User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Men occupy most leadership roles in medicine

Since the early 2000s, approximately half of medical students in the United States – and in many years, more than half – have been women, but according to an update provided at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

In pediatrics, a specialty in which approximately 70% of physicians are now women, there has been progress, but still less than 30% of pediatric department chairs are female, said Vincent Chiang, MD, chief medical officer of Boston Children’s Hospital, during a presentation at the virtual meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Citing published data and a survey he personally conducted of the top children’s hospitals identified by the U.S. News and World Report, Dr. Chiang said a minority of division chiefs, chief medical officers, chief financial officers, and other leaders are female. At his institution, only 2 of 16 division chiefs are female.

“No matter how you slice it, women are underrepresented in leadership positions,” he noted.

The problem is certainly not confined to medicine. Dr. Chiang cited data showing that women and men have reached “near parity” in workforce participation in the United States even though the 20% earnings gap has changed little over time.

According to 2020 data from the World Economic Forum, the United States ranked 51 for the gender gap calculated on the basis of economic, political, educational, and health attainment. Even if this places the United States in the top third of the rankings, it is far behind Iceland and the Scandinavian countries that lead the list.

Efforts to reduce structural biases are part of the fix, but Dr. Chiang cautioned that fundamental changes might never occur if the plan is to wait for an approach based on meritocracy. He said that existing structural biases are “slanted away from women,” who are not necessarily granted the opportunities that are readily available to men.

“A meritocracy only works if the initial playing field was level. Otherwise, it just perpetuates the inequalities,” he said.

The problem is not a shortage of women with the skills to lead. In a study by Zenger/Folkman, a consulting company that works on leadership skill development, women performed better than men in 16 of 18 leadership categories, according to Dr. Chiang.

“There is certainly no shortage of capable women,” he noted.

Of the many issues, Dr. Chiang highlighted two. The first is the challenge of placing women on leadership pathways. This is likely to require proactive strategies, such as fast-track advancement programs that guide female candidates toward leadership roles.

The second is more nuanced. According to Dr. Chiang, women who want to assume a leadership role should think more actively about how and who is making decisions at their institution so they can position themselves appropriately. This is nuanced because “there is a certain amount of gamesmanship,” he said. The rise to leadership “has never been a pure meritocracy.”

Importantly, many of the key decisions in any institution involve money, according to Dr. Chiang. As a result, he advised those seeking leadership roles to join audit committees or otherwise take on responsibility for profit-and-loss management. Even in a nonprofit institution, “you need to make the numbers work,” he said, citing the common catchphrase: “No margin, no mission.”

However, Dr. Chiang acknowledged the many obstacles that prevent women from working their way into positions of leadership. For example, networking is important, but women are not necessarily attracted or invited to some of the social engagements, such as golf outings, where strong relationships are created.

In a survey of 100,000 people working at Fortune 500 companies, “82% of women say they feel excluded at work and much of that comes from that informal networking,” Dr. Chiang said. “Whereas 92% of men think they are not excluding women in their daily work.”

There is no single solution, but Dr. Chiang believes that concrete structural changes are needed. Female doctors remain grossly underrepresented in leadership roles even as they now represent more than half of the workforce for many specialties. Based on the need for proactive approaches outlined by Dr. Chiang, it appears unlikely that gender inequality will ever resolve itself.

Lisa S. Rotenstein, MD, who has written on fixing the gender imbalance in health care, including for the Harvard Business Review, said she agreed during an interview that structural changes are critical.

“In order to address current disparities, leaders should be thinking about how to remove both the formal and informal obstacles that prevent women and minorities from getting into the rooms where these decisions are being made,” said Dr. Rotenstein, who is an instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“This will need to involve sponsorship that gets women invited to the right committees or in positions with responsibility for profit-and-loss management,” she added.

Dr. Rotenstein spoke about improving “access to the pipeline” that leads to leadership roles. The ways in which women are excluded from opportunities is often subtle and difficult to penetrate without fundamental changes, she explained.

“Institutions need to understand the processes that lead to leadership roles and make the changes that allow women and minorities to participate,” she said. It is not enough to recognize the problem, according to Dr. Rotenstein.

Like Dr. Chiang, she noted that changes are needed in the methods that move underrepresented groups into leadership roles.

Dr. Chiang reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Since the early 2000s, approximately half of medical students in the United States – and in many years, more than half – have been women, but according to an update provided at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

In pediatrics, a specialty in which approximately 70% of physicians are now women, there has been progress, but still less than 30% of pediatric department chairs are female, said Vincent Chiang, MD, chief medical officer of Boston Children’s Hospital, during a presentation at the virtual meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Citing published data and a survey he personally conducted of the top children’s hospitals identified by the U.S. News and World Report, Dr. Chiang said a minority of division chiefs, chief medical officers, chief financial officers, and other leaders are female. At his institution, only 2 of 16 division chiefs are female.

“No matter how you slice it, women are underrepresented in leadership positions,” he noted.

The problem is certainly not confined to medicine. Dr. Chiang cited data showing that women and men have reached “near parity” in workforce participation in the United States even though the 20% earnings gap has changed little over time.

According to 2020 data from the World Economic Forum, the United States ranked 51 for the gender gap calculated on the basis of economic, political, educational, and health attainment. Even if this places the United States in the top third of the rankings, it is far behind Iceland and the Scandinavian countries that lead the list.

Efforts to reduce structural biases are part of the fix, but Dr. Chiang cautioned that fundamental changes might never occur if the plan is to wait for an approach based on meritocracy. He said that existing structural biases are “slanted away from women,” who are not necessarily granted the opportunities that are readily available to men.

“A meritocracy only works if the initial playing field was level. Otherwise, it just perpetuates the inequalities,” he said.

The problem is not a shortage of women with the skills to lead. In a study by Zenger/Folkman, a consulting company that works on leadership skill development, women performed better than men in 16 of 18 leadership categories, according to Dr. Chiang.

“There is certainly no shortage of capable women,” he noted.

Of the many issues, Dr. Chiang highlighted two. The first is the challenge of placing women on leadership pathways. This is likely to require proactive strategies, such as fast-track advancement programs that guide female candidates toward leadership roles.

The second is more nuanced. According to Dr. Chiang, women who want to assume a leadership role should think more actively about how and who is making decisions at their institution so they can position themselves appropriately. This is nuanced because “there is a certain amount of gamesmanship,” he said. The rise to leadership “has never been a pure meritocracy.”

Importantly, many of the key decisions in any institution involve money, according to Dr. Chiang. As a result, he advised those seeking leadership roles to join audit committees or otherwise take on responsibility for profit-and-loss management. Even in a nonprofit institution, “you need to make the numbers work,” he said, citing the common catchphrase: “No margin, no mission.”

However, Dr. Chiang acknowledged the many obstacles that prevent women from working their way into positions of leadership. For example, networking is important, but women are not necessarily attracted or invited to some of the social engagements, such as golf outings, where strong relationships are created.

In a survey of 100,000 people working at Fortune 500 companies, “82% of women say they feel excluded at work and much of that comes from that informal networking,” Dr. Chiang said. “Whereas 92% of men think they are not excluding women in their daily work.”

There is no single solution, but Dr. Chiang believes that concrete structural changes are needed. Female doctors remain grossly underrepresented in leadership roles even as they now represent more than half of the workforce for many specialties. Based on the need for proactive approaches outlined by Dr. Chiang, it appears unlikely that gender inequality will ever resolve itself.

Lisa S. Rotenstein, MD, who has written on fixing the gender imbalance in health care, including for the Harvard Business Review, said she agreed during an interview that structural changes are critical.

