User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Guidelines for radiotherapy in prostate cancer during the pandemic

The framework involves using remote visits via telemedicine, avoiding radiotherapy in applicable cases, deferring radiotherapy as appropriate, and shortening the fractionation schedule of treatment based on safety and efficacy parameters.

Nicholas G. Zaorsky, MD, of Penn State Cancer Institute in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and colleagues described the framework and recommendations in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

The authors systematically reviewed the body of literature for evidence pertaining to the safe use of telemedicine, avoidance or deferral of radiotherapy, and optimal use of androgen deprivation therapy for patients with prostate cancer. The team also reviewed best practices for patients undergoing radiotherapy based on disease risk.

Based on their findings, Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended that, during the pandemic, all consultations and return visits become telehealth visits. “Very few prostate cancer patients require an in-person visit during a pandemic,” the authors wrote.

Lower-risk disease

Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended avoiding radiotherapy in patients with very-low-, low-, and favorable intermediate-risk disease. The authors said data suggest that, in general, treatment can be safely deferred in these patients “until after pandemic-related restrictions have been lifted.” However, this recommendation presumes the pandemic will wane over the next 12 months.

“I reassure my patients with very-low- and low-risk prostate cancer that the preferred, evidence-based treatment for patients in these categories is active surveillance,” said study author Amar U. Kishan, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“If surveillance is an option, then delaying treatment must be reasonable [during the pandemic],” he added. “For favorable intermediate-risk disease, I [review] the data supporting this approach and discuss that short delays are very unlikely to compromise outcomes.”

Higher-risk disease

The authors recommended deferral of radiotherapy for 4-6 months in patients with higher-risk disease, which includes those with unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, very-high-risk, clinical node-positive, oligometastatic, and low-volume M1 disease, as well as patients who have undergone prostatectomy.

The authors noted that in-person consultations and return visits should be converted to “timely remote telehealth visits” for these patients. After these patients have started treatment, androgen deprivation therapy “can allow for further deferral of radiotherapy as necessary based on the nature of the ongoing epidemic.”

In cases where radiotherapy cannot be deferred safely, “the shortest fractionation schedule should be adopted that has evidence of safety and efficacy,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that these recommendations are only applicable to patients not infected with COVID-19. In cases of suspected or confirmed COVID-19, local institutional policies and practices should be followed.

The authors further explained that, due to the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal guidelines should be followed when made available.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Zaorsky NG et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.010.

The framework involves using remote visits via telemedicine, avoiding radiotherapy in applicable cases, deferring radiotherapy as appropriate, and shortening the fractionation schedule of treatment based on safety and efficacy parameters.

Nicholas G. Zaorsky, MD, of Penn State Cancer Institute in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and colleagues described the framework and recommendations in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

The authors systematically reviewed the body of literature for evidence pertaining to the safe use of telemedicine, avoidance or deferral of radiotherapy, and optimal use of androgen deprivation therapy for patients with prostate cancer. The team also reviewed best practices for patients undergoing radiotherapy based on disease risk.

Based on their findings, Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended that, during the pandemic, all consultations and return visits become telehealth visits. “Very few prostate cancer patients require an in-person visit during a pandemic,” the authors wrote.

Lower-risk disease

Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended avoiding radiotherapy in patients with very-low-, low-, and favorable intermediate-risk disease. The authors said data suggest that, in general, treatment can be safely deferred in these patients “until after pandemic-related restrictions have been lifted.” However, this recommendation presumes the pandemic will wane over the next 12 months.

“I reassure my patients with very-low- and low-risk prostate cancer that the preferred, evidence-based treatment for patients in these categories is active surveillance,” said study author Amar U. Kishan, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“If surveillance is an option, then delaying treatment must be reasonable [during the pandemic],” he added. “For favorable intermediate-risk disease, I [review] the data supporting this approach and discuss that short delays are very unlikely to compromise outcomes.”

Higher-risk disease

The authors recommended deferral of radiotherapy for 4-6 months in patients with higher-risk disease, which includes those with unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, very-high-risk, clinical node-positive, oligometastatic, and low-volume M1 disease, as well as patients who have undergone prostatectomy.

The authors noted that in-person consultations and return visits should be converted to “timely remote telehealth visits” for these patients. After these patients have started treatment, androgen deprivation therapy “can allow for further deferral of radiotherapy as necessary based on the nature of the ongoing epidemic.”

In cases where radiotherapy cannot be deferred safely, “the shortest fractionation schedule should be adopted that has evidence of safety and efficacy,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that these recommendations are only applicable to patients not infected with COVID-19. In cases of suspected or confirmed COVID-19, local institutional policies and practices should be followed.

The authors further explained that, due to the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal guidelines should be followed when made available.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Zaorsky NG et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.010.

The framework involves using remote visits via telemedicine, avoiding radiotherapy in applicable cases, deferring radiotherapy as appropriate, and shortening the fractionation schedule of treatment based on safety and efficacy parameters.

Nicholas G. Zaorsky, MD, of Penn State Cancer Institute in Hershey, Pennsylvania, and colleagues described the framework and recommendations in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

The authors systematically reviewed the body of literature for evidence pertaining to the safe use of telemedicine, avoidance or deferral of radiotherapy, and optimal use of androgen deprivation therapy for patients with prostate cancer. The team also reviewed best practices for patients undergoing radiotherapy based on disease risk.

Based on their findings, Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended that, during the pandemic, all consultations and return visits become telehealth visits. “Very few prostate cancer patients require an in-person visit during a pandemic,” the authors wrote.

Lower-risk disease

Dr. Zaorsky and colleagues recommended avoiding radiotherapy in patients with very-low-, low-, and favorable intermediate-risk disease. The authors said data suggest that, in general, treatment can be safely deferred in these patients “until after pandemic-related restrictions have been lifted.” However, this recommendation presumes the pandemic will wane over the next 12 months.

“I reassure my patients with very-low- and low-risk prostate cancer that the preferred, evidence-based treatment for patients in these categories is active surveillance,” said study author Amar U. Kishan, MD, of the University of California, Los Angeles.

“If surveillance is an option, then delaying treatment must be reasonable [during the pandemic],” he added. “For favorable intermediate-risk disease, I [review] the data supporting this approach and discuss that short delays are very unlikely to compromise outcomes.”

