User login

Bringing you the latest news, research and reviews, exclusive interviews, podcasts, quizzes, and more.

div[contains(@class, 'header__large-screen')]

div[contains(@class, 'read-next-article')]

div[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-primary')]

section[contains(@class, 'footer-nav-section-wrapper')]

footer[@id='footer']

div[contains(@class, 'main-prefix')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

div[contains(@class, 'ce-card-content')]

nav[contains(@class, 'nav-ce-stack')]

Counterfeit HIV drugs: Justice Department opens investigation

Since the start of the pandemic, supply-chain problems have permeated just about every industry sector. While most of the media attention has focused on toilet paper and retail shipment delays, a darker, more sinister supply chain disruption has been unfolding, one that entails a sophisticated criminal enterprise that has been operating at scale to distribute and profit from counterfeit HIV drugs.

Recently, news has emerged – most notably in the Wall Street Journal – with reports of a Justice Department investigation into what appears to be a national drug trafficking network comprising more than 70 distributors and marketers.

The details read like a best-selling crime novel.

Since last year, authorities have seized 85,247 bottles of counterfeit HIV drugs, both Biktarvy (bictegravir 50 mg, emtricitabine 200 mg, and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets) and Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets). Law enforcement has conducted raids at 17 locations in eight states. Doctored supply chain papers have provided cover for the fake medicines and the individuals behind them.

But unlike the inconvenience of sparse toilet paper, this crime poses life-threatening risks to millions of patients with HIV who rely on Biktarvy to suppress the virus or Descovy to prevent infection from it. Even worse, some patients have been exposed to over-the-counter painkillers or the antipsychotic drug quetiapine fumarate masquerading as HIV drugs in legitimate but repurposed bottles.

Gilead Sciences (Foster City, Calif.), which manufactures both Biktarvy and Descovy, declined to comment when contacted, instead referring this news organization to previous press statements.

Falsified HIV medications, illicit purchases over 2 Years

On Aug. 5, 2021, Gilead first warned the public that it had become aware of tampered and counterfeit Biktarvy and Descovy tablets. In coordination with the Food and Drug Administration, it alerted pharmacies to “investigate the potential for counterfeit or tampered Gilead medication sold by [unauthorized] distributors that may be within their recent supply.”

On Jan. 19, 2022, Gilead issued a second statement outlining ongoing actions in coordination with U.S. marshals and local law enforcement to remove these illegal medications from circulation and prevent further distribution.

The timing of the most recent announcement was not accidental. The day before, a federal judge serving the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York unsealed documents detailing the company’s lawsuit against dozens of individuals and entities who they alleged had engaged in a highly coordinated effort to defraud pharmacies and consumers. The suit followed two prior Gilead filings that ultimately resulted in court-issued ex parte seizure orders (orders that allow a court to seize property without the property owner’s consent) and the recovery of more than 1,000 bottles containing questionable Gilead medications.

The lawsuit centered on Cambridge, Mass.–based wholesale pharmaceutical distributor Safe Chain Solutions and its two cofounders. The document is peppered with terms such as “shifting series of fly-by-night corporate entities,” “gray market” distributors, a “dedicated sales force,” and “shell entities,” along with accusations that the defendants were believed to have made purchases of gold bullion, jewelry, and other luxury items for conversion into cash.

In a curious twist of fate, this sinister effort appeared to have been first revealed not by a pharmacist but by a patient who had returned a bottle of Biktarvy with “foreign medication inside” to the California pharmacy that dispensed it.

“Specifically with HIV medications, there’s no point in which the pharmacy is actually opening the bottle, breaking the seal, and counting out pills to put into a smaller prescription bottle,” Emily Heil, PharmD, BCIDP, AAHIVP, associate professor of infectious diseases in the department of pharmacy practice and science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“But that’s also why pharmacies work with these centralized groups of distributors that maintain a chain of command and fidelity with drug manufacturers so that we don’t run into these situations,” she said.

This is the link in the chain where that tightly coordinated and highly regulated process was broken.

Although Gilead and Safe Chain Solutions were informed of the incident as early as August 2020, the distributor repeatedly refused to identify the supplier and the pedigree (the record demonstrating the chain of all sales or transfers of a specific drug, going back to the manufacturer, as required by the FDA’s Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013).

Later that year, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson issued a media statement saying that they had been alerted to the distribution of counterfeit Symtuza (darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) to three pharmacies in the United States.

A spokesperson for the FDA declined to comment on the ongoing investigation when contacted by this news organization and instead wrote in an email that the agency “will continue to use all available tools to ensure consumers and patients have access to a safe and effective medical product supply.”

Old dog, new tricks

This is not the first time that HIV drugs have been targeted for criminal benefit. An analysis published in September 2014 in JAMA highlighted a federal investigation that year into a $32 million dollar scheme to defraud Medicare’s Part D program for HIV drugs and divert them for resale on the black market.

What’s more, prior research and news reports highlight the attractiveness of HIV drug diversion both for the buyer and the seller – not only because of the cost of the drugs themselves but also because of institutional or systemic deficiencies that exclude certain individuals from obtaining treatment through federal initiatives such as the Ryan White/AIDS Drug Assistance program.

In its most recent statement, Gilead reinforced that this practice remains alive and well.

On the buyer side, the company stated, many of the counterfeits originated from suppliers who purchased Gilead HIV medication from individuals after it was first dispensed to them. Unfortunately, the exploitation of individuals with low incomes who experience homelessness or substance use/abuse echoes a pattern whereby HIV patients sell medications to cover personal needs or are forced to buy them on the black market to keep up with their treatment regimens.

On the supply side, All of these counterfeits were sold as though they were legitimate Gilead products.”

But counterfeit pedigrees make it impossible to verify where the products came from, how they have been handled and stored, and what pills are in the bottles – all of which can have dire consequences for patients who ingest them.

The ramifications can be devastating.

“With HIV meds specifically, the worst case scenario would be if the medication is not actually the medication they’re supposed to be on,” said Dr. Heil, reinforcing that the increased safety net provided with viral suppression and against transmission is lost.

Dr. Heil pointed to another significant risk: resistance.

“In a situation like this, where maybe it’s not the full strength of the medication, maybe it’s expired and lost potency or was not stored correctly or is not even the accurate medication, changing those drug level exposures potentially puts the patient at risk for developing resistance to their regimen without them knowing.”

Yet another risk was posed by the replacement of HIV drugs with other medications, such as quetiapine, which increased the risk for life-threatening and irreversible side effects. The lawsuit included a story of a patient who unknowingly took quetiapine after receiving a counterfeit bottle of Biktarvy and could not speak or walk afterward.

Where this tale will ultimately end is unclear. There’s no telling what other activities or bad actors the Justice Department investigation will uncover as it works to unravel the counterfeit network’s activities and deal with its aftermath.

Regardless, clinicians are encouraged to inform HIV patients about the risks associated with counterfeit medications, how to determine whether the drugs they’ve been dispensed are authentic, and to report any product they believe to be counterfeit or to have been tampered with to their doctors, pharmacies, and to Gilead or other drug manufacturers.

“It’s okay to ask questions of your pharmacy about where they get their medications from,” noted Dr. Heil. “If patients have access to an independent pharmacy, it’s a great way for them to have a relationship with their pharmacist.

“We went into this profession to be able to have those conversations with patients,” Dr. Heil said.

The FDA recommends that patients receiving these medications who believe that their drugs may be counterfeit or who experience any adverse effects report the event to FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program (1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch).

Dr. Heil reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the start of the pandemic, supply-chain problems have permeated just about every industry sector. While most of the media attention has focused on toilet paper and retail shipment delays, a darker, more sinister supply chain disruption has been unfolding, one that entails a sophisticated criminal enterprise that has been operating at scale to distribute and profit from counterfeit HIV drugs.

Recently, news has emerged – most notably in the Wall Street Journal – with reports of a Justice Department investigation into what appears to be a national drug trafficking network comprising more than 70 distributors and marketers.

The details read like a best-selling crime novel.

Since last year, authorities have seized 85,247 bottles of counterfeit HIV drugs, both Biktarvy (bictegravir 50 mg, emtricitabine 200 mg, and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets) and Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets). Law enforcement has conducted raids at 17 locations in eight states. Doctored supply chain papers have provided cover for the fake medicines and the individuals behind them.

But unlike the inconvenience of sparse toilet paper, this crime poses life-threatening risks to millions of patients with HIV who rely on Biktarvy to suppress the virus or Descovy to prevent infection from it. Even worse, some patients have been exposed to over-the-counter painkillers or the antipsychotic drug quetiapine fumarate masquerading as HIV drugs in legitimate but repurposed bottles.

Gilead Sciences (Foster City, Calif.), which manufactures both Biktarvy and Descovy, declined to comment when contacted, instead referring this news organization to previous press statements.

Falsified HIV medications, illicit purchases over 2 Years

On Aug. 5, 2021, Gilead first warned the public that it had become aware of tampered and counterfeit Biktarvy and Descovy tablets. In coordination with the Food and Drug Administration, it alerted pharmacies to “investigate the potential for counterfeit or tampered Gilead medication sold by [unauthorized] distributors that may be within their recent supply.”

On Jan. 19, 2022, Gilead issued a second statement outlining ongoing actions in coordination with U.S. marshals and local law enforcement to remove these illegal medications from circulation and prevent further distribution.

The timing of the most recent announcement was not accidental. The day before, a federal judge serving the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York unsealed documents detailing the company’s lawsuit against dozens of individuals and entities who they alleged had engaged in a highly coordinated effort to defraud pharmacies and consumers. The suit followed two prior Gilead filings that ultimately resulted in court-issued ex parte seizure orders (orders that allow a court to seize property without the property owner’s consent) and the recovery of more than 1,000 bottles containing questionable Gilead medications.

The lawsuit centered on Cambridge, Mass.–based wholesale pharmaceutical distributor Safe Chain Solutions and its two cofounders. The document is peppered with terms such as “shifting series of fly-by-night corporate entities,” “gray market” distributors, a “dedicated sales force,” and “shell entities,” along with accusations that the defendants were believed to have made purchases of gold bullion, jewelry, and other luxury items for conversion into cash.

In a curious twist of fate, this sinister effort appeared to have been first revealed not by a pharmacist but by a patient who had returned a bottle of Biktarvy with “foreign medication inside” to the California pharmacy that dispensed it.

