User login

-

COVID-19 vaccine supply will be limited at first, ACIP says

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) yesterday held its third meeting this summer to discuss the vaccines and plan how initial vaccines will be allocated, inasmuch as supplies will likely be limited at first. Vaccines are expected to be more available as production ramps up and as more than one vaccine become available, but vaccine allocation initially will need to take place in phases.

Considerations include first getting the vaccine to individuals who need it the most, such as healthcare personnel and essential workers, as well as those at higher risk for severe illness or death, including the elderly, those with underlying conditions, and certain racial and ethnic minorities. Other factors include storage requirements that might be difficult to meet in certain settings and the fact that both vaccines must be given in two doses.

Vaccine allocation models

The group presented two possible models for allocating initial vaccine supplies.

The first population model considers risk status within each age group on the basis of underlying health conditions and occupational group, with priority given to healthcare personnel (paid or unpaid) and essential workers. The model considers partial reopening and social distancing, expected vaccine efficacy, prevaccination immunity, mortality, and the direct and indirect benefits of vaccination.

In this model, COVID-19 infections and deaths were reduced when healthcare personnel, essential workers, or adults with underlying conditions were vaccinated. There were smaller differences between the groups with respect to the impact of vaccination. Declines in infections were “more modest” and declines in deaths were greater when adults aged 65 years and older were vaccinated in comparison with other age groups.

The second model focused on vaccination of nursing home healthcare personnel and residents. Vaccinating nursing home healthcare personnel reduced infections and deaths more than vaccinating nursing home residents.

In settings such as long-term care facilities and correction facilities, where people gather in groups, cases increase first among staff. The vaccine working group suggests that vaccinating staff may also benefit individuals living in those facilities.

The working group expects that from 15 to 45 million doses of vaccine will be available by the end of December, depending on which vaccine is approved by then or whether both are approved.

Supplies won’t be nearly enough to vaccinate everyone: There are approximately 17 to 20 million healthcare workers in the United States and 60 to 80 million essential workers who do not work in healthcare. More than 100 million adults have underlying medical conditions that put them at higher risk for hospitalization and death, such as obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. And approximately 53 million adults are aged 65 years or older.

The group reviewed promising early data for two vaccines under development.

The mRNA-1273 vaccine, made by Moderna with support from two federal agencies, is moving into phase 3 clinical trials – enrollment into the COVID-19 Efficacy and Safety (COVE) study is ongoing, according to Jacqueline M. Miller, MD, senior vice president and therapeutic area head of infectious diseases. The study’s primary objective will be to determine whether two doses can prevent symptomatic COVID-19, according to an NIH news release.

A second mRNA vaccine, BNT 162b2, made by Pfizer and BioNTech, is entering phase 2/3 trials. Nearly 20% of people enrolled are Black or Hispanic persons, and 4% are Asian persons. The team is also trying to recruit Native American participants, Nicholas Kitchin, MD, senior director in Pfizer’s vaccine clinical research and development group, said in a presentation to the advisory committee.

‘Ultra-cold’ temperatures required for storage

Both vaccines require storage at lower temperatures than is usually needed for vaccines. One vaccine must be distributed and stored at -20° C, and the other must be stored, distributed, and handled at -70° C.

This issue stands out most to ACIP Chair Jose Romero, MD. He says the “ultra-cold” temperatures required for storage and transportation of the vaccines will be a “significant problem” for those in rural areas.

High-risk populations such as meat processors and agricultural workers “may have to wait until we have a more stable vaccine that can be transported and delivered more or less at room temperature,” Romero explained. He is the chief medical officer at the Arkansas Department of Health and is a professor of pediatrics and pediatric infectious diseases at the University of Arkansas for Medical Sciences, both in Little Rock.

The advisory committee will meet again on September 22. At that time, they’ll vote on an interim plan for prioritization of the first COVID-19 vaccine.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Immunotherapy should not be withheld because of sex, age, or PS

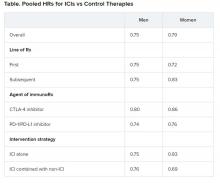

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

The improvement in survival in many cancer types that is seen with immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs), when compared to control therapies, is not affected by the patient’s sex, age, or Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group (ECOG) performance status (PS), according to a new meta-analysis.

Therefore, treatment with these immunotherapies should not be withheld on the basis of these factors, the authors concluded.

