User login

The Journal of Clinical Outcomes Management® is an independent, peer-reviewed journal offering evidence-based, practical information for improving the quality, safety, and value of health care.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

AASLD 2020: A clinical news roundup

Studies that address fundamental questions in hepatology and have the potential to change or improve clinical practice were the focus of a clinical debrief session from the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“We chose papers that had the highest level of evidence, such as randomized controlled trials, controlled studies, and large data sets – and some small data sets too,” said Tamar Taddei, MD, associate professor of medicine in the section of digestive disease at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Taddei and colleagues Silvia Vilarinho, MD, PhD; Simona Jakab, MD; and Ariel Jaffe, MD, all also from Yale, selected the papers from among 197 oral and 1,769 poster abstracts presented at AASLD 2020.

They highlighted the most important findings from presentations on autoimmune and cholestatic disease, transplantation, cirrhosis and portal hypertension, alcoholic liver disease, neoplasia, drug-induced liver injury, and COVID-19. They did not review studies focused primarily on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis, or basic science, all of which were covered in separate debriefing sessions.

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

A study from the Department of Veterans Affairs looked at the prevalence of liver disease risk factors and rates of subsequent testing for and diagnosis of cirrhosis in the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA).

The authors found that, among more than 6.65 million VHA users in 2018 with no prior diagnosis of cirrhosis, approximately half were at risk for cirrhosis, of whom about 75% were screened, and approximately 5% of those who were screened were positive for possible cirrhosis (133,636). Of the patients who screened positive, about 10% (12,566) received a diagnosis of cirrhosis, including 4,120 with liver decompensation.

“This paper underscores the importance of population-level screening in uncovering unrecognized cirrhosis, enabling intervention earlier in the course of disease,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #661).

A study looking at external validation of novel cirrhosis surgical risk models designed to improve prognostication for a range of common surgeries showed that the VOCAL-Penn score was superior to the Mayo Risk Score, Model for End-stage Liver Disease and MELD-sodium scores for discrimination of 30-day and 90-day postoperative mortality (Abstract #91).

“While these models are not a substitute for clinical acumen, they certainly improve our surgical risk prediction in patients with cirrhosis, a very common question in consultative hepatology,” Dr. Taddei said.

She also cited three abstracts that address the important questions regarding performing studies in patients with varices or ascites, including whether it’s safe to perform transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cirrhosis without first screening for varices, and whether nonselective beta-blockers should be continued in patients with refractory ascites.

A retrospective study of 191 patients with cirrhosis who underwent upper endoscopy within 4 years of transesophageal echocardiography had no overt gastrointestinal bleeding regardless of the presence of esophageal varices, suggesting that routine preprocedure esophagogastroduodenoscopy “is of no utility,” (Abstract #1872).

A study to determine risk of sepsis in 1,198 patients with cirrhosis found that 1-year risk of sepsis was reduced by 50% with the use of nonselective beta-blockers (Abstract #94).

The final abstract in this category touched on the use of an advance care planning video support tool to help transplant-ineligible patients with end-stage liver disease decide whether they want support measures such cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation. The authors found that the video decision tool was feasible and acceptable to patients, and improved their knowledge of end-of-life care. More patients randomized to the video arm opted against CPR or intubation, compared with those assigned to a verbal discussion of options (Abstract #712).

Alcohol

The reviewers highlighted two studies of alcohol use: The first was designed to determine the prevalence of early alcohol relapse (resumption within 3 months) in patients who presented with alcoholic hepatitis. The subjects included 478 patients enrolled in the STOPAH trial, and a validation set of 194 patients from the InTeam (Integrated Approaches for identifying Molecular Targets in Alcoholic Hepatitis) Consortium.

“They found that high-risk patients were younger, unemployed, and without a stable relationship. Intermediate risk were middle aged, employed, and in a stable relationship, and low-risk profiles were older, with known cirrhosis; they were mostly retired and in a stable relationship,” Dr. Taddei said.

The identification of nongenetic factors that predict early relapse may aid in personalization of treatment strategies, she said (Abstract #232).

The second study looked at fecal microbial transplant (FMT) for reducing cravings in adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and cirrhosis. The investigators saw a nonsignificant trend toward greater total abstinence at 6 months in patients randomized to FMT versus placebo.

“Future trials should be performed to determine the impact of FMT on altering the gut-brain axis in patients with AUD,” she said (Abstract #7).

Transplantation

The prospective controlled QUICKTRANS study by French and Belgian researchers found that patients who underwent early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis had numerically but not significantly higher rates of relapse than patients who were transplanted after at least 6 months of abstinence, although heavy drinking was more frequent in patients who underwent early transplant.

The 2-year survival rates for both patients who underwent early transplant and those who underwent transplant after 6 months of sobriety were “identical, and excellent.” In addition, the 2-year survival rate for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis who underwent transplant was 82.8%, compared with 28.2% for patients who were deemed ineligible for transplant according to a selection algorithm (P < .001).

“Perhaps most important is that studies in this population can be conducted in a controlled fashion across centers with reproducible transplant eligibility algorithms,” Dr. Taddei commented (Abstract #6).

The place of honor – Abstract # 1 – was reserved for a study looking at the effects on liver transplant practice of a new “safety net” policy from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United Network for Organ Sharing stating that patients awaiting liver transplantation who develop kidney failure may be given priority on the kidney transplant waiting list.

The investigators found that the new policy significantly increased the number of adult primary liver transplant alone candidates who where on dialysis at the time of listing, and did not affect either waiting list mortality or posttransplant outcomes.

The authors also saw a significant increase in kidney transplant listing after liver transplant, especially for patients who were on hemodialysis at the time of list.

In the period after implementation of the policy, there was a significantly higher probability of kidney transplant, and significant reduction in waiting list mortality.

Autoimmune & cholestatic diseases

Investigators performed an analysis of the phase 3 randomized controlled ENHANCE trial of seladelpar in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. The trial was stopped because of an adverse event ultimately deemed to be unrelated to the drug, so the analysis looked at the composite responder rate at month 3.

“The key takeaway from this study is that at the 10-mg dosage of seladelpar, 78% met a composite endpoint, 27% of patients normalized their alkaline phosphatase, and 50% normalized their ALT. There was significant improvement in pruritus,” Dr. Taddei said.

The drug was generally safe and well tolerated. A 52-week phase 3 global registration study will begin enrolling patients in early 2021 (Abstract #LO11).

In a pediatric study, investigators looked at differences in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) among various population, and found that “Black and Hispanic patients have dramatically worse clinical outcomes, compared to White and Asian patients. They are more likely to be diagnosed with PSC at an advanced stage with extensive fibrosis and portal hypertensive manifestations.”

The authors suggested that the differences may be explained in part by socioeconomic disparities leading to delay in diagnosis, to a more aggressive phenotype, or both (Abstract #66).

