User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Cancer prevalence among COVID-19 patients may be higher than previously reported

An early report pegged the prevalence of cancer among COVID-19 patients at 1%, but authors of a recent meta-analysis found an overall prevalence of 2% and up to 3% depending on the subset of data they reviewed.

However, those findings are limited by the retrospective nature of the studies published to date, according to the authors of the meta-analysis, led by Aakash Desai, MBBS, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

Nevertheless, the results do confirm that cancer patients and survivors are an important at-risk population for COVID-19, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“We hope that additional data from China and Italy will provide information on the characteristics of patients with cancer at risk, types of cancer that confer higher risk, and systemic regimens that may increase COVID-19 infection complications,” the authors wrote in JCO Global Oncology.

More than 15 million individuals with cancer and many more cancer survivors are at increased risk of COVID-19 because of compromised immune systems, according to the authors.

Exactly how many individuals with cancer are among the COVID-19 cases remains unclear, though a previous report suggested the prevalence of cancer was 1% (95% confidence interval, 0.61%-1.65%) among COVID-19 patients in China (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:335-7). This “seems to be higher” than the 0.29% prevalence of cancer in the overall Chinese population, the investigators noted at the time.

That study revealed 18 cancer patients among 1,590 COVID-19 cases, though it was “hypothesis generating,” according to Dr. Desai and colleagues, who rolled that data into their meta-analysis of 11 reports including 3,661 COVID-19 cases.

Overall, Dr. Desai and colleagues found the pooled prevalence of cancer was 2.0% (95% CI, 2.0%-3.0%) in that population. In a subgroup analysis of five studies with sample sizes of less than 100 COVID-19 patients, the researchers found a “slightly higher” prevalence of 3.0% (95% CI, 1.0%-6.0%).

However, even that data wasn’t robust enough for Dr. Desai and colleagues to make any pronouncements on cancer prevalence. “Overall, current evidence on the association between cancer and COVID-19 remains inconclusive,” they wrote.

Though inconclusive, the findings raise questions about whether treatments or interventions might need to be postponed in certain patients, whether cancer patients and survivors need stronger personal protection, and how to deal with potential delays in cancer clinical trials, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“As the evidence continues to rise, we must strive to answer the unanswered clinical questions,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Desai and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Desai A et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00097.

An early report pegged the prevalence of cancer among COVID-19 patients at 1%, but authors of a recent meta-analysis found an overall prevalence of 2% and up to 3% depending on the subset of data they reviewed.

However, those findings are limited by the retrospective nature of the studies published to date, according to the authors of the meta-analysis, led by Aakash Desai, MBBS, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

Nevertheless, the results do confirm that cancer patients and survivors are an important at-risk population for COVID-19, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“We hope that additional data from China and Italy will provide information on the characteristics of patients with cancer at risk, types of cancer that confer higher risk, and systemic regimens that may increase COVID-19 infection complications,” the authors wrote in JCO Global Oncology.

More than 15 million individuals with cancer and many more cancer survivors are at increased risk of COVID-19 because of compromised immune systems, according to the authors.

Exactly how many individuals with cancer are among the COVID-19 cases remains unclear, though a previous report suggested the prevalence of cancer was 1% (95% confidence interval, 0.61%-1.65%) among COVID-19 patients in China (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:335-7). This “seems to be higher” than the 0.29% prevalence of cancer in the overall Chinese population, the investigators noted at the time.

That study revealed 18 cancer patients among 1,590 COVID-19 cases, though it was “hypothesis generating,” according to Dr. Desai and colleagues, who rolled that data into their meta-analysis of 11 reports including 3,661 COVID-19 cases.

Overall, Dr. Desai and colleagues found the pooled prevalence of cancer was 2.0% (95% CI, 2.0%-3.0%) in that population. In a subgroup analysis of five studies with sample sizes of less than 100 COVID-19 patients, the researchers found a “slightly higher” prevalence of 3.0% (95% CI, 1.0%-6.0%).

However, even that data wasn’t robust enough for Dr. Desai and colleagues to make any pronouncements on cancer prevalence. “Overall, current evidence on the association between cancer and COVID-19 remains inconclusive,” they wrote.

Though inconclusive, the findings raise questions about whether treatments or interventions might need to be postponed in certain patients, whether cancer patients and survivors need stronger personal protection, and how to deal with potential delays in cancer clinical trials, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“As the evidence continues to rise, we must strive to answer the unanswered clinical questions,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Desai and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Desai A et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00097.

An early report pegged the prevalence of cancer among COVID-19 patients at 1%, but authors of a recent meta-analysis found an overall prevalence of 2% and up to 3% depending on the subset of data they reviewed.

However, those findings are limited by the retrospective nature of the studies published to date, according to the authors of the meta-analysis, led by Aakash Desai, MBBS, of the University of Connecticut, Farmington.

Nevertheless, the results do confirm that cancer patients and survivors are an important at-risk population for COVID-19, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“We hope that additional data from China and Italy will provide information on the characteristics of patients with cancer at risk, types of cancer that confer higher risk, and systemic regimens that may increase COVID-19 infection complications,” the authors wrote in JCO Global Oncology.

