User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

COVID-19 mortality rates declined, but vary by hospital

Mortality rates for inpatients with COVID-19 dropped significantly during the first 6 months of the pandemic, but outcomes depend on the hospital where patients receive care, new data show.

“[T]he characteristic that is most associated with poor or worsening hospital outcomes is high or increasing community case rates,” write David A. Asch, MD, MBA, executive director of the Center for Health Care Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The relationship between COVID-19 mortality rates and local disease prevalence suggests that “hospitals do worse when they are burdened with cases and is consistent with imperatives to flatten the curve,” the authors continue. “As case rates of COVID-19 increase across the nation, hospital mortality outcomes may worsen.”

The researchers published their study online December 22 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The quick and substantial improvement in survival “is a tribute in part to new science — for example, the science that revealed the benefits of dexamethasone,” Asch told Medscape Medical News. “But it’s also a tribute to the doctors and nurses in the hospitals who developed experience. It’s a cliché to refer to them as heroes, but that is what they are. The science and the heroic experience continues on, and so I’m optimistic that we’ll see even more improvement over time.”

However, the data also indicate that “with lots of disease in the community, hospitals may have a harder time keeping patients alive,” Asch said. “And of course the reason this is bad news is that community level case rates are rising all over, and in some cases at rapid rates. With that rise, we might be giving back some of our past gains in survival — just as the vaccine is beginning to be distributed.”

Examining mortality trends

The researchers analyzed administrative claims data from a large national health insurer. They included data from 38,517 adults who were admitted with COVID-19 to 955 US hospitals between January 1 and June 30 of this year. The investigators estimated hospitals’ risk-standardized rate of 30-day in-hospital mortality or referral to hospice, adjusted for patient-level characteristics.

Overall, 3179 patients (8.25%) died, and 1433 patients (3.7%) were referred to hospice. Risk-standardized mortality or hospice referral rates for individual hospitals ranged from 5.7% to 24.7%. The average rate was 9.1% in the best-performing quintile, compared with 15.7% in the worst-performing quintile.

In a subset of 398 hospitals that had at least 10 patients admitted for COVID-19 during early (January 1 through April 30) and later periods (between May 1 and June 30), rates in all but one hospital improved, and 94% improved by at least 25%. The average risk-standardized event rate declined from 16.6% to 9.3%.

“That rate of relative improvement is striking and encouraging, but perhaps not surprising,” Asch and coauthors write. “Early efforts at treating patients with COVID-19 were based on experience with previously known causes of severe respiratory illness. Later efforts could draw on experiences specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

For instance, doctors tried different inpatient management approaches, such as early vs late assisted ventilation, differences in oxygen flow, prone or supine positioning, and anticoagulation. “Those efforts varied in how systematically they were evaluated, but our results suggest that valuable experience was gained,” the authors note.

In addition, variation between hospitals could reflect differences in quality or different admission thresholds, they continue.

The study provides “a reason for optimism that our healthcare system has improved in our ability to care for persons with COVID-19,” write Leon Boudourakis, MD, MHS, and Amit Uppal, MD, in a related commentary. Boudourakis and Uppal are both affiliated with NYC Health + Hospitals in New York City and with SUNY Downstate and New York University School of Medicine, respectively.

Similar improvements in mortality rates have been reported in the United Kingdom and in a New York City hospital system, the editorialists note. The lower mortality rates may represent clinical, healthcare system, and epidemiologic trends.

“Since the first wave of serious COVID-19 cases, physicians have learned a great deal about the best ways to treat this serious infection,” they say. “Steroids may decrease mortality in patients with respiratory failure. Remdesivir may shorten hospitalizations of patients with serious illness. Anticoagulation and prone positioning may help certain patients. Using noninvasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy may spare subsets of patients from the harms of intubation, such as ventilator-induced lung injury.»

Overwhelmed hospitals

“Hospitals do not perform as well when they are overwhelmed,” which may be a reason for the correlation between community prevalence and mortality rates, Boudourakis and Uppal suggested. “In particular, patients with a precarious respiratory status require expert, meticulous therapy to avoid intubation; those who undergo intubation or have kidney failure require nuanced and timely expert care with ventilatory adjustments and kidney replacement therapy, which are difficult to perform optimally when hospital capacity is strained.”

Although the death rate has fallen to about 9% for hospitalized patients, “9% is still high,” Asch said.

“Our results show that hospitals can’t do it on their own,” Asch said. “They need all of us to keep the community spread of the disease down. The right answer now is the right answer since the beginning of the pandemic: Keep your distance, wash your hands, and wear a mask.”

Asch, Boudourakis, and Uppal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A study coauthor reported personal fees and grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mortality rates for inpatients with COVID-19 dropped significantly during the first 6 months of the pandemic, but outcomes depend on the hospital where patients receive care, new data show.

“[T]he characteristic that is most associated with poor or worsening hospital outcomes is high or increasing community case rates,” write David A. Asch, MD, MBA, executive director of the Center for Health Care Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The relationship between COVID-19 mortality rates and local disease prevalence suggests that “hospitals do worse when they are burdened with cases and is consistent with imperatives to flatten the curve,” the authors continue. “As case rates of COVID-19 increase across the nation, hospital mortality outcomes may worsen.”

The researchers published their study online December 22 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The quick and substantial improvement in survival “is a tribute in part to new science — for example, the science that revealed the benefits of dexamethasone,” Asch told Medscape Medical News. “But it’s also a tribute to the doctors and nurses in the hospitals who developed experience. It’s a cliché to refer to them as heroes, but that is what they are. The science and the heroic experience continues on, and so I’m optimistic that we’ll see even more improvement over time.”

However, the data also indicate that “with lots of disease in the community, hospitals may have a harder time keeping patients alive,” Asch said. “And of course the reason this is bad news is that community level case rates are rising all over, and in some cases at rapid rates. With that rise, we might be giving back some of our past gains in survival — just as the vaccine is beginning to be distributed.”

Examining mortality trends

The researchers analyzed administrative claims data from a large national health insurer. They included data from 38,517 adults who were admitted with COVID-19 to 955 US hospitals between January 1 and June 30 of this year. The investigators estimated hospitals’ risk-standardized rate of 30-day in-hospital mortality or referral to hospice, adjusted for patient-level characteristics.

Overall, 3179 patients (8.25%) died, and 1433 patients (3.7%) were referred to hospice. Risk-standardized mortality or hospice referral rates for individual hospitals ranged from 5.7% to 24.7%. The average rate was 9.1% in the best-performing quintile, compared with 15.7% in the worst-performing quintile.

In a subset of 398 hospitals that had at least 10 patients admitted for COVID-19 during early (January 1 through April 30) and later periods (between May 1 and June 30), rates in all but one hospital improved, and 94% improved by at least 25%. The average risk-standardized event rate declined from 16.6% to 9.3%.

“That rate of relative improvement is striking and encouraging, but perhaps not surprising,” Asch and coauthors write. “Early efforts at treating patients with COVID-19 were based on experience with previously known causes of severe respiratory illness. Later efforts could draw on experiences specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

For instance, doctors tried different inpatient management approaches, such as early vs late assisted ventilation, differences in oxygen flow, prone or supine positioning, and anticoagulation. “Those efforts varied in how systematically they were evaluated, but our results suggest that valuable experience was gained,” the authors note.

In addition, variation between hospitals could reflect differences in quality or different admission thresholds, they continue.

The study provides “a reason for optimism that our healthcare system has improved in our ability to care for persons with COVID-19,” write Leon Boudourakis, MD, MHS, and Amit Uppal, MD, in a related commentary. Boudourakis and Uppal are both affiliated with NYC Health + Hospitals in New York City and with SUNY Downstate and New York University School of Medicine, respectively.

Similar improvements in mortality rates have been reported in the United Kingdom and in a New York City hospital system, the editorialists note. The lower mortality rates may represent clinical, healthcare system, and epidemiologic trends.

