User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Recent treatment advances brighten prospects for intracerebral hemorrhage patients

LOS ANGELES – Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) appears to be not nearly as uniformly devastating to patients as its reputation suggests. Recent study results documented unexpectedly decent recovery prospects for hemorrhagic stroke patients assessed after 1 year who were earlier considered moderately severe or severely disabled based on their 30-day status. And these data provide further support for the growing impression among clinicians that a way forward for improving outcomes even more is with a “gentle” surgical intervention designed to substantially reduce ICH clot volume.

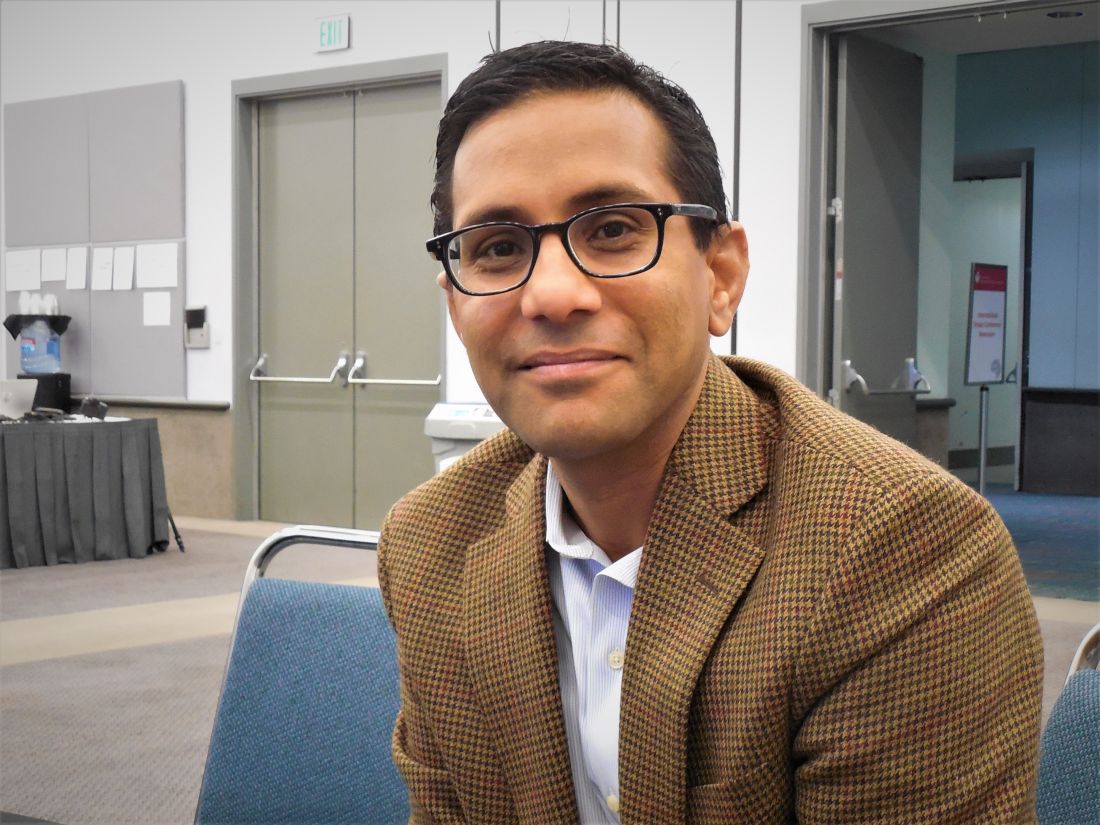

“Historically, there’s been a lot of nihilism around these patients. Intracerebral hemorrhage has always been the deadliest stroke type, but one of the great advances of the past 10-20 years is that ICH survival has improved. Patients do better than we used to think,” said Kevin N. Sheth, MD, professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and chief of neurocritical care and emergency neurology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. “Even though ICH remains a difficult disease, this change has two big implications,” Dr. Sheth said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. First, increased ICH survival offers an opportunity to expand the reach of recent management advances through quality improvement programs that emphasize new strategies that work better and incentivize delivery of these successful strategies to more patients.

The second implication is simply a growing number of ICH survivors, expanding the population of patients who stand to gain from these new management strategies. Dr. Sheth is working with the Get With the Guidelines – Stroke program, a quality-improvement program begun in 2003 and until now aimed at patients with acute ischemic stroke, to develop a 15-site pilot program planned to start in 2020 that will begin implementing and studying a Get With the Guidelines – Stroke quality-improvement program focused on patients with an ICH. The current conception of a quality measurement and improvement program like Get with the Guidelines – Stroke for patients with ICH stems from an important, earlier milestone in the emergence of effective ICH treatments, the 2018 publication of performance measures for ICH care that identified nine key management steps for assessing quality of care and documented the evidence behind them.

“Evidence for optimal treatment of ICH has lagged behind that for ischemic stroke, and consequently, metrics specific to ICH care have not been widely promulgated,” said the authors of the 2018 ICH performance measures, a panel that included Dr. Sheth. “However, numerous more recent studies and clinical trials of various medical and surgical interventions for ICH have been published and form the basis of evidence-based guidelines for the management of ICH,” they explained.

MISTIE III showcases better ICH outcomes

Perhaps the most dramatic recent evidence of brighter prospects for ICH patients came in data collected during the MISTIE III (Minimally Invasive Surgery with Thrombolysis in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation III) trial, which randomized 506 ICH patients with a hematoma of at least 30 mL to standard care or to a “gentle” clot-reduction protocol using a small-bore catheter placed with stereotactic guidance to both evacuate clot and introduce a serial infusion of alteplase into the clot to try to shrink its volume to less than 15 mL. The study’s results showed a neutral effect for the primary outcome, the incidence of recovery to a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-3 at 1 year after entry, which occurred in 45% of the surgically treated patients and 41% of the controls in a modified intention-to-treat analysis that included 499 of the randomized patients, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

However, when the analysis focused on the 146 of 247 patients (59%) randomized to surgical plus lytic intervention who underwent the procedure and actually had their clot volume reduced to 15 mL or less per protocol, the adjusted incidence of the primary endpoint was double that of patients who underwent the procedure but failed to have their residual clot reduced to this size. A similar doubling of good outcomes occurred when MISTIE patients had their residual clot cut to 20 mL or less, compared with those who didn’t reach this, with the differences in both analyses statistically significant. The actual rates showed patients with clot cut to 15 mL or less having a 53% rate of a mRS score of 0-3 after 1 year, compared with 33% of patients who received the intervention but had their residual clot remain above 15 mL.

