User login

‘Where does it hurt?’: Primary care tips for common ortho problems

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Knee and shoulder pain are common complaints for patients in the primary care office.

But identifying the source of the pain can be complicated,

and an accurate diagnosis of the underlying cause of discomfort is key to appropriate management – whether that involves simple home care options of ice and rest or a recommendation for a follow-up with a specialist.

Speaking at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians, Greg Nakamoto, MD, department of orthopedics, Virginia Mason Medical Center, Seattle, discussed common knee and shoulder problems that patients often present with in the primary care setting, and offered tips on diagnosis and appropriate management.

The most common conditions causing knee pain are osteoarthritis and meniscal tears. “The differential for knee pain is broad,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “You have to have a way to divide it down, such as if it’s acute or chronic.”

The initial workup has several key components. The first steps: Determine the location of the pain – anterior, medial, lateral, posterior – and then whether it stems from an injury or is atraumatic.

“If you have to ask one question – ask where it hurts,” he said. “And is it from an injury or just wear and tear? That helps me when deciding if surgery is needed.”

Pain in the knee generally localizes well to the site of pathology, and knee pain of acute traumatic onset requires more scrutiny for problems best treated with early surgery. “This also helps establish whether radiographic findings are due to injury or degeneration,” Dr. Nakamoto said. “The presence of swelling guides the need for anti-inflammatories or cortisone.”

Palpating for tenderness along the joint line is important, as is palpating above and below the joint line, Dr. Nakamoto said.

“Tenderness limited to the joint line, combined with a meniscal exam maneuver that reproduces joint-line pain, is suggestive of pain from meniscal pathology,” he said.

Imaging is an important component of evaluating knee symptoms, and the question often arises as to when to order an MRI.

Dr. Nakamoto offered the following scenario: If significant osteoarthritis is evident on weight-bearing x-ray, treat the patient for the condition. However, if little or no osteoarthritis appears on x-ray, and if the onset of symptoms was traumatic and both patient history and physical examination suggest a meniscal tear, order an MRI.

An early MRI also is needed if the patient has had either atraumatic or traumatic onset of symptoms and their history and physical exams are suspicious for a mechanically locked or locking meniscus. For suspicion of a ruptured quadriceps or patellar tendon or a stress fracture, an MRI is needed urgently.

An MRI would be ordered later if the patient’s symptoms have not improved significantly after 3 months of conservative management.

Dr. Nakamoto stressed how common undiagnosed meniscus tears are in the general population. A third of men aged 50-59 years and nearly 20% of women in that age group have a tear, he said. “That number goes up to 56% and 51% in men and women aged 70-90 years, and 61% of these tears were in patients who were asymptomatic in the last month.”

In the setting of osteoarthritis, 76% of asymptomatic patients had a meniscus tear, and 91% of patients with symptomatic osteoarthritis had a meniscus tear, he added.

Treating knee pain

Treatment will vary depending on the underlying etiology of pain. For a possible meniscus tear, the recommendation is for a conservative intervention with ice, ibuprofen, knee immobilizer, and crutches, with a follow-up appointment in a week.

Three types of injections also can help:

- Cortisone for osteoarthritis or meniscus tears, swelling, and inflammation, and prophylaxis against inflammation.

- Viscosupplementation (intra‐articular hyaluronic acid) for chronic, baseline osteoarthritis symptoms.

- Regenerative therapies (platelet-rich plasma, stem cells, etc.) are used primarily for osteoarthritis (these do not regrow cartilage, but some patients report decreased pain).

The data on injections are mixed, Dr. Nakamoto said. For example, the results of a 2015 Cochrane review on cortisone injections for osteoarthritis reported that the benefits were small to moderate at 4‐6 weeks, and small to none at 13 weeks.

“There is a lot of controversy for viscosupplementation despite all of the data on it,” he said. “But the recommendations from professional organizations are mixed.”

He noted that he has been using viscosupplementation since the 1990s, and some patients do benefit from it.

Shoulder pain

The most common causes of shoulder pain are adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tears and tendinopathy, and impingement.

As with knee pain, the same assessment routine largely applies.

First, pinpoint the location: Is the trouble spot the lateral shoulder and upper arm, the trapezial ridge, or the shoulder blade?

Next, assess pain on movement: Does the patient experience discomfort reaching overhead or behind the back, or moving at the glenohumeral joint/capsule and engaging the rotator cuff? Check for stiffness, weakness, and decreased range of motion in the rotator cuff.

Determine if the cause of the pain is traumatic or atraumatic and stems from an acute injury versus degeneration or overuse.

As with the knee, imaging is a major component of the assessment and typically involves the use of x-ray. An MRI may be required for evaluating full- and partial-thickness tears and when contemplating surgery.

MRI also is necessary for evaluating cases of acute, traumatic shoulder injury, and patients exhibiting disability suggestive of a rotator cuff tear in an otherwise healthy tendon.

Some pain can be treated with cortisone injections or regenerative therapies, which generally are given at the acromioclavicular or glenohumeral joints or in the subacromial space. A 2005 meta-analysis found that subacromial injections of corticosteroids are effective for improvement for rotator cuff tendinitis up to a 9‐month period.

Surgery may be warranted in some cases, Dr. Nakamoto said. These include adhesive capsulitis, rotator cuff tear, acute traumatic injury in an otherwise healthy tendon, and chronic (or acute-on-chronic) tears in a degenerative tendon following a trial of conservative therapy.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

How to communicate effectively with patients when tension is high

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

“At my hospital, it was such a big thing to make sure that families are called,” said Dr. Nwankwo, in an interview following a session on compassionate communication at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians. “So you have 19 patients, and you have to call almost every family to update them. And then you call, and they say, ‘Call this person as well.’ You feel like you’re at your wit’s end a lot of times.”

Sometimes, she has had to dig deep to find the empathy for patients that she knows her patients deserve.

“You really want to care by thinking about where is this patient coming from? What’s going on in their lives? And not just label them a difficult patient,” she said.

Become curious

Auguste Fortin, MD, MPH, offered advice for handling patient interactions under these kinds of circumstances, while serving as a moderator during the session.

“When the going gets tough, turn to wonder.” Become curious about why a patient might be feeling the way they are, he said.

Dr. Fortin, professor of internal medicine at Yale University, New Haven, Conn., said using the ADOBE acronym, has helped him more effectively communicate with his patients. This tool cues him to keep the following in mind: acknowledge, discover, opportunity, boundary setting, and extend.

He went on to explain to the audience why thinking about these terms is useful when interacting with patients.

First, acknowledge the feelings of the patient. Noting that a patient is angry, perhaps counterintuitively, helps, he said. In fact, not acknowledging the anger “throws gasoline on the fire.”

Then, discover the cause of their emotion. Saying "tell me more" and "help me understand" can be powerful tools, he noted.

Next, take this as an opportunity for empathy – especially important to remember when you’re being verbally attacked.

Boundary setting is important, because it lets the patient know that the conversation won’t continue unless they show the same respect the physician is showing, he said.

Finally, physicians can extend the system of support by asking others – such as colleagues or security – for help.

Use the NURS guide to show empathy

Dr. Fortin said he uses the “NURS” guide or calling to mind “name, express, respect, and support” to show empathy:

This involves naming a patient’s emotion; expressing understanding, with phrases like "I can see how you could be …"; showing respect, acknowledging a patient is going through a lot; and offering support, by saying something like, "Let’s see what we can do together to get to the bottom of this," he explained.

“My lived experience in using [these] in this order is that by the end of it, the patient cannot stay mad at me,” Dr. Fortin said.