Higher-risk disease

The authors recommended deferral of radiotherapy for 4-6 months in patients with higher-risk disease, which includes those with unfavorable intermediate-risk, high-risk, very-high-risk, clinical node-positive, oligometastatic, and low-volume M1 disease, as well as patients who have undergone prostatectomy.

The authors noted that in-person consultations and return visits should be converted to “timely remote telehealth visits” for these patients. After these patients have started treatment, androgen deprivation therapy “can allow for further deferral of radiotherapy as necessary based on the nature of the ongoing epidemic.”

In cases where radiotherapy cannot be deferred safely, “the shortest fractionation schedule should be adopted that has evidence of safety and efficacy,” the authors wrote.

They acknowledged that these recommendations are only applicable to patients not infected with COVID-19. In cases of suspected or confirmed COVID-19, local institutional policies and practices should be followed.

The authors further explained that, due to the rapidly evolving nature of the COVID-19 pandemic, state and federal guidelines should be followed when made available.

The authors reported having no conflicts of interest. No funding sources were reported.

SOURCE: Zaorsky NG et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi: 10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.010.

FROM ADVANCES IN RADIATION ONCOLOGY

First report of MM patient successfully treated for COVID-19 with tocilizumab

Recent research has shown that severe cases of COVID-19 show an excessive immune response and a strong cytokine storm, which may include high levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GSF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Following up on that research, investigators from China reported the first case of COVID-19 in a patient with multiple myeloma (MM) who was successfully treated with the humanized anti–IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab (an off-label use in the United States). The exceptional case report was published online in Blood Advances, an American Society of Hematology journal.

A 60-year-old man working in Wuhan, China, developed chest tightness without fever and cough on Feb. 1, 2020, and was admitted immediately after computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest showed multiple ground-glass opacities and pneumatocele located in both subpleural spaces. He received 400 mg of moxifloxacin IV daily for 3 days while swab specimens were collected and tested by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. A positive result for SARS-CoV-2 infection was received 3 days later. The patient was subsequently given 200-mg umifenovir (Arbidol) tablets orally, three times daily, for antiviral treatment.

The patient had a history of symptomatic MM, which was diagnosed in 2015. The patient received two cycles of induction chemotherapy consisting of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, and his symptoms completely disappeared. After that, he received thalidomide for maintenance.

Chest CT imaging on hospital day 8 showed that the bilateral, multiple ground-glass opacities from the first scan remained, and laboratory investigations revealed a high level of serum IL-6. On hospital day 9, the patient was given a single, one-time dose of 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, administered by IV. On hospital day 12, his chest tightness disappeared. “After tocilizumab administration, the IL-6 level decreased gradually over the following 10 days (from 121.59 to 20.81 pg/mL), then increased rapidly to the peak (317.38 pg/mL), and then decreased to a low level (117.10 pg/mL). The transient rebounding of the IL-6 level to the peak does not mean COVID-19 relapse: Instead, this might be attributed to the recovery of the normal T cells,” the authors wrote.

On hospital day 19, the patient’s chest CT scan showed that the range of ground-glass opacities had obviously decreased, and he was declared cured and discharged from the hospital. The patient had no symptoms of MM, and related laboratory findings were all in normal ranges, according to the researchers.

“This case is the first to prove that tocilizumab is effective in the treatment of COVID-19 in MM with obvious clinical recovery; however, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhang X et al. Blood Adv. 2020;4(7):1307-10.

Recent research has shown that severe cases of COVID-19 show an excessive immune response and a strong cytokine storm, which may include high levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GSF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Following up on that research, investigators from China reported the first case of COVID-19 in a patient with multiple myeloma (MM) who was successfully treated with the humanized anti–IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab (an off-label use in the United States). The exceptional case report was published online in Blood Advances, an American Society of Hematology journal.

A 60-year-old man working in Wuhan, China, developed chest tightness without fever and cough on Feb. 1, 2020, and was admitted immediately after computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest showed multiple ground-glass opacities and pneumatocele located in both subpleural spaces. He received 400 mg of moxifloxacin IV daily for 3 days while swab specimens were collected and tested by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. A positive result for SARS-CoV-2 infection was received 3 days later. The patient was subsequently given 200-mg umifenovir (Arbidol) tablets orally, three times daily, for antiviral treatment.

The patient had a history of symptomatic MM, which was diagnosed in 2015. The patient received two cycles of induction chemotherapy consisting of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, and his symptoms completely disappeared. After that, he received thalidomide for maintenance.

Chest CT imaging on hospital day 8 showed that the bilateral, multiple ground-glass opacities from the first scan remained, and laboratory investigations revealed a high level of serum IL-6. On hospital day 9, the patient was given a single, one-time dose of 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, administered by IV. On hospital day 12, his chest tightness disappeared. “After tocilizumab administration, the IL-6 level decreased gradually over the following 10 days (from 121.59 to 20.81 pg/mL), then increased rapidly to the peak (317.38 pg/mL), and then decreased to a low level (117.10 pg/mL). The transient rebounding of the IL-6 level to the peak does not mean COVID-19 relapse: Instead, this might be attributed to the recovery of the normal T cells,” the authors wrote.

On hospital day 19, the patient’s chest CT scan showed that the range of ground-glass opacities had obviously decreased, and he was declared cured and discharged from the hospital. The patient had no symptoms of MM, and related laboratory findings were all in normal ranges, according to the researchers.

“This case is the first to prove that tocilizumab is effective in the treatment of COVID-19 in MM with obvious clinical recovery; however, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhang X et al. Blood Adv. 2020;4(7):1307-10.

Recent research has shown that severe cases of COVID-19 show an excessive immune response and a strong cytokine storm, which may include high levels of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (GSF) and interleukin-6 (IL-6). Following up on that research, investigators from China reported the first case of COVID-19 in a patient with multiple myeloma (MM) who was successfully treated with the humanized anti–IL-6 receptor antibody tocilizumab (an off-label use in the United States). The exceptional case report was published online in Blood Advances, an American Society of Hematology journal.

A 60-year-old man working in Wuhan, China, developed chest tightness without fever and cough on Feb. 1, 2020, and was admitted immediately after computed tomography (CT) imaging of his chest showed multiple ground-glass opacities and pneumatocele located in both subpleural spaces. He received 400 mg of moxifloxacin IV daily for 3 days while swab specimens were collected and tested by real-time reverse transcriptase–polymerase chain reaction. A positive result for SARS-CoV-2 infection was received 3 days later. The patient was subsequently given 200-mg umifenovir (Arbidol) tablets orally, three times daily, for antiviral treatment.

