User login

What's your diagnosis?

Hepatic portal venous gas

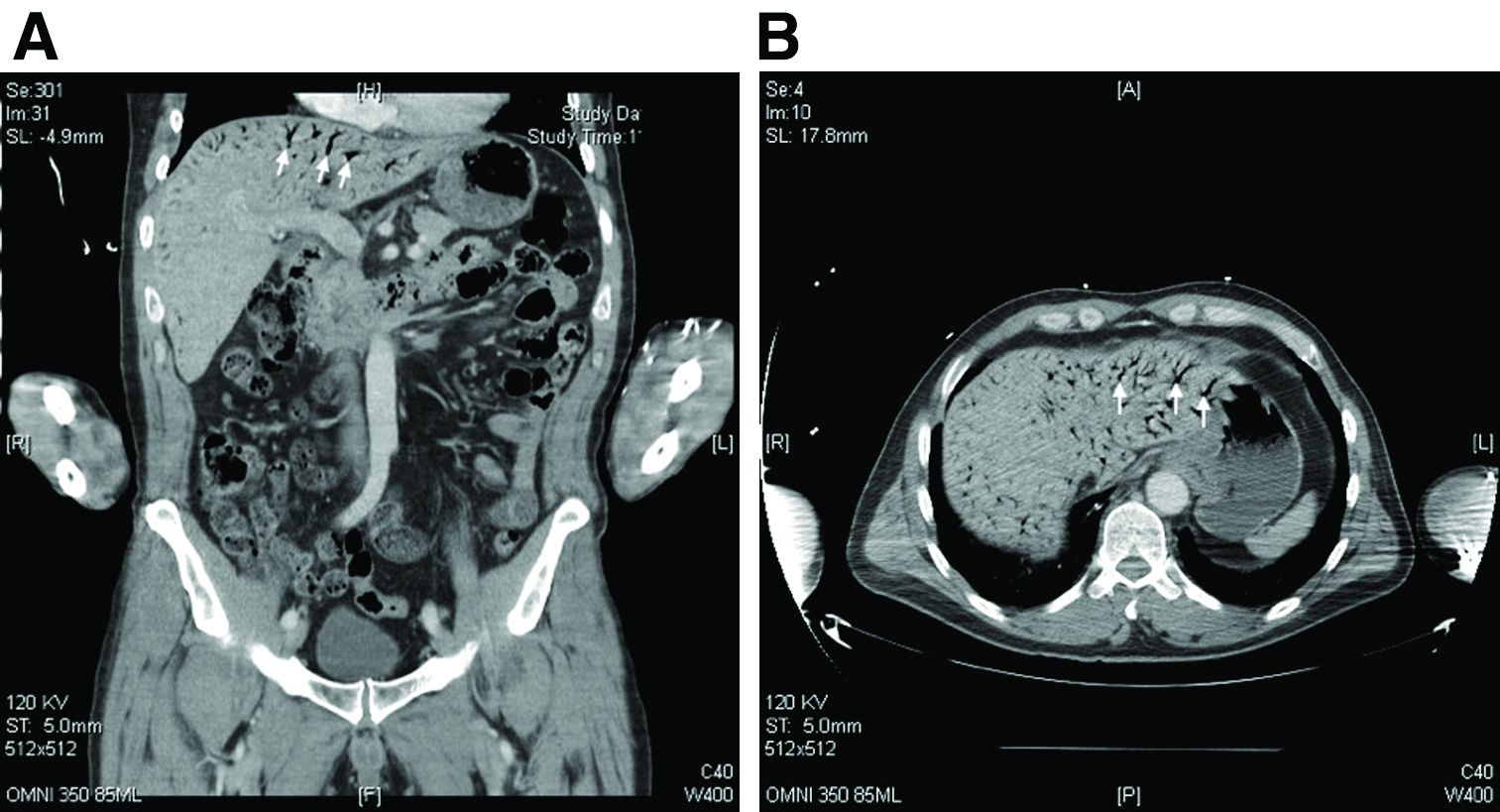

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

Hepatic portal venous gas

The CT scan of the abdomen and pelvis depicts portal venous gas throughout the liver (Figure A, B, white arrows). Hepatic portal venous gas is traditionally regarded as an ominous radiologic sign and appears as a branching area of low attenuation on CT scanning extending to within 2 cm of the liver capsule.1 It is commonly associated with numerous underlying abdominal diseases, ranging from benign processes to potentially lethal etiologies requiring immediate surgical intervention. The mechanism of hepatic portal venous gas can involve mechanical injury to the bowel lumen or gas-producing bacteria in the intestine.2 In the specific case of caustic ingestion of H2O2, the presence of bubbles in the portal vein could result from the oxygen generated by the caustic after passage through damaged gastric mucosa or from generation of oxygen in the blood after absorption of the caustic.3

Despite numerous reports of satisfactory outcomes with conservative management, the discovery of portal venous gas should not be dismissed quickly. Ultimately, management should be tailored to the underlying etiology and may include urgent surgical intervention. When appropriate, conservative management may include intravenous fluids and proton pump inhibitors.2,3 However, in cases involving caustic ingestion and massive gas embolization, providers should maintain a high index of clinical suspicion for neurologic as well as cardiac complications, because these complications may benefit from hyperbaric oxygen therapy.2

In this case, the patient had severe symptoms. Therefore, a decision was made to treat him with intravenous fluids, proton pump inhibitors, and two rounds of hyperbaric oxygen therapy. The patient ultimately had an uneventful recovery.

The quiz authors disclose no conflicts.

References

1. Sebastia C et al. Radiographics. 2000 Sep-Oct;20(5):1213-24.

2. Abboud B et al. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Aug 7;15(29):3585-90.

3. Lewin M et al. Eur Radiol. 2002 Dec;12(Suppl 3):S59-61.

How should this condition be managed?

School-based asthma program improves asthma care coordination for children

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

Asthma care coordination for children can be improved through a school-based asthma program involving the child’s school, their family, and clinicians, according to a recent presentation at the annual meeting of the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology, held virtually this year.

“Partnerships among schools, families, and clinicians can be powerful agents to improve the recognition of childhood asthma symptoms, asthma diagnosis and in particular management,” Sujani Kakumanu, MD, clinical associate professor of allergy and immunology at the University of Wisconsin–Madison, said in her presentation. “Emergency treatment plans and asthma action plans, as well as comprehensive education for all school personnel and school environmental mitigation plans, are crucial to controlling asthma symptoms in schools.”