More than 15 million individuals with cancer and many more cancer survivors are at increased risk of COVID-19 because of compromised immune systems, according to the authors.

Exactly how many individuals with cancer are among the COVID-19 cases remains unclear, though a previous report suggested the prevalence of cancer was 1% (95% confidence interval, 0.61%-1.65%) among COVID-19 patients in China (Lancet Oncol. 2020 Mar;21[3]:335-7). This “seems to be higher” than the 0.29% prevalence of cancer in the overall Chinese population, the investigators noted at the time.

That study revealed 18 cancer patients among 1,590 COVID-19 cases, though it was “hypothesis generating,” according to Dr. Desai and colleagues, who rolled that data into their meta-analysis of 11 reports including 3,661 COVID-19 cases.

Overall, Dr. Desai and colleagues found the pooled prevalence of cancer was 2.0% (95% CI, 2.0%-3.0%) in that population. In a subgroup analysis of five studies with sample sizes of less than 100 COVID-19 patients, the researchers found a “slightly higher” prevalence of 3.0% (95% CI, 1.0%-6.0%).

However, even that data wasn’t robust enough for Dr. Desai and colleagues to make any pronouncements on cancer prevalence. “Overall, current evidence on the association between cancer and COVID-19 remains inconclusive,” they wrote.

Though inconclusive, the findings raise questions about whether treatments or interventions might need to be postponed in certain patients, whether cancer patients and survivors need stronger personal protection, and how to deal with potential delays in cancer clinical trials, according to Dr. Desai and colleagues.

“As the evidence continues to rise, we must strive to answer the unanswered clinical questions,” the authors wrote.

Dr. Desai and colleagues reported no potential conflicts of interest related to the study.

SOURCE: Desai A et al. JCO Glob Oncol. 2020 Apr 6. doi: 10.1200/GO.20.00097.

FROM JCO GLOBAL ONCOLOGY

When to treat, delay, or omit breast cancer therapy in the face of COVID-19

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Nothing is business as usual during the COVID-19 pandemic, and that includes breast cancer therapy. That’s why two groups have released guidance documents on treating breast cancer patients during the pandemic.

A guidance on surgery, drug therapy, and radiotherapy was created by the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium. This guidance is set to be published in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment and can be downloaded from the American College of Surgeons website.

A group from Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSKCC) created a guidance document on radiotherapy for breast cancer patients, and that guidance was recently published in Advances in Radiation Oncology.

Prioritizing certain patients and treatments

As hospital beds and clinics fill with coronavirus-infected patients, oncologists must balance the need for timely therapy for their patients with the imperative to protect vulnerable, immunosuppressed patients from exposure and keep clinical resources as free as possible.

“As we’re taking care of breast cancer patients during this unprecedented pandemic, what we’re all trying to do is balance the most effective treatments for our patients against the risk of additional exposures, either from other patients [or] from being outside, and considerations about the safety of our staff,” said Steven Isakoff, MD, PhD, of Massachusetts General Hospital Cancer Center in Boston, who is an author of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance.

The consortium’s guidance recommends prioritizing treatment according to patient needs and the disease type and stage. The three basic categories for considering when to treat are:

- Priority A: Patients who have immediately life-threatening conditions, are clinically unstable, or would experience a significant change in prognosis with even a short delay in treatment.

- Priority B: Deferring treatment for a short time (6-12 weeks) would not impact overall outcomes in these patients.

- Priority C: These patients are stable enough that treatment can be delayed for the duration of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“The consortium highly recommends multidisciplinary discussion regarding priority for elective surgery and adjuvant treatments for your breast cancer patients,” the guidance authors wrote. “The COVID-19 pandemic may vary in severity over time, and these recommendations are subject to change with changing COVID-19 pandemic severity.”

For example, depending on local circumstances, the guidance recommends limiting immediate outpatient visits to patients with potentially unstable conditions such as infection or hematoma. Established patients with new problems or patients with a new diagnosis of noninvasive cancer might be managed with telemedicine visits, and patients who are on follow-up with no new issues or who have benign lesions might have their visits safely postponed.

Surgery and drug recommendations

High-priority surgical procedures include operative drainage of a breast abscess in a septic patient and evacuation of expanding hematoma in a hemodynamically unstable patient, according to the consortium guidance.

Other surgical situations are more nuanced. For example, for patients with triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) or HER2-positive disease, the guidance recommends neoadjuvant chemotherapy or HER2-targeted chemotherapy in some cases. In other cases, institutions may proceed with surgery before chemotherapy, but “these decisions will depend on institutional resources and patient factors,” according to the authors.

The guidance states that chemotherapy and other drug treatments should not be delayed in patients with oncologic emergencies, such as febrile neutropenia, hypercalcemia, intolerable pain, symptomatic pleural effusions, or brain metastases.

In addition, patients with inflammatory breast cancer, TNBC, or HER2-positive breast cancer should receive neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients with metastatic disease that is likely to benefit from therapy should start chemotherapy, endocrine therapy, or targeted therapy. And patients who have already started neoadjuvant/adjuvant chemotherapy or oral adjuvant endocrine therapy should continue on these treatments.

