User login

AVAHO

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

New registry focuses on rheumatic immune-related AEs of cancer therapy

Its first findings were reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, held online this year due to COVID-19.

“We have limited knowledge on the interrelationships between malignant and rheumatic diseases on both the clinical and molecular level, and we have a large unmet need for management guidelines in the case of the coincidence of both disease entities,” noted lead author Karolina Benesova, MD, of the department of hematology, oncology, and rheumatology at University Hospital Heidelberg (Germany).

The TRheuMa registry – Therapy-Induced Rheumatic Symptoms in Patients with Malignancy – is one of three registries in a multicenter observational project exploring various contexts between malignant and rheumatic diseases. Over its first 22 months, the registry recruited 69 patients having rheumatic symptoms as a result of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or other cancer therapies.

Registry findings

The largest shares of patients had non–small cell lung cancer (38%) or melanoma (33%), Dr. Benesova reported. The immune checkpoint inhibitors most commonly received were pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), and ipilimumab (Yervoy).

The immune-related adverse events usually presented with symptoms of de novo spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis (42%), late-onset RA (17%), or polymyalgia rheumatica (14%). But 16% of the patients were experiencing a flare of a preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Laboratory findings differed somewhat from those of classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, according to Dr. Benesova. Specific findings were rare; in particular, most patients did not have detectable autoantibodies. However, 76% had an elevated C-reactive protein level and 39% had an elevated soluble CD25 level. In addition, nearly all patients (96%) undergoing joint ultrasound had pathologic findings.

“Based on our experiences from interdisciplinary care together with our local oncologists, we have developed a therapeutic algorithm for rheumatic immune-related adverse events,” she reported, noting that the algorithm is consistent with recently published recommendations in this area.

The large majority of patients were adequately treated with prednisone at a dose greater than 10 mg (40%) or at a dose of 10 mg or less with or without an NSAID (40%), while some received NSAID monotherapy (14%).

“We have a growing proportion of patients on conventional or biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs],” Dr. Benesova noted. “These are mostly patients with preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease or highly suspected de novo classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease under checkpoint inhibitor therapy.”

Patients with melanoma having a rheumatic immune-related adverse event had a better response to their therapy than historical counterparts who did not have such events: 39% of the former had a complete response, relative to merely 4% of the latter.

Only a small proportion of patients overall (9%) had to discontinue immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy because of their adverse event, and some of them may be eligible for rechallenge if their cancer progresses, Dr. Benesova noted.

“There is still a lot to be done,” she stated, such as better elucidating the nature of these adverse events [whether transient side effects or a triggering of chronic rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases], the need for a defensive treatment strategy, and the advisability of closer monitoring of high-risk patients given immune checkpoint inhibitors. “We are aiming at solving these questions in the next few years,” she concluded.

Findings in context

“Registries are important to gain prospective data on patient outcomes,” Sabina Sandigursky, MD, an instructor in the division of rheumatology at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, commented in an interview. “One must be careful, while interpreting these data, especially since they are not randomized, controlled trials.”

Patterns may differ at other centers, too, she pointed out. “The German registry reported a predominance of spondyloarthritis-like disease; however, our patients have a predominance of small-joint involvement. It is unclear what accounts for this difference.”

Individual institutions in North America are similarly collecting data on this patient population, with efforts underway to compile those data to provide a larger picture, according to Dr. Sandigursky.

“Many of the syndromes that we consider to be rheumatic immune-related adverse events have been well described by groups from the U.S., Canada, Australia, and European Union,” she concluded. “From this registry, we can observe how patients are being treated in real time since this information is largely consensus based.”

The study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Benesova disclosed grant/research support from AbbVie, Novartis, Rheumaliga Baden-Wurttemberg, and the University of Heidelberg, and consultancies, speaker fees, and/or travel reimbursements from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Some of her coauthors also disclosed financial relationships with industry. Dr. Sandigursky disclosed having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Benesova K et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79[suppl 1]:168-9, Abstract OP0270.

Its first findings were reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, held online this year due to COVID-19.

“We have limited knowledge on the interrelationships between malignant and rheumatic diseases on both the clinical and molecular level, and we have a large unmet need for management guidelines in the case of the coincidence of both disease entities,” noted lead author Karolina Benesova, MD, of the department of hematology, oncology, and rheumatology at University Hospital Heidelberg (Germany).

The TRheuMa registry – Therapy-Induced Rheumatic Symptoms in Patients with Malignancy – is one of three registries in a multicenter observational project exploring various contexts between malignant and rheumatic diseases. Over its first 22 months, the registry recruited 69 patients having rheumatic symptoms as a result of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or other cancer therapies.

Registry findings

The largest shares of patients had non–small cell lung cancer (38%) or melanoma (33%), Dr. Benesova reported. The immune checkpoint inhibitors most commonly received were pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), and ipilimumab (Yervoy).

The immune-related adverse events usually presented with symptoms of de novo spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis (42%), late-onset RA (17%), or polymyalgia rheumatica (14%). But 16% of the patients were experiencing a flare of a preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Laboratory findings differed somewhat from those of classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, according to Dr. Benesova. Specific findings were rare; in particular, most patients did not have detectable autoantibodies. However, 76% had an elevated C-reactive protein level and 39% had an elevated soluble CD25 level. In addition, nearly all patients (96%) undergoing joint ultrasound had pathologic findings.

“Based on our experiences from interdisciplinary care together with our local oncologists, we have developed a therapeutic algorithm for rheumatic immune-related adverse events,” she reported, noting that the algorithm is consistent with recently published recommendations in this area.

The large majority of patients were adequately treated with prednisone at a dose greater than 10 mg (40%) or at a dose of 10 mg or less with or without an NSAID (40%), while some received NSAID monotherapy (14%).

“We have a growing proportion of patients on conventional or biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs],” Dr. Benesova noted. “These are mostly patients with preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease or highly suspected de novo classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease under checkpoint inhibitor therapy.”

Patients with melanoma having a rheumatic immune-related adverse event had a better response to their therapy than historical counterparts who did not have such events: 39% of the former had a complete response, relative to merely 4% of the latter.

Only a small proportion of patients overall (9%) had to discontinue immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy because of their adverse event, and some of them may be eligible for rechallenge if their cancer progresses, Dr. Benesova noted.

“There is still a lot to be done,” she stated, such as better elucidating the nature of these adverse events [whether transient side effects or a triggering of chronic rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases], the need for a defensive treatment strategy, and the advisability of closer monitoring of high-risk patients given immune checkpoint inhibitors. “We are aiming at solving these questions in the next few years,” she concluded.