“Specifically with HIV medications, there’s no point in which the pharmacy is actually opening the bottle, breaking the seal, and counting out pills to put into a smaller prescription bottle,” Emily Heil, PharmD, BCIDP, AAHIVP, associate professor of infectious diseases in the department of pharmacy practice and science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“But that’s also why pharmacies work with these centralized groups of distributors that maintain a chain of command and fidelity with drug manufacturers so that we don’t run into these situations,” she said.

This is the link in the chain where that tightly coordinated and highly regulated process was broken.

Although Gilead and Safe Chain Solutions were informed of the incident as early as August 2020, the distributor repeatedly refused to identify the supplier and the pedigree (the record demonstrating the chain of all sales or transfers of a specific drug, going back to the manufacturer, as required by the FDA’s Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013).

Later that year, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson issued a media statement saying that they had been alerted to the distribution of counterfeit Symtuza (darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) to three pharmacies in the United States.

A spokesperson for the FDA declined to comment on the ongoing investigation when contacted by this news organization and instead wrote in an email that the agency “will continue to use all available tools to ensure consumers and patients have access to a safe and effective medical product supply.”

Old dog, new tricks

This is not the first time that HIV drugs have been targeted for criminal benefit. An analysis published in September 2014 in JAMA highlighted a federal investigation that year into a $32 million dollar scheme to defraud Medicare’s Part D program for HIV drugs and divert them for resale on the black market.

What’s more, prior research and news reports highlight the attractiveness of HIV drug diversion both for the buyer and the seller – not only because of the cost of the drugs themselves but also because of institutional or systemic deficiencies that exclude certain individuals from obtaining treatment through federal initiatives such as the Ryan White/AIDS Drug Assistance program.

In its most recent statement, Gilead reinforced that this practice remains alive and well.

On the buyer side, the company stated, many of the counterfeits originated from suppliers who purchased Gilead HIV medication from individuals after it was first dispensed to them. Unfortunately, the exploitation of individuals with low incomes who experience homelessness or substance use/abuse echoes a pattern whereby HIV patients sell medications to cover personal needs or are forced to buy them on the black market to keep up with their treatment regimens.

On the supply side, All of these counterfeits were sold as though they were legitimate Gilead products.”

But counterfeit pedigrees make it impossible to verify where the products came from, how they have been handled and stored, and what pills are in the bottles – all of which can have dire consequences for patients who ingest them.

The ramifications can be devastating.

“With HIV meds specifically, the worst case scenario would be if the medication is not actually the medication they’re supposed to be on,” said Dr. Heil, reinforcing that the increased safety net provided with viral suppression and against transmission is lost.

Dr. Heil pointed to another significant risk: resistance.

“In a situation like this, where maybe it’s not the full strength of the medication, maybe it’s expired and lost potency or was not stored correctly or is not even the accurate medication, changing those drug level exposures potentially puts the patient at risk for developing resistance to their regimen without them knowing.”

Yet another risk was posed by the replacement of HIV drugs with other medications, such as quetiapine, which increased the risk for life-threatening and irreversible side effects. The lawsuit included a story of a patient who unknowingly took quetiapine after receiving a counterfeit bottle of Biktarvy and could not speak or walk afterward.

Where this tale will ultimately end is unclear. There’s no telling what other activities or bad actors the Justice Department investigation will uncover as it works to unravel the counterfeit network’s activities and deal with its aftermath.

Regardless, clinicians are encouraged to inform HIV patients about the risks associated with counterfeit medications, how to determine whether the drugs they’ve been dispensed are authentic, and to report any product they believe to be counterfeit or to have been tampered with to their doctors, pharmacies, and to Gilead or other drug manufacturers.

“It’s okay to ask questions of your pharmacy about where they get their medications from,” noted Dr. Heil. “If patients have access to an independent pharmacy, it’s a great way for them to have a relationship with their pharmacist.

“We went into this profession to be able to have those conversations with patients,” Dr. Heil said.

The FDA recommends that patients receiving these medications who believe that their drugs may be counterfeit or who experience any adverse effects report the event to FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program (1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch).

Dr. Heil reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Since the start of the pandemic, supply-chain problems have permeated just about every industry sector. While most of the media attention has focused on toilet paper and retail shipment delays, a darker, more sinister supply chain disruption has been unfolding, one that entails a sophisticated criminal enterprise that has been operating at scale to distribute and profit from counterfeit HIV drugs.

Recently, news has emerged – most notably in the Wall Street Journal – with reports of a Justice Department investigation into what appears to be a national drug trafficking network comprising more than 70 distributors and marketers.

The details read like a best-selling crime novel.

Since last year, authorities have seized 85,247 bottles of counterfeit HIV drugs, both Biktarvy (bictegravir 50 mg, emtricitabine 200 mg, and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets) and Descovy (emtricitabine 200 mg and tenofovir alafenamide 25 mg tablets). Law enforcement has conducted raids at 17 locations in eight states. Doctored supply chain papers have provided cover for the fake medicines and the individuals behind them.

But unlike the inconvenience of sparse toilet paper, this crime poses life-threatening risks to millions of patients with HIV who rely on Biktarvy to suppress the virus or Descovy to prevent infection from it. Even worse, some patients have been exposed to over-the-counter painkillers or the antipsychotic drug quetiapine fumarate masquerading as HIV drugs in legitimate but repurposed bottles.

Gilead Sciences (Foster City, Calif.), which manufactures both Biktarvy and Descovy, declined to comment when contacted, instead referring this news organization to previous press statements.

Falsified HIV medications, illicit purchases over 2 Years

On Aug. 5, 2021, Gilead first warned the public that it had become aware of tampered and counterfeit Biktarvy and Descovy tablets. In coordination with the Food and Drug Administration, it alerted pharmacies to “investigate the potential for counterfeit or tampered Gilead medication sold by [unauthorized] distributors that may be within their recent supply.”

On Jan. 19, 2022, Gilead issued a second statement outlining ongoing actions in coordination with U.S. marshals and local law enforcement to remove these illegal medications from circulation and prevent further distribution.

The timing of the most recent announcement was not accidental. The day before, a federal judge serving the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of New York unsealed documents detailing the company’s lawsuit against dozens of individuals and entities who they alleged had engaged in a highly coordinated effort to defraud pharmacies and consumers. The suit followed two prior Gilead filings that ultimately resulted in court-issued ex parte seizure orders (orders that allow a court to seize property without the property owner’s consent) and the recovery of more than 1,000 bottles containing questionable Gilead medications.

The lawsuit centered on Cambridge, Mass.–based wholesale pharmaceutical distributor Safe Chain Solutions and its two cofounders. The document is peppered with terms such as “shifting series of fly-by-night corporate entities,” “gray market” distributors, a “dedicated sales force,” and “shell entities,” along with accusations that the defendants were believed to have made purchases of gold bullion, jewelry, and other luxury items for conversion into cash.

In a curious twist of fate, this sinister effort appeared to have been first revealed not by a pharmacist but by a patient who had returned a bottle of Biktarvy with “foreign medication inside” to the California pharmacy that dispensed it.

“Specifically with HIV medications, there’s no point in which the pharmacy is actually opening the bottle, breaking the seal, and counting out pills to put into a smaller prescription bottle,” Emily Heil, PharmD, BCIDP, AAHIVP, associate professor of infectious diseases in the department of pharmacy practice and science at the University of Maryland School of Pharmacy, Baltimore, told this news organization.

“But that’s also why pharmacies work with these centralized groups of distributors that maintain a chain of command and fidelity with drug manufacturers so that we don’t run into these situations,” she said.

This is the link in the chain where that tightly coordinated and highly regulated process was broken.

Although Gilead and Safe Chain Solutions were informed of the incident as early as August 2020, the distributor repeatedly refused to identify the supplier and the pedigree (the record demonstrating the chain of all sales or transfers of a specific drug, going back to the manufacturer, as required by the FDA’s Drug Supply Chain Security Act in 2013).

Later that year, Janssen Pharmaceutical Companies of Johnson & Johnson issued a media statement saying that they had been alerted to the distribution of counterfeit Symtuza (darunavir/cobicistat/emtricitabine/tenofovir alafenamide) to three pharmacies in the United States.

A spokesperson for the FDA declined to comment on the ongoing investigation when contacted by this news organization and instead wrote in an email that the agency “will continue to use all available tools to ensure consumers and patients have access to a safe and effective medical product supply.”

Old dog, new tricks

This is not the first time that HIV drugs have been targeted for criminal benefit. An analysis published in September 2014 in JAMA highlighted a federal investigation that year into a $32 million dollar scheme to defraud Medicare’s Part D program for HIV drugs and divert them for resale on the black market.

What’s more, prior research and news reports highlight the attractiveness of HIV drug diversion both for the buyer and the seller – not only because of the cost of the drugs themselves but also because of institutional or systemic deficiencies that exclude certain individuals from obtaining treatment through federal initiatives such as the Ryan White/AIDS Drug Assistance program.

In its most recent statement, Gilead reinforced that this practice remains alive and well.

On the buyer side, the company stated, many of the counterfeits originated from suppliers who purchased Gilead HIV medication from individuals after it was first dispensed to them. Unfortunately, the exploitation of individuals with low incomes who experience homelessness or substance use/abuse echoes a pattern whereby HIV patients sell medications to cover personal needs or are forced to buy them on the black market to keep up with their treatment regimens.

On the supply side, All of these counterfeits were sold as though they were legitimate Gilead products.”

But counterfeit pedigrees make it impossible to verify where the products came from, how they have been handled and stored, and what pills are in the bottles – all of which can have dire consequences for patients who ingest them.

The ramifications can be devastating.

“With HIV meds specifically, the worst case scenario would be if the medication is not actually the medication they’re supposed to be on,” said Dr. Heil, reinforcing that the increased safety net provided with viral suppression and against transmission is lost.

Dr. Heil pointed to another significant risk: resistance.

“In a situation like this, where maybe it’s not the full strength of the medication, maybe it’s expired and lost potency or was not stored correctly or is not even the accurate medication, changing those drug level exposures potentially puts the patient at risk for developing resistance to their regimen without them knowing.”