Radiation therapy recommendations

The consortium guidance recommends administering radiation to patients with bleeding or painful inoperable locoregional disease, those with symptomatic metastatic disease, and patients who progress on neoadjuvant chemotherapy.

In contrast, older patients (aged 65-70 years) with lower-risk, stage I, hormone receptor–positive, HER2-negative cancers who are on adjuvant endocrine therapy can safely defer or omit radiation without affecting their overall survival, according to the guidance. Patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, especially those with estrogen receptor–positive disease on endocrine therapy, can safely omit radiation.

“There are clearly conditions where radiation might reduce the risk of recurrence but not improve overall survival, where a delay in treatment really will have minimal or no impact,” Dr. Isakoff said.

The MSKCC guidance recommends omitting radiation for some patients with favorable-risk disease and truncating or accelerating regimens using hypofractionation for others who require whole-breast radiation or post-mastectomy treatment.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommendations for prioritization of patients according to disease state and the urgency of care. It divides cases into high, intermediate, and low priority for breast radiotherapy, as follows:

- Tier 1 (high priority): Patients with inflammatory breast cancer, residual node-positive disease after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, four or more positive nodes (N2), recurrent disease, node-positive TNBC, or extensive lymphovascular invasion.

- Tier 2 (intermediate priority): Patients with estrogen receptor–positive disease with one to three positive nodes (N1a), pathologic stage N0 after neoadjuvant chemotherapy, lymphovascular invasion not otherwise specified, or node-negative TNBC.

- Tier 3 (low priority): Patients with early-stage estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer (especially patients of advanced age), patients with ductal carcinoma in situ, or those who otherwise do not meet the criteria for tiers 1 or 2.

The MSKCC guidance also contains recommended hypofractionated or accelerated radiotherapy regimens for partial and whole-breast irradiation, post-mastectomy treatment, and breast and regional node irradiation, including recommended techniques (for example, 3-D conformal or intensity modulated approaches).

The authors of the MSKCC guidance disclosed relationships with eContour, Volastra Therapeutics, Sanofi, the Prostate Cancer Foundation, and Cancer Research UK. The authors of the COVID-19 Pandemic Breast Cancer Consortium guidance did not disclose any conflicts and said there was no funding source for the guidance.

SOURCES: Braunstein LZ et al. Adv Radiat Oncol. 2020 Apr 1. doi:10.1016/j.adro.2020.03.013; Dietz JR et al. 2020 Apr. Recommendations for prioritization, treatment and triage of breast cancer patients during the COVID-19 pandemic. Accepted for publication in Breast Cancer Research and Treatment.

Home-based chemo skyrockets at one U.S. center

Major organization opposes concept

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Major organization opposes concept

Major organization opposes concept

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In the fall of 2019, the University of Pennsylvania in Philadelphia started a pilot program of home-based chemotherapy for two treatment regimens (one via infusion and one via injection). Six months later, the Cancer Care at Home program had treated 40 patients.

The uptake within the university’s large regional health system was acceptable but not rapid, admitted Amy Laughlin, MD, a hematology-oncology fellow involved with the program.

Then COVID-19 arrived, along with related travel restrictions.

Suddenly, in a 5-week period (March to April 7), 175 patients had been treated – a 300% increase from the first half year. Program staff jumped from 12 to 80 employees. The list of chemotherapies delivered went from two to seven, with more coming.

“We’re not the pilot anymore – we’re the standard of care,” Laughlin told Medscape Medical News.

“The impact [on patients] is amazing,” she said. “As long as you are selecting the right patients and right therapy, it is feasible and even preferable for a lot of patients.”

For example, patients with hormone-positive breast cancer who receive leuprolide (to shut down the ovaries and suppress estrogen production) ordinarily would have to visit a Penn facility for an injection every month, potentially for years. Now, a nurse can meet patients at home (or before the COVID-19 pandemic, even at their place of work) and administer the injection, saving the patient travel time and associated costs.

This home-based chemotherapy service does not appear to be offered elsewhere in the United States, and a major oncology organization – the Community Oncology Alliance – is opposed to the practice because of patient safety concerns.

The service is not offered at a sample of cancer centers queried by Medscape Medical News, including the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute in Boston, the Moffitt Cancer Center in Tampa, the Huntsman Cancer Institute in Salt Lake City, Utah, and Moores Cancer Center, the University of California, San Diego.

Opposition because of safety concerns

On April 9, the Community Oncology Alliance (COA) issued a statement saying it “fundamentally opposes home infusion of chemotherapy, cancer immunotherapy, and cancer treatment supportive drugs because of serious patient safety concerns.”

The COA warned that “many of the side effects caused by cancer treatment can have a rapid, unpredictable onset that places patients in incredible jeopardy and can even be life-threatening.”

In contrast, in a recent communication related to COVID-19, the National Comprehensive Cancer Network tacitly endorsed the concept, stating that a number of chemotherapies may potentially be administered at home, but it did not include guidelines for doing so.