The school is a unique location where families and clinicians can affect asthma outcomes because of the consistent amount of time a student spends there each day, Dr. Kakumanu explained, but everyone involved in allergy care for a child should be aware of and attempt to reduce environmental exposures and triggers found in schools that can worsen asthma, such as irritants, cleaning solutions, dust mites, pests, air pollution, and indoor air quality.

SAMPRO expansion

In 2016, the AAAAI and National Association of School Nurses provided financial support for the School-based Asthma Management Program (SAMPRO). “The impetus behind this initiative was a recognition that coordination with schools was essential to controlling pediatric asthma care,” Dr. Kakumanu said. Initially focusing on asthma alone, SAMPRO has since expanded to include resources for allergy and anaphylaxis and is known as the School-based Asthma, Allergy & Anaphylaxis Management Program (SA3MPRO).

SA3MPRO’s first tenet is the need for an engaged circle of support that includes families, schools, and clinicians of children with asthma. “Establishing and maintaining a healthy circle of support is a critical component to a school-based asthma partnership. It requires an understanding of how care is delivered in clinics as well as in hospitals and at schools,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

School nurses are uniquely positioned to help address gaps in care for children with asthma during the school day by administering medications and limiting the number of student absences caused by asthma. “In addition, school nurses and school personnel often provide key information to the health system about a student’s health status that can impact their prescriptions and their medical care,” she noted.

Setting an action plan

The second SA3MPRO tenet is the development of an asthma action plan by schools for situations when a child presents with urgent asthma symptoms that require quick action. SA3MPRO’s asthma action plan describes a child’s severity of asthma, known asthma triggers and what medications can be delivered at school, and how clinicians and schools can share HIPAA and FERPA-protected information.

Some programs are allowing school nurses to access electronic medical records to share information, Dr. Kakumanu said. UW Health at the University of Wisconsin developed the project, led by Dr. Kakumanu and Robert F. Lemanske Jr., MD, in 2017 that gave school nurses in the Madison Metropolitan School District access to the EMR. Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, the program was linked to decreased prescriptions of steroids among pediatric clinicians, she said.

“This program allowed the quick and efficient delivery of asthma action plans to schools along with necessary authorizations, prescriptions and a consent to share information electronically. With this information and subsequent authorizations, the school nurses were able to update the school health record, manage symptoms at school as directed by the individualized asthma action plan, and coordinate school resources needed to care for the child asthma symptoms during the school day,” Dr. Kakumanu said.

“This program also addressed a common barrier with school-based partnerships, which was the lack of efficient asynchronous communication, and it did this by including the ability of school nurses and clinicians to direct message each other within a protected EMR,” she added. “In order to continue our support for families, there were also measures to include families with corresponding [EMR] messaging and with communication by phone.”

Barriers in the program at UW Health included needing annual training, sustaining momentum for organizational support and interest, monitoring infrastructure, and maintaining documents. Other challenges were in the management of systems that facilitated messaging and the need to obtain additional electronic consents separately from written consents.

Training vital

The third tenet in SA3MPRO is training, which should incorporate a recognition and treatment of asthma symptoms among school staff, students, and families; proper inhaler technique; how medical care will be delivered at the school and by whom; what emergency asthma symptoms look like; and a plan for getting the child to an emergency medical facility. “Regardless of the program that is chosen, asthma education should address health literacy and multiple multicultural beliefs and be delivered in the language that is appropriate for that school and that student body,” Dr. Kakumanu said. “Teachers, janitors, school administrators, and all levels of school personnel should be educated on how to recognize and treat asthma symptoms, especially if a school nurse is not always available on site.”

Marathon not a sprint

The last tenet in SA3MPRO is improving air quality and decreasing environmental exposure to triggers, which involves “the use of environmental recognition and mitigation plans to minimize the effect of allergens, irritants, and air pollutants within the outside and indoor environment that may affect a child with asthma during the school day.”

While these measures may seem daunting, Dr. Kakumanu said the communities that have successfully implemented a SA3MPRO plan are ones that prioritized updated and accurate data, developed a team-based approach, and secured long-term funding for the program. “Important lessons for all of us in this work is remembering that it’s a marathon and not a sprint, and that effective care coordination requires continual and consistent resources,” she said.

Dr. Kakumanu reported no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM AAAAI 2021

SHM Converge Daily News -- Preview

Click here for the preview issue of the SHM Converge Daily News newsletter.

Click here for the preview issue of the SHM Converge Daily News newsletter.

Click here for the preview issue of the SHM Converge Daily News newsletter.

Death from despair

I’ve taken care of both Bill and his wife for a few years. They’re a sweet couple, each with their own neurological issues. Bill has also battled depression on and off over time. He can be a challenge, and I’ve never envied his psychiatrist.

Bill committed suicide in the final week of April.

Patient deaths are unavoidable in medicine. It’s part of the job. Suicides, though less common, also happen. Sometimes they’re related to a sad diagnosis we’ve made, but more commonly (as in Bill’s case) they result from demons we had no control over.

I had a patient commit suicide about 6 months after I started my practice, and probably average one every 2 years (that I hear about) since then. They’re still the deaths that surprise me the most, make me take pause for a few minutes, even after doing this for 23 years.

Suicide is as old as humanity, and gets worse during difficult societal and economic times. It disproportionately affects doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and police officers, and leaves devastated families and friends in its wake.

Death because of the progression of time and disease is never easy, but perhaps more psychologically acceptable to those left behind. Death because of a tragic accident at any age is more difficult.

But when the person involved makes a conscious decision to end his or her own life, the effects on those left behind are terrible. Wondering why, questioning if they could have done something different, and, as with any loss, grieving.

In a world where major advances have been made in many areas of medicine, including mental health, death from despair shows no sign of abating.

Maybe it’s part of the price of sentience and reason. Or civilization. I doubt it will ever stop being a public health issue, no matter how many other diseases we cure.

But, as I write a letter to Bill’s wife, that’s little consolation for those they’ve left behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve taken care of both Bill and his wife for a few years. They’re a sweet couple, each with their own neurological issues. Bill has also battled depression on and off over time. He can be a challenge, and I’ve never envied his psychiatrist.

Bill committed suicide in the final week of April.

