User login

Official news magazine of the Society of Hospital Medicine

Copyright by Society of Hospital Medicine or related companies. All rights reserved. ISSN 1553-085X

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack nav-ce-stack__large-screen')]

header[@id='header']

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

div[contains(@class, 'view-medstat-quiz-listing-panes')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-article-sidebar-latest-news')]

div[contains(@class, 'pane-pub-article-hospitalist')]

California’s highest COVID infection rates shift to rural counties

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

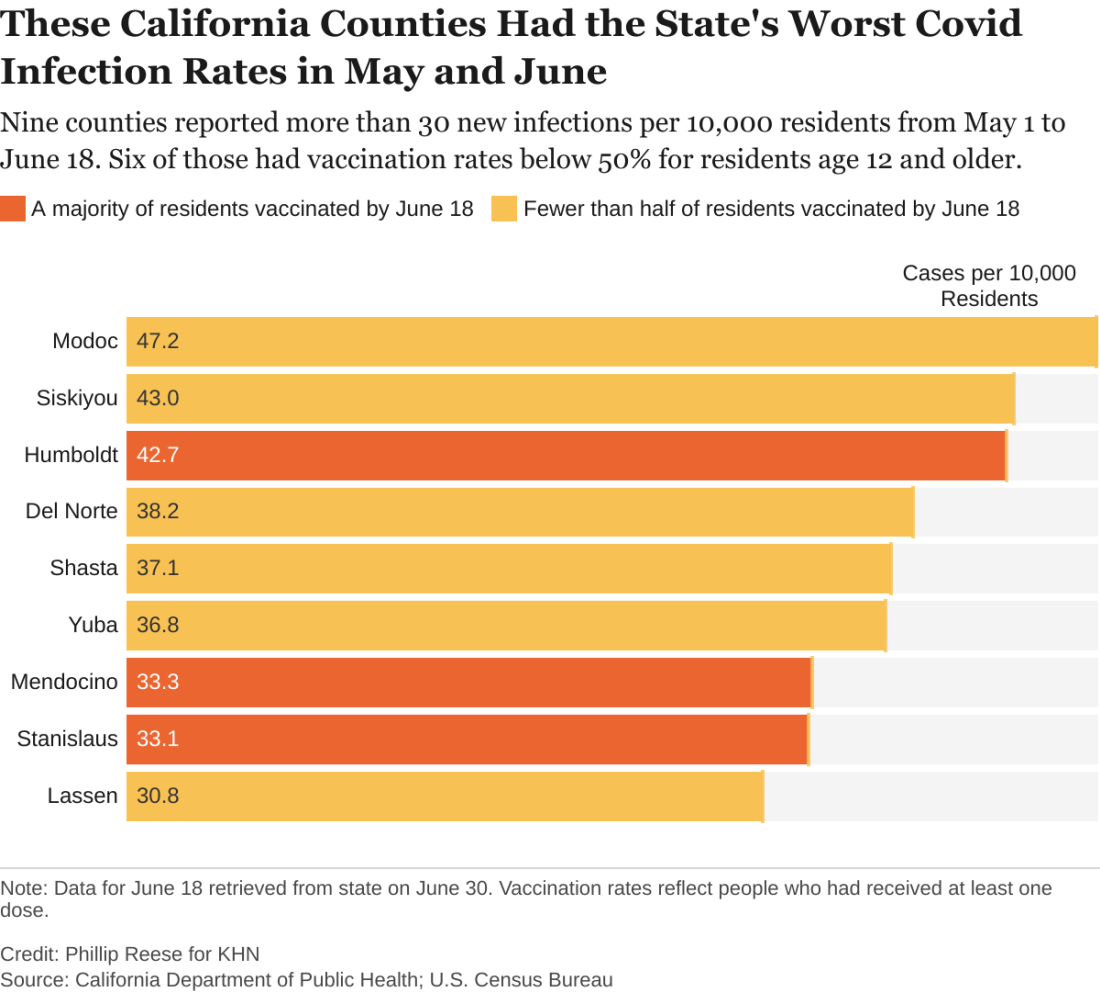

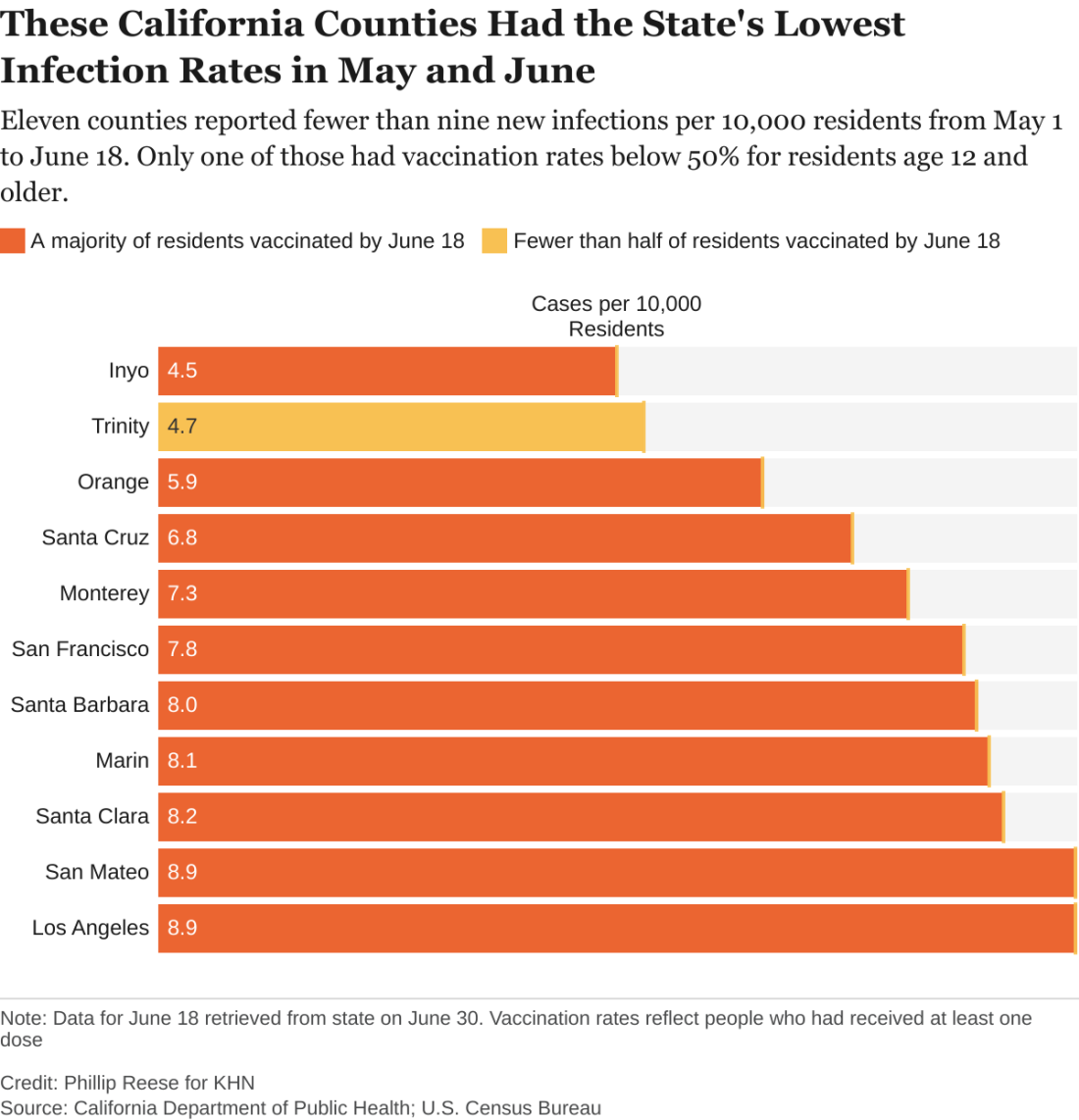

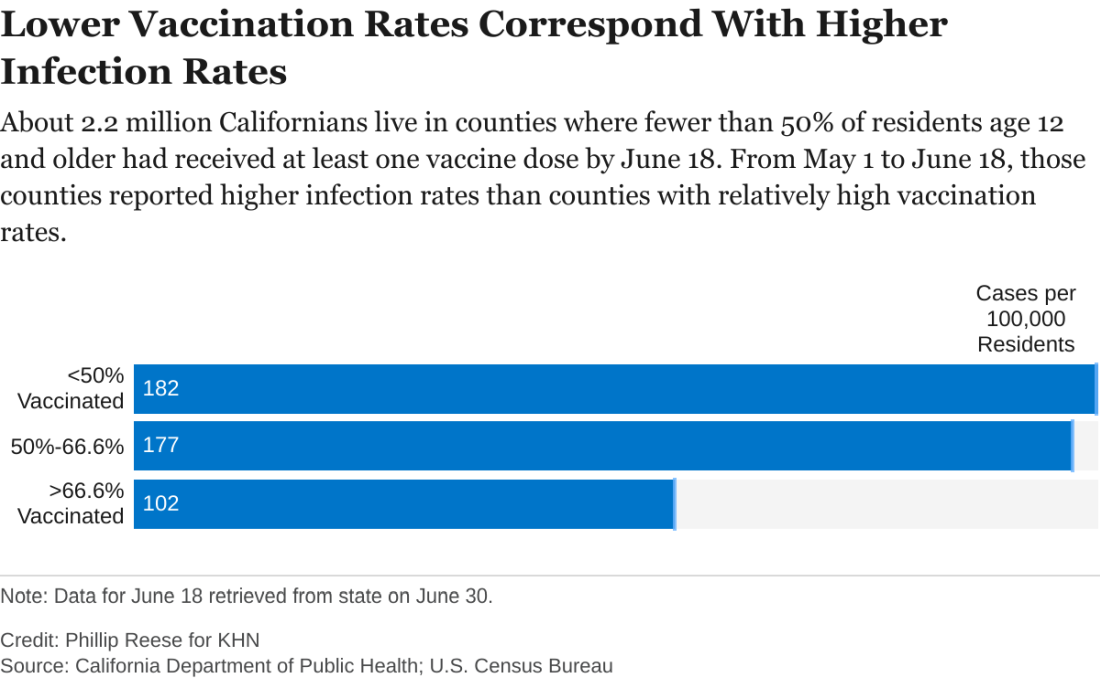

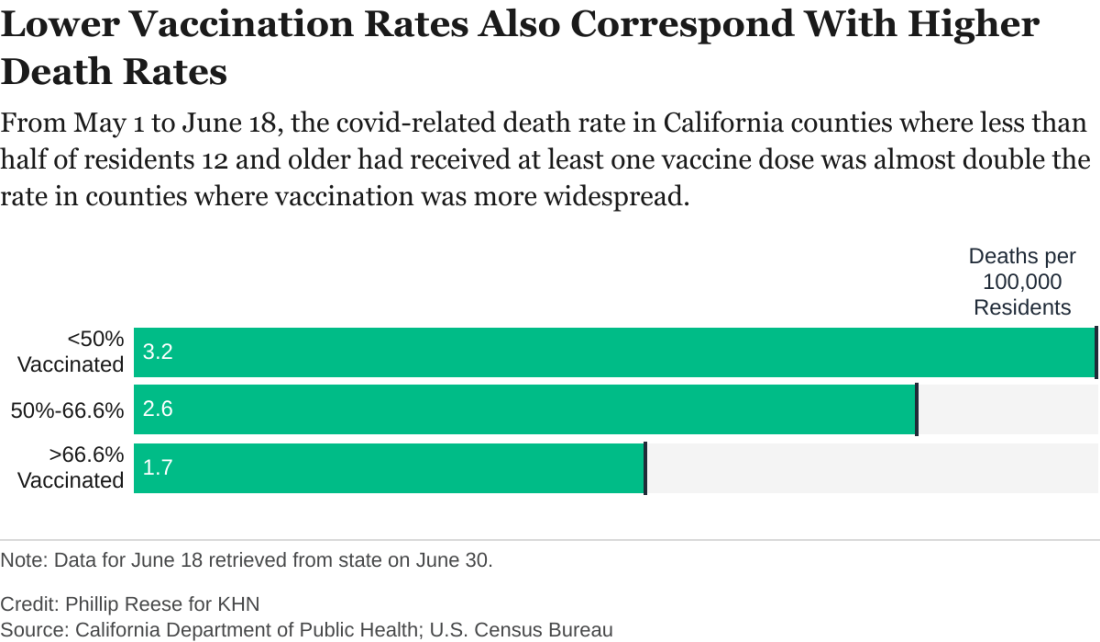

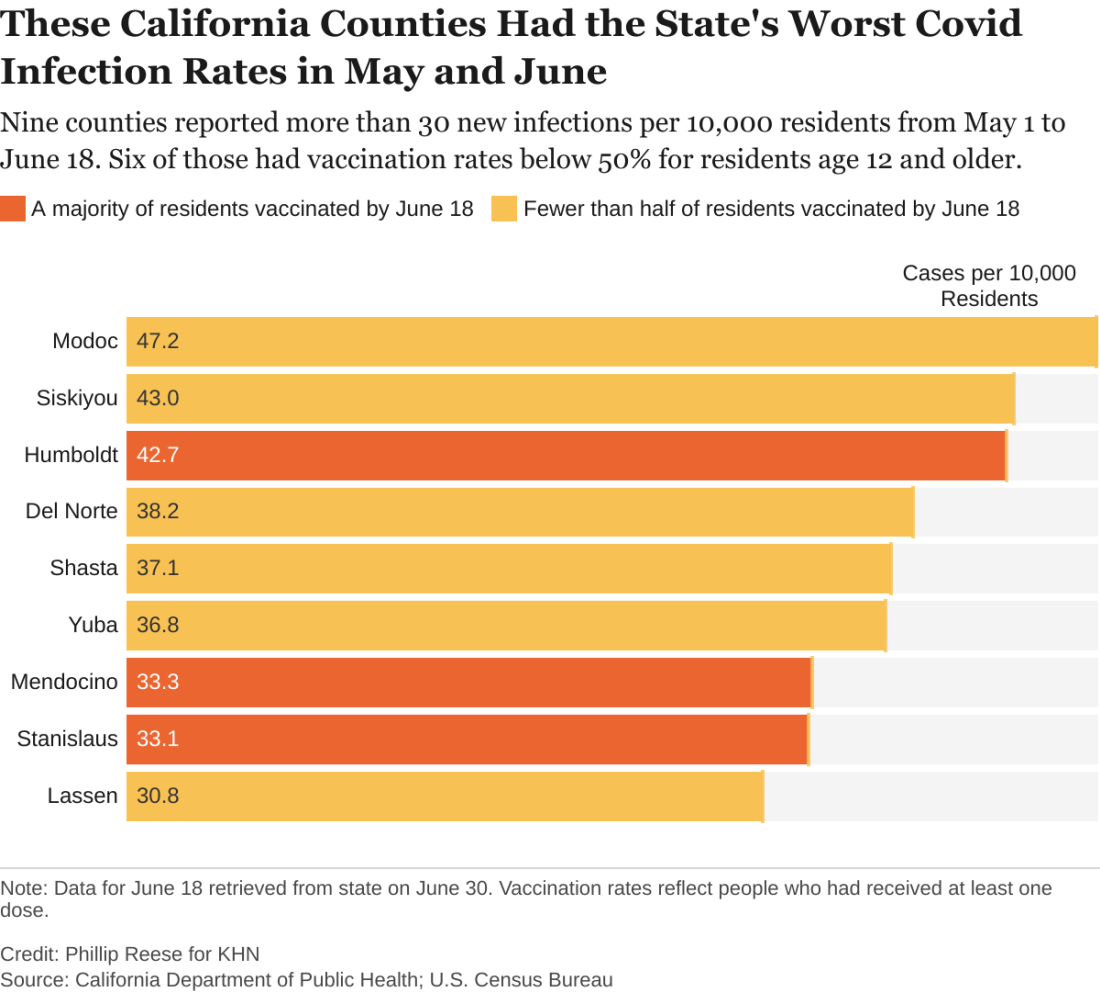

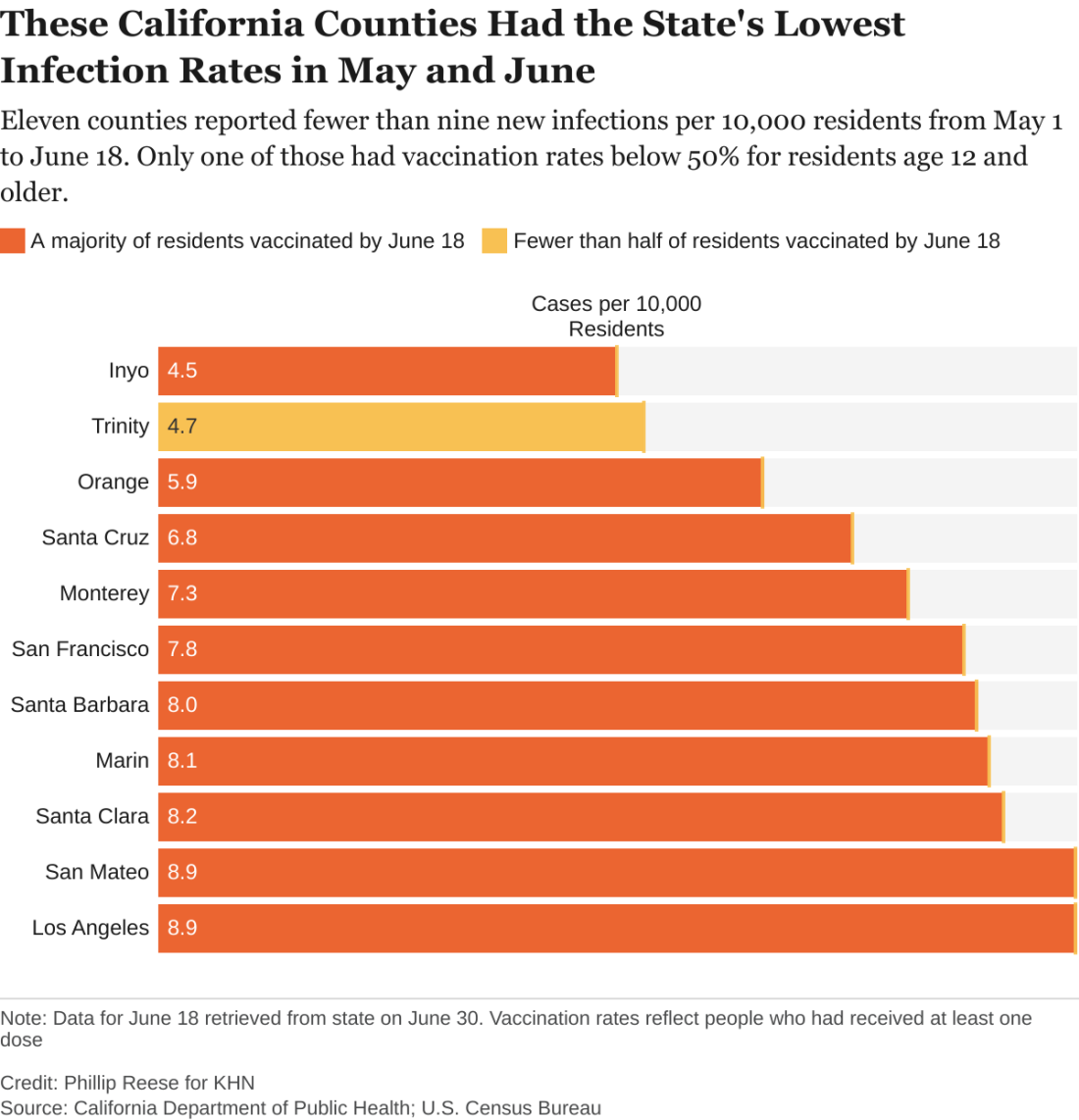

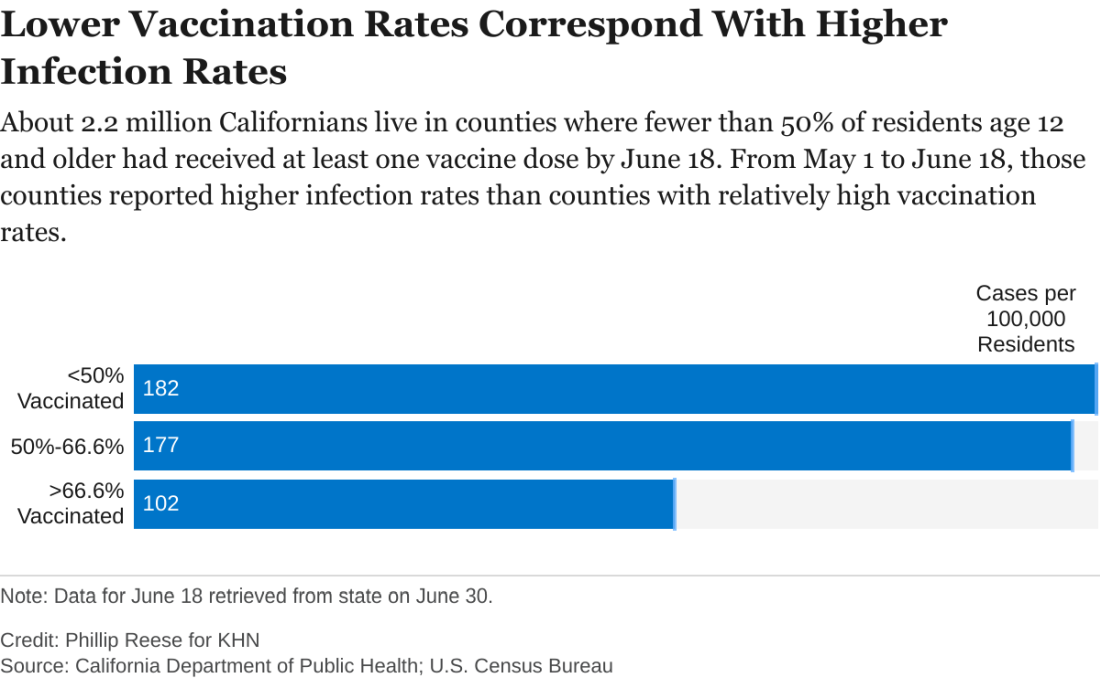

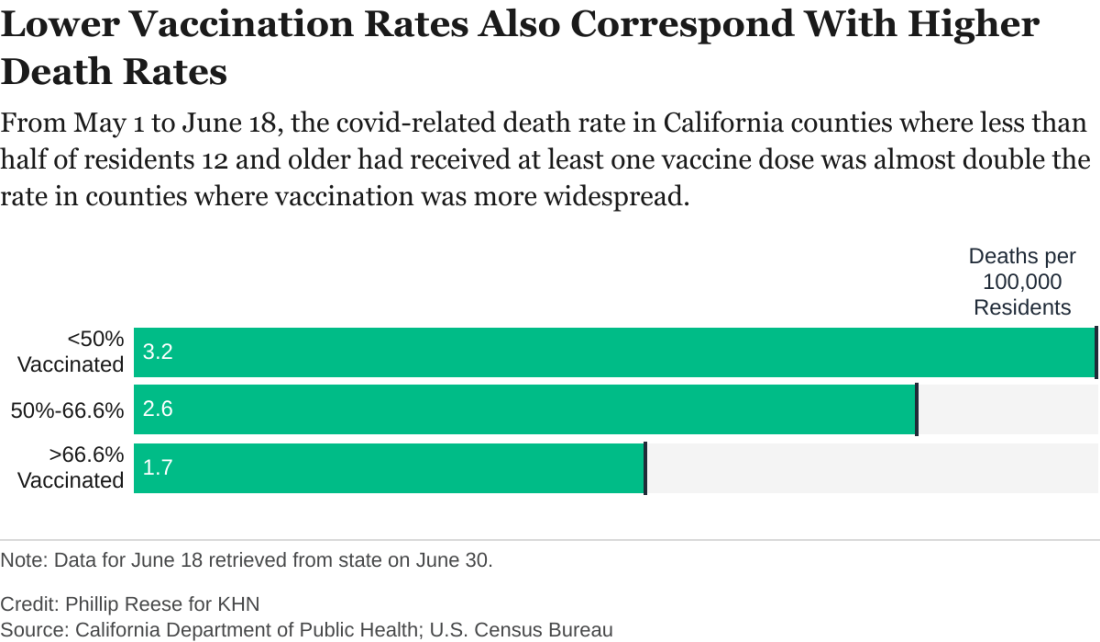

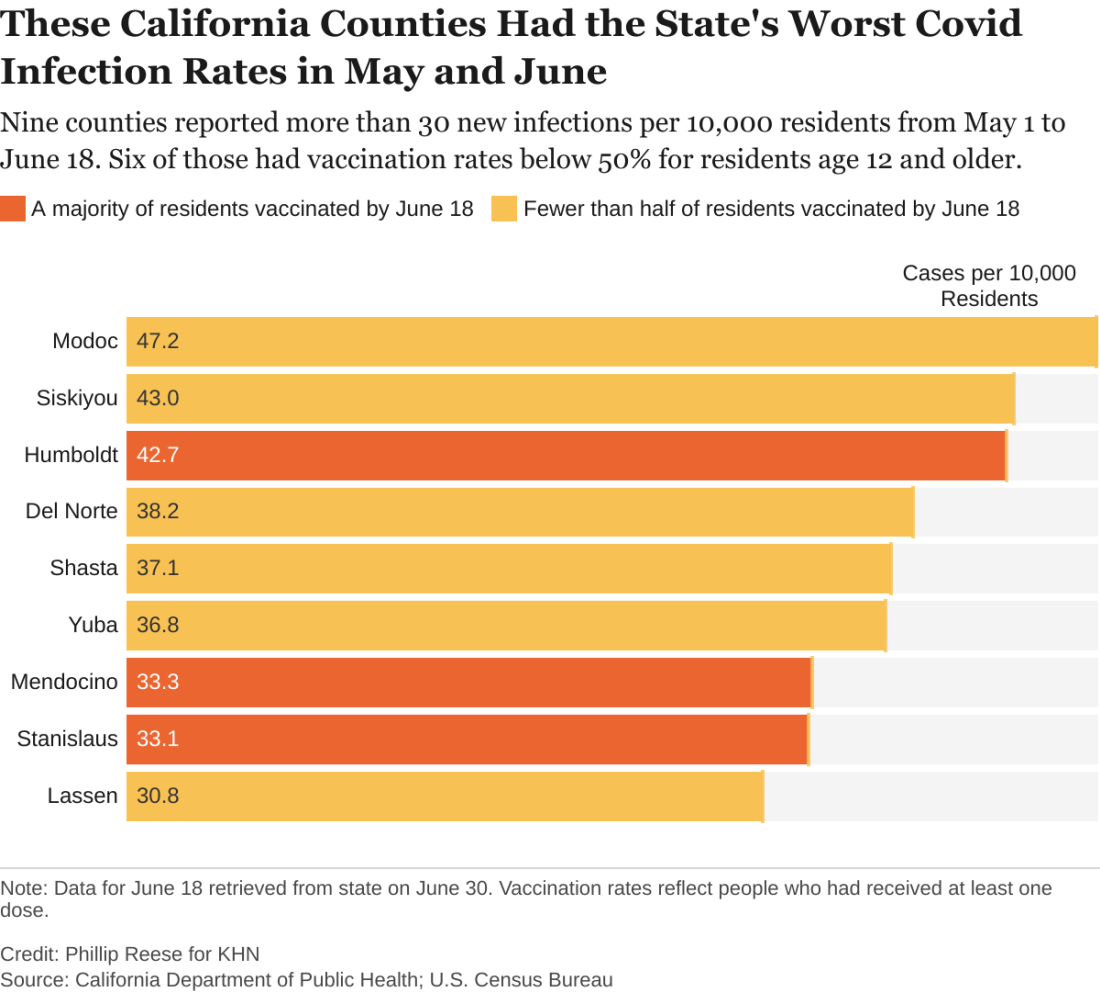

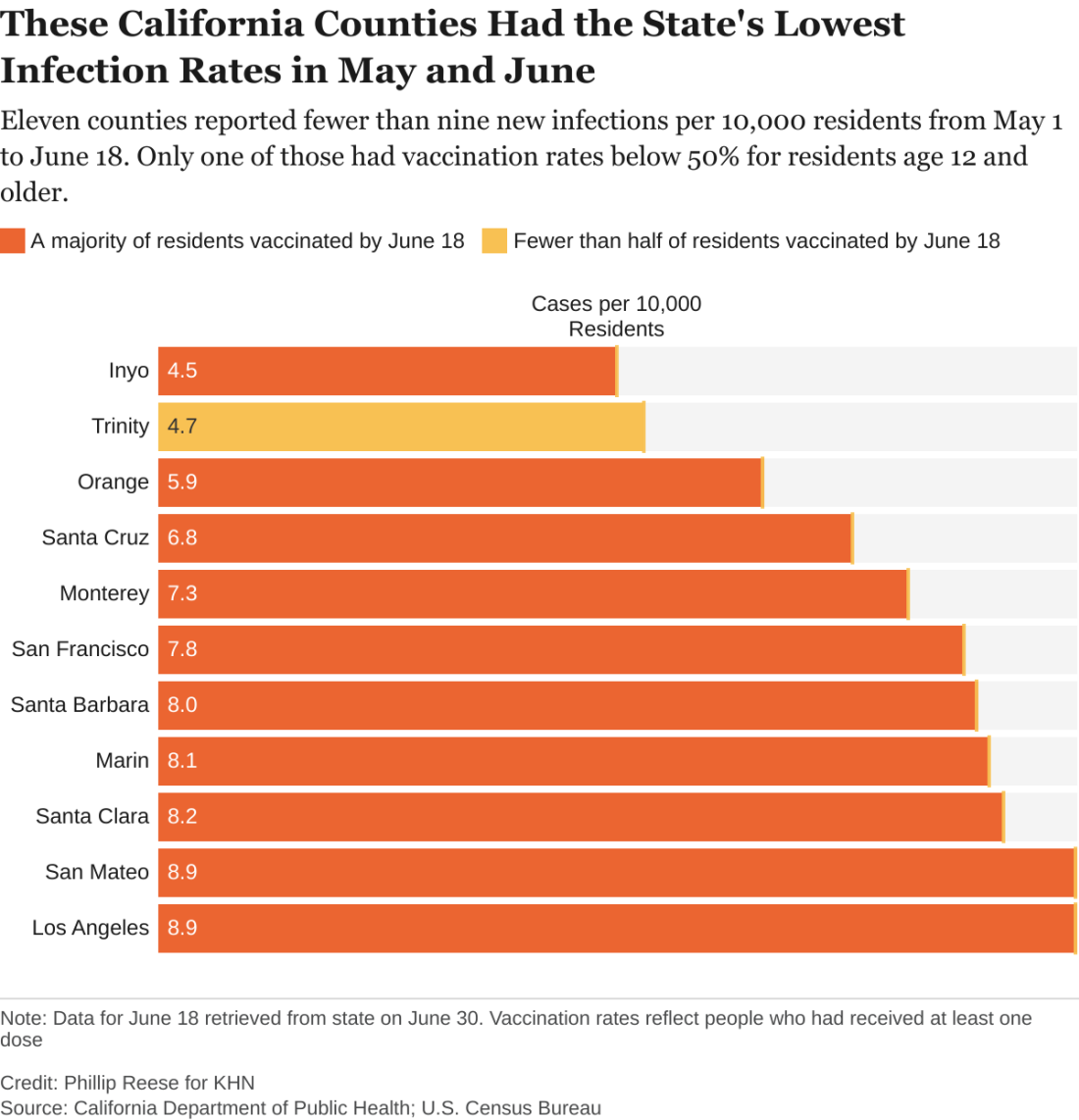

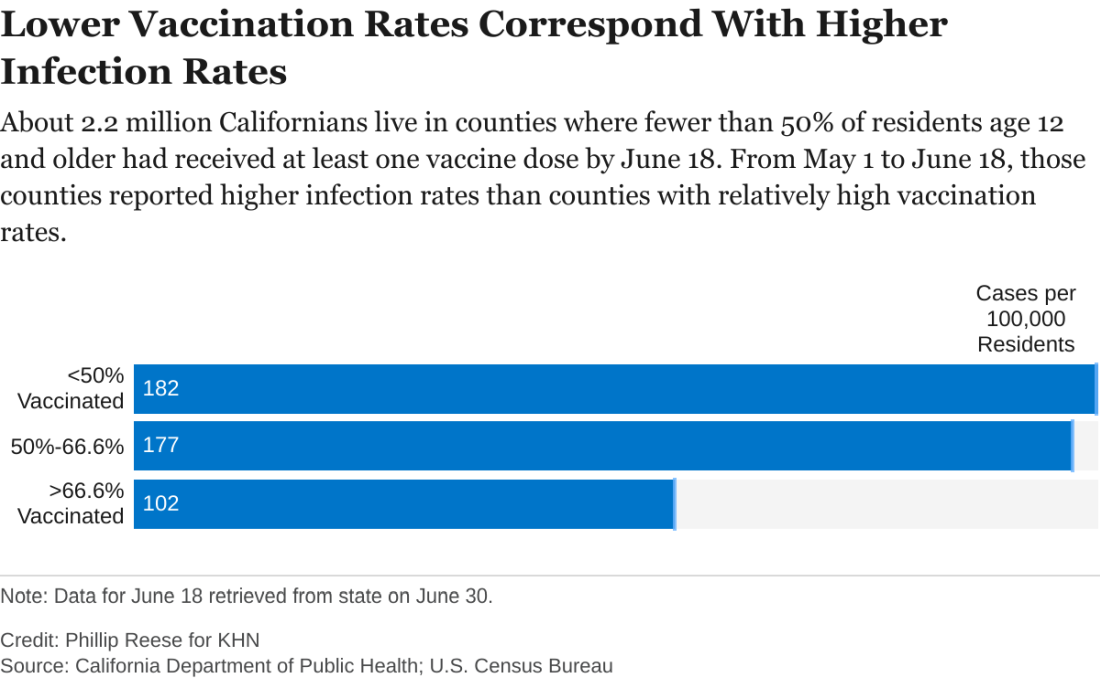

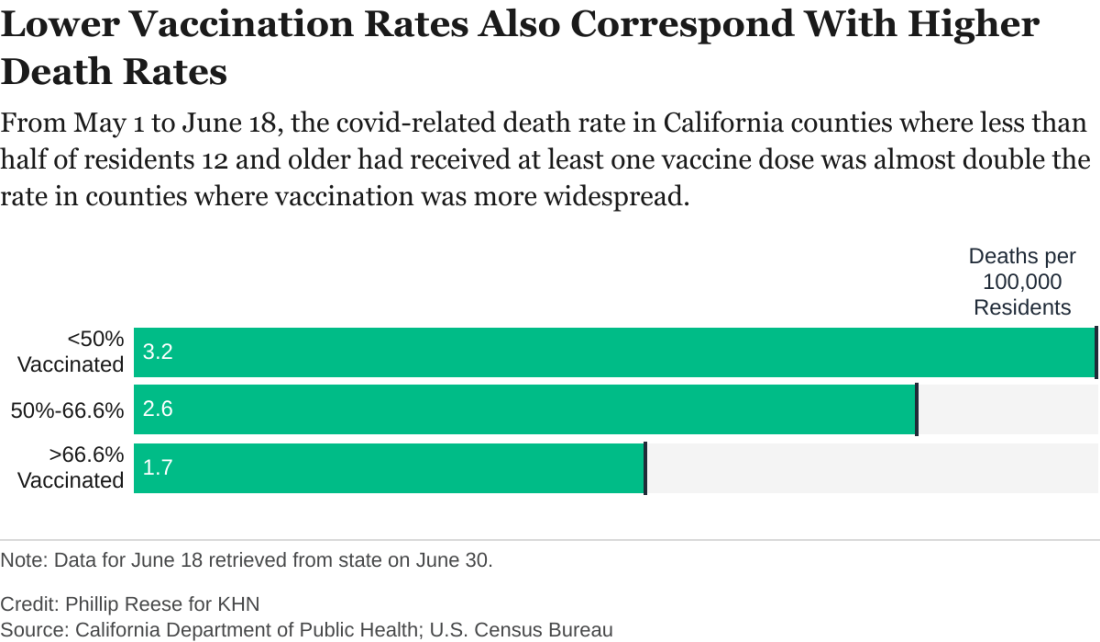

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Most of us are familiar with the good news: In recent weeks, rates of COVID-19 infection and death have plummeted in California, falling to levels not seen since the early days of the pandemic. The average number of new COVID infections reported each day dropped by an astounding 98% from December to June, according to figures from the California Department of Public Health.