“Since the first wave of serious COVID-19 cases, physicians have learned a great deal about the best ways to treat this serious infection,” they say. “Steroids may decrease mortality in patients with respiratory failure. Remdesivir may shorten hospitalizations of patients with serious illness. Anticoagulation and prone positioning may help certain patients. Using noninvasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy may spare subsets of patients from the harms of intubation, such as ventilator-induced lung injury.»

Overwhelmed hospitals

“Hospitals do not perform as well when they are overwhelmed,” which may be a reason for the correlation between community prevalence and mortality rates, Boudourakis and Uppal suggested. “In particular, patients with a precarious respiratory status require expert, meticulous therapy to avoid intubation; those who undergo intubation or have kidney failure require nuanced and timely expert care with ventilatory adjustments and kidney replacement therapy, which are difficult to perform optimally when hospital capacity is strained.”

Although the death rate has fallen to about 9% for hospitalized patients, “9% is still high,” Asch said.

“Our results show that hospitals can’t do it on their own,” Asch said. “They need all of us to keep the community spread of the disease down. The right answer now is the right answer since the beginning of the pandemic: Keep your distance, wash your hands, and wear a mask.”

Asch, Boudourakis, and Uppal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A study coauthor reported personal fees and grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Mortality rates for inpatients with COVID-19 dropped significantly during the first 6 months of the pandemic, but outcomes depend on the hospital where patients receive care, new data show.

“[T]he characteristic that is most associated with poor or worsening hospital outcomes is high or increasing community case rates,” write David A. Asch, MD, MBA, executive director of the Center for Health Care Innovation at the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia, and colleagues.

The relationship between COVID-19 mortality rates and local disease prevalence suggests that “hospitals do worse when they are burdened with cases and is consistent with imperatives to flatten the curve,” the authors continue. “As case rates of COVID-19 increase across the nation, hospital mortality outcomes may worsen.”

The researchers published their study online December 22 in JAMA Internal Medicine.

The quick and substantial improvement in survival “is a tribute in part to new science — for example, the science that revealed the benefits of dexamethasone,” Asch told Medscape Medical News. “But it’s also a tribute to the doctors and nurses in the hospitals who developed experience. It’s a cliché to refer to them as heroes, but that is what they are. The science and the heroic experience continues on, and so I’m optimistic that we’ll see even more improvement over time.”

However, the data also indicate that “with lots of disease in the community, hospitals may have a harder time keeping patients alive,” Asch said. “And of course the reason this is bad news is that community level case rates are rising all over, and in some cases at rapid rates. With that rise, we might be giving back some of our past gains in survival — just as the vaccine is beginning to be distributed.”

Examining mortality trends

The researchers analyzed administrative claims data from a large national health insurer. They included data from 38,517 adults who were admitted with COVID-19 to 955 US hospitals between January 1 and June 30 of this year. The investigators estimated hospitals’ risk-standardized rate of 30-day in-hospital mortality or referral to hospice, adjusted for patient-level characteristics.

Overall, 3179 patients (8.25%) died, and 1433 patients (3.7%) were referred to hospice. Risk-standardized mortality or hospice referral rates for individual hospitals ranged from 5.7% to 24.7%. The average rate was 9.1% in the best-performing quintile, compared with 15.7% in the worst-performing quintile.

In a subset of 398 hospitals that had at least 10 patients admitted for COVID-19 during early (January 1 through April 30) and later periods (between May 1 and June 30), rates in all but one hospital improved, and 94% improved by at least 25%. The average risk-standardized event rate declined from 16.6% to 9.3%.

“That rate of relative improvement is striking and encouraging, but perhaps not surprising,” Asch and coauthors write. “Early efforts at treating patients with COVID-19 were based on experience with previously known causes of severe respiratory illness. Later efforts could draw on experiences specific to SARS-CoV-2 infection.”

For instance, doctors tried different inpatient management approaches, such as early vs late assisted ventilation, differences in oxygen flow, prone or supine positioning, and anticoagulation. “Those efforts varied in how systematically they were evaluated, but our results suggest that valuable experience was gained,” the authors note.

In addition, variation between hospitals could reflect differences in quality or different admission thresholds, they continue.

The study provides “a reason for optimism that our healthcare system has improved in our ability to care for persons with COVID-19,” write Leon Boudourakis, MD, MHS, and Amit Uppal, MD, in a related commentary. Boudourakis and Uppal are both affiliated with NYC Health + Hospitals in New York City and with SUNY Downstate and New York University School of Medicine, respectively.

Similar improvements in mortality rates have been reported in the United Kingdom and in a New York City hospital system, the editorialists note. The lower mortality rates may represent clinical, healthcare system, and epidemiologic trends.

“Since the first wave of serious COVID-19 cases, physicians have learned a great deal about the best ways to treat this serious infection,” they say. “Steroids may decrease mortality in patients with respiratory failure. Remdesivir may shorten hospitalizations of patients with serious illness. Anticoagulation and prone positioning may help certain patients. Using noninvasive ventilation and high-flow oxygen therapy may spare subsets of patients from the harms of intubation, such as ventilator-induced lung injury.»

Overwhelmed hospitals

“Hospitals do not perform as well when they are overwhelmed,” which may be a reason for the correlation between community prevalence and mortality rates, Boudourakis and Uppal suggested. “In particular, patients with a precarious respiratory status require expert, meticulous therapy to avoid intubation; those who undergo intubation or have kidney failure require nuanced and timely expert care with ventilatory adjustments and kidney replacement therapy, which are difficult to perform optimally when hospital capacity is strained.”

Although the death rate has fallen to about 9% for hospitalized patients, “9% is still high,” Asch said.

“Our results show that hospitals can’t do it on their own,” Asch said. “They need all of us to keep the community spread of the disease down. The right answer now is the right answer since the beginning of the pandemic: Keep your distance, wash your hands, and wear a mask.”

Asch, Boudourakis, and Uppal have disclosed no relevant financial relationships. A study coauthor reported personal fees and grants from pharmaceutical companies outside the submitted work.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital volumes start to fall again, even as COVID-19 soars

Hospital volumes, which had largely recovered in September after crashing last spring, are dropping again, according to new data from Strata Decision Technologies, a Chicago-based analytics firm.

For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, inpatient admissions were 6.2% below what they’d been on Nov. 14 and 2.1% below what they’d been on Oct. 28. Compared with the same intervals in 2019, admissions were off 4.4% for the 14-day period and 3.7% for the 30-day period.

Although those aren’t large percentages, Strata’s report, based on data from about 275 client hospitals, notes that what kept the volumes up was the increasing number of COVID-19 cases. If COVID-19 cases are not considered, admissions would have been down “double digits,” said Steve Lefar, executive director of StrataDataScience, a division of Strata Decision Technologies, in an interview with this news organization.

“Hip and knee replacements, cardiac procedures, and other procedures are significantly down year over year. Infectious disease cases, in contrast, have skyrocketed,” Mr. Lefar said. “Many things went way down that hadn’t fully recovered. It’s COVID-19 that really brought the volume back up.”

Observation and emergency department visits also dropped from already low levels. For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, observation visits were off 8.4%; for the previous month, 10.1%. Compared with 2019, they were down 22.3% and 18.6%, respectively.

ED visits fell 3.7% for the 2-week period, 0.6% for the month. They dropped 21% and 18.7%, respectively, compared with those periods from the previous year.

What these data reflect, Mr. Lefar said, is that people have avoided EDs and are staying away from them more than ever because of COVID-19 fears. This behavior could be problematic for people who have concerning symptoms, such as chest pains, that should be evaluated by an ED physician, he noted.

Daily outpatient visits were down 18.4% for the 14-day period and 9.3% for the 30-day period. But, compared with 2019, ambulatory visits increased 5.8% for the 2-week period and 4.7% for the previous month.

