User login

Melanoma

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot in a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P<.05), followed by Hispanic (P<.05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P<.05), and Black (P<.05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P=.015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P<.001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P=.07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi:10.1023/a:1018432632528

- Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2004.05.005

- Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:704-708. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

- Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016)[published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2020.08.097

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot in a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P<.05), followed by Hispanic (P<.05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P<.05), and Black (P<.05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P=.015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P<.001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P=.07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

THE COMPARISON

A Acral lentiginous melanoma on the sole of the foot in a 30-year-old Black woman. The depth of the lesion was 2 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

B Nodular melanoma on the shoulder of a 63-year-old Hispanic woman. The depth of the lesion was 5.5 mm with a positive sentinel lymph node biopsy.

Melanoma occurs less frequently in individuals with darker skin types than in lighter skin types but is associated with higher rates of morbidity and mortality in this patient population.1-7 In the cases shown here (A and B), both patients had advanced melanomas with large primary lesions and lymph node metastases.

Epidemiology

A systematic review by Higgins et al6 reported the following on the epidemiology of melanomas in patients with skin of color:

- African Americans have deeper tumors at the time of diagnosis, in addition to increased rates of regionally advanced and distant disease. Lesions generally are located on the lower extremities and have an increased propensity for ulceration. Acral lentiginous melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype found in African American patients.6

- In Hispanic individuals, superficial spreading melanoma is the most common melanoma subtype. Lower extremity lesions are more common relative to White individuals. Hispanic individuals have the highest rate of oral cavity melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

- In Asian individuals, acral and subungual sites are most common. Specifically, Pacific Islanders have the highest proportion of mucosal melanomas across all ethnic groups.6

Key clinical features in people with darker skin tones

Melanomas are found more often on the palms, soles, nail units, oral cavity, and mucosae.6 The melanomas have the same clinical and dermoscopic features found in individuals with lighter skin tones.

Worth noting

Factors that may contribute to the diagnosis of more advanced melanomas in racial/ethnic minorities in the United States include:

- decreased access to health care based on lack of health insurance and low socioeconomic status,

- less awareness of the risk of melanoma among patients and health care providers because melanoma is less common in persons of color, and

- lesions found in areas less likely to be seen in screening examinations, such as the soles of the feet and the oral and genital mucosae.

Health disparity highlight

- In a large US study of 96,953 patients with a diagnosis of cutaneous melanoma from 1992 to 2009, the proportion of later-stage melanoma—stages II to IV—was greater in Black patients compared to White patients.7

- Based on this same data set, White patients had the longest survival time (P<.05), followed by Hispanic (P<.05), Asian American/Native American/Pacific Islander (P<.05), and Black (P<.05) patients, respectively.7

- In Miami-Dade County, one study of 1690 melanoma cases found that 48% of Black patients had regional or distant disease at presentation compared to 22% of White patients (P=.015).5 Analysis of multiple factors found that only race was a significant predictor for late-stage melanoma (P<.001). Black patients in this study were 3 times more likely than others to be diagnosed with melanoma at a late stage (P=.07).5

- Black patients in the United States are more likely to have a delayed time from diagnosis to definitive surgery even when controlled for type of health insurance and stage of diagnosis.8

Final thoughts

Efforts are needed to overcome these disparities by:

- educating patients with skin of color and their health care providers about the risks of advanced melanoma with the goal of prevention and earlier diagnosis;

- breaking down barriers to care caused by poverty, lack of health insurance, and systemic racism; and

- eliminating factors that lead to delays from diagnosis to definitive surgery.

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi:10.1023/a:1018432632528

- Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2004.05.005

- Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:704-708. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

- Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016)[published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2020.08.097

- Wu XC, Eide MJ, King J, et al. Racial and ethnic variations in incidence and survival of cutaneous melanoma in the United States, 1999-2006. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;65(5 suppl 1):S26-S37. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2001.05.034

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907-1914. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Cress RD, Holly EA. Incidence of cutaneous melanoma among non-Hispanic whites, Hispanics, Asians, and blacks: an analysis of California cancer registry data, 1988-93. Cancer Causes Control. 1997;8:246-252. doi:10.1023/a:1018432632528

- Hu S, Parker DF, Thomas AG, et al. Advanced presentation of melanoma in African Americans: the Miami-Dade County experience. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2004;51:1031-1032. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2004.05.005

- Hu S, Soza-Vento RM, Parker DF, et al. Comparison of stage at diagnosis of melanoma among Hispanic, black, and white patients in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:704-708. doi:10.1001/archderm.142.6.704

- Higgins S, Nazemi A, Feinstein S, et al. Clinical presentations of melanoma in African Americans, Hispanics, and Asians. Dermatol Surg. 2019;45:791-801. doi:10.1097/DSS.0000000000001759

- Dawes SM, Tsai S, Gittleman H, et al. Racial disparities in melanoma survival [published online July 28, 2016]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;75:983-991. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2016.06.006

- Qian Y, Johannet P, Sawyers A, et al. The ongoing racial disparities in melanoma: an analysis of the Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results database (1975-2016)[published online August 27, 2020]. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1585-1593. doi:10.1016/j. jaad.2020.08.097

Nevus of Ota: Does the 1064-nm Q-switched Nd:YAG laser work in Black patients?

SAN DIEGO – Using a , results from a small single-center study showed.

Nevus of Ota is a benign melanocytic lesion that presents as a unilateral blue-gray to blue-brown facial patch favoring the distribution of the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve. Among Asians, the prevalence of the condition among Asians is estimated to be between 0.03% and 1.113%, while the prevalence among Blacks population is estimated to be between 0.01% and 0.016%, Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said during a clinical abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

“Most existing literature describes the characteristics and treatment of Nevus of Ota based on Asian patients with skin types I-IV,” said Dr. Kubicki, a third-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston. “Special considerations are required when treating [Fitzpatrick skin types] V-VI, which is why it’s important to characterize these patients, to make sure they’re well represented in the literature.”

