User login

Children's Hospital Colorado: Annual Conference on Pediatric Infectious Diseases

Avoid C. difficile testing in infants

VAIL, COLO. – The worldly private eye in many a film noir has cautioned a potential client, "It’s best not to ask questions you’d rather not know the answer to."

That warning is apt as well when it comes to Clostridium difficile testing in infants with persistent diarrhea.

"We discourage testing of infants because we can’t actually distinguish colonization from C. difficile disease. I think that’s a big, complicated issue. And we get this question not infrequently: ‘What do we do with this positive test in a patient less than 1 year old?’ My answer is, ‘I don’t know. You shouldn’t test them in the first place,’ " Dr. Samuel R. Dominguez said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Keep in mind that there are a lot of reasons other than C. difficile disease why an infant can have persistent diarrhea. I wouldn’t want anyone to be deluded by a positive C. difficile test. So I would have great caution in testing anyone under 1 year of age. It is true that you can have C. difficile infection under 1 year of age that can cause disease, but it is a rare event, not a common one," stressed Dr. Dominguez, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the hospital and the University of Colorado, Denver.

Unlike C. difficile disease, asymptomatic C. difficile colonization is extremely common in infants. For example, a French study involving stool testing of 85 asymptomatic infants in two day-care centers found a C. difficile carriage prevalence of 36% at age 2-6 months, climbing to 67% at 7-9 months, then peaking at 75% at 10-12 months, at which point 19% of the children harbored toxigenic strains. Yet none of the children had clinical disease at any point. After 12 months of age, the carriage rate declined steadily to 6% at 24-36 months (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:1209-15), which is comparable to the asymptomatic carriage rate in adults.

The significance of the high rate of C. difficile colonization in infants is controversial and poorly understood. It’s known that breastfed infants are less likely to be colonized than formula-fed infants, and that maternal-fetal transmission is rarely the source of infant colonization. Infants have the same rates of colonization and toxin production regardless of whether they have diarrhea, he noted.

Among the hypotheses offered to explain the rarity of C. difficile symptomatic disease in infants despite their high colonization rate is the observation that the gut microbial flora early in life is still in the process of formation. Its composition doesn’t approach that of the adult microbiome until about 1 year of age. Also, the infant immune system is immature. It is possible, although speculative, that the high rate of infant colonization is the result of a lack of protective gut bacteria early in life, while the rarity of symptomatic disease is a consequence of the immature immune system’s inability to recruit neutrophils, or alternatively is perhaps due to an absence of C. difficile receptors in the infant intestine.

Dr. Dominguez’ caution against testing for C. difficile in infants mirrors that of a recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement (Pediatrics 2013;131:196-200), which declared "it is prudent" to avoid testing in children under age 1 year. The AAP recommends first looking for other possible causes of diarrhea, especially viral pathogens, before testing for C. difficile in 1- to 3-year-olds. In symptomatic children over age 3, a positive test indicates probable infection.

An intriguing speculation recently raised in the literature is that colonized children might pose a risk to adults, serving as a reservoir for infection in much the same way they act as a reservoir for respiratory pathogens including influenza and pneumococcus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57:9-12). There is, however, no evidence as yet for this notion, Dr. Dominguez noted.

Current practice guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-98) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55) recommend PCR for C. difficile toxin genes as the standard diagnostic test. The guidelines list as an acceptable alternative a two-step method using a glutamate dehydrogenase test as a screen; if positive, it is to be followed by PCR or enzyme immunoassay. Dr. Dominguez indicated he has a problem with this recommendation because the glutamate dehydrogenase test has what he considers unacceptably high false-positive and -negative rates.

Enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B is not endorsed as a stand-alone test in the latest guidelines because of its lack of sensitivity.

The guidelines further recommend that in light of the substantial asymptomatic colonization rates in both children and adults, only stools from symptomatic patients should be tested. Indeed, the microbiology laboratory at the Children’s Hospital Colorado adheres strictly to this guidance, refusing to test formed stool samples.

Repeat testing because of a suspected initial false-positive result is discouraged in the guidelines, as is a test-for-cure at the end of treatment, since virus, toxins, and genome are shed for weeks after the diarrhea is resolved.

"We see a lot of this test-for-cure at our hospital. However, testing for cure is not recommended in the guidelines and should not be done in most cases," Dr. Dominguez emphasized.

He reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – The worldly private eye in many a film noir has cautioned a potential client, "It’s best not to ask questions you’d rather not know the answer to."

That warning is apt as well when it comes to Clostridium difficile testing in infants with persistent diarrhea.

"We discourage testing of infants because we can’t actually distinguish colonization from C. difficile disease. I think that’s a big, complicated issue. And we get this question not infrequently: ‘What do we do with this positive test in a patient less than 1 year old?’ My answer is, ‘I don’t know. You shouldn’t test them in the first place,’ " Dr. Samuel R. Dominguez said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Keep in mind that there are a lot of reasons other than C. difficile disease why an infant can have persistent diarrhea. I wouldn’t want anyone to be deluded by a positive C. difficile test. So I would have great caution in testing anyone under 1 year of age. It is true that you can have C. difficile infection under 1 year of age that can cause disease, but it is a rare event, not a common one," stressed Dr. Dominguez, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the hospital and the University of Colorado, Denver.

Unlike C. difficile disease, asymptomatic C. difficile colonization is extremely common in infants. For example, a French study involving stool testing of 85 asymptomatic infants in two day-care centers found a C. difficile carriage prevalence of 36% at age 2-6 months, climbing to 67% at 7-9 months, then peaking at 75% at 10-12 months, at which point 19% of the children harbored toxigenic strains. Yet none of the children had clinical disease at any point. After 12 months of age, the carriage rate declined steadily to 6% at 24-36 months (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:1209-15), which is comparable to the asymptomatic carriage rate in adults.

The significance of the high rate of C. difficile colonization in infants is controversial and poorly understood. It’s known that breastfed infants are less likely to be colonized than formula-fed infants, and that maternal-fetal transmission is rarely the source of infant colonization. Infants have the same rates of colonization and toxin production regardless of whether they have diarrhea, he noted.

Among the hypotheses offered to explain the rarity of C. difficile symptomatic disease in infants despite their high colonization rate is the observation that the gut microbial flora early in life is still in the process of formation. Its composition doesn’t approach that of the adult microbiome until about 1 year of age. Also, the infant immune system is immature. It is possible, although speculative, that the high rate of infant colonization is the result of a lack of protective gut bacteria early in life, while the rarity of symptomatic disease is a consequence of the immature immune system’s inability to recruit neutrophils, or alternatively is perhaps due to an absence of C. difficile receptors in the infant intestine.

Dr. Dominguez’ caution against testing for C. difficile in infants mirrors that of a recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement (Pediatrics 2013;131:196-200), which declared "it is prudent" to avoid testing in children under age 1 year. The AAP recommends first looking for other possible causes of diarrhea, especially viral pathogens, before testing for C. difficile in 1- to 3-year-olds. In symptomatic children over age 3, a positive test indicates probable infection.

An intriguing speculation recently raised in the literature is that colonized children might pose a risk to adults, serving as a reservoir for infection in much the same way they act as a reservoir for respiratory pathogens including influenza and pneumococcus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57:9-12). There is, however, no evidence as yet for this notion, Dr. Dominguez noted.

Current practice guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-98) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55) recommend PCR for C. difficile toxin genes as the standard diagnostic test. The guidelines list as an acceptable alternative a two-step method using a glutamate dehydrogenase test as a screen; if positive, it is to be followed by PCR or enzyme immunoassay. Dr. Dominguez indicated he has a problem with this recommendation because the glutamate dehydrogenase test has what he considers unacceptably high false-positive and -negative rates.

Enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B is not endorsed as a stand-alone test in the latest guidelines because of its lack of sensitivity.

The guidelines further recommend that in light of the substantial asymptomatic colonization rates in both children and adults, only stools from symptomatic patients should be tested. Indeed, the microbiology laboratory at the Children’s Hospital Colorado adheres strictly to this guidance, refusing to test formed stool samples.

Repeat testing because of a suspected initial false-positive result is discouraged in the guidelines, as is a test-for-cure at the end of treatment, since virus, toxins, and genome are shed for weeks after the diarrhea is resolved.

"We see a lot of this test-for-cure at our hospital. However, testing for cure is not recommended in the guidelines and should not be done in most cases," Dr. Dominguez emphasized.

He reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – The worldly private eye in many a film noir has cautioned a potential client, "It’s best not to ask questions you’d rather not know the answer to."

That warning is apt as well when it comes to Clostridium difficile testing in infants with persistent diarrhea.

"We discourage testing of infants because we can’t actually distinguish colonization from C. difficile disease. I think that’s a big, complicated issue. And we get this question not infrequently: ‘What do we do with this positive test in a patient less than 1 year old?’ My answer is, ‘I don’t know. You shouldn’t test them in the first place,’ " Dr. Samuel R. Dominguez said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"Keep in mind that there are a lot of reasons other than C. difficile disease why an infant can have persistent diarrhea. I wouldn’t want anyone to be deluded by a positive C. difficile test. So I would have great caution in testing anyone under 1 year of age. It is true that you can have C. difficile infection under 1 year of age that can cause disease, but it is a rare event, not a common one," stressed Dr. Dominguez, a pediatric infectious diseases specialist at the hospital and the University of Colorado, Denver.

Unlike C. difficile disease, asymptomatic C. difficile colonization is extremely common in infants. For example, a French study involving stool testing of 85 asymptomatic infants in two day-care centers found a C. difficile carriage prevalence of 36% at age 2-6 months, climbing to 67% at 7-9 months, then peaking at 75% at 10-12 months, at which point 19% of the children harbored toxigenic strains. Yet none of the children had clinical disease at any point. After 12 months of age, the carriage rate declined steadily to 6% at 24-36 months (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;55:1209-15), which is comparable to the asymptomatic carriage rate in adults.

The significance of the high rate of C. difficile colonization in infants is controversial and poorly understood. It’s known that breastfed infants are less likely to be colonized than formula-fed infants, and that maternal-fetal transmission is rarely the source of infant colonization. Infants have the same rates of colonization and toxin production regardless of whether they have diarrhea, he noted.

Among the hypotheses offered to explain the rarity of C. difficile symptomatic disease in infants despite their high colonization rate is the observation that the gut microbial flora early in life is still in the process of formation. Its composition doesn’t approach that of the adult microbiome until about 1 year of age. Also, the infant immune system is immature. It is possible, although speculative, that the high rate of infant colonization is the result of a lack of protective gut bacteria early in life, while the rarity of symptomatic disease is a consequence of the immature immune system’s inability to recruit neutrophils, or alternatively is perhaps due to an absence of C. difficile receptors in the infant intestine.

Dr. Dominguez’ caution against testing for C. difficile in infants mirrors that of a recent American Academy of Pediatrics policy statement (Pediatrics 2013;131:196-200), which declared "it is prudent" to avoid testing in children under age 1 year. The AAP recommends first looking for other possible causes of diarrhea, especially viral pathogens, before testing for C. difficile in 1- to 3-year-olds. In symptomatic children over age 3, a positive test indicates probable infection.

An intriguing speculation recently raised in the literature is that colonized children might pose a risk to adults, serving as a reservoir for infection in much the same way they act as a reservoir for respiratory pathogens including influenza and pneumococcus (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2013;57:9-12). There is, however, no evidence as yet for this notion, Dr. Dominguez noted.

Current practice guidelines from the American College of Gastroenterology (Am. J. Gastroenterol. 2013;108:478-98) and Infectious Diseases Society of America (Infect. Control Hosp. Epidemiol. 2010;31:431-55) recommend PCR for C. difficile toxin genes as the standard diagnostic test. The guidelines list as an acceptable alternative a two-step method using a glutamate dehydrogenase test as a screen; if positive, it is to be followed by PCR or enzyme immunoassay. Dr. Dominguez indicated he has a problem with this recommendation because the glutamate dehydrogenase test has what he considers unacceptably high false-positive and -negative rates.

Enzyme immunoassay for toxins A and B is not endorsed as a stand-alone test in the latest guidelines because of its lack of sensitivity.

The guidelines further recommend that in light of the substantial asymptomatic colonization rates in both children and adults, only stools from symptomatic patients should be tested. Indeed, the microbiology laboratory at the Children’s Hospital Colorado adheres strictly to this guidance, refusing to test formed stool samples.

Repeat testing because of a suspected initial false-positive result is discouraged in the guidelines, as is a test-for-cure at the end of treatment, since virus, toxins, and genome are shed for weeks after the diarrhea is resolved.

"We see a lot of this test-for-cure at our hospital. However, testing for cure is not recommended in the guidelines and should not be done in most cases," Dr. Dominguez emphasized.

He reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES CONFERENCE

Pearls in clinical diagnosis of pertussis

VAIL, COLO. – One of the most useful signs that a young infant with an afebrile coughing illness has pertussis is the combination of an elevated white blood cell count of 20,000 cells/mcL or more plus a lymphocyte count of at least 10,000 cells/mcL.

"This is a pediatric pearl. It’s really a poor man’s way of diagnosing pertussis. It’s an effect of the pertussis toxin spreading throughout the neonate’s body, causing a very high white cell count with absolute lymphocytosis," Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

This clinical pearl is part of a highly useful algorithm put forth by the Global Pertussis Initiative in an effort to update and standardize the case definitions of pertussis. Existing case definitions were developed more than 40 years ago and have numerous shortcomings.

The group developed a three-pronged, age-based algorithm, reflecting an understanding that the key manifestations of pertussis are different in infants aged 0-3 months, children aged 4 months to 9 years, and adolescents or adults.

According to the algorithm, the presence of an elevated WBC count with absolute lymphocytosis in an infant up to 3 months old with an afebrile illness and a cough of less than 3 weeks’ duration that’s increasing in frequency and severity is "virtually diagnostic" of pertussis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1756-64).

Another key feature of pertussis – and this one applies across the age spectrum, from infants to adults – is that the coryza remains watery and doesn’t become purulent, unlike in most viral respiratory infections.

"That green snotty nose doesn’t usually happen when kids have pertussis," explained Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Similarly, in patients of all ages the pertussis cough, even as it worsens, does not become truly productive.

To help nail down the diagnosis of pertussis in infants, the key question to ask parents is, "Is there an adult or adolescent in your family who’s had the most severe cough in their life?" Most infants with pertussis will have had close exposure to an older family member with a prolonged afebrile coughing illness, Dr. Nyquist noted.

In the 4-month to 9-year-old age group, the cough becomes more paroxysmal. The key indicators of pertussis in this age group, according to the Global Pertussis Initiative algorithm, are worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough of at least 7 days’ duration in an afebrile child with nonpurulent coryza.

This same triad – worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough, afebrile illness, and nonpurulent coryza – also has high sensitivity and good specificity for the clinical diagnosis of pertussis in adolescents and adults. In addition, the algorithm highlights another useful clue to the diagnosis in patients in this age range: the occurrence of sweating episodes between coughing paroxysms.

In terms of laboratory diagnostics, real-time PCR and culture of nasopharyngeal mucus are most useful in the first 3 weeks after illness onset. Serology is a challenge because the results are influenced by the effects of vaccination; it shouldn’t be used to diagnose pertussis within 1 year following inoculation with any pertussis vaccine because it’s impossible to tell if a positive result represents a response to the vaccine or to infection.