“It’s really quite remarkable,” he added.

Steps for nonviolent communication

Rebecca Andrews, MD, MS, another moderator for the session, offered these steps for “nonviolent communication”:

- Observing the situation without blame or judgment.

- Telling the person how this situation makes you feel.

- Connecting with a need of the other person.

- Making a request that is specific and based on action, rather than a request not to do something, such as "Would you be willing to … ?"

Dr. Andrews, who is professor of medicine at the University of Connecticut, Farmington, said this approach has worked well for her, both in interactions with patients and in her personal life.

“It is evidence based that compassion actually makes care better,” she noted.

Varun Jain, MD, a member of the audience, expressed gratitude to the session’s speakers for teaching him something that he had not learned in medical school or residency.

“Every week you will have one or two people who will be labeled as ‘difficult,’ ” and it was nice to have some proven advice on how to handle these tough interactions, said the hospitalist at St. Francis Hospital in Hartford, Conn.

“We never got any actual training on this, and we were expected to know this because we are just physicians, and physicians are expected to be compassionate,” Dr. Jain said. “No one taught us how to have compassion.”

Dr. Fortin and Dr. Andrews disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

AT INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

Homelessness seems to have greater link to death than common diseases, says physician

On a return visit about 10 years later, Dr. Perri went to the park and inquired about the men.

“I came to the horrible realization that all of these people were dead. All of them in 10 years,” he continued, speaking to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

People experiencing homelessness don’t have to have such a grim health outlook, said Dr. Perri, who is medical director of the Center for Inclusion Health at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh.

During his talk, filled with jarring statistics on the health plight of those who struggle to stay sheltered, Dr. Perri said that many of the things that sicken and kill these people are the same things that sicken and kill others – liver disease, congestive heart failure, substance abuse. But the system isn’t equipped to handle the problems.

“Their needs are actually straightforward, they’re easy to describe,” he declared. “They’re known quantities. But the way that our systems respond, or don’t respond, to that creates the complexity. It’s the systems that are complex.”

Morbidity, mortality rates ‘go off a cliff’

A 2017 study in The Lancet compared morbidity and mortality in high-income countries, grouping people by their “level of deprivation.” The morbidity and mortality ticked higher with each deprivation level, but skyrocketed – nearly 10 times higher – for the group that included those experiencing homelessness or imprisonment, sex workers, and those with substance use disorders. As Dr. Perri put it, the rates “go off a cliff.”

Studies by the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless program have tracked mortality, and from 1988 to 1993 the average age at death was 47, so, “if you died while homeless, you probably died young.” Moreover, from their first contact to receive care through the program, to their death, only 25 months had elapsed.

“If there’s going to be an effective health care intervention, an acute one at least, you’ve got to get cracking,” Dr. Perri said.

Age at death has improved somewhat over time but drug overdose has become a much more common cause, Dr. Perri noted.

“There is utilitarian value in learning from people experiencing homelessness,” he said.

The same program looked at a high-risk cohort of 199 – those who went unsheltered for more than 6 months,were age 60 or older, or had certain serious health conditions, such as cirrhosis, substance abuse, and AIDS. A third of these people died within 5 years.

“There aren’t any other common diseases that I’m aware of that have statistics like that,” he said.

These people had an average of 31 emergency department visits a year and accounted for 871 hospitalizations. The estimated cost per-person, per-year was $22,000, while the average annual rent for a one-bedroom in Boston was $10,000.

“We’re hemorrhaging utilization around this population,” Dr. Perri said. “Maybe it makes sense to invest in something else other than acute health care. It’s not really yielding very much return on investment.”

Street medicine could be the answer

Housing First, a program to provide housing without the need to meet preconditions such as sobriety or passing background checks, has had a nonsignificant effect on mortality, substance use disorders, and mental health but has improved self-reported health status and quality of life. Analyses of the program suggest that better interventions are needed, Dr. Perri said.

Street medicine could be an answer, he said. Teams of medical staff go to where the people are, and the concept is intended as a continuous, cost-effective, flexible approach to care. Lehigh Valley Street Medicine in Pennsylvania has reported a reduction in emergency department visits and hospitalizations, Dr. Perri said. The programs are still too new to gauge the effect on actual health outcomes, but they hold the promise of being able to do so, he continued.

Curiosity about those experiencing homeless is a key first step in improving care, he said. The HOUSED BEDS tool, developed in Los Angeles, can help guide clinicians through their interactions with patients who do not have homes.

Dr. Perri said it is “enlightening” when you “express interest, genuine curiosity, about other people’s experiences.”

Catherine Kiley, MD, a retired internal medicine physician who volunteers as a preceptor for medical students in Cincinnati, said there is a void when it comes to teaching students about those experiencing homelessness.

“I don’t think there’s much of this type of discussion that they’re exposed to as part of medical education,” Dr. Kiley said. “Their experiences over time, as with most of medicine, will inform them.”

But the findings shared in the session show “how great the need is to speak out, speak up, about patients as people, and what they have to teach us.”

Dr. Perri disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On a return visit about 10 years later, Dr. Perri went to the park and inquired about the men.

“I came to the horrible realization that all of these people were dead. All of them in 10 years,” he continued, speaking to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

People experiencing homelessness don’t have to have such a grim health outlook, said Dr. Perri, who is medical director of the Center for Inclusion Health at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh.

During his talk, filled with jarring statistics on the health plight of those who struggle to stay sheltered, Dr. Perri said that many of the things that sicken and kill these people are the same things that sicken and kill others – liver disease, congestive heart failure, substance abuse. But the system isn’t equipped to handle the problems.

“Their needs are actually straightforward, they’re easy to describe,” he declared. “They’re known quantities. But the way that our systems respond, or don’t respond, to that creates the complexity. It’s the systems that are complex.”

Morbidity, mortality rates ‘go off a cliff’

A 2017 study in The Lancet compared morbidity and mortality in high-income countries, grouping people by their “level of deprivation.” The morbidity and mortality ticked higher with each deprivation level, but skyrocketed – nearly 10 times higher – for the group that included those experiencing homelessness or imprisonment, sex workers, and those with substance use disorders. As Dr. Perri put it, the rates “go off a cliff.”

Studies by the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless program have tracked mortality, and from 1988 to 1993 the average age at death was 47, so, “if you died while homeless, you probably died young.” Moreover, from their first contact to receive care through the program, to their death, only 25 months had elapsed.

“If there’s going to be an effective health care intervention, an acute one at least, you’ve got to get cracking,” Dr. Perri said.

Age at death has improved somewhat over time but drug overdose has become a much more common cause, Dr. Perri noted.

“There is utilitarian value in learning from people experiencing homelessness,” he said.

The same program looked at a high-risk cohort of 199 – those who went unsheltered for more than 6 months,were age 60 or older, or had certain serious health conditions, such as cirrhosis, substance abuse, and AIDS. A third of these people died within 5 years.

“There aren’t any other common diseases that I’m aware of that have statistics like that,” he said.

These people had an average of 31 emergency department visits a year and accounted for 871 hospitalizations. The estimated cost per-person, per-year was $22,000, while the average annual rent for a one-bedroom in Boston was $10,000.

“We’re hemorrhaging utilization around this population,” Dr. Perri said. “Maybe it makes sense to invest in something else other than acute health care. It’s not really yielding very much return on investment.”

Street medicine could be the answer

Housing First, a program to provide housing without the need to meet preconditions such as sobriety or passing background checks, has had a nonsignificant effect on mortality, substance use disorders, and mental health but has improved self-reported health status and quality of life. Analyses of the program suggest that better interventions are needed, Dr. Perri said.

