User login

Consider ‘impactibility’ to prevent hospital readmissions

With the goal of reducing 28-day or 30-day readmissions, some health care teams are turning to predictive models to identify patients at high risk for readmission and to efficiently focus resource-intensive prevention strategies. Recently, there’s been a rapid multiplying of these models.

Many of these models do accurately predict readmission risk, according to a recent BMJ editorial. “Among the 14 published models that target all unplanned readmissions (rather than readmissions for specific patient groups), the ‘C statistic’ ranges from 0.55 to 0.80, meaning that, when presented with two patients, these models correctly identify the higher risk individual between 55% and 80% of the time,” the authors wrote.

But, the authors suggested, the real value is not in simply making predictions but in using predictive models in ways that improve outcomes for patients.

“This will require linking predictive models to actionable opportunities for improving care,” they wrote. “Such linkages will most likely be identified through close collaboration between analytical teams, health care practitioners, and patients.” Being at high risk of readmission is not the only consideration; the patient must also be able to benefit from interventions being considered – they must be “impactible.”

“The distinction between predictive risk and impactibility might explain why practitioners tend to identify quite different patients for intervention than predictive risk models,” the authors wrote.

But together, predictive models and clinicians might produce more effective decisions than either does alone. “One of the strengths of predictive models is that they produce objective and consistent judgments regarding readmission risk, whereas clinical judgment can be affected by personal attitudes or attentiveness. Predictive risk models can also be operationalised across whole populations, and might therefore identify needs that would otherwise be missed by clinical teams (e.g., among more socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods or groups with inadequate primary care). On the other hand, clinicians have access to a much wider range of information regarding patients than predictive risk models, which is essential to judge impactibility.”

The authors conclude, “The predictive modelling enterprise would benefit enormously from such collaboration because the real goal of this activity lies not in predicting the risk of readmission but in identifying patients at risk for preventable readmissions and ‘impactible’ by available interventions.”

Reference

Steventon A et al. Preventing hospital readmissions: The importance of considering ‘impactibility,’ not just predicted risk. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Oct;26(10):782-5. Accessed Oct. 9, 2017.

With the goal of reducing 28-day or 30-day readmissions, some health care teams are turning to predictive models to identify patients at high risk for readmission and to efficiently focus resource-intensive prevention strategies. Recently, there’s been a rapid multiplying of these models.

Many of these models do accurately predict readmission risk, according to a recent BMJ editorial. “Among the 14 published models that target all unplanned readmissions (rather than readmissions for specific patient groups), the ‘C statistic’ ranges from 0.55 to 0.80, meaning that, when presented with two patients, these models correctly identify the higher risk individual between 55% and 80% of the time,” the authors wrote.

But, the authors suggested, the real value is not in simply making predictions but in using predictive models in ways that improve outcomes for patients.

“This will require linking predictive models to actionable opportunities for improving care,” they wrote. “Such linkages will most likely be identified through close collaboration between analytical teams, health care practitioners, and patients.” Being at high risk of readmission is not the only consideration; the patient must also be able to benefit from interventions being considered – they must be “impactible.”

“The distinction between predictive risk and impactibility might explain why practitioners tend to identify quite different patients for intervention than predictive risk models,” the authors wrote.

But together, predictive models and clinicians might produce more effective decisions than either does alone. “One of the strengths of predictive models is that they produce objective and consistent judgments regarding readmission risk, whereas clinical judgment can be affected by personal attitudes or attentiveness. Predictive risk models can also be operationalised across whole populations, and might therefore identify needs that would otherwise be missed by clinical teams (e.g., among more socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods or groups with inadequate primary care). On the other hand, clinicians have access to a much wider range of information regarding patients than predictive risk models, which is essential to judge impactibility.”

The authors conclude, “The predictive modelling enterprise would benefit enormously from such collaboration because the real goal of this activity lies not in predicting the risk of readmission but in identifying patients at risk for preventable readmissions and ‘impactible’ by available interventions.”

Reference

Steventon A et al. Preventing hospital readmissions: The importance of considering ‘impactibility,’ not just predicted risk. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Oct;26(10):782-5. Accessed Oct. 9, 2017.

With the goal of reducing 28-day or 30-day readmissions, some health care teams are turning to predictive models to identify patients at high risk for readmission and to efficiently focus resource-intensive prevention strategies. Recently, there’s been a rapid multiplying of these models.

Many of these models do accurately predict readmission risk, according to a recent BMJ editorial. “Among the 14 published models that target all unplanned readmissions (rather than readmissions for specific patient groups), the ‘C statistic’ ranges from 0.55 to 0.80, meaning that, when presented with two patients, these models correctly identify the higher risk individual between 55% and 80% of the time,” the authors wrote.

But, the authors suggested, the real value is not in simply making predictions but in using predictive models in ways that improve outcomes for patients.

“This will require linking predictive models to actionable opportunities for improving care,” they wrote. “Such linkages will most likely be identified through close collaboration between analytical teams, health care practitioners, and patients.” Being at high risk of readmission is not the only consideration; the patient must also be able to benefit from interventions being considered – they must be “impactible.”

“The distinction between predictive risk and impactibility might explain why practitioners tend to identify quite different patients for intervention than predictive risk models,” the authors wrote.

But together, predictive models and clinicians might produce more effective decisions than either does alone. “One of the strengths of predictive models is that they produce objective and consistent judgments regarding readmission risk, whereas clinical judgment can be affected by personal attitudes or attentiveness. Predictive risk models can also be operationalised across whole populations, and might therefore identify needs that would otherwise be missed by clinical teams (e.g., among more socioeconomically deprived neighbourhoods or groups with inadequate primary care). On the other hand, clinicians have access to a much wider range of information regarding patients than predictive risk models, which is essential to judge impactibility.”

The authors conclude, “The predictive modelling enterprise would benefit enormously from such collaboration because the real goal of this activity lies not in predicting the risk of readmission but in identifying patients at risk for preventable readmissions and ‘impactible’ by available interventions.”

Reference

Steventon A et al. Preventing hospital readmissions: The importance of considering ‘impactibility,’ not just predicted risk. BMJ Qual Saf. 2017 Oct;26(10):782-5. Accessed Oct. 9, 2017.

Three-month response to CAR T-cells looks durable in DLBCL

ATLANTA – Responses 3 months after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy look durable in adults with transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to updated results from the single-arm, global, phase 2 JULIET trial.

Fully 95% of patients who had a complete response to CTL019 (tisagenlecleucel; Kymriah) at 3 months maintained that complete response at 6 months, Stephen J. Schuster, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL tend to face a very poor prognosis, noted Dr. Schuster of Perelman School of Medicine and Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation “is capable of long-term survival, but in very few patients,” he said. A dismal 8% of patients completely respond to salvage treatment and only about one in five partially respond. Both levels of response are short-lived, with a median survival of about 4 months.

Meanwhile, CTL019 therapy has produced durable complete remissions in children with lymphoblastic leukemia and in adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Dr. Schuster and his associates wrote in an article simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Dec 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566).

To test the CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, they enrolled affected adults who had received at least two prior lines of antineoplastic treatment and who were not candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation.

Treatment consisted of a single CTL019 infusion (median dose, 3.1 × 108 cells; range, 0.1 × 108 to 6.0 × 108 cells), usually after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Previously, patients had received a median of three lines of therapy, and about half had undergone autologous stem cell transplantation.

