User login

Study finds gaps in bundled colectomy payments

CHICAGO – As Medicare transitions to a value-based model that uses bundled payments, oncologic surgeons and medical institutions may want to take a close look at enhanced recovery pathways and more minimally invasive surgery for colectomy in both benign and malignant disease to close potential gaps in reimbursement and outcomes, according to a retrospective study of 4-year Medicare data presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium here.

The study evaluated reimbursement rates of three Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG) assigned to the study cohort of 10,928 cases in the Medicare database from 2011-2015: 331 (benign disease), 330 (colon cancer/no metastases), and 329 (metastatic colon cancer). “There is little data comparing the relative impact of MS-DRG on cost and reimbursement for oncologic versus benign colon resection as it relates to the index admission, post-acute care costs, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services total costs,” Dr. Hughes said.

With descriptive statistics, the study showed that benign resection resulted in higher average total charges than malignant disease ($66,033 vs. $60,581, respectively; P less than .001) and longer hospital stays (7.25 days vs. 6.92; P less than .002), Dr. Hughes said. However, Medicare reimbursements were similar for both pathology groups: $10,358 for benign disease versus $10,483 for oncologic pathology (P = .434). Cancer patients were about 25% more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility than were those in the benign group (16.6% vs. 12.4%, respectively; P less than .001).

“What we know from other data is that, compared to fee-for-service for surgical colectomies, a value-based payment model resulted in lower payments for the index admission,” Dr. Hughes said. “A greater proportion of these patients also contributed to a negative margin for hospitals when compared to the fee-for-service model, as well as a higher risk across acute care services.”

Of patients in the study cohort, 67% had surgery for malignant disease. Both benign and malignant groups had more open colectomies than minimally invasive colectomies: 60% and 36.8%, respectively, of procedures in the benign group and 63% and 40% in the cancer group (P less than .001).

The goal of the study was to identify potential gaps in adopting MS-DRG for the bundled payment model in benign versus malignant colectomy, Dr. Hughes said. The study identified three gaps:

- DRG poorly differentiates between benign and malignant disease. This problem is evidenced by the higher cost for the index admission in benign disease. “Whereas in malignant disease, there is a greater unrecognized cost-shifting to post-acute care services which are not addressed by the DRG system,” he said.

- The dominance of open colectomy where MIS could reduce episode costs. The study cited research that reported the advantages of MIS include lower episode costs in both younger and older patients, by $1,466 and $632, respectively; shorter hospital stays by 1.46 days; 20% lower 30-day readmissions rates; and lower rates of post-acute care services (J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0521)

- Potential for DRG migration from code 331 (benign disease) to 330 (colon cancer but not with metastasis). Dr. Hughes and his coauthors published a study that reported a 14.2% rate of DRG migration in this same Medicare cohort, that is, classified as 331 on admission but migrated to 330. So, compared with other patients, this group ended up with longer LOS (7.6 vs. 4.8 days); higher total charges ($63,149 vs. $46,339); and higher CMS payment ($11,159 vs. $7,210) (Am J Surg. 2018;215:493-6). “We also identified a potential role for enhanced-recovery pathways to mitigate these factors,” he said.

He noted that the different stakeholders – hospitals, surgeons, anesthesiologists, hospitalists, other physicians, nurses, and extenders – will have to resolve how to divide bundled payments. “The biggest thing is communication between these groups, because moving forward CMS is trying to step away from the role of determining who gets paid what,” Dr. Hughes said. He noted this finding is consistent with his own previously published findings, along with those from senior study coauthor Anthony J. Senagore, MD, FACS, on resource consumption in value-based care.

Dr. Hughes and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Hughes is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Huges BD. SSO 2018.

CHICAGO – As Medicare transitions to a value-based model that uses bundled payments, oncologic surgeons and medical institutions may want to take a close look at enhanced recovery pathways and more minimally invasive surgery for colectomy in both benign and malignant disease to close potential gaps in reimbursement and outcomes, according to a retrospective study of 4-year Medicare data presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium here.

The study evaluated reimbursement rates of three Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG) assigned to the study cohort of 10,928 cases in the Medicare database from 2011-2015: 331 (benign disease), 330 (colon cancer/no metastases), and 329 (metastatic colon cancer). “There is little data comparing the relative impact of MS-DRG on cost and reimbursement for oncologic versus benign colon resection as it relates to the index admission, post-acute care costs, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services total costs,” Dr. Hughes said.

With descriptive statistics, the study showed that benign resection resulted in higher average total charges than malignant disease ($66,033 vs. $60,581, respectively; P less than .001) and longer hospital stays (7.25 days vs. 6.92; P less than .002), Dr. Hughes said. However, Medicare reimbursements were similar for both pathology groups: $10,358 for benign disease versus $10,483 for oncologic pathology (P = .434). Cancer patients were about 25% more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility than were those in the benign group (16.6% vs. 12.4%, respectively; P less than .001).

“What we know from other data is that, compared to fee-for-service for surgical colectomies, a value-based payment model resulted in lower payments for the index admission,” Dr. Hughes said. “A greater proportion of these patients also contributed to a negative margin for hospitals when compared to the fee-for-service model, as well as a higher risk across acute care services.”

Of patients in the study cohort, 67% had surgery for malignant disease. Both benign and malignant groups had more open colectomies than minimally invasive colectomies: 60% and 36.8%, respectively, of procedures in the benign group and 63% and 40% in the cancer group (P less than .001).

The goal of the study was to identify potential gaps in adopting MS-DRG for the bundled payment model in benign versus malignant colectomy, Dr. Hughes said. The study identified three gaps:

- DRG poorly differentiates between benign and malignant disease. This problem is evidenced by the higher cost for the index admission in benign disease. “Whereas in malignant disease, there is a greater unrecognized cost-shifting to post-acute care services which are not addressed by the DRG system,” he said.

- The dominance of open colectomy where MIS could reduce episode costs. The study cited research that reported the advantages of MIS include lower episode costs in both younger and older patients, by $1,466 and $632, respectively; shorter hospital stays by 1.46 days; 20% lower 30-day readmissions rates; and lower rates of post-acute care services (J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0521)

- Potential for DRG migration from code 331 (benign disease) to 330 (colon cancer but not with metastasis). Dr. Hughes and his coauthors published a study that reported a 14.2% rate of DRG migration in this same Medicare cohort, that is, classified as 331 on admission but migrated to 330. So, compared with other patients, this group ended up with longer LOS (7.6 vs. 4.8 days); higher total charges ($63,149 vs. $46,339); and higher CMS payment ($11,159 vs. $7,210) (Am J Surg. 2018;215:493-6). “We also identified a potential role for enhanced-recovery pathways to mitigate these factors,” he said.

He noted that the different stakeholders – hospitals, surgeons, anesthesiologists, hospitalists, other physicians, nurses, and extenders – will have to resolve how to divide bundled payments. “The biggest thing is communication between these groups, because moving forward CMS is trying to step away from the role of determining who gets paid what,” Dr. Hughes said. He noted this finding is consistent with his own previously published findings, along with those from senior study coauthor Anthony J. Senagore, MD, FACS, on resource consumption in value-based care.

Dr. Hughes and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Hughes is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Huges BD. SSO 2018.