Findings in context

“Registries are important to gain prospective data on patient outcomes,” Sabina Sandigursky, MD, an instructor in the division of rheumatology at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, commented in an interview. “One must be careful, while interpreting these data, especially since they are not randomized, controlled trials.”

Patterns may differ at other centers, too, she pointed out. “The German registry reported a predominance of spondyloarthritis-like disease; however, our patients have a predominance of small-joint involvement. It is unclear what accounts for this difference.”

Individual institutions in North America are similarly collecting data on this patient population, with efforts underway to compile those data to provide a larger picture, according to Dr. Sandigursky.

“Many of the syndromes that we consider to be rheumatic immune-related adverse events have been well described by groups from the U.S., Canada, Australia, and European Union,” she concluded. “From this registry, we can observe how patients are being treated in real time since this information is largely consensus based.”

The study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Benesova disclosed grant/research support from AbbVie, Novartis, Rheumaliga Baden-Wurttemberg, and the University of Heidelberg, and consultancies, speaker fees, and/or travel reimbursements from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Some of her coauthors also disclosed financial relationships with industry. Dr. Sandigursky disclosed having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Benesova K et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79[suppl 1]:168-9, Abstract OP0270.

Its first findings were reported at the annual European Congress of Rheumatology, held online this year due to COVID-19.

“We have limited knowledge on the interrelationships between malignant and rheumatic diseases on both the clinical and molecular level, and we have a large unmet need for management guidelines in the case of the coincidence of both disease entities,” noted lead author Karolina Benesova, MD, of the department of hematology, oncology, and rheumatology at University Hospital Heidelberg (Germany).

The TRheuMa registry – Therapy-Induced Rheumatic Symptoms in Patients with Malignancy – is one of three registries in a multicenter observational project exploring various contexts between malignant and rheumatic diseases. Over its first 22 months, the registry recruited 69 patients having rheumatic symptoms as a result of immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy or other cancer therapies.

Registry findings

The largest shares of patients had non–small cell lung cancer (38%) or melanoma (33%), Dr. Benesova reported. The immune checkpoint inhibitors most commonly received were pembrolizumab (Keytruda), nivolumab (Opdivo), and ipilimumab (Yervoy).

The immune-related adverse events usually presented with symptoms of de novo spondyloarthritis or psoriatic arthritis (42%), late-onset RA (17%), or polymyalgia rheumatica (14%). But 16% of the patients were experiencing a flare of a preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease.

Laboratory findings differed somewhat from those of classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases, according to Dr. Benesova. Specific findings were rare; in particular, most patients did not have detectable autoantibodies. However, 76% had an elevated C-reactive protein level and 39% had an elevated soluble CD25 level. In addition, nearly all patients (96%) undergoing joint ultrasound had pathologic findings.

“Based on our experiences from interdisciplinary care together with our local oncologists, we have developed a therapeutic algorithm for rheumatic immune-related adverse events,” she reported, noting that the algorithm is consistent with recently published recommendations in this area.

The large majority of patients were adequately treated with prednisone at a dose greater than 10 mg (40%) or at a dose of 10 mg or less with or without an NSAID (40%), while some received NSAID monotherapy (14%).

“We have a growing proportion of patients on conventional or biological [disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs],” Dr. Benesova noted. “These are mostly patients with preexisting rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease or highly suspected de novo classical rheumatic and musculoskeletal disease under checkpoint inhibitor therapy.”

Patients with melanoma having a rheumatic immune-related adverse event had a better response to their therapy than historical counterparts who did not have such events: 39% of the former had a complete response, relative to merely 4% of the latter.

Only a small proportion of patients overall (9%) had to discontinue immune checkpoint inhibitor therapy because of their adverse event, and some of them may be eligible for rechallenge if their cancer progresses, Dr. Benesova noted.

“There is still a lot to be done,” she stated, such as better elucidating the nature of these adverse events [whether transient side effects or a triggering of chronic rheumatic and musculoskeletal diseases], the need for a defensive treatment strategy, and the advisability of closer monitoring of high-risk patients given immune checkpoint inhibitors. “We are aiming at solving these questions in the next few years,” she concluded.

Findings in context

“Registries are important to gain prospective data on patient outcomes,” Sabina Sandigursky, MD, an instructor in the division of rheumatology at the Laura and Isaac Perlmutter Cancer Center at New York University, commented in an interview. “One must be careful, while interpreting these data, especially since they are not randomized, controlled trials.”

Patterns may differ at other centers, too, she pointed out. “The German registry reported a predominance of spondyloarthritis-like disease; however, our patients have a predominance of small-joint involvement. It is unclear what accounts for this difference.”

Individual institutions in North America are similarly collecting data on this patient population, with efforts underway to compile those data to provide a larger picture, according to Dr. Sandigursky.

“Many of the syndromes that we consider to be rheumatic immune-related adverse events have been well described by groups from the U.S., Canada, Australia, and European Union,” she concluded. “From this registry, we can observe how patients are being treated in real time since this information is largely consensus based.”

The study did not receive any specific funding. Dr. Benesova disclosed grant/research support from AbbVie, Novartis, Rheumaliga Baden-Wurttemberg, and the University of Heidelberg, and consultancies, speaker fees, and/or travel reimbursements from AbbVie, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Gilead, Janssen, Medac, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Mundipharma, Novartis, Pfizer, Roche, and UCB. Some of her coauthors also disclosed financial relationships with industry. Dr. Sandigursky disclosed having no relevant conflicts of interest.

SOURCE: Benesova K et al. Ann Rheum Dis 2020;79[suppl 1]:168-9, Abstract OP0270.

FROM THE EULAR 2020 E-CONGRESS

Vulvar melanoma is increasing in older women

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

Maia K. Erickson reported in a poster at the virtual annual meeting of the American Academy of Dermatology.

These are often aggressive malignancies. The 5-year survival following diagnosis of vulvar melanoma in women aged 60 years or older was 39.7%, compared with 61.9% in younger women, according to Ms. Erickson, a visiting research fellow in the department of dermatology at Northwestern University, Chicago.

She presented a population-based study of epidemiologic trends in vulvar melanoma based upon analysis of the National Cancer Institute’s Surveillance, Epidemiology and End Results database. Vulvar melanoma was rare during the study years 2000-2016, with an overall incidence rate of 0.1 cases per 100,000 women. That worked out to 746 analyzable cases. Of note, the incidence rate ratio was 680% higher in older women (age 60 and older).

One reason for the markedly worse 5-year survival in older women was that the predominant histologic subtype of vulvar melanoma in that population was nodular melanoma, accounting for 48% of the cases where a histologic subtype was specified. In contrast, the less-aggressive superficial spreading melanoma subtype prevailed in patients aged under 60 years, accounting for 63% of cases.

