User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

New guidance on management of acute CVD during COVID-19

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

The Chinese Society of Cardiology (CSC) has issued a consensus statement on the management of cardiac emergencies during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The document first appeared in the Chinese Journal of Cardiology, and a translated version was published in Circulation. The consensus statement was developed by 125 medical experts in the fields of cardiovascular disease and infectious disease. This included 23 experts currently working in Wuhan, China.

Three overarching principles guided their recommendations.

- The highest priority is prevention and control of transmission (including protecting staff).

- Patients should be assessed both for COVID-19 and for cardiovascular issues.

- At all times, all interventions and therapies provided should be in concordance with directives of infection control authorities.

“Considering that some asymptomatic patients may be a source of infection and transmission, all patients with severe emergent cardiovascular diseases should be managed as suspected cases of COVID-19 in Hubei Province,” noted writing chair and cardiologist Yaling Han, MD, of the General Hospital of Northern Theater Command in Shenyang, China.

In areas outside Hubei Province, where COVID-19 was less prevalent, this “infected until proven otherwise” approach was also recommended, although not as strictly.

Diagnosing CVD and COVID-19 simultaneously

In patients with emergent cardiovascular needs in whom COVID-19 has not been ruled out, quarantine in a single-bed room is needed, they wrote. The patient should be monitored for clinical manifestations of the disease, and undergo COVID-19 nucleic acid testing as soon as possible.

After infection control is considered, including limiting risk for infection to health care workers, risk assessment that weighs the relative advantages and disadvantages of treating the cardiovascular disease while preventing transmission can be considered, the investigators wrote.

At all times, transfers to different areas of the hospital and between hospitals should be minimized to reduce the risk for infection transmission.

The authors also recommended the use of “select laboratory tests with definitive sensitivity and specificity for disease diagnosis or assessment.”

For patients with acute aortic syndrome or acute pulmonary embolism, this means CT angiography. When acute pulmonary embolism is suspected, D-dimer testing and deep vein ultrasound can be employed, and for patients with acute coronary syndrome, ordinary electrocardiography and standard biomarkers for cardiac injury are preferred.

In addition, “all patients should undergo lung CT examination to evaluate for imaging features typical of COVID-19. ... Chest x-ray is not recommended because of a high rate of false negative diagnosis,” the authors wrote.

Intervene with caution

Medical therapy should be optimized in patients with emergent cardiovascular issues, with invasive strategies for diagnosis and therapy used “with caution,” according to the Chinese experts.

Conditions for which conservative medical treatment is recommended during COVID-19 pandemic include ST-segment elevation MI (STEMI) where thrombolytic therapy is indicated, STEMI when the optimal window for revascularization has passed, high-risk non-STEMI (NSTEMI), patients with uncomplicated Stanford type B aortic dissection, acute pulmonary embolism, acute exacerbation of heart failure, and hypertensive emergency.

“Vigilance should be paid to avoid misdiagnosing patients with pulmonary infarction as COVID-19 pneumonia,” they noted.

Diagnoses warranting invasive intervention are limited to STEMI with hemodynamic instability, life-threatening NSTEMI, Stanford type A or complex type B acute aortic dissection, bradyarrhythmia complicated by syncope or unstable hemodynamics mandating implantation of a device, and pulmonary embolism with hemodynamic instability for whom intravenous thrombolytics are too risky.

Interventions should be done in a cath lab or operating room with negative-pressure ventilation, with strict periprocedural disinfection. Personal protective equipment should also be of the strictest level.

In patients for whom COVID-19 cannot be ruled out presenting in a region with low incidence of COVID-19, interventions should only be considered for more severe cases and undertaken in a cath lab, electrophysiology lab, or operating room “with more than standard disinfection procedures that fulfill regulatory mandates for infection control.”

If negative-pressure ventilation is not available, air conditioning (for example, laminar flow and ventilation) should be stopped.

Establish plans now

“We operationalized all of these strategies at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center several weeks ago, since Boston had that early outbreak with the Biogen conference, but I suspect many institutions nationally are still formulating plans,” said Dhruv Kazi, MD, MSc, in an interview.

Although COVID-19 is “primarily a single-organ disease – it destroys the lungs” – transmission of infection to cardiology providers was an early problem that needed to be addressed, said Dr. Kazi. “We now know that a cardiologist seeing a patient who reports shortness of breath and then leans in to carefully auscultate the lungs and heart can get exposed if not provided adequate personal protective equipment; hence the cancellation of elective procedures, conversion of most elective visits to telemedicine, if possible, and the use of surgical/N95 masks in clinic and on rounds.”

Regarding the CSC recommendation to consider medical over invasive management, Dr. Kazi noteed that this works better in a setting where rapid testing is available. “Where that is not the case – as in the U.S. – resorting to conservative therapy for all COVID suspect cases will result in suboptimal care, particularly when nine out of every 10 COVID suspects will eventually rule out.”