CHICAGO – As Medicare transitions to a value-based model that uses bundled payments, oncologic surgeons and medical institutions may want to take a close look at enhanced recovery pathways and more minimally invasive surgery for colectomy in both benign and malignant disease to close potential gaps in reimbursement and outcomes, according to a retrospective study of 4-year Medicare data presented at the Society of Surgical Oncology Annual Cancer Symposium here.

The study evaluated reimbursement rates of three Medicare Severity–Diagnosis Related Groups (MS-DRG) assigned to the study cohort of 10,928 cases in the Medicare database from 2011-2015: 331 (benign disease), 330 (colon cancer/no metastases), and 329 (metastatic colon cancer). “There is little data comparing the relative impact of MS-DRG on cost and reimbursement for oncologic versus benign colon resection as it relates to the index admission, post-acute care costs, and Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services total costs,” Dr. Hughes said.

With descriptive statistics, the study showed that benign resection resulted in higher average total charges than malignant disease ($66,033 vs. $60,581, respectively; P less than .001) and longer hospital stays (7.25 days vs. 6.92; P less than .002), Dr. Hughes said. However, Medicare reimbursements were similar for both pathology groups: $10,358 for benign disease versus $10,483 for oncologic pathology (P = .434). Cancer patients were about 25% more likely to be discharged to a rehabilitation facility than were those in the benign group (16.6% vs. 12.4%, respectively; P less than .001).

“What we know from other data is that, compared to fee-for-service for surgical colectomies, a value-based payment model resulted in lower payments for the index admission,” Dr. Hughes said. “A greater proportion of these patients also contributed to a negative margin for hospitals when compared to the fee-for-service model, as well as a higher risk across acute care services.”

Of patients in the study cohort, 67% had surgery for malignant disease. Both benign and malignant groups had more open colectomies than minimally invasive colectomies: 60% and 36.8%, respectively, of procedures in the benign group and 63% and 40% in the cancer group (P less than .001).

The goal of the study was to identify potential gaps in adopting MS-DRG for the bundled payment model in benign versus malignant colectomy, Dr. Hughes said. The study identified three gaps:

- DRG poorly differentiates between benign and malignant disease. This problem is evidenced by the higher cost for the index admission in benign disease. “Whereas in malignant disease, there is a greater unrecognized cost-shifting to post-acute care services which are not addressed by the DRG system,” he said.

- The dominance of open colectomy where MIS could reduce episode costs. The study cited research that reported the advantages of MIS include lower episode costs in both younger and older patients, by $1,466 and $632, respectively; shorter hospital stays by 1.46 days; 20% lower 30-day readmissions rates; and lower rates of post-acute care services (J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A. 2017 Dec 13. doi: 10.1089/lap.2017.0521)

- Potential for DRG migration from code 331 (benign disease) to 330 (colon cancer but not with metastasis). Dr. Hughes and his coauthors published a study that reported a 14.2% rate of DRG migration in this same Medicare cohort, that is, classified as 331 on admission but migrated to 330. So, compared with other patients, this group ended up with longer LOS (7.6 vs. 4.8 days); higher total charges ($63,149 vs. $46,339); and higher CMS payment ($11,159 vs. $7,210) (Am J Surg. 2018;215:493-6). “We also identified a potential role for enhanced-recovery pathways to mitigate these factors,” he said.

He noted that the different stakeholders – hospitals, surgeons, anesthesiologists, hospitalists, other physicians, nurses, and extenders – will have to resolve how to divide bundled payments. “The biggest thing is communication between these groups, because moving forward CMS is trying to step away from the role of determining who gets paid what,” Dr. Hughes said. He noted this finding is consistent with his own previously published findings, along with those from senior study coauthor Anthony J. Senagore, MD, FACS, on resource consumption in value-based care.

Dr. Hughes and coauthors reported having no financial disclosures. Dr. Hughes is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

SOURCE: Huges BD. SSO 2018.

REPORTING FROM SSO 2018

Key clinical point: Medicare payment methodology does not truly reflect episode costs for colectomy.

Major finding: Colectomy charges were higher for benign disease than for cancer.

Study details: Retrospective cohort study of 10,928 patients in a national Medicare database who had colon surgery during 2011-2014.

Disclosures: The investigators had no financial relationships to disclose. Dr. Hughes is supported by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases of the National Institutes of Health.

Source: Huges BD. SSO 2018.

Neuro updates: Longer stroke window; hold the fresh frozen plasma

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

ORLANDO – Hospitalists in attendance at a Rapid Fire session at the Society of Hospital Medicine’s annual conference came away with updated information about stroke and intracranial hemorrhage, among the neurologic emergencies commonly seen in hospitalized patients.

Aaron Lord, MD, chief of neurocritical care at New York University Langone Health, provided hopeful news about thrombectomy for ischemic stroke and confirmed the importance of blood pressure management in intracranial hemorrhage in his review of several common neurologic emergencies.

Dr. Lord said that, for ischemic stroke, the evidence is now very good for mechanical thrombectomy, with newer data pointing to a prolonged treatment window for some patients.

Though IV tissue plasminogen activator (TPA) is the only Food and Drug Administration–approved pharmacologic treatment for acute stroke, said Dr. Lord, “It’s good, but it’s not perfect. It doesn’t necessarily target the clot or concentrate in it. ... The big kicker is that not all patients are candidates for IV TPA. They either present too late or have comorbidities.”

“Frustratingly, even for those who do present on time, TPA doesn’t work for everyone. This is especially true for large or long clots,” said Dr. Lord. In 2015, he said, a half-dozen trials examining mechanical thrombectomy for acute stroke were all positive, giving assurance to physicians and patients of this therapy’s efficacy within the 6-8 hour acute stroke window. Pooled analysis of the 2015 trials showed a number needed to treat (NNT) of 5 for regaining functional independence, and a NNT of 2.6 for decreased disability.

Further, he said, two additional trials have examined thrombectomy’s utility when patients have a large stroke penumbra, with a relatively small core infarct, using “tissue-based parameters rather than time” to select patients for thrombectomy. “These trials were just as positive as the initial trials,” said Dr. Lord; the trials showed NNTs of 2.9 and 3.6 for reduced disability in a population of patients who were 6-24 hours poststroke.

The takeaway for hospitalists? Even when it’s unknown how much time has passed since the onset of stroke symptoms, step No. 1 is still to activate the stroke team’s resources, giving patients the best hope for recovery. “We now have the luxury of treating patients up to 24 hours. This has revolutionized the way that we treat acute stroke,” said Dr. Lord.

For intracranial hemorrhage, the story is a little different. Here, “initial management focuses on preventing hematoma expansion,” said Dr. Lord.

After tending to airway, breathing, and circulation and activation of the stroke team, the managing clinician should turn to blood pressure management and reversal of any anticoagulation or antiplatelet therapy.

The medical literature gives some guidance about goal blood pressures, he said. Although all of the trials did not use the same parameters for “highest” or “lower” systolic blood pressures, the best data available point toward a systolic goal of about 140.

“Blood pressure treatment is still important,” said Dr. Lord. In larger hemorrhages or with hydrocephalus, he advised always at least considering placement of an intracranial pressure monitor.

If a patient is anticoagulated with a vitamin K antagonist, he said, the INCH trial showed that intracranial bleeds are best reversed by use of prothrombin complex concentration (PCC), rather than fresh frozen plasma (FFP). The trial, stopped early for safety, showed that the primary outcome of internationalized normal ratio of less than 1.2 by the 3-hour mark was reached by just 9% of the FFP group, compared with 67% of those who received PCC. Mortality was 35% for the FFP cohort, compared with 19% who received PCC.