In what she said is the largest reported case series of its kind, Dr. Kubicki and colleagues identified eight Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI patients who underwent laser treatment for Nevus of Ota from 2016-2021. All were treated with the 1,064-nm Q‐switched Nd:YAG and on average, received 5.4 treatments at 2-10 month intervals. Fluence ranged from 1.8 to 2.4 J/cm2, and total pulse count ranged from 536.8 to 831.1. Two of these patients were additionally treated with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing with a mean of six treatments. Primary outcomes were based on improvement of before and after clinical photographs by three independent board-certified dermatologists, who used a 5-point visual analogue scale for grading.

The mean age of patients was 30.4 years and ranged from 9 months to 45 years. Six were females and two were males, two had Fitzpatrick skin type V, and six had Fitzpatrick skin type VI. Of the eight patients, six had blue-gray lesions, one patient had a dark brown lesion, and one patient had “a hybrid lesion that had blue-gray and brown discoloration,” Dr. Kubicki said.

After grading of the clinical photographs, patients demonstrated a mean improvement of 51%-75% at follow-up 5-56 weeks after treatment (a mean of 16.9 weeks). No long-term adverse events were encountered in either group, but three patients developed mild guttate hypopigmentation following laser treatment.

“Lesional color may contribute to outcome, and patients should be educated about the risk of guttate hypopigmentation,” Dr. Kubicki said. “More studies are needed to determine the optimal device and treatment settings in this population.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices at AllPhases Dermatology in Alexandria, Va., said that, while the study results impressed her, she speculated that the patients may require more treatments in the future. “What to look out for is the risk of rebound,” Dr. Onwudiwe said. “Because Nevus of Ota is a hamartomatous lesion, it’s very hard to treat, and sometimes it will come back. It will be nice to see how long this treatment can last. If you can use a combination therapy and have ... cases where you’re only needing a touch-up every so often, that’s still a win.”

Another session moderator, Eliot Battle, MD, CEO of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center in Washington, D.C., said that he wondered what histologic analysis following treatment might show, and if a biopsy after treatment would show “if we really got rid of the nevus, or if we are just cosmetically improving the appearance temporarily.”

Neither Dr. Kubicki nor Dr. Onwudiwe reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Battle disclosed that he conducts research for Cynosure. He has also received discounts from Cynosure, Cutera, Solta Medical, Lumenis, Be Inc., and Sciton.

SAN DIEGO – Using a , results from a small single-center study showed.

Nevus of Ota is a benign melanocytic lesion that presents as a unilateral blue-gray to blue-brown facial patch favoring the distribution of the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve. Among Asians, the prevalence of the condition among Asians is estimated to be between 0.03% and 1.113%, while the prevalence among Blacks population is estimated to be between 0.01% and 0.016%, Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said during a clinical abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

“Most existing literature describes the characteristics and treatment of Nevus of Ota based on Asian patients with skin types I-IV,” said Dr. Kubicki, a third-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston. “Special considerations are required when treating [Fitzpatrick skin types] V-VI, which is why it’s important to characterize these patients, to make sure they’re well represented in the literature.”

In what she said is the largest reported case series of its kind, Dr. Kubicki and colleagues identified eight Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI patients who underwent laser treatment for Nevus of Ota from 2016-2021. All were treated with the 1,064-nm Q‐switched Nd:YAG and on average, received 5.4 treatments at 2-10 month intervals. Fluence ranged from 1.8 to 2.4 J/cm2, and total pulse count ranged from 536.8 to 831.1. Two of these patients were additionally treated with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing with a mean of six treatments. Primary outcomes were based on improvement of before and after clinical photographs by three independent board-certified dermatologists, who used a 5-point visual analogue scale for grading.

The mean age of patients was 30.4 years and ranged from 9 months to 45 years. Six were females and two were males, two had Fitzpatrick skin type V, and six had Fitzpatrick skin type VI. Of the eight patients, six had blue-gray lesions, one patient had a dark brown lesion, and one patient had “a hybrid lesion that had blue-gray and brown discoloration,” Dr. Kubicki said.

After grading of the clinical photographs, patients demonstrated a mean improvement of 51%-75% at follow-up 5-56 weeks after treatment (a mean of 16.9 weeks). No long-term adverse events were encountered in either group, but three patients developed mild guttate hypopigmentation following laser treatment.

“Lesional color may contribute to outcome, and patients should be educated about the risk of guttate hypopigmentation,” Dr. Kubicki said. “More studies are needed to determine the optimal device and treatment settings in this population.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices at AllPhases Dermatology in Alexandria, Va., said that, while the study results impressed her, she speculated that the patients may require more treatments in the future. “What to look out for is the risk of rebound,” Dr. Onwudiwe said. “Because Nevus of Ota is a hamartomatous lesion, it’s very hard to treat, and sometimes it will come back. It will be nice to see how long this treatment can last. If you can use a combination therapy and have ... cases where you’re only needing a touch-up every so often, that’s still a win.”

Another session moderator, Eliot Battle, MD, CEO of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center in Washington, D.C., said that he wondered what histologic analysis following treatment might show, and if a biopsy after treatment would show “if we really got rid of the nevus, or if we are just cosmetically improving the appearance temporarily.”

Neither Dr. Kubicki nor Dr. Onwudiwe reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Battle disclosed that he conducts research for Cynosure. He has also received discounts from Cynosure, Cutera, Solta Medical, Lumenis, Be Inc., and Sciton.

SAN DIEGO – Using a , results from a small single-center study showed.

Nevus of Ota is a benign melanocytic lesion that presents as a unilateral blue-gray to blue-brown facial patch favoring the distribution of the first two branches of the trigeminal nerve. Among Asians, the prevalence of the condition among Asians is estimated to be between 0.03% and 1.113%, while the prevalence among Blacks population is estimated to be between 0.01% and 0.016%, Shelby L. Kubicki, MD, said during a clinical abstract session at the annual meeting of the American Society for Laser Medicine and Surgery.