The MISTIE III investigators looked at their data to try to get better insight into the outcome of all “poor prognosis” patients in the study regardless of their treatment arm assignment, and how patients and their family members made decisions for withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. In MISTIE III, 61 patients had withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WoLST), with more than 40% of the WoLST occurring with patients randomized to the intervention arm including 10 patients treated to a residual clot volume of 15 mL or less. To quantify the disease severity in these 61 patients, the researchers applied a six-item formula at 30 days after the stroke, a metric their 2019 report described in detail. They then used these severity scores to identify 104 matched patients who were alive at 30 days and remained on life-sustaining treatment to see their 1-year outcomes. At 30 days, the 104 matched patients included 82 (79%) with a mRS score of 5 (severe disability) and 22 patients (21%) with a mRS score of 4 (moderately severe disability). Overall, an mRS score of 4 or 5 was quite prevalent 30 days after the stroke, with 87% of the patients treated with the MISTIE intervention and 90% of the control patients having this degree of disability at 30 days.

When the MISTIE III investigators followed these patients for a year, they made an unexpected finding: A substantial incidence of patients whose condition had improved since day 30. One year out, 40 (39%) of these 104 patients had improved to a mRS score of 1-3, including 10 (10%) with a mRS score of 1 or 2. Another indicator of the reasonable outcome many of these patients achieved was that after 1 year 69% were living at home.

“Our data show that many ICH subjects with clinical factors that suggest ‘poor prognosis,’ when given time, can achieve a favorable outcome and return home,” concluded Noeleen Ostapkovich, who presented these results at the Stroke Conference.

She cited these findings as potentially helpful for refining the information given to patients and families on the prognosis for ICH patients at about 30 days after their event, the usual time for assessment. “These patients looked like they weren’t going to do well after 30 days, but by 365 days they had improved physically and in their ability to care for themselves at home,” noted Ms. Ostapkovich, a researcher in the Brain Injury Outcomes Clinical Trial Coordinating Center of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

A message for acute-care clinicians

She and her colleagues highlighted the implications these new findings have for clinical decision making in the first weeks after an ICH.

“Acute-care physicians see these patients at day 30, not at day 365, so it’s important that they have a clear picture of what these patients could look like a year later. It’s an important message,” Ms. Ostapkovich said in an interview.

In fact, a colleague of hers at Johns Hopkins ran an analysis that looked at factors that contributed to families opting for WoLST for 61 of the MISTIE III patients, and found that 38 family groups (62%) cited the anticipated outcome of the patient in a dependent state as their primary reason for opting for WoLST, Lourdes J. Carhuapoma reported in a separate talk at the conference.

“The main message is that many patients with significant ICH did well and recovered despite having very poor prognostic factors at 30 days, but it took more time. A concern is that the [prognostic] information families receive may be wrong. There is a disconnect,” between what families get told to expect and what actually happens, said Ms. Carhuapoma, an acute care nurse practitioner at Johns Hopkins.

“When physicians, nurses, and family members get together” to discuss ICH patients like these after 30 days, “they see the glass as empty. But the real message is that the glass is half full,” summed up Daniel F. Hanley, MD, lead investigator of MISTIE III and professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins. “These data show a large amount of improvement between 30 and 180 days.” The 104 patients with exclusively mRS scores of 4 or 5 at day 30 had a 30% incidence of improvement to an mRS score of 2 or 3 after 180 days, on their way to a 39% rate of mRS scores of 1-3 at 1 year.

An additional analysis that has not yet been presented showed that the “strongest predictor” of whether or not patients who presented with a mRS score of 4 or 5 after 30 days improved their status at 1 year was if their residual hematoma volume shrank to 15 mL or less, Dr. Hanley said in an interview. “It’s not rocket science. If you had to choose between a 45-mL hematoma and less than 15 mL, which would you choose? What’s new here is how this recovery can play out,” taking 180 days or longer in some patients to become apparent.

More evidence needed to prove MISTIE’s hypothesis

According to Dr. Hanley, the MISTIE III findings have begun to influence practice despite its neutral primary finding, with more attention being paid to reducing residual clot volume following an ICH. And evidence continues to mount that more aggressive minimization of hematoma size can have an important effect on outcomes. For example, another study presented at the conference assessed the incremental change in prognostic accuracy when the ICH score, a five-item formula for estimating the prognosis of an ICH patient, substituted a precise quantification of residual hematoma volume rather than the original, dichotomous entry for either a hematoma volume of 30 mL or greater, or less than 30 mL, and when the severity score also quantified intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) volume rather than simply designating IVH as present or absent.

Using data from 933 patients who had been enrolled in either MISTIE III or in another study of hematoma volume reduction, CLEAR III, the analysis showed that including specific quantification of both residual ICH volume as well as residual IVH volume improved the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of the ICH score as a prognostic assessment from 0.70 to 0.75 in the intervention arms of the two trials, and from 0.60 to 0.68 in the two combined control arms, Adam de Havenon, MD, reported in a talk at the conference. “These data show that quantifying ICH and IVH volume improves mortality prognostication,” concluded Dr. de Havenon, a vascular and stroke neurologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Furthermore, it’s “certainly evidence for the importance of volume reduction,” he said during discussion of his talk. “The MISTIE procedure can reset patients” so that their outcomes become more like patients with much smaller clot volumes even if they start with large hematomas. “In our experience, if the volume is reduced to 5 mL, there is real benefit regardless of how big the clot was initially,” Dr. de Havenon said.

But the neutral result for the MISTIE III primary endpoint will, for the time being, hobble application of this concept and keep the MISTIE intervention from rising to a level I recommendation until greater evidence for its efficacy comes out.