Asked whether there have been such instances of withholding ICIs, lead author Yucai Wang, MD, PhD, Mayo Clinic, Rochester, Minnesota, told Medscape Medical News: “We did this study solely based on scientific questions we had and not because we were seeing any bias at the moment in the use of ICIs.

“And we saw that the survival benefits were very similar across all of the categories [we analyzed], with a survival benefit of about 20% from immunotherapy across the board, which is clinically meaningful,” he added.

The study was published online August 7 in JAMA Network Open.

“The comparable survival advantage between patients of different sex, age, and ECOG PS may encourage more patients to receive ICI treatment regardless of cancer types, lines of therapy, agents of immunotherapy, and intervention therapies,” the authors commented.

Wang noted that there have been conflicting reports in the literature suggesting that male patients may benefit more from immunotherapy than female patients and that older patients may benefit more from the same treatment than younger patients.

However, there are also suggestions in the literature that women experience a stronger immune response than men and that, with aging, the immune system generally undergoes immunosenescence.

In addition, the PS of oncology patients has been implicated in how well patients respond to immunotherapy.

Wang noted that the findings of past studies have contradicted each other.

Findings of the Meta-Analysis

The meta-analysis included 37 randomized clinical trials that involved a total of 23,760 patients with a variety of advanced cancers. “Most of the trials were phase 3 (n = 34) and conduced for subsequent lines of therapy (n = 22),” the authors explained.

The most common cancers treated with an ICI were non–small cell lung cancer and melanoma.

Pooled overall survival (OS) hazard ratios (HRs) were calculated on the basis of sex, age (younger than 65 years and 65 years and older), and an ECOG PS of 0 and 1 or higher.

Responses were stratified on the basis of cancer type, line of therapy, the ICI used, and the immunotherapy strategy used in the ICI arm.

Most of the drugs evaluated were PD-1 and PD-L1 inhibitors. The specific drugs assessed included ipilimumab, tremelimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, atezolizumab, durvalumab, and avelumab.

A total of 32 trials that involved more than 20,000 patients reported HRs for death according to the patients’ sex. Thirty-four trials that involved more than 21,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ age, and 30 trials that involved more than 19,000 patients reported HRs for death according to patients’ ECOG PS.

No significant differences in OS benefit were seen by cancer type, line of therapy, agent of immunotherapy, or intervention strategy, the investigators pointed out.

There were also no differences in survival benefit associated with immunotherapy vs control therapies for patients with an ECOG PS of 0 and an ECOG PS of 1 or greater. The OS benefit was 0.81 for those with an ECOG PS of 0 and 0.79 for those with an ECOG PS of 1 or greater.

Wang has disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com .

Age, other risk factors predict length of MM survival

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

Younger age of onset and the use of autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant (ASCT) treatment were key factors improving the length of survival of newly diagnosed, active multiple myeloma (MM) patients, according to the results of a retrospective analysis.

In addition, multivariable analysis showed that a higher level of blood creatinine, the presence of extramedullary disease, a lower level of partial remission, and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation were independent risk factors for shorter survival, according to Virginia Bove, MD, of the Asociación Espanola Primera en Socorros Mutuos, Montevideo, Uruguay and colleagues.

Dr. Bove and colleagues retrospectively analyzed clinical characteristics, response to treatment, and survival of 282 patients from multiple institutions who had active newly-diagnosed multiple myeloma. They compared the results between patients age 65 years or younger (53.2%) with those older than 65 years and assessed clinical risk factors, as reported online in Hematology, Transfusion, and Cell Therapy.

The main cause of death in all patients was MM progression and the early mortality rate was not different between the younger and older patients. The main cause of early death in older patients was infection, according to the researchers.

Multiple risk factors

“Although MM patients younger than 66 years of age have an aggressive presentation with an advanced stage, high rate of renal failure and extramedullary disease, this did not translate into an inferior [overall survival] and [progression-free survival],” the researchers reported.

The overall response rate was similar between groups (80.6% vs. 81.4%; P = .866), and the overall survival was significantly longer in young patients (median, 65 months vs. 41 months; P = .001) and higher in those who received autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation.

Multivariate analysis was performed on data from the younger patients. The results showed that a creatinine level of less than or equal to 2 mg/dL (P = .048), extramedullary disease (P = .001), a lower VGPR (P = .003) and the use of nonautologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (P = .048) were all independent risk factors for shorter survival.

