User login

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

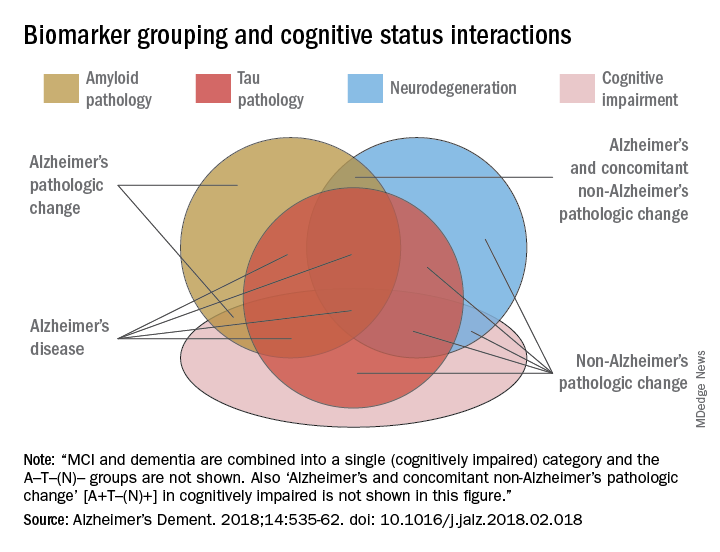

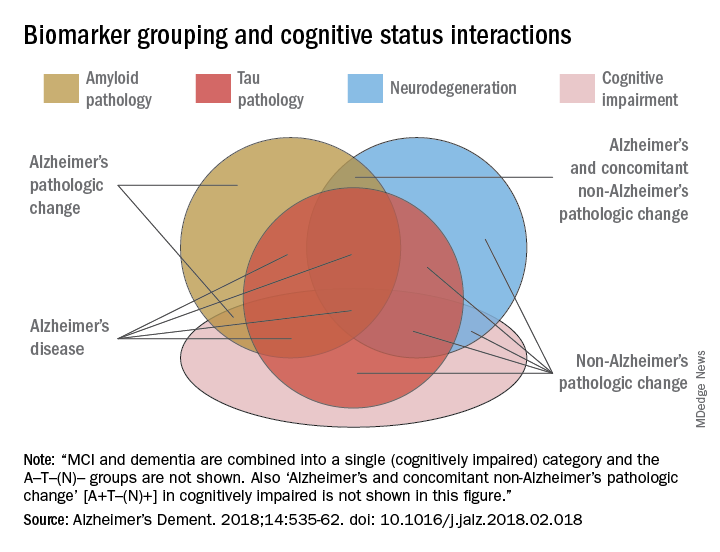

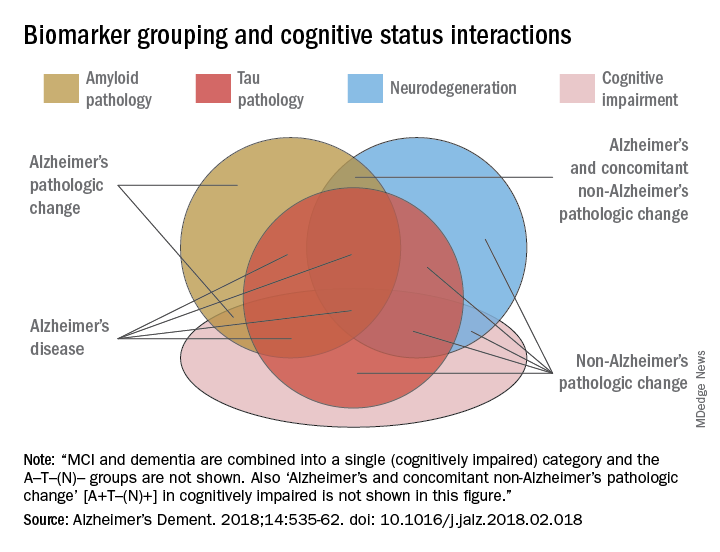

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

The biologically defined amyloid beta–tau–neuronal damage (ATN) framework is a logical and modern approach to Alzheimer’s disease (AD) diagnosis. It is hard to argue that more data are bad. Having such data on every patient would certainly be a luxury, but, with a few notable exceptions, the context in which this will most frequently occur is within the context of clinical trials.

