User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

COVID-19 mortality in hospitalized HF patients: Nearly 1 in 4

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Patients with heart failure who are infected with SARS-CoV-2 are at high risk for complications, with nearly 1 in 4 dying during hospitalization, according to a large database analysis that included more than 8,000 patients who had heart failure and COVID-19.

In-hospital mortality was 24.2% for patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized with COVID-19, as compared with 14.2% for individuals without heart failure who were hospitalized with COVID-19.

For perspective, the researchers compared the patients with heart failure and COVID-19 with patients who had a history of heart failure and were hospitalized for an acute worsening episode: the risk for death was about 10-fold higher with COVID-19.

“These patients really face remarkably high risk, and when we compare that to the risk of in-hospital death with something we are a lot more familiar with – acute heart failure – we see that the risk was about 10-fold greater,” said first author Ankeet S. Bhatt, MD, MBA, from Brigham and Women’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, both in Boston.

In an article published online in JACC Heart Failure on Dec. 28, a group led by Dr. Bhatt and senior author Scott D. Solomon, MD, reported an analysis of administrative data on a total of 2,041,855 incident hospitalizations logged in the Premier Healthcare Database between April 1, 2020, and Sept. 30, 2020.

The Premier Healthcare Database comprises data from more than 1 billion patient encounters, which equates to approximately 1 in every 5 of all inpatient discharges in the United States.

Of 132,312 hospitalizations of patients with a history of heart failure, 23,843 (18.0%) were hospitalized with acute heart failure, 8,383 patients (6.4%) were hospitalized with COVID-19, and 100,068 (75.6%) were hospitalized for other reasons.

Outcomes and resource utilization were compared with 141,895 COVID-19 hospitalizations of patients who did not have heart failure.

Patients were deemed to have a history of heart failure if they were hospitalized at least once for heart failure from Jan. 1, 2019, to March 21, 2020, or had at least two heart failure outpatient visits during that period.

In a comment, Dr. Solomon noted some of the pros and cons of the data used in this study.

“Premier is a huge database, encompassing about one-quarter of all the health care facilities in the United States and one-fifth of all inpatient visits, so for that reason we’re able to look at things that are very difficult to look at in smaller hospital systems, but the data are also limited in that you don’t have as much granular detail as you might in smaller datasets,” said Dr. Solomon.

“One thing to recognize is that our data start at the point of hospital admission, so were looking only at individuals who have crossed the threshold in terms of their illness and been admitted,” he added.

Use of in-hospital resources was significantly greater for patients with heart failure hospitalized for COVID-19, compared with patients hospitalized for acute heart failure or for other reasons. This included “multifold” higher rates of ICU care (29% vs. 15%), mechanical ventilation (17% vs. 6%), and central venous catheter insertion (19% vs. 7%; P < .001 for all).

The proportion of patients who required mechanical ventilation and care in the ICU in the group with COVID-19 but who did not have no heart failure was similar to those who had both conditions.

The greater odds of in-hospital mortality among patients with both heart failure and COVID-19, compared with individuals with heart failure hospitalized for other reasons, was strongest in April, with an adjusted odds ratio of 14.48, compared with subsequent months (adjusted OR for May-September, 10.11; P for interaction < .001).

“We’re obviously not able to say with certainty what was happening in April, but I think that maybe the patients who were most vulnerable to COVID-19 may be more represented in that population, so the patients with comorbidities or who are immunosuppressed or otherwise,” said Dr. Bhatt in an interview.

“The other thing we think is that there may be a learning curve in terms of how to care for patients with acute severe respiratory illness. That includes increased institutional knowledge – like the use of prone ventilation – but also therapies that were subsequently shown to have benefit in randomized clinical trials, such as dexamethasone,” he added.

“These results should remind us to be innovative and thoughtful in our management of patients with heart failure while trying to maintain equity and good health for all,” wrote Nasrien E. Ibrahim, MD, from Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston; Ersilia DeFillipis, MD, Columbia University, New York; and Mitchel Psotka, MD, PhD, Innova Heart and Vascular Institute, Falls Church, Va., in an editorial accompanying the study.

The data emphasize the importance of ensuring equal access to services such as telemedicine, virtual visits, home nursing visits, and remote monitoring, they noted.

“As the COVID-19 pandemic rages on and disproportionately ravages socioeconomically disadvantaged communities, we should focus our efforts on strategies that minimize these inequities,” the editorialists wrote.

