User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Class I recall issued for intracranial pressure monitor

Integra is recalling the CereLink Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitor after reports that the device may display incorrect ICP values and out-of-range pressure readings.

The recall includes 388 monitors, with model numbers 826820 and 826820P. The devices were distributed between June 1, 2021 and May 31, 2022.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a class I recall, the most serious type, because of the risk for serious injury or death.

The monitor is used in patients with head injuries and stroke as well as in surgical and postoperative neurosurgical patients and those with other conditions.

The device’s sensor is implanted in the brain and connected by a wire to an external monitor that displays ICP readings, which are used to both monitor and guide treatment.

If the CereLink ICP Monitor fails to function properly, the patient may have to undergo additional brain surgeries to replace it, which involves the risks for infection, bleeding, and damage to tissue. A malfunctioning device also creates a risk for serious injury or death, the MedWatch notes.

Global complaints

As of July 31, Integra has received 105 global complaints associated with this recall.

In addition,

According to the FDA, the patient death report in the MDR described a malfunctioning CereLink ICP Monitor during use in a critically injured patient, which was mitigated by replacing the ICP sensor.

“The cause of patient death was determined by Integra to be unrelated to the CereLink ICP Monitor malfunction,” the FDA said.

The manufacturer has sent a letter to customers advising them to stop using the recalled monitors “as soon as clinically possible.”

The letter states that continued use of a monitor already in place should be determined only by an individualized risk-benefit analysis by the attending clinician.

For any new patients, the company advises switching to an alternate patient-monitoring system.

Customers with questions or concerns about this recall should contact their Integra account manager, clinical specialist, or customer service by phone at 800-654-2873 or by email at [email protected].

Problems related to the CereLink ICP Monitor should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Integra is recalling the CereLink Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitor after reports that the device may display incorrect ICP values and out-of-range pressure readings.

The recall includes 388 monitors, with model numbers 826820 and 826820P. The devices were distributed between June 1, 2021 and May 31, 2022.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a class I recall, the most serious type, because of the risk for serious injury or death.

The monitor is used in patients with head injuries and stroke as well as in surgical and postoperative neurosurgical patients and those with other conditions.

The device’s sensor is implanted in the brain and connected by a wire to an external monitor that displays ICP readings, which are used to both monitor and guide treatment.

If the CereLink ICP Monitor fails to function properly, the patient may have to undergo additional brain surgeries to replace it, which involves the risks for infection, bleeding, and damage to tissue. A malfunctioning device also creates a risk for serious injury or death, the MedWatch notes.

Global complaints

As of July 31, Integra has received 105 global complaints associated with this recall.

In addition,

According to the FDA, the patient death report in the MDR described a malfunctioning CereLink ICP Monitor during use in a critically injured patient, which was mitigated by replacing the ICP sensor.

“The cause of patient death was determined by Integra to be unrelated to the CereLink ICP Monitor malfunction,” the FDA said.

The manufacturer has sent a letter to customers advising them to stop using the recalled monitors “as soon as clinically possible.”

The letter states that continued use of a monitor already in place should be determined only by an individualized risk-benefit analysis by the attending clinician.

For any new patients, the company advises switching to an alternate patient-monitoring system.

Customers with questions or concerns about this recall should contact their Integra account manager, clinical specialist, or customer service by phone at 800-654-2873 or by email at [email protected].

Problems related to the CereLink ICP Monitor should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Integra is recalling the CereLink Intracranial Pressure (ICP) Monitor after reports that the device may display incorrect ICP values and out-of-range pressure readings.

The recall includes 388 monitors, with model numbers 826820 and 826820P. The devices were distributed between June 1, 2021 and May 31, 2022.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration has identified this as a class I recall, the most serious type, because of the risk for serious injury or death.

The monitor is used in patients with head injuries and stroke as well as in surgical and postoperative neurosurgical patients and those with other conditions.

The device’s sensor is implanted in the brain and connected by a wire to an external monitor that displays ICP readings, which are used to both monitor and guide treatment.

If the CereLink ICP Monitor fails to function properly, the patient may have to undergo additional brain surgeries to replace it, which involves the risks for infection, bleeding, and damage to tissue. A malfunctioning device also creates a risk for serious injury or death, the MedWatch notes.

Global complaints

As of July 31, Integra has received 105 global complaints associated with this recall.

In addition,

According to the FDA, the patient death report in the MDR described a malfunctioning CereLink ICP Monitor during use in a critically injured patient, which was mitigated by replacing the ICP sensor.

“The cause of patient death was determined by Integra to be unrelated to the CereLink ICP Monitor malfunction,” the FDA said.

The manufacturer has sent a letter to customers advising them to stop using the recalled monitors “as soon as clinically possible.”

The letter states that continued use of a monitor already in place should be determined only by an individualized risk-benefit analysis by the attending clinician.

For any new patients, the company advises switching to an alternate patient-monitoring system.

Customers with questions or concerns about this recall should contact their Integra account manager, clinical specialist, or customer service by phone at 800-654-2873 or by email at [email protected].

Problems related to the CereLink ICP Monitor should be reported to the FDA’s MedWatch program.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Real medical news: Many teens trust fake medical news

The kids aren’t alright (at identifying fake news online)

If there’s one thing today’s teenagers are good at, it’s the Internet. What with their TokTiks, Fortnights, and memes whose lifespans are measured in milliseconds, it’s only natural that a contingent of people who have never known a world where the Internet wasn’t omnipresent would be highly skilled at navigating the dense, labyrinthine virtual world and the many falsehoods contained within.

Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve been duped, bamboozled, and smeckledorfed. New research from Slovakia suggests the opposite, in fact: Teenagers are just as bad as the rest of us, if not worse, at distinguishing between fake and real online health messaging.