One of his biggest worries now is that patients simply won’t come. Afraid of being exposed to COVID-19, patients with MIs and strokes may avoid or delay coming to the hospital.

“There is some evidence that this occurred in Wuhan, and I’m starting to see anecdotal evidence of this in Boston,” said Dr. Kazi. “We need to remind our patients that, if they experience symptoms of a heart attack or stroke, they deserve the same lifesaving treatment we offered before this pandemic set in. They should not try and sit it out.”

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

FDA issues EUA allowing hydroxychloroquine sulfate, chloroquine phosphate treatment in COVID-19

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

The Food and Drug Administration issued an Emergency Use Authorization on March 28, 2020, allowing for the usage of hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate products in certain hospitalized patients with COVID-19.

The products, currently stored by the Strategic National Stockpile, will be distributed by the SNS to states so that doctors may prescribe the drugs to adolescent and adult patients hospitalized with COVID-19 in the absence of appropriate or feasible clinical trials. The SNS will work with the Federal Emergency Management Agency to ship the products to states.

According to the Emergency Use Authorization, fact sheets will be provided to health care providers and patients with important information about hydroxychloroquine sulfate and chloroquine phosphate, including the risks of using them to treat COVID-19.

Strategies for treating patients with health anxiety

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

Up to 20% of patients in medical settings experience health anxiety.1,2 In DSM-IV-TR, this condition was called hypochondriasis, and its core feature was having a preoccupation with fears or the idea that one has a serious disease based on a misinterpretation of ≥1 bodily signs or symptoms despite undergoing appropriate medical evaluation.3 In DSM-5, hypochondriasis was removed, and somatic symptom disorder and illness anxiety disorder were introduced.1 Approximately 75% of patients with a previous diagnosis of hypochondriasis meet the diagnostic criteria for somatic symptom disorder, and approximately 25% meet the criteria for illness anxiety disorder.1 In clinical practice, the less pejorative and more commonly used term for these conditions is “health anxiety.”

Patients with health anxiety can be challenging to treat because they persist in believing they have an illness despite appropriate medical evaluation. Clinicians’ responses to such patients can range from feeling the need to do more to alleviate their suffering to strongly disliking them. Although these patients can elicit negative countertransference, we should remember that their lives are being adversely affected due to the substantial functional impairment they experience from their health worries. As psychiatrists, we can help our patients with health anxiety by employing the following strategies.

Maintain constant communication with other clinicians who manage the patient’s medical complaints. A clear line of communication with other clinicians can help minimize inconsistent or conflicting messages and potentially reduce splitting. This also can allow other clinicians to air their concerns, and for you to emphasize to them that patients with health anxiety can have an actual medical disease.

Allow patients to discuss their symptoms without interrupting them. This will help them understand that you are listening to them and taking their worries seriously.2 Elicit further discussion by asking them about2:

- their perception of their health

- how frequently they worry about their health

- fears about what could happen

- triggers for their worries

- how seriously they feel other clinicians regard their concerns

- behaviors they use to subdue their worries

- avoidance behaviors

- the impact their worries have on their lives.

Assess patients for the presence of comorbid mental health conditions such as anxiety disorders, mood disorders, psychotic disorders, personality disorders, and substance use disorders. Treating these conditions can help reduce your patients’ health anxiety–related distress and impairment.

Acknowledge that your patients’ symptoms are real to them and genuinely experienced.2 By focusing on worry as the most important symptom and recognizing how discomforting and serious that worry can be, you can validate your patients’ feelings and increase their motivation for continuing treatment.2

Avoid reassuring patients that they are medically healthy, because any relief your patients gain from this can quickly fade, and their anxiety may worsen.2 Instead, acknowledge their concerns by saying, “It’s clear that you are worried about your health. We have ways of helping this, and this will not affect any other treatment you are receiving.”2 This could allow your patients to recognize that they have health anxiety without believing that their medical problems will be disregarded or dismissed.2

Explain to patients that their perceptions could be symptoms of anxiety instead of an actual medical illness, equating health anxiety to a false alarm.2 Ask patients to summarize any information you present to them, because misinterpreting health information is a core feature of health anxiety.2

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

1. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 5th ed. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2013.

2. Hedman-Lagerlöf E, Tyrer P, Hague J, et al. Health anxiety. BMJ. 2019;364:I774. doi: 10.1136/bmj.I774.

3. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders. 4th ed, text rev. Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association; 2000.

FDA OKs durvalumab combo for extensive-stage SCLC

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved the immunotherapy durvalumab (Imfinzi, AstraZeneca) in combination with etoposide and either carboplatin or cisplatin as first-line treatment of patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC).