A meta-analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes in women with autoimmune hepatitis showed that the disease is associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes, premature births, and small-for-gestational age or low-birth-weight babies.

“Pregnant women should be monitored closely before, during and after pregnancy. It’s important to know that, in the prevalence data, flares were most prevalent postpartum at 41%. These finds will help us counsel our patients with autoimmune hepatitis who become pregnant,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #97).

Drug-induced liver injury

A study of clinical outcomes following immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in melanoma patients with resolved higher grade 3 or higher checkpoint inhibitor–induced hepatitis showed that 4 of 31 patients (13%) developed recurrence of grade 2 or greater hepatitis, and 15 of 31 (48%) developed an immune-related adverse event after rechallenge.

There was no difference in time to death between patients who were rechallenged and those who were not, and immune-related liver toxicities requiring drug discontinuation after rechallenge were uncommon.

“High-grade immune checkpoint inhibitor hepatitis should be reconsidered as an absolute contraindication for immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract # 116).

Neoplasia

The investigators also highlighted an abstract describing significant urban-rural and racial ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma rates. A fuller description of this study can be found here (Abstract #136).

COVID-19

Finally, the reviewer highlighted a study of the clinical course of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease, and to determine factors associated with adverse outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease who acquire COVID-19.

The investigators found that patients with chronic liver disease and COVID-19 have a 14% morality rate, and that alcohol-related liver disease, decompensated cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma are all risk factors for increased mortality from COVID-19.

They recommended emphasizing telemedicine, prioritizing patients with chronic liver disease for vaccination, and including these patients in prospective studies and drug trials for COVID-19 therapies.

Dr. Taddei reported having no disclosures.

Studies that address fundamental questions in hepatology and have the potential to change or improve clinical practice were the focus of a clinical debrief session from the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“We chose papers that had the highest level of evidence, such as randomized controlled trials, controlled studies, and large data sets – and some small data sets too,” said Tamar Taddei, MD, associate professor of medicine in the section of digestive disease at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Taddei and colleagues Silvia Vilarinho, MD, PhD; Simona Jakab, MD; and Ariel Jaffe, MD, all also from Yale, selected the papers from among 197 oral and 1,769 poster abstracts presented at AASLD 2020.

They highlighted the most important findings from presentations on autoimmune and cholestatic disease, transplantation, cirrhosis and portal hypertension, alcoholic liver disease, neoplasia, drug-induced liver injury, and COVID-19. They did not review studies focused primarily on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis, or basic science, all of which were covered in separate debriefing sessions.

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

A study from the Department of Veterans Affairs looked at the prevalence of liver disease risk factors and rates of subsequent testing for and diagnosis of cirrhosis in the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA).

The authors found that, among more than 6.65 million VHA users in 2018 with no prior diagnosis of cirrhosis, approximately half were at risk for cirrhosis, of whom about 75% were screened, and approximately 5% of those who were screened were positive for possible cirrhosis (133,636). Of the patients who screened positive, about 10% (12,566) received a diagnosis of cirrhosis, including 4,120 with liver decompensation.

“This paper underscores the importance of population-level screening in uncovering unrecognized cirrhosis, enabling intervention earlier in the course of disease,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #661).

A study looking at external validation of novel cirrhosis surgical risk models designed to improve prognostication for a range of common surgeries showed that the VOCAL-Penn score was superior to the Mayo Risk Score, Model for End-stage Liver Disease and MELD-sodium scores for discrimination of 30-day and 90-day postoperative mortality (Abstract #91).

“While these models are not a substitute for clinical acumen, they certainly improve our surgical risk prediction in patients with cirrhosis, a very common question in consultative hepatology,” Dr. Taddei said.

She also cited three abstracts that address the important questions regarding performing studies in patients with varices or ascites, including whether it’s safe to perform transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cirrhosis without first screening for varices, and whether nonselective beta-blockers should be continued in patients with refractory ascites.

A retrospective study of 191 patients with cirrhosis who underwent upper endoscopy within 4 years of transesophageal echocardiography had no overt gastrointestinal bleeding regardless of the presence of esophageal varices, suggesting that routine preprocedure esophagogastroduodenoscopy “is of no utility,” (Abstract #1872).

A study to determine risk of sepsis in 1,198 patients with cirrhosis found that 1-year risk of sepsis was reduced by 50% with the use of nonselective beta-blockers (Abstract #94).

The final abstract in this category touched on the use of an advance care planning video support tool to help transplant-ineligible patients with end-stage liver disease decide whether they want support measures such cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation. The authors found that the video decision tool was feasible and acceptable to patients, and improved their knowledge of end-of-life care. More patients randomized to the video arm opted against CPR or intubation, compared with those assigned to a verbal discussion of options (Abstract #712).

Alcohol

The reviewers highlighted two studies of alcohol use: The first was designed to determine the prevalence of early alcohol relapse (resumption within 3 months) in patients who presented with alcoholic hepatitis. The subjects included 478 patients enrolled in the STOPAH trial, and a validation set of 194 patients from the InTeam (Integrated Approaches for identifying Molecular Targets in Alcoholic Hepatitis) Consortium.

“They found that high-risk patients were younger, unemployed, and without a stable relationship. Intermediate risk were middle aged, employed, and in a stable relationship, and low-risk profiles were older, with known cirrhosis; they were mostly retired and in a stable relationship,” Dr. Taddei said.

The identification of nongenetic factors that predict early relapse may aid in personalization of treatment strategies, she said (Abstract #232).

The second study looked at fecal microbial transplant (FMT) for reducing cravings in adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and cirrhosis. The investigators saw a nonsignificant trend toward greater total abstinence at 6 months in patients randomized to FMT versus placebo.

“Future trials should be performed to determine the impact of FMT on altering the gut-brain axis in patients with AUD,” she said (Abstract #7).

Transplantation

The prospective controlled QUICKTRANS study by French and Belgian researchers found that patients who underwent early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis had numerically but not significantly higher rates of relapse than patients who were transplanted after at least 6 months of abstinence, although heavy drinking was more frequent in patients who underwent early transplant.

The 2-year survival rates for both patients who underwent early transplant and those who underwent transplant after 6 months of sobriety were “identical, and excellent.” In addition, the 2-year survival rate for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis who underwent transplant was 82.8%, compared with 28.2% for patients who were deemed ineligible for transplant according to a selection algorithm (P < .001).

“Perhaps most important is that studies in this population can be conducted in a controlled fashion across centers with reproducible transplant eligibility algorithms,” Dr. Taddei commented (Abstract #6).

The place of honor – Abstract # 1 – was reserved for a study looking at the effects on liver transplant practice of a new “safety net” policy from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United Network for Organ Sharing stating that patients awaiting liver transplantation who develop kidney failure may be given priority on the kidney transplant waiting list.

