User login

Reassurance on general anesthesia in young kids

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Two recent large, well-conducted, and persuasive Jessica Sprague, MD, said at the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“These two studies can be cited in conversation with parents and are very reassuring for a single episode of general anesthesia,” observed Dr. Sprague, a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego.

“As a take home, I think we can feel pretty confident that single exposure to short-duration general anesthesia does not have any adverse neurocognitive effects,” she added.

In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a drug safety communication that general anesthesia lasting for more than 3 hours in children aged less than 3 years, or repeated shorter-duration general anesthesia, may affect the development of children’s brains. This edict caused considerable turmoil among both physicians and parents. The warning was based upon animal studies suggesting adverse effects, including abnormal axon formation and other structural changes, impaired learning and memory, and heightened emotional reactivity to threats. Preliminary human cohort studies generated conflicting results, but were tough to interpret because of potential confounding issues, most prominently the distinct possibility that the very reason the child was undergoing general anesthesia might inherently predispose to neurodevelopmental problems, the dermatologist explained.

Enter the GAS trial, a multinational, assessor-blinded study in which 722 generally healthy infants undergoing hernia repair at 28 centers in the United States and six other countries were randomized to general anesthesia for a median of 54 minutes or awake regional anesthesia. Assessment via a detailed neuropsychological test battery and parent questionnaires at age 2 and 5 years showed no between-group differences at all. Of note, the GAS trial was funded by the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, and similar national health care agencies in the other participating countries (Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393[10172]:664-77).

The other major recent research contribution was a province-wide Ontario study led by investigators at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This retrospective study included 2,346 sibling pairs aged 4-5 years in which one child in each pair received general anesthesia as a preschooler. All participants underwent testing using the comprehensive Early Development Instrument. Reassuringly, no between-group differences were found in any of the five domains assessed by the testing: language and cognitive development, physical health and well-being, emotional health and maturity, social knowledge and competence, and communication skills and general knowledge (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 1;173[1]:29-36).

These two studies address a pressing issue, since 10% of children in the United States and other developed countries receive general anesthesia within their first 3 years of life. Common indications in dermatology include excisional surgery, laser therapy for extensive port wine birthmarks, and diagnostic MRIs.

Dr. Sprague advised that, based upon the new data, “you definitely do not want to delay necessary imaging studies or surgeries, but MRIs can often be done without general anesthesia in infants less than 2 months old. If you have an infant who needs an MRI for something like PHACE syndrome [posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangioma, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, and eye abnormalities], if you can get them in before 2 months of age sometimes you can avoid the general anesthesia if you wrap them tight enough. But once they get over 2 months ,there’s too much wiggle and it’s pretty impossible.”

Her other suggestions:

- Consider delaying nonurgent surgeries and imaging until at least age 6 months and ideally 3 years. “Parents will eventually want surgery to be done for a benign-appearing congenital nevus on the cheek, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be done before 6 months. The same with a residual hemangioma. I would recommend doing it before they go to kindergarten and before they get a sort of sense of what their self looks like, but you have some time between ages 3 and 5 to do that,” Dr. Sprague said.

- Seek out an anesthesiologist who has extensive experience with infants and young children, as is common at a dedicated children’s hospital. “If you live somewhere where the anesthesiologists are primarily seeing adult patients, they’re just not as good,” according to the pediatric dermatologist.

- Definitely consider a topical anesthesia strategy in infants who require multiple procedures, because there remains some unresolved concern about the potential neurodevelopmental impact of multiple bouts of general anesthesia.

Dr. Sprague reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Two recent large, well-conducted, and persuasive Jessica Sprague, MD, said at the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“These two studies can be cited in conversation with parents and are very reassuring for a single episode of general anesthesia,” observed Dr. Sprague, a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego.

“As a take home, I think we can feel pretty confident that single exposure to short-duration general anesthesia does not have any adverse neurocognitive effects,” she added.

In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a drug safety communication that general anesthesia lasting for more than 3 hours in children aged less than 3 years, or repeated shorter-duration general anesthesia, may affect the development of children’s brains. This edict caused considerable turmoil among both physicians and parents. The warning was based upon animal studies suggesting adverse effects, including abnormal axon formation and other structural changes, impaired learning and memory, and heightened emotional reactivity to threats. Preliminary human cohort studies generated conflicting results, but were tough to interpret because of potential confounding issues, most prominently the distinct possibility that the very reason the child was undergoing general anesthesia might inherently predispose to neurodevelopmental problems, the dermatologist explained.

Enter the GAS trial, a multinational, assessor-blinded study in which 722 generally healthy infants undergoing hernia repair at 28 centers in the United States and six other countries were randomized to general anesthesia for a median of 54 minutes or awake regional anesthesia. Assessment via a detailed neuropsychological test battery and parent questionnaires at age 2 and 5 years showed no between-group differences at all. Of note, the GAS trial was funded by the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, and similar national health care agencies in the other participating countries (Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393[10172]:664-77).

The other major recent research contribution was a province-wide Ontario study led by investigators at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This retrospective study included 2,346 sibling pairs aged 4-5 years in which one child in each pair received general anesthesia as a preschooler. All participants underwent testing using the comprehensive Early Development Instrument. Reassuringly, no between-group differences were found in any of the five domains assessed by the testing: language and cognitive development, physical health and well-being, emotional health and maturity, social knowledge and competence, and communication skills and general knowledge (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 1;173[1]:29-36).

These two studies address a pressing issue, since 10% of children in the United States and other developed countries receive general anesthesia within their first 3 years of life. Common indications in dermatology include excisional surgery, laser therapy for extensive port wine birthmarks, and diagnostic MRIs.

Dr. Sprague advised that, based upon the new data, “you definitely do not want to delay necessary imaging studies or surgeries, but MRIs can often be done without general anesthesia in infants less than 2 months old. If you have an infant who needs an MRI for something like PHACE syndrome [posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangioma, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, and eye abnormalities], if you can get them in before 2 months of age sometimes you can avoid the general anesthesia if you wrap them tight enough. But once they get over 2 months ,there’s too much wiggle and it’s pretty impossible.”

