User login

Treating VIN while preventing recurrence

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a distressing condition that may require painful and disfiguring treatments. It is particularly problematic because more than a quarter of patients will experience recurrence of their disease after primary therapy. In this column we will explore the risk factors for recurrence, recommendations for early detection, and options to minimize its incidence.

VIN was traditionally characterized in three stages (I, II, III). However, as it became better understood that the previously named VIN I was not, in fact, a precursor for malignancy, but rather a benign manifestation of low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, it was removed from consideration as VIN. Furthermore, our understanding of VIN grew to recognize that there were two developmental pathways to vulvar neoplasia and malignancy. The first was via high-risk HPV infection, often with tobacco exposure as an accelerating factor, and typically among younger women. This has been named “usual type VIN” (uVIN). The second arises in the background of lichen sclerosus in older women and is named “differentiated type VIN” (dVIN). This type carries with it a higher risk for progression to cancer, coexisting in approximately 80% of cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, the progression to cancer appears to occur more quickly for dVIN lesions (22 months compared with 41 months in uVIN).1

While observation of VIN can be considered for young, asymptomatic women, it is not universally recommended because the risk of progression to cancer is approximately 8% (5% for uVIN and 33% for dVIN).1,2 Both subtypes of VIN can be treated with similar interventions including surgical excision (typically a wide local excision), ablative therapies (such as CO2 laser) or topical medical therapy such as imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil. (false-negative biopsies), and adequacy of margin status. However, given the proximity of this disease to vital structures such as the clitoris, urethral meatus, and anal verge, as well as issues with wound healing, and difficulty with reapproximation of vulvar tissues – particularly when large or multifocal disease is present – sometimes multimodal treatments or medical therapies are preferred to spare disfigurement or sexual, bladder, or bowel dysfunction.

Excision of VIN need not be deeper than the epidermis, although including a limited degree of dermis protects against incomplete resection of occult, coexisting early invasive disease. However, wide margins should ideally be at least 10 mm. This can prove to be a challenging goal for multiple reasons. First, while there are visual stigmata of VIN, its true extent can be determined only microscopically. In addition, the disease may be multifocal. Furthermore, particularly where it encroaches upon the anus, clitoris, or urethral meatus, resection margins may be limited because of the desire to preserve function of adjacent structures. The application of 2%-5% acetic acid in the operating room prior to marking the planned borders of excision can optimize the likelihood that the incisions will encompass the microscopic extent of VIN. As it does with cervical dysplasia, acetic acid is thought to cause reversible coagulation of nuclear proteins and cytokeratins, which are more abundant in dysplastic lesions, thus appearing white to the surgeon’s eye.

However, even with the surgeon’s best attempts to excise all disease, approximately half of VIN excisions will have positive margins. Fortunately, not all of these patients will go on to develop recurrent dysplasia. In fact, less than half of women with positive margins on excision will develop recurrent VIN disease.2 This incomplete incidence of recurrence may be in part due to an ablative effect of inflammation at the cut skin edges. Therefore, provided that there is no macroscopic disease remaining, close observation, rather than immediate reexcision, is recommended.

Positive excisional margins are a major risk factor for recurrence, carrying an eightfold increased risk, and also are associated with a more rapid onset of recurrence than for those with negative margins. Other predisposing risk factors for recurrence include advancing age, coexistence of dysplasia at other lower genital sites (including vaginal and cervical), immunosuppressive conditions or therapies (especially steroid use), HPV exposure, and the presence of lichen sclerosus.2 Continued tobacco use is a modifiable risk factor that has been shown to be associated with an increased recurrence risk of VIN. We should take the opportunity in the postoperative and surveillance period to educate our patients regarding the importance of smoking cessation in modifying their risk for recurrent or new disease.

HPV infection may not be a modifiable risk factor, but certainly can be prevented by encouraging the adoption of HPV vaccination.

Topical steroids used to treat lichen sclerosus can improve symptoms of this vulvar dystrophy as well as decrease the incidence of recurrent dVIN and invasive vulvar cancer. Treatment should continue until the skin has normalized its appearance and texture. This may involve chronic long-term therapy.3

Recognizing that more than a quarter of patients will recur, the recommended posttreatment follow-up for VIN is at 6 months, 12 months, and then annually. It should include close inspection of the vulva with consideration of application of topical 2%-5% acetic acid (I typically apply this with a soaked gauze sponge) and vulvar colposcopy (a hand-held magnification glass works well for this purpose). Patients should be counseled regarding their high risk for recurrence, informed of typical symptoms, and encouraged to perform regular vulva self-inspection (with use of a hand mirror).

For patients at the highest risk for recurrence (older patients, patients with positive excisional margins, HPV coinfection, lichen sclerosus, tobacco use, and immunosuppression), I recommend 6 monthly follow-up surveillance for 5 years. Most (75%) of recurrences will occur with the first 43 months after diagnosis with half occurring in the first 18 months.2 Patients who have had positive margins on their excisional specimen are at the highest risk for an earlier recurrence.

VIN is an insidious disease with a high recurrence rate. It is challenging to completely resect with negative margins. Patients with a history of VIN should receive close observation in the years following their excision, particularly if resection margins were positive, and clinicians should attempt to modify risk factors wherever possible, paying particularly close attention to older postmenopausal women with a history of lichen sclerosus as progression to malignancy is highest for these women.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Pathology. 2016 Jun 1;48(4)291-302.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jan;148(1):126-31.

3. JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Oct;151(10):1061-7.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a distressing condition that may require painful and disfiguring treatments. It is particularly problematic because more than a quarter of patients will experience recurrence of their disease after primary therapy. In this column we will explore the risk factors for recurrence, recommendations for early detection, and options to minimize its incidence.

VIN was traditionally characterized in three stages (I, II, III). However, as it became better understood that the previously named VIN I was not, in fact, a precursor for malignancy, but rather a benign manifestation of low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, it was removed from consideration as VIN. Furthermore, our understanding of VIN grew to recognize that there were two developmental pathways to vulvar neoplasia and malignancy. The first was via high-risk HPV infection, often with tobacco exposure as an accelerating factor, and typically among younger women. This has been named “usual type VIN” (uVIN). The second arises in the background of lichen sclerosus in older women and is named “differentiated type VIN” (dVIN). This type carries with it a higher risk for progression to cancer, coexisting in approximately 80% of cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, the progression to cancer appears to occur more quickly for dVIN lesions (22 months compared with 41 months in uVIN).1

While observation of VIN can be considered for young, asymptomatic women, it is not universally recommended because the risk of progression to cancer is approximately 8% (5% for uVIN and 33% for dVIN).1,2 Both subtypes of VIN can be treated with similar interventions including surgical excision (typically a wide local excision), ablative therapies (such as CO2 laser) or topical medical therapy such as imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil. (false-negative biopsies), and adequacy of margin status. However, given the proximity of this disease to vital structures such as the clitoris, urethral meatus, and anal verge, as well as issues with wound healing, and difficulty with reapproximation of vulvar tissues – particularly when large or multifocal disease is present – sometimes multimodal treatments or medical therapies are preferred to spare disfigurement or sexual, bladder, or bowel dysfunction.