Patient deaths are unavoidable in medicine. It’s part of the job. Suicides, though less common, also happen. Sometimes they’re related to a sad diagnosis we’ve made, but more commonly (as in Bill’s case) they result from demons we had no control over.

I had a patient commit suicide about 6 months after I started my practice, and probably average one every 2 years (that I hear about) since then. They’re still the deaths that surprise me the most, make me take pause for a few minutes, even after doing this for 23 years.

Suicide is as old as humanity, and gets worse during difficult societal and economic times. It disproportionately affects doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and police officers, and leaves devastated families and friends in its wake.

Death because of the progression of time and disease is never easy, but perhaps more psychologically acceptable to those left behind. Death because of a tragic accident at any age is more difficult.

But when the person involved makes a conscious decision to end his or her own life, the effects on those left behind are terrible. Wondering why, questioning if they could have done something different, and, as with any loss, grieving.

In a world where major advances have been made in many areas of medicine, including mental health, death from despair shows no sign of abating.

Maybe it’s part of the price of sentience and reason. Or civilization. I doubt it will ever stop being a public health issue, no matter how many other diseases we cure.

But, as I write a letter to Bill’s wife, that’s little consolation for those they’ve left behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

I’ve taken care of both Bill and his wife for a few years. They’re a sweet couple, each with their own neurological issues. Bill has also battled depression on and off over time. He can be a challenge, and I’ve never envied his psychiatrist.

Bill committed suicide in the final week of April.

Patient deaths are unavoidable in medicine. It’s part of the job. Suicides, though less common, also happen. Sometimes they’re related to a sad diagnosis we’ve made, but more commonly (as in Bill’s case) they result from demons we had no control over.

I had a patient commit suicide about 6 months after I started my practice, and probably average one every 2 years (that I hear about) since then. They’re still the deaths that surprise me the most, make me take pause for a few minutes, even after doing this for 23 years.

Suicide is as old as humanity, and gets worse during difficult societal and economic times. It disproportionately affects doctors, dentists, veterinarians, and police officers, and leaves devastated families and friends in its wake.

Death because of the progression of time and disease is never easy, but perhaps more psychologically acceptable to those left behind. Death because of a tragic accident at any age is more difficult.

But when the person involved makes a conscious decision to end his or her own life, the effects on those left behind are terrible. Wondering why, questioning if they could have done something different, and, as with any loss, grieving.

In a world where major advances have been made in many areas of medicine, including mental health, death from despair shows no sign of abating.

Maybe it’s part of the price of sentience and reason. Or civilization. I doubt it will ever stop being a public health issue, no matter how many other diseases we cure.

But, as I write a letter to Bill’s wife, that’s little consolation for those they’ve left behind.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz.

Patients with agoraphobia are showing strength, resilience during the pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a wave of general and mental health-related problems, such as stress, addiction, weight gain, depression, and social isolation. Those problems have been exacerbated in patients with mental illness who are already struggling to cope with personal problems.

One might expect those with agoraphobia to be adversely affected by the pandemic and experience increased feelings of anxiety. It appears that people with agoraphobia might especially feel uncertain of other people’s actions during this time. Some might perceive being alone and cut off from help, and those feelings might make them more susceptible to panic attacks.

In my (R.W.C.) clinical experience, however, my patients with agoraphobia are actually functioning better than usual throughout this challenging course.

Personalizing treatment

Agoraphobia is a type of anxiety disorder that often develops after a panic attack and involves an intense fear of a place or situation. In my 40 years of clinical experience, I have treated about 300 patients with agoraphobia, and all of them exhibit the following three symptoms: depression (from losses in life), dependency (dependent on other people to help with activities of daily living), and panic attacks (an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that may cause a person to avoid crowded areas or other public spaces outside of the home).

To manage these clients, I individualize treatment and use different strategies for different patients to help them cope with their agoraphobia. I normally treat my agoraphobic patients with a combination of medication and therapy. I most often use a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and my SSRI drug of choice is usually paroxetine (Paxil). Or, instead of an SSRI, I sometimes prescribe a tricyclic antidepressant, often Tofranil (imipramine). As an adjunct, I might prescribe a benzodiazepine, Xanax (alprazolam), p.r.n. My prescription decision is based on a patient’s side effect profile, medical history, and close blood relatives’ responses to those medications.

The therapy I use is behavior modification with systematic desensitization and flooding. Desensitization is a coping technique that helps the patient overcome triggers associated with the panic attacks and anxiety. In normal times, I use both in vitro (imaginary) and in vivo (real situation) desensitization. However, during the pandemic, I can use only in vitro desensitization, since I am treating patients through phone calls and telemedicine rather than in-person visits.

I also teach my patients with agoraphobia relaxation techniques to work through their fears and anxieties, and thus to reduce feelings of stress and anxiety. The patients can practice these learned techniques on their own in an effort to reduce panic and avoidance behaviors, and create a relaxation response.

Treating the key symptoms

As stated earlier, all of my agoraphobic patients exhibit the following three symptoms: depression, dependency, and panic attacks.

- Depression – My agoraphobia patients are less depressed during the pandemic and are not feeling intense losses as they did prepandemic.

- Dependency – During the pandemic, everyone has been interdependent upon other people in their households. Therefore, the patients’ support systems are more readily available, and the patients can help others as much as others help them in their own households or “havens of safety.”

- Panic attacks – As depression has declined, panic attacks have also declined, since they are interrelated.

Understanding why functioning might be better

I attribute the improved functioning I am seeing to five factors:

1. Some people with agoraphobia may find that physical distancing provides relief, because it discourages situations that may trigger fear.

2. Staying in their homes can make people with agoraphobia feel like part of mainstream America, rather than outside the norm. Also, they become egosyntonic, and sense both acceptance and comfort in their homes.

3. Isolating, staying home, and avoidance behavior is now applauded and has become the norm for the entire population. Thus, people with agoraphobia might feel heightened self-esteem.

4. Since many people have been staying in for the most part, people with agoraphobia do not feel they are missing out by staying in. As a result, they are experiencing less depression.

5. Now, I treat my patients through the use of telemedicine or by phone, and thus, patients are more relaxed and calm because they do not have to leave their homes and travel to my office. Thus, patients can avoid this dreaded anxiety trigger.

It might have been logical to assume that patients living with agoraphobia would be negatively affected by the pandemic, and experience increased feelings of anxiety and/or panic attacks – since the pandemic forced those with the illness to face fearful situations from which they cannot escape.