About 93% of vulvar melanomas occurred in whites; 63% were local and 8.7% were metastatic.

Ms. Erickson noted that the vulva is the most common site for gynecologic tract melanomas, accounting for 70% of them. And while the female genitalia make up only 1%-2% of body surface area, that’s the anatomic site of up to 7% of all melanomas in women.

She reported having no financial conflicts regarding her study.

FROM AAD 2020

Gardasil-9 approved for prevention of head and neck cancers

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) has expanded the indication for the Gardasil-9 (Merck) vaccine to include prevention of oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers caused by HPV types 16, 18, 31, 33, 45, 52, and 58.

This new indication is approved under the FDA’s accelerated approval program and is based on the vaccine’s effectiveness in preventing HPV-related anogenital disease. Continued approval for this indication may be contingent upon verification and description of clinical benefit in a confirmatory clinical trial, which is currently underway.

“At Merck, working to help prevent certain HPV-related cancers has been a priority for more than two decades,” Alain Luxembourg, MD, director, clinical research, Merck Research Laboratories, said in a statement. “Today’s approval for the prevention of HPV-related oropharyngeal and other head and neck cancers represents an important step in Merck’s mission to help reduce the number of men and women affected by certain HPV-related cancers.”

This new indication doesn’t affect the current recommendations that are already in place. In 2018, a supplemental application for Gardasil 9 was approved to include women and men aged 27 through 45 years for preventing a variety of cancers including cervical, vulvar, vaginal, and anal cancer as well as genital warts. But cancers of the head and neck were not included.

The original Gardasil vaccine came on the market in 2006, with an indication to prevent certain cancers and diseases caused by HPV types 6, 11, 16, and 18. It is no longer distributed in the United States.

In 2014, the FDA approved Gardasil 9, which extends the vaccine coverage for the initial four HPV types as five additional types (31, 33, 45, 52, and 58), and its initial indication was for use in both men and women between the ages of 9 through 26 years.

Head and neck cancers surpass cervical cancer

More than 2 decades ago, researchers first found a connection between HPV and a subset of head and neck cancers (Curr Opin Oncol. 1999;11(3):191-199). The cancers associated with HPV also appeared to have a different biology and disease pattern, as well as a better prognosis, compared with those that were unrelated. HPV is now responsible for the majority of oropharyngeal squamous cell cancers diagnosed in the United States.

A study published last year found that oral HPV infections were occurring with significantly less frequency among sexually active female adolescents who had received the quadrivalent vaccine, as compared with those who were unvaccinated.

These findings provided evidence that HPV vaccination was associated with a reduced frequency of HPV infection in the oral cavity, suggesting that vaccination could decrease the future risk of HPV-associated head and neck cancers.

The omission of head and neck cancers from the initial list of indications for the vaccine is notable because, according to data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), oropharyngeal cancers are now the most common malignancy caused by HPV, surpassing cervical cancer.

Who will benefit?

An estimated 14 million new HPV infections occur every year in the United States, according to the CDC, and about 80% of individuals who are sexually active have been exposed at some point during their lifetime. In most people, however, the virus will clear on its own without causing any illness or symptoms.

In a Medscape videoblog, Sandra Adamson Fryhofer, MD, MACP, FRCP, helped clarify the adult population most likely to benefit from the vaccine. She pointed out that the HPV vaccine doesn’t treat HPV-related disease or help clear infections, and there are currently no clinical antibody tests or titers that can predict immunity.

“Many adults aged 27-45 have already been exposed to HPV early in life,” she said. Those in a long-term mutually monogamous relationship are not likely to get a new HPV infection. Those with multiple prior sex partners are more likely to have already been exposed to vaccine serotypes. For them, the vaccine will be less effective.”

Fryhofer added that individuals who are now at risk for exposure to a new HPV infection from a new sex partner are the ones most likely to benefit from HPV vaccination.

Confirmation needed

The FDA’s accelerated approval is contingent on confirmatory data, and Merck opened a clinical trial this past February to evaluate the efficacy, immunogenicity, and safety of the 9-valent HPV vaccine in men 20 to 45 years of age. The phase 3 multicenter randomized trial will have an estimated enrollment of 6000 men.

This article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Three-drug combo promising against high-risk CLL

For patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line therapy with a triple combination of targeted agents showed encouraging response rates in the phase 2 CLL2-GIVe trial.

Among 41 patients with untreated CLL bearing deleterious TP53 mutations and/or the 17p chromosomal deletion who received the GIVe regimen consisting of obinutuzumab (Gazyva), ibrutinib (Imbruvica), and venetoclax (Venclexta), the complete response rate at final restaging was 58.5%, and 33 patients with a confirmed response were negative for minimal residual disease after a median follow-up of 18.6 months, reported Henriette Huber, MD, of University Hospital Ulm, Germany.

“The GIVe regimen is promising first-line therapy for patients with high-risk CLL,” she said in a presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The overall safety profile of the combination was acceptable, she said, but added that “some higher-grade infections are of concern.” The rate of grade 3 or greater infections/infestations in the study was 19.5%.

Sound rationale (with caveat)

Another adverse event of concern is the rate of atrial fibrillation in the comparatively young patient population (median age 62), noted Alexey Danilov, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte Calif., who commented on the study for MDedge.

He pointed out that second-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors such as acalabrutinib (Calquence) may pose a lower risk of atrial fibrillation than the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib used in the CLL2-GIVe study.

In general, however, the rationale for the combination is sound, Dr. Danilov said.

“Of all the patient populations that we deal with within CLL, this probably would be most appropriate for this type of therapy. Patients with deletion 17p or TP53 mutations still represent an unmet medical need compared to other patients who don’t have those mutations,” he said.

Patients with CLL bearing the mutations have lower clinical response rates to novel therapies and generally do not respond well to chemoimmunotherapy, he said.

“The question becomes whether using these all at the same time, versus sequential strategies – using one drug and then after that, at relapse, another – is better, and obviously this trial doesn’t address that,” he said.

Three targets

The investigators enrolled 24 men and 17 women with untreated CLL with del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations and adequate organ function (creatinine clearance rate of more than 50 mL/min). The median age was 62 (range 35-85 years); 78% of patients had Binet stage B or C disease. The median Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score was 3 (range 0 to 8).

All patients received treatment with the combination for 6 months. The CD20 inhibitor obinutuzumab was given in a dose of 1,000 mg on days 1, 8 and 15 of cycle 1 and day 1 of cycles 2-6. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib was given continuously at a dose of 420 mg per day beginning on the first day of the first cycle. Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitor, was started on day 22 of cycle 1, and was increased to 400 mg per day over 5 weeks until the end of cycle 12.