Also, serology can’t distinguish between Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis infection. Most PCR tests can. It’s an important distinction because B. parapertussis turns out to be the pathogen in roughly 15% of cases of coughing illnesses similar to pertussis. B. parapertussis infection isn’t vaccine preventable, and its treatment hasn’t been well studied.

The expert consensus is that direct fluorescent antibody testing should be discouraged as a tool to diagnose pertussis because of its unreliable sensitivity and specificity. IgG anti–pertussis toxin ELISA testing is superior to IgA anti–pertussis toxin ELISA, which has a high false-negative rate, Dr. Nyquist observed.

She reported having no financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – One of the most useful signs that a young infant with an afebrile coughing illness has pertussis is the combination of an elevated white blood cell count of 20,000 cells/mcL or more plus a lymphocyte count of at least 10,000 cells/mcL.

"This is a pediatric pearl. It’s really a poor man’s way of diagnosing pertussis. It’s an effect of the pertussis toxin spreading throughout the neonate’s body, causing a very high white cell count with absolute lymphocytosis," Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

This clinical pearl is part of a highly useful algorithm put forth by the Global Pertussis Initiative in an effort to update and standardize the case definitions of pertussis. Existing case definitions were developed more than 40 years ago and have numerous shortcomings.

The group developed a three-pronged, age-based algorithm, reflecting an understanding that the key manifestations of pertussis are different in infants aged 0-3 months, children aged 4 months to 9 years, and adolescents or adults.

According to the algorithm, the presence of an elevated WBC count with absolute lymphocytosis in an infant up to 3 months old with an afebrile illness and a cough of less than 3 weeks’ duration that’s increasing in frequency and severity is "virtually diagnostic" of pertussis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1756-64).

Another key feature of pertussis – and this one applies across the age spectrum, from infants to adults – is that the coryza remains watery and doesn’t become purulent, unlike in most viral respiratory infections.

"That green snotty nose doesn’t usually happen when kids have pertussis," explained Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Similarly, in patients of all ages the pertussis cough, even as it worsens, does not become truly productive.

To help nail down the diagnosis of pertussis in infants, the key question to ask parents is, "Is there an adult or adolescent in your family who’s had the most severe cough in their life?" Most infants with pertussis will have had close exposure to an older family member with a prolonged afebrile coughing illness, Dr. Nyquist noted.

In the 4-month to 9-year-old age group, the cough becomes more paroxysmal. The key indicators of pertussis in this age group, according to the Global Pertussis Initiative algorithm, are worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough of at least 7 days’ duration in an afebrile child with nonpurulent coryza.

This same triad – worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough, afebrile illness, and nonpurulent coryza – also has high sensitivity and good specificity for the clinical diagnosis of pertussis in adolescents and adults. In addition, the algorithm highlights another useful clue to the diagnosis in patients in this age range: the occurrence of sweating episodes between coughing paroxysms.

In terms of laboratory diagnostics, real-time PCR and culture of nasopharyngeal mucus are most useful in the first 3 weeks after illness onset. Serology is a challenge because the results are influenced by the effects of vaccination; it shouldn’t be used to diagnose pertussis within 1 year following inoculation with any pertussis vaccine because it’s impossible to tell if a positive result represents a response to the vaccine or to infection.

Also, serology can’t distinguish between Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis infection. Most PCR tests can. It’s an important distinction because B. parapertussis turns out to be the pathogen in roughly 15% of cases of coughing illnesses similar to pertussis. B. parapertussis infection isn’t vaccine preventable, and its treatment hasn’t been well studied.

The expert consensus is that direct fluorescent antibody testing should be discouraged as a tool to diagnose pertussis because of its unreliable sensitivity and specificity. IgG anti–pertussis toxin ELISA testing is superior to IgA anti–pertussis toxin ELISA, which has a high false-negative rate, Dr. Nyquist observed.

She reported having no financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – One of the most useful signs that a young infant with an afebrile coughing illness has pertussis is the combination of an elevated white blood cell count of 20,000 cells/mcL or more plus a lymphocyte count of at least 10,000 cells/mcL.

"This is a pediatric pearl. It’s really a poor man’s way of diagnosing pertussis. It’s an effect of the pertussis toxin spreading throughout the neonate’s body, causing a very high white cell count with absolute lymphocytosis," Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

This clinical pearl is part of a highly useful algorithm put forth by the Global Pertussis Initiative in an effort to update and standardize the case definitions of pertussis. Existing case definitions were developed more than 40 years ago and have numerous shortcomings.

The group developed a three-pronged, age-based algorithm, reflecting an understanding that the key manifestations of pertussis are different in infants aged 0-3 months, children aged 4 months to 9 years, and adolescents or adults.

According to the algorithm, the presence of an elevated WBC count with absolute lymphocytosis in an infant up to 3 months old with an afebrile illness and a cough of less than 3 weeks’ duration that’s increasing in frequency and severity is "virtually diagnostic" of pertussis (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:1756-64).

Another key feature of pertussis – and this one applies across the age spectrum, from infants to adults – is that the coryza remains watery and doesn’t become purulent, unlike in most viral respiratory infections.

"That green snotty nose doesn’t usually happen when kids have pertussis," explained Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

Similarly, in patients of all ages the pertussis cough, even as it worsens, does not become truly productive.

To help nail down the diagnosis of pertussis in infants, the key question to ask parents is, "Is there an adult or adolescent in your family who’s had the most severe cough in their life?" Most infants with pertussis will have had close exposure to an older family member with a prolonged afebrile coughing illness, Dr. Nyquist noted.

In the 4-month to 9-year-old age group, the cough becomes more paroxysmal. The key indicators of pertussis in this age group, according to the Global Pertussis Initiative algorithm, are worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough of at least 7 days’ duration in an afebrile child with nonpurulent coryza.

This same triad – worsening paroxysmal nonproductive cough, afebrile illness, and nonpurulent coryza – also has high sensitivity and good specificity for the clinical diagnosis of pertussis in adolescents and adults. In addition, the algorithm highlights another useful clue to the diagnosis in patients in this age range: the occurrence of sweating episodes between coughing paroxysms.

In terms of laboratory diagnostics, real-time PCR and culture of nasopharyngeal mucus are most useful in the first 3 weeks after illness onset. Serology is a challenge because the results are influenced by the effects of vaccination; it shouldn’t be used to diagnose pertussis within 1 year following inoculation with any pertussis vaccine because it’s impossible to tell if a positive result represents a response to the vaccine or to infection.

Also, serology can’t distinguish between Bordetella pertussis and B. parapertussis infection. Most PCR tests can. It’s an important distinction because B. parapertussis turns out to be the pathogen in roughly 15% of cases of coughing illnesses similar to pertussis. B. parapertussis infection isn’t vaccine preventable, and its treatment hasn’t been well studied.

The expert consensus is that direct fluorescent antibody testing should be discouraged as a tool to diagnose pertussis because of its unreliable sensitivity and specificity. IgG anti–pertussis toxin ELISA testing is superior to IgA anti–pertussis toxin ELISA, which has a high false-negative rate, Dr. Nyquist observed.

She reported having no financial relationships with any commercial interests.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES CONFERENCE

A call for new pertussis vaccines

VAIL, COLO. – Development of a better pertussis vaccine has emerged as a pressing need in light of persuasive evidence of waning immunity to current vaccines.

But can it be done? Can a new vaccine be created that provides enhanced efficacy and longer-lasting immunity without increasing reactogenicity?

"I think it can be done," Dr. Myron J. Levin said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"The question you might ask is, can we do a better job than nature? After all, pertussis infection doesn’t cause lasting immunity, so could we do a better job than nature? I think so. And here’s an example: We know that antibody is protective against HPV [human papillomavirus], and that the HPV vaccine gives a much stronger antibody response, often by 100-fold, than does natural infection with HPV," observed Dr. Levin, who led development of the shingles vaccine.