“In order to address current disparities, leaders should be thinking about how to remove both the formal and informal obstacles that prevent women and minorities from getting into the rooms where these decisions are being made,” said Dr. Rotenstein, who is an instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“This will need to involve sponsorship that gets women invited to the right committees or in positions with responsibility for profit-and-loss management,” she added.

Dr. Rotenstein spoke about improving “access to the pipeline” that leads to leadership roles. The ways in which women are excluded from opportunities is often subtle and difficult to penetrate without fundamental changes, she explained.

“Institutions need to understand the processes that lead to leadership roles and make the changes that allow women and minorities to participate,” she said. It is not enough to recognize the problem, according to Dr. Rotenstein.

Like Dr. Chiang, she noted that changes are needed in the methods that move underrepresented groups into leadership roles.

Dr. Chiang reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

Since the early 2000s, approximately half of medical students in the United States – and in many years, more than half – have been women, but according to an update provided at the virtual Pediatric Hospital Medicine.

In pediatrics, a specialty in which approximately 70% of physicians are now women, there has been progress, but still less than 30% of pediatric department chairs are female, said Vincent Chiang, MD, chief medical officer of Boston Children’s Hospital, during a presentation at the virtual meeting sponsored by the Society of Hospital Medicine, the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Academic Pediatric Association.

Citing published data and a survey he personally conducted of the top children’s hospitals identified by the U.S. News and World Report, Dr. Chiang said a minority of division chiefs, chief medical officers, chief financial officers, and other leaders are female. At his institution, only 2 of 16 division chiefs are female.

“No matter how you slice it, women are underrepresented in leadership positions,” he noted.

The problem is certainly not confined to medicine. Dr. Chiang cited data showing that women and men have reached “near parity” in workforce participation in the United States even though the 20% earnings gap has changed little over time.

According to 2020 data from the World Economic Forum, the United States ranked 51 for the gender gap calculated on the basis of economic, political, educational, and health attainment. Even if this places the United States in the top third of the rankings, it is far behind Iceland and the Scandinavian countries that lead the list.

Efforts to reduce structural biases are part of the fix, but Dr. Chiang cautioned that fundamental changes might never occur if the plan is to wait for an approach based on meritocracy. He said that existing structural biases are “slanted away from women,” who are not necessarily granted the opportunities that are readily available to men.

“A meritocracy only works if the initial playing field was level. Otherwise, it just perpetuates the inequalities,” he said.

The problem is not a shortage of women with the skills to lead. In a study by Zenger/Folkman, a consulting company that works on leadership skill development, women performed better than men in 16 of 18 leadership categories, according to Dr. Chiang.

“There is certainly no shortage of capable women,” he noted.

Of the many issues, Dr. Chiang highlighted two. The first is the challenge of placing women on leadership pathways. This is likely to require proactive strategies, such as fast-track advancement programs that guide female candidates toward leadership roles.

The second is more nuanced. According to Dr. Chiang, women who want to assume a leadership role should think more actively about how and who is making decisions at their institution so they can position themselves appropriately. This is nuanced because “there is a certain amount of gamesmanship,” he said. The rise to leadership “has never been a pure meritocracy.”

Importantly, many of the key decisions in any institution involve money, according to Dr. Chiang. As a result, he advised those seeking leadership roles to join audit committees or otherwise take on responsibility for profit-and-loss management. Even in a nonprofit institution, “you need to make the numbers work,” he said, citing the common catchphrase: “No margin, no mission.”

However, Dr. Chiang acknowledged the many obstacles that prevent women from working their way into positions of leadership. For example, networking is important, but women are not necessarily attracted or invited to some of the social engagements, such as golf outings, where strong relationships are created.

In a survey of 100,000 people working at Fortune 500 companies, “82% of women say they feel excluded at work and much of that comes from that informal networking,” Dr. Chiang said. “Whereas 92% of men think they are not excluding women in their daily work.”

There is no single solution, but Dr. Chiang believes that concrete structural changes are needed. Female doctors remain grossly underrepresented in leadership roles even as they now represent more than half of the workforce for many specialties. Based on the need for proactive approaches outlined by Dr. Chiang, it appears unlikely that gender inequality will ever resolve itself.

Lisa S. Rotenstein, MD, who has written on fixing the gender imbalance in health care, including for the Harvard Business Review, said she agreed during an interview that structural changes are critical.

“In order to address current disparities, leaders should be thinking about how to remove both the formal and informal obstacles that prevent women and minorities from getting into the rooms where these decisions are being made,” said Dr. Rotenstein, who is an instructor in medicine at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School in Boston.

“This will need to involve sponsorship that gets women invited to the right committees or in positions with responsibility for profit-and-loss management,” she added.

Dr. Rotenstein spoke about improving “access to the pipeline” that leads to leadership roles. The ways in which women are excluded from opportunities is often subtle and difficult to penetrate without fundamental changes, she explained.

“Institutions need to understand the processes that lead to leadership roles and make the changes that allow women and minorities to participate,” she said. It is not enough to recognize the problem, according to Dr. Rotenstein.

Like Dr. Chiang, she noted that changes are needed in the methods that move underrepresented groups into leadership roles.

Dr. Chiang reported no potential conflicts of interest relevant to this study.

FROM PHM20

Intravesical BCG dosing frequency ‘critical’ in bladder cancer

The rates of recurrence were 27.1% in the reduced dosing frequency arm and 12% in the standard dosing frequency arm. These results were reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Association of Urology.

More patients in the reduced dosing frequency arm than in the standard dosing frequency arm had a shorter time to recurrence, which was the primary endpoint of the trial.

At 6 months, the rate of recurrence was 18% in the reduced frequency arm and 8% in the standard frequency arm. The gap widened further at both 12 months (24% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (34% and 15%, respectively). The hazard ratio for time to recurrence was 0.403 in favor of the standard dosing frequency arm.

“The recommended dose and schedule of BCG consists of once-weekly installations during 6 weeks of induction, followed by 3 weeks of maintenance at 3, 6, and 12 months,” observed study investigator Marc-Oliver Grimm, MD, of Jena (Germany) University Hospital.

“BCG instillation is, however, frequently associated with adverse events, which may lead to discontinuation, and several attempts have been made to reduce symptom burden associated with BCG,” he added.

Dr. Grimm presented the recently published findings from NIMBUS (Eur Urol. 2020 May 20;S0302-2838[20]30334-1) alongside some new information from a post hoc analysis.

Trial details

NIMBUS was a randomized, unblinded study of 345 patients with high-grade NMIBC who were recruited over a prolonged period, Dr. Grimm said. The long accrual was caused by a shortage of BCG and meant that the statistical assumptions had to be revised to include fewer patients.

The trial was designed to compare induction consisting of three versus six weekly BCG instillations and maintenance consisting of two versus three weekly BCG instillations at 3, 6, and 12 months. The aim had been to show that a reduced dosing frequency of BCG – 9 rather than 15 instillations – was noninferior to the standard dosing frequency of BCG, Dr. Grimm said. However, that was not the case, and the trial had to be stopped prematurely. In October 2019, the study’s sponsor, the EAU Research Foundation, announced that the trial would end.

Despite its unexpected ending, the trial’s data now fill some knowledge gaps, as pointed out by the discussant for the trial, Peter Black, MD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Previous studies, such as the SWOG 8507, EORTC 30962, and CUETO 98013 trials, had shown that maintenance treatment works, but the schedule matters, he said. Results have also shown that the duration of maintenance treatment is less important than the dose of BCG given.