And bolstering that trend, nearly 70% of Californians 12 and older are partially or fully vaccinated.

But state health officials are still reporting nearly 1,000 new COVID cases and more than 2 dozen COVID-related deaths per day. So,

An analysis of state data shows some clear patterns at this stage of the pandemic: As vaccination rates rose across the state, the overall numbers of cases and deaths plunged. But within that broader trend are pronounced regional discrepancies. Counties with relatively low rates of vaccination reported much higher rates of COVID infections and deaths in May and June than counties with high vaccination rates.

There were about 182 new COVID infections per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in California counties where fewer than half of residents age 12 and older had received at least one vaccine dose, CDPH data show. By comparison, there were about 102 COVID infections per 100,000 residents in counties where more than two-thirds of residents 12 and up had gotten at least one dose.

“If you live in an area that has low vaccination rates and you have a few people who start to develop a disease, it’s going to spread quickly among those who aren’t vaccinated,” said Rita Burke, PhD, assistant professor of clinical preventive medicine at the University of Southern California, Los Angeles. Dr. Burke noted that the highly contagious Delta variant of the coronavirus now circulating in California amplifies the threat of serious outbreaks in areas with low vaccination rates.

The regional discrepancies in COVID-related deaths are also striking. There were about 3.2 COVID-related deaths per 100,000 residents from May 1 to June 18 in counties where first-dose vaccination rates were below 50%. That is almost twice as high as the death rate in counties where more than two-thirds of residents had at least one dose.

While the pattern is clear, there are exceptions. A couple of sparsely populated mountain counties with low vaccination rates – Trinity and Mariposa – also had relatively low rates of new infections in May and June. Likewise, a few suburban counties with high vaccination rates – among them Sonoma and Contra Costa – had relatively high rates of new infections.

“There are three things that are going on,” said George Rutherford, MD, a professor of epidemiology and biostatistics at the University of California, San Francisco. “One is the vaccine – very important, but not the whole story. One is naturally acquired immunity, which is huge in some places.” A third, he said, is people still managing to evade infection, whether by taking precautions or simply by living in areas with few infections.

As of June 18, about 67% of Californians age 12 and older had received at least one dose of COVID vaccine, according to the state health department. But that masks a wide variance among the state’s 58 counties. In 14 counties, for example, fewer than half of residents 12 and older had received a shot. In 19 counties, more than two-thirds had.

The counties with low vaccination rates are largely rugged and rural. Nearly all are politically conservative. In January, about 6% of the state’s COVID infections were in the 23 counties where a majority of voters cast ballots for President Donald Trump in November. By May and June, that figure had risen to 11%.

While surveys indicate politics plays a role in vaccine hesitancy in many communities, access also remains an issue in many of California’s rural outposts. It can be hard, or at least inconvenient, for people who live far from the nearest medical facility to get two shots a month apart.

“If you have to drive 30 minutes out to the nearest vaccination site, you may not be as inclined to do that versus if it’s 5 minutes from your house,” Dr. Burke said. “And so we, the public health community, recognize that and have really made a concerted effort in order to eliminate or alleviate that access issue.”

Many of the counties with low vaccination rates had relatively low infection rates in the early months of the pandemic, largely thanks to their remoteness. But, as COVID reaches those communities, that lack of prior exposure and acquired immunity magnifies their vulnerability, Dr. Rutherford said. “We’re going to see cases where people are unvaccinated or where there’s not been a big background level of immunity already.”

As it becomes clearer that new infections will be disproportionately concentrated in areas with low vaccination rates, state officials are working to persuade hesitant Californians to get a vaccine, even introducing a vaccine lottery.