The American Society of Clinical Oncology said that chemotherapy at home is “an issue [we] are monitoring closely,” according to a spokesperson.

What’s involved

Criteria for home-based chemotherapy at Penn include use of anticancer therapies that a patient has previously tolerated and low toxicity (that can be readily managed in the home setting). In addition, patients must be capable of following a med chart.

The chemotherapy is reconstituted at a Penn facility in a Philadelphia suburb. A courier then delivers the drug to the patient’s home, where it is administered by an oncology-trained nurse. Drugs must be stable for at least a few hours to qualify for the program.

The Penn program started with two regimens: EPOCH (etoposide, vincristine, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, and prednisone) for lymphoma, and leuprolide acetate injections for either breast or prostate cancer.

The two treatments are polar opposites in terms of complexity, common usage, and time required, which was intended, said Laughlin.

Time to deliver the chemo varies from a matter of minutes with leuprolide to more than 2 hours for rituximab, a lymphoma drug that may be added to EPOCH.

The current list of at-home chemo agents in the Penn program also includes bortezomib, lanreotide, zoledronic acid, and denosumab. Soon to come are rituximab and pembrolizumab for lung cancer and head and neck cancer.

Already practiced in some European countries

Home-based chemotherapy dates from at least the 1980s in the medical literature and is practiced in some European countries.

A 2018 randomized study of adjuvant treatment with capecitabine and oxaliplatin for stage II/III colon cancer in Denmark, where home-based care has been practiced for the past 2 years and is growing in use, concluded that “it might be a valuable alternative to treatment at an outpatient clinic.”

However, in the study, there was no difference in quality of life between the home and outpatient settings, which is somewhat surprising, inasmuch as a major appeal to receiving chemotherapy at home is that it is less disruptive compared to receiving it in a hospital or clinic, which requires travel.

Also, chemo at home “may be resource intensive” and have a “lower throughput of patients due to transportation time,” cautioned the Danish investigators, who were from Herlev and Gentofte Hospital.

A 2015 review called home chemo “a safe and patient‐centered alternative to hospital‐ and outpatient‐based service.” Jenna Evans, PhD, McMaster University, Toronto, Canada, and lead author of that review, says there are two major barriers to infusion chemotherapy in homes.

One is inadequate resources in the community, such as oncology-trained nurses to deliver treatment, and the other is perceptions of safety and quality, including among healthcare providers.

COVID-19 might prompt more chemo at home, said Evans, a health policy expert, in an email to Medscape Medical News. “It is not unusual for change of this type and scale to require a seismic event to become more mainstream,” she argued.

Reimbursement for home-based chemo is usually the same as for chemo in a free-standing infusion suite, says Cassandra Redmond, PharmD, MBA, director of pharmacy, Penn Home Infusion Therapy.

Private insurers and Medicare cover a subset of infused medications at home, but coverage is limited. “The opportunity now is to expand these initiatives ... to include other cancer therapies,” she said about coverage.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Managing pediatric heme/onc departments during the pandemic

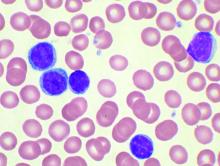

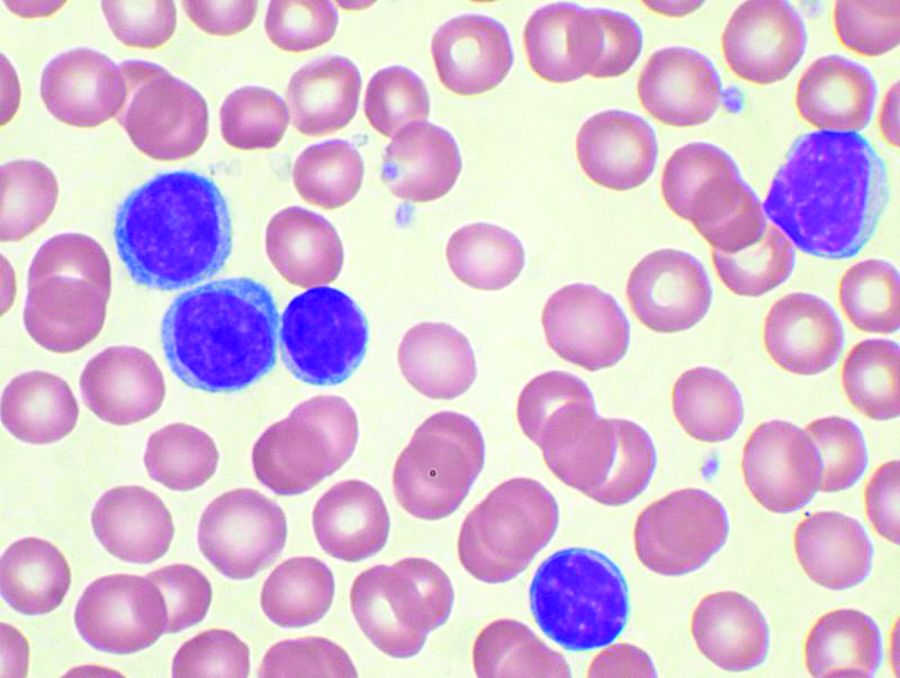

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

Given the possibility that children with hematologic malignancies may have increased susceptibility to coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), clinicians from China and the United States have proposed a plan for preventing and managing outbreaks in hospitals’ pediatric hematology and oncology departments.