Convincing evidence of waning immunity to the current five-dose diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine series completed before age 7 years in the United States comes from research conducted at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, Calif. The investigators analyzed the large California pertussis outbreak of 2010. Their case-control study showed that the protection provided by the DTaP vaccine was short-lived, such that each year after completing the fifth dose the likelihood of developing PCR-proven pertussis climbed by an average of 42% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1012-9).

Thus, they calculated that if the initial effectiveness of DTaP was 90%, it would drop to a mere 42% 5 years after the fifth and final dose. In addition, there is a strong argument that the original estimate of the vaccine’s efficacy of about 85% was inflated due to the case definition used. The efficacy rate after 5 years becomes disturbingly low if the actual efficacy rate was roughly 7%, as many now believe, noted Dr. Levin, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The whole-cell pertussis vaccines were clearly more effective than the DTaP, which began replacing them in the early 1990s. In another Kaiser Permanente study that zeroed in on the transition period between the use of whole-cell pertussis vaccine and DTaP, patients who contracted PCR-confirmed pertussis did so an average of 14.7 years after receiving their last dose in the series if they received one or more doses of whole-cell vaccine compared with a mere 5.6 years after the last dose if they got the all-DTaP series.

The national switch to DTaP was carried out because the vaccine has fewer adverse effects than does the whole-cell pertussis vaccine. Components of whole-cell vaccines, including lipopolysaccharides and internal proteins, were important in signaling the innate immune system to shape a more robust response. Unfortunately, these whole-cell vaccine components also trigger unwanted reactogenic local and systemic effects.

"Whenever a vaccine is cleaned up to decrease side effects, there is a great likelihood that the efficacy will be affected. This is almost certainly the case with acellular pertussis, and probably with the split-product flu vaccines as well. I would say we need to learn why the whole-cell pertussis vaccine was so effective – which component was most important in directing the immune response – and see if we can separate that from the side effects. This is a research issue," said Dr. Levin.

Possible ways to create a better DTaP vaccine might involve incorporating a detoxified lipopolysaccharide or adding additional adjuvants to increase the innate immune response to the pertussis antigen.

Vaccine development takes time. In the interim, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has taken steps to deal with the nation’s worsening pertussis epidemic outbreak. Because the herd protection effect is probably low, a "cocooning" strategy has been adopted. This involves targeted immunization of pregnant women and all close contacts of their babies during the first year of life, when pertussis has its highest morbidity and mortality. In addition, an adolescent dose of pertussis vaccine has been introduced. And consideration is being given to the possibility of universal once-per-decade booster doses in adults, but this has thus far been rejected as not being cost-effective.

Dr. Levin reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline and royalties as well as honoraria from Merck, Sharpe, and Dohme.

VAIL, COLO. – Development of a better pertussis vaccine has emerged as a pressing need in light of persuasive evidence of waning immunity to current vaccines.

But can it be done? Can a new vaccine be created that provides enhanced efficacy and longer-lasting immunity without increasing reactogenicity?

"I think it can be done," Dr. Myron J. Levin said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"The question you might ask is, can we do a better job than nature? After all, pertussis infection doesn’t cause lasting immunity, so could we do a better job than nature? I think so. And here’s an example: We know that antibody is protective against HPV [human papillomavirus], and that the HPV vaccine gives a much stronger antibody response, often by 100-fold, than does natural infection with HPV," observed Dr. Levin, who led development of the shingles vaccine.

Convincing evidence of waning immunity to the current five-dose diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine series completed before age 7 years in the United States comes from research conducted at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, Calif. The investigators analyzed the large California pertussis outbreak of 2010. Their case-control study showed that the protection provided by the DTaP vaccine was short-lived, such that each year after completing the fifth dose the likelihood of developing PCR-proven pertussis climbed by an average of 42% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1012-9).

Thus, they calculated that if the initial effectiveness of DTaP was 90%, it would drop to a mere 42% 5 years after the fifth and final dose. In addition, there is a strong argument that the original estimate of the vaccine’s efficacy of about 85% was inflated due to the case definition used. The efficacy rate after 5 years becomes disturbingly low if the actual efficacy rate was roughly 7%, as many now believe, noted Dr. Levin, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The whole-cell pertussis vaccines were clearly more effective than the DTaP, which began replacing them in the early 1990s. In another Kaiser Permanente study that zeroed in on the transition period between the use of whole-cell pertussis vaccine and DTaP, patients who contracted PCR-confirmed pertussis did so an average of 14.7 years after receiving their last dose in the series if they received one or more doses of whole-cell vaccine compared with a mere 5.6 years after the last dose if they got the all-DTaP series.

The national switch to DTaP was carried out because the vaccine has fewer adverse effects than does the whole-cell pertussis vaccine. Components of whole-cell vaccines, including lipopolysaccharides and internal proteins, were important in signaling the innate immune system to shape a more robust response. Unfortunately, these whole-cell vaccine components also trigger unwanted reactogenic local and systemic effects.

"Whenever a vaccine is cleaned up to decrease side effects, there is a great likelihood that the efficacy will be affected. This is almost certainly the case with acellular pertussis, and probably with the split-product flu vaccines as well. I would say we need to learn why the whole-cell pertussis vaccine was so effective – which component was most important in directing the immune response – and see if we can separate that from the side effects. This is a research issue," said Dr. Levin.

Possible ways to create a better DTaP vaccine might involve incorporating a detoxified lipopolysaccharide or adding additional adjuvants to increase the innate immune response to the pertussis antigen.

Vaccine development takes time. In the interim, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has taken steps to deal with the nation’s worsening pertussis epidemic outbreak. Because the herd protection effect is probably low, a "cocooning" strategy has been adopted. This involves targeted immunization of pregnant women and all close contacts of their babies during the first year of life, when pertussis has its highest morbidity and mortality. In addition, an adolescent dose of pertussis vaccine has been introduced. And consideration is being given to the possibility of universal once-per-decade booster doses in adults, but this has thus far been rejected as not being cost-effective.

Dr. Levin reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline and royalties as well as honoraria from Merck, Sharpe, and Dohme.

VAIL, COLO. – Development of a better pertussis vaccine has emerged as a pressing need in light of persuasive evidence of waning immunity to current vaccines.

But can it be done? Can a new vaccine be created that provides enhanced efficacy and longer-lasting immunity without increasing reactogenicity?

"I think it can be done," Dr. Myron J. Levin said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"The question you might ask is, can we do a better job than nature? After all, pertussis infection doesn’t cause lasting immunity, so could we do a better job than nature? I think so. And here’s an example: We know that antibody is protective against HPV [human papillomavirus], and that the HPV vaccine gives a much stronger antibody response, often by 100-fold, than does natural infection with HPV," observed Dr. Levin, who led development of the shingles vaccine.

Convincing evidence of waning immunity to the current five-dose diphtheria, tetanus, and acellular pertussis (DTaP) vaccine series completed before age 7 years in the United States comes from research conducted at the Kaiser Permanente Vaccine Study Center in Oakland, Calif. The investigators analyzed the large California pertussis outbreak of 2010. Their case-control study showed that the protection provided by the DTaP vaccine was short-lived, such that each year after completing the fifth dose the likelihood of developing PCR-proven pertussis climbed by an average of 42% (N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;367:1012-9).