Durvalumab plus chemotherapy “can be considered a new standard in ES-SCLC,” said Myung-Ju Ahn, MD, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, South Korea, last year at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting, where he discussed results from the phase 3 trial known as CASPIAN.

The new approval is based on efficacy and safety data from that trial, conducted in patients with previously untreated ES-SCLC. In the experimental group (n = 268), durvalumab plus etoposide and a platinum agent (EP) was followed by maintenance durvalumab, and in the control group (n = 269) patients received the EP regimen alone.

Median overall survival (OS) was 13 months in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group compared with 10.3 months in the chemotherapy alone group (hazard ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91; P = .0047).

Reporting these results, trial investigator Luis Paz-Ares, MD, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, put the new survival benefit in the context of standard treatments at the ESMO meeting last year.

“Initial response rates to etoposide plus a platinum are high, but responses are not durable and patients treated with EP typically relapse within 6 months of starting treatment with a median OS of approximately 10 months,” he said.

In addition to the primary endpoint of OS, additional efficacy outcome measures were investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR).

Median PFS was not statistically significant with immunotherapy; it was 5.1 months (95% CI, 4.7-6.2) in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.2) in the chemotherapy alone group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.94).

The investigator-assessed ORR was 68% in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 58% in the chemotherapy alone group.

The most common adverse reactions (≥ 20%) in patients with ES-SCLC were nausea, fatigue/asthenia, and alopecia, according to the FDA.

At ESMO, Paz-Ares reported that rates of serious adverse events (AEs) were comparable at 30.9% and 36.1% for the durvalumab plus EP group vs. EP alone, respectively; rates of AEs leading to discontinuation were identical in both groups at 9.4%. Unsurprisingly, immune-mediated AEs were higher at 19.6% in the durvalumab combination group vs. 2.6% in the EP alone group.

In this setting, durvalumab is administered prior to chemotherapy on the same day. The recommended durvalumab dose (when administered with etoposide and carboplatin or cisplatin) is 1,500 mg every 3 weeks prior to chemotherapy and then every 4 weeks as a single-agent maintenance therapy.

Durvalumab is already approved for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer in patients whose tumors have only spread in the chest, and is also approved for use in urothelial cancer.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved the immunotherapy durvalumab (Imfinzi, AstraZeneca) in combination with etoposide and either carboplatin or cisplatin as first-line treatment of patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC).

Durvalumab plus chemotherapy “can be considered a new standard in ES-SCLC,” said Myung-Ju Ahn, MD, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, South Korea, last year at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting, where he discussed results from the phase 3 trial known as CASPIAN.

The new approval is based on efficacy and safety data from that trial, conducted in patients with previously untreated ES-SCLC. In the experimental group (n = 268), durvalumab plus etoposide and a platinum agent (EP) was followed by maintenance durvalumab, and in the control group (n = 269) patients received the EP regimen alone.

Median overall survival (OS) was 13 months in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group compared with 10.3 months in the chemotherapy alone group (hazard ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91; P = .0047).

Reporting these results, trial investigator Luis Paz-Ares, MD, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, put the new survival benefit in the context of standard treatments at the ESMO meeting last year.

“Initial response rates to etoposide plus a platinum are high, but responses are not durable and patients treated with EP typically relapse within 6 months of starting treatment with a median OS of approximately 10 months,” he said.

In addition to the primary endpoint of OS, additional efficacy outcome measures were investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR).

Median PFS was not statistically significant with immunotherapy; it was 5.1 months (95% CI, 4.7-6.2) in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.2) in the chemotherapy alone group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.94).

The investigator-assessed ORR was 68% in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 58% in the chemotherapy alone group.

The most common adverse reactions (≥ 20%) in patients with ES-SCLC were nausea, fatigue/asthenia, and alopecia, according to the FDA.

At ESMO, Paz-Ares reported that rates of serious adverse events (AEs) were comparable at 30.9% and 36.1% for the durvalumab plus EP group vs. EP alone, respectively; rates of AEs leading to discontinuation were identical in both groups at 9.4%. Unsurprisingly, immune-mediated AEs were higher at 19.6% in the durvalumab combination group vs. 2.6% in the EP alone group.

In this setting, durvalumab is administered prior to chemotherapy on the same day. The recommended durvalumab dose (when administered with etoposide and carboplatin or cisplatin) is 1,500 mg every 3 weeks prior to chemotherapy and then every 4 weeks as a single-agent maintenance therapy.

Durvalumab is already approved for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer in patients whose tumors have only spread in the chest, and is also approved for use in urothelial cancer.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration has approved the immunotherapy durvalumab (Imfinzi, AstraZeneca) in combination with etoposide and either carboplatin or cisplatin as first-line treatment of patients with extensive-stage small cell lung cancer (ES-SCLC).