Fortunately, my agoraphobia patients have fared very well. They have remained on their prescribed medications and have adapted well to phone and telemedicine therapy. In fact, the adjustment of my patients with agoraphobia to the stringent mitigation measures surpassed the adjustment of my other patients. These patients with agoraphobia have proved to be a strong and resilient group in the face of extreme stress.

Dr. Cohen, who is married to Nancy S. Cohen, is board-certified in psychiatry and has had a private practice in Philadelphia for more than 35 years. His areas of specialty include agoraphobia, sports psychiatry, depression, and substance abuse. In addition, Dr. Cohen is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Cohen holds an MBA from Temple University in Philadelphia with a focus on health care administration. Previously, Ms. Cohen was an associate administrator at Hahnemann University Hospital and an executive at the Health Services Council, both in Philadelphia. She currently writes biographical summaries of notable 18th- and 19th-century women. Ms. Cohen has no disclosures.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a wave of general and mental health-related problems, such as stress, addiction, weight gain, depression, and social isolation. Those problems have been exacerbated in patients with mental illness who are already struggling to cope with personal problems.

One might expect those with agoraphobia to be adversely affected by the pandemic and experience increased feelings of anxiety. It appears that people with agoraphobia might especially feel uncertain of other people’s actions during this time. Some might perceive being alone and cut off from help, and those feelings might make them more susceptible to panic attacks.

In my (R.W.C.) clinical experience, however, my patients with agoraphobia are actually functioning better than usual throughout this challenging course.

Personalizing treatment

Agoraphobia is a type of anxiety disorder that often develops after a panic attack and involves an intense fear of a place or situation. In my 40 years of clinical experience, I have treated about 300 patients with agoraphobia, and all of them exhibit the following three symptoms: depression (from losses in life), dependency (dependent on other people to help with activities of daily living), and panic attacks (an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that may cause a person to avoid crowded areas or other public spaces outside of the home).

To manage these clients, I individualize treatment and use different strategies for different patients to help them cope with their agoraphobia. I normally treat my agoraphobic patients with a combination of medication and therapy. I most often use a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and my SSRI drug of choice is usually paroxetine (Paxil). Or, instead of an SSRI, I sometimes prescribe a tricyclic antidepressant, often Tofranil (imipramine). As an adjunct, I might prescribe a benzodiazepine, Xanax (alprazolam), p.r.n. My prescription decision is based on a patient’s side effect profile, medical history, and close blood relatives’ responses to those medications.

The therapy I use is behavior modification with systematic desensitization and flooding. Desensitization is a coping technique that helps the patient overcome triggers associated with the panic attacks and anxiety. In normal times, I use both in vitro (imaginary) and in vivo (real situation) desensitization. However, during the pandemic, I can use only in vitro desensitization, since I am treating patients through phone calls and telemedicine rather than in-person visits.

I also teach my patients with agoraphobia relaxation techniques to work through their fears and anxieties, and thus to reduce feelings of stress and anxiety. The patients can practice these learned techniques on their own in an effort to reduce panic and avoidance behaviors, and create a relaxation response.

Treating the key symptoms

As stated earlier, all of my agoraphobic patients exhibit the following three symptoms: depression, dependency, and panic attacks.

- Depression – My agoraphobia patients are less depressed during the pandemic and are not feeling intense losses as they did prepandemic.

- Dependency – During the pandemic, everyone has been interdependent upon other people in their households. Therefore, the patients’ support systems are more readily available, and the patients can help others as much as others help them in their own households or “havens of safety.”

- Panic attacks – As depression has declined, panic attacks have also declined, since they are interrelated.

Understanding why functioning might be better

I attribute the improved functioning I am seeing to five factors:

1. Some people with agoraphobia may find that physical distancing provides relief, because it discourages situations that may trigger fear.

2. Staying in their homes can make people with agoraphobia feel like part of mainstream America, rather than outside the norm. Also, they become egosyntonic, and sense both acceptance and comfort in their homes.

3. Isolating, staying home, and avoidance behavior is now applauded and has become the norm for the entire population. Thus, people with agoraphobia might feel heightened self-esteem.

4. Since many people have been staying in for the most part, people with agoraphobia do not feel they are missing out by staying in. As a result, they are experiencing less depression.

5. Now, I treat my patients through the use of telemedicine or by phone, and thus, patients are more relaxed and calm because they do not have to leave their homes and travel to my office. Thus, patients can avoid this dreaded anxiety trigger.

It might have been logical to assume that patients living with agoraphobia would be negatively affected by the pandemic, and experience increased feelings of anxiety and/or panic attacks – since the pandemic forced those with the illness to face fearful situations from which they cannot escape.

Fortunately, my agoraphobia patients have fared very well. They have remained on their prescribed medications and have adapted well to phone and telemedicine therapy. In fact, the adjustment of my patients with agoraphobia to the stringent mitigation measures surpassed the adjustment of my other patients. These patients with agoraphobia have proved to be a strong and resilient group in the face of extreme stress.

Dr. Cohen, who is married to Nancy S. Cohen, is board-certified in psychiatry and has had a private practice in Philadelphia for more than 35 years. His areas of specialty include agoraphobia, sports psychiatry, depression, and substance abuse. In addition, Dr. Cohen is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Cohen holds an MBA from Temple University in Philadelphia with a focus on health care administration. Previously, Ms. Cohen was an associate administrator at Hahnemann University Hospital and an executive at the Health Services Council, both in Philadelphia. She currently writes biographical summaries of notable 18th- and 19th-century women. Ms. Cohen has no disclosures.

The COVID-19 pandemic has exposed a wave of general and mental health-related problems, such as stress, addiction, weight gain, depression, and social isolation. Those problems have been exacerbated in patients with mental illness who are already struggling to cope with personal problems.

One might expect those with agoraphobia to be adversely affected by the pandemic and experience increased feelings of anxiety. It appears that people with agoraphobia might especially feel uncertain of other people’s actions during this time. Some might perceive being alone and cut off from help, and those feelings might make them more susceptible to panic attacks.

In my (R.W.C.) clinical experience, however, my patients with agoraphobia are actually functioning better than usual throughout this challenging course.

Personalizing treatment

Agoraphobia is a type of anxiety disorder that often develops after a panic attack and involves an intense fear of a place or situation. In my 40 years of clinical experience, I have treated about 300 patients with agoraphobia, and all of them exhibit the following three symptoms: depression (from losses in life), dependency (dependent on other people to help with activities of daily living), and panic attacks (an abrupt surge of intense fear or intense discomfort that may cause a person to avoid crowded areas or other public spaces outside of the home).