“Most existing literature describes the characteristics and treatment of Nevus of Ota based on Asian patients with skin types I-IV,” said Dr. Kubicki, a third-year dermatology resident at the University of Texas Health Sciences Center/University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, both in Houston. “Special considerations are required when treating [Fitzpatrick skin types] V-VI, which is why it’s important to characterize these patients, to make sure they’re well represented in the literature.”

In what she said is the largest reported case series of its kind, Dr. Kubicki and colleagues identified eight Fitzpatrick skin type V or VI patients who underwent laser treatment for Nevus of Ota from 2016-2021. All were treated with the 1,064-nm Q‐switched Nd:YAG and on average, received 5.4 treatments at 2-10 month intervals. Fluence ranged from 1.8 to 2.4 J/cm2, and total pulse count ranged from 536.8 to 831.1. Two of these patients were additionally treated with 1,550-nm nonablative fractional resurfacing with a mean of six treatments. Primary outcomes were based on improvement of before and after clinical photographs by three independent board-certified dermatologists, who used a 5-point visual analogue scale for grading.

The mean age of patients was 30.4 years and ranged from 9 months to 45 years. Six were females and two were males, two had Fitzpatrick skin type V, and six had Fitzpatrick skin type VI. Of the eight patients, six had blue-gray lesions, one patient had a dark brown lesion, and one patient had “a hybrid lesion that had blue-gray and brown discoloration,” Dr. Kubicki said.

After grading of the clinical photographs, patients demonstrated a mean improvement of 51%-75% at follow-up 5-56 weeks after treatment (a mean of 16.9 weeks). No long-term adverse events were encountered in either group, but three patients developed mild guttate hypopigmentation following laser treatment.

“Lesional color may contribute to outcome, and patients should be educated about the risk of guttate hypopigmentation,” Dr. Kubicki said. “More studies are needed to determine the optimal device and treatment settings in this population.”

In an interview at the meeting, one of the session moderators, Oge Onwudiwe, MD, a dermatologist who practices at AllPhases Dermatology in Alexandria, Va., said that, while the study results impressed her, she speculated that the patients may require more treatments in the future. “What to look out for is the risk of rebound,” Dr. Onwudiwe said. “Because Nevus of Ota is a hamartomatous lesion, it’s very hard to treat, and sometimes it will come back. It will be nice to see how long this treatment can last. If you can use a combination therapy and have ... cases where you’re only needing a touch-up every so often, that’s still a win.”

Another session moderator, Eliot Battle, MD, CEO of Cultura Dermatology and Laser Center in Washington, D.C., said that he wondered what histologic analysis following treatment might show, and if a biopsy after treatment would show “if we really got rid of the nevus, or if we are just cosmetically improving the appearance temporarily.”

Neither Dr. Kubicki nor Dr. Onwudiwe reported having financial disclosures. Dr. Battle disclosed that he conducts research for Cynosure. He has also received discounts from Cynosure, Cutera, Solta Medical, Lumenis, Be Inc., and Sciton.