Dr. Solomon noted that, although Black and Hispanic patients were overrepresented in the population of heart failure patients hospitalized with COVID-19, once in the hospital, race was not a predictor of in-hospital mortality or the need for mechanical ventilation.

Dr. Bhatt has received speaker fees from Sanofi Pasteur and is supported by a National Institutes of Health/National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute postdoctoral training grant. Dr. Solomon has received grant support and/or speaking fees from a number of companies and from the NIH/NHLBI. The editorialists disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

NETs a possible therapeutic target for COVID-19 thrombosis?

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Researchers in Madrid may have found a clue to the pathogenesis of ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) in patients with COVID-19; it might also offer a therapeutic target to counter the hypercoagulability seen with COVID-19.

In a case series of five patients with COVID-19 who had an STEMI, neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) were detected in coronary thrombi of all five patients. The median density was 66%, which is significantly higher than that seen in a historical series of patients with STEMI. In that series, NETs were found in only two-thirds of patients; in that series, the median density was 19%.

In the patients with COVID-19 and STEMI and in the patients reported in the prepandemic historical series from 2015, intracoronary aspirates were obtained during percutaneous coronary intervention using a thrombus aspiration device.

Histologically, findings in the patients from 2015 differed from those of patients with COVID-19. In the patients with COVID, thrombi were composed mostly of fibrin and polymorphonuclear cells. None showed fragments of atherosclerotic plaque or iron deposits indicative of previous episodes of plaque rupture. In contrast, 65% of thrombi from the 2015 series contained plaque fragments.

Ana Blasco, MD, PhD, Hospital Universitario Puerta de Hierro-Majadahonda, Madrid, and colleagues report their findings in an article published online Dec. 29 in JAMA Cardiology.

Commenting on the findings in an interview, Irene Lang, MD, from the Medical University of Vienna said, “This is really a very small series, purely observational, and suffering from the problem that acute STEMI is uncommon in COVID-19, but it does serve to demonstrate once more the abundance of NETs in acute myocardial infarction.”

“NETs are very much at the cutting edge of thrombosis research, and NET formation provides yet another link between inflammation and clot formation,” added Peter Libby, MD, from Harvard Medical School and Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston.

“Multiple observations have shown thrombosis of arteries large and small, microvessels, and veins in COVID-19. The observations of Blasco et al. add to the growing literature about NETs as contributors to the havoc wrought in multiple organs in advanced COVID-19,” he added in an email exchange with this news organization.

Neither Dr. Lang nor Dr. Libby were involved in this research; both have been actively studying NETs and their contribution to cardiothrombotic disease in recent years.

NETs are newly recognized contributors to venous and arterial thrombosis. These weblike DNA strands are extruded by activated or dying neutrophils and have protein mediators that ensnare pathogens while minimizing damage to the host cell.

First described in 2004, exaggerated NET formation has also been linked to the initiation and accretion of inflammation and thrombosis.

“NETs thus furnish a previously unsuspected link between inflammation, innate immunity, thrombosis, oxidative stress, and cardiovascular diseases,” Dr. Libby and his coauthors wrote in an article on the topic published in Circulation Research earlier this year.

Limiting NET formation or “dissolving” existing NETs could provide a therapeutic avenue not just for patients with COVID-19 but for all patients with thrombotic disease.

“The concept of NETs as a therapeutic target is appealing, in and out of COVID times,” said Dr. Lang.

“I personally believe that the work helps to raise awareness for the potential use of deoxyribonuclease (DNase), an enzyme that acts to clear NETs by dissolving the DNA strands, in the acute treatment of STEMI. Rapid injection of engineered recombinant DNases could potentially wipe away coronary obstructions, ideally before they may cause damage to the myocardium,” she added.

Dr. Blasco and colleagues and Dr. Lang have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Libby is an unpaid consultant or member of the advisory board for a number of companies.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

COVID-19 vaccine rollout faces delays

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

If the current pace of vaccination continues, “it’s going to take years, not months, to vaccinate the American people,” President-elect Joe Biden said during a briefing Dec. 29.

In fact, at the current rate, it would take nearly 10 years to vaccinate enough Americans to bring the pandemic under control, according to NBC News. To reach 80% of the country by late June, 3 million people would need to receive a COVID-19 vaccine each day.