Excision of VIN need not be deeper than the epidermis, although including a limited degree of dermis protects against incomplete resection of occult, coexisting early invasive disease. However, wide margins should ideally be at least 10 mm. This can prove to be a challenging goal for multiple reasons. First, while there are visual stigmata of VIN, its true extent can be determined only microscopically. In addition, the disease may be multifocal. Furthermore, particularly where it encroaches upon the anus, clitoris, or urethral meatus, resection margins may be limited because of the desire to preserve function of adjacent structures. The application of 2%-5% acetic acid in the operating room prior to marking the planned borders of excision can optimize the likelihood that the incisions will encompass the microscopic extent of VIN. As it does with cervical dysplasia, acetic acid is thought to cause reversible coagulation of nuclear proteins and cytokeratins, which are more abundant in dysplastic lesions, thus appearing white to the surgeon’s eye.

However, even with the surgeon’s best attempts to excise all disease, approximately half of VIN excisions will have positive margins. Fortunately, not all of these patients will go on to develop recurrent dysplasia. In fact, less than half of women with positive margins on excision will develop recurrent VIN disease.2 This incomplete incidence of recurrence may be in part due to an ablative effect of inflammation at the cut skin edges. Therefore, provided that there is no macroscopic disease remaining, close observation, rather than immediate reexcision, is recommended.

Positive excisional margins are a major risk factor for recurrence, carrying an eightfold increased risk, and also are associated with a more rapid onset of recurrence than for those with negative margins. Other predisposing risk factors for recurrence include advancing age, coexistence of dysplasia at other lower genital sites (including vaginal and cervical), immunosuppressive conditions or therapies (especially steroid use), HPV exposure, and the presence of lichen sclerosus.2 Continued tobacco use is a modifiable risk factor that has been shown to be associated with an increased recurrence risk of VIN. We should take the opportunity in the postoperative and surveillance period to educate our patients regarding the importance of smoking cessation in modifying their risk for recurrent or new disease.

HPV infection may not be a modifiable risk factor, but certainly can be prevented by encouraging the adoption of HPV vaccination.

Topical steroids used to treat lichen sclerosus can improve symptoms of this vulvar dystrophy as well as decrease the incidence of recurrent dVIN and invasive vulvar cancer. Treatment should continue until the skin has normalized its appearance and texture. This may involve chronic long-term therapy.3

Recognizing that more than a quarter of patients will recur, the recommended posttreatment follow-up for VIN is at 6 months, 12 months, and then annually. It should include close inspection of the vulva with consideration of application of topical 2%-5% acetic acid (I typically apply this with a soaked gauze sponge) and vulvar colposcopy (a hand-held magnification glass works well for this purpose). Patients should be counseled regarding their high risk for recurrence, informed of typical symptoms, and encouraged to perform regular vulva self-inspection (with use of a hand mirror).

For patients at the highest risk for recurrence (older patients, patients with positive excisional margins, HPV coinfection, lichen sclerosus, tobacco use, and immunosuppression), I recommend 6 monthly follow-up surveillance for 5 years. Most (75%) of recurrences will occur with the first 43 months after diagnosis with half occurring in the first 18 months.2 Patients who have had positive margins on their excisional specimen are at the highest risk for an earlier recurrence.

VIN is an insidious disease with a high recurrence rate. It is challenging to completely resect with negative margins. Patients with a history of VIN should receive close observation in the years following their excision, particularly if resection margins were positive, and clinicians should attempt to modify risk factors wherever possible, paying particularly close attention to older postmenopausal women with a history of lichen sclerosus as progression to malignancy is highest for these women.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Pathology. 2016 Jun 1;48(4)291-302.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jan;148(1):126-31.

3. JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Oct;151(10):1061-7.

Vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) is a distressing condition that may require painful and disfiguring treatments. It is particularly problematic because more than a quarter of patients will experience recurrence of their disease after primary therapy. In this column we will explore the risk factors for recurrence, recommendations for early detection, and options to minimize its incidence.

VIN was traditionally characterized in three stages (I, II, III). However, as it became better understood that the previously named VIN I was not, in fact, a precursor for malignancy, but rather a benign manifestation of low-risk human papillomavirus (HPV) infection, it was removed from consideration as VIN. Furthermore, our understanding of VIN grew to recognize that there were two developmental pathways to vulvar neoplasia and malignancy. The first was via high-risk HPV infection, often with tobacco exposure as an accelerating factor, and typically among younger women. This has been named “usual type VIN” (uVIN). The second arises in the background of lichen sclerosus in older women and is named “differentiated type VIN” (dVIN). This type carries with it a higher risk for progression to cancer, coexisting in approximately 80% of cases of invasive squamous cell carcinoma. In addition, the progression to cancer appears to occur more quickly for dVIN lesions (22 months compared with 41 months in uVIN).1

While observation of VIN can be considered for young, asymptomatic women, it is not universally recommended because the risk of progression to cancer is approximately 8% (5% for uVIN and 33% for dVIN).1,2 Both subtypes of VIN can be treated with similar interventions including surgical excision (typically a wide local excision), ablative therapies (such as CO2 laser) or topical medical therapy such as imiquimod or 5-fluorouracil. (false-negative biopsies), and adequacy of margin status. However, given the proximity of this disease to vital structures such as the clitoris, urethral meatus, and anal verge, as well as issues with wound healing, and difficulty with reapproximation of vulvar tissues – particularly when large or multifocal disease is present – sometimes multimodal treatments or medical therapies are preferred to spare disfigurement or sexual, bladder, or bowel dysfunction.

Excision of VIN need not be deeper than the epidermis, although including a limited degree of dermis protects against incomplete resection of occult, coexisting early invasive disease. However, wide margins should ideally be at least 10 mm. This can prove to be a challenging goal for multiple reasons. First, while there are visual stigmata of VIN, its true extent can be determined only microscopically. In addition, the disease may be multifocal. Furthermore, particularly where it encroaches upon the anus, clitoris, or urethral meatus, resection margins may be limited because of the desire to preserve function of adjacent structures. The application of 2%-5% acetic acid in the operating room prior to marking the planned borders of excision can optimize the likelihood that the incisions will encompass the microscopic extent of VIN. As it does with cervical dysplasia, acetic acid is thought to cause reversible coagulation of nuclear proteins and cytokeratins, which are more abundant in dysplastic lesions, thus appearing white to the surgeon’s eye.