Street medicine could be an answer, he said. Teams of medical staff go to where the people are, and the concept is intended as a continuous, cost-effective, flexible approach to care. Lehigh Valley Street Medicine in Pennsylvania has reported a reduction in emergency department visits and hospitalizations, Dr. Perri said. The programs are still too new to gauge the effect on actual health outcomes, but they hold the promise of being able to do so, he continued.

Curiosity about those experiencing homeless is a key first step in improving care, he said. The HOUSED BEDS tool, developed in Los Angeles, can help guide clinicians through their interactions with patients who do not have homes.

Dr. Perri said it is “enlightening” when you “express interest, genuine curiosity, about other people’s experiences.”

Catherine Kiley, MD, a retired internal medicine physician who volunteers as a preceptor for medical students in Cincinnati, said there is a void when it comes to teaching students about those experiencing homelessness.

“I don’t think there’s much of this type of discussion that they’re exposed to as part of medical education,” Dr. Kiley said. “Their experiences over time, as with most of medicine, will inform them.”

But the findings shared in the session show “how great the need is to speak out, speak up, about patients as people, and what they have to teach us.”

Dr. Perri disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

On a return visit about 10 years later, Dr. Perri went to the park and inquired about the men.

“I came to the horrible realization that all of these people were dead. All of them in 10 years,” he continued, speaking to an audience at the annual meeting of the American College of Physicians.

People experiencing homelessness don’t have to have such a grim health outlook, said Dr. Perri, who is medical director of the Center for Inclusion Health at the Allegheny Health Network in Pittsburgh.

During his talk, filled with jarring statistics on the health plight of those who struggle to stay sheltered, Dr. Perri said that many of the things that sicken and kill these people are the same things that sicken and kill others – liver disease, congestive heart failure, substance abuse. But the system isn’t equipped to handle the problems.

“Their needs are actually straightforward, they’re easy to describe,” he declared. “They’re known quantities. But the way that our systems respond, or don’t respond, to that creates the complexity. It’s the systems that are complex.”

Morbidity, mortality rates ‘go off a cliff’

A 2017 study in The Lancet compared morbidity and mortality in high-income countries, grouping people by their “level of deprivation.” The morbidity and mortality ticked higher with each deprivation level, but skyrocketed – nearly 10 times higher – for the group that included those experiencing homelessness or imprisonment, sex workers, and those with substance use disorders. As Dr. Perri put it, the rates “go off a cliff.”

Studies by the Boston Healthcare for the Homeless program have tracked mortality, and from 1988 to 1993 the average age at death was 47, so, “if you died while homeless, you probably died young.” Moreover, from their first contact to receive care through the program, to their death, only 25 months had elapsed.

“If there’s going to be an effective health care intervention, an acute one at least, you’ve got to get cracking,” Dr. Perri said.

Age at death has improved somewhat over time but drug overdose has become a much more common cause, Dr. Perri noted.

“There is utilitarian value in learning from people experiencing homelessness,” he said.

The same program looked at a high-risk cohort of 199 – those who went unsheltered for more than 6 months,were age 60 or older, or had certain serious health conditions, such as cirrhosis, substance abuse, and AIDS. A third of these people died within 5 years.

“There aren’t any other common diseases that I’m aware of that have statistics like that,” he said.

These people had an average of 31 emergency department visits a year and accounted for 871 hospitalizations. The estimated cost per-person, per-year was $22,000, while the average annual rent for a one-bedroom in Boston was $10,000.

“We’re hemorrhaging utilization around this population,” Dr. Perri said. “Maybe it makes sense to invest in something else other than acute health care. It’s not really yielding very much return on investment.”

Street medicine could be the answer

Housing First, a program to provide housing without the need to meet preconditions such as sobriety or passing background checks, has had a nonsignificant effect on mortality, substance use disorders, and mental health but has improved self-reported health status and quality of life. Analyses of the program suggest that better interventions are needed, Dr. Perri said.

Street medicine could be an answer, he said. Teams of medical staff go to where the people are, and the concept is intended as a continuous, cost-effective, flexible approach to care. Lehigh Valley Street Medicine in Pennsylvania has reported a reduction in emergency department visits and hospitalizations, Dr. Perri said. The programs are still too new to gauge the effect on actual health outcomes, but they hold the promise of being able to do so, he continued.

Curiosity about those experiencing homeless is a key first step in improving care, he said. The HOUSED BEDS tool, developed in Los Angeles, can help guide clinicians through their interactions with patients who do not have homes.

Dr. Perri said it is “enlightening” when you “express interest, genuine curiosity, about other people’s experiences.”

Catherine Kiley, MD, a retired internal medicine physician who volunteers as a preceptor for medical students in Cincinnati, said there is a void when it comes to teaching students about those experiencing homelessness.

“I don’t think there’s much of this type of discussion that they’re exposed to as part of medical education,” Dr. Kiley said. “Their experiences over time, as with most of medicine, will inform them.”

But the findings shared in the session show “how great the need is to speak out, speak up, about patients as people, and what they have to teach us.”

Dr. Perri disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

REPORTING FROM INTERNAL MEDICINE 2022

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Multiple Sclerosis May 2022

Portaccio and colleagues explored this issue and concluded that disease progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) was a major contributor of confirmed disability accrual (CDA) in early relapse after the onset of MS, with age being a major determinant in the way that CDA occurs. In a retrospective cohort analysis of 5169 patients with either clinically isolated syndrome or early relapsing-remitting MS who were assessed within 1 year of onset and followed-up for ≥ 5 years, PIRA accounted for 27.6% of disability-worsening events, whereas relapse-associated worsening accounted for 17.8% of events, with relapse-associated worsening being more frequent in younger (hazard ratio [HR] 0.87) and PIRA in older (HR 1.19; both P < .001) patients. Recognition of disease relapse or progression is not always simple in a complex disease, but failure to recognize these issues can result in long-term accumulation of economically important disability. Multiple other issues related to effective disease management also require effective juggling in routine care. Adherence to treatment, timing of DMT change, and interval between discontinuing a DMT and starting a different one continue to be critical concerns as well. Malpas and associates explored this issue and noted that the importance of adherence impact on disease control also relates to treatment interruption and timing of duration between stopping one DMT and starting another agent. The annualized relapse rate (ARR) and the rate of severe relapses was explored in a cohort of 685 people with MS and did not increase significantly after discontinuation of fingolimod in this population, but delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse. The ARR was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior to and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of DMT, or if change in DMT was delayed from 2 to 4 months, vs beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse. Discontinuation of DMT or treatment interruption also relates to planned or unplanned pregnancy in people with MS. In another study Portaccio and colleagues continued treatment with natalizumab until conception and then restarted treatment within 1 month after delivery. This reduced the risk for disease activity more than natalizumab cessation before conception or restarting 1 month after delivery in women with MS. No major developmental abnormalities were noted in the infants born of 72 pregnancies in 70 women with MS who were treated for at least 2 years. Specifically, relapses occurred in 29.4% of people with MS treated until conception vs 70.2% in those who discontinued prior to conception, after a mean follow-up of 6.1 years (P = .001), with timing of treatment cessation being the only predictor of relapses (HR 4.1; P = .003). No developmental abnormalities were observed in the infants.

Practical points for the treating clinician are many and continue to highlight the complexity of managing people with MS in the real world, with real issues from COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, recognition or awareness of relapse, and the increased challenges of adherence and timing of DMT change and of DMT use relative to pregnancy. Data-driven, reliable, relevant information is critical to incorporate into routine care to enhance and optimize decision-making.