“As I long feared and warned, the effort to distribute and administer the vaccine is not progressing as it should,” Mr. Biden said, reemphasizing his pledge to get 100 million doses to Americans during his first 100 days as president.

So far, 11.4 million doses have been distributed and 2.1 million people have received a vaccine, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Most states have administered a fraction of the doses they’ve received, according to data compiled by The New York Times.

Federal officials have said there’s an “expected lag” between delivery of doses, shots going into arms, and the data being reported to the CDC, according to CNN. The Food and Drug Administration must assess each shipment for quality control, which has slowed down distribution, and the CDC data are just now beginning to include the Moderna vaccine, which the FDA authorized for emergency use on Dec. 18.

The 2.1 million number is “an underestimate,” Brett Giroir, MD, the assistant secretary of the U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, told NBC News Dec. 29. At the same time, the U.S. won’t meet the goal of vaccinating 20 million people in the next few days, he said.

Another 30 million doses will go out in January, Dr. Giroir said, followed by 50 million in February.

Some vaccine experts have said they’re not surprised by the speed of vaccine distribution.

“It had to go this way,” Paul Offit, MD, a professor of pediatrics at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told STAT. “We had to trip and fall and stumble and figure this out.”

To speed up distribution in 2021, the federal government will need to help states, Mr. Biden said Dec. 29. He plans to use the Defense Authorization Act to ramp up production of vaccine supplies. Even still, the process will take months, he said.

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com .

Anorexia and diarrhea top list of GI symptoms in COVID-19 patients

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

Patients with severe COVID-19 were significantly more likely than those with milder cases to have GI symptoms of anorexia and diarrhea, as well as abnormal liver function, based on data from a meta-analysis of more than 4,500 patients.

Previous studies have shown that liver damage “was more likely to be observed in severe patients during the process of disease,” and other studies have shown varying degrees of liver insufficiency in COVID-19 patients, but gastrointestinal symptoms have not been well studied, wrote Zi-yuan Dong, MD, of China Medical University, Shenyang City, and colleagues.

In a study published in the Journal of Clinical Gastroenterology, the researchers identified 31 studies including 4,682 COVID-19 patients. Case collection was from Dec. 11, 2019, to Feb. 28, 2020. Median age among studies ranged from 36 to 62 years, and 55% of patients were male.

A total of 26 studies were analyzed for the prevalence of GI symptoms, specifically nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, abdominal pain, and anorexia. Of these, anorexia and diarrhea were significantly more common in COVID-19 patients, with prevalence of 17% and 8% respectively, (P < .0001 for both).

In addition, 14 of the studies included in the analysis assessed the prevalence of abnormal liver function based on increased levels of aspartate aminotransferase, alanine aminotransferase, and total bilirubin. Of these, increased alanine aminotransferase was the most common, occurring in 25% of patients, compared with increased AST (in 24%) and total bilirubin (in 13%).

When assessed by disease severity, patients with severe disease and those in the ICU were significantly more likely than general/non-ICU patients to have anorexia (odds ratio, 2.19), diarrhea (OR, 1.65), and abdominal pain (OR, 6.38). The severely ill patients were significantly more likely to have increased AST and ALT (OR, 2.98 and 2.66, respectively).

“However, there were no significant differences between severe/ICU group and general/non-ICU group for the prevalence of nausea and vomiting and liver disease,” the researchers said.

The study findings were limited by several factors including the unclear classification of digestive system disease and liver disease in many of the studies, the small sample sizes, and the lack of data on pathology of the liver or colon in COVID-19 patients, the researchers noted.

More research is needed, but the findings suggest that COVID-19 could contribute to liver damage because the most significant abnormal liver function was increased ALT, they said.

Check liver function in cases with GI symptoms

“COVID patients can present asymptomatically or with nonspecific symptoms, including GI symptoms,” said Ziad F. Gellad, MD, of Duke University Medical Center, Durham, N.C., in an interview. “While the focus of management naturally is directed to the pulmonary consequences of the disease, it is important to evaluate the patient holistically,” he said.

“I do not think these findings have profound clinical implications because they identify relatively nonspecific symptoms that are commonly seen in patients in a number of other conditions,” noted Dr. Gellad. “The management of COVID should not change, with the exception of perhaps making sure to check for abnormal liver function tests in patients that present with more typical COVID symptoms,” he said.