Long-term trends

The outpatient visit data should be viewed in the context of the overall trend since the pandemic began. Strata broke down service lines for the period between March 20 and Nov. 7. The analysis shows that evaluation and management (E/M) encounters, the largest outpatient visit category, fell 58% during this period, compared with the same interval in 2019. Visits for diabetes, hypertension, and minor acute infections and injuries were also way down.

Mr. Lefar observed that the E/M visit category was only for in-person visits, which many patients have ditched in favor of telehealth encounters. At the same time, he noted, “people are going in less for chronic disease visits. So there’s an interplay between less in-person visits, more telehealth, and maybe people going to other sites that aren’t on the hospital campus. But people are going less [to outpatient clinics].”

In the year-to-year comparison, volume was down substantially in other service lines, including cancer (–9.2%), cardiology (–20%), dermatology (–31%), endocrine (–18.8%), ENT (–42.5%), gastroenterology (–24.3%), nephrology (–15%), obstetrics (–15.6%), orthopedics (–28.2%), and general surgery (–22.2%). Major procedures decreased by 21.8%.

In contrast, the infectious disease category jumped 86% over 2019, and “other infectious and parasitic diseases” – i.e., COVID-19 – soared 222%.

There was a much bigger crash in admissions, observation visits, and ED visits last spring than in November, the report shows. “What happened nationally last spring is that everyone shut down,” Mr. Lefar explained. “All the electives were canceled. Even cancer surgery was shut down, along with many other procedures. That’s what drove that crash. But the provider community quickly learned that this is going to be a long haul, and we’re going to have to reopen. We’re going to do it safely, but we’re going to make sure people get the necessary care. We can’t put off cancer care or colonoscopies and other screenings that save lives.”

System starts to break down

The current wave of COVID-19, however, is beginning to change the definition of necessary care, he said. “Hospitals are reaching the breaking point between staff exhaustion and hospital capacity reaching its limit. In Texas, hospitals are starting to shut down certain essential non-COVID care. They’re turning away some nonurgent cases – the electives that were starting to come back.”

How about nonurgent COVID cases? Mr. Lefar said there’s evidence that some of those patients are also being diverted. “Some experts speculate that the turn-away rate of people with confirmed COVID is starting to go up, and hospitals are sending them home with oxygen or an oxygen meter and saying, ‘If it gets worse, come back.’ They just don’t have the critical care capacity – and that should scare the heck out of everybody.”

Strata doesn’t yet have the data to confirm this, he said, “but it appears that some people are being sent home. This may be partly because providers are better at telling which patients are acute, and there are better things they can send them home with. It’s not necessarily worse care, but we don’t know. But we’re definitely seeing a higher send-home rate of patients showing up with COVID.”

Hospital profit margins are cratering again, because the COVID-19 cases aren’t generating nearly as much profit as the lucrative procedures that, in many cases, have been put off, Mr. Lefar said. “Even though CMS is paying 20% more for verified COVID-19 patients, we know that the costs on these patients are much higher than expected, so they’re not making much money on these cases.”

For about a third of hospitals, margins are currently negative, he said. That is about the same percentage as in September. In April, 60% of health systems were losing money, he added. “The CARES Act saved some of them,” he noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital volumes, which had largely recovered in September after crashing last spring, are dropping again, according to new data from Strata Decision Technologies, a Chicago-based analytics firm.

For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, inpatient admissions were 6.2% below what they’d been on Nov. 14 and 2.1% below what they’d been on Oct. 28. Compared with the same intervals in 2019, admissions were off 4.4% for the 14-day period and 3.7% for the 30-day period.

Although those aren’t large percentages, Strata’s report, based on data from about 275 client hospitals, notes that what kept the volumes up was the increasing number of COVID-19 cases. If COVID-19 cases are not considered, admissions would have been down “double digits,” said Steve Lefar, executive director of StrataDataScience, a division of Strata Decision Technologies, in an interview with this news organization.

“Hip and knee replacements, cardiac procedures, and other procedures are significantly down year over year. Infectious disease cases, in contrast, have skyrocketed,” Mr. Lefar said. “Many things went way down that hadn’t fully recovered. It’s COVID-19 that really brought the volume back up.”

Observation and emergency department visits also dropped from already low levels. For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, observation visits were off 8.4%; for the previous month, 10.1%. Compared with 2019, they were down 22.3% and 18.6%, respectively.

ED visits fell 3.7% for the 2-week period, 0.6% for the month. They dropped 21% and 18.7%, respectively, compared with those periods from the previous year.

What these data reflect, Mr. Lefar said, is that people have avoided EDs and are staying away from them more than ever because of COVID-19 fears. This behavior could be problematic for people who have concerning symptoms, such as chest pains, that should be evaluated by an ED physician, he noted.

Daily outpatient visits were down 18.4% for the 14-day period and 9.3% for the 30-day period. But, compared with 2019, ambulatory visits increased 5.8% for the 2-week period and 4.7% for the previous month.

Long-term trends

The outpatient visit data should be viewed in the context of the overall trend since the pandemic began. Strata broke down service lines for the period between March 20 and Nov. 7. The analysis shows that evaluation and management (E/M) encounters, the largest outpatient visit category, fell 58% during this period, compared with the same interval in 2019. Visits for diabetes, hypertension, and minor acute infections and injuries were also way down.

Mr. Lefar observed that the E/M visit category was only for in-person visits, which many patients have ditched in favor of telehealth encounters. At the same time, he noted, “people are going in less for chronic disease visits. So there’s an interplay between less in-person visits, more telehealth, and maybe people going to other sites that aren’t on the hospital campus. But people are going less [to outpatient clinics].”

In the year-to-year comparison, volume was down substantially in other service lines, including cancer (–9.2%), cardiology (–20%), dermatology (–31%), endocrine (–18.8%), ENT (–42.5%), gastroenterology (–24.3%), nephrology (–15%), obstetrics (–15.6%), orthopedics (–28.2%), and general surgery (–22.2%). Major procedures decreased by 21.8%.

In contrast, the infectious disease category jumped 86% over 2019, and “other infectious and parasitic diseases” – i.e., COVID-19 – soared 222%.

There was a much bigger crash in admissions, observation visits, and ED visits last spring than in November, the report shows. “What happened nationally last spring is that everyone shut down,” Mr. Lefar explained. “All the electives were canceled. Even cancer surgery was shut down, along with many other procedures. That’s what drove that crash. But the provider community quickly learned that this is going to be a long haul, and we’re going to have to reopen. We’re going to do it safely, but we’re going to make sure people get the necessary care. We can’t put off cancer care or colonoscopies and other screenings that save lives.”

System starts to break down

The current wave of COVID-19, however, is beginning to change the definition of necessary care, he said. “Hospitals are reaching the breaking point between staff exhaustion and hospital capacity reaching its limit. In Texas, hospitals are starting to shut down certain essential non-COVID care. They’re turning away some nonurgent cases – the electives that were starting to come back.”

How about nonurgent COVID cases? Mr. Lefar said there’s evidence that some of those patients are also being diverted. “Some experts speculate that the turn-away rate of people with confirmed COVID is starting to go up, and hospitals are sending them home with oxygen or an oxygen meter and saying, ‘If it gets worse, come back.’ They just don’t have the critical care capacity – and that should scare the heck out of everybody.”

Strata doesn’t yet have the data to confirm this, he said, “but it appears that some people are being sent home. This may be partly because providers are better at telling which patients are acute, and there are better things they can send them home with. It’s not necessarily worse care, but we don’t know. But we’re definitely seeing a higher send-home rate of patients showing up with COVID.”

