User login

ID Practitioner is an independent news source that provides infectious disease specialists with timely and relevant news and commentary about clinical developments and the impact of health care policy on the infectious disease specialist’s practice. Specialty focus topics include antimicrobial resistance, emerging infections, global ID, hepatitis, HIV, hospital-acquired infections, immunizations and vaccines, influenza, mycoses, pediatric infections, and STIs. Infectious Diseases News is owned by Frontline Medical Communications.

sofosbuvir

ritonavir with dasabuvir

discount

support path

program

ritonavir

greedy

ledipasvir

assistance

viekira pak

vpak

advocacy

needy

protest

abbvie

paritaprevir

ombitasvir

direct-acting antivirals

dasabuvir

gilead

fake-ovir

support

v pak

oasis

harvoni

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-medstat-latest-articles-articles-section')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-home-idp')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-topic-idp')]

How a cheap liver drug may be the key to preventing COVID

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

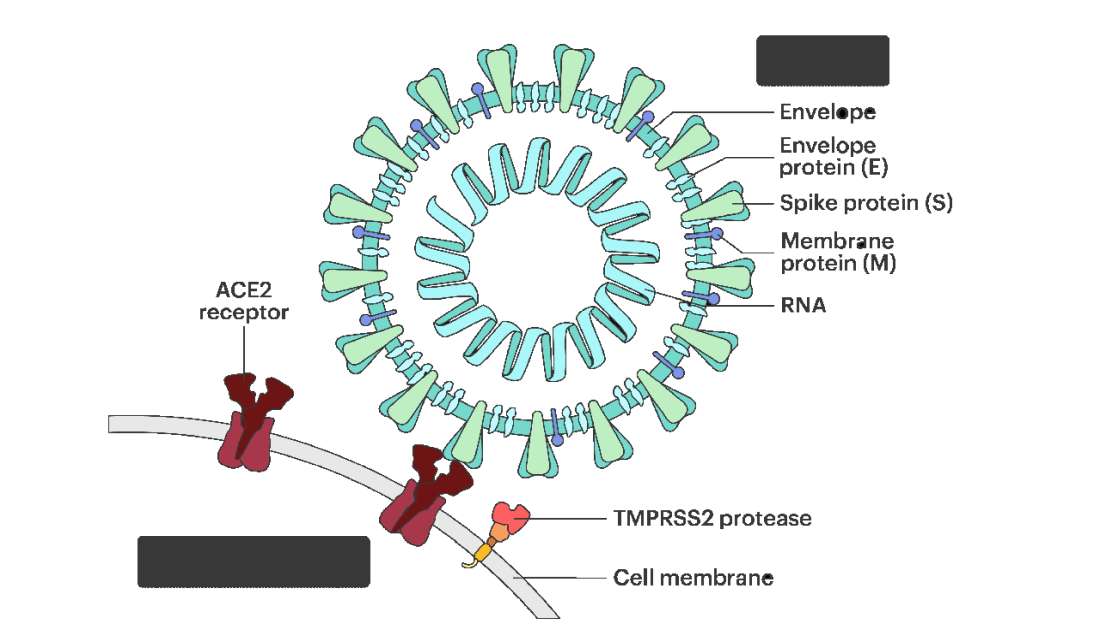

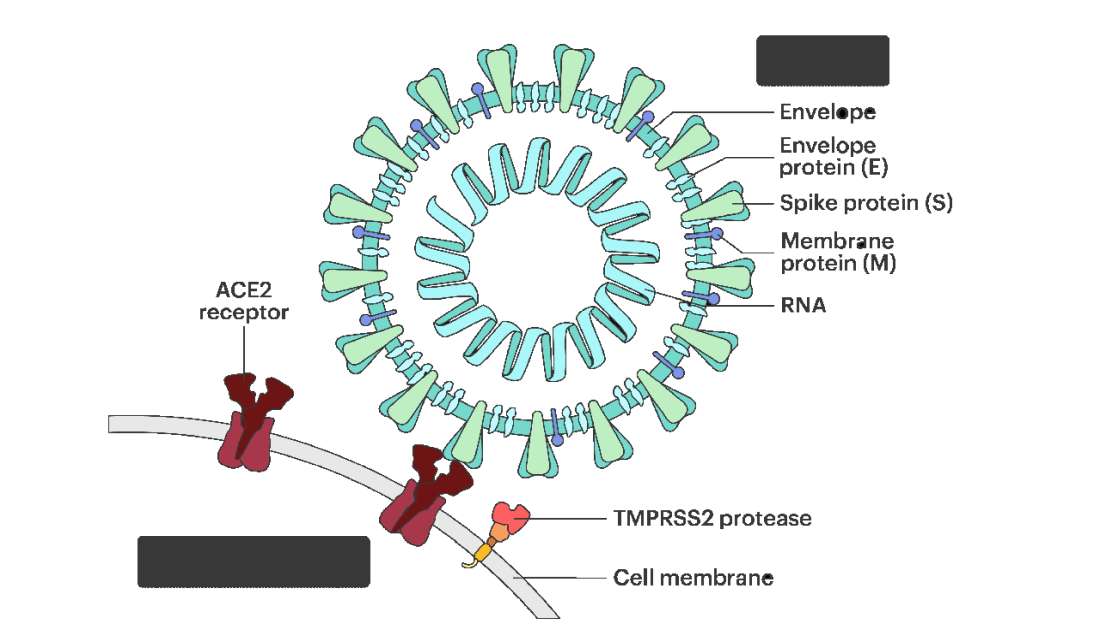

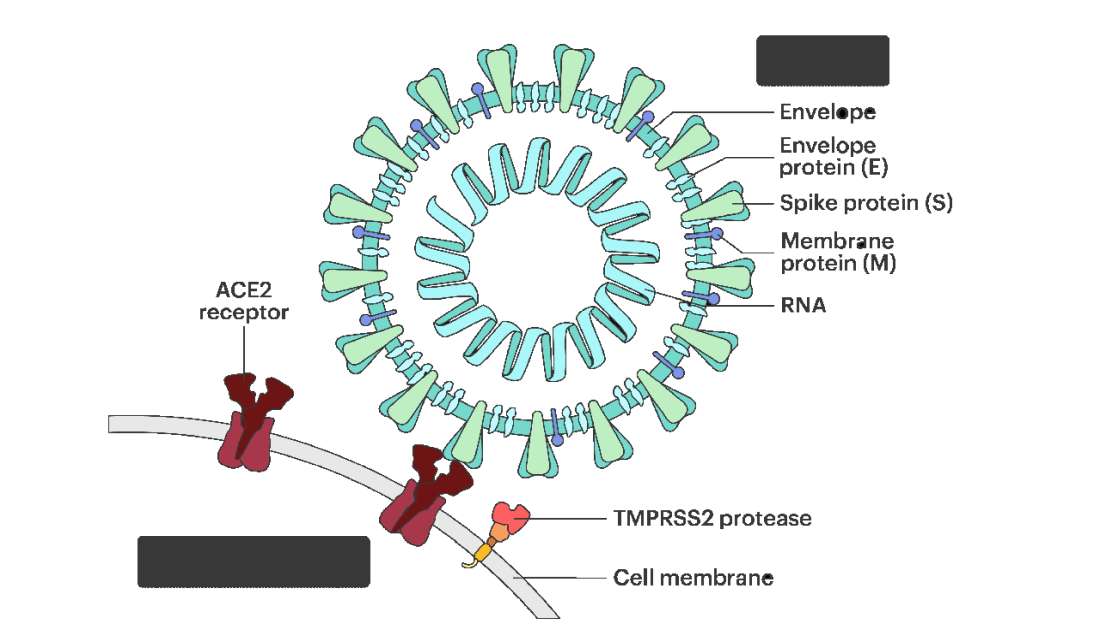

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

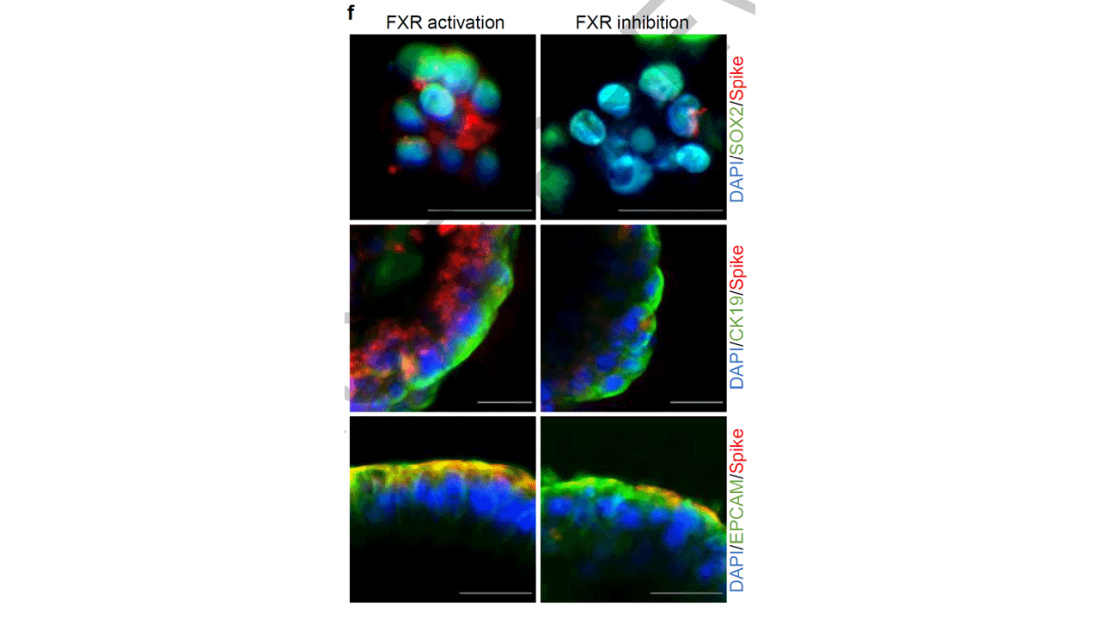

