Zika vaccine is safe and induces an immune response in healthy adults, according to research published in The Lancet.

Investigators tested 2 potential Zika vaccines, VRC5288 and VRC5283, in a pair of phase 1 trials.

Both vaccines were considered well-tolerated, but one of them, VRC5283, induced a greater immune response than the other.

Both vaccines were developed by investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Now, NIAID is leading an international effort to evaluate VRC5283 in a phase 2/2b trial.

“Following early reports that Zika infection during pregnancy can lead to birth defects, NIAID scientists rapidly created one of the first investigational Zika vaccines using a DNA-based platform and began initial studies in healthy adults less than 1 year later,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD.

To create their vaccines, the investigators inserted into plasmids genes that encode proteins found on the surface of the Zika virus.

The team developed 2 different plasmids for clinical testing: VRC5288 (Zika virus and Japanese encephalitis virus chimera) and VRC5283 (wild-type Zika virus).

In August 2016, NIAID initiated a phase 1 trial of the VRC5288 plasmid in 80 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 35. Subjects received a 4 mg dose via a needle and syringe injection in the arm muscle.

They received doses of VRC5288 at 0 and 8 weeks; 0 and 12 weeks; 0, 4, and 8 weeks; or 0, 4, and 20 weeks.

In December 2016, NIAID initiated a separate trial testing the VRC5283 plasmid. This study enrolled 45 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 50.

Subjects in this trial received 4 mg doses of VRC5283 at 0, 4, and 8 weeks. They were vaccinated in 3 different ways—via single-dose needle and syringe injection in 1 arm, via split-dose needle and syringe injection in each arm, or via needle-free injection in each arm.

Safety

The vaccinations were considered safe and well-tolerated in both trials, although some participants experienced mild to moderate reactions.

Local reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included pain/tenderness (mild—46% and 73%, moderate—0% and 7%), mild swelling (1% and 7%), and mild redness (6% and 2%).

Systemic reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included malaise (mild—25% and 33%, moderate—3% and 4%), myalgia (mild—18% and 13%, moderate—4% and 7%), headache (mild—19% and 29%, moderate—4% and 4%), chills (mild—6% and 2%, moderate—1% and 2%), nausea (mild—8% and 4%, moderate—1% and 0%), and joint pain (mild—5% and 16%, moderate—0% and 2%).

Immunogenicity

The investigators analyzed blood samples from all subjects 4 weeks after their final vaccinations.

The team found that 60% to 89% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5288, and 77% to 100% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5283.

Subjects who received VRC5283 via the needle-free injector all generated a neutralizing antibody response and had the highest levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Subjects who received VRC5283 in a split-dose administered to both arms had more robust immune responses than those receiving the full dose in 1 arm.

“NIAID has begun phase 2 testing of this candidate to determine if it can prevent Zika virus infection, and the promising phase 1 data . . . support its continued development,” Dr Fauci said. ![]()

An experimental Zika vaccine is safe and induces an immune response in healthy adults, according to research published in The Lancet.

Investigators tested 2 potential Zika vaccines, VRC5288 and VRC5283, in a pair of phase 1 trials.

Both vaccines were considered well-tolerated, but one of them, VRC5283, induced a greater immune response than the other.

Both vaccines were developed by investigators at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID).

Now, NIAID is leading an international effort to evaluate VRC5283 in a phase 2/2b trial.

“Following early reports that Zika infection during pregnancy can lead to birth defects, NIAID scientists rapidly created one of the first investigational Zika vaccines using a DNA-based platform and began initial studies in healthy adults less than 1 year later,” said NIAID Director Anthony S. Fauci, MD.

To create their vaccines, the investigators inserted into plasmids genes that encode proteins found on the surface of the Zika virus.

The team developed 2 different plasmids for clinical testing: VRC5288 (Zika virus and Japanese encephalitis virus chimera) and VRC5283 (wild-type Zika virus).

In August 2016, NIAID initiated a phase 1 trial of the VRC5288 plasmid in 80 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 35. Subjects received a 4 mg dose via a needle and syringe injection in the arm muscle.

They received doses of VRC5288 at 0 and 8 weeks; 0 and 12 weeks; 0, 4, and 8 weeks; or 0, 4, and 20 weeks.