The investigators found that the new policy significantly increased the number of adult primary liver transplant alone candidates who where on dialysis at the time of listing, and did not affect either waiting list mortality or posttransplant outcomes.

The authors also saw a significant increase in kidney transplant listing after liver transplant, especially for patients who were on hemodialysis at the time of list.

In the period after implementation of the policy, there was a significantly higher probability of kidney transplant, and significant reduction in waiting list mortality.

Autoimmune & cholestatic diseases

Investigators performed an analysis of the phase 3 randomized controlled ENHANCE trial of seladelpar in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. The trial was stopped because of an adverse event ultimately deemed to be unrelated to the drug, so the analysis looked at the composite responder rate at month 3.

“The key takeaway from this study is that at the 10-mg dosage of seladelpar, 78% met a composite endpoint, 27% of patients normalized their alkaline phosphatase, and 50% normalized their ALT. There was significant improvement in pruritus,” Dr. Taddei said.

The drug was generally safe and well tolerated. A 52-week phase 3 global registration study will begin enrolling patients in early 2021 (Abstract #LO11).

In a pediatric study, investigators looked at differences in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) among various population, and found that “Black and Hispanic patients have dramatically worse clinical outcomes, compared to White and Asian patients. They are more likely to be diagnosed with PSC at an advanced stage with extensive fibrosis and portal hypertensive manifestations.”

The authors suggested that the differences may be explained in part by socioeconomic disparities leading to delay in diagnosis, to a more aggressive phenotype, or both (Abstract #66).

A meta-analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes in women with autoimmune hepatitis showed that the disease is associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes, premature births, and small-for-gestational age or low-birth-weight babies.

“Pregnant women should be monitored closely before, during and after pregnancy. It’s important to know that, in the prevalence data, flares were most prevalent postpartum at 41%. These finds will help us counsel our patients with autoimmune hepatitis who become pregnant,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #97).

Drug-induced liver injury

A study of clinical outcomes following immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in melanoma patients with resolved higher grade 3 or higher checkpoint inhibitor–induced hepatitis showed that 4 of 31 patients (13%) developed recurrence of grade 2 or greater hepatitis, and 15 of 31 (48%) developed an immune-related adverse event after rechallenge.

There was no difference in time to death between patients who were rechallenged and those who were not, and immune-related liver toxicities requiring drug discontinuation after rechallenge were uncommon.

“High-grade immune checkpoint inhibitor hepatitis should be reconsidered as an absolute contraindication for immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract # 116).

Neoplasia

The investigators also highlighted an abstract describing significant urban-rural and racial ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma rates. A fuller description of this study can be found here (Abstract #136).

COVID-19

Finally, the reviewer highlighted a study of the clinical course of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease, and to determine factors associated with adverse outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease who acquire COVID-19.

The investigators found that patients with chronic liver disease and COVID-19 have a 14% morality rate, and that alcohol-related liver disease, decompensated cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma are all risk factors for increased mortality from COVID-19.

They recommended emphasizing telemedicine, prioritizing patients with chronic liver disease for vaccination, and including these patients in prospective studies and drug trials for COVID-19 therapies.

Dr. Taddei reported having no disclosures.

Studies that address fundamental questions in hepatology and have the potential to change or improve clinical practice were the focus of a clinical debrief session from the virtual annual meeting of the American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases.

“We chose papers that had the highest level of evidence, such as randomized controlled trials, controlled studies, and large data sets – and some small data sets too,” said Tamar Taddei, MD, associate professor of medicine in the section of digestive disease at Yale University, New Haven, Conn.

Dr. Taddei and colleagues Silvia Vilarinho, MD, PhD; Simona Jakab, MD; and Ariel Jaffe, MD, all also from Yale, selected the papers from among 197 oral and 1,769 poster abstracts presented at AASLD 2020.

They highlighted the most important findings from presentations on autoimmune and cholestatic disease, transplantation, cirrhosis and portal hypertension, alcoholic liver disease, neoplasia, drug-induced liver injury, and COVID-19. They did not review studies focused primarily on nonalcoholic steatohepatitis or nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, viral hepatitis, or basic science, all of which were covered in separate debriefing sessions.

Cirrhosis and portal hypertension

A study from the Department of Veterans Affairs looked at the prevalence of liver disease risk factors and rates of subsequent testing for and diagnosis of cirrhosis in the Veterans Health Administration system (VHA).

The authors found that, among more than 6.65 million VHA users in 2018 with no prior diagnosis of cirrhosis, approximately half were at risk for cirrhosis, of whom about 75% were screened, and approximately 5% of those who were screened were positive for possible cirrhosis (133,636). Of the patients who screened positive, about 10% (12,566) received a diagnosis of cirrhosis, including 4,120 with liver decompensation.

“This paper underscores the importance of population-level screening in uncovering unrecognized cirrhosis, enabling intervention earlier in the course of disease,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #661).

A study looking at external validation of novel cirrhosis surgical risk models designed to improve prognostication for a range of common surgeries showed that the VOCAL-Penn score was superior to the Mayo Risk Score, Model for End-stage Liver Disease and MELD-sodium scores for discrimination of 30-day and 90-day postoperative mortality (Abstract #91).

“While these models are not a substitute for clinical acumen, they certainly improve our surgical risk prediction in patients with cirrhosis, a very common question in consultative hepatology,” Dr. Taddei said.

She also cited three abstracts that address the important questions regarding performing studies in patients with varices or ascites, including whether it’s safe to perform transesophageal echocardiography in patients with cirrhosis without first screening for varices, and whether nonselective beta-blockers should be continued in patients with refractory ascites.

A retrospective study of 191 patients with cirrhosis who underwent upper endoscopy within 4 years of transesophageal echocardiography had no overt gastrointestinal bleeding regardless of the presence of esophageal varices, suggesting that routine preprocedure esophagogastroduodenoscopy “is of no utility,” (Abstract #1872).

A study to determine risk of sepsis in 1,198 patients with cirrhosis found that 1-year risk of sepsis was reduced by 50% with the use of nonselective beta-blockers (Abstract #94).

The final abstract in this category touched on the use of an advance care planning video support tool to help transplant-ineligible patients with end-stage liver disease decide whether they want support measures such cardiopulmonary resuscitation or intubation. The authors found that the video decision tool was feasible and acceptable to patients, and improved their knowledge of end-of-life care. More patients randomized to the video arm opted against CPR or intubation, compared with those assigned to a verbal discussion of options (Abstract #712).

Alcohol

The reviewers highlighted two studies of alcohol use: The first was designed to determine the prevalence of early alcohol relapse (resumption within 3 months) in patients who presented with alcoholic hepatitis. The subjects included 478 patients enrolled in the STOPAH trial, and a validation set of 194 patients from the InTeam (Integrated Approaches for identifying Molecular Targets in Alcoholic Hepatitis) Consortium.