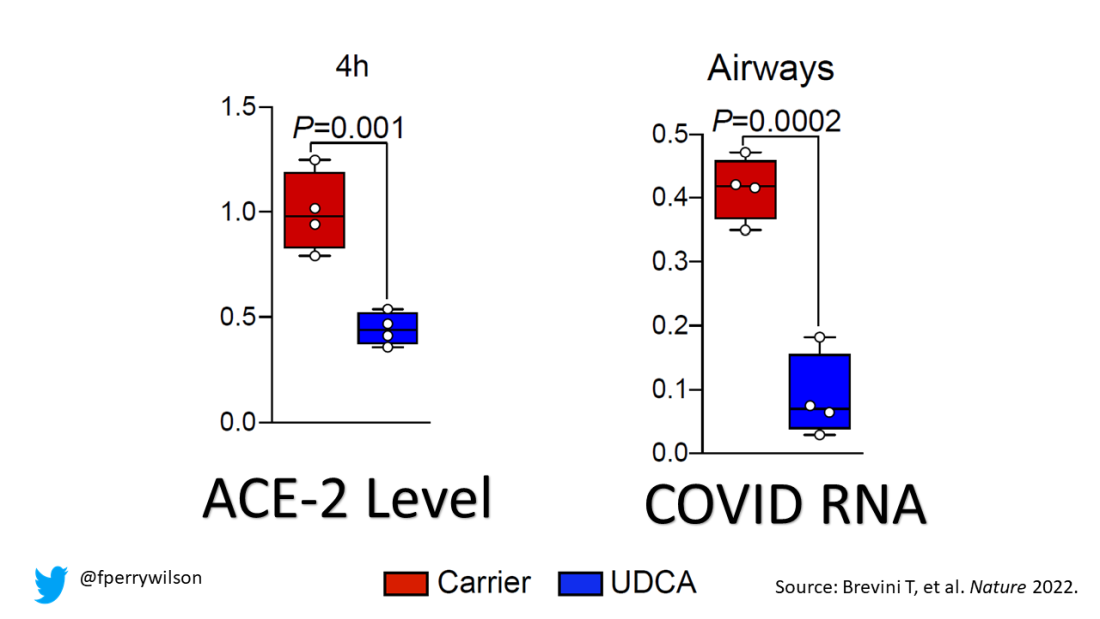

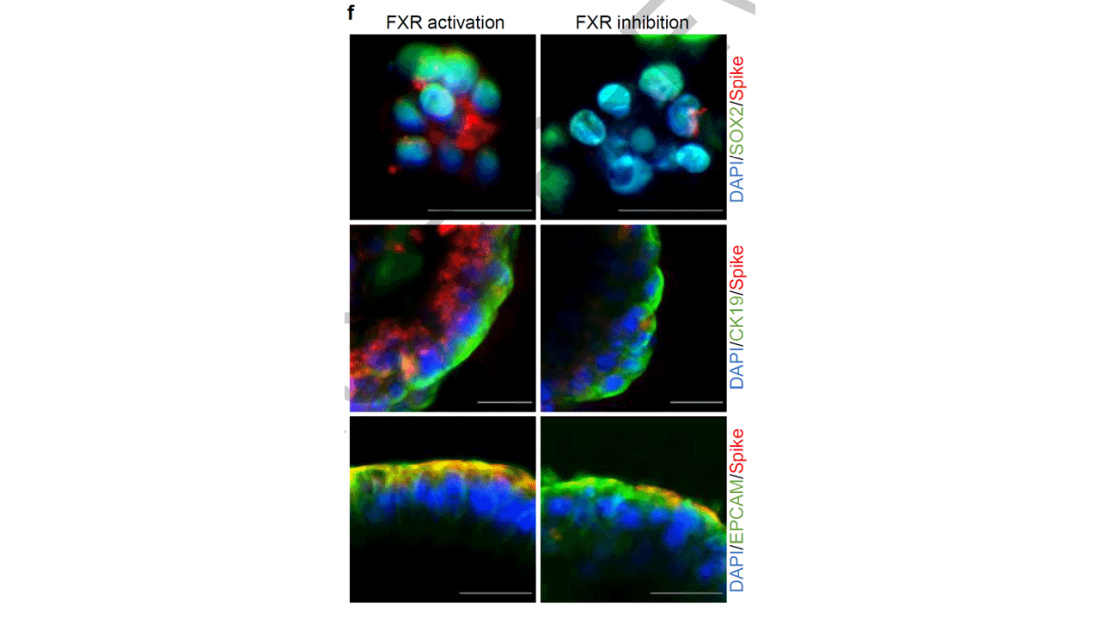

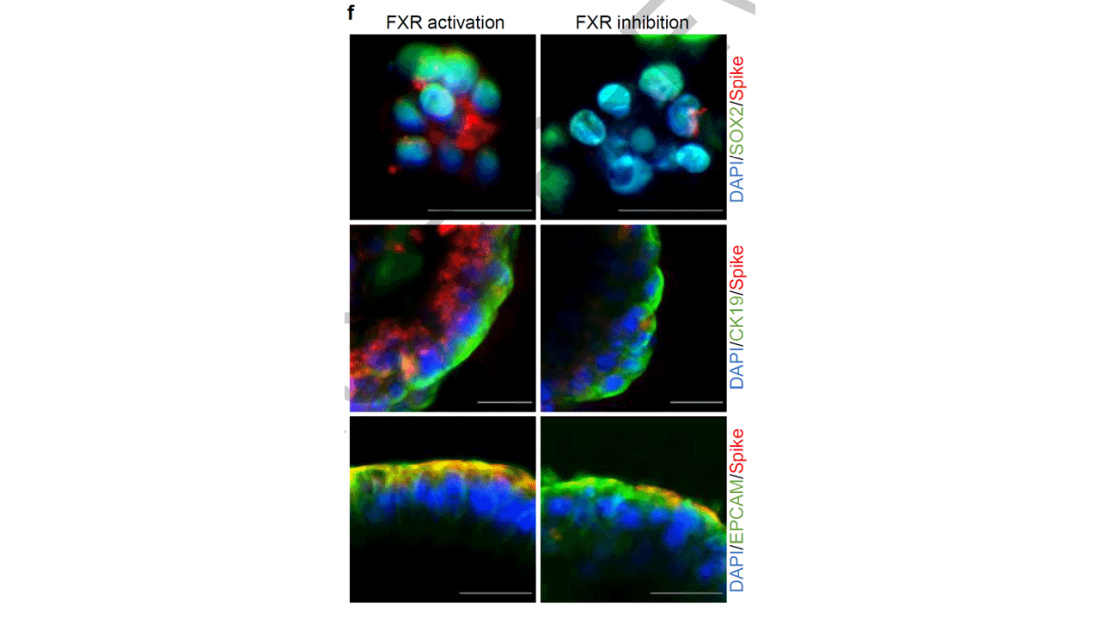

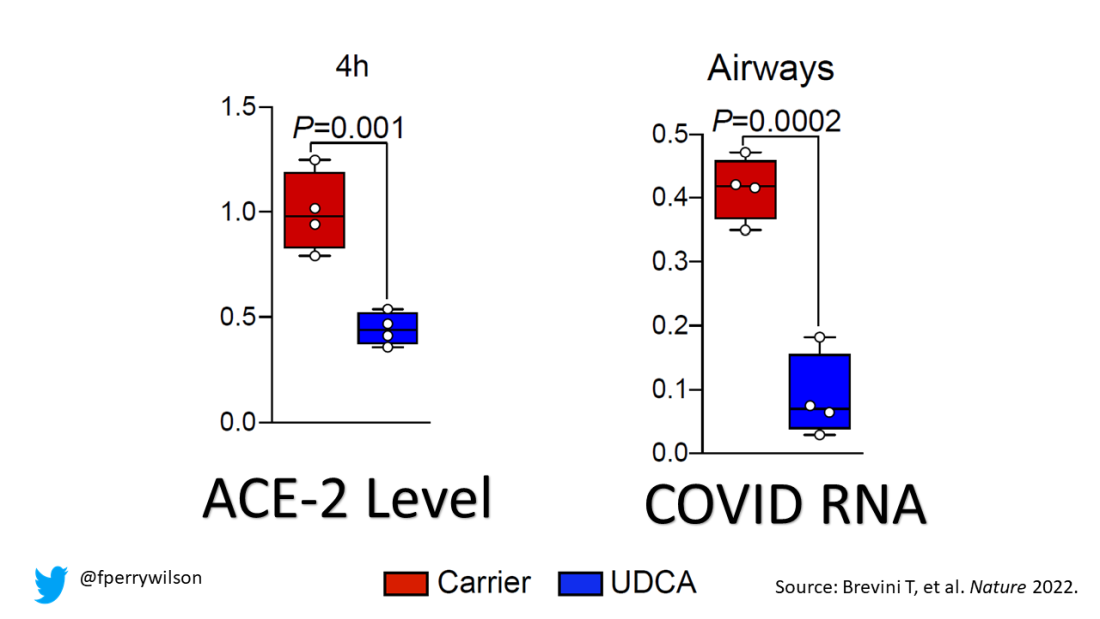

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

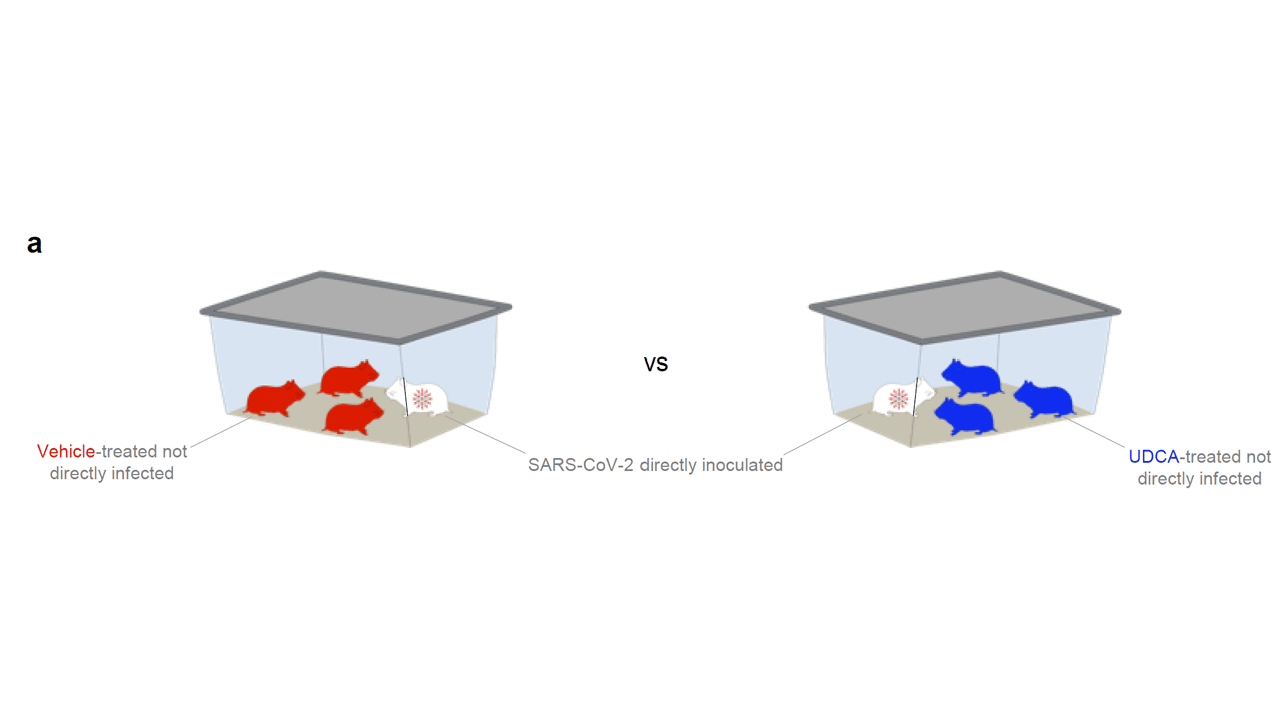

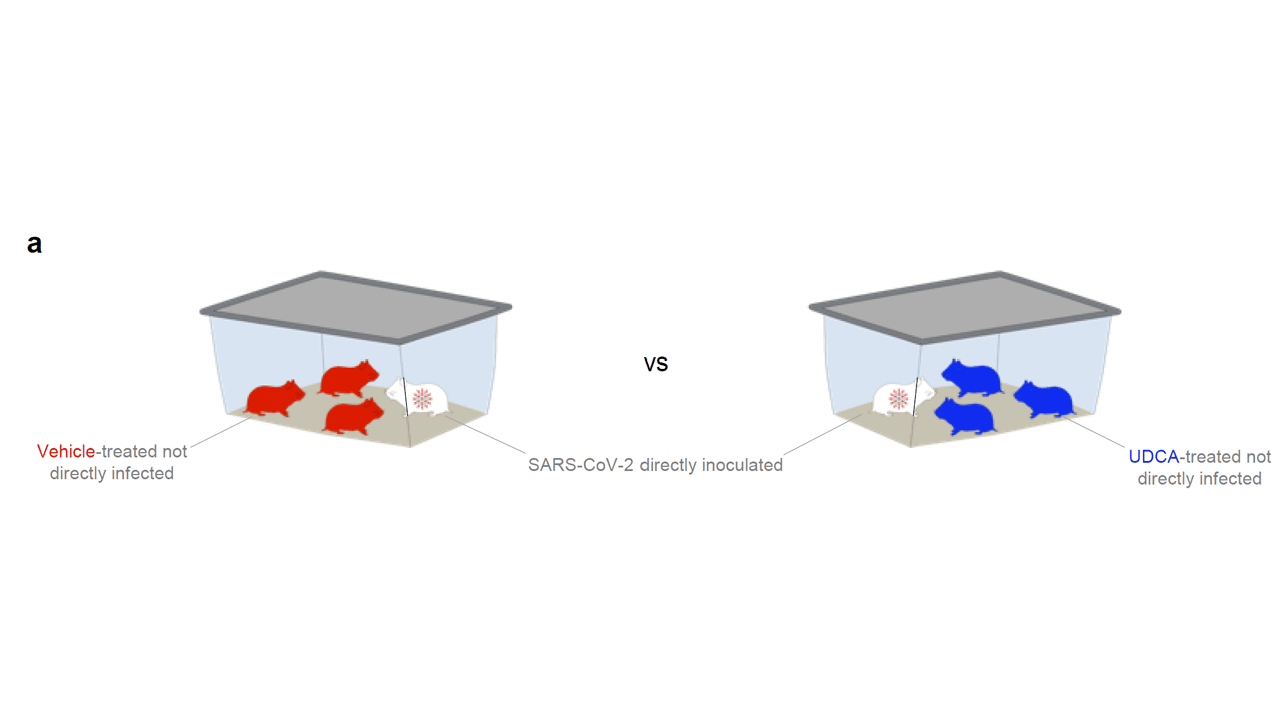

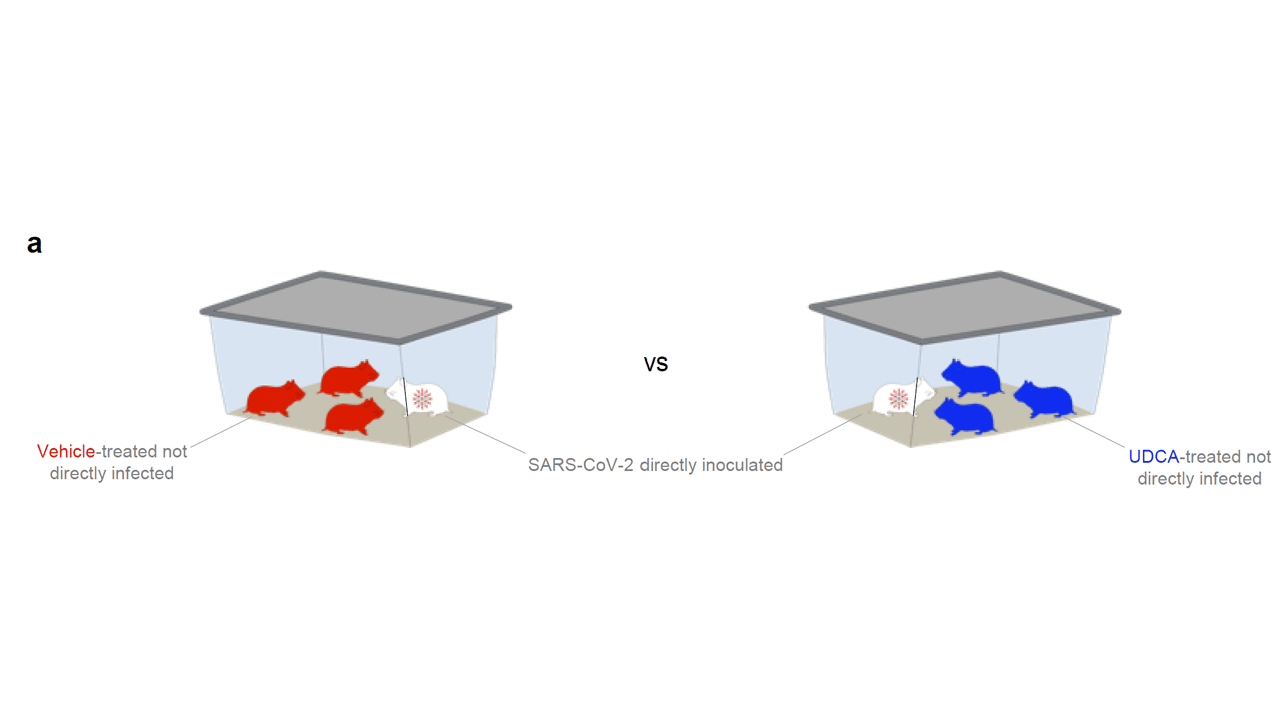

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

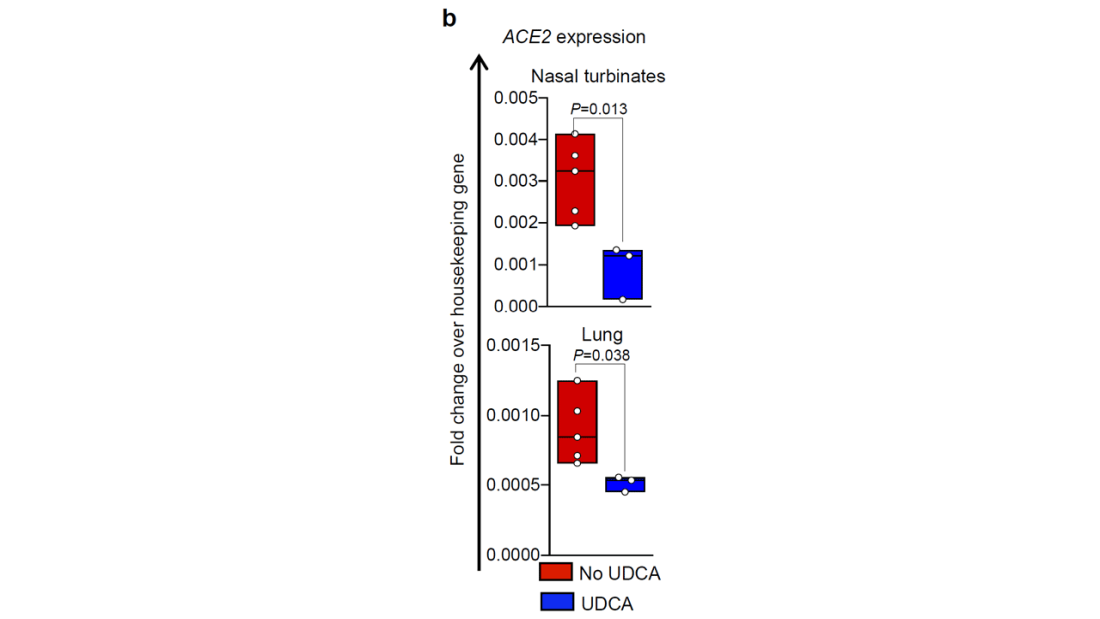

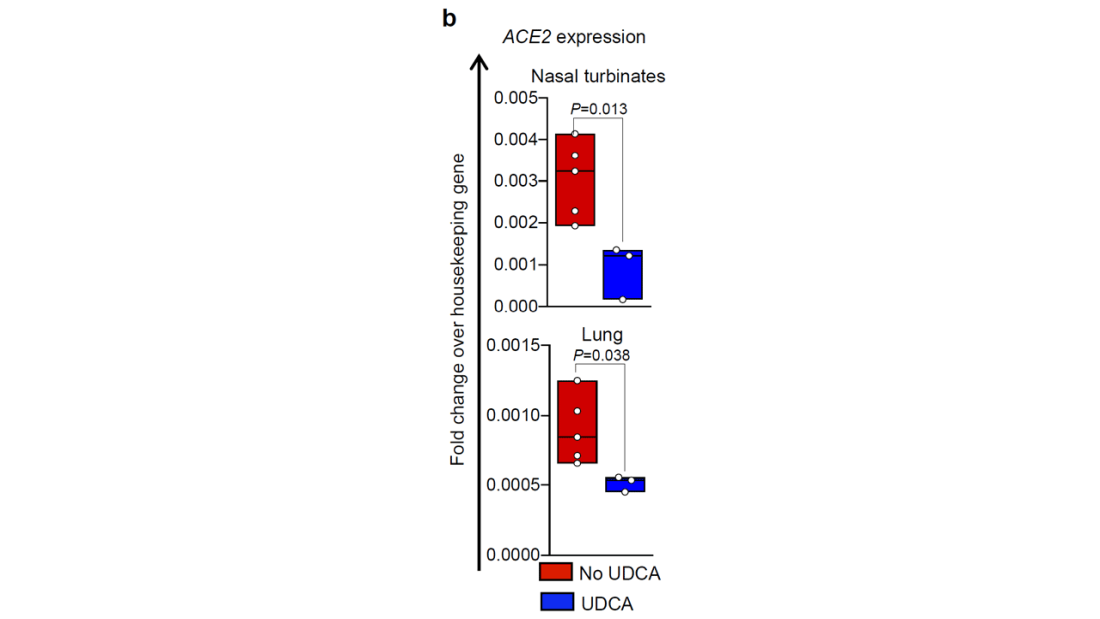

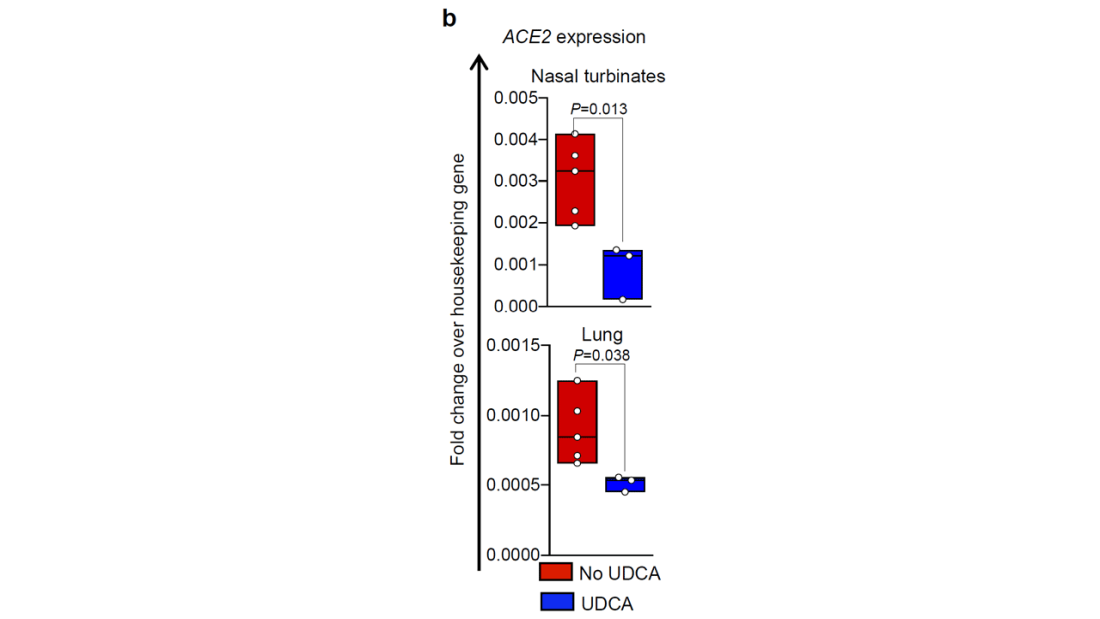

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

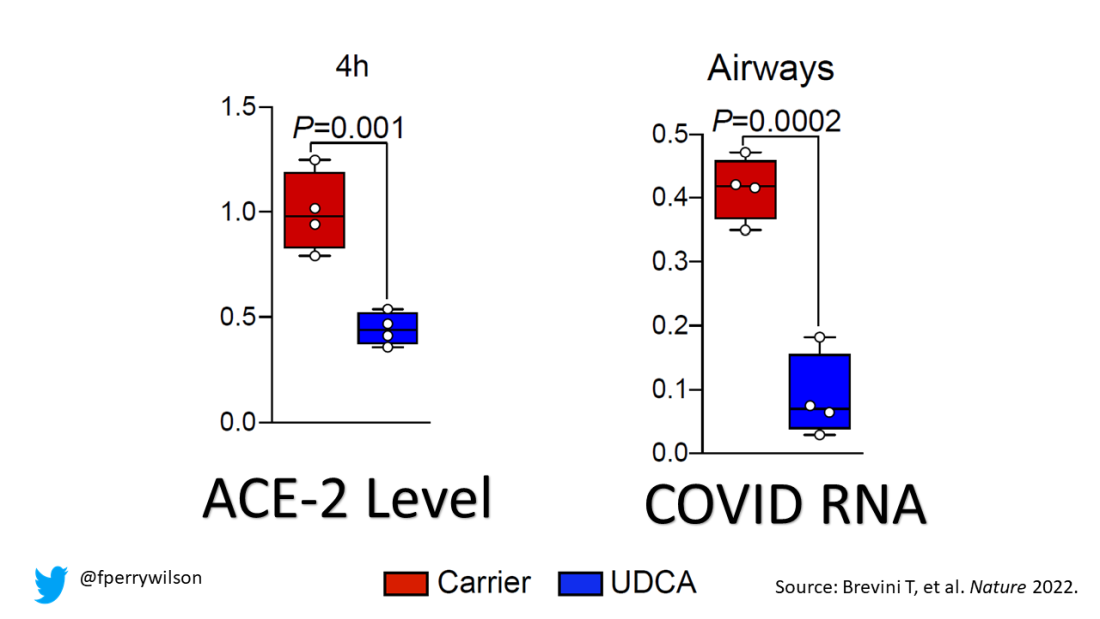

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

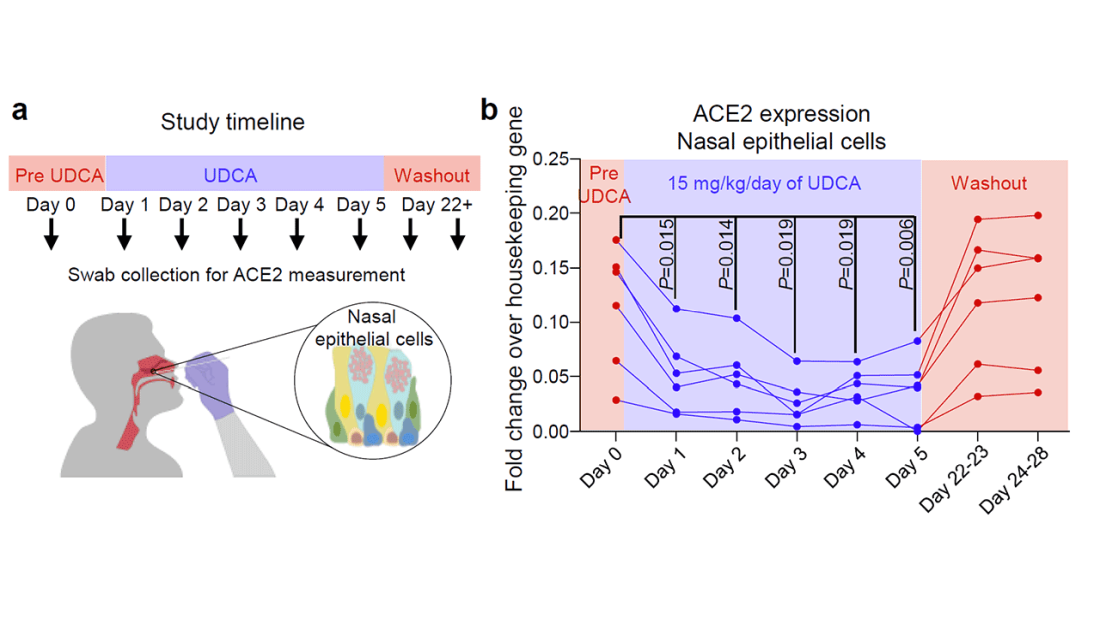