The plan is focused primarily on infection prevention and control strategies, Yulei He, MD, of Chengdu (China) Women’s and Children’s Central Hospital and colleagues explained in an article published in The Lancet Haematology.

The authors noted that close contact with COVID-19 patients is thought to be the main route of transmission, and a retrospective study indicated that 41.3% of initial COVID-19 cases were caused by hospital-related transmission.

“Children with hematological malignancies might have increased susceptibility to infection with SARS-CoV-2 because of immunodeficiency; therefore, procedures are needed to avoid hospital-related transmission and infection for these patients,” the authors wrote.

Preventing the spread of infection

Dr. He and colleagues advised that medical staff be kept up-to-date with the latest information about COVID-19 and perform assessments regularly to identify cases in their departments.

The authors also recommended establishing a COVID-19 expert committee – consisting of infectious disease physicians, hematologists, oncologists, radiologists, pharmacists, and hospital infection control staff – to make medical decisions in multidisciplinary consultation meetings. In addition, the authors recommended regional management strategies be adopted to minimize cross infection within the hospital. Specifically, the authors proposed creating the following four zones:

1. A surveillance and screening zone for patients potentially infected with SARS-CoV-2

2. A suspected-case quarantine zone where patients thought to have COVID-19 are isolated in single rooms

3. A confirmed-case quarantine zone where patients are treated for COVID-19

4. A hematology/oncology ward for treating non–COVID-19 patients with malignancies.

Dr. He and colleagues also stressed the importance of providing personal protective equipment for all zones, along with instructions for proper use and disposal. The authors recommended developing and following specific protocols for outpatient visits in the hematology/oncology ward, and providing COVID-19 prevention and control information to families and health care workers.

Managing cancer treatment

For patients with acute leukemias who have induction chemotherapy planned, Dr. He and colleagues argued that scheduled chemotherapy should not be interrupted unless COVID-19 is suspected or diagnosed. The authors said treatment should not be delayed more than 7 days during induction, consolidation, or the intermediate phase of chemotherapy because the virus has an incubation period of 2-7 days. This will allow a short period of observation to screen for potential infection.

The authors recommended that patients with lymphoma and solid tumors first undergo COVID-19 screening and then receive treatment in hematology/oncology wards “according to their chemotherapy schedule, and without delay, until they are in complete remission.”

“If the patient is in complete remission, we recommend a treatment delay of no more than 7 days to allow a short period of observation to screen for COVID-19,” the authors added.

Maintenance chemotherapy should not be delayed for more than 14 days, Dr. He and colleagues wrote. “This increase in the maximum delay before chemotherapy strikes a balance between the potential risk of SARS-CoV-2 infection and tumor recurrence, since pediatric patients in this phase of treatment have a reduced risk of tumor recurrence,” the authors added.

Caring for patients with COVID-19

For inpatients diagnosed with COVID-19, Dr. He and colleagues recommended the following:

- Prioritize COVID-19 treatment for children with primary disease remission.

- For children not in remission, prioritize treatment for critical patients.

- Isolated patients should be treated for COVID-19, and their chemotherapy should be temporarily suspended or reduced in intensity..

Dr. He and colleagues noted that, by following these recommendations for infection prevention, they had no cases of COVID-19 among children in their hematology/oncology departments. However, the authors said the recommendations “could fail to some extent” based on “differences in medical resources, health care settings, and the policy of the specific government.”

The authors said their recommendations should be updated continuously as new information and clinical evidence emerges.

Dr. He and colleagues reported having no conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: He Y et al. Lancet Haematol. doi: 10/1016/s2352-3026(20)30104-6.