Her other suggestions:

- Consider delaying nonurgent surgeries and imaging until at least age 6 months and ideally 3 years. “Parents will eventually want surgery to be done for a benign-appearing congenital nevus on the cheek, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be done before 6 months. The same with a residual hemangioma. I would recommend doing it before they go to kindergarten and before they get a sort of sense of what their self looks like, but you have some time between ages 3 and 5 to do that,” Dr. Sprague said.

- Seek out an anesthesiologist who has extensive experience with infants and young children, as is common at a dedicated children’s hospital. “If you live somewhere where the anesthesiologists are primarily seeing adult patients, they’re just not as good,” according to the pediatric dermatologist.

- Definitely consider a topical anesthesia strategy in infants who require multiple procedures, because there remains some unresolved concern about the potential neurodevelopmental impact of multiple bouts of general anesthesia.

Dr. Sprague reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

LAHAINA, HAWAII – Two recent large, well-conducted, and persuasive Jessica Sprague, MD, said at the SDEF Hawaii Dermatology Seminar provided by the Global Academy for Medical Education/Skin Disease Education Foundation.

“These two studies can be cited in conversation with parents and are very reassuring for a single episode of general anesthesia,” observed Dr. Sprague, a dermatologist at Rady Children’s Hospital and the University of California, both in San Diego.

“As a take home, I think we can feel pretty confident that single exposure to short-duration general anesthesia does not have any adverse neurocognitive effects,” she added.

In 2016, the Food and Drug Administration issued a drug safety communication that general anesthesia lasting for more than 3 hours in children aged less than 3 years, or repeated shorter-duration general anesthesia, may affect the development of children’s brains. This edict caused considerable turmoil among both physicians and parents. The warning was based upon animal studies suggesting adverse effects, including abnormal axon formation and other structural changes, impaired learning and memory, and heightened emotional reactivity to threats. Preliminary human cohort studies generated conflicting results, but were tough to interpret because of potential confounding issues, most prominently the distinct possibility that the very reason the child was undergoing general anesthesia might inherently predispose to neurodevelopmental problems, the dermatologist explained.

Enter the GAS trial, a multinational, assessor-blinded study in which 722 generally healthy infants undergoing hernia repair at 28 centers in the United States and six other countries were randomized to general anesthesia for a median of 54 minutes or awake regional anesthesia. Assessment via a detailed neuropsychological test battery and parent questionnaires at age 2 and 5 years showed no between-group differences at all. Of note, the GAS trial was funded by the FDA, the National Institutes of Health, and similar national health care agencies in the other participating countries (Lancet. 2019 Feb 16;393[10172]:664-77).

The other major recent research contribution was a province-wide Ontario study led by investigators at the Hospital for Sick Children in Toronto. This retrospective study included 2,346 sibling pairs aged 4-5 years in which one child in each pair received general anesthesia as a preschooler. All participants underwent testing using the comprehensive Early Development Instrument. Reassuringly, no between-group differences were found in any of the five domains assessed by the testing: language and cognitive development, physical health and well-being, emotional health and maturity, social knowledge and competence, and communication skills and general knowledge (JAMA Pediatr. 2019 Jan 1;173[1]:29-36).

These two studies address a pressing issue, since 10% of children in the United States and other developed countries receive general anesthesia within their first 3 years of life. Common indications in dermatology include excisional surgery, laser therapy for extensive port wine birthmarks, and diagnostic MRIs.

Dr. Sprague advised that, based upon the new data, “you definitely do not want to delay necessary imaging studies or surgeries, but MRIs can often be done without general anesthesia in infants less than 2 months old. If you have an infant who needs an MRI for something like PHACE syndrome [posterior fossa brain malformations, hemangioma, arterial lesions, cardiac abnormalities, and eye abnormalities], if you can get them in before 2 months of age sometimes you can avoid the general anesthesia if you wrap them tight enough. But once they get over 2 months ,there’s too much wiggle and it’s pretty impossible.”

Her other suggestions:

- Consider delaying nonurgent surgeries and imaging until at least age 6 months and ideally 3 years. “Parents will eventually want surgery to be done for a benign-appearing congenital nevus on the cheek, but it doesn’t necessarily need to be done before 6 months. The same with a residual hemangioma. I would recommend doing it before they go to kindergarten and before they get a sort of sense of what their self looks like, but you have some time between ages 3 and 5 to do that,” Dr. Sprague said.

- Seek out an anesthesiologist who has extensive experience with infants and young children, as is common at a dedicated children’s hospital. “If you live somewhere where the anesthesiologists are primarily seeing adult patients, they’re just not as good,” according to the pediatric dermatologist.

- Definitely consider a topical anesthesia strategy in infants who require multiple procedures, because there remains some unresolved concern about the potential neurodevelopmental impact of multiple bouts of general anesthesia.

Dr. Sprague reported having no financial conflicts regarding her presentation.

The SDEF/Global Academy for Medical Education and this news organization are owned by the same parent company.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM SDEF HAWAII DERMATOLOGY SEMINAR