Dr. Lord finds these data compelling. “When I ask my residents what the appropriate agent is for vitamin K reversal in acute ICH, and they answer FFP, I tell them, ‘That’s a great answer ... for 2012.’ ”

REPORTING FROM HM18

RIV awards go to studies of interhospital transfers and ‘virtual hospitalists’

ORLANDO – The top award in the research arm of the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition, bestowed Monday night at HM18, went to investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who looked for trouble spots in interhospital transfers across more than 24,000 cases.

In the innovations category, also awarded Tuesday night, the top award went to clinicians and researchers at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, who attempted to use “virtual hospitalists” to improve local care at rural, critical-access hospitals.

The winning study in the research arm set out to pinpoint problems that could be attributed to process in cases of patients being transferred from one acute care facility to another, and was presented by Stephanie Mueller, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate physician in the hospital medicine unit at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Mueller and her colleagues looked at transfers to the hospital from 2005 to 2013. They analyzed the effects that three factors – day of the week, time of day, and admission team “busyness” on the day of the transfer – had on transfers to intensive care within 48 hours and on 30-day mortality. They looked at data for Monday through Thursday, compared with Friday through Sunday, at day, evening, and night transfers as well as the number of patient admissions and discharges to the admitting team on that day.

They found that nighttime arrival was linked with an increased chance of being transferred to the ICU and with 30-day mortality. They also found that weekday arrival was associated with lower odds of mortality among patients getting cardiothoracic and gastrointestinal surgery.

“I think that these are potential targets in which we can actually do something to mitigate the outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Mueller said. “I’m working on a number of studies related to this topic and so it’s sort of validating that this is an important topic and that I should continue doing what I’m doing.”

Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, a judge in the research arm and associate professor at University of Texas, San Antonio, praised the relevance of the project.

“Interhospital transfer is a topic that a lot of hospitals are dealing with right now,” he said. “It’s always a group of patients that we worry about.”

“One of the strongest things about this poster was the strong methodology,” said another judge, Vineet Gupta, MD, FHM, assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. “The statistical analysis was really good, very strong, very robust.”

The innovations award–winning study, presented by Ethan Kuperman, MD, MSc, FHM, clinical assistant professor at the University of Iowa, involved an attempt to reduce transfers from the emergency departments of critical-access hospitals in rural Iowa to urban medical centers by providing care with “virtual hospitalists” using tablets.

“Our goal was to treat more patients locally, to keep those patients happy in their communities. That’s what patients get out of it,” Dr. Kuperman told judges. “The hospitals get to keep their family practice doctors doing primary care, stay open, and get more patients. Win, win, win.”

At the critical-access hospital pilot site, virtual hospitalists at the University of Iowa handled all inpatient and observation admissions, with the assistance of local advance practice professionals. The percentage of outside transfers from the emergency department over 64 weeks after implementation was 12.9%, a statistically significant drop from the 16.6% seen in a 24-week baseline period. This did not lead to another goal – a higher daily census at the hospital – though, because there was also a drop in ED visits that ended in a hospital admission.

At two other sites, where virtual hospitalists provided fewer services – at one site, they also helped with preoperative work – there was less of an impact, Dr. Kuperman said. He said he was encouraged that the mean time reported by virtual hospitalists for patient care and documentation was just 2.8 hours a day, but there were days when that hit 12 hours, so there could be a need for “surge” coverage.

He said he’s gratified that the award draws more attention to attempts to improve the care at rural hospitals and that he plans to continue to develop the program.

“Hopefully, this helps get the word out,” Dr. Kuperman said. “I think a lot of work still needs to be done.”

The awards capped a 2-hour competition in which judges went from poster to poster, hearing short presentations from researchers and asking rapid-fire questions. The decisions were difficult in both categories, the judges said. The judges in the innovations category, for instance, deliberated at a table outside the exhibit hall for about 20 minutes before coming to a decision.

The pool of 20 finalists – 10 in each category – were chosen from hundreds of submissions considered during the final two rounds of judging on Tuesday night. In the research category, 261 abstracts were accepted from the 319 submitted; in the innovations category, 140 were accepted from the 207 submitted.

ORLANDO – The top award in the research arm of the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition, bestowed Monday night at HM18, went to investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who looked for trouble spots in interhospital transfers across more than 24,000 cases.

In the innovations category, also awarded Tuesday night, the top award went to clinicians and researchers at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, who attempted to use “virtual hospitalists” to improve local care at rural, critical-access hospitals.

The winning study in the research arm set out to pinpoint problems that could be attributed to process in cases of patients being transferred from one acute care facility to another, and was presented by Stephanie Mueller, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate physician in the hospital medicine unit at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Mueller and her colleagues looked at transfers to the hospital from 2005 to 2013. They analyzed the effects that three factors – day of the week, time of day, and admission team “busyness” on the day of the transfer – had on transfers to intensive care within 48 hours and on 30-day mortality. They looked at data for Monday through Thursday, compared with Friday through Sunday, at day, evening, and night transfers as well as the number of patient admissions and discharges to the admitting team on that day.

They found that nighttime arrival was linked with an increased chance of being transferred to the ICU and with 30-day mortality. They also found that weekday arrival was associated with lower odds of mortality among patients getting cardiothoracic and gastrointestinal surgery.

“I think that these are potential targets in which we can actually do something to mitigate the outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Mueller said. “I’m working on a number of studies related to this topic and so it’s sort of validating that this is an important topic and that I should continue doing what I’m doing.”

Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, a judge in the research arm and associate professor at University of Texas, San Antonio, praised the relevance of the project.

“Interhospital transfer is a topic that a lot of hospitals are dealing with right now,” he said. “It’s always a group of patients that we worry about.”

“One of the strongest things about this poster was the strong methodology,” said another judge, Vineet Gupta, MD, FHM, assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. “The statistical analysis was really good, very strong, very robust.”

The innovations award–winning study, presented by Ethan Kuperman, MD, MSc, FHM, clinical assistant professor at the University of Iowa, involved an attempt to reduce transfers from the emergency departments of critical-access hospitals in rural Iowa to urban medical centers by providing care with “virtual hospitalists” using tablets.

“Our goal was to treat more patients locally, to keep those patients happy in their communities. That’s what patients get out of it,” Dr. Kuperman told judges. “The hospitals get to keep their family practice doctors doing primary care, stay open, and get more patients. Win, win, win.”

At the critical-access hospital pilot site, virtual hospitalists at the University of Iowa handled all inpatient and observation admissions, with the assistance of local advance practice professionals. The percentage of outside transfers from the emergency department over 64 weeks after implementation was 12.9%, a statistically significant drop from the 16.6% seen in a 24-week baseline period. This did not lead to another goal – a higher daily census at the hospital – though, because there was also a drop in ED visits that ended in a hospital admission.

At two other sites, where virtual hospitalists provided fewer services – at one site, they also helped with preoperative work – there was less of an impact, Dr. Kuperman said. He said he was encouraged that the mean time reported by virtual hospitalists for patient care and documentation was just 2.8 hours a day, but there were days when that hit 12 hours, so there could be a need for “surge” coverage.

He said he’s gratified that the award draws more attention to attempts to improve the care at rural hospitals and that he plans to continue to develop the program.

“Hopefully, this helps get the word out,” Dr. Kuperman said. “I think a lot of work still needs to be done.”