To manage these clients, I individualize treatment and use different strategies for different patients to help them cope with their agoraphobia. I normally treat my agoraphobic patients with a combination of medication and therapy. I most often use a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), and my SSRI drug of choice is usually paroxetine (Paxil). Or, instead of an SSRI, I sometimes prescribe a tricyclic antidepressant, often Tofranil (imipramine). As an adjunct, I might prescribe a benzodiazepine, Xanax (alprazolam), p.r.n. My prescription decision is based on a patient’s side effect profile, medical history, and close blood relatives’ responses to those medications.

The therapy I use is behavior modification with systematic desensitization and flooding. Desensitization is a coping technique that helps the patient overcome triggers associated with the panic attacks and anxiety. In normal times, I use both in vitro (imaginary) and in vivo (real situation) desensitization. However, during the pandemic, I can use only in vitro desensitization, since I am treating patients through phone calls and telemedicine rather than in-person visits.

I also teach my patients with agoraphobia relaxation techniques to work through their fears and anxieties, and thus to reduce feelings of stress and anxiety. The patients can practice these learned techniques on their own in an effort to reduce panic and avoidance behaviors, and create a relaxation response.

Treating the key symptoms

As stated earlier, all of my agoraphobic patients exhibit the following three symptoms: depression, dependency, and panic attacks.

- Depression – My agoraphobia patients are less depressed during the pandemic and are not feeling intense losses as they did prepandemic.

- Dependency – During the pandemic, everyone has been interdependent upon other people in their households. Therefore, the patients’ support systems are more readily available, and the patients can help others as much as others help them in their own households or “havens of safety.”

- Panic attacks – As depression has declined, panic attacks have also declined, since they are interrelated.

Understanding why functioning might be better

I attribute the improved functioning I am seeing to five factors:

1. Some people with agoraphobia may find that physical distancing provides relief, because it discourages situations that may trigger fear.

2. Staying in their homes can make people with agoraphobia feel like part of mainstream America, rather than outside the norm. Also, they become egosyntonic, and sense both acceptance and comfort in their homes.

3. Isolating, staying home, and avoidance behavior is now applauded and has become the norm for the entire population. Thus, people with agoraphobia might feel heightened self-esteem.

4. Since many people have been staying in for the most part, people with agoraphobia do not feel they are missing out by staying in. As a result, they are experiencing less depression.

5. Now, I treat my patients through the use of telemedicine or by phone, and thus, patients are more relaxed and calm because they do not have to leave their homes and travel to my office. Thus, patients can avoid this dreaded anxiety trigger.

It might have been logical to assume that patients living with agoraphobia would be negatively affected by the pandemic, and experience increased feelings of anxiety and/or panic attacks – since the pandemic forced those with the illness to face fearful situations from which they cannot escape.

Fortunately, my agoraphobia patients have fared very well. They have remained on their prescribed medications and have adapted well to phone and telemedicine therapy. In fact, the adjustment of my patients with agoraphobia to the stringent mitigation measures surpassed the adjustment of my other patients. These patients with agoraphobia have proved to be a strong and resilient group in the face of extreme stress.

Dr. Cohen, who is married to Nancy S. Cohen, is board-certified in psychiatry and has had a private practice in Philadelphia for more than 35 years. His areas of specialty include agoraphobia, sports psychiatry, depression, and substance abuse. In addition, Dr. Cohen is a former professor of psychiatry, family medicine, and otolaryngology at Thomas Jefferson University in Philadelphia. He has no conflicts of interest. Ms. Cohen holds an MBA from Temple University in Philadelphia with a focus on health care administration. Previously, Ms. Cohen was an associate administrator at Hahnemann University Hospital and an executive at the Health Services Council, both in Philadelphia. She currently writes biographical summaries of notable 18th- and 19th-century women. Ms. Cohen has no disclosures.

Are adolescents canaries in the coal mine?

Increasing youth suicides may be a warning about society’s psychosocial health.

Before COVID-19 pandemic, suicide rates were already increasing among adolescents.1 Loneliness, because of social isolation and loss of in-person community contacts, was recognized as one factor perhaps contributing to increasing adolescent suicide.2 Now, with the physical distancing measures vital to curbing the spread, the loneliness epidemic that preceded COVID-19 has only worsened, and suicidal thoughts in adolescents remain on the rise.3

Given the crucial role of interpersonal interactions and community in healthy adolescent development, these troubling trends provide insight not only into the psychosocial health of our teenagers but also into the psychosocial health of our society as a whole.

Over the past 8 months, our psychiatric crisis stabilization unit has experienced a surge in admissions for adolescents with suicidal ideation, often with accompanying attempts. Even more concerning, a significant percentage of these patients do not have additional symptoms of depression or premorbid risk factors for suicide. In many cases, there are no warning signs to alert parents of their adolescent’s imminent suicidal behavior.

Prior to COVID-19, most of our patients with suicidal ideations arrived withdrawn, irritable, and isolative. Interactions with these patients evoked poignant feelings of empathy and sadness, and these patients endorsed multiple additional symptoms consistent with criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

More recently, since COVID-19, we have observed patients who, mere hours earlier, were in an ED receiving medical interventions for a suicide attempt, now present on our unit smiling, laughing, and interacting contentedly with their peers. Upon integration into our milieu, they often report complete resolution of their suicidal thoughts. Interactions with these patients do not conjure feelings of sadness or despair. In fact, we often struggle with diagnostic specificity, because many of these patients do not meet criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

As observed in real time on our unit, meaningful interpersonal interactions are especially crucial to our adolescents’ psychosocial and emotional well-being. As their independence grows, their holding environment expands to incorporate the community. Nonparent family members, teachers, mentors, coaches, peers, parents, and most importantly, same-aged peers play a vital role in creating the environment necessary for healthy adolescent development.

The larger community is essential for adolescents to develop the skills and confidence to move into adulthood. When adolescents are lonely, with less contact with the community outside of their family, they lose the milieu in which they develop. Their fundamental psychological need of belonging becomes compromised; they fail to experience fidelity or a sense of self; and sometimes they no longer have the desire to live.