“They found that high-risk patients were younger, unemployed, and without a stable relationship. Intermediate risk were middle aged, employed, and in a stable relationship, and low-risk profiles were older, with known cirrhosis; they were mostly retired and in a stable relationship,” Dr. Taddei said.

The identification of nongenetic factors that predict early relapse may aid in personalization of treatment strategies, she said (Abstract #232).

The second study looked at fecal microbial transplant (FMT) for reducing cravings in adults with alcohol use disorder (AUD) and cirrhosis. The investigators saw a nonsignificant trend toward greater total abstinence at 6 months in patients randomized to FMT versus placebo.

“Future trials should be performed to determine the impact of FMT on altering the gut-brain axis in patients with AUD,” she said (Abstract #7).

Transplantation

The prospective controlled QUICKTRANS study by French and Belgian researchers found that patients who underwent early liver transplantation for severe alcoholic hepatitis had numerically but not significantly higher rates of relapse than patients who were transplanted after at least 6 months of abstinence, although heavy drinking was more frequent in patients who underwent early transplant.

The 2-year survival rates for both patients who underwent early transplant and those who underwent transplant after 6 months of sobriety were “identical, and excellent.” In addition, the 2-year survival rate for patients with severe alcoholic hepatitis who underwent transplant was 82.8%, compared with 28.2% for patients who were deemed ineligible for transplant according to a selection algorithm (P < .001).

“Perhaps most important is that studies in this population can be conducted in a controlled fashion across centers with reproducible transplant eligibility algorithms,” Dr. Taddei commented (Abstract #6).

The place of honor – Abstract # 1 – was reserved for a study looking at the effects on liver transplant practice of a new “safety net” policy from the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network and United Network for Organ Sharing stating that patients awaiting liver transplantation who develop kidney failure may be given priority on the kidney transplant waiting list.

The investigators found that the new policy significantly increased the number of adult primary liver transplant alone candidates who where on dialysis at the time of listing, and did not affect either waiting list mortality or posttransplant outcomes.

The authors also saw a significant increase in kidney transplant listing after liver transplant, especially for patients who were on hemodialysis at the time of list.

In the period after implementation of the policy, there was a significantly higher probability of kidney transplant, and significant reduction in waiting list mortality.

Autoimmune & cholestatic diseases

Investigators performed an analysis of the phase 3 randomized controlled ENHANCE trial of seladelpar in patients with primary biliary cholangitis. The trial was stopped because of an adverse event ultimately deemed to be unrelated to the drug, so the analysis looked at the composite responder rate at month 3.

“The key takeaway from this study is that at the 10-mg dosage of seladelpar, 78% met a composite endpoint, 27% of patients normalized their alkaline phosphatase, and 50% normalized their ALT. There was significant improvement in pruritus,” Dr. Taddei said.

The drug was generally safe and well tolerated. A 52-week phase 3 global registration study will begin enrolling patients in early 2021 (Abstract #LO11).

In a pediatric study, investigators looked at differences in primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC) among various population, and found that “Black and Hispanic patients have dramatically worse clinical outcomes, compared to White and Asian patients. They are more likely to be diagnosed with PSC at an advanced stage with extensive fibrosis and portal hypertensive manifestations.”

The authors suggested that the differences may be explained in part by socioeconomic disparities leading to delay in diagnosis, to a more aggressive phenotype, or both (Abstract #66).

A meta-analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes in women with autoimmune hepatitis showed that the disease is associated with increased risk of gestational diabetes, premature births, and small-for-gestational age or low-birth-weight babies.

“Pregnant women should be monitored closely before, during and after pregnancy. It’s important to know that, in the prevalence data, flares were most prevalent postpartum at 41%. These finds will help us counsel our patients with autoimmune hepatitis who become pregnant,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract #97).

Drug-induced liver injury

A study of clinical outcomes following immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge in melanoma patients with resolved higher grade 3 or higher checkpoint inhibitor–induced hepatitis showed that 4 of 31 patients (13%) developed recurrence of grade 2 or greater hepatitis, and 15 of 31 (48%) developed an immune-related adverse event after rechallenge.

There was no difference in time to death between patients who were rechallenged and those who were not, and immune-related liver toxicities requiring drug discontinuation after rechallenge were uncommon.

“High-grade immune checkpoint inhibitor hepatitis should be reconsidered as an absolute contraindication for immune checkpoint inhibitor rechallenge,” Dr. Taddei said (Abstract # 116).

Neoplasia

The investigators also highlighted an abstract describing significant urban-rural and racial ethnic differences in hepatocellular carcinoma rates. A fuller description of this study can be found here (Abstract #136).

COVID-19

Finally, the reviewer highlighted a study of the clinical course of COVID-19 in patients with chronic liver disease, and to determine factors associated with adverse outcomes in patients with chronic liver disease who acquire COVID-19.

The investigators found that patients with chronic liver disease and COVID-19 have a 14% morality rate, and that alcohol-related liver disease, decompensated cirrhosis, and hepatocellular carcinoma are all risk factors for increased mortality from COVID-19.

They recommended emphasizing telemedicine, prioritizing patients with chronic liver disease for vaccination, and including these patients in prospective studies and drug trials for COVID-19 therapies.

Dr. Taddei reported having no disclosures.

FROM THE LIVER MEETING DIGITAL EXPERIENCE

A closer look at migraine aura

Migraine aura sometimes accompanies or precedes migraine pain, but the phenomenon is difficult to treat and poorly understood. However, some evidence points to potential neurological mechanisms, and migraine aura is associated with cardiovascular disease risk.

Andrea Harriott, MD, PhD, said at the Stowe Headache Symposium sponsored by the Headache Cooperative of New England, which was conducted virtually. Dr. Harriott is assistant professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Somewhere between 20% and 40% of patients with migraine experience aura. It is most often visual, though it can also include sensory, aphasic, and motor symptoms. Visual aura usually begins as a flickering zigzag pattern in the central visual field that moves slowly toward the periphery and often leaves a scotoma. Typical duration is 15-30 minutes. Aura symptoms are more common in females.

Research in the 1940s conducted by the Brazilian researcher Aristides de Azevedo Pacheco Leão, PhD, then at Harvard Medical School, Boston, showed evidence of CSD in rabbits after electrical or mechanical stimulation. He observed a wave of vasodilation and increased blood flow over the cortex that spread over nearly the entire dorsolateral cortex within 3-6 minutes.