“The NIMBUS trial now tells us that dosing frequency is critical,” Dr. Black said.

Not only did the NIMBUS trial alter the maintenance schedule, it also altered the induction course of BCG instillation.

“The dramatic difference in recurrence-free survival, especially with the large separation of K-M [Kaplan-Meier] curves early on, suggests that this change to induction has had a major impact on the outcomes,” Dr. Black observed.

Post hoc analysis

Dr. Grimm presented a post hoc analysis comparing the rates of recurrence in the NIMBUS trial with rates seen in the EORTC 30962 and CUETO 98013 trials. Dr. Black also compared NIMBUS results to results from the SWOG 8507 trial.

The analysis showed lower rates of recurrence in the standard dose frequency arm in the NIMBUS trial than in the EORTC and CUETO trials at both 12 months (11%, 25%, and 18%, respectively) and 24 months (15%, 32%, and 27%, respectively).

However, as Dr. Black pointed out, the SWOG trial had similar recurrence rates as the NIMBUS trial at 12 months (9% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (19% and 15%, respectively).

Dr. Grimm suggested that the lower rates of recurrence in the standard dosing arm of NIMBUS versus the other trials might have been because 91% of patients in the NIMBUS trial having undergone repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor before BCG instillation.

Dr. Black said while this might have had an effect, it was probably not the only answer. While it’s true that the other trials had not considered repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor, there were other confounding factors that might have been important, from patient selection bias to the use of advanced cystoscopy technologies, he said.

“If we really want to discern differences between surgery and intravesical therapy, we need to focus on CIS [carcinoma in situ] patients. Although this has major implications on feasibility since the patient pool is smaller,” Dr. Black said.

“One final point I’d like to make is that we really need to use these trials to understand the biology of non–muscle invasive bladder cancer,” he said. ”We know that BCG induces a cellular response, and we can measure this, as well as cytokine response. We know that the response builds to a plateau over four to six doses of induction and over two to three doses of maintenance therapy. This is perhaps more rapid in patients with pre-existing BCG immune reactivity. But there is biological rationale for the current six-plus-three protocol, and I think the reduced dose frequency in the NIMBUS trial probably failed to achieve the same immune activation as the established protocol.”

“If we were faced with a BCG shortage, it is better to reduce dose or duration of therapy but not the frequency of dosing,” Dr. Black added.

The NIMBUS trial was sponsored by the EAU Research Foundation. Dr. Grimm disclosed ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and many other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Black had no conflicts of interests relevant to his comments.

SOURCE: Grimm M-O. EAU20. https://urosource.uroweb.org/resource-centre/EAU20V/212877/Abstract/

The rates of recurrence were 27.1% in the reduced dosing frequency arm and 12% in the standard dosing frequency arm. These results were reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Association of Urology.

More patients in the reduced dosing frequency arm than in the standard dosing frequency arm had a shorter time to recurrence, which was the primary endpoint of the trial.

At 6 months, the rate of recurrence was 18% in the reduced frequency arm and 8% in the standard frequency arm. The gap widened further at both 12 months (24% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (34% and 15%, respectively). The hazard ratio for time to recurrence was 0.403 in favor of the standard dosing frequency arm.

“The recommended dose and schedule of BCG consists of once-weekly installations during 6 weeks of induction, followed by 3 weeks of maintenance at 3, 6, and 12 months,” observed study investigator Marc-Oliver Grimm, MD, of Jena (Germany) University Hospital.

“BCG instillation is, however, frequently associated with adverse events, which may lead to discontinuation, and several attempts have been made to reduce symptom burden associated with BCG,” he added.

Dr. Grimm presented the recently published findings from NIMBUS (Eur Urol. 2020 May 20;S0302-2838[20]30334-1) alongside some new information from a post hoc analysis.

Trial details

NIMBUS was a randomized, unblinded study of 345 patients with high-grade NMIBC who were recruited over a prolonged period, Dr. Grimm said. The long accrual was caused by a shortage of BCG and meant that the statistical assumptions had to be revised to include fewer patients.

The trial was designed to compare induction consisting of three versus six weekly BCG instillations and maintenance consisting of two versus three weekly BCG instillations at 3, 6, and 12 months. The aim had been to show that a reduced dosing frequency of BCG – 9 rather than 15 instillations – was noninferior to the standard dosing frequency of BCG, Dr. Grimm said. However, that was not the case, and the trial had to be stopped prematurely. In October 2019, the study’s sponsor, the EAU Research Foundation, announced that the trial would end.

Despite its unexpected ending, the trial’s data now fill some knowledge gaps, as pointed out by the discussant for the trial, Peter Black, MD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Previous studies, such as the SWOG 8507, EORTC 30962, and CUETO 98013 trials, had shown that maintenance treatment works, but the schedule matters, he said. Results have also shown that the duration of maintenance treatment is less important than the dose of BCG given.

“The NIMBUS trial now tells us that dosing frequency is critical,” Dr. Black said.

Not only did the NIMBUS trial alter the maintenance schedule, it also altered the induction course of BCG instillation.

“The dramatic difference in recurrence-free survival, especially with the large separation of K-M [Kaplan-Meier] curves early on, suggests that this change to induction has had a major impact on the outcomes,” Dr. Black observed.

Post hoc analysis

Dr. Grimm presented a post hoc analysis comparing the rates of recurrence in the NIMBUS trial with rates seen in the EORTC 30962 and CUETO 98013 trials. Dr. Black also compared NIMBUS results to results from the SWOG 8507 trial.

The analysis showed lower rates of recurrence in the standard dose frequency arm in the NIMBUS trial than in the EORTC and CUETO trials at both 12 months (11%, 25%, and 18%, respectively) and 24 months (15%, 32%, and 27%, respectively).

However, as Dr. Black pointed out, the SWOG trial had similar recurrence rates as the NIMBUS trial at 12 months (9% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (19% and 15%, respectively).

Dr. Grimm suggested that the lower rates of recurrence in the standard dosing arm of NIMBUS versus the other trials might have been because 91% of patients in the NIMBUS trial having undergone repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor before BCG instillation.

Dr. Black said while this might have had an effect, it was probably not the only answer. While it’s true that the other trials had not considered repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor, there were other confounding factors that might have been important, from patient selection bias to the use of advanced cystoscopy technologies, he said.

“If we really want to discern differences between surgery and intravesical therapy, we need to focus on CIS [carcinoma in situ] patients. Although this has major implications on feasibility since the patient pool is smaller,” Dr. Black said.

“One final point I’d like to make is that we really need to use these trials to understand the biology of non–muscle invasive bladder cancer,” he said. ”We know that BCG induces a cellular response, and we can measure this, as well as cytokine response. We know that the response builds to a plateau over four to six doses of induction and over two to three doses of maintenance therapy. This is perhaps more rapid in patients with pre-existing BCG immune reactivity. But there is biological rationale for the current six-plus-three protocol, and I think the reduced dose frequency in the NIMBUS trial probably failed to achieve the same immune activation as the established protocol.”

“If we were faced with a BCG shortage, it is better to reduce dose or duration of therapy but not the frequency of dosing,” Dr. Black added.

The NIMBUS trial was sponsored by the EAU Research Foundation. Dr. Grimm disclosed ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and many other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Black had no conflicts of interests relevant to his comments.

SOURCE: Grimm M-O. EAU20. https://urosource.uroweb.org/resource-centre/EAU20V/212877/Abstract/

The rates of recurrence were 27.1% in the reduced dosing frequency arm and 12% in the standard dosing frequency arm. These results were reported at the virtual annual congress of the European Association of Urology.