Hospital profit margins are cratering again, because the COVID-19 cases aren’t generating nearly as much profit as the lucrative procedures that, in many cases, have been put off, Mr. Lefar said. “Even though CMS is paying 20% more for verified COVID-19 patients, we know that the costs on these patients are much higher than expected, so they’re not making much money on these cases.”

For about a third of hospitals, margins are currently negative, he said. That is about the same percentage as in September. In April, 60% of health systems were losing money, he added. “The CARES Act saved some of them,” he noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Hospital volumes, which had largely recovered in September after crashing last spring, are dropping again, according to new data from Strata Decision Technologies, a Chicago-based analytics firm.

For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, inpatient admissions were 6.2% below what they’d been on Nov. 14 and 2.1% below what they’d been on Oct. 28. Compared with the same intervals in 2019, admissions were off 4.4% for the 14-day period and 3.7% for the 30-day period.

Although those aren’t large percentages, Strata’s report, based on data from about 275 client hospitals, notes that what kept the volumes up was the increasing number of COVID-19 cases. If COVID-19 cases are not considered, admissions would have been down “double digits,” said Steve Lefar, executive director of StrataDataScience, a division of Strata Decision Technologies, in an interview with this news organization.

“Hip and knee replacements, cardiac procedures, and other procedures are significantly down year over year. Infectious disease cases, in contrast, have skyrocketed,” Mr. Lefar said. “Many things went way down that hadn’t fully recovered. It’s COVID-19 that really brought the volume back up.”

Observation and emergency department visits also dropped from already low levels. For the 2 weeks that ended Nov. 28, observation visits were off 8.4%; for the previous month, 10.1%. Compared with 2019, they were down 22.3% and 18.6%, respectively.

ED visits fell 3.7% for the 2-week period, 0.6% for the month. They dropped 21% and 18.7%, respectively, compared with those periods from the previous year.

What these data reflect, Mr. Lefar said, is that people have avoided EDs and are staying away from them more than ever because of COVID-19 fears. This behavior could be problematic for people who have concerning symptoms, such as chest pains, that should be evaluated by an ED physician, he noted.

Daily outpatient visits were down 18.4% for the 14-day period and 9.3% for the 30-day period. But, compared with 2019, ambulatory visits increased 5.8% for the 2-week period and 4.7% for the previous month.

Long-term trends

The outpatient visit data should be viewed in the context of the overall trend since the pandemic began. Strata broke down service lines for the period between March 20 and Nov. 7. The analysis shows that evaluation and management (E/M) encounters, the largest outpatient visit category, fell 58% during this period, compared with the same interval in 2019. Visits for diabetes, hypertension, and minor acute infections and injuries were also way down.

Mr. Lefar observed that the E/M visit category was only for in-person visits, which many patients have ditched in favor of telehealth encounters. At the same time, he noted, “people are going in less for chronic disease visits. So there’s an interplay between less in-person visits, more telehealth, and maybe people going to other sites that aren’t on the hospital campus. But people are going less [to outpatient clinics].”

In the year-to-year comparison, volume was down substantially in other service lines, including cancer (–9.2%), cardiology (–20%), dermatology (–31%), endocrine (–18.8%), ENT (–42.5%), gastroenterology (–24.3%), nephrology (–15%), obstetrics (–15.6%), orthopedics (–28.2%), and general surgery (–22.2%). Major procedures decreased by 21.8%.

In contrast, the infectious disease category jumped 86% over 2019, and “other infectious and parasitic diseases” – i.e., COVID-19 – soared 222%.

There was a much bigger crash in admissions, observation visits, and ED visits last spring than in November, the report shows. “What happened nationally last spring is that everyone shut down,” Mr. Lefar explained. “All the electives were canceled. Even cancer surgery was shut down, along with many other procedures. That’s what drove that crash. But the provider community quickly learned that this is going to be a long haul, and we’re going to have to reopen. We’re going to do it safely, but we’re going to make sure people get the necessary care. We can’t put off cancer care or colonoscopies and other screenings that save lives.”

System starts to break down

The current wave of COVID-19, however, is beginning to change the definition of necessary care, he said. “Hospitals are reaching the breaking point between staff exhaustion and hospital capacity reaching its limit. In Texas, hospitals are starting to shut down certain essential non-COVID care. They’re turning away some nonurgent cases – the electives that were starting to come back.”

How about nonurgent COVID cases? Mr. Lefar said there’s evidence that some of those patients are also being diverted. “Some experts speculate that the turn-away rate of people with confirmed COVID is starting to go up, and hospitals are sending them home with oxygen or an oxygen meter and saying, ‘If it gets worse, come back.’ They just don’t have the critical care capacity – and that should scare the heck out of everybody.”

Strata doesn’t yet have the data to confirm this, he said, “but it appears that some people are being sent home. This may be partly because providers are better at telling which patients are acute, and there are better things they can send them home with. It’s not necessarily worse care, but we don’t know. But we’re definitely seeing a higher send-home rate of patients showing up with COVID.”

Hospital profit margins are cratering again, because the COVID-19 cases aren’t generating nearly as much profit as the lucrative procedures that, in many cases, have been put off, Mr. Lefar said. “Even though CMS is paying 20% more for verified COVID-19 patients, we know that the costs on these patients are much higher than expected, so they’re not making much money on these cases.”

For about a third of hospitals, margins are currently negative, he said. That is about the same percentage as in September. In April, 60% of health systems were losing money, he added. “The CARES Act saved some of them,” he noted.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Leading in crisis

Lessons from the trail

I have learned a lot about crisis management and leadership in the rapidly changing COVID health care environment. I have learned how to make quick and imperfect decisions with limited information, and how to move on swiftly. I have learned how to quickly fade out memories of how we used to run our business, and pivot to unknown and untested delivery modalities. I have learned how to take regulatory standards as guidance, not doctrine. And I have learned how tell longstanding loyal colleagues that they are being laid off.

Many of these leadership challenges are not new, but the rapidity of change and the weight and magnitude of decision making is unparalleled in my relatively short career. In some ways, it reminds me of some solid lessons I have learned over time as a lifetime runner, with many analogies and applications to leadership.

Some people ask me why I run. “You must get a runner’s high.” The truth is, I have never had a runner’s high. I feel every step. In fact, the very nature of running makes a person feel like they are being pulled under water. Runners are typically tachycardic and short of breath the whole time they are running. But what running does allow for is to ignore some of the signals your body is sending, and wholly and completely focus on other things. I often have my most creative and innovative thoughts while running. So that is why I run. But back to the point of what running and leadership have in common – and how lessons learned can translate between the two:

They are both really hard. As I mentioned above, running literally makes you feel like you are drowning. But when you finish running, it is amazing how easy everything else feels! Similar to leadership, it should feel hard, but not too hard. I have seen firsthand the effects of under- and over-delegating, and both are dysfunctional. Good leadership is a blend of being humble and servant, but also ensuring self-care and endurance. It is also important to acknowledge the difficulty of leadership. Dr. Tom Lee, currently chief medical officer at Press Ganey, is a leader I have always admired. He once said, “Leadership can be very lonely.” At the time, I did not quite understand that, but I have come to experience that feeling occasionally. The other aspect of leadership that I find really hard is that often, people’s anger is misdirected at leaders as a natural outlet for that anger. Part of being a leader is enduring such anger, gaining an understanding for it, and doing what you can to help people through it.

They both work better when you are restored. It sounds generic and cliché, but you can’t be a good runner or a good leader when you are totally depleted.

They both require efficiency. When I was running my first marathon, a complete stranger ran up beside me and started giving me advice. I thought it was sort of strange advice at the time, but it turned out to be sound and useful. He noticed my running pattern of “sticking to the road,” and he told me I should rather “run as the crow flies.” What he meant was to run in as straight of a line as possible, regardless of the road, to preserve energy and save steps. He recommended picking a point on the horizon and running toward that point as straight as possible. As he sped off ahead of me in the next mile, his parting words were, “You’ll thank me at mile 24…” To this day, I still use that tactic, which I find very steadying and calming during running. The same can be said for leadership; as you pick a point on the horizon, keep yourself and your team heading toward that point with intense focus, and before you realize it, you’ve reached your destination.