If patients achieved a complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete recovery of blood counts (CRi) according to International Workshop on CLL criteria at final restaging (performed with imaging at the end of cycle 12 followed by bone marrow biopsy 2 months later), ibrutinib would be stopped beginning at cycle 15. Patients who did not have a CR or CRi would continue on ibrutinib until cycle 36.

Encouraging results

All but 3 of the 41 patients reached final restaging. Analyses of efficacy and safety included all 41 patients.

The CR/CRi rate at final restaging, the primary endpoint, was accomplished in 24 patients (58.8%), and 14 patients (34.1%) had a partial response.

Of the three patients for whom responses could not be assessed, two died (one from ovarian cancer which was retrospectively determined to have been present at enrollment, and one at cycle 9 from cardiac failure), and the third patient withdrew consent at cycle 10.

In all, 33 patients (80.5%) were MRD-negative in peripheral blood, 4 remained MRD positive, and 4 were not assessed. Per protocol, 22 patients with undetectable MRD and a CR or CRi discontinued therapy at week 15. An additional 13 patients also discontinued therapy because of adverse events or other reasons, and 6 remained on therapy beyond cycle 15.

The most frequent adverse events of any grade through the end of cycle 14 were gastrointestinal disorders in 83%, none higher than grade 2; infections and infestations in 70.7%, of which 19.5% were grade 3 or greater in severity; and blood and lymphatic system disorders in 58.5%, most of which (53.7%) were grade 3 or greater.

Cardiac disorders were reported in 19.5% of all patients, including 12.2% with atrial fibrillation; grade 3 or greater atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients.

There was one case each of cerebral aspergillosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (without PCR testing), urosepsis, staphylococcal sepsis and febrile infection.

Laboratory confirmed tumor lysis syndrome, all grade 3 or greater, was reported in 9.8% of patients. Infusion-related reactions were reported in 29.3% of patients, with a total of 7.3% being grade 3 or greater.

The trial was supported by Janssen-Cilag and Roche. Dr. Huber disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Dr. Danilov disclosed consulting for AbbVie, Janssen, and Genentech.

SOURCE: Huber H et al. EHA Congress. Abstract S157.

For patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line therapy with a triple combination of targeted agents showed encouraging response rates in the phase 2 CLL2-GIVe trial.

Among 41 patients with untreated CLL bearing deleterious TP53 mutations and/or the 17p chromosomal deletion who received the GIVe regimen consisting of obinutuzumab (Gazyva), ibrutinib (Imbruvica), and venetoclax (Venclexta), the complete response rate at final restaging was 58.5%, and 33 patients with a confirmed response were negative for minimal residual disease after a median follow-up of 18.6 months, reported Henriette Huber, MD, of University Hospital Ulm, Germany.

“The GIVe regimen is promising first-line therapy for patients with high-risk CLL,” she said in a presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The overall safety profile of the combination was acceptable, she said, but added that “some higher-grade infections are of concern.” The rate of grade 3 or greater infections/infestations in the study was 19.5%.

Sound rationale (with caveat)

Another adverse event of concern is the rate of atrial fibrillation in the comparatively young patient population (median age 62), noted Alexey Danilov, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte Calif., who commented on the study for MDedge.

He pointed out that second-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors such as acalabrutinib (Calquence) may pose a lower risk of atrial fibrillation than the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib used in the CLL2-GIVe study.

In general, however, the rationale for the combination is sound, Dr. Danilov said.

“Of all the patient populations that we deal with within CLL, this probably would be most appropriate for this type of therapy. Patients with deletion 17p or TP53 mutations still represent an unmet medical need compared to other patients who don’t have those mutations,” he said.

Patients with CLL bearing the mutations have lower clinical response rates to novel therapies and generally do not respond well to chemoimmunotherapy, he said.

“The question becomes whether using these all at the same time, versus sequential strategies – using one drug and then after that, at relapse, another – is better, and obviously this trial doesn’t address that,” he said.

Three targets

The investigators enrolled 24 men and 17 women with untreated CLL with del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations and adequate organ function (creatinine clearance rate of more than 50 mL/min). The median age was 62 (range 35-85 years); 78% of patients had Binet stage B or C disease. The median Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score was 3 (range 0 to 8).

All patients received treatment with the combination for 6 months. The CD20 inhibitor obinutuzumab was given in a dose of 1,000 mg on days 1, 8 and 15 of cycle 1 and day 1 of cycles 2-6. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib was given continuously at a dose of 420 mg per day beginning on the first day of the first cycle. Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitor, was started on day 22 of cycle 1, and was increased to 400 mg per day over 5 weeks until the end of cycle 12.

If patients achieved a complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete recovery of blood counts (CRi) according to International Workshop on CLL criteria at final restaging (performed with imaging at the end of cycle 12 followed by bone marrow biopsy 2 months later), ibrutinib would be stopped beginning at cycle 15. Patients who did not have a CR or CRi would continue on ibrutinib until cycle 36.

Encouraging results

All but 3 of the 41 patients reached final restaging. Analyses of efficacy and safety included all 41 patients.

The CR/CRi rate at final restaging, the primary endpoint, was accomplished in 24 patients (58.8%), and 14 patients (34.1%) had a partial response.

Of the three patients for whom responses could not be assessed, two died (one from ovarian cancer which was retrospectively determined to have been present at enrollment, and one at cycle 9 from cardiac failure), and the third patient withdrew consent at cycle 10.

In all, 33 patients (80.5%) were MRD-negative in peripheral blood, 4 remained MRD positive, and 4 were not assessed. Per protocol, 22 patients with undetectable MRD and a CR or CRi discontinued therapy at week 15. An additional 13 patients also discontinued therapy because of adverse events or other reasons, and 6 remained on therapy beyond cycle 15.

The most frequent adverse events of any grade through the end of cycle 14 were gastrointestinal disorders in 83%, none higher than grade 2; infections and infestations in 70.7%, of which 19.5% were grade 3 or greater in severity; and blood and lymphatic system disorders in 58.5%, most of which (53.7%) were grade 3 or greater.

Cardiac disorders were reported in 19.5% of all patients, including 12.2% with atrial fibrillation; grade 3 or greater atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients.

There was one case each of cerebral aspergillosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (without PCR testing), urosepsis, staphylococcal sepsis and febrile infection.

Laboratory confirmed tumor lysis syndrome, all grade 3 or greater, was reported in 9.8% of patients. Infusion-related reactions were reported in 29.3% of patients, with a total of 7.3% being grade 3 or greater.