But most persuasive are friends and family members who can help counter the disinformation rampant in some communities, said Lorena Garcia, DrPH, an associate professor of epidemiology at the University of California, Davis. Belittling people for their hesitancy or getting into a political argument likely won’t work.

When talking to her own skeptical relatives, Dr. Garcia avoided politics: “I just explained any questions that they had.”

“Vaccines are a good part of our life,” she said. “It’s something that we’ve done since we were babies. So, it’s just something we’re going to do again.”

KHN (Kaiser Health News) is a national newsroom that produces in-depth journalism about health issues. Together with Policy Analysis and Polling, KHN is one of the three major operating programs at KFF (Kaiser Family Foundation). KFF is an endowed nonprofit organization providing information on health issues to the nation.

Delta becomes dominant coronavirus variant in U.S.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The contagious Delta variant has become the dominant form of the coronavirus in the United States, now accounting for more than 51% of COVID-19 cases in the country, according to new CDC data to updated on July 6.

The variant, also known as B.1.617.2 and first detected in India, makes up more than 80% of new cases in some Midwestern states, including Iowa, Kansas, and Missouri. Delta also accounts for 74% of cases in Western states such as Colorado and Utah and 59% of cases in Southern states such as Louisiana and Texas.

Communities with low vaccination rates are bearing the brunt of new Delta cases. Public health experts are urging those who are unvaccinated to get a shot to protect themselves and their communities against future surges.

“Right now we have two Americas: the vaccinated and the unvaccinated,” Paul Offit, MD, an infectious disease specialist at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, told NPR.

“We’re feeling pretty good right now because it’s the summer,” he said. “But come winter, if we still have a significant percentage of the population that is unvaccinated, we’re going to see this virus surge again.”

So far, COVID-19 vaccines appear to protect people against the Delta variant. But health officials are watching other variants that could evade vaccine protection and lead to major outbreaks this year.

For instance, certain mutations in the Epsilon variant may allow it to evade the immunity from past infections and current COVID-19 vaccines, according to a new study published July 1 in the Science. The variant, also known as B.1.427/B.1.429 and first identified in California, has now been reported in 34 countries and could become widespread in the United States.

Researchers from the University of Washington and clinics in Switzerland tested the variant in blood samples from vaccinated people, as well as those who were previously infected with COVID-19. They found that the neutralizing power was reduced by about 2 to 3½ times.

The research team also visualized the variant and found that three mutations on Epsilon’s spike protein allow the virus to escape certain antibodies and lower the strength of vaccines.

Epsilon “relies on an indirect and unusual neutralization-escape strategy,” they wrote, saying that understanding these escape routes could help scientists track new variants, curb the pandemic, and create booster shots.

In Australia, for instance, public health officials have detected the Lambda variant, which could be more infectious than the Delta variant and resistant to vaccines, according to Sky News.

A hotel quarantine program in New South Wales identified the variant in someone who had returned from travel, the news outlet reported. Also known as C.37, Lambda was named a “variant of interest” by the World Health Organization in June.

Lambda was first identified in Peru in December and now accounts for more than 80% of the country’s cases, according to the Financial Times. It has since been found in 27 countries, including the U.S., U.K., and Germany.

The variant has seven mutations on the spike protein that allow the virus to infect human cells, the news outlet reported. One mutation is like another mutation on the Delta variant, which could make it more contagious.

In a preprint study published July 1, researchers at the University of Chile at Santiago found that Lambda is better able to escape antibodies created by the CoronaVac vaccine made by Sinovac in China. In the paper, which hasn’t yet been peer-reviewed, researchers tested blood samples from local health care workers in Santiago who had received two doses of the vaccine.

“Our data revealed that the spike protein ... carries mutations conferring increased infectivity and the ability to escape from neutralizing antibodies,” they wrote.

The research team urged countries to continue testing for contagious variants, even in areas with high vaccination rates, so scientists can identify mutations quickly and analyze whether new variants can escape vaccines.

“The world has to get its act together,” Saad Omer, PhD, director of the Yale Institute for Global Health, told NPR. “Otherwise yet another, potentially more dangerous, variant could emerge.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

‘If only you knew’

Patient:

Alone in the Emergency Dept, breathless, I wait for you

“The Hospitalist will admit you” says the nurse, “she will come in a few.”

Muffled voices – masked faces bustle in & out of the room

Loud beeping machines & the rushed pace, fill me with gloom

You walk in the room, lean in to introduce

You tell me your name and what you will do

For a moment I’m more than a diagnosis, an H&P,

and then the fleeting connection passes, can’t you see?

You listen, seem hurried, but I think you care

Would you sit with me while my story I share?

Physician:

I do see you, I feel your fear & anguish

A moment to know you too, is all that I wish

How do I convince you that I truly care?

When, with all my tasks I have only minutes to spare

Patient:

You diligently ask questions from your checklist of H.P.I.,

Finalizing the diagnosis, when I hear your pager beep.

An admission awaits I know, but please sit by my side

Could we make our new-found meeting, a little more deep?

Physician:

The minute our day begins, it’s go-go-go

There isn’t a second to pause, inhale, or be slow

Missed lunch, it’s 6 p.m., bite to eat I dare?

My shift ended 3 hrs. back but I’m still here

Notes, DC summaries, calls to your PCP

Advocating for you, is more than a job to me.

Tirelessly I work, giving patients my all

Drained, exhausted yet, for you, standing tall

Our bond albeit short lived, is very important to me

Watching you get better each day, is fulfilling for me!

Patient:

You take time to ask about my family, about what I like to do

I tell you all about Beatles & my sweet grandkids

You sit & ask me “what matters most to you”

I reply: getting well for the wedding of my daughter “Sue”

Physician:

I sense loneliness engulfing you at times

Your fear and anxiety, I promise to help overcome

I will help you navigate this complex hospital stay

Together we will fight this virus or anything that comes our way

Each passing minute the line between doctor and patient disappears

That’s when we win over this virus, and hope replaces fear

Patient:

Every day you come see me, tell me my numbers are improving

I notice your warm and kind eyes behind that stifling mask

When they light up as you tell me I’m going home soon

I feel assured I mean more to you, than a mere task

Physician:

Each day I visit, together we hum “here comes the sun”

I too open up and share with you, my favorite Beatles song

Our visits cover much more than clinical medicine

True connection & mutual soul healing begins, before long.

Patient:

Today is the day, grateful to go home,

My body may be healed due to all the medicine & potions,

But my bruised soul was healed due to all your kind emotions.

Time to bid adieu Dear Doc – If I meet you at our local grocery store,

I promise I’ll remember those kind eyes, and wave

After all, you stood between me and death

I’m indebted to you, it’s my life that you did save!

Dr. Mehta is a hospitalist and director of quality and performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif. She is chair of the SHM patient experience executive council and executive board member of the SHM San Francisco Bay Area chapter.

Patient:

Alone in the Emergency Dept, breathless, I wait for you

“The Hospitalist will admit you” says the nurse, “she will come in a few.”

Muffled voices – masked faces bustle in & out of the room

Loud beeping machines & the rushed pace, fill me with gloom

You walk in the room, lean in to introduce

You tell me your name and what you will do

For a moment I’m more than a diagnosis, an H&P,

and then the fleeting connection passes, can’t you see?

You listen, seem hurried, but I think you care

Would you sit with me while my story I share?

Physician:

I do see you, I feel your fear & anguish

A moment to know you too, is all that I wish

How do I convince you that I truly care?

When, with all my tasks I have only minutes to spare

Patient:

You diligently ask questions from your checklist of H.P.I.,

Finalizing the diagnosis, when I hear your pager beep.

An admission awaits I know, but please sit by my side

Could we make our new-found meeting, a little more deep?

Physician:

The minute our day begins, it’s go-go-go

There isn’t a second to pause, inhale, or be slow

Missed lunch, it’s 6 p.m., bite to eat I dare?

My shift ended 3 hrs. back but I’m still here

Notes, DC summaries, calls to your PCP

Advocating for you, is more than a job to me.

Tirelessly I work, giving patients my all

Drained, exhausted yet, for you, standing tall

Our bond albeit short lived, is very important to me

Watching you get better each day, is fulfilling for me!

Patient:

You take time to ask about my family, about what I like to do

I tell you all about Beatles & my sweet grandkids

You sit & ask me “what matters most to you”

I reply: getting well for the wedding of my daughter “Sue”

Physician:

I sense loneliness engulfing you at times

Your fear and anxiety, I promise to help overcome

I will help you navigate this complex hospital stay

Together we will fight this virus or anything that comes our way

Each passing minute the line between doctor and patient disappears

That’s when we win over this virus, and hope replaces fear

Patient:

Every day you come see me, tell me my numbers are improving

I notice your warm and kind eyes behind that stifling mask

When they light up as you tell me I’m going home soon

I feel assured I mean more to you, than a mere task

Physician:

Each day I visit, together we hum “here comes the sun”

I too open up and share with you, my favorite Beatles song

Our visits cover much more than clinical medicine

True connection & mutual soul healing begins, before long.

Patient:

Today is the day, grateful to go home,

My body may be healed due to all the medicine & potions,

But my bruised soul was healed due to all your kind emotions.

Time to bid adieu Dear Doc – If I meet you at our local grocery store,

I promise I’ll remember those kind eyes, and wave

After all, you stood between me and death

I’m indebted to you, it’s my life that you did save!

Dr. Mehta is a hospitalist and director of quality and performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif. She is chair of the SHM patient experience executive council and executive board member of the SHM San Francisco Bay Area chapter.

Patient:

Alone in the Emergency Dept, breathless, I wait for you

“The Hospitalist will admit you” says the nurse, “she will come in a few.”

Muffled voices – masked faces bustle in & out of the room

Loud beeping machines & the rushed pace, fill me with gloom

You walk in the room, lean in to introduce

You tell me your name and what you will do

For a moment I’m more than a diagnosis, an H&P,

and then the fleeting connection passes, can’t you see?

You listen, seem hurried, but I think you care

Would you sit with me while my story I share?

Physician:

I do see you, I feel your fear & anguish

A moment to know you too, is all that I wish

How do I convince you that I truly care?