“It’s been known for many years that clot size matters when it comes to ICH. The MISTIE team has made a very compelling case that [reducing clot volume] is a very reasonable hypothesis, but we must continue to acquire data that can confirm it,” Dr. Sheth commented.

Dr. Sheth’s institution receives research funding from Novartis and Bard for studies that Dr. Sheth helps run. The MISTIE III study received the alteplase used in the study at no cost from Genentech. Ms. Ostapkovich and Ms. Carhuapoma had no disclosures. Dr. Hanley has received personal fees from BrainScope, Medtronic, Neurotrope, Op2Lysis, and Portola. Dr. de Havenon has received research funding from Regeneron.

LOS ANGELES – Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) appears to be not nearly as uniformly devastating to patients as its reputation suggests. Recent study results documented unexpectedly decent recovery prospects for hemorrhagic stroke patients assessed after 1 year who were earlier considered moderately severe or severely disabled based on their 30-day status. And these data provide further support for the growing impression among clinicians that a way forward for improving outcomes even more is with a “gentle” surgical intervention designed to substantially reduce ICH clot volume.

“Historically, there’s been a lot of nihilism around these patients. Intracerebral hemorrhage has always been the deadliest stroke type, but one of the great advances of the past 10-20 years is that ICH survival has improved. Patients do better than we used to think,” said Kevin N. Sheth, MD, professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and chief of neurocritical care and emergency neurology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. “Even though ICH remains a difficult disease, this change has two big implications,” Dr. Sheth said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. First, increased ICH survival offers an opportunity to expand the reach of recent management advances through quality improvement programs that emphasize new strategies that work better and incentivize delivery of these successful strategies to more patients.

The second implication is simply a growing number of ICH survivors, expanding the population of patients who stand to gain from these new management strategies. Dr. Sheth is working with the Get With the Guidelines – Stroke program, a quality-improvement program begun in 2003 and until now aimed at patients with acute ischemic stroke, to develop a 15-site pilot program planned to start in 2020 that will begin implementing and studying a Get With the Guidelines – Stroke quality-improvement program focused on patients with an ICH. The current conception of a quality measurement and improvement program like Get with the Guidelines – Stroke for patients with ICH stems from an important, earlier milestone in the emergence of effective ICH treatments, the 2018 publication of performance measures for ICH care that identified nine key management steps for assessing quality of care and documented the evidence behind them.

“Evidence for optimal treatment of ICH has lagged behind that for ischemic stroke, and consequently, metrics specific to ICH care have not been widely promulgated,” said the authors of the 2018 ICH performance measures, a panel that included Dr. Sheth. “However, numerous more recent studies and clinical trials of various medical and surgical interventions for ICH have been published and form the basis of evidence-based guidelines for the management of ICH,” they explained.

MISTIE III showcases better ICH outcomes

Perhaps the most dramatic recent evidence of brighter prospects for ICH patients came in data collected during the MISTIE III (Minimally Invasive Surgery with Thrombolysis in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation III) trial, which randomized 506 ICH patients with a hematoma of at least 30 mL to standard care or to a “gentle” clot-reduction protocol using a small-bore catheter placed with stereotactic guidance to both evacuate clot and introduce a serial infusion of alteplase into the clot to try to shrink its volume to less than 15 mL. The study’s results showed a neutral effect for the primary outcome, the incidence of recovery to a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-3 at 1 year after entry, which occurred in 45% of the surgically treated patients and 41% of the controls in a modified intention-to-treat analysis that included 499 of the randomized patients, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

However, when the analysis focused on the 146 of 247 patients (59%) randomized to surgical plus lytic intervention who underwent the procedure and actually had their clot volume reduced to 15 mL or less per protocol, the adjusted incidence of the primary endpoint was double that of patients who underwent the procedure but failed to have their residual clot reduced to this size. A similar doubling of good outcomes occurred when MISTIE patients had their residual clot cut to 20 mL or less, compared with those who didn’t reach this, with the differences in both analyses statistically significant. The actual rates showed patients with clot cut to 15 mL or less having a 53% rate of a mRS score of 0-3 after 1 year, compared with 33% of patients who received the intervention but had their residual clot remain above 15 mL.

The MISTIE III investigators looked at their data to try to get better insight into the outcome of all “poor prognosis” patients in the study regardless of their treatment arm assignment, and how patients and their family members made decisions for withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. In MISTIE III, 61 patients had withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WoLST), with more than 40% of the WoLST occurring with patients randomized to the intervention arm including 10 patients treated to a residual clot volume of 15 mL or less. To quantify the disease severity in these 61 patients, the researchers applied a six-item formula at 30 days after the stroke, a metric their 2019 report described in detail. They then used these severity scores to identify 104 matched patients who were alive at 30 days and remained on life-sustaining treatment to see their 1-year outcomes. At 30 days, the 104 matched patients included 82 (79%) with a mRS score of 5 (severe disability) and 22 patients (21%) with a mRS score of 4 (moderately severe disability). Overall, an mRS score of 4 or 5 was quite prevalent 30 days after the stroke, with 87% of the patients treated with the MISTIE intervention and 90% of the control patients having this degree of disability at 30 days.

When the MISTIE III investigators followed these patients for a year, they made an unexpected finding: A substantial incidence of patients whose condition had improved since day 30. One year out, 40 (39%) of these 104 patients had improved to a mRS score of 1-3, including 10 (10%) with a mRS score of 1 or 2. Another indicator of the reasonable outcome many of these patients achieved was that after 1 year 69% were living at home.

“Our data show that many ICH subjects with clinical factors that suggest ‘poor prognosis,’ when given time, can achieve a favorable outcome and return home,” concluded Noeleen Ostapkovich, who presented these results at the Stroke Conference.

She cited these findings as potentially helpful for refining the information given to patients and families on the prognosis for ICH patients at about 30 days after their event, the usual time for assessment. “These patients looked like they weren’t going to do well after 30 days, but by 365 days they had improved physically and in their ability to care for themselves at home,” noted Ms. Ostapkovich, a researcher in the Brain Injury Outcomes Clinical Trial Coordinating Center of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

A message for acute-care clinicians

She and her colleagues highlighted the implications these new findings have for clinical decision making in the first weeks after an ICH.