Durvalumab plus chemotherapy “can be considered a new standard in ES-SCLC,” said Myung-Ju Ahn, MD, Sungkyunkwan University, Seoul, South Korea, last year at the European Society of Medical Oncology (ESMO) annual meeting, where he discussed results from the phase 3 trial known as CASPIAN.

The new approval is based on efficacy and safety data from that trial, conducted in patients with previously untreated ES-SCLC. In the experimental group (n = 268), durvalumab plus etoposide and a platinum agent (EP) was followed by maintenance durvalumab, and in the control group (n = 269) patients received the EP regimen alone.

Median overall survival (OS) was 13 months in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group compared with 10.3 months in the chemotherapy alone group (hazard ratio 0.73; 95% confidence interval, 0.59-0.91; P = .0047).

Reporting these results, trial investigator Luis Paz-Ares, MD, Hospital Universitario 12 de Octubre, Madrid, put the new survival benefit in the context of standard treatments at the ESMO meeting last year.

“Initial response rates to etoposide plus a platinum are high, but responses are not durable and patients treated with EP typically relapse within 6 months of starting treatment with a median OS of approximately 10 months,” he said.

In addition to the primary endpoint of OS, additional efficacy outcome measures were investigator-assessed progression-free survival (PFS) and objective response rate (ORR).

Median PFS was not statistically significant with immunotherapy; it was 5.1 months (95% CI, 4.7-6.2) in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 5.4 months (95% CI, 4.8-6.2) in the chemotherapy alone group (HR, 0.78; 95% CI, 0.65-0.94).

The investigator-assessed ORR was 68% in the durvalumab plus chemotherapy group and 58% in the chemotherapy alone group.

The most common adverse reactions (≥ 20%) in patients with ES-SCLC were nausea, fatigue/asthenia, and alopecia, according to the FDA.

At ESMO, Paz-Ares reported that rates of serious adverse events (AEs) were comparable at 30.9% and 36.1% for the durvalumab plus EP group vs. EP alone, respectively; rates of AEs leading to discontinuation were identical in both groups at 9.4%. Unsurprisingly, immune-mediated AEs were higher at 19.6% in the durvalumab combination group vs. 2.6% in the EP alone group.

In this setting, durvalumab is administered prior to chemotherapy on the same day. The recommended durvalumab dose (when administered with etoposide and carboplatin or cisplatin) is 1,500 mg every 3 weeks prior to chemotherapy and then every 4 weeks as a single-agent maintenance therapy.

Durvalumab is already approved for metastatic non–small cell lung cancer in patients whose tumors have only spread in the chest, and is also approved for use in urothelial cancer.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the Phoenix area, we are in a lull before the coronavirus storm

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

“There is no sound save the throb of the blowers and the vibration of the hard-driven engines. There is little motion as the gun crews man their guns and the fire-control details stand with heads bent and their hands clapped over their headphones. Somewhere out there are the enemy planes.”

That’s from one of my favorite WW2 histories, “Torpedo Junction,” by Robert J. Casey. He was a reporter stationed on board the cruiser USS Salt Lake City. The entry is from a day in February 1942 when the ship was part of a force that bombarded the Japanese encampment on Wake Island. The excerpt describes the scene later that afternoon, as they awaited a counterattack from Japanese planes.

For some reason that paragraph kept going through my mind this past Sunday afternoon, in the comparatively mundane situation of sitting in the hospital library signing off on my dictations and reviewing test results. I certainly was in no danger of being bombed or strafed, yet ...

Around me, the hospital was preparing for battle. As I rounded, most of the beds were empty and many of the floors above me were shut down and darkened. Waiting rooms were empty. If you hadn’t read the news you’d think there was a sudden lull in the health care world.

But the real truth is that it’s the calm before an anticipated storm. The elective procedures have all been canceled. Nonurgent outpatient tests are on hold. Only the sickest are being admitted, and they’re being sent out as soon as possible. Every bed possible is being kept open for the feared onslaught of coronavirus patients in the coming weeks. Protective equipment, already in short supply, is being stockpiled as it becomes available. Plans have been made to erect triage tents in the parking lots.

I sit in the library and think of this. It’s quiet except for the soft hum of the air conditioning blowers as Phoenix starts to warm up for another summer. The muted purr of the computer’s hard drive as I click away on the keys. On the floors above me the nurses and respiratory techs and doctors go about their daily business of patient care, wondering when the real battle will begin (probably 2-3 weeks from the time of this writing, if not sooner).

These are scary times. I’d be lying if I said I wasn’t frightened about what might happen to me, my family, my friends, my coworkers, my patients.

The people working in the hospital above me are in the same boat, all nervous about what’s going to happen. None of them is any more immune to coronavirus than the people they’ll be treating.

But, like the crew of the USS Salt Lake City, they’re ready to do their jobs. Because it’s part of what drove each of us into our own part of this field. Because we care and want to help. And health care doesn’t work unless the whole team does.