AT ASLMS 2022

Painful Fungating Perianal Mass

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

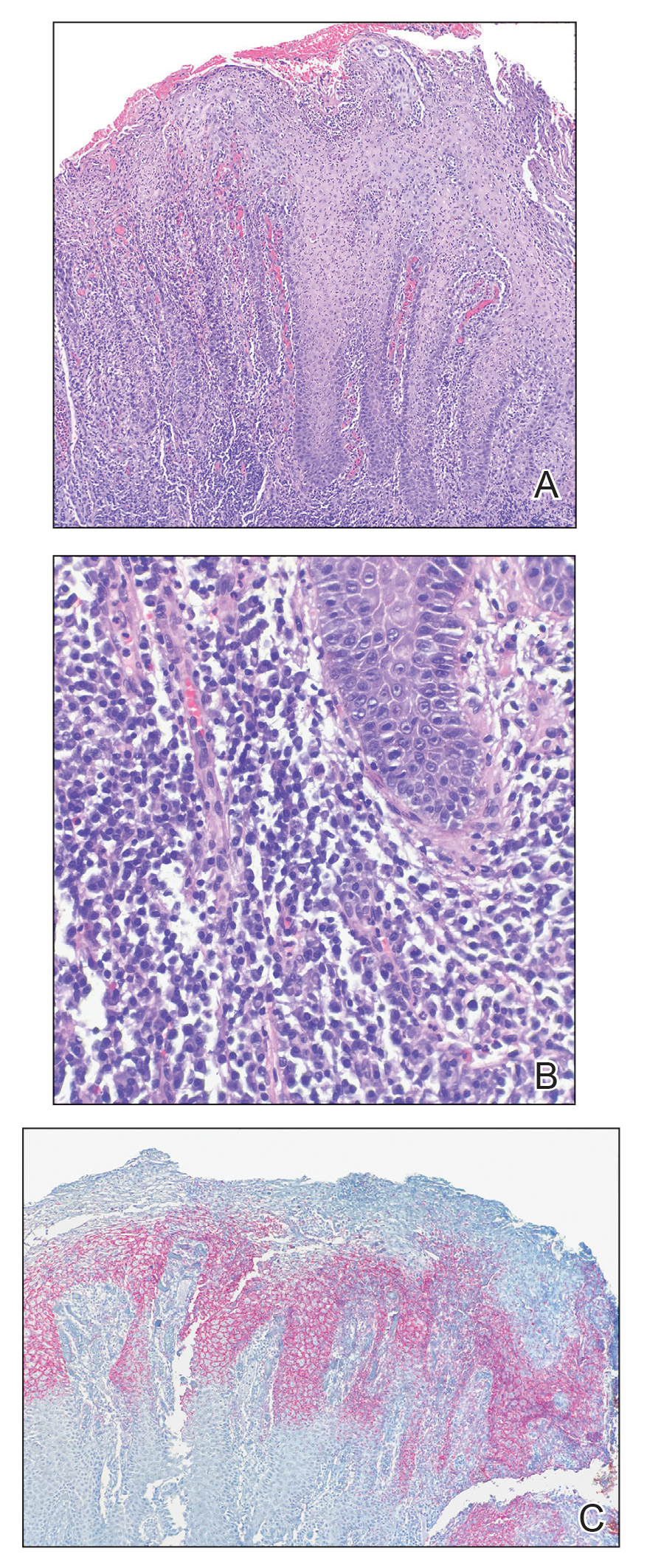

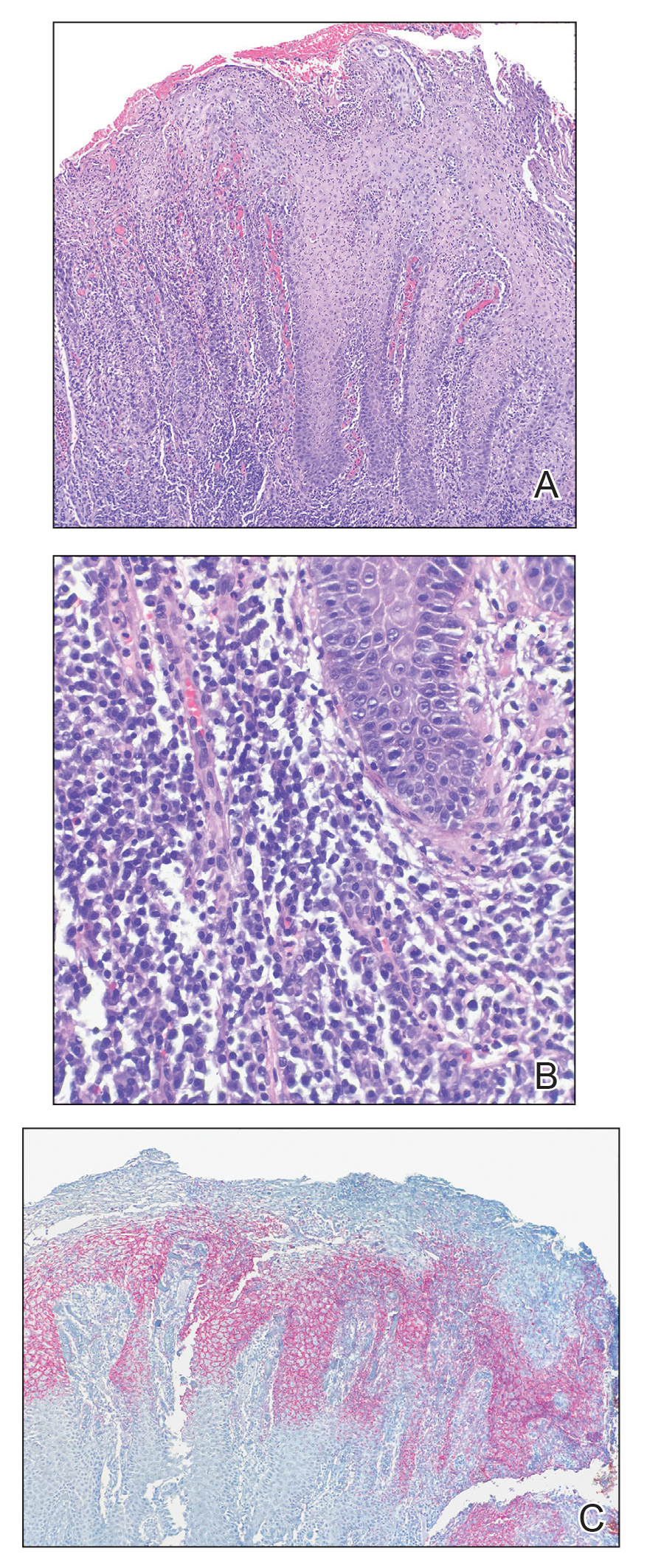

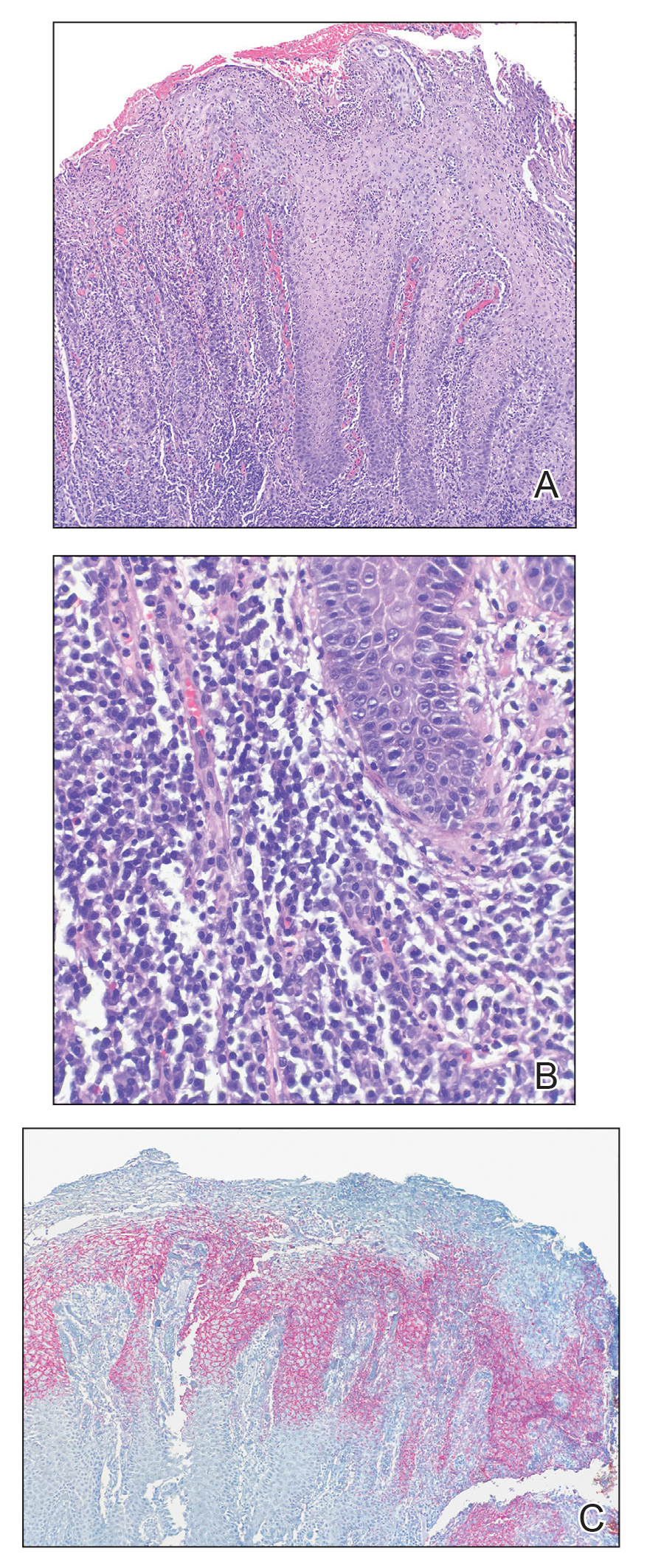

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

The Diagnosis: Condyloma Latum

A punch biopsy of the perianal mass revealed epidermal acanthosis with elongated slender rete ridges, scattered intraepidermal neutrophils, and a dense dermal inflammatory infiltrate (Figure, A) with a prominent plasma cell component (Figure, B). A treponemal immunohistochemical stain revealed numerous coiled spirochetes concentrated in the lower epidermis (Figure, C). Serologic test results including rapid plasma reagin (titer 1:1024) and Treponema pallidum antibody were reactive, confirming the diagnosis of secondary syphilis with condyloma latum. The patient was treated with intramuscular penicillin G with resolution of the lesion 2 weeks later.

Syphilis, a sexually transmitted infection caused by the spirochete T pallidum, reached historically low rates in the United States in the early 2000s due to the widespread use of penicillin and effective public health efforts.1 However, the rates of primary and secondary syphilis infections recently have markedly increased, resulting in the current epidemic of syphilis in the United States and Europe.1,2 Its wide variety of clinical and histopathologic manifestations make recognition challenging and lend it the moniker “the great imitator.”

Secondary syphilis results from the systemic spread of T pallidum and classically is characterized by the triad of a skin rash that frequently involves the palms and soles, mucosal ulceration such as condyloma latum, and lymphadenopathy.2,3 However, condyloma latum may represent the only manifestation of secondary syphilis in a subset of patients,4 as observed in our patient.

In the 2 months prior to diagnosis, our patient was evaluated at multiple emergency departments and primary care clinics, receiving diagnoses of condyloma acuminatum, genital herpes simplex virus, hemorrhoids, and suspicion for malignancy—entities that comprise the differential diagnosis for condyloma latum.2,5 Despite some degree of overlap in patient populations, risk factors, and presentations between these diagnostic considerations, recognition of certain clinical features, in addition to histopathologic evaluation, may facilitate navigation of this differential diagnosis.

Primary and secondary syphilis infections have been predominantly observed in men, mostly men who have sex with men and/or those who are infected with HIV.1 Condyloma acuminata, genital herpes simplex virus, and chancroid also are seen in younger individuals, more commonly in those with multiple sexual partners, but show a more even gender distribution and are not restricted to those partaking in anal intercourse. The clinical presentation of condyloma latum can be