Yet another risk was posed by the replacement of HIV drugs with other medications, such as quetiapine, which increased the risk for life-threatening and irreversible side effects. The lawsuit included a story of a patient who unknowingly took quetiapine after receiving a counterfeit bottle of Biktarvy and could not speak or walk afterward.

Where this tale will ultimately end is unclear. There’s no telling what other activities or bad actors the Justice Department investigation will uncover as it works to unravel the counterfeit network’s activities and deal with its aftermath.

Regardless, clinicians are encouraged to inform HIV patients about the risks associated with counterfeit medications, how to determine whether the drugs they’ve been dispensed are authentic, and to report any product they believe to be counterfeit or to have been tampered with to their doctors, pharmacies, and to Gilead or other drug manufacturers.

“It’s okay to ask questions of your pharmacy about where they get their medications from,” noted Dr. Heil. “If patients have access to an independent pharmacy, it’s a great way for them to have a relationship with their pharmacist.

“We went into this profession to be able to have those conversations with patients,” Dr. Heil said.

The FDA recommends that patients receiving these medications who believe that their drugs may be counterfeit or who experience any adverse effects report the event to FDA’s MedWatch Safety Information and Adverse Event Reporting Program (1-800-FDA-1088 or www.fda.gov/medwatch).

Dr. Heil reported having no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

Adolescent overdose deaths nearly doubled in 2020 and spiked again in 2021

The number of overdose deaths in adolescents nearly doubled in 2020 from the year before and increased substantially again in 2021 after nearly a decade of fairly stable rates, according to data published in a JAMA research letter.

Most of the deaths involved fentanyl, the researchers found.

Joseph Friedman, MPH, of the Center for Social Medicine and Humanities at the University of California, Los Angeles, led the study, which analyzed adolescent (14-18 years old) overdose deaths in the United States from 2010 to June 2021 in light of increasing contamination in the supply of illicit drugs.

The researchers found there were 518 deaths among adolescents (2.40 per 100,000 population) in 2010, and the rates remained stable through 2019 with 492 deaths (2.36 per 100,000).

In 2020, however, deaths spiked to 954 (4.57 per 100 000), increasing by 94.3%, compared with 2019. In 2021, they increased another 20%.

The rise in fentanyl-involved deaths was particularly striking. Fentanyl-involved deaths increased from 253 (1.21 per 100,000) in 2019 to 680 (3.26 per 100,000) in 2020. The numbers through June 2021 were annualized for 2021 and calculations predicted 884 deaths (4.23 per 100,000) for the year.

Numbers point to fentanyl potency

In 2021, more than three-fourths (77.14%) of adolescent overdose deaths involved fentanyl, compared with 13.26% for benzodiazepines, 9.77% for methamphetamine, 7.33% for cocaine, 5.76% for prescription opioids, and 2.27% for heroin.

American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents had the highest overdose rate in 2021 (n = 24; 11.79 per 100,000), followed by Latinx adolescents (n = 354; 6.98 per 100,000).

“These adolescent trends fit a wider pattern of increasing racial and ethnic inequalities in overdose that deserve further investigation and intervention efforts,” the authors wrote.

Pandemic’s role unclear

The spikes in adolescent overdoses overlap the COVID-19 pandemic, but Dr. Friedman said in an interview the pandemic “may or may not have been a big factor. “

The authors wrote that drug use had generally been stable among adolescents between 2010 and 2020. The number of 10th graders reporting any illicit drug use was 30.2% in 2010 and 30.4% in 2020.

“So it’s not that more teens are using drugs. It’s just that drug use is becoming more dangerous due to the spread of counterfeit pills containing fentanyls,” Dr. Friedman said.

The authors noted that “the illicit drug supply has increasingly become contaminated with illicitly manufactured fentanyls and other synthetic opioid and benzodiazepine analogues.”

Mr. Friedman said the pandemic may have accelerated the spread of more dangerous forms of drugs as supply chains were disrupted.

Benjamin Brady, DrPH, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who also has an appointment in the university’s Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center, said in an interview the numbers that Dr. Friedman and colleagues present represent “worst fears coming true.”

He said he and his colleagues in the field “were anticipating a rise in overdose deaths for the next 5-10 years because of the way the supply-and-demand environment exists in the U.S.”

Dr. Brady explained that restricting access to prescription opioids has had an unfortunate side effect in decreasing access to a safer supply of drugs.

“Without having solutions that would reduce demand at the same rate, supply of the safer form of the drug has been reduced; that has pushed people toward heroin and street drugs and from 2016 on those have been adulterated with fentanyl,” he said.

He said the United States, compared with other developed nations, has been slower to embrace longer-term harm-reduction strategies and to improve access to treatment and care.

COVID likely also has exacerbated the problem in terms of isolation and reduction in quality of life that has adolescents seeking to fill that void with drugs, Dr. Brady said. They may be completely unaware that the drugs they are seeking are commonly cut with counterfeit fentanyl.

“Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin,” he noted. “Even just a little bit of fentanyl dramatically changes the risk profile on an overdose.”

Increasing rates of mental health concerns among adolescents over decades also contribute to drug-seeking trends, Dr. Brady noted.

Overdose increases in the overall population were smaller

In the overall population, the percentage increases were not nearly as large in 2020 and 2021 as they were for adolescents.

Rates of overdose deaths in the overall population increased steadily from 2010 and reached 70,630 in 2019. In 2020, the deaths increased to 91,799 (an increase of 29.48% from 2019) and increased 11.48% in 2021.

The researchers analyzed numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database, which has records of all U.S. deaths for which drug overdose was listed as the underlying cause.

The authors and Dr. Brady report no relevant financial relationships.

The number of overdose deaths in adolescents nearly doubled in 2020 from the year before and increased substantially again in 2021 after nearly a decade of fairly stable rates, according to data published in a JAMA research letter.

Most of the deaths involved fentanyl, the researchers found.

Joseph Friedman, MPH, of the Center for Social Medicine and Humanities at the University of California, Los Angeles, led the study, which analyzed adolescent (14-18 years old) overdose deaths in the United States from 2010 to June 2021 in light of increasing contamination in the supply of illicit drugs.

The researchers found there were 518 deaths among adolescents (2.40 per 100,000 population) in 2010, and the rates remained stable through 2019 with 492 deaths (2.36 per 100,000).

In 2020, however, deaths spiked to 954 (4.57 per 100 000), increasing by 94.3%, compared with 2019. In 2021, they increased another 20%.

The rise in fentanyl-involved deaths was particularly striking. Fentanyl-involved deaths increased from 253 (1.21 per 100,000) in 2019 to 680 (3.26 per 100,000) in 2020. The numbers through June 2021 were annualized for 2021 and calculations predicted 884 deaths (4.23 per 100,000) for the year.

Numbers point to fentanyl potency

In 2021, more than three-fourths (77.14%) of adolescent overdose deaths involved fentanyl, compared with 13.26% for benzodiazepines, 9.77% for methamphetamine, 7.33% for cocaine, 5.76% for prescription opioids, and 2.27% for heroin.

American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents had the highest overdose rate in 2021 (n = 24; 11.79 per 100,000), followed by Latinx adolescents (n = 354; 6.98 per 100,000).

“These adolescent trends fit a wider pattern of increasing racial and ethnic inequalities in overdose that deserve further investigation and intervention efforts,” the authors wrote.

Pandemic’s role unclear

The spikes in adolescent overdoses overlap the COVID-19 pandemic, but Dr. Friedman said in an interview the pandemic “may or may not have been a big factor. “

The authors wrote that drug use had generally been stable among adolescents between 2010 and 2020. The number of 10th graders reporting any illicit drug use was 30.2% in 2010 and 30.4% in 2020.

“So it’s not that more teens are using drugs. It’s just that drug use is becoming more dangerous due to the spread of counterfeit pills containing fentanyls,” Dr. Friedman said.

The authors noted that “the illicit drug supply has increasingly become contaminated with illicitly manufactured fentanyls and other synthetic opioid and benzodiazepine analogues.”

Mr. Friedman said the pandemic may have accelerated the spread of more dangerous forms of drugs as supply chains were disrupted.

Benjamin Brady, DrPH, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who also has an appointment in the university’s Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center, said in an interview the numbers that Dr. Friedman and colleagues present represent “worst fears coming true.”

He said he and his colleagues in the field “were anticipating a rise in overdose deaths for the next 5-10 years because of the way the supply-and-demand environment exists in the U.S.”

Dr. Brady explained that restricting access to prescription opioids has had an unfortunate side effect in decreasing access to a safer supply of drugs.

“Without having solutions that would reduce demand at the same rate, supply of the safer form of the drug has been reduced; that has pushed people toward heroin and street drugs and from 2016 on those have been adulterated with fentanyl,” he said.

He said the United States, compared with other developed nations, has been slower to embrace longer-term harm-reduction strategies and to improve access to treatment and care.

COVID likely also has exacerbated the problem in terms of isolation and reduction in quality of life that has adolescents seeking to fill that void with drugs, Dr. Brady said. They may be completely unaware that the drugs they are seeking are commonly cut with counterfeit fentanyl.

“Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin,” he noted. “Even just a little bit of fentanyl dramatically changes the risk profile on an overdose.”

Increasing rates of mental health concerns among adolescents over decades also contribute to drug-seeking trends, Dr. Brady noted.

Overdose increases in the overall population were smaller

In the overall population, the percentage increases were not nearly as large in 2020 and 2021 as they were for adolescents.

Rates of overdose deaths in the overall population increased steadily from 2010 and reached 70,630 in 2019. In 2020, the deaths increased to 91,799 (an increase of 29.48% from 2019) and increased 11.48% in 2021.

The researchers analyzed numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database, which has records of all U.S. deaths for which drug overdose was listed as the underlying cause.

The authors and Dr. Brady report no relevant financial relationships.

The number of overdose deaths in adolescents nearly doubled in 2020 from the year before and increased substantially again in 2021 after nearly a decade of fairly stable rates, according to data published in a JAMA research letter.

Most of the deaths involved fentanyl, the researchers found.

Joseph Friedman, MPH, of the Center for Social Medicine and Humanities at the University of California, Los Angeles, led the study, which analyzed adolescent (14-18 years old) overdose deaths in the United States from 2010 to June 2021 in light of increasing contamination in the supply of illicit drugs.

The researchers found there were 518 deaths among adolescents (2.40 per 100,000 population) in 2010, and the rates remained stable through 2019 with 492 deaths (2.36 per 100,000).