When, with all my tasks I have only minutes to spare

Patient:

You diligently ask questions from your checklist of H.P.I.,

Finalizing the diagnosis, when I hear your pager beep.

An admission awaits I know, but please sit by my side

Could we make our new-found meeting, a little more deep?

Physician:

The minute our day begins, it’s go-go-go

There isn’t a second to pause, inhale, or be slow

Missed lunch, it’s 6 p.m., bite to eat I dare?

My shift ended 3 hrs. back but I’m still here

Notes, DC summaries, calls to your PCP

Advocating for you, is more than a job to me.

Tirelessly I work, giving patients my all

Drained, exhausted yet, for you, standing tall

Our bond albeit short lived, is very important to me

Watching you get better each day, is fulfilling for me!

Patient:

You take time to ask about my family, about what I like to do

I tell you all about Beatles & my sweet grandkids

You sit & ask me “what matters most to you”

I reply: getting well for the wedding of my daughter “Sue”

Physician:

I sense loneliness engulfing you at times

Your fear and anxiety, I promise to help overcome

I will help you navigate this complex hospital stay

Together we will fight this virus or anything that comes our way

Each passing minute the line between doctor and patient disappears

That’s when we win over this virus, and hope replaces fear

Patient:

Every day you come see me, tell me my numbers are improving

I notice your warm and kind eyes behind that stifling mask

When they light up as you tell me I’m going home soon

I feel assured I mean more to you, than a mere task

Physician:

Each day I visit, together we hum “here comes the sun”

I too open up and share with you, my favorite Beatles song

Our visits cover much more than clinical medicine

True connection & mutual soul healing begins, before long.

Patient:

Today is the day, grateful to go home,

My body may be healed due to all the medicine & potions,

But my bruised soul was healed due to all your kind emotions.

Time to bid adieu Dear Doc – If I meet you at our local grocery store,

I promise I’ll remember those kind eyes, and wave

After all, you stood between me and death

I’m indebted to you, it’s my life that you did save!

Dr. Mehta is a hospitalist and director of quality and performance and patient experience at Vituity in Emeryville, Calif. She is chair of the SHM patient experience executive council and executive board member of the SHM San Francisco Bay Area chapter.

Antimicrobial resistance threat continues during COVID-19

The stark realities of antimicrobial resistance – including rising rates of difficult-to-treat infections, lack of a robust pipeline of future antimicrobials, and COVID-19 treatments that leave people more vulnerable to infections – remain urgent priorities, experts say.

For some patients, the pandemic and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are intertwined.

“One patient I’m seeing now in service really underscores how the two interact,” Vance Fowler, MD, said during a June 30 media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). A man in his mid-40s, married with a small child, developed COVID-19 in early January 2021. He was intubated, spent about 1 month in the ICU, and managed to survive.

“But since then he has been struck with a series of progressively more drug resistant bacteria,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the IDSA Antimicrobial Resistance Committee.

The patient acquired Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Although the infection initially responded to standard antibiotics, he has experienced relapses over the past few months. Through these multiple infections the Pseudomonas grew increasingly pan-resistant to treatment.

The only remaining antimicrobial agent for this patient, Dr. Fowler said, is “a case study in what we are describing ... a drug that is used relatively infrequently, that is fairly expensive, but for that particular patient is absolutely vital.”

A ‘terrifying’ personal experience

Tori Kinamon, a Duke University medical student and Food and Drug Administration antibacterial drug resistance fellow, joined Dr. Fowler at the IDSA briefing. She shared her personal journey of surviving a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, one that sparked her interest in becoming a physician.

“I had a very frightening and unexpected confrontation with antimicrobial resistance when I was a freshman in college,” Ms. Kinamon said.

A few days after competing in a Division One gymnastics championship, she felt a gradual onset of pain in her left hamstring. The pain grew acutely worse and, within days, her leg become red, swollen, and painful to the touch.

Ms. Kinamon was admitted to the hospital for suspected cellulitis and put on intravenous antibiotics.

“However, my clinical condition continued to decline,” she recalled. “Imaging studies revealed a 15-cm abscess deep in my hamstring.”

The limb- and life-threatening infection left her wondering if she would come out of surgery with both legs.

“Ultimately, I had eight surgeries in 2 weeks,” she said.

“As a 19-year-old collegiate athlete, that’s terrifying. And I never imagined that something like that would happen to me – until it did,” said Ms. Kinamon, who is an NCAA infection prevention advocate.

When Ms. Kinamon’s kidneys could no longer tolerate vancomycin, she was switched to daptomycin.

“I reflect quite frequently on how having that one extra drug in the stockpile had a significant impact on my outcome,” she said.

Incentivizing new antimicrobial agents

A lack of new antimicrobials in development is not a new story.

“There’s been a chill that’s been sustained on the antibiotic development field. Most large pharmaceutical companies have left the area of anti-infectants and the bulk of research and development is now in small pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Fowler said. “And they’re struggling.”

One potential solution is the Pasteur Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced in Congress and supported by IDSA. The bill encourages pharmaceutical companies to develop new antimicrobial agents with funding not linked to sales or use of the drugs.

Furthermore, the bill emphasizes appropriate use of these agents through effective stewardship programs.

Although some institutions shifted resources away from AMR out of necessity when COVID-19 struck, “I can say certainly from our experience at Duke that at least stewardship was alive and well. It was not relegated to the side,” Dr. Fowler said.

“In fact,” he added, “if anything, COVID really emphasized the importance of stewardship” by helping clinicians with guidance on the use of remdesivir and other antivirals during the pandemic.

Also, in some instances, treatments used to keep people with COVID-19 alive can paradoxically place them at higher risk for other infections, Dr. Fowler said, citing corticosteroids as an example.

Everyone’s concern

AMR isn’t just an issue in hospital settings, either. Ms. Kinamon reiterated that she picked up the infection in an athletic environment.

“Antimicrobial resistance is not just a problem for ICU patients in the hospital. I was the healthiest I had ever been and just very nearly escaped death due to one of these infections,” she said. ”As rates of resistance rise as these pathogens become more virulent, AMR is becoming more and more of a community threat,” she added.

Furthermore, consumers are partially to blame as well, Dr. Fowler noted.

“It’s interesting when you look at the surveys of the numbers of patients that have used someone else’s antibiotics” or leftover antimicrobial agents from a prior infection.

“It’s really startling ... that’s the sort of antibiotic overuse that directly contributes to antibacterial resistance,” he said.

Reasons for optimism

Promising advances in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention of AMRs are underway, Dr. Fowler said.

“It always gets me really excited to talk about it. It’s amazing what technology and scientific discovery can bring to this discussion and to this threat,” he said.

For example, there is a “silent revolution” in diagnostics with the aim to rapidly provide life-saving actionable data on a real patient in nearly real time.

Traditionally, “you start off by treating what should be there” while awaiting results of tests to narrow down therapy, Dr. Fowler said. However, a whole host of new platforms are in development to reduce the time to susceptibility results. This kind of technology has “the potential to transform our ability to take care of patients, giving them the right drug at the right time and no more,” he said.

Another promising avenue of research involves bacteriophages. Dr. Fowler is principal investigator on a clinical trial underway to evaluate bacteriophages as adjunct therapy for MRSA bacteremia.

When it comes to prevention on AMR infections in the future, “I continue to be optimistic about the possibility of vaccines to prevent many of these infections,” Dr. Fowler said, adding that companies are working on vaccines against these kinds of infections caused by MRSA or Escherichia coli, for example.

Patient outcomes

The man in his 40s with the multidrug resistant Pseudomonas infections “is now to the point where he’s walking in the halls and I think he’ll get out of the hospital eventually,” Dr. Fowler said.

“But his life is forever changed,” he added.

Ms. Kinamon’s recovery from MRSA included time in the ICU, 1 month in a regular hospital setting, and 5 months at home.

“It sparked my interest in antibiotic research and development because I see myself as a direct beneficiary of the stockpile of antibiotics that were available to treat my infection,” Ms. Kinamon said. “Now as a medical student working with patients who have similar infections, I feel a deep empathy and connectedness to them because they ask the same questions that I did.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The stark realities of antimicrobial resistance – including rising rates of difficult-to-treat infections, lack of a robust pipeline of future antimicrobials, and COVID-19 treatments that leave people more vulnerable to infections – remain urgent priorities, experts say.

For some patients, the pandemic and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are intertwined.

“One patient I’m seeing now in service really underscores how the two interact,” Vance Fowler, MD, said during a June 30 media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). A man in his mid-40s, married with a small child, developed COVID-19 in early January 2021. He was intubated, spent about 1 month in the ICU, and managed to survive.

“But since then he has been struck with a series of progressively more drug resistant bacteria,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the IDSA Antimicrobial Resistance Committee.

The patient acquired Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Although the infection initially responded to standard antibiotics, he has experienced relapses over the past few months. Through these multiple infections the Pseudomonas grew increasingly pan-resistant to treatment.

The only remaining antimicrobial agent for this patient, Dr. Fowler said, is “a case study in what we are describing ... a drug that is used relatively infrequently, that is fairly expensive, but for that particular patient is absolutely vital.”

A ‘terrifying’ personal experience

Tori Kinamon, a Duke University medical student and Food and Drug Administration antibacterial drug resistance fellow, joined Dr. Fowler at the IDSA briefing. She shared her personal journey of surviving a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, one that sparked her interest in becoming a physician.

“I had a very frightening and unexpected confrontation with antimicrobial resistance when I was a freshman in college,” Ms. Kinamon said.

A few days after competing in a Division One gymnastics championship, she felt a gradual onset of pain in her left hamstring. The pain grew acutely worse and, within days, her leg become red, swollen, and painful to the touch.

Ms. Kinamon was admitted to the hospital for suspected cellulitis and put on intravenous antibiotics.

“However, my clinical condition continued to decline,” she recalled. “Imaging studies revealed a 15-cm abscess deep in my hamstring.”

The limb- and life-threatening infection left her wondering if she would come out of surgery with both legs.

“Ultimately, I had eight surgeries in 2 weeks,” she said.

“As a 19-year-old collegiate athlete, that’s terrifying. And I never imagined that something like that would happen to me – until it did,” said Ms. Kinamon, who is an NCAA infection prevention advocate.