They both require having a goal. That same stranger who gave me advice on running efficiently also asked what my goal was. It caught me off guard a bit, as I realized my only goal was to finish. He encouraged me to make a goal for the run, which could serve as a motivator when the going got tough. This was another piece of lasting advice I have used for both running and for leadership.

They both can be endured by committing to continuous forward motion. Running and leadership both become psychologically much easier when you realize all you really have to do is maintain continuous forward motion. Some days require less effort than others, but I can always convince myself I am capable of some forward motion.

They both are easier if you don’t overthink things. When I first started in a leadership position, I would have moments of anxiety if I thought too hard about what I was responsible for. Similar to running, it works best if you don’t overthink what difficulties it may bring; rather, just put on your shoes and get going.

In the end, leading during COVID is like stepping onto a new trail. Despite the new terrain and foreign path, my prior training and trusty pair of sneakers – like my leadership skills and past experiences – will get me through this journey, one step at a time.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Lessons from the trail

Lessons from the trail

I have learned a lot about crisis management and leadership in the rapidly changing COVID health care environment. I have learned how to make quick and imperfect decisions with limited information, and how to move on swiftly. I have learned how to quickly fade out memories of how we used to run our business, and pivot to unknown and untested delivery modalities. I have learned how to take regulatory standards as guidance, not doctrine. And I have learned how tell longstanding loyal colleagues that they are being laid off.

Many of these leadership challenges are not new, but the rapidity of change and the weight and magnitude of decision making is unparalleled in my relatively short career. In some ways, it reminds me of some solid lessons I have learned over time as a lifetime runner, with many analogies and applications to leadership.

Some people ask me why I run. “You must get a runner’s high.” The truth is, I have never had a runner’s high. I feel every step. In fact, the very nature of running makes a person feel like they are being pulled under water. Runners are typically tachycardic and short of breath the whole time they are running. But what running does allow for is to ignore some of the signals your body is sending, and wholly and completely focus on other things. I often have my most creative and innovative thoughts while running. So that is why I run. But back to the point of what running and leadership have in common – and how lessons learned can translate between the two:

They are both really hard. As I mentioned above, running literally makes you feel like you are drowning. But when you finish running, it is amazing how easy everything else feels! Similar to leadership, it should feel hard, but not too hard. I have seen firsthand the effects of under- and over-delegating, and both are dysfunctional. Good leadership is a blend of being humble and servant, but also ensuring self-care and endurance. It is also important to acknowledge the difficulty of leadership. Dr. Tom Lee, currently chief medical officer at Press Ganey, is a leader I have always admired. He once said, “Leadership can be very lonely.” At the time, I did not quite understand that, but I have come to experience that feeling occasionally. The other aspect of leadership that I find really hard is that often, people’s anger is misdirected at leaders as a natural outlet for that anger. Part of being a leader is enduring such anger, gaining an understanding for it, and doing what you can to help people through it.

They both work better when you are restored. It sounds generic and cliché, but you can’t be a good runner or a good leader when you are totally depleted.

They both require efficiency. When I was running my first marathon, a complete stranger ran up beside me and started giving me advice. I thought it was sort of strange advice at the time, but it turned out to be sound and useful. He noticed my running pattern of “sticking to the road,” and he told me I should rather “run as the crow flies.” What he meant was to run in as straight of a line as possible, regardless of the road, to preserve energy and save steps. He recommended picking a point on the horizon and running toward that point as straight as possible. As he sped off ahead of me in the next mile, his parting words were, “You’ll thank me at mile 24…” To this day, I still use that tactic, which I find very steadying and calming during running. The same can be said for leadership; as you pick a point on the horizon, keep yourself and your team heading toward that point with intense focus, and before you realize it, you’ve reached your destination.

They both require having a goal. That same stranger who gave me advice on running efficiently also asked what my goal was. It caught me off guard a bit, as I realized my only goal was to finish. He encouraged me to make a goal for the run, which could serve as a motivator when the going got tough. This was another piece of lasting advice I have used for both running and for leadership.

They both can be endured by committing to continuous forward motion. Running and leadership both become psychologically much easier when you realize all you really have to do is maintain continuous forward motion. Some days require less effort than others, but I can always convince myself I am capable of some forward motion.

They both are easier if you don’t overthink things. When I first started in a leadership position, I would have moments of anxiety if I thought too hard about what I was responsible for. Similar to running, it works best if you don’t overthink what difficulties it may bring; rather, just put on your shoes and get going.

In the end, leading during COVID is like stepping onto a new trail. Despite the new terrain and foreign path, my prior training and trusty pair of sneakers – like my leadership skills and past experiences – will get me through this journey, one step at a time.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

I have learned a lot about crisis management and leadership in the rapidly changing COVID health care environment. I have learned how to make quick and imperfect decisions with limited information, and how to move on swiftly. I have learned how to quickly fade out memories of how we used to run our business, and pivot to unknown and untested delivery modalities. I have learned how to take regulatory standards as guidance, not doctrine. And I have learned how tell longstanding loyal colleagues that they are being laid off.

Many of these leadership challenges are not new, but the rapidity of change and the weight and magnitude of decision making is unparalleled in my relatively short career. In some ways, it reminds me of some solid lessons I have learned over time as a lifetime runner, with many analogies and applications to leadership.

Some people ask me why I run. “You must get a runner’s high.” The truth is, I have never had a runner’s high. I feel every step. In fact, the very nature of running makes a person feel like they are being pulled under water. Runners are typically tachycardic and short of breath the whole time they are running. But what running does allow for is to ignore some of the signals your body is sending, and wholly and completely focus on other things. I often have my most creative and innovative thoughts while running. So that is why I run. But back to the point of what running and leadership have in common – and how lessons learned can translate between the two:

They are both really hard. As I mentioned above, running literally makes you feel like you are drowning. But when you finish running, it is amazing how easy everything else feels! Similar to leadership, it should feel hard, but not too hard. I have seen firsthand the effects of under- and over-delegating, and both are dysfunctional. Good leadership is a blend of being humble and servant, but also ensuring self-care and endurance. It is also important to acknowledge the difficulty of leadership. Dr. Tom Lee, currently chief medical officer at Press Ganey, is a leader I have always admired. He once said, “Leadership can be very lonely.” At the time, I did not quite understand that, but I have come to experience that feeling occasionally. The other aspect of leadership that I find really hard is that often, people’s anger is misdirected at leaders as a natural outlet for that anger. Part of being a leader is enduring such anger, gaining an understanding for it, and doing what you can to help people through it.

They both work better when you are restored. It sounds generic and cliché, but you can’t be a good runner or a good leader when you are totally depleted.

They both require efficiency. When I was running my first marathon, a complete stranger ran up beside me and started giving me advice. I thought it was sort of strange advice at the time, but it turned out to be sound and useful. He noticed my running pattern of “sticking to the road,” and he told me I should rather “run as the crow flies.” What he meant was to run in as straight of a line as possible, regardless of the road, to preserve energy and save steps. He recommended picking a point on the horizon and running toward that point as straight as possible. As he sped off ahead of me in the next mile, his parting words were, “You’ll thank me at mile 24…” To this day, I still use that tactic, which I find very steadying and calming during running. The same can be said for leadership; as you pick a point on the horizon, keep yourself and your team heading toward that point with intense focus, and before you realize it, you’ve reached your destination.

They both require having a goal. That same stranger who gave me advice on running efficiently also asked what my goal was. It caught me off guard a bit, as I realized my only goal was to finish. He encouraged me to make a goal for the run, which could serve as a motivator when the going got tough. This was another piece of lasting advice I have used for both running and for leadership.

