User login

Combo improves outcomes in MCL

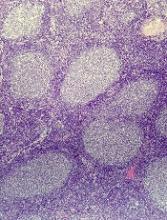

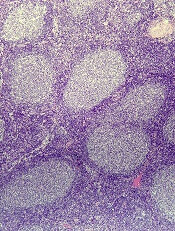

A 2-drug combination can improve outcomes in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 2 trial of MCL patients, the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax produced an overall response rate of 71% and a complete response (CR) rate of 62%.

“This was in patients who we expected to have a poor outcome on conventional therapy, and in which treatment with either ibrutinib or venetoclax alone was expected to see only 21% of patients show a complete response,” said Constantine Tam, MBBS, MD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in patients receiving venetoclax and ibrutinib were diarrhea (83%), fatigue (75%), and nausea/vomiting (71%). Fourteen patients (58%) had serious AEs, including 2 with tumor lysis syndrome.

Dr Tam and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 24 patients—23 with relapsed/refractory MCL and 1 with previously untreated MCL. They had a median age of 68 (range, 47-81).

Most patients had high-risk (75%) or intermediate-risk (21%) disease, according to the MCL International Prognostic Index. Half of patients (including the previously untreated patient) had a TP53 aberration, and 25% had an NF-κB pathway mutation.

The relapsed/refractory patients had a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-6), and 48% were refractory to their most recent therapy.

Patients received ibrutinib monotherapy at 560 mg daily for 4 weeks. Then, patients began receiving venetoclax as well, in increasing doses, up to 400 mg per day. Patients received treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was CR at week 16, as assessed without PET. This was to allow the researchers to compare CR results in this trial to CR results in the PCYC-1104-CA study, a phase 2 trial of ibrutinib monotherapy in MCL.

According to CT, the CR rate was 42% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib. This is significantly higher than the 9% CR rate observed in the patients treated with ibrutinib alone (P<0.001).

However, according to PET/CT, the 16-week CR rate was 62% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib, and the overall response rate was 71%.

Overall, the rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity was 67% (n=16) in the bone marrow according to flow cytometry and 38% (n=9) in the blood according to allele-specific oligonucleotide-polymerase chain reaction (ASO-PCR). However, not all patients were evaluable for MRD.

Among evaluable patients with a CR, 93% (14/15) were MRD negative according to flow cytometry, and 82% (9/11) were negative according to ASO-PCR.

The median progression-free survival was not reached at a median follow-up of 15.9 months. The estimated progression-free survival was 75% at 12 months and 57% at 18 months.

The rate of overall survival was 79% at 12 months and 74% at 18 months.

“These very promising results have triggered additional and larger studies to better understand the synergistic benefits of the venetoclax-ibrutinib treatment combination in MCL patients,” Dr Tam said.

Safety

The most common AEs were diarrhea (83%); fatigue (75%); nausea/vomiting (71%); bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (54%); musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (50%); cough or dyspnea (46%); soft-tissue infection (42%); upper respiratory tract infection (42%); neutropenia (33%); and lower respiratory tract infection (33%).

Grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (33%), thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (12%), diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), lower respiratory tract infection (8%), soft-tissue infection (8%), cough or dyspnea (4%), musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (4%), and bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (4%).

Serious AEs included diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), pyrexia (8%), pleural effusion (8%), cardiac failure (4%), and soft-tissue infection (4%).

The patients who developed tumor lysis syndrome were among the first 15 patients who started venetoclax at a dose of 50 mg per day. Because of these cases, the study protocol was amended to lower the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg daily. After that, there were no additional cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

There were 6 deaths during the study. Four were attributed to disease progression, 1 to malignant otitis externa, and 1 to cardiac failure in a patient in CR.

A 2-drug combination can improve outcomes in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 2 trial of MCL patients, the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax produced an overall response rate of 71% and a complete response (CR) rate of 62%.

“This was in patients who we expected to have a poor outcome on conventional therapy, and in which treatment with either ibrutinib or venetoclax alone was expected to see only 21% of patients show a complete response,” said Constantine Tam, MBBS, MD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in patients receiving venetoclax and ibrutinib were diarrhea (83%), fatigue (75%), and nausea/vomiting (71%). Fourteen patients (58%) had serious AEs, including 2 with tumor lysis syndrome.

Dr Tam and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 24 patients—23 with relapsed/refractory MCL and 1 with previously untreated MCL. They had a median age of 68 (range, 47-81).