In December 2016, NIAID initiated a separate trial testing the VRC5283 plasmid. This study enrolled 45 healthy volunteers ages 18 to 50.

Subjects in this trial received 4 mg doses of VRC5283 at 0, 4, and 8 weeks. They were vaccinated in 3 different ways—via single-dose needle and syringe injection in 1 arm, via split-dose needle and syringe injection in each arm, or via needle-free injection in each arm.

Safety

The vaccinations were considered safe and well-tolerated in both trials, although some participants experienced mild to moderate reactions.

Local reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included pain/tenderness (mild—46% and 73%, moderate—0% and 7%), mild swelling (1% and 7%), and mild redness (6% and 2%).

Systemic reactions (with VRC5288 and VRC5283, respectively) included malaise (mild—25% and 33%, moderate—3% and 4%), myalgia (mild—18% and 13%, moderate—4% and 7%), headache (mild—19% and 29%, moderate—4% and 4%), chills (mild—6% and 2%, moderate—1% and 2%), nausea (mild—8% and 4%, moderate—1% and 0%), and joint pain (mild—5% and 16%, moderate—0% and 2%).

Immunogenicity

The investigators analyzed blood samples from all subjects 4 weeks after their final vaccinations.

The team found that 60% to 89% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5288, and 77% to 100% of subjects generated a neutralizing antibody response to VRC5283.

Subjects who received VRC5283 via the needle-free injector all generated a neutralizing antibody response and had the highest levels of neutralizing antibodies.

Subjects who received VRC5283 in a split-dose administered to both arms had more robust immune responses than those receiving the full dose in 1 arm.

“NIAID has begun phase 2 testing of this candidate to determine if it can prevent Zika virus infection, and the promising phase 1 data . . . support its continued development,” Dr Fauci said. ![]()

What Are You Worth? The Basics of Business in Health Care

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.

Furthermore, how much do you contribute to the organization by testing? Dana works for a primary care clinic within a hospital system. Let’s assume her practice doesn’t offer colonoscopies or mammograms; how many referrals does she make to the hospital system for these tests? While she may not know the hospital’s profit margin on them, she can figure out how many she orders in a year. And what about the PA who works for a surgeon? Does he or she do the post-surgical checks? How much time does that save the surgeon, who can be providing higher revenue–producing services with the time saved? That contributes to the income of the practice, too! These are points you can make to justify your salary.