I respect them all for it. I always have and always will, and now more than ever.

Good luck.

Dr. Block has a solo neurology practice in Scottsdale, Ariz. He has no relevant disclosures.

FDA approves ixekizumab for pediatric plaque psoriasis

The according to an announcement from Lilly.

Patients need to be candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have no known hypersensitivity to the biologic.

The safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the interleukin-17a antagonist were demonstrated in a phase 3 study that included 171 patients aged 6-17 years with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. At 12 weeks, 89% those on ixekizumab achieved a 75% improvement on Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, compared with 25% of those on placebo, and 81% achieved a static Physician’s Global Assessment of clear or almost clear, compared with 11% of those on placebo, according to the Lilly statement.

The safety profile seen with ixekizumab (Taltz) among the pediatric patients with plaque psoriasis is consistent with what has been observed among adult patients, although there were higher rates of conjunctivitis, influenza, and urticaria among the pediatric patients, the statement noted. The biologic may increase the risk of infection, and patients should be evaluated for tuberculosis, hypersensitivity, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is also recommended that routine immunizations be completed before initiating treatment.

Ixekizumab was initially approved for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2016, followed by approvals for treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis in 2017, and for adults with ankylosing spondylitis in August 2019.

The biologic therapies – etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor blocker, and ustekinumab (Stelara), an IL-12/23 antagonist – were previously approved by the FDA for pediatric psoriasis, in children ages 4 years and older and 12 years and older, respectively.

Updated prescribing information for ixekizumab can be found on the Lilly website.

[email protected]

The according to an announcement from Lilly.

Patients need to be candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have no known hypersensitivity to the biologic.

The safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the interleukin-17a antagonist were demonstrated in a phase 3 study that included 171 patients aged 6-17 years with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. At 12 weeks, 89% those on ixekizumab achieved a 75% improvement on Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, compared with 25% of those on placebo, and 81% achieved a static Physician’s Global Assessment of clear or almost clear, compared with 11% of those on placebo, according to the Lilly statement.

The safety profile seen with ixekizumab (Taltz) among the pediatric patients with plaque psoriasis is consistent with what has been observed among adult patients, although there were higher rates of conjunctivitis, influenza, and urticaria among the pediatric patients, the statement noted. The biologic may increase the risk of infection, and patients should be evaluated for tuberculosis, hypersensitivity, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is also recommended that routine immunizations be completed before initiating treatment.

Ixekizumab was initially approved for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2016, followed by approvals for treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis in 2017, and for adults with ankylosing spondylitis in August 2019.

The biologic therapies – etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor blocker, and ustekinumab (Stelara), an IL-12/23 antagonist – were previously approved by the FDA for pediatric psoriasis, in children ages 4 years and older and 12 years and older, respectively.

Updated prescribing information for ixekizumab can be found on the Lilly website.

[email protected]

The according to an announcement from Lilly.

Patients need to be candidates for systemic therapy or phototherapy and have no known hypersensitivity to the biologic.

The safety, tolerability, and efficacy of the interleukin-17a antagonist were demonstrated in a phase 3 study that included 171 patients aged 6-17 years with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis. At 12 weeks, 89% those on ixekizumab achieved a 75% improvement on Psoriasis Area and Severity Index score, compared with 25% of those on placebo, and 81% achieved a static Physician’s Global Assessment of clear or almost clear, compared with 11% of those on placebo, according to the Lilly statement.

The safety profile seen with ixekizumab (Taltz) among the pediatric patients with plaque psoriasis is consistent with what has been observed among adult patients, although there were higher rates of conjunctivitis, influenza, and urticaria among the pediatric patients, the statement noted. The biologic may increase the risk of infection, and patients should be evaluated for tuberculosis, hypersensitivity, and inflammatory bowel disease. It is also recommended that routine immunizations be completed before initiating treatment.

Ixekizumab was initially approved for treating adults with moderate to severe plaque psoriasis in 2016, followed by approvals for treatment of adults with active psoriatic arthritis in 2017, and for adults with ankylosing spondylitis in August 2019.

The biologic therapies – etanercept, a tumor necrosis factor blocker, and ustekinumab (Stelara), an IL-12/23 antagonist – were previously approved by the FDA for pediatric psoriasis, in children ages 4 years and older and 12 years and older, respectively.

Updated prescribing information for ixekizumab can be found on the Lilly website.