In 2020, however, deaths spiked to 954 (4.57 per 100 000), increasing by 94.3%, compared with 2019. In 2021, they increased another 20%.

The rise in fentanyl-involved deaths was particularly striking. Fentanyl-involved deaths increased from 253 (1.21 per 100,000) in 2019 to 680 (3.26 per 100,000) in 2020. The numbers through June 2021 were annualized for 2021 and calculations predicted 884 deaths (4.23 per 100,000) for the year.

Numbers point to fentanyl potency

In 2021, more than three-fourths (77.14%) of adolescent overdose deaths involved fentanyl, compared with 13.26% for benzodiazepines, 9.77% for methamphetamine, 7.33% for cocaine, 5.76% for prescription opioids, and 2.27% for heroin.

American Indian and Alaska Native adolescents had the highest overdose rate in 2021 (n = 24; 11.79 per 100,000), followed by Latinx adolescents (n = 354; 6.98 per 100,000).

“These adolescent trends fit a wider pattern of increasing racial and ethnic inequalities in overdose that deserve further investigation and intervention efforts,” the authors wrote.

Pandemic’s role unclear

The spikes in adolescent overdoses overlap the COVID-19 pandemic, but Dr. Friedman said in an interview the pandemic “may or may not have been a big factor. “

The authors wrote that drug use had generally been stable among adolescents between 2010 and 2020. The number of 10th graders reporting any illicit drug use was 30.2% in 2010 and 30.4% in 2020.

“So it’s not that more teens are using drugs. It’s just that drug use is becoming more dangerous due to the spread of counterfeit pills containing fentanyls,” Dr. Friedman said.

The authors noted that “the illicit drug supply has increasingly become contaminated with illicitly manufactured fentanyls and other synthetic opioid and benzodiazepine analogues.”

Mr. Friedman said the pandemic may have accelerated the spread of more dangerous forms of drugs as supply chains were disrupted.

Benjamin Brady, DrPH, an assistant professor at the University of Arizona, Tucson, who also has an appointment in the university’s Comprehensive Pain and Addiction Center, said in an interview the numbers that Dr. Friedman and colleagues present represent “worst fears coming true.”

He said he and his colleagues in the field “were anticipating a rise in overdose deaths for the next 5-10 years because of the way the supply-and-demand environment exists in the U.S.”

Dr. Brady explained that restricting access to prescription opioids has had an unfortunate side effect in decreasing access to a safer supply of drugs.

“Without having solutions that would reduce demand at the same rate, supply of the safer form of the drug has been reduced; that has pushed people toward heroin and street drugs and from 2016 on those have been adulterated with fentanyl,” he said.

He said the United States, compared with other developed nations, has been slower to embrace longer-term harm-reduction strategies and to improve access to treatment and care.

COVID likely also has exacerbated the problem in terms of isolation and reduction in quality of life that has adolescents seeking to fill that void with drugs, Dr. Brady said. They may be completely unaware that the drugs they are seeking are commonly cut with counterfeit fentanyl.

“Fentanyl can be up to 50 times stronger than heroin,” he noted. “Even just a little bit of fentanyl dramatically changes the risk profile on an overdose.”

Increasing rates of mental health concerns among adolescents over decades also contribute to drug-seeking trends, Dr. Brady noted.

Overdose increases in the overall population were smaller

In the overall population, the percentage increases were not nearly as large in 2020 and 2021 as they were for adolescents.

Rates of overdose deaths in the overall population increased steadily from 2010 and reached 70,630 in 2019. In 2020, the deaths increased to 91,799 (an increase of 29.48% from 2019) and increased 11.48% in 2021.

The researchers analyzed numbers from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention WONDER (Wide-Ranging Online Data for Epidemiologic Research) database, which has records of all U.S. deaths for which drug overdose was listed as the underlying cause.

The authors and Dr. Brady report no relevant financial relationships.

FROM JAMA

Study: Disparities shrink with aggressive depression screening

The study began soon after the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended depression screening for all adults in 2016. The task force based this recommendation on evidence that people who are screened and treated experience fewer debilitating symptoms.

In the new research, the investigators analyzed electronic health record data following a rollout of a universal depression screening program at the University of California, San Francisco. The researchers found that the overall rate of depression screening doubled at six primary care practices over a little more than 2 years, reaching nearly 90%. The investigators presented the data April 9 at the Society of General Internal Medicine 2022 Annual Meeting in Orlando.

Meanwhile, screening disparities diminished for men, older individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and people with language barriers – all groups that are undertreated for depression.

“It shows that if a health system is really invested, it can achieve really high depression screening,” primary investigator Maria Garcia, MD, MPH, co-director of UCSF’s Multiethnic Health Equity Research Center, told this news organization.

Methods for identifying depression

The health system assigned medical assistants to administer annual screening using a validated tool, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). A “yes” response to either of its two questions triggered a longer questionnaire, the PHQ-9, used to diagnose and guide treatment.

Screening forms were available in multiple languages. Medical assistants received training on the importance of identifying depression in undertreated groups, and a banner was inserted in the electronic health record to indicate a screening was due, Dr. Garcia said.

During the rollout, a committee was assigned to monitor screening rates and adjust strategies to target disparities.

Dr. Garcia and fellow researchers calculated the likelihood of a patient being screened starting in September 2017 – when a field for depression screening status was added to the system’s electronic health record – until the rollout was completed on Dec. 31, 2019.

Screening disparities narrowed for all groups studied

The screening rate for patients who had a primary care visit increased from 40.5% to 88.8%. Early on, patients with language barriers were less likely to be screened than English-speaking White individuals (odds ratios, 0.55-0.59). Men were less likely to be screened than women (OR, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.86), and the likelihood of being screened decreased as people got older. By 2019, screening disparities had narrowed for all groups and were only statistically significant for men (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.81-0.93).

Ian Kronish, MD, MPH, a general internist and associate professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, called the increases “impressive,” adding that the data show universal depression screening is possible in a system that serves a diverse population.

Dr. Kronish, who was not involved in this study, noted that other research indicates screening does not result in a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the overall population. He found this to be the case in a trial he led, which focused on patients with recent cardiac events, for example.

“Given all the effort that is going into depression screening and the inclusion of depression screening as a quality metric, we need definitive randomized clinical trials testing whether depression screening leads to increased treatment uptake and, importantly, improved depressive symptoms and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Garcia acknowledged that more work needs to be done to address treatment barriers, such as language and lack of insurance, and assess whether greater recognition of depressive symptoms in underserved groups can lead to effective treatment. “But this is an important step to know that universal depression screening narrowed disparities in screening over time,” she added.

Dr. Garcia and Dr. Kronish have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study began soon after the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended depression screening for all adults in 2016. The task force based this recommendation on evidence that people who are screened and treated experience fewer debilitating symptoms.

In the new research, the investigators analyzed electronic health record data following a rollout of a universal depression screening program at the University of California, San Francisco. The researchers found that the overall rate of depression screening doubled at six primary care practices over a little more than 2 years, reaching nearly 90%. The investigators presented the data April 9 at the Society of General Internal Medicine 2022 Annual Meeting in Orlando.

Meanwhile, screening disparities diminished for men, older individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and people with language barriers – all groups that are undertreated for depression.

“It shows that if a health system is really invested, it can achieve really high depression screening,” primary investigator Maria Garcia, MD, MPH, co-director of UCSF’s Multiethnic Health Equity Research Center, told this news organization.

Methods for identifying depression

The health system assigned medical assistants to administer annual screening using a validated tool, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). A “yes” response to either of its two questions triggered a longer questionnaire, the PHQ-9, used to diagnose and guide treatment.

Screening forms were available in multiple languages. Medical assistants received training on the importance of identifying depression in undertreated groups, and a banner was inserted in the electronic health record to indicate a screening was due, Dr. Garcia said.

During the rollout, a committee was assigned to monitor screening rates and adjust strategies to target disparities.

Dr. Garcia and fellow researchers calculated the likelihood of a patient being screened starting in September 2017 – when a field for depression screening status was added to the system’s electronic health record – until the rollout was completed on Dec. 31, 2019.

Screening disparities narrowed for all groups studied

The screening rate for patients who had a primary care visit increased from 40.5% to 88.8%. Early on, patients with language barriers were less likely to be screened than English-speaking White individuals (odds ratios, 0.55-0.59). Men were less likely to be screened than women (OR, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.86), and the likelihood of being screened decreased as people got older. By 2019, screening disparities had narrowed for all groups and were only statistically significant for men (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.81-0.93).

Ian Kronish, MD, MPH, a general internist and associate professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, called the increases “impressive,” adding that the data show universal depression screening is possible in a system that serves a diverse population.

Dr. Kronish, who was not involved in this study, noted that other research indicates screening does not result in a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the overall population. He found this to be the case in a trial he led, which focused on patients with recent cardiac events, for example.

“Given all the effort that is going into depression screening and the inclusion of depression screening as a quality metric, we need definitive randomized clinical trials testing whether depression screening leads to increased treatment uptake and, importantly, improved depressive symptoms and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Garcia acknowledged that more work needs to be done to address treatment barriers, such as language and lack of insurance, and assess whether greater recognition of depressive symptoms in underserved groups can lead to effective treatment. “But this is an important step to know that universal depression screening narrowed disparities in screening over time,” she added.

Dr. Garcia and Dr. Kronish have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

The study began soon after the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommended depression screening for all adults in 2016. The task force based this recommendation on evidence that people who are screened and treated experience fewer debilitating symptoms.

In the new research, the investigators analyzed electronic health record data following a rollout of a universal depression screening program at the University of California, San Francisco. The researchers found that the overall rate of depression screening doubled at six primary care practices over a little more than 2 years, reaching nearly 90%. The investigators presented the data April 9 at the Society of General Internal Medicine 2022 Annual Meeting in Orlando.

Meanwhile, screening disparities diminished for men, older individuals, racial and ethnic minorities, and people with language barriers – all groups that are undertreated for depression.

“It shows that if a health system is really invested, it can achieve really high depression screening,” primary investigator Maria Garcia, MD, MPH, co-director of UCSF’s Multiethnic Health Equity Research Center, told this news organization.