For the study, 300 teenagers aged 16-19 years old were shown a group of messages about the health-promoting effects of fruits and vegetables; these messages were either false, true and neutral, or true with some sort of editing (a clickbait title or grammar mistakes) to mask their trustworthiness. Just under half of the subjects identified and trusted the true neutral messages over fake messages, while 41% couldn’t tell the difference and 11% trusted the fake messages more. In addition, they couldn’t tell the difference between fake and true messages when the content seemed plausible.

In a bit of good news, teenagers were just as likely to trust the edited true messages as the true neutral ones, except in instances when the edited message had a clickbait title. They were much less likely to trust those.

Based on their subjects’ rather poor performance, the study authors suggested teenagers go through health literacy and media literacy training, as well as develop their analytical and scientific reasoning. The LOTME staff rather suspects the study authors have never met a teenager. The only thing teenagers are going to get out of health literacy training is fodder for memes to put up on Myspace. Myspace is still a thing, right? We’re not old, we swear.

Can a computer help deliver babies?

Delivering babies can be a complicated business. Most doctors and midwives rely on their years of experience and training to make certain decisions for mothers in labor, but an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm could make the entire process easier and safer.

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic recently reported that using an AI to analyze women’s labor patterns was very successful in determining whether a vaginal or cesarean delivery was appropriate.

They examined over 700 factors and over 66,000 deliveries from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s multicenter Consortium on Safe Labor database to produce a risk-prediction model that may “provide an alternative to conventional labor charts and promote individualization of clinical decisions using baseline and labor characteristics of each patient,” they said in a written statement from the clinic.

It is hoped that the AI will reduce the risk of possible complications and the costs associated with maternal mortality. The AI also could be a significant tool for doctors and midwives in rural areas to determine when a patient needs to be moved to a location with a higher level of care.

“We believe the algorithm will work in real time, meaning every input of new data during an expectant woman’s labor automatically recalculates the risk of adverse outcome,” said senior author Abimbola Famuyide, MD, of the Mayo Clinic.

If it all works out, many lives and dollars could be saved, thanks to science.

Democracy, meet COVID-19

Everywhere you look, it seems, someone is trying to keep someone else from doing something: Don’t carry a gun. Don’t get an abortion. Don’t drive so fast. Don’t inhale that whipped cream. Don’t get a vaccine. Don’t put that in your mouth.

One of the biggies these days is voting rights. Some people are trying to prevent other people from voting. But why? Well, turns out that turnout can be bad for your health … at least during a worldwide pandemic event.

The evidence for that claim comes from researchers who examined the Italian national constitutional referendum conducted in September 2020 along with elections for assembly representatives in 7 of the country’s 20 regions and for mayors in about 12% of municipalities. The combination mattered: Voter turnout was higher in the municipalities that voted for both the referendum and local elections (69%), compared with municipalities voting only for the referendum (47%), the investigators reported in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

Also occurring in September of 2020 was, as we mentioned, a worldwide pandemic event. You may have heard about it.

The investigators considered the differences in election turnout between the various municipalities and compared them with new weekly COVID-19 infections at the municipality level. “Our model shows that something as fundamental as casting a vote can come at a cost,” investigator Giuseppe Moscelli, PhD, of the University of Surrey (England) said in a written statement.

What was the cost? Each 1% increase in turnout, they found, amounted to an average 1.1% increase in COVID infections after the elections.

See? More people voting means more COVID, which is bad. Which brings us to today’s lesson in people preventing other people from doing something. Don’t let COVID win. Stay in your house and never come out. And get that smeckledorf out of your mouth. You don’t know where it’s been.

The kids aren’t alright (at identifying fake news online)

If there’s one thing today’s teenagers are good at, it’s the Internet. What with their TokTiks, Fortnights, and memes whose lifespans are measured in milliseconds, it’s only natural that a contingent of people who have never known a world where the Internet wasn’t omnipresent would be highly skilled at navigating the dense, labyrinthine virtual world and the many falsehoods contained within.

Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve been duped, bamboozled, and smeckledorfed. New research from Slovakia suggests the opposite, in fact: Teenagers are just as bad as the rest of us, if not worse, at distinguishing between fake and real online health messaging.

For the study, 300 teenagers aged 16-19 years old were shown a group of messages about the health-promoting effects of fruits and vegetables; these messages were either false, true and neutral, or true with some sort of editing (a clickbait title or grammar mistakes) to mask their trustworthiness. Just under half of the subjects identified and trusted the true neutral messages over fake messages, while 41% couldn’t tell the difference and 11% trusted the fake messages more. In addition, they couldn’t tell the difference between fake and true messages when the content seemed plausible.

In a bit of good news, teenagers were just as likely to trust the edited true messages as the true neutral ones, except in instances when the edited message had a clickbait title. They were much less likely to trust those.

Based on their subjects’ rather poor performance, the study authors suggested teenagers go through health literacy and media literacy training, as well as develop their analytical and scientific reasoning. The LOTME staff rather suspects the study authors have never met a teenager. The only thing teenagers are going to get out of health literacy training is fodder for memes to put up on Myspace. Myspace is still a thing, right? We’re not old, we swear.

Can a computer help deliver babies?

Delivering babies can be a complicated business. Most doctors and midwives rely on their years of experience and training to make certain decisions for mothers in labor, but an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm could make the entire process easier and safer.

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic recently reported that using an AI to analyze women’s labor patterns was very successful in determining whether a vaginal or cesarean delivery was appropriate.

They examined over 700 factors and over 66,000 deliveries from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s multicenter Consortium on Safe Labor database to produce a risk-prediction model that may “provide an alternative to conventional labor charts and promote individualization of clinical decisions using baseline and labor characteristics of each patient,” they said in a written statement from the clinic.

It is hoped that the AI will reduce the risk of possible complications and the costs associated with maternal mortality. The AI also could be a significant tool for doctors and midwives in rural areas to determine when a patient needs to be moved to a location with a higher level of care.

“We believe the algorithm will work in real time, meaning every input of new data during an expectant woman’s labor automatically recalculates the risk of adverse outcome,” said senior author Abimbola Famuyide, MD, of the Mayo Clinic.

If it all works out, many lives and dollars could be saved, thanks to science.