MIX IT UP

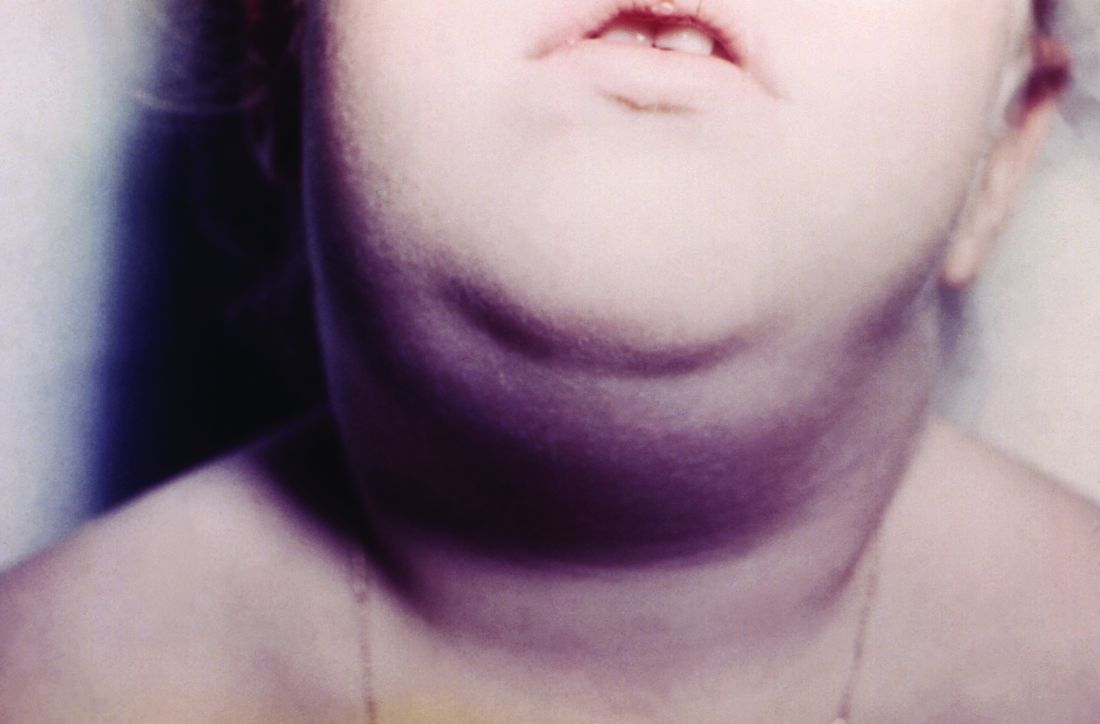

There is another major consideration for computing your financial contribution to the practice: understanding case mix. Let’s say your most common visit is billed as a 99213 and you charge $100 for this visit. You use this code 50 times in a week. Do you collect $100 x 50 or $5,000 per week? If you have a direct-pay practice and you collect all of it, yes, you will. If your practice accepts insurance, the number of patients you see with different insurers is called your case mix.

Let’s look at the impact of case mix on what you generate. Remember, it will take you about the same amount of time and effort to see these patients regardless of their insurer. Ask your practice manager what your case mix is. If he/she is not willing to share this information, you can get an estimate by looking at the demographics of your patient community. How many are older than 65? How many are on public assistance? Community needs assessments will provide you with this data; you can also check the patient’s chart or ask what insurance they have and add this to your log.