Most patients had high-risk (75%) or intermediate-risk (21%) disease, according to the MCL International Prognostic Index. Half of patients (including the previously untreated patient) had a TP53 aberration, and 25% had an NF-κB pathway mutation.

The relapsed/refractory patients had a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-6), and 48% were refractory to their most recent therapy.

Patients received ibrutinib monotherapy at 560 mg daily for 4 weeks. Then, patients began receiving venetoclax as well, in increasing doses, up to 400 mg per day. Patients received treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was CR at week 16, as assessed without PET. This was to allow the researchers to compare CR results in this trial to CR results in the PCYC-1104-CA study, a phase 2 trial of ibrutinib monotherapy in MCL.

According to CT, the CR rate was 42% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib. This is significantly higher than the 9% CR rate observed in the patients treated with ibrutinib alone (P<0.001).

However, according to PET/CT, the 16-week CR rate was 62% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib, and the overall response rate was 71%.

Overall, the rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity was 67% (n=16) in the bone marrow according to flow cytometry and 38% (n=9) in the blood according to allele-specific oligonucleotide-polymerase chain reaction (ASO-PCR). However, not all patients were evaluable for MRD.

Among evaluable patients with a CR, 93% (14/15) were MRD negative according to flow cytometry, and 82% (9/11) were negative according to ASO-PCR.

The median progression-free survival was not reached at a median follow-up of 15.9 months. The estimated progression-free survival was 75% at 12 months and 57% at 18 months.

The rate of overall survival was 79% at 12 months and 74% at 18 months.

“These very promising results have triggered additional and larger studies to better understand the synergistic benefits of the venetoclax-ibrutinib treatment combination in MCL patients,” Dr Tam said.

Safety

The most common AEs were diarrhea (83%); fatigue (75%); nausea/vomiting (71%); bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (54%); musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (50%); cough or dyspnea (46%); soft-tissue infection (42%); upper respiratory tract infection (42%); neutropenia (33%); and lower respiratory tract infection (33%).

Grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (33%), thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (12%), diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), lower respiratory tract infection (8%), soft-tissue infection (8%), cough or dyspnea (4%), musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (4%), and bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (4%).

Serious AEs included diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), pyrexia (8%), pleural effusion (8%), cardiac failure (4%), and soft-tissue infection (4%).

The patients who developed tumor lysis syndrome were among the first 15 patients who started venetoclax at a dose of 50 mg per day. Because of these cases, the study protocol was amended to lower the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg daily. After that, there were no additional cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

There were 6 deaths during the study. Four were attributed to disease progression, 1 to malignant otitis externa, and 1 to cardiac failure in a patient in CR.

A 2-drug combination can improve outcomes in patients with mantle cell lymphoma (MCL), according to researchers.

In a phase 2 trial of MCL patients, the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib and the BCL2 inhibitor venetoclax produced an overall response rate of 71% and a complete response (CR) rate of 62%.

“This was in patients who we expected to have a poor outcome on conventional therapy, and in which treatment with either ibrutinib or venetoclax alone was expected to see only 21% of patients show a complete response,” said Constantine Tam, MBBS, MD, of the Peter MacCallum Cancer Centre in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia.

The most common adverse events (AEs) in patients receiving venetoclax and ibrutinib were diarrhea (83%), fatigue (75%), and nausea/vomiting (71%). Fourteen patients (58%) had serious AEs, including 2 with tumor lysis syndrome.

Dr Tam and his colleagues reported these results in NEJM.

The study included 24 patients—23 with relapsed/refractory MCL and 1 with previously untreated MCL. They had a median age of 68 (range, 47-81).

Most patients had high-risk (75%) or intermediate-risk (21%) disease, according to the MCL International Prognostic Index. Half of patients (including the previously untreated patient) had a TP53 aberration, and 25% had an NF-κB pathway mutation.

The relapsed/refractory patients had a median of 2 prior therapies (range, 1-6), and 48% were refractory to their most recent therapy.

Patients received ibrutinib monotherapy at 560 mg daily for 4 weeks. Then, patients began receiving venetoclax as well, in increasing doses, up to 400 mg per day. Patients received treatment until progression or unacceptable toxicity.

Efficacy

The study’s primary endpoint was CR at week 16, as assessed without PET. This was to allow the researchers to compare CR results in this trial to CR results in the PCYC-1104-CA study, a phase 2 trial of ibrutinib monotherapy in MCL.

