User login

Reassessing benzodiazepines: What role should this medication class play in psychiatry?

Many psychiatrists have had the grim experience of a newly referred patient explaining that her (and it is most often “her”) primary care doctor has been prescribing lorazepam 8 mg per day or alprazolam 6 mg per day and is sending her to you for help with ongoing anxiety. For conscientious psychiatrists, this means the beginning of a long tapering process along with a great deal of reassuring of a patient who is terrified of feeling overwhelmed with anxiety. The same problem occurs with patients taking large doses of sedatives who are still unable to sleep.

Mark Olfson and coauthors quantified benzodiazepine use in the United States in 2008 using a large prescription database, and found that 5.2% of adults between 18 and 80 years old were taking these drugs.1 The percentage increased with age, to 8.7% of those 65-80 years, in whom 31% received long-term prescriptions from a psychiatrist. Benzodiazepine use was twice as prevalent in women, compared with men. This occurs despite peer-reviewed publications and articles in the popular press regarding the risks of long-term benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Fang-Yu Lin and coauthors documented a 2.23-fold higher risk of hip fracture in zolpidem users that increased with age; elderly users had a 21-fold higher incidence of fracture, compared with younger users, and were twice as likely to sustain a fracture than elderly nonusers.2

Rashona Thomas and Edid Ramos-Rivas reviewed the risks of benzodiazepines in older patients with insomnia and document the increase in serious adverse events such as falls, fractures, and cognitive and behavioral changes.3 Many patients have ongoing prescriptions that make discontinuation difficult, given the potential for withdrawal agitation, seizures, insomnia, nightmares and even psychosis.

Greta Bushnell and coauthors pointed to the problem of simultaneous prescribing of a new antidepressant with a benzodiazepine by 10% of doctors initiating antidepressants.4 Over 12% of this group of patients continued benzodiazepines long term, even though there was no difference in the response to antidepressant treatment at 6 months. Those with long-term benzodiazepine use were also more likely to have recent prescriptions for opiates.

A Finnish research team found that 34% of middle-aged and 55% of elderly people developed long-term use of benzodiazepines after an initial prescription.5 Those who became long-term users were more often older male receivers of social benefits, with psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse histories.

Kevin Xu and coauthors reviewed a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset from 1999 to 2015 with follow-up on over 5,000 individuals in that period.6 They found doubling of all-cause mortality in users of benzodiazepines with or without accompanying use of opiates, a statistically significant increase.

Perhaps most alarming is the increased risk for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis in users of benzodiazepines. Two separate studies (Billoti de Gage and colleagues and Ettcheto and colleagues7,8) provided reviews of evidence for the relationship between use of benzodiazepines and development of dementia, and repeated warnings about close monitoring of patients and the need for alternative treatments for anxiety and insomnia in the elderly.

Be alert to underlying issues

Overburdened primary practitioners faced with complaints about sleep and anxiety understandably turn to medication rather than taking time to discuss the reasons for these problems or to describe nonmedication approaches to relief of symptoms. Even insured patients may have very limited options for “covered” psychiatric consultation, as many competent psychiatrists have moved to a cash-only system. It is easier to renew prescriptions than to counsel patients or refer them, and many primary care practitioners have limited experience with diagnosing causes of anxiety and insomnia, much less alternative medication approaches.

Psychiatrists should be aware of the frequency of underlying mood disorders that include sleep and anxiety as prominent symptoms; in fact, these symptoms are often what motivates patients to pursue treatment. It is critical to obtain not only a personal history of symptoms beginning in childhood up to the present, but also a family history of mood and anxiety problems. Mood dysregulation disorders are highly hereditary and a family history of mania or psychosis should raise concern about the cause of symptoms in one’s patient. A strong personal and/or family history of alcohol abuse and dependence may cover underlying undiagnosed mood dysregulation. Primary care physicians may not recognize mood dysregulation unless a patient is clearly manic or psychotic.

There is a cohort of patients who do well on antidepressant medication, but anorgasmia, fatigue, and emotional blunting are common side effects that affect compliance. When patients have unexpected responses to SSRI medications such as euphoria, agitation, anxiety, insomnia, and more prominent mood swings, primary care physicians may add a benzodiazepine, expecting the problem to abate with time. Unfortunately, this often leads to ongoing use of benzodiazepines, since attempts to stop them causes withdrawal effects that are indistinguishable from the original anxiety symptoms.

Most psychiatrists are aware that some patients need mood stabilization rather than mood elevation to maintain an adequate baseline mood. Lithium, anticonvulsants, and second-generation antipsychotics may be effective without adding antidepressant medication. Managing dosing and side effects requires time for follow-up visits with patients after initiating treatment but leads to more stability and better outcomes.

Benzodiazepines are appropriate and helpful in situations that cause transient anxiety and with patients who have done poorly with other options. Intermittent use is key to avoiding tolerance and inevitable dose increases. Some individuals can take low daily doses that are harmless, though these likely only prevent withdrawal rather than preventing anxiety. The placebo effect of taking a pill is powerful. And some patients take more doses than they admit to. Most practitioners have heard stories about the alprazolam that was accidentally spilled into the sink or the prescription bottle of diazepam that was lost or the lorazepam supply that was stolen by the babysitter.

These concepts are illustrated in case examples below.

Case one

Ms. A, a 55-year-old married female business administrator, admitted to using zolpidem at 40 mg per night for the past several months. She began with the typical dose of 10 mg at bedtime prescribed by her internist, but after several weeks, needed an additional 10 mg at 2 a.m. to stay asleep. As weeks passed, she found that she needed an additional 20 mg when she awoke at 2 a.m. Within months, she needed 20 mg to initiate sleep and 20 mg to maintain sleep. She obtained extra zolpidem from her gynecologist and came for consultation when refill requests were refused.

Ms. A had a family history of high anxiety in her mother and depressed mood in multiple paternal relatives, including her father. She had trouble sleeping beginning in adolescence, significant premenstrual dysphoria, and postpartum depression that led to a prescription for sertraline. Instead of feeling better, Ms. A remembers being agitated and unable to sleep, so she stopped it. Ms. A was now perimenopausal, and insomnia was worse. She had gradually increased wine consumption to a bottle of wine each night after work to “settle down.” This allowed her to fall asleep, but she inevitably awoke within 4 hours. Her internist noted an elevation in ALT and asked Ms. A about alcohol consumption. She was alarmed and cut back to one glass of wine per night but again couldn’t sleep. Her internist started zolpidem at that point.

The psychiatrist explained the concepts of tolerance and addiction and a plan to slowly taper off zolpidem while using quetiapine for sleep. She decreased to 20 mg of zolpidem at bedtime with quetiapine 50 mg and was able to stay asleep. After 3 weeks, Ms. A took zolpidem 10 mg at bedtime with quetiapine 75 mg and again, was able to fall asleep and stay asleep. After another 3 weeks, she increased quetiapine to 100 mg and stopped zolpidem without difficulty. This dose of quetiapine has continued to work well without significant side effects.

Case two

Ms. B, a 70-year-old married housewife, was referred for help with longstanding anxiety when her primary care doctor recognized that lorazepam, initially helpful at 1 mg twice daily, had required titration to 2 mg three times daily. Ms. B was preoccupied with having lorazepam on hand and never missed a dose. She had little interest in activities beyond her home, rarely socialized, and had fallen twice. She napped for 2 hours each afternoon, and sometimes had trouble staying asleep through the night.

Ms. B was reluctant to talk about her childhood history of hostility and undermining by her mother, who clearly preferred her older brother and was competitive with Ms. B. Her father traveled for work during the week and had little time for her. Ms. B had always seen herself as stupid and unlovable, which interfered with making friends. She attended college for 1 year but dropped out to marry her husband. He was also anxious and had difficulty socializing, but they found reassurance in each other. Their only child, a son in his 40s, was estranged from them, having married a woman who disliked Ms. B. Ms. B felt hopeless about developing a relationship with her grandchildren who were rarely allowed to visit. Despite her initial shame in talking about these painful problems, Ms. B realized that she felt better and scheduled monthly visits to check in.

Ms. B understood the risks of using lorazepam and wanted to stop it but was terrified of becoming anxious again. We set up a very slow tapering schedule that lowered her total dose by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks. At the same time, she began escitalopram which was effective at 20 mg. Ms. B noted that she no longer felt anxious upon awakening but was still afraid to miss a dose of lorazepam. As she felt more confident and alert, Ms. B joined a painting class at a local community center and was gratified to find that she was good at working with watercolors. She invited her neighbors to come for dinner and was surprised at how friendly and open they were. Once she had tapered to 1 mg twice daily, Ms. B began walking for exercise as she now had enough energy that it felt good to move around. After 6 months, she was completely off lorazepam, and very grateful to have discovered her capacity to improve her pleasure in life.