“Older age is an independent adverse prognostic factor. Adequate risk identification, frontline treatment based on novel drugs and ASCT are the best strategies to improve outcomes, both in young and old patients,” the researchers concluded.

The authors reported that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Bove V et al. Hematol Transfus Cell Ther. 2020 Aug 20. doi: 10.1016/j.htct.2020.06.014.

FROM HEMATOLOGY, TRANSFUSION, AND CELL THERAPY

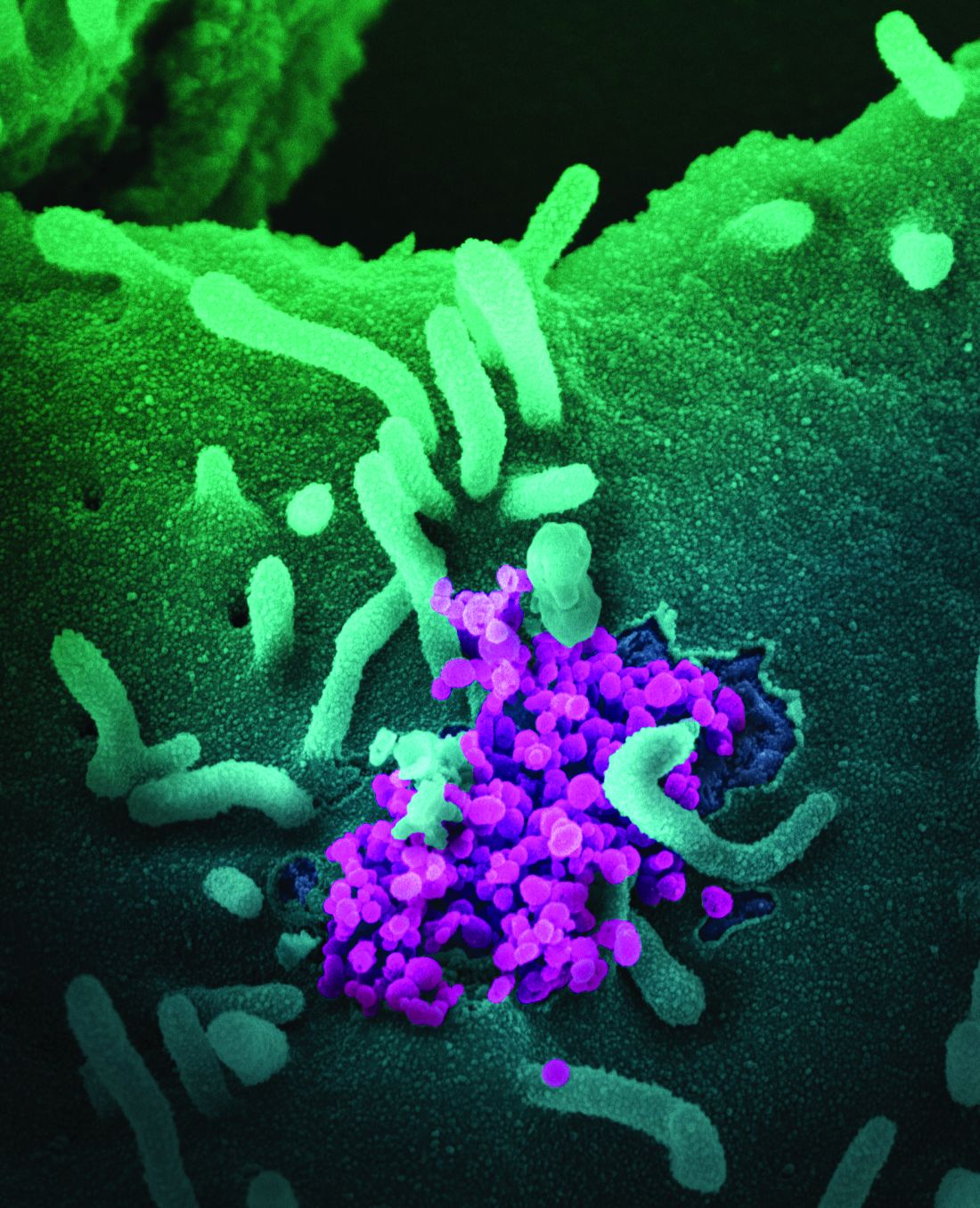

Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections in kids tied to local rates

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

As communities wrestle with the decision to send children back to school or opt for distance learning, a key question is how many children are likely to have asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infections.

