User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Subcutaneous Nodule on the Postauricular Neck

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

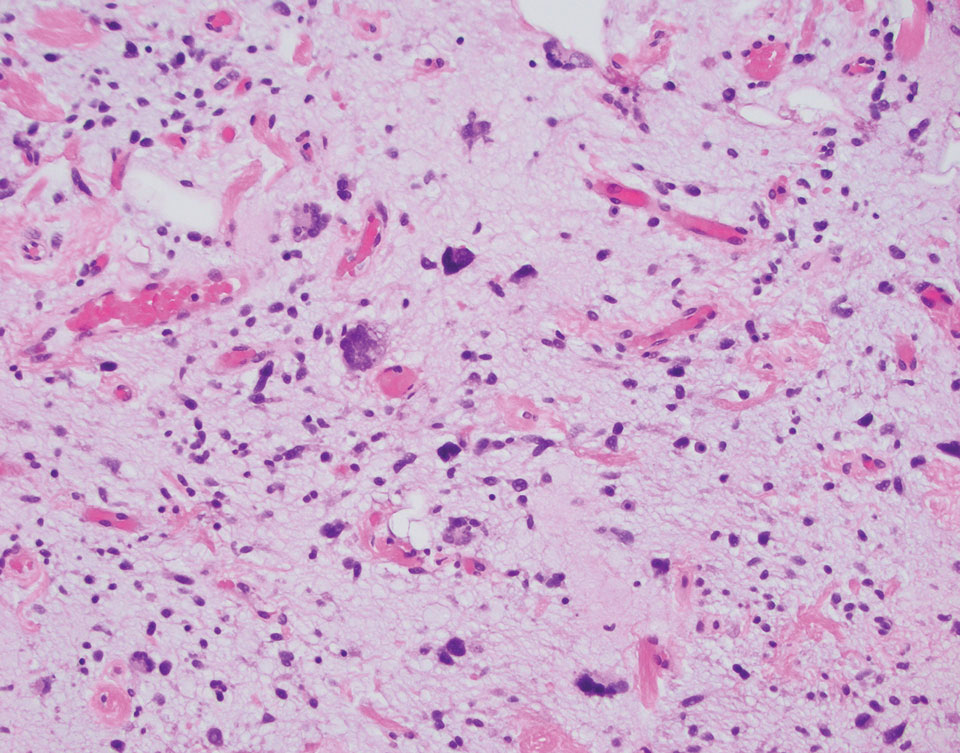

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

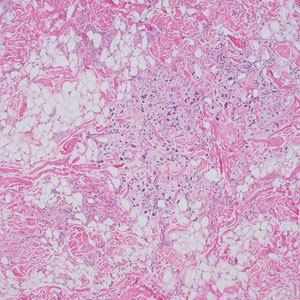

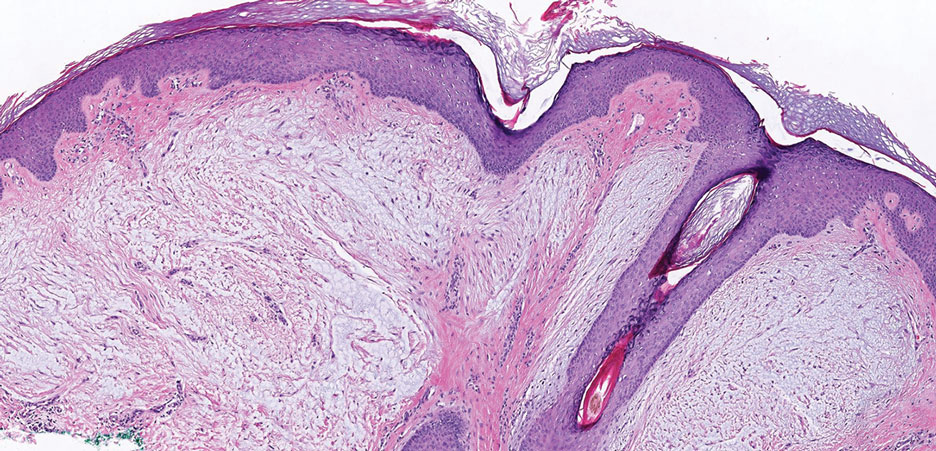

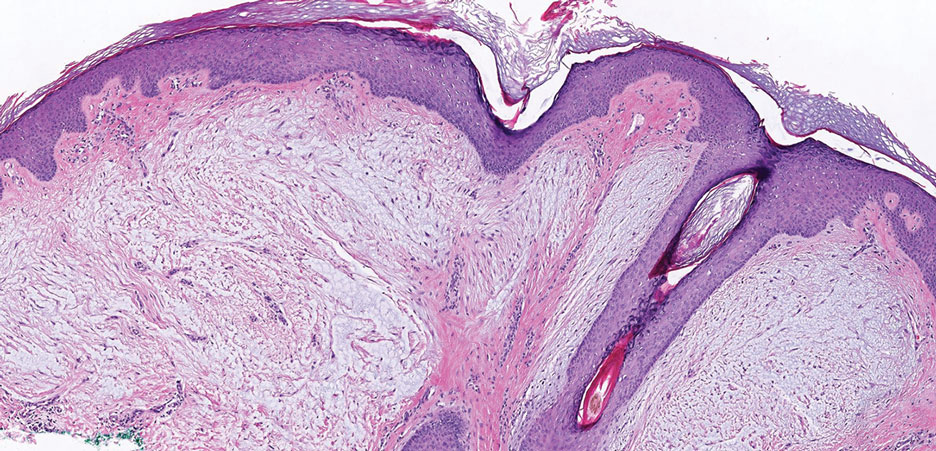