The awards capped a 2-hour competition in which judges went from poster to poster, hearing short presentations from researchers and asking rapid-fire questions. The decisions were difficult in both categories, the judges said. The judges in the innovations category, for instance, deliberated at a table outside the exhibit hall for about 20 minutes before coming to a decision.

The pool of 20 finalists – 10 in each category – were chosen from hundreds of submissions considered during the final two rounds of judging on Tuesday night. In the research category, 261 abstracts were accepted from the 319 submitted; in the innovations category, 140 were accepted from the 207 submitted.

ORLANDO – The top award in the research arm of the Research, Innovations and Clinical Vignettes (RIV) competition, bestowed Monday night at HM18, went to investigators at Brigham and Women’s Hospital in Boston, who looked for trouble spots in interhospital transfers across more than 24,000 cases.

In the innovations category, also awarded Tuesday night, the top award went to clinicians and researchers at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, who attempted to use “virtual hospitalists” to improve local care at rural, critical-access hospitals.

The winning study in the research arm set out to pinpoint problems that could be attributed to process in cases of patients being transferred from one acute care facility to another, and was presented by Stephanie Mueller, MD, MPH, SFHM, associate physician in the hospital medicine unit at Brigham and Women’s.

Dr. Mueller and her colleagues looked at transfers to the hospital from 2005 to 2013. They analyzed the effects that three factors – day of the week, time of day, and admission team “busyness” on the day of the transfer – had on transfers to intensive care within 48 hours and on 30-day mortality. They looked at data for Monday through Thursday, compared with Friday through Sunday, at day, evening, and night transfers as well as the number of patient admissions and discharges to the admitting team on that day.

They found that nighttime arrival was linked with an increased chance of being transferred to the ICU and with 30-day mortality. They also found that weekday arrival was associated with lower odds of mortality among patients getting cardiothoracic and gastrointestinal surgery.

“I think that these are potential targets in which we can actually do something to mitigate the outcomes for these patients,” Dr. Mueller said. “I’m working on a number of studies related to this topic and so it’s sort of validating that this is an important topic and that I should continue doing what I’m doing.”

Raj Sehgal, MD, FHM, a judge in the research arm and associate professor at University of Texas, San Antonio, praised the relevance of the project.

“Interhospital transfer is a topic that a lot of hospitals are dealing with right now,” he said. “It’s always a group of patients that we worry about.”

“One of the strongest things about this poster was the strong methodology,” said another judge, Vineet Gupta, MD, FHM, assistant clinical professor at the University of California, San Diego. “The statistical analysis was really good, very strong, very robust.”

The innovations award–winning study, presented by Ethan Kuperman, MD, MSc, FHM, clinical assistant professor at the University of Iowa, involved an attempt to reduce transfers from the emergency departments of critical-access hospitals in rural Iowa to urban medical centers by providing care with “virtual hospitalists” using tablets.

“Our goal was to treat more patients locally, to keep those patients happy in their communities. That’s what patients get out of it,” Dr. Kuperman told judges. “The hospitals get to keep their family practice doctors doing primary care, stay open, and get more patients. Win, win, win.”

At the critical-access hospital pilot site, virtual hospitalists at the University of Iowa handled all inpatient and observation admissions, with the assistance of local advance practice professionals. The percentage of outside transfers from the emergency department over 64 weeks after implementation was 12.9%, a statistically significant drop from the 16.6% seen in a 24-week baseline period. This did not lead to another goal – a higher daily census at the hospital – though, because there was also a drop in ED visits that ended in a hospital admission.

At two other sites, where virtual hospitalists provided fewer services – at one site, they also helped with preoperative work – there was less of an impact, Dr. Kuperman said. He said he was encouraged that the mean time reported by virtual hospitalists for patient care and documentation was just 2.8 hours a day, but there were days when that hit 12 hours, so there could be a need for “surge” coverage.

He said he’s gratified that the award draws more attention to attempts to improve the care at rural hospitals and that he plans to continue to develop the program.

“Hopefully, this helps get the word out,” Dr. Kuperman said. “I think a lot of work still needs to be done.”

The awards capped a 2-hour competition in which judges went from poster to poster, hearing short presentations from researchers and asking rapid-fire questions. The decisions were difficult in both categories, the judges said. The judges in the innovations category, for instance, deliberated at a table outside the exhibit hall for about 20 minutes before coming to a decision.

The pool of 20 finalists – 10 in each category – were chosen from hundreds of submissions considered during the final two rounds of judging on Tuesday night. In the research category, 261 abstracts were accepted from the 319 submitted; in the innovations category, 140 were accepted from the 207 submitted.

REPORTING FROM HM18

Video: The SHM Physicians in Training Committee – increasing the hospitalist pipeline

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Brian Kwan, MD, SFHM, of the University of California, San Diego, discusses the role of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee in “increasing the hospitalist pipeline.”

In discussing the work of the committee, Dr. Kwan describes how “a lot of our initiatives really focus on the training and development and basically nurturing them from becoming students to residents to early-career hospitalists.”

Two of the key programs he discusses are the Student Scholarship Program and the “new-this-year” Resident Travel Grant, among other initiatives that the committee is exploring.

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Brian Kwan, MD, SFHM, of the University of California, San Diego, discusses the role of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee in “increasing the hospitalist pipeline.”

In discussing the work of the committee, Dr. Kwan describes how “a lot of our initiatives really focus on the training and development and basically nurturing them from becoming students to residents to early-career hospitalists.”

Two of the key programs he discusses are the Student Scholarship Program and the “new-this-year” Resident Travel Grant, among other initiatives that the committee is exploring.

ORLANDO – In a video interview, Brian Kwan, MD, SFHM, of the University of California, San Diego, discusses the role of the SHM Physicians in Training Committee in “increasing the hospitalist pipeline.”

In discussing the work of the committee, Dr. Kwan describes how “a lot of our initiatives really focus on the training and development and basically nurturing them from becoming students to residents to early-career hospitalists.”

Two of the key programs he discusses are the Student Scholarship Program and the “new-this-year” Resident Travel Grant, among other initiatives that the committee is exploring.

REPORTING FROM HOSPITAL MEDICINE 2018

Asthma flourishing in its medical home

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Current asthma prevalence was 8.8% for adults aged 18 years and older who worked in health care and social assistance in 2011-2016, which put them above those in education services (8.2%); arts, entertainment, and recreation (8.1%); accommodation and food services (7.7%); and finance and insurance (7.5%). The overall rate for all working adults was 6.8%, Jacek M. Mazurek, MD, PhD, and Girija Syamlal, MBBS, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