differentiated by its painless, flat, smooth, and commonly hypopigmented appearance, often with associated surface erosion and a gray exudate, in contrast to condyloma acuminatum, which typically presents as nontender, flesh-colored or hyperpigmented, exophytic papules that may coalesce into plaques.2,3,6 Genital herpes simplex virus infection presents with multiple small papulovesicular lesions with ulceration, most commonly on the tip or shaft of the penis, though perianal lesions may be seen in men who have sex with men.7 Similarly, chancroid presents with painful necrotizing genital ulcers most commonly on the penis, though perianal lesions also may be seen.8 Hemorrhoids classically are seen in middle-aged adults with a history of constipation, present with rectal bleeding, and may be associated with pain in the setting of thrombosis or ulceration.9 Finally, perianal squamous cell carcinoma primarily occurs in older adults, typically in the sixth decade of life. Verrucous carcinoma most commonly arises in the oropharynx or anogenital region in sites of chronic irritation and presents as a slow-growing exophytic mass. Classic squamous cell carcinoma most commonly occurs in association with human papillomavirus infection and presents with scaly erythematous papules or plaques.10

Our case highlighted the clinical difficulty in recognizing condyloma latum, as this lesion remained undiagnosed for 2 months, and our patient presumptively was treated for multiple perianal pathologies prior to a biopsy being performed. Due to the clinical similarity of various perianal lesions, the diagnosis of condyloma latum should be considered, and serologic studies should be performed in fitting clinical contexts, especially in light of recently rising rates of syphilis infection.1,2

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

- Ghanem KG, Ram S, Rice PA. The modern epidemic of syphilis. N Engl J Med. 2020;382:845-854.

- Tayal S, Shaban F, Dasgupta K, et al. A case of syphilitic anal condylomata lata mimicking malignancy. Int J Surg Case Rep. 2015; 17:69-71.

- Aung PP, Wimmer DB, Lester TR, et al. Perianal condylomata lata mimicking carcinoma. J Cutan Pathol. 2022;49:209-214.

- Pourang A, Fung MA, Tartar D, et al. Condyloma lata in secondary syphilis. JAAD Case Rep. 2021;10:18-21.

- Bruins FG, van Deudekom FJ, de Vries HJ. Syphilitic condylomata lata mimicking anogenital warts. BMJ. 2015;350:h1259.

- Leslie SW, Sajjad H, Kumar S. Genital warts. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2021.

- Groves MJ. Genital herpes: a review. Am Fam Physician. 2016; 93:928-934.

- Irizarry L, Velasquez J, Wray AA. Chancroid. In: StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing; 2022.

- Mounsey AL, Halladay J, Sadiq TS. Hemorrhoids. Am Fam Physician. 2011;84:204-210.

- Abbass MA, Valente MA. Premalignant and malignant perianal lesions. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2019;32:386-393.