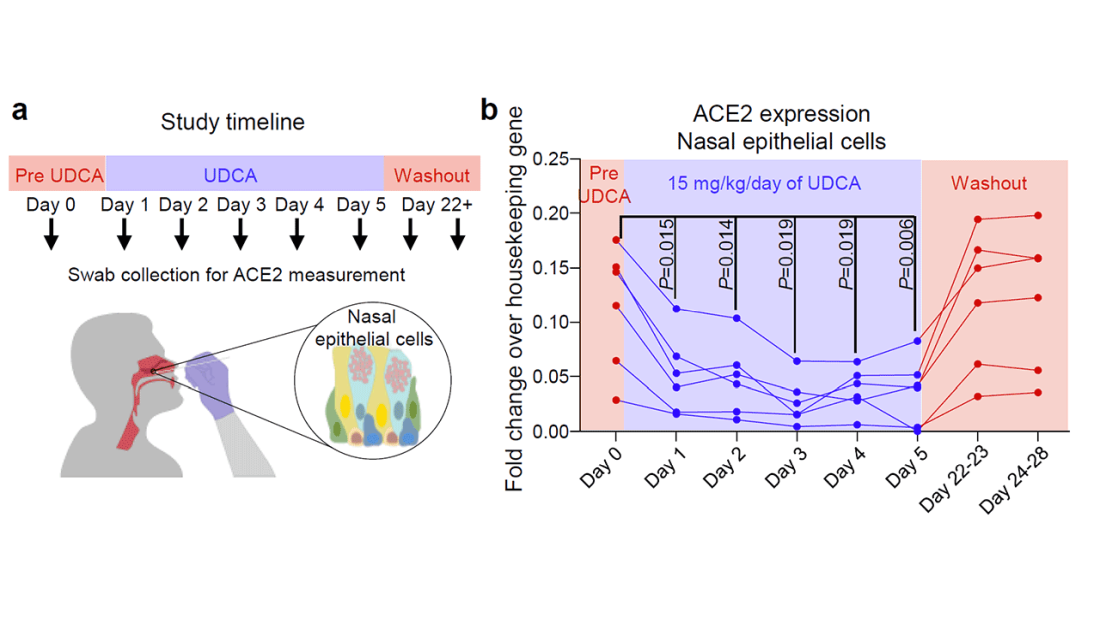

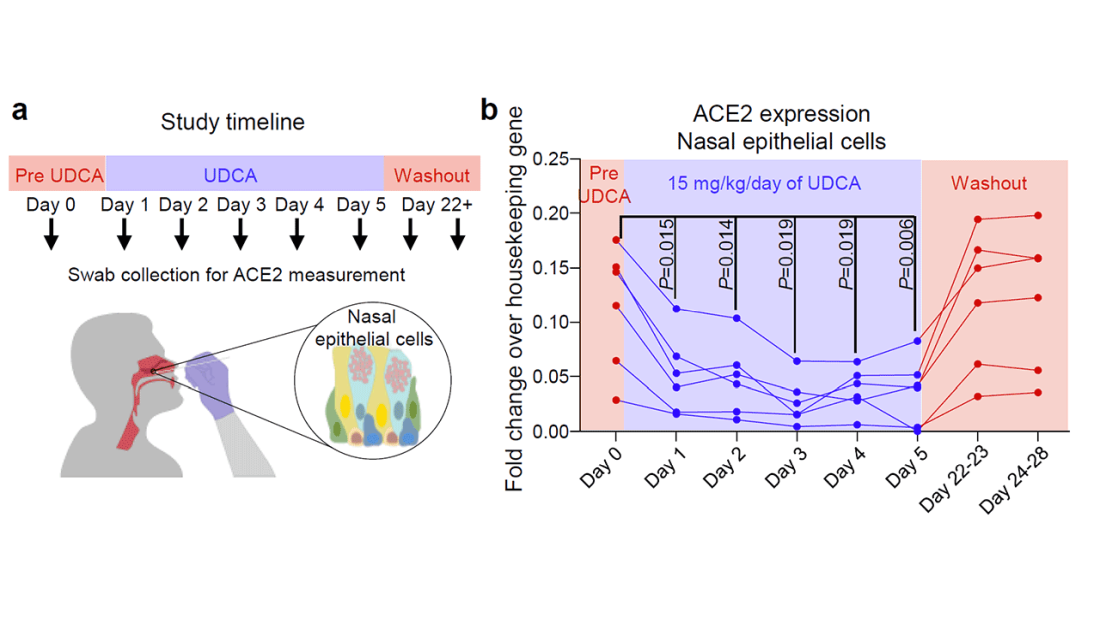

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Welcome to Impact Factor, your weekly dose of commentary on a new medical study. I’m Dr F. Perry Wilson of the Yale School of Medicine.

As soon as the pandemic started, the search was on for a medication that could stave off infection, or at least the worst consequences of infection.

One that would be cheap to make, safe, easy to distribute, and, ideally, was already available. The search had a quest-like quality, like something from a fairy tale. Society, poisoned by COVID, would find the antidote out there, somewhere, if we looked hard enough.