Median time from infusion to data cutoff in March 2017 was 5.6 months. Among 81 patients followed for at least 3 months before data cutoff, best overall response rate was 53% and 40% had a complete response. Overall response rates were 38% at 3 months and 37% at 6 months. Rates of complete response as confirmed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron-emission tomography (PET) were 32% at 3 months and 30% at 6 months.These findings highlight the predictive power of 3-month response to CTL019 therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Dr. Schuster said. Among all responders, 74% remained relapse free at 6 months, meaning that median duration of response and median overall survival were not reached at data cutoff.

Dr. Schuster also reported that 26% of patients were infused as outpatients, which he called “easy to do” and appropriate as long as patients who become febrile are admitted and monitored for cytokine release syndrome. Three-quarters of patients who were infused as outpatients were able to remain home for at least 3 days afterward, he said.

Adverse events typified those of CAR T-cell therapy, including cytokine release syndrome (all grades: 58%; grade 3-4: 23%) and neurological toxicities (all grades: 21%; grade 3-4: 12%). The current labeling for CTL019 in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia also includes a boxed warning for these toxicities.Tisagenlecleucel, the first-ever approved CAR T-cell therapy, is made by using a lentiviral vector to genetically engineer a patient’s own T-cells to express a CAR for the pan-B-cell CD19 antigen. These anti-CD19 CAR T-cells are then expanded in the laboratory, frozen for shipping purposes, and infused back into patients. In October 2017, Novartis submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration to expand the label for CTL019 to include transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory DLBCL.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals anticipates large-scale production in 2018, Dr. Schuster said. Manufacturing time has been cut to 22 days from the 30-day turnaround used in the trial, he reported.

Dr. Schuster also said that he sees no point in retreating patients whose relapsed/refractory DLBCL doesn’t respond to tisagenlecleucel, and that JULIET did not test this approach. “If someone fails therapy and you retreat, you don’t see success, in my experience,” he said. “If patients respond and then fail later, then you retreat and you may succeed.”

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored JULIET. Dr. Schuster disclosed consultancy and research funding from Novartis and ties to Celgene, Gilead, Genentech, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Schuster S et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 577.

ATLANTA – Responses 3 months after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy look durable in adults with transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to updated results from the single-arm, global, phase 2 JULIET trial.

Fully 95% of patients who had a complete response to CTL019 (tisagenlecleucel; Kymriah) at 3 months maintained that complete response at 6 months, Stephen J. Schuster, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL tend to face a very poor prognosis, noted Dr. Schuster of Perelman School of Medicine and Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation “is capable of long-term survival, but in very few patients,” he said. A dismal 8% of patients completely respond to salvage treatment and only about one in five partially respond. Both levels of response are short-lived, with a median survival of about 4 months.

Meanwhile, CTL019 therapy has produced durable complete remissions in children with lymphoblastic leukemia and in adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Dr. Schuster and his associates wrote in an article simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Dec 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566).

To test the CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, they enrolled affected adults who had received at least two prior lines of antineoplastic treatment and who were not candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation.

Treatment consisted of a single CTL019 infusion (median dose, 3.1 × 108 cells; range, 0.1 × 108 to 6.0 × 108 cells), usually after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Previously, patients had received a median of three lines of therapy, and about half had undergone autologous stem cell transplantation.

Median time from infusion to data cutoff in March 2017 was 5.6 months. Among 81 patients followed for at least 3 months before data cutoff, best overall response rate was 53% and 40% had a complete response. Overall response rates were 38% at 3 months and 37% at 6 months. Rates of complete response as confirmed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron-emission tomography (PET) were 32% at 3 months and 30% at 6 months.These findings highlight the predictive power of 3-month response to CTL019 therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Dr. Schuster said. Among all responders, 74% remained relapse free at 6 months, meaning that median duration of response and median overall survival were not reached at data cutoff.

Dr. Schuster also reported that 26% of patients were infused as outpatients, which he called “easy to do” and appropriate as long as patients who become febrile are admitted and monitored for cytokine release syndrome. Three-quarters of patients who were infused as outpatients were able to remain home for at least 3 days afterward, he said.

Adverse events typified those of CAR T-cell therapy, including cytokine release syndrome (all grades: 58%; grade 3-4: 23%) and neurological toxicities (all grades: 21%; grade 3-4: 12%). The current labeling for CTL019 in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia also includes a boxed warning for these toxicities.Tisagenlecleucel, the first-ever approved CAR T-cell therapy, is made by using a lentiviral vector to genetically engineer a patient’s own T-cells to express a CAR for the pan-B-cell CD19 antigen. These anti-CD19 CAR T-cells are then expanded in the laboratory, frozen for shipping purposes, and infused back into patients. In October 2017, Novartis submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration to expand the label for CTL019 to include transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory DLBCL.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals anticipates large-scale production in 2018, Dr. Schuster said. Manufacturing time has been cut to 22 days from the 30-day turnaround used in the trial, he reported.

Dr. Schuster also said that he sees no point in retreating patients whose relapsed/refractory DLBCL doesn’t respond to tisagenlecleucel, and that JULIET did not test this approach. “If someone fails therapy and you retreat, you don’t see success, in my experience,” he said. “If patients respond and then fail later, then you retreat and you may succeed.”

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored JULIET. Dr. Schuster disclosed consultancy and research funding from Novartis and ties to Celgene, Gilead, Genentech, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Schuster S et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 577.

ATLANTA – Responses 3 months after chimeric antigen receptor (CAR) T-cell therapy look durable in adults with transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), according to updated results from the single-arm, global, phase 2 JULIET trial.

Fully 95% of patients who had a complete response to CTL019 (tisagenlecleucel; Kymriah) at 3 months maintained that complete response at 6 months, Stephen J. Schuster, MD, said at the annual meeting of the American Society of Hematology.

Patients with relapsed/refractory DLBCL tend to face a very poor prognosis, noted Dr. Schuster of Perelman School of Medicine and Abramson Cancer Center, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous stem cell transplantation “is capable of long-term survival, but in very few patients,” he said. A dismal 8% of patients completely respond to salvage treatment and only about one in five partially respond. Both levels of response are short-lived, with a median survival of about 4 months.

Meanwhile, CTL019 therapy has produced durable complete remissions in children with lymphoblastic leukemia and in adults with chronic lymphocytic leukemia, Dr. Schuster and his associates wrote in an article simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine (2017 Dec 10. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1708566).

To test the CAR T-cell therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, they enrolled affected adults who had received at least two prior lines of antineoplastic treatment and who were not candidates for autologous stem cell transplantation.

Treatment consisted of a single CTL019 infusion (median dose, 3.1 × 108 cells; range, 0.1 × 108 to 6.0 × 108 cells), usually after lymphodepleting chemotherapy. Previously, patients had received a median of three lines of therapy, and about half had undergone autologous stem cell transplantation.

Median time from infusion to data cutoff in March 2017 was 5.6 months. Among 81 patients followed for at least 3 months before data cutoff, best overall response rate was 53% and 40% had a complete response. Overall response rates were 38% at 3 months and 37% at 6 months. Rates of complete response as confirmed by 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose–positron-emission tomography (PET) were 32% at 3 months and 30% at 6 months.These findings highlight the predictive power of 3-month response to CTL019 therapy in relapsed/refractory DLBCL, Dr. Schuster said. Among all responders, 74% remained relapse free at 6 months, meaning that median duration of response and median overall survival were not reached at data cutoff.

Dr. Schuster also reported that 26% of patients were infused as outpatients, which he called “easy to do” and appropriate as long as patients who become febrile are admitted and monitored for cytokine release syndrome. Three-quarters of patients who were infused as outpatients were able to remain home for at least 3 days afterward, he said.