Democracy, meet COVID-19

Everywhere you look, it seems, someone is trying to keep someone else from doing something: Don’t carry a gun. Don’t get an abortion. Don’t drive so fast. Don’t inhale that whipped cream. Don’t get a vaccine. Don’t put that in your mouth.

One of the biggies these days is voting rights. Some people are trying to prevent other people from voting. But why? Well, turns out that turnout can be bad for your health … at least during a worldwide pandemic event.

The evidence for that claim comes from researchers who examined the Italian national constitutional referendum conducted in September 2020 along with elections for assembly representatives in 7 of the country’s 20 regions and for mayors in about 12% of municipalities. The combination mattered: Voter turnout was higher in the municipalities that voted for both the referendum and local elections (69%), compared with municipalities voting only for the referendum (47%), the investigators reported in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

Also occurring in September of 2020 was, as we mentioned, a worldwide pandemic event. You may have heard about it.

The investigators considered the differences in election turnout between the various municipalities and compared them with new weekly COVID-19 infections at the municipality level. “Our model shows that something as fundamental as casting a vote can come at a cost,” investigator Giuseppe Moscelli, PhD, of the University of Surrey (England) said in a written statement.

What was the cost? Each 1% increase in turnout, they found, amounted to an average 1.1% increase in COVID infections after the elections.

See? More people voting means more COVID, which is bad. Which brings us to today’s lesson in people preventing other people from doing something. Don’t let COVID win. Stay in your house and never come out. And get that smeckledorf out of your mouth. You don’t know where it’s been.

The kids aren’t alright (at identifying fake news online)

If there’s one thing today’s teenagers are good at, it’s the Internet. What with their TokTiks, Fortnights, and memes whose lifespans are measured in milliseconds, it’s only natural that a contingent of people who have never known a world where the Internet wasn’t omnipresent would be highly skilled at navigating the dense, labyrinthine virtual world and the many falsehoods contained within.

Ladies and gentlemen, we’ve been duped, bamboozled, and smeckledorfed. New research from Slovakia suggests the opposite, in fact: Teenagers are just as bad as the rest of us, if not worse, at distinguishing between fake and real online health messaging.

For the study, 300 teenagers aged 16-19 years old were shown a group of messages about the health-promoting effects of fruits and vegetables; these messages were either false, true and neutral, or true with some sort of editing (a clickbait title or grammar mistakes) to mask their trustworthiness. Just under half of the subjects identified and trusted the true neutral messages over fake messages, while 41% couldn’t tell the difference and 11% trusted the fake messages more. In addition, they couldn’t tell the difference between fake and true messages when the content seemed plausible.

In a bit of good news, teenagers were just as likely to trust the edited true messages as the true neutral ones, except in instances when the edited message had a clickbait title. They were much less likely to trust those.

Based on their subjects’ rather poor performance, the study authors suggested teenagers go through health literacy and media literacy training, as well as develop their analytical and scientific reasoning. The LOTME staff rather suspects the study authors have never met a teenager. The only thing teenagers are going to get out of health literacy training is fodder for memes to put up on Myspace. Myspace is still a thing, right? We’re not old, we swear.

Can a computer help deliver babies?

Delivering babies can be a complicated business. Most doctors and midwives rely on their years of experience and training to make certain decisions for mothers in labor, but an artificial intelligence (AI) algorithm could make the entire process easier and safer.

Researchers from the Mayo Clinic recently reported that using an AI to analyze women’s labor patterns was very successful in determining whether a vaginal or cesarean delivery was appropriate.

They examined over 700 factors and over 66,000 deliveries from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development’s multicenter Consortium on Safe Labor database to produce a risk-prediction model that may “provide an alternative to conventional labor charts and promote individualization of clinical decisions using baseline and labor characteristics of each patient,” they said in a written statement from the clinic.

It is hoped that the AI will reduce the risk of possible complications and the costs associated with maternal mortality. The AI also could be a significant tool for doctors and midwives in rural areas to determine when a patient needs to be moved to a location with a higher level of care.

“We believe the algorithm will work in real time, meaning every input of new data during an expectant woman’s labor automatically recalculates the risk of adverse outcome,” said senior author Abimbola Famuyide, MD, of the Mayo Clinic.

If it all works out, many lives and dollars could be saved, thanks to science.

Democracy, meet COVID-19

Everywhere you look, it seems, someone is trying to keep someone else from doing something: Don’t carry a gun. Don’t get an abortion. Don’t drive so fast. Don’t inhale that whipped cream. Don’t get a vaccine. Don’t put that in your mouth.

One of the biggies these days is voting rights. Some people are trying to prevent other people from voting. But why? Well, turns out that turnout can be bad for your health … at least during a worldwide pandemic event.

The evidence for that claim comes from researchers who examined the Italian national constitutional referendum conducted in September 2020 along with elections for assembly representatives in 7 of the country’s 20 regions and for mayors in about 12% of municipalities. The combination mattered: Voter turnout was higher in the municipalities that voted for both the referendum and local elections (69%), compared with municipalities voting only for the referendum (47%), the investigators reported in the Journal of Economic Behavior & Organization.

Also occurring in September of 2020 was, as we mentioned, a worldwide pandemic event. You may have heard about it.

The investigators considered the differences in election turnout between the various municipalities and compared them with new weekly COVID-19 infections at the municipality level. “Our model shows that something as fundamental as casting a vote can come at a cost,” investigator Giuseppe Moscelli, PhD, of the University of Surrey (England) said in a written statement.

What was the cost? Each 1% increase in turnout, they found, amounted to an average 1.1% increase in COVID infections after the elections.

See? More people voting means more COVID, which is bad. Which brings us to today’s lesson in people preventing other people from doing something. Don’t let COVID win. Stay in your house and never come out. And get that smeckledorf out of your mouth. You don’t know where it’s been.