Case three

Ms. C, a 48-year-old attorney was referred for help with anxiety and distress in the face of separation from her husband who had admitted to an affair after she heard him talking to his girlfriend from their basement. She was unsure whether she wanted to save the marriage or end it and was horrified at the thought of dating. She had never felt especially anxious or depressed and had a supportive circle of close friends. She was uncharacteristically unable to concentrate long enough to consider her options because of anxiety.

A dose of clonazepam 0.5 mg allowed her to stay alert but calm enough to reflect on her feelings. She used it intermittently over several months and maintained regular individual psychotherapy sessions that allowed her to review the situation thoroughly. On her psychiatrist’s recommendation, she contacted a colleague to represent her if she decided to initiate divorce proceedings. She attempted to engage her husband in marital therapy, and his reluctance made it clear to her that she could no longer trust him. Ms. C offered him the option of a dissolution if he was willing to cooperate, or to sue for divorce if not. Once Ms. C regained her confidence and recognized that she would survive this emotionally fraught situation, she no longer needed clonazepam.

Summary

The risks, which include cognitive slowing, falls and fractures, and withdrawal phenomena when abruptly stopped, make this class dangerous for all patients but particularly the elderly. Benzodiazepines are nonetheless useful medications for patients able to use them intermittently, whether on an alternating basis with other medications (for example, quetiapine alternating with clonazepam for chronic insomnia) or because symptoms of anxiety are intermittent. Psychiatrists treating tolerant patients should be familiar with the approach of tapering slowly while introducing more appropriate medications at adequate doses to manage symptoms.

Dr. Kaplan is training and supervising psychoanalyst at the Cincinnati Psychoanalytic Institute and volunteer professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati. The author reported no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Olfson M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;72(2):136-42. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763.

2. Lin FY et al. Sleep. 2014 Apr 1;37(4):673-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3566.

3. Thomas R and Ramos-Rivas E. Psychiatr Ann. 2018;48(6):266-70. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20180513-01.

4. Bushnell GA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;74(7):747-55. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1273.

5. Taipale H et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019029. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19029.

6. Xu KY et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028557. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28557.

7. Billioti de Gage S et al. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205.

8. Ettcheto M et al. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Jan 8;11:344. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00344.

Many psychiatrists have had the grim experience of a newly referred patient explaining that her (and it is most often “her”) primary care doctor has been prescribing lorazepam 8 mg per day or alprazolam 6 mg per day and is sending her to you for help with ongoing anxiety. For conscientious psychiatrists, this means the beginning of a long tapering process along with a great deal of reassuring of a patient who is terrified of feeling overwhelmed with anxiety. The same problem occurs with patients taking large doses of sedatives who are still unable to sleep.

Mark Olfson and coauthors quantified benzodiazepine use in the United States in 2008 using a large prescription database, and found that 5.2% of adults between 18 and 80 years old were taking these drugs.1 The percentage increased with age, to 8.7% of those 65-80 years, in whom 31% received long-term prescriptions from a psychiatrist. Benzodiazepine use was twice as prevalent in women, compared with men. This occurs despite peer-reviewed publications and articles in the popular press regarding the risks of long-term benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Fang-Yu Lin and coauthors documented a 2.23-fold higher risk of hip fracture in zolpidem users that increased with age; elderly users had a 21-fold higher incidence of fracture, compared with younger users, and were twice as likely to sustain a fracture than elderly nonusers.2

Rashona Thomas and Edid Ramos-Rivas reviewed the risks of benzodiazepines in older patients with insomnia and document the increase in serious adverse events such as falls, fractures, and cognitive and behavioral changes.3 Many patients have ongoing prescriptions that make discontinuation difficult, given the potential for withdrawal agitation, seizures, insomnia, nightmares and even psychosis.

Greta Bushnell and coauthors pointed to the problem of simultaneous prescribing of a new antidepressant with a benzodiazepine by 10% of doctors initiating antidepressants.4 Over 12% of this group of patients continued benzodiazepines long term, even though there was no difference in the response to antidepressant treatment at 6 months. Those with long-term benzodiazepine use were also more likely to have recent prescriptions for opiates.

A Finnish research team found that 34% of middle-aged and 55% of elderly people developed long-term use of benzodiazepines after an initial prescription.5 Those who became long-term users were more often older male receivers of social benefits, with psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse histories.

Kevin Xu and coauthors reviewed a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset from 1999 to 2015 with follow-up on over 5,000 individuals in that period.6 They found doubling of all-cause mortality in users of benzodiazepines with or without accompanying use of opiates, a statistically significant increase.

Perhaps most alarming is the increased risk for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis in users of benzodiazepines. Two separate studies (Billoti de Gage and colleagues and Ettcheto and colleagues7,8) provided reviews of evidence for the relationship between use of benzodiazepines and development of dementia, and repeated warnings about close monitoring of patients and the need for alternative treatments for anxiety and insomnia in the elderly.

Be alert to underlying issues

Overburdened primary practitioners faced with complaints about sleep and anxiety understandably turn to medication rather than taking time to discuss the reasons for these problems or to describe nonmedication approaches to relief of symptoms. Even insured patients may have very limited options for “covered” psychiatric consultation, as many competent psychiatrists have moved to a cash-only system. It is easier to renew prescriptions than to counsel patients or refer them, and many primary care practitioners have limited experience with diagnosing causes of anxiety and insomnia, much less alternative medication approaches.

Psychiatrists should be aware of the frequency of underlying mood disorders that include sleep and anxiety as prominent symptoms; in fact, these symptoms are often what motivates patients to pursue treatment. It is critical to obtain not only a personal history of symptoms beginning in childhood up to the present, but also a family history of mood and anxiety problems. Mood dysregulation disorders are highly hereditary and a family history of mania or psychosis should raise concern about the cause of symptoms in one’s patient. A strong personal and/or family history of alcohol abuse and dependence may cover underlying undiagnosed mood dysregulation. Primary care physicians may not recognize mood dysregulation unless a patient is clearly manic or psychotic.

There is a cohort of patients who do well on antidepressant medication, but anorgasmia, fatigue, and emotional blunting are common side effects that affect compliance. When patients have unexpected responses to SSRI medications such as euphoria, agitation, anxiety, insomnia, and more prominent mood swings, primary care physicians may add a benzodiazepine, expecting the problem to abate with time. Unfortunately, this often leads to ongoing use of benzodiazepines, since attempts to stop them causes withdrawal effects that are indistinguishable from the original anxiety symptoms.

Most psychiatrists are aware that some patients need mood stabilization rather than mood elevation to maintain an adequate baseline mood. Lithium, anticonvulsants, and second-generation antipsychotics may be effective without adding antidepressant medication. Managing dosing and side effects requires time for follow-up visits with patients after initiating treatment but leads to more stability and better outcomes.

Benzodiazepines are appropriate and helpful in situations that cause transient anxiety and with patients who have done poorly with other options. Intermittent use is key to avoiding tolerance and inevitable dose increases. Some individuals can take low daily doses that are harmless, though these likely only prevent withdrawal rather than preventing anxiety. The placebo effect of taking a pill is powerful. And some patients take more doses than they admit to. Most practitioners have heard stories about the alprazolam that was accidentally spilled into the sink or the prescription bottle of diazepam that was lost or the lorazepam supply that was stolen by the babysitter.

These concepts are illustrated in case examples below.

Case one

Ms. A, a 55-year-old married female business administrator, admitted to using zolpidem at 40 mg per night for the past several months. She began with the typical dose of 10 mg at bedtime prescribed by her internist, but after several weeks, needed an additional 10 mg at 2 a.m. to stay asleep. As weeks passed, she found that she needed an additional 20 mg when she awoke at 2 a.m. Within months, she needed 20 mg to initiate sleep and 20 mg to maintain sleep. She obtained extra zolpidem from her gynecologist and came for consultation when refill requests were refused.

Ms. A had a family history of high anxiety in her mother and depressed mood in multiple paternal relatives, including her father. She had trouble sleeping beginning in adolescence, significant premenstrual dysphoria, and postpartum depression that led to a prescription for sertraline. Instead of feeling better, Ms. A remembers being agitated and unable to sleep, so she stopped it. Ms. A was now perimenopausal, and insomnia was worse. She had gradually increased wine consumption to a bottle of wine each night after work to “settle down.” This allowed her to fall asleep, but she inevitably awoke within 4 hours. Her internist noted an elevation in ALT and asked Ms. A about alcohol consumption. She was alarmed and cut back to one glass of wine per night but again couldn’t sleep. Her internist started zolpidem at that point.