A 21-year-old man presented to our clinic with rectal pain of 2 months’ duration that occurred in association with bowel movements and rectal bleeding in the setting of constipation. The patient’s symptoms had persisted despite multiple clinical encounters and treatment with sulfamethoxazole-trimethoprim, clotrimazole, valacyclovir, topical hydrocortisone and pramoxine, topical lidocaine, imiquimod, and psyllium seed. The patient denied engaging in receptive anal intercourse and had no notable medical or surgical history. Physical examination revealed a 6-cm hypopigmented fungating mass on the left gluteal cleft just external to the anal verge; there were no other abnormal findings. The patient denied any other systemic symptoms.

Supreme Court appears ready to overturn Roe

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

to the news outlet Politico.

The draft opinion, written by Justice Samuel Alito, outlines ways a presumed majority of the nine justices believes the 1973 ruling in Roe v. Wade was incorrect. If signed by a majority of the court, the ruling would eliminate the protections for abortion rights that Roe provided and give the 50 states the power to legislate abortion.

“We hold that Roe and Casey must be overruled,” Justice Alito writes in the draft. “It is time to heed the Constitution and return the issue of abortion to the people’s elected representatives.”

While a final ruling was not expected from the court until June, the leaked draft – a nearly unprecedented breach of the court’s internal workings – gives a strong signal of the court’s five most conservative members’ decisions. During oral arguments in the case in December, conservative justices appeared prepared to undo at least part of the country’s abortion protections.

President Joe Biden said his administration was already preparing for a potential ruling that struck down federal abortion protections.

The White House, he said in a statement, is working on a “response to the continued attack on abortion and reproductive rights, under a variety of possible outcomes in the cases pending before the Supreme Court. We will be ready when any ruling is issued.”

But if the draft opinion becomes final, he said the fight will move to the states.

“It will fall on our nation’s elected officials at all levels of government to protect a woman’s right to choose,” he said. “And it will fall on voters to elect pro-choice officials this November.”

With more pro-abortion rights members of Congress, it would be possible to pass federal legislation protecting abortion rights, “which I will work to pass and sign into law.”

Should the Alito draft become law, its first impact would be to allow a Mississippi law that bans abortions after 15 weeks to take effect.

But quickly after that, abortions would become illegal in many states. Several conservative-leaning states, mostly in the South and Midwest, have already passed laws severely restricting abortions well beyond what Roe allowed. Should Roe be overturned then, those laws would take effect without the threat of lengthy lawsuits or rulings from lower-court judges who have blocked them.

Nearly half of the states, mostly in the Northeast and West, would likely allow abortion to continue in some way. In fact, several states, including Colorado and Vermont, have already passed laws granting the right to an abortion into state law.

The leaked draft, however, is still a draft, meaning it remains possible Roe survives. Anthony Kreis, PhD, a professor of law at Georgia State University, says that could have been the point of whoever leaked the draft.

“It suggests to me that whoever leaked it knew that public outrage was the last resort to stopping the court from overturning Roe v. Wade and letting states ban all abortions,” Dr. Kreis said. “The danger that abortions won’t be legal in most of the country is very real.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

This article was updated 5/3/22.

Commentary: WHO, UNICEF warn about increased risk of measles outbreaks

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

The newly released global estimate is now 25 million children (2 million more than in 2020) missing scheduled vaccines. This continues to bode badly for multiple vaccine-preventable infections, but maybe the most for measles in 2022.

Specifically for measles vaccine, global two-dose coverage was only 71%. Coverage was less than 50% in 8 countries: Chad, Guinea, Samoa, North Korea, Central African Republic, Somalia, Angola, and South Sudan. These eight areas seem ripe for outbreaks this year and indeed Somalia is having an outbreak.

Overall, worldwide measles cases increased 79% in early 2022, compared with 2021. The top 10 countries for measles cases from November 2021 to April 2022, per the World Health Organization, include Nigeria, India, Soma Ethiopia, Pakistan, DR Congo, Afghanistan, Liberia, Cameroon, and Ivory Coast.

In the United States, we have been lucky so far with only 55 cases since the start of 2021. However, MMR two-dose coverage has dropped since the pandemic’s start. The list of U.S. areas with the lowest overall two-dose MMR coverage as of 2021 were D.C. (78.9%), Houston (93.7%), Idaho (86.5%), Wisconsin (87.2%), Maryland (87.6%), Georgia (88.5%), Kentucky (88.9%), Ohio (89.6%), and Minnesota (89.8%). Only 14 states had rates over the targeted 95% rate needed for community (herd) immunity against measles (MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2022;71:561-8).

Two bits of good news are that there seems to be some catch-up occurring in vaccine uptake overall (including MMR) and we now have two MMR suppliers in the United States since GlaxoSmithKline’s MMR was recently approved by the Food and Drug Administration for persons over 1 year of age. Let’s all redouble our efforts at adding to the catch-up efforts.

Christopher J. Harrison, MD, is professor, University of Missouri Kansas City School of Medicine, department of medicine, infectious diseases section, Kansas City. He has no financial conflicts of interest.

Clinical Edge Journal Scan Commentary: Atopic Dermatitis May 2022

- Dupilumab is a subcutaneous injection therapy that inhibits the interleukin 4-receptor alpha subunit. It was approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe AD in 2017 and has since been approved for children and adolescents down to 6 years of age. Ungar and colleagues studied the effects of dupilumab on SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in patients with moderate to severe AD. They previously found that dupilumab was associated with milder COVID-19 illness. In this study, they similarly found that dupilumab was associated with lower immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2, consistent with less severe COVID-19 illness. Future studies are needed to confirm these results. However, these results reassure that taking dupilumab does not pose any major harms in regard to COVID-19 outcomes.