“The strong association between prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 in children who are asymptomatic and contemporaneous weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population ... provides a simple means for institutions to estimate local pediatric asymptomatic prevalence from the publicly available Johns Hopkins University database,” researchers say in an article published online August 25 in JAMA Pediatrics.

Ana Marija Sola, BS, a researcher at the University of California, San Francisco, and colleagues examined the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection among 33,041 children who underwent routine testing in April and May when hospitals resumed elective medical and surgical care. The hospitals performed reverse transcription–polymerase chain reaction tests for SARS-CoV-2 RNA before surgery, clinic visits, or hospital admissions. Pediatric otolaryngologists reported the prevalence data through May 29 as part of a quality improvement project.

In all, 250 patients tested positive for the virus, for an overall prevalence of 0.65%. Across 25 geographic areas, the prevalence ranged from 0% to 2.2%. By region, prevalence was highest in the Northeast, at 0.90%, and the Midwest, at 0.87%; prevalence was lower in the West, at 0.59%, and the South, at 0.52%.

To get a sense of how those rates compared with overall rates in the same geographic areas, the researchers used the Johns Hopkins University confirmed cases database to calculate the average weekly incidence of COVID-19 for the entire population for each geographic area.

“Asymptomatic pediatric prevalence was significantly associated with weekly incidence of COVID-19 in the general population during the 6-week period over which most testing of individuals without symptoms occurred,” Ms. Sola and colleagues reported. An analysis using additional data from 11 geographic areas demonstrated that this association persisted at a later time point.

The study provides “another window on the question of how likely is it that an asymptomatic child will be carrying coronavirus,” said Susan E. Coffin, MD, MPH, an attending physician for the division of infectious diseases at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. However, important related questions remain, said Dr. Coffin, who was not involved with the study.

For one, it is unclear how many children remain asymptomatic in comparison with those who were in a presymptomatic phase at the time of testing. And importantly, “what proportion of these children are infectious?” said Dr. Coffin. “There is some data to suggest that children with asymptomatic infection may be less infectious than children with symptomatic infection.”

It also could be that patients seen at children’s hospitals differ from the general pediatric population. “What does this look like if you do the exact same study in a group of randomly selected children, not children who are queueing up to have a procedure? ... And what do these numbers look like now that stay-at-home orders have been lifted?” Dr. Coffin asked.

Further studies are needed to establish that detection of COVID-19 in the general population is predictive of the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 infection in asymptomatic children, Dr. Coffin said.

The authors have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Aspirin may accelerate cancer progression in older adults

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

Aspirin may accelerate the progression of advanced cancers and lead to an earlier death as a result, new data from the ASPREE study suggest.

The results showed that patients 65 years and older who started taking daily low-dose aspirin had a 19% higher chance of being diagnosed with metastatic cancer, a 22% higher chance of being diagnosed with a stage 4 tumor, and a 31% increased risk of death from stage 4 cancer, when compared with patients who took a placebo.

John J. McNeil, MBBS, PhD, of Monash University in Melbourne, Australia, and colleagues detailed these findings in the Journal of the National Cancer Institute.

“If confirmed, the clinical implications of these findings could be important for the use of aspirin in an older population,” the authors wrote.

When results of the ASPREE study were first reported in 2018, they “raised important concerns,” Ernest Hawk, MD, and Karen Colbert Maresso wrote in an editorial related to the current publication.

“Unlike ARRIVE, ASCEND, and nearly all prior primary prevention CVD [cardiovascular disease] trials of aspirin, ASPREE surprisingly demonstrated increased all-cause mortality in the aspirin group, which appeared to be driven largely by an increase in cancer-related deaths,” wrote the editorialists, who are both from the University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center in Houston.

Even though the ASPREE investigators have now taken a deeper dive into their data, the findings “neither explain nor alleviate the concerns raised by the initial ASPREE report,” the editorialists noted.

ASPREE design and results

ASPREE is a multicenter, double-blind trial of 19,114 older adults living in Australia (n = 16,703) or the United States (n = 2,411). Most patients were 70 years or older at baseline. However, the U.S. group also included patients 65 years and older who were racial/ethnic minorities (n = 564).

Patients were randomized to receive 100 mg of enteric-coated aspirin daily (n = 9,525) or matching placebo (n = 9,589) from March 2010 through December 2014.