“Additional research is needed to understand the biologic mechanism by which COVID impacts systems outside of the lungs,” Dr. Gellad emphasized. “For example, there has been some very interesting work understanding the impact of COVID on the pancreas and risk for pancreatitis. That work is similarly needed to understand how COVID, outside of causing a general illness, specifically impacts the rest of the GI tract,” he said.

The study was supported by the Liaoning Science and Technology Foundation. The researchers had no financial conflicts to disclose. Dr. Gellad had no financial conflicts to disclose.

SOURCE: Dong Z-Y et al. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2021 Jan. doi: 10.1097/MCG.0000000000001424.

FROM THE JOURNAL OF CLINICAL GASTROENTEROLOGY

Complete blood count scoring can predict COVID-19 severity

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

A scoring system based on 10 parameters in a complete blood count with differential within 3 days of hospital presentation predict those with COVID-19 who are most likely to progress to critical illness, new evidence shows.

Advantages include prognosis based on a common and inexpensive clinical measure, as well as automatic generation of the score along with CBC results, noted investigators in the observational study conducted throughout 11 European hospitals.

“COVID-19 comes along with specific alterations in circulating blood cells that can be detected by a routine hematology analyzer, especially when that hematology analyzer is also capable to recognize activated immune cells and early circulating blood cells, such as erythroblast and immature granulocytes,” senior author Andre van der Ven, MD, PhD, infectious diseases specialist and professor of international health at Radboud University Medical Center’s Center for Infectious Diseases in Nijmegen, the Netherlands, said in an interview.

Furthermore, Dr. van der Ven said, “these specific changes are also seen in the early course of COVID-19 disease, and more in those that will develop serious disease compared to those with mild disease.”

The study was published online Dec. 21 in the journal eLife.

The study is “almost instinctively correct. It’s basically what clinicians do informally with complete blood count … looking at a combination of results to get the gestalt of what patients are going through,” Samuel Reichberg, MD, PhD, associate medical director of the Northwell Health Core Laboratory in Lake Success, N.Y., said in an interview.

“This is something that begs to be done for COVID-19. I’m surprised no one has done this before,” he added.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues created an algorithm based on 1,587 CBC assays from 923 adults. They also validated the scoring system in a second cohort of 217 CBC measurements in 202 people. The findings were concordant – the score accurately predicted the need for critical care within 14 days in 70.5% of the development cohort and 72% of the validation group.

The scoring system was superior to any of the 10 parameters alone. Over 14 days, the majority of those classified as noncritical within the first 3 days remained clinically stable, whereas the “clinical illness” group progressed. Clinical severity peaked on day 6.

Most previous COVID-19 prognosis research was geographically limited, carried a high risk for bias and/or did not validate the findings, Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues noted.

Early identification, early intervention

The aim of the score is “to assist with objective risk stratification to support patient management decision-making early on, and thus facilitate timely interventions, such as need for ICU or not, before symptoms of severe illness become clinically overt, with the intention to improve patient outcomes, and not to predict mortality,” the investigators noted.

Dr. Van der Ven and colleagues developed the score based on adults presenting from Feb. 21 to April 6, with outcomes followed until June 9. Median age of the 982 patients was 71 years and approximately two-thirds were men. They used a Sysmex Europe XN-1000 (Hamburg, Germany) hemocytometric analyzer in the study.

Only 7% of this cohort was not admitted to a hospital. Another 74% were admitted to a general ward and the remaining 19% were transferred directly to the ICU.

The scoring system includes parameters for neutrophils, monocytes, red blood cells and immature granulocytes, and when available, reticulocyte and iron bioavailability measures.

The researchers report significant differences over time in the neutrophil-to-lymphocyte ratio between the critical illness and noncritical groups (P < .001), for example. They also found significant differences in hemoglobin levels between cohorts after day 5.

The system generates a score from 0 to 28. Sensitivity for correctly predicting the need for critical care increased from 62% on day 1 to 93% on day 6.

A more objective assessment of risk

The study demonstrated that SARS-CoV-2 infection is characterized by hemocytometric changes over time. These changes, reflected together in the prognostic score, could aid in the early identification of patients whose clinical course is more likely to deteriorate over time.

The findings also support other work that shows men are more likely to present to the hospital with COVID-19, and that older age and presence of comorbidities add to overall risk. “However,” the researchers noted, “not all young patients had a mild course, and not all old patients with comorbidities were critical.”