You know the story. There were some pretty dramatic failures: hydroxychloroquine, ivermectin. There were some successes, like dexamethasone.

I’m not here today to tell you that the antidote has been found – no, it takes large randomized trials to figure that out. But

How do you make a case that an existing drug – UDCA, in this case – might be useful to prevent or treat COVID? In contrast to prior basic-science studies, like the original ivermectin study, which essentially took a bunch of cells and virus in a tube filled with varying concentrations of the antiparasitic agent, the authors of this paper appearing in Nature give us multiple, complementary lines of evidence. Let me walk you through it.

All good science starts with a biologically plausible hypothesis. In this case, the authors recognized that SARS-CoV-2, in all its variants, requires the presence of the ACE2 receptor on the surface of cells to bind.

That is the doorway to infection. Vaccines and antibodies block the key to this door, the spike protein and its receptor binding domain. But what if you could get rid of the doors altogether?

The authors first showed that ACE2 expression is controlled by a certain transcription factor known as the farnesoid X receptor, or FXR. Reducing the binding of FXR should therefore reduce ACE2 expression.

As luck would have it, UDCA – Actigall – reduces the levels of FXR and thus the expression of ACE2 in cells.

Okay. So we have a drug that can reduce ACE2, and we know that ACE2 is necessary for the virus to infect cells. Would UDCA prevent viral infection?

They started with test tubes, showing that cells were less likely to be infected by SARS-CoV-2 in the presence of UDCA at concentrations similar to what humans achieve in their blood after standard dosing. The red staining here is spike protein; you can see that it is markedly lower in the cells exposed to UDCA.

So far, so good. But test tubes aren’t people. So they moved up to mice and Syrian golden hamsters. These cute fellows are quite susceptible to human COVID and have been a model organism in countless studies

Mice and hamsters treated with UDCA in the presence of littermates with COVID infections were less likely to become infected themselves compared with mice not so treated. They also showed that mice and hamsters treated with UDCA had lower levels of ACE2 in their nasal passages.

Of course, mice aren’t humans either. So the researchers didn’t stop there.

To determine the effects of UDCA on human tissue, they utilized perfused human lungs that had been declined for transplantation. The lungs were perfused with a special fluid to keep them viable, and were mechanically ventilated. One lung was exposed to UDCA and the other served as a control. The authors were able to show that ACE2 levels went down in the exposed lung. And, importantly, when samples of tissue from both lungs were exposed to SARS-CoV-2, the lung tissue exposed to UDCA had lower levels of viral infection.

They didn’t stop there.

Eight human volunteers were recruited to take UDCA for 5 days. ACE2 levels in the nasal passages went down over the course of treatment. They confirmed those results from a proteomics dataset with several hundred people who had received UDCA for clinical reasons. Treated individuals had lower ACE2 levels.

Finally, they looked at the epidemiologic effect. They examined a dataset that contained information on over 1,000 patients with liver disease who had contracted COVID-19, 31 of whom had been receiving UDCA. Even after adjustment for baseline differences, those receiving UDCA were less likely to be hospitalized, require an ICU, or die.

Okay, we’ll stop there. Reading this study, all I could think was, Yes! This is how you generate evidence that you have a drug that might work – step by careful step.

But let’s be careful as well. Does this study show that taking Actigall will prevent COVID? Of course not. It doesn’t show that it will treat COVID either. But I bring it up because the rigor of this study stands in contrast to those that generated huge enthusiasm earlier in the pandemic only to let us down in randomized trials. If there has been a drug out there this whole time which will prevent or treat COVID, this is how we’ll find it. The next step? Test it in a randomized trial.

For Medscape, I’m Perry Wilson.

F. Perry Wilson, MD, MSCE, is an associate professor of medicine and director of Yale’s Clinical and Translational Research Accelerator. He disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this video transcript first appeared on Medscape.com.

Paxlovid has been free so far. Next year, sticker shock awaits

Nearly 6 million Americans have taken Paxlovid for free, courtesy of the federal government. The Pfizer pill has helped prevent many people infected with COVID-19 from being hospitalized or dying, and it may even reduce the risk of developing long COVID.

And that means fewer people will get the potentially lifesaving treatments, experts said.

“I think the numbers will go way down,” said Jill Rosenthal, director of public health policy at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. A bill for several hundred dollars or more would lead many people to decide the medication isn’t worth the price, she said.

In response to the unprecedented public health crisis caused by COVID, the federal government spent billions of dollars on developing new vaccines and treatments, to swift success: Less than a year after the pandemic was declared, medical workers got their first vaccines. But as many people have refused the shots and stopped wearing masks, the virus still rages and mutates. In 2022 alone, 250,000 Americans have died from COVID, more than from strokes or diabetes.

But soon the Department of Health & Human Services will stop supplying COVID treatments, and pharmacies will purchase and bill for them the same way they do for antibiotic pills or asthma inhalers. Paxlovid is expected to hit the private market in mid-2023, according to HHS plans shared in an October meeting with state health officials and clinicians. Merck’s Lagevrio, a less-effective COVID treatment pill, and AstraZeneca’s Evusheld, a preventive therapy for the immunocompromised, are on track to be commercialized sooner, sometime in the winter.

The U.S. government has so far purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid, priced at about $530 each, a discount for buying in bulk that Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla called “really very attractive” to the federal government in a July earnings call. The drug will cost far more on the private market, although in a statement to Kaiser Health News, Pfizer declined to share the planned price. The government will also stop paying for the company’s COVID vaccine next year – those shots will quadruple in price, from the discount rate the government pays of $30 to about $120.

Mr. Bourla told investors in November that he expects the move will make Paxlovid and its COVID vaccine “a multibillion-dollars franchise.”

Nearly 9 in 10 people dying from the virus now are 65 or older. Yet federal law restricts Medicare Part D – the prescription drug program that covers nearly 50 million seniors – from covering the COVID treatment pills. The medications are meant for those most at risk of serious illness, including seniors.

Paxlovid and the other treatments are currently available under an emergency use authorization from the FDA, a fast-track review used in extraordinary situations. Although Pfizer applied for full approval in June, the process can take anywhere from several months to years. And Medicare Part D can’t cover any medications without that full stamp of approval.

Paying out-of-pocket would be “a substantial barrier” for seniors on Medicare – the very people who would benefit most from the drug, wrote federal health experts.

“From a public health perspective, and even from a health care capacity and cost perspective, it would just defy reason to not continue to make these drugs readily available,” said Dr. Larry Madoff, medical director of Massachusetts’s Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. He’s hopeful that the federal health agency will find a way to set aside unused doses for seniors and people without insurance.

In mid-November, the White House requested that Congress approve an additional $2.5 billion for COVID therapeutics and vaccines to make sure people can afford the medications when they’re no longer free. But there’s little hope it will be approved – the Senate voted that same day to end the public health emergency and denied similar requests in recent months.

Many Americans have already faced hurdles just getting a prescription for COVID treatment. Although the federal government doesn’t track who’s gotten the drug, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study using data from 30 medical centers found that Black and Hispanic patients with COVID were much less likely to receive Paxlovid than White patients. (Hispanic people can be of any race or combination of races.) And when the government is no longer picking up the tab, experts predict that these gaps by race, income, and geography will widen.

People in Northeastern states used the drug far more often than those in the rest of the country, according to a KHN analysis of Paxlovid use in September and October. But it wasn’t because people in the region were getting sick from COVID at much higher rates – instead, many of those states offered better access to health care to begin with and created special programs to get Paxlovid to their residents.

About 10 mostly Democratic states and several large counties in the Northeast and elsewhere created free “test-to-treat” programs that allow their residents to get an immediate doctor visit and prescription for treatment after testing positive for COVID. In Massachusetts, more than 20,000 residents have used the state’s video and phone hotline, which is available 7 days a week in 13 languages. Massachusetts, which has the highest insurance rate in the country and relatively low travel times to pharmacies, had the second-highest Paxlovid usage rate among states this fall.

States with higher COVID death rates, like Florida and Kentucky, where residents must travel farther for health care and are more likely to be uninsured, used the drug less often. Without no-cost test-to-treat options, residents have struggled to get prescriptions even though the drug itself is still free.

“If you look at access to medications for people who are uninsured, I think that there’s no question that will widen those disparities,” Ms. Rosenthal said.

People who get insurance through their jobs could face high copays at the register, too, just as they do for insulin and other expensive or brand-name drugs.

Most private insurance companies will end up covering COVID therapeutics to some extent, said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. After all, the pills are cheaper than a hospital stay. But for most people who get insurance through their jobs, there are “really no rules at all,” she said. Some insurers could take months to add the drugs to their plans or decide not to pay for them.

And the additional cost means many people will go without the medication. “We know from lots of research that when people face cost sharing for these drugs that they need to take, they will often forgo or cut back,” Ms. Corlette said.

One group doesn’t need to worry about sticker shock. Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income adults and children, will cover the treatments in full until at least early 2024.

HHS officials could set aside any leftover taxpayer-funded medication for people who can’t afford to pay the full cost, but they haven’t shared any concrete plans to do so. The government purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid and 3 million of Lagevrio. Fewer than a third have been used, and usage has fallen in recent months, according to KHN’s analysis of the data from HHS.

Sixty percent of the government’s supply of Evusheld is also still available, although the COVID prevention therapy is less effective against new strains of the virus. The health department in one state, New Mexico, has recommended against using it.

HHS did not make officials available for an interview or answer written questions about the commercialization plans.

The government created a potential workaround when they moved bebtelovimab, another COVID treatment, to the private market this summer. It now retails for $2,100 per patient. The agency set aside the remaining 60,000 government-purchased doses that hospitals could use to treat uninsured patients in a convoluted dose-replacement process. But it’s hard to tell how well that setup would work for Paxlovid: Bebtelovimab was already much less popular, and the FDA halted its use on Nov. 30 because it’s less effective against current strains of the virus.

Federal officials and insurance companies would have good reason to make sure patients can continue to afford COVID drugs: They’re far cheaper than if patients land in the emergency room.

“The medications are so worthwhile,” said Dr. Madoff, the Massachusetts health official. “They’re not expensive in the grand scheme of health care costs.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Nearly 6 million Americans have taken Paxlovid for free, courtesy of the federal government. The Pfizer pill has helped prevent many people infected with COVID-19 from being hospitalized or dying, and it may even reduce the risk of developing long COVID.

And that means fewer people will get the potentially lifesaving treatments, experts said.

“I think the numbers will go way down,” said Jill Rosenthal, director of public health policy at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. A bill for several hundred dollars or more would lead many people to decide the medication isn’t worth the price, she said.

In response to the unprecedented public health crisis caused by COVID, the federal government spent billions of dollars on developing new vaccines and treatments, to swift success: Less than a year after the pandemic was declared, medical workers got their first vaccines. But as many people have refused the shots and stopped wearing masks, the virus still rages and mutates. In 2022 alone, 250,000 Americans have died from COVID, more than from strokes or diabetes.