“Acute-care physicians see these patients at day 30, not at day 365, so it’s important that they have a clear picture of what these patients could look like a year later. It’s an important message,” Ms. Ostapkovich said in an interview.

In fact, a colleague of hers at Johns Hopkins ran an analysis that looked at factors that contributed to families opting for WoLST for 61 of the MISTIE III patients, and found that 38 family groups (62%) cited the anticipated outcome of the patient in a dependent state as their primary reason for opting for WoLST, Lourdes J. Carhuapoma reported in a separate talk at the conference.

“The main message is that many patients with significant ICH did well and recovered despite having very poor prognostic factors at 30 days, but it took more time. A concern is that the [prognostic] information families receive may be wrong. There is a disconnect,” between what families get told to expect and what actually happens, said Ms. Carhuapoma, an acute care nurse practitioner at Johns Hopkins.

“When physicians, nurses, and family members get together” to discuss ICH patients like these after 30 days, “they see the glass as empty. But the real message is that the glass is half full,” summed up Daniel F. Hanley, MD, lead investigator of MISTIE III and professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins. “These data show a large amount of improvement between 30 and 180 days.” The 104 patients with exclusively mRS scores of 4 or 5 at day 30 had a 30% incidence of improvement to an mRS score of 2 or 3 after 180 days, on their way to a 39% rate of mRS scores of 1-3 at 1 year.

An additional analysis that has not yet been presented showed that the “strongest predictor” of whether or not patients who presented with a mRS score of 4 or 5 after 30 days improved their status at 1 year was if their residual hematoma volume shrank to 15 mL or less, Dr. Hanley said in an interview. “It’s not rocket science. If you had to choose between a 45-mL hematoma and less than 15 mL, which would you choose? What’s new here is how this recovery can play out,” taking 180 days or longer in some patients to become apparent.

More evidence needed to prove MISTIE’s hypothesis

According to Dr. Hanley, the MISTIE III findings have begun to influence practice despite its neutral primary finding, with more attention being paid to reducing residual clot volume following an ICH. And evidence continues to mount that more aggressive minimization of hematoma size can have an important effect on outcomes. For example, another study presented at the conference assessed the incremental change in prognostic accuracy when the ICH score, a five-item formula for estimating the prognosis of an ICH patient, substituted a precise quantification of residual hematoma volume rather than the original, dichotomous entry for either a hematoma volume of 30 mL or greater, or less than 30 mL, and when the severity score also quantified intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) volume rather than simply designating IVH as present or absent.

Using data from 933 patients who had been enrolled in either MISTIE III or in another study of hematoma volume reduction, CLEAR III, the analysis showed that including specific quantification of both residual ICH volume as well as residual IVH volume improved the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of the ICH score as a prognostic assessment from 0.70 to 0.75 in the intervention arms of the two trials, and from 0.60 to 0.68 in the two combined control arms, Adam de Havenon, MD, reported in a talk at the conference. “These data show that quantifying ICH and IVH volume improves mortality prognostication,” concluded Dr. de Havenon, a vascular and stroke neurologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Furthermore, it’s “certainly evidence for the importance of volume reduction,” he said during discussion of his talk. “The MISTIE procedure can reset patients” so that their outcomes become more like patients with much smaller clot volumes even if they start with large hematomas. “In our experience, if the volume is reduced to 5 mL, there is real benefit regardless of how big the clot was initially,” Dr. de Havenon said.

But the neutral result for the MISTIE III primary endpoint will, for the time being, hobble application of this concept and keep the MISTIE intervention from rising to a level I recommendation until greater evidence for its efficacy comes out.

“It’s been known for many years that clot size matters when it comes to ICH. The MISTIE team has made a very compelling case that [reducing clot volume] is a very reasonable hypothesis, but we must continue to acquire data that can confirm it,” Dr. Sheth commented.

Dr. Sheth’s institution receives research funding from Novartis and Bard for studies that Dr. Sheth helps run. The MISTIE III study received the alteplase used in the study at no cost from Genentech. Ms. Ostapkovich and Ms. Carhuapoma had no disclosures. Dr. Hanley has received personal fees from BrainScope, Medtronic, Neurotrope, Op2Lysis, and Portola. Dr. de Havenon has received research funding from Regeneron.

LOS ANGELES – Intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH) appears to be not nearly as uniformly devastating to patients as its reputation suggests. Recent study results documented unexpectedly decent recovery prospects for hemorrhagic stroke patients assessed after 1 year who were earlier considered moderately severe or severely disabled based on their 30-day status. And these data provide further support for the growing impression among clinicians that a way forward for improving outcomes even more is with a “gentle” surgical intervention designed to substantially reduce ICH clot volume.

“Historically, there’s been a lot of nihilism around these patients. Intracerebral hemorrhage has always been the deadliest stroke type, but one of the great advances of the past 10-20 years is that ICH survival has improved. Patients do better than we used to think,” said Kevin N. Sheth, MD, professor of neurology and neurosurgery, and chief of neurocritical care and emergency neurology at Yale University in New Haven, Conn. “Even though ICH remains a difficult disease, this change has two big implications,” Dr. Sheth said in an interview during the International Stroke Conference sponsored by the American Heart Association. First, increased ICH survival offers an opportunity to expand the reach of recent management advances through quality improvement programs that emphasize new strategies that work better and incentivize delivery of these successful strategies to more patients.

The second implication is simply a growing number of ICH survivors, expanding the population of patients who stand to gain from these new management strategies. Dr. Sheth is working with the Get With the Guidelines – Stroke program, a quality-improvement program begun in 2003 and until now aimed at patients with acute ischemic stroke, to develop a 15-site pilot program planned to start in 2020 that will begin implementing and studying a Get With the Guidelines – Stroke quality-improvement program focused on patients with an ICH. The current conception of a quality measurement and improvement program like Get with the Guidelines – Stroke for patients with ICH stems from an important, earlier milestone in the emergence of effective ICH treatments, the 2018 publication of performance measures for ICH care that identified nine key management steps for assessing quality of care and documented the evidence behind them.