While having this information does provide a biological basis for diagnosis, it does not account for non-AD contributions to the patient’s symptoms, which are found in more than half of all AD patients at autopsy; these non-AD pathologies also can influence clinical trial outcomes.

It also seems a bit ironic that the only meaningful manifestation of AD is now essentially left out of the diagnostic framework or relegated to nothing more than an adjective. Yet having a head full of amyloid means little if a person does not express symptoms (and vice versa), and we know that all people do not progress in the same way.

In the future, genomic and exposomic profiles may provide an even-more-nuanced picture, but further work is needed before that becomes a clinical reality. For now, the ATN biomarker framework represents the state of the art, though not an end.

Richard J. Caselli, MD, is professor of neurology at the Mayo Clinic Arizona in Scottsdale. He is also associate director and clinical core director of the Arizona Alzheimer’s Disease Center. He has no relevant disclosures.

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

A new definition of Alzheimer’s disease based solely on biomarkers has the potential to strengthen clinical trials and change the way physicians talk to patients.

AB is the key to this classification paradigm – any patient with it (A+) is on the Alzheimer’s continuum. But only those with both amyloid and tau in the brain (A+T+) receive the “Alzheimer’s disease” classification. A third biomarker, neurodegeneration, may be either present or absent for an Alzheimer’s disease profile (N+ or N-). Cognitive staging adds important details, but remains secondary to the biomarker classification.

Jointly created by National Institute on Aging and the Alzheimer’s Association, the system – dubbed the NIA-AA Research Framework – represents a new, common language that researchers around the world may now use to generate and test Alzheimer’s hypotheses, and to optimize both epidemiologic studies and interventional trials. It will be especially important as Alzheimer’s prevention trials seek to target patients who are cognitively normal, yet harbor the neuropathological hallmarks of the disease.

This recasting adds Alzheimer’s to the list of biomarker-defined disorders, including hypertension, diabetes, and hyperlipidemia. It is a timely and necessary reframing, said Clifford Jack, MD, chair of the 20-member committee that created the paradigm. It appears in the April 10 issue of Alzheimer’s & Dementia.

“This is a fundamental change in the definition of Alzheimer’s disease,” Dr. Jack said in an interview. “We are advocating the disease be defined by its neuropathology [of plaques and tangles], which is specific to Alzheimer’s, and no longer by clinical symptoms which are not specific for any disease.”

One of the primary intents is to refine AD research cohorts, allowing pure stratification of patients who actually have the intended therapeutic targets of amyloid beta or tau. Without biomarker screening, up to 30% of subjects who enroll in AD drug trials don’t have the target pathologies – a situation researchers say contributes to the long string of failed Alzheimer’s drug studies.

For now, the system is intended only for research settings said Dr. Jack, an Alzheimer’s investigator at the Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minn. But as biomarker testing comes of age and new less-expensive markers are discovered, the paradigm will likely be incorporated into clinical practice. The process can begin even now with a simple change in the way doctors talk to patients about Alzheimer’s, he said in an interview.

“We advocate people stop using the terms ‘probable or possible AD.’ A better term is ‘Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome.’ Without biomarkers, the clinical syndrome is the only thing you can know. What you can’t know is whether they do or don’t have Alzheimer’s disease. When I’m asked by physicians, ‘What do I tell my patients now?’ my very direct answer is ‘Tell them the truth.’ And the truth is that they have Alzheimer’s clinical syndrome and may or may not have Alzheimer’s disease.”

A reflection of evolving science

The research framework reflects advances in Alzheimer’s science that have occurred since the NIA last updated it AD diagnostic criteria in 2011. Those criteria divided the disease continuum into three phases largely based on cognitive symptoms, but were the first to recognize a presymptomatic AD phase.

- Preclinical: Brain changes, including amyloid buildup and other nerve cell changes already may be in progress but significant clinical symptoms are not yet evident.