When Ms. Kinamon’s kidneys could no longer tolerate vancomycin, she was switched to daptomycin.

“I reflect quite frequently on how having that one extra drug in the stockpile had a significant impact on my outcome,” she said.

Incentivizing new antimicrobial agents

A lack of new antimicrobials in development is not a new story.

“There’s been a chill that’s been sustained on the antibiotic development field. Most large pharmaceutical companies have left the area of anti-infectants and the bulk of research and development is now in small pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Fowler said. “And they’re struggling.”

One potential solution is the Pasteur Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced in Congress and supported by IDSA. The bill encourages pharmaceutical companies to develop new antimicrobial agents with funding not linked to sales or use of the drugs.

Furthermore, the bill emphasizes appropriate use of these agents through effective stewardship programs.

Although some institutions shifted resources away from AMR out of necessity when COVID-19 struck, “I can say certainly from our experience at Duke that at least stewardship was alive and well. It was not relegated to the side,” Dr. Fowler said.

“In fact,” he added, “if anything, COVID really emphasized the importance of stewardship” by helping clinicians with guidance on the use of remdesivir and other antivirals during the pandemic.

Also, in some instances, treatments used to keep people with COVID-19 alive can paradoxically place them at higher risk for other infections, Dr. Fowler said, citing corticosteroids as an example.

Everyone’s concern

AMR isn’t just an issue in hospital settings, either. Ms. Kinamon reiterated that she picked up the infection in an athletic environment.

“Antimicrobial resistance is not just a problem for ICU patients in the hospital. I was the healthiest I had ever been and just very nearly escaped death due to one of these infections,” she said. ”As rates of resistance rise as these pathogens become more virulent, AMR is becoming more and more of a community threat,” she added.

Furthermore, consumers are partially to blame as well, Dr. Fowler noted.

“It’s interesting when you look at the surveys of the numbers of patients that have used someone else’s antibiotics” or leftover antimicrobial agents from a prior infection.

“It’s really startling ... that’s the sort of antibiotic overuse that directly contributes to antibacterial resistance,” he said.

Reasons for optimism

Promising advances in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention of AMRs are underway, Dr. Fowler said.

“It always gets me really excited to talk about it. It’s amazing what technology and scientific discovery can bring to this discussion and to this threat,” he said.

For example, there is a “silent revolution” in diagnostics with the aim to rapidly provide life-saving actionable data on a real patient in nearly real time.

Traditionally, “you start off by treating what should be there” while awaiting results of tests to narrow down therapy, Dr. Fowler said. However, a whole host of new platforms are in development to reduce the time to susceptibility results. This kind of technology has “the potential to transform our ability to take care of patients, giving them the right drug at the right time and no more,” he said.

Another promising avenue of research involves bacteriophages. Dr. Fowler is principal investigator on a clinical trial underway to evaluate bacteriophages as adjunct therapy for MRSA bacteremia.

When it comes to prevention on AMR infections in the future, “I continue to be optimistic about the possibility of vaccines to prevent many of these infections,” Dr. Fowler said, adding that companies are working on vaccines against these kinds of infections caused by MRSA or Escherichia coli, for example.

Patient outcomes

The man in his 40s with the multidrug resistant Pseudomonas infections “is now to the point where he’s walking in the halls and I think he’ll get out of the hospital eventually,” Dr. Fowler said.

“But his life is forever changed,” he added.

Ms. Kinamon’s recovery from MRSA included time in the ICU, 1 month in a regular hospital setting, and 5 months at home.

“It sparked my interest in antibiotic research and development because I see myself as a direct beneficiary of the stockpile of antibiotics that were available to treat my infection,” Ms. Kinamon said. “Now as a medical student working with patients who have similar infections, I feel a deep empathy and connectedness to them because they ask the same questions that I did.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The stark realities of antimicrobial resistance – including rising rates of difficult-to-treat infections, lack of a robust pipeline of future antimicrobials, and COVID-19 treatments that leave people more vulnerable to infections – remain urgent priorities, experts say.

For some patients, the pandemic and antimicrobial resistance (AMR) are intertwined.

“One patient I’m seeing now in service really underscores how the two interact,” Vance Fowler, MD, said during a June 30 media briefing sponsored by the Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA). A man in his mid-40s, married with a small child, developed COVID-19 in early January 2021. He was intubated, spent about 1 month in the ICU, and managed to survive.

“But since then he has been struck with a series of progressively more drug resistant bacteria,” said Dr. Fowler, professor of medicine at Duke University, Durham, N.C., and chair of the IDSA Antimicrobial Resistance Committee.

The patient acquired Pseudomonas ventilator-associated pneumonia. Although the infection initially responded to standard antibiotics, he has experienced relapses over the past few months. Through these multiple infections the Pseudomonas grew increasingly pan-resistant to treatment.

The only remaining antimicrobial agent for this patient, Dr. Fowler said, is “a case study in what we are describing ... a drug that is used relatively infrequently, that is fairly expensive, but for that particular patient is absolutely vital.”

A ‘terrifying’ personal experience

Tori Kinamon, a Duke University medical student and Food and Drug Administration antibacterial drug resistance fellow, joined Dr. Fowler at the IDSA briefing. She shared her personal journey of surviving a methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) infection, one that sparked her interest in becoming a physician.

“I had a very frightening and unexpected confrontation with antimicrobial resistance when I was a freshman in college,” Ms. Kinamon said.

A few days after competing in a Division One gymnastics championship, she felt a gradual onset of pain in her left hamstring. The pain grew acutely worse and, within days, her leg become red, swollen, and painful to the touch.

Ms. Kinamon was admitted to the hospital for suspected cellulitis and put on intravenous antibiotics.

“However, my clinical condition continued to decline,” she recalled. “Imaging studies revealed a 15-cm abscess deep in my hamstring.”

The limb- and life-threatening infection left her wondering if she would come out of surgery with both legs.

“Ultimately, I had eight surgeries in 2 weeks,” she said.

“As a 19-year-old collegiate athlete, that’s terrifying. And I never imagined that something like that would happen to me – until it did,” said Ms. Kinamon, who is an NCAA infection prevention advocate.

When Ms. Kinamon’s kidneys could no longer tolerate vancomycin, she was switched to daptomycin.

“I reflect quite frequently on how having that one extra drug in the stockpile had a significant impact on my outcome,” she said.

Incentivizing new antimicrobial agents

A lack of new antimicrobials in development is not a new story.

“There’s been a chill that’s been sustained on the antibiotic development field. Most large pharmaceutical companies have left the area of anti-infectants and the bulk of research and development is now in small pharmaceutical companies,” Dr. Fowler said. “And they’re struggling.”

One potential solution is the Pasteur Act, a bipartisan bill reintroduced in Congress and supported by IDSA. The bill encourages pharmaceutical companies to develop new antimicrobial agents with funding not linked to sales or use of the drugs.

Furthermore, the bill emphasizes appropriate use of these agents through effective stewardship programs.

Although some institutions shifted resources away from AMR out of necessity when COVID-19 struck, “I can say certainly from our experience at Duke that at least stewardship was alive and well. It was not relegated to the side,” Dr. Fowler said.

“In fact,” he added, “if anything, COVID really emphasized the importance of stewardship” by helping clinicians with guidance on the use of remdesivir and other antivirals during the pandemic.

Also, in some instances, treatments used to keep people with COVID-19 alive can paradoxically place them at higher risk for other infections, Dr. Fowler said, citing corticosteroids as an example.

Everyone’s concern

AMR isn’t just an issue in hospital settings, either. Ms. Kinamon reiterated that she picked up the infection in an athletic environment.

“Antimicrobial resistance is not just a problem for ICU patients in the hospital. I was the healthiest I had ever been and just very nearly escaped death due to one of these infections,” she said. ”As rates of resistance rise as these pathogens become more virulent, AMR is becoming more and more of a community threat,” she added.

Furthermore, consumers are partially to blame as well, Dr. Fowler noted.

“It’s interesting when you look at the surveys of the numbers of patients that have used someone else’s antibiotics” or leftover antimicrobial agents from a prior infection.

“It’s really startling ... that’s the sort of antibiotic overuse that directly contributes to antibacterial resistance,” he said.

Reasons for optimism

Promising advances in diagnostics, treatment, and prevention of AMRs are underway, Dr. Fowler said.

“It always gets me really excited to talk about it. It’s amazing what technology and scientific discovery can bring to this discussion and to this threat,” he said.

For example, there is a “silent revolution” in diagnostics with the aim to rapidly provide life-saving actionable data on a real patient in nearly real time.

Traditionally, “you start off by treating what should be there” while awaiting results of tests to narrow down therapy, Dr. Fowler said. However, a whole host of new platforms are in development to reduce the time to susceptibility results. This kind of technology has “the potential to transform our ability to take care of patients, giving them the right drug at the right time and no more,” he said.

Another promising avenue of research involves bacteriophages. Dr. Fowler is principal investigator on a clinical trial underway to evaluate bacteriophages as adjunct therapy for MRSA bacteremia.

When it comes to prevention on AMR infections in the future, “I continue to be optimistic about the possibility of vaccines to prevent many of these infections,” Dr. Fowler said, adding that companies are working on vaccines against these kinds of infections caused by MRSA or Escherichia coli, for example.

Patient outcomes

The man in his 40s with the multidrug resistant Pseudomonas infections “is now to the point where he’s walking in the halls and I think he’ll get out of the hospital eventually,” Dr. Fowler said.

“But his life is forever changed,” he added.

Ms. Kinamon’s recovery from MRSA included time in the ICU, 1 month in a regular hospital setting, and 5 months at home.

“It sparked my interest in antibiotic research and development because I see myself as a direct beneficiary of the stockpile of antibiotics that were available to treat my infection,” Ms. Kinamon said. “Now as a medical student working with patients who have similar infections, I feel a deep empathy and connectedness to them because they ask the same questions that I did.”

A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Asymptomatic C. diff carriers have increased risk of symptomatic infection

Background: C. difficile infections (CDI) are significant with more than 400,000 cases and almost 30,000 deaths annually. However, there is uncertainty regarding asymptomatic C. difficile carriers and whether they have higher rates of progression to symptomatic infections.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Large university hospital in the New York from July 2017 through March 2018.