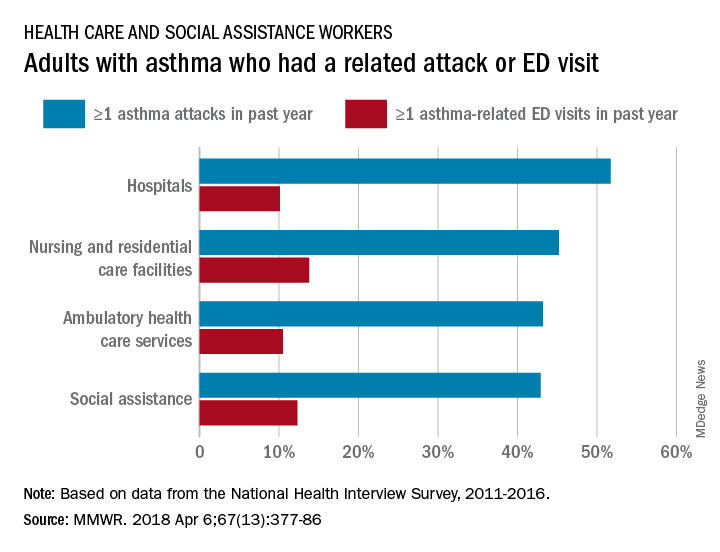

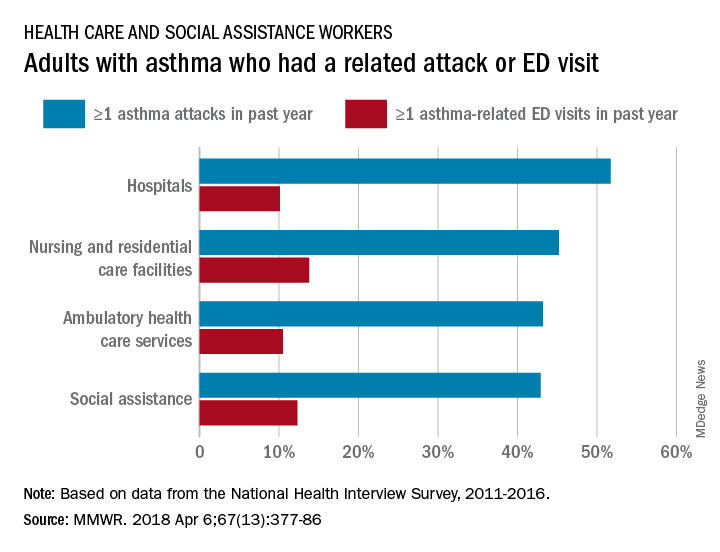

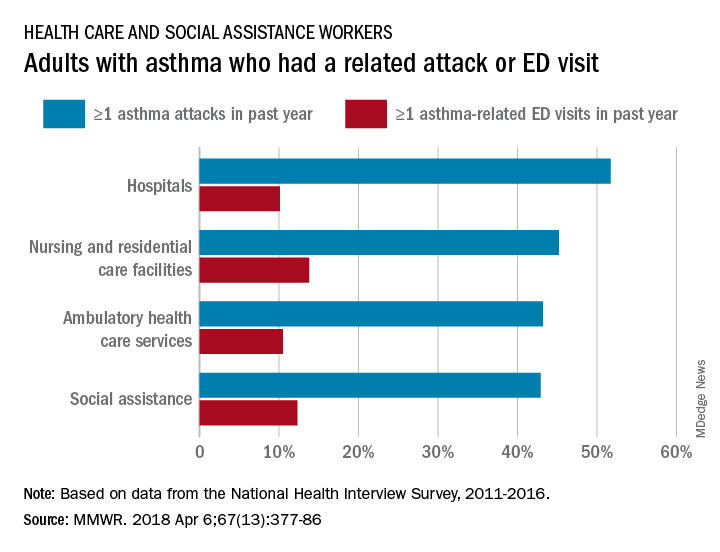

Among persons with asthma who were employed in health care and social assistance, 45.8% reported having at least one asthma attack in the previous year. Among the subgroups of the industry, those working in hospitals were highest with a 51.7% rate of past-year asthma attacks, followed by those working in nursing and residential care facilities at 45.2%, those working in ambulatory health care services at 43.2%, and those working in social assistance at 42.9%. The highest asthma attack rates among all industries were 57.3% for wood product manufacturing and 56.7% for plastics and rubber products manufacturing, the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Asthma-related visits to the emergency department in the past year were much less common for those in health care – 11.3% overall – and followed a pattern different from asthma attacks. Those working in nursing and residential care facilities were highest at 13.8%, with those in social assistance at 12.3%, those in ambulatory care at 10.5%, and those in hospitals the lowest at 10.1%. The highest ED-visit rate for any industry, 22.9%, was for workers in private households, said Dr. Mazurek and Dr. Syamlal, both of the respiratory health division at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, W.Va.

SOURCE: Mazurek JM, Syamlal G. MMWR. 2018 Apr 6;67(13):377-86.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Current asthma prevalence was 8.8% for adults aged 18 years and older who worked in health care and social assistance in 2011-2016, which put them above those in education services (8.2%); arts, entertainment, and recreation (8.1%); accommodation and food services (7.7%); and finance and insurance (7.5%). The overall rate for all working adults was 6.8%, Jacek M. Mazurek, MD, PhD, and Girija Syamlal, MBBS, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among persons with asthma who were employed in health care and social assistance, 45.8% reported having at least one asthma attack in the previous year. Among the subgroups of the industry, those working in hospitals were highest with a 51.7% rate of past-year asthma attacks, followed by those working in nursing and residential care facilities at 45.2%, those working in ambulatory health care services at 43.2%, and those working in social assistance at 42.9%. The highest asthma attack rates among all industries were 57.3% for wood product manufacturing and 56.7% for plastics and rubber products manufacturing, the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Asthma-related visits to the emergency department in the past year were much less common for those in health care – 11.3% overall – and followed a pattern different from asthma attacks. Those working in nursing and residential care facilities were highest at 13.8%, with those in social assistance at 12.3%, those in ambulatory care at 10.5%, and those in hospitals the lowest at 10.1%. The highest ED-visit rate for any industry, 22.9%, was for workers in private households, said Dr. Mazurek and Dr. Syamlal, both of the respiratory health division at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, W.Va.

SOURCE: Mazurek JM, Syamlal G. MMWR. 2018 Apr 6;67(13):377-86.

according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Current asthma prevalence was 8.8% for adults aged 18 years and older who worked in health care and social assistance in 2011-2016, which put them above those in education services (8.2%); arts, entertainment, and recreation (8.1%); accommodation and food services (7.7%); and finance and insurance (7.5%). The overall rate for all working adults was 6.8%, Jacek M. Mazurek, MD, PhD, and Girija Syamlal, MBBS, reported in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among persons with asthma who were employed in health care and social assistance, 45.8% reported having at least one asthma attack in the previous year. Among the subgroups of the industry, those working in hospitals were highest with a 51.7% rate of past-year asthma attacks, followed by those working in nursing and residential care facilities at 45.2%, those working in ambulatory health care services at 43.2%, and those working in social assistance at 42.9%. The highest asthma attack rates among all industries were 57.3% for wood product manufacturing and 56.7% for plastics and rubber products manufacturing, the investigators said, based on data from the National Health Interview Survey.

Asthma-related visits to the emergency department in the past year were much less common for those in health care – 11.3% overall – and followed a pattern different from asthma attacks. Those working in nursing and residential care facilities were highest at 13.8%, with those in social assistance at 12.3%, those in ambulatory care at 10.5%, and those in hospitals the lowest at 10.1%. The highest ED-visit rate for any industry, 22.9%, was for workers in private households, said Dr. Mazurek and Dr. Syamlal, both of the respiratory health division at the CDC’s National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health in Morgantown, W.Va.

SOURCE: Mazurek JM, Syamlal G. MMWR. 2018 Apr 6;67(13):377-86.

FROM MMWR

New developments in critical care and sepsis

Sepsis and critical care issues are in the spotlight at HM18, and these hot topics were the focus of the Monday education session, “He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named: Updates in Sepsis and Critical Care.”