The psychiatrist explained the concepts of tolerance and addiction and a plan to slowly taper off zolpidem while using quetiapine for sleep. She decreased to 20 mg of zolpidem at bedtime with quetiapine 50 mg and was able to stay asleep. After 3 weeks, Ms. A took zolpidem 10 mg at bedtime with quetiapine 75 mg and again, was able to fall asleep and stay asleep. After another 3 weeks, she increased quetiapine to 100 mg and stopped zolpidem without difficulty. This dose of quetiapine has continued to work well without significant side effects.

Case two

Ms. B, a 70-year-old married housewife, was referred for help with longstanding anxiety when her primary care doctor recognized that lorazepam, initially helpful at 1 mg twice daily, had required titration to 2 mg three times daily. Ms. B was preoccupied with having lorazepam on hand and never missed a dose. She had little interest in activities beyond her home, rarely socialized, and had fallen twice. She napped for 2 hours each afternoon, and sometimes had trouble staying asleep through the night.

Ms. B was reluctant to talk about her childhood history of hostility and undermining by her mother, who clearly preferred her older brother and was competitive with Ms. B. Her father traveled for work during the week and had little time for her. Ms. B had always seen herself as stupid and unlovable, which interfered with making friends. She attended college for 1 year but dropped out to marry her husband. He was also anxious and had difficulty socializing, but they found reassurance in each other. Their only child, a son in his 40s, was estranged from them, having married a woman who disliked Ms. B. Ms. B felt hopeless about developing a relationship with her grandchildren who were rarely allowed to visit. Despite her initial shame in talking about these painful problems, Ms. B realized that she felt better and scheduled monthly visits to check in.

Ms. B understood the risks of using lorazepam and wanted to stop it but was terrified of becoming anxious again. We set up a very slow tapering schedule that lowered her total dose by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks. At the same time, she began escitalopram which was effective at 20 mg. Ms. B noted that she no longer felt anxious upon awakening but was still afraid to miss a dose of lorazepam. As she felt more confident and alert, Ms. B joined a painting class at a local community center and was gratified to find that she was good at working with watercolors. She invited her neighbors to come for dinner and was surprised at how friendly and open they were. Once she had tapered to 1 mg twice daily, Ms. B began walking for exercise as she now had enough energy that it felt good to move around. After 6 months, she was completely off lorazepam, and very grateful to have discovered her capacity to improve her pleasure in life.

Case three

Ms. C, a 48-year-old attorney was referred for help with anxiety and distress in the face of separation from her husband who had admitted to an affair after she heard him talking to his girlfriend from their basement. She was unsure whether she wanted to save the marriage or end it and was horrified at the thought of dating. She had never felt especially anxious or depressed and had a supportive circle of close friends. She was uncharacteristically unable to concentrate long enough to consider her options because of anxiety.

A dose of clonazepam 0.5 mg allowed her to stay alert but calm enough to reflect on her feelings. She used it intermittently over several months and maintained regular individual psychotherapy sessions that allowed her to review the situation thoroughly. On her psychiatrist’s recommendation, she contacted a colleague to represent her if she decided to initiate divorce proceedings. She attempted to engage her husband in marital therapy, and his reluctance made it clear to her that she could no longer trust him. Ms. C offered him the option of a dissolution if he was willing to cooperate, or to sue for divorce if not. Once Ms. C regained her confidence and recognized that she would survive this emotionally fraught situation, she no longer needed clonazepam.

Summary

The risks, which include cognitive slowing, falls and fractures, and withdrawal phenomena when abruptly stopped, make this class dangerous for all patients but particularly the elderly. Benzodiazepines are nonetheless useful medications for patients able to use them intermittently, whether on an alternating basis with other medications (for example, quetiapine alternating with clonazepam for chronic insomnia) or because symptoms of anxiety are intermittent. Psychiatrists treating tolerant patients should be familiar with the approach of tapering slowly while introducing more appropriate medications at adequate doses to manage symptoms.

Dr. Kaplan is training and supervising psychoanalyst at the Cincinnati Psychoanalytic Institute and volunteer professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati. The author reported no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Olfson M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;72(2):136-42. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763.

2. Lin FY et al. Sleep. 2014 Apr 1;37(4):673-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3566.

3. Thomas R and Ramos-Rivas E. Psychiatr Ann. 2018;48(6):266-70. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20180513-01.

4. Bushnell GA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;74(7):747-55. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1273.

5. Taipale H et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019029. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19029.

6. Xu KY et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028557. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28557.

7. Billioti de Gage S et al. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205.

8. Ettcheto M et al. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Jan 8;11:344. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00344.

Many psychiatrists have had the grim experience of a newly referred patient explaining that her (and it is most often “her”) primary care doctor has been prescribing lorazepam 8 mg per day or alprazolam 6 mg per day and is sending her to you for help with ongoing anxiety. For conscientious psychiatrists, this means the beginning of a long tapering process along with a great deal of reassuring of a patient who is terrified of feeling overwhelmed with anxiety. The same problem occurs with patients taking large doses of sedatives who are still unable to sleep.

Mark Olfson and coauthors quantified benzodiazepine use in the United States in 2008 using a large prescription database, and found that 5.2% of adults between 18 and 80 years old were taking these drugs.1 The percentage increased with age, to 8.7% of those 65-80 years, in whom 31% received long-term prescriptions from a psychiatrist. Benzodiazepine use was twice as prevalent in women, compared with men. This occurs despite peer-reviewed publications and articles in the popular press regarding the risks of long-term benzodiazepine use in the elderly. Fang-Yu Lin and coauthors documented a 2.23-fold higher risk of hip fracture in zolpidem users that increased with age; elderly users had a 21-fold higher incidence of fracture, compared with younger users, and were twice as likely to sustain a fracture than elderly nonusers.2

Rashona Thomas and Edid Ramos-Rivas reviewed the risks of benzodiazepines in older patients with insomnia and document the increase in serious adverse events such as falls, fractures, and cognitive and behavioral changes.3 Many patients have ongoing prescriptions that make discontinuation difficult, given the potential for withdrawal agitation, seizures, insomnia, nightmares and even psychosis.

Greta Bushnell and coauthors pointed to the problem of simultaneous prescribing of a new antidepressant with a benzodiazepine by 10% of doctors initiating antidepressants.4 Over 12% of this group of patients continued benzodiazepines long term, even though there was no difference in the response to antidepressant treatment at 6 months. Those with long-term benzodiazepine use were also more likely to have recent prescriptions for opiates.

A Finnish research team found that 34% of middle-aged and 55% of elderly people developed long-term use of benzodiazepines after an initial prescription.5 Those who became long-term users were more often older male receivers of social benefits, with psychiatric comorbidities and substance abuse histories.

Kevin Xu and coauthors reviewed a National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey dataset from 1999 to 2015 with follow-up on over 5,000 individuals in that period.6 They found doubling of all-cause mortality in users of benzodiazepines with or without accompanying use of opiates, a statistically significant increase.

Perhaps most alarming is the increased risk for Alzheimer’s dementia diagnosis in users of benzodiazepines. Two separate studies (Billoti de Gage and colleagues and Ettcheto and colleagues7,8) provided reviews of evidence for the relationship between use of benzodiazepines and development of dementia, and repeated warnings about close monitoring of patients and the need for alternative treatments for anxiety and insomnia in the elderly.

Be alert to underlying issues

Overburdened primary practitioners faced with complaints about sleep and anxiety understandably turn to medication rather than taking time to discuss the reasons for these problems or to describe nonmedication approaches to relief of symptoms. Even insured patients may have very limited options for “covered” psychiatric consultation, as many competent psychiatrists have moved to a cash-only system. It is easier to renew prescriptions than to counsel patients or refer them, and many primary care practitioners have limited experience with diagnosing causes of anxiety and insomnia, much less alternative medication approaches.

Psychiatrists should be aware of the frequency of underlying mood disorders that include sleep and anxiety as prominent symptoms; in fact, these symptoms are often what motivates patients to pursue treatment. It is critical to obtain not only a personal history of symptoms beginning in childhood up to the present, but also a family history of mood and anxiety problems. Mood dysregulation disorders are highly hereditary and a family history of mania or psychosis should raise concern about the cause of symptoms in one’s patient. A strong personal and/or family history of alcohol abuse and dependence may cover underlying undiagnosed mood dysregulation. Primary care physicians may not recognize mood dysregulation unless a patient is clearly manic or psychotic.

There is a cohort of patients who do well on antidepressant medication, but anorgasmia, fatigue, and emotional blunting are common side effects that affect compliance. When patients have unexpected responses to SSRI medications such as euphoria, agitation, anxiety, insomnia, and more prominent mood swings, primary care physicians may add a benzodiazepine, expecting the problem to abate with time. Unfortunately, this often leads to ongoing use of benzodiazepines, since attempts to stop them causes withdrawal effects that are indistinguishable from the original anxiety symptoms.