They both can be endured by committing to continuous forward motion. Running and leadership both become psychologically much easier when you realize all you really have to do is maintain continuous forward motion. Some days require less effort than others, but I can always convince myself I am capable of some forward motion.

They both are easier if you don’t overthink things. When I first started in a leadership position, I would have moments of anxiety if I thought too hard about what I was responsible for. Similar to running, it works best if you don’t overthink what difficulties it may bring; rather, just put on your shoes and get going.

In the end, leading during COVID is like stepping onto a new trail. Despite the new terrain and foreign path, my prior training and trusty pair of sneakers – like my leadership skills and past experiences – will get me through this journey, one step at a time.

Dr. Scheurer is chief quality officer and professor of medicine at the Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston. She is president of SHM.

Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine deemed ‘highly effective,’ but further studies needed

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) evaluated

The panel acknowledged that further studies will be required post issuance of an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to collect additional data on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. A briefing document released by the FDA on Dec. 17, 2020, summarized interim results and included recommendations from VRBPAC on use of Moderna’s mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine.

“On November 30, 2020, ModernaTX (the Sponsor) submitted an EUA request to FDA for an investigational COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) intended to prevent COVID-19,” the committee wrote.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine trial

Among 30,351 individuals aged 18 years and older, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the mRNA-1273 vaccine candidate was evaluated in a randomized, stratified, observer-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive two injections of either 100 mcg of mRNA-1273 (n = 15,181) or saline placebo (n = 15,170) administered intramuscularly on day 1 and day 29.

The primary efficacy endpoint was efficacy of mRNA-1273 against PCR-confirmed COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days following the second dose. The primary safety endpoint was to characterize the safety of the vaccine following one or two doses.

Efficacy

Among 27,817 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 7, 2020), 5 cases of COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose occurred among vaccine recipients and 90 case occurred among placebo recipients, corresponding to 94.5% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 86.5%-97.8%).

“Subgroup analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint showed similar efficacy point estimates across age groups, genders, racial and ethnic groups, and participants with medical comorbidities associated with high risk of severe COVID-19,” they reported.

Data from the final scheduled analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint (data cutoff: Nov. 21, 2020; median follow-up of >2 months after dose 2), demonstrated 94.1% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 89.3%-96.8%), corresponding to 11 cases of COVID-19 in the vaccine group and 185 cases in the placebo group.

When stratified by age, the vaccine efficacy was 95.6% (95% CI, 90.6%-97.9%) for individuals 18-64 years of age and 86.4% (95% CI, 61.4%-95.5%) for those 65 years of age or older.

In addition, results from secondary analyses indicated benefit for mRNA-1273 in preventing severe COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 in those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, and infection after the first dose, but these data were not conclusive.

Safety

Among 30,350 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 11, 2020; median follow-up of 7 weeks post second dose), no specific safety concerns were observed that would prevent issuance of an EUA.

Additional safety data (data cutoff: Nov. 25, 2020; median follow-up of 9 weeks post second dose) were provided on Dec. 7, 2020, but did not change the conclusions from the first interim analysis.

The most common vaccine-related adverse reactions were injection site pain (91.6%), fatigue (68.5%), headache (63.0%), muscle pain (59.6%), joint pain (44.8%), and chills (43.4%).

“The frequency of serious adverse events (SAEs) was low (1.0% in the mRNA-1273 arm and 1.0% in the placebo arm), without meaningful imbalances between study arms,” they reported.

Myocardial infarction (0.03%), nephrolithiasis (0.02%), and cholecystitis (0.02%) were the most common SAEs that were numerically greater in the vaccine arm than the placebo arm; however, the small number of cases does not infer a casual relationship.

“The 2-dose vaccination regimen was highly effective in preventing PCR-confirmed COVID-19 occurring at least 14 days after receipt of the second dose,” the committee wrote. “[However], it is critical to continue to gather data about the vaccine even after it is made available under EUA.”

The associated phase 3 study was sponsored by ModernaTX.

SOURCE: FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. FDA Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. Published Dec. 17, 2020.

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) evaluated

The panel acknowledged that further studies will be required post issuance of an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to collect additional data on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. A briefing document released by the FDA on Dec. 17, 2020, summarized interim results and included recommendations from VRBPAC on use of Moderna’s mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine.

“On November 30, 2020, ModernaTX (the Sponsor) submitted an EUA request to FDA for an investigational COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) intended to prevent COVID-19,” the committee wrote.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine trial

Among 30,351 individuals aged 18 years and older, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the mRNA-1273 vaccine candidate was evaluated in a randomized, stratified, observer-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive two injections of either 100 mcg of mRNA-1273 (n = 15,181) or saline placebo (n = 15,170) administered intramuscularly on day 1 and day 29.

The primary efficacy endpoint was efficacy of mRNA-1273 against PCR-confirmed COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days following the second dose. The primary safety endpoint was to characterize the safety of the vaccine following one or two doses.

Efficacy

Among 27,817 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 7, 2020), 5 cases of COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose occurred among vaccine recipients and 90 case occurred among placebo recipients, corresponding to 94.5% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 86.5%-97.8%).

“Subgroup analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint showed similar efficacy point estimates across age groups, genders, racial and ethnic groups, and participants with medical comorbidities associated with high risk of severe COVID-19,” they reported.

Data from the final scheduled analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint (data cutoff: Nov. 21, 2020; median follow-up of >2 months after dose 2), demonstrated 94.1% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 89.3%-96.8%), corresponding to 11 cases of COVID-19 in the vaccine group and 185 cases in the placebo group.

When stratified by age, the vaccine efficacy was 95.6% (95% CI, 90.6%-97.9%) for individuals 18-64 years of age and 86.4% (95% CI, 61.4%-95.5%) for those 65 years of age or older.

In addition, results from secondary analyses indicated benefit for mRNA-1273 in preventing severe COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 in those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, and infection after the first dose, but these data were not conclusive.

Safety

Among 30,350 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 11, 2020; median follow-up of 7 weeks post second dose), no specific safety concerns were observed that would prevent issuance of an EUA.

Additional safety data (data cutoff: Nov. 25, 2020; median follow-up of 9 weeks post second dose) were provided on Dec. 7, 2020, but did not change the conclusions from the first interim analysis.

The most common vaccine-related adverse reactions were injection site pain (91.6%), fatigue (68.5%), headache (63.0%), muscle pain (59.6%), joint pain (44.8%), and chills (43.4%).

“The frequency of serious adverse events (SAEs) was low (1.0% in the mRNA-1273 arm and 1.0% in the placebo arm), without meaningful imbalances between study arms,” they reported.

Myocardial infarction (0.03%), nephrolithiasis (0.02%), and cholecystitis (0.02%) were the most common SAEs that were numerically greater in the vaccine arm than the placebo arm; however, the small number of cases does not infer a casual relationship.

“The 2-dose vaccination regimen was highly effective in preventing PCR-confirmed COVID-19 occurring at least 14 days after receipt of the second dose,” the committee wrote. “[However], it is critical to continue to gather data about the vaccine even after it is made available under EUA.”

The associated phase 3 study was sponsored by ModernaTX.

SOURCE: FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. FDA Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. Published Dec. 17, 2020.

The Food and Drug Administration’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee (VRBPAC) evaluated

The panel acknowledged that further studies will be required post issuance of an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) to collect additional data on the safety and effectiveness of the vaccine. A briefing document released by the FDA on Dec. 17, 2020, summarized interim results and included recommendations from VRBPAC on use of Moderna’s mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine.