Portaccio and colleagues explored this issue and concluded that disease progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) was a major contributor of confirmed disability accrual (CDA) in early relapse after the onset of MS, with age being a major determinant in the way that CDA occurs. In a retrospective cohort analysis of 5169 patients with either clinically isolated syndrome or early relapsing-remitting MS who were assessed within 1 year of onset and followed-up for ≥ 5 years, PIRA accounted for 27.6% of disability-worsening events, whereas relapse-associated worsening accounted for 17.8% of events, with relapse-associated worsening being more frequent in younger (hazard ratio [HR] 0.87) and PIRA in older (HR 1.19; both P < .001) patients. Recognition of disease relapse or progression is not always simple in a complex disease, but failure to recognize these issues can result in long-term accumulation of economically important disability. Multiple other issues related to effective disease management also require effective juggling in routine care. Adherence to treatment, timing of DMT change, and interval between discontinuing a DMT and starting a different one continue to be critical concerns as well. Malpas and associates explored this issue and noted that the importance of adherence impact on disease control also relates to treatment interruption and timing of duration between stopping one DMT and starting another agent. The annualized relapse rate (ARR) and the rate of severe relapses was explored in a cohort of 685 people with MS and did not increase significantly after discontinuation of fingolimod in this population, but delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse. The ARR was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior to and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of DMT, or if change in DMT was delayed from 2 to 4 months, vs beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse. Discontinuation of DMT or treatment interruption also relates to planned or unplanned pregnancy in people with MS. In another study Portaccio and colleagues continued treatment with natalizumab until conception and then restarted treatment within 1 month after delivery. This reduced the risk for disease activity more than natalizumab cessation before conception or restarting 1 month after delivery in women with MS. No major developmental abnormalities were noted in the infants born of 72 pregnancies in 70 women with MS who were treated for at least 2 years. Specifically, relapses occurred in 29.4% of people with MS treated until conception vs 70.2% in those who discontinued prior to conception, after a mean follow-up of 6.1 years (P = .001), with timing of treatment cessation being the only predictor of relapses (HR 4.1; P = .003). No developmental abnormalities were observed in the infants.

Practical points for the treating clinician are many and continue to highlight the complexity of managing people with MS in the real world, with real issues from COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, recognition or awareness of relapse, and the increased challenges of adherence and timing of DMT change and of DMT use relative to pregnancy. Data-driven, reliable, relevant information is critical to incorporate into routine care to enhance and optimize decision-making.

Portaccio and colleagues explored this issue and concluded that disease progression independent of relapse activity (PIRA) was a major contributor of confirmed disability accrual (CDA) in early relapse after the onset of MS, with age being a major determinant in the way that CDA occurs. In a retrospective cohort analysis of 5169 patients with either clinically isolated syndrome or early relapsing-remitting MS who were assessed within 1 year of onset and followed-up for ≥ 5 years, PIRA accounted for 27.6% of disability-worsening events, whereas relapse-associated worsening accounted for 17.8% of events, with relapse-associated worsening being more frequent in younger (hazard ratio [HR] 0.87) and PIRA in older (HR 1.19; both P < .001) patients. Recognition of disease relapse or progression is not always simple in a complex disease, but failure to recognize these issues can result in long-term accumulation of economically important disability. Multiple other issues related to effective disease management also require effective juggling in routine care. Adherence to treatment, timing of DMT change, and interval between discontinuing a DMT and starting a different one continue to be critical concerns as well. Malpas and associates explored this issue and noted that the importance of adherence impact on disease control also relates to treatment interruption and timing of duration between stopping one DMT and starting another agent. The annualized relapse rate (ARR) and the rate of severe relapses was explored in a cohort of 685 people with MS and did not increase significantly after discontinuation of fingolimod in this population, but delaying the commencement of immunotherapy increased the risk for relapse. The ARR was not significantly different during and after fingolimod cessation (mean difference −0.06; 95% CI −0.14 to 0.01), with no severe relapses reported in the year prior to and after fingolimod cessation. However, delaying the recommencement of DMT, or if change in DMT was delayed from 2 to 4 months, vs beginning within 2 months (odds ratio 1.67; 95% CI 1.22-2.27) was associated with a higher risk for relapse. Discontinuation of DMT or treatment interruption also relates to planned or unplanned pregnancy in people with MS. In another study Portaccio and colleagues continued treatment with natalizumab until conception and then restarted treatment within 1 month after delivery. This reduced the risk for disease activity more than natalizumab cessation before conception or restarting 1 month after delivery in women with MS. No major developmental abnormalities were noted in the infants born of 72 pregnancies in 70 women with MS who were treated for at least 2 years. Specifically, relapses occurred in 29.4% of people with MS treated until conception vs 70.2% in those who discontinued prior to conception, after a mean follow-up of 6.1 years (P = .001), with timing of treatment cessation being the only predictor of relapses (HR 4.1; P = .003). No developmental abnormalities were observed in the infants.

Practical points for the treating clinician are many and continue to highlight the complexity of managing people with MS in the real world, with real issues from COVID-19 vaccination, SARS-CoV-2 infection, recognition or awareness of relapse, and the increased challenges of adherence and timing of DMT change and of DMT use relative to pregnancy. Data-driven, reliable, relevant information is critical to incorporate into routine care to enhance and optimize decision-making.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Breast Cancer May 2022

A meta-analysis including over 5000 patients with metastatic hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and HER2- breast cancer showed a significant overall survival (OS) benefit with the addition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors to endocrine therapy (hazard ratio 1.33; P < .001), albeit with higher rates of toxicities, including neutropenia, leukopenia, and diarrhea.3 The MONALEESA-2 study randomly assigned 668 postmenopausal women with metastatic HR+/HER2- breast cancer, treatment-naive in the advanced setting, to either ribociclib or placebo plus letrozole. Updated results with a median follow-up of 6.6 years demonstrated a significant OS benefit with ribociclib + letrozole compared with placebo + letrozole (median OS 63.9 months vs 51.4 months; hazard ratio 0.76; P = .008) (Hortobagyi and colleagues). An OS > 5 years with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy is certainly impressive, and efficacy as well as respective toxicities of the various CDK 4/6 inhibitors are factors taken into consideration when choosing the appropriate therapy for an individual patient.

The optimization of adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for HR+ early breast cancer, including use of ovarian suppression and extended adjuvant therapy, has improved outcomes for these women. However, there is a high-risk subset for whom the risk for distant recurrence persists. The phase 3 monarchE trial, which included 5637 patients with high-risk early breast cancer (≥ 4 positive nodes, or 1-3 nodes and either tumor size ≥ 5 cm, histologic grade 3, or central Ki-67 ≥ 20%), demonstrated benefits in invasive disease-free and distant-relapse-free survival with the addition of abemaciclib for 2 years to ET. A safety analysis of the monarchE study among patients who had received at least one dose of the study drug (n = 5591) demonstrated an overall manageable side-effect profile, with the majority of these toxicities addressed via dose holds/reductions or supportive medications (Rugo and colleagues). Abemaciclib + ET led to higher incidence of grade ≥ 3 adverse events vs ET alone (49.7% vs 16.3%), with neutropenia being the most frequent (grade 3 = 19.6%) although without significant clinical implications. Diarrhea was common (83.5%), although the majority was low grade (grade 1/2 = 75.7%), with grade 2/3 events characterized by early onset and short duration. Discontinuation of abemaciclib occurred in 18.5%, with two thirds due to grade 1/2 events and in over half without dose reduction.4 These findings show an acceptable safety profile with abemaciclib in the curative setting and highlight the importance of education, recognition, and early management of side effects to maintain patients on treatment.