ARCADIA: Predicting risk of atrial cardiopathy poststroke

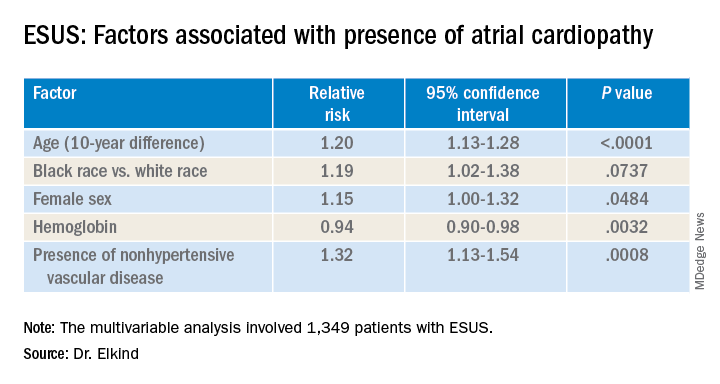

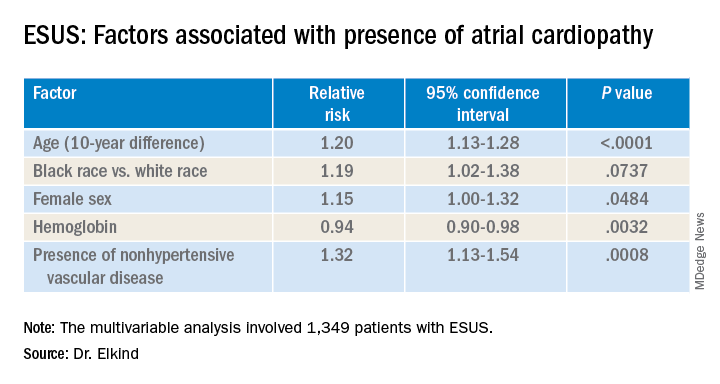

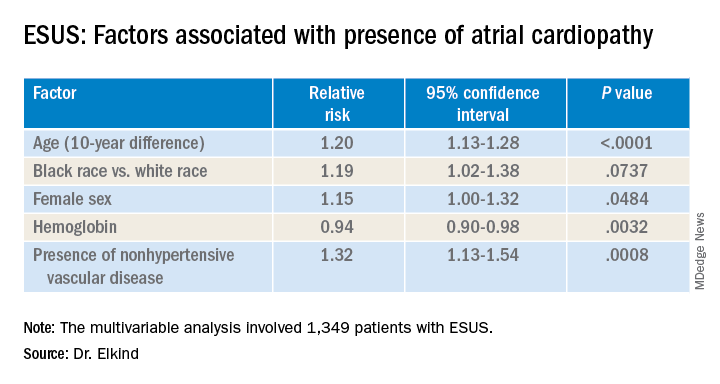

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

LOS ANGELES – Older age, female sex, black race, relative anemia, and a history of cardiovascular disease are associated with greater risk for atrial cardiopathy among people who experienced an embolic stroke of undetermined source (ESUS), new evidence suggests.

Atrial cardiopathy is a suspected cause of ESUS independent of atrial fibrillation. However, clinical predictors to help physicians identify which ESUS patients are at increased risk remain unknown.

The risk for atrial cardiopathy was 34% higher for women versus men with ESUS in this analysis. In addition, black participants had a 29% increased risk, compared with others, and each 10 years of age increased risk for atrial cardiopathy by 30% in an univariable analysis.

“Modest effects of these associations suggest that all ESUS patients, regardless of underlying demographic and risk factors, may have atrial cardiopathy,” principal investigator Mitchell S.V. Elkind, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said when presenting results at the 2020 International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

For this reason, he added, all people with ESUS should be considered for recruitment into the ongoing ARCADIA (AtRial Cardiopathy and Antithrombotic Drugs In Prevention After Cryptogenic Stroke) trial, of which he is one of the principal investigators.

ESUS is a heterogeneous condition, and some patients may be responsive to anticoagulants and some might not, Elkind said. This observation “led us to consider alternative ways for ischemic disease to lead to stroke. We would hypothesize that the underlying atrium can be a risk for stroke by itself.”

Not yet available is the primary efficacy outcome of the multicenter, randomized ARCADIA trial comparing apixaban with aspirin in reducing risk for recurrent stroke of any type. However, Dr. Elkind and colleagues have recruited 1,505 patients to date, enough to analyze factors that predict risk for recurrent stroke among people with evidence of atrial cardiopathy.

All ARCADIA participants are 45 years of age or older and have no history of atrial fibrillation. Atrial cardiopathy was defined by presence of at least one of three biomarkers: N-terminal pro-brain natriuretic peptide (NT-proBNP), P wave terminal force velocity, or evidence of a left atrial diameter of 3 cm/m2 or larger on echocardiography.

Of the 1,349 ARCADIA participants eligible for the current analysis, approximately one-third met one or more of these criteria for atrial cardiopathy.

Those with atrial cardiopathy were “more likely to be black and be women, and tended to have shorter time from stroke to screening,” Dr. Elkind said. In addition, heart failure, hypertension, and peripheral artery disease were more common in those with atrial cardiopathy. This group also was more likely to have an elevation in creatinine and lower hemoglobin and hematocrit levels.

“Heart disease, ischemic heart disease and non-hypertensive vascular disease were significant risk factors” for recurrent stroke in the study, Dr. Elkind added.

Elkind said that, surprisingly, there was no independent association between the time to measurement of NT-proBNP and risk, suggesting that this biomarker “does not rise simply in response to stroke, but reflects a stable condition.”

The multicenter ARCADIA trial is recruiting additional participants at 142 sites now, Dr. Elkind said, “and we are still looking for more sites.”

Which comes first?

“He is looking at what the predictors are for cardiopathy in these patients, which is fascinating for all of us,” session moderator Michelle Christina Johansen, MD, assistant professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, said in an interview when asked to comment.

There is always the conundrum of what came first — the chicken or the egg, Johansen said. Do these patients have stroke that then somehow led to a state that predisposes them to have atrial cardiopathy? Or, rather, was it an atrial cardiopathy state independent of atrial fibrillation that then led to stroke?

“That is why looking at predictors in this population is of such interest,” she said. The study could help identify a subgroup of patients at higher risk for atrial cardiopathy and guide clinical decision-making when patients present with ESUS.

“One of the things I found interesting was that he found that atrial cardiopathy patients were older [a mean 69 years]. This was amazing, because ESUS patients in general tend to be younger,” Dr. Johansen said.

“And there is about a 4-5% risk of recurrence with these patients. So. it was interesting that prior stroke or [transient ischemic attack] was not associated.”*

The National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, the BMS-Pfizer Alliance, and Roche provide funding for ARCADIA. Dr. Elkind and Dr. Johansen disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Elkind M et al. ISC 2020, Abstract 26.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

*Correction, 4/28/20: An earlier version of this article misstated the risk of recurrence.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

CUTIS Celebrates 55 Years

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

When the first issue of Cutis was published in February 1965:

- Alopecia was featured on the cover

- Eugene F. Traub, MD, was Chief Editor, and John T. McCarthy, MD, was Assistant Chief Editor

- The cost of a year's subscription was $10

- The editorial objective was to bring readers "in simple and concise form the latest in diagnosis, prognosis and treatment" with articles "dealing with common dermatoses or those rarer diseases of great interest"

- From the Consultant's Corner answered the question: Is diet actually important in the treatment of acne vulgaris?

To our loyal readers, contributors, and Editorial Board members, thank you for continuing to turn to Cutis for the latest in diagnosis, prognosis, and treatment.