So what might the increasing suicide rate in adolescents indicate about the status of the psychosocial health of our society as a whole? Based on the vital necessity of community to support their development, Like the canary in the coal mines, this increase in suicidal ideations in our adolescent population may be a warning that our current lack of psychosocial supports have become toxic. If we cannot restore our relatedness and reconstruct our sense of community, societal psychosocial health may continue to decline.

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. 2019 Oct (352). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db352-h.pdf

2. J Soc Pers Relationships. 2019 Mar 19. doi: 10.1177/0265407519836170.

3. Medscape.com. 2020 Sep 25. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/938065.

Dr. Loper is the team leader for inpatient psychiatric services at Prisma Health–Midlands in Columbia, S.C. He is an assistant professor in the department of neuropsychiatry and behavioral science at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Kaminstein is an adjunct assistant professor at the graduate school of education and affiliated faculty in the organizational dynamics program, School of Arts and Sciences, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He is a social psychologist who has been studying groups and organizations for more than 40 years. He has no conflicts of interest.

Increasing youth suicides may be a warning about society’s psychosocial health.

Increasing youth suicides may be a warning about society’s psychosocial health.

Before COVID-19 pandemic, suicide rates were already increasing among adolescents.1 Loneliness, because of social isolation and loss of in-person community contacts, was recognized as one factor perhaps contributing to increasing adolescent suicide.2 Now, with the physical distancing measures vital to curbing the spread, the loneliness epidemic that preceded COVID-19 has only worsened, and suicidal thoughts in adolescents remain on the rise.3

Given the crucial role of interpersonal interactions and community in healthy adolescent development, these troubling trends provide insight not only into the psychosocial health of our teenagers but also into the psychosocial health of our society as a whole.

Over the past 8 months, our psychiatric crisis stabilization unit has experienced a surge in admissions for adolescents with suicidal ideation, often with accompanying attempts. Even more concerning, a significant percentage of these patients do not have additional symptoms of depression or premorbid risk factors for suicide. In many cases, there are no warning signs to alert parents of their adolescent’s imminent suicidal behavior.

Prior to COVID-19, most of our patients with suicidal ideations arrived withdrawn, irritable, and isolative. Interactions with these patients evoked poignant feelings of empathy and sadness, and these patients endorsed multiple additional symptoms consistent with criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

More recently, since COVID-19, we have observed patients who, mere hours earlier, were in an ED receiving medical interventions for a suicide attempt, now present on our unit smiling, laughing, and interacting contentedly with their peers. Upon integration into our milieu, they often report complete resolution of their suicidal thoughts. Interactions with these patients do not conjure feelings of sadness or despair. In fact, we often struggle with diagnostic specificity, because many of these patients do not meet criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

As observed in real time on our unit, meaningful interpersonal interactions are especially crucial to our adolescents’ psychosocial and emotional well-being. As their independence grows, their holding environment expands to incorporate the community. Nonparent family members, teachers, mentors, coaches, peers, parents, and most importantly, same-aged peers play a vital role in creating the environment necessary for healthy adolescent development.

The larger community is essential for adolescents to develop the skills and confidence to move into adulthood. When adolescents are lonely, with less contact with the community outside of their family, they lose the milieu in which they develop. Their fundamental psychological need of belonging becomes compromised; they fail to experience fidelity or a sense of self; and sometimes they no longer have the desire to live.

So what might the increasing suicide rate in adolescents indicate about the status of the psychosocial health of our society as a whole? Based on the vital necessity of community to support their development, Like the canary in the coal mines, this increase in suicidal ideations in our adolescent population may be a warning that our current lack of psychosocial supports have become toxic. If we cannot restore our relatedness and reconstruct our sense of community, societal psychosocial health may continue to decline.

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. 2019 Oct (352). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db352-h.pdf

2. J Soc Pers Relationships. 2019 Mar 19. doi: 10.1177/0265407519836170.

3. Medscape.com. 2020 Sep 25. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/938065.

Dr. Loper is the team leader for inpatient psychiatric services at Prisma Health–Midlands in Columbia, S.C. He is an assistant professor in the department of neuropsychiatry and behavioral science at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Kaminstein is an adjunct assistant professor at the graduate school of education and affiliated faculty in the organizational dynamics program, School of Arts and Sciences, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He is a social psychologist who has been studying groups and organizations for more than 40 years. He has no conflicts of interest.

Before COVID-19 pandemic, suicide rates were already increasing among adolescents.1 Loneliness, because of social isolation and loss of in-person community contacts, was recognized as one factor perhaps contributing to increasing adolescent suicide.2 Now, with the physical distancing measures vital to curbing the spread, the loneliness epidemic that preceded COVID-19 has only worsened, and suicidal thoughts in adolescents remain on the rise.3

Given the crucial role of interpersonal interactions and community in healthy adolescent development, these troubling trends provide insight not only into the psychosocial health of our teenagers but also into the psychosocial health of our society as a whole.

Over the past 8 months, our psychiatric crisis stabilization unit has experienced a surge in admissions for adolescents with suicidal ideation, often with accompanying attempts. Even more concerning, a significant percentage of these patients do not have additional symptoms of depression or premorbid risk factors for suicide. In many cases, there are no warning signs to alert parents of their adolescent’s imminent suicidal behavior.

Prior to COVID-19, most of our patients with suicidal ideations arrived withdrawn, irritable, and isolative. Interactions with these patients evoked poignant feelings of empathy and sadness, and these patients endorsed multiple additional symptoms consistent with criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

More recently, since COVID-19, we have observed patients who, mere hours earlier, were in an ED receiving medical interventions for a suicide attempt, now present on our unit smiling, laughing, and interacting contentedly with their peers. Upon integration into our milieu, they often report complete resolution of their suicidal thoughts. Interactions with these patients do not conjure feelings of sadness or despair. In fact, we often struggle with diagnostic specificity, because many of these patients do not meet criteria for a specified depressive disorder.

As observed in real time on our unit, meaningful interpersonal interactions are especially crucial to our adolescents’ psychosocial and emotional well-being. As their independence grows, their holding environment expands to incorporate the community. Nonparent family members, teachers, mentors, coaches, peers, parents, and most importantly, same-aged peers play a vital role in creating the environment necessary for healthy adolescent development.

The larger community is essential for adolescents to develop the skills and confidence to move into adulthood. When adolescents are lonely, with less contact with the community outside of their family, they lose the milieu in which they develop. Their fundamental psychological need of belonging becomes compromised; they fail to experience fidelity or a sense of self; and sometimes they no longer have the desire to live.

