User login

Prostate Cancer Surveillance After Radiation Therapy in a National Delivery System (FULL)

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

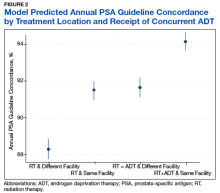

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

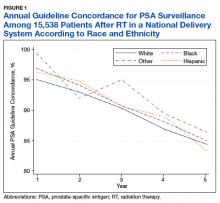

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guideline concordance with PSA surveillance among veterans treated with definitiveradiation therapy was generally high, but opportunities may exist to improve surveillance among select groups.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

Guidelines recommend prostate-specific antigen (PSA) surveillance among men treated with definitive radiation therapy (RT) for prostate cancer. Specifically, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network recommends testing every 6 to 12 months for 5 years and annually thereafter (with no specific stopping period specified), while the American Urology Association recommends testing for at least 10 years, with the frequency to be determined by the risk of relapse and patient preferences for monitoring.1,2 Salvage treatments exist for men with localized recurrence identified early through PSA testing, so adherence to follow-up guidelines is important for quality prostate cancer survivorship care.1,2

However, few studies focus on adherence to PSA surveillance following radiation therapy. Posttreatment surveillance among surgical patients is generally high, but sociodemographic disparities exist. Racial and ethnic minorities and unmarried men are less likely to undergo guideline concordant surveillance than is the general population, potentially preventing effective salvage therapy.3,4 A recent Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) study on posttreatment surveillance included radiation therapy patients but did not examine the impact of younger age, concurrent androgen deprivation therapy (ADT), or treatment facility (ie, diagnosed and treated at the same vs different facilities, with the latter including a separate VA facility or the community) on surveillance patterns.5 The latter is particularly relevant given increasing efforts to coordinate care outside the VA delivery system supported by the 2018 VA Maintaining Systems and Strengthening Integrated Outside Networks (MISSION) Act. Furthermore, these patient, treatment, and delivery system factors may each uniquely contribute to whether patients receive guideline-recommended PSA surveillance after prostate cancer treatment.

For these reasons, we conducted a study to better understand determinants of adherence to guideline-recommended PSA surveillance among veterans undergoing definitive radiation therapy with or without concurrent ADT. Our study uniquely included both elderly and nonelderly patients as well as investigated relationships between treatment at or away from the diagnosing facility. Although we found high overall levels of adherence to PSA surveillance, our findings do offer insights into determinants associated with worse adherence and provide opportunities to improve prostate cancer survivorship care after RT.

Methods

This study population included men with biopsy-proven nonmetastatic incident prostate cancer diagnosed between January 2005 and December 2008, with follow-up through 2012, identified using the VA Central Cancer Registry. We included men who underwent definitive RT with or without concurrent ADT injections, determined using the VA pharmacy files. We excluded men with a prior diagnosis of prostate or other malignancy (given the presence of other malignancies might affect life expectancy and surveillance patterns), hospice enrollment within 30 days, diagnosis at autopsy, and those treated with radical prostatectomy. We extracted cancer registry data, including biopsy Gleason score, pretreatment PSA level, clinical tumor stage, and whether RT was delivered at the patient’s diagnosing facility. For the latter, we used data on radiation location coded by the tumor registrar. We also collected demographic information, including age at diagnosis, race, ethnicity, marital status, and ZIP code. We used diagnosis codes to determine Charlson comorbidity scores similar to prior studies.6-8

Primary Outcome

The primary outcome was receipt of guideline concordant annual PSA surveillance in the initial 5 years following RT. We used laboratory files within the VA Corporate Data Warehouse to identify the date and value for each PSA test after RT for the entire cohort. Specifically, we defined the surveillance period as 60 days after initiation of RT through December 31, 2012. We defined guideline concordance as receiving at least 1 PSA test for each 12-month period after RT.

Statistical Analysis

We used descriptive statistics to characterize our cohort of veterans with prostate cancer treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT. To handle missing data, we performed multiple imputation, generating 10 imputations using all baseline clinical and demographic variables, year of diagnosis, and the regional VA network (ie, the Veterans Integrated Services Network [VISN]) for each patient.

Next, we calculated the annual guideline concordance rate for each year of follow-up for each patient, for the overall cohort, as well as by age, race/ethnicity, and concurrent ADT use. We examined bivariable relationships between guideline concordance and baseline demographic, clinical, and delivery system factors, including year of diagnosis and whether patients were treated at the diagnosing facility, using multilevel logistic regression modeling to account for clustering at the patient level.

Analyses were performed using Stata Version 15 (College Station, TX). We considered a 2-sided P value of < .05 as statistically significant. This study was approved by the VA Ann Arbor Health Care System Institution Review Board.

Results

We evaluated annual PSA surveillance for 15,538 men treated with RT with or without concurrent ADT (Table 1).

On unadjusted analysis, annual guideline concordance was less common among patients who were at the extremes of age, white, had Gleason 6 disease, PSA ≤ 10 ng/mL, did not receive concurrent ADT, and were treated away from their diagnosing facility (P < .05) (data not shown). We did find slight differences in patient characteristics based on whether patients were treated at their diagnosing facility (Table 2).