To our new readers, we hope you find our articles in simple and concise form relevant to your practice.

To our resident readers, you are entering one of the most rewarding specialties in medicine—dermatology.

Access past issues of Cutis online.

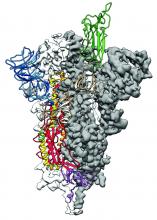

2019-nCoV: Structure, characteristics of key potential therapy target determined

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

Researchers have identified the structure of a protein that could turn out to be a potential vaccine target for the 2019-nCoV.

As is typical of other coronaviruses, 2019-nCoV makes use of a densely glycosylated spike protein to gain entry into host cells. The spike protein is a trimeric class I fusion protein that exists in a metastable prefusion conformation that undergoes a dramatic structural rearrangement to fuse the viral membrane with the host-cell membrane, according to Daniel Wrapp of the University of Texas at Austin and colleagues.

The researchers performed a study to synthesize and determine the 3-D structure of the spike protein because it is a logical target for vaccine development and for the development of targeted therapeutics for COVID-19, the disease caused by the virus.

“As soon as we knew this was a coronavirus, we felt we had to jump at it,” senior author Jason S. McLellan, PhD, associate professor of molecular science, said in a press release from the University, “because we could be one of the first ones to get this structure. We knew exactly what mutations to put into this because we’ve already shown these mutations work for a bunch of other coronaviruses.”

Because recent reports by other researchers demonstrated that 2019-nCoV and SARS-CoV spike proteins share the same functional host-cell receptor–angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2), Dr. McLellan and his colleagues examined the relation between the two viruses. They found biophysical and structural evidence that the 2019-nCoV spike protein binds ACE2 with higher affinity than the closely related SARS-CoV spike protein. “The high affinity of 2019-nCoV S for human ACE2 may contribute to the apparent ease with which 2019-nCoV can spread from human-to-human; however, additional studies are needed to investigate this possibility,” the researchers wrote.

Focusing their attention on the receptor-binding domain (RBD) of the 2019-nCoV spike protein, they tested several published SARS-CoV RBD-specific monoclonal antibodies against it and found that these antibodies showed no appreciable binding to 2019-nCoV spike protein, which suggests limited antibody cross-reactivity. For this reason, they suggested that future antibody isolation and therapeutic design efforts will benefit from specifically using 2019-nCoV spike proteins as probes.

“This information will support precision vaccine design and discovery of anti-viral therapeutics, accelerating medical countermeasure development,” they concluded.

The research was supported in part by an National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases grant and by intramural funding from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases. Four authors are inventors on US patent application No. 62/412,703 (Prefusion Coronavirus Spike Proteins and Their Use) and all are inventors on US patent application No. 62/972,886 (2019-nCoV Vaccine).

SOURCE: Wrapp D et al. Science. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1126/science.abb2507.

FROM SCIENCE

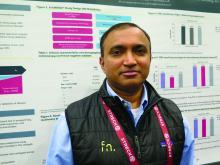

Multiomics blood test outperforms others for CRC

SAN FRANCISCO – A blood-based test that integrates data from multiple molecular “omes,” such as the genome and proteome, performs well at spotting early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC), the AI-EMERGE study suggests.

Moreover, the test netted better sensitivity than a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), a circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) test, and a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test.

Findings were reported in a poster session at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, which is cosponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology.

“Today, about a third of age-appropriate adults are not up to date with [CRC] screening,” lead study investigator Girish Putcha, MD, PhD, chief medical officer of Freenome in San Francisco, noted at the symposium. “A noninvasive blood-based screening test having high sensitivity and specificity for [CRC] generally, but especially for early-stage disease, could help improve adherence and ultimately reduce mortality.”

Dr. Putcha and colleagues evaluated a blood-based multiomics test in 32 patients with CRC of all stages and 539 colonoscopy-confirmed negative control subjects.

The test uses a multiomics platform to pick up both tumor-derived signal and non–tumor-derived signal from the body’s immune response and other sources. The test uses machine learning, and entails whole-genome sequencing, bisulfite sequencing (for assessment of DNA methylation), and protein quantification methods.

At 94% specificity, the test had a 94% sensitivity for spotting stage I and II CRC, 91% sensitivity for stage III and IV CRC, and 91% sensitivity for CRC of any stage. By location, sensitivity was 92% for distal tumors and 88% for proximal tumors.

The multiomics test outperformed a ctDNA test, a CEA test, and a FIT. At a specificity of 96% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than a commercially available FIT stool test (OC-Auto FIT, Polymedco) for stage I and II disease (100% vs. 70%), stage III and IV disease (100% vs. 50%), and any-stage disease (100% vs. 67%).

When set at 100% specificity, the multiomics test outperformed a commercially available plasma ctDNA test (Avenio, Roche) set at 75% specificity. The multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 38%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 55%), and any-stage disease (90% vs. 47%).

At a specificity of 94% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than plasma CEA level for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 18%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 45%), and any-stage disease (91% vs. 31%).

“Although there were many exciting aspects to this study, the test’s ability to detect cancers without loss of sensitivity for early-stage cancers was striking to me,” said Michael J. Hall, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study. “The loss of sensitivity in early tumors has been a limitation of other tests – FOBT [fecal occult blood test], FIT – so if this is replicable, this is exciting.”

Although the study was small for a CRC screening assessment, “the preliminary results presented in the poster were certainly compelling enough to support more research,” Dr. Hall said.

Dr. Putcha said that the test will be validated in a prospective, multicenter trial of roughly 10,000 participants at average risk, expected to open later this year. Further research will also help assess the test’s performance among patients with inflammatory bowel disease, for whom false-positive results with some screening tests have been problematic.

The study was sponsored by Freenome. Dr. Putcha is employed by Freenome and has a relationship with Palmetto GBA. Dr. Hall disclosed relationships with Ambry Genetics, AstraZeneca, Caris Life Sciences, Foundation Medicine, Invitae, and Myriad Genetics, and he shares a patent with institutional colleagues for a novel method to investigate hereditary CRC genes.

SOURCE: Putcha G et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 66.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about currently available CRC screenings at https://www.gastro.org/

SAN FRANCISCO – A blood-based test that integrates data from multiple molecular “omes,” such as the genome and proteome, performs well at spotting early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC), the AI-EMERGE study suggests.