However, even with the surgeon’s best attempts to excise all disease, approximately half of VIN excisions will have positive margins. Fortunately, not all of these patients will go on to develop recurrent dysplasia. In fact, less than half of women with positive margins on excision will develop recurrent VIN disease.2 This incomplete incidence of recurrence may be in part due to an ablative effect of inflammation at the cut skin edges. Therefore, provided that there is no macroscopic disease remaining, close observation, rather than immediate reexcision, is recommended.

Positive excisional margins are a major risk factor for recurrence, carrying an eightfold increased risk, and also are associated with a more rapid onset of recurrence than for those with negative margins. Other predisposing risk factors for recurrence include advancing age, coexistence of dysplasia at other lower genital sites (including vaginal and cervical), immunosuppressive conditions or therapies (especially steroid use), HPV exposure, and the presence of lichen sclerosus.2 Continued tobacco use is a modifiable risk factor that has been shown to be associated with an increased recurrence risk of VIN. We should take the opportunity in the postoperative and surveillance period to educate our patients regarding the importance of smoking cessation in modifying their risk for recurrent or new disease.

HPV infection may not be a modifiable risk factor, but certainly can be prevented by encouraging the adoption of HPV vaccination.

Topical steroids used to treat lichen sclerosus can improve symptoms of this vulvar dystrophy as well as decrease the incidence of recurrent dVIN and invasive vulvar cancer. Treatment should continue until the skin has normalized its appearance and texture. This may involve chronic long-term therapy.3

Recognizing that more than a quarter of patients will recur, the recommended posttreatment follow-up for VIN is at 6 months, 12 months, and then annually. It should include close inspection of the vulva with consideration of application of topical 2%-5% acetic acid (I typically apply this with a soaked gauze sponge) and vulvar colposcopy (a hand-held magnification glass works well for this purpose). Patients should be counseled regarding their high risk for recurrence, informed of typical symptoms, and encouraged to perform regular vulva self-inspection (with use of a hand mirror).

For patients at the highest risk for recurrence (older patients, patients with positive excisional margins, HPV coinfection, lichen sclerosus, tobacco use, and immunosuppression), I recommend 6 monthly follow-up surveillance for 5 years. Most (75%) of recurrences will occur with the first 43 months after diagnosis with half occurring in the first 18 months.2 Patients who have had positive margins on their excisional specimen are at the highest risk for an earlier recurrence.

VIN is an insidious disease with a high recurrence rate. It is challenging to completely resect with negative margins. Patients with a history of VIN should receive close observation in the years following their excision, particularly if resection margins were positive, and clinicians should attempt to modify risk factors wherever possible, paying particularly close attention to older postmenopausal women with a history of lichen sclerosus as progression to malignancy is highest for these women.

Dr. Rossi is assistant professor in the division of gynecologic oncology at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. She said she had no relevant financial disclosures. Email Dr. Rossi at [email protected].

References

1. Pathology. 2016 Jun 1;48(4)291-302.

2. Gynecol Oncol. 2018 Jan;148(1):126-31.

3. JAMA Dermatol. 2015 Oct;151(10):1061-7.

Hypertension medication adjustment less likely with polypill

A secondary analysis of a major study of polypill therapy for hypertension found that patients who don’t reach blood pressure targets are less likely to have their medications adjusted if they’re on fixed-dose combination therapy.

However, hypertension patients on low-dose, triple-pill combination therapy are more likely to achieve blood pressure control than are those on usual care.

The secondary analysis of Triple Pill vs. Usual Care Management for Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Hypertension (TRIUMPH) was published online in JAMA Cardiology (2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739). The trial randomized 700 patients with hypertension in Sri Lanka to triple-pill fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapy or usual care during February 2016–May 2017, with follow-up ending in October 2017.

A greater proportion of FDC patients reached target BP by the end of the study compared with usual care, 70% vs. 55%. However, the study found that therapeutic inertia – the failure to intensify therapy in nonresponsive patients – was more common in the FDC group at 6- and 12-week follow-up: 87% vs. 64% and 90% vs. 65%, respectively; both differences were significant different at P < .001).

The once-daily FDC pill contained telmisartan 20 mg, amlodipine 2.5 mg; and chlorthalidone 12.5 mg.

“Using a triple low-dose combination blood-pressure pill reduced the need to uptitrate BP therapy as more patients are at target, but doctors were less likely to uptitrate with triple-pill therapy when it was needed,” lead author Nelson Wang, MD, a research fellow at the George Institute for Global Health in suburban Sydney, said in an interview.

“Overall, there were fewer treatment inertia episodes in the triple-pill group than in the usual care group, but this was driven by the fact that fewer triple-pill patients needed uptitration when coming to their follow-up visits,” Dr. Wang added.

The analysis found that clinicians who prescribed triple-pill FDC used 23 unique drug treatment regimens per 100 treated patients compared with 54 different regiments with usual care (P < .001). “There was a large simplification in care,” Dr. Wang said of the FDC approach.

Dr. Wang and colleagues called for greater efforts to address therapeutic inertia, particularly with FDC therapies, and suggested potential strategies consisting of patient education, incentives for appropriate treatment adjustments, and feedback mechanisms and reminders for physicians.

“There may also be a need for more dosage options with the FDC triple pill to allow physicians to intensify therapy without fear of overtreatment and adverse drug effects,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2693), Ann Marie Navar, MD, PhD, associate professor of cardiology at Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., noted that initiating treatment with FDC therapy doesn’t preclude a more personalized approach for patients who don’t achieve their BP target. “The real choice now is the choice of initial treatment,” she wrote, adding that future treatment guidelines should consider extending an FDC-first approach to patients with less severe levels of hypertension.

“The study showed there’s room for a both a population-based fixed-drug combination approach and a personalized approach to how we think about hypertension management with fixed-dose therapy,” she said in an interview. “It’s not a one-and-done situation.”

Dr. Wang has no financial relationships to disclose. Study coauthors received funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Navar has no relevant financial relationships to report.

SOURCE: Wang N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739.

A secondary analysis of a major study of polypill therapy for hypertension found that patients who don’t reach blood pressure targets are less likely to have their medications adjusted if they’re on fixed-dose combination therapy.

However, hypertension patients on low-dose, triple-pill combination therapy are more likely to achieve blood pressure control than are those on usual care.

The secondary analysis of Triple Pill vs. Usual Care Management for Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Hypertension (TRIUMPH) was published online in JAMA Cardiology (2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739). The trial randomized 700 patients with hypertension in Sri Lanka to triple-pill fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapy or usual care during February 2016–May 2017, with follow-up ending in October 2017.