More patients in the reduced dosing frequency arm than in the standard dosing frequency arm had a shorter time to recurrence, which was the primary endpoint of the trial.

At 6 months, the rate of recurrence was 18% in the reduced frequency arm and 8% in the standard frequency arm. The gap widened further at both 12 months (24% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (34% and 15%, respectively). The hazard ratio for time to recurrence was 0.403 in favor of the standard dosing frequency arm.

“The recommended dose and schedule of BCG consists of once-weekly installations during 6 weeks of induction, followed by 3 weeks of maintenance at 3, 6, and 12 months,” observed study investigator Marc-Oliver Grimm, MD, of Jena (Germany) University Hospital.

“BCG instillation is, however, frequently associated with adverse events, which may lead to discontinuation, and several attempts have been made to reduce symptom burden associated with BCG,” he added.

Dr. Grimm presented the recently published findings from NIMBUS (Eur Urol. 2020 May 20;S0302-2838[20]30334-1) alongside some new information from a post hoc analysis.

Trial details

NIMBUS was a randomized, unblinded study of 345 patients with high-grade NMIBC who were recruited over a prolonged period, Dr. Grimm said. The long accrual was caused by a shortage of BCG and meant that the statistical assumptions had to be revised to include fewer patients.

The trial was designed to compare induction consisting of three versus six weekly BCG instillations and maintenance consisting of two versus three weekly BCG instillations at 3, 6, and 12 months. The aim had been to show that a reduced dosing frequency of BCG – 9 rather than 15 instillations – was noninferior to the standard dosing frequency of BCG, Dr. Grimm said. However, that was not the case, and the trial had to be stopped prematurely. In October 2019, the study’s sponsor, the EAU Research Foundation, announced that the trial would end.

Despite its unexpected ending, the trial’s data now fill some knowledge gaps, as pointed out by the discussant for the trial, Peter Black, MD, of the University of British Columbia in Vancouver.

Previous studies, such as the SWOG 8507, EORTC 30962, and CUETO 98013 trials, had shown that maintenance treatment works, but the schedule matters, he said. Results have also shown that the duration of maintenance treatment is less important than the dose of BCG given.

“The NIMBUS trial now tells us that dosing frequency is critical,” Dr. Black said.

Not only did the NIMBUS trial alter the maintenance schedule, it also altered the induction course of BCG instillation.

“The dramatic difference in recurrence-free survival, especially with the large separation of K-M [Kaplan-Meier] curves early on, suggests that this change to induction has had a major impact on the outcomes,” Dr. Black observed.

Post hoc analysis

Dr. Grimm presented a post hoc analysis comparing the rates of recurrence in the NIMBUS trial with rates seen in the EORTC 30962 and CUETO 98013 trials. Dr. Black also compared NIMBUS results to results from the SWOG 8507 trial.

The analysis showed lower rates of recurrence in the standard dose frequency arm in the NIMBUS trial than in the EORTC and CUETO trials at both 12 months (11%, 25%, and 18%, respectively) and 24 months (15%, 32%, and 27%, respectively).

However, as Dr. Black pointed out, the SWOG trial had similar recurrence rates as the NIMBUS trial at 12 months (9% and 11%, respectively) and 24 months (19% and 15%, respectively).

Dr. Grimm suggested that the lower rates of recurrence in the standard dosing arm of NIMBUS versus the other trials might have been because 91% of patients in the NIMBUS trial having undergone repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor before BCG instillation.

Dr. Black said while this might have had an effect, it was probably not the only answer. While it’s true that the other trials had not considered repeat transurethral resection for bladder tumor, there were other confounding factors that might have been important, from patient selection bias to the use of advanced cystoscopy technologies, he said.

“If we really want to discern differences between surgery and intravesical therapy, we need to focus on CIS [carcinoma in situ] patients. Although this has major implications on feasibility since the patient pool is smaller,” Dr. Black said.

“One final point I’d like to make is that we really need to use these trials to understand the biology of non–muscle invasive bladder cancer,” he said. ”We know that BCG induces a cellular response, and we can measure this, as well as cytokine response. We know that the response builds to a plateau over four to six doses of induction and over two to three doses of maintenance therapy. This is perhaps more rapid in patients with pre-existing BCG immune reactivity. But there is biological rationale for the current six-plus-three protocol, and I think the reduced dose frequency in the NIMBUS trial probably failed to achieve the same immune activation as the established protocol.”

“If we were faced with a BCG shortage, it is better to reduce dose or duration of therapy but not the frequency of dosing,” Dr. Black added.

The NIMBUS trial was sponsored by the EAU Research Foundation. Dr. Grimm disclosed ties to Novartis, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and many other pharmaceutical companies. Dr. Black had no conflicts of interests relevant to his comments.

SOURCE: Grimm M-O. EAU20. https://urosource.uroweb.org/resource-centre/EAU20V/212877/Abstract/

FROM EAU20

FDA allows qualified claims for UTI risk reduction with cranberry products

The Food and Drug Administration will not object to qualified health claims that consumption of certain cranberry juice products and cranberry supplement products may reduce the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections in otherwise healthy women.

In a letter of enforcement discretion issued on July 21, the FDA responded to a health claim petition submitted by Ocean Spray Cranberries. “A health claim characterizes the relationship between a substance and a disease or health-related condition,” according to the FDA. Ocean Spray Cranberries asked the FDA for an authorized health claim regarding the relationship between the consumption of cranberry beverages and supplements and a reduction in the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) in healthy women.

After reviewing the evidence, the FDA determined that the existing science did not support an authorized health claim, but did allow for a qualified health claim for certain cranberry juice beverages and supplements. A qualified health claim does not constitute an FDA approval; the FDA instead issues a Letter of Enforcement Discretion that includes language reflecting the level of scientific evidence for the claim.

The currently available scientific evidence for a relationship between cranberry and recurrent UTIs includes five intervention studies, according to the FDA letter. Two of these were high-quality, randomized, controlled trials in which daily consumption of a cranberry juice beverage was significantly associated with a reduced risk of recurrent UTIs. Another randomized, controlled trial yielded mixed results, and two other intervention studies that were moderate-quality, randomized, controlled trials showed no effect of cranberry juice consumption on UTI risk reduction.

The FDA’s letter of enforcement discretion states that, with regard to cranberry juice beverages, “Limited and inconsistent scientific evidence shows that by consuming one serving (8 oz) each day of a cranberry juice beverage, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

Similarly, for cranberry dietary supplements, the FDA states that “Limited scientific evidence shows that, by consuming 500 mg each day of cranberry dietary supplement, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

The qualified health claims apply specifically to cranberry juice beverages that contain at least 27% cranberry juice, and cranberry dietary supplements containing at least 500 mg of cranberry fruit powder. “The claims do not include other conventional foods or food products made from or containing cranberries, such as dried cranberries or cranberry sauce,” according to the FDA statement.

“With recurrent UTI, a major concern is the frequent use of antibiotics,” Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington and an assistant clinical professor at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“The challenge is to identify habits and/or nonantibiotic treatment to prevent recurrent UTI and decrease the need for antibiotics,” she said. “The regular use of cranberry can decrease the frequency of UTI in some, but not all, people.

“It does not appear to mask the symptoms of a UTI, so if it is not effective to prevent the infection, the presumptive diagnosis can be made based on the common symptoms,” she explained.

Dr. Bohon said that she has recommended the use of cranberry to some of her patients who have recurrent UTIs and has had success with many of them.