Most psychiatrists are aware that some patients need mood stabilization rather than mood elevation to maintain an adequate baseline mood. Lithium, anticonvulsants, and second-generation antipsychotics may be effective without adding antidepressant medication. Managing dosing and side effects requires time for follow-up visits with patients after initiating treatment but leads to more stability and better outcomes.

Benzodiazepines are appropriate and helpful in situations that cause transient anxiety and with patients who have done poorly with other options. Intermittent use is key to avoiding tolerance and inevitable dose increases. Some individuals can take low daily doses that are harmless, though these likely only prevent withdrawal rather than preventing anxiety. The placebo effect of taking a pill is powerful. And some patients take more doses than they admit to. Most practitioners have heard stories about the alprazolam that was accidentally spilled into the sink or the prescription bottle of diazepam that was lost or the lorazepam supply that was stolen by the babysitter.

These concepts are illustrated in case examples below.

Case one

Ms. A, a 55-year-old married female business administrator, admitted to using zolpidem at 40 mg per night for the past several months. She began with the typical dose of 10 mg at bedtime prescribed by her internist, but after several weeks, needed an additional 10 mg at 2 a.m. to stay asleep. As weeks passed, she found that she needed an additional 20 mg when she awoke at 2 a.m. Within months, she needed 20 mg to initiate sleep and 20 mg to maintain sleep. She obtained extra zolpidem from her gynecologist and came for consultation when refill requests were refused.

Ms. A had a family history of high anxiety in her mother and depressed mood in multiple paternal relatives, including her father. She had trouble sleeping beginning in adolescence, significant premenstrual dysphoria, and postpartum depression that led to a prescription for sertraline. Instead of feeling better, Ms. A remembers being agitated and unable to sleep, so she stopped it. Ms. A was now perimenopausal, and insomnia was worse. She had gradually increased wine consumption to a bottle of wine each night after work to “settle down.” This allowed her to fall asleep, but she inevitably awoke within 4 hours. Her internist noted an elevation in ALT and asked Ms. A about alcohol consumption. She was alarmed and cut back to one glass of wine per night but again couldn’t sleep. Her internist started zolpidem at that point.

The psychiatrist explained the concepts of tolerance and addiction and a plan to slowly taper off zolpidem while using quetiapine for sleep. She decreased to 20 mg of zolpidem at bedtime with quetiapine 50 mg and was able to stay asleep. After 3 weeks, Ms. A took zolpidem 10 mg at bedtime with quetiapine 75 mg and again, was able to fall asleep and stay asleep. After another 3 weeks, she increased quetiapine to 100 mg and stopped zolpidem without difficulty. This dose of quetiapine has continued to work well without significant side effects.

Case two

Ms. B, a 70-year-old married housewife, was referred for help with longstanding anxiety when her primary care doctor recognized that lorazepam, initially helpful at 1 mg twice daily, had required titration to 2 mg three times daily. Ms. B was preoccupied with having lorazepam on hand and never missed a dose. She had little interest in activities beyond her home, rarely socialized, and had fallen twice. She napped for 2 hours each afternoon, and sometimes had trouble staying asleep through the night.

Ms. B was reluctant to talk about her childhood history of hostility and undermining by her mother, who clearly preferred her older brother and was competitive with Ms. B. Her father traveled for work during the week and had little time for her. Ms. B had always seen herself as stupid and unlovable, which interfered with making friends. She attended college for 1 year but dropped out to marry her husband. He was also anxious and had difficulty socializing, but they found reassurance in each other. Their only child, a son in his 40s, was estranged from them, having married a woman who disliked Ms. B. Ms. B felt hopeless about developing a relationship with her grandchildren who were rarely allowed to visit. Despite her initial shame in talking about these painful problems, Ms. B realized that she felt better and scheduled monthly visits to check in.

Ms. B understood the risks of using lorazepam and wanted to stop it but was terrified of becoming anxious again. We set up a very slow tapering schedule that lowered her total dose by 0.5 mg every 2 weeks. At the same time, she began escitalopram which was effective at 20 mg. Ms. B noted that she no longer felt anxious upon awakening but was still afraid to miss a dose of lorazepam. As she felt more confident and alert, Ms. B joined a painting class at a local community center and was gratified to find that she was good at working with watercolors. She invited her neighbors to come for dinner and was surprised at how friendly and open they were. Once she had tapered to 1 mg twice daily, Ms. B began walking for exercise as she now had enough energy that it felt good to move around. After 6 months, she was completely off lorazepam, and very grateful to have discovered her capacity to improve her pleasure in life.

Case three

Ms. C, a 48-year-old attorney was referred for help with anxiety and distress in the face of separation from her husband who had admitted to an affair after she heard him talking to his girlfriend from their basement. She was unsure whether she wanted to save the marriage or end it and was horrified at the thought of dating. She had never felt especially anxious or depressed and had a supportive circle of close friends. She was uncharacteristically unable to concentrate long enough to consider her options because of anxiety.

A dose of clonazepam 0.5 mg allowed her to stay alert but calm enough to reflect on her feelings. She used it intermittently over several months and maintained regular individual psychotherapy sessions that allowed her to review the situation thoroughly. On her psychiatrist’s recommendation, she contacted a colleague to represent her if she decided to initiate divorce proceedings. She attempted to engage her husband in marital therapy, and his reluctance made it clear to her that she could no longer trust him. Ms. C offered him the option of a dissolution if he was willing to cooperate, or to sue for divorce if not. Once Ms. C regained her confidence and recognized that she would survive this emotionally fraught situation, she no longer needed clonazepam.

Summary

The risks, which include cognitive slowing, falls and fractures, and withdrawal phenomena when abruptly stopped, make this class dangerous for all patients but particularly the elderly. Benzodiazepines are nonetheless useful medications for patients able to use them intermittently, whether on an alternating basis with other medications (for example, quetiapine alternating with clonazepam for chronic insomnia) or because symptoms of anxiety are intermittent. Psychiatrists treating tolerant patients should be familiar with the approach of tapering slowly while introducing more appropriate medications at adequate doses to manage symptoms.

Dr. Kaplan is training and supervising psychoanalyst at the Cincinnati Psychoanalytic Institute and volunteer professor of clinical psychiatry at the University of Cincinnati. The author reported no financial relationships with any companies whose products are mentioned in this article, or with manufacturers of competing products.

References

1. Olfson M et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015 Feb;72(2):136-42. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2014.1763.

2. Lin FY et al. Sleep. 2014 Apr 1;37(4):673-9. doi: 10.5665/sleep.3566.

3. Thomas R and Ramos-Rivas E. Psychiatr Ann. 2018;48(6):266-70. doi: 10.3928/00485713-20180513-01.

4. Bushnell GA et al. JAMA Psychiatry. 2017 Jul 1;74(7):747-55. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.1273.

5. Taipale H et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2019029. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.19029.

6. Xu KY et al. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(12):e2028557. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.28557.