A greater proportion of FDC patients reached target BP by the end of the study compared with usual care, 70% vs. 55%. However, the study found that therapeutic inertia – the failure to intensify therapy in nonresponsive patients – was more common in the FDC group at 6- and 12-week follow-up: 87% vs. 64% and 90% vs. 65%, respectively; both differences were significant different at P < .001).

The once-daily FDC pill contained telmisartan 20 mg, amlodipine 2.5 mg; and chlorthalidone 12.5 mg.

“Using a triple low-dose combination blood-pressure pill reduced the need to uptitrate BP therapy as more patients are at target, but doctors were less likely to uptitrate with triple-pill therapy when it was needed,” lead author Nelson Wang, MD, a research fellow at the George Institute for Global Health in suburban Sydney, said in an interview.

“Overall, there were fewer treatment inertia episodes in the triple-pill group than in the usual care group, but this was driven by the fact that fewer triple-pill patients needed uptitration when coming to their follow-up visits,” Dr. Wang added.

The analysis found that clinicians who prescribed triple-pill FDC used 23 unique drug treatment regimens per 100 treated patients compared with 54 different regiments with usual care (P < .001). “There was a large simplification in care,” Dr. Wang said of the FDC approach.

Dr. Wang and colleagues called for greater efforts to address therapeutic inertia, particularly with FDC therapies, and suggested potential strategies consisting of patient education, incentives for appropriate treatment adjustments, and feedback mechanisms and reminders for physicians.

“There may also be a need for more dosage options with the FDC triple pill to allow physicians to intensify therapy without fear of overtreatment and adverse drug effects,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2693), Ann Marie Navar, MD, PhD, associate professor of cardiology at Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., noted that initiating treatment with FDC therapy doesn’t preclude a more personalized approach for patients who don’t achieve their BP target. “The real choice now is the choice of initial treatment,” she wrote, adding that future treatment guidelines should consider extending an FDC-first approach to patients with less severe levels of hypertension.

“The study showed there’s room for a both a population-based fixed-drug combination approach and a personalized approach to how we think about hypertension management with fixed-dose therapy,” she said in an interview. “It’s not a one-and-done situation.”

Dr. Wang has no financial relationships to disclose. Study coauthors received funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Navar has no relevant financial relationships to report.

SOURCE: Wang N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739.

A secondary analysis of a major study of polypill therapy for hypertension found that patients who don’t reach blood pressure targets are less likely to have their medications adjusted if they’re on fixed-dose combination therapy.

However, hypertension patients on low-dose, triple-pill combination therapy are more likely to achieve blood pressure control than are those on usual care.

The secondary analysis of Triple Pill vs. Usual Care Management for Patients with Mild-to-Moderate Hypertension (TRIUMPH) was published online in JAMA Cardiology (2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739). The trial randomized 700 patients with hypertension in Sri Lanka to triple-pill fixed-dose combination (FDC) therapy or usual care during February 2016–May 2017, with follow-up ending in October 2017.

A greater proportion of FDC patients reached target BP by the end of the study compared with usual care, 70% vs. 55%. However, the study found that therapeutic inertia – the failure to intensify therapy in nonresponsive patients – was more common in the FDC group at 6- and 12-week follow-up: 87% vs. 64% and 90% vs. 65%, respectively; both differences were significant different at P < .001).

The once-daily FDC pill contained telmisartan 20 mg, amlodipine 2.5 mg; and chlorthalidone 12.5 mg.

“Using a triple low-dose combination blood-pressure pill reduced the need to uptitrate BP therapy as more patients are at target, but doctors were less likely to uptitrate with triple-pill therapy when it was needed,” lead author Nelson Wang, MD, a research fellow at the George Institute for Global Health in suburban Sydney, said in an interview.

“Overall, there were fewer treatment inertia episodes in the triple-pill group than in the usual care group, but this was driven by the fact that fewer triple-pill patients needed uptitration when coming to their follow-up visits,” Dr. Wang added.

The analysis found that clinicians who prescribed triple-pill FDC used 23 unique drug treatment regimens per 100 treated patients compared with 54 different regiments with usual care (P < .001). “There was a large simplification in care,” Dr. Wang said of the FDC approach.

Dr. Wang and colleagues called for greater efforts to address therapeutic inertia, particularly with FDC therapies, and suggested potential strategies consisting of patient education, incentives for appropriate treatment adjustments, and feedback mechanisms and reminders for physicians.

“There may also be a need for more dosage options with the FDC triple pill to allow physicians to intensify therapy without fear of overtreatment and adverse drug effects,” they wrote.

In an accompanying editorial (JAMA Cardiol. 2020 Jul 22. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2693), Ann Marie Navar, MD, PhD, associate professor of cardiology at Duke Clinical Research Institute, Durham, N.C., noted that initiating treatment with FDC therapy doesn’t preclude a more personalized approach for patients who don’t achieve their BP target. “The real choice now is the choice of initial treatment,” she wrote, adding that future treatment guidelines should consider extending an FDC-first approach to patients with less severe levels of hypertension.

“The study showed there’s room for a both a population-based fixed-drug combination approach and a personalized approach to how we think about hypertension management with fixed-dose therapy,” she said in an interview. “It’s not a one-and-done situation.”

Dr. Wang has no financial relationships to disclose. Study coauthors received funding from the Australian National Health and Medical Research Council and the U.K. National Institute for Health Research. Dr. Navar has no relevant financial relationships to report.

SOURCE: Wang N et al. JAMA Cardiol. 2020. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2020.2739.