The patient had a history of symptomatic MM, which was diagnosed in 2015. The patient received two cycles of induction chemotherapy consisting of bortezomib, thalidomide, and dexamethasone, and his symptoms completely disappeared. After that, he received thalidomide for maintenance.

Chest CT imaging on hospital day 8 showed that the bilateral, multiple ground-glass opacities from the first scan remained, and laboratory investigations revealed a high level of serum IL-6. On hospital day 9, the patient was given a single, one-time dose of 8 mg/kg tocilizumab, administered by IV. On hospital day 12, his chest tightness disappeared. “After tocilizumab administration, the IL-6 level decreased gradually over the following 10 days (from 121.59 to 20.81 pg/mL), then increased rapidly to the peak (317.38 pg/mL), and then decreased to a low level (117.10 pg/mL). The transient rebounding of the IL-6 level to the peak does not mean COVID-19 relapse: Instead, this might be attributed to the recovery of the normal T cells,” the authors wrote.

On hospital day 19, the patient’s chest CT scan showed that the range of ground-glass opacities had obviously decreased, and he was declared cured and discharged from the hospital. The patient had no symptoms of MM, and related laboratory findings were all in normal ranges, according to the researchers.

“This case is the first to prove that tocilizumab is effective in the treatment of COVID-19 in MM with obvious clinical recovery; however, randomized controlled trials are needed to determine the safety and efficacy of tocilizumab,” the researchers concluded.

The authors declared that they had no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Zhang X et al. Blood Adv. 2020;4(7):1307-10.