The heterogeneity of tumor biology within the HR+ breast cancer subtype indicates the need to refine treatment regimens for an individual patient. Genomic assays (70-gene signature and 21-gene recurrence score) have helped tailor adjuvant systemic therapy and in many cases have identified women for whom chemotherapy can be omitted. CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown impressive activity in the metastatic/advanced setting, although results from trials in the adjuvant setting have produced mixed results. The phase 2 NEOPAL trial evaluated the combination of letrozole + palbociclib vs chemotherapy (sequential anthracycline-taxane) among 106 postmenopausal women with high-risk, HR+/HER2- early breast cancer (luminal B or luminal A with nodal involvement). At a median follow-up of 40.4 months, 3-year PFS (hazard ratio 1.01; P = .98) and invasive disease-free survival (hazard ratio 0.83; P = .71) were similar in the letrozole + palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (Delaloge and colleagues). The phase 2 CORALLEEN trial,5 which investigated neoadjuvant letrozole + ribociclib vs chemotherapy in HR+/HER2- luminal B early breast cancer, demonstrated similar percentages of patients achieving downstaging via molecular assessment at the time of surgery. The neoadjuvant space represents a valuable setting to further study CDK 4/6 inhibitors as well as other novel therapies; endpoints including pathologic complete response and residual cancer burden correlating with long-term outcomes can provide a more rapid means to identify effective therapies. Translational biomarkers can be gathered and adjuvant strategies can be tailored based on response.

Additional References

- Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al; DESTINY-Breast01 Investigators. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:610-621. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510 Source

- Hurvitz S, Kim S-B, Chung W-P, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201a) versus trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients (pts) with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (mBC): Subgroup analyses from the randomized phase 3 study DESTINY-Breast03. Presented at 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 7-10, 2021;General Session, GS3-01. Source

- Li J, Huo X, Zhao F, et al. Association of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 inhibitors with survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020312. Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20312 Source

- Harbeck N, Rastogi P, Martin M, et al. Adjuvant abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for high-risk early breast cancer: Updated efficacy and Ki-67 analysis from the monarchE study. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1571-1581. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.015 Source

- Prat A, Saura C, Pascual T, et al. Ribociclib plus letrozole versus chemotherapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2- negative, luminal B breast cancer (CORALLEEN): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:33-43. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30786-7 Source

A meta-analysis including over 5000 patients with metastatic hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and HER2- breast cancer showed a significant overall survival (OS) benefit with the addition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors to endocrine therapy (hazard ratio 1.33; P < .001), albeit with higher rates of toxicities, including neutropenia, leukopenia, and diarrhea.3 The MONALEESA-2 study randomly assigned 668 postmenopausal women with metastatic HR+/HER2- breast cancer, treatment-naive in the advanced setting, to either ribociclib or placebo plus letrozole. Updated results with a median follow-up of 6.6 years demonstrated a significant OS benefit with ribociclib + letrozole compared with placebo + letrozole (median OS 63.9 months vs 51.4 months; hazard ratio 0.76; P = .008) (Hortobagyi and colleagues). An OS > 5 years with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy is certainly impressive, and efficacy as well as respective toxicities of the various CDK 4/6 inhibitors are factors taken into consideration when choosing the appropriate therapy for an individual patient.

The optimization of adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for HR+ early breast cancer, including use of ovarian suppression and extended adjuvant therapy, has improved outcomes for these women. However, there is a high-risk subset for whom the risk for distant recurrence persists. The phase 3 monarchE trial, which included 5637 patients with high-risk early breast cancer (≥ 4 positive nodes, or 1-3 nodes and either tumor size ≥ 5 cm, histologic grade 3, or central Ki-67 ≥ 20%), demonstrated benefits in invasive disease-free and distant-relapse-free survival with the addition of abemaciclib for 2 years to ET. A safety analysis of the monarchE study among patients who had received at least one dose of the study drug (n = 5591) demonstrated an overall manageable side-effect profile, with the majority of these toxicities addressed via dose holds/reductions or supportive medications (Rugo and colleagues). Abemaciclib + ET led to higher incidence of grade ≥ 3 adverse events vs ET alone (49.7% vs 16.3%), with neutropenia being the most frequent (grade 3 = 19.6%) although without significant clinical implications. Diarrhea was common (83.5%), although the majority was low grade (grade 1/2 = 75.7%), with grade 2/3 events characterized by early onset and short duration. Discontinuation of abemaciclib occurred in 18.5%, with two thirds due to grade 1/2 events and in over half without dose reduction.4 These findings show an acceptable safety profile with abemaciclib in the curative setting and highlight the importance of education, recognition, and early management of side effects to maintain patients on treatment.

The heterogeneity of tumor biology within the HR+ breast cancer subtype indicates the need to refine treatment regimens for an individual patient. Genomic assays (70-gene signature and 21-gene recurrence score) have helped tailor adjuvant systemic therapy and in many cases have identified women for whom chemotherapy can be omitted. CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown impressive activity in the metastatic/advanced setting, although results from trials in the adjuvant setting have produced mixed results. The phase 2 NEOPAL trial evaluated the combination of letrozole + palbociclib vs chemotherapy (sequential anthracycline-taxane) among 106 postmenopausal women with high-risk, HR+/HER2- early breast cancer (luminal B or luminal A with nodal involvement). At a median follow-up of 40.4 months, 3-year PFS (hazard ratio 1.01; P = .98) and invasive disease-free survival (hazard ratio 0.83; P = .71) were similar in the letrozole + palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (Delaloge and colleagues). The phase 2 CORALLEEN trial,5 which investigated neoadjuvant letrozole + ribociclib vs chemotherapy in HR+/HER2- luminal B early breast cancer, demonstrated similar percentages of patients achieving downstaging via molecular assessment at the time of surgery. The neoadjuvant space represents a valuable setting to further study CDK 4/6 inhibitors as well as other novel therapies; endpoints including pathologic complete response and residual cancer burden correlating with long-term outcomes can provide a more rapid means to identify effective therapies. Translational biomarkers can be gathered and adjuvant strategies can be tailored based on response.

Additional References

- Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al; DESTINY-Breast01 Investigators. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:610-621. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510 Source

- Hurvitz S, Kim S-B, Chung W-P, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201a) versus trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients (pts) with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (mBC): Subgroup analyses from the randomized phase 3 study DESTINY-Breast03. Presented at 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 7-10, 2021;General Session, GS3-01. Source

- Li J, Huo X, Zhao F, et al. Association of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 inhibitors with survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020312. Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20312 Source

- Harbeck N, Rastogi P, Martin M, et al. Adjuvant abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for high-risk early breast cancer: Updated efficacy and Ki-67 analysis from the monarchE study. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1571-1581. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.015 Source

- Prat A, Saura C, Pascual T, et al. Ribociclib plus letrozole versus chemotherapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2- negative, luminal B breast cancer (CORALLEEN): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:33-43. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30786-7 Source

A meta-analysis including over 5000 patients with metastatic hormone receptor–positive (HR+) and HER2- breast cancer showed a significant overall survival (OS) benefit with the addition of cyclin-dependent kinase (CDK) 4/6 inhibitors to endocrine therapy (hazard ratio 1.33; P < .001), albeit with higher rates of toxicities, including neutropenia, leukopenia, and diarrhea.3 The MONALEESA-2 study randomly assigned 668 postmenopausal women with metastatic HR+/HER2- breast cancer, treatment-naive in the advanced setting, to either ribociclib or placebo plus letrozole. Updated results with a median follow-up of 6.6 years demonstrated a significant OS benefit with ribociclib + letrozole compared with placebo + letrozole (median OS 63.9 months vs 51.4 months; hazard ratio 0.76; P = .008) (Hortobagyi and colleagues). An OS > 5 years with ribociclib plus endocrine therapy is certainly impressive, and efficacy as well as respective toxicities of the various CDK 4/6 inhibitors are factors taken into consideration when choosing the appropriate therapy for an individual patient.