FROM JAMA CARDIOLOGY

Part 5: Screening for “Opathies” in Diabetes Patients

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

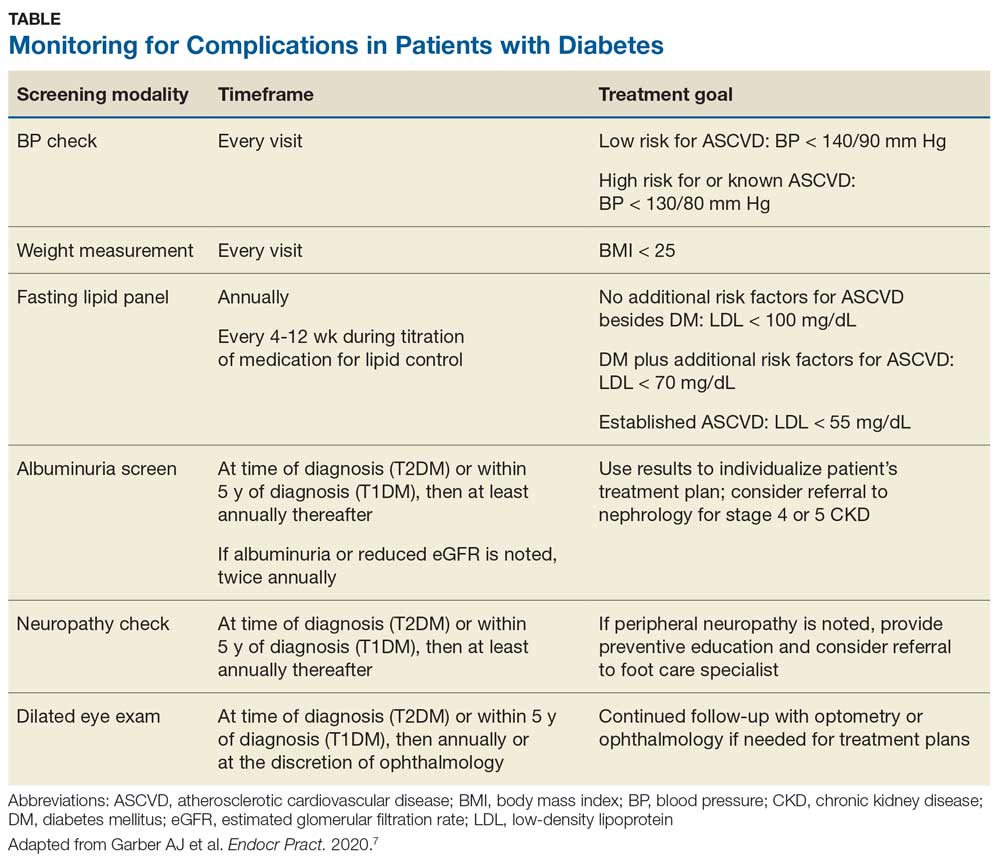

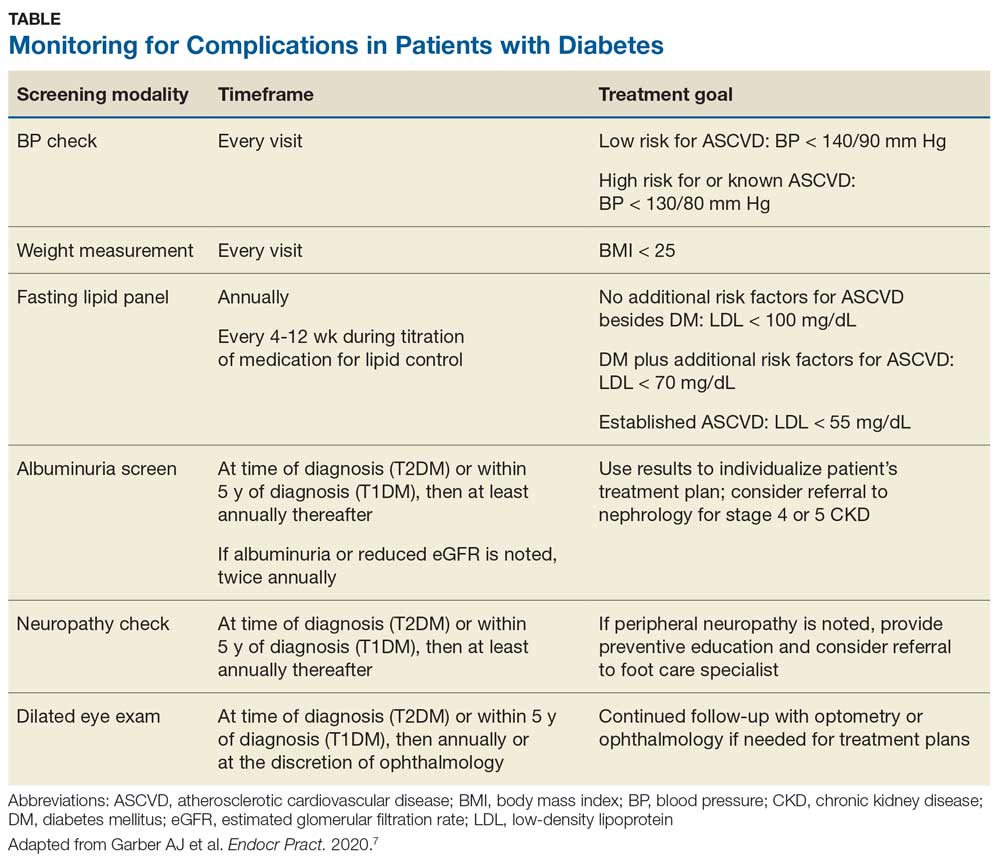

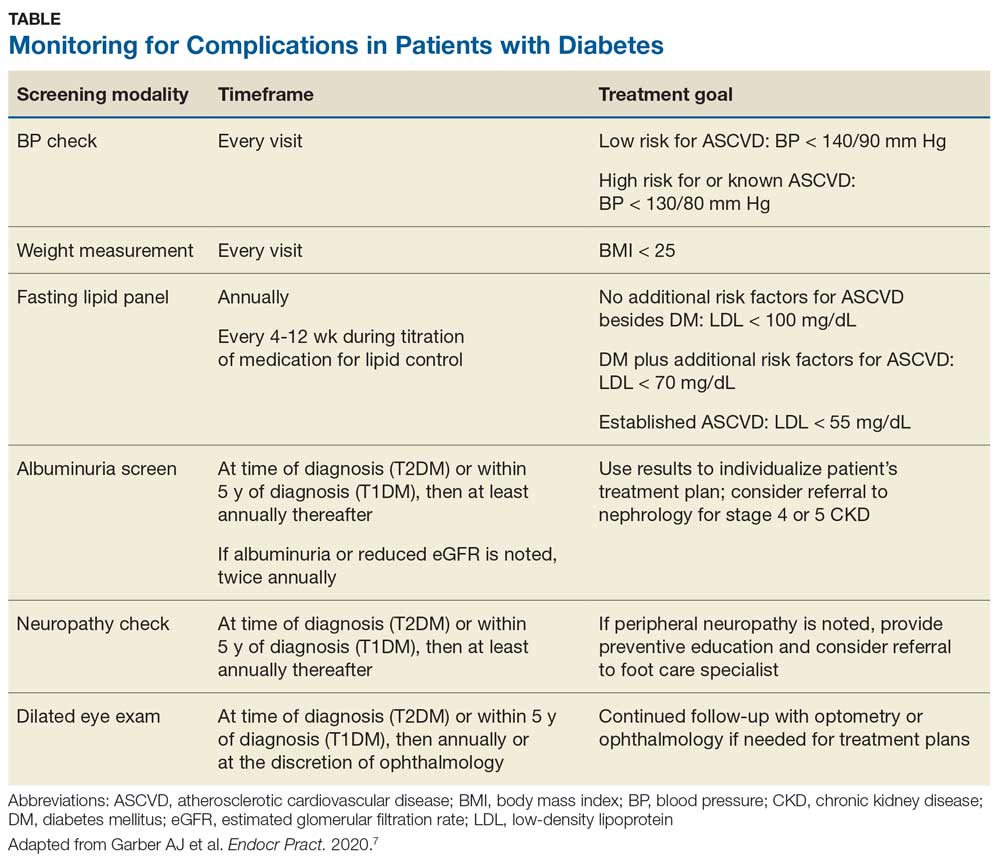

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

Previously, we discussed monitoring for chronic kidney disease in patients with diabetes. In this final part of our series, we’ll discuss screening to prevent impairment to the patient’s mobility and sight.