Overall, we found annual guideline concordance was initially very high, though declined slightly over the study period. For example, guideline concordance dropped from 96% in year 1 to 85% in year 5, with an average patient-level guideline concordance of 91% during the study period. We found minimal differences in annual surveillance after RT by race/ethnicity (Figure 1).

On multilevel multivariable analysis to adjust for clustering at the patient level, we found that race and PSA level were no longer significant predictors of annual surveillance (Table 3).

Discussion

We investigated adherence to guideline-recommended annual surveillance PSA testing in a national cohort of veterans treated with definitive RT for prostate cancer. We found guideline concordance was initially high and decreased slightly over time. We also found guideline concordance with PSA surveillance varied based on a number of clinical and delivery system factors, including marital status, rurality, receipt of concurrent ADT, as well as whether the veteran was treated at his diagnosing facility. Taken together, these overall results are promising, however, also point to unique considerations for some patient groups and potentially those treated in the community.

Our finding of lower guideline concordance among nonmarried patients is consistent with prior research, including our study of patients undergoing surgery for prostate cancer.4 Addressing surveillance in this population is important, as they may have less social support than do their married counterparts. We also found surveillance was lower at the extremes of age, which may be appropriate in elderly patients with limited life expectancy but is concerning for younger men with low competing mortality risks.7 Future work should explore whether younger patients experience barriers to care, including employment challenges, as these men are at greatest risk of cancer progression if recurrence goes undetected.

Although rural patients are less likely to undergo definitive prostate cancer treatment, possibly reflecting barriers to care, in our study, surveillance was actually higher among this population than that for urban patients.9 This could reflect the VA’s success in connecting rural patients to appropriate services despite travel distances to maintain quality of cancer care.10 Given annual PSA surveillance is relatively infrequent and not particularly resource intensive, these high surveillance rates might not apply to patients with cancers who need more frequent survivorship care, such as those with head and neck cancer. Future work should examine why surveillance rates among urban patients might be slightly lower, as living in a metropolitan area does not equate to the absence of barriers to survivorship care, especially for veterans who may not be able to take time off from work or have transportation barriers.

We found guideline concordance was higher among patients with higher Gleason scores, which is important given their higher likelihood of failure. However, low- and intermediate-risk patients also are at risk for treatment failure, so annual PSA surveillance should be optimized in this population unless future studies support the safety and feasibility of less frequent surveillance.10-13 Our finding of increased surveillance in patients who receive concurrent ADT may relate to the increased frequency of survivorship care given the need for injections, often every 3 to 6 months. Future studies might examine whether surveillance decreases in this population once they complete their short or long-term ADT, typically given for a maximum of 3 years.

A particularly relevant finding given recent VA policy changes includes lower guideline concordance for patients receiving RT at a different facility than where they were diagnosed. One possible explanation is that a proportion of patients treated outside of their home facilities use Medicare or private insurance and may have surveillance performed outside of the VA, which would not have been captured in our study.14 However, it remains plausible that there are challenges related to coordination and fragmentation of survivorship care for veterans who receive care at separate VA facilities or receive their initial treatment in the community.15 Future studies can help quantify how much this difference is driven by diagnosis and treatment at separate VA sites vs treatment outside of the VA, as different strategies might be necessary to improve surveillance in these 2 populations. Moreover, electronic health record-based tracking has been proposed as a strategy to identify patients who have not received guideline concordant PSA surveillance.14 This strategy may help increase guideline concordance regardless of initial treatment location if VA survivorship care is intended.

Although our study examined receipt of PSA testing, it did not examine whether patients are physically seen back in radiation oncology clinics, or whether their PSAs have been reviewed by radiation oncology providers. Although many surgical patients return to primary care providers for PSA surveillance, surveillance after RT is more complex and likely best managed in the initial years by radiation oncologists. Unlike the postoperative setting in which the definition of PSA failure is straightforward at > 0.2 ng/mL, the definition of treatment failure after RT is more complicated as described below.

For patients who did not receive concurrent ADT, failure is defined as a PSA nadir + 2 ng/mL, which first requires establishing the nadir using the first few postradiation PSA values.15 It becomes even more complex in the setting of ADT as it causes PSA suppression even in the absence of RT due to testosterone suppression.2 At the conclusion of ADT (short term 4-6 months or long term 18-36 months), the PSA may rise as testosterone recovers.15,16 This is not necessarily indicative of treatment failure, as some normal PSA-producing prostatic tissue may remain after treatment. Given these complexities, ongoing survivorship care with radiation oncology is recommended at least in the short term.