“Evidence for optimal treatment of ICH has lagged behind that for ischemic stroke, and consequently, metrics specific to ICH care have not been widely promulgated,” said the authors of the 2018 ICH performance measures, a panel that included Dr. Sheth. “However, numerous more recent studies and clinical trials of various medical and surgical interventions for ICH have been published and form the basis of evidence-based guidelines for the management of ICH,” they explained.

MISTIE III showcases better ICH outcomes

Perhaps the most dramatic recent evidence of brighter prospects for ICH patients came in data collected during the MISTIE III (Minimally Invasive Surgery with Thrombolysis in Intracerebral Hemorrhage Evacuation III) trial, which randomized 506 ICH patients with a hematoma of at least 30 mL to standard care or to a “gentle” clot-reduction protocol using a small-bore catheter placed with stereotactic guidance to both evacuate clot and introduce a serial infusion of alteplase into the clot to try to shrink its volume to less than 15 mL. The study’s results showed a neutral effect for the primary outcome, the incidence of recovery to a modified Rankin Scale (mRS) score of 0-3 at 1 year after entry, which occurred in 45% of the surgically treated patients and 41% of the controls in a modified intention-to-treat analysis that included 499 of the randomized patients, a difference that did not reach statistical significance.

However, when the analysis focused on the 146 of 247 patients (59%) randomized to surgical plus lytic intervention who underwent the procedure and actually had their clot volume reduced to 15 mL or less per protocol, the adjusted incidence of the primary endpoint was double that of patients who underwent the procedure but failed to have their residual clot reduced to this size. A similar doubling of good outcomes occurred when MISTIE patients had their residual clot cut to 20 mL or less, compared with those who didn’t reach this, with the differences in both analyses statistically significant. The actual rates showed patients with clot cut to 15 mL or less having a 53% rate of a mRS score of 0-3 after 1 year, compared with 33% of patients who received the intervention but had their residual clot remain above 15 mL.

The MISTIE III investigators looked at their data to try to get better insight into the outcome of all “poor prognosis” patients in the study regardless of their treatment arm assignment, and how patients and their family members made decisions for withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. In MISTIE III, 61 patients had withdrawal of life-sustaining treatment (WoLST), with more than 40% of the WoLST occurring with patients randomized to the intervention arm including 10 patients treated to a residual clot volume of 15 mL or less. To quantify the disease severity in these 61 patients, the researchers applied a six-item formula at 30 days after the stroke, a metric their 2019 report described in detail. They then used these severity scores to identify 104 matched patients who were alive at 30 days and remained on life-sustaining treatment to see their 1-year outcomes. At 30 days, the 104 matched patients included 82 (79%) with a mRS score of 5 (severe disability) and 22 patients (21%) with a mRS score of 4 (moderately severe disability). Overall, an mRS score of 4 or 5 was quite prevalent 30 days after the stroke, with 87% of the patients treated with the MISTIE intervention and 90% of the control patients having this degree of disability at 30 days.

When the MISTIE III investigators followed these patients for a year, they made an unexpected finding: A substantial incidence of patients whose condition had improved since day 30. One year out, 40 (39%) of these 104 patients had improved to a mRS score of 1-3, including 10 (10%) with a mRS score of 1 or 2. Another indicator of the reasonable outcome many of these patients achieved was that after 1 year 69% were living at home.

“Our data show that many ICH subjects with clinical factors that suggest ‘poor prognosis,’ when given time, can achieve a favorable outcome and return home,” concluded Noeleen Ostapkovich, who presented these results at the Stroke Conference.

She cited these findings as potentially helpful for refining the information given to patients and families on the prognosis for ICH patients at about 30 days after their event, the usual time for assessment. “These patients looked like they weren’t going to do well after 30 days, but by 365 days they had improved physically and in their ability to care for themselves at home,” noted Ms. Ostapkovich, a researcher in the Brain Injury Outcomes Clinical Trial Coordinating Center of Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore.

A message for acute-care clinicians

She and her colleagues highlighted the implications these new findings have for clinical decision making in the first weeks after an ICH.

“Acute-care physicians see these patients at day 30, not at day 365, so it’s important that they have a clear picture of what these patients could look like a year later. It’s an important message,” Ms. Ostapkovich said in an interview.

In fact, a colleague of hers at Johns Hopkins ran an analysis that looked at factors that contributed to families opting for WoLST for 61 of the MISTIE III patients, and found that 38 family groups (62%) cited the anticipated outcome of the patient in a dependent state as their primary reason for opting for WoLST, Lourdes J. Carhuapoma reported in a separate talk at the conference.

“The main message is that many patients with significant ICH did well and recovered despite having very poor prognostic factors at 30 days, but it took more time. A concern is that the [prognostic] information families receive may be wrong. There is a disconnect,” between what families get told to expect and what actually happens, said Ms. Carhuapoma, an acute care nurse practitioner at Johns Hopkins.

“When physicians, nurses, and family members get together” to discuss ICH patients like these after 30 days, “they see the glass as empty. But the real message is that the glass is half full,” summed up Daniel F. Hanley, MD, lead investigator of MISTIE III and professor of neurology at Johns Hopkins. “These data show a large amount of improvement between 30 and 180 days.” The 104 patients with exclusively mRS scores of 4 or 5 at day 30 had a 30% incidence of improvement to an mRS score of 2 or 3 after 180 days, on their way to a 39% rate of mRS scores of 1-3 at 1 year.

An additional analysis that has not yet been presented showed that the “strongest predictor” of whether or not patients who presented with a mRS score of 4 or 5 after 30 days improved their status at 1 year was if their residual hematoma volume shrank to 15 mL or less, Dr. Hanley said in an interview. “It’s not rocket science. If you had to choose between a 45-mL hematoma and less than 15 mL, which would you choose? What’s new here is how this recovery can play out,” taking 180 days or longer in some patients to become apparent.