FROM BLOOD ADVANCES

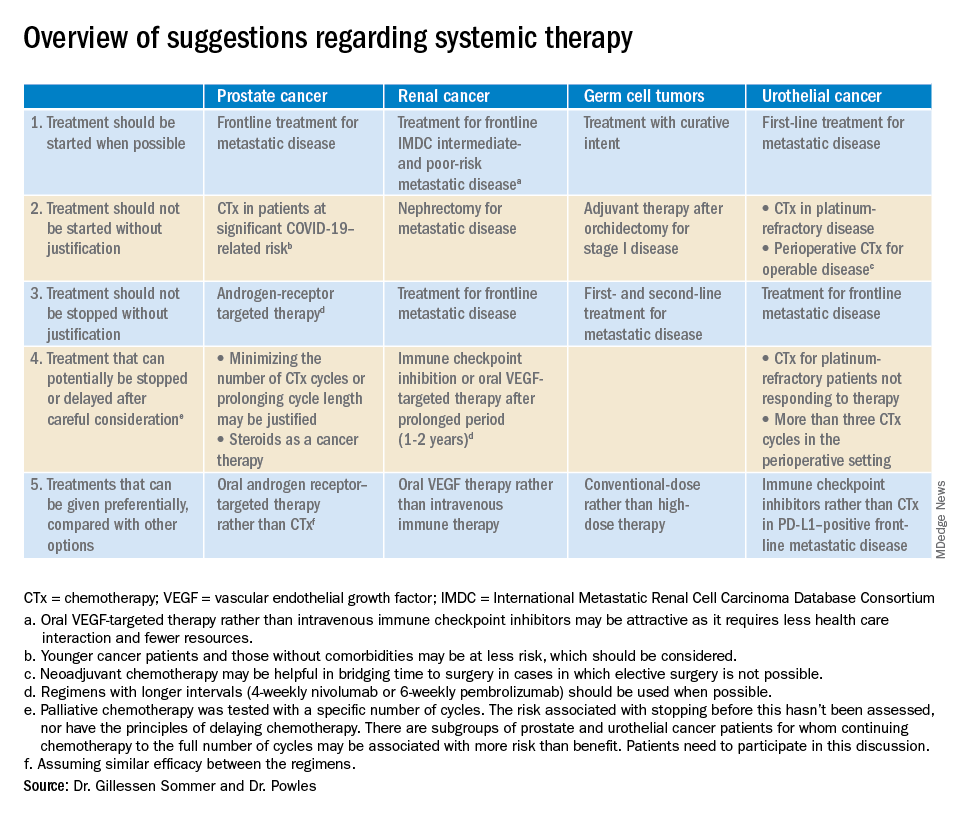

Rethink urologic cancer treatment in the era of COVID-19

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

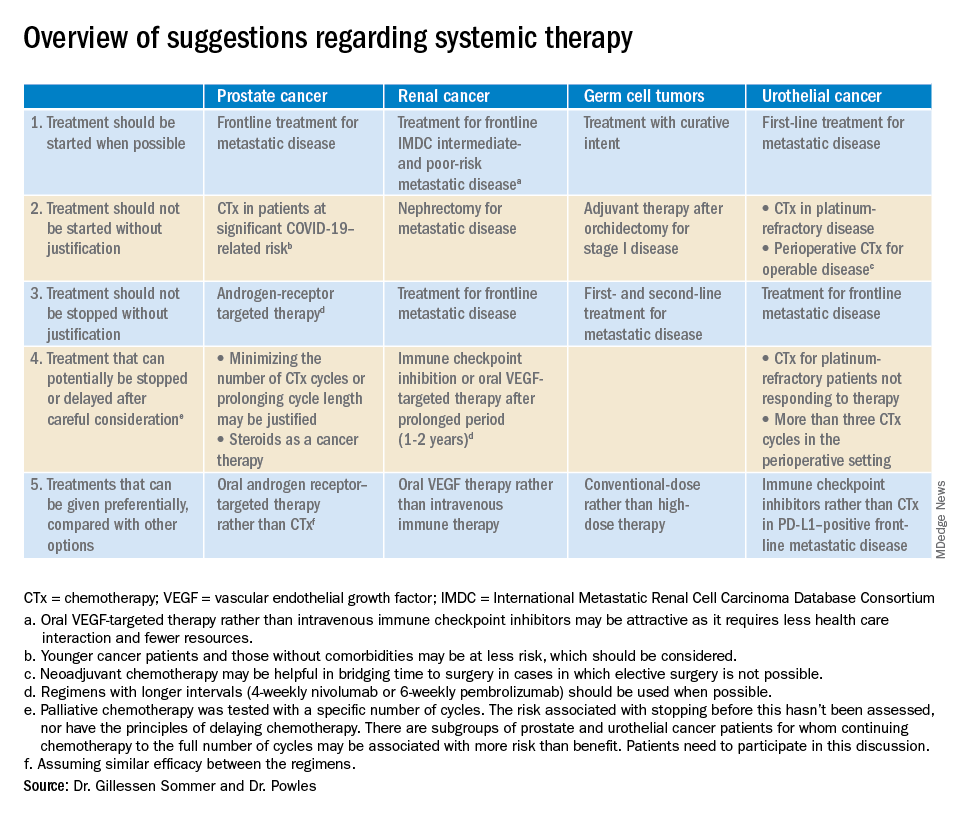

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

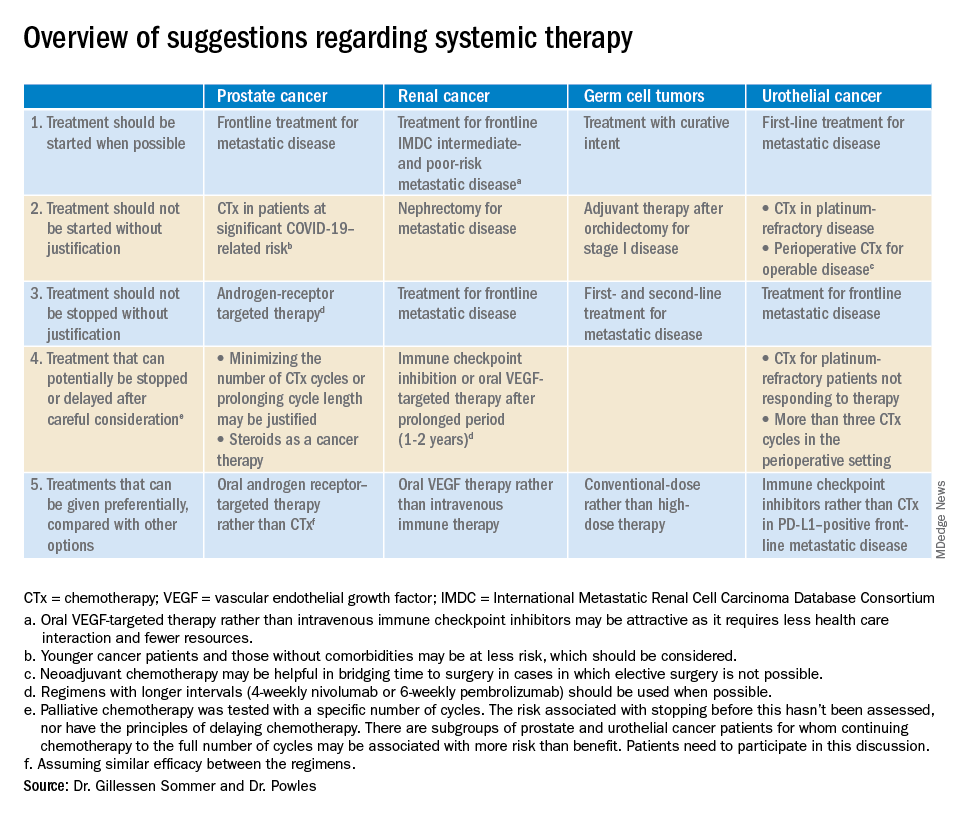

according to an editorial set to be published in European Urology.

“Regimens with a clear survival advantage should be prioritized, with curative treatments remaining mandatory,” wrote Silke Gillessen Sommer, MD, of Istituto Oncologico della Svizzera Italiana in Bellizona, Switzerland, and Thomas Powles, MD, of Barts Cancer Institute in London.

However, it may be appropriate to stop or delay therapies with modest or unproven survival benefits. “Delaying the start of therapy ... is an appropriate measure for many of the therapies in urology cancer,” they wrote.

Timely recommendations for oncologists

The COVID-19 pandemic is limiting resources for cancer, noted Zachery Reichert, MD, PhD, a urological oncologist and assistant professor at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, who was asked for his thoughts about the editorial.

Oncologists and oncology nurses are being shifted to care for COVID-19 patients, space once devoted to cancer care is being repurposed for the pandemic, and personal protective equipment needed to prepare chemotherapies is in short supply.

Meanwhile, cancer patients are at increased risk of dying from the virus (Lancet Oncol. 2020;21:335-7), so there’s a need to minimize their contact with the health care system to protect them from nosocomial infection, and a need to keep their immune system as strong as possible to fight it off.

To help cancer patients fight off infection and keep them out of the hospital, the editorialists recommended growth factors and prophylactic antibiotics after chemotherapy, palliative therapies at doses that avoid febrile neutropenia, discontinuing steroids or at least reducing their doses, and avoiding bisphosphonates if they involve potential COVID-19 exposure in medical facilities.

The advice in the editorial mirrors many of the discussions going on right now at the University of Michigan, Dr. Reichert said, and perhaps other oncology services across the United States.

It will come down to how severe the pandemic becomes locally, but he said it seems likely “a lot of us are going to be wearing a different hat for a while.”

Patients who have symptoms from a growing tumor will likely take precedence at the university, but treatment might be postponed until after COVID-19 peaks if tumors don’t affect quality of life. Also, bladder cancer surgery will probably remain urgent “because the longer you wait, the worse the outcomes,” but perhaps not prostate and kidney cancer surgery, where delay is safer, Dr. Reichert said.

Prostate/renal cancers and germ cell tumors

The editorialists noted that oral androgen receptor therapy should be preferred over chemotherapy for prostate cancer. Dr. Reichert explained that’s because androgen blockade is effective, requires less contact with health care providers, and doesn’t suppress the immune system or tie up hospital resources as much as chemotherapy. “In the world we are in right now, oral pills are a better choice,” he said.

The editorialists recommended against both nephrectomy for metastatic renal cancer and adjuvant therapy after orchidectomy for stage 1 germ cell tumors for similar reasons, and also because there’s minimal evidence of benefit.

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested considering a break from immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICIs) and oral vascular endothelial growth factors (VEGFs) for renal cancer patients who have been on them a year or two. It’s something that would be considered even under normal circumstances, Dr. Reichert explained, but it’s more urgent now to keep people out of the hospital. VEGFs should also be prioritized over ICIs; they have similar efficacy in renal cancer, but VEGFs are a pill.