Many young kids with COVID may show no symptoms

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

BY WILL PASS

Just 14% of adults who tested positive for SARS-CoV-2 were asymptomatic, versus 37% of children aged 0-4 years, in the paper. This raises concern that parents, childcare providers, and preschools may be underestimating infection in seemingly healthy young kids who have been exposed to COVID, wrote lead author Ruth A. Karron, MD, and colleagues in JAMA Network Open.

Methods

The new research involved 690 individuals from 175 households in Maryland who were monitored closely between November 2020 and October 2021. Every week for 8 months, participants completed online symptom checks and underwent PCR testing using nasal swabs, with symptomatic individuals submitting additional swabs for analysis.

“What was different about our study [compared with previous studies] was the intensity of our collection, and the fact that we collected specimens from asymptomatic people,” said Dr. Karron, a pediatrician and professor in the department of international health, Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, in an interview. “You shed more virus earlier in the infection than later, and the fact that we were sampling every single week meant that we could pick up those early infections.”

The study also stands out for its focus on young children, Dr. Karron said. Enrollment required all households to have at least one child aged 0-4 years, so 256 out of 690 participants (37.1%) were in this youngest age group. The remainder of the population consisted of 100 older children aged 5-17 years (14.5%) and 334 adults aged 18-74 years (48.4%).

Children 4 and under more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic

By the end of the study, 51 participants had tested positive for SARS-CoV-2, among whom 14 had no symptoms. A closer look showed that children 0-4 years of age who contracted COVID were more than twice as likely to be asymptomatic as infected adults (36.8% vs. 14.3%).

The relationship between symptoms and viral load also differed between adults and young children.

While adults with high viral loads – suggesting greater contagiousness – typically had more severe COVID symptoms, no correlation was found in young kids, meaning children with mild or no symptoms could still be highly contagious.

Dr. Karron said these findings should help parents and other stakeholders make better-informed decisions based on known risks. She recommended testing young, asymptomatic children for COVID if they have been exposed to infected individuals, then acting accordingly based on the results.

“If a family is infected with the virus, and the 2-year-old is asymptomatic, and people are thinking about a visit to elderly grandparents who may be frail, one shouldn’t assume that the 2-year-old is uninfected,” Dr. Karron said. “That child should be tested along with other family members.”

Testing should also be considered for young children exposed to COVID at childcare facilities, she added.

But not every expert consulted for this piece shared these opinions of Dr. Karron.

“I question whether that effort is worth it,” said Dean Blumberg, MD, professor and chief of the division of pediatric infectious diseases at UC Davis Health, Sacramento, Calif.

He noted that recent Food and Drug Administration guidance for COVID testing calls for three negative at-home antigen tests to confirm lack of infection.

“That would take 4 days to get those tests done,” he said. “So, it’s a lot of testing. It’s a lot of record keeping, it’s inconvenient, it’s uncomfortable to be tested, and I just question whether it’s worth that effort.”

Applicability of findings to today questioned

Dr. Blumberg also questioned whether the study, which was completed almost a year ago, reflects the current pandemic landscape.

“At the time this study was done, it was predominantly Delta [variant instead of Omicron],” Dr. Blumberg said. “The other issue [with the study] is that … most of the children didn’t have preexisting immunity, so you have to take that into account.”

Preexisting immunity – whether from exposure or vaccination – could lower viral loads, so asymptomatic children today really could be less contagious than they were when the study was done, according to Dr. Blumberg. Kids without symptoms are also less likely to spread the virus, because they aren’t coughing or sneezing, he added.

Sara R. Kim, MD, and Janet A. Englund, MD, of the Seattle Children’s Research Institute, University of Washington, said it’s challenging to know how applicable the findings are, although they sided more with the investigators than Dr. Blumberg.

“Given the higher rate of transmissibility and infectivity of the Omicron variant, it is difficult to make direct associations between findings reported during this study period and those present in the current era during which the Omicron variant is circulating,” they wrote in an accompanying editorial. “However, the higher rates of asymptomatic infection observed among children in this study are likely to be consistent with those observed for current and future viral variants.”

Although the experts offered different interpretations of the findings, they shared similar perspectives on vaccination.

“The most important thing that parents can do is get their kids vaccinated, be vaccinated themselves, and have everybody in the household vaccinated and up to date for all doses that are indicated,” Dr. Blumberg said.

Dr. Karron noted that vaccination will be increasingly important in the coming months.

“Summer is ending; school is starting,” she said. “We’re going to be in large groups indoors again very soon. To keep young children safe, I think it’s really important for them to get vaccinated.”

The study was funded by the CDC. The investigators disclosed no other relationships. Dr. Englund disclosed relationships with AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, and others. Dr. Kim and Dr. Blumberg disclosed no relevant conflicts of interest.

FROM JAMA NETWORK OPEN

FDA authorizes updated COVID boosters to target newest variants

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

The agency cited data to support the safety and efficacy of this next generation of mRNA vaccines targeted toward variants of concern.

The Pfizer EUA corresponds to the company’s combination booster shot that includes the original COVID-19 vaccine as well as a vaccine specifically designed to protect against the most recent Omicron variants, BA.4 and BA.5.

The Moderna combination vaccine will contain both the firm’s original COVID-19 vaccine and a vaccine to protect specifically against Omicron BA.4 and BA.5 subvariants.

As of Aug. 27, BA.4 and BA.4.6 account for about 11% of circulating variants and BA.5 accounts for almost all the remaining 89%, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention data show.

The next step will be review of the scientific data by the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices, which is set to meet Sept. 1 and 2. The final hurdle before distribution of the new vaccines will be sign-off on CDC recommendations for use by agency Director Rochelle Walensky, MD.

This is a developing story. A version of this article first appeared on WebMD.com.

Omega-3 fatty acids and depression: Are they protective?

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

New research is suggesting that there are “meaningful” associations between higher dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids and lower risk for depressive episodes.

In addition, consumption of total fatty acids and alpha-linolenic acid was associated with a reduced risk for incident depressive episodes (9% and 29%, respectively).