7. Billioti de Gage S et al. BMJ. 2014;349:g5205. doi: 10.1136/bmj.g5205.

8. Ettcheto M et al. Front Aging Neurosci. 2020 Jan 8;11:344. doi: 10.3389/fnagi.2019.00344.

Nail Changes Associated With Thyroid Disease

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

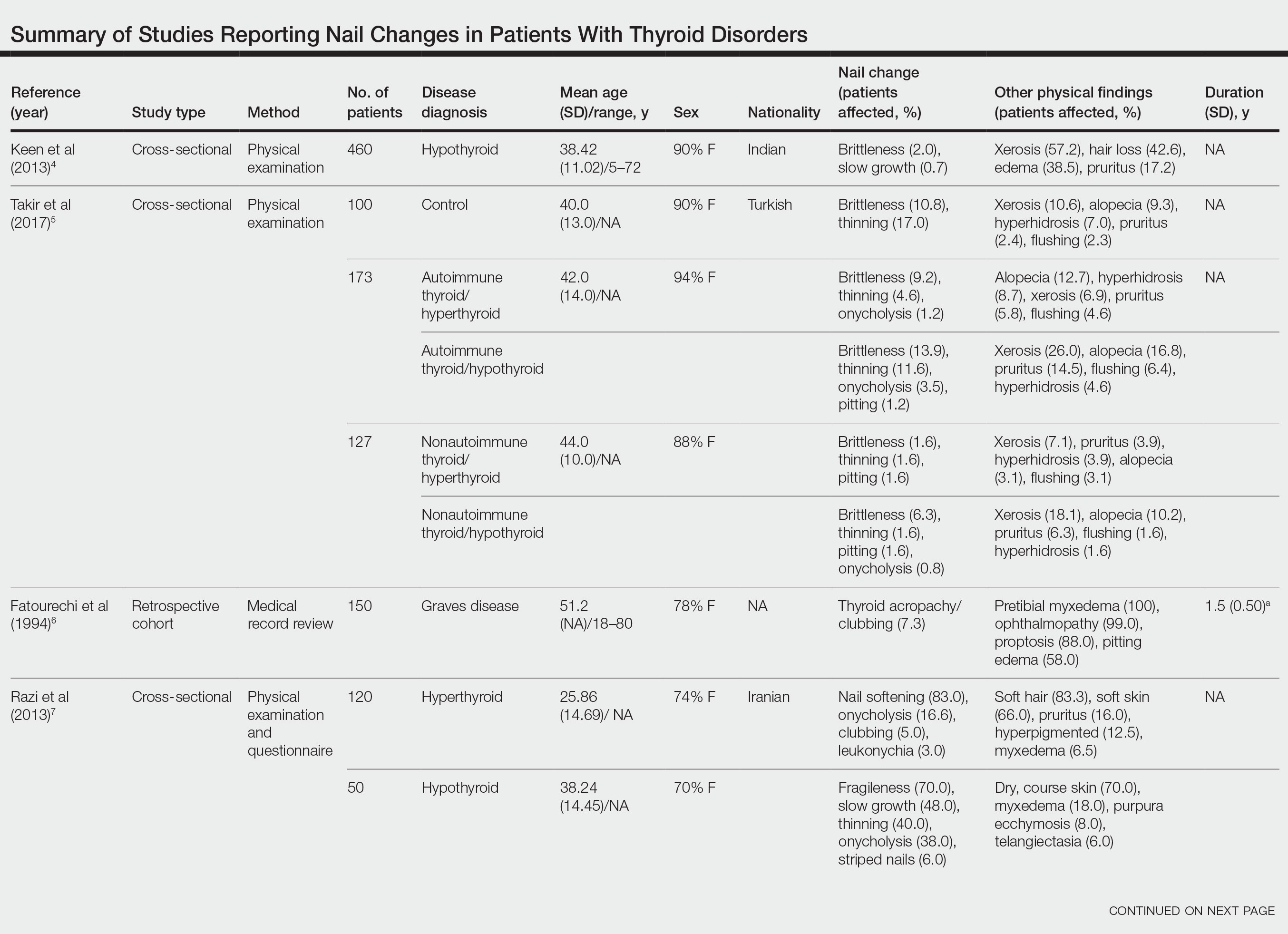

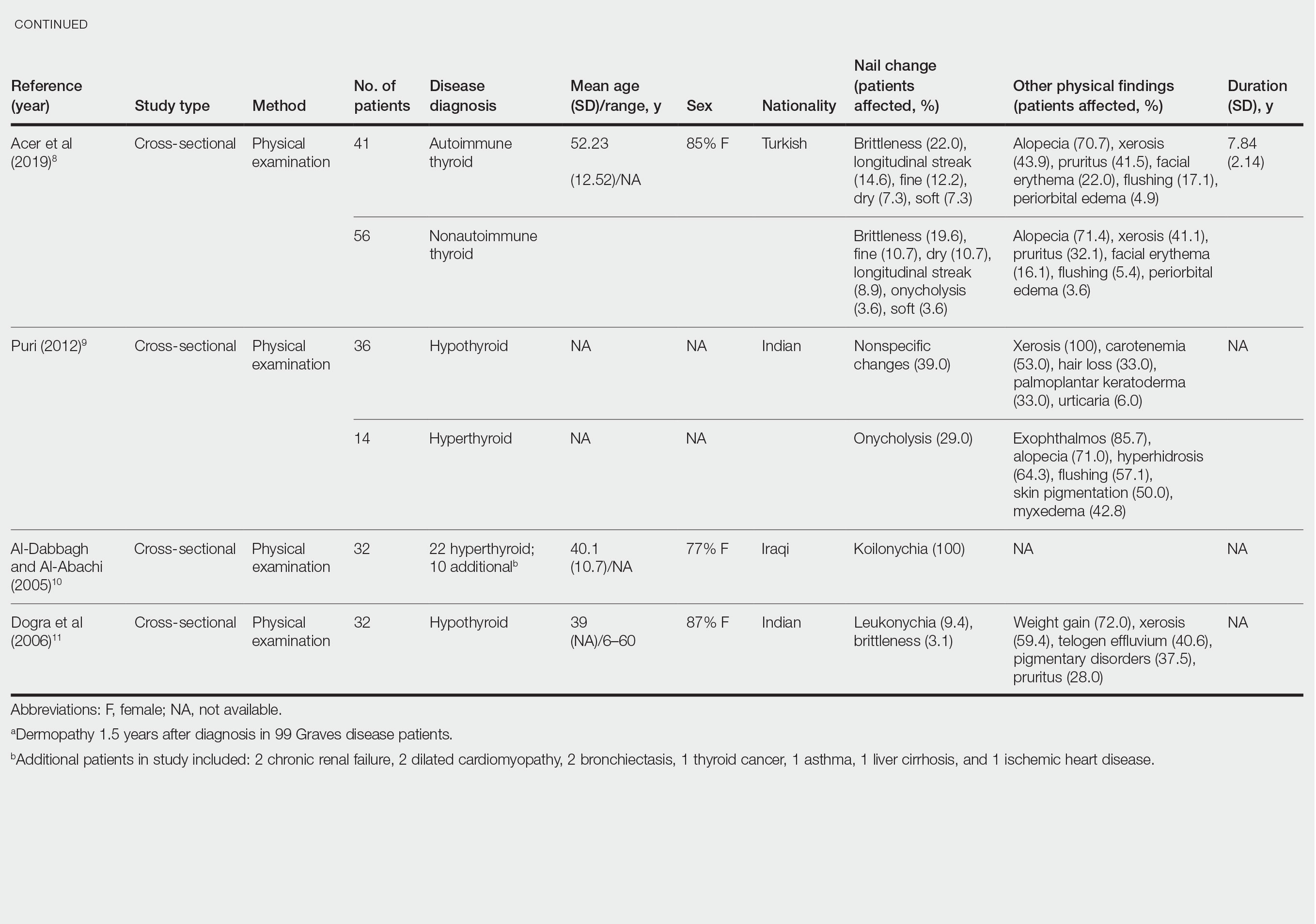

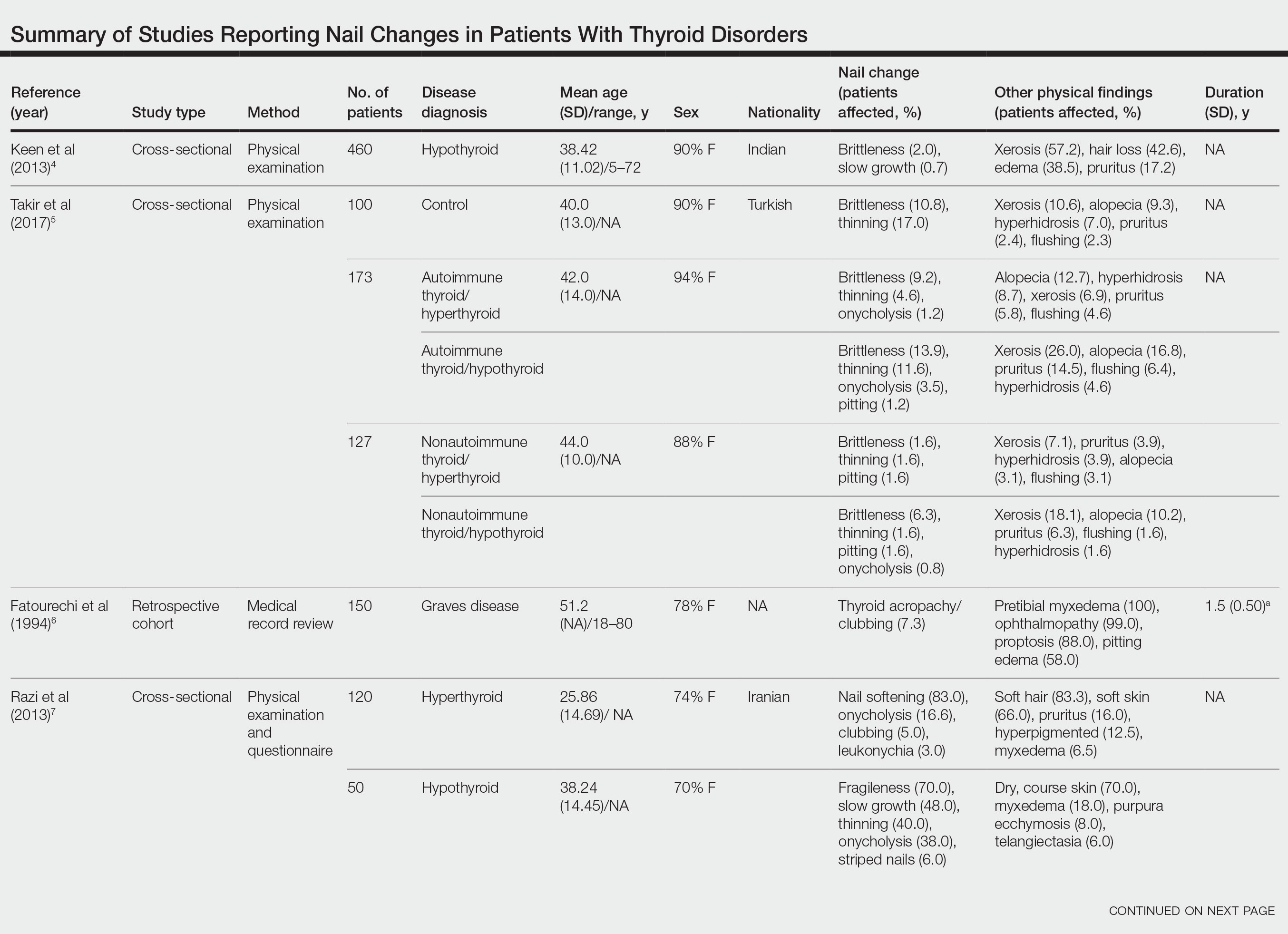

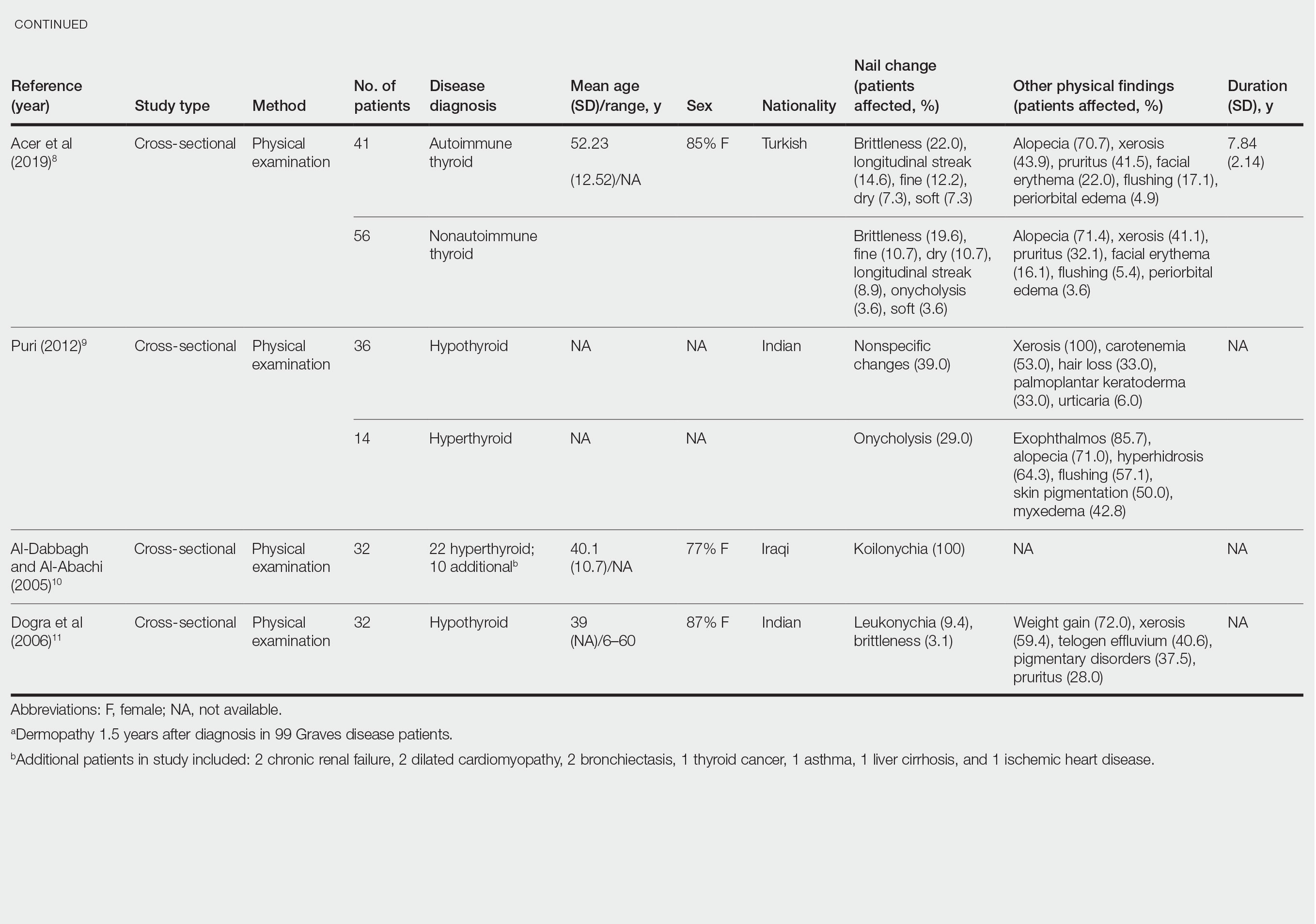

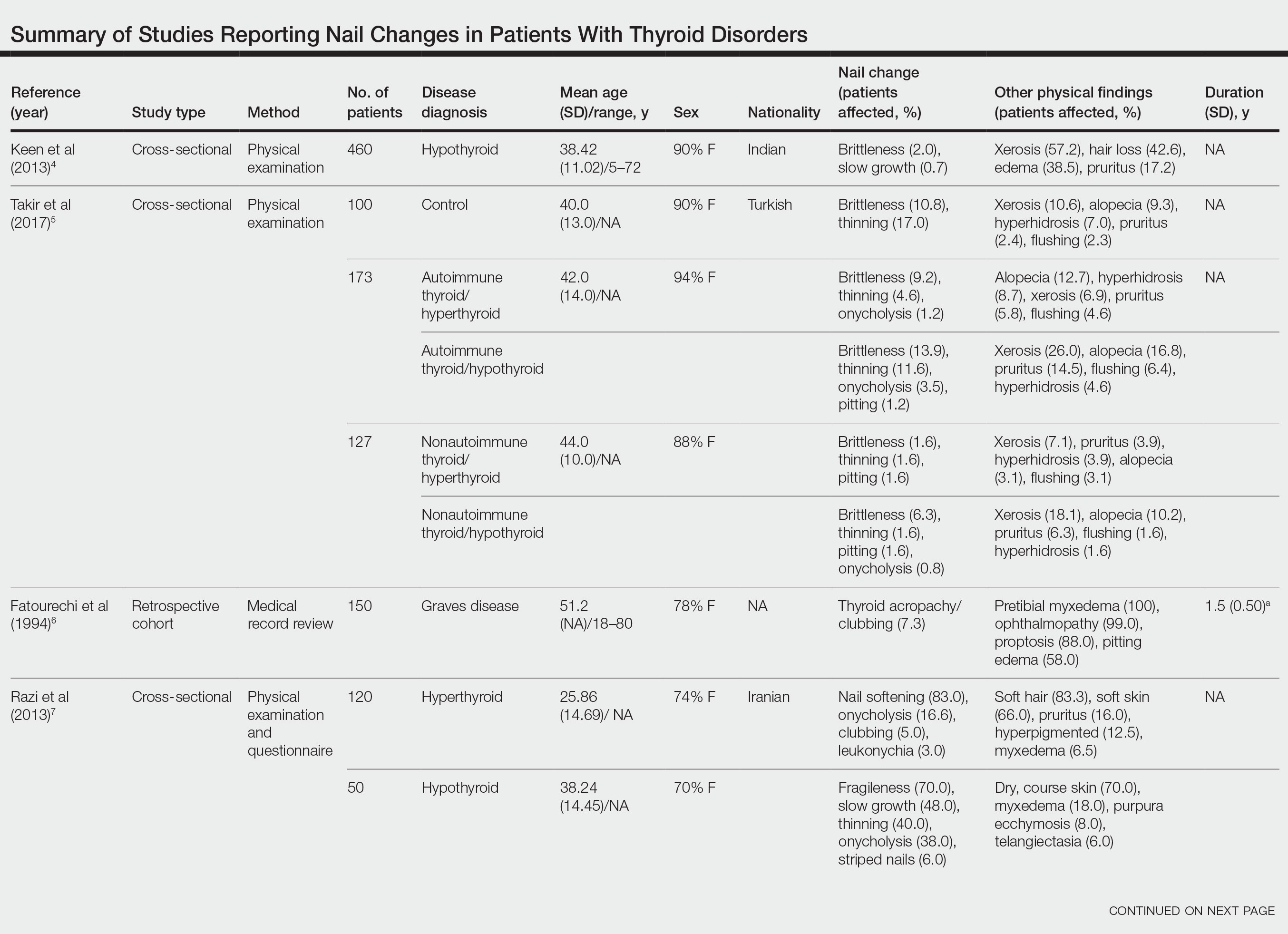

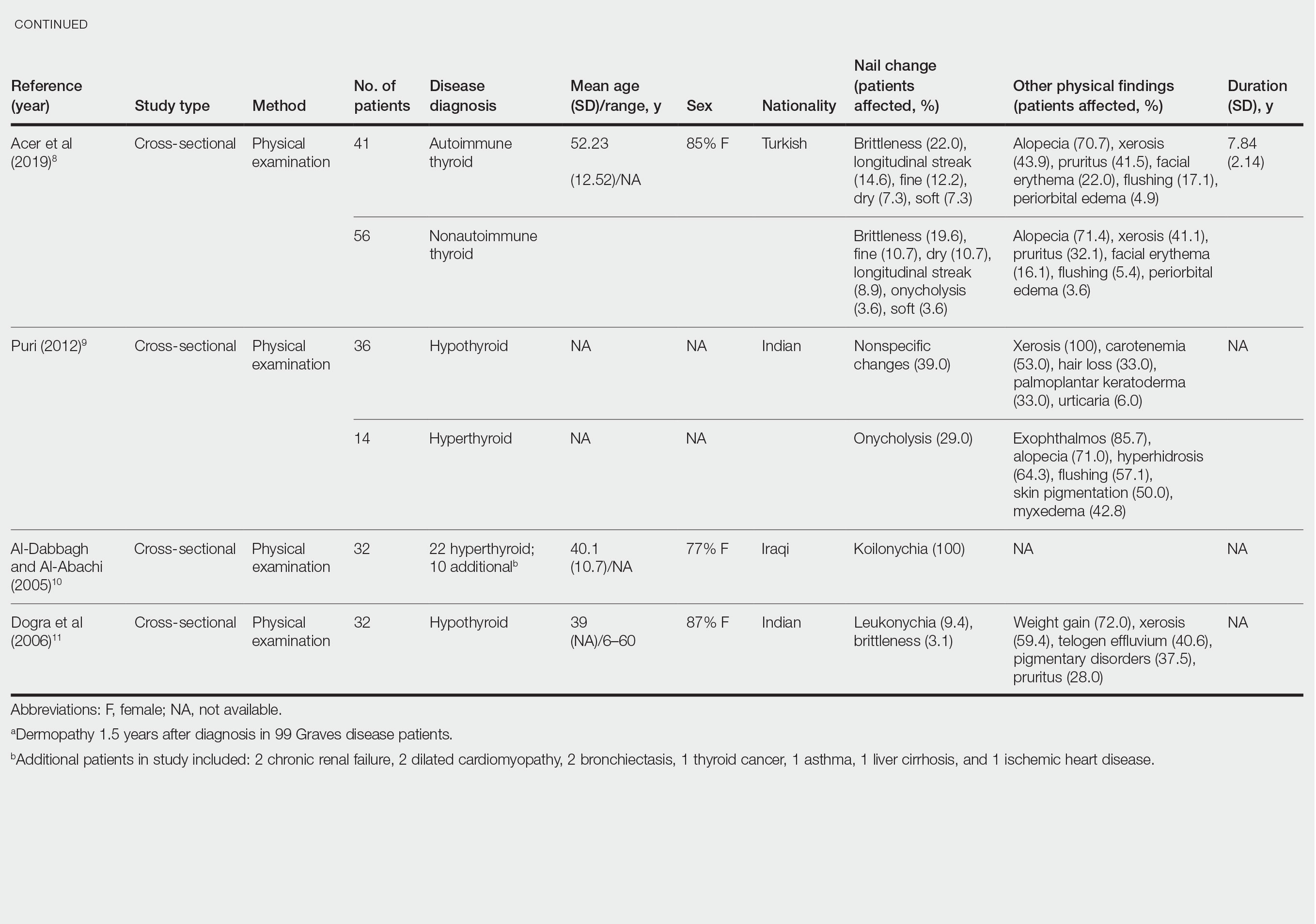

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

The major classifications of thyroid disease include hyperthyroidism, which is seen in Graves disease, and hypothyroidism due to iodine deficiency and Hashimoto thyroiditis, which have potentially devastating health consequences. The prevalence of hyperthyroidism ranges from 0.2% to 1.3% in iodine-sufficient parts of the world, and the prevalence of hypothyroidism in the general population is 5.3% in Europe and 3.7% in the United States.1 Thyroid hormones physiologically potentiate α- and β-adrenergic receptors by increasing their sensitivity to catecholamines. Excess thyroid hormones manifest as tachycardia, increased cardiac output, increased body temperature, hyperhidrosis, and warm moist skin. Reduced sensitivity of adrenergic receptors to catecholamines from insufficient thyroid hormones results in a lower metabolic rate and decreases response to the sympathetic nervous system.2 Nail changes in thyroid patients have not been well studied.3 Our objectives were to characterize nail findings in patients with thyroid disease. Early diagnosis of thyroid disease and prompt referral for treatment may be instrumental in preventing serious morbidities and permanent sequelae.

Methods

PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, and Google Scholar were searched for the terms nail + thyroid, nail + hyperthyroid, nail + hypothyroid, nail + Graves, and nail + Hashimoto on June 10, 2020, and then updated on November 18, 2020. All English-language articles were included. Non–English-language articles and those that did not describe clinical