Patricia Kritek, MD, EdM, of the University of Washington, Seattle, led an interactive and engaging session, educating attendees about the current research in sepsis and critical care areas so they would feel comfortable implementing the latest evidence into practice in the ICU.

The session focused on “what’s new” in critical care and sepsis from the literature published in the past year.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sepsis or septicemia patients averaged a 75% longer length of stay and were more than eight times likely to die, compared with patients hospitalized for other conditions.

“There has been a lot of discussion about steroids in sepsis that is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Kritek said in an interview. To tackle the always-tricky topic of steroids and sepsis, Dr. Kritek selected a trio of studies for review and discussion. In the first, vitamin C was potentially as effective as hydrocortisone and thiamine for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock (CHEST. 2017;151[6]:1229‐38). Another study addressed adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy for septic shock patients, and a third examined the use of hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone for adults with septic shock.

The trials not involving vitamin C were published in the New England Journal of Medicine this year, conducted in Australia (2018;378:797‐808) and France (2018;378:809‐18), and included 3,658 and 1,241 adult sepsis patients, respectively. The studies were similar in size and design. Based on these two studies, hydrocortisone appears to shorten septic shock duration, and treatment with hydrocortisone and possibly fludrocortisone could be helpful for the more seriously ill patients, said Dr. Kritek. As for the value of vitamin C and thiamine, “the jury is still out,” she noted.

Sepsis and critical care issues are in the spotlight at HM18, and these hot topics were the focus of the Monday education session, “He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named: Updates in Sepsis and Critical Care.”

Patricia Kritek, MD, EdM, of the University of Washington, Seattle, led an interactive and engaging session, educating attendees about the current research in sepsis and critical care areas so they would feel comfortable implementing the latest evidence into practice in the ICU.

The session focused on “what’s new” in critical care and sepsis from the literature published in the past year.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sepsis or septicemia patients averaged a 75% longer length of stay and were more than eight times likely to die, compared with patients hospitalized for other conditions.

“There has been a lot of discussion about steroids in sepsis that is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Kritek said in an interview. To tackle the always-tricky topic of steroids and sepsis, Dr. Kritek selected a trio of studies for review and discussion. In the first, vitamin C was potentially as effective as hydrocortisone and thiamine for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock (CHEST. 2017;151[6]:1229‐38). Another study addressed adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy for septic shock patients, and a third examined the use of hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone for adults with septic shock.

The trials not involving vitamin C were published in the New England Journal of Medicine this year, conducted in Australia (2018;378:797‐808) and France (2018;378:809‐18), and included 3,658 and 1,241 adult sepsis patients, respectively. The studies were similar in size and design. Based on these two studies, hydrocortisone appears to shorten septic shock duration, and treatment with hydrocortisone and possibly fludrocortisone could be helpful for the more seriously ill patients, said Dr. Kritek. As for the value of vitamin C and thiamine, “the jury is still out,” she noted.

Sepsis and critical care issues are in the spotlight at HM18, and these hot topics were the focus of the Monday education session, “He-Who-Shall-Not-Be-Named: Updates in Sepsis and Critical Care.”

Patricia Kritek, MD, EdM, of the University of Washington, Seattle, led an interactive and engaging session, educating attendees about the current research in sepsis and critical care areas so they would feel comfortable implementing the latest evidence into practice in the ICU.

The session focused on “what’s new” in critical care and sepsis from the literature published in the past year.

According to the National Center for Health Statistics at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, sepsis or septicemia patients averaged a 75% longer length of stay and were more than eight times likely to die, compared with patients hospitalized for other conditions.

“There has been a lot of discussion about steroids in sepsis that is potentially practice changing,” Dr. Kritek said in an interview. To tackle the always-tricky topic of steroids and sepsis, Dr. Kritek selected a trio of studies for review and discussion. In the first, vitamin C was potentially as effective as hydrocortisone and thiamine for the treatment of severe sepsis and septic shock (CHEST. 2017;151[6]:1229‐38). Another study addressed adjunctive glucocorticoid therapy for septic shock patients, and a third examined the use of hydrocortisone plus fludrocortisone for adults with septic shock.

The trials not involving vitamin C were published in the New England Journal of Medicine this year, conducted in Australia (2018;378:797‐808) and France (2018;378:809‐18), and included 3,658 and 1,241 adult sepsis patients, respectively. The studies were similar in size and design. Based on these two studies, hydrocortisone appears to shorten septic shock duration, and treatment with hydrocortisone and possibly fludrocortisone could be helpful for the more seriously ill patients, said Dr. Kritek. As for the value of vitamin C and thiamine, “the jury is still out,” she noted.

Antibiotic awareness tops ID agenda

Antibiotic resistance is “one of the greatest problems we face,” according to Jennifer A. Hanrahan, DO, MSc, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. Dr. Hanrahan led the education session, “A Bug’s Life: Infectious Disease Pearls,” and she called the topic “timely and timeless.”

Antibiotic resistance stems from several problems, Dr. Hanrahan said in her Monday presentation. “One of these is overuse of antibiotics, specifically overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the other problem is overuse of testing.”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that at least 2 million people in the United States develop antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections each year. At least 23,000 of these patients die each year because of these infections.

In 2013, the CDC published a report on drug-resistant threats in the United States. The three offenders deemed most serious – Clostridium difficile, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, continue to challenge clinicians.

Clinicians can help curb antibiotic resistance by practicing good stewardship, said Dr. Hanrahan. “Antimicrobial stewardship and laboratory stewardship are two things that can greatly improve patient care and outcomes for patients,” she said.

“Testing stewardship means ordering tests that are necessary based on signs and symptoms,” said Dr. Hanrahan. “For example, people often order urine cultures when there are no symptoms of urinary tract infection, and then end up treating positive cultures with antibiotics even when there are no symptoms of infection. This leads to unnecessary antibiotic exposure,” she noted.

The CDC’s core plans to fight antimicrobial resistance include:

- Preventing infections in the first place: The CDC emphasizes the importance of prevention through hand washing, safe food handling practices, and immunizations.

- Tracking data: The CDC collects and uses data on resistant infections to identify risk factors for resistance and develop strategies to prevent the spread of resistant bacteria.

- Practicing antibiotic stewardship: As Dr. Hanrahan noted, judicious use of antibiotics can help cut down on resistant bacteria.

- Developing alternatives: The CDC supports the development of new antibiotics and new tests to track antibacterial resistance.

Dr. Hanrahan discussed the Top 10 things hospitalists can do to improve lab testing and antimicrobial use.

“Hospitalists must recognize the need to decrease antibiotic use, utilize laboratory testing appropriately, and improve patient safety,” she said.

“There are a wide range of resources available on the Internet that can help you delve further into this topic and to find the appropriate balance for testing and treatment,” Dr. Hanrahan concluded.

Antibiotic resistance is “one of the greatest problems we face,” according to Jennifer A. Hanrahan, DO, MSc, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. Dr. Hanrahan led the education session, “A Bug’s Life: Infectious Disease Pearls,” and she called the topic “timely and timeless.”

Antibiotic resistance stems from several problems, Dr. Hanrahan said in her Monday presentation. “One of these is overuse of antibiotics, specifically overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the other problem is overuse of testing.”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that at least 2 million people in the United States develop antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections each year. At least 23,000 of these patients die each year because of these infections.

In 2013, the CDC published a report on drug-resistant threats in the United States. The three offenders deemed most serious – Clostridium difficile, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, continue to challenge clinicians.