According to CT, the CR rate was 42% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib. This is significantly higher than the 9% CR rate observed in the patients treated with ibrutinib alone (P<0.001).

However, according to PET/CT, the 16-week CR rate was 62% in patients who received venetoclax and ibrutinib, and the overall response rate was 71%.

Overall, the rate of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity was 67% (n=16) in the bone marrow according to flow cytometry and 38% (n=9) in the blood according to allele-specific oligonucleotide-polymerase chain reaction (ASO-PCR). However, not all patients were evaluable for MRD.

Among evaluable patients with a CR, 93% (14/15) were MRD negative according to flow cytometry, and 82% (9/11) were negative according to ASO-PCR.

The median progression-free survival was not reached at a median follow-up of 15.9 months. The estimated progression-free survival was 75% at 12 months and 57% at 18 months.

The rate of overall survival was 79% at 12 months and 74% at 18 months.

“These very promising results have triggered additional and larger studies to better understand the synergistic benefits of the venetoclax-ibrutinib treatment combination in MCL patients,” Dr Tam said.

Safety

The most common AEs were diarrhea (83%); fatigue (75%); nausea/vomiting (71%); bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (54%); musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (50%); cough or dyspnea (46%); soft-tissue infection (42%); upper respiratory tract infection (42%); neutropenia (33%); and lower respiratory tract infection (33%).

Grade 3/4 AEs included neutropenia (33%), thrombocytopenia (17%), anemia (12%), diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), lower respiratory tract infection (8%), soft-tissue infection (8%), cough or dyspnea (4%), musculoskeletal or connective-tissue pain (4%), and bleeding, bruising, or postoperative hemorrhage (4%).

Serious AEs included diarrhea (12%), tumor lysis syndrome (8%), atrial fibrillation (8%), pyrexia (8%), pleural effusion (8%), cardiac failure (4%), and soft-tissue infection (4%).

The patients who developed tumor lysis syndrome were among the first 15 patients who started venetoclax at a dose of 50 mg per day. Because of these cases, the study protocol was amended to lower the starting dose of venetoclax to 20 mg daily. After that, there were no additional cases of tumor lysis syndrome.

There were 6 deaths during the study. Four were attributed to disease progression, 1 to malignant otitis externa, and 1 to cardiac failure in a patient in CR.

Tenalisib receives orphan designation for CTCL

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to tenalisib for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Tenalisib (formerly RP6530) is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor under development by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals SA.

The FDA previously granted tenalisib fast track and orphan drug designations for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib has been investigated in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL and CTCL. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February.

The data included 55 patients—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL—who received varying doses of tenalisib. The maximum tolerated dose was an 800 mg daily fasting dose.

Fourteen PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy, and 7 responded (50%) to treatment. Three patients had a complete response, and 4 had a partial response.

Eighteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients responded (44%), all with partial responses.

In the entire cohort, treatment-related adverse events (AEs) of grade 3 or higher included transaminitis (20%), rash (5%), neutropenia (2%), hypophosphatemia (2%), international normalized ratio increase (2%), sepsis (2%), pyrexia (2%), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%).

Four CTCL patients stopped tenalisib due to a treatment-related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to tenalisib for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Tenalisib (formerly RP6530) is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor under development by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals SA.

The FDA previously granted tenalisib fast track and orphan drug designations for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib has been investigated in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL and CTCL. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February.

The data included 55 patients—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL—who received varying doses of tenalisib. The maximum tolerated dose was an 800 mg daily fasting dose.

Fourteen PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy, and 7 responded (50%) to treatment. Three patients had a complete response, and 4 had a partial response.

Eighteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients responded (44%), all with partial responses.

In the entire cohort, treatment-related adverse events (AEs) of grade 3 or higher included transaminitis (20%), rash (5%), neutropenia (2%), hypophosphatemia (2%), international normalized ratio increase (2%), sepsis (2%), pyrexia (2%), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%).

Four CTCL patients stopped tenalisib due to a treatment-related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has granted orphan drug designation to tenalisib for treatment of cutaneous T-cell lymphoma (CTCL).

Tenalisib (formerly RP6530) is a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor under development by Rhizen Pharmaceuticals SA.

The FDA previously granted tenalisib fast track and orphan drug designations for the treatment of peripheral T-cell lymphoma (PTCL).

Tenalisib has been investigated in a phase 1 trial of patients with relapsed/refractory PTCL and CTCL. Results from this trial were presented at the 10th Annual T-cell Lymphoma Forum in February.