Moreover, the test netted better sensitivity than a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), a circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) test, and a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test.

Findings were reported in a poster session at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, which is cosponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology.

“Today, about a third of age-appropriate adults are not up to date with [CRC] screening,” lead study investigator Girish Putcha, MD, PhD, chief medical officer of Freenome in San Francisco, noted at the symposium. “A noninvasive blood-based screening test having high sensitivity and specificity for [CRC] generally, but especially for early-stage disease, could help improve adherence and ultimately reduce mortality.”

Dr. Putcha and colleagues evaluated a blood-based multiomics test in 32 patients with CRC of all stages and 539 colonoscopy-confirmed negative control subjects.

The test uses a multiomics platform to pick up both tumor-derived signal and non–tumor-derived signal from the body’s immune response and other sources. The test uses machine learning, and entails whole-genome sequencing, bisulfite sequencing (for assessment of DNA methylation), and protein quantification methods.

At 94% specificity, the test had a 94% sensitivity for spotting stage I and II CRC, 91% sensitivity for stage III and IV CRC, and 91% sensitivity for CRC of any stage. By location, sensitivity was 92% for distal tumors and 88% for proximal tumors.

The multiomics test outperformed a ctDNA test, a CEA test, and a FIT. At a specificity of 96% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than a commercially available FIT stool test (OC-Auto FIT, Polymedco) for stage I and II disease (100% vs. 70%), stage III and IV disease (100% vs. 50%), and any-stage disease (100% vs. 67%).

When set at 100% specificity, the multiomics test outperformed a commercially available plasma ctDNA test (Avenio, Roche) set at 75% specificity. The multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 38%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 55%), and any-stage disease (90% vs. 47%).

At a specificity of 94% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than plasma CEA level for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 18%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 45%), and any-stage disease (91% vs. 31%).

“Although there were many exciting aspects to this study, the test’s ability to detect cancers without loss of sensitivity for early-stage cancers was striking to me,” said Michael J. Hall, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study. “The loss of sensitivity in early tumors has been a limitation of other tests – FOBT [fecal occult blood test], FIT – so if this is replicable, this is exciting.”

Although the study was small for a CRC screening assessment, “the preliminary results presented in the poster were certainly compelling enough to support more research,” Dr. Hall said.

Dr. Putcha said that the test will be validated in a prospective, multicenter trial of roughly 10,000 participants at average risk, expected to open later this year. Further research will also help assess the test’s performance among patients with inflammatory bowel disease, for whom false-positive results with some screening tests have been problematic.

The study was sponsored by Freenome. Dr. Putcha is employed by Freenome and has a relationship with Palmetto GBA. Dr. Hall disclosed relationships with Ambry Genetics, AstraZeneca, Caris Life Sciences, Foundation Medicine, Invitae, and Myriad Genetics, and he shares a patent with institutional colleagues for a novel method to investigate hereditary CRC genes.

SOURCE: Putcha G et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 66.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about currently available CRC screenings at https://www.gastro.org/

SAN FRANCISCO – A blood-based test that integrates data from multiple molecular “omes,” such as the genome and proteome, performs well at spotting early-stage colorectal cancer (CRC), the AI-EMERGE study suggests.

Moreover, the test netted better sensitivity than a fecal immunochemical test (FIT), a circulating tumor DNA (ctDNA) test, and a carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) test.

Findings were reported in a poster session at the 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, which is cosponsored by the American Gastroenterological Association, American Society of Clinical Oncology, American Society for Radiation Oncology, and Society of Surgical Oncology.

“Today, about a third of age-appropriate adults are not up to date with [CRC] screening,” lead study investigator Girish Putcha, MD, PhD, chief medical officer of Freenome in San Francisco, noted at the symposium. “A noninvasive blood-based screening test having high sensitivity and specificity for [CRC] generally, but especially for early-stage disease, could help improve adherence and ultimately reduce mortality.”

Dr. Putcha and colleagues evaluated a blood-based multiomics test in 32 patients with CRC of all stages and 539 colonoscopy-confirmed negative control subjects.

The test uses a multiomics platform to pick up both tumor-derived signal and non–tumor-derived signal from the body’s immune response and other sources. The test uses machine learning, and entails whole-genome sequencing, bisulfite sequencing (for assessment of DNA methylation), and protein quantification methods.

At 94% specificity, the test had a 94% sensitivity for spotting stage I and II CRC, 91% sensitivity for stage III and IV CRC, and 91% sensitivity for CRC of any stage. By location, sensitivity was 92% for distal tumors and 88% for proximal tumors.

The multiomics test outperformed a ctDNA test, a CEA test, and a FIT. At a specificity of 96% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than a commercially available FIT stool test (OC-Auto FIT, Polymedco) for stage I and II disease (100% vs. 70%), stage III and IV disease (100% vs. 50%), and any-stage disease (100% vs. 67%).

When set at 100% specificity, the multiomics test outperformed a commercially available plasma ctDNA test (Avenio, Roche) set at 75% specificity. The multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 38%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 55%), and any-stage disease (90% vs. 47%).

At a specificity of 94% for both tests, the multiomics test yielded a higher sensitivity than plasma CEA level for stage I and II disease (94% vs. 18%), stage III and IV disease (91% vs. 45%), and any-stage disease (91% vs. 31%).

“Although there were many exciting aspects to this study, the test’s ability to detect cancers without loss of sensitivity for early-stage cancers was striking to me,” said Michael J. Hall, MD, of Fox Chase Cancer Center in Philadelphia, who was not involved in the study. “The loss of sensitivity in early tumors has been a limitation of other tests – FOBT [fecal occult blood test], FIT – so if this is replicable, this is exciting.”

Although the study was small for a CRC screening assessment, “the preliminary results presented in the poster were certainly compelling enough to support more research,” Dr. Hall said.

Dr. Putcha said that the test will be validated in a prospective, multicenter trial of roughly 10,000 participants at average risk, expected to open later this year. Further research will also help assess the test’s performance among patients with inflammatory bowel disease, for whom false-positive results with some screening tests have been problematic.

The study was sponsored by Freenome. Dr. Putcha is employed by Freenome and has a relationship with Palmetto GBA. Dr. Hall disclosed relationships with Ambry Genetics, AstraZeneca, Caris Life Sciences, Foundation Medicine, Invitae, and Myriad Genetics, and he shares a patent with institutional colleagues for a novel method to investigate hereditary CRC genes.