Methods for identifying depression

The health system assigned medical assistants to administer annual screening using a validated tool, the Patient Health Questionnaire-2 (PHQ-2). A “yes” response to either of its two questions triggered a longer questionnaire, the PHQ-9, used to diagnose and guide treatment.

Screening forms were available in multiple languages. Medical assistants received training on the importance of identifying depression in undertreated groups, and a banner was inserted in the electronic health record to indicate a screening was due, Dr. Garcia said.

During the rollout, a committee was assigned to monitor screening rates and adjust strategies to target disparities.

Dr. Garcia and fellow researchers calculated the likelihood of a patient being screened starting in September 2017 – when a field for depression screening status was added to the system’s electronic health record – until the rollout was completed on Dec. 31, 2019.

Screening disparities narrowed for all groups studied

The screening rate for patients who had a primary care visit increased from 40.5% to 88.8%. Early on, patients with language barriers were less likely to be screened than English-speaking White individuals (odds ratios, 0.55-0.59). Men were less likely to be screened than women (OR, 0.82; 95% confidence interval, 0.78-0.86), and the likelihood of being screened decreased as people got older. By 2019, screening disparities had narrowed for all groups and were only statistically significant for men (OR, 0.87; 95% CI, 0.81-0.93).

Ian Kronish, MD, MPH, a general internist and associate professor of medicine at Columbia University, New York, called the increases “impressive,” adding that the data show universal depression screening is possible in a system that serves a diverse population.

Dr. Kronish, who was not involved in this study, noted that other research indicates screening does not result in a significant reduction in depressive symptoms in the overall population. He found this to be the case in a trial he led, which focused on patients with recent cardiac events, for example.

“Given all the effort that is going into depression screening and the inclusion of depression screening as a quality metric, we need definitive randomized clinical trials testing whether depression screening leads to increased treatment uptake and, importantly, improved depressive symptoms and quality of life,” he said.

Dr. Garcia acknowledged that more work needs to be done to address treatment barriers, such as language and lack of insurance, and assess whether greater recognition of depressive symptoms in underserved groups can lead to effective treatment. “But this is an important step to know that universal depression screening narrowed disparities in screening over time,” she added.

Dr. Garcia and Dr. Kronish have disclosed no relevant financial relationships.

A version of this article first appeared on Medscape.com.

FROM SGIM 2022

Diagnostic challenges in primary care: Identifying and avoiding cognitive bias

Medical errors in all settings contributed to as many as 250,000 deaths per year in the United States between 2000 and 2008, according to a 2016 study.1 Diagnostic error, in particular, remains a leading cause of morbidity and mortality in the United States and worldwide. In 2017, 12 million patients (roughly 5% of all US adults) who sought outpatient care experienced missed, delayed, or incorrect diagnosis at least once.2

In his classic work, How Doctors Think, Jerome Groopman, MD, explored the diagnostic process with a focus on the role of cognitive bias in clinical decision-making. Groopman examined how physicians can become sidetracked in their thinking and “blinded” to potential alternative diagnoses.3 Medical error is not necessarily because of a deficiency in medical knowledge; rather, physicians become susceptible to medical error when defective and faulty reasoning distort their diagnostic ability.4

Cognitive bias in the diagnostic process has been extensively studied, and a full review is beyond the scope of this article.5 However, here we will examine pathways leading to diagnostic errors in the primary care setting, specifically the role of cognitive bias in the work-up of polymyalgia rheumatica (PMR), ovarian cancer (OC), Lewy body dementia (LBD), and fibromyalgia (FM). As these 4 disease states are seen with low-to-moderate frequency in primary care, cognitive bias can complicate accurate diagnosis. But first, a word about how to understand clinical reasoning.

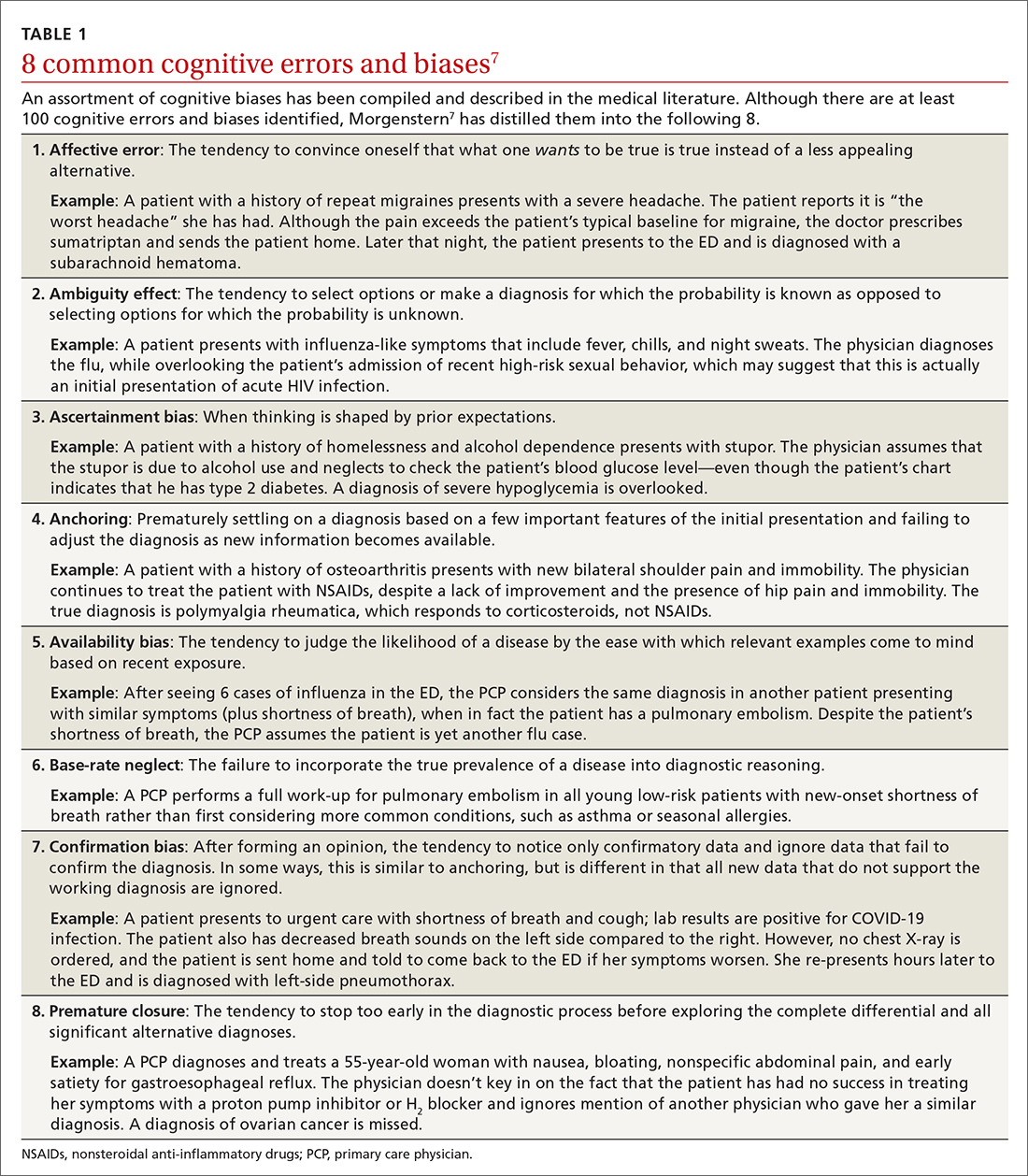

There are 2 types of reasoning (and 1 is more prone to error)

Physician clinical reasoning can be divided into 2 different cognitive approaches.

Type 1 reasoning employs intuition and heuristics; this type is automatic, reflexive, and quick.5 While the use of mental shortcuts in type 1 increases the speed with which decisions are made, it also makes this form of reasoning more prone to error.