The optimization of adjuvant endocrine therapy (ET) for HR+ early breast cancer, including use of ovarian suppression and extended adjuvant therapy, has improved outcomes for these women. However, there is a high-risk subset for whom the risk for distant recurrence persists. The phase 3 monarchE trial, which included 5637 patients with high-risk early breast cancer (≥ 4 positive nodes, or 1-3 nodes and either tumor size ≥ 5 cm, histologic grade 3, or central Ki-67 ≥ 20%), demonstrated benefits in invasive disease-free and distant-relapse-free survival with the addition of abemaciclib for 2 years to ET. A safety analysis of the monarchE study among patients who had received at least one dose of the study drug (n = 5591) demonstrated an overall manageable side-effect profile, with the majority of these toxicities addressed via dose holds/reductions or supportive medications (Rugo and colleagues). Abemaciclib + ET led to higher incidence of grade ≥ 3 adverse events vs ET alone (49.7% vs 16.3%), with neutropenia being the most frequent (grade 3 = 19.6%) although without significant clinical implications. Diarrhea was common (83.5%), although the majority was low grade (grade 1/2 = 75.7%), with grade 2/3 events characterized by early onset and short duration. Discontinuation of abemaciclib occurred in 18.5%, with two thirds due to grade 1/2 events and in over half without dose reduction.4 These findings show an acceptable safety profile with abemaciclib in the curative setting and highlight the importance of education, recognition, and early management of side effects to maintain patients on treatment.

The heterogeneity of tumor biology within the HR+ breast cancer subtype indicates the need to refine treatment regimens for an individual patient. Genomic assays (70-gene signature and 21-gene recurrence score) have helped tailor adjuvant systemic therapy and in many cases have identified women for whom chemotherapy can be omitted. CDK 4/6 inhibitors have shown impressive activity in the metastatic/advanced setting, although results from trials in the adjuvant setting have produced mixed results. The phase 2 NEOPAL trial evaluated the combination of letrozole + palbociclib vs chemotherapy (sequential anthracycline-taxane) among 106 postmenopausal women with high-risk, HR+/HER2- early breast cancer (luminal B or luminal A with nodal involvement). At a median follow-up of 40.4 months, 3-year PFS (hazard ratio 1.01; P = .98) and invasive disease-free survival (hazard ratio 0.83; P = .71) were similar in the letrozole + palbociclib and chemotherapy arms (Delaloge and colleagues). The phase 2 CORALLEEN trial,5 which investigated neoadjuvant letrozole + ribociclib vs chemotherapy in HR+/HER2- luminal B early breast cancer, demonstrated similar percentages of patients achieving downstaging via molecular assessment at the time of surgery. The neoadjuvant space represents a valuable setting to further study CDK 4/6 inhibitors as well as other novel therapies; endpoints including pathologic complete response and residual cancer burden correlating with long-term outcomes can provide a more rapid means to identify effective therapies. Translational biomarkers can be gathered and adjuvant strategies can be tailored based on response.

Additional References

- Modi S, Saura C, Yamashita T, et al; DESTINY-Breast01 Investigators. Trastuzumab deruxtecan in previously treated HER2-positive breast cancer. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:610-621. Doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1914510 Source

- Hurvitz S, Kim S-B, Chung W-P, et al. Trastuzumab deruxtecan (T-DXd; DS-8201a) versus trastuzumab emtansine (T-DM1) in patients (pts) with HER2+ metastatic breast cancer (mBC): Subgroup analyses from the randomized phase 3 study DESTINY-Breast03. Presented at 2021 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium; December 7-10, 2021;General Session, GS3-01. Source

- Li J, Huo X, Zhao F, et al. Association of cyclin-dependent kinases 4 and 6 inhibitors with survival in patients with hormone receptor-positive metastatic breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e2020312. Doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.20312 Source

- Harbeck N, Rastogi P, Martin M, et al. Adjuvant abemaciclib combined with endocrine therapy for high-risk early breast cancer: Updated efficacy and Ki-67 analysis from the monarchE study. Ann Oncol. 2021;32:1571-1581. Doi: 10.1016/j.annonc.2021.09.015 Source

- Prat A, Saura C, Pascual T, et al. Ribociclib plus letrozole versus chemotherapy for postmenopausal women with hormone receptor-positive, HER2- negative, luminal B breast cancer (CORALLEEN): An open-label, multicentre, randomised, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:33-43. Doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(19)30786-7 Source

What's your diagnosis?

Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.