Thus, they calculated that if the initial effectiveness of DTaP was 90%, it would drop to a mere 42% 5 years after the fifth and final dose. In addition, there is a strong argument that the original estimate of the vaccine’s efficacy of about 85% was inflated due to the case definition used. The efficacy rate after 5 years becomes disturbingly low if the actual efficacy rate was roughly 7%, as many now believe, noted Dr. Levin, professor of pediatrics and medicine at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The whole-cell pertussis vaccines were clearly more effective than the DTaP, which began replacing them in the early 1990s. In another Kaiser Permanente study that zeroed in on the transition period between the use of whole-cell pertussis vaccine and DTaP, patients who contracted PCR-confirmed pertussis did so an average of 14.7 years after receiving their last dose in the series if they received one or more doses of whole-cell vaccine compared with a mere 5.6 years after the last dose if they got the all-DTaP series.

The national switch to DTaP was carried out because the vaccine has fewer adverse effects than does the whole-cell pertussis vaccine. Components of whole-cell vaccines, including lipopolysaccharides and internal proteins, were important in signaling the innate immune system to shape a more robust response. Unfortunately, these whole-cell vaccine components also trigger unwanted reactogenic local and systemic effects.

"Whenever a vaccine is cleaned up to decrease side effects, there is a great likelihood that the efficacy will be affected. This is almost certainly the case with acellular pertussis, and probably with the split-product flu vaccines as well. I would say we need to learn why the whole-cell pertussis vaccine was so effective – which component was most important in directing the immune response – and see if we can separate that from the side effects. This is a research issue," said Dr. Levin.

Possible ways to create a better DTaP vaccine might involve incorporating a detoxified lipopolysaccharide or adding additional adjuvants to increase the innate immune response to the pertussis antigen.

Vaccine development takes time. In the interim, the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has taken steps to deal with the nation’s worsening pertussis epidemic outbreak. Because the herd protection effect is probably low, a "cocooning" strategy has been adopted. This involves targeted immunization of pregnant women and all close contacts of their babies during the first year of life, when pertussis has its highest morbidity and mortality. In addition, an adolescent dose of pertussis vaccine has been introduced. And consideration is being given to the possibility of universal once-per-decade booster doses in adults, but this has thus far been rejected as not being cost-effective.

Dr. Levin reported receiving honoraria from Novartis and GlaxoSmithKline and royalties as well as honoraria from Merck, Sharpe, and Dohme.

EXPERT ANALYSIS FROM THE ANNUAL PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES CONFERENCE

'But I'm vaccinated!': Why chemoprophylaxis is needed after pertussis exposure

VAIL, COLO. – It’s a question hospital infection control officers field from physicians and other health care personnel every time a pertussis exposure occurs: "I’ve been vaccinated, so why do I have to get a course of azithromycin for postexposure prophylaxis?"

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) based its updated recommendation for antibiotic postexposure prophylaxis on the findings of a randomized trial known as the Vanderbilt Study. The results, while nondefinitive, suggested that a policy of watchful waiting with daily symptom monitoring for 21 days post exposure may not be as effective as azithromycin postexposure prophylaxis in preventing pertussis infection, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist explained at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The ACIP recommendation is for antibiotic prophylaxis for all pertussis-exposed health care workers likely to secondarily expose high-risk patients, such as neonates and pregnant women. Other vaccinated health care workers could receive either postexposure prophylaxis or 21 days of symptom monitoring with prompt antimicrobial therapy to be started should pertussis symptoms arise.

For Dr. Nyquist, the issue is a no-brainer. The vaccine is not 100% protective, the duration of protection is uncertain, and the adverse impact of a pertussis outbreak in a health care facility is enormous.

"When I put on my hospital epidemiologist hat and I think about pertussis in my hospital, it scares me to death. I would give everyone I was concerned about 5 days of azithromycin at $60 a pop," said Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The children’s hospital affiliated with Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., has a universal tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization policy for all health care personnel. So it was an ideal location for a randomized comparison of two strategies to prevent infection following pertussis exposure in vaccinated physicians, nurses, and other health care personnel.

Following a pertussis exposure, health care personnel were randomized to 5 days of azithromycin or 21 days of watchful waiting. A bona fide exposure typically involved face-to-face exposure within a few feet when the health care provider wasn’t wearing a mask, or ungloved contact with a patient’s secretions.

Although 1,091 health care personnel enrolled in the trial, during a 30-month period only 86 subjects were randomized, limiting the statistical power of the findings. The key result: Only 1 of 42 patients who received postexposure prophylaxis met the prespecified definition of pertussis, compared with 6 of 44 in the watchful waiting group.

However, pertussis infection was defined quite strictly as a positive culture or PCR, a twofold increase in anti–pertussis toxin titer, or a single anti–pertussis toxin titer of at least 94 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units per milliliter. In fact, not a single study participant developed symptomatic pertussis, and the investigators concluded that "it is likely that none of the health care personnel who met the predefined serologic or PCR for infection were truly infected with pertussis" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:938-45).

Dr. Nyquist noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified health care workers as being at the epicenter of numerous pertussis outbreaks in hospitals. Health care personnel have regular contact with infected patients, and as adults they have waning immunity. The cost per hospital outbreak was calculated by the CDC at $44,000-$75,000.

"But that figure doesn’t include the human pain and suffering, which I would multiply maybe times five," she added.

ACIP recommends that all health care personnel with direct patient contact in hospitals or ambulatory settings receive a single dose of Tdap. In addition, at its June meeting ACIP directed the Pertussis Vaccines Work Group to explore the possibility of giving a booster dose of Tdap to health care workers in order to beef up their protection.

Dr. Nyquist reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – It’s a question hospital infection control officers field from physicians and other health care personnel every time a pertussis exposure occurs: "I’ve been vaccinated, so why do I have to get a course of azithromycin for postexposure prophylaxis?"

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) based its updated recommendation for antibiotic postexposure prophylaxis on the findings of a randomized trial known as the Vanderbilt Study. The results, while nondefinitive, suggested that a policy of watchful waiting with daily symptom monitoring for 21 days post exposure may not be as effective as azithromycin postexposure prophylaxis in preventing pertussis infection, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist explained at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The ACIP recommendation is for antibiotic prophylaxis for all pertussis-exposed health care workers likely to secondarily expose high-risk patients, such as neonates and pregnant women. Other vaccinated health care workers could receive either postexposure prophylaxis or 21 days of symptom monitoring with prompt antimicrobial therapy to be started should pertussis symptoms arise.

For Dr. Nyquist, the issue is a no-brainer. The vaccine is not 100% protective, the duration of protection is uncertain, and the adverse impact of a pertussis outbreak in a health care facility is enormous.

"When I put on my hospital epidemiologist hat and I think about pertussis in my hospital, it scares me to death. I would give everyone I was concerned about 5 days of azithromycin at $60 a pop," said Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The children’s hospital affiliated with Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., has a universal tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization policy for all health care personnel. So it was an ideal location for a randomized comparison of two strategies to prevent infection following pertussis exposure in vaccinated physicians, nurses, and other health care personnel.

Following a pertussis exposure, health care personnel were randomized to 5 days of azithromycin or 21 days of watchful waiting. A bona fide exposure typically involved face-to-face exposure within a few feet when the health care provider wasn’t wearing a mask, or ungloved contact with a patient’s secretions.

Although 1,091 health care personnel enrolled in the trial, during a 30-month period only 86 subjects were randomized, limiting the statistical power of the findings. The key result: Only 1 of 42 patients who received postexposure prophylaxis met the prespecified definition of pertussis, compared with 6 of 44 in the watchful waiting group.

However, pertussis infection was defined quite strictly as a positive culture or PCR, a twofold increase in anti–pertussis toxin titer, or a single anti–pertussis toxin titer of at least 94 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units per milliliter. In fact, not a single study participant developed symptomatic pertussis, and the investigators concluded that "it is likely that none of the health care personnel who met the predefined serologic or PCR for infection were truly infected with pertussis" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:938-45).