trials of nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were excluded. One study that utilized survey-based data for nail changes without corroboration with physical examination findings was excluded. Hypothyroidism/hyperthyroidism was defined by all authors as measurement of serum thyroid hormones triiodothyronine, thyroxine, and thyroid-stimulating hormone outside of the normal range. Eight studies were included in the final analysis. Patient demographics, thyroid disease type, physical examination findings, nail clinical findings, age at diagnosis, age at onset of nail changes, treatments/medications, and comorbidities were recorded and analyzed.

Results

Nail changes in patients with thyroid disease were reported in 8 studies (7 cross-sectional, 1 retrospective cohort) and are summarized in the Table.4-11 The mean age was 41.2 years (range, 5–80 years), with a higher representation of females (range, 70%–94% female). The most common nail changes in thyroid patients were koilonychia, clubbing, and nail brittleness. Other changes included onycholysis, thin nails, dryness, and changes in nail growth rate. Frequent physical findings were xerosis, pruritus, and alopecia.

Both koilonychia and clubbing were reported in patients with hyperthyroidism. In a study of 32 patients with koilonychia, 22 (68.8%) were diagnosed with hyperthyroidism.10 Nail clubbing affected 7.3% of Graves disease patients (n=150)6 and 5.0% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120).7 Dermopathy presented more than 1 year after diagnosis of Graves disease in 99 (66%) of 150 patients as a late manifestation of thyrotoxicosis.6 Additional physical features in patients with Graves disease (n=150) were pretibial myxedema (100%), ophthalmopathy (99.0%), and proptosis (88.0%). Non–Graves hyperthyroid patients showed physical features of soft hair (83.3%) and soft skin (66.0%).7

Nail brittleness was a frequently reported nail change in thyroid patients (4/8 studies, 50%), most often seen in 22% of autoimmune patients, 19.6% of nonautoimmune patients, 13.9% of hypothyroid patients, and 9.2% of hyperthyroid patients.5,8 For comparison, brittle nails presented in 10.8% of participants in a control group.5 Brittle nails in thyroid patients often are accompanied by other nail findings such as thinning, onycholysis, and pitting.