The trial was supported by Janssen-Cilag and Roche. Dr. Huber disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Dr. Danilov disclosed consulting for AbbVie, Janssen, and Genentech.

SOURCE: Huber H et al. EHA Congress. Abstract S157.

For patients with high-risk chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL), first-line therapy with a triple combination of targeted agents showed encouraging response rates in the phase 2 CLL2-GIVe trial.

Among 41 patients with untreated CLL bearing deleterious TP53 mutations and/or the 17p chromosomal deletion who received the GIVe regimen consisting of obinutuzumab (Gazyva), ibrutinib (Imbruvica), and venetoclax (Venclexta), the complete response rate at final restaging was 58.5%, and 33 patients with a confirmed response were negative for minimal residual disease after a median follow-up of 18.6 months, reported Henriette Huber, MD, of University Hospital Ulm, Germany.

“The GIVe regimen is promising first-line therapy for patients with high-risk CLL,” she said in a presentation during the virtual annual congress of the European Hematology Association.

The overall safety profile of the combination was acceptable, she said, but added that “some higher-grade infections are of concern.” The rate of grade 3 or greater infections/infestations in the study was 19.5%.

Sound rationale (with caveat)

Another adverse event of concern is the rate of atrial fibrillation in the comparatively young patient population (median age 62), noted Alexey Danilov, MD, PhD, of City of Hope in Duarte Calif., who commented on the study for MDedge.

He pointed out that second-generation Bruton’s tyrosine kinase (BTK) inhibitors such as acalabrutinib (Calquence) may pose a lower risk of atrial fibrillation than the BTK inhibitor ibrutinib used in the CLL2-GIVe study.

In general, however, the rationale for the combination is sound, Dr. Danilov said.

“Of all the patient populations that we deal with within CLL, this probably would be most appropriate for this type of therapy. Patients with deletion 17p or TP53 mutations still represent an unmet medical need compared to other patients who don’t have those mutations,” he said.

Patients with CLL bearing the mutations have lower clinical response rates to novel therapies and generally do not respond well to chemoimmunotherapy, he said.

“The question becomes whether using these all at the same time, versus sequential strategies – using one drug and then after that, at relapse, another – is better, and obviously this trial doesn’t address that,” he said.

Three targets

The investigators enrolled 24 men and 17 women with untreated CLL with del(17p) and/or TP53 mutations and adequate organ function (creatinine clearance rate of more than 50 mL/min). The median age was 62 (range 35-85 years); 78% of patients had Binet stage B or C disease. The median Cumulative Illness Rating Scale (CIRS) score was 3 (range 0 to 8).

All patients received treatment with the combination for 6 months. The CD20 inhibitor obinutuzumab was given in a dose of 1,000 mg on days 1, 8 and 15 of cycle 1 and day 1 of cycles 2-6. The BTK inhibitor ibrutinib was given continuously at a dose of 420 mg per day beginning on the first day of the first cycle. Venetoclax, a B-cell lymphoma 2 (BCL-2) inhibitor, was started on day 22 of cycle 1, and was increased to 400 mg per day over 5 weeks until the end of cycle 12.

If patients achieved a complete remission (CR) or CR with incomplete recovery of blood counts (CRi) according to International Workshop on CLL criteria at final restaging (performed with imaging at the end of cycle 12 followed by bone marrow biopsy 2 months later), ibrutinib would be stopped beginning at cycle 15. Patients who did not have a CR or CRi would continue on ibrutinib until cycle 36.

Encouraging results

All but 3 of the 41 patients reached final restaging. Analyses of efficacy and safety included all 41 patients.

The CR/CRi rate at final restaging, the primary endpoint, was accomplished in 24 patients (58.8%), and 14 patients (34.1%) had a partial response.

Of the three patients for whom responses could not be assessed, two died (one from ovarian cancer which was retrospectively determined to have been present at enrollment, and one at cycle 9 from cardiac failure), and the third patient withdrew consent at cycle 10.

In all, 33 patients (80.5%) were MRD-negative in peripheral blood, 4 remained MRD positive, and 4 were not assessed. Per protocol, 22 patients with undetectable MRD and a CR or CRi discontinued therapy at week 15. An additional 13 patients also discontinued therapy because of adverse events or other reasons, and 6 remained on therapy beyond cycle 15.

The most frequent adverse events of any grade through the end of cycle 14 were gastrointestinal disorders in 83%, none higher than grade 2; infections and infestations in 70.7%, of which 19.5% were grade 3 or greater in severity; and blood and lymphatic system disorders in 58.5%, most of which (53.7%) were grade 3 or greater.

Cardiac disorders were reported in 19.5% of all patients, including 12.2% with atrial fibrillation; grade 3 or greater atrial fibrillation occurred in 2.4% of patients.

There was one case each of cerebral aspergillosis, progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (without PCR testing), urosepsis, staphylococcal sepsis and febrile infection.

Laboratory confirmed tumor lysis syndrome, all grade 3 or greater, was reported in 9.8% of patients. Infusion-related reactions were reported in 29.3% of patients, with a total of 7.3% being grade 3 or greater.

The trial was supported by Janssen-Cilag and Roche. Dr. Huber disclosed travel reimbursement from Novartis. Dr. Danilov disclosed consulting for AbbVie, Janssen, and Genentech.

SOURCE: Huber H et al. EHA Congress. Abstract S157.

FROM EHA CONGRESS

No OS benefit with gefitinib vs. chemo for EGFR+ NSCLC

The median OS was 75.5 months in patients randomized to adjuvant gefitinib and 62.8 months in patients randomized to vinorelbine plus cisplatin.

Yi-Long Wu, MD, of Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute in Guangzhou, China, reported these results as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

Prior results from this trial had shown a disease-free survival (DFS) benefit with gefitinib, but this did not translate to an OS benefit at the final analysis, Dr. Wu said.

He noted, however, that the median OS of 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm “was one of the best in resected EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer, compared with historical data.”

The findings also suggest a possible benefit with at least 18 months of gefitinib and show that adjuvant EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) should be considered the optimal therapy to improve DFS and achieve potentially better OS in this setting, Dr. Wu said.

Study details and DFS

The ADJUVANT trial (NCT01405079) randomized 222 patients, aged 18-75 years, with EGFR-mutant, stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) NSCLC who had undergone complete resection. Patients were enrolled at 27 sites between September 2011 and April 2014.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 250 mg of gefitinib once daily for 24 months, or 25 mg/m2 of vinorelbine on days 1 and 8 plus 75 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 every 3 weeks for 4 cycles.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included 111 patients in each arm. The per-protocol population included 106 patients in the gefitinib arm and 87 patients in the chemotherapy arm.