[email protected]

Physician couples draft wills, face tough questions amid COVID-19

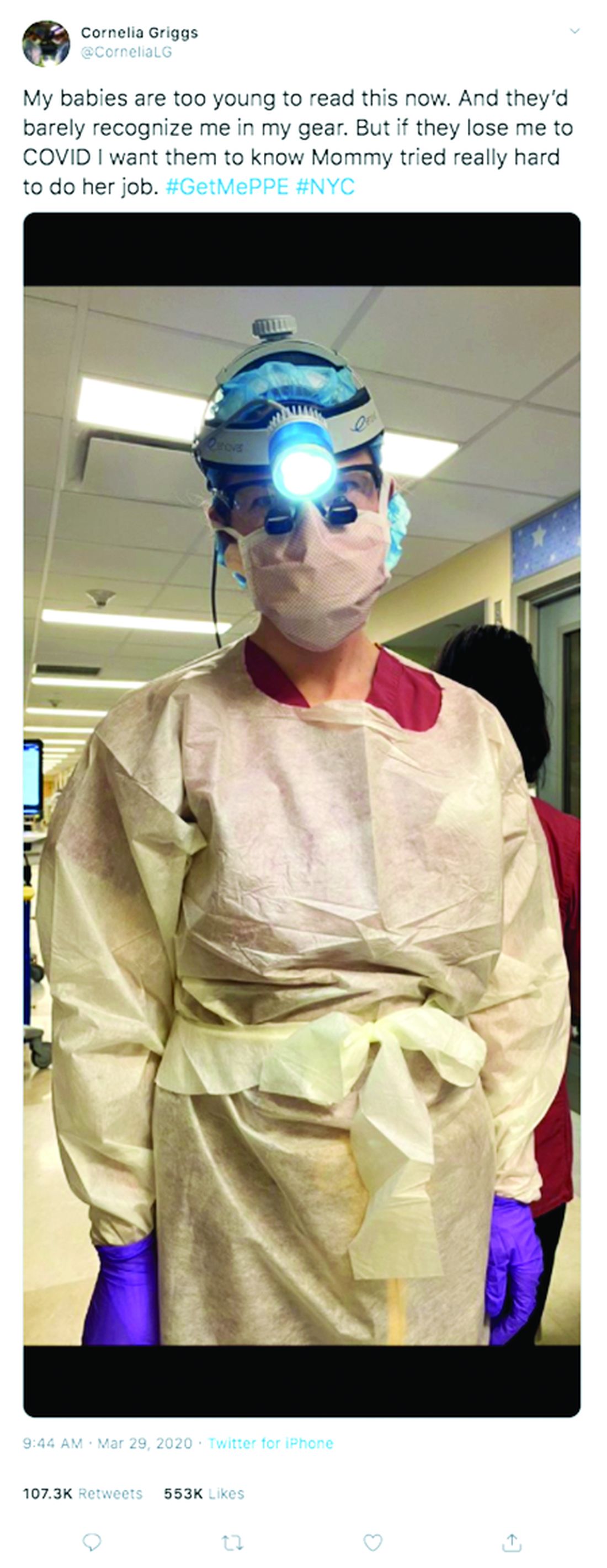

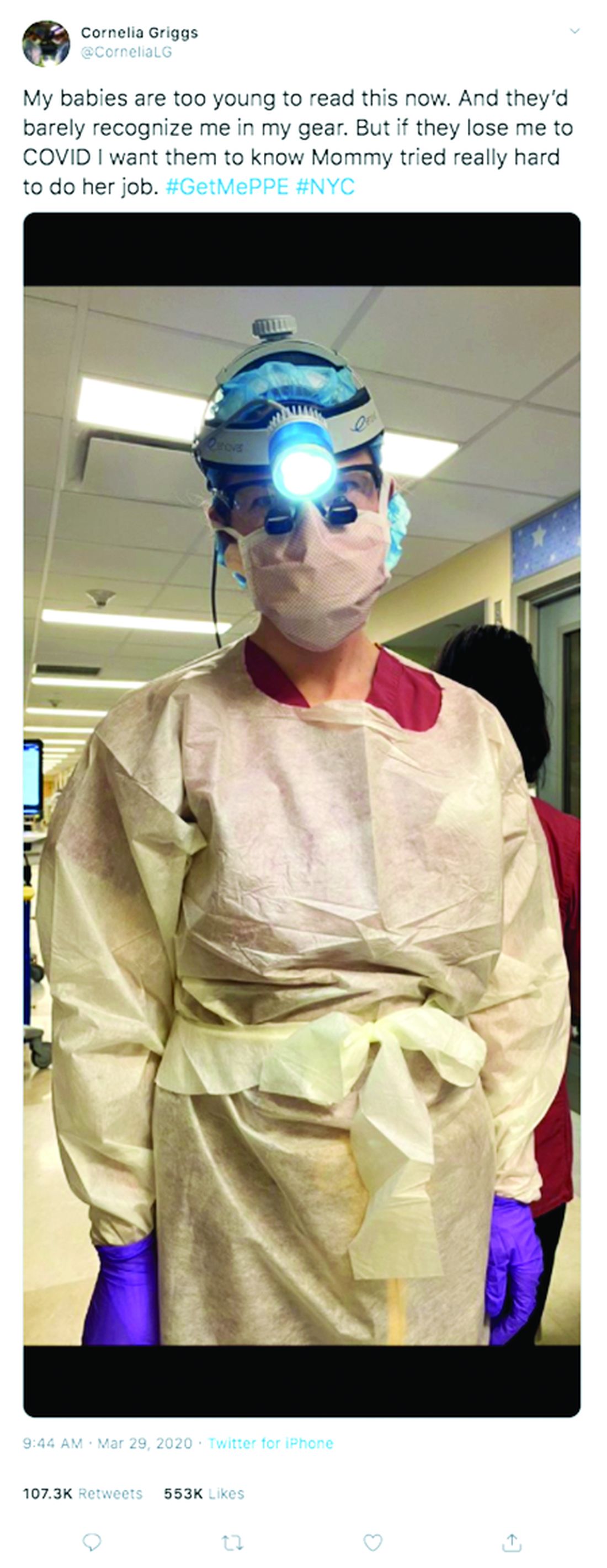

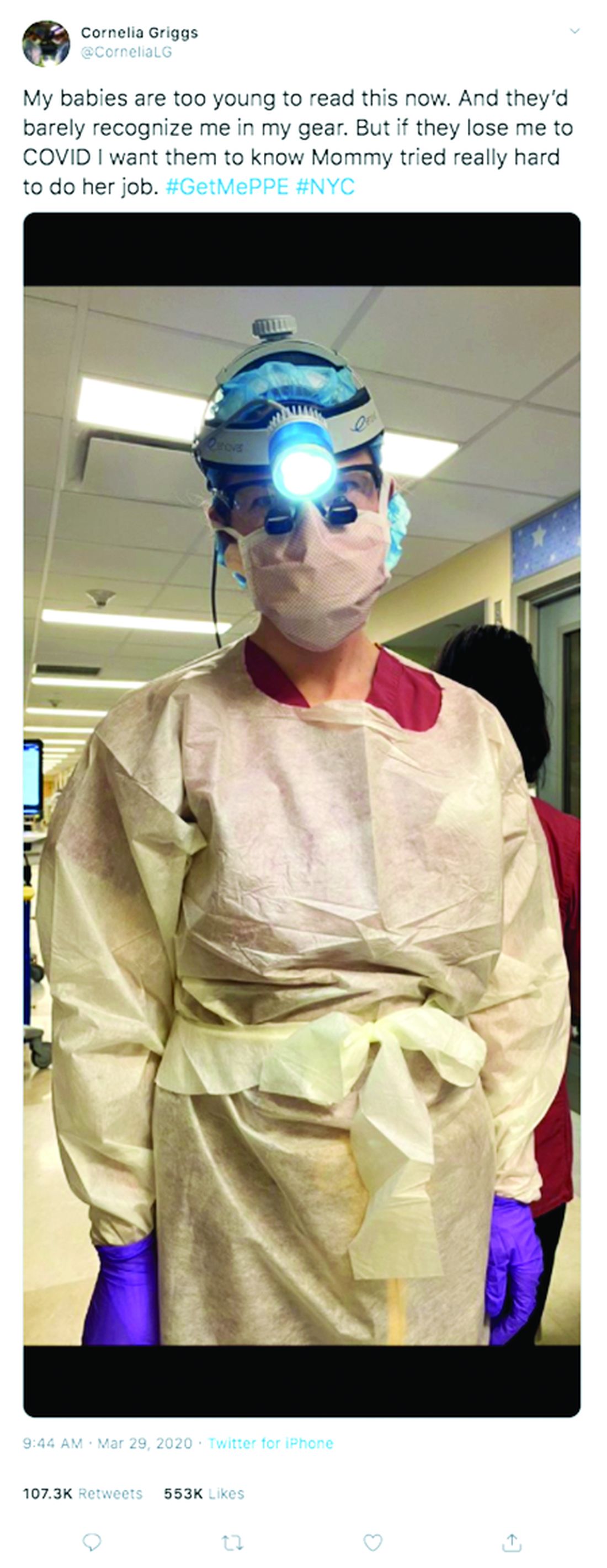

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Not long ago, weekends for Cornelia Griggs, MD, meant making trips to the grocery store, chasing after two active toddlers, and eating brunch with her husband after a busy work week. But life has changed dramatically for the family since the spread of COVID-19. On a recent weekend, Dr. Griggs and her husband, Robert Goldstone, MD, spent their days off drafting a will.

“We’re both doctors, and we know that health care workers have an increased risk of contracting COVID,” said Dr. Griggs, a pediatric surgery fellow at Columbia University Irving Medical Center in New York. “It felt like the responsible thing to do: Have a will in place to make sure our wishes are clear about who would manage our property and assets, and who would take care of our kids – God forbid.”