They also called for oncologists to favor conventional-dose treatments for germ cell tumors over high-dose treatments, meaning bone marrow transplants or high-intensity chemotherapy. Amid a pandemic, the preference is for options “that don’t require a hospital bed,” Dr. Reichert said.

Urothelial cancer

Dr. Powles and Dr. Gillessen Sommer suggested not starting or continuing second-line chemotherapies in urothelial cancer patients refractory to first-line platinum-based therapies. The chance they will respond to second-line options is low, perhaps around 10%. That might have been enough before the pandemic, but it’s less justified amid resource shortages and the risk of COVID-19 in the infusion suite, Dr. Reichert explained.

Along the same lines, they also suggested reconsidering perioperative chemotherapy for urothelial cancer, and, if it’s still a go, recommended against going past three cycles, as the benefits in both scenarios are likely marginal. However, if COVID-19 cancels surgeries, neoadjuvant therapy might be the right – and only – call, according to the editorialists.

They recommended prioritizing ICIs over chemotherapy in patients with metastatic urothelial cancer who are positive for programmed death-ligand 1 (PD-L1). PD-L1–positive patients have a good chance of responding, and ICIs don’t suppress the immune system.

“Chemotherapy still has a slightly higher percent response, but right now, this is a better choice for” PD-L1-positive patients, Dr. Reichert said.

Dr. Gillessen Sommer and Dr. Powles disclosed ties to Bristol-Myers Squibb, Roche, and numerous other companies. Dr. Reichert has no relevant disclosures.

SOURCE: Gillessen Sommer S, Powles T. “Advice regarding systemic therapy in patients with urological cancers during the COVID-19 pandemic.” Eur Urol. https://els-jbs-prod-cdn.jbs.elsevierhealth.com/pb/assets/raw/Health%20Advance/journals/eururo/EURUROL-D-20-00382-1585928967060.pdf.

FROM EUROPEAN UROLOGY

Water-only fasting may reduce chemo modifications, hospital admissions

Patients with gynecologic malignancies who consumed only water for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each chemotherapy cycle had fewer dose delays and reductions compared with patients who didn’t fast, results of a small study showed.

The study included 23 women with ovarian, uterine, or cervical cancer, most of whom received platinum-based chemotherapy and taxanes. Fewer treatment modifications were required among the 11 patients randomized to a 24-hour water-only fast before and after each chemotherapy cycle than among the 12 patients randomized to standard care. Furthermore, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group, according to study author Courtney J. Riedinger, MD, of the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville.

She and her colleagues detailed the rationale and results of this study in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data have been updated from the abstract.

Rationale

“There’s a lot of new research and interest about nonpharmacologic interventions and lifestyle modifications to help patients cope with chemotherapy and even help with treatment, potentially,” Dr. Riedinger said in an interview.

“We decided to test water-only fasting because there’s not much data about the cell-fitness effects of fasting” on chemotherapy outcomes, she said.

Pre-chemotherapy fasting is based on the concept of differential stress resistance intended to protect normal cells but not cancer cells from the effects of chemotherapy. Fasting decreases levels of insulin-like growth factor 1, which leads healthy cells to enter a protective state by decreasing cell growth and proliferation. Cancer cells, in contrast, cannot enter the protective state, and are therefore more vulnerable than healthy, quiescent cells when exposed to drugs that target the cell cycle, Dr. Riedinger and colleagues noted.

The team cited two studies suggesting a benefit from fasting prior to chemotherapy. In the first study, mice that underwent 48-60 hours of short-term fasting were significantly less likely to die after exposure to a high dose of etoposide, compared with mice that did not fast before exposure (PNAS; 105[24]: 8215-822).

The second study showed that breast and ovarian cancer patients had improved quality of life scores and decreased fatigue when they fasted for 36 hours before and 24 hours after a chemotherapy cycle (BMC Cancer;18: article 476).

Study details

Dr. Riedinger and colleagues conducted a nonblinded, randomized trial of fasting in women, aged 34-73 years, who had gynecologic malignancies treated with a planned six cycles of chemotherapy. The patients were instructed to maintain a water-only fast for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each cycle. Controls did not fast.

Patient functional status and quality of life were investigated with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network–Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Ovarian Symptom Index (NCCN-FACT FOSI-18). Questionnaires were completed at each chemotherapy visit, and the records were reviewed to evaluate compliance, changes in treatment plan, and hospitalizations.

In all, 92% of chemotherapy cycles were completed with fasting as directed.

There were no significant differences in any of the study measures between patients who fasted and those who did not. However, this study was not powered to detect a difference, according to Dr. Riedinger.

Still, there were trends suggesting a benefit to fasting. Fasting patients had a higher mean change in NCCN-FACT FOSI-18 score compared with controls – increases of 5.11 and .22, respectively.

Five patients in the fasting group required changes to their treatment regimen, compared with eight patients in the control group. In addition, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group.

Patients tolerated the fast well without significant weight loss, and there were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities among patients who fasted.

The investigators are planning a larger study to further evaluate the effect of fasting on quality of life scores and treatment, and to evaluate the effects of fasting on hematologic toxicities. Future studies will focus on the optimal duration of fasting and the use of fasting-mimicking diets to allow for longer fasting periods, Dr. Riedinger said.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Riedinger CJ et al. SGO 2020. Abstract 22.

Patients with gynecologic malignancies who consumed only water for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each chemotherapy cycle had fewer dose delays and reductions compared with patients who didn’t fast, results of a small study showed.

The study included 23 women with ovarian, uterine, or cervical cancer, most of whom received platinum-based chemotherapy and taxanes. Fewer treatment modifications were required among the 11 patients randomized to a 24-hour water-only fast before and after each chemotherapy cycle than among the 12 patients randomized to standard care. Furthermore, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group, according to study author Courtney J. Riedinger, MD, of the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville.

She and her colleagues detailed the rationale and results of this study in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data have been updated from the abstract.

Rationale

“There’s a lot of new research and interest about nonpharmacologic interventions and lifestyle modifications to help patients cope with chemotherapy and even help with treatment, potentially,” Dr. Riedinger said in an interview.