Primary results from this trial showed a significant improvement in DFS with gefitinib (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jan;19[1]:139-48). That improvement was maintained in the final analysis.

The median DFS was 30.8 months in the gefitinib arm and 19.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The hazard ratio (HR) was 0.56 (P = .001) in the ITT population and 0.51 (P < .001) in the per-protocol population.

In the ITT population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% in the gefitinib arm and 23.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% and 22.8%, respectively.

OS results

The median OS was 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm and 62.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The HR was 0.92 in both the ITT (P = .674) and per-protocol populations (P = .686).

In the ITT population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% in the gefitinib arm and 51.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% and 50.7%, respectively.

Subgroup analyses by age, gender, lymph node status, and EGFR mutation showed trends toward improved OS with gefitinib, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The researchers conducted a post hoc analysis to assess the effect of subsequent treatment on patient outcomes. The analysis showed that patients who received gefitinib with subsequent EGFR-TKIs had the best responses and OS.

The median OS was not reached among patients who received gefitinib and subsequent EGFR-TKIs, whereas the median OS ranged from 15.6 months to 62.8 months in other groups. The shortest OS was observed in patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy without subsequent therapy.

The duration of gefitinib treatment also appeared to affect OS. The median OS was 35.7 months in patients who received gefitinib for less than 18 months, and the median OS was not reached in patients who received gefitinib for 18 months or longer (HR, 0.38; P < .001).

Implications and potential next steps

Despite the lack of OS improvement with gefitinib, “all of the patients on this study did much, much better than historical non–small cell lung cancer not specified by the EGFR mutation, with 70 months median survival compared to 35 months median survival for N2-positive disease,” said invited discussant Christopher G. Azzoli, MD, director of thoracic oncology at Lifespan Cancer Institute at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

“But you can’t avoid noticing how the curves come back together in terms of disease-free survival when your effective treatment is limited to 24 months,” he added.

An apparent risk of late brain recurrence in the gefitinib arm is also a concern, Dr. Azzoli said. “So ... longer duration of treatment with a drug that has better control of CNS [central nervous system] disease, such as osimertinib, may improve both DFS and OS,” he added.

Only about 50% of patients in the chemotherapy arm received a TKI at recurrence. The post hoc analysis showing that TKI recipients had the best outcomes raises the question of whether “the survival benefit could be conferred by delivering a superior drug merely at recurrence, or is there benefit to earlier delivery of an effective drug,” Dr. Azzoli said.

Given the high cost of continuous therapy, biomarker refinement could help improve treatment decision-making, he said, noting that “early testing of blood DNA to detect cancer in the body as minimal residual disease is showing promise,” and that many phase 3 studies of EGFR-TKIs are ongoing.

The current trial was sponsored by the Guangdong Association of Clinical Trials. Dr. Wu disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/China, Lilly, MSD Oncology, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Azzoli reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wu Y et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 9005.

The median OS was 75.5 months in patients randomized to adjuvant gefitinib and 62.8 months in patients randomized to vinorelbine plus cisplatin.

Yi-Long Wu, MD, of Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute in Guangzhou, China, reported these results as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

Prior results from this trial had shown a disease-free survival (DFS) benefit with gefitinib, but this did not translate to an OS benefit at the final analysis, Dr. Wu said.

He noted, however, that the median OS of 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm “was one of the best in resected EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer, compared with historical data.”

The findings also suggest a possible benefit with at least 18 months of gefitinib and show that adjuvant EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) should be considered the optimal therapy to improve DFS and achieve potentially better OS in this setting, Dr. Wu said.

Study details and DFS

The ADJUVANT trial (NCT01405079) randomized 222 patients, aged 18-75 years, with EGFR-mutant, stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) NSCLC who had undergone complete resection. Patients were enrolled at 27 sites between September 2011 and April 2014.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 250 mg of gefitinib once daily for 24 months, or 25 mg/m2 of vinorelbine on days 1 and 8 plus 75 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 every 3 weeks for 4 cycles.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included 111 patients in each arm. The per-protocol population included 106 patients in the gefitinib arm and 87 patients in the chemotherapy arm.

Primary results from this trial showed a significant improvement in DFS with gefitinib (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jan;19[1]:139-48). That improvement was maintained in the final analysis.

The median DFS was 30.8 months in the gefitinib arm and 19.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The hazard ratio (HR) was 0.56 (P = .001) in the ITT population and 0.51 (P < .001) in the per-protocol population.

In the ITT population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% in the gefitinib arm and 23.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% and 22.8%, respectively.

OS results

The median OS was 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm and 62.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The HR was 0.92 in both the ITT (P = .674) and per-protocol populations (P = .686).

In the ITT population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% in the gefitinib arm and 51.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% and 50.7%, respectively.

Subgroup analyses by age, gender, lymph node status, and EGFR mutation showed trends toward improved OS with gefitinib, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The researchers conducted a post hoc analysis to assess the effect of subsequent treatment on patient outcomes. The analysis showed that patients who received gefitinib with subsequent EGFR-TKIs had the best responses and OS.

The median OS was not reached among patients who received gefitinib and subsequent EGFR-TKIs, whereas the median OS ranged from 15.6 months to 62.8 months in other groups. The shortest OS was observed in patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy without subsequent therapy.

The duration of gefitinib treatment also appeared to affect OS. The median OS was 35.7 months in patients who received gefitinib for less than 18 months, and the median OS was not reached in patients who received gefitinib for 18 months or longer (HR, 0.38; P < .001).

Implications and potential next steps

Despite the lack of OS improvement with gefitinib, “all of the patients on this study did much, much better than historical non–small cell lung cancer not specified by the EGFR mutation, with 70 months median survival compared to 35 months median survival for N2-positive disease,” said invited discussant Christopher G. Azzoli, MD, director of thoracic oncology at Lifespan Cancer Institute at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

“But you can’t avoid noticing how the curves come back together in terms of disease-free survival when your effective treatment is limited to 24 months,” he added.

An apparent risk of late brain recurrence in the gefitinib arm is also a concern, Dr. Azzoli said. “So ... longer duration of treatment with a drug that has better control of CNS [central nervous system] disease, such as osimertinib, may improve both DFS and OS,” he added.

Only about 50% of patients in the chemotherapy arm received a TKI at recurrence. The post hoc analysis showing that TKI recipients had the best outcomes raises the question of whether “the survival benefit could be conferred by delivering a superior drug merely at recurrence, or is there benefit to earlier delivery of an effective drug,” Dr. Azzoli said.

Given the high cost of continuous therapy, biomarker refinement could help improve treatment decision-making, he said, noting that “early testing of blood DNA to detect cancer in the body as minimal residual disease is showing promise,” and that many phase 3 studies of EGFR-TKIs are ongoing.