Adverse events typified those of CAR T-cell therapy, including cytokine release syndrome (all grades: 58%; grade 3-4: 23%) and neurological toxicities (all grades: 21%; grade 3-4: 12%). The current labeling for CTL019 in children and young adults with acute lymphoblastic leukemia also includes a boxed warning for these toxicities.Tisagenlecleucel, the first-ever approved CAR T-cell therapy, is made by using a lentiviral vector to genetically engineer a patient’s own T-cells to express a CAR for the pan-B-cell CD19 antigen. These anti-CD19 CAR T-cells are then expanded in the laboratory, frozen for shipping purposes, and infused back into patients. In October 2017, Novartis submitted a biologics license application to the Food and Drug Administration to expand the label for CTL019 to include transplant-ineligible relapsed/refractory DLBCL.

Novartis Pharmaceuticals anticipates large-scale production in 2018, Dr. Schuster said. Manufacturing time has been cut to 22 days from the 30-day turnaround used in the trial, he reported.

Dr. Schuster also said that he sees no point in retreating patients whose relapsed/refractory DLBCL doesn’t respond to tisagenlecleucel, and that JULIET did not test this approach. “If someone fails therapy and you retreat, you don’t see success, in my experience,” he said. “If patients respond and then fail later, then you retreat and you may succeed.”

Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored JULIET. Dr. Schuster disclosed consultancy and research funding from Novartis and ties to Celgene, Gilead, Genentech, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

SOURCE: Schuster S et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 577.

REPORTING FROM ASH 2017

Key clinical point:

Major finding: Among 81 patients with at least 3 months of follow-up, best overall response rate was 53% (95% CI, 42%-64%; P less than .0001) and rates of complete response were 32% at 3 months and 30% at 6 months.

Study details: JULIET is an international, single-arm, phase 2 study of adults with relapsed/refractory DLBCL.

Disclosures: Novartis Pharmaceuticals sponsored JULIET. Dr. Schuster reported consultancy and research funding from Novartis and ties to Celgene, Gilead, Genentech, and several other pharmaceutical companies.

Source: Schuster S et al. ASH 2017 Abstract 577.

Shift to long-term ‘maternal care’ needs boost

WASHINGTON – George R. Saade, MD, wants to see a Time magazine cover story like the 2010 feature titled, “How the first 9 months shape the rest of your life” – except this new story would read “How the first 9 months shape the rest of the mother’s life.”

It’s time, he says, that pregnancy truly be appreciated as a “window to future health” for the mother as well as for the baby, and that the term “maternal care” replaces prenatal care. “How many of your [primary care] providers have asked you if you’ve had any pregnancies and if any of your pregnancies were complicated by hypertension, preterm delivery, growth restriction, or gestational diabetes?” Dr. Saade asked at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“It’s better than before, but not good enough ... Checking with patients 6 weeks postpartum is not enough” to prevent long-term metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, he said. “We need regular screening of women.”

The relationship between gestational diabetes (GDM) and subsequent type 2 diabetes, demonstrated several decades ago, offered the “first evidence that pregnancy is a window to future health,” and evidence of the relationship continues to grow. “We know today that there is no other predictive marker of type 2 diabetes that is better and stronger than gestational diabetes,” said Dr. Saade, chief of obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

GDM has also recently been shown to elevate cardiovascular risk independent of its association with type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease.

And similarly, there is now an incontrovertible body of evidence that women who have had preeclampsia are at significantly higher risk of developing hypertension, stroke, and ischemic heart disease later in life than are women who have not have preeclampsia, Dr. Saade said.

Layered evidence

The study that first caught Dr. Saade’s attention was a large Norwegian population-based study published in 2001 that looked at maternal mortality up to 25 years after pregnancy. Women who had preeclampsia had a 1.2-fold higher long-term risk of death from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and stroke – and women with a history of both preeclampsia and a preterm delivery had a 2.71-fold higher risk – than that of women without such history.

Looking at cardiovascular causes of death specifically, the risk among women with both preeclampsia and preterm delivery was 8.12-fold higher than in women who did not have preeclampsia.

Since then, studies and reviews conducted in the United States and Europe have shown that a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, more than triples the risk of later hypertension, and also increases the risk of stroke, though more moderately.

Recently, Dr. Saade said, researchers have also begun reporting subclinical cardiac abnormalities in women with a history of preeclampsia. A study of 107 women with preeclampsia and 41 women with uneventful pregnancies found that the prevalence of subclinical heart failure (heart failure Stage B) was approximately 3.5% higher in the short term in the preeclampsia group. The women underwent regular cardiac ultrasound and other cardiovascular risk assessment tests 4-10 years postpartum (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49[1]:143-9).

Preterm delivery and small for gestational age have also been associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease and other cardiovascular events later in life. And gestational hypertension, research has shown, is a clear risk factor for later hypertension. “We always think of preeclampsia as a different disease, but as far as long-term health is concerned, it doesn’t matter if a woman had preeclampsia or gestational hypertension; she’s still at [greater] risk for hypertension later,” Dr. Saade said.

“And we don’t have to wait 30 years to see evidence” of the association between pregnancy complications and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, he emphasized. A recent retrospective cohort study of more than 300,000 women in Florida showed that women who experienced a maternal placental syndrome during their first pregnancy were at higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease during just 5 years of follow-up (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-14).

Into practice

Regular screening of women whose pregnancies were complicated by conditions associated with long-term health risks “need not be that sophisticated,” Dr. Saade said. Measurement of blood pressure, waist circumference, fasting lipid profile, and fasting glucose is often enough for basic maternal health surveillance, he said.

Dr. Saade said he and some other experts in the field are recommending yearly follow-up for patients who’ve had preeclampsia and other complications. Among the other experts urging early heart disease risk screening is Graeme N. Smith, MD, PhD, an ob.gyn in Ontario who has developed surveillance protocols, follow-up forms, and risk prediction tools for use in a maternal health clinic he established at Kingston General Hospital, Queens University. At the meeting, Dr. Saade encouraged the audience to access Dr. Smith’s resources.

The American Heart Association, in its 2011 guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women, includes pregnancy risks factors (specifically a history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or pregnancy-induced hypertension) as part of its list of major factors for use in risk assessment (Circulation. 2011;123:1243-62).

But as Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MPH, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s division of research, pointed out during another presentation at the meeting, there is more work to be done. Reproductive history is not included in existing disease prediction or risk stratification models for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, making it hard at this point to devise specific screening protocols and schedules, especially when it comes to a history of GDM, she said.

“We need more coordinated systems, surveillance in younger women, and some prediction models so that we can know who is at highest risk and needs more surveillance,” she said.

The AHA’s inclusion of GDM history is based on its strong link to overt diabetes, but recent evidence has shown that a history of GDM can independently elevate cardiovascular risk, she noted. Research from the Nurses Health Study II cohort, for instance, found a 30% higher relative risk of cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction and stroke) in women with a history of GDM without progression to diabetes, compared with women who did not have GDM or diabetes (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1735-42).

Dr. Gunderson has also found through analyses of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study data that women who had GDM but did not go on to develop overt diabetes or impaired glycemia had greater carotid intima media thickness many years post delivery than did women without a history of gestational diabetes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3[2]:e000490).

In some models, she has written, this difference in carotid intima media thickness could represent 3-5 years of greater vascular aging for women with previous gestational diabetes and no apparent metabolic dysfunction outside of pregnancy (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1742-4).

There’s a question, she and Dr. Saade both noted, of whether pregnancies unmask previous dispositions to cardiovascular disease or whether pregnancy complications more directly drive adverse long-term outcomes. There is evidence that disorders such as GDM, Dr. Gunderson said, are superimposed on already altered metabolism. But at this time, Dr. Saade said, it appears that “the answer is both.”