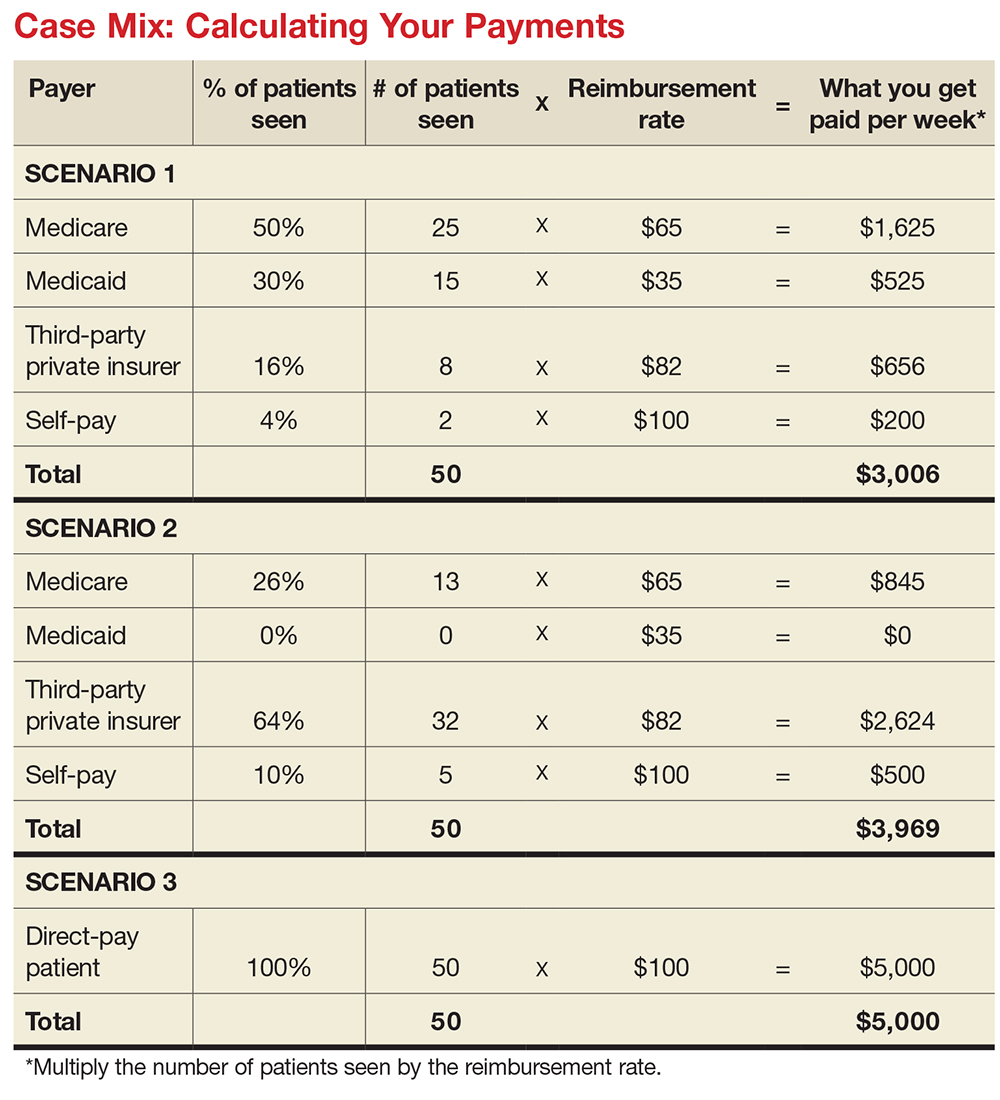

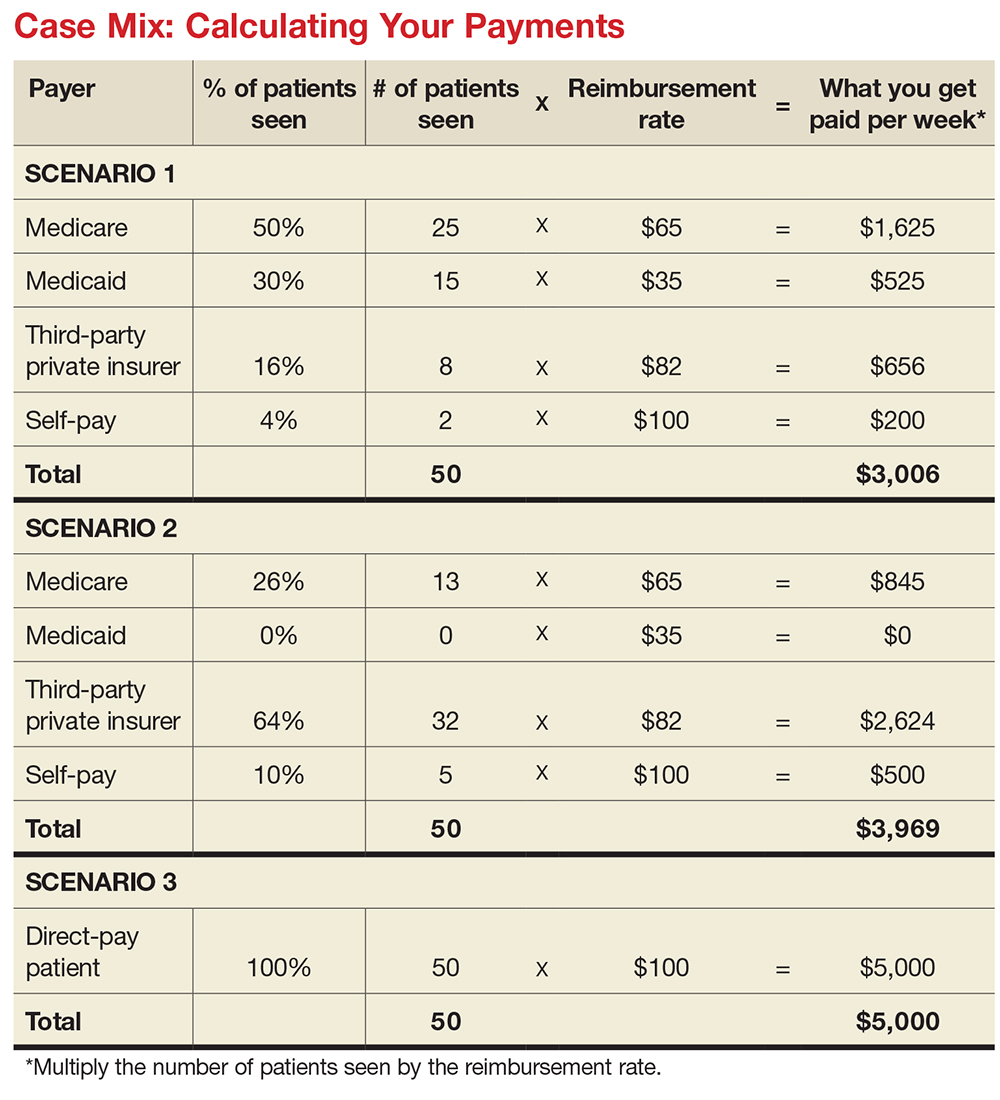

How much will you generate by seeing 50 patients in a week for a 99213 for which you charge $100? Let’s start with sample (not actual) base rates to illustrate the concept: $65 for Medicare, $35 for Medicaid, $82 for third-party private insurance, and $100 for self-pay.