Dr. Nyquist noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified health care workers as being at the epicenter of numerous pertussis outbreaks in hospitals. Health care personnel have regular contact with infected patients, and as adults they have waning immunity. The cost per hospital outbreak was calculated by the CDC at $44,000-$75,000.

"But that figure doesn’t include the human pain and suffering, which I would multiply maybe times five," she added.

ACIP recommends that all health care personnel with direct patient contact in hospitals or ambulatory settings receive a single dose of Tdap. In addition, at its June meeting ACIP directed the Pertussis Vaccines Work Group to explore the possibility of giving a booster dose of Tdap to health care workers in order to beef up their protection.

Dr. Nyquist reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

VAIL, COLO. – It’s a question hospital infection control officers field from physicians and other health care personnel every time a pertussis exposure occurs: "I’ve been vaccinated, so why do I have to get a course of azithromycin for postexposure prophylaxis?"

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) based its updated recommendation for antibiotic postexposure prophylaxis on the findings of a randomized trial known as the Vanderbilt Study. The results, while nondefinitive, suggested that a policy of watchful waiting with daily symptom monitoring for 21 days post exposure may not be as effective as azithromycin postexposure prophylaxis in preventing pertussis infection, Dr. Ann-Christine Nyquist explained at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The ACIP recommendation is for antibiotic prophylaxis for all pertussis-exposed health care workers likely to secondarily expose high-risk patients, such as neonates and pregnant women. Other vaccinated health care workers could receive either postexposure prophylaxis or 21 days of symptom monitoring with prompt antimicrobial therapy to be started should pertussis symptoms arise.

For Dr. Nyquist, the issue is a no-brainer. The vaccine is not 100% protective, the duration of protection is uncertain, and the adverse impact of a pertussis outbreak in a health care facility is enormous.

"When I put on my hospital epidemiologist hat and I think about pertussis in my hospital, it scares me to death. I would give everyone I was concerned about 5 days of azithromycin at $60 a pop," said Dr. Nyquist, professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

The children’s hospital affiliated with Vanderbilt University, Nashville, Tenn., has a universal tetanus-diphtheria-acellular pertussis (Tdap) vaccine immunization policy for all health care personnel. So it was an ideal location for a randomized comparison of two strategies to prevent infection following pertussis exposure in vaccinated physicians, nurses, and other health care personnel.

Following a pertussis exposure, health care personnel were randomized to 5 days of azithromycin or 21 days of watchful waiting. A bona fide exposure typically involved face-to-face exposure within a few feet when the health care provider wasn’t wearing a mask, or ungloved contact with a patient’s secretions.

Although 1,091 health care personnel enrolled in the trial, during a 30-month period only 86 subjects were randomized, limiting the statistical power of the findings. The key result: Only 1 of 42 patients who received postexposure prophylaxis met the prespecified definition of pertussis, compared with 6 of 44 in the watchful waiting group.

However, pertussis infection was defined quite strictly as a positive culture or PCR, a twofold increase in anti–pertussis toxin titer, or a single anti–pertussis toxin titer of at least 94 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay units per milliliter. In fact, not a single study participant developed symptomatic pertussis, and the investigators concluded that "it is likely that none of the health care personnel who met the predefined serologic or PCR for infection were truly infected with pertussis" (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:938-45).

Dr. Nyquist noted that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) has identified health care workers as being at the epicenter of numerous pertussis outbreaks in hospitals. Health care personnel have regular contact with infected patients, and as adults they have waning immunity. The cost per hospital outbreak was calculated by the CDC at $44,000-$75,000.

"But that figure doesn’t include the human pain and suffering, which I would multiply maybe times five," she added.

ACIP recommends that all health care personnel with direct patient contact in hospitals or ambulatory settings receive a single dose of Tdap. In addition, at its June meeting ACIP directed the Pertussis Vaccines Work Group to explore the possibility of giving a booster dose of Tdap to health care workers in order to beef up their protection.

Dr. Nyquist reported having no relevant financial relationships with any commercial interests.

EXPERT OPINION FROM THE ANNUAL PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES CONFERENCE

Novel risk factors for serious RSV identified

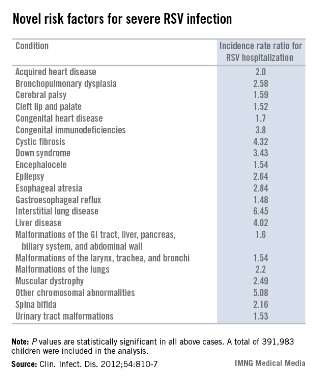

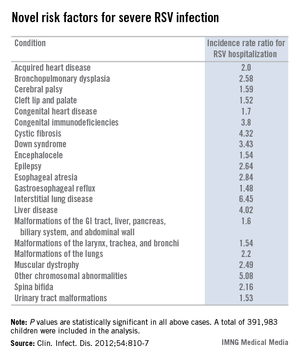

VAIL, COLO. – Children with congenital malformations or a variety of chronic diseases are at a previously undescribed, sharply increased risk for serious respiratory syncytial virus infection, according to a landmark Danish study.

Among the newly identified risk factors for hospitalization for RSV infection are neuromuscular disease, interstitial lung disease, liver disease, congenital malformations, liver disease, and congenital immunodeficiencies, Dr. Eric A.F. Simões said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"When you are fighting with an insurance company over whether treatment with palivizumab is appropriate, you can show them this study. It’s the only one of its kind," said Dr. Simões, a coauthor of the Danish study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

This was a population-based cohort study including 391,983 children born in Denmark during 1997-2003. Dr. Simões and his coinvestigators utilized the comprehensive Danish National Patient Registry to determine that 2.7% of the children carried a diagnosis for one or more chronic diseases, a broad heading which included congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, and acquired chronic disorders.

During their first 23 months of life, 2.8% of the study population was hospitalized for an RSV infection. Of those hospitalized children, 8.8% had at least one diagnosis of chronic disease. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal smoking, prematurity, hospitalization within the last 30 days, and other potential confounding factors, the incidence rate ratio for RSV hospitalization in children with any congenital chronic condition was 2.18. For children with any acquired chronic condition, it was 2.25. (See chart.)

Dr. Simoes and his colleagues put forth biologically plausible mechanistic explanations for the increased risks of severe RSV in many of the newly identified at-risk subgroups. For example, they argued that children with cleft lip and palate are known to have a high incidence of middle ear disease, and it’s possible that difficulties in swallowing could result in aspiration of infected nasal secretions, with resultant lower respiratory tract RSV infection.

Children with various neuromuscular diseases were found to be at increased risk for RSV hospitalization. These included children with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida or other congenital malformations of the nervous system. Moreover, children with neuromuscular disease also had significantly longer-than-average RSV hospitalizations. It’s possible that the increased RSV morbidity seen in these patients was due at least in part to diminished vital capacity secondary to muscular dysfunction, coupled with disrupted clearance of respiratory secretions, the investigators speculated.

The finding of an elevated risk of RSV hospitalization among children with malformations of the urinary system might be explained as follows: Lower urinary tract obstruction results in oligohydramnios, in turn resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia.

The 4.32-fold increased risk of severe RSV infection documented in this study in children with cystic fibrosis may be related to the reduced levels of surfactant proteins A and D, which characterize this disease. Those proteins are key components of the pulmonary innate immune system, Dr. Simões and his coworkers noted (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:810-7).

In contrast, the finding of a fourfold increased risk of RSV hospitalization in children with liver disease was unexpected, and the investigators had no explanation for it.

The Danish study was supported by Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Simões has received research grants from and served as a consultant to Abbott and half a dozen other companies, as well as UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Health Organization.