According to Dr. Saade, at least three studies are currently following women prospectively to learn more about pregnancy as a window to future cardiovascular health. One of them is the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study–Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Heart Health Study; some data from this study will be presented soon, he said.

Both Dr. Saade and Dr. Gunderson reported in their presentations that they had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – George R. Saade, MD, wants to see a Time magazine cover story like the 2010 feature titled, “How the first 9 months shape the rest of your life” – except this new story would read “How the first 9 months shape the rest of the mother’s life.”

It’s time, he says, that pregnancy truly be appreciated as a “window to future health” for the mother as well as for the baby, and that the term “maternal care” replaces prenatal care. “How many of your [primary care] providers have asked you if you’ve had any pregnancies and if any of your pregnancies were complicated by hypertension, preterm delivery, growth restriction, or gestational diabetes?” Dr. Saade asked at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“It’s better than before, but not good enough ... Checking with patients 6 weeks postpartum is not enough” to prevent long-term metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, he said. “We need regular screening of women.”

The relationship between gestational diabetes (GDM) and subsequent type 2 diabetes, demonstrated several decades ago, offered the “first evidence that pregnancy is a window to future health,” and evidence of the relationship continues to grow. “We know today that there is no other predictive marker of type 2 diabetes that is better and stronger than gestational diabetes,” said Dr. Saade, chief of obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

GDM has also recently been shown to elevate cardiovascular risk independent of its association with type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease.

And similarly, there is now an incontrovertible body of evidence that women who have had preeclampsia are at significantly higher risk of developing hypertension, stroke, and ischemic heart disease later in life than are women who have not have preeclampsia, Dr. Saade said.

Layered evidence

The study that first caught Dr. Saade’s attention was a large Norwegian population-based study published in 2001 that looked at maternal mortality up to 25 years after pregnancy. Women who had preeclampsia had a 1.2-fold higher long-term risk of death from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and stroke – and women with a history of both preeclampsia and a preterm delivery had a 2.71-fold higher risk – than that of women without such history.

Looking at cardiovascular causes of death specifically, the risk among women with both preeclampsia and preterm delivery was 8.12-fold higher than in women who did not have preeclampsia.

Since then, studies and reviews conducted in the United States and Europe have shown that a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, more than triples the risk of later hypertension, and also increases the risk of stroke, though more moderately.

Recently, Dr. Saade said, researchers have also begun reporting subclinical cardiac abnormalities in women with a history of preeclampsia. A study of 107 women with preeclampsia and 41 women with uneventful pregnancies found that the prevalence of subclinical heart failure (heart failure Stage B) was approximately 3.5% higher in the short term in the preeclampsia group. The women underwent regular cardiac ultrasound and other cardiovascular risk assessment tests 4-10 years postpartum (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49[1]:143-9).

Preterm delivery and small for gestational age have also been associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease and other cardiovascular events later in life. And gestational hypertension, research has shown, is a clear risk factor for later hypertension. “We always think of preeclampsia as a different disease, but as far as long-term health is concerned, it doesn’t matter if a woman had preeclampsia or gestational hypertension; she’s still at [greater] risk for hypertension later,” Dr. Saade said.

“And we don’t have to wait 30 years to see evidence” of the association between pregnancy complications and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, he emphasized. A recent retrospective cohort study of more than 300,000 women in Florida showed that women who experienced a maternal placental syndrome during their first pregnancy were at higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease during just 5 years of follow-up (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-14).

Into practice

Regular screening of women whose pregnancies were complicated by conditions associated with long-term health risks “need not be that sophisticated,” Dr. Saade said. Measurement of blood pressure, waist circumference, fasting lipid profile, and fasting glucose is often enough for basic maternal health surveillance, he said.

Dr. Saade said he and some other experts in the field are recommending yearly follow-up for patients who’ve had preeclampsia and other complications. Among the other experts urging early heart disease risk screening is Graeme N. Smith, MD, PhD, an ob.gyn in Ontario who has developed surveillance protocols, follow-up forms, and risk prediction tools for use in a maternal health clinic he established at Kingston General Hospital, Queens University. At the meeting, Dr. Saade encouraged the audience to access Dr. Smith’s resources.

The American Heart Association, in its 2011 guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women, includes pregnancy risks factors (specifically a history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or pregnancy-induced hypertension) as part of its list of major factors for use in risk assessment (Circulation. 2011;123:1243-62).

But as Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MPH, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s division of research, pointed out during another presentation at the meeting, there is more work to be done. Reproductive history is not included in existing disease prediction or risk stratification models for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, making it hard at this point to devise specific screening protocols and schedules, especially when it comes to a history of GDM, she said.

“We need more coordinated systems, surveillance in younger women, and some prediction models so that we can know who is at highest risk and needs more surveillance,” she said.

The AHA’s inclusion of GDM history is based on its strong link to overt diabetes, but recent evidence has shown that a history of GDM can independently elevate cardiovascular risk, she noted. Research from the Nurses Health Study II cohort, for instance, found a 30% higher relative risk of cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction and stroke) in women with a history of GDM without progression to diabetes, compared with women who did not have GDM or diabetes (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1735-42).

Dr. Gunderson has also found through analyses of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study data that women who had GDM but did not go on to develop overt diabetes or impaired glycemia had greater carotid intima media thickness many years post delivery than did women without a history of gestational diabetes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3[2]:e000490).

In some models, she has written, this difference in carotid intima media thickness could represent 3-5 years of greater vascular aging for women with previous gestational diabetes and no apparent metabolic dysfunction outside of pregnancy (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1742-4).

There’s a question, she and Dr. Saade both noted, of whether pregnancies unmask previous dispositions to cardiovascular disease or whether pregnancy complications more directly drive adverse long-term outcomes. There is evidence that disorders such as GDM, Dr. Gunderson said, are superimposed on already altered metabolism. But at this time, Dr. Saade said, it appears that “the answer is both.”

According to Dr. Saade, at least three studies are currently following women prospectively to learn more about pregnancy as a window to future cardiovascular health. One of them is the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study–Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Heart Health Study; some data from this study will be presented soon, he said.

Both Dr. Saade and Dr. Gunderson reported in their presentations that they had no disclosures.

WASHINGTON – George R. Saade, MD, wants to see a Time magazine cover story like the 2010 feature titled, “How the first 9 months shape the rest of your life” – except this new story would read “How the first 9 months shape the rest of the mother’s life.”

It’s time, he says, that pregnancy truly be appreciated as a “window to future health” for the mother as well as for the baby, and that the term “maternal care” replaces prenatal care. “How many of your [primary care] providers have asked you if you’ve had any pregnancies and if any of your pregnancies were complicated by hypertension, preterm delivery, growth restriction, or gestational diabetes?” Dr. Saade asked at the biennial meeting of the Diabetes in Pregnancy Study Group of North America.

“It’s better than before, but not good enough ... Checking with patients 6 weeks postpartum is not enough” to prevent long-term metabolic and cardiovascular disorders, he said. “We need regular screening of women.”

The relationship between gestational diabetes (GDM) and subsequent type 2 diabetes, demonstrated several decades ago, offered the “first evidence that pregnancy is a window to future health,” and evidence of the relationship continues to grow. “We know today that there is no other predictive marker of type 2 diabetes that is better and stronger than gestational diabetes,” said Dr. Saade, chief of obstetrics and maternal-fetal medicine at the University of Texas Medical Branch, Galveston.

GDM has also recently been shown to elevate cardiovascular risk independent of its association with type 2 diabetes and metabolic disease.

And similarly, there is now an incontrovertible body of evidence that women who have had preeclampsia are at significantly higher risk of developing hypertension, stroke, and ischemic heart disease later in life than are women who have not have preeclampsia, Dr. Saade said.