More evidence needed to prove MISTIE’s hypothesis

According to Dr. Hanley, the MISTIE III findings have begun to influence practice despite its neutral primary finding, with more attention being paid to reducing residual clot volume following an ICH. And evidence continues to mount that more aggressive minimization of hematoma size can have an important effect on outcomes. For example, another study presented at the conference assessed the incremental change in prognostic accuracy when the ICH score, a five-item formula for estimating the prognosis of an ICH patient, substituted a precise quantification of residual hematoma volume rather than the original, dichotomous entry for either a hematoma volume of 30 mL or greater, or less than 30 mL, and when the severity score also quantified intraventricular hemorrhage (IVH) volume rather than simply designating IVH as present or absent.

Using data from 933 patients who had been enrolled in either MISTIE III or in another study of hematoma volume reduction, CLEAR III, the analysis showed that including specific quantification of both residual ICH volume as well as residual IVH volume improved the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve of the ICH score as a prognostic assessment from 0.70 to 0.75 in the intervention arms of the two trials, and from 0.60 to 0.68 in the two combined control arms, Adam de Havenon, MD, reported in a talk at the conference. “These data show that quantifying ICH and IVH volume improves mortality prognostication,” concluded Dr. de Havenon, a vascular and stroke neurologist at the University of Utah in Salt Lake City.

Furthermore, it’s “certainly evidence for the importance of volume reduction,” he said during discussion of his talk. “The MISTIE procedure can reset patients” so that their outcomes become more like patients with much smaller clot volumes even if they start with large hematomas. “In our experience, if the volume is reduced to 5 mL, there is real benefit regardless of how big the clot was initially,” Dr. de Havenon said.

But the neutral result for the MISTIE III primary endpoint will, for the time being, hobble application of this concept and keep the MISTIE intervention from rising to a level I recommendation until greater evidence for its efficacy comes out.

“It’s been known for many years that clot size matters when it comes to ICH. The MISTIE team has made a very compelling case that [reducing clot volume] is a very reasonable hypothesis, but we must continue to acquire data that can confirm it,” Dr. Sheth commented.

Dr. Sheth’s institution receives research funding from Novartis and Bard for studies that Dr. Sheth helps run. The MISTIE III study received the alteplase used in the study at no cost from Genentech. Ms. Ostapkovich and Ms. Carhuapoma had no disclosures. Dr. Hanley has received personal fees from BrainScope, Medtronic, Neurotrope, Op2Lysis, and Portola. Dr. de Havenon has received research funding from Regeneron.

REPORTING FROM ISC 2020

Treating COVID-19 in patients with diabetes

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.

Dr. Gupta and his colleagues noted in their article that there have been reports of the anecdotal use of antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, interferon-beta, the RNA polymerase inhibitor remdesivir, and chloroquine.

However, Dr. Handelsman said that, as far as he knows, none of these drugs has been shown to be beneficial for COVID-19. “Some [providers] have tried Tamiflu, but with no clear outcomes, and for severely sick patients, they tried medications for anti-HIV, hepatitis C, and malaria, but so far, there has been no breakthrough.”

Dr. Cohen, Dr. Handelsman, Dr. Jellinger, Dr. Levy, and Dr. Rettinger are members of the editorial advisory board of Clinical Endocrinology News. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Wu, and their colleagues, reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.

Dr. Gupta and his colleagues noted in their article that there have been reports of the anecdotal use of antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, interferon-beta, the RNA polymerase inhibitor remdesivir, and chloroquine.

However, Dr. Handelsman said that, as far as he knows, none of these drugs has been shown to be beneficial for COVID-19. “Some [providers] have tried Tamiflu, but with no clear outcomes, and for severely sick patients, they tried medications for anti-HIV, hepatitis C, and malaria, but so far, there has been no breakthrough.”

Dr. Cohen, Dr. Handelsman, Dr. Jellinger, Dr. Levy, and Dr. Rettinger are members of the editorial advisory board of Clinical Endocrinology News. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Wu, and their colleagues, reported no conflicts of interest.

Patients with diabetes may be at extra risk for coronavirus disease (COVID-19) mortality, and doctors treating them need to keep up with the latest guidelines and expert advice.

Most health advisories about COVID-19 mention diabetes as one of the high-risk categories for the disease, likely because early data coming out of China, where the disease was first reported, indicated an elevated case-fatality rate for COVID-19 patients who also had diabetes.

In an article published in JAMA, Zunyou Wu, MD, and Jennifer M. McGoogan, PhD, summarized the findings from a February report on 44,672 confirmed cases of the disease from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. The overall case-fatality rate (CFR) at that stage was 2.3% (1,023 deaths of the 44,672 confirmed cases). The data indicated that the CFR was elevated among COVID-19 patients with preexisting comorbid conditions, specifically, cardiovascular disease (CFR, 10.5%), diabetes (7.3%), chronic respiratory disease (6.3%), hypertension (6%), and cancer (5.6%).

The data also showed an aged-related trend in the CFR, with patients aged 80 years or older having a CFR of 14.8% and those aged 70-79 years, a rate of 8.0%, while there were no fatal cases reported in patients aged 9 years or younger (JAMA. 2020 Feb 24. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648).

Those findings have been echoed by the U.S. Centers of Disease Control and Prevention. The American Diabetes Association and the American Association of Clinical Endocrinologists have in turn referenced the CDC in their COVID-19 guidance recommendations for patients with diabetes.

Guidelines were already in place for treatment of infections in patients with diabetes, and

In general, patients with diabetes – especially those whose disease is not controlled, or not well controlled – can be more susceptible to more common infections, such as influenza and pneumonia, possibly because hyperglycemia can subdue immunity by disrupting function of the white blood cells.

Glucose control is key

An important factor in any form of infection control in patients with diabetes seems to be whether or not a patient’s glucose levels are well controlled, according to comments from members of the editorial advisory board for Clinical Endocrinology News. Good glucose control, therefore, could be instrumental in reducing both the risk for and severity of infection.

Paul Jellinger, MD, of the Center for Diabetes & Endocrine Care, Hollywood, Fla., said that, over the years, he had not observed higher infection rates in general in patients with hemoglobin A1c levels below 7, or even higher. However, “a bigger question for me, given the broad category of ‘diabetes’ listed as a risk for serious coronavirus complications by the CDC, has been: Just which individuals with diabetes are really at risk? Are patients with well-controlled diabetes at increased risk as much as those with significant hyperglycemia and uncontrolled diabetes? In my view, not likely.”