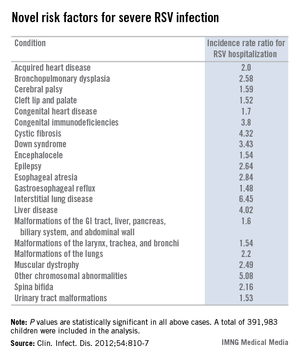

VAIL, COLO. – Children with congenital malformations or a variety of chronic diseases are at a previously undescribed, sharply increased risk for serious respiratory syncytial virus infection, according to a landmark Danish study.

Among the newly identified risk factors for hospitalization for RSV infection are neuromuscular disease, interstitial lung disease, liver disease, congenital malformations, liver disease, and congenital immunodeficiencies, Dr. Eric A.F. Simões said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"When you are fighting with an insurance company over whether treatment with palivizumab is appropriate, you can show them this study. It’s the only one of its kind," said Dr. Simões, a coauthor of the Danish study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

This was a population-based cohort study including 391,983 children born in Denmark during 1997-2003. Dr. Simões and his coinvestigators utilized the comprehensive Danish National Patient Registry to determine that 2.7% of the children carried a diagnosis for one or more chronic diseases, a broad heading which included congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, and acquired chronic disorders.

During their first 23 months of life, 2.8% of the study population was hospitalized for an RSV infection. Of those hospitalized children, 8.8% had at least one diagnosis of chronic disease. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal smoking, prematurity, hospitalization within the last 30 days, and other potential confounding factors, the incidence rate ratio for RSV hospitalization in children with any congenital chronic condition was 2.18. For children with any acquired chronic condition, it was 2.25. (See chart.)

Dr. Simoes and his colleagues put forth biologically plausible mechanistic explanations for the increased risks of severe RSV in many of the newly identified at-risk subgroups. For example, they argued that children with cleft lip and palate are known to have a high incidence of middle ear disease, and it’s possible that difficulties in swallowing could result in aspiration of infected nasal secretions, with resultant lower respiratory tract RSV infection.

Children with various neuromuscular diseases were found to be at increased risk for RSV hospitalization. These included children with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida or other congenital malformations of the nervous system. Moreover, children with neuromuscular disease also had significantly longer-than-average RSV hospitalizations. It’s possible that the increased RSV morbidity seen in these patients was due at least in part to diminished vital capacity secondary to muscular dysfunction, coupled with disrupted clearance of respiratory secretions, the investigators speculated.

The finding of an elevated risk of RSV hospitalization among children with malformations of the urinary system might be explained as follows: Lower urinary tract obstruction results in oligohydramnios, in turn resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia.

The 4.32-fold increased risk of severe RSV infection documented in this study in children with cystic fibrosis may be related to the reduced levels of surfactant proteins A and D, which characterize this disease. Those proteins are key components of the pulmonary innate immune system, Dr. Simões and his coworkers noted (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:810-7).

In contrast, the finding of a fourfold increased risk of RSV hospitalization in children with liver disease was unexpected, and the investigators had no explanation for it.

The Danish study was supported by Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Simões has received research grants from and served as a consultant to Abbott and half a dozen other companies, as well as UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Health Organization.

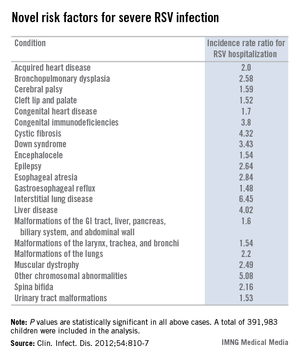

VAIL, COLO. – Children with congenital malformations or a variety of chronic diseases are at a previously undescribed, sharply increased risk for serious respiratory syncytial virus infection, according to a landmark Danish study.

Among the newly identified risk factors for hospitalization for RSV infection are neuromuscular disease, interstitial lung disease, liver disease, congenital malformations, liver disease, and congenital immunodeficiencies, Dr. Eric A.F. Simões said at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

"When you are fighting with an insurance company over whether treatment with palivizumab is appropriate, you can show them this study. It’s the only one of its kind," said Dr. Simões, a coauthor of the Danish study and professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

This was a population-based cohort study including 391,983 children born in Denmark during 1997-2003. Dr. Simões and his coinvestigators utilized the comprehensive Danish National Patient Registry to determine that 2.7% of the children carried a diagnosis for one or more chronic diseases, a broad heading which included congenital malformations, chromosomal abnormalities, and acquired chronic disorders.

During their first 23 months of life, 2.8% of the study population was hospitalized for an RSV infection. Of those hospitalized children, 8.8% had at least one diagnosis of chronic disease. In a multivariate analysis adjusted for maternal smoking, prematurity, hospitalization within the last 30 days, and other potential confounding factors, the incidence rate ratio for RSV hospitalization in children with any congenital chronic condition was 2.18. For children with any acquired chronic condition, it was 2.25. (See chart.)

Dr. Simoes and his colleagues put forth biologically plausible mechanistic explanations for the increased risks of severe RSV in many of the newly identified at-risk subgroups. For example, they argued that children with cleft lip and palate are known to have a high incidence of middle ear disease, and it’s possible that difficulties in swallowing could result in aspiration of infected nasal secretions, with resultant lower respiratory tract RSV infection.

Children with various neuromuscular diseases were found to be at increased risk for RSV hospitalization. These included children with epilepsy, cerebral palsy, muscular dystrophy, and spina bifida or other congenital malformations of the nervous system. Moreover, children with neuromuscular disease also had significantly longer-than-average RSV hospitalizations. It’s possible that the increased RSV morbidity seen in these patients was due at least in part to diminished vital capacity secondary to muscular dysfunction, coupled with disrupted clearance of respiratory secretions, the investigators speculated.

The finding of an elevated risk of RSV hospitalization among children with malformations of the urinary system might be explained as follows: Lower urinary tract obstruction results in oligohydramnios, in turn resulting in pulmonary hypoplasia.

The 4.32-fold increased risk of severe RSV infection documented in this study in children with cystic fibrosis may be related to the reduced levels of surfactant proteins A and D, which characterize this disease. Those proteins are key components of the pulmonary innate immune system, Dr. Simões and his coworkers noted (Clin. Infect. Dis. 2012;54:810-7).

In contrast, the finding of a fourfold increased risk of RSV hospitalization in children with liver disease was unexpected, and the investigators had no explanation for it.

The Danish study was supported by Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Simões has received research grants from and served as a consultant to Abbott and half a dozen other companies, as well as UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Health Organization.

AT THE ANNUAL PEDIATRIC INFECTIOUS DISEASES CONFERENCE

Major finding: Children with congenital malformations, neuromuscular disease, interstitial lung disease, a variety of chromosomal abnormalities, acquired heart disease, and other chronic conditions are newly recognized as being at significantly increased risk for severe respiratory syncytial virus infection.

Data source: This was a Danish national population-based cohort study involving nearly 400,000 children born in Denmark during 1997-2003, of whom 2.8% were hospitalized for RSV before 24 months of age.

Disclosures: The Danish study was supported by Abbott Laboratories. Dr. Simões has received research grants from and served as a consultant to Abbott and half a dozen other companies, as well as UNICEF, the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation, and the World Health Organization.

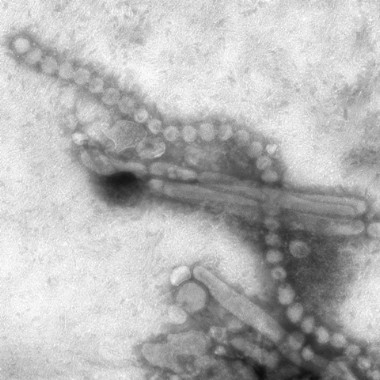

The push is on for universal influenza vaccines

VAIL, COLO. – A universal influenza vaccine is not a pipe dream.