SOURCE: Putcha G et al. 2020 GI Cancers Symposium, Abstract 66.

Visit the AGA GI Patient Center for education to share with your patients about currently available CRC screenings at https://www.gastro.org/

Banning indoor tanning devices could save lives and money

according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also suggests a ban would result in a collective cost savings of $5.7 billion and productivity gains of $41.3 billion.

Compared with a ban on indoor tanning for minors, the benefits of a full ban on devices were 3.7-fold higher in the United States/Canada and 2.6-fold higher in Europe, according to study author Louisa G. Gordon, PhD, of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

The researchers noted that indoor tanning is regulated in more than 20 countries. Australia has instituted a ban on commercial indoor tanning devices, and Brazil has banned both commercial and private tanning devices.

In the United States, 19 states have banned the use of indoor tanning beds for minors, and 44 states as well as the District of Columbia have some regulation of tanning facilities for minors, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

With this study, Dr. Gordon and colleagues sought to explore what effect an outright ban on indoor tanning devices, a prohibition for minors only, or continuing current levels of indoor tanning would have on the health and economy of the United States, Canada, and Europe.

The researchers created a Markov cohort model of 110,932,523 individuals in the United States/Canada and 141,970,492 individuals in Europe, all aged 12-35 years.

The team used data from epidemiologic studies, cost reports, and official cancer registries to estimate the prevalence of indoor tanning, risk of developing melanoma, and mortality rates from skin cancer and other causes. The researchers also estimated health care costs of melanoma treatment in each region as well as the societal cost of dying prematurely from melanoma, adjusted to 2018 dollars.

Results

The model suggested a ban on indoor tanning in the United States and Canada would result in 244,347 fewer melanomas (–8.7%), 89,193 fewer deaths from melanoma (–6.9%), and 7.3 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–7.8%) than continuing at the current levels of use. The ban would also save 428,781 life-years, have a cost savings of $3.5 billion, and confer productivity gains of $27.5 billion, the researchers said.

When applying the ban in Europe, the model estimated 203,736 fewer melanomas (–4.9%), 98,288 fewer deaths from melanoma (–4.4%), and 2.4 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–4.4%). The researchers also noted that Europe would see a gain of 459,669 life-years, a cost savings of $2.1 billion, and a productivity gain of $13.7 billion.

Dr. Gordon and colleagues acknowledged that their model had some limitations, such as in estimating the prevalence of certain skin cancers across Europe, which can range from 10% to 56% depending on the country. In addition, the model did not account for the money spent in implementing a ban, which could include costs associated with regulation, compliance, and buy-back schemes for tanning devices.

Implications

In an interview, Dr. Gordon said the researchers conducted this study to stress the health benefits and cost savings of regulating indoor tanning devices in North America and Europe. She noted that she had previously published a report in 2009 that helped Australia make the decision to ban such devices there, but she said the tanning industry was in its infancy during that time, which factored into the decision to ban indoor tanning (Health Policy. 2009 Mar;89[3]:303-11).

Any ban by a regulatory agency “should include everyone,” Dr. Gordon said, because “banning minors is a halfway attempt to prevent skin cancers.” The danger isn’t just present in children. “People in their 20s and 30s are still very image conscious,” she said. “The pressure is enormous.”

Anyone interested in tanning should use tanning creams or sprays instead of using indoor tanning devices, Dr. Gordon said. “Consumers can control their UV exposure,” she noted. “Prevention is incredibly important, and skin cancer is one of a few cancers we can almost entirely prevent via protecting our skin. The same can’t be said for other horrible cancers.”

Adam Friedman, MD, a professor at George Washington University, Washington, who was not involved in this study, said it should come as no surprise to dermatologists that preventing artificial UVA heavy exposure reduces the incidence of skin cancer, but the “more compelling component of this study is cost.”

“The lay public is extremely health care cost conscientious,” he said. “This is a commonly debated topic for emerging politicians at every level; not to mention, no one enjoys bleeding money. Dermatologists can use the angle of, ‘save skin now, save money later,’ to target the financial burden of accelerated skin aging and skin cancer as a mechanism for persuading patients not to ‘shake and bake.’ ”

While the Food and Drug Administration has proposed restricting the use of indoor tanning devices for minors nationwide, it has not issued a final rule on the matter, and the prospect of an outright ban in the United States for the general population is less feasible, noted Dr. Friedman.

“I think it would be difficult to expand this [proposed] ban given the financial impact on numerous businesses,” he said. “It would likely take more evidence and support beyond the medical community to make this happen, but here’s hoping,”

This study was funded by the World Health Organization UV Radiation Programme and Cancer Council Victoria. One author disclosed personal fees from Cancer Council Victoria, and one disclosed grants from TrygFonden. The other authors and Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gordon L et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0001.

according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also suggests a ban would result in a collective cost savings of $5.7 billion and productivity gains of $41.3 billion.

Compared with a ban on indoor tanning for minors, the benefits of a full ban on devices were 3.7-fold higher in the United States/Canada and 2.6-fold higher in Europe, according to study author Louisa G. Gordon, PhD, of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

The researchers noted that indoor tanning is regulated in more than 20 countries. Australia has instituted a ban on commercial indoor tanning devices, and Brazil has banned both commercial and private tanning devices.

In the United States, 19 states have banned the use of indoor tanning beds for minors, and 44 states as well as the District of Columbia have some regulation of tanning facilities for minors, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

With this study, Dr. Gordon and colleagues sought to explore what effect an outright ban on indoor tanning devices, a prohibition for minors only, or continuing current levels of indoor tanning would have on the health and economy of the United States, Canada, and Europe.

The researchers created a Markov cohort model of 110,932,523 individuals in the United States/Canada and 141,970,492 individuals in Europe, all aged 12-35 years.

The team used data from epidemiologic studies, cost reports, and official cancer registries to estimate the prevalence of indoor tanning, risk of developing melanoma, and mortality rates from skin cancer and other causes. The researchers also estimated health care costs of melanoma treatment in each region as well as the societal cost of dying prematurely from melanoma, adjusted to 2018 dollars.