Alan Jay Cohen, MD, agreed with Dr. Jellinger. “Many patients have called the office in the last 10 days to ask if there are special precautions they should take because they are reading that they are in the high-risk group because they have diabetes. Many of them are in superb, or at least pretty good, control. I have not seen where they have had a higher incidence of infection than the general population, and I have not seen data with COVID-19 that specifically demonstrates that a person with diabetes in good control has an increased risk,” he said.

“My recommendations to these patients have been the same as those given to the general population,” added Dr. Cohen, medical director at Baptist Medical Group: The Endocrine Clinic, Memphis.

Herbert I. Rettinger, MD, also conceded that poorly controlled blood sugars and confounding illnesses, such as renal and cardiac conditions, are common in patients with long-standing diabetes, but “there is a huge population of patients with type 1 diabetes, and very few seem to be more susceptible to infection. Perhaps I am missing those with poor diet and glucose control.”

Philip Levy, MD, picked up on that latter point, emphasizing that “endocrinologists take care of fewer patients with diabetes than do primary care physicians. Most patients with type 2 diabetes are not seen by us unless the PCP has problems [treating them],” so it could be that PCPs may see a higher number of patients who are at a greater risk for infections.

Ultimately, “good glucose control is very helpful in avoiding infections,” said Dr. Levy, of the Banner University Medical Group Endocrinology & Diabetes, Phoenix.

For sick patients

Guidelines for patients at the Joslin Diabetes Center in Boston advise patients who are feeling sick to continue taking their diabetes medications, unless instructed otherwise by their providers, and to monitor their glucose more frequently because it can spike suddenly.

Patients with type 1 diabetes should check for ketones if their glucose passes 250 mg/dL, according to the guidelines, and patients should remain hydrated at all times and get plenty of rest.

“Sick-day guidelines definitely apply, but patients should be advised to get tested if they have any symptoms they are concerned about,” said Dr. Rettinger, of the Endocrinology Medical Group of Orange County, Orange, Calif.

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, according to Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues (Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020 Mar 10;14[3]:211-2. doi: 10.1016/j.dsx.2020.03.002).

Dr. Rettinger agreed, noting that home management would be feasible as long as “everything is going well, that is, the patient is not experiencing respiratory problems or difficulties in controlling glucose levels. Consider patients with type 1 diabetes who have COVID-19 as you would a nursing home patient – ever vigilant.”

Dr. Gupta and coauthors also recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve. However, the ADA warns in its guidelines that patients should “be aware that some constant glucose monitoring sensors (Dexcom G5, Medtronic Enlite, and Guardian) are impacted by acetaminophen (Tylenol), and that patients should check with finger sticks to ensure accuracy [if they are taking acetaminophen].”

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often, the authors wrote, cautioning that “frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia.” Dr Rettinger emphasized that “hyperglycemia, as always, is best treated with fluids and insulin and frequent checks of sugars to be sure the treatment regimen is successful.”

In regard to diabetic drug regimens, patients with type 1 or 2 disease should continue on their current medications, advised Yehuda Handelsman, MD. “Some, especially those on insulin, may require more of it. And the patient should increase fluid intake to prevent fluid depletion. We do not reduce antihyperglycemic medication to preserve fluids.

“As for hypoglycemia, we always aim for less to no hypoglycemia,” he continued. “Monitoring glucose and appropriate dosage is the way to go. In other words, do not reduce medications in sick patients who typically need more medication.”

Dr. Handelsman, medical director and principal investigator at Metabolic Institute of America, Tarzana, Calif., added that very sick patients who are hospitalized should be managed with insulin and that oral agents – particularly metformin and sodium-glucose transporter 2 inhibitors – should be stopped.

“Once the patient has recovered and stabilized, you can return to the prior regimen, and, even if the patient is still in hospital, noninsulin therapy can be reintroduced,” he said.

“This is standard procedure in very sick patients, especially those in critical care. Metformin may raise lactic acid levels, and the SGLT2 inhibitors cause volume contraction, fat metabolism, and acidosis,” he explained. “We also stop the glucagon-like peptide receptor–1 analogues, which can cause nausea and vomiting, and pioglitazone because it causes fluid overload.

“Only insulin can be used for acutely sick patients – those with sepsis, for example. The same would apply if they have severe breathing disorders, and definitely, if they are on a ventilator. This is also the time we stop aromatase inhibitor orals and we use insulin.”

Preventive measures

In the interest of maintaining good glucose control, patients also should monitor their glucose levels more frequently so that fluctuations can be detected early and quickly addressed with the appropriate medication adjustments, according to guidelines from the ADA and AACE. They should continue to follow a healthy diet that includes adequate protein and they should exercise regularly.

Patients should ensure that they have enough medication and testing supplies – for at least 14 days, and longer, if costs permit – in case they have to go into quarantine.

General preventive measures, such as frequent hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing or coughing into a facial tissue or bent elbow, also apply for reducing the risk of infection. Touching of the face should be avoided, as should nonessential travel and contact with infected individuals.

Patients with diabetes should always be current with their influenza and pneumonia shots.

Dr. Rettinger said that he always recommends the following preventative measures to his patients and he is using the current health crisis to reinforce them:

- Eat lots of multicolored fruits and vegetables.

- Eat yogurt and take probiotics to keep the intestinal biome strong and functional.

- Be extra vigilant regarding sugars and sugar control to avoid peaks and valleys wherever possible.

- Keep the immune system strong with at least 7-8 hours sleep and reduce stress levels whenever possible.

- Avoid crowds and handshaking.

- Wash hands regularly.

Possible therapies

There are currently no drugs that have been approved specifically for the treatment of COVID-19, although a vaccine against the disease is currently under development.

Dr. Gupta and his colleagues noted in their article that there have been reports of the anecdotal use of antiviral drugs such as lopinavir, ritonavir, interferon-beta, the RNA polymerase inhibitor remdesivir, and chloroquine.