"There is a really big push for this now. It’s a major goal," Dr. Wayne Sullender observed at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The impetus for development of a universal influenza vaccine is that influenza still poses a major public health threat despite the widespread availability of current vaccines. Worldwide, roughly 1.4 million children die of pneumonia each year, more than from malaria, AIDS, and measles combined. It has been estimated that each year up to 112,000 children under age 5 die of influenza-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection, with 99% of the deaths occurring in developing countries.

A universal influenza vaccine could render obsolete the current costly, time-consuming, and uncertainty-ridden process of reformulating flu vaccines from year to year based upon expert consensus as to what the epidemic strains are most likely to be in the next flu season. This is a guessing game, and vaccine efficacy is reduced in seasons where the match isn’t good.

Also, a universal vaccine could conceivably protect against highly pathogenic pandemic influenza viruses, such as the swine flu H3N2 or the even more lethal avian H7N9 influenza virus. And even if a universal influenza vaccine wasn’t fully protective against threatening pandemic strains, it could perhaps prime vaccine recipients so they are no longer immunologically naïve, explained Dr. Sullender, an infectious diseases expert who is a visiting professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

All of the universal flu vaccines in clinical development employ various highly conserved regions of influenza virus target antigens. In focusing on these targets shared by different influenza virus subtypes, the goal is to develop vaccines that protect against seasonal influenza, even as the viruses engage in their relentless antigenic shift and drift, as well as to provide immunity against emerging pandemic strains having the potential for rapid spread and high mortality throughout the world.

Among the novel strategies for development of a universal influenza vaccine being pursued in laboratories around the world, one of the most promising in Dr. Sullender’s view involves stimulation of anti-M2e antibodies. M2 is a proton-selective ion channel that plays a key role in virus assembly. M2 is found on the surface of virus-infected cells. Its advantage as an antigen is that its sequence is virtually the same in every influenza virus isolated since the 1930s. Natural infection doesn’t stimulate much of an antibody response to M2. Yet even though M2e antibodies are not virus-neutralizing, it appears they are able to kill influenza virus by other mechanisms.

Another active area involves antibody responses to highly conserved epitopes on hemagglutinin. A region of vulnerability has been identified in the stem region of hemagglutinin, the viral spike. If the amino acids in this stem antibody binding site prove to be so important to the structure of hemagglutinin that the virus can’t tolerate change there, then the virus wouldn’t be able to adapt to and mutate away from a vaccine targeting this site via stimulation of neutralizing antibodies. Such a vaccine could very well be a universal influenza vaccine.

In addition, a novel epitope has been identified on the globular head of the H1N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin. Investigators have isolated a human monoclonal antibody that recognizes this epitope and neutralizes many different H1N1 strains. This could eventually lead to production of vaccines that incorporate protection against the severe H1N1 flu.

With regard to the avian-origin H7N9 influenza A virus that emerged last winter in China, Dr. Sullender commented, "This one is pretty scary." First estimates are that one-third of people hospitalized with the infection died. However, less severe cases were probably underrecognized, and it’s unlikely the death rate will remain this high.

The human-to-human transmission rate of H7N9 is low. Still, there are several reasons for concern about this virus. Although the pathogenicity in birds is low, the virus appears to have enhanced replication and virulence in humans. And H7N9 is already resistant to amantadine. Moreover, cases of resistance to oseltamivir and zanamivir have been reported.

The potential for mayhem due to H7N9 is such that vaccine development efforts are already underway. Among infectious respiratory disease experts, all eyes are on the coming flu season in Asia and what role H7N9 will play.

"Time will tell whether this will be just another story that comes and goes with influenza, or it becomes a more long-lasting problem," he said.

Experts all agree that it’s not a matter of "if’" another worldwide, high-mortality flu pandemic such as the one that occurred after the end of World War I will happen, it’s simply a question of "when."

"It might occur in 5 years, or it might not happen during our lifetime," according to Dr. Sullender.

He reported receiving research funding from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and has no relevant financial relationships.

VAIL, COLO. – A universal influenza vaccine is not a pipe dream.

"There is a really big push for this now. It’s a major goal," Dr. Wayne Sullender observed at a conference on pediatric infectious diseases sponsored by the Children’s Hospital Colorado.

The impetus for development of a universal influenza vaccine is that influenza still poses a major public health threat despite the widespread availability of current vaccines. Worldwide, roughly 1.4 million children die of pneumonia each year, more than from malaria, AIDS, and measles combined. It has been estimated that each year up to 112,000 children under age 5 die of influenza-associated acute lower respiratory tract infection, with 99% of the deaths occurring in developing countries.

A universal influenza vaccine could render obsolete the current costly, time-consuming, and uncertainty-ridden process of reformulating flu vaccines from year to year based upon expert consensus as to what the epidemic strains are most likely to be in the next flu season. This is a guessing game, and vaccine efficacy is reduced in seasons where the match isn’t good.

Also, a universal vaccine could conceivably protect against highly pathogenic pandemic influenza viruses, such as the swine flu H3N2 or the even more lethal avian H7N9 influenza virus. And even if a universal influenza vaccine wasn’t fully protective against threatening pandemic strains, it could perhaps prime vaccine recipients so they are no longer immunologically naïve, explained Dr. Sullender, an infectious diseases expert who is a visiting professor of pediatrics at the University of Colorado, Denver.

All of the universal flu vaccines in clinical development employ various highly conserved regions of influenza virus target antigens. In focusing on these targets shared by different influenza virus subtypes, the goal is to develop vaccines that protect against seasonal influenza, even as the viruses engage in their relentless antigenic shift and drift, as well as to provide immunity against emerging pandemic strains having the potential for rapid spread and high mortality throughout the world.

Among the novel strategies for development of a universal influenza vaccine being pursued in laboratories around the world, one of the most promising in Dr. Sullender’s view involves stimulation of anti-M2e antibodies. M2 is a proton-selective ion channel that plays a key role in virus assembly. M2 is found on the surface of virus-infected cells. Its advantage as an antigen is that its sequence is virtually the same in every influenza virus isolated since the 1930s. Natural infection doesn’t stimulate much of an antibody response to M2. Yet even though M2e antibodies are not virus-neutralizing, it appears they are able to kill influenza virus by other mechanisms.

Another active area involves antibody responses to highly conserved epitopes on hemagglutinin. A region of vulnerability has been identified in the stem region of hemagglutinin, the viral spike. If the amino acids in this stem antibody binding site prove to be so important to the structure of hemagglutinin that the virus can’t tolerate change there, then the virus wouldn’t be able to adapt to and mutate away from a vaccine targeting this site via stimulation of neutralizing antibodies. Such a vaccine could very well be a universal influenza vaccine.

In addition, a novel epitope has been identified on the globular head of the H1N1 influenza virus hemagglutinin. Investigators have isolated a human monoclonal antibody that recognizes this epitope and neutralizes many different H1N1 strains. This could eventually lead to production of vaccines that incorporate protection against the severe H1N1 flu.

With regard to the avian-origin H7N9 influenza A virus that emerged last winter in China, Dr. Sullender commented, "This one is pretty scary." First estimates are that one-third of people hospitalized with the infection died. However, less severe cases were probably underrecognized, and it’s unlikely the death rate will remain this high.

The human-to-human transmission rate of H7N9 is low. Still, there are several reasons for concern about this virus. Although the pathogenicity in birds is low, the virus appears to have enhanced replication and virulence in humans. And H7N9 is already resistant to amantadine. Moreover, cases of resistance to oseltamivir and zanamivir have been reported.

The potential for mayhem due to H7N9 is such that vaccine development efforts are already underway. Among infectious respiratory disease experts, all eyes are on the coming flu season in Asia and what role H7N9 will play.

"Time will tell whether this will be just another story that comes and goes with influenza, or it becomes a more long-lasting problem," he said.