The current trial was sponsored by the Guangdong Association of Clinical Trials. Dr. Wu disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/China, Lilly, MSD Oncology, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Azzoli reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wu Y et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 9005.

The median OS was 75.5 months in patients randomized to adjuvant gefitinib and 62.8 months in patients randomized to vinorelbine plus cisplatin.

Yi-Long Wu, MD, of Guangdong Lung Cancer Institute in Guangzhou, China, reported these results as part of the American Society of Clinical Oncology virtual scientific program.

Prior results from this trial had shown a disease-free survival (DFS) benefit with gefitinib, but this did not translate to an OS benefit at the final analysis, Dr. Wu said.

He noted, however, that the median OS of 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm “was one of the best in resected EGFR-mutant non–small cell lung cancer, compared with historical data.”

The findings also suggest a possible benefit with at least 18 months of gefitinib and show that adjuvant EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs) should be considered the optimal therapy to improve DFS and achieve potentially better OS in this setting, Dr. Wu said.

Study details and DFS

The ADJUVANT trial (NCT01405079) randomized 222 patients, aged 18-75 years, with EGFR-mutant, stage II-IIIA (N1-N2) NSCLC who had undergone complete resection. Patients were enrolled at 27 sites between September 2011 and April 2014.

The patients were randomized 1:1 to receive 250 mg of gefitinib once daily for 24 months, or 25 mg/m2 of vinorelbine on days 1 and 8 plus 75 mg/m2 of cisplatin on day 1 every 3 weeks for 4 cycles.

The intent-to-treat (ITT) population included 111 patients in each arm. The per-protocol population included 106 patients in the gefitinib arm and 87 patients in the chemotherapy arm.

Primary results from this trial showed a significant improvement in DFS with gefitinib (Lancet Oncol. 2018 Jan;19[1]:139-48). That improvement was maintained in the final analysis.

The median DFS was 30.8 months in the gefitinib arm and 19.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The hazard ratio (HR) was 0.56 (P = .001) in the ITT population and 0.51 (P < .001) in the per-protocol population.

In the ITT population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% in the gefitinib arm and 23.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year DFS rates were 22.6% and 22.8%, respectively.

OS results

The median OS was 75.5 months in the gefitinib arm and 62.8 months in the chemotherapy arm for both the ITT and per-protocol populations. The HR was 0.92 in both the ITT (P = .674) and per-protocol populations (P = .686).

In the ITT population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% in the gefitinib arm and 51.2% in the chemotherapy arm. In the per-protocol population, the 5-year OS rates were 53.2% and 50.7%, respectively.

Subgroup analyses by age, gender, lymph node status, and EGFR mutation showed trends toward improved OS with gefitinib, but the differences were not statistically significant.

The researchers conducted a post hoc analysis to assess the effect of subsequent treatment on patient outcomes. The analysis showed that patients who received gefitinib with subsequent EGFR-TKIs had the best responses and OS.

The median OS was not reached among patients who received gefitinib and subsequent EGFR-TKIs, whereas the median OS ranged from 15.6 months to 62.8 months in other groups. The shortest OS was observed in patients who received adjuvant chemotherapy without subsequent therapy.

The duration of gefitinib treatment also appeared to affect OS. The median OS was 35.7 months in patients who received gefitinib for less than 18 months, and the median OS was not reached in patients who received gefitinib for 18 months or longer (HR, 0.38; P < .001).

Implications and potential next steps

Despite the lack of OS improvement with gefitinib, “all of the patients on this study did much, much better than historical non–small cell lung cancer not specified by the EGFR mutation, with 70 months median survival compared to 35 months median survival for N2-positive disease,” said invited discussant Christopher G. Azzoli, MD, director of thoracic oncology at Lifespan Cancer Institute at Brown University in Providence, R.I.

“But you can’t avoid noticing how the curves come back together in terms of disease-free survival when your effective treatment is limited to 24 months,” he added.

An apparent risk of late brain recurrence in the gefitinib arm is also a concern, Dr. Azzoli said. “So ... longer duration of treatment with a drug that has better control of CNS [central nervous system] disease, such as osimertinib, may improve both DFS and OS,” he added.

Only about 50% of patients in the chemotherapy arm received a TKI at recurrence. The post hoc analysis showing that TKI recipients had the best outcomes raises the question of whether “the survival benefit could be conferred by delivering a superior drug merely at recurrence, or is there benefit to earlier delivery of an effective drug,” Dr. Azzoli said.

Given the high cost of continuous therapy, biomarker refinement could help improve treatment decision-making, he said, noting that “early testing of blood DNA to detect cancer in the body as minimal residual disease is showing promise,” and that many phase 3 studies of EGFR-TKIs are ongoing.

The current trial was sponsored by the Guangdong Association of Clinical Trials. Dr. Wu disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb/China, Lilly, MSD Oncology, Pfizer, and Roche. Dr. Azzoli reported having no disclosures.

SOURCE: Wu Y et al. ASCO 2020, Abstract 9005.

FROM ASCO 2020

Pulmonary Neuroendocrine Tumor Presenting as a Left Pleural Effusion

Neuroendocrine tumors (NETs) account for about 0.5% of all newly diagnosed malignancies.1 Pulmonary NETs are rare, accounting for 1 to 2% of all invasive lung malignancies and involve about 20 to 25% of primary lung malignancies. 2,3 Their prevalence has increased by an estimated 6% per year over the past 30 years.2 Nonetheless, the time of diagnosis is frequently delayed because of nonspecific symptoms that may imitate other pulmonary conditions.

In the normal pleural space, there is a steady state in which there is a roughly equal rate of fluid formation and absorption. Any disequilibrium may produce a pleural effusion. Pleural fluids can be transudates or exudates. Transudates result from imbalances in hydrostatic and oncotic pressures in the pleural space. Exudates result primarily from pleural and/or lung inflammation or from impaired lymphatic drainage of the pleural space. Clinical manifestations include cough, wheezing, recurrent pneumonia, hemoptysis and pleural effusions. We present a case of a man who developed a large left pleural effusion with a pathology report suggesting a pulmonary NET as the etiology. Being aware of this rare entity may help improve prognosis by making an earlier diagnosis and starting treatment sooner.