“Our results showed an important protective effect from the consumption of omega-3,” Maria de Jesus Mendes da Fonseca, University of the State of Rio de Janeiro, and colleagues write.

The findings were published online in Nutrients.

Mixed bag of studies

Epidemiologic evidence suggests that deficient dietary omega-3 intake is a modifiable risk factor for depression and that individuals with low consumption of omega-3 food sources have more depressive symptoms.

However, the results are inconsistent, and few longitudinal studies have addressed this association, the investigators note.

The new analysis included 13,879 adults (aged 39-65 years or older) participating in the Brazilian Longitudinal Study of Adult Health (ELSA-Brasil) from 2008 to 2014.

Data on depressive episodes were obtained with the Clinical Interview Schedule Revised (CIS-R), and food consumption was measured with the Food Frequency Questionnaire (FFQ).

The target dietary components were total polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFA) and the omega-3 fatty acids: alpha-linolenic acid, eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA), and docosapentaenoic acid (DPA).

The majority of participants had adequate dietary intake of omega-3 fatty acids, and none was taking omega-3 supplements.

In the fully adjusted model, consumption of fatty acids from the omega-3 family had a protective effect against maintenance of depressive episodes, showing “important associations, although the significance levels are borderline, possibly due to the sample size,” the researchers report.

In regard to onset of depressive episodes, estimates from the fully adjusted model suggest that a higher consumption of omega-3 acids (total and subtypes) is associated with lower risk for depressive episodes – with significant associations for omega-3 and alpha-linolenic acid.

The investigators note that strengths of the study include “its originality, as it is the first to assess associations between maintenance and incidence of depressive episodes and consumption of omega-3, besides the use of data from the ELSA-Brasil Study, with rigorous data collection protocols and reliable and validated instruments, thus guaranteeing the quality of the sample and the data.”

A study limitation, however, was that the ELSA-Brasil sample consists only of public employees, with the potential for a selection bias such as healthy worker phenomenon, the researchers note. Another was the use of the FFQ, which may underestimate daily intake of foods and depends on individual participant recall – all of which could possibly lead to a differential classification bias.

Interpret cautiously

Commenting on the study, David Mischoulon, MD, PhD, professor of psychiatry, Harvard Medical School, and director of the depression clinical and research program at Massachusetts General Hospital, both in Boston, said that data on omega-3s in depression are “very mixed.”

“A lot of the studies don’t necessarily agree with each other. Certainly, in studies that try to seek an association between omega-3 use and depression, it’s always complicated because it can be difficult to control for all variables that could be contributing to the result that you get,” said Dr. Mischoulon, who is also a member of the Anxiety and Depression Association of America and was not involved in the research.

A caveat to the current study was that diet was assessed only at baseline, “so we don’t really know whether there were any substantial dietary changes over time, he noted.

He also cautioned that it is hard to draw any firm conclusions from this type of study.

“In general, in studies with a large sample, which this study has, it’s easier to find statistically significant differences. But you need to ask yourself: Does it really matter? Is it enough to have a clinical impact and make a difference?” Dr. Mischoulon said.

The ELSA-Brasil study was funded by the Brazilian Ministry of Science, Technology, and Innovation and by the Ministry of Health. The investigators have reported no relevant financial relationships. Dr. Mischoulon has received research support from Nordic Naturals and heckel medizintechnik GmbH and honoraria for speaking from the Massachusetts General Hospital Psychiatry Academy. He also works with the MGH Clinical Trials Network and Institute, which has received research funding from multiple pharmaceutical companies and the National Institute of Mental Health.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM NUTRIENTS