“I think it is important to make it clear that cranberry can be beneficial for some patients to decrease the frequency of UTI. It will not be effective for everyone who has frequent UTI, but for those who use it and have fewer UTIs, there will be less frequent exposure to antibiotics,” she emphasized. “What we need to know is who benefits the most from cranberry to prevent recurrent UTIs; whether age, race, coexisting health problems [such as diabetes], and use of hormonal contraception or menopause impact on its success.”

Dr. Bohon had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The Food and Drug Administration will not object to qualified health claims that consumption of certain cranberry juice products and cranberry supplement products may reduce the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections in otherwise healthy women.

In a letter of enforcement discretion issued on July 21, the FDA responded to a health claim petition submitted by Ocean Spray Cranberries. “A health claim characterizes the relationship between a substance and a disease or health-related condition,” according to the FDA. Ocean Spray Cranberries asked the FDA for an authorized health claim regarding the relationship between the consumption of cranberry beverages and supplements and a reduction in the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) in healthy women.

After reviewing the evidence, the FDA determined that the existing science did not support an authorized health claim, but did allow for a qualified health claim for certain cranberry juice beverages and supplements. A qualified health claim does not constitute an FDA approval; the FDA instead issues a Letter of Enforcement Discretion that includes language reflecting the level of scientific evidence for the claim.

The currently available scientific evidence for a relationship between cranberry and recurrent UTIs includes five intervention studies, according to the FDA letter. Two of these were high-quality, randomized, controlled trials in which daily consumption of a cranberry juice beverage was significantly associated with a reduced risk of recurrent UTIs. Another randomized, controlled trial yielded mixed results, and two other intervention studies that were moderate-quality, randomized, controlled trials showed no effect of cranberry juice consumption on UTI risk reduction.

The FDA’s letter of enforcement discretion states that, with regard to cranberry juice beverages, “Limited and inconsistent scientific evidence shows that by consuming one serving (8 oz) each day of a cranberry juice beverage, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

Similarly, for cranberry dietary supplements, the FDA states that “Limited scientific evidence shows that, by consuming 500 mg each day of cranberry dietary supplement, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

The qualified health claims apply specifically to cranberry juice beverages that contain at least 27% cranberry juice, and cranberry dietary supplements containing at least 500 mg of cranberry fruit powder. “The claims do not include other conventional foods or food products made from or containing cranberries, such as dried cranberries or cranberry sauce,” according to the FDA statement.

“With recurrent UTI, a major concern is the frequent use of antibiotics,” Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington and an assistant clinical professor at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“The challenge is to identify habits and/or nonantibiotic treatment to prevent recurrent UTI and decrease the need for antibiotics,” she said. “The regular use of cranberry can decrease the frequency of UTI in some, but not all, people.

“It does not appear to mask the symptoms of a UTI, so if it is not effective to prevent the infection, the presumptive diagnosis can be made based on the common symptoms,” she explained.

Dr. Bohon said that she has recommended the use of cranberry to some of her patients who have recurrent UTIs and has had success with many of them.

“I think it is important to make it clear that cranberry can be beneficial for some patients to decrease the frequency of UTI. It will not be effective for everyone who has frequent UTI, but for those who use it and have fewer UTIs, there will be less frequent exposure to antibiotics,” she emphasized. “What we need to know is who benefits the most from cranberry to prevent recurrent UTIs; whether age, race, coexisting health problems [such as diabetes], and use of hormonal contraception or menopause impact on its success.”

Dr. Bohon had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

The Food and Drug Administration will not object to qualified health claims that consumption of certain cranberry juice products and cranberry supplement products may reduce the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections in otherwise healthy women.

In a letter of enforcement discretion issued on July 21, the FDA responded to a health claim petition submitted by Ocean Spray Cranberries. “A health claim characterizes the relationship between a substance and a disease or health-related condition,” according to the FDA. Ocean Spray Cranberries asked the FDA for an authorized health claim regarding the relationship between the consumption of cranberry beverages and supplements and a reduction in the risk of recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs) in healthy women.

After reviewing the evidence, the FDA determined that the existing science did not support an authorized health claim, but did allow for a qualified health claim for certain cranberry juice beverages and supplements. A qualified health claim does not constitute an FDA approval; the FDA instead issues a Letter of Enforcement Discretion that includes language reflecting the level of scientific evidence for the claim.

The currently available scientific evidence for a relationship between cranberry and recurrent UTIs includes five intervention studies, according to the FDA letter. Two of these were high-quality, randomized, controlled trials in which daily consumption of a cranberry juice beverage was significantly associated with a reduced risk of recurrent UTIs. Another randomized, controlled trial yielded mixed results, and two other intervention studies that were moderate-quality, randomized, controlled trials showed no effect of cranberry juice consumption on UTI risk reduction.

The FDA’s letter of enforcement discretion states that, with regard to cranberry juice beverages, “Limited and inconsistent scientific evidence shows that by consuming one serving (8 oz) each day of a cranberry juice beverage, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

Similarly, for cranberry dietary supplements, the FDA states that “Limited scientific evidence shows that, by consuming 500 mg each day of cranberry dietary supplement, healthy women who have had a urinary tract infection may reduce their risk of recurrent UTI.”

The qualified health claims apply specifically to cranberry juice beverages that contain at least 27% cranberry juice, and cranberry dietary supplements containing at least 500 mg of cranberry fruit powder. “The claims do not include other conventional foods or food products made from or containing cranberries, such as dried cranberries or cranberry sauce,” according to the FDA statement.

“With recurrent UTI, a major concern is the frequent use of antibiotics,” Constance Bohon, MD, an ob.gyn. in private practice in Washington and an assistant clinical professor at George Washington University, Washington, said in an interview.

“The challenge is to identify habits and/or nonantibiotic treatment to prevent recurrent UTI and decrease the need for antibiotics,” she said. “The regular use of cranberry can decrease the frequency of UTI in some, but not all, people.

“It does not appear to mask the symptoms of a UTI, so if it is not effective to prevent the infection, the presumptive diagnosis can be made based on the common symptoms,” she explained.

Dr. Bohon said that she has recommended the use of cranberry to some of her patients who have recurrent UTIs and has had success with many of them.

“I think it is important to make it clear that cranberry can be beneficial for some patients to decrease the frequency of UTI. It will not be effective for everyone who has frequent UTI, but for those who use it and have fewer UTIs, there will be less frequent exposure to antibiotics,” she emphasized. “What we need to know is who benefits the most from cranberry to prevent recurrent UTIs; whether age, race, coexisting health problems [such as diabetes], and use of hormonal contraception or menopause impact on its success.”

Dr. Bohon had no relevant financial conflicts to disclose.

Rapid drop of antibodies seen in those with mild COVID-19

The research was conducted by F. Javier Ibarrondo, PhD, and colleagues and was published online on July 21 in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Ibarrondo is associate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. (The original letter incorrectly calculated the half-life at 73 days.)

Coauthor Otto Yang, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at UCLA, told Medscape Medical News that the rapidity in the antibody drop at 5 weeks “is striking compared to other infections.”

The phenomenon has been suspected and has been observed before but had not been quantified.

“Our paper is the first to put firm numbers on the dropping of antibodies after early infection,” he said.

The researchers evaluated 34 people (average age, 43 years) who had recovered from mild COVID-19 and had referred themselves to UCLA for observational research.

Previous report also found a quick fade

As Medscape Medical News reported, a previous study from China that was published in Nature Medicine also found that the antibodies fade quickly.

Interpreting the meaning of the current research comes with a few caveats, Dr. Yang said.

“One is that we don’t know for sure that antibodies are what protect people from getting infected,” he said. Although it’s a reasonable assumption, he said, that’s not always the case.