In the 1940s and 1950s, researchers sketched on paper the visual disturbance over 10 minutes, tracking the expanding spectrum across the visual field, from the center toward the periphery. The resulting scotoma advanced across the visual cortex at a rate very similar to that of the cortical spreading observed by Dr. Leão, “potentially linking this electrical event that was described with the aura event of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott. Those researchers hypothesized that the aura was produced by a strong excitation phase, followed by a wave of total inhibition.

More recent functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have also shown that CSD-like disturbances occur when patients experience migraine aura. In one study, researchers observed an initial increase and then a decrease in the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal, which spread slowly across the visual cortex and correlated with the aura event. “This study was really important in confirming that a CSD-like phenomenon was likely the underlying perturbation that produced the visual aura of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott.

Despite the evidence that CSD causes migraine aura, its connection to migraine pain hasn’t been firmly established. But Dr. Harriott presented some evidence linking the two. Migraine aura is usually followed by pain, and aura precedes migraine attacks 78%-93% of the time. Cephalic allodynia occurs in migraine about 70% to 80% of the time, and migraine with aura is more often associated with severe cutaneous allodynia than is migraine without aura. Finally, migraine patients with comorbidities have more severe disability, and more frequent cutaneous allodynia and aura than does the general migraine population (40% vs. 29%).

All of that suggests that activation of trigeminal nociceptors is involved with migraine aura, according to Dr. Harriott. Preclinical studies have also suggested links between CSD and activation of trigeminal nociceptors, with both immunohistochemical and electrophysiological lines of evidence. “These data suggest that spreading depression actually activates trigeminal nociceptors that we know are involved in signal pain in the head and neck, and that we know are involved in cephalic allodynia as well,” Dr. Harriott said.

The evidence impressed Allan Purdy, MD, professor of medicine at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., who was the discussant for the presentation. “It’s an excellent case that CSD is a remarkably good correlate for aura,” he said during the session.

Along with potential impacts on migraine pain, aura is also associated with cardiovascular risk. “This is really important to know about in our clinical population,” said Dr. Harriott.

Meta-analyses of case control and cohort studies have shown associations between migraine aura and vascular disorders such as ischemic stroke. One meta-analysis showed about a twofold increased risk associated with migraine compared with the nonmigraine population. This difference was driven by migraine with aura (relative risk [RR], 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53-3.33) rather than migraine without aura (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.86-1.79). Migraine generally is associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08-1.64), and that association may be stronger in the aura phenotype.

There doesn’t appear to be evidence that traditional risk factors for heart disease – such as hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol – play a role in the association between aura and heart disease. One possibility is that variables like platelet activation, hypercoagulable state, or genetic susceptibility could be responsible.

The risks associated with migraine aura should be noted, but with a caveat, according to Dr. Purdy. “Even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is still relatively low, and patients with migraine with aura, who smoke or are female and over 45, those are the cases where the worry comes in.”

Dr. Harriott and Dr. Purdy have nothing to disclose.

Migraine aura sometimes accompanies or precedes migraine pain, but the phenomenon is difficult to treat and poorly understood. However, some evidence points to potential neurological mechanisms, and migraine aura is associated with cardiovascular disease risk.

Andrea Harriott, MD, PhD, said at the Stowe Headache Symposium sponsored by the Headache Cooperative of New England, which was conducted virtually. Dr. Harriott is assistant professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Somewhere between 20% and 40% of patients with migraine experience aura. It is most often visual, though it can also include sensory, aphasic, and motor symptoms. Visual aura usually begins as a flickering zigzag pattern in the central visual field that moves slowly toward the periphery and often leaves a scotoma. Typical duration is 15-30 minutes. Aura symptoms are more common in females.

Research in the 1940s conducted by the Brazilian researcher Aristides de Azevedo Pacheco Leão, PhD, then at Harvard Medical School, Boston, showed evidence of CSD in rabbits after electrical or mechanical stimulation. He observed a wave of vasodilation and increased blood flow over the cortex that spread over nearly the entire dorsolateral cortex within 3-6 minutes.

In the 1940s and 1950s, researchers sketched on paper the visual disturbance over 10 minutes, tracking the expanding spectrum across the visual field, from the center toward the periphery. The resulting scotoma advanced across the visual cortex at a rate very similar to that of the cortical spreading observed by Dr. Leão, “potentially linking this electrical event that was described with the aura event of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott. Those researchers hypothesized that the aura was produced by a strong excitation phase, followed by a wave of total inhibition.

More recent functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have also shown that CSD-like disturbances occur when patients experience migraine aura. In one study, researchers observed an initial increase and then a decrease in the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal, which spread slowly across the visual cortex and correlated with the aura event. “This study was really important in confirming that a CSD-like phenomenon was likely the underlying perturbation that produced the visual aura of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott.

Despite the evidence that CSD causes migraine aura, its connection to migraine pain hasn’t been firmly established. But Dr. Harriott presented some evidence linking the two. Migraine aura is usually followed by pain, and aura precedes migraine attacks 78%-93% of the time. Cephalic allodynia occurs in migraine about 70% to 80% of the time, and migraine with aura is more often associated with severe cutaneous allodynia than is migraine without aura. Finally, migraine patients with comorbidities have more severe disability, and more frequent cutaneous allodynia and aura than does the general migraine population (40% vs. 29%).

All of that suggests that activation of trigeminal nociceptors is involved with migraine aura, according to Dr. Harriott. Preclinical studies have also suggested links between CSD and activation of trigeminal nociceptors, with both immunohistochemical and electrophysiological lines of evidence. “These data suggest that spreading depression actually activates trigeminal nociceptors that we know are involved in signal pain in the head and neck, and that we know are involved in cephalic allodynia as well,” Dr. Harriott said.

The evidence impressed Allan Purdy, MD, professor of medicine at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., who was the discussant for the presentation. “It’s an excellent case that CSD is a remarkably good correlate for aura,” he said during the session.

Along with potential impacts on migraine pain, aura is also associated with cardiovascular risk. “This is really important to know about in our clinical population,” said Dr. Harriott.

Meta-analyses of case control and cohort studies have shown associations between migraine aura and vascular disorders such as ischemic stroke. One meta-analysis showed about a twofold increased risk associated with migraine compared with the nonmigraine population. This difference was driven by migraine with aura (relative risk [RR], 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53-3.33) rather than migraine without aura (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.86-1.79). Migraine generally is associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08-1.64), and that association may be stronger in the aura phenotype.

There doesn’t appear to be evidence that traditional risk factors for heart disease – such as hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol – play a role in the association between aura and heart disease. One possibility is that variables like platelet activation, hypercoagulable state, or genetic susceptibility could be responsible.

The risks associated with migraine aura should be noted, but with a caveat, according to Dr. Purdy. “Even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is still relatively low, and patients with migraine with aura, who smoke or are female and over 45, those are the cases where the worry comes in.”

Dr. Harriott and Dr. Purdy have nothing to disclose.