- Mild cognitive impairment (MCI): A stage marked by symptoms of memory and/or other thinking problems that are greater than normal for a person’s age and education but that do not interfere with his or her independence. MCI may or may not progress to Alzheimer’s dementia.

- Alzheimer’s dementia: The final stage of the disease in which the symptoms of Alzheimer’s, such as memory loss, word-finding difficulties, and visual/spatial problems, are significant enough to impair a person’s ability to function independently.

The next 6 years brought striking advances in understanding the biology and pathology of AD, as well as technical advances in biomarker measurements. It became possible not only to measure AB and tau in cerebrospinal fluid but also to see these proteins in living brains with specialized PET ligands. It also became obvious that about a third of subjects in any given AD study didn’t have the disease-defining brain plaques and tangles – the therapeutic targets of all the largest drug studies to date. And while it’s clear that none of the interventions that have been through trials have exerted a significant benefit yet, “Treating people for a disease they don’t have can’t possibly help the results,” Dr. Jack said.

These research observations and revolutionary biomarker advances have reshaped the way researchers think about AD. To maximize research potential and to create a global classification standard that would unify studies as well, NIA and the Alzheimer’s Association convened several meetings to redefine Alzheimer’s disease biologically, by pathologic brain changes as measured by biomarkers. In this paradigm, cognitive dysfunction steps aside as the primary classification driver, becoming a symptom of AD rather than its definition.

“The way AD has historically been defined is by clinical symptoms: a progressive amnestic dementia was Alzheimer’s, and if there was no progressive amnestic dementia, it wasn’t,” Dr. Jack said. “Well, it turns out that both of those statements are wrong. About 30% of people with progressive amnestic dementia have other things causing it.”

It makes much more sense, he said, to define the disease based on its unique neuropathologic signature: amyloid beta plaques and tau neurofibrillary tangles in the brain.

The three-part key: A/T(N)

The NIA-AA research framework yields eight biomarker profiles with different combinations of amyloid (A), tau (T), and neuropathologic damage (N).

“Different measures have different roles,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues wrote in Alzheimer’s & Dementia. “Amyloid beta biomarkers determine whether or not an individual is in the Alzheimer’s continuum. Pathologic tau biomarkers determine if someone who is in the Alzheimer’s continuum has AD, because both amyloid beta and tau are required for a neuropathologic diagnosis of the disease. Neurodegenerative/neuronal injury biomarkers and cognitive symptoms, neither of which is specific for AD, are used only to stage severity not to define the presence of the Alzheimer’s continuum.”

The “N” category is not as cut and dried at the other biomarkers, the paper noted.

“Biomarkers in the (N) group are indicators of neurodegeneration or neuronal injury resulting from many causes; they are not specific for neurodegeneration due to AD. In any individual, the proportion of observed neurodegeneration/injury that can be attributed to AD versus other possible comorbid conditions (most of which have no extant biomarker) is unknown.”

The biomarker profiles are:

- A-T-(N): Normal AD biomarkers

- A+T-(N): Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T+(N): Alzheimer’s disease; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A+T-(N)+: Alzheimer’s with suspected non Alzheimer’s pathologic change; Alzheimer’s continuum

- A-T+(N)-: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T-(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

- A-T+(N)+: Non-AD pathologic change

“This latter biomarker profile implies evidence of one or more neuropathologic processes other than AD and has been labeled ‘suspected non-Alzheimer’s pathophysiology, or SNAP,” according to the paper.

Cognitive staging further refines each person’s status. There are two clinical staging schemes in the framework. One is the familiar syndromal staging system of cognitively unimpaired, MCI, and dementia, which can be subdivided into mild, moderate, and severe. This can be applied to anyone with a biomarker profile.

The second, a six-stage numerical clinical staging scheme, will apply only to those who are amyloid-positive and on the Alzheimer’s continuum. Stages run from 1 (unimpaired) to 6 (severe dementia). The numeric staging does not concentrate solely on cognition but also takes into account neurobehavioral and functional symptoms. It includes a transitional stage during which measures may be within population norms but have declined relative to the individual’s past performance.

The numeric staging scheme is intended to mesh with FDA guidance for clinical trials outcomes, the committee noted.