Clinicians can help curb antibiotic resistance by practicing good stewardship, said Dr. Hanrahan. “Antimicrobial stewardship and laboratory stewardship are two things that can greatly improve patient care and outcomes for patients,” she said.

“Testing stewardship means ordering tests that are necessary based on signs and symptoms,” said Dr. Hanrahan. “For example, people often order urine cultures when there are no symptoms of urinary tract infection, and then end up treating positive cultures with antibiotics even when there are no symptoms of infection. This leads to unnecessary antibiotic exposure,” she noted.

The CDC’s core plans to fight antimicrobial resistance include:

- Preventing infections in the first place: The CDC emphasizes the importance of prevention through hand washing, safe food handling practices, and immunizations.

- Tracking data: The CDC collects and uses data on resistant infections to identify risk factors for resistance and develop strategies to prevent the spread of resistant bacteria.

- Practicing antibiotic stewardship: As Dr. Hanrahan noted, judicious use of antibiotics can help cut down on resistant bacteria.

- Developing alternatives: The CDC supports the development of new antibiotics and new tests to track antibacterial resistance.

Dr. Hanrahan discussed the Top 10 things hospitalists can do to improve lab testing and antimicrobial use.

“Hospitalists must recognize the need to decrease antibiotic use, utilize laboratory testing appropriately, and improve patient safety,” she said.

“There are a wide range of resources available on the Internet that can help you delve further into this topic and to find the appropriate balance for testing and treatment,” Dr. Hanrahan concluded.

Antibiotic resistance is “one of the greatest problems we face,” according to Jennifer A. Hanrahan, DO, MSc, of MetroHealth Medical Center in Cleveland. Dr. Hanrahan led the education session, “A Bug’s Life: Infectious Disease Pearls,” and she called the topic “timely and timeless.”

Antibiotic resistance stems from several problems, Dr. Hanrahan said in her Monday presentation. “One of these is overuse of antibiotics, specifically overuse of broad-spectrum antibiotics, and the other problem is overuse of testing.”

Data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention show that at least 2 million people in the United States develop antibiotic-resistant bacterial infections each year. At least 23,000 of these patients die each year because of these infections.

In 2013, the CDC published a report on drug-resistant threats in the United States. The three offenders deemed most serious – Clostridium difficile, Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, continue to challenge clinicians.

Clinicians can help curb antibiotic resistance by practicing good stewardship, said Dr. Hanrahan. “Antimicrobial stewardship and laboratory stewardship are two things that can greatly improve patient care and outcomes for patients,” she said.

“Testing stewardship means ordering tests that are necessary based on signs and symptoms,” said Dr. Hanrahan. “For example, people often order urine cultures when there are no symptoms of urinary tract infection, and then end up treating positive cultures with antibiotics even when there are no symptoms of infection. This leads to unnecessary antibiotic exposure,” she noted.

The CDC’s core plans to fight antimicrobial resistance include:

- Preventing infections in the first place: The CDC emphasizes the importance of prevention through hand washing, safe food handling practices, and immunizations.

- Tracking data: The CDC collects and uses data on resistant infections to identify risk factors for resistance and develop strategies to prevent the spread of resistant bacteria.

- Practicing antibiotic stewardship: As Dr. Hanrahan noted, judicious use of antibiotics can help cut down on resistant bacteria.

- Developing alternatives: The CDC supports the development of new antibiotics and new tests to track antibacterial resistance.

Dr. Hanrahan discussed the Top 10 things hospitalists can do to improve lab testing and antimicrobial use.

“Hospitalists must recognize the need to decrease antibiotic use, utilize laboratory testing appropriately, and improve patient safety,” she said.

“There are a wide range of resources available on the Internet that can help you delve further into this topic and to find the appropriate balance for testing and treatment,” Dr. Hanrahan concluded.

Myriad career options for hospitalists

The “Hospitalist Career Options” education session provided future and early-career hospitalists with information about the diversity of potential career tracks within hospital medicine.

“There are so many different things that people do and that’s what so amazing about hospital medicine,” said Dennis Chang, MD, FHM, associate professor in Mount Sinai Hospital’s division of hospital medicine, New York, in his talk on Monday. “You never really know where its going to go, and it’s really a matter of keeping your eye out for opportunities.”

Hospital medicine offers a diverse and interesting career that presents a variety of professional opportunities to those who practice it, Dr. Chang said. He noted that many hospitalists are gravitating toward careers in improving patient safety and quality improvement.

“They are working on the systems that are in the hospital and trying to make them more efficient and safer for patients,” he said.

Keeping with the theme of the talk, Dr. Chang pointed out that there a number of other specialty areas that hospitalists can explore.

“A lot of hospitalists also get into education, educating students and residents,” he said. If teaching is not your desired area of practice, you can also try your hand at “becoming CMO [chief medical officer] of a hospital” or other areas of administrative leadership or “informatics and electronic health records.” Most importantly, there are a variety of professional avenues available within hospital medicine, he added.

Dr. Chang said that the design of the session was intended to help early-career hospitalists navigate their professional path and indicated that it definitely would have provided him with some guidance. “When I was a resident thinking about what I wanted to do after residency, I didn’t necessarily know what hospital medicine was,” he said. “I think I thought it was a cool clinical job, but I didn’t understand that there were so many other things that you could do with it that are not clinical, but still really interesting.”

Dr. Chang emphasized that early-career hospitalists do not need to have a fully formed idea of the professional track they wish to pursue.

“It’s okay if you don’t know what you want to do, just do what you think is interesting and it’s amazing the things you can end up doing,” he said, noting that the best thing for residents and early-career hospitalists is “to get experience and training.”

At the end of the talk, Dr. Chang and his copresenter Daniel Ricotta, MD, offered attendees tips about other events that they might attend to advance their careers. Dr. Chang noted that SHM offers many smaller conferences that offer career development skills such as leadership.

The “Hospitalist Career Options” education session provided future and early-career hospitalists with information about the diversity of potential career tracks within hospital medicine.

“There are so many different things that people do and that’s what so amazing about hospital medicine,” said Dennis Chang, MD, FHM, associate professor in Mount Sinai Hospital’s division of hospital medicine, New York, in his talk on Monday. “You never really know where its going to go, and it’s really a matter of keeping your eye out for opportunities.”

Hospital medicine offers a diverse and interesting career that presents a variety of professional opportunities to those who practice it, Dr. Chang said. He noted that many hospitalists are gravitating toward careers in improving patient safety and quality improvement.

“They are working on the systems that are in the hospital and trying to make them more efficient and safer for patients,” he said.

Keeping with the theme of the talk, Dr. Chang pointed out that there a number of other specialty areas that hospitalists can explore.

“A lot of hospitalists also get into education, educating students and residents,” he said. If teaching is not your desired area of practice, you can also try your hand at “becoming CMO [chief medical officer] of a hospital” or other areas of administrative leadership or “informatics and electronic health records.” Most importantly, there are a variety of professional avenues available within hospital medicine, he added.

Dr. Chang said that the design of the session was intended to help early-career hospitalists navigate their professional path and indicated that it definitely would have provided him with some guidance. “When I was a resident thinking about what I wanted to do after residency, I didn’t necessarily know what hospital medicine was,” he said. “I think I thought it was a cool clinical job, but I didn’t understand that there were so many other things that you could do with it that are not clinical, but still really interesting.”