Another caveat is that even if antibodies do protect, the tests being used to measure them – including the test that was used in this study – may not measure them the right way, and it is not yet known how many antibodies are needed for protection, he explained.

The UCLA researchers used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor–binding domain immunoglobulin G concentrations.

“No reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically”

The study provides further proof that “[t]here’s no reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically right now,” Dr. Yang said.

Additionally, “FDA-approved tests are not approved for quantitative measures, only qualitative,” he continued. He noted that the findings may have implications with respect to herd immunity.

“Herd immunity depends on a lot of people having immunity to the infection all at the same time. If infection is followed by only brief protection from infection, the natural infection is not going to reach herd immunity,” he explained.

Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, associate professor of pediatrics and director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program in Nashville, Tenn., pointed out that antibodies “are just part of the story.”

“When we make an immune response to any germ,” he said, “we not only make an immune response for the time being but for the future. The next time we’re exposed, we can call into action B cells and T cells who have been there and done that.”

So even though the antibodies fade over time, other arms of the immune system are being trained for future action, he said.

Herd immunity does not require that populations have a huge level of antibodies that remains forever, he explained.

“It requires that in general, we’re not going to get infected as easily, and we’re not going to have disease as easily, and we’re not going to transmit the virus for as long,” he said.

Dr. Creech said he and others researching COVID-19 find that studies that show that antibodies fade quickly provide more proof “that this coronavirus is going to be here to stay unless we can take care of it through very effective treatments to take it from potentially fatal disease to one that is nothing more than a cold” or until a vaccine is developed.

He noted there are four other coronaviruses in widespread circulation every year that “amount to about 25% of the common cold.”

This study may help narrow the window as to when convalescent plasma – plasma that is taken from people who have recovered from COVID-19 and that is used to help people who are acutely ill with the disease – will be most effective, Dr. Creech explained. He said the results suggest that it is important that plasma be collected within the first couple of months after recovery so as to capture the most antibodies.

This study is important as another snapshot “so we understand the differences between severe and mild disease, so we can study it over time, so we have all the tools we need as we start these pivotal vaccine studies to make sure we’re making the right immune response for the right duration of time so we can put an end to this pandemic,” Dr. Creech concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust, and the McCarthy Family Foundation. A coauthor reports receiving grants from Gilead outside the submitted work. Dr. Creech has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The research was conducted by F. Javier Ibarrondo, PhD, and colleagues and was published online on July 21 in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Ibarrondo is associate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. (The original letter incorrectly calculated the half-life at 73 days.)

Coauthor Otto Yang, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at UCLA, told Medscape Medical News that the rapidity in the antibody drop at 5 weeks “is striking compared to other infections.”

The phenomenon has been suspected and has been observed before but had not been quantified.

“Our paper is the first to put firm numbers on the dropping of antibodies after early infection,” he said.

The researchers evaluated 34 people (average age, 43 years) who had recovered from mild COVID-19 and had referred themselves to UCLA for observational research.

Previous report also found a quick fade

As Medscape Medical News reported, a previous study from China that was published in Nature Medicine also found that the antibodies fade quickly.

Interpreting the meaning of the current research comes with a few caveats, Dr. Yang said.

“One is that we don’t know for sure that antibodies are what protect people from getting infected,” he said. Although it’s a reasonable assumption, he said, that’s not always the case.

Another caveat is that even if antibodies do protect, the tests being used to measure them – including the test that was used in this study – may not measure them the right way, and it is not yet known how many antibodies are needed for protection, he explained.

The UCLA researchers used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor–binding domain immunoglobulin G concentrations.

“No reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically”

The study provides further proof that “[t]here’s no reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically right now,” Dr. Yang said.

Additionally, “FDA-approved tests are not approved for quantitative measures, only qualitative,” he continued. He noted that the findings may have implications with respect to herd immunity.

“Herd immunity depends on a lot of people having immunity to the infection all at the same time. If infection is followed by only brief protection from infection, the natural infection is not going to reach herd immunity,” he explained.

Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, associate professor of pediatrics and director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program in Nashville, Tenn., pointed out that antibodies “are just part of the story.”

“When we make an immune response to any germ,” he said, “we not only make an immune response for the time being but for the future. The next time we’re exposed, we can call into action B cells and T cells who have been there and done that.”

So even though the antibodies fade over time, other arms of the immune system are being trained for future action, he said.

Herd immunity does not require that populations have a huge level of antibodies that remains forever, he explained.

“It requires that in general, we’re not going to get infected as easily, and we’re not going to have disease as easily, and we’re not going to transmit the virus for as long,” he said.

Dr. Creech said he and others researching COVID-19 find that studies that show that antibodies fade quickly provide more proof “that this coronavirus is going to be here to stay unless we can take care of it through very effective treatments to take it from potentially fatal disease to one that is nothing more than a cold” or until a vaccine is developed.

He noted there are four other coronaviruses in widespread circulation every year that “amount to about 25% of the common cold.”

This study may help narrow the window as to when convalescent plasma – plasma that is taken from people who have recovered from COVID-19 and that is used to help people who are acutely ill with the disease – will be most effective, Dr. Creech explained. He said the results suggest that it is important that plasma be collected within the first couple of months after recovery so as to capture the most antibodies.

This study is important as another snapshot “so we understand the differences between severe and mild disease, so we can study it over time, so we have all the tools we need as we start these pivotal vaccine studies to make sure we’re making the right immune response for the right duration of time so we can put an end to this pandemic,” Dr. Creech concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust, and the McCarthy Family Foundation. A coauthor reports receiving grants from Gilead outside the submitted work. Dr. Creech has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The research was conducted by F. Javier Ibarrondo, PhD, and colleagues and was published online on July 21 in a letter to the editor of the New England Journal of Medicine. Ibarrondo is associate researcher at the University of California, Los Angeles. (The original letter incorrectly calculated the half-life at 73 days.)

Coauthor Otto Yang, MD, professor of medicine in the division of infectious diseases at UCLA, told Medscape Medical News that the rapidity in the antibody drop at 5 weeks “is striking compared to other infections.”

The phenomenon has been suspected and has been observed before but had not been quantified.

“Our paper is the first to put firm numbers on the dropping of antibodies after early infection,” he said.

The researchers evaluated 34 people (average age, 43 years) who had recovered from mild COVID-19 and had referred themselves to UCLA for observational research.

Previous report also found a quick fade

As Medscape Medical News reported, a previous study from China that was published in Nature Medicine also found that the antibodies fade quickly.

Interpreting the meaning of the current research comes with a few caveats, Dr. Yang said.

“One is that we don’t know for sure that antibodies are what protect people from getting infected,” he said. Although it’s a reasonable assumption, he said, that’s not always the case.

Another caveat is that even if antibodies do protect, the tests being used to measure them – including the test that was used in this study – may not measure them the right way, and it is not yet known how many antibodies are needed for protection, he explained.

The UCLA researchers used an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay to detect anti–SARS-CoV-2 spike receptor–binding domain immunoglobulin G concentrations.

“No reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically”

The study provides further proof that “[t]here’s no reason for anybody to be getting an antibody test medically right now,” Dr. Yang said.

Additionally, “FDA-approved tests are not approved for quantitative measures, only qualitative,” he continued. He noted that the findings may have implications with respect to herd immunity.

“Herd immunity depends on a lot of people having immunity to the infection all at the same time. If infection is followed by only brief protection from infection, the natural infection is not going to reach herd immunity,” he explained.