The data included 55 patients—28 with CTCL and 27 with PTCL—who received varying doses of tenalisib. The maximum tolerated dose was an 800 mg daily fasting dose.

Fourteen PTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy, and 7 responded (50%) to treatment. Three patients had a complete response, and 4 had a partial response.

Eighteen CTCL patients were evaluable for efficacy. Eight patients responded (44%), all with partial responses.

In the entire cohort, treatment-related adverse events (AEs) of grade 3 or higher included transaminitis (20%), rash (5%), neutropenia (2%), hypophosphatemia (2%), international normalized ratio increase (2%), sepsis (2%), pyrexia (2%), and diplopia secondary to neuropathy (2%).

Four CTCL patients stopped tenalisib due to a treatment-related AE—transaminitis, sepsis, diarrhea, and diplopia secondary to neuropathy. One PTCL patient stopped treatment due to a related AE, which was transaminitis.

About orphan and fast track designations

The FDA grants orphan designation to products intended to treat, diagnose, or prevent diseases/disorders that affect fewer than 200,000 people in the US.

The designation provides incentives for sponsors to develop products for rare diseases. This may include tax credits toward the cost of clinical trials, prescription drug user fee waivers, and 7 years of market exclusivity if the product is approved.

The FDA’s fast track drug development program is designed to expedite clinical development and submission of new drug applications for medicines with the potential to treat serious or life-threatening conditions and address unmet medical needs.

Fast track designation facilitates frequent interactions with the FDA review team, including meetings to discuss all aspects of development to support a drug’s approval, and also provides the opportunity to submit sections of a new drug application on a rolling basis as data become available.

Duvelisib NDA granted priority review

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the new drug application (NDA) for duvelisib, a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor.

With this NDA, Verastem, Inc., is seeking full approval of duvelisib for the treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and accelerated approval of the drug for the treatment of relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

The FDA expects to make a decision on the NDA by October 5, 2018.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The application for duvelisib is supported by data from DUO™, a randomized, phase 3 study of patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL, and DYNAMO™, a phase 2 study of patients with refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Phase 3 DUO trial

Results from DUO were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

This study included 319 CLL/SLL patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive either duvelisib (25 mg orally twice daily) or ofatumumab (initial infusion of 300 mg followed by 7 weekly infusions and 4 monthly infusions of 2000 mg).

The study’s primary endpoint was met, as duvelisib conferred a significant improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS) over ofatumumab.

Per an independent review committee, the median PFS was 13.3 months with duvelisib and 9.9 months with ofatumumab (hazard ratio=0.52; P<0.0001). Duvelisib maintained a PFS advantage in all patient subgroups analyzed.

The overall response rate was 73.8% with duvelisib and 45.3% with ofatumumab (P<0.0001). The complete response rate was 0.6% in both arms.

Overall survival (OS) was similar in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms (hazard ratio=0.99; P=0.4807). The median OS was not reached in either arm.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs)—in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms, respectively—were neutropenia (30% vs 17%), anemia (13% vs 5%), diarrhea (15% vs 1%), pneumonia (14% vs 1%), and colitis (12% vs 1%).

Thirty-five percent of patients discontinued duvelisib due to an AE.

Severe opportunistic infections occurred in 6% of duvelisib recipients—bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (n=4), fungal infection (n=2), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (n=2), and cytomegalovirus colitis (n=1).

There were 4 deaths related to duvelisib—staphylococcal pneumonia (n=2), general physical health deterioration (n=1), and sepsis (n=1).

Phase 2 DYNAMO trial

Results from DYNAMO were presented at the 22nd EHA Congress (abstract S777) in June 2017.

This trial enrolled patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease was refractory to both rituximab and chemotherapy or radioimmunotherapy.

There were 83 patients with FL. They had a median of 3 prior anticancer regimens (range, 1-10).

The patients received duvelisib at 25 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate, per an independent review committee, was 43%. One patient achieved a complete response, and 35 had a partial response. The median duration of response was 7.9 months.

The median PFS was 8.3 months, and the median OS was 27.8 months.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were neutropenia (22%), anemia (13%), diarrhea (16%), lipase increase (10%), and thrombocytopenia (9%).

There were 2 serious opportunistic infections—Pneumocystis pneumonia and fungal pneumonia.

There were 3 deaths attributed to duvelisib—toxic epidermal necrolysis/sepsis syndrome (n=1), drug reaction/eosinophilia/systemic symptoms (n=1), and pneumonitis/pneumonia (n=1).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the new drug application (NDA) for duvelisib, a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor.