But soon the Department of Health & Human Services will stop supplying COVID treatments, and pharmacies will purchase and bill for them the same way they do for antibiotic pills or asthma inhalers. Paxlovid is expected to hit the private market in mid-2023, according to HHS plans shared in an October meeting with state health officials and clinicians. Merck’s Lagevrio, a less-effective COVID treatment pill, and AstraZeneca’s Evusheld, a preventive therapy for the immunocompromised, are on track to be commercialized sooner, sometime in the winter.

The U.S. government has so far purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid, priced at about $530 each, a discount for buying in bulk that Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla called “really very attractive” to the federal government in a July earnings call. The drug will cost far more on the private market, although in a statement to Kaiser Health News, Pfizer declined to share the planned price. The government will also stop paying for the company’s COVID vaccine next year – those shots will quadruple in price, from the discount rate the government pays of $30 to about $120.

Mr. Bourla told investors in November that he expects the move will make Paxlovid and its COVID vaccine “a multibillion-dollars franchise.”

Nearly 9 in 10 people dying from the virus now are 65 or older. Yet federal law restricts Medicare Part D – the prescription drug program that covers nearly 50 million seniors – from covering the COVID treatment pills. The medications are meant for those most at risk of serious illness, including seniors.

Paxlovid and the other treatments are currently available under an emergency use authorization from the FDA, a fast-track review used in extraordinary situations. Although Pfizer applied for full approval in June, the process can take anywhere from several months to years. And Medicare Part D can’t cover any medications without that full stamp of approval.

Paying out-of-pocket would be “a substantial barrier” for seniors on Medicare – the very people who would benefit most from the drug, wrote federal health experts.

“From a public health perspective, and even from a health care capacity and cost perspective, it would just defy reason to not continue to make these drugs readily available,” said Dr. Larry Madoff, medical director of Massachusetts’s Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. He’s hopeful that the federal health agency will find a way to set aside unused doses for seniors and people without insurance.

In mid-November, the White House requested that Congress approve an additional $2.5 billion for COVID therapeutics and vaccines to make sure people can afford the medications when they’re no longer free. But there’s little hope it will be approved – the Senate voted that same day to end the public health emergency and denied similar requests in recent months.

Many Americans have already faced hurdles just getting a prescription for COVID treatment. Although the federal government doesn’t track who’s gotten the drug, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study using data from 30 medical centers found that Black and Hispanic patients with COVID were much less likely to receive Paxlovid than White patients. (Hispanic people can be of any race or combination of races.) And when the government is no longer picking up the tab, experts predict that these gaps by race, income, and geography will widen.

People in Northeastern states used the drug far more often than those in the rest of the country, according to a KHN analysis of Paxlovid use in September and October. But it wasn’t because people in the region were getting sick from COVID at much higher rates – instead, many of those states offered better access to health care to begin with and created special programs to get Paxlovid to their residents.

About 10 mostly Democratic states and several large counties in the Northeast and elsewhere created free “test-to-treat” programs that allow their residents to get an immediate doctor visit and prescription for treatment after testing positive for COVID. In Massachusetts, more than 20,000 residents have used the state’s video and phone hotline, which is available 7 days a week in 13 languages. Massachusetts, which has the highest insurance rate in the country and relatively low travel times to pharmacies, had the second-highest Paxlovid usage rate among states this fall.

States with higher COVID death rates, like Florida and Kentucky, where residents must travel farther for health care and are more likely to be uninsured, used the drug less often. Without no-cost test-to-treat options, residents have struggled to get prescriptions even though the drug itself is still free.

“If you look at access to medications for people who are uninsured, I think that there’s no question that will widen those disparities,” Ms. Rosenthal said.

People who get insurance through their jobs could face high copays at the register, too, just as they do for insulin and other expensive or brand-name drugs.

Most private insurance companies will end up covering COVID therapeutics to some extent, said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. After all, the pills are cheaper than a hospital stay. But for most people who get insurance through their jobs, there are “really no rules at all,” she said. Some insurers could take months to add the drugs to their plans or decide not to pay for them.

And the additional cost means many people will go without the medication. “We know from lots of research that when people face cost sharing for these drugs that they need to take, they will often forgo or cut back,” Ms. Corlette said.

One group doesn’t need to worry about sticker shock. Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income adults and children, will cover the treatments in full until at least early 2024.

HHS officials could set aside any leftover taxpayer-funded medication for people who can’t afford to pay the full cost, but they haven’t shared any concrete plans to do so. The government purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid and 3 million of Lagevrio. Fewer than a third have been used, and usage has fallen in recent months, according to KHN’s analysis of the data from HHS.

Sixty percent of the government’s supply of Evusheld is also still available, although the COVID prevention therapy is less effective against new strains of the virus. The health department in one state, New Mexico, has recommended against using it.

HHS did not make officials available for an interview or answer written questions about the commercialization plans.

The government created a potential workaround when they moved bebtelovimab, another COVID treatment, to the private market this summer. It now retails for $2,100 per patient. The agency set aside the remaining 60,000 government-purchased doses that hospitals could use to treat uninsured patients in a convoluted dose-replacement process. But it’s hard to tell how well that setup would work for Paxlovid: Bebtelovimab was already much less popular, and the FDA halted its use on Nov. 30 because it’s less effective against current strains of the virus.

Federal officials and insurance companies would have good reason to make sure patients can continue to afford COVID drugs: They’re far cheaper than if patients land in the emergency room.

“The medications are so worthwhile,” said Dr. Madoff, the Massachusetts health official. “They’re not expensive in the grand scheme of health care costs.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Nearly 6 million Americans have taken Paxlovid for free, courtesy of the federal government. The Pfizer pill has helped prevent many people infected with COVID-19 from being hospitalized or dying, and it may even reduce the risk of developing long COVID.

And that means fewer people will get the potentially lifesaving treatments, experts said.

“I think the numbers will go way down,” said Jill Rosenthal, director of public health policy at the Center for American Progress, a left-leaning think tank. A bill for several hundred dollars or more would lead many people to decide the medication isn’t worth the price, she said.

In response to the unprecedented public health crisis caused by COVID, the federal government spent billions of dollars on developing new vaccines and treatments, to swift success: Less than a year after the pandemic was declared, medical workers got their first vaccines. But as many people have refused the shots and stopped wearing masks, the virus still rages and mutates. In 2022 alone, 250,000 Americans have died from COVID, more than from strokes or diabetes.

But soon the Department of Health & Human Services will stop supplying COVID treatments, and pharmacies will purchase and bill for them the same way they do for antibiotic pills or asthma inhalers. Paxlovid is expected to hit the private market in mid-2023, according to HHS plans shared in an October meeting with state health officials and clinicians. Merck’s Lagevrio, a less-effective COVID treatment pill, and AstraZeneca’s Evusheld, a preventive therapy for the immunocompromised, are on track to be commercialized sooner, sometime in the winter.

The U.S. government has so far purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid, priced at about $530 each, a discount for buying in bulk that Pfizer CEO Albert Bourla called “really very attractive” to the federal government in a July earnings call. The drug will cost far more on the private market, although in a statement to Kaiser Health News, Pfizer declined to share the planned price. The government will also stop paying for the company’s COVID vaccine next year – those shots will quadruple in price, from the discount rate the government pays of $30 to about $120.

Mr. Bourla told investors in November that he expects the move will make Paxlovid and its COVID vaccine “a multibillion-dollars franchise.”

Nearly 9 in 10 people dying from the virus now are 65 or older. Yet federal law restricts Medicare Part D – the prescription drug program that covers nearly 50 million seniors – from covering the COVID treatment pills. The medications are meant for those most at risk of serious illness, including seniors.

Paxlovid and the other treatments are currently available under an emergency use authorization from the FDA, a fast-track review used in extraordinary situations. Although Pfizer applied for full approval in June, the process can take anywhere from several months to years. And Medicare Part D can’t cover any medications without that full stamp of approval.

Paying out-of-pocket would be “a substantial barrier” for seniors on Medicare – the very people who would benefit most from the drug, wrote federal health experts.

“From a public health perspective, and even from a health care capacity and cost perspective, it would just defy reason to not continue to make these drugs readily available,” said Dr. Larry Madoff, medical director of Massachusetts’s Bureau of Infectious Disease and Laboratory Sciences. He’s hopeful that the federal health agency will find a way to set aside unused doses for seniors and people without insurance.

In mid-November, the White House requested that Congress approve an additional $2.5 billion for COVID therapeutics and vaccines to make sure people can afford the medications when they’re no longer free. But there’s little hope it will be approved – the Senate voted that same day to end the public health emergency and denied similar requests in recent months.

Many Americans have already faced hurdles just getting a prescription for COVID treatment. Although the federal government doesn’t track who’s gotten the drug, a Centers for Disease Control and Prevention study using data from 30 medical centers found that Black and Hispanic patients with COVID were much less likely to receive Paxlovid than White patients. (Hispanic people can be of any race or combination of races.) And when the government is no longer picking up the tab, experts predict that these gaps by race, income, and geography will widen.

People in Northeastern states used the drug far more often than those in the rest of the country, according to a KHN analysis of Paxlovid use in September and October. But it wasn’t because people in the region were getting sick from COVID at much higher rates – instead, many of those states offered better access to health care to begin with and created special programs to get Paxlovid to their residents.

About 10 mostly Democratic states and several large counties in the Northeast and elsewhere created free “test-to-treat” programs that allow their residents to get an immediate doctor visit and prescription for treatment after testing positive for COVID. In Massachusetts, more than 20,000 residents have used the state’s video and phone hotline, which is available 7 days a week in 13 languages. Massachusetts, which has the highest insurance rate in the country and relatively low travel times to pharmacies, had the second-highest Paxlovid usage rate among states this fall.

States with higher COVID death rates, like Florida and Kentucky, where residents must travel farther for health care and are more likely to be uninsured, used the drug less often. Without no-cost test-to-treat options, residents have struggled to get prescriptions even though the drug itself is still free.

“If you look at access to medications for people who are uninsured, I think that there’s no question that will widen those disparities,” Ms. Rosenthal said.

People who get insurance through their jobs could face high copays at the register, too, just as they do for insulin and other expensive or brand-name drugs.

Most private insurance companies will end up covering COVID therapeutics to some extent, said Sabrina Corlette, a research professor at Georgetown University’s Center on Health Insurance Reforms. After all, the pills are cheaper than a hospital stay. But for most people who get insurance through their jobs, there are “really no rules at all,” she said. Some insurers could take months to add the drugs to their plans or decide not to pay for them.

And the additional cost means many people will go without the medication. “We know from lots of research that when people face cost sharing for these drugs that they need to take, they will often forgo or cut back,” Ms. Corlette said.

One group doesn’t need to worry about sticker shock. Medicaid, the public insurance program for low-income adults and children, will cover the treatments in full until at least early 2024.

HHS officials could set aside any leftover taxpayer-funded medication for people who can’t afford to pay the full cost, but they haven’t shared any concrete plans to do so. The government purchased 20 million courses of Paxlovid and 3 million of Lagevrio. Fewer than a third have been used, and usage has fallen in recent months, according to KHN’s analysis of the data from HHS.