- My patients with AD ask me on an almost daily basis about whether they should get vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2. I recommended that my patients get vaccinated, based on data from vaccine studies. However, there has been a dearth of data on the efficacy and safety of SARS-CoV-2 specifically in AD patients. Kridin and colleagues performed a population-based cohort study including 77,682 adults with AD, of which 58,582 patients had completed two doses of the BioNTech-Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. They found that patients with AD who received both vs no vaccine doses had significantly lower risk for COVID-19, hospitalization, and mortality. These are the best data to date in support of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with AD. Of note, there was no significant impact of immunosuppressive drugs on vaccine efficacy against COVID-19. However, previous studies in other immune-mediated disorders suggest that immunosuppressants may lower vaccine immune responses.1,2 Some authors have advocated for temporarily discontinuing immunosuppressive agents for 1-2 weeks before and after administering SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to make strong recommendations.

Numerous in utero and early-life risk factors for AD have been examined over the years. Maternal stress and depression have been considered as potential risk factors for AD in children.

- My research group showed a while back that depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum period was associated with higher likelihood of AD in children.3

- Kawaguchi and colleagues recently analyzed data from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study in Japan, including 8377 mother-child dyads where the child had not developed AD by the age of 1 year. They found that mothers with vs without psychological distress in both prenatal and postnatal periods or even only in the postnatal period had significantly increased risk of their children developing AD at 1-2 years of age. It seems prudent that mothers try to minimize stress during pregnancy and postpartum, though, understandably, this is not always feasible. Additionally, children of mothers who experience a lot of stress during pregnancy or postpartum may benefit from closer surveillance for the development of AD and other atopic diseases.

Additional References

1. Dayam RM, Law JC, Goetbebuer RL, et al. Accelerated waning of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with immune mediated inflammatory diseases. JCI Insight. 2022 (Apr 26). Doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.159721 Source

2. Medeiros-Ribeiro AC, Bonfiglioli KR, Domiciano DS, et al. Distinct impact of DMARD combination and monotherapy in immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:710-719. Doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221735 Source

3. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. Maternal depression and atopic dermatitis in American children and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2020;31:75-80. Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000548 Source

- Dupilumab is a subcutaneous injection therapy that inhibits the interleukin 4-receptor alpha subunit. It was approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe AD in 2017 and has since been approved for children and adolescents down to 6 years of age. Ungar and colleagues studied the effects of dupilumab on SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in patients with moderate to severe AD. They previously found that dupilumab was associated with milder COVID-19 illness. In this study, they similarly found that dupilumab was associated with lower immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2, consistent with less severe COVID-19 illness. Future studies are needed to confirm these results. However, these results reassure that taking dupilumab does not pose any major harms in regard to COVID-19 outcomes.

- My patients with AD ask me on an almost daily basis about whether they should get vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2. I recommended that my patients get vaccinated, based on data from vaccine studies. However, there has been a dearth of data on the efficacy and safety of SARS-CoV-2 specifically in AD patients. Kridin and colleagues performed a population-based cohort study including 77,682 adults with AD, of which 58,582 patients had completed two doses of the BioNTech-Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. They found that patients with AD who received both vs no vaccine doses had significantly lower risk for COVID-19, hospitalization, and mortality. These are the best data to date in support of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with AD. Of note, there was no significant impact of immunosuppressive drugs on vaccine efficacy against COVID-19. However, previous studies in other immune-mediated disorders suggest that immunosuppressants may lower vaccine immune responses.1,2 Some authors have advocated for temporarily discontinuing immunosuppressive agents for 1-2 weeks before and after administering SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to make strong recommendations.

Numerous in utero and early-life risk factors for AD have been examined over the years. Maternal stress and depression have been considered as potential risk factors for AD in children.

- My research group showed a while back that depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum period was associated with higher likelihood of AD in children.3

- Kawaguchi and colleagues recently analyzed data from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study in Japan, including 8377 mother-child dyads where the child had not developed AD by the age of 1 year. They found that mothers with vs without psychological distress in both prenatal and postnatal periods or even only in the postnatal period had significantly increased risk of their children developing AD at 1-2 years of age. It seems prudent that mothers try to minimize stress during pregnancy and postpartum, though, understandably, this is not always feasible. Additionally, children of mothers who experience a lot of stress during pregnancy or postpartum may benefit from closer surveillance for the development of AD and other atopic diseases.

Additional References

1. Dayam RM, Law JC, Goetbebuer RL, et al. Accelerated waning of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with immune mediated inflammatory diseases. JCI Insight. 2022 (Apr 26). Doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.159721 Source

2. Medeiros-Ribeiro AC, Bonfiglioli KR, Domiciano DS, et al. Distinct impact of DMARD combination and monotherapy in immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:710-719. Doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221735 Source

3. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. Maternal depression and atopic dermatitis in American children and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2020;31:75-80. Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000548 Source

- Dupilumab is a subcutaneous injection therapy that inhibits the interleukin 4-receptor alpha subunit. It was approved in the United States for the treatment of adults with moderate to severe AD in 2017 and has since been approved for children and adolescents down to 6 years of age. Ungar and colleagues studied the effects of dupilumab on SARS-CoV-2 antibody responses in patients with moderate to severe AD. They previously found that dupilumab was associated with milder COVID-19 illness. In this study, they similarly found that dupilumab was associated with lower immunoglobulin G (IgG) antibody levels to SARS-CoV-2, consistent with less severe COVID-19 illness. Future studies are needed to confirm these results. However, these results reassure that taking dupilumab does not pose any major harms in regard to COVID-19 outcomes.

- My patients with AD ask me on an almost daily basis about whether they should get vaccinated for SARS-CoV-2. I recommended that my patients get vaccinated, based on data from vaccine studies. However, there has been a dearth of data on the efficacy and safety of SARS-CoV-2 specifically in AD patients. Kridin and colleagues performed a population-based cohort study including 77,682 adults with AD, of which 58,582 patients had completed two doses of the BioNTech-Pfizer SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccine. They found that patients with AD who received both vs no vaccine doses had significantly lower risk for COVID-19, hospitalization, and mortality. These are the best data to date in support of SARS-CoV-2 vaccination in patients with AD. Of note, there was no significant impact of immunosuppressive drugs on vaccine efficacy against COVID-19. However, previous studies in other immune-mediated disorders suggest that immunosuppressants may lower vaccine immune responses.1,2 Some authors have advocated for temporarily discontinuing immunosuppressive agents for 1-2 weeks before and after administering SARS-CoV-2 vaccines. Currently, there is insufficient evidence to make strong recommendations.