Now let’s explore how case mix impacts revenue, with three different scenarios (see charts). In Scenario 1, 50% of your patients have Medicare, 30% have Medicaid, 16% have third-party private insurance, and 4% pay cash (self-pay). In Scenario 2, 26% have Medicare, 0% have Medicaid, 64% have private insurance, and 10% self-pay. In Scenario 3, your practice is a direct-pay practice with 100% self-payers and a 0% uncollectable rate.

In Scenario 1, with a case mix of 80% of your patient payments from Medicare or Medicaid, you generate $3,006 per week. If you see patients 48 weeks per year, you generate $144,288. In Scenario 2, with a case mix of 74% of your patient payments from private insurance, you generate $3,969 per week. In a year, you generate $190,512. And in Scenario 3, with 100% direct-pay patients, you generate $5,000 per week or $240,000 per year.

This example illustrates how case mix influences health care business, based on the current US reimbursement system. If you work for a practice that serves mostly Medicare and Medicaid patients, you do not command the same salary as an NP or PA who works for a direct-pay practice or one with a majority of privately insured patients.

OVERHEAD, OR IN OVER YOUR HEAD?

Now you have a better understanding of what your worth is to a practice. But what does it cost a practice to employ you? What’s your practice’s overhead?

Overhead includes the cost of processing claims; salaries and benefits; physician collaboration, if needed; rent, utilities, insurance, and depreciation. Overhead rates can range from 20% to 50%—meaning, if you generate $225,000 in revenue, it costs $45,000 to $112,500 to employ you. That leaves $112,500 (with higher overhead) to $180,000 (with lower overhead) for your salary. This revenue generation is an average: Many clinicians generate more than $225,000, while new graduates often generate less.

But in addition to generating more revenue, it can be beneficial to examine what you can do to help decrease the practice overhead. Because the bulk of overhead costs is salary, consider how many full-time-equivalent employees are needed to support you. Some NPs and PAs work with a full-time medical assistant or nurse, while others function very efficiently without one.

While providers like Dana and Kelsey can’t control what their practices pay for rent, utilities, or staffing, they can suggest improvements. Suggestions about scheduling, decreasing no-show rates, and improving recalls, immunization rates, and follow-up visits can all help increase revenue by decreasing day-to-day operating costs.