Outlining their final wishes is among many difficult decisions the doctors, both 36, have been forced to make in recent weeks. Dr. Goldstone, a general surgeon at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, is no longer returning to New York during his time off, said Dr. Griggs, who has had known COVID-19 exposures. The couple’s children, aged 4 and almost 2, are temporarily living with their grandparents in Connecticut to decrease their exposure risk.

“I felt like it was safer for all of them to be there while I was going back and forth from the hospital,” Dr. Griggs said. “My husband is in Boston. The kids are in Connecticut and I’m in New York. That inherently is hard because our whole family is split up. I don’t know when it will be safe for me to see them again.”

Health professional couples across the country are facing similar challenges as they navigate the risk of contracting COVID-19 at work, while trying to protect their families at home. From childcare dilemmas to quarantine quandaries to end-of-life considerations, partners who work in health care are confronting tough questions as the pandemic continues.

The biggest challenge is the uncertainty, says Angela Weyand, MD, an Ann Arbor, Mich.–based pediatric hematologist/oncologist who shares two young daughters with husband Ted Claflin, MD, a physical medicine and rehabilitation physician. Dr. Weyand said she and her husband are primarily working remotely now, but she knows that one or both could be deployed to the hospital to help care for patients, if the need arises. Nearby Detroit has been labeled a coronavirus “hot spot” by the U.S. Surgeon General.

“Right now, I think our biggest fear is spreading coronavirus to those we love, especially those in higher risk groups,” she said. “At the same time, we are also concerned about our own health and our future ability to be there for our children, a fear that, thankfully, neither one of us has ever had to face before. We are trying to take things one day at a time, acknowledging all that we have to be grateful for, and also learning to accept that many things right now are outside of our control.”

Dr. Weyand, 38, and her husband, 40, finalized their wills in March.

“We have been working on them for quite some time, but before now, there has never been any urgency,” Dr. Weyand said. “Hearing about the high rate of infection in health care workers and the increasing number of deaths in young healthy people made us realize that this should be a priority.”

Dallas internist Bethany Agusala, MD, 36, and her husband, Kartik Agusala, MD, 41, a cardiologist, recently spent time engaged in the same activity. The couple, who work for the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center, have two children, aged 2 and 4.

“The chances are hopefully small that something bad would happen to either one of us, but it just seemed like a good time to get [a will] in place,” Dr. Bethany Agusala said in an interview. “It’s never an easy thing to think about.

Pediatric surgeon Chethan Sathya, MD, 34, and his wife, 31, a physician assistant, have vastly altered their home routine to prevent the risk of exposure to their 16-month-old daughter. Dr. Sathya works for the Northwell Health System in New York, which has hundreds of hospitalized patients with COVID-19, Dr. Sathya said in an interview. He did not want to disclose his wife's name or institution, but said she works in a COVID-19 unit at a New York hospital.

When his wife returns home, she removes all of her clothes and places them in a bag, showers, and then isolates herself in the bedroom. Dr. Sathya brings his wife meals and then remains in a different room with their baby.

“It’s only been a few days,” he said. “We’re going to decide: Does she just stay in one room at all times or when she doesn’t work for a few days then after 1 day, can she come out? Should she get a hotel room elsewhere? These are the considerations.”

They employ an older nanny whom they also worry about, and with whom they try to limit contact, said Dr. Sathya, who practices at Cohen Children’s Medical Center. In a matter of weeks, Dr. Sathya anticipates he will be called upon to assist in some form with the COVID crisis.

“We haven’t figured that out. I’m not sure what we’ll do,” he said. “There is no perfect solution. You have to adapt. It’s very difficult to do so when you’re living in a condo in New York.”

For Dr. Griggs, life is much quieter at home without her husband and two “laughing, wiggly,” toddlers. Weekends are now defined by resting, video calls with her family, and exercising, when it’s safe, said Dr. Griggs, who recently penned a New York Times opinion piece about the pandemic and is also active on social media regarding personal protective equipment. She calls her husband her “rock” who never fails to put a smile on her face when they chat from across the miles. Her advice for other health care couples is to take it “one day at a time.”

“Don’t try to make plans weeks in advance or let your mind go to a dark place,” she said. “It’s so easy to feel overwhelmed. The only way to get through this is to focus on surviving each day.”

Editor's Note, 3/31/20: Due to incorrect information provided, the hospital where Dr. Sathya's wife works was misidentified. We have removed the name of that hospital. The story does not include his wife's employer, because Dr. Sathya did not have permission to disclose her workplace and she wishes to remain anonymous.

Dapagliflozin trial in CKD halted because of high efficacy

AstraZeneca has announced that the phase 3 DAPA-CKD trial for dapagliflozin (Farxiga) in patients with chronic kidney disease has been halted early because of overwhelming efficacy of the drug, at the recommendation of an independent data monitoring committee.