Migraine aura sometimes accompanies or precedes migraine pain, but the phenomenon is difficult to treat and poorly understood. However, some evidence points to potential neurological mechanisms, and migraine aura is associated with cardiovascular disease risk.

Andrea Harriott, MD, PhD, said at the Stowe Headache Symposium sponsored by the Headache Cooperative of New England, which was conducted virtually. Dr. Harriott is assistant professor of neurology at Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston.

Somewhere between 20% and 40% of patients with migraine experience aura. It is most often visual, though it can also include sensory, aphasic, and motor symptoms. Visual aura usually begins as a flickering zigzag pattern in the central visual field that moves slowly toward the periphery and often leaves a scotoma. Typical duration is 15-30 minutes. Aura symptoms are more common in females.

Research in the 1940s conducted by the Brazilian researcher Aristides de Azevedo Pacheco Leão, PhD, then at Harvard Medical School, Boston, showed evidence of CSD in rabbits after electrical or mechanical stimulation. He observed a wave of vasodilation and increased blood flow over the cortex that spread over nearly the entire dorsolateral cortex within 3-6 minutes.

In the 1940s and 1950s, researchers sketched on paper the visual disturbance over 10 minutes, tracking the expanding spectrum across the visual field, from the center toward the periphery. The resulting scotoma advanced across the visual cortex at a rate very similar to that of the cortical spreading observed by Dr. Leão, “potentially linking this electrical event that was described with the aura event of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott. Those researchers hypothesized that the aura was produced by a strong excitation phase, followed by a wave of total inhibition.

More recent functional magnetic resonance imaging studies have also shown that CSD-like disturbances occur when patients experience migraine aura. In one study, researchers observed an initial increase and then a decrease in the blood oxygenation level dependent (BOLD) signal, which spread slowly across the visual cortex and correlated with the aura event. “This study was really important in confirming that a CSD-like phenomenon was likely the underlying perturbation that produced the visual aura of migraine,” said Dr. Harriott.

Despite the evidence that CSD causes migraine aura, its connection to migraine pain hasn’t been firmly established. But Dr. Harriott presented some evidence linking the two. Migraine aura is usually followed by pain, and aura precedes migraine attacks 78%-93% of the time. Cephalic allodynia occurs in migraine about 70% to 80% of the time, and migraine with aura is more often associated with severe cutaneous allodynia than is migraine without aura. Finally, migraine patients with comorbidities have more severe disability, and more frequent cutaneous allodynia and aura than does the general migraine population (40% vs. 29%).

All of that suggests that activation of trigeminal nociceptors is involved with migraine aura, according to Dr. Harriott. Preclinical studies have also suggested links between CSD and activation of trigeminal nociceptors, with both immunohistochemical and electrophysiological lines of evidence. “These data suggest that spreading depression actually activates trigeminal nociceptors that we know are involved in signal pain in the head and neck, and that we know are involved in cephalic allodynia as well,” Dr. Harriott said.

The evidence impressed Allan Purdy, MD, professor of medicine at Dalhousie University, Halifax, N.S., who was the discussant for the presentation. “It’s an excellent case that CSD is a remarkably good correlate for aura,” he said during the session.

Along with potential impacts on migraine pain, aura is also associated with cardiovascular risk. “This is really important to know about in our clinical population,” said Dr. Harriott.

Meta-analyses of case control and cohort studies have shown associations between migraine aura and vascular disorders such as ischemic stroke. One meta-analysis showed about a twofold increased risk associated with migraine compared with the nonmigraine population. This difference was driven by migraine with aura (relative risk [RR], 2.25; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.53-3.33) rather than migraine without aura (RR, 1.24; 95% CI, 0.86-1.79). Migraine generally is associated with greater risk of myocardial infarction (adjusted hazard ratio, 1.33; 95% CI, 1.08-1.64), and that association may be stronger in the aura phenotype.

There doesn’t appear to be evidence that traditional risk factors for heart disease – such as hypertension, diabetes, or high cholesterol – play a role in the association between aura and heart disease. One possibility is that variables like platelet activation, hypercoagulable state, or genetic susceptibility could be responsible.

The risks associated with migraine aura should be noted, but with a caveat, according to Dr. Purdy. “Even though the relative risk is high, the absolute risk is still relatively low, and patients with migraine with aura, who smoke or are female and over 45, those are the cases where the worry comes in.”

Dr. Harriott and Dr. Purdy have nothing to disclose.

FROM HCNE STOWE 2020

FDA expands Xofluza indication to include postexposure flu prophylaxis

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the antiviral baloxavir marboxil (Xofluza) to include postexposure prophylaxis of uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years and older.

“This expanded indication for Xofluza will provide an important option to help prevent influenza just in time for a flu season that is anticipated to be unlike any other because it will coincide with the coronavirus pandemic,” Debra Birnkrant, MD, director, Division of Antiviral Products, FDA Center for Drug Evaluation and Research, said in a press release.

In addition, Xofluza, which was previously available only in tablet form, is also now available as granules for mixing in water, the FDA said.

The agency first approved baloxavir marboxil in 2018 for the treatment of acute uncomplicated influenza in people aged 12 years or older who have been symptomatic for no more than 48 hours.

A year later, the FDA expanded the indication to include people at high risk of developing influenza-related complications, such as those with asthma, chronic lung disease, diabetes, heart disease, or morbid obesity, as well as adults aged 65 years or older.

The safety and efficacy of Xofluza for influenza postexposure prophylaxis is supported by a randomized, double-blind, controlled trial involving 607 people aged 12 years and older. After exposure to a person with influenza in their household, they received a single dose of Xofluza or placebo.

The primary endpoint was the proportion of individuals who became infected with influenza and presented with fever and at least one respiratory symptom from day 1 to day 10.

Of the 303 people who received Xofluza, 1% of individuals met these criteria, compared with 13% of those who received placebo.

The most common adverse effects of Xofluza include diarrhea, bronchitis, nausea, sinusitis, and headache.

Hypersensitivity, including anaphylaxis, can occur in patients taking Xofluza. The antiviral is contraindicated in people with a known hypersensitivity reaction to Xofluza.

Xofluza should not be coadministered with dairy products, calcium-fortified beverages, laxatives, antacids, or oral supplements containing calcium, iron, magnesium, selenium, aluminium, or zinc.