CASE CONTINUED

Mr. W is appreciative of your efforts to improve his health, but he fears his quality of life with diabetes will suffer. Because his father experienced impaired sight and limited mobility during the final years of his life, Mr. W is concerned he will endure similar complications from his diabetes. What can you do to help safeguard his abilities for sight and mobility?

Detecting peripheral neuropathy

Evaluation of Mr. W’s feet is an appropriate first step in the right direction. Peripheral neuropathy—one of the most common complications in diabetes—occurs in up to 50% of patients with diabetes, and about 50% of peripheral neuropathies may be asymptomatic.40 It is the most significant risk factor for foot ulceration, which in turn is the leading cause of amputation in patients with diabetes.40 Therefore, early identification of peripheral neuropathy is important because it provides an opportunity for patient education on preventive practices and prompts podiatric care.

Screening for peripheral neuropathy should include a detailed history of the risk factors and a thorough physical exam, including pinprick sensation (small sensory fiber function), vibration perception (large sensory fiber function), and 10-g monofilament testing.7,8,40 Clinicians should screen their patients within 5 years of the diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and at the time of diagnosis of type 2 diabetes, subsequently scheduling at least annual screening with a full foot exam.7,8

Further assessment to identify risk factors for diabetic foot wounds should include evaluation for foot deformities and vascular disease.7,8 Findings that indicate vascular disease should prompt ankle-brachial index testing.7,8

Patients are considered at high-risk for peripheral neuropathy if they have sensory impairment, a history of podiatric complications, or foot deformities, or if they actively smoke.8 Such patients should have a thorough foot exam during each visit with their primary care provider, and referral to a foot care specialist would be appropriate.8 High-risk individuals would benefit from close surveillance to prevent complications, and specialized footwear may be helpful.8

How to Screen for Diabetic Retinopathy

Also high on the list of Mr. W’s priorities is maintaining his eyesight. All patients with diabetes require adequate screening for diabetic retinopathy, which is a contributing factor in the progression to blindness.41 Referral to an optometrist or ophthalmologist for a dilated fundoscopic eye exam is recommended for patients within 5 years of a diagnosis of type 1 diabetes and for patients with type 2 diabetes at the time of diagnosis.2,7,8 Prompt referral is need for patients with macular edema, severe nonproliferative diabetic retinopathy, or proliferative diabetic retinopathy. The ADA considers the use of retinal photography in detecting diabetic retinopathy an appropriate component of the fundoscopic exam because it has high sensitivity, specificity, and inter- and intra-examination agreement.8,41,42

Continue to: For patients with...

For patients with poorly controlled diabetes or known diabetic retinopathy, dilated retinal examinations should be scheduled on at least an annual basis.2 For those with well-controlled diabetes and no signs of retinopathy, repeat screening no less frequently than every 2 years may be appropriate.2 This allows prompt diagnosis and treatment of a potentially sight-limiting disease before irreversible damage is caused.

In Conclusion: Empowering Patients with Diabetes

The more Mr. W knows about how to maintain his health, the more control he has over his future with diabetes. Providing patients with knowledge of the risks and empowering them through evidence-based methods is invaluable. DSMES programs help achieve this goal and should be considered at multiple stages in the patient’s disease course, including at the time of initial diagnosis, annually, and when complications or transitions in treatment occur.2,9 Involving patients in their own medical care and management helps them to advocate for their well-being. The patient as a fellow collaborator in treatment can help the clinician design a successful management plan that increases the likelihood of better outcomes for patients such as Mr. W.

To review the important areas of prevention of and screening for complications in patients with diabetes, see the Table. Additional guidance can be found in the ADA and AACE recommendations.2,8

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

1. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Diabetes incidence and prevalence. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/incidence-2017.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

2. Standards of Medical Care in Diabetes—2020 Abridged for Primary Care Providers. American Diabetes Association Clinical Diabetes. 2020;38(1):10-38.

3. Chen Y, Sloan FA, Yashkin AP. Adherence to diabetes guidelines for screening, physical activity and medication and onset of complications and death. J Diabetes Complications. 2015;29(8):1228-1233.

4. Mehta S, Mocarski M, Wisniewski T, et al. Primary care physicians’ utilization of type 2 diabetes screening guidelines and referrals to behavioral interventions: a survey-linked retrospective study. BMJ Open Diabetes Res Care. 2017;5(1):e000406.

5. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. Preventive care practices. Diabetes Report Card 2017. www.cdc.gov/diabetes/library/reports/reportcard/preventive-care.html. Published 2018. Accessed June 18, 2020.

6. Arnold SV, de Lemos JA, Rosenson RS, et al; GOULD Investigators. Use of guideline-recommended risk reduction strategies among patients with diabetes and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2019;140(7):618-620.

7. Garber AJ, Handelsman Y, Grunberger G, et al. Consensus Statement by the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists and American College of Endocrinology on the comprehensive type 2 diabetes management algorithm—2020 executive summary. Endocr Pract Endocr Pract. 2020;26(1):107-139.

8. American Diabetes Association. Comprehensive medical evaluation and assessment of comorbidities: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S37-S47.

9. Beck J, Greenwood DA, Blanton L, et al; 2017 Standards Revision Task Force. 2017 National Standards for diabetes self-management education and support. Diabetes Educ. 2017;43(5): 449-464.

10. Chrvala CA, Sherr D, Lipman RD. Diabetes self-management education for adults with type 2 diabetes mellitus: a systematic review of the effect on glycemic control. Patient Educ Couns. 2016;99(6):926-943.

11. Association of Diabetes Care & Education Specialists. Find a diabetes education program in your area. www.diabeteseducator.org/living-with-diabetes/find-an-education-program. Accessed June 15, 2020.

12. Estruch R, Ros E, Salas-Salvadó J, et al; PREDIMED Study Investigators. Primary prevention of cardiovascular disease with a Mediterranean diet supplemented with extra-virgin olive oil or nuts. NEJM. 2018;378(25):e34.

13. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Tips for better sleep. Sleep and sleep disorders. www.cdc.gov/sleep/about_sleep/sleep_hygiene.html. Reviewed July 15, 2016. Accessed June 18, 2020.

14. Doumit J, Prasad B. Sleep Apnea in Type 2 Diabetes. Diabetes Spectrum. 2016; 29(1): 14-19.

15. Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, et al; LEADER Steering Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators. Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:311-322.

16. Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, et al; CREDENCE Trial Investigators. Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med. 2019;380(24):2295-2306.

17. Trends in Blood pressure control and treatment among type 2 diabetes with comorbid hypertension in the United States: 1988-2004. J Hypertens. 2009;27(9):1908-1916.

18. Emdin CA, Rahimi K, Neal B, et al. Blood pressure lowering in type 2 diabetes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;313(6):603-615.

19. Vouri SM, Shaw RF, Waterbury NV, et al. Prevalence of achievement of A1c, blood pressure, and cholesterol (ABC) goal in veterans with diabetes. J Manag Care Pharm. 2011;17(4):304-312.

20. Kudo N, Yokokawa H, Fukuda H, et al. Achievement of target blood pressure levels among Japanese workers with hypertension and healthy lifestyle characteristics associated with therapeutic failure. Plos One. 2015;10(7):e0133641.

21. Carey RM, Whelton PK; 2017 ACC/AHA Hypertension Guideline Writing Committee. Prevention, detection, evaluation, and management of high blood pressure in adults: synopsis of the 2017 American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Hypertension guideline. Ann Intern Med. 2018;168(5):351-358.

22. Deedwania PC. Blood pressure control in diabetes mellitus. Circulation. 2011;123:2776–2778.

23. Catalá-López F, Saint-Gerons DM, González-Bermejo D, et al. Cardiovascular and renal outcomes of renin-angiotensin system blockade in adult patients with diabetes mellitus: a systematic review with network meta-analyses. PLoS Med. 2016;13(3):e1001971.

24. Furberg CD, Wright JT Jr, Davis BR, et al; ALLHAT Officers and Coordinators for the ALLHAT Collaborative Research Group. Major outcomes in high-risk hypertensive patients randomized to angiotensin-converting enzyme inhibitor or calcium channel blocker vs diuretic: the Antihypertensive and Lipid-Lowering Treatment to Prevent Heart Attack Trial (ALLHAT). JAMA. 2002;288(23):2981-2997.

25. Sleight P. The HOPE Study (Heart Outcomes Prevention Evaluation). J Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone Syst. 2000;1(1):18-20.

26. Tatti P, Pahor M, Byington RP, et al. Outcome results of the Fosinopril Versus Amlodipine Cardiovascular Events Randomized Trial (FACET) in patients with hypertension and NIDDM. Diabetes Care. 1998;21(4):597-603.

27. Schrier RW, Estacio RO, Jeffers B. Appropriate Blood Pressure Control in NIDDM (ABCD) Trial. Diabetologia. 1996;39(12):1646-1654.

28. Hansson L, Zanchetti A, Carruthers SG, et al; HOT Study Group. Effects of intensive blood-pressure lowering and low-dose aspirin in patients with hypertension: principal results of the Hypertension Optimal Treatment (HOT) Randomised Trial. Lancet. 1998;351(9118):1755-1762.

29. Baigent C, Blackwell L, Emberson J, et al; Cholesterol Treatment Trialists’ (CTT) Collaboration. Efficacy and safety of more intensive lowering of LDL cholesterol: a meta-analysis of data from 170,000 participants in 26 randomised trials. Lancet. 2010;376(9753):1670-1681.

30. Fu AZ, Zhang Q, Davies MJ, et al. Underutilization of statins in patients with type 2 diabetes in US clinical practice: a retrospective cohort study. Curr Med Res Opin. 2011;27(5):1035-1040.

31. Cannon CP, Blazing MA, Giugliano RP, et al; IMPROVE-IT Investigators. Ezetimibe added to statin therapy after acute coronary syndromes. N Engl J Med. 2015; 372:2387-2397

32. Sabatine MS, Giugliano RP, Keech AC, et al; the FOURIER Steering Committee and Investigators. Evolocumab and clinical outcomes in patients with cardiovascular disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;376:1713-1722.

33. Schwartz GG, Steg PG, Szarek M, et al; ODYSSEY OUTCOMES Committees and Investigators. Alirocumab and Cardiovascular Outcomes after Acute Coronary Syndrome | NEJM. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:2097-2107.

34. Icosapent ethyl [package insert]. Bridgewater, NJ: Amarin Pharma, Inc.; 2019.

35. Bhatt DL, Steg PG, Miller M, et al; REDUCE-IT Investigators. Cardiovascular risk reduction with icosapent ethyl for hypertriglyceridemia. N Engl J Med. 2019;380:11-22

36. Bolton WK. Renal Physicians Association Clinical practice guideline: appropriate patient preparation for renal replacement therapy: guideline number 3. J Am Soc Nephrol. 2003;14(5):1406-1410.

37. American Diabetes Association. Pharmacologic Approaches to glycemic treatment: standards of medical care in diabetes—2020. Diabetes Care. 2020;43(suppl 1):S98-S110.

38. Qaseem A, Barry MJ, Humphrey LL, Forciea MA; Clinical Guidelines Committee of the American College of Physicians. Oral pharmacologic treatment of type 2 diabetes mellitus: a clinical practice guideline update from the American College of Physicians. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(4):279-290.

39. Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD-MBD Update Work Group. KDIGO 2017 Clinical Practice Guideline Update for the diagnosis, evaluation, prevention, and treatment of chronic kidney disease–mineral and bone disorder (CKD-MBD). Kidney Int Suppl (2011). 2017;7(1):1-59.

40. Pop-Busui R, Boulton AJM, Feldman EL, et al. Diabetic neuropathy: a position statement by the American Diabetes Association. Diabetes Care. 2017;40(1):136-154.

41. Gupta V, Bansal R, Gupta A, Bhansali A. The sensitivity and specificity of nonmydriatic digital stereoscopic retinal imaging in detecting diabetic retinopathy. Indian J Ophthalmol. 2014;62(8):851-856.

42. Pérez MA, Bruce BB, Newman NJ, Biousse V. The use of retinal photography in non-ophthalmic settings and its potential for neurology. The Neurologist. 2012;18(6):350-355.

Delaying denosumab dose boosts risk for vertebral fractures

a new study confirms. Physicians say they are especially concerned about the risk facing patients who are delaying the treatment during the coronavirus pandemic.

The recommended doses of denosumab are at 6-month intervals. Patients who delayed a dose by more than 16 weeks were nearly four times more likely to suffer vertebral fractures, compared with those who received on-time injections, according to the study, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.