“We decided to test water-only fasting because there’s not much data about the cell-fitness effects of fasting” on chemotherapy outcomes, she said.

Pre-chemotherapy fasting is based on the concept of differential stress resistance intended to protect normal cells but not cancer cells from the effects of chemotherapy. Fasting decreases levels of insulin-like growth factor 1, which leads healthy cells to enter a protective state by decreasing cell growth and proliferation. Cancer cells, in contrast, cannot enter the protective state, and are therefore more vulnerable than healthy, quiescent cells when exposed to drugs that target the cell cycle, Dr. Riedinger and colleagues noted.

The team cited two studies suggesting a benefit from fasting prior to chemotherapy. In the first study, mice that underwent 48-60 hours of short-term fasting were significantly less likely to die after exposure to a high dose of etoposide, compared with mice that did not fast before exposure (PNAS; 105[24]: 8215-822).

The second study showed that breast and ovarian cancer patients had improved quality of life scores and decreased fatigue when they fasted for 36 hours before and 24 hours after a chemotherapy cycle (BMC Cancer;18: article 476).

Study details

Dr. Riedinger and colleagues conducted a nonblinded, randomized trial of fasting in women, aged 34-73 years, who had gynecologic malignancies treated with a planned six cycles of chemotherapy. The patients were instructed to maintain a water-only fast for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each cycle. Controls did not fast.

Patient functional status and quality of life were investigated with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network–Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Ovarian Symptom Index (NCCN-FACT FOSI-18). Questionnaires were completed at each chemotherapy visit, and the records were reviewed to evaluate compliance, changes in treatment plan, and hospitalizations.

In all, 92% of chemotherapy cycles were completed with fasting as directed.

There were no significant differences in any of the study measures between patients who fasted and those who did not. However, this study was not powered to detect a difference, according to Dr. Riedinger.

Still, there were trends suggesting a benefit to fasting. Fasting patients had a higher mean change in NCCN-FACT FOSI-18 score compared with controls – increases of 5.11 and .22, respectively.

Five patients in the fasting group required changes to their treatment regimen, compared with eight patients in the control group. In addition, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group.

Patients tolerated the fast well without significant weight loss, and there were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities among patients who fasted.

The investigators are planning a larger study to further evaluate the effect of fasting on quality of life scores and treatment, and to evaluate the effects of fasting on hematologic toxicities. Future studies will focus on the optimal duration of fasting and the use of fasting-mimicking diets to allow for longer fasting periods, Dr. Riedinger said.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Riedinger CJ et al. SGO 2020. Abstract 22.

Patients with gynecologic malignancies who consumed only water for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each chemotherapy cycle had fewer dose delays and reductions compared with patients who didn’t fast, results of a small study showed.

The study included 23 women with ovarian, uterine, or cervical cancer, most of whom received platinum-based chemotherapy and taxanes. Fewer treatment modifications were required among the 11 patients randomized to a 24-hour water-only fast before and after each chemotherapy cycle than among the 12 patients randomized to standard care. Furthermore, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group, according to study author Courtney J. Riedinger, MD, of the University of Tennessee Medical Center in Knoxville.

She and her colleagues detailed the rationale and results of this study in an abstract that had been slated for presentation at the Society of Gynecologic Oncology’s Annual Meeting on Women’s Cancer. The meeting was canceled because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Data have been updated from the abstract.

Rationale

“There’s a lot of new research and interest about nonpharmacologic interventions and lifestyle modifications to help patients cope with chemotherapy and even help with treatment, potentially,” Dr. Riedinger said in an interview.

“We decided to test water-only fasting because there’s not much data about the cell-fitness effects of fasting” on chemotherapy outcomes, she said.

Pre-chemotherapy fasting is based on the concept of differential stress resistance intended to protect normal cells but not cancer cells from the effects of chemotherapy. Fasting decreases levels of insulin-like growth factor 1, which leads healthy cells to enter a protective state by decreasing cell growth and proliferation. Cancer cells, in contrast, cannot enter the protective state, and are therefore more vulnerable than healthy, quiescent cells when exposed to drugs that target the cell cycle, Dr. Riedinger and colleagues noted.

The team cited two studies suggesting a benefit from fasting prior to chemotherapy. In the first study, mice that underwent 48-60 hours of short-term fasting were significantly less likely to die after exposure to a high dose of etoposide, compared with mice that did not fast before exposure (PNAS; 105[24]: 8215-822).

The second study showed that breast and ovarian cancer patients had improved quality of life scores and decreased fatigue when they fasted for 36 hours before and 24 hours after a chemotherapy cycle (BMC Cancer;18: article 476).

Study details

Dr. Riedinger and colleagues conducted a nonblinded, randomized trial of fasting in women, aged 34-73 years, who had gynecologic malignancies treated with a planned six cycles of chemotherapy. The patients were instructed to maintain a water-only fast for 24 hours before and 24 hours after each cycle. Controls did not fast.

Patient functional status and quality of life were investigated with the National Comprehensive Cancer Network–Functional Assessment of Cancer Therapy Ovarian Symptom Index (NCCN-FACT FOSI-18). Questionnaires were completed at each chemotherapy visit, and the records were reviewed to evaluate compliance, changes in treatment plan, and hospitalizations.

In all, 92% of chemotherapy cycles were completed with fasting as directed.

There were no significant differences in any of the study measures between patients who fasted and those who did not. However, this study was not powered to detect a difference, according to Dr. Riedinger.

Still, there were trends suggesting a benefit to fasting. Fasting patients had a higher mean change in NCCN-FACT FOSI-18 score compared with controls – increases of 5.11 and .22, respectively.

Five patients in the fasting group required changes to their treatment regimen, compared with eight patients in the control group. In addition, there were no hospital admissions in the fasting group and two admissions in the control group.

Patients tolerated the fast well without significant weight loss, and there were no grade 3 or 4 toxicities among patients who fasted.

The investigators are planning a larger study to further evaluate the effect of fasting on quality of life scores and treatment, and to evaluate the effects of fasting on hematologic toxicities. Future studies will focus on the optimal duration of fasting and the use of fasting-mimicking diets to allow for longer fasting periods, Dr. Riedinger said.

The study was internally funded. The authors reported no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Riedinger CJ et al. SGO 2020. Abstract 22.

FROM SGO 2020

Advice from the front lines: How cancer centers can cope with COVID-19

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

according to the medical director of a cancer care alliance in the first U.S. epicenter of the coronavirus outbreak.