Full prescribing information is available online.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

50.6 million tobacco users are not a homogeneous group

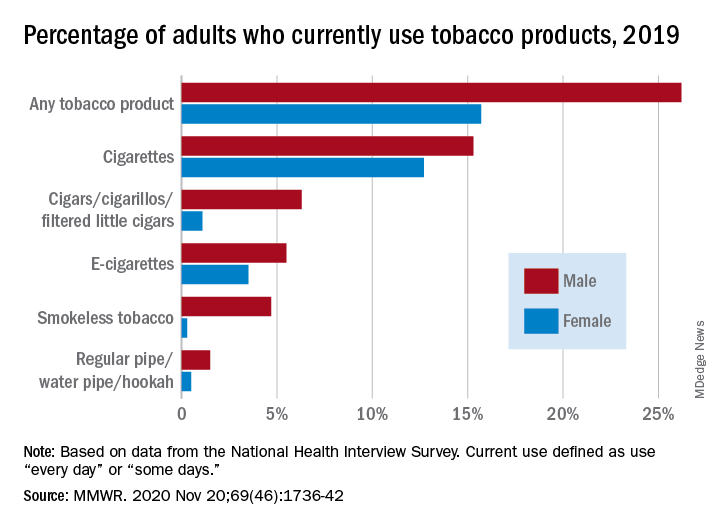

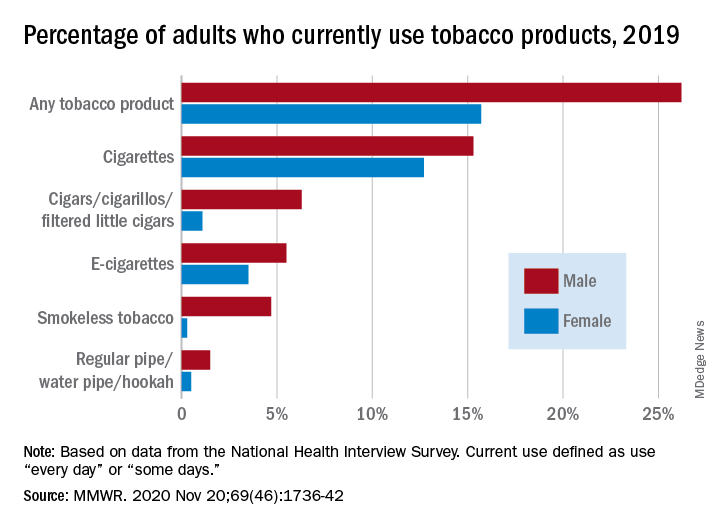

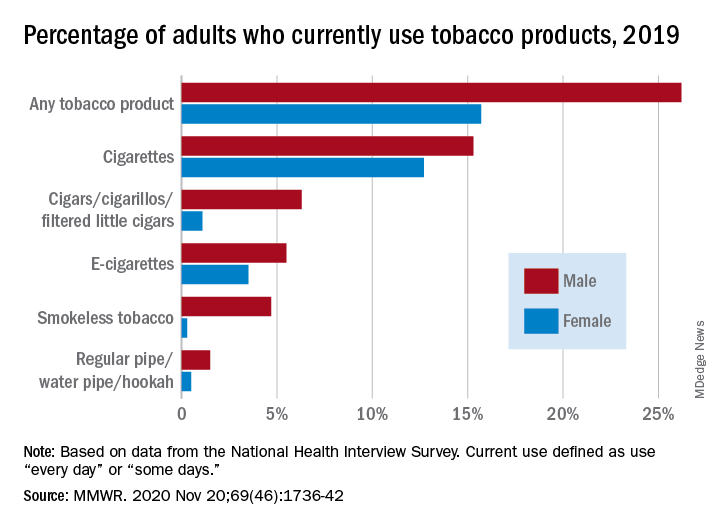

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

Cigarettes are still the product of choice among U.S. adults who use tobacco, but the youngest adults are more likely to use e-cigarettes than any other product, according to data from the 2019 National Health Interview Survey.

with cigarette use reported by the largest share of respondents (14.0%) and e-cigarettes next at 4.5%, Monica E. Cornelius, PhD, and associates said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

Among adults aged 18-24 years, however, e-cigarettes were used by 9.3% of respondents in 2019, compared with 8.0% who used cigarettes every day or some days. Current e-cigarette use was 6.4% in 25- to 44-year-olds and continued to diminish with increasing age, said Dr. Cornelius and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.

Men were more likely than women to use e-cigarettes (5.5% vs. 3.5%), and to use any tobacco product (26.2% vs. 15.7%). Use of other products, including cigarettes (15.3% for men vs. 12.7% for women), followed the same pattern to varying degrees, the national survey data show.

“Differences in prevalence of tobacco use also were also seen across population groups, with higher prevalence among those with a [high school equivalency degree], American Indian/Alaska Natives, uninsured adults and adults with Medicaid, and [lesbian, gay, or bisexual] adults,” the investigators said.

Among those groups, overall tobacco use and cigarette use were highest in those with an equivalency degree (43.8%, 37.1%), while lesbian/gay/bisexual individuals had the highest prevalence of e-cigarette use at 11.5%, they reported.

“As part of a comprehensive approach” to reduce tobacco-related disease and death, Dr. Cornelius and associates suggested, “targeted interventions are also warranted to reach subpopulations with the highest prevalence of use, which might vary by tobacco product type.”

SOURCE: Cornelius ME et al. MMWR. 2020 Nov 20;69(46);1736-42.

FROM MMWR

Metformin improves most outcomes for T2D during pregnancy

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed prior to pregnancy in 83% of women in the metformin group and in 90% of those assigned to placebo. The mean hemoglobin A1c level at randomization was 47 mmol/mol (6.5%) in both groups.

The average maternal age at baseline was approximately 35 years and mean gestational age at randomization was 16 weeks. Mean prepregnancy BMI was approximately 34 kg/m2.

Of note, only 30% were of European ethnicity.

Less weight gain, lower A1c, less insulin needed with metformin

Dr. Feig reported that there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of women with the composite primary outcome of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, birth injury, respiratory distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, or admission to neonatal intensive care lasting more than 24 hours (P = 0.86).

However, women in the metformin group had significantly less overall weight gain during pregnancy than did those in the placebo group, at –1.8 kg (P < .0001).

They also had a significantly lower last A1c level in pregnancy, at 41 mmol/mol (5.9%) versus 43.2 mmol/mol (6.1%) in those given placebo (P = .015), and required fewer insulin doses, at 1.1 versus 1.5 units/kg/day (P < .0001), which translated to a reduction of almost 44 units/day.

Women given metformin were also less likely to require Cesarean section delivery, at 53.4% versus 62.7% in the placebo group (P = .03), although there was no difference between groups in terms of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal complications, which occurred in 27.3% of women in the metformin group and 22.3% of those given placebo.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of pregnancy loss (P = .81), preterm birth (P = .16), birth injury (P = .37), respiratory distress (P = .49), and congenital anomalies (P = .16).

Average birth weight lower with metformin

However, Dr. Feig showed that the average birth weight was lower for offspring of women given metformin than those assigned to placebo, at 3.2 kg (7.05 lb) versus 3.4 kg (7.4 lb) (P = .002).