“Because patients who used denosumab were at high risk for vertebral fracture, strategies to improve timely administration of denosumab in routine clinical settings are needed,” wrote the study authors, led by Houchen Lyu, MD, PhD, of National Clinical Research Center for Orthopedics, Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation at General Hospital of Chinese PLA in Beijing.

Denosumab, a human monoclonal antibody, is used to reduce bone loss in osteoporosis. The manufacturer of Prolia, a brand of the drug, recommends it be given every 6 months, but the study reports that it’s common for injections to be delayed.

Researchers have linked cessation of denosumab to higher risk of fractures, and Dr. Lyu led a study published earlier this year that linked less-frequent doses to less bone mineral density improvement. “However,” the authors of the new study wrote, “whether delaying subsequent injections beyond the recommended 6-month interval is associated with fractures is unknown.”

For their new study, researchers retrospectively analyzed data from 2,594 patients in the U.K. 45 years or older (mean age, 76; 94% female; 53% with a history of major osteoporotic fracture) who began taking denosumab between 2010 and 2019. They used a design that aimed to emulate a clinical trial, comparing three dosing intervals: “on time” (within 4 weeks of the recommended 6-month interval), “short delay” (within 4-16 weeks) and “long delay” (16 weeks to 6 months).

The study found that the risk of composite fracture over 6 months out of 1,000 was 27.3 for on-time dosing, 32.2 for short-delay dosing, and 42.4 for long-delay dosing. The hazard ratio for long-delay versus on-time was 1.44 (95% confidence interval, 0.96-2.17; P = .093).

Vertebral fractures were less likely, but delays boosted the risk significantly: Over 6 months, it grew from 2.2 in 1,000 (on time) to 3.6 in 1,000 (short delay) and 10.1 in 1,000 (long delay). The HR for long delay versus on time was 3.91 (95% CI, 1.62-9.45; P = .005).

“This study had limited statistical power for composite fracture and several secondary end points ... except for vertebral fracture. Thus, evidence was insufficient to conclude that fracture risk was increased at other anatomical sites.”

In an accompanying editorial, two physicians from the University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, noted that the study is “timely and relevant” since the coronavirus pandemic may disrupt dosage schedules more than usual. While the study has limitations, the “findings are consistent with known denosumab pharmacokinetics and prior studies of fracture incidence after denosumab treatment discontinuation, wrote Kristine E. Ensrud, MD, MPH, who is also of Minneapolis VA Health Care System, and John T. Schousboe, MD, PhD, who is also of HealthPartners Institute.

The editorial authors noted that, in light of the pandemic, “some organizations recommend temporary transition to an oral bisphosphonate in patients receiving denosumab treatment for whom continued treatment is not feasible within 7 to 8 months of their most recent injection.”

In an interview, endocrinologist and osteoporosis specialist Ethel Siris, MD, of Columbia University, New York, said many of her patients aren’t coming in for denosumab injections during the pandemic. “It’s hard enough to get people to show up every 6 months to get their shot when things are going nicely,” she said. “We’re talking older women who may be on a lot of other medications. People forget, and it’s difficult for the office to constantly remind some of them to get their shots at an infusion center.”

The lack of symptoms is another challenge to getting patients to return for doses, she said. “In osteoporosis, the only time something hurts is if you break it.”

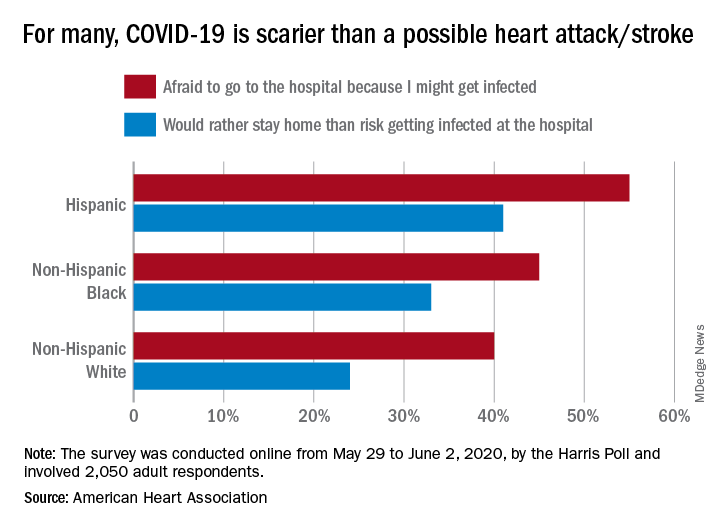

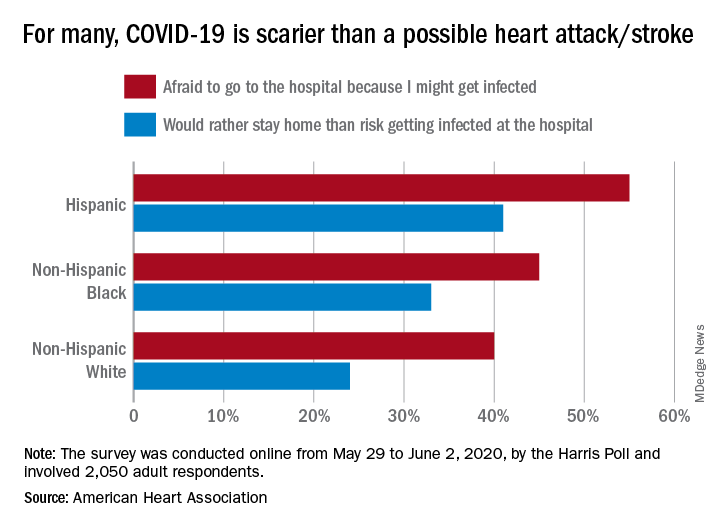

Since the pandemic began, many patients have been avoiding medical offices because of fear of getting the coronavirus.

The new research is helpful because it shows that patients are “more likely to fracture if they delay,” Dr. Siris noted. The endocrinologist added that she has successfully convinced some patients to give themselves subcutaneous injections in the abdomen at home.

Dr. Siris said she has been able to watch patients do these injections on video to check their technique. Her patients have been impressed by “how easy it is and delighted to have accomplished it,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health China’s National Clinical Research Center for Orthopedics, Sports Medicine & Rehabilitation. The study authors, commentary authors, and Dr. Siris report no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Lyu H et al. Ann Intern Med. 2020 Jul 28. doi: 10.7326/M20-0882.

a new study confirms. Physicians say they are especially concerned about the risk facing patients who are delaying the treatment during the coronavirus pandemic.

The recommended doses of denosumab are at 6-month intervals. Patients who delayed a dose by more than 16 weeks were nearly four times more likely to suffer vertebral fractures, compared with those who received on-time injections, according to the study, which was published in Annals of Internal Medicine.