Jennie R. Crews, MD, the medical director of the Seattle Cancer Care Alliance (SCCA), discussed the SCCA experience and offered advice for other cancer centers in a webinar hosted by the Association of Community Cancer Centers.

Dr. Crews highlighted the SCCA’s use of algorithms to predict which patients can be managed via telehealth and which require face-to-face visits, human resource issues that arose at SCCA, screening and testing procedures, and the importance of communication with patients, caregivers, and staff.

Communication

Dr. Crews stressed the value of clear, regular, and internally consistent staff communication in a variety of formats. SCCA sends daily email blasts to their personnel regarding policies and procedures, which are archived on the SCCA intranet site.

SCCA also holds weekly town hall meetings at which leaders respond to staff questions regarding practical matters they have encountered and future plans. Providers’ up-to-the-minute familiarity with policies and procedures enables all team members to uniformly and clearly communicate to patients and caregivers.

Dr. Crews emphasized the value of consistency and “over-communication” in projecting confidence and preparedness to patients and caregivers during an unsettling time. SCCA has developed fact sheets, posted current information on the SCCA website, and provided education during doorway screenings.

Screening and testing

All SCCA staff members are screened daily at the practice entrance so they have personal experience with the process utilized for patients. Because symptoms associated with coronavirus infection may overlap with cancer treatment–related complaints, SCCA clinicians have expanded the typical coronavirus screening questionnaire for patients on cancer treatment.

Patients with ambiguous symptoms are masked, taken to a physically separate area of the SCCA clinics, and screened further by an advanced practice provider. The patients are then triaged to either the clinic for treatment or to the emergency department for further triage and care.

Although testing processes and procedures have been modified, Dr. Crews advised codifying those policies and procedures, including notification of results and follow-up for both patients and staff. Dr. Crews also stressed the importance of clearly articulated return-to-work policies for staff who have potential exposure and/or positive test results.

At the University of Washington’s virology laboratory, they have a test turnaround time of less than 12 hours.

Planning ahead

Dr. Crews highlighted the importance of community-based surge planning, utilizing predictive models to assess inpatient capacity requirements and potential repurposing of providers.

The SCCA is prepared to close selected community sites and shift personnel to other locations if personnel needs cannot be met because of illness or quarantine. Contingency plans include specialized pharmacy services for patients requiring chemotherapy.

The SCCA has not yet experienced shortages of personal protective equipment (PPE). However, Dr. Crews said staff require detailed education regarding the use of PPE in order to safeguard the supply while providing maximal staff protection.

Helping the helpers

During the pandemic, SCCA has dealt with a variety of challenging human resource issues, including:

- Extending sick time beyond what was previously “stored” in staff members’ earned time off.

- Childcare during an extended hiatus in school and daycare schedules.

- Programs to maintain and/or restore employee wellness (including staff-centered support services, spiritual care, mindfulness exercises, and town halls).

Dr. Crews also discussed recruitment of community resources to provide meals for staff from local restaurants with restricted hours and transportation resources for staff and patients, as visitors are restricted (currently one per patient).

Managing care

Dr. Crews noted that the University of Washington had a foundational structure for a telehealth program prior to the pandemic. Their telehealth committee enabled SCCA to scale up the service quickly with their academic partners, including training modules for and certification of providers, outfitting off-site personnel with dedicated lines and hardware, and provision of personal Zoom accounts.

SCCA also devised algorithms for determining when face-to-face visits, remote management, or deferred visits are appropriate in various scenarios. The algorithms were developed by disease-specialized teams.

As a general rule, routine chemotherapy and radiation are administered on schedule. On-treatment and follow-up office visits are conducted via telehealth if possible. In some cases, initiation of chemotherapy and radiation has been delayed, and screening services have been suspended.

In response to questions about palliative care during the pandemic, Dr. Crews said SCCA has encouraged their patients to complete, review, or update their advance directives. The SCCA has not had the need to resuscitate a coronavirus-infected outpatient but has instituted policies for utilizing full PPE on any patient requiring resuscitation.

In her closing remarks, Dr. Crews stressed that the response to COVID-19 in Washington state has required an intense collaboration among colleagues, the community, and government leaders, as the actions required extended far beyond medical decision makers alone.

Dr. Lyss was a community-based medical oncologist and clinical researcher for more than 35 years before his recent retirement. His clinical and research interests were focused on breast and lung cancers as well as expanding clinical trial access to medically underserved populations. He is based in St. Louis. He has no conflicts of interest.

20% with cancer on checkpoint inhibitors get thyroid dysfunction

new research suggests.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of many different types of cancers, but can also trigger a variety of immune-related adverse effects. As these drugs become more widely used, rates of these events appear to be more common in the real-world compared with clinical trial settings.

In their new study, Zoe Quandt, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues specifically looked at thyroid dysfunction in their own institution’s EHR data and found more than double the rate of hypothyroidism and more than triple the rate of hyperthyroidism, compared with rates in published trials.

Moreover, in contrast to previous studies that have found differences in thyroid dysfunction by checkpoint inhibitor type, Dr. Quandt and colleagues instead found significant differences by cancer type.

Dr. Quandt presented the findings during a virtual press briefing held March 31originally scheduled for ENDO 2020.

“Thyroid dysfunction following checkpoint inhibitor therapy appears to be much more common than was previously reported in clinical trials, and this is one of the first studies to show differences by cancer type rather than by checkpoint inhibitor type,” Dr. Quandt said during the presentation.

However, she also cautioned that there’s “a lot more research to be done to validate case definitions and validate these findings.”

Asked to comment, endocrinologist David C. Lieb, MD, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said in an interview, “These drugs are becoming so much more commonly used, so it’s not surprising that we’re seeing more endocrine complications, especially thyroid disease.”

“Endocrinologists need to work closely with oncologists to make sure patients are being screened and followed appropriately.”

‘A much higher percentage than we were expecting’

Dr. Quandt’s study included 1,146 individuals treated with checkpoint inhibitors at UCSF during 2012-2018 who did not have thyroid cancer or preexisting thyroid dysfunction.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was the most common treatment (45%), followed by nivolumab (Opdivo) (20%). Less than 10% of patients received atezolizumab (Tecentriq), durvalumab (Imfizi), ipilimumab (Yervoy) monotherapy, combined ipilimumab/nivolumab, or other combinations of checkpoint inhibitors.