With this NDA, Verastem, Inc., is seeking full approval of duvelisib for the treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and accelerated approval of the drug for the treatment of relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

The FDA expects to make a decision on the NDA by October 5, 2018.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The application for duvelisib is supported by data from DUO™, a randomized, phase 3 study of patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL, and DYNAMO™, a phase 2 study of patients with refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Phase 3 DUO trial

Results from DUO were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

This study included 319 CLL/SLL patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive either duvelisib (25 mg orally twice daily) or ofatumumab (initial infusion of 300 mg followed by 7 weekly infusions and 4 monthly infusions of 2000 mg).

The study’s primary endpoint was met, as duvelisib conferred a significant improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS) over ofatumumab.

Per an independent review committee, the median PFS was 13.3 months with duvelisib and 9.9 months with ofatumumab (hazard ratio=0.52; P<0.0001). Duvelisib maintained a PFS advantage in all patient subgroups analyzed.

The overall response rate was 73.8% with duvelisib and 45.3% with ofatumumab (P<0.0001). The complete response rate was 0.6% in both arms.

Overall survival (OS) was similar in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms (hazard ratio=0.99; P=0.4807). The median OS was not reached in either arm.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs)—in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms, respectively—were neutropenia (30% vs 17%), anemia (13% vs 5%), diarrhea (15% vs 1%), pneumonia (14% vs 1%), and colitis (12% vs 1%).

Thirty-five percent of patients discontinued duvelisib due to an AE.

Severe opportunistic infections occurred in 6% of duvelisib recipients—bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (n=4), fungal infection (n=2), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (n=2), and cytomegalovirus colitis (n=1).

There were 4 deaths related to duvelisib—staphylococcal pneumonia (n=2), general physical health deterioration (n=1), and sepsis (n=1).

Phase 2 DYNAMO trial

Results from DYNAMO were presented at the 22nd EHA Congress (abstract S777) in June 2017.

This trial enrolled patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease was refractory to both rituximab and chemotherapy or radioimmunotherapy.

There were 83 patients with FL. They had a median of 3 prior anticancer regimens (range, 1-10).

The patients received duvelisib at 25 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate, per an independent review committee, was 43%. One patient achieved a complete response, and 35 had a partial response. The median duration of response was 7.9 months.

The median PFS was 8.3 months, and the median OS was 27.8 months.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were neutropenia (22%), anemia (13%), diarrhea (16%), lipase increase (10%), and thrombocytopenia (9%).

There were 2 serious opportunistic infections—Pneumocystis pneumonia and fungal pneumonia.

There were 3 deaths attributed to duvelisib—toxic epidermal necrolysis/sepsis syndrome (n=1), drug reaction/eosinophilia/systemic symptoms (n=1), and pneumonitis/pneumonia (n=1).

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has accepted for priority review the new drug application (NDA) for duvelisib, a dual PI3K delta/gamma inhibitor.

With this NDA, Verastem, Inc., is seeking full approval of duvelisib for the treatment of relapsed or refractory chronic lymphocytic leukemia/small lymphocytic lymphoma (CLL/SLL) and accelerated approval of the drug for the treatment of relapsed or refractory follicular lymphoma (FL).

The FDA expects to make a decision on the NDA by October 5, 2018.

The FDA aims to take action on a priority review application within 6 months of receiving it, rather than the standard 10 months.

The agency grants priority review to applications for products that may provide significant improvements in the treatment, diagnosis, or prevention of serious conditions.

The application for duvelisib is supported by data from DUO™, a randomized, phase 3 study of patients with relapsed or refractory CLL/SLL, and DYNAMO™, a phase 2 study of patients with refractory indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Phase 3 DUO trial

Results from DUO were presented at the 2017 ASH Annual Meeting in December.

This study included 319 CLL/SLL patients who were randomized 1:1 to receive either duvelisib (25 mg orally twice daily) or ofatumumab (initial infusion of 300 mg followed by 7 weekly infusions and 4 monthly infusions of 2000 mg).

The study’s primary endpoint was met, as duvelisib conferred a significant improvement in median progression-free survival (PFS) over ofatumumab.

Per an independent review committee, the median PFS was 13.3 months with duvelisib and 9.9 months with ofatumumab (hazard ratio=0.52; P<0.0001). Duvelisib maintained a PFS advantage in all patient subgroups analyzed.