“On November 30, 2020, ModernaTX (the Sponsor) submitted an EUA request to FDA for an investigational COVID-19 vaccine (mRNA-1273) intended to prevent COVID-19,” the committee wrote.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine trial

Among 30,351 individuals aged 18 years and older, the efficacy, safety, and immunogenicity of the mRNA-1273 vaccine candidate was evaluated in a randomized, stratified, observer-blind, placebo-controlled phase 3 study. Participants were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive two injections of either 100 mcg of mRNA-1273 (n = 15,181) or saline placebo (n = 15,170) administered intramuscularly on day 1 and day 29.

The primary efficacy endpoint was efficacy of mRNA-1273 against PCR-confirmed COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days following the second dose. The primary safety endpoint was to characterize the safety of the vaccine following one or two doses.

Efficacy

Among 27,817 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 7, 2020), 5 cases of COVID-19 with onset at least 14 days after the second dose occurred among vaccine recipients and 90 case occurred among placebo recipients, corresponding to 94.5% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 86.5%-97.8%).

“Subgroup analyses of the primary efficacy endpoint showed similar efficacy point estimates across age groups, genders, racial and ethnic groups, and participants with medical comorbidities associated with high risk of severe COVID-19,” they reported.

Data from the final scheduled analysis of the primary efficacy endpoint (data cutoff: Nov. 21, 2020; median follow-up of >2 months after dose 2), demonstrated 94.1% vaccine efficacy (95% confidence interval, 89.3%-96.8%), corresponding to 11 cases of COVID-19 in the vaccine group and 185 cases in the placebo group.

When stratified by age, the vaccine efficacy was 95.6% (95% CI, 90.6%-97.9%) for individuals 18-64 years of age and 86.4% (95% CI, 61.4%-95.5%) for those 65 years of age or older.

In addition, results from secondary analyses indicated benefit for mRNA-1273 in preventing severe COVID-19 cases, COVID-19 in those with prior SARS-CoV-2 infection, and infection after the first dose, but these data were not conclusive.

Safety

Among 30,350 subjects included in the first interim analysis (data cutoff: Nov. 11, 2020; median follow-up of 7 weeks post second dose), no specific safety concerns were observed that would prevent issuance of an EUA.

Additional safety data (data cutoff: Nov. 25, 2020; median follow-up of 9 weeks post second dose) were provided on Dec. 7, 2020, but did not change the conclusions from the first interim analysis.

The most common vaccine-related adverse reactions were injection site pain (91.6%), fatigue (68.5%), headache (63.0%), muscle pain (59.6%), joint pain (44.8%), and chills (43.4%).

“The frequency of serious adverse events (SAEs) was low (1.0% in the mRNA-1273 arm and 1.0% in the placebo arm), without meaningful imbalances between study arms,” they reported.

Myocardial infarction (0.03%), nephrolithiasis (0.02%), and cholecystitis (0.02%) were the most common SAEs that were numerically greater in the vaccine arm than the placebo arm; however, the small number of cases does not infer a casual relationship.

“The 2-dose vaccination regimen was highly effective in preventing PCR-confirmed COVID-19 occurring at least 14 days after receipt of the second dose,” the committee wrote. “[However], it is critical to continue to gather data about the vaccine even after it is made available under EUA.”

The associated phase 3 study was sponsored by ModernaTX.

SOURCE: FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. FDA Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. Published Dec. 17, 2020.

Key clinical point: The FDA’s Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee regarded Moderna’s COVID-19 vaccine as highly effective with a favorable safety profile, based on interim phase 3 results.

Major finding: The two-dose vaccine regimen had a low frequency of serious adverse events (1.0% each in the mRNA-1273 and placebo arms, respectively) and demonstrated 94.1% (95% CI, 89.3%-96.8%) vaccine efficacy.

Study details: A briefing document summarized interim data and recommendations from the FDA’s VRBPAC on Moderna’s mRNA-1273 COVID-19 vaccine.

Disclosures: The associated phase 3 study was sponsored by ModernaTX.

Source: FDA Briefing Document: Moderna COVID-19 Vaccine. FDA Vaccines and Related Biological Products Advisory Committee. Published Dec. 17, 2020.

Child abuse visits to EDs declined in 2020, but not admissions

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

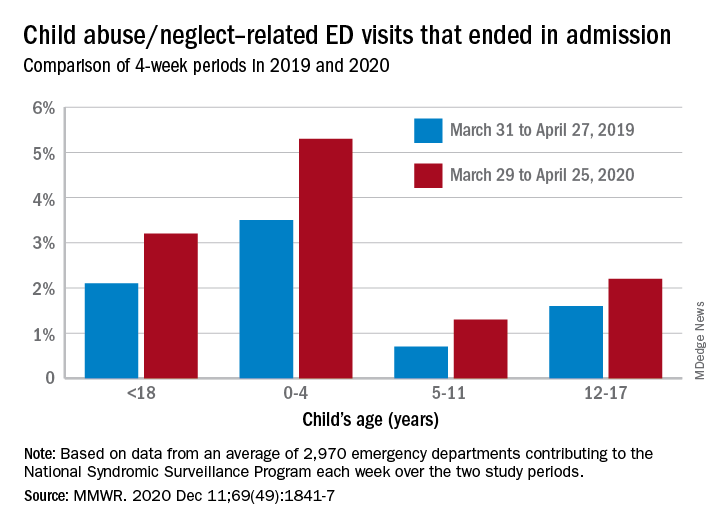

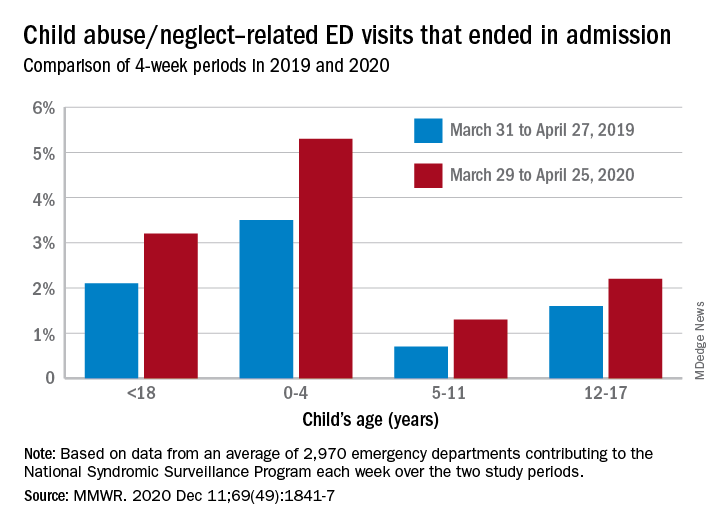

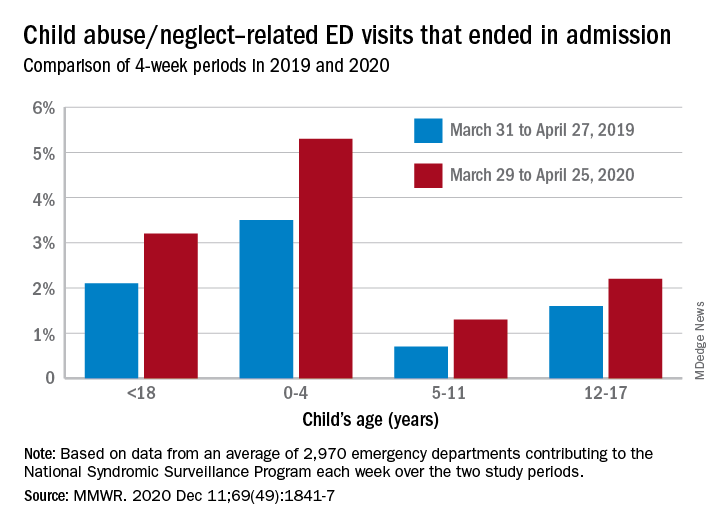

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

but the visits in 2020 were significantly more likely to result in hospitalization, based on analysis of a national ED database.