Therefore, the prognostic score can help identify patients at risk for severe progression outside other risk factors and “support individualized treatment decisions with objective data,” they added.

Dr. Reichberg called the concept of combining CBC parameters into one score “very valuable.” However, he added that incorporating an index into clinical practice “has historically been tricky.”

The results “probably have to be replicated,” Dr. Reichberg said.

He added that it is likely a CBC-based score will be combined with other measures. “I would like to see an index that combines all the tests we do [for COVID-19], including complete blood count.”

Dr. Van der Ven shared the next step in his research. “The algorithm should be installed on the hematology analyzers so the prognostic score will be automatically generated if a full blood count is asked for in a COVID-19 patient,” he said. “So implementation of score is the main focus now.”

Dr. van der Ven disclosed an ad hoc consultancy agreement with Sysmex Europe. Sysmex Europe provided the reagents in the study free of charge; no other funders were involved. Dr. Reichberg has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

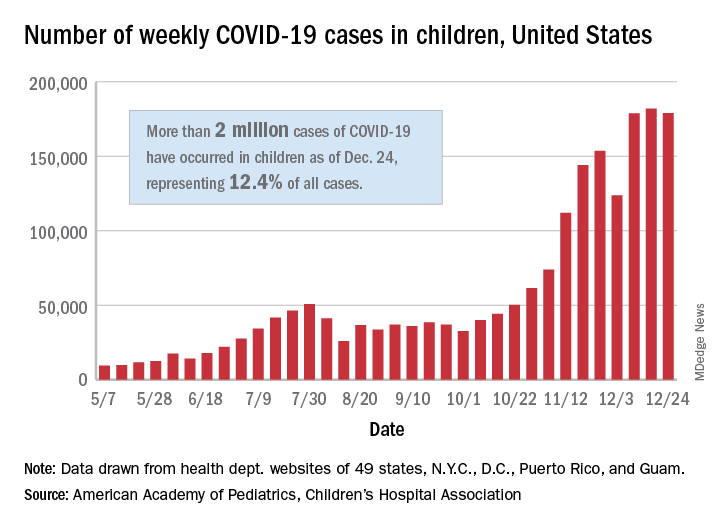

New pediatric cases down as U.S. tops 2 million children with COVID-19

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

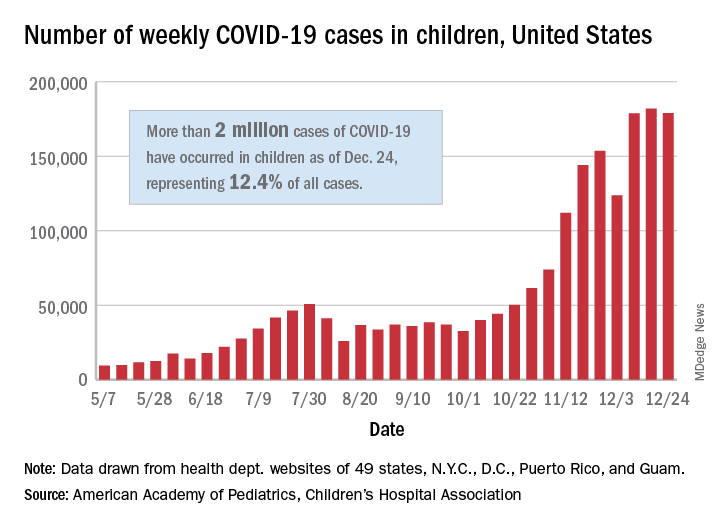

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

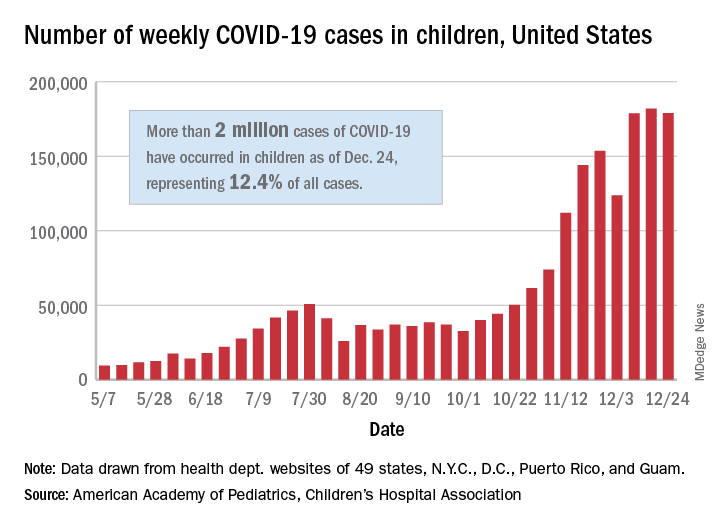

The United States exceeded 2 million reported cases of COVID-19 in children just 6 weeks after recording its 1 millionth case, according to a report from the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association.