Case Presentation

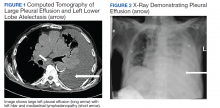

A 90-year-old man with a medical history of arterial hypertension, hyperlipidemia, type 2 diabetes mellitus, coronary artery disease, and vascular dementia presented to the emergency department with hypoactivity, poor appetite, productive cough, and shortness of breath. The patient was a former smoker (unknown pack-years) who quit smoking cigarettes 7 years prior. Vital signs showed sinus tachycardia and peripheral oxygen saturation of 90% at room air. The initial physical examination was remarkable for decreased breath sounds and crackles at the left lung base. Laboratory findings showed leukocytosis with neutrophilia and chronic normocytic anemia. Chest computed tomography (CT) showed a large left-sided pleural effusion occupying most of the left hemithorax with adjacent atelectatic lung, enlarged pretracheal, subcarinal, and left perihilar lymph nodes (Figure 1).

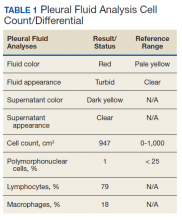

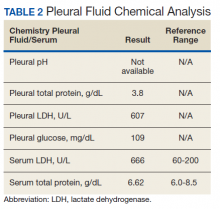

The patient was admitted to the internal medicine ward with the diagnosis of left pneumonic process and started on IV levofloxacin. However, despite 7 days of antibiotic therapy, the patient’s respiratory symptoms worsened. This clinical deterioration prompted pulmonary service consultation. Chest radiography demonstrated an enlarging left pleural effusion (Figure 2). A thoracentesis drained 1.2 L of serosanguineous pleural fluid. Pleural fluid analysis showed a cell count of 947/cm3 with 79% of lymphocytes, total protein 3.8 g/dL, lactic dehydrogenase (LDH) level 607 U/L, and glucose level 109 mg/dL. Serum total protein was 6.62 g/dL, LDH 666 U/L and glucose 92 mg/dL (Tables 1 and 2). Alanine transaminase (ALT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST) were 11 U/L and 21 U/L, respectively. Using Light criteria, the pleural:serum protein ratio was 0.57, the pleural:serum LDH ratio was 0.91, and the pleural LDH was more than two-thirds of the serum LDH. These calculations were consistent with an exudative effusion. An infectious disease workup, including blood and pleural fluid cultures, was negative.

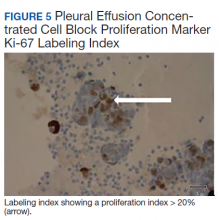

The pleural fluid concentrated cell block hematoxylin and eosin (H&E) staining showed chromatin, prominent nucleoli, and nuclear molding, which was compatible with high-grade lung NET (Figure 3). The cell block immunohistochemistry (IHC) was positive for synaptophysin, chromogranin A, and neuron specific enolase (NSE) also consistent with a high-grade pulmonary NET (Figure 4). The proliferation marker protein Ki-67 labeling index (LI) showed a proliferation index > 20% (Figure 5). The patient did not have decision-making capacity given vascular dementia. Multiple attempts to contact the next of kin or family members were unsuccessful. Risks vs benefits were evaluated, and given the patient’s advanced age and multiple comorbidities, a conservative management approach under palliative care was chosen. For this reason, further genomic studies were not done.

Discussion

NETs are a group of neoplasms that differ in site, amount of cell propagation, and clinical manifestations.4 These tumors are rare with an estimated incidence of 25 to 50 per 100,000.4 The most commonly affected organ systems are the gastroenteropancreatic and the bronchopulmonary tracts, accounting for 60% and 25% of the tumors, respectively.4 The incidence is increasing over the past years in part because of novel diagnostic techniques.

The average age of diagnosis is between the fourth and sixth decades, affecting more women than men.5 Smoking has been identified as a possible culprit for the development of these neoplasms; nonetheless, the association is still not clear.4 For example, poorly differentiated pulmonary NETs have a strong association with smoking but not well-differentiated pulmonary NETs.2

Patients typically present with cough, wheezing, hemoptysis, and recurrent pneumonias, which are in part a consequence of obstruction caused by the mass.2 Sometimes, obstruction may yield persistent pleural effusions. Hemoptysis may be seen secondary to the vascularity of pulmonary NETs.

The diagnosis is often delayed because patients are frequently treated for infection before being diagnosed with the malignancy, such as in our case. Radiologic image findings include round opacities, central masses, and atelectasis. Pulmonary NETs are frequently found incidentally as solitary lung nodules. The CT scan is the most common diagnostic modality and can provide information about the borders of the tumor, the location and surrounding structures, including the presence of atelectasis.5 Pulmonary NETs are usually centrally located in an accessible region for lung biopsy. In cases where the mass is not easily reachable, thoracentesis may provide the only available specimen.

The 2015 World Health Organization classification has identified 4 histologic types of pulmonary NETs, namely, typical carcinoid (TC), atypical carcinoid (AC), large cell neuroendocrine carcinoma (LCNEC) and small cell lung carcinoma (SCLC).6 The low-grade pulmonary NET, the typical carcinoid, is slow growing and has lower rates of metastasis. The intermediate-grade NET, the atypical carcinoid, is more aggressive. The highgrade NETs, the LCNEC and the SCLC, are aggressive and spread quickly to other places.6 Consequently, LCNEC and SCLC have higher mortalities with a 5-year survival, ranging from 13 to 57% and 5%, respectively.7

Tumors may be histomorphologically classified by H&E staining. The main characteristics that differentiate the low- and high-grade NETs are the presence of necrosis and the mitotic rate. Both categories form neuropeptides and have dense granular cores when seen with an electron microscopy.6 The TC and AC have welldefined, organized histologic patterns, no necrosis, and scarce mitosis. On the other hand, the LCNEC and SCLC are poorly differentiated tumors with necrosis, atypia, and mitosis.6 LCNEC can be separated from SCLC and other tumors by IHC staining, whereas SCLC is primarily distinguished by morphology.

If the biopsy sample size is small, then IHC morphology and markers are helpful for subclassification.8 IHC is used to discern between neuroendocrine (NE) vs non-NE. The evaluation of pleural fluid includes preparation of cell blocks. Cell block staining is deemed better for IHC because it mimics a small biopsy that enables superior stains.9 The need for a pleural biopsy in cases where the cytology is negative depends on treatment aims, the kind of tumor, and the presence of metastasis.10 In almost 80% of cases, pleural biopsy and cytology are the only specimens obtained for analysis.Therefore, identification of these markers is practical for diagnosis.10 For this reason, pleural effusion samples are appropriate options to lung biopsy for molecular studies.10

Ki-67 LI in samples has the highest specificity and sensitivity for low-tointermediate- grade vs high-grade tumors. It is being used for guiding clinical and treatment decisions.6 In SCLC, the Ki-67 LI is not necessary for diagnosis but will be about 80%.11 The tumor cells will show epithelial characteristics with positive cytokeratin AE1/AE3 and monoclonal antibody CAM5.2 and neuroendocrine markers, including NCAM/CD56, chromogranin A, and synaptophysin.11