However, Dr. Handelsman said that, as far as he knows, none of these drugs has been shown to be beneficial for COVID-19. “Some [providers] have tried Tamiflu, but with no clear outcomes, and for severely sick patients, they tried medications for anti-HIV, hepatitis C, and malaria, but so far, there has been no breakthrough.”

Dr. Cohen, Dr. Handelsman, Dr. Jellinger, Dr. Levy, and Dr. Rettinger are members of the editorial advisory board of Clinical Endocrinology News. Dr. Gupta and Dr. Wu, and their colleagues, reported no conflicts of interest.

COVID-19: Extra caution needed for patients with diabetes

Patients with diabetes may have an increased risk of developing coronavirus infection (COVID-19), along with increased risks of morbidity and mortality, according to researchers writing in Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome.

Although relevant clinical data remain scarce, patients with diabetes should take extra precautions to avoid infection and, if infected, may require special care, reported Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues.

“The disease severity [with COVID-19] has varied from mild, self-limiting, flu-like illness to fulminant pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death,” the authors wrote.

As of March 16, 2020, the World Health Organization reported 167,515 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 6,606 deaths from around the world, with a mortality rate of 3.9%. But the actual mortality rate may be lower, the authors suggested, because a study involving more than 1,000 confirmed cases reported a mortality rate of 1.4%.

“Considering that the number of unreported and unconfirmed cases is likely to be much higher than the reported cases, the actual mortality may be less than 1%, which is similar to that of severe seasonal influenza,” the authors said, in reference to an editorial by Anthony S. Fauci, MD, and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine. In addition, they noted, mortality rates may vary by region.

The largest study relevant to patients with diabetes, which involved 72,314 cases of COVID-19, showed that patients with diabetes had a threefold higher mortality rate than did those without diabetes (7.3% vs. 2.3%, respectively). These figures were reported by the Chinese Centre for Disease Control and Prevention.

However, data from smaller cohorts with diabetes and COVID-19 have yielded mixed results. For instance, one study, involving 140 patients from Wuhan, suggested that diabetes was not a risk factor for severe disease, and in an analysis of 11 studies reporting on laboratory abnormalities in patients with a diagnosis of COVID-19, raised blood sugar levels or diabetes were not mentioned among the predictors of severe disease.

“Our knowledge about the prevalence of COVID-19 and disease course in people with diabetes will evolve as more detailed analyses are carried out,” the authors wrote. “For now, it is reasonable to assume that people with diabetes are at increased risk of developing infection. Coexisting heart disease, kidney disease, advanced age, and frailty are likely to further increase the severity of disease.”

Prevention first

“It is important that people with diabetes maintain good glycemic control, because it might help in reducing the risk of infection and the severity,” the authors wrote.

In addition to more frequent monitoring of blood glucose levels, they recommended other preventive measures, such as getting adequate nutrition, exercising, and being current with vaccinations for influenza and pneumonia. The latter, they said, may also reduce the risk of secondary bacterial pneumonia after a respiratory viral infection.

In regard to nutrition, adequate protein intake is important and “any deficiencies of minerals and vitamins need to be taken care of,” they advised. Likewise, exercise is known to improve immunity and should continue, but they suggest avoiding gyms and swimming pools.

For patients with coexisting heart and/or kidney disease, they also recommended efforts to stabilize cardiac/renal status.

In addition, the general preventive measures, such as regular and thorough hand washing with soap and water, practicing good respiratory hygiene by sneezing and coughing into a bent elbow or a facial tissue, and avoiding contact with anyone who is infected, should be observed.

As with other patients with chronic diseases that are managed long-term medications, patients with diabetes should always ensure that they have a sufficient supply of their medications and refills, if possible.

After a diagnosis

If patients with diabetes develop COVID-19, then home management may still be possible, wrote the authors, who recommended basic treatment measures such as maintaining hydration and managing symptoms with acetaminophen and steam inhalation, and home isolation for 14 days or until the symptoms resolve.

In the event of hyperglycemia with fever in patients with type 1 diabetes, blood glucose and urinary ketones should be monitored often. “Frequent changes in dosage and correctional bolus may be required to maintain normoglycemia,” they cautioned.

Concerning diabetic drug regimens, they suggest patients avoid antihyperglycemic agents that can cause volume depletion or hypoglycemia and, if necessary, that they reduce oral antidiabetic drugs and follow sick-day guidelines.

For hospitalized patients, the investigators strengthened that statement, advising that oral agents need to be stopped, particularly sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors and metformin. “Insulin is the preferred agent for control of hyperglycemia in hospitalized sick patients,” they wrote.

Untested therapies

The authors also discussed a range of untested therapies that may help fight COVID-19, such as antiviral drugs (such as lopinavir and ritonavir), zinc nanoparticles, and vitamin C. Supplementing those recommendations, Dr. Gupta and colleagues provided a concise review of COVID-19 epidemiology and extant data relevant to patients with diabetes.

The investigators reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Gupta et al. Diabetes Metab Syndr. 2020;14(3):211-12.

Patients with diabetes may have an increased risk of developing coronavirus infection (COVID-19), along with increased risks of morbidity and mortality, according to researchers writing in Diabetes & Metabolic Syndrome.

Although relevant clinical data remain scarce, patients with diabetes should take extra precautions to avoid infection and, if infected, may require special care, reported Ritesh Gupta, MD, of Fortis C-DOC Hospital, New Delhi, and colleagues.

“The disease severity [with COVID-19] has varied from mild, self-limiting, flu-like illness to fulminant pneumonia, respiratory failure, and death,” the authors wrote.

As of March 16, 2020, the World Health Organization reported 167,515 confirmed cases of COVID-19 and 6,606 deaths from around the world, with a mortality rate of 3.9%. But the actual mortality rate may be lower, the authors suggested, because a study involving more than 1,000 confirmed cases reported a mortality rate of 1.4%.

“Considering that the number of unreported and unconfirmed cases is likely to be much higher than the reported cases, the actual mortality may be less than 1%, which is similar to that of severe seasonal influenza,” the authors said, in reference to an editorial by Anthony S. Fauci, MD, and colleagues in the New England Journal of Medicine. In addition, they noted, mortality rates may vary by region.