The overall response rate was 73.8% with duvelisib and 45.3% with ofatumumab (P<0.0001). The complete response rate was 0.6% in both arms.

Overall survival (OS) was similar in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms (hazard ratio=0.99; P=0.4807). The median OS was not reached in either arm.

The most common grade 3 or higher adverse events (AEs)—in the duvelisib and ofatumumab arms, respectively—were neutropenia (30% vs 17%), anemia (13% vs 5%), diarrhea (15% vs 1%), pneumonia (14% vs 1%), and colitis (12% vs 1%).

Thirty-five percent of patients discontinued duvelisib due to an AE.

Severe opportunistic infections occurred in 6% of duvelisib recipients—bronchopulmonary aspergillosis (n=4), fungal infection (n=2), Pneumocystis jirovecii pneumonia (n=2), and cytomegalovirus colitis (n=1).

There were 4 deaths related to duvelisib—staphylococcal pneumonia (n=2), general physical health deterioration (n=1), and sepsis (n=1).

Phase 2 DYNAMO trial

Results from DYNAMO were presented at the 22nd EHA Congress (abstract S777) in June 2017.

This trial enrolled patients with indolent non-Hodgkin lymphoma whose disease was refractory to both rituximab and chemotherapy or radioimmunotherapy.

There were 83 patients with FL. They had a median of 3 prior anticancer regimens (range, 1-10).

The patients received duvelisib at 25 mg orally twice daily until disease progression or unacceptable toxicity.

The overall response rate, per an independent review committee, was 43%. One patient achieved a complete response, and 35 had a partial response. The median duration of response was 7.9 months.

The median PFS was 8.3 months, and the median OS was 27.8 months.

The most common grade 3 or higher AEs were neutropenia (22%), anemia (13%), diarrhea (16%), lipase increase (10%), and thrombocytopenia (9%).

There were 2 serious opportunistic infections—Pneumocystis pneumonia and fungal pneumonia.

There were 3 deaths attributed to duvelisib—toxic epidermal necrolysis/sepsis syndrome (n=1), drug reaction/eosinophilia/systemic symptoms (n=1), and pneumonitis/pneumonia (n=1).