Synopsis: Patients admitted were screened, enrolled, and tested to include an adequate sample of nursing facility residents because of prior studies that showed nursing facility residents with a higher prevalence of carriage. Patients underwent perirectal swabbing and stool swabbing if available. Test swab soilage, noted as any visible material on the swab, was noted and recorded. Two stool-testing methods were used to test for carriage. A C. difficile carrier was defined as any patient with a positive test without diarrhea. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death; 220 patients were enrolled, with 21 patients (9.6%) asymptomatic C. difficile carriers. Having a soiled swab was the only statistically significant characteristic, including previous antibiotic exposure within the past 90 days, to be associated with carriage; 8 of 21 (38.1%) carriage patients progressed to CDI within 6 months versus 4 of 199 (2.0%) noncarriage patients. Most carriers that progressed to CDI did so within 2 weeks of enrollment. Limitations included lower numbers of expected carriage patients, diarrhea diagnosing variability, and perirectal swabbing was used rather than rectal swabbing/stool testing.

Bottom line: Asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile has increased risk of progression to symptomatic CDI and could present an opportunity for screening to reduce CDI in the inpatient setting.

Citation: Baron SW et al. Screening of Clostridioides difficile carriers in an urban academic medical center: Understanding implications of disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(2):149-53.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: C. difficile infections (CDI) are significant with more than 400,000 cases and almost 30,000 deaths annually. However, there is uncertainty regarding asymptomatic C. difficile carriers and whether they have higher rates of progression to symptomatic infections.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Large university hospital in the New York from July 2017 through March 2018.

Synopsis: Patients admitted were screened, enrolled, and tested to include an adequate sample of nursing facility residents because of prior studies that showed nursing facility residents with a higher prevalence of carriage. Patients underwent perirectal swabbing and stool swabbing if available. Test swab soilage, noted as any visible material on the swab, was noted and recorded. Two stool-testing methods were used to test for carriage. A C. difficile carrier was defined as any patient with a positive test without diarrhea. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death; 220 patients were enrolled, with 21 patients (9.6%) asymptomatic C. difficile carriers. Having a soiled swab was the only statistically significant characteristic, including previous antibiotic exposure within the past 90 days, to be associated with carriage; 8 of 21 (38.1%) carriage patients progressed to CDI within 6 months versus 4 of 199 (2.0%) noncarriage patients. Most carriers that progressed to CDI did so within 2 weeks of enrollment. Limitations included lower numbers of expected carriage patients, diarrhea diagnosing variability, and perirectal swabbing was used rather than rectal swabbing/stool testing.

Bottom line: Asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile has increased risk of progression to symptomatic CDI and could present an opportunity for screening to reduce CDI in the inpatient setting.

Citation: Baron SW et al. Screening of Clostridioides difficile carriers in an urban academic medical center: Understanding implications of disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(2):149-53.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: C. difficile infections (CDI) are significant with more than 400,000 cases and almost 30,000 deaths annually. However, there is uncertainty regarding asymptomatic C. difficile carriers and whether they have higher rates of progression to symptomatic infections.

Study design: Prospective cohort study.

Setting: Large university hospital in the New York from July 2017 through March 2018.

Synopsis: Patients admitted were screened, enrolled, and tested to include an adequate sample of nursing facility residents because of prior studies that showed nursing facility residents with a higher prevalence of carriage. Patients underwent perirectal swabbing and stool swabbing if available. Test swab soilage, noted as any visible material on the swab, was noted and recorded. Two stool-testing methods were used to test for carriage. A C. difficile carrier was defined as any patient with a positive test without diarrhea. Patients were followed for 6 months or until death; 220 patients were enrolled, with 21 patients (9.6%) asymptomatic C. difficile carriers. Having a soiled swab was the only statistically significant characteristic, including previous antibiotic exposure within the past 90 days, to be associated with carriage; 8 of 21 (38.1%) carriage patients progressed to CDI within 6 months versus 4 of 199 (2.0%) noncarriage patients. Most carriers that progressed to CDI did so within 2 weeks of enrollment. Limitations included lower numbers of expected carriage patients, diarrhea diagnosing variability, and perirectal swabbing was used rather than rectal swabbing/stool testing.

Bottom line: Asymptomatic carriage of C. difficile has increased risk of progression to symptomatic CDI and could present an opportunity for screening to reduce CDI in the inpatient setting.

Citation: Baron SW et al. Screening of Clostridioides difficile carriers in an urban academic medical center: Understanding implications of disease. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2020;41(2):149-53.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Default EMR settings can influence opioid prescribing

Background: The opioid crisis is in the forefront as a public health emergency and there are concerns regarding addiction stemming from opioid prescriptions written in the acute setting, such as the ED and hospitals.

Study design: Quality improvement project, randomized.

Setting: Two large EDs in San Francisco and Oakland, Calif.

Synopsis: In five 4-week blocks, the prepopulated opioid dispense quantities were altered on a block randomized treatment schedule without prior knowledge by the prescribing practitioners with the default dispense quantities of 5, 10, 15, and null (prescriber determined dispense quantity). Opiates included oxycodone, oxycodone/acetaminophen, and hydrocodone/acetaminophen. The primary outcome was number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge from the ED. In this study, a total of 104 health care professionals issued 4,320 opioid study prescriptions. With use of linear regression, an increase of 0.19 tablets prescribed was found for each tablet increase in default quantity. When comparing default pairs – that is, 5 versus 15 tablets – a lower default was associated with a lower number of pills prescribed in more than half of the comparisons. Limitations of this study include a small sample of EDs, and local prescribing patterns can vary greatly for opioid prescriptions written. In addition, the reasons for the prescriptions were not noted.

Bottom line: Default EMR opioid quantity settings can be used to decrease the quantity of opioids prescribed.

Citation: Montoy JCC et al. Association of default electronic medical record settings with health care professional patterns of opioid prescribing in emergency departments: A randomized quality improvement study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(4):487-93.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: The opioid crisis is in the forefront as a public health emergency and there are concerns regarding addiction stemming from opioid prescriptions written in the acute setting, such as the ED and hospitals.

Study design: Quality improvement project, randomized.

Setting: Two large EDs in San Francisco and Oakland, Calif.

Synopsis: In five 4-week blocks, the prepopulated opioid dispense quantities were altered on a block randomized treatment schedule without prior knowledge by the prescribing practitioners with the default dispense quantities of 5, 10, 15, and null (prescriber determined dispense quantity). Opiates included oxycodone, oxycodone/acetaminophen, and hydrocodone/acetaminophen. The primary outcome was number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge from the ED. In this study, a total of 104 health care professionals issued 4,320 opioid study prescriptions. With use of linear regression, an increase of 0.19 tablets prescribed was found for each tablet increase in default quantity. When comparing default pairs – that is, 5 versus 15 tablets – a lower default was associated with a lower number of pills prescribed in more than half of the comparisons. Limitations of this study include a small sample of EDs, and local prescribing patterns can vary greatly for opioid prescriptions written. In addition, the reasons for the prescriptions were not noted.

Bottom line: Default EMR opioid quantity settings can be used to decrease the quantity of opioids prescribed.

Citation: Montoy JCC et al. Association of default electronic medical record settings with health care professional patterns of opioid prescribing in emergency departments: A randomized quality improvement study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(4):487-93.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Background: The opioid crisis is in the forefront as a public health emergency and there are concerns regarding addiction stemming from opioid prescriptions written in the acute setting, such as the ED and hospitals.

Study design: Quality improvement project, randomized.

Setting: Two large EDs in San Francisco and Oakland, Calif.

Synopsis: In five 4-week blocks, the prepopulated opioid dispense quantities were altered on a block randomized treatment schedule without prior knowledge by the prescribing practitioners with the default dispense quantities of 5, 10, 15, and null (prescriber determined dispense quantity). Opiates included oxycodone, oxycodone/acetaminophen, and hydrocodone/acetaminophen. The primary outcome was number of opioid tablets prescribed at discharge from the ED. In this study, a total of 104 health care professionals issued 4,320 opioid study prescriptions. With use of linear regression, an increase of 0.19 tablets prescribed was found for each tablet increase in default quantity. When comparing default pairs – that is, 5 versus 15 tablets – a lower default was associated with a lower number of pills prescribed in more than half of the comparisons. Limitations of this study include a small sample of EDs, and local prescribing patterns can vary greatly for opioid prescriptions written. In addition, the reasons for the prescriptions were not noted.

Bottom line: Default EMR opioid quantity settings can be used to decrease the quantity of opioids prescribed.

Citation: Montoy JCC et al. Association of default electronic medical record settings with health care professional patterns of opioid prescribing in emergency departments: A randomized quality improvement study. JAMA Intern Med. 2020;180(4):487-93.

Dr. Wang is a hospitalist and associate professor of medicine at University of Texas Health, San Antonio.

Clinician practices to connect with patients

Background: As technology and medical advances improve patient care, physicians and patients have become more dissatisfied with their interactions and relationships. Practices are needed to improve the connection between physician and patient.

Study design: Mixed-methods.

Setting: Three diverse primary care settings (academic medical center, Veterans Affairs facility, federally qualified health center).

Synopsis: Initial evidence- and narrative-based practices were identified from a systematic literature review, clinical observations of primary care encounters, and qualitative discussions with physicians, patients, and nonmedical professionals. A three-round modified Delphi process was performed with experts representing different aspects of the patient-physician relationship.

Five recommended clinical practices were recognized to foster presence and meaningful connections with patients: 1. Prepare with intention (becoming familiar with the patient before you meet them); 2. Listen intently and completely (sit down, lean forward, and don’t interrupt, but listen); 3. Agree on what matters most (discover your patient’s goals and fit them into the visit); 4. Connect with the patient’s story (take notice of efforts by the patient and successes); 5. Explore emotional cues (be aware of your patient’s emotions). Limitations of this study include the use of convenience sampling for the qualitative research, lack of international diversity of the expert panelists, and the lack of validation of the five practices as a whole.

Bottom line: The five practices of prepare with intention, listen intently and completely, agree on what matters most, connect with the patient’s story, and explore emotional cues may improve the patient-physician connection.

Citation: Zulman DM et al. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323(1):70-81.