So what might the increasing suicide rate in adolescents indicate about the status of the psychosocial health of our society as a whole? Based on the vital necessity of community to support their development, Like the canary in the coal mines, this increase in suicidal ideations in our adolescent population may be a warning that our current lack of psychosocial supports have become toxic. If we cannot restore our relatedness and reconstruct our sense of community, societal psychosocial health may continue to decline.

References

1. National Center for Health Statistics Data Brief. 2019 Oct (352). https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/databriefs/db352-h.pdf

2. J Soc Pers Relationships. 2019 Mar 19. doi: 10.1177/0265407519836170.

3. Medscape.com. 2020 Sep 25. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/938065.

Dr. Loper is the team leader for inpatient psychiatric services at Prisma Health–Midlands in Columbia, S.C. He is an assistant professor in the department of neuropsychiatry and behavioral science at the University of South Carolina, Columbia. He has no conflicts of interest. Dr. Kaminstein is an adjunct assistant professor at the graduate school of education and affiliated faculty in the organizational dynamics program, School of Arts and Sciences, at the University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia. He is a social psychologist who has been studying groups and organizations for more than 40 years. He has no conflicts of interest.

Weight cycling linked to cartilage degeneration in knee OA

Repetitive weight loss and gain in overweight or obese patients with knee osteoarthritis is associated with significantly greater cartilage and bone marrow edema degeneration than stable weight or steady weight loss, research suggests.

A presentation at the OARSI 2021 World Congress outlined the results of a study using Osteoarthritis Initiative data from 2,271 individuals with knee osteoarthritis and a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or above, which examined the effects of “weight cycling” on OA outcomes.

Gabby Joseph, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, told the conference – which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International – that previous studies had shown weight loss improves OA symptoms and slow progression, and weight gain increases OA risk. However no studies had yet examined the effects of weight cycling.

The study compared 4 years of MRI data for those who showed less than 3% loss or gain in weight over that time – the control group – versus those who lost more than 5% over that time and those who gained more than 5%. Among these were 249 individuals in the top 10% of annual weight change over that period, who were designated as weight cyclers. They tended to be younger, female, and with slightly higher average BMI than noncyclers.

Weight cyclers had significantly greater progression of cartilage degeneration and bone marrow edema degeneration – as measured by whole-organ magnetic resonance score – than did noncyclers, regardless of their overall weight gain or loss by the end of the study period.

However, the study did not see any significant differences in meniscus progression between cyclers and noncyclers, and cartilage thickness decreased in all groups over the 4 years with no significant effects associated with weight gain, loss, or cycling. Dr. Joseph commented that future studies could use voxel-based relaxometry to more closely study localized cartilage abnormalities.

Researchers also examined the effect of weight cycling on changes to walking speed, and found weight cyclers had significantly lower walking speeds by the end of the 4 years, regardless of overall weight change.

“What we’ve seen is that fluctuations are not beneficial for your joints,” Dr. Joseph told the conference. “When we advise patients that they want to lose weight, we want to do this in a very steady fashion; we don’t want yo-yo dieting.” She gave the example of one patient who started the study with a BMI of 36, went up to 40 then went down to 32.

Commenting on the study, Lisa Carlesso, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said it addresses an important issue because weight cycling is common as people struggle to maintain weight loss.

While it is difficult to speculate on the physiological mechanisms that might explain the effect, Dr. Carlesso noted that there were significantly more women than men among the weight cyclers.

“We know, for example, that obese women with knee OA have significantly higher levels of the adipokine leptin, compared to men, and leptin is involved in cartilage degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said. “Similarly, we don’t have any information about joint alignment or measures of joint load, two things that could factor into the structural changes found.”

She suggested both these possibilities could be explored in future studies of weight cycling and its effects.

“It has opened up new lines of inquiry to be examined to mechanistically explain the relationship between cycling and worse cartilage and bone marrow degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Repetitive weight loss and gain in overweight or obese patients with knee osteoarthritis is associated with significantly greater cartilage and bone marrow edema degeneration than stable weight or steady weight loss, research suggests.

A presentation at the OARSI 2021 World Congress outlined the results of a study using Osteoarthritis Initiative data from 2,271 individuals with knee osteoarthritis and a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or above, which examined the effects of “weight cycling” on OA outcomes.

Gabby Joseph, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, told the conference – which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International – that previous studies had shown weight loss improves OA symptoms and slow progression, and weight gain increases OA risk. However no studies had yet examined the effects of weight cycling.

The study compared 4 years of MRI data for those who showed less than 3% loss or gain in weight over that time – the control group – versus those who lost more than 5% over that time and those who gained more than 5%. Among these were 249 individuals in the top 10% of annual weight change over that period, who were designated as weight cyclers. They tended to be younger, female, and with slightly higher average BMI than noncyclers.

Weight cyclers had significantly greater progression of cartilage degeneration and bone marrow edema degeneration – as measured by whole-organ magnetic resonance score – than did noncyclers, regardless of their overall weight gain or loss by the end of the study period.

However, the study did not see any significant differences in meniscus progression between cyclers and noncyclers, and cartilage thickness decreased in all groups over the 4 years with no significant effects associated with weight gain, loss, or cycling. Dr. Joseph commented that future studies could use voxel-based relaxometry to more closely study localized cartilage abnormalities.

Researchers also examined the effect of weight cycling on changes to walking speed, and found weight cyclers had significantly lower walking speeds by the end of the 4 years, regardless of overall weight change.

“What we’ve seen is that fluctuations are not beneficial for your joints,” Dr. Joseph told the conference. “When we advise patients that they want to lose weight, we want to do this in a very steady fashion; we don’t want yo-yo dieting.” She gave the example of one patient who started the study with a BMI of 36, went up to 40 then went down to 32.

Commenting on the study, Lisa Carlesso, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said it addresses an important issue because weight cycling is common as people struggle to maintain weight loss.

While it is difficult to speculate on the physiological mechanisms that might explain the effect, Dr. Carlesso noted that there were significantly more women than men among the weight cyclers.

“We know, for example, that obese women with knee OA have significantly higher levels of the adipokine leptin, compared to men, and leptin is involved in cartilage degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said. “Similarly, we don’t have any information about joint alignment or measures of joint load, two things that could factor into the structural changes found.”