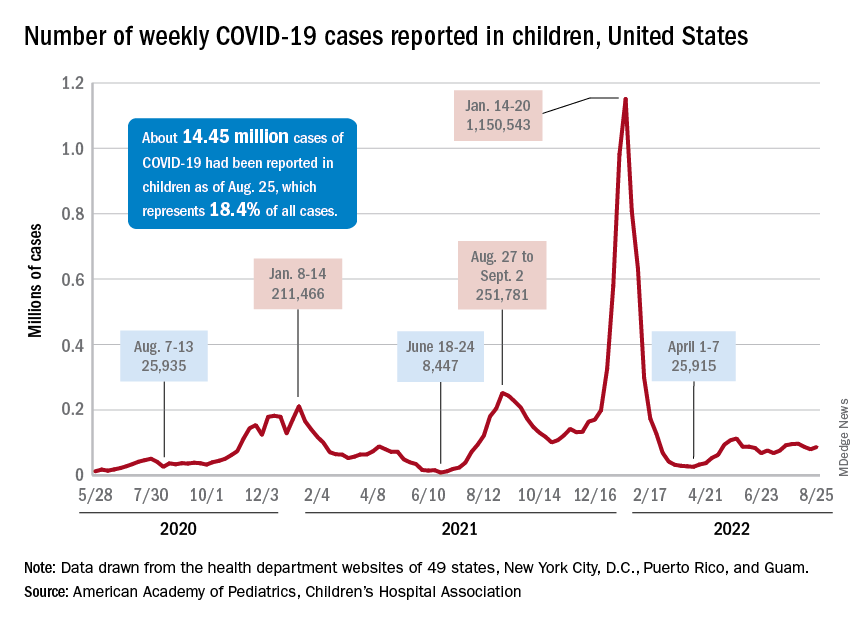

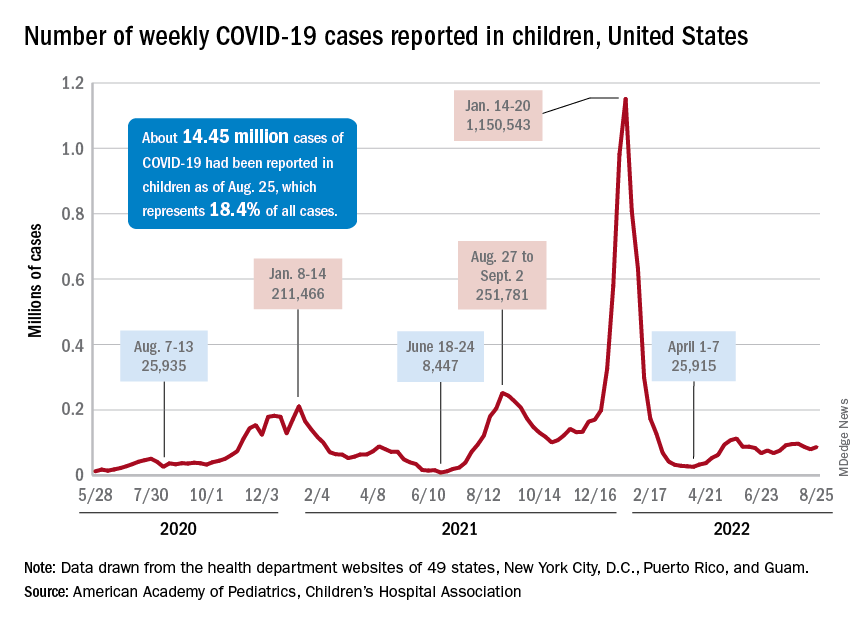

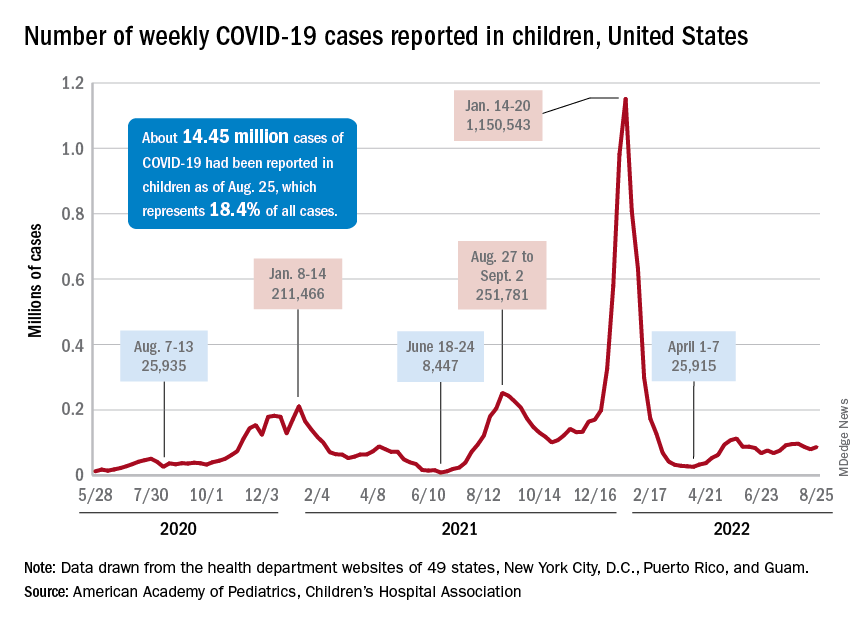

Children and COVID: New cases increase; hospital admissions could follow

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

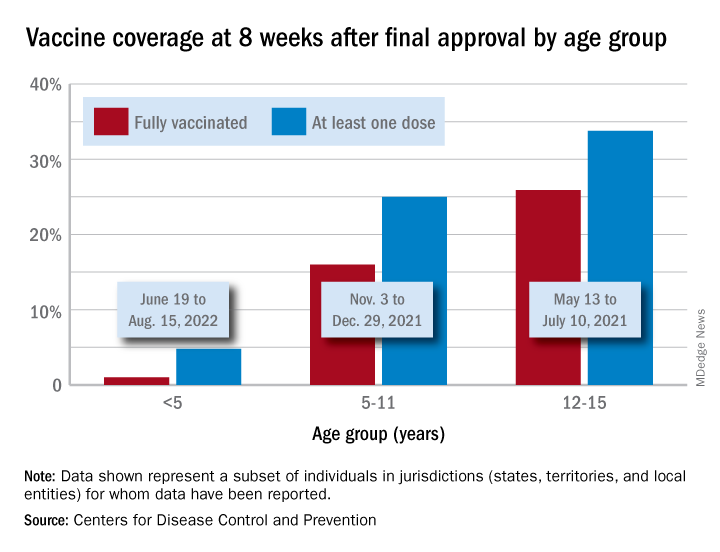

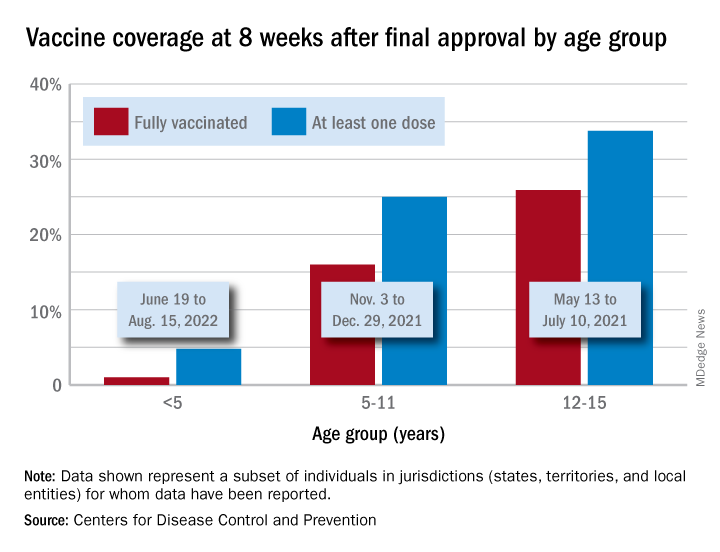

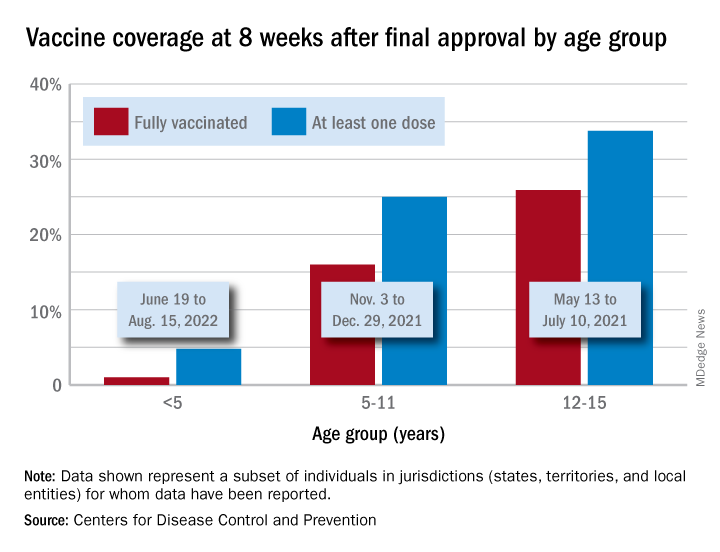

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

New cases of COVID-19 in children were up again after 2 weeks of declines, and preliminary data suggest that hospitalizations may be on the rise as well.

, based on data collected by the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Children’s Hospital Association from state and territorial health departments.

A similar increase seems to be reflected by hospital-level data. The latest 7-day (Aug. 21-27) average is 305 new admissions with diagnosed COVID per day among children aged 0-17 years, compared with 290 per day for the week of Aug. 14-20, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported, while also noting the potential for reporting delays in the most recent 7-day period.

Daily hospital admissions for COVID had been headed downward through the first half of August, falling from 0.46 per 100,000 population at the end of July to 0.40 on Aug. 19, the CDC said on its COVID Data Tracker. Since then, however, admissions have gone the other way, with the preliminary nature of the latest data suggesting that the numbers will be even higher as more hospitals report over the next few days.

Vaccine initiations continue to fall

Initiations among school-age children have fallen for 3 consecutive weeks since Aug. 3, when numbers receiving their first vaccinations reached late-summer highs for those aged 5-11 and 12-17 years. Children under age 5, included in the CDC data for the first time on Aug. 11 as separate groups – under 2 years and 2-4 years – have had vaccine initiations drop by 8.0% and 19.8% over the 2 following weeks, the CDC said.

Through their first 8 weeks of vaccine eligibility (June 19 to Aug. 15), 4.8% of children under 5 years of age had received a first vaccination and 1.0% were fully vaccinated. For the two other age groups (5-11 and 12-15) who became eligible after the very first emergency authorization back in 2020, the respective proportions were 25.0% and 16.0% (5-11) and 33.8% and 26.1% (12-15) through the first 8 weeks, according to CDC data.

‘Doomscrolling’ may be a significant driver of poor mental health

The past 2 years have been filled with worrisome global events, from the pandemic to the war in Ukraine, large-scale protests, mass shootings, and devastating wildfires. The 24-hour media coverage of these events can take a toll on “news addicts” who have an excessive urge to constantly check the news, researchers note.

Results from an online survey of more than 1,000 adults showed that nearly 17% showed signs of “severely problematic” news consumption.

These “doomscrollers” or “doomsurfers” scored high on all five problematic news consumption dimensions: being absorbed in news content, being consumed by thoughts about the news, attempting to alleviate feelings of threat by consuming more news, losing control over news consumption, and having news consumption interfere in daily life.