Sixty percent of the government’s supply of Evusheld is also still available, although the COVID prevention therapy is less effective against new strains of the virus. The health department in one state, New Mexico, has recommended against using it.

HHS did not make officials available for an interview or answer written questions about the commercialization plans.

The government created a potential workaround when they moved bebtelovimab, another COVID treatment, to the private market this summer. It now retails for $2,100 per patient. The agency set aside the remaining 60,000 government-purchased doses that hospitals could use to treat uninsured patients in a convoluted dose-replacement process. But it’s hard to tell how well that setup would work for Paxlovid: Bebtelovimab was already much less popular, and the FDA halted its use on Nov. 30 because it’s less effective against current strains of the virus.

Federal officials and insurance companies would have good reason to make sure patients can continue to afford COVID drugs: They’re far cheaper than if patients land in the emergency room.

“The medications are so worthwhile,” said Dr. Madoff, the Massachusetts health official. “They’re not expensive in the grand scheme of health care costs.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Everyone wins when losers get paid

Bribery really is the solution to all of life’s problems

Breaking news: The United States has a bit of an obesity epidemic. Okay, maybe not so breaking news. But it’s a problem we’ve been struggling with for a very long time. Part of the issue is that there really is no secret to weight loss. Pretty much anything can work if you’re committed. The millions of diets floating around are testament to this idea.

The problem of losing weight is amplified if you don’t rake in the big bucks. Lower-income individuals often can’t afford healthy superfoods, and they’re often too busy to spend time at classes, exercising, or following programs. A group of researchers at New York University has offered up an alternate solution to encourage weight loss in low-income people: Pay them.

Specifically, pay them for losing weight. A reward, if you will. The researchers recruited several hundred lower-income people and split them into three groups. All participants received a free 1-year membership to a gym and weight-loss program, as well as food journals and fitness devices, but one group received payment (on average, about $300 overall) for attending meetings, exercising a certain amount every week, or weighing themselves twice a week. About 40% of people in this group lost 5% of their body weight after 6 months, twice as many as in the group that did not receive payment for performing these tasks.

The big winners, however, were those in the third group. They also received the free stuff, but the researchers offered them a more simple and direct bribe: Lose 5% of your weight over 6 months and we’ll pay you. The reward? About $450 on average, and it worked very well, with half this group losing the weight after 6 months. That said, after a year something like a fifth of this group put the weight back on, bringing them in line with the group that was paid to perform tasks. Still, both groups outperformed the control group, which received no money.

The takeaway from this research is pretty obvious. Pay people a fair price to do something, and they’ll do it. This is a lesson that has absolutely no relevance in the modern world. Nope, none whatsoever. We all receive completely fair wages. We all have plenty of money to pay for things. Everything is fine.

More green space, less medicine

Have you heard of the 3-30-300 rule? Proposed by urban forester Cecil Konijnendijk, it’s become the rule of thumb for urban planners and other foresters into getting more green space in populated areas. A recent study has found that people who lived within this 3-30-300 rule had better mental health and less medication use.

If you’re not an urban forester, however, you may not know what the 3-30-300 rule is. But it’s pretty simple, people should be able to see at least three trees from their home, have 30% tree canopy in their neighborhood, and have 300 Spartans to defend against the Persian army.

We may have made that last one up. It’s actually have a green space or park within 300 meters of your home.

In the new study, only 4.7% of people surveyed lived in an area that followed all three rules. About 62% of the surveyed lived with a green space at least 300 meters away, 43% had at least three trees within 15 meters from their home, and a rather pitiful 9% had adequate tree canopy coverage in their neighborhood.

Greater adherence to the 3-30-300 rule was associated with fewer visits to the psychologist, with 8.3% of the participants reporting a psychologist visit in the last year. The data come from a sample of a little over 3,000 Barcelona residents aged 15-97 who were randomly selected to participate in the Barcelona Public Health Agency Survey.

“There is an urgent need to provide citizens with more green space,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, lead author of the study. “We may need to tear out asphalt and plant more trees, which would not only improve health, but also reduce heat island effects and contribute to carbon capture.”

The main goal and message is that more green space is good for everyone. So if you’re feeling a little overwhelmed, take a breather and sit somewhere green. Or call those 300 Spartans and get them to start knocking some buildings down.

Said the toilet to the engineer: Do you hear what I hear?

A mythical hero’s journey took Dorothy along the yellow brick road to find the Wizard of Oz. Huckleberry Finn used a raft to float down the Mississippi River. Luke Skywalker did most of his traveling between planets. For the rest of us, the journey may be just a bit shorter.

Also a bit less heroic. Unless, of course, you’re prepping for a colonoscopy. Yup, we’re headed to the toilet, but not just any toilet. This toilet was the subject of a presentation at the annual meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, titled “The feces thesis: Using machine learning to detect diarrhea,” and that presentation was the hero’s journey of Maia Gatlin, PhD, a research engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

She and her team attached a noninvasive microphone sensor to a toilet, and now they can identify bowel diseases without collecting any identifiable information.

The audio sample of an excretion event is “transformed into a spectrogram, which essentially captures the sound in an image. Different events produce different features in the audio and the spectrogram. For example, urination creates a consistent tone, while defecation may have a singular tone. In contrast, diarrhea is more random,” they explained in the written statement.

They used a machine learning algorithm to classify each spectrogram based on its features. “The algorithm’s performance was tested against data with and without background noises to make sure it was learning the right sound features, regardless of the sensor’s environment,” Dr. Gatlin and associates wrote.

Their goal is to use the toilet sensor in areas where cholera is common to prevent the spread of disease. After that, who knows? “Perhaps someday, our algorithm can be used with existing in-home smart devices to monitor one’s own bowel movements and health!” she suggested.

That would be a heroic toilet indeed.

Bribery really is the solution to all of life’s problems

Breaking news: The United States has a bit of an obesity epidemic. Okay, maybe not so breaking news. But it’s a problem we’ve been struggling with for a very long time. Part of the issue is that there really is no secret to weight loss. Pretty much anything can work if you’re committed. The millions of diets floating around are testament to this idea.

The problem of losing weight is amplified if you don’t rake in the big bucks. Lower-income individuals often can’t afford healthy superfoods, and they’re often too busy to spend time at classes, exercising, or following programs. A group of researchers at New York University has offered up an alternate solution to encourage weight loss in low-income people: Pay them.

Specifically, pay them for losing weight. A reward, if you will. The researchers recruited several hundred lower-income people and split them into three groups. All participants received a free 1-year membership to a gym and weight-loss program, as well as food journals and fitness devices, but one group received payment (on average, about $300 overall) for attending meetings, exercising a certain amount every week, or weighing themselves twice a week. About 40% of people in this group lost 5% of their body weight after 6 months, twice as many as in the group that did not receive payment for performing these tasks.

The big winners, however, were those in the third group. They also received the free stuff, but the researchers offered them a more simple and direct bribe: Lose 5% of your weight over 6 months and we’ll pay you. The reward? About $450 on average, and it worked very well, with half this group losing the weight after 6 months. That said, after a year something like a fifth of this group put the weight back on, bringing them in line with the group that was paid to perform tasks. Still, both groups outperformed the control group, which received no money.

The takeaway from this research is pretty obvious. Pay people a fair price to do something, and they’ll do it. This is a lesson that has absolutely no relevance in the modern world. Nope, none whatsoever. We all receive completely fair wages. We all have plenty of money to pay for things. Everything is fine.

More green space, less medicine

Have you heard of the 3-30-300 rule? Proposed by urban forester Cecil Konijnendijk, it’s become the rule of thumb for urban planners and other foresters into getting more green space in populated areas. A recent study has found that people who lived within this 3-30-300 rule had better mental health and less medication use.

If you’re not an urban forester, however, you may not know what the 3-30-300 rule is. But it’s pretty simple, people should be able to see at least three trees from their home, have 30% tree canopy in their neighborhood, and have 300 Spartans to defend against the Persian army.

We may have made that last one up. It’s actually have a green space or park within 300 meters of your home.

In the new study, only 4.7% of people surveyed lived in an area that followed all three rules. About 62% of the surveyed lived with a green space at least 300 meters away, 43% had at least three trees within 15 meters from their home, and a rather pitiful 9% had adequate tree canopy coverage in their neighborhood.

Greater adherence to the 3-30-300 rule was associated with fewer visits to the psychologist, with 8.3% of the participants reporting a psychologist visit in the last year. The data come from a sample of a little over 3,000 Barcelona residents aged 15-97 who were randomly selected to participate in the Barcelona Public Health Agency Survey.

“There is an urgent need to provide citizens with more green space,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, lead author of the study. “We may need to tear out asphalt and plant more trees, which would not only improve health, but also reduce heat island effects and contribute to carbon capture.”

The main goal and message is that more green space is good for everyone. So if you’re feeling a little overwhelmed, take a breather and sit somewhere green. Or call those 300 Spartans and get them to start knocking some buildings down.

Said the toilet to the engineer: Do you hear what I hear?

A mythical hero’s journey took Dorothy along the yellow brick road to find the Wizard of Oz. Huckleberry Finn used a raft to float down the Mississippi River. Luke Skywalker did most of his traveling between planets. For the rest of us, the journey may be just a bit shorter.

Also a bit less heroic. Unless, of course, you’re prepping for a colonoscopy. Yup, we’re headed to the toilet, but not just any toilet. This toilet was the subject of a presentation at the annual meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, titled “The feces thesis: Using machine learning to detect diarrhea,” and that presentation was the hero’s journey of Maia Gatlin, PhD, a research engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

She and her team attached a noninvasive microphone sensor to a toilet, and now they can identify bowel diseases without collecting any identifiable information.

The audio sample of an excretion event is “transformed into a spectrogram, which essentially captures the sound in an image. Different events produce different features in the audio and the spectrogram. For example, urination creates a consistent tone, while defecation may have a singular tone. In contrast, diarrhea is more random,” they explained in the written statement.

They used a machine learning algorithm to classify each spectrogram based on its features. “The algorithm’s performance was tested against data with and without background noises to make sure it was learning the right sound features, regardless of the sensor’s environment,” Dr. Gatlin and associates wrote.

Their goal is to use the toilet sensor in areas where cholera is common to prevent the spread of disease. After that, who knows? “Perhaps someday, our algorithm can be used with existing in-home smart devices to monitor one’s own bowel movements and health!” she suggested.

That would be a heroic toilet indeed.

Bribery really is the solution to all of life’s problems

Breaking news: The United States has a bit of an obesity epidemic. Okay, maybe not so breaking news. But it’s a problem we’ve been struggling with for a very long time. Part of the issue is that there really is no secret to weight loss. Pretty much anything can work if you’re committed. The millions of diets floating around are testament to this idea.

The problem of losing weight is amplified if you don’t rake in the big bucks. Lower-income individuals often can’t afford healthy superfoods, and they’re often too busy to spend time at classes, exercising, or following programs. A group of researchers at New York University has offered up an alternate solution to encourage weight loss in low-income people: Pay them.

Specifically, pay them for losing weight. A reward, if you will. The researchers recruited several hundred lower-income people and split them into three groups. All participants received a free 1-year membership to a gym and weight-loss program, as well as food journals and fitness devices, but one group received payment (on average, about $300 overall) for attending meetings, exercising a certain amount every week, or weighing themselves twice a week. About 40% of people in this group lost 5% of their body weight after 6 months, twice as many as in the group that did not receive payment for performing these tasks.

The big winners, however, were those in the third group. They also received the free stuff, but the researchers offered them a more simple and direct bribe: Lose 5% of your weight over 6 months and we’ll pay you. The reward? About $450 on average, and it worked very well, with half this group losing the weight after 6 months. That said, after a year something like a fifth of this group put the weight back on, bringing them in line with the group that was paid to perform tasks. Still, both groups outperformed the control group, which received no money.

The takeaway from this research is pretty obvious. Pay people a fair price to do something, and they’ll do it. This is a lesson that has absolutely no relevance in the modern world. Nope, none whatsoever. We all receive completely fair wages. We all have plenty of money to pay for things. Everything is fine.

More green space, less medicine

Have you heard of the 3-30-300 rule? Proposed by urban forester Cecil Konijnendijk, it’s become the rule of thumb for urban planners and other foresters into getting more green space in populated areas. A recent study has found that people who lived within this 3-30-300 rule had better mental health and less medication use.

If you’re not an urban forester, however, you may not know what the 3-30-300 rule is. But it’s pretty simple, people should be able to see at least three trees from their home, have 30% tree canopy in their neighborhood, and have 300 Spartans to defend against the Persian army.

We may have made that last one up. It’s actually have a green space or park within 300 meters of your home.

In the new study, only 4.7% of people surveyed lived in an area that followed all three rules. About 62% of the surveyed lived with a green space at least 300 meters away, 43% had at least three trees within 15 meters from their home, and a rather pitiful 9% had adequate tree canopy coverage in their neighborhood.

Greater adherence to the 3-30-300 rule was associated with fewer visits to the psychologist, with 8.3% of the participants reporting a psychologist visit in the last year. The data come from a sample of a little over 3,000 Barcelona residents aged 15-97 who were randomly selected to participate in the Barcelona Public Health Agency Survey.

“There is an urgent need to provide citizens with more green space,” said Mark Nieuwenhuijsen, lead author of the study. “We may need to tear out asphalt and plant more trees, which would not only improve health, but also reduce heat island effects and contribute to carbon capture.”

The main goal and message is that more green space is good for everyone. So if you’re feeling a little overwhelmed, take a breather and sit somewhere green. Or call those 300 Spartans and get them to start knocking some buildings down.

Said the toilet to the engineer: Do you hear what I hear?

A mythical hero’s journey took Dorothy along the yellow brick road to find the Wizard of Oz. Huckleberry Finn used a raft to float down the Mississippi River. Luke Skywalker did most of his traveling between planets. For the rest of us, the journey may be just a bit shorter.

Also a bit less heroic. Unless, of course, you’re prepping for a colonoscopy. Yup, we’re headed to the toilet, but not just any toilet. This toilet was the subject of a presentation at the annual meeting of the Acoustical Society of America, titled “The feces thesis: Using machine learning to detect diarrhea,” and that presentation was the hero’s journey of Maia Gatlin, PhD, a research engineer at the Georgia Institute of Technology.

She and her team attached a noninvasive microphone sensor to a toilet, and now they can identify bowel diseases without collecting any identifiable information.

The audio sample of an excretion event is “transformed into a spectrogram, which essentially captures the sound in an image. Different events produce different features in the audio and the spectrogram. For example, urination creates a consistent tone, while defecation may have a singular tone. In contrast, diarrhea is more random,” they explained in the written statement.

They used a machine learning algorithm to classify each spectrogram based on its features. “The algorithm’s performance was tested against data with and without background noises to make sure it was learning the right sound features, regardless of the sensor’s environment,” Dr. Gatlin and associates wrote.

Their goal is to use the toilet sensor in areas where cholera is common to prevent the spread of disease. After that, who knows? “Perhaps someday, our algorithm can be used with existing in-home smart devices to monitor one’s own bowel movements and health!” she suggested.

That would be a heroic toilet indeed.

Fungi that cause lung infections now found in most states: Study

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Soil-dwelling fungi that can cause lung infections are more widespread than most doctors thought, sometimes leading to missed diagnoses, according to a new study.

Researchers studying fungi-linked lung infections realized that many infections were occurring in places the fungi weren’t thought to exist. They found that maps doctors use to know if the fungi are a threat in their area hadn’t been updated in half a century.

University of California, Davis infectious disease professor George Thompson, MD, said in a commentary published along with the study.

Published in the journal Clinical Infectious Diseases, the study sought to identify illnesses linked to three types of soil fungi in the United States that are known to cause lung infections. They are called histoplasma, blastomyces, and coccidioides, the latter of which causes an illness known as Valley fever, which has been on the rise in California.

Researchers used data for more than 45 million people who use Medicare and found that at least 1 of these 3 fungi are present in 48 of 50 U.S. states and Washington, D.C.

Symptoms after breathing in the fungi spores include fever and cough and can be similar to symptoms of other illnesses, according to the Centers for Disease Control.

The researchers said health care providers need to increase their suspicion for these fungi, which “would likely result in fewer missed diagnoses, fewer diagnostic delays, and improved patient outcomes.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

FROM CLINICAL INFECTIOUS DISEASE

Ohio measles outbreak sickens nearly 60 children

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

None of the children had been fully vaccinated against measles, and 23 of them have been hospitalized, local officials report.

“Measles can be very serious, especially for children under age 5,” Columbus Public Health spokesperson Kelli Newman told CNN.

Nearly all of the infected children are under age 5, with 12 of them being under 1 year old.

“Many children are hospitalized for dehydration,” Ms. Newman told CNN in an email. “Other serious complications also can include pneumonia and neurological conditions such as encephalitis. There’s no way of knowing which children will become so sick they have to be hospitalized. The safest way to protect children from measles is to make sure they are vaccinated with MMR.”

Of the 59 infected children, 56 were unvaccinated and three had been partially vaccinated. The MMR (measles, mumps, and rubella) vaccine is recommended for children beginning at 12 months old, according to the Centers for Disease Control and American Academy of Pediatrics. Two doses are needed to be considered fully vaccinated, and the second dose is usually given between 4 and 6 years old.

Measles “is one of the most infectious agents known to man,” the academy says.

It is so contagious that if one person has it, up to 9 out of 10 people around that person will also become infected if they are not protected, the CDC explains. Measles infection causes a rash and a fever that can spike beyond 104° F. Sometimes, the illness can lead to brain swelling, brain damage, or death.

Last month, the World Health Organization and CDC warned that 40 million children worldwide missed their measles vaccinations in 2021, partly due to pandemic disruptions. The American Academy of Pediatrics also notes that many parents choose not to vaccinate their children due to misinformation.

Infants are at heightened risk because they are too young to be vaccinated.

The academy offered several tips for protecting unvaccinated infants during a measles outbreak:

- Limit your baby’s exposure to crowds, other children, and people with cold symptoms.

- Disinfect objects and surfaces at home regularly, because the measles virus can live on surfaces or suspended in the air for 2 hours.

- If possible, feed your baby breast milk, because it has antibodies to prevent and fight infections.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Vaccination cuts long COVID risk for rheumatic disease patients

Patients with rheumatic disease are at least half as likely to develop long COVID after a SARS-CoV-2 infection if they have been fully vaccinated against COVID-19, according to research published in Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases (2022 Nov 28. doi: 10.1136/ard-2022-223439).

“Moreover, those who were vaccinated prior to getting COVID-19 had less pain and fatigue after their infection,” Zachary S. Wallace, MD, MSc, an assistant professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School, Boston, and a study author, said in an interview. “These findings reinforce the importance of vaccination in this population.”

Messaging around the value of COVID vaccination has been confusing for some with rheumatic disease “because our concern regarding a blunted response to vaccination has led many patients to think that they do not provide much benefit if they are on immunosuppression,” Dr. Wallace said. “In our cohort, which included many patients on immunosuppression of varying degrees, being vaccinated was quite beneficial.”

Leonard H. Calabrese, DO, director of the R.J. Fasenmyer Center for Clinical Immunology and a professor of medicine at the Cleveland Clinic, said in an interview that the study is an “extremely important contribution to our understanding of COVID-19 and its pattern of recovery in patients with immune-mediated inflammatory diseases [IMIDs].” Remaining unanswered questions are “whether patients with IMIDs develop more frequent PASC [post–acute sequelae of COVID-19] from COVID-19 and, if so, is it milder or more severe, and does it differ in its clinical phenotype?”

Long COVID risk assessed at 4 weeks and 3 months after infection

The researchers prospectively tracked 280 adult patients in the Mass General Brigham health care system in the greater Boston area who had systemic autoimmune rheumatic diseases and had an acute COVID-19 infection between March 2020 and July 2022. Patients were an average 53 years old, and most were White (82%) and female (80%). More than half (59%) had inflammatory arthritis, a quarter (24%) had connective tissue disease, and most others had a vasculitis condition or multiple conditions.

A total of 11% of patients were unvaccinated, 28% were partially vaccinated with one mRNA COVID-19 vaccine dose, and 41% were fully vaccinated with two mRNA vaccine doses or one Johnson & Johnson dose. The 116 fully vaccinated patients were considered to have a breakthrough infection while the other 164 were considered to have a nonbreakthrough infection. The breakthrough and nonbreakthrough groups were similar in terms of age, sex, race, ethnicity, smoking status, and type of rheumatic disease. Comorbidities were also similar, except obesity, which was more common in the non–breakthrough infection group (25%) than the breakthrough infection group (10%).

The researchers queried patients on their COVID-19 symptoms, how long symptoms lasted, treatments they received, and hospitalization details. COVID-19 symptoms assessed included fever, sore throat, new cough, nasal congestion/rhinorrhea, dyspnea, chest pain, rash, myalgia, fatigue/malaise, headache, nausea/vomiting, diarrhea, anosmia, dysgeusia, and joint pain.

Patients completed surveys about symptoms at 4 weeks and 3 months after infection. Long COVID, or PASC, was defined as any persistent symptom at the times assessed.

Vaccinated patients fared better across outcomes

At 4 weeks after infection, 41% of fully vaccinated patients had at least one persistent symptom, compared with 54% of unvaccinated or partially vaccinated patients (P = .04). At 3 months after infection, 21% of fully vaccinated patients had at least one persistent symptom, compared with 41% of unvaccinated or partially vaccinated patients (P < .0001).

Vaccinated patients were half as likely to have long COVID at 4 weeks after infection (adjusted odds ratio, 0.49) and 90% less likely to have long COVID 3 months after infection (aOR, 0.1), after adjustment for age, sex, race, comorbidities, and use of any of four immune-suppressing medications (anti-CD20 monoclonal antibodies, methotrexate, mycophenolate, or glucocorticoids).

Fully vaccinated patients with breakthrough infections had an average 21 additional days without symptoms during follow-up, compared with unvaccinated and partially vaccinated patients (P = .04).