CONCLUSION

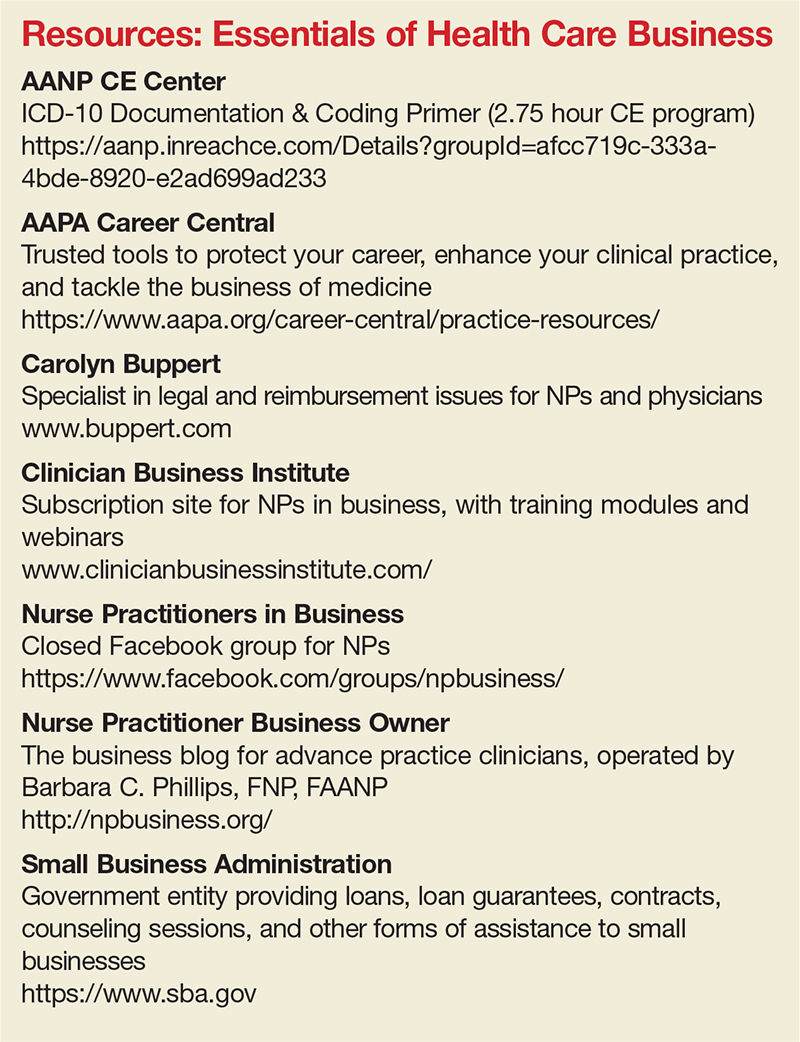

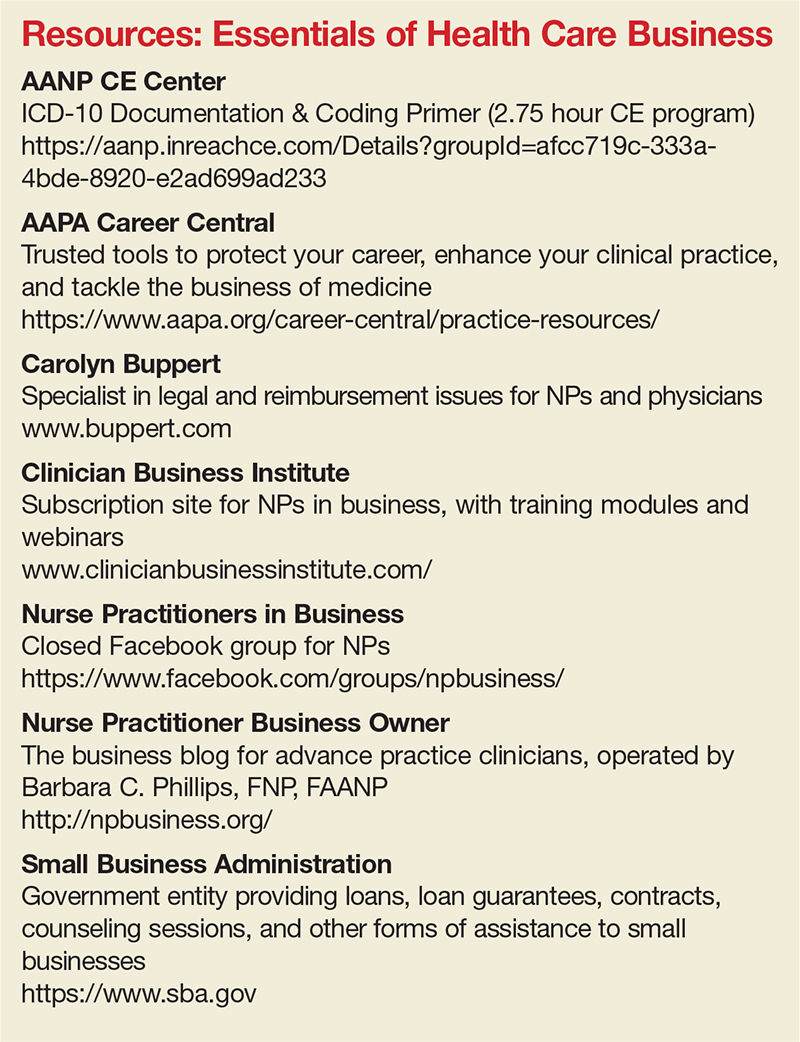

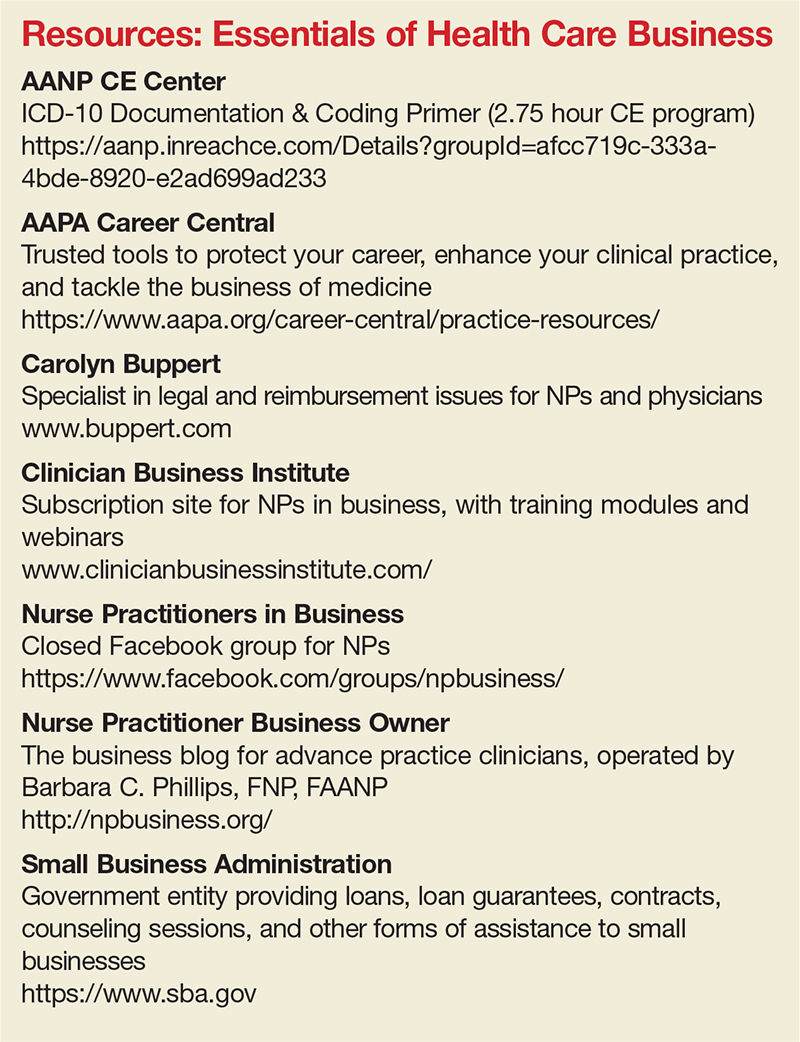

Most NPs and PAs went into their profession to help people—but that altruistic goal doesn’t mean you have to undervalue your own worth. Understanding the basic business of health care can help you negotiate your salary, maximize your income, and create new revenue models for patient care. While this may seem daunting to anyone who went to nursing or medical school, there are great resources to help you educate yourself on the essentials of health care business (see box).

Understanding the infrastructure of the health care system will help NPs and PAs become leaders who can impact health care change. These basic business skills are necessary to ensure fair and full compensation for the roles they play.

1. LaFevers D, Ward-Smith P, Wright W. Essential nurse practitioner business knowledge: an interprofessional perspective. J Am Assoc Nurse Pract. 2015;4:181-184.

2. Buppert C. Nurse Practitioner’s Business and Legal Guide. 6th ed. Burlington, MA: Jones and Bartlett Learning; 2018: 311-324.

3. Fritz J. How is a nonprofit different from a for-profit business? Getting beyond the myths. The Balance. April 3, 2017. www.thebalance.com/how-is-a-nonprofit-different-from-for-profit-business-2502472. Accessed November 20, 2017.

4. Dillon D, Hoyson P. Beginning employment: a guide for the new nurse practitioner. J Nurse Pract. 2014;1:55-59.

Dana, an adult nurse practitioner, has been working for two years at a large, suburban primary care practice owned by the regional hospital system. She sees too many patients per day, never has enough time to chart properly, and is concerned by the expanding role of the medical assistants. She sees salary postings on social media and feels she is underpaid. She fantasizes about owning her own practice but would settle for making more money. She’s heard that some NPs have profit-sharing, but she’s not exactly sure what that means.