Among hypothyroid patients, nail changes included fragility (70%; n=50), slow growth (48%; n=50), thinning (40%; n=50), onycholysis (38%; n=50),7 and brittleness (13.9%; n=173).5 Less common nail changes in hypothyroid patients were leukonychia (9.4%; n=32), striped nails (6%; n=50), and pitting (1.2%; n=173).5,7,11 Among hyperthyroid patients, the most common nail changes were koilonychia (100%; n=22), softening (83%; n=120), onycholysis (29%; n=14), and brittleness (9.2%; n=173).5,7,9,10 Less common nail changes in hyperthyroid patients were clubbing (5%; n=120), thinning (4.6%; n=173), and leukonychia (3%; n=120).5,7

Additional cutaneous findings of thyroid disorder included xerosis, alopecia, pruritus, and weight change. Xerosis was most common in hypothyroid disease (57.2%; n=460).4 In 2 studies,8,9 alopecia affected approximately 70% of autoimmune, nonautoimmune, and hyperthyroid patients. Hair loss was reported in 42.6% (n=460)4 and 33.0% (n=36)9 of hypothyroid patients. Additionally, pruritus affected up to 28% (n=32)11 of hypothyroid and 16.0% (n=120)7 of hyperthyroid patients and was more common in autoimmune (41%) vs nonautoimmune (32%) thyroid patients.8 Weight gain was seen in 72% of hypothyroid patients (n=32),11 and soft hair and skin were reported in 83.3% and 66% of hyperthyroid patients (n=120), respectively.7 Flushing was a less common physical finding in thyroid patients (usually affecting <10%); however, it also was reported in 17.1% of autoimmune and 57.1% of hyperthyroid patients from 2 separate studies.8,9

Comment

There are limited data describing nail changes with thyroid disease. Singal and Arora3 reported in their clinical review of nail changes in systemic disease that koilonychia, onycholysis, and melanonychia are associated with thyroid disorders. We similarly found that koilonychia and onycholysis are associated with thyroid disorders without an association with melanonychia.