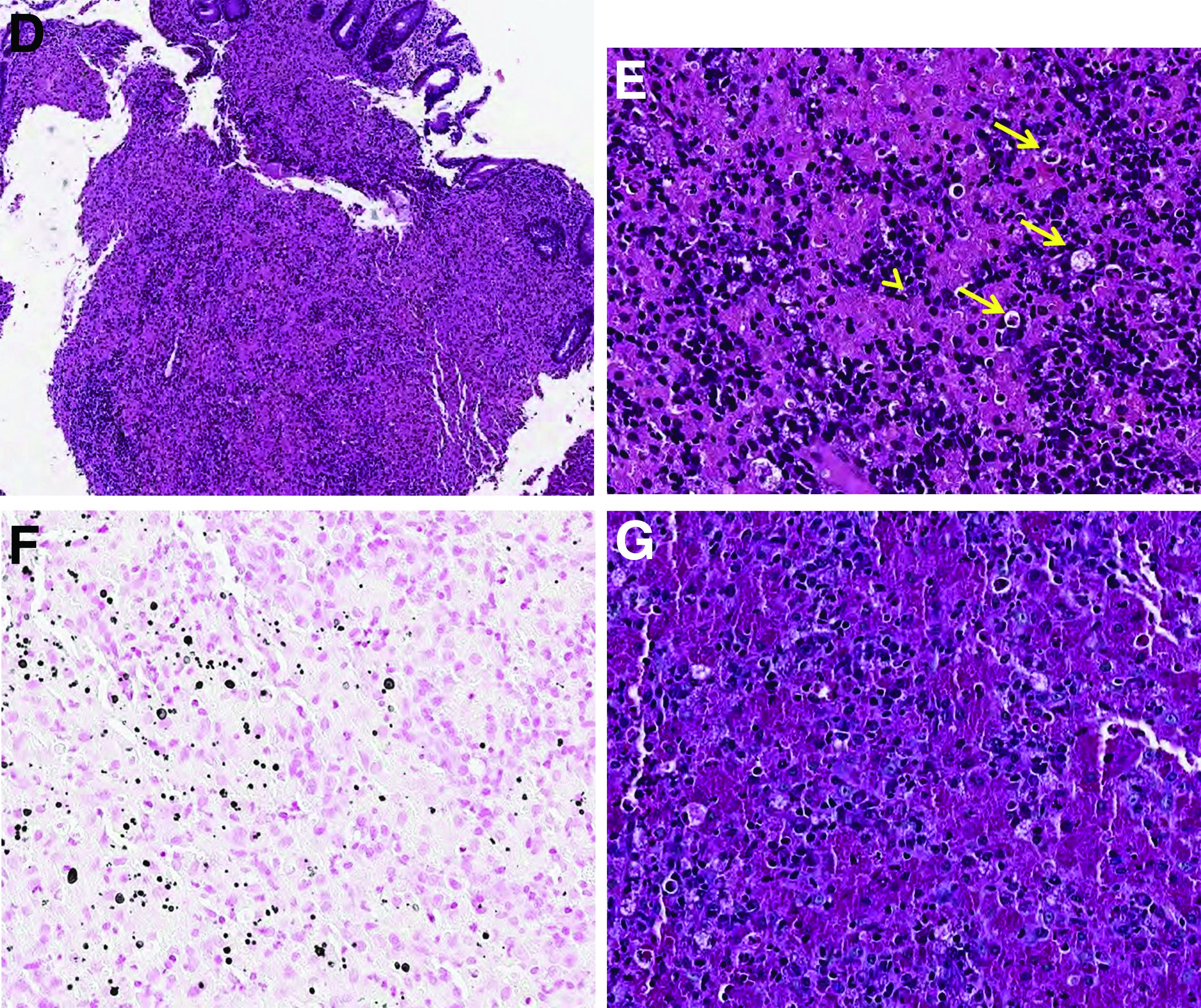

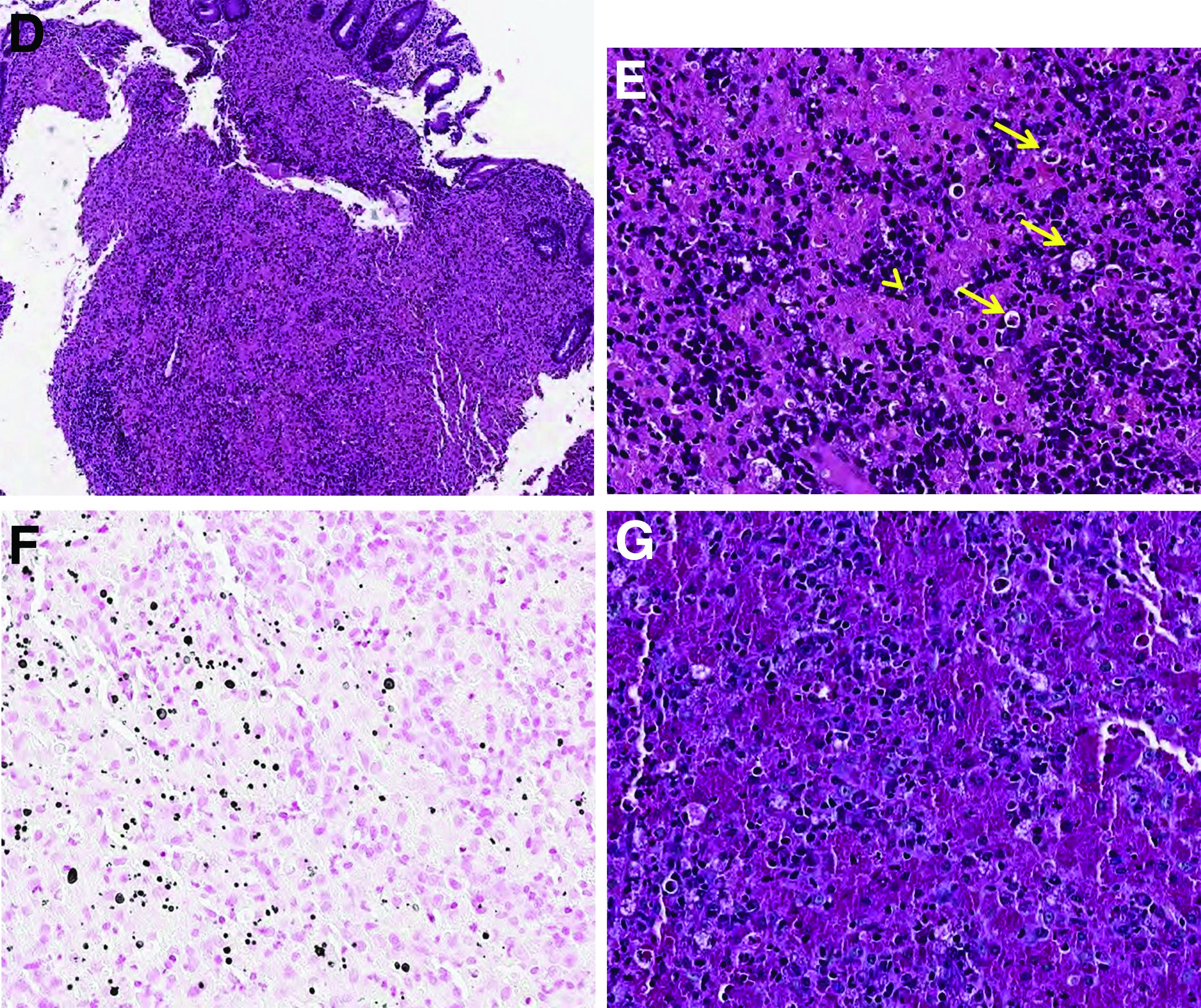

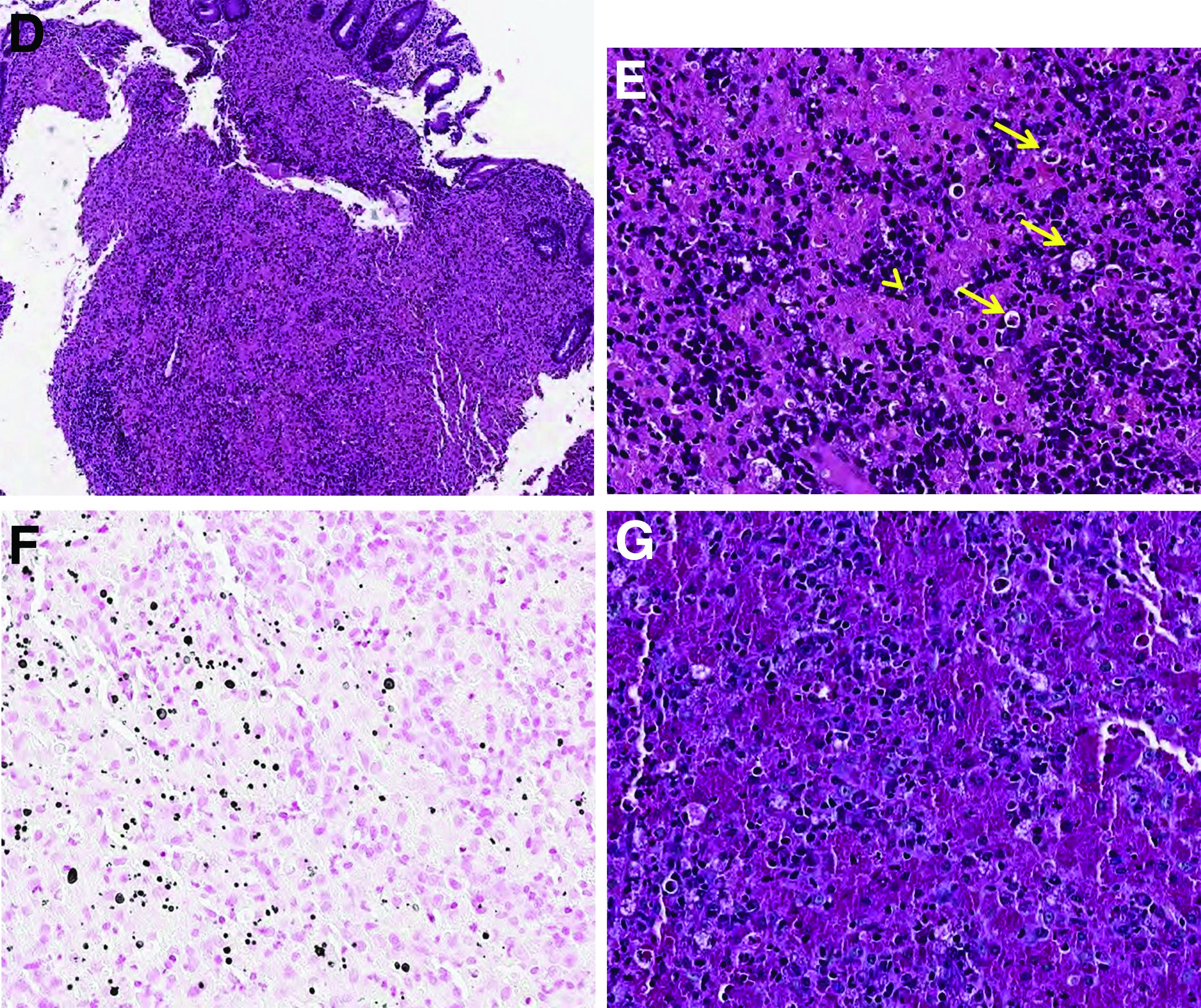

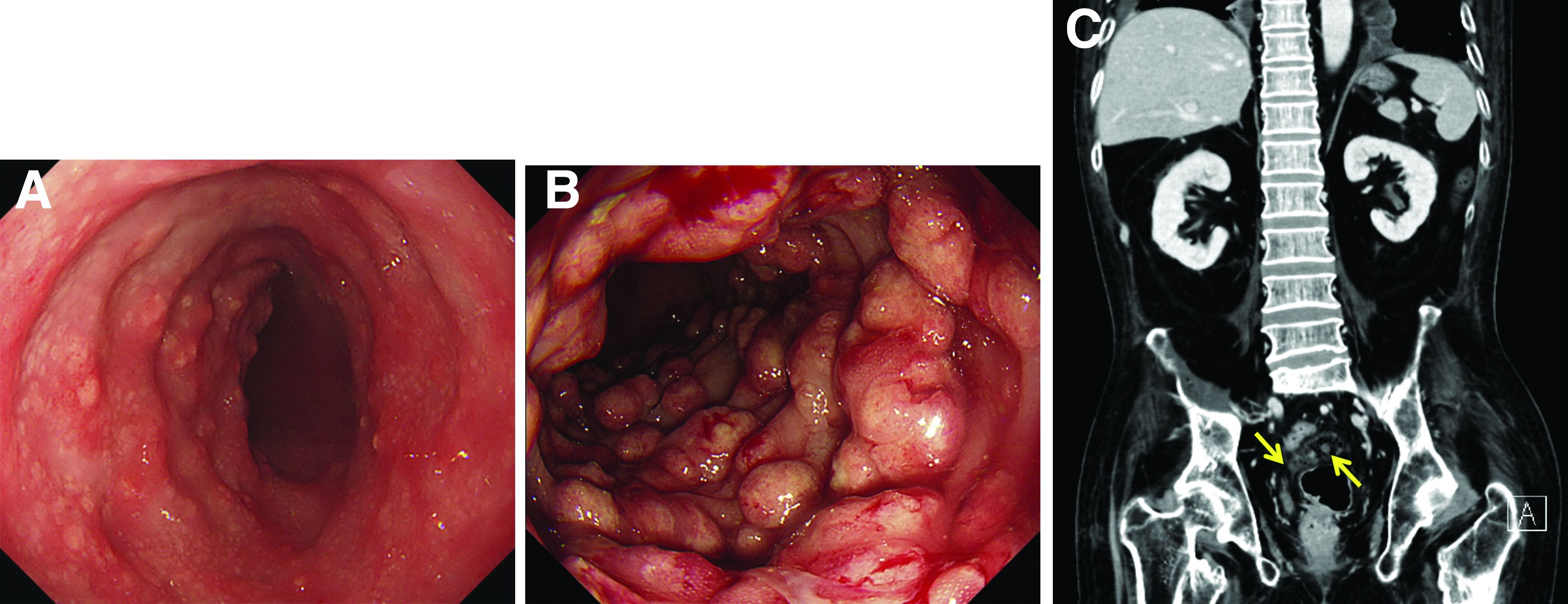

Histopathologic examination of the biopsy specimens revealed nodular mixed inflammatory cells and infiltration of the epithelioid histiocytes in lamina propria (Figure D; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 40×). The histiocytes showed foamy and eosinophilic cytoplasm (Figure E, arrow) and some of them had a targetoid appearance (Figure E, arrow head; stain: hematoxylin and eosin; original magnification 200×). Von Kossa stains highlighted the targetoid structures in the histiocytes (Figure F, Michaelis-Gutmann bodies). The granular cytoplasm of the histiocytes was positive on periodic acid-Schiff stain (Figure G). Based on these findings, the patient was diagnosed with colonic malakoplakia.

Malakoplakia is an uncommon, chronic, granulomatous inflammatory disease. It most commonly affects the urinary tract and gastrointestinal tract, but may occur at any anatomic site. Malakoplakia of the gastrointestinal tract are seen most frequently in the rectum, sigmoid, and right colon.1 It is diagnosed by the characteristic histologic feature of accumulated histiocytes with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm containing basophilic inclusions, consistent with Michaelis-Gutmann bodies. Although the exact etiology and pathogenesis of malakoplakia are unclear, it seems to originate from an acquired defect in the intracellular destruction of phagocytosed bacteria, usually associated with Escherichia coli, Klebsiella, and Mycobacterium.2 It can have various causes, such as immunosuppression, malignant neoplasms, systemic