At inclusion, all participants were free from cardiovascular disease, dementia, or physical disability. A previous history of cancer was not used to exclude participants, and 19.1% of patients had cancer at randomization. Most patients (89%) had not used aspirin regularly before entering the trial.

At a median follow-up of 4.7 years, there were 981 incident cancer events in the aspirin-treated group and 952 in the placebo-treated group, with an overall incident cancer rate of 10.1%.

Of the 1,933 patients with newly diagnosed cancer, 65.7% had a localized cancer, 18.8% had a new metastatic cancer, 5.8% had metastatic disease from an existing cancer, and 9.7% had a new hematologic or lymphatic cancer.

A quarter of cancer patients (n = 495) died as a result of their malignancy, with 52 dying from a cancer they already had at randomization.

Aspirin was not associated with the risk of first incident cancer diagnosis or incident localized cancer diagnosis. The hazard ratios were 1.04 for all incident cancers (95% confidence interval, 0.95-1.14) and 0.99 for incident localized cancers (95% CI, 0.89-1.11).

However, aspirin was associated with an increased risk of metastatic cancer and cancer presenting at stage 4. The HR for metastatic cancer was 1.19 (95% CI, 1.00-1.43), and the HR for newly diagnosed stage 4 cancer was 1.22 (95% CI, 1.02-1.45).

Furthermore, “an increased progression to death was observed amongst those randomized to aspirin, regardless of whether the initial cancer presentation had been localized or metastatic,” the investigators wrote.

The HRs for death were 1.35 for all cancers (95% CI, 1.13-1.61), 1.47 for localized cancers (95% CI, 1.07-2.02), and 1.30 for metastatic cancers (95% CI, 1.03-1.63).

“Deaths were particularly high among those on aspirin who were diagnosed with advanced solid cancers,” study author Andrew Chan, MD, of Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, said in a press statement.

Indeed, HRs for death in patients with solid tumors presenting at stage 3 and 4 were a respective 2.11 (95% CI, 1.03-4.33) and 1.31 (95% CI, 1.04-1.64). This suggests a possible adverse effect of aspirin on the growth of cancers once they have already developed in older adults, Dr. Chan said.

Where does that leave aspirin for cancer prevention?

“Although these results suggest that we should be cautious about starting aspirin therapy in otherwise healthy older adults, this does not mean that individuals who are already taking aspirin – particularly if they began taking it at a younger age – should stop their aspirin regimen,” Dr. Chan said.

There are decades of data supporting the use of daily aspirin to prevent multiple cancer types, particularly colorectal cancer, in individuals under the age of 70 years. In a recent meta-analysis, for example, regular aspirin use was linked to a 27% reduced risk for colorectal cancer, a 33% reduced risk for squamous cell esophageal cancer, a 39% decreased risk for adenocarcinoma of the esophagus and gastric cardia, a 36% decreased risk for stomach cancer, a 38% decreased risk for hepatobiliary tract cancer, and a 22% decreased risk for pancreatic cancer.

While these figures are mostly based on observational and case-control studies, it “reaffirms the fact that, overall, when you look at all of the ages, that there is still a benefit of aspirin for cancer,” John Cuzick, PhD, of Queen Mary University of London (England), said in an interview.

In fact, the meta-analysis goes as far as suggesting that perhaps the dose of aspirin being used is too low, with the authors noting that there was a 35% risk reduction in colorectal cancer with a dose of 325 mg daily. That’s a new finding, Dr. Cuzick said.

He noted that the ASPREE study largely consists of patients 70 years of age or older, and the authors “draw some conclusions which we can’t ignore about potential safety.”

One of the safety concerns is the increased risk for gastrointestinal bleeding, which is why Dr. Cuzick and colleagues previously recommended caution in the use of aspirin to prevent cancer in elderly patients. The group published a study in 2015 that suggested a benefit of taking aspirin daily for 5-10 years in patients aged 50-65 years, but the risk/benefit ratio was unclear for patients 70 years and older.

The ASPREE data now add to those uncertainties and suggest “there may be some side effects that we do not understand,” Dr. Cuzick said.

“I’m still optimistic that aspirin is going to be important for cancer prevention, but probably focusing on ages 50-70,” he added. “[The ASPREE data] reinforce the caution that we have to take in terms of trying to understand what the side effects are and what’s going on at these older ages.”