Dr. Chang emphasized that early-career hospitalists do not need to have a fully formed idea of the professional track they wish to pursue.

“It’s okay if you don’t know what you want to do, just do what you think is interesting and it’s amazing the things you can end up doing,” he said, noting that the best thing for residents and early-career hospitalists is “to get experience and training.”

At the end of the talk, Dr. Chang and his copresenter Daniel Ricotta, MD, offered attendees tips about other events that they might attend to advance their careers. Dr. Chang noted that SHM offers many smaller conferences that offer career development skills such as leadership.

The “Hospitalist Career Options” education session provided future and early-career hospitalists with information about the diversity of potential career tracks within hospital medicine.

“There are so many different things that people do and that’s what so amazing about hospital medicine,” said Dennis Chang, MD, FHM, associate professor in Mount Sinai Hospital’s division of hospital medicine, New York, in his talk on Monday. “You never really know where its going to go, and it’s really a matter of keeping your eye out for opportunities.”

Hospital medicine offers a diverse and interesting career that presents a variety of professional opportunities to those who practice it, Dr. Chang said. He noted that many hospitalists are gravitating toward careers in improving patient safety and quality improvement.

“They are working on the systems that are in the hospital and trying to make them more efficient and safer for patients,” he said.

Keeping with the theme of the talk, Dr. Chang pointed out that there a number of other specialty areas that hospitalists can explore.

“A lot of hospitalists also get into education, educating students and residents,” he said. If teaching is not your desired area of practice, you can also try your hand at “becoming CMO [chief medical officer] of a hospital” or other areas of administrative leadership or “informatics and electronic health records.” Most importantly, there are a variety of professional avenues available within hospital medicine, he added.

Dr. Chang said that the design of the session was intended to help early-career hospitalists navigate their professional path and indicated that it definitely would have provided him with some guidance. “When I was a resident thinking about what I wanted to do after residency, I didn’t necessarily know what hospital medicine was,” he said. “I think I thought it was a cool clinical job, but I didn’t understand that there were so many other things that you could do with it that are not clinical, but still really interesting.”

Dr. Chang emphasized that early-career hospitalists do not need to have a fully formed idea of the professional track they wish to pursue.

“It’s okay if you don’t know what you want to do, just do what you think is interesting and it’s amazing the things you can end up doing,” he said, noting that the best thing for residents and early-career hospitalists is “to get experience and training.”

At the end of the talk, Dr. Chang and his copresenter Daniel Ricotta, MD, offered attendees tips about other events that they might attend to advance their careers. Dr. Chang noted that SHM offers many smaller conferences that offer career development skills such as leadership.

Session tackles oncology emergencies

Hospitalists are on the front lines of diagnosis and management of patients with cancer, the second-leading cause of death in the United States. The session on Oncology Emergencies addressed the enormous number of clinical issues that must be considered within this patient population.

“The real challenge in managing sick cancer patients lies in the data-free zones,” presenter Benjamin L. Schlechter, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “I think the oncologic emergency we forget to talk about most often is the early diagnostic period,” he noted. The focus of Dr. Schlechter’s Monday talk was on this time frame and the process of getting patients with an advanced malignancy from diagnosis to treatment safely, which remains a clinical challenge.

“These patients often present with vague symptoms that do not point to any particular diagnosis,” stated Dr. Schlechter. “Once we identify that a patient has a symptomatic new malignancy, it is critical to determine who needs a rapid work-up as an inpatient on a hospital medicine service and who can be managed as an outpatient.”

Dr. Schlechter explained that there are no randomized trials to guide diagnostic work-up of malignancy or even define an expedited work-up. On the other hand, there are extensive data on treatment of newly diagnosed cancers. Clinical trials that guide first-line cancer therapy have clear eligibility criteria, which should inform hospitalists’ work-ups. “These include torso imaging, biopsy of a metastatic site, and assessment of liver and kidney function,” Dr. Schlechter continued. “The reason kidney and liver function are so critical is that patients who have organ dysfunction cannot receive effective chemotherapy.”

During the presentation, Dr. Schlechter reminded attendees that two-thirds of all cancers are cured, and there are clear data showing that chemotherapy in the first-line setting improves quality and length of life in virtually all cases. He underscored how critical it is to get patients treated before they develop organ dysfunction. “We can also use fairly basic clinical and laboratory assessment to determine who has a hyperaggressive malignancy and who doesn’t,” he added. “If LDH [lactate dehydrogenase] or uric acid are elevated, something really dangerous is happening. If the transaminases and alkaline phosphatase are rising, liver function is in danger. If the kidneys are failing, we need to act quickly.”

Dr. Schlechter closed by saying, “There are huge challenges in studying this time frame in a patient’s illness, which is why the initial work-up of cancer remains a high-risk period.”

Hospitalists are on the front lines of diagnosis and management of patients with cancer, the second-leading cause of death in the United States. The session on Oncology Emergencies addressed the enormous number of clinical issues that must be considered within this patient population.

“The real challenge in managing sick cancer patients lies in the data-free zones,” presenter Benjamin L. Schlechter, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “I think the oncologic emergency we forget to talk about most often is the early diagnostic period,” he noted. The focus of Dr. Schlechter’s Monday talk was on this time frame and the process of getting patients with an advanced malignancy from diagnosis to treatment safely, which remains a clinical challenge.

“These patients often present with vague symptoms that do not point to any particular diagnosis,” stated Dr. Schlechter. “Once we identify that a patient has a symptomatic new malignancy, it is critical to determine who needs a rapid work-up as an inpatient on a hospital medicine service and who can be managed as an outpatient.”

Dr. Schlechter explained that there are no randomized trials to guide diagnostic work-up of malignancy or even define an expedited work-up. On the other hand, there are extensive data on treatment of newly diagnosed cancers. Clinical trials that guide first-line cancer therapy have clear eligibility criteria, which should inform hospitalists’ work-ups. “These include torso imaging, biopsy of a metastatic site, and assessment of liver and kidney function,” Dr. Schlechter continued. “The reason kidney and liver function are so critical is that patients who have organ dysfunction cannot receive effective chemotherapy.”

During the presentation, Dr. Schlechter reminded attendees that two-thirds of all cancers are cured, and there are clear data showing that chemotherapy in the first-line setting improves quality and length of life in virtually all cases. He underscored how critical it is to get patients treated before they develop organ dysfunction. “We can also use fairly basic clinical and laboratory assessment to determine who has a hyperaggressive malignancy and who doesn’t,” he added. “If LDH [lactate dehydrogenase] or uric acid are elevated, something really dangerous is happening. If the transaminases and alkaline phosphatase are rising, liver function is in danger. If the kidneys are failing, we need to act quickly.”

Dr. Schlechter closed by saying, “There are huge challenges in studying this time frame in a patient’s illness, which is why the initial work-up of cancer remains a high-risk period.”

Hospitalists are on the front lines of diagnosis and management of patients with cancer, the second-leading cause of death in the United States. The session on Oncology Emergencies addressed the enormous number of clinical issues that must be considered within this patient population.

“The real challenge in managing sick cancer patients lies in the data-free zones,” presenter Benjamin L. Schlechter, MD, of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center in Boston, said in an interview. “I think the oncologic emergency we forget to talk about most often is the early diagnostic period,” he noted. The focus of Dr. Schlechter’s Monday talk was on this time frame and the process of getting patients with an advanced malignancy from diagnosis to treatment safely, which remains a clinical challenge.