Results

The model suggested a ban on indoor tanning in the United States and Canada would result in 244,347 fewer melanomas (–8.7%), 89,193 fewer deaths from melanoma (–6.9%), and 7.3 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–7.8%) than continuing at the current levels of use. The ban would also save 428,781 life-years, have a cost savings of $3.5 billion, and confer productivity gains of $27.5 billion, the researchers said.

When applying the ban in Europe, the model estimated 203,736 fewer melanomas (–4.9%), 98,288 fewer deaths from melanoma (–4.4%), and 2.4 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–4.4%). The researchers also noted that Europe would see a gain of 459,669 life-years, a cost savings of $2.1 billion, and a productivity gain of $13.7 billion.

Dr. Gordon and colleagues acknowledged that their model had some limitations, such as in estimating the prevalence of certain skin cancers across Europe, which can range from 10% to 56% depending on the country. In addition, the model did not account for the money spent in implementing a ban, which could include costs associated with regulation, compliance, and buy-back schemes for tanning devices.

Implications

In an interview, Dr. Gordon said the researchers conducted this study to stress the health benefits and cost savings of regulating indoor tanning devices in North America and Europe. She noted that she had previously published a report in 2009 that helped Australia make the decision to ban such devices there, but she said the tanning industry was in its infancy during that time, which factored into the decision to ban indoor tanning (Health Policy. 2009 Mar;89[3]:303-11).

Any ban by a regulatory agency “should include everyone,” Dr. Gordon said, because “banning minors is a halfway attempt to prevent skin cancers.” The danger isn’t just present in children. “People in their 20s and 30s are still very image conscious,” she said. “The pressure is enormous.”

Anyone interested in tanning should use tanning creams or sprays instead of using indoor tanning devices, Dr. Gordon said. “Consumers can control their UV exposure,” she noted. “Prevention is incredibly important, and skin cancer is one of a few cancers we can almost entirely prevent via protecting our skin. The same can’t be said for other horrible cancers.”

Adam Friedman, MD, a professor at George Washington University, Washington, who was not involved in this study, said it should come as no surprise to dermatologists that preventing artificial UVA heavy exposure reduces the incidence of skin cancer, but the “more compelling component of this study is cost.”

“The lay public is extremely health care cost conscientious,” he said. “This is a commonly debated topic for emerging politicians at every level; not to mention, no one enjoys bleeding money. Dermatologists can use the angle of, ‘save skin now, save money later,’ to target the financial burden of accelerated skin aging and skin cancer as a mechanism for persuading patients not to ‘shake and bake.’ ”

While the Food and Drug Administration has proposed restricting the use of indoor tanning devices for minors nationwide, it has not issued a final rule on the matter, and the prospect of an outright ban in the United States for the general population is less feasible, noted Dr. Friedman.

“I think it would be difficult to expand this [proposed] ban given the financial impact on numerous businesses,” he said. “It would likely take more evidence and support beyond the medical community to make this happen, but here’s hoping,”

This study was funded by the World Health Organization UV Radiation Programme and Cancer Council Victoria. One author disclosed personal fees from Cancer Council Victoria, and one disclosed grants from TrygFonden. The other authors and Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gordon L et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0001.

according to a study published in JAMA Dermatology.

The study also suggests a ban would result in a collective cost savings of $5.7 billion and productivity gains of $41.3 billion.

Compared with a ban on indoor tanning for minors, the benefits of a full ban on devices were 3.7-fold higher in the United States/Canada and 2.6-fold higher in Europe, according to study author Louisa G. Gordon, PhD, of the QIMR Berghofer Medical Research Institute in Brisbane, Australia, and colleagues.

The researchers noted that indoor tanning is regulated in more than 20 countries. Australia has instituted a ban on commercial indoor tanning devices, and Brazil has banned both commercial and private tanning devices.

In the United States, 19 states have banned the use of indoor tanning beds for minors, and 44 states as well as the District of Columbia have some regulation of tanning facilities for minors, according to the National Conference of State Legislatures.

With this study, Dr. Gordon and colleagues sought to explore what effect an outright ban on indoor tanning devices, a prohibition for minors only, or continuing current levels of indoor tanning would have on the health and economy of the United States, Canada, and Europe.

The researchers created a Markov cohort model of 110,932,523 individuals in the United States/Canada and 141,970,492 individuals in Europe, all aged 12-35 years.

The team used data from epidemiologic studies, cost reports, and official cancer registries to estimate the prevalence of indoor tanning, risk of developing melanoma, and mortality rates from skin cancer and other causes. The researchers also estimated health care costs of melanoma treatment in each region as well as the societal cost of dying prematurely from melanoma, adjusted to 2018 dollars.

Results

The model suggested a ban on indoor tanning in the United States and Canada would result in 244,347 fewer melanomas (–8.7%), 89,193 fewer deaths from melanoma (–6.9%), and 7.3 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–7.8%) than continuing at the current levels of use. The ban would also save 428,781 life-years, have a cost savings of $3.5 billion, and confer productivity gains of $27.5 billion, the researchers said.

When applying the ban in Europe, the model estimated 203,736 fewer melanomas (–4.9%), 98,288 fewer deaths from melanoma (–4.4%), and 2.4 million fewer keratinocyte carcinomas (–4.4%). The researchers also noted that Europe would see a gain of 459,669 life-years, a cost savings of $2.1 billion, and a productivity gain of $13.7 billion.

Dr. Gordon and colleagues acknowledged that their model had some limitations, such as in estimating the prevalence of certain skin cancers across Europe, which can range from 10% to 56% depending on the country. In addition, the model did not account for the money spent in implementing a ban, which could include costs associated with regulation, compliance, and buy-back schemes for tanning devices.

Implications

In an interview, Dr. Gordon said the researchers conducted this study to stress the health benefits and cost savings of regulating indoor tanning devices in North America and Europe. She noted that she had previously published a report in 2009 that helped Australia make the decision to ban such devices there, but she said the tanning industry was in its infancy during that time, which factored into the decision to ban indoor tanning (Health Policy. 2009 Mar;89[3]:303-11).

Any ban by a regulatory agency “should include everyone,” Dr. Gordon said, because “banning minors is a halfway attempt to prevent skin cancers.” The danger isn’t just present in children. “People in their 20s and 30s are still very image conscious,” she said. “The pressure is enormous.”