Layered evidence

The study that first caught Dr. Saade’s attention was a large Norwegian population-based study published in 2001 that looked at maternal mortality up to 25 years after pregnancy. Women who had preeclampsia had a 1.2-fold higher long-term risk of death from cardiovascular diseases, cancer, and stroke – and women with a history of both preeclampsia and a preterm delivery had a 2.71-fold higher risk – than that of women without such history.

Looking at cardiovascular causes of death specifically, the risk among women with both preeclampsia and preterm delivery was 8.12-fold higher than in women who did not have preeclampsia.

Since then, studies and reviews conducted in the United States and Europe have shown that a history of preeclampsia doubles the risk of developing cardiovascular disease, more than triples the risk of later hypertension, and also increases the risk of stroke, though more moderately.

Recently, Dr. Saade said, researchers have also begun reporting subclinical cardiac abnormalities in women with a history of preeclampsia. A study of 107 women with preeclampsia and 41 women with uneventful pregnancies found that the prevalence of subclinical heart failure (heart failure Stage B) was approximately 3.5% higher in the short term in the preeclampsia group. The women underwent regular cardiac ultrasound and other cardiovascular risk assessment tests 4-10 years postpartum (Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2017;49[1]:143-9).

Preterm delivery and small for gestational age have also been associated with increased risk of ischemic heart disease and other cardiovascular events later in life. And gestational hypertension, research has shown, is a clear risk factor for later hypertension. “We always think of preeclampsia as a different disease, but as far as long-term health is concerned, it doesn’t matter if a woman had preeclampsia or gestational hypertension; she’s still at [greater] risk for hypertension later,” Dr. Saade said.

“And we don’t have to wait 30 years to see evidence” of the association between pregnancy complications and adverse cardiovascular outcomes, he emphasized. A recent retrospective cohort study of more than 300,000 women in Florida showed that women who experienced a maternal placental syndrome during their first pregnancy were at higher risk of subsequent cardiovascular disease during just 5 years of follow-up (Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2016;215[4]:484.e1-14).

Into practice

Regular screening of women whose pregnancies were complicated by conditions associated with long-term health risks “need not be that sophisticated,” Dr. Saade said. Measurement of blood pressure, waist circumference, fasting lipid profile, and fasting glucose is often enough for basic maternal health surveillance, he said.

Dr. Saade said he and some other experts in the field are recommending yearly follow-up for patients who’ve had preeclampsia and other complications. Among the other experts urging early heart disease risk screening is Graeme N. Smith, MD, PhD, an ob.gyn in Ontario who has developed surveillance protocols, follow-up forms, and risk prediction tools for use in a maternal health clinic he established at Kingston General Hospital, Queens University. At the meeting, Dr. Saade encouraged the audience to access Dr. Smith’s resources.

The American Heart Association, in its 2011 guidelines for cardiovascular disease prevention in women, includes pregnancy risks factors (specifically a history of preeclampsia, gestational diabetes, or pregnancy-induced hypertension) as part of its list of major factors for use in risk assessment (Circulation. 2011;123:1243-62).

But as Erica P. Gunderson, PhD, MPH, of Kaiser Permanente Northern California’s division of research, pointed out during another presentation at the meeting, there is more work to be done. Reproductive history is not included in existing disease prediction or risk stratification models for atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, making it hard at this point to devise specific screening protocols and schedules, especially when it comes to a history of GDM, she said.

“We need more coordinated systems, surveillance in younger women, and some prediction models so that we can know who is at highest risk and needs more surveillance,” she said.

The AHA’s inclusion of GDM history is based on its strong link to overt diabetes, but recent evidence has shown that a history of GDM can independently elevate cardiovascular risk, she noted. Research from the Nurses Health Study II cohort, for instance, found a 30% higher relative risk of cardiovascular events (myocardial infarction and stroke) in women with a history of GDM without progression to diabetes, compared with women who did not have GDM or diabetes (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1735-42).

Dr. Gunderson has also found through analyses of the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults study data that women who had GDM but did not go on to develop overt diabetes or impaired glycemia had greater carotid intima media thickness many years post delivery than did women without a history of gestational diabetes (J Am Heart Assoc. 2014;3[2]:e000490).

In some models, she has written, this difference in carotid intima media thickness could represent 3-5 years of greater vascular aging for women with previous gestational diabetes and no apparent metabolic dysfunction outside of pregnancy (JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177[12]:1742-4).

There’s a question, she and Dr. Saade both noted, of whether pregnancies unmask previous dispositions to cardiovascular disease or whether pregnancy complications more directly drive adverse long-term outcomes. There is evidence that disorders such as GDM, Dr. Gunderson said, are superimposed on already altered metabolism. But at this time, Dr. Saade said, it appears that “the answer is both.”

According to Dr. Saade, at least three studies are currently following women prospectively to learn more about pregnancy as a window to future cardiovascular health. One of them is the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s Nulliparous Pregnancy Outcomes Study–Monitoring Mothers-to-Be Heart Health Study; some data from this study will be presented soon, he said.

Both Dr. Saade and Dr. Gunderson reported in their presentations that they had no disclosures.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM DPSG-NA 2017

Minimally Invasive Anatomical Reconstruction of Posteromedial Corner of Knee: A Cadaveric Study

Take-Home Points

- Injuries to the medial knee are the most common knee ligament injuries, and often occur in the athletic population.

- Complete posteromedial corner injuries require surgical treatment to restore joint stability and biomechanics.

- Biomechanical evidence has demonstrated an important load-sharing distribution between the sMCL and the POL.

- Valgus instability caused by a medial side injury, can lead to both ACL/posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction graft failure if the medial sided injury is not concurrently repaired or reconstructed.

- Anatomic posteromedial corner reconstruction yields excellent biomechanical and patient-reported outcomes.

Most injuries of the medial structures of the knee are treated conservatively.1-3 In severe acute injuries and chronic symptomatic instabilities, however, surgical treatment is needed to restore knee stability and to prevent degenerative changes secondary to instability.4 Three structures involved in medial stability are the superficial medial collateral ligament (sMCL), which is the primary valgus restraint; the posterior oblique ligament (POL), which is the primary restraint to internal rotation and the secondary valgus restraint; and the semimembranosus.5,6

Surgical techniques for posteromedial knee reconstruction include direct repair,7 repair with augmentation,8,9 advancement of the tibial insertion of the sMCL,10 and transfer of the pes anserine tendons.11 In anatomical reconstruction of the posteromedial corner, which has been described before, the sMCL and the POL are reconstructed to reproduce the native motion and stability of the knee.12 Clinically, repair and reconstruction have similar patient-reported outcomes and medial opening evaluations over the short term.

These approaches require large incisions and extensive dissection of soft tissue on the medial aspect of the knee.5 Given these drawbacks, it is reasonable to consider less invasive options. Minimally invasive surgery has the advantages of reduced scarring and blood loss, less disruption of surrounding tissue, faster recovery, and improved aesthetics.4

We conducted a study of a minimally invasive technique for reconstructing the posteromedial structures of the knee. We compared medial compartment stability measured on valgus stress radiographs in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states in cadaveric knees. We hypothesized that a minimally invasive technique using autogenous hamstring graft in the appropriate anatomical location would return valgus stability to its nearly native state.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Buenos Aires British Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora. Ten fresh-frozen cadaveric knees with no evidence of ligamentous injuries, osteoarthritis, or previous surgery were used. Mean donor age was 69.4 years (range, 45-87 years). Each specimen was maintained at room temperature for 24 hours before use. The femur was sectioned 20 cm proximal to the knee joint. The tibia was sectioned 12.5 cm distal to the knee joint.