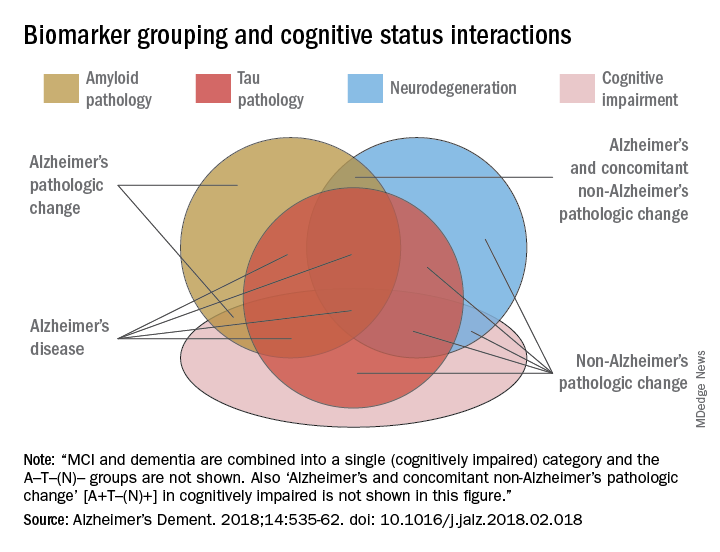

Alzheimer’s: Biomarkers, not cognition, will now define disorder

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

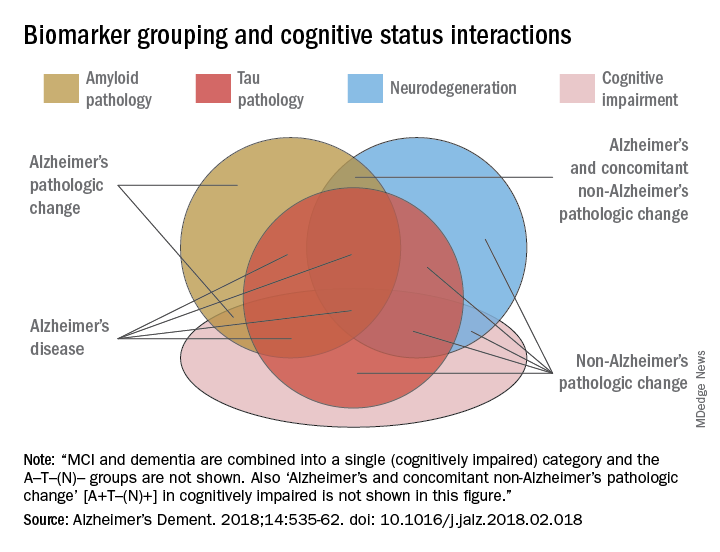

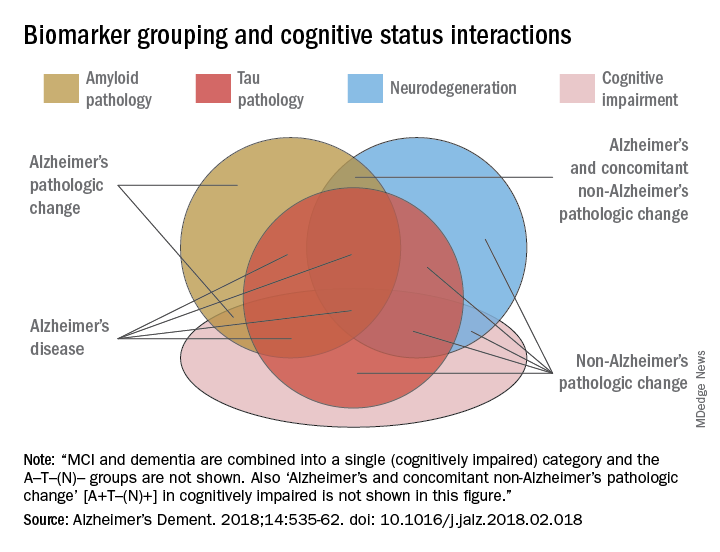

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

FROM ALZHEIMER’S & DEMENTIA

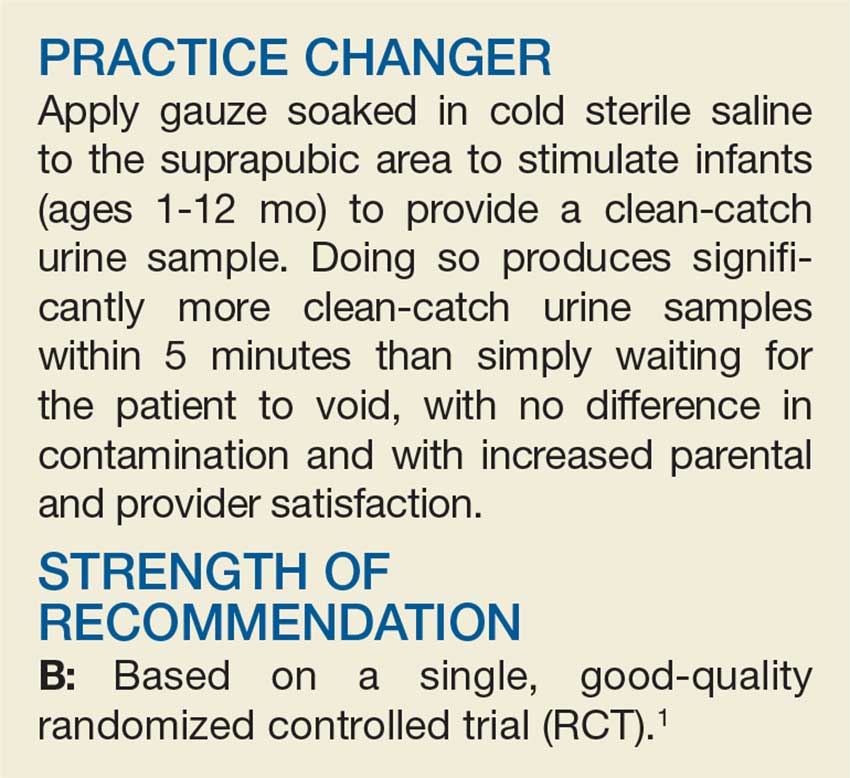

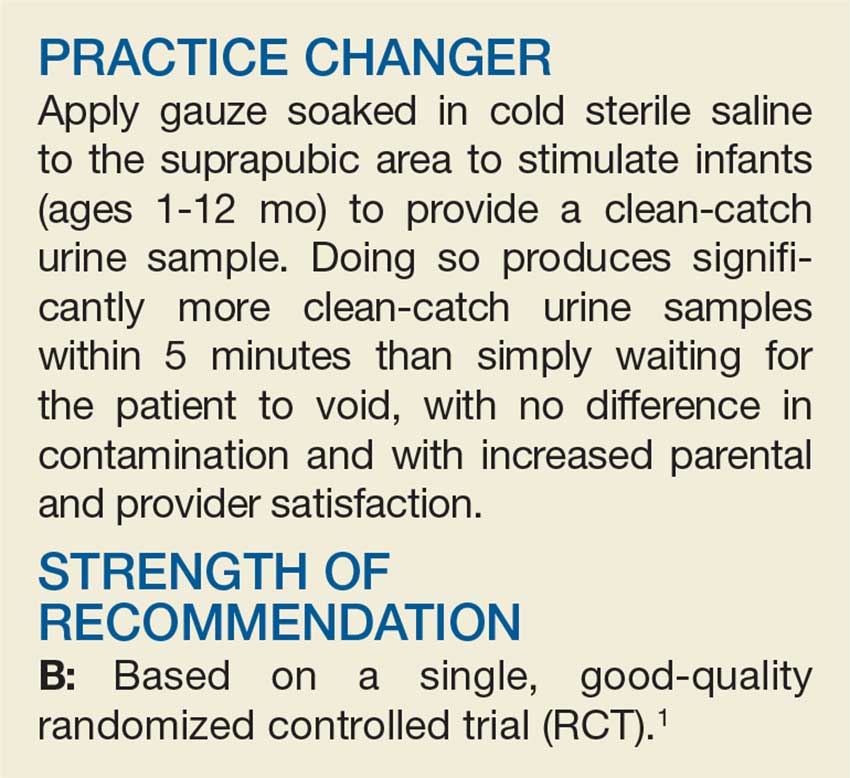

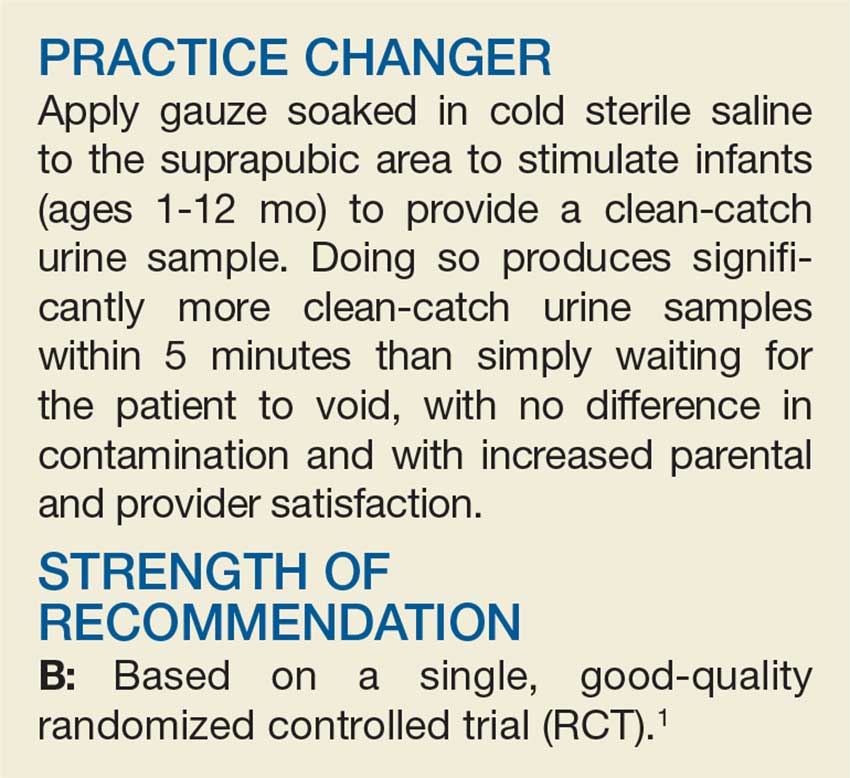

An Easy Approach to Obtaining Clean-catch Urine From Infants

A fussy 6-month-old infant is brought to the emergency department (ED) with a rectal temperature of 101.5°F. She is consolable,

A febrile infant in a family practice office or ED is a familiar clinical situation that may require an invasive diagnostic workup. Up to 7% of infants ages 2 to 24 months with fever of unknown origin may have a UTI.2 Collecting a urine sample from pre–toilet-trained children can be time consuming. In fact, in one RCT, obtaining a clean-catch urine sample in this age group took more than an hour, on average.3 But more convenient methods of urine collection, such as placing a cotton ball in the diaper or using a perineal collection bag, have contamination rates of up to 63%.4