Anyone interested in tanning should use tanning creams or sprays instead of using indoor tanning devices, Dr. Gordon said. “Consumers can control their UV exposure,” she noted. “Prevention is incredibly important, and skin cancer is one of a few cancers we can almost entirely prevent via protecting our skin. The same can’t be said for other horrible cancers.”

Adam Friedman, MD, a professor at George Washington University, Washington, who was not involved in this study, said it should come as no surprise to dermatologists that preventing artificial UVA heavy exposure reduces the incidence of skin cancer, but the “more compelling component of this study is cost.”

“The lay public is extremely health care cost conscientious,” he said. “This is a commonly debated topic for emerging politicians at every level; not to mention, no one enjoys bleeding money. Dermatologists can use the angle of, ‘save skin now, save money later,’ to target the financial burden of accelerated skin aging and skin cancer as a mechanism for persuading patients not to ‘shake and bake.’ ”

While the Food and Drug Administration has proposed restricting the use of indoor tanning devices for minors nationwide, it has not issued a final rule on the matter, and the prospect of an outright ban in the United States for the general population is less feasible, noted Dr. Friedman.

“I think it would be difficult to expand this [proposed] ban given the financial impact on numerous businesses,” he said. “It would likely take more evidence and support beyond the medical community to make this happen, but here’s hoping,”

This study was funded by the World Health Organization UV Radiation Programme and Cancer Council Victoria. One author disclosed personal fees from Cancer Council Victoria, and one disclosed grants from TrygFonden. The other authors and Dr. Friedman reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gordon L et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Feb 19. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.0001.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Shingles vaccine linked to lower stroke risk

LOS ANGELES – Prevention of shingles with the Zoster Vaccine Live may reduce the risk of subsequent stroke among older adults as well, the first study to examine this association suggests. Shingles vaccination was linked to a 20% decrease in stroke risk in people younger than 80 years of age in the large Medicare cohort study. Older participants showed a 10% reduced risk, according to data released in advance of formal presentation at this week’s International Stroke Conference, sponsored by the American Heart Association.

Reductions were seen for both ischemic and hemorrhagic events.

“Our findings might encourage people age 50 or older to get vaccinated against shingles and to prevent shingles-associated stroke risk,” Quanhe Yang, PhD, lead study author and senior scientist at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, said in an interview.

Dr. Yang and colleagues evaluated the only shingles vaccine available at the time of the study, Zoster Vaccine Live (Zostavax). However, the CDC now calls an adjuvanted, nonlive recombinant vaccine (Shingrix) the preferred shingles vaccine for healthy adults aged 50 years and older. Shingrix was approved in 2017. Zostavax, approved in 2006, can still be used in healthy adults aged 60 years and older, the agency states.

A reduction in inflammation from Zoster Vaccine Live may be the mechanism by which stroke risk is reduced, Dr. Yang said. The newer vaccine, which the CDC notes is more than 90% effective, might provide even greater protection against stroke, although more research is needed, he added.

Interestingly, prior research suggested that, once a person develops shingles, it may be too late. Dr. Yang and colleagues showed vaccination or antiviral treatment after a shingles episode was not effective at reducing stroke risk in research presented at the 2019 International Stroke Conference.

Shingles can present as a painful reactivation of chickenpox, also known as the varicella-zoster virus. Shingles is also common; Dr. Yang estimated one in three people who had chickenpox will develop the condition at some point in their lifetime. In addition, researchers have linked shingles to an elevated risk of stroke.

To assess the vaccine’s protective effect on stroke, Dr. Yang and colleagues reviewed health records for 1.38 million Medicare recipients. All participants were aged 66 years or older, had no history of stroke at baseline, and received the Zoster Vaccine Live during 2008-2016. The investigators compared the stroke rate in this vaccinated group with the rate in a matched control group of the same number of Medicare fee-for-service beneficiaries who did not receive the vaccination. They adjusted their analysis for age, sex, race, medications, and comorbidities.

The overall decrease of 16% in stroke risk associated with vaccination included a 12% drop in hemorrhagic stroke and 18% decrease in ischemic stroke over a median follow-up of 3.9 years follow-up (interquartile range, 2.7-5.4).

The adjusted hazard ratios comparing the vaccinated with control groups were 0.84 (95% confidence interval, 0.83-0.85) for all stroke; 0.82 (95% CI, 0.81-0.83) for acute ischemic stroke; and 0.88 (95% CI, 0.84-0.91) for hemorrhagic stroke.

The vaccinated group experienced 42,267 stroke events during that time. This rate included 33,510 acute ischemic strokes and 4,318 hemorrhagic strokes. At the same time, 48,139 strokes occurred in the control group. The breakdown included 39,334 ischemic and 4,713 hemorrhagic events.

“Approximately 1 million people in the United States get shingles each year, yet there is a vaccine to help prevent it,” Dr. Yang stated in a news release. “Our study results may encourage people ages 50 and older to follow the recommendation and get vaccinated against shingles. You are reducing the risk of shingles, and at the same time, you may be reducing your risk of stroke.”

“Further studies are needed to confirm our findings of association between Zostavax vaccine and risk of stroke,” Dr. Yang said.

Because the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommended Shingrix vaccine only for healthy adults 50 years and older in 2017, there were insufficient data in Medicare to study the association between that vaccine and risk of stroke at the time of the current study.

“However, two doses of Shingrix are more than 90% effective at preventing shingles and postherpetic neuralgia, and higher than that of Zostavax,” Dr. Yang said.

‘Very intriguing’ research

“This is a very interesting study,” Ralph L. Sacco, MD, past president of the American Heart Association, said in a video commentary released in advance of the conference. It was a very large sample, he noted, and those older than age 60 years who had the vaccine were protected with a lower risk for both ischemic and hemorrhagic stroke.

“So it is very intriguing,” added Dr. Sacco, chairman of the department of neurology at the University of Miami. “We know things like shingles can increase inflammation and increase the risk of stroke,” Dr. Sacco said, “but this is the first time in a very large Medicare database that it was shown that those who had the vaccine had a lower risk of stroke.”

The CDC funded this study. Dr. Yang and Dr. Sacco have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

SOURCE: Yang Q et al. ISC 2020, Abstract TP493.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.