Physical visits are a challenge for some patients undergoing prostate cancer surveillance after treatment. Therefore, exploring the safety and feasibility of automated PSA tracking15 and strategies for increasing utilization of telemedicine, including clinical video telehealth appointments that are already used for survivorship and other urologic care in a number of VA clinics, represents opportunities to systematically provide highest quality survivorship care in VA.17,18

Conclusion

Most veterans receive guideline concordant PSA surveillance after RT for prostate cancer. Nonetheless, at the beginning of treatment, providers should screen veterans for risk factors for loss to follow-up (eg, care at a different or non-VA facility), discuss geographic, financial, and other barriers, and plan to leverage existing VA resources (eg, travel support) to continue to achieve high-quality PSA surveillance and survivorship care. Future research should investigate ways to take advantage of the VA’s robust electronic health record system and telemedicine infrastructure to further optimize prostate cancer survivorship care and PSA surveillance particularly among vulnerable patient groups and those treated outside of their diagnosing facility.

Acknowledgments

Funding Sources: VA HSR&D Career Development Award: 2 (CDA 12−171) and NCI R37 R37CA222885 (TAS).

Author disclosures

The authors report no actual or potential conflicts of interest with regard to this article.

Disclaimer

The opinions expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of Federal Practitioner, Frontline Medical Communications Inc., the US Government, or any of its agencies.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.

1. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN clinical practice guidelines in oncology: prostate cancer v4.2018. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/prostate.pdf. Updated August 15, 2018. Accessed January 23, 2019.

2. Sanda MG, Chen RC, Crispino T, et al. Clinically localized prostate cancer: AUA/ASTRO/SUO guideline. https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/prostate-cancer-clinically-localized-(2017). Published 2017. Accessed January 22,2019.

3. Zeliadt SB, Penson DF, Albertsen PC, Concato J, Etzioni RD. Race independently predicts prostate specific antigen testing frequency following a prostate carcinoma diagnosis. Cancer. 2003;98(3):496-503.

4. Trantham LC, Nielsen ME, Mobley LR, Wheeler SB, Carpenter WR, Biddle AK. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing as a disease surveillance tool following radical prostatectomy. Cancer. 2013;119(19):3523-3530.

5. Shi Y, Fung KZ, John Boscardin W, et al. Individualizing PSA monitoring among older prostate cancer survivors. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33(5):602-604.

6. Chapman C, Burns J, Caram M, Zaslavsky A, Tsodikov A, Skolarus TA. Multilevel predictors of surveillance PSA guideline concordance after radical prostatectomy: a national Veterans Affairs study. Paper presented at: Association of VA Hematology/Oncology Annual Meeting;

September 28-30, 2018; Chicago, IL. Abstract 34. https://www.mdedge.com/fedprac/avaho/article/175094/prostate-cancer/multilevel-predictors-surveillance-psa-guideline. Accessed January 22, 2019.

7. Kirk PS, Borza T, Caram MEV, et al. Characterising potential bone scan overuse amongst men treated with radical prostatectomy. BJU Int. 2018. [Epub ahead of print.]

8. Kirk PS, Borza T, Shahinian VB, et al. The implications of baseline bone-health assessment at initiation of androgen-deprivation therapy for prostate cancer. BJU Int. 2018;121(4):558-564.

9. Baldwin LM, Andrilla CH, Porter MP, Rosenblatt RA, Patel S, Doescher MP. Treatment of early-stage prostate cancer among rural and urban patients. Cancer. 2013;119(16):3067-3075.

10. Skolarus TA, Chan S, Shelton JB, et al. Quality of prostate cancer care among rural men in the Veterans Health Administration. Cancer. 2013;119(20):3629-3635.

11. Hamdy FC, Donovan JL, Lane JA, et al; ProtecT Study Group. 10-year outcomes after monitoring, surgery, or radiotherapy for localized prostate cancer. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(15):1415-1424.

12. Michalski JM, Moughan J, Purdy J, et al. Effect of standard vs dose-escalated radiation therapy for patients with intermediate-risk prostate cancer: the NRG Oncology RTOG 0126 randomized clinical trial. JAMA Oncol.2018;4(6):e180039.

13. Chang MG, DeSotto K, Taibi P, Troeschel S. Development of a PSA tracking system for patients with prostate cancer following definitive radiotherapy to enhance rural health. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34(suppl 2):39-39.

14. Skolarus TA, Zhang Y, Hollenbeck BK. Understanding fragmentation of prostate cancer survivorship care: implications for cost and quality. Cancer. 2012;118(11):2837-2845.

15. Roach M, 3rd, Hanks G, Thames H Jr, et al. Defining biochemical failure following radiotherapy with or without hormonal therapy in men with clinically localized prostate cancer: recommendations of the RTOG-ASTRO Phoenix Consensus Conference. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2006;65(4):965-974.

16. Buyyounouski MK, Hanlon AL, Horwitz EM, Uzzo RG, Pollack A. Biochemical failure and the temporal kinetics of prostate-specific antigen after radiation therapy with androgen deprivation. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2005;61(5):1291-1298.

17. Chu S, Boxer R, Madison P, et al. Veterans Affairs telemedicine: bringing urologic care to remote clinics. Urology. 2015;86(2):255-260.

18. Safir IJ, Gabale S, David SA, et al. Implementation of a tele-urology program for outpatient hematuria referrals: initial results and patient satisfaction. Urology. 2016;97:33-39.