Dr. Cuzick is currently leading the AsCaP Project, an international effort to better understand why aspirin might work in preventing some cancer types but not others. AsCaP is supported by Cancer Research UK and also includes Dr. Chan among the researchers attempting to find out which patients may benefit the most from aspirin and which may be at greater risk of adverse effects.

The ASPREE trial was funded by grants from the National Institute on Aging, the National Cancer Institute, the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia, Monash University, and the Victorian Cancer Agency. Several ASPREE investigators disclosed financial relationships with Bayer Pharma. The editorialists had no conflicts of interest. Dr. Cuzick has been an advisory board member for Bayer in the past.

SOURCE: McNeil J et al. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2020 Aug 11. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djaa114.

FROM JOURNAL OF THE NATIONAL CANCER INSTITUTE

Convalescent plasma actions spark trial recruitment concerns

The agency’s move took many investigators by surprise. The EUA was announced at the White House the day after President Donald J. Trump accused the FDA of delaying approval of therapeutics to hurt his re-election chances.

In a memo describing the decision, the FDA cited data from some controlled and uncontrolled studies and, primarily, data from an open-label expanded-access protocol overseen by the Mayo Clinic.

At the White House, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said that plasma had been found to save the lives of 35 out of every 100 who were treated. That figure was later found to have been erroneous, and many experts pointed out that Hahn had conflated an absolute risk reduction with a relative reduction. After a firestorm of criticism, Hahn issued an apology.

“The criticism is entirely justified,” he tweeted. “What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

About 15 randomized controlled trials – out of 54 total studies involving convalescent plasma – are underway in the United States, according to ClinicalTrials.gov. The FDA’s Aug. 23 emergency authorization gave clinicians wide leeway to employ convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The agency noted, however, that “adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.”

But it’s not clear that people with COVID-19, especially those who are severely ill and hospitalized, will choose to enlist in a clinical trial – where they could receive a placebo – when they instead could get plasma.

“I’ve been asked repeatedly whether the EUA will affect our ability to recruit people into our hospitalized patient trial,” said Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, FIDSA, chief of the department of medicine, infectious diseases division at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. “I do not know,” she said, on a call with reporters organized by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“But,” she said, “I do know that the trial will continue and that we will discuss the evidence that we have with our patients and give them all that we can to help them weigh the evidence and make up their minds.”

Pirofski said the study being conducted at Montefiore and four other sites has since late April enrolled 190 patients out of a hoped-for 300.

When the study – which compares convalescent plasma to saline in hospitalized patients – was first designed, “there was not any funding for our trial and honestly not a whole lot of interest,” Pirofski told reporters. Individual donors helped support the initial rollout in late April and the trial quickly enrolled 150 patients as the pandemic peaked in the New York City area.

The National Institutes of Health has since given funding, which allowed the study to expand to New York University, Yale University, the University of Miami, and the University of Texas at Houston.

Hopeful, but a long way to go

Shmuel Shoham, MD, FIDSA, associate director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that he’s hopeful that people will continue to enroll in his trial, which is seeking to determine if plasma can prevent COVID-19 in those who’ve been recently exposed.

“Volunteers joining the study is the only way that we’re going to get to know whether this stuff works for prevention and treatment,” Shoham said on the call. He urged physicians and other healthcare workers to talk with patients about considering trial participation.

Shoham’s study is being conducted at 30 US sites and one at the Navajo Nation. It has enrolled 25 out of a hoped-for 500 participants. “We have a long way to go,” said Shoham.

Another Hopkins study to determine whether plasma is helpful in shortening illness in nonhospitalized patients, which is being conducted at the same 31 sites, has enrolled 50 out of 600.

Shoham said recruiting patients with COVID for any study had proven to be difficult. “The vast majority of people that have coronavirus do not come to centers that do clinical trials or interventional trials,” he said, adding that, in addition, most of those “who have coronavirus don’t want to be in a trial. They just want to have coronavirus and get it over with.”

But it’s important to understand how to conduct trials in a pandemic – in part to get answers quickly, he said. Researchers have been looking at convalescent plasma for months, said Shoham. “Why don’t we have the randomized clinical trial data that we want?”

Pirofski noted that trials have also been hobbled in part by “the shifting areas of the pandemic.” Fewer cases make for fewer potential plasma donors.

Both Shoham and Pirofski also said that more needed to be done to encourage plasma donors to participate.