A total of 19.1% developed thyroid disease, with 13.4% having hypothyroidism and 9.5% hyperthyroidism. These figures far exceed those found in a recent meta-analysis of 38 randomized clinical trials of checkpoint inhibitors that included 7551 patients.

“Using this approach, we found a much higher percentage of patients who developed thyroid dysfunction than we were expecting,” Dr. Quandt said.

In both cases, the two categories – hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism – aren’t mutually exclusive as hypothyroidism can arise de novo or subsequent to hyperthyroidism.

Dr Lieb commented, “It would be interesting to see what the causes of hyperthyroidism are – thyroiditis or Graves disease.”

Dr. Quandt mentioned a possible reason for the large difference between clinical trial and real-world data.

“Once we’re actually using these drugs outside of clinical trials, some of the restrictions about using them in people with other autoimmune diseases have been lifted, so my guess is that as we give them to a broader population we’re seeing more of these [adverse effects],” she suggested.

Also, “In the initial trials, people weren’t quite as aware of the possibilities of these side effects, so now we’re doing many more labs. Patients get thyroid function tests with every infusion, so I think we’re probably catching more patients who develop disease.”

Differences by cancer type, not checkpoint inhibitor type

And in a new twist, Dr. Quandt found that, in contrast to the differences seen by checkpoint inhibitor type in randomized trials, “surprisingly, we found that this difference did not reach statistical significance.”

“Instead, we saw that cancer type was associated with development of thyroid dysfunction, even after taking checkpoint inhibitor type into account.”

The percentages of patients who developed thyroid dysfunction ranged from 9.7% of those with glioblastoma to 40.0% of those with renal cell carcinoma.

The reason for this is not clear, said Dr. Quandt in an interview.

One possibility relates to other treatments patients with cancer also receive. In renal cell carcinoma, for example, patients also are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which can also cause thyroid dysfunction, so they may be more susceptible. Or there may be shared antigens activating the immune system.

“That’s definitely one of the questions we’re looking at,” she said.

Dr. Quandt and Dr. Lieb have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.

Immune checkpoint inhibitors have revolutionized the treatment of many different types of cancers, but can also trigger a variety of immune-related adverse effects. As these drugs become more widely used, rates of these events appear to be more common in the real-world compared with clinical trial settings.

In their new study, Zoe Quandt, MD, of the University of California, San Francisco (UCSF), and colleagues specifically looked at thyroid dysfunction in their own institution’s EHR data and found more than double the rate of hypothyroidism and more than triple the rate of hyperthyroidism, compared with rates in published trials.

Moreover, in contrast to previous studies that have found differences in thyroid dysfunction by checkpoint inhibitor type, Dr. Quandt and colleagues instead found significant differences by cancer type.

Dr. Quandt presented the findings during a virtual press briefing held March 31originally scheduled for ENDO 2020.

“Thyroid dysfunction following checkpoint inhibitor therapy appears to be much more common than was previously reported in clinical trials, and this is one of the first studies to show differences by cancer type rather than by checkpoint inhibitor type,” Dr. Quandt said during the presentation.

However, she also cautioned that there’s “a lot more research to be done to validate case definitions and validate these findings.”

Asked to comment, endocrinologist David C. Lieb, MD, associate professor of medicine at Eastern Virginia Medical School in Norfolk, said in an interview, “These drugs are becoming so much more commonly used, so it’s not surprising that we’re seeing more endocrine complications, especially thyroid disease.”

“Endocrinologists need to work closely with oncologists to make sure patients are being screened and followed appropriately.”

‘A much higher percentage than we were expecting’

Dr. Quandt’s study included 1,146 individuals treated with checkpoint inhibitors at UCSF during 2012-2018 who did not have thyroid cancer or preexisting thyroid dysfunction.

Pembrolizumab (Keytruda) was the most common treatment (45%), followed by nivolumab (Opdivo) (20%). Less than 10% of patients received atezolizumab (Tecentriq), durvalumab (Imfizi), ipilimumab (Yervoy) monotherapy, combined ipilimumab/nivolumab, or other combinations of checkpoint inhibitors.

A total of 19.1% developed thyroid disease, with 13.4% having hypothyroidism and 9.5% hyperthyroidism. These figures far exceed those found in a recent meta-analysis of 38 randomized clinical trials of checkpoint inhibitors that included 7551 patients.

“Using this approach, we found a much higher percentage of patients who developed thyroid dysfunction than we were expecting,” Dr. Quandt said.

In both cases, the two categories – hypothyroidism and hyperthyroidism – aren’t mutually exclusive as hypothyroidism can arise de novo or subsequent to hyperthyroidism.

Dr Lieb commented, “It would be interesting to see what the causes of hyperthyroidism are – thyroiditis or Graves disease.”

Dr. Quandt mentioned a possible reason for the large difference between clinical trial and real-world data.

“Once we’re actually using these drugs outside of clinical trials, some of the restrictions about using them in people with other autoimmune diseases have been lifted, so my guess is that as we give them to a broader population we’re seeing more of these [adverse effects],” she suggested.

Also, “In the initial trials, people weren’t quite as aware of the possibilities of these side effects, so now we’re doing many more labs. Patients get thyroid function tests with every infusion, so I think we’re probably catching more patients who develop disease.”

Differences by cancer type, not checkpoint inhibitor type

And in a new twist, Dr. Quandt found that, in contrast to the differences seen by checkpoint inhibitor type in randomized trials, “surprisingly, we found that this difference did not reach statistical significance.”

“Instead, we saw that cancer type was associated with development of thyroid dysfunction, even after taking checkpoint inhibitor type into account.”

The percentages of patients who developed thyroid dysfunction ranged from 9.7% of those with glioblastoma to 40.0% of those with renal cell carcinoma.

The reason for this is not clear, said Dr. Quandt in an interview.

One possibility relates to other treatments patients with cancer also receive. In renal cell carcinoma, for example, patients also are treated with tyrosine kinase inhibitors, which can also cause thyroid dysfunction, so they may be more susceptible. Or there may be shared antigens activating the immune system.

“That’s definitely one of the questions we’re looking at,” she said.

Dr. Quandt and Dr. Lieb have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article originally appeared on Medscape.com.

new research suggests.