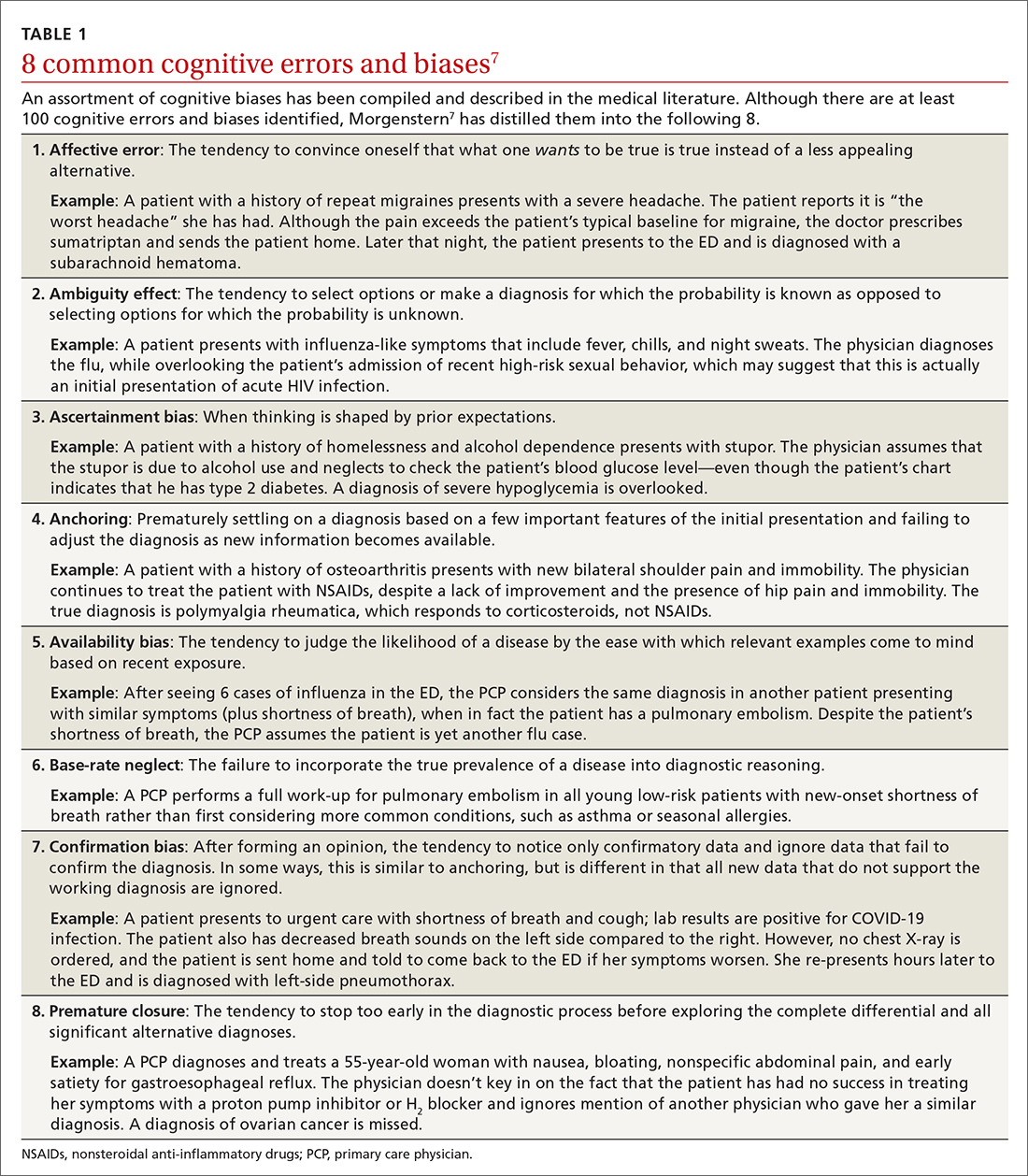

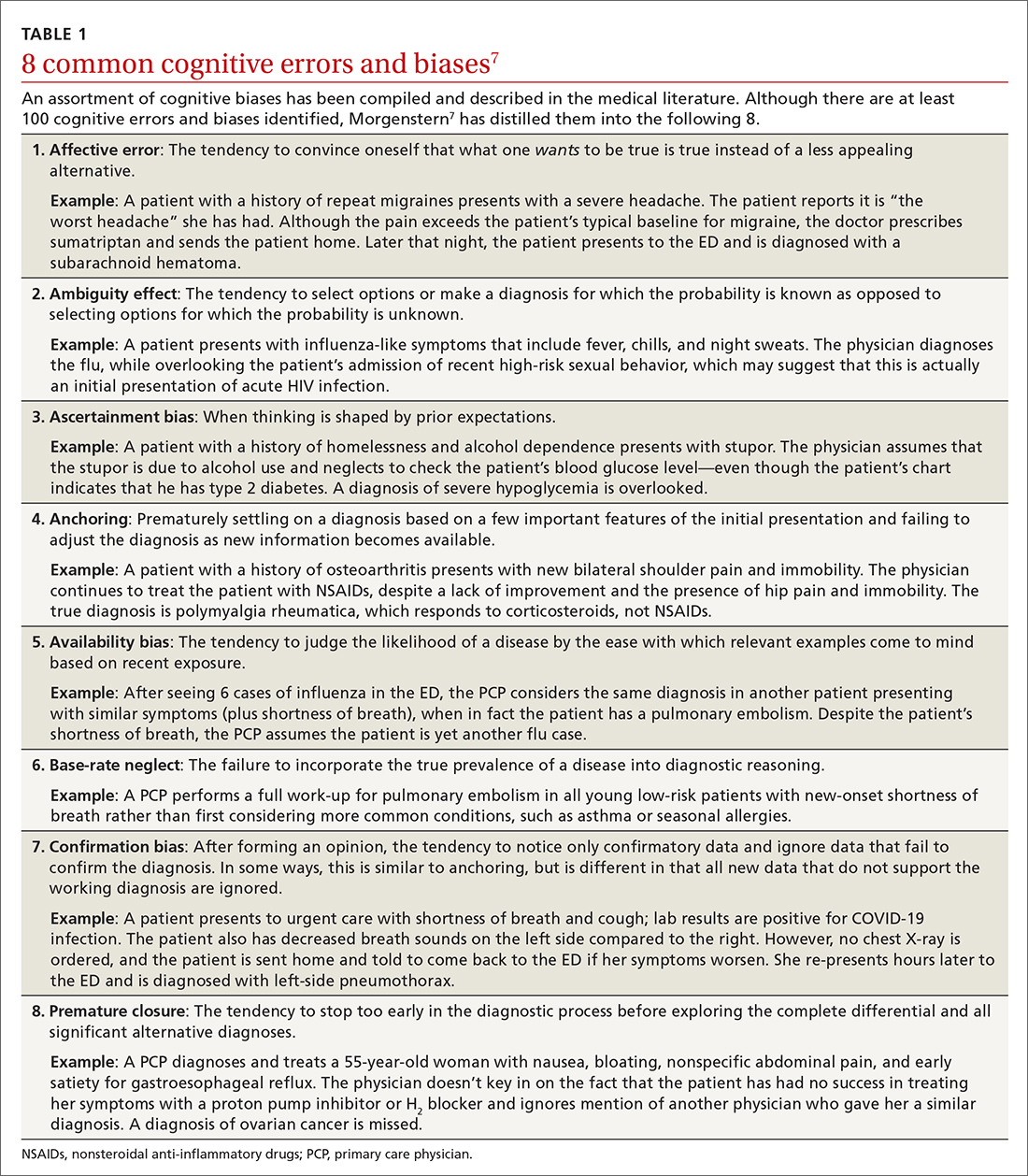

Type 2 reasoning requires conscious effort. It is goal directed and rigorous and therefore slower than type 1 reasoning. Extrapolated to the clinical context, clinicians transition from type 2 to type 1 reasoning as they gain experience and training throughout their careers and develop their own conscious and subconscious heuristics. Deviations from accurate decision-making occur in a systematic manner due to cognitive biases and result in medical error.6table 17 lists common types of cognitive bias.

An important question to ask. Physicians tend to fall into a pattern of quick, type 1 reasoning. However, it’s important to strive to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and avoid premature closure of the diagnostic process. It’s critical that we consider alternative diagnoses (ie, consciously move from type 1 to type 2 thinking) and continue to ask ourselves, “What else?” while working through differential diagnoses. This can be a powerful debiasing technique.

Continue to: The discussion...

The discussion of the following 4 disease states demonstrates how cognitive bias can lead to diagnostic error.

The patient is barely able to ambulate and appears to be in considerable pain. She is relying heavily on her walker and is assisted by her granddaughter. The primary care physician (PCP) obtains a detailed history that includes chronic shoulder and hip pain. Given that the patient has not responded to NSAID treatment over the previous 6 months, the PCP takes a moment to reconsider the diagnosis of OA and considers other options.

In light of the high prevalence of PMR in older women, the physician pursues a more specific physical examination tailored to ferret out PMR. He had learned this diagnostic shortcut as a resident, remembered it, and adeptly applied it whenever circumstances warranted. He asks the patient to raise her arms above her head (goalpost sign). She is unable to perform this task and experiences severe bilateral shoulder pain on trial. The PCP then places the patient on the examining table and attempts to assist her in rolling toward him. The patient is also unable to perform this maneuver and experiences significant bilateral hip pain on trial.

Based primarily on the patient’s history and physical exam findings, the PCP makes a presumptive diagnosis of PMR vs OA vs combined PMR with OA, orders an erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) and basic rheumatologic

PMR can be mistaken for OA

PMR is the most common inflammatory rheumatic disease in older patients.8 It is a debilitating illness with simple, effective treatment but has devastating consequences if missed or left untreated.9 PMR typically manifests in patients older than age 50, with a peak incidence at 80 years of age. It is also far more common in women.10

Approximately 80% of patients with PMR initially present to their PCP, often posing a diagnostic challenge to many clinicians.11 Due to overlap in symptoms, the condition is often misdiagnosed as OA, a more common condition seen by PCPs. Also, there are no specific diagnostic tests for PMR. An elevated ESR can help confirm the diagnosis, but one-third of patients with PMR have a normal ESR.12 Therefore, the diagnostic conundrum the physician faces is OA vs rheumatoid arthritis (RA), PMR, or another condition.

Continue to: The consequences...

The consequences of a missed and delayed PMR diagnosis range from seriously impaired quality of life to significantly increased risk of vascular events (eg, blindness, stroke) due to temporal arteritis.13 Early diagnosis is even more critical as the risk of a vascular event and death is highest during initial phases of the disease course.14

FPs often miss this Dx. A timely diagnosis relies almost exclusively on an accurate, thorough history and physical exam. However, PCPs often struggle to correctly diagnose PMR. According to a study by Bahlas and colleagues,15 the accuracy rate for correctly diagnosing PMR was 24% among a cohort of family physicians.

The differential diagnosis for PMR is broad and includes seronegative spondyloarthropathies, malignancy, Lyme disease, hypothyroidism, and both RA and OA.16

PCPs are extremely adept at correctly diagnosing RA, but not PMR. A study by Blaauw and colleagues17 comparing PCPs and rheumatologists found PCPs correctly identified 92% of RA cases but only 55% of PMR cases. When rheumatologists reviewed these same cases, they correctly identified PMR and RA almost 100% of the time.17 The difference in diagnostic accuracy between rheumatologists and PCPs suggests limited experience and gaps in fund of knowledge.

Making the diagnosis. The diagnosis of PMR is often made on empiric response to corticosteroid treatment, but doing so based solely on a patient’s response is controversial.18 There are rare instances in which patients with PMR fail to respond to treatment. On the other hand, some inflammatory conditions that mimic or share symptoms with PMR also respond to corticosteroids, potentially resulting in erroneous confirmation bias.

Some classification criteria use rapid response to low-dose prednisone/prednisolone (≤ 20 mg) to confirm the diagnosis,19 while other more recent guidelines no longer include this approach.20 If PMR continues to be suspected after a trial of steroids is unsuccessful, the PCP can try another course of higher dose steroids or consult with Rheumatology.

Continue to: A full history...

A full history and physical exam revealed a myriad of gastrointestinal (GI) complaints, such as diarrhea. But the PCP recalled a recent roundtable discussion on debiasing techniques specifically related to gynecologic disorders, including OC. Therefore, he decided to include OC in the differential diagnosis—something he would not routinely have done given the preponderance of GI symptoms. Despite the patient’s reluctance and time constraints, the PCP ordered a transvaginal ultrasound. Findings from the ultrasound study revealed stage II OC, which carries a good prognosis. The patient is currently undergoing treatment and was last reported as doing well.