“A useful application envisioned for this numeric cognitive staging scheme is interventional trials. Indeed, the NIA-AA numeric staging scheme is intentionally very similar to the categorical system for staging AD outlined in recent FDA guidance for industry pertaining to developing drugs for treatment of early AD … it was our belief that harmonizing this aspect of the framework with FDA guidance would enhance cross fertilization between observational and interventional studies, which in turn would facilitate conduct of interventional clinical trials early in the disease process.”

The entire system yields a shorthand biomarker profile entirely unique to each subject. For example an A+T-(N)+ MCI profile suggests that both Alzheimer’s and non-Alzheimer’s pathologic change may be contributing to the cognitive impairment. A cognitive staging number could also be added.

This biomarker profile introduces the option of completely avoiding traditional AD nomenclature, the committee noted.

“Some investigators may prefer to not use the biomarker category terminology but instead simply report biomarker profile, i.e., A+T+(N)+ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease.’ An alternative is to combine the biomarker profile with a descriptive term – for example, ‘A+T+(N)+ with dementia’ instead of ‘Alzheimer’s disease with dementia’.”

Again, Dr. Jack cautioned, the paradigm is not intended for clinical use – at least not now. It relies entirely on biomarkers obtained by methods that are either invasive (lumbar puncture), unavailable outside research settings (tau scans), or very expensive when privately obtained (amyloid scans). Until this situation changes, the biomarker profile paradigm has little clinical impact.

IDEAS on the horizon

Change may be coming, however. The Alzheimer’s Association-sponsored Imaging Dementia–Evidence for Amyloid Scanning (IDEAS) study is assessing the clinical usefulness of amyloid PET scans and their impact on patient outcomes. The goal is to accumulate enough data to prove that amyloid scans are a cost-effective addition to the management of dementia patients. If federal payers agree and decide to cover amyloid scans, advocates hope that private insurers might follow suit.

An interim analysis of 4,000 scans, presented at the 2017 Alzheimer’s Association International Conference, was quite positive. Scan results changed patient management in 68% of cases, including refining dementia diagnoses, adding, stopping, or switching medications, and altering patient counseling.

IDEAS uses an FDA-approved amyloid imaging agent. But although several are under investigation, there are no approved tau PET ligands. However, other less-invasive and less-costly options may soon be developed, the committee noted. The search continues for a validated blood-based biomarker, including neurofilament light protein, plasma amyloid beta, and plasma tau.

“In the future, less-invasive/less-expensive blood-based biomarker tests - along with genetics, clinical, and demographic information - will likely play an important screening role in selecting individuals for more-expensive/more-invasive biomarker testing. This has been the history in other biologically defined diseases such as cardiovascular disease,” Dr. Jack and his colleagues noted in the paper.

In any case, however, without an effective treatment, much of the information conveyed by the biomarker profile paradigm remains, literally, academic, Dr. Jack said.

“If [the biomarker profile] were easy to determine and inexpensive, I imagine a lot of people would ask for it. Certainly many people would want to know, especially if they have a cognitive problem. People who have a family history, who may have Alzheimer’s pathology without the symptoms, might want to know. But the reality is that, until there’s a treatment that alters the course of this disease, finding out that you actually have Alzheimer’s is not going to enable you to change anything.”

The editors of Alzheimer’s & Dementia are seeking comment on the research framework. Letters and commentary can be submitted through June and will be considered for publication in an e-book, to be published sometime this summer, according to an accompanying editorial (https://doi.org/10/1016/j.jalz.2018.03.003).

Alzheimer’s & Dementia is the official journal of the Alzheimer’s Association. Dr. Jack has served on scientific advisory boards for Elan/Janssen AI, Bristol-Meyers Squibb, Eli Lilly, GE Healthcare, Siemens, and Eisai; received research support from Baxter International, Allon Therapeutics; and holds stock in Johnson & Johnson. Disclosures for other committee members can be found here.

SOURCE: Jack CR et al. Alzheimer’s Dement. 2018;14:535-62. doi: 10.1016/j.jalz.2018.02.018.

FROM ALZHEIMER’S & DEMENTIA