Women given metformin were also less likely to have a baby with a birth weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) or more, at 12.1% versus 19.2%, or a relative risk of 0.65 (P = .046), and a baby that was extremely large for gestational age, at 8.6% versus 14.8%, or a relative risk of 0.58 (P = .046).

But of concern, metformin was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, at 12.9% versus 6.6% with placebo, or a relative risk of 1.96 (P = .03).

Dr. Feig suggested that this may be due to a direct effect of metformin “because as we know metformin inhibits the mTOR pathway,” which is a “primary nutrient sensor in the placenta” and could “attenuate nutrient flux and fetal growth.”

She said it is not clear whether the small-for-gestational-age babies were “healthy or unhealthy.”

To investigate further, the team has launched the MiTy Kids study, which will follow the offspring in the MiTy trial to determine whether metformin during pregnancy is associated with a reduction in adiposity and improvement in insulin resistance in the babies at 2 years of age.

Who should be given metformin?

During the discussion, Helen R. Murphy, MD, PhD, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, England, asked whether Dr. Feig would recommend continuing metformin in pregnancy if it was started preconception for fertility issues rather than diabetes.

She replied: “If they don’t have diabetes and it’s simply for PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome], then I have either stopped it as soon as they got pregnant or sometimes continued it through the first trimester, and then stopped.

“If the person has diabetes, however, I think given this work, for most people I would continue it,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and the University of Toronto. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.

Type 2 diabetes was diagnosed prior to pregnancy in 83% of women in the metformin group and in 90% of those assigned to placebo. The mean hemoglobin A1c level at randomization was 47 mmol/mol (6.5%) in both groups.

The average maternal age at baseline was approximately 35 years and mean gestational age at randomization was 16 weeks. Mean prepregnancy BMI was approximately 34 kg/m2.

Of note, only 30% were of European ethnicity.

Less weight gain, lower A1c, less insulin needed with metformin

Dr. Feig reported that there was no significant difference between the treatment groups in terms of the proportion of women with the composite primary outcome of pregnancy loss, preterm birth, birth injury, respiratory distress, neonatal hypoglycemia, or admission to neonatal intensive care lasting more than 24 hours (P = 0.86).

However, women in the metformin group had significantly less overall weight gain during pregnancy than did those in the placebo group, at –1.8 kg (P < .0001).

They also had a significantly lower last A1c level in pregnancy, at 41 mmol/mol (5.9%) versus 43.2 mmol/mol (6.1%) in those given placebo (P = .015), and required fewer insulin doses, at 1.1 versus 1.5 units/kg/day (P < .0001), which translated to a reduction of almost 44 units/day.

Women given metformin were also less likely to require Cesarean section delivery, at 53.4% versus 62.7% in the placebo group (P = .03), although there was no difference between groups in terms of gestational hypertension or preeclampsia.

The most common adverse events were gastrointestinal complications, which occurred in 27.3% of women in the metformin group and 22.3% of those given placebo.

There were no significant differences between the metformin and placebo groups in rates of pregnancy loss (P = .81), preterm birth (P = .16), birth injury (P = .37), respiratory distress (P = .49), and congenital anomalies (P = .16).

Average birth weight lower with metformin

However, Dr. Feig showed that the average birth weight was lower for offspring of women given metformin than those assigned to placebo, at 3.2 kg (7.05 lb) versus 3.4 kg (7.4 lb) (P = .002).

Women given metformin were also less likely to have a baby with a birth weight of 4 kg (8.8 lb) or more, at 12.1% versus 19.2%, or a relative risk of 0.65 (P = .046), and a baby that was extremely large for gestational age, at 8.6% versus 14.8%, or a relative risk of 0.58 (P = .046).

But of concern, metformin was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, at 12.9% versus 6.6% with placebo, or a relative risk of 1.96 (P = .03).

Dr. Feig suggested that this may be due to a direct effect of metformin “because as we know metformin inhibits the mTOR pathway,” which is a “primary nutrient sensor in the placenta” and could “attenuate nutrient flux and fetal growth.”

She said it is not clear whether the small-for-gestational-age babies were “healthy or unhealthy.”

To investigate further, the team has launched the MiTy Kids study, which will follow the offspring in the MiTy trial to determine whether metformin during pregnancy is associated with a reduction in adiposity and improvement in insulin resistance in the babies at 2 years of age.

Who should be given metformin?

During the discussion, Helen R. Murphy, MD, PhD, Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, England, asked whether Dr. Feig would recommend continuing metformin in pregnancy if it was started preconception for fertility issues rather than diabetes.

She replied: “If they don’t have diabetes and it’s simply for PCOS [polycystic ovary syndrome], then I have either stopped it as soon as they got pregnant or sometimes continued it through the first trimester, and then stopped.

“If the person has diabetes, however, I think given this work, for most people I would continue it,” she said.

The study was funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Lunenfeld-Tanenbaum Research Institute, and the University of Toronto. The authors have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

including reduced weight gain, reduced insulin doses, and fewer large-for-gestational-age babies, suggest the results of a randomized controlled trial.

However, the drug was associated with an increased risk of small-for-gestational-age babies, which poses the question as to risk versus benefit of metformin on the health of offspring.

“Better understanding of the short- and long-term implications of these effects on infants will be important to properly advise patients with type 2 diabetes contemplating use of metformin during pregnancy,” said lead author Denice S. Feig, MD, Mount Sinai Hospital, Toronto.

The research was presented at the Diabetes UK Professional Conference: Online Series on Nov. 17 and recently published in The Lancet Diabetes & Endocrinology.

Summing up, Dr. Feig said that, on balance, she would be inclined to give metformin to most pregnant women with type 2 diabetes, perhaps with the exception of those who may have risk factors for small-for-gestational-age babies; for example, women who’ve had intrauterine growth restriction, who are smokers, and have significant renal disease, or have a lower body mass index.

Increased prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy

Dr. Feig said that across the developed world there have been huge increases in the prevalence of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy in recent years.

Insulin is the standard treatment for the management of type 2 diabetes in pregnancy, but these women have marked insulin resistance that worsens in pregnancy, which means their insulin requirements increase, leading to weight gain, painful injections, high cost, and noncompliance.

So despite treatment with insulin, these women continue to face increased rates of adverse maternal and fetal outcomes.

And although metformin is increasingly being used in women with type 2 diabetes during pregnancy, there is a scarcity of data on the benefits and harms of metformin use on pregnancy outcomes in these women.

The MiTy trial was therefore undertaken to determine whether metformin could improve outcomes.

The team recruited 502 women from 29 sites in Canada and Australia who had type 2 diabetes prior to pregnancy or were diagnosed during pregnancy, before 20 weeks’ gestation. The women were randomized to metformin 1 g twice daily or placebo, in addition to their usual insulin regimen, at between 6 and 28 weeks’ gestation.