Identification and Sectioning of Posteromedial Structures

After intact-state evaluation, each knee’s sMCL, dMCL, and POL were sectioned at their tibial insertion. Valgus stress radiograph was repeated and medial compartment gap was remeasured for comparison of the sectioned state with the intact and reconstructed states.

Anatomical Reconstruction With Mini-Invasive Technique

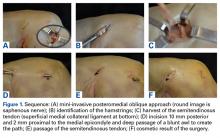

After sectioning of medial stabilizing structures, minimally invasive reconstruction was performed through 2 small incisions on the medial aspect of each of the 10 knees, as follows. First, the semitendinosus tendon was identified through the oblique incision that had been used for sectioning. Then, an open-ended tendon stripper was placed around the circumference of the semitendinosus and was passed proximomedially, transecting the tendon at its musculotendinous junction. While the tendon stripper was being passed, care was taken to maintain the nearby tibial insertion of the sartorius fascia (Figures 1D-1F).

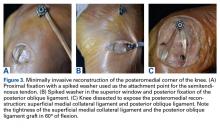

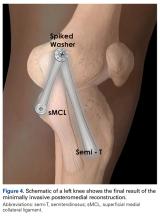

With the semitendinosus tendon looped around the wire, isometricity was tested by pulling the suture within the tendon and moving the knee through a full range of motion. The isometric point was confirmed by tendon migration of <2 mm.13 Migration was measured by marking the graft 2 mm from its insertion; the graft was then pulled to ensure correct isometric point position. An 18-mm cannulated spiked screw and washer (Arthrex) were then passed over the wire and partially secured to the femur—the attachment point for the proximal sMCL portion of the semitendinosus graft. The semitendinosus tendon was then secured beneath the spiked washer with the knee in 20° of flexion with neutral rotation, recreating the sMCL.

Posteriorly, the distal insertion site of the POL was identified at the posteromedial aspect of the tibia through the oblique incision previously described. A 7-mm tunnel was drilled starting posteromedial (10 mm under tibial articular surface) and exiting just distal and medial to the Gerdy tubercle.

After final fixation, the medial knee was openly dissected to assess the inverted-V ligament reconstruction for anatomical placement and avoidance of crucial structures.

Stability Testing

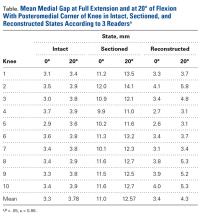

Per International Knee Documentation Committee guidelines for stressing the medial compartment,14 valgus stress radiographs were obtained for all specimens at 0° and 20° of flexion in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states.

The medial gap formed by the femoral condyle and its corresponding tibial plateau (at site of maximal separation) was tested in all 3 state conditions (intact, sectioned, reconstructed). Distances were digitally measured with a picture archiving and communication system viewer (Imagecast; IDX Systems Corporation). Medial gap was measured by taking the shortest distance between the subchondral bone surface of the most distal aspect of the medial femoral condyle and the corresponding medial tibial plateau. Three independent examiners took all the measurements; each examiner was blinded to the others’ measurements.

Statistics

Paired Student t tests were used to compare the 3 conditions, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for a normally distributed population. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad software.

Results

In all 10 specimens, the sMCL, the dMCL, and the POL were successfully identified and sectioned through a medial oblique incision over the distal insertion of the structures.

During all valgus testing states, there was no loss of graft fixation, and there was no gross graft slippage. In addition, all grafts remained in continuity with no evidence of failure, and there were no failures or breakages of the proximal or distal screw.

After posteromedial sectioning, mean medial gap was statistically significantly larger (P = .0002) at full extension (11 mm vs 3.3 mm) and at 20° of flexion (12.6 mm vs 3.8 mm). There was no statistically significant difference between the value of the intact state and the value after minimally invasive reconstruction at 0° (P = .56) or 20° (P = .102) of flexion.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a minimally invasive technique for anatomical posteromedial reconstruction of the knee in a cadaveric model. This technique restores the knee’s native valgus stability without causing extensive damage to the surrounding soft tissues and thereby potentially prevents scar formation and reduces blood loss.

Superficial MCL injury, one of the most common knee ligament injuries, is often associated with POL injury.7 Although most sMCL injuries are treated nonoperatively, with good results,3 surgical treatment is needed for severe (grade III) instabilities, symptomatic chronic instabilities, and knee dislocations.12,17 Most posteromedial reconstruction techniques require an extensive approach that causes damage to surrounding soft tissue,6,7,9,10 which in turn may compromise healing and positive patient outcomes. Surgical techniques include direct repair with sutures or anchors,18 capsular procedures,19 augmentations,9 internal bracing,6 and complete reconstruction of the posteromedial corner.20

LaPrade and Wijdicks12 have previously described anatomical reconstruction of the posteromedial corner. In their technique, a split semitendinosus autograft is used to reconstruct the sMCL and the POL separately, using 4 implants and reproducing each ligament’s anatomical attachment site. In this proposed technique, the distal attachment of the semitendinosus insertion is left intact, and uses 1 attachment point on the distal femur and 1 on the proximal tibia, allowing use of only 2 implants. In addition, it is performed with a minimally invasive approach, reduces cost, limits surgical exposure, and with experience may shorten operative time. To reduce the graft failure rate, the technique of LaPrade and Wijdicks12 positions the sMCL tibial attachment as posterior as possible, which can be performed with this minimally invasive approach as well.

To reduce the graft failure rate, the technique of LaPrade and Wijdicks12 positions the sMCL as posterior as possible. Despite the potential for increased graft stress with an anterior position, as in our modified technique, our group of 10 knees had no graft fixation failures in isolated valgus stress testing in either extension or flexion. Our minimally invasive posteromedial knee reconstruction significantly improved knee stability over the sectioned state as well as medial compartment gapping with valgus stress. There was no significant difference in medial compartment gapping between the intact and reconstructed states.

Our technique was built on open procedures (described by Kim and colleagues13) that carefully identify the isometric point of the graft. In addition, it adopted the modification (proposed by Lind and colleagues21) in which a fixation point is added at the distal insertion of the POL instead of being sutured to the direct arm of the semitendinosus tendon.

Furthermore, our technique, despite being similar to those described by Dong and colleagues22 and Borden and colleagues,23 has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery and reduced disruption of soft tissues. Dong and colleagues22 reported on 64 patients with a mean follow-up of 34 months; patients’ medial opening measurements were significantly decreased at follow-up and fell within the normal range.

The present study had several limitations. First, the age of our specimens was higher than the mean age of patients with knee ligament injury, potentially leading to firmer or more fibrotic tendons less susceptible to elongation. Second, we did not evaluate the knees’ rotational stability, and anterior cruciate ligaments (ACLs) were intact. As most posteromedial injuries co-occur with ACL injuries, a more realistic situation would have been reproduced by assessing rotational stability while performing both ACL reconstruction and the proposed posteromedial reconstruction. Third, static specimen measurements do not reflect the dynamic function of the posteromedial corner. Prospective clinical studies are needed to assess the true effectiveness of the posteromedial corner in the clinical scenario.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the medial aspect of the knee is vital to reconstruction of the medial side of the knee. Our results suggest that a minimally invasive technique can restore valgus stability without the need for extensive dissection and disruption of surrounding soft tissues. More research is needed to determine the results of this technique in vivo.

1. Ellsasser JC, Reynolds FC, Omohundro JR. The non-operative treatment of collateral ligament injuries of the knee in professional football players. An analysis of seventy-four injuries treated non-operatively and twenty-four injuries treated surgically. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56(6):1185-1190.