FROM THE LANCET HAEMATOLOGY

Colorectal cancer: Proposed treatment guidelines for the COVID-19 era

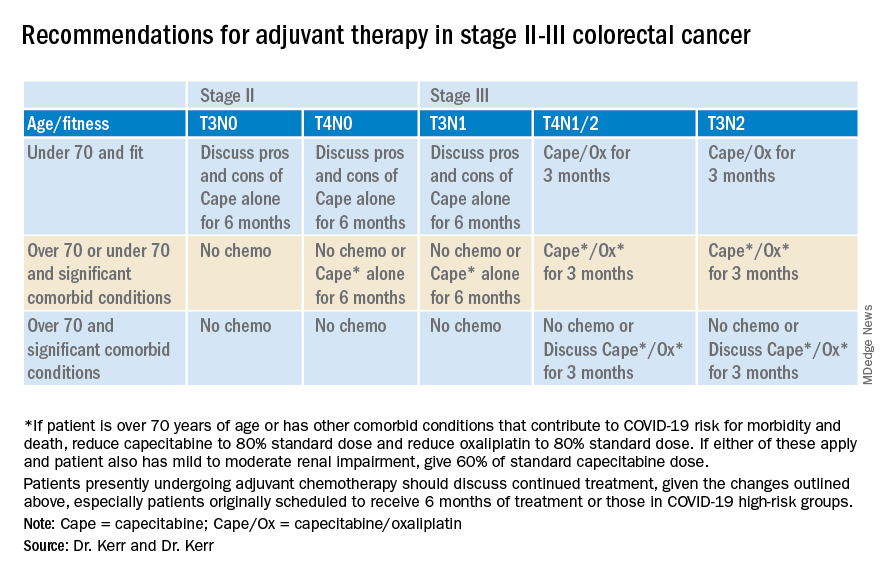

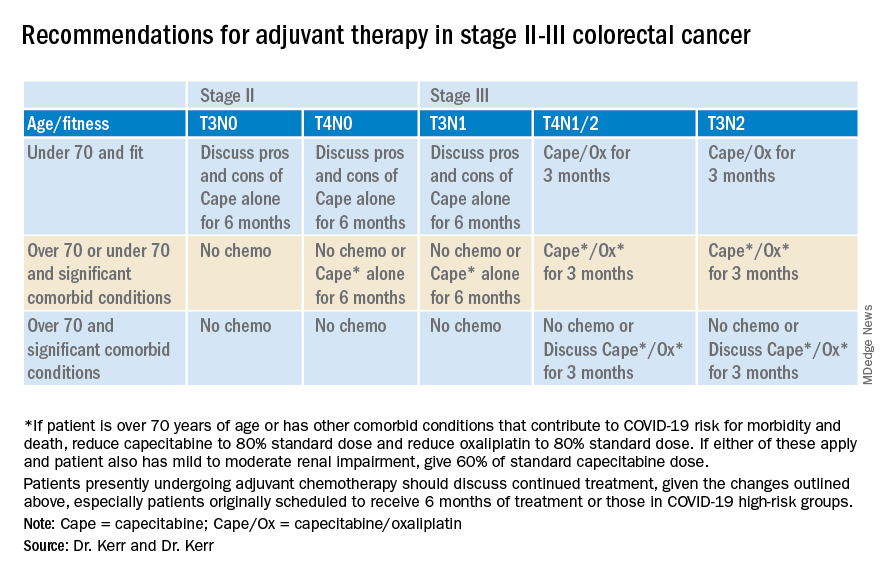

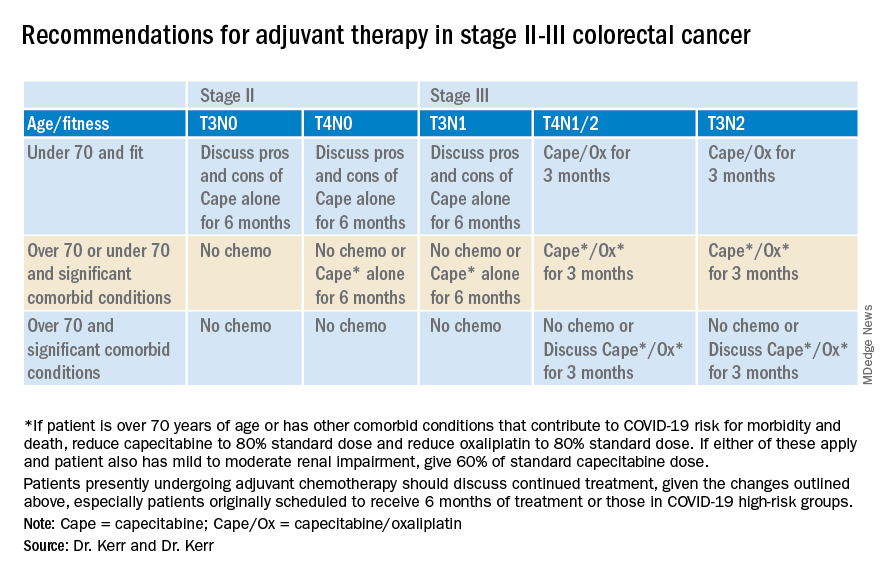

In light of the rapid changes affecting cancer clinics due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. David Kerr and Dr. Rachel Kerr, both specialists in gastrointestinal cancers at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, drafted these guidelines for the use of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Dr. Kerr and Dr. Kerr are putting forth this guidance as a topic for discussion and debate.

Our aim in developing these recommendations for the care of colorectal cancer patients in areas affected by the COVID-19 outbreak is to reduce the comorbidity of chemotherapy and decrease the risk of patients dying from COVID-19, weighed against the potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy. These recommendations are also designed to reduce the burden on chemotherapy units during a time of great pressure.

We have modified the guidelines in such a way that, we believe, will decrease the total number of patients receiving chemotherapy – particularly in the adjuvant setting – and reduce the overall immune impact of chemotherapy on these patients. Specifically, we suggest changing doublet chemotherapy to single-agent chemotherapy for some groups; changing to combinations involving capecitabine rather than bolus and infusional 5-FU for other patients; and, finally, making reasonable dose reductions upfront to reduce the risk for cycle 1 complications.