In his clinical review of thyroid hormone action on the skin, Safer12 described hypothyroid patients having coarse, dull, thin, and brittle nails, whereas in thyrotoxicosis, patients had shiny, soft, and concave nails with onycholysis; however, the author commented that there were limited data on the clinical findings in thyroid disorders. These nail findings are consistent with our results, but onycholysis was more common in hypothyroid patients than in hyperthyroid patients in our review. Fox13 reported on 30 cases of onycholysis, stating that it affected patients with hypothyroidism and improved with thyroid treatment. In a clinical review of 8 commonly seen nail abnormalities, Fowler et al14 reported that hyperthyroidism was associated with nail findings in 5% of cases and may result in onycholysis of the fourth and fifth nails or all nails. They also reported that onychorrhexis may be seen in patients with hypothyroidism, a finding that differed from our results.14

The mechanism of nail changes in thyroid disease has not been well studied. A protein/amino acid–deficiency state may contribute to the development of koilonychia. Hyperthyroid patients, who have high metabolic activity, may have hypoalbuminemia, leading to koilonychia.15 Hypothyroidism causes hypothermia from decreased metabolic rate and secondary compensatory vasoconstriction. Vasoconstriction decreases blood flow of nutrients and oxygen to cutaneous structures and may cause slow-growing, brittle nails. In hyperthyroidism, vasodilation alternatively may contribute to the fast-growing nails. Anti–thyroid-stimulating hormone receptor antibodies in Graves disease may increase the synthesis of hyaluronic acid and glycosaminoglycans from fibroblasts, keratinocytes, adipocytes, or endothelial cells in the dermis and may contribute to development of clubbing.16

Our review is subject to several limitations. We recorded nail findings as they were described in the original studies; however, we could not confirm the accuracy of these descriptions. In addition, some specific nail changes were not described in sufficient detail. In all but 1 study, dermatologists performed the physical examination. In the study by Al-Dabbagh and Al-Abachi,10 the physical examinations were performed by general medicine physicians, but they selected only for patients with koilonychia and did not assess for other skin findings. Fragile nails and brittle nails were described in hypothyroid and hyperthyroid patients, but these nail changes were not described in detail. There also were studies describing nail changes in thyroid patients; some studies had small numbers of patients, and many did not have a control group.

Conclusion

Nail changes may be early clinical presenting signs of thyroid disorders and may be the clue to prompt diagnosis of thyroid disease. Dermatologists should be mindful that fragile, slow-growing, thin nails and onycholysis are associated with hypothyroidism and that koilonychia, softening, onycholysis, and brittle nail changes may be seen in hyperthyroidism. Our review aimed to describe nail changes associated with thyroid disease to guide dermatologists on diagnosis and promote future research on dermatologic manifestations of thyroid disease. Future research is necessary to explore the association between koilonychia and hyperthyroidism as well as the association of nail changes with thyroid disease duration and severity.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

- Taylor PN, Albrecht D, Scholz A, et al. Global epidemiology of hyperthyroidism and hypothyroidism. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2018;14:301-316.

- Lause M, Kamboj A, Faith EF. Dermatologic manifestations of endocrine disorders. Transl Pediatr. 2017;6:300-312.

- Singal A, Arora R. Nail as a window of systemic diseases. Indian Dermatol Online J. 2015;6:67-74.

- Keen MA, Hassan I, Bhat MH. A clinical study of the cutaneous manifestations of hypothyroidism in Kashmir Valley. Indian J Dermatol. 2013;58:326.

- Takir M, Özlü E, Köstek O, et al. Skin findings in autoimmune and nonautoimmune thyroid disease with respect to thyroid functional status and healthy controls. Turk J Med Sci. 2017;47:764-770.

- Fatourechi V, Pajouhi M, Fransway AF. Dermopathy of Graves disease (pretibial myxedema). review of 150 cases. Medicine (Baltimore). 1994;73:1-7.

- Razi A, Golforoushan F, Nejad AB, et al. Evaluation of dermal symptoms in hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism. Pak J Biol Sci. 2013;16:541-544.

- Acer E, Ag˘aog˘lu E, Yorulmaz G, et al. Evaluation of cutaneous manifestations in patients under treatment with thyroid disease. Turkderm-Turk Arch Dermatol Venereol. 2019;54:46-50.

- Puri N. A study on cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. Indian J Dermatol. 2012;57:247-248.

- Al-Dabbagh TQ, Al-Abachi KG. Nutritional koilonychia in 32 Iraqi subjects. Ann Saudi Med. 2005;25:154-157.

- Dogra A, Dua A, Singh P. Thyroid and skin. Indian J Dermatol. 2006;51:96-99.

- Safer JD. Thyroid hormone action on skin. Dermatoendocrinol. 2011;3:211-215.

- Fox EC. Diseases of the nails: report of cases of onycholysis. Arch Derm Syphilol. 1940;41:98-112.

- Fowler JR, Stern E, English JC 3rd, et al. A hand surgeon’s guide to common onychodystrophies. Hand (N Y). 2014;9:24-28.

- Truswell AS. Nutritional factors in disease. In: Edwards CRW, Bouchier IAD, Haslett C, et al, eds. Davidson’s Principles and Practice of Medicine. 17th ed. Churchill Livingstone; 1995:554.

- Heymann WR. Cutaneous manifestations of thyroid disease. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1992;26:885-902.

Practice Points

- Koilonychia is associated with hyperthyroidism.

- Clubbing is a manifestation of thyroid acropachy in Graves disease and also affects other patients with hyperthyroidism.

- Onycholysis improves in patients with hypothyroidism treated with thyroid hormone replacement therapy.

Should patients undergoing surgical treatment for cervical lesions also receive an HPV vaccination?

Human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine given around the time women have surgery for precancerous cervical lesions might lead to a reduction in the risk of lesions returning, as well as other HPV-related diseases, but the effects of this remain unclear.

The authors of the new study, published in The BMJ, explained that women who have been treated for high-grade cervical intra-epithelial neoplasia (CIN) have a “lifelong residual high risk of cervical cancer and other malignancies related to HPV infection,” and some research suggests that giving a preventive HPV vaccine alongside treatment for CIN might help to “reduce the risk in these women.”

HPV vaccination is highly effective at preventing the development of precancerous cervical lesions, CIN, and in the U.K., HPV vaccination is offered to girls and boys around the age of 12 or 13.

Eluned Hughes, head of information and engagement at Jo’s Cervical Cancer Trust, said: “Recent evidence has found that cases of cervical cancer have fallen 87% since the introduction of the HPV vaccine program in U.K. schools in 2008.”

“However, women over the age of 27, for whom the vaccine was not available, remain at increased risk of cervical cancer,” she highlighted.

Significant risk of bias and scarcity of data

In the study, researchers set out to explore the efficacy of HPV vaccination on the risk of HPV infection and recurrent diseases related to HPV infection in individuals undergoing local surgical treatment of preinvasive genital disease.

The systematic review and meta-analysis, led by researchers at Imperial College London, screened data from PubMed (Medline), Scopus, Cochrane, Web of Science, and ClinicalTrials.gov from inception to March 31, 2021.

The researchers analyzed the results of 18 studies – two randomized controlled trials (RCTs), 12 observational studies, and four post-hoc analyses of RCTs.

The authors said that the two RCTs were classified as low risk of bias, while in the observational studies and post-hoc analyses, risk of bias was moderate for seven, serious for seven, and critical for two. Average length of follow-up was 36 months.

There was a reduction of 57% in the risk of recurrence of high-grade pre-invasive disease (CIN2+) in individuals who were vaccinated, compared with those who were not vaccinated. “The effect estimate was “even more pronounced” – a relative 74% reduction – when the risk of recurrence of CIN2+ was assessed for disease related to the two high-risk HPV types – HPV16 and HPV18,” explained the authors.

However, the researchers noted that these effects are unclear because of the “scarcity of data” and the “moderate to high overall risk of bias” of the available studies.

Quality of evidence inconclusive – more trials needed

With regards to CIN3, the risk of recurrence of was also reduced in patients who were vaccinated, but there was a high level of uncertainty about the quality of this evidence, cautioned the authors.