The number of ED visits involving child abuse and neglect was down by 53% during the 4-week period from March 29 to April 25, 2020, compared with the 4 weeks from March 31 to April 27, 2019. The proportion of those ED visits that ended in hospitalizations, however, increased from 2.1% in 2019 to 3.2% in 2020, Elizabeth Swedo, MD, and associates at the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention said in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

“ED visits related to suspected or confirmed child abuse and neglect decreased beginning the week of March 15, 2020, coinciding with the declaration of a national emergency related to COVID-19 and implementation of community mitigation measures,” they wrote.

An earlier study involving the same database (the National Syndromic Surveillance Program) showed that, over the two same 4-week periods, the volume of all ED visits in 2020 was down 72% for children aged 10 years and younger and 71% for those aged 11-14 years.

In the current study, however, all age subgroups had significant increases in hospital admissions. The proportion of ED visits related to child abuse and neglect that resulted in hospitalization rose from 3.5% in 2019 to 5.3% in 2020 among ages 0-4 years, 0.7% to 1.3% for ages 5-11 years, and 1.6% to 2.2% for adolescents aged 12-17, Dr. Swedo and associates reported.

The absence of a corresponding drop in hospitalizations may be tied to risk factors related to the pandemic, “such as loss of income, increased stress related to parental child care and schooling responsibilities, and increased substance use and mental health conditions among adults,” the investigators added.

The National Syndromic Surveillance Program receives daily data from 3,310 EDs in 47 states, but the number of facilities meeting the investigators’ criteria averaged 2,970 a week for the 8 weeks of the study period.

SOURCE: Swedo E et al. MMWR. 2020 Dec. 11;69(49):1841-7.

FROM MMWR

Call to arms: vaccinating the health workforce of 21 million strong

As the first American health care workers rolled up their sleeves for a COVID-19 vaccine, the images were instantly frozen in history, marking the triumph of scientific know-how and ingenuity. Cameras captured the first trucks pulling out of a warehouse in Portage, Mich., to the applause of workers and area residents. A day later, Boston Medical Center employees – some dressed in scrubs and wearing masks, face shields, and protective gowns – literally danced on the sidewalk when doses arrived. Some have photographed themselves getting the vaccine and posted it on social media, tagging it #MyCOVIDVax.

But the real story of the debut of COVID-19 vaccination is more methodical than monumental, a celebration of teamwork rather than of conquest. As hospitals waited for their first allotment, they reviewed their carefully drafted plans. They relied on each other, reaching across the usual divisions of competition and working collaboratively to share the limited supply. Their priority lists for the first vaccinations included environmental services workers who clean patient rooms and the critical care physicians who work to save lives.

“Health care workers have pulled together throughout this pandemic,” said Melanie Swift, MD, cochair of the COVID-19 Vaccine Allocation and Distribution Work Group at Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minn. “We’ve gone through the darkest of years relying so heavily on each other,” she said. “Now we’re pulling together to get out of it.”

Still, a rollout of this magnitude has hitches. Stanford issued an apology Dec. 18 after its medical residents protested a vaccine distribution plan that left out nearly all of its residents and fellows, many of whom regularly treat patients with COVID-19.

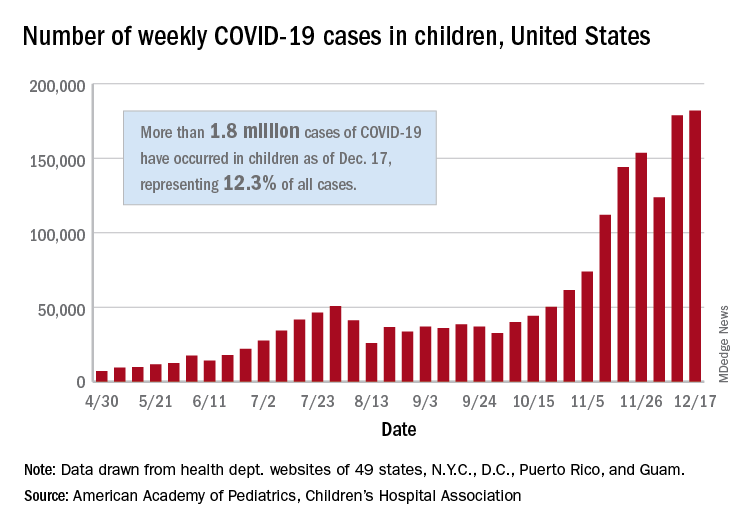

There have already been more than 287,000 COVID-19 cases and 953 deaths among health care workers, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. In its guidance, the agency pointed out that the “continued protection of them at work, at home, and in the community remains a national priority.” That means vaccinating a workforce of about 21 million people, often the largest group of employees in a community.

“It collectively takes all of us to vaccinate our teams to maintain that stability in our health care infrastructure across the metro Atlanta area,” Christy Norman, PharmD, vice president of pharmacy services at Emory Healthcare, told reporters in a briefing as the health system awaited its first delivery.

Don’t waste a dose

One overriding imperative prevails: Hospitals don’t want to waste any doses. The storage requirements of the Pfizer vaccine make that tricky.

Once vials are removed from the pizza-box-shaped containers in ultracold storage and placed in a refrigerator, they must be used within 5 days. Thawed five-dose vials must be brought to room temperature before they are diluted, and they can remain at room temperature for no more than 2 hours. Once they are diluted with 1.8 mL of a 0.9% sodium chloride injection, the vials must be used within 6 hours.

COVID-19 precautions require employees to stay physically distant while they wait their turn for vaccination, which means the process can’t mirror typical large-scale flu immunization programs.

To prioritize groups, the vaccination planners at Mayo conducted a thorough risk stratification, considering each employee’s duties. Do they work in a dedicated COVID-19 unit? Do they handle lab tests or collect swabs? Do they work in the ICU or emergency department?

“We have applied some principles to make sure that as we roll it out, we prioritize people who are at greatest risk of ongoing exposure and who are really critical to maintaining the COVID response and other essential health services,” said Dr. Swift, associate medical director of Mayo’s occupational health service.

Mayo employees who are eligible for the first doses can sign up for appointments through the medical record system. If it seems likely that some doses will be left over at the end of the vaccination period – perhaps because of missed appointments – supervisors in high-risk areas can refer other health care workers. Mayo gave its first vaccines on Dec. 18, but the vaccination program began in earnest the following week. With the pleasant surprise that each five-dose vial actually provides six doses, 474 vials will allow for the vaccination of 2,844 employees in the top-priority group. “It’s going to expand each week or few days as we get more and more vaccine,” Dr. Swift said.

Sharing vials with small rural hospitals

Minnesota is using a hub-and-spoke system to give small rural hospitals access to the Pfizer vaccine, even though they lack ultracold storage and can’t use a minimum order of 975 doses. Large hospitals, acting as hubs, are sharing their orders. (The minimum order for Moderna is 100 doses.)

In south-central Minnesota, for example, two hub hospitals each have six spoke hospitals. Five of the 14 hospitals are independent, and the rest are part of large hospital systems, but affiliation doesn’t matter, said Eric Weller, regional health care preparedness coordinator for the South Central Healthcare Coalition. “We are all working together. It doesn’t matter what system you’re from,” he said. “We’re working for the good of the community.”

Each hospital designed a process to provide vaccine education, prioritize groups, allocate appointments, register people for vaccination, obtain signed consent forms, administer vaccines in a COVID-safe way, and provide follow-up appointments for the second dose. “We’re using some of the lessons we learned during H1N1,” said Mr. Weller, referring to immunization during the 2009 influenza pandemic. “The difference is that during H1N1, you could have lines of people.”

Coordinating the appointments will be more important than ever. “One of the vaccination strategies is to get people in groups of five, so you use one vial on those five people and don’t waste it,” he said.

Logistics are somewhat different for the Moderna vaccine, which will come in 10-dose vials that can be refrigerated for up to 30 days.