diseases, and genetic diseases. Clinical manifestation of colonic malakoplakia is diverse, ranging from asymptomatic to malaise, fever, abdominal pain, diarrhea, hematochezia, and intestinal obstruction. Granulomatous reaction of malakoplakia generates the endoscopic appearance of lesions, which ranges from plaques to nodules and yellow-brown masses. In the early stage, malakoplakia commonly presents as soft yellow to tan mucosal plaques endoscopically, as seen in our case (Figure A). As the disease progresses in the later stage, malakoplakia presents as raised, grey to tan polypoid lesions of various sizes with peripheral hyperemia and a central depressed area, as seen in our case (Figure B).3 Owing to this endoscopic morphology, colonic malakoplakia may be misdiagnosed as atypical lymphoma, familial adenomatous polyposis, and metastatic carcinoma. To date, the natural course of malakoplakia of the colon is unclear, and no guidelines for treatment, treatment methods, duration of treatment, or surveillance are currently available. However, treatment of malakoplakia is essential to reduce immunosuppression and includes antibiotics with intracellular action and choline agonists that replenish the decreased cyclic 3’, 5’-guanosine monophosphate levels. In summary, although malakoplakia of the colon is very rare, it should be considered in the differential diagnosis of polypoid colonic lesions, especially in immunocompromised or malnourished patients.

References

1. Cipolletta L et al. Gastrointest Endosc. 1995 Mar;41(3):255-8.

2. Berney T et al. Transpl Int. 1999;12(4):293-6.

3. Weinrach DM et al. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2004 Oct;128(10):e133-4.

Answer: Colonic Malakoplakia.