Early signs of ovarian cancer can be chalked up to a “GI issue”

OC is the second most common gynecologic cancer21 and the fifth leading cause of cancer-related death22 in US women. Compared to other cancers, the prognosis for localized early-stage OC is surprisingly good, with a 5-year survival rate approaching 93%.23 However, most disease is detected in later stages, and the 5-year survival rate drops to a low of 29%.24

There remains no established screening protocol for OC. Fewer than a quarter of all cases are diagnosed in stage I, and detection of OC relies heavily on the physician’s ability to decipher vague symptomatology that overlaps with other, more common maladies. This poses an obvious diagnostic challenge and, not surprisingly, a high level of susceptibility to cognitive bias.

More than 90% of patients with OC present with some combination of the following symptoms prior to diagnosis: abdominal (77%), GI (70%), pain (58%), constitutional (50%), urinary (34%), and pelvic (26%).25 The 3 most common isolated symptoms in patients with OC are abdominal bloating, decrease in appetite, and frank abdominal pain.26 Patients with biopsy-confirmed OC experience these symptoms an average of 6 months prior to actual diagnosis.27

Knowledge gaps play a role. Studies assessing the ability of health care providers to identify presenting symptoms of OC reveal specific knowledge gaps. For instance, in a survey by Gajjar and colleagues,28 most PCPs correctly identified bloating as a key symptom of OC; however, they weren’t as good at identifying less common symptoms, such as inability to finish a meal and early satiety. Moreover, survey participants misinterpreted or missed GI symptoms as an important manifestation of early OC disease.28 These specific knowledge gaps combine with physician errors in thinking, further obscuring and extending the diagnostic process. The point prevalence for OC is relatively low, and many PCPs only encounter a few cases during their entire career.29 This low pre-test probability may also fuel the delay in diagnosis.

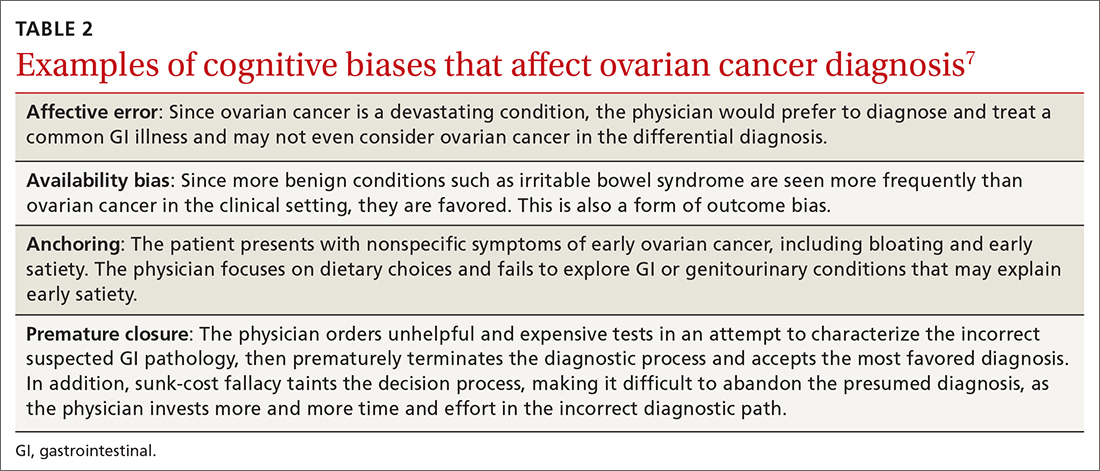

Watch for these forms of bias. Since nonspecific symptoms of early-stage OC resemble those of other more benign conditions, a form of anchoring error known as multiple alternatives bias can arise. In this scenario, clinicians investigate only 1 potential plausible diagnosis and remain focused on that single, often faulty, conclusion. This persists despite other equally plausible alternatives that arise as the investigation proceeds.28

Affective error may also play a role in missed or delayed diagnosis. For example, a physician would prefer to diagnose and treat a common GI illness than consider OC. Another distortion involves outcome bias wherein the physician gives more significance to benign conditions such as irritable bowel syndrome because they have a more favorable outcome and clear treatment path. Physicians also favor these benign conditions because they encounter them more frequently than OC in the clinic setting. (This is known as availability bias.) Outcome bias and multiple alternatives bias can result in noninvestigation of symptoms and inefficient or improper management, leading to a delay in arriving at the correct diagnosis or anchoring on a plausible but incorrect diagnosis.

Continue to: An incorrect initial diagnostic...

An incorrect initial diagnostic path often triggers a cascade of subsequent errors. The physician orders additional unhelpful and expensive tests in an effort to characterize the suspected GI pathology. This then leads the physician to prematurely terminate the work-up and accept the most favored diagnosis. Lastly, sunk-cost fallacy comes into play: The physician has “invested” time and energy investigating a particular diagnosis and rather than abandon the presumed diagnosis, continues to put more time and effort in going down an incorrect diagnostic path.

A series of failures. These biases and miscues have been observed in several studies. For example, a survey of 1725 women by Goff and colleagues30 sought to identify factors related to delayed OC diagnosis. The authors found that the following factors were significantly associated with a delayed diagnosis: omission of a pelvic exam at initial presentation, a separate exploration of a multitude of collateral symptoms, a failure to order ultrasound/computed tomography/CA-125 test, and a failure to consider age as a factor (especially if the patient was outside the norm).

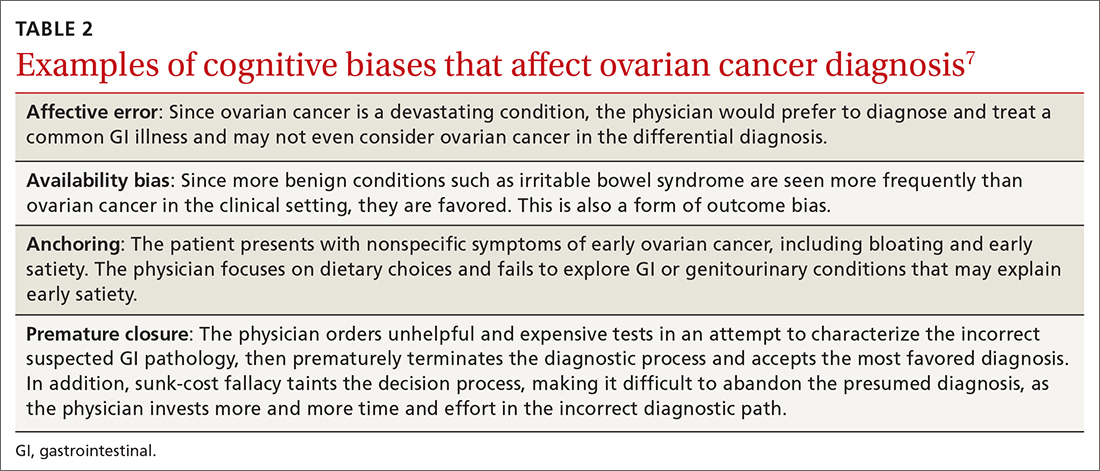

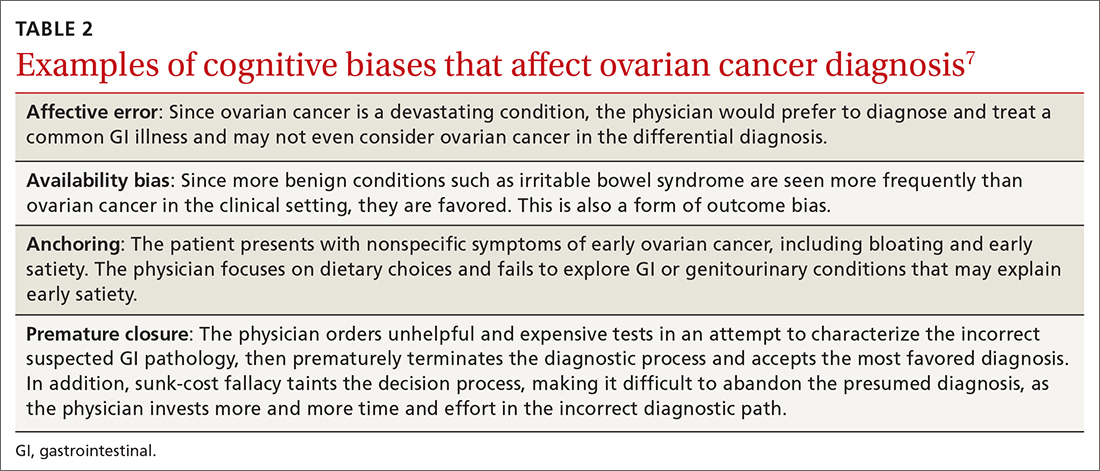

Responses from the survey also revealed that physicians initially ordered work-ups related to GI etiology and only later considered a pelvic work-up. This suggests that well-known presenting signs and symptoms or a constellation of typical and atypical symptoms of OC often failed to trigger physician recognition. Understandably, patients presenting with menorrhagia or gynecologic complaints are more likely to have OC detected at an earlier stage than patients who present with GI or abdominal signs alone.31 table 27 summarizes some of the cognitive biases seen in the diagnostic path of OC.

While in the hospital, he becomes acutely upset by the hallucinations and is given haloperidol and lorazepam by house staff. In the morning, the patient exhibits severe signs of Parkinson disease that include rigidity and masked facies.

Given the patient’s poor response to haloperidol and continued confusion, the team consulted Neurology and Psychiatry. Gathering a more detailed history from the patient and family, the patient is given a diagnosis of classic LBD. The antipsychotic medications are stopped. The patient and his family receive education about LBD treatment and management, and the patient is discharged to outpatient care.

Psychiatric symptoms can be an early “misdirect” in cases of Lewy body disease

LBD, the second leading neurodegenerative dementia after Alzheimer disease (AD), affects 1.5 million Americans,32 representing about 10% of all dementia cases. LBD and AD overlap in 25% of dementia cases.33 In patients older than 85 years, the prevalence jumps to 5% of the general population and 22% of all cases of dementia.33 Despite its prevalence, a recent study showed that only 6% of PCPs correctly identified LBD as the primary diagnosis when presented with typical case examples.32

Continue to: 3 stages of presentation

3 stages of presentation. Unlike other forms of dementia, LBD typically presents first with psychiatric symptoms, then with cognitive impairment, and last with parkinsonian symptoms. Additionally, rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder and often subtle elements of nonmemory cognitive impairment distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia.32 The primary cognitive deficit in LBD is not in memory but in attention, executive functioning, and visuospatial ability.34 Only in the later stages of the disease do patients exhibit gradual and progressive memory loss.