2. Indelicato PA. Non-operative treatment of complete tears of the medial collateral ligament of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1983;65(3):323-329.

3. Indelicato PA, Hermansdorfer J, Huegel M. Nonoperative management of complete tears of the medial collateral ligament of the knee in intercollegiate football players. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1990;(256):174-177.

4. Jeng CL, Bluman EM, Myerson MS. Minimally invasive deltoid ligament reconstruction for stage IV flatfoot deformity. Foot Ankle Int. 2011;32(1):21-30.

5. Coobs BR, Wijdicks CA, Armitage BM, et al. An in vitro analysis of an anatomical medial knee reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2010;38(2):339-347.

6. Lubowitz JH, MacKay G, Gilmer B. Knee medial collateral ligament and posteromedial corner anatomic repair with internal bracing. Arthrosc Tech. 2014;3(4):e505-e508.

7. Hughston JC, Eilers AF. The role of the posterior oblique ligament in repairs of acute medial (collateral) ligament tears of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55(5):923-940.

8. Gorin S, Paul DD, Wilkinson EJ. An anterior cruciate ligament and medial collateral ligament tear in a skeletally immature patient: a new technique to augment primary repair of the medial collateral ligament and an allograft reconstruction of the anterior cruciate ligament. Arthroscopy. 2003;19(10):E21-E26.

Take-Home Points

- Injuries to the medial knee are the most common knee ligament injuries, and often occur in the athletic population.

- Complete posteromedial corner injuries require surgical treatment to restore joint stability and biomechanics.

- Biomechanical evidence has demonstrated an important load-sharing distribution between the sMCL and the POL.

- Valgus instability caused by a medial side injury, can lead to both ACL/posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction graft failure if the medial sided injury is not concurrently repaired or reconstructed.

- Anatomic posteromedial corner reconstruction yields excellent biomechanical and patient-reported outcomes.

Most injuries of the medial structures of the knee are treated conservatively.1-3 In severe acute injuries and chronic symptomatic instabilities, however, surgical treatment is needed to restore knee stability and to prevent degenerative changes secondary to instability.4 Three structures involved in medial stability are the superficial medial collateral ligament (sMCL), which is the primary valgus restraint; the posterior oblique ligament (POL), which is the primary restraint to internal rotation and the secondary valgus restraint; and the semimembranosus.5,6

Surgical techniques for posteromedial knee reconstruction include direct repair,7 repair with augmentation,8,9 advancement of the tibial insertion of the sMCL,10 and transfer of the pes anserine tendons.11 In anatomical reconstruction of the posteromedial corner, which has been described before, the sMCL and the POL are reconstructed to reproduce the native motion and stability of the knee.12 Clinically, repair and reconstruction have similar patient-reported outcomes and medial opening evaluations over the short term.

These approaches require large incisions and extensive dissection of soft tissue on the medial aspect of the knee.5 Given these drawbacks, it is reasonable to consider less invasive options. Minimally invasive surgery has the advantages of reduced scarring and blood loss, less disruption of surrounding tissue, faster recovery, and improved aesthetics.4

We conducted a study of a minimally invasive technique for reconstructing the posteromedial structures of the knee. We compared medial compartment stability measured on valgus stress radiographs in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states in cadaveric knees. We hypothesized that a minimally invasive technique using autogenous hamstring graft in the appropriate anatomical location would return valgus stability to its nearly native state.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Buenos Aires British Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora. Ten fresh-frozen cadaveric knees with no evidence of ligamentous injuries, osteoarthritis, or previous surgery were used. Mean donor age was 69.4 years (range, 45-87 years). Each specimen was maintained at room temperature for 24 hours before use. The femur was sectioned 20 cm proximal to the knee joint. The tibia was sectioned 12.5 cm distal to the knee joint.

Identification and Sectioning of Posteromedial Structures

After intact-state evaluation, each knee’s sMCL, dMCL, and POL were sectioned at their tibial insertion. Valgus stress radiograph was repeated and medial compartment gap was remeasured for comparison of the sectioned state with the intact and reconstructed states.

Anatomical Reconstruction With Mini-Invasive Technique

After sectioning of medial stabilizing structures, minimally invasive reconstruction was performed through 2 small incisions on the medial aspect of each of the 10 knees, as follows. First, the semitendinosus tendon was identified through the oblique incision that had been used for sectioning. Then, an open-ended tendon stripper was placed around the circumference of the semitendinosus and was passed proximomedially, transecting the tendon at its musculotendinous junction. While the tendon stripper was being passed, care was taken to maintain the nearby tibial insertion of the sartorius fascia (Figures 1D-1F).

With the semitendinosus tendon looped around the wire, isometricity was tested by pulling the suture within the tendon and moving the knee through a full range of motion. The isometric point was confirmed by tendon migration of <2 mm.13 Migration was measured by marking the graft 2 mm from its insertion; the graft was then pulled to ensure correct isometric point position. An 18-mm cannulated spiked screw and washer (Arthrex) were then passed over the wire and partially secured to the femur—the attachment point for the proximal sMCL portion of the semitendinosus graft. The semitendinosus tendon was then secured beneath the spiked washer with the knee in 20° of flexion with neutral rotation, recreating the sMCL.

Posteriorly, the distal insertion site of the POL was identified at the posteromedial aspect of the tibia through the oblique incision previously described. A 7-mm tunnel was drilled starting posteromedial (10 mm under tibial articular surface) and exiting just distal and medial to the Gerdy tubercle.

After final fixation, the medial knee was openly dissected to assess the inverted-V ligament reconstruction for anatomical placement and avoidance of crucial structures.

Stability Testing

Per International Knee Documentation Committee guidelines for stressing the medial compartment,14 valgus stress radiographs were obtained for all specimens at 0° and 20° of flexion in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states.

The medial gap formed by the femoral condyle and its corresponding tibial plateau (at site of maximal separation) was tested in all 3 state conditions (intact, sectioned, reconstructed). Distances were digitally measured with a picture archiving and communication system viewer (Imagecast; IDX Systems Corporation). Medial gap was measured by taking the shortest distance between the subchondral bone surface of the most distal aspect of the medial femoral condyle and the corresponding medial tibial plateau. Three independent examiners took all the measurements; each examiner was blinded to the others’ measurements.

Statistics

Paired Student t tests were used to compare the 3 conditions, and the Shapiro-Wilk test was used to check for a normally distributed population. Statistical significance was set at P < .05. Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad software.

Results

In all 10 specimens, the sMCL, the dMCL, and the POL were successfully identified and sectioned through a medial oblique incision over the distal insertion of the structures.

During all valgus testing states, there was no loss of graft fixation, and there was no gross graft slippage. In addition, all grafts remained in continuity with no evidence of failure, and there were no failures or breakages of the proximal or distal screw.

After posteromedial sectioning, mean medial gap was statistically significantly larger (P = .0002) at full extension (11 mm vs 3.3 mm) and at 20° of flexion (12.6 mm vs 3.8 mm). There was no statistically significant difference between the value of the intact state and the value after minimally invasive reconstruction at 0° (P = .56) or 20° (P = .102) of flexion.

Discussion

In this article, we describe a minimally invasive technique for anatomical posteromedial reconstruction of the knee in a cadaveric model. This technique restores the knee’s native valgus stability without causing extensive damage to the surrounding soft tissues and thereby potentially prevents scar formation and reduces blood loss.