She suggested both these possibilities could be explored in future studies of weight cycling and its effects.

“It has opened up new lines of inquiry to be examined to mechanistically explain the relationship between cycling and worse cartilage and bone marrow degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

Repetitive weight loss and gain in overweight or obese patients with knee osteoarthritis is associated with significantly greater cartilage and bone marrow edema degeneration than stable weight or steady weight loss, research suggests.

A presentation at the OARSI 2021 World Congress outlined the results of a study using Osteoarthritis Initiative data from 2,271 individuals with knee osteoarthritis and a body mass index (BMI) of 25 kg/m2 or above, which examined the effects of “weight cycling” on OA outcomes.

Gabby Joseph, PhD, of the University of California, San Francisco, told the conference – which was sponsored by the Osteoarthritis Research Society International – that previous studies had shown weight loss improves OA symptoms and slow progression, and weight gain increases OA risk. However no studies had yet examined the effects of weight cycling.

The study compared 4 years of MRI data for those who showed less than 3% loss or gain in weight over that time – the control group – versus those who lost more than 5% over that time and those who gained more than 5%. Among these were 249 individuals in the top 10% of annual weight change over that period, who were designated as weight cyclers. They tended to be younger, female, and with slightly higher average BMI than noncyclers.

Weight cyclers had significantly greater progression of cartilage degeneration and bone marrow edema degeneration – as measured by whole-organ magnetic resonance score – than did noncyclers, regardless of their overall weight gain or loss by the end of the study period.

However, the study did not see any significant differences in meniscus progression between cyclers and noncyclers, and cartilage thickness decreased in all groups over the 4 years with no significant effects associated with weight gain, loss, or cycling. Dr. Joseph commented that future studies could use voxel-based relaxometry to more closely study localized cartilage abnormalities.

Researchers also examined the effect of weight cycling on changes to walking speed, and found weight cyclers had significantly lower walking speeds by the end of the 4 years, regardless of overall weight change.

“What we’ve seen is that fluctuations are not beneficial for your joints,” Dr. Joseph told the conference. “When we advise patients that they want to lose weight, we want to do this in a very steady fashion; we don’t want yo-yo dieting.” She gave the example of one patient who started the study with a BMI of 36, went up to 40 then went down to 32.

Commenting on the study, Lisa Carlesso, PhD, of McMaster University, Hamilton, Ont., said it addresses an important issue because weight cycling is common as people struggle to maintain weight loss.

While it is difficult to speculate on the physiological mechanisms that might explain the effect, Dr. Carlesso noted that there were significantly more women than men among the weight cyclers.

“We know, for example, that obese women with knee OA have significantly higher levels of the adipokine leptin, compared to men, and leptin is involved in cartilage degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said. “Similarly, we don’t have any information about joint alignment or measures of joint load, two things that could factor into the structural changes found.”

She suggested both these possibilities could be explored in future studies of weight cycling and its effects.

“It has opened up new lines of inquiry to be examined to mechanistically explain the relationship between cycling and worse cartilage and bone marrow degeneration,” Dr. Carlesso said.

The study was supported by the National Institutes of Health. No conflicts of interest were declared.

FROM OARSI 2021

High MRD rates with CAR T in r/r B-ALL in kids

It’s early days, but preliminary data show that a chimeric antigen receptor T-cell therapy (CAR T) product was associated with high rates of minimal residual disease (MRD) negativity, and complete or near-complete responses in children and adolescents with relapsed or refractory B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL).

Among 24 patients aged 3-20 years with relapsed or refractory B-ALL treated with the CAR T construct brexucabtagene autoleucel (KTE-X19; Tecartus), 16 had either a complete response or CR with incomplete recovery of blood counts (CRi), for a combined CR/CRi rate of 67%, reported Alan S. Wayne, MD, from Children’s Hospital Los Angeles and the University of Southern California Norris Comprehensive Cancer Center, also in Los Angeles.

“Optimized KTE-X19 formulation of 40 mL and revised toxicity management were associated with an improved risk/benefit profile,” he said in audio narration accompanying a poster presented during the annual meeting of the American Society of Pediatric Hematology/Oncology.

Although overall survival for children and adolescents receiving first-line therapy for B-ALL is associated with remission rates of 80% or more, the prognosis is poor following relapse, despite the availability of newer therapies such as blinatumomab (Blincyto) and inotuzumab (Besponsa), with a 1-year overall survival rate of approximately 36%, he said.

To see whether they could improve on these odds, Dr. Wayne and colleagues conducted the phase 1 Zuma-4 trial, a single-arm, open-label study in children and adolescents with relapsed/refractory B-ALL.

He reported long-term follow-up results from the study.

Zuma-4 details

A total of 24 patients, median age 14 (range 3 to 20) years, received the CAR T product. Four patients received the starting dose of 2 x 106 CAR T per kg (these patients were enrolled per protocol for evaluation of dose-limiting toxicities).

Following the initial dosing and evaluation of safety, 11 patients were treated with a dose of 1 x 106 cells per kg with a total volume of 68 mL, and 9 received 1 x 106 per kg at a volume of 40 mL (the dose being used in current phase 2 trials).

The median follow-up at the time of data cutoff in September 2020 was 36.1 months.

The combined CR/CRi rate was 75% for patients treated at the starting dose, 64% for patients treated at the 1 x 106 68-mL dose, and 67% for those who received the 48-mL dose.

The respective median durations of response were 4.14 months, 10.68 months, and not reached.

All patients who had an objective response had undetectable MRD assessed by flow cytometry with a sensitivity of .01%.

The therapy served as a bridge to allogeneic transplant in 16 patients, including 2 in the initial dose group, 8 in the 68-mL group, and 6 in the 40-mL group.

Median overall survival was not reached in either of the two 1 x 106–dose groups, but was 8 months in the 2 x 106 group.

There were no dose-limiting toxicities seen, and the adverse event profile was consistent with that seen with the use of CAR T therapy for other malignancies.

Patients treated at either the 68-mL or 40-mL 1 x 106–dose levels received tocilizumab only for neurologic events occurring in context with the cytokine release syndrome (CRS), and were started on steroids for grade 2 or greater neurologic events.

Rates of grade 3 or greater neurologic events were 25% in the initial-dose group, 27% in the 68-mL group, and 11% in the 40-mL group. Respective rates of grade 3 or greater CRS were 75%, 27%, and 22%.