Numerous in utero and early-life risk factors for AD have been examined over the years. Maternal stress and depression have been considered as potential risk factors for AD in children.

- My research group showed a while back that depression during pregnancy and in the postpartum period was associated with higher likelihood of AD in children.3

- Kawaguchi and colleagues recently analyzed data from the Tohoku Medical Megabank Project Birth and Three-Generation Cohort Study in Japan, including 8377 mother-child dyads where the child had not developed AD by the age of 1 year. They found that mothers with vs without psychological distress in both prenatal and postnatal periods or even only in the postnatal period had significantly increased risk of their children developing AD at 1-2 years of age. It seems prudent that mothers try to minimize stress during pregnancy and postpartum, though, understandably, this is not always feasible. Additionally, children of mothers who experience a lot of stress during pregnancy or postpartum may benefit from closer surveillance for the development of AD and other atopic diseases.

Additional References

1. Dayam RM, Law JC, Goetbebuer RL, et al. Accelerated waning of immunity to SARS-CoV-2 mRNA vaccines in patients with immune mediated inflammatory diseases. JCI Insight. 2022 (Apr 26). Doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.159721 Source

2. Medeiros-Ribeiro AC, Bonfiglioli KR, Domiciano DS, et al. Distinct impact of DMARD combination and monotherapy in immunogenicity of an inactivated SARS-CoV-2 vaccine in rheumatoid arthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2022;81:710-719. Doi: 10.1136/annrheumdis-2021-221735 Source

3. McKenzie C, Silverberg JI. Maternal depression and atopic dermatitis in American children and adolescents. Dermatitis. 2020;31:75-80. Doi: 10.1097/DER.0000000000000548 Source

Paxlovid doesn’t prevent infection in households, Pfizer says

Paxlovid works as a treatment for COVID-19 but not as a preventive measure, particularly if you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus through a household member who is infected, according to a new announcement from Pfizer.

In a clinical trial, the oral antiviral tablets were tested for postexposure prophylactic use, or tested for how well they prevented a coronavirus infection in people exposed to the virus. Paxlovid somewhat reduced the risk of infection, but the results weren’t statistically significant.

“We designed the clinical development program for Paxlovid to be comprehensive and ambitious with the aim of being able to help combat COVID-19 in a very broad population of patients,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the announcement.

“While we are disappointed in the outcome of this particular study, these results do not impact the strong efficacy and safety data we’ve observed in our earlier trial for the treatment of COVID-19 patients at high risk of developing severe illness,” he said.

The trial included nearly 3,000 adults who were living with someone who recently tested positive for COVID-19 and had symptoms. The people in the trial, who tested negative and didn’t have symptoms, were given either Paxlovid twice daily for 5 or 10 days or a placebo. The study recruitment began in September 2021 and was completed during the peak of the Omicron wave.

Those who took the 5-day course of Paxlovid were found to be 32% less likely to become infected than the placebo group. Those who took the 10-day treatment had a 37% risk reduction. But the results weren’t statistically significant and may have been because of chance.

“Traditionally, it’s been difficult to use small-molecule antivirals for true prophylaxis because the biology of treating infection is different from the biology of preventing infection,” Daniel Barouch, MD, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, told STAT News.

He also noted that the Omicron variant could have played a role.

“That hyperinfectiousness probably makes it more difficult to prevent infections,” Dr. Barouch said.

The safety data was consistent with that of previous studies, Pfizer said, which found that the treatment was about 90% effective at preventing hospitalization or death in COVID-19 patients with a high risk of severe illness if the pills were taken for 5 days soon after symptoms started.

Paxlovid is approved or authorized for conditional or emergency use in more than 60 countries to treat high-risk COVID-19 patients, Pfizer said. In the United States, the drug is authorized for emergency use for the treatment of mild to moderate COVID-19 in those aged 12 and older who face high risks for severe disease, hospitalization, or death.

The full study data will be released in coming months and submitted to a peer-reviewed publication, the company said. More details are on the ClinicalTrials.gov website (NCT05047601).

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Paxlovid works as a treatment for COVID-19 but not as a preventive measure, particularly if you’ve been exposed to the coronavirus through a household member who is infected, according to a new announcement from Pfizer.

In a clinical trial, the oral antiviral tablets were tested for postexposure prophylactic use, or tested for how well they prevented a coronavirus infection in people exposed to the virus. Paxlovid somewhat reduced the risk of infection, but the results weren’t statistically significant.

“We designed the clinical development program for Paxlovid to be comprehensive and ambitious with the aim of being able to help combat COVID-19 in a very broad population of patients,” Albert Bourla, PhD, Pfizer’s chairman and CEO, said in the announcement.

“While we are disappointed in the outcome of this particular study, these results do not impact the strong efficacy and safety data we’ve observed in our earlier trial for the treatment of COVID-19 patients at high risk of developing severe illness,” he said.

The trial included nearly 3,000 adults who were living with someone who recently tested positive for COVID-19 and had symptoms. The people in the trial, who tested negative and didn’t have symptoms, were given either Paxlovid twice daily for 5 or 10 days or a placebo. The study recruitment began in September 2021 and was completed during the peak of the Omicron wave.

Those who took the 5-day course of Paxlovid were found to be 32% less likely to become infected than the placebo group. Those who took the 10-day treatment had a 37% risk reduction. But the results weren’t statistically significant and may have been because of chance.

“Traditionally, it’s been difficult to use small-molecule antivirals for true prophylaxis because the biology of treating infection is different from the biology of preventing infection,” Daniel Barouch, MD, director of the Center for Virology and Vaccine Research at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, told STAT News.

He also noted that the Omicron variant could have played a role.

“That hyperinfectiousness probably makes it more difficult to prevent infections,” Dr. Barouch said.