Kelsey, a PA, is looking for his first job out of school. He’s been offered a full-time, salaried position with benefits at an urgent care center, but he doesn’t know if this is a good deal for him or not. The family physicians there make $85,000 more per year than the PAs, although the roles are quite similar.

DOWN TO BUSINESS

The US health care crisis is, fundamentally, a financial crisis; our system is comprised of both for-profit and not-for-profit (NFP) businesses. Every day, NPs and PAs are making decisions that affect their job satisfaction, performance, and retention. Many lack confidence in their ability to make good decisions about their salaries, because they don’t understand the business of health care.1 To survive and thrive, NPs and PAs must understand the basics of the business end.2

So, what qualifies as a business? Any commercial, retail, or professional entity that earns and spends money. It doesn’t matter if it is a for-profit or NFP organization; it can’t survive unless it makes more money than it spends. How that money is earned varies, from selling services and/or goods to receiving grants, income from interest or rentals, or government subsidies.

The major difference between a for-profit and a NFP organization is who controls the money.3 The owners of a for-profit company control the profits, which may be split among the owners or reinvested in the company. A NFP business may use its profits to provide charity care, offset losses of other programs, or invest in capital improvements (eg, new building, equipment). How the profits are to be used is outlined in the business goals or the mission statement of the entity. There are also federal and state regulations for both types of businesses; visit the Internal Revenue Service website for details (www.irs.gov/charities-non-profits; www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed).

HOW YOU GET PAID FOR SERVICES

As a PA or NP, you generate income for your employer regardless of whether you work for a for-profit or NFP business. Your patients are billed for services rendered.

If you work for a fee-for-service or NFP practice with insurance contracts, the bill gets coded and electronically submitted for payment. Each insurer, whether private or government (ie, Medicare or Medicaid), has established what they will reimburse you for that service. The reimbursement rate is part of your contract with that insurer. Rates are determined based on your profession, licensure, geographic locale, type of facility, and the market rate. An insurance representative would be able to tell you your reimbursement rate for the most common procedure codes you use. (Your employer has this information but may or may not share it with you.) Medicare rates can be found online at www.cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/.

If you work for a direct-pay practice, you collect what you bill directly from the patient, often at the time of the visit. A direct-pay practice does not have insurance contracts and does not bill insurers for patients who have insurance; rather, they provide a billing statement with procedure and diagnostic codes and NPI numbers to the patient, who can submit it directly to their insurer. If the insurer accepts out-of-network providers (those with whom they have no contract), they will reimburse the patient directly.

If you work in a fee-for-service or NFP practice, you may see patients who do not have insurance or who have very high deductibles and pay cash for their services. This does not make it a direct-pay practice. Also, by law, fee-for-service and NFP practices can only have one fee schedule for the entire practice. So, you can’t charge one patient $55 for a flu shot and another patient $25. These practices can offer discounts for cash payments at the time of service, to help reduce the set fees, if they choose.

TALKIN’ ’BOUT YOUR (REVENUE) GENERATION

To know how much you can negotiate for your salary and benefits—your total compensation package (of which benefits is often about 30%)—it is critical to know how much revenue you can generate for your employer.4 How can you figure this out?

If you are already working, you can ask your practice manager for some data. In some practices, this information is readily shared, perhaps as a means to boost productivity and even allow comparison between employees. If your practice manager is not forthcoming, you can collect the relevant information yourself. It may be challenging, but it is vital information to have. You need to know how many patients you see per day (keep a log for a month), what their payment source is (specific insurer or self-pay), and what the reimbursement rates are. Although reimbursement rates are deemed confidential per your insurance contract and therefore can’t be shared, you can find Medicare and Medicaid rates online. You can also call the provider representative from each insurer and ask for your reimbursement rates for your five or so most commonly used codes.

Another consideration is payment received (ie, not just what you charge). Do all patients pay everything they owe? Not always. Understand the difference between what you bill, what is allowed, and what you collect. The percentage of what is not collected is called the uncollectable rate. Factor that in.