Superficial MCL injury, one of the most common knee ligament injuries, is often associated with POL injury.7 Although most sMCL injuries are treated nonoperatively, with good results,3 surgical treatment is needed for severe (grade III) instabilities, symptomatic chronic instabilities, and knee dislocations.12,17 Most posteromedial reconstruction techniques require an extensive approach that causes damage to surrounding soft tissue,6,7,9,10 which in turn may compromise healing and positive patient outcomes. Surgical techniques include direct repair with sutures or anchors,18 capsular procedures,19 augmentations,9 internal bracing,6 and complete reconstruction of the posteromedial corner.20

LaPrade and Wijdicks12 have previously described anatomical reconstruction of the posteromedial corner. In their technique, a split semitendinosus autograft is used to reconstruct the sMCL and the POL separately, using 4 implants and reproducing each ligament’s anatomical attachment site. In this proposed technique, the distal attachment of the semitendinosus insertion is left intact, and uses 1 attachment point on the distal femur and 1 on the proximal tibia, allowing use of only 2 implants. In addition, it is performed with a minimally invasive approach, reduces cost, limits surgical exposure, and with experience may shorten operative time. To reduce the graft failure rate, the technique of LaPrade and Wijdicks12 positions the sMCL tibial attachment as posterior as possible, which can be performed with this minimally invasive approach as well.

To reduce the graft failure rate, the technique of LaPrade and Wijdicks12 positions the sMCL as posterior as possible. Despite the potential for increased graft stress with an anterior position, as in our modified technique, our group of 10 knees had no graft fixation failures in isolated valgus stress testing in either extension or flexion. Our minimally invasive posteromedial knee reconstruction significantly improved knee stability over the sectioned state as well as medial compartment gapping with valgus stress. There was no significant difference in medial compartment gapping between the intact and reconstructed states.

Our technique was built on open procedures (described by Kim and colleagues13) that carefully identify the isometric point of the graft. In addition, it adopted the modification (proposed by Lind and colleagues21) in which a fixation point is added at the distal insertion of the POL instead of being sutured to the direct arm of the semitendinosus tendon.

Furthermore, our technique, despite being similar to those described by Dong and colleagues22 and Borden and colleagues,23 has the advantages of minimally invasive surgery and reduced disruption of soft tissues. Dong and colleagues22 reported on 64 patients with a mean follow-up of 34 months; patients’ medial opening measurements were significantly decreased at follow-up and fell within the normal range.

The present study had several limitations. First, the age of our specimens was higher than the mean age of patients with knee ligament injury, potentially leading to firmer or more fibrotic tendons less susceptible to elongation. Second, we did not evaluate the knees’ rotational stability, and anterior cruciate ligaments (ACLs) were intact. As most posteromedial injuries co-occur with ACL injuries, a more realistic situation would have been reproduced by assessing rotational stability while performing both ACL reconstruction and the proposed posteromedial reconstruction. Third, static specimen measurements do not reflect the dynamic function of the posteromedial corner. Prospective clinical studies are needed to assess the true effectiveness of the posteromedial corner in the clinical scenario.

Knowledge of the anatomy of the medial aspect of the knee is vital to reconstruction of the medial side of the knee. Our results suggest that a minimally invasive technique can restore valgus stability without the need for extensive dissection and disruption of surrounding soft tissues. More research is needed to determine the results of this technique in vivo.

Take-Home Points

- Injuries to the medial knee are the most common knee ligament injuries, and often occur in the athletic population.

- Complete posteromedial corner injuries require surgical treatment to restore joint stability and biomechanics.

- Biomechanical evidence has demonstrated an important load-sharing distribution between the sMCL and the POL.

- Valgus instability caused by a medial side injury, can lead to both ACL/posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction graft failure if the medial sided injury is not concurrently repaired or reconstructed.

- Anatomic posteromedial corner reconstruction yields excellent biomechanical and patient-reported outcomes.

Most injuries of the medial structures of the knee are treated conservatively.1-3 In severe acute injuries and chronic symptomatic instabilities, however, surgical treatment is needed to restore knee stability and to prevent degenerative changes secondary to instability.4 Three structures involved in medial stability are the superficial medial collateral ligament (sMCL), which is the primary valgus restraint; the posterior oblique ligament (POL), which is the primary restraint to internal rotation and the secondary valgus restraint; and the semimembranosus.5,6

Surgical techniques for posteromedial knee reconstruction include direct repair,7 repair with augmentation,8,9 advancement of the tibial insertion of the sMCL,10 and transfer of the pes anserine tendons.11 In anatomical reconstruction of the posteromedial corner, which has been described before, the sMCL and the POL are reconstructed to reproduce the native motion and stability of the knee.12 Clinically, repair and reconstruction have similar patient-reported outcomes and medial opening evaluations over the short term.

These approaches require large incisions and extensive dissection of soft tissue on the medial aspect of the knee.5 Given these drawbacks, it is reasonable to consider less invasive options. Minimally invasive surgery has the advantages of reduced scarring and blood loss, less disruption of surrounding tissue, faster recovery, and improved aesthetics.4

We conducted a study of a minimally invasive technique for reconstructing the posteromedial structures of the knee. We compared medial compartment stability measured on valgus stress radiographs in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states in cadaveric knees. We hypothesized that a minimally invasive technique using autogenous hamstring graft in the appropriate anatomical location would return valgus stability to its nearly native state.

Materials and Methods

This study was conducted at the Buenos Aires British Hospital in Buenos Aires, Argentina, and at the University of Colorado Hospital in Aurora. Ten fresh-frozen cadaveric knees with no evidence of ligamentous injuries, osteoarthritis, or previous surgery were used. Mean donor age was 69.4 years (range, 45-87 years). Each specimen was maintained at room temperature for 24 hours before use. The femur was sectioned 20 cm proximal to the knee joint. The tibia was sectioned 12.5 cm distal to the knee joint.

Identification and Sectioning of Posteromedial Structures

After intact-state evaluation, each knee’s sMCL, dMCL, and POL were sectioned at their tibial insertion. Valgus stress radiograph was repeated and medial compartment gap was remeasured for comparison of the sectioned state with the intact and reconstructed states.

Anatomical Reconstruction With Mini-Invasive Technique

After sectioning of medial stabilizing structures, minimally invasive reconstruction was performed through 2 small incisions on the medial aspect of each of the 10 knees, as follows. First, the semitendinosus tendon was identified through the oblique incision that had been used for sectioning. Then, an open-ended tendon stripper was placed around the circumference of the semitendinosus and was passed proximomedially, transecting the tendon at its musculotendinous junction. While the tendon stripper was being passed, care was taken to maintain the nearby tibial insertion of the sartorius fascia (Figures 1D-1F).

With the semitendinosus tendon looped around the wire, isometricity was tested by pulling the suture within the tendon and moving the knee through a full range of motion. The isometric point was confirmed by tendon migration of <2 mm.13 Migration was measured by marking the graft 2 mm from its insertion; the graft was then pulled to ensure correct isometric point position. An 18-mm cannulated spiked screw and washer (Arthrex) were then passed over the wire and partially secured to the femur—the attachment point for the proximal sMCL portion of the semitendinosus graft. The semitendinosus tendon was then secured beneath the spiked washer with the knee in 20° of flexion with neutral rotation, recreating the sMCL.

Posteriorly, the distal insertion site of the POL was identified at the posteromedial aspect of the tibia through the oblique incision previously described. A 7-mm tunnel was drilled starting posteromedial (10 mm under tibial articular surface) and exiting just distal and medial to the Gerdy tubercle.

After final fixation, the medial knee was openly dissected to assess the inverted-V ligament reconstruction for anatomical placement and avoidance of crucial structures.

Stability Testing

Per International Knee Documentation Committee guidelines for stressing the medial compartment,14 valgus stress radiographs were obtained for all specimens at 0° and 20° of flexion in intact, sectioned, and reconstructed states.