By changing from push-and-pump 5-FU to capecitabine for the vast majority of patients, we will both reduce the rates of neutropenia and decrease throughput in chemotherapy outpatient units, reducing requirements for weekly line flushing, pump disconnections, and other routine maintenance.

We continue to recommend the use of ToxNav germline genetic testing as a genetic screen for DPYD/ENOSF1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to identify patients at high risk for fluoropyrimidine toxicity.

Use of biomarkers to sharpen prognosis should also be considered to refine therapeutic decisions.

Recommendations for stage II-III colorectal cancer

Recommendations for advanced colorectal cancer

Which regimen? Capecitabine/oxaliplatin should be the default backbone chemotherapy (rather than FOLFOX) in order to decrease the stress on infusion units.

Capecitabine plus irinotecan should be considered rather than FOLFIRI. However, in order to increase safety, reduce the dose of the capecitabine and the irinotecan, both to 80%, in all patient groups; and perhaps reduce the capecitabine dose further to 60% in those over the age of 70 or with significant comorbid conditions.

Treatment breaks. Full treatment breaks should be considered after 3 months of treatment in most patients with lower-volume, more indolent disease.

Treatment deintensification to capecitabine alone should be used in those with higher-volume disease (for example, more than 50% of liver replaced by tumor) at the beginning of treatment.

Deferring the start of any chemotherapy. Some older patients, or those with significant other comorbidities (that is, those who will be at increased risk for COVID-19 complications and death); who have low-volume disease, such as a couple of small lung metastases or a single liver metastasis; or who were diagnosed more than 12 months since adjuvant chemotherapy may decide to defer any chemotherapy for a period of time.

In these cases, we suggest rescanning at 3 months and discussing further treatment at that point. Some of these patients will be eligible for other interventions, such as resection, ablation, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. However, it will be important to consider the pressures on these other services during this unprecedented time.

Chemotherapy after resection of metastases. Given the lack of evidence and the present extenuating circumstances, we would not recommend any chemotherapy in this setting.

David J. Kerr, MD, CBE, MD, DSc, is a professor of cancer medicine at the University of Oxford. He is recognized internationally for his work in the research and treatment of colorectal cancer, and has founded three university spin-out companies: COBRA Therapeutics, Celleron Therapeutics, and Oxford Cancer Biomarkers. In 2002, he was appointed Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth. Rachel S. Kerr, MBChB, is a medical oncologist and associate professor of gastrointestinal oncology at the University of Oxford. She holds a UK Department of Health Fellowship, where she is clinical director of phase 3 trials in the oncology clinical trials office.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In light of the rapid changes affecting cancer clinics due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. David Kerr and Dr. Rachel Kerr, both specialists in gastrointestinal cancers at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, drafted these guidelines for the use of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Dr. Kerr and Dr. Kerr are putting forth this guidance as a topic for discussion and debate.

Our aim in developing these recommendations for the care of colorectal cancer patients in areas affected by the COVID-19 outbreak is to reduce the comorbidity of chemotherapy and decrease the risk of patients dying from COVID-19, weighed against the potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy. These recommendations are also designed to reduce the burden on chemotherapy units during a time of great pressure.

We have modified the guidelines in such a way that, we believe, will decrease the total number of patients receiving chemotherapy – particularly in the adjuvant setting – and reduce the overall immune impact of chemotherapy on these patients. Specifically, we suggest changing doublet chemotherapy to single-agent chemotherapy for some groups; changing to combinations involving capecitabine rather than bolus and infusional 5-FU for other patients; and, finally, making reasonable dose reductions upfront to reduce the risk for cycle 1 complications.

By changing from push-and-pump 5-FU to capecitabine for the vast majority of patients, we will both reduce the rates of neutropenia and decrease throughput in chemotherapy outpatient units, reducing requirements for weekly line flushing, pump disconnections, and other routine maintenance.

We continue to recommend the use of ToxNav germline genetic testing as a genetic screen for DPYD/ENOSF1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to identify patients at high risk for fluoropyrimidine toxicity.

Use of biomarkers to sharpen prognosis should also be considered to refine therapeutic decisions.

Recommendations for stage II-III colorectal cancer

Recommendations for advanced colorectal cancer

Which regimen? Capecitabine/oxaliplatin should be the default backbone chemotherapy (rather than FOLFOX) in order to decrease the stress on infusion units.

Capecitabine plus irinotecan should be considered rather than FOLFIRI. However, in order to increase safety, reduce the dose of the capecitabine and the irinotecan, both to 80%, in all patient groups; and perhaps reduce the capecitabine dose further to 60% in those over the age of 70 or with significant comorbid conditions.

Treatment breaks. Full treatment breaks should be considered after 3 months of treatment in most patients with lower-volume, more indolent disease.

Treatment deintensification to capecitabine alone should be used in those with higher-volume disease (for example, more than 50% of liver replaced by tumor) at the beginning of treatment.