Mistaken for many things. When evaluating patients exhibiting signs of dementia, it’s important to include LBD in the differential, with increased suspicion for patients experiencing episodes of psychosis or delirium. The uniqueness of LBD lies in its psychotic symptomatology, particularly during earlier stages of the disease. This feature helps distinguish LBD from both AD and vascular dementia. As seen in the case, LBD can also be confused with acute delirium.

Older adult patients presenting to the ED or clinic with visual hallucinations, delirium, and mental confusion may receive a false diagnosis of schizophrenia, medication- or substance-induced psychosis, Parkinson disease, or delirium of unknown etiology.35 Unfortunately, LBD is often overlooked and not considered in the differential diagnosis. Due to underrecognition, patients may receive treatment with typical antipsychotics. The addition of a neuroleptic to help control the psychotic symptoms causes patients with LBD to develop severe extrapyramidal symptoms and worsening mental status,36 leading to severe parkinsonian signs, which further muddies the diagnostic process. In addition, treatment for suspected Parkinson disease, including carbidopa-levodopa, has no benefit for patients with LBD and may increase psychotic symptoms.37

First-line treatment for LBD includes psychoeducation for the patient and family, cholinesterase inhibitors (eg, rivastigmine), and avoidance of high-potency antipsychotics, such as haloperidol. Although persistent hallucinations and psychosis remain difficult to treat in LBD, low-dose quetiapine is 1 option. Incorrectly diagnosing and prescribing treatment for another condition exacerbates symptoms in this patient population.

The patient has been experiencing chronic pain for the past few years after a motor vehicle accident. She has seen a physiatrist and another provider, both of whom found no “objective” causes of her chronic pain. They started the patient on sertraline for depression and an analgesic, both of which were ineffective.

The patient likes to exercise at a gym twice a week by doing light cardio (treadmill) exercise and light weightlifting. Lately, however, she has been unable to exercise due to the pain. At this visit, she mentions having low energy, poor sleep, frequent fatigue, and generalized soreness and pain in multiple areas of her body. The PCP recognizes the patient’s presenting symptoms as significant for FM and starts her on pregabalin and hydrotherapy, with positive results.

Continue to: Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

Fibromyalgia skepticism may lead to a Dx of depression

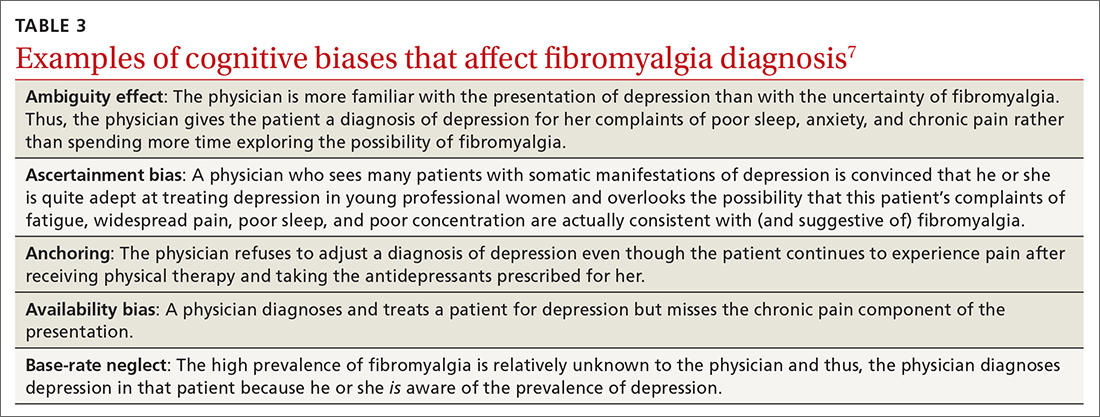

FM, the second most common disorder seen in rheumatologic practice after OA, is estimated to affect approximately 1 in 20 patients (approximately 5 million Americans) in the primary care setting.38,39 The condition has a high female-to-male preponderance (3.4% vs 0.5%).40 While the primary symptom of FM is chronic pain, patients commonly present with fatigue and sleep disturbance.41 Comorbid conditions include headaches, irritable bowel syndrome, and mood disturbances (most commonly anxiety and depression).

Several studies have explored reasons for the misdiagnosis and underdiagnosis of FM. One important factor is ongoing skepticism among some physicians and the public, in general, as to whether FM is a real disease. This issue was addressed by a study by White and colleagues,42 who estimated and compared the point prevalence of FM and related disorders in Amish vs non-Amish adults. The authors hypothesized that if litigation and/or compensation availability have a major impact on FM prevalence, then there would be a near zero prevalence of FM in the Amish community. And yet, researchers found an overall age- and sex-adjusted FM prevalence of 7.3% (95% CI; 5.3%-9.7%); this was both statistically greater than zero (P < .0001) and greater than 2 control populations of non-Amish adults (both P < .05).

Many physicians consider FM fundamentally an emotional disturbance, and the high preponderance of FM in female patients may contribute to this misconception as reports of pain and emotional distress by women are often dismissed as hysteria.43 Physicians often explore the emotional aspects of FM, incorrectly diagnosing patients with depression and subsequently treating them with a psychotropic drug.39 Alternatively, they may focus on the musculoskeletal presentations of FM and prescribe analgesics or physical therapy, both of which do little to alleviate FM.

To make the correct diagnosis of FM, the American College of Rheumatology created a specific set of criteria in 1990, which was updated in 2010.44 For a diagnosis of FM, a patient must have at least a 3-month history of bilateral pain above and below the waist and along the axial skeletal spine. Although not included in the updated 2010 criteria, many clinicians continue to check for tender points, following the 1990 criteria requiring the presence of 11 of 18 points to make the diagnosis.

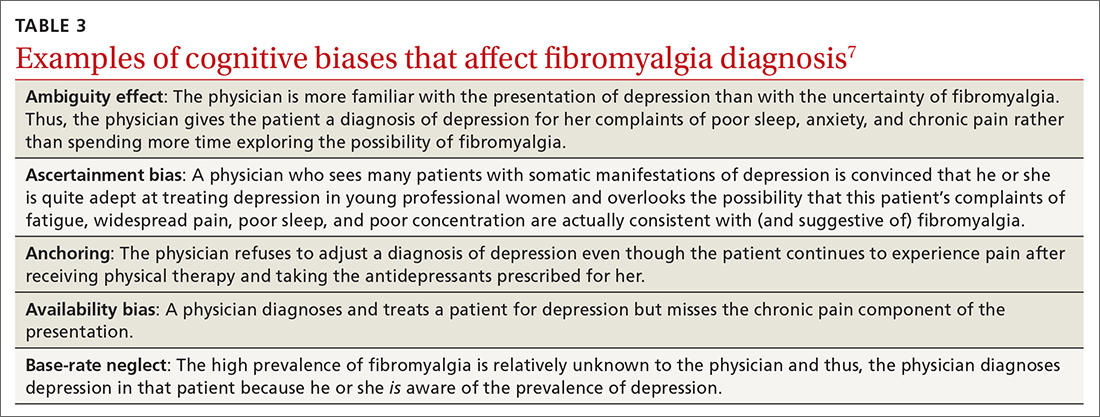

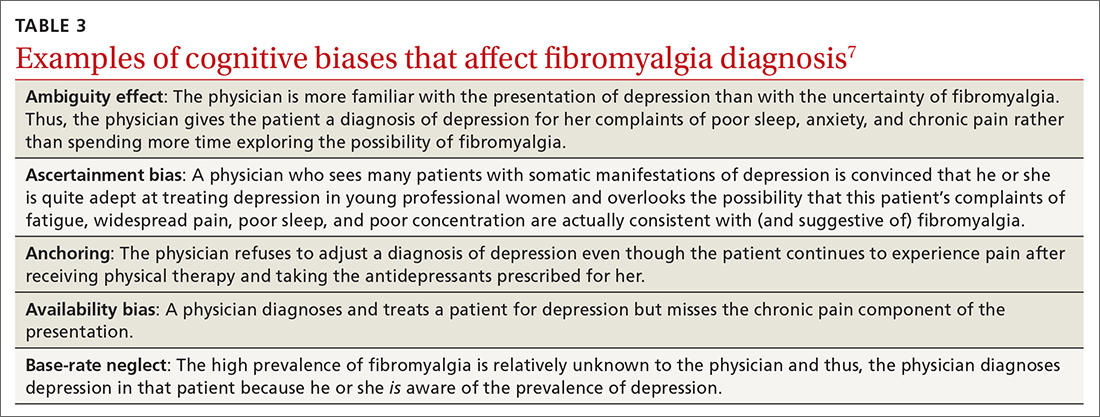

At least 3 cognitive biases relating to FM apply: anchoring, availability, and fundamental attribution error (see table 3).7 Anchoring occurs when the PCP settles on a psychiatric diagnosis of exaggerated pain syndrome, muscle overuse, or OA and fails to explore alternative etiology. Availability bias may obscure the true diagnosis of FM. Since PCPs see many patients with RA or OA, they may overlook or dismiss the possibility of FM. Attribution error happens when physicians dismiss the complaints of patients with FM as merely due to psychological distress, hysteria, or acting out.43

Patients with FM, who are often otherwise healthy, often present multiple times to the same PCP with a chief complaint of chronic pain. These repeat presentations can result in compassion fatigue and impact care. As Aloush and colleagues40 noted in their study, “FM patients were perceived as more difficult than RA patients, with a high level of concern and emotional response. A high proportion of physicians were reluctant to accept them because they feel emotional/psychological difficulties meeting and coping with these patients.”In response, patients with undiagnosed FM or inadequately treated FM may visit other PCPs, which may or may not result in a correct diagnosis and treatment.

We can do better

Primary care physicians face the daunting task of diagnosing and treating a wide range of common conditions while also trying to recognize less-common conditions with atypical presentations—all during a busy clinic workday. Nonetheless, we should strive to overcome internal (eg, cognitive bias and fund-of-knowledge deficits) and external (eg, time constraints, limited resources) pressures to improve diagnostic accuracy and care.