“We anticipated that a sizable portion of our sample would show signs of problematic news consumption. However, we were surprised to find that 17% of study participants suffer from the most severe level of problematic news consumption,” lead author Bryan McLaughlin, PhD, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, told this news organization. “This is certainly concerning and suggests the problem may be more widespread than we expected,” he said.

In addition, 74% of those with severe levels of problematic news consumption reported experiencing mental problems, and 61% reported physical problems.

“It’s important for health care providers to be aware that problematic news consumption may be a significant driver of mental and physical ill-being, especially because a lot of people might be unaware of the negative impact the news is having on their health,” Dr. McLaughlin said.

The findings were published online in Health Communication.

Emotionally invested

The researchers assessed data from an online survey of 1,100 adults (mean age, 40.5 years; 51% women) in the United States who were recruited in August 2021.

Among those surveyed, 27.3% reported “moderately problematic” news consumption, 27.5% reported minimally problematic news consumption, and 28.7% reported no problematic news consumption.

Perhaps not surprisingly, respondents with higher levels of problematic news consumption were significantly more likely to experience mental and physical ill-being than those with lower levels, even after accounting for demographics, personality traits, and overall news use, the researchers note.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of those with severe levels of problematic news consumption reported experiencing mental ill-being “quite a bit” or “very much” – whereas frequent symptoms were only reported by 8% of all other study participants.

In addition, 61% of adults with severe problematic news consumption reported experiencing physical ill-being “quite a bit” or “very much,” compared with only 6.1% for all other study participants.

Dr. McLaughlin noted that one way to combat this problem is to help individuals develop a healthier relationship with the news – and mindfulness training may be one way to accomplish that.

“We have some preliminary evidence that individuals with high levels of mindfulness are much less susceptible to developing higher levels of problematic news consumption,” he said.

“Given this, mindfulness-based training could potentially help problematic news consumers follow the news without becoming so emotionally invested in it. We hope to examine the effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention in our future research,” he added.

Increased distress

Commenting on the study, Steven R. Thorp, PhD, ABPP, a professor at California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University, San Diego, said that he and his colleagues have noticed an increase in clients reporting distress about news consumption.

The survey by Dr. McLaughlin and colleagues “appears to be representative and has sufficient statistical power to address the issues,” said Dr. Thorp, who was not involved with the research.

“However, as the researchers note, it is a cross-sectional and correlational survey. So it’s possible that, as implied, people who ‘doomscroll’ are more likely to have physical and mental health problems that interfere with their functioning,” he added.

It is also possible that individuals with physical and mental health problems are more likely to be isolated and have restricted activities, thus leading to greater news consumption, Dr. Thorp noted. Alternatively, there could be an independent link between health and news consumption.