Buddy Creech, MD, MPH, associate professor of pediatrics and director of the Vanderbilt Vaccine Research Program in Nashville, Tenn., pointed out that antibodies “are just part of the story.”

“When we make an immune response to any germ,” he said, “we not only make an immune response for the time being but for the future. The next time we’re exposed, we can call into action B cells and T cells who have been there and done that.”

So even though the antibodies fade over time, other arms of the immune system are being trained for future action, he said.

Herd immunity does not require that populations have a huge level of antibodies that remains forever, he explained.

“It requires that in general, we’re not going to get infected as easily, and we’re not going to have disease as easily, and we’re not going to transmit the virus for as long,” he said.

Dr. Creech said he and others researching COVID-19 find that studies that show that antibodies fade quickly provide more proof “that this coronavirus is going to be here to stay unless we can take care of it through very effective treatments to take it from potentially fatal disease to one that is nothing more than a cold” or until a vaccine is developed.

He noted there are four other coronaviruses in widespread circulation every year that “amount to about 25% of the common cold.”

This study may help narrow the window as to when convalescent plasma – plasma that is taken from people who have recovered from COVID-19 and that is used to help people who are acutely ill with the disease – will be most effective, Dr. Creech explained. He said the results suggest that it is important that plasma be collected within the first couple of months after recovery so as to capture the most antibodies.

This study is important as another snapshot “so we understand the differences between severe and mild disease, so we can study it over time, so we have all the tools we need as we start these pivotal vaccine studies to make sure we’re making the right immune response for the right duration of time so we can put an end to this pandemic,” Dr. Creech concluded.

The study was supported by grants from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation, the Doris Duke Charitable Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, the James B. Pendleton Charitable Trust, and the McCarthy Family Foundation. A coauthor reports receiving grants from Gilead outside the submitted work. Dr. Creech has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Is the presence of enanthem a clue for COVID-19?

Larger studies should explore and confirm this association, the study’s authors and other experts suggested.

Dermatologists are already aware of the connection between enanthem and viral etiology. “As seen with other viral infections, we wondered if COVID-19 could produce enanthem in addition to skin rash exanthem,” one of the study author’s, Juan Jiménez-Cauhe, MD, a dermatologist with Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, said in an interview. He and his colleagues summarized their findings in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology.

They examined the oral cavity of 21 COVID-19 patients at a tertiary care hospital who also had a skin rash from March 30 to April 8. They classified enanthems into four categories: petechial, macular, macular with petechiae, or erythematovesicular. Six of the patients presented with oral lesions, all of them located in the palate; in one patient, the enanthem was macular, it was petechial in two patients and was macular with petechiae in three patients. The six patients ranged between the ages of 40 and 69 years; four were women.

Petechial or vesicular patterns are often associated with viral infections. In this particular study, the investigators did not observe vesicular lesions.

On average, mucocutaneous lesions appeared about 12 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. “Interestingly, this latency was shorter in patients with petechial enanthem, compared with those with a macular lesion with petechiae appearance,” the authors wrote.

This shorter time might suggest an association for SARS-CoV-2, said Dr. Jiménez-Cauhe. Strong cough may have also caused petechial lesions on the palate, but it’s unlikely, as they appeared close in time to COVID-19 symptoms. It’s also unlikely that any drugs caused the lesions, as drug rashes can take 2-3 weeks to appear.

This fits in line with other evidence of broader skin manifestations appearing at the same time or after COVID-19, Esther Freeman, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Freeman, director of global health dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, is the principal investigator of the COVID-19 Dermatology Registry, a collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology and International League of Dermatological Societies.

The study’s small cohort made it difficult to establish a solid association between the oral lesions and SARS-CoV-2. “However, the presence of enanthem in a patient with a skin rash is a useful finding that suggests a viral etiology rather than a drug reaction. This is particularly useful in COVID-19 patients, who were receiving many drugs as part of the treatment,” Dr. Jimenez-Cauhe said. Future studies should assess whether the presence of enanthem and exanthem lead physicians to consider SARS-CoV-2 as possible agents, ruling out infection with a blood or nasopharyngeal test.

This study adds to the growing body of knowledge on cutaneous and mucocutaneous findings associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Jules Lipoff, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “One challenge in evaluating these findings is that these findings are nonspecific, and medication reactions can often cause similar rashes, such as morbilliform eruptions that can be associated with both viruses and medications.”

Enanthems, as the study authors noted, are more specific to viral infections and are less commonly associated with medication reactions. “So, even though this is a small case series with significant limitations, it does add more evidence that COVID-19 is directly responsible for findings in the skin and mucous membranes,” said Dr. Lipoff.

Dr. Freeman noted that the study may also encourage clinicians to look in a patient’s mouth when assessing for SARS-CoV-2. Additional research should examine these data in a larger population.

Several studies by Dr. Freeman, Dr. Lipoff, and others strongly suggest that SARS-CoV-2 has a spectrum of associated dermatologic manifestations. One evaluated perniolike skin lesions (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug; 83[2]:486-92). The other was a case series from the COVID-19 registry that examined 716 cases of new-onset dermatologic symptoms in patients from 31 countries with confirmed/suspected SARS-CoV-2 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 2;S0190-9622[20]32126-5.).

The authors of the report had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2550.

Larger studies should explore and confirm this association, the study’s authors and other experts suggested.

Dermatologists are already aware of the connection between enanthem and viral etiology. “As seen with other viral infections, we wondered if COVID-19 could produce enanthem in addition to skin rash exanthem,” one of the study author’s, Juan Jiménez-Cauhe, MD, a dermatologist with Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, said in an interview. He and his colleagues summarized their findings in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology.

They examined the oral cavity of 21 COVID-19 patients at a tertiary care hospital who also had a skin rash from March 30 to April 8. They classified enanthems into four categories: petechial, macular, macular with petechiae, or erythematovesicular. Six of the patients presented with oral lesions, all of them located in the palate; in one patient, the enanthem was macular, it was petechial in two patients and was macular with petechiae in three patients. The six patients ranged between the ages of 40 and 69 years; four were women.

Petechial or vesicular patterns are often associated with viral infections. In this particular study, the investigators did not observe vesicular lesions.

On average, mucocutaneous lesions appeared about 12 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. “Interestingly, this latency was shorter in patients with petechial enanthem, compared with those with a macular lesion with petechiae appearance,” the authors wrote.

This shorter time might suggest an association for SARS-CoV-2, said Dr. Jiménez-Cauhe. Strong cough may have also caused petechial lesions on the palate, but it’s unlikely, as they appeared close in time to COVID-19 symptoms. It’s also unlikely that any drugs caused the lesions, as drug rashes can take 2-3 weeks to appear.

This fits in line with other evidence of broader skin manifestations appearing at the same time or after COVID-19, Esther Freeman, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Freeman, director of global health dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, is the principal investigator of the COVID-19 Dermatology Registry, a collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology and International League of Dermatological Societies.

The study’s small cohort made it difficult to establish a solid association between the oral lesions and SARS-CoV-2. “However, the presence of enanthem in a patient with a skin rash is a useful finding that suggests a viral etiology rather than a drug reaction. This is particularly useful in COVID-19 patients, who were receiving many drugs as part of the treatment,” Dr. Jimenez-Cauhe said. Future studies should assess whether the presence of enanthem and exanthem lead physicians to consider SARS-CoV-2 as possible agents, ruling out infection with a blood or nasopharyngeal test.

This study adds to the growing body of knowledge on cutaneous and mucocutaneous findings associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Jules Lipoff, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “One challenge in evaluating these findings is that these findings are nonspecific, and medication reactions can often cause similar rashes, such as morbilliform eruptions that can be associated with both viruses and medications.”