The US Department of Health & Human Services clarified in August that hospitals, physicians, health plans, and other health care workers could contact individuals who had recovered from COVID-19 without violating the HIPAA privacy rule.

Pirofski said she believes that trial investigators know it is legal to reach out to patients. But, she said, “it probably could be better known.”

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The agency’s move took many investigators by surprise. The EUA was announced at the White House the day after President Donald J. Trump accused the FDA of delaying approval of therapeutics to hurt his re-election chances.

In a memo describing the decision, the FDA cited data from some controlled and uncontrolled studies and, primarily, data from an open-label expanded-access protocol overseen by the Mayo Clinic.

At the White House, FDA Commissioner Stephen Hahn, MD, said that plasma had been found to save the lives of 35 out of every 100 who were treated. That figure was later found to have been erroneous, and many experts pointed out that Hahn had conflated an absolute risk reduction with a relative reduction. After a firestorm of criticism, Hahn issued an apology.

“The criticism is entirely justified,” he tweeted. “What I should have said better is that the data show a relative risk reduction not an absolute risk reduction.”

About 15 randomized controlled trials – out of 54 total studies involving convalescent plasma – are underway in the United States, according to ClinicalTrials.gov. The FDA’s Aug. 23 emergency authorization gave clinicians wide leeway to employ convalescent plasma in patients hospitalized with COVID-19.

The agency noted, however, that “adequate and well-controlled randomized trials remain necessary for a definitive demonstration of COVID-19 convalescent plasma efficacy and to determine the optimal product attributes and appropriate patient populations for its use.”

But it’s not clear that people with COVID-19, especially those who are severely ill and hospitalized, will choose to enlist in a clinical trial – where they could receive a placebo – when they instead could get plasma.

“I’ve been asked repeatedly whether the EUA will affect our ability to recruit people into our hospitalized patient trial,” said Liise-anne Pirofski, MD, FIDSA, chief of the department of medicine, infectious diseases division at Albert Einstein College of Medicine and Montefiore Medical Center in the Bronx, New York. “I do not know,” she said, on a call with reporters organized by the Infectious Diseases Society of America.

“But,” she said, “I do know that the trial will continue and that we will discuss the evidence that we have with our patients and give them all that we can to help them weigh the evidence and make up their minds.”

Pirofski said the study being conducted at Montefiore and four other sites has since late April enrolled 190 patients out of a hoped-for 300.

When the study – which compares convalescent plasma to saline in hospitalized patients – was first designed, “there was not any funding for our trial and honestly not a whole lot of interest,” Pirofski told reporters. Individual donors helped support the initial rollout in late April and the trial quickly enrolled 150 patients as the pandemic peaked in the New York City area.

The National Institutes of Health has since given funding, which allowed the study to expand to New York University, Yale University, the University of Miami, and the University of Texas at Houston.

Hopeful, but a long way to go

Shmuel Shoham, MD, FIDSA, associate director of the transplant and oncology infectious diseases center at Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine in Baltimore, said that he’s hopeful that people will continue to enroll in his trial, which is seeking to determine if plasma can prevent COVID-19 in those who’ve been recently exposed.

“Volunteers joining the study is the only way that we’re going to get to know whether this stuff works for prevention and treatment,” Shoham said on the call. He urged physicians and other healthcare workers to talk with patients about considering trial participation.

Shoham’s study is being conducted at 30 US sites and one at the Navajo Nation. It has enrolled 25 out of a hoped-for 500 participants. “We have a long way to go,” said Shoham.

Another Hopkins study to determine whether plasma is helpful in shortening illness in nonhospitalized patients, which is being conducted at the same 31 sites, has enrolled 50 out of 600.

Shoham said recruiting patients with COVID for any study had proven to be difficult. “The vast majority of people that have coronavirus do not come to centers that do clinical trials or interventional trials,” he said, adding that, in addition, most of those “who have coronavirus don’t want to be in a trial. They just want to have coronavirus and get it over with.”

But it’s important to understand how to conduct trials in a pandemic – in part to get answers quickly, he said. Researchers have been looking at convalescent plasma for months, said Shoham. “Why don’t we have the randomized clinical trial data that we want?”

Pirofski noted that trials have also been hobbled in part by “the shifting areas of the pandemic.” Fewer cases make for fewer potential plasma donors.

Both Shoham and Pirofski also said that more needed to be done to encourage plasma donors to participate.