Most news is “sensational and not representative,” Dr. Thorp pointed out.

For example, “we are far more likely to hear about deaths from terrorist attacks or plane crashes than from heart attacks, though deaths from heart attacks are far more common,” he said.

“News also tends to be negative, rather than uplifting, and most news is not directly relevant to a person’s day-to-day functioning. Thus, for most people, the consumption of news may have more downsides than upsides,” Dr. Thorp added.

Still, many people want to stay informed about national and international events. So rather than following a “cold turkey” or abstinence model of stopping all news consumption, individuals could consider a “harm reduction” model of reducing time spent consuming news, Dr. Thorp noted.

Another thing to consider is the news source. “Some outlets and social media sites are designed to instill outrage, fear, or anger and to increase polarization, while others have been shown to provide balanced and less sensational coverage,” Dr. Thorp said.

“I also think it’s a good idea for providers to regularly ask about news consumption, along with learning about other daily activities that may enhance or diminish mental and physical health,” he added.

The research had no specific funding. Dr. McLaughlin and Dr. Thorp have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The past 2 years have been filled with worrisome global events, from the pandemic to the war in Ukraine, large-scale protests, mass shootings, and devastating wildfires. The 24-hour media coverage of these events can take a toll on “news addicts” who have an excessive urge to constantly check the news, researchers note.

Results from an online survey of more than 1,000 adults showed that nearly 17% showed signs of “severely problematic” news consumption.

These “doomscrollers” or “doomsurfers” scored high on all five problematic news consumption dimensions: being absorbed in news content, being consumed by thoughts about the news, attempting to alleviate feelings of threat by consuming more news, losing control over news consumption, and having news consumption interfere in daily life.

“We anticipated that a sizable portion of our sample would show signs of problematic news consumption. However, we were surprised to find that 17% of study participants suffer from the most severe level of problematic news consumption,” lead author Bryan McLaughlin, PhD, Texas Tech University, Lubbock, told this news organization. “This is certainly concerning and suggests the problem may be more widespread than we expected,” he said.

In addition, 74% of those with severe levels of problematic news consumption reported experiencing mental problems, and 61% reported physical problems.

“It’s important for health care providers to be aware that problematic news consumption may be a significant driver of mental and physical ill-being, especially because a lot of people might be unaware of the negative impact the news is having on their health,” Dr. McLaughlin said.

The findings were published online in Health Communication.

Emotionally invested

The researchers assessed data from an online survey of 1,100 adults (mean age, 40.5 years; 51% women) in the United States who were recruited in August 2021.

Among those surveyed, 27.3% reported “moderately problematic” news consumption, 27.5% reported minimally problematic news consumption, and 28.7% reported no problematic news consumption.

Perhaps not surprisingly, respondents with higher levels of problematic news consumption were significantly more likely to experience mental and physical ill-being than those with lower levels, even after accounting for demographics, personality traits, and overall news use, the researchers note.

Nearly three-quarters (74%) of those with severe levels of problematic news consumption reported experiencing mental ill-being “quite a bit” or “very much” – whereas frequent symptoms were only reported by 8% of all other study participants.

In addition, 61% of adults with severe problematic news consumption reported experiencing physical ill-being “quite a bit” or “very much,” compared with only 6.1% for all other study participants.

Dr. McLaughlin noted that one way to combat this problem is to help individuals develop a healthier relationship with the news – and mindfulness training may be one way to accomplish that.

“We have some preliminary evidence that individuals with high levels of mindfulness are much less susceptible to developing higher levels of problematic news consumption,” he said.

“Given this, mindfulness-based training could potentially help problematic news consumers follow the news without becoming so emotionally invested in it. We hope to examine the effectiveness of a mindfulness intervention in our future research,” he added.

Increased distress

Commenting on the study, Steven R. Thorp, PhD, ABPP, a professor at California School of Professional Psychology, Alliant International University, San Diego, said that he and his colleagues have noticed an increase in clients reporting distress about news consumption.

The survey by Dr. McLaughlin and colleagues “appears to be representative and has sufficient statistical power to address the issues,” said Dr. Thorp, who was not involved with the research.

“However, as the researchers note, it is a cross-sectional and correlational survey. So it’s possible that, as implied, people who ‘doomscroll’ are more likely to have physical and mental health problems that interfere with their functioning,” he added.

It is also possible that individuals with physical and mental health problems are more likely to be isolated and have restricted activities, thus leading to greater news consumption, Dr. Thorp noted. Alternatively, there could be an independent link between health and news consumption.

Most news is “sensational and not representative,” Dr. Thorp pointed out.

For example, “we are far more likely to hear about deaths from terrorist attacks or plane crashes than from heart attacks, though deaths from heart attacks are far more common,” he said.

“News also tends to be negative, rather than uplifting, and most news is not directly relevant to a person’s day-to-day functioning. Thus, for most people, the consumption of news may have more downsides than upsides,” Dr. Thorp added.

Still, many people want to stay informed about national and international events. So rather than following a “cold turkey” or abstinence model of stopping all news consumption, individuals could consider a “harm reduction” model of reducing time spent consuming news, Dr. Thorp noted.

Another thing to consider is the news source. “Some outlets and social media sites are designed to instill outrage, fear, or anger and to increase polarization, while others have been shown to provide balanced and less sensational coverage,” Dr. Thorp said.

“I also think it’s a good idea for providers to regularly ask about news consumption, along with learning about other daily activities that may enhance or diminish mental and physical health,” he added.

The research had no specific funding. Dr. McLaughlin and Dr. Thorp have reported no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The past 2 years have been filled with worrisome global events, from the pandemic to the war in Ukraine, large-scale protests, mass shootings, and devastating wildfires. The 24-hour media coverage of these events can take a toll on “news addicts” who have an excessive urge to constantly check the news, researchers note.

Results from an online survey of more than 1,000 adults showed that nearly 17% showed signs of “severely problematic” news consumption.