Enanthems, as the study authors noted, are more specific to viral infections and are less commonly associated with medication reactions. “So, even though this is a small case series with significant limitations, it does add more evidence that COVID-19 is directly responsible for findings in the skin and mucous membranes,” said Dr. Lipoff.

Dr. Freeman noted that the study may also encourage clinicians to look in a patient’s mouth when assessing for SARS-CoV-2. Additional research should examine these data in a larger population.

Several studies by Dr. Freeman, Dr. Lipoff, and others strongly suggest that SARS-CoV-2 has a spectrum of associated dermatologic manifestations. One evaluated perniolike skin lesions (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug; 83[2]:486-92). The other was a case series from the COVID-19 registry that examined 716 cases of new-onset dermatologic symptoms in patients from 31 countries with confirmed/suspected SARS-CoV-2 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 2;S0190-9622[20]32126-5.).

The authors of the report had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2550.

Larger studies should explore and confirm this association, the study’s authors and other experts suggested.

Dermatologists are already aware of the connection between enanthem and viral etiology. “As seen with other viral infections, we wondered if COVID-19 could produce enanthem in addition to skin rash exanthem,” one of the study author’s, Juan Jiménez-Cauhe, MD, a dermatologist with Hospital Universitario Ramon y Cajal, Madrid, said in an interview. He and his colleagues summarized their findings in a research letter in JAMA Dermatology.

They examined the oral cavity of 21 COVID-19 patients at a tertiary care hospital who also had a skin rash from March 30 to April 8. They classified enanthems into four categories: petechial, macular, macular with petechiae, or erythematovesicular. Six of the patients presented with oral lesions, all of them located in the palate; in one patient, the enanthem was macular, it was petechial in two patients and was macular with petechiae in three patients. The six patients ranged between the ages of 40 and 69 years; four were women.

Petechial or vesicular patterns are often associated with viral infections. In this particular study, the investigators did not observe vesicular lesions.

On average, mucocutaneous lesions appeared about 12 days after the onset of COVID-19 symptoms. “Interestingly, this latency was shorter in patients with petechial enanthem, compared with those with a macular lesion with petechiae appearance,” the authors wrote.

This shorter time might suggest an association for SARS-CoV-2, said Dr. Jiménez-Cauhe. Strong cough may have also caused petechial lesions on the palate, but it’s unlikely, as they appeared close in time to COVID-19 symptoms. It’s also unlikely that any drugs caused the lesions, as drug rashes can take 2-3 weeks to appear.

This fits in line with other evidence of broader skin manifestations appearing at the same time or after COVID-19, Esther Freeman, MD, said in an interview. Dr. Freeman, director of global health dermatology at Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, is the principal investigator of the COVID-19 Dermatology Registry, a collaboration of the American Academy of Dermatology and International League of Dermatological Societies.

The study’s small cohort made it difficult to establish a solid association between the oral lesions and SARS-CoV-2. “However, the presence of enanthem in a patient with a skin rash is a useful finding that suggests a viral etiology rather than a drug reaction. This is particularly useful in COVID-19 patients, who were receiving many drugs as part of the treatment,” Dr. Jimenez-Cauhe said. Future studies should assess whether the presence of enanthem and exanthem lead physicians to consider SARS-CoV-2 as possible agents, ruling out infection with a blood or nasopharyngeal test.

This study adds to the growing body of knowledge on cutaneous and mucocutaneous findings associated with SARS-CoV-2 infection, Jules Lipoff, MD, of the department of dermatology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, said in an interview. “One challenge in evaluating these findings is that these findings are nonspecific, and medication reactions can often cause similar rashes, such as morbilliform eruptions that can be associated with both viruses and medications.”

Enanthems, as the study authors noted, are more specific to viral infections and are less commonly associated with medication reactions. “So, even though this is a small case series with significant limitations, it does add more evidence that COVID-19 is directly responsible for findings in the skin and mucous membranes,” said Dr. Lipoff.

Dr. Freeman noted that the study may also encourage clinicians to look in a patient’s mouth when assessing for SARS-CoV-2. Additional research should examine these data in a larger population.

Several studies by Dr. Freeman, Dr. Lipoff, and others strongly suggest that SARS-CoV-2 has a spectrum of associated dermatologic manifestations. One evaluated perniolike skin lesions (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Aug; 83[2]:486-92). The other was a case series from the COVID-19 registry that examined 716 cases of new-onset dermatologic symptoms in patients from 31 countries with confirmed/suspected SARS-CoV-2 (J Am Acad Dermatol. 2020 Jul 2;S0190-9622[20]32126-5.).

The authors of the report had no disclosures.

SOURCE: Jimenez-Cauhe J et al. JAMA Dermatol. 2020 Jul 15. doi: 10.1001/jamadermatol.2020.2550.

FROM JAMA DERMATOLOGY

Internists’ use of ultrasound can reduce radiology referrals

researchers say.

“It’s a safe and very useful tool,” Marco Barchiesi, MD, an internal medicine resident at Luigi Sacco Hospital in Milan, said in an interview. “We had a great reduction in chest x-rays because of the use of ultrasound.”

The finding addresses concerns that ultrasound used in primary care could consume more health care resources or put patients at risk.

Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues published their findings July 20 in the European Journal of Internal Medicine.

Point-of-care ultrasound has become increasingly common as miniaturization of devices has made them more portable. The approach has caught on particularly in emergency departments where quick decisions are of the essence.

Its use in internal medicine has been more controversial, with concerns raised that improperly trained practitioners may miss diagnoses or refer patients for unnecessary tests as a result of uncertainty about their findings.

To measure the effect of point-of-care ultrasound in an internal medicine hospital ward, Dr. Barchiesi and colleagues alternated months when point-of-care ultrasound was allowed with months when it was not allowed, for a total of 4 months each, on an internal medicine unit. They allowed the ultrasound to be used for invasive procedures and excluded patients whose critical condition made point-of-care ultrasound crucial.

The researchers analyzed data on 263 patients in the “on” months when point-of-care ultrasound was used, and 255 in the “off” months when it wasn’t used. The two groups were well balanced in age, sex, comorbidity, and clinical impairment.

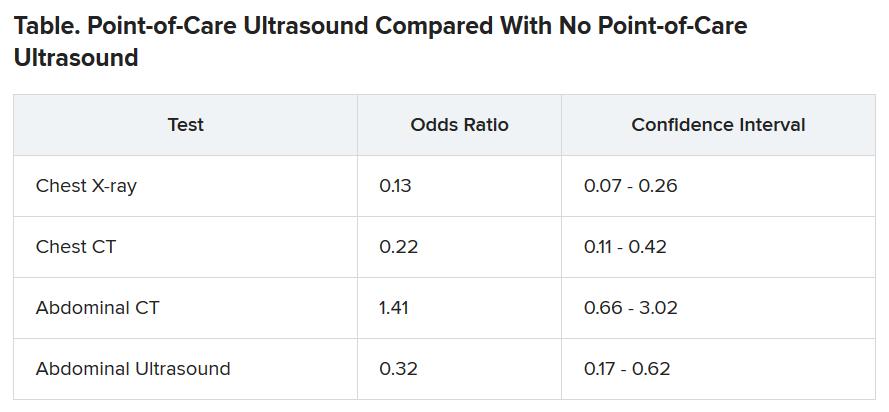

During the on months, the internists ordered 113 diagnostic tests (0.43 per patient). During the off months they ordered 329 tests (1.29 per patient).