Deferring the start of any chemotherapy. Some older patients, or those with significant other comorbidities (that is, those who will be at increased risk for COVID-19 complications and death); who have low-volume disease, such as a couple of small lung metastases or a single liver metastasis; or who were diagnosed more than 12 months since adjuvant chemotherapy may decide to defer any chemotherapy for a period of time.

In these cases, we suggest rescanning at 3 months and discussing further treatment at that point. Some of these patients will be eligible for other interventions, such as resection, ablation, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. However, it will be important to consider the pressures on these other services during this unprecedented time.

Chemotherapy after resection of metastases. Given the lack of evidence and the present extenuating circumstances, we would not recommend any chemotherapy in this setting.

David J. Kerr, MD, CBE, MD, DSc, is a professor of cancer medicine at the University of Oxford. He is recognized internationally for his work in the research and treatment of colorectal cancer, and has founded three university spin-out companies: COBRA Therapeutics, Celleron Therapeutics, and Oxford Cancer Biomarkers. In 2002, he was appointed Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth. Rachel S. Kerr, MBChB, is a medical oncologist and associate professor of gastrointestinal oncology at the University of Oxford. She holds a UK Department of Health Fellowship, where she is clinical director of phase 3 trials in the oncology clinical trials office.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

In light of the rapid changes affecting cancer clinics due to the COVID-19 pandemic, Dr. David Kerr and Dr. Rachel Kerr, both specialists in gastrointestinal cancers at the University of Oxford in Oxford, United Kingdom, drafted these guidelines for the use of chemotherapy in colorectal cancer patients. Dr. Kerr and Dr. Kerr are putting forth this guidance as a topic for discussion and debate.

Our aim in developing these recommendations for the care of colorectal cancer patients in areas affected by the COVID-19 outbreak is to reduce the comorbidity of chemotherapy and decrease the risk of patients dying from COVID-19, weighed against the potential benefits of receiving chemotherapy. These recommendations are also designed to reduce the burden on chemotherapy units during a time of great pressure.

We have modified the guidelines in such a way that, we believe, will decrease the total number of patients receiving chemotherapy – particularly in the adjuvant setting – and reduce the overall immune impact of chemotherapy on these patients. Specifically, we suggest changing doublet chemotherapy to single-agent chemotherapy for some groups; changing to combinations involving capecitabine rather than bolus and infusional 5-FU for other patients; and, finally, making reasonable dose reductions upfront to reduce the risk for cycle 1 complications.

By changing from push-and-pump 5-FU to capecitabine for the vast majority of patients, we will both reduce the rates of neutropenia and decrease throughput in chemotherapy outpatient units, reducing requirements for weekly line flushing, pump disconnections, and other routine maintenance.

We continue to recommend the use of ToxNav germline genetic testing as a genetic screen for DPYD/ENOSF1 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) to identify patients at high risk for fluoropyrimidine toxicity.

Use of biomarkers to sharpen prognosis should also be considered to refine therapeutic decisions.

Recommendations for stage II-III colorectal cancer

Recommendations for advanced colorectal cancer

Which regimen? Capecitabine/oxaliplatin should be the default backbone chemotherapy (rather than FOLFOX) in order to decrease the stress on infusion units.

Capecitabine plus irinotecan should be considered rather than FOLFIRI. However, in order to increase safety, reduce the dose of the capecitabine and the irinotecan, both to 80%, in all patient groups; and perhaps reduce the capecitabine dose further to 60% in those over the age of 70 or with significant comorbid conditions.

Treatment breaks. Full treatment breaks should be considered after 3 months of treatment in most patients with lower-volume, more indolent disease.

Treatment deintensification to capecitabine alone should be used in those with higher-volume disease (for example, more than 50% of liver replaced by tumor) at the beginning of treatment.

Deferring the start of any chemotherapy. Some older patients, or those with significant other comorbidities (that is, those who will be at increased risk for COVID-19 complications and death); who have low-volume disease, such as a couple of small lung metastases or a single liver metastasis; or who were diagnosed more than 12 months since adjuvant chemotherapy may decide to defer any chemotherapy for a period of time.

In these cases, we suggest rescanning at 3 months and discussing further treatment at that point. Some of these patients will be eligible for other interventions, such as resection, ablation, or stereotactic body radiation therapy. However, it will be important to consider the pressures on these other services during this unprecedented time.

Chemotherapy after resection of metastases. Given the lack of evidence and the present extenuating circumstances, we would not recommend any chemotherapy in this setting.

David J. Kerr, MD, CBE, MD, DSc, is a professor of cancer medicine at the University of Oxford. He is recognized internationally for his work in the research and treatment of colorectal cancer, and has founded three university spin-out companies: COBRA Therapeutics, Celleron Therapeutics, and Oxford Cancer Biomarkers. In 2002, he was appointed Commander of the British Empire by Queen Elizabeth. Rachel S. Kerr, MBChB, is a medical oncologist and associate professor of gastrointestinal oncology at the University of Oxford. She holds a UK Department of Health Fellowship, where she is clinical director of phase 3 trials in the oncology clinical trials office.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

National Watchman registry reports impressive procedural safety