The total number of cases in children was 2,000,681 as of Dec. 24, which represents 12.4% of all cases reported by the health departments of 49 states (excluding New York), the District of Columbia, New York City, Puerto Rico, and Guam, the AAP and CHA stated Dec. 29.

The case count for just the latest week, 178,935, was actually down 1.7% from the 182,018 reported the week before, marking the second drop since the beginning of December. The first came during the week ending Dec. 3, when the number of cases dropped more than 19% from the previous week, based on data from the AAP/CHA report.

The cumulative national rate of coronavirus infection is now 2,658 cases per 100,000 children, and “13 states have reported more than 4,000 cases per 100,000,” the two groups said.

The highest rate for any state can be found in North Dakota, which has had 7,722 cases of COVID-19 per 100,000 children. Wyoming has the highest proportion of cases in children at 20.5%, and California has reported the most cases overall, 234,174, the report shows.

Data on testing, hospitalization, and mortality were not included in the Dec. 29 report because of the holiday but will be available in the next edition, scheduled for release on Jan. 5, 2021.

2.1 Million COVID Vaccine Doses Given in U.S.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.

“We’ve made numerous attempts to get updated information, and when we get further word on its availability, we will immediately keep our members appraised of the new date and the method of distribution,” Paul DiGiacomo, president of the Detectives’ Endowment Association, wrote in a memo to members on Dec. 28.

“Every detective squad has been crushed with [COVID-19],” he told the newspaper. “Within the last couple of weeks, we’ve had at least two detectives hospitalized.”

President-elect Joe Biden will receive a briefing from his COVID-19 advisory team, provide a general update on the pandemic, and describe his own plan for vaccinating people quickly during an address Dec. 29, a transition official told Axios. Biden has pledged to administer 100 million vaccine doses in his first 100 days in office.

A version of this article originally appeared on WebMd.

The U.S. has distributed more than 11.4 million doses of the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines, and more than 2.1 million of those had been given to people as of December 28, according to the CDC.

The CDC’s COVID Data Tracker showed the updated numbers as of 9 a.m. on that day. The distribution total is based on the CDC’s Vaccine Tracking System, and the administered total is based on reports from state and local public health departments, as well as updates from five federal agencies: the Bureau of Prisons, Veterans Administration, Department of Defense, Department of State, and Indian Health Services.

Health care providers report to public health agencies up to 72 hours after the vaccine is given, and public health agencies report to the CDC after that, so there may be a lag in the data. The CDC’s numbers will be updated on Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.

“A large difference between the number of doses distributed and the number of doses administered is expected at this point in the COVID vaccination program due to several factors,” the CDC says.

Delays could occur due to the reporting of doses given, how states and local vaccine sites are managing vaccines, and the pending launch of vaccination through the federal Pharmacy Partnership for Long-Term Care Program.

“Numbers reported on other websites may differ from what is posted on CDC’s website because CDC’s overall numbers are validated through a data submission process with each jurisdiction,” the CDC says.

On Dec. 26, the agency’s tally showed that 9.5 million doses had been distributed and 1.9 million had been given, according to Reuters.

Public health officials and health care workers have begun to voice their concerns about the delay in giving the vaccines.

“We certainly are not at the numbers that we wanted to be at the end of December,” Anthony Fauci, MD, director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, told CNNDec. 29.

Operation Warp Speed had planned for 20 million people to be vaccinated by the end of the year. Fauci said he hopes that number will be achieved next month.

“I believe that as we get into January, we are going to see an increase in the momentum,” he said.

Shipment delays have affected other priority groups as well. The New York Police Department anticipated a rollout Dec. 29, but it’s now been delayed since the department hasn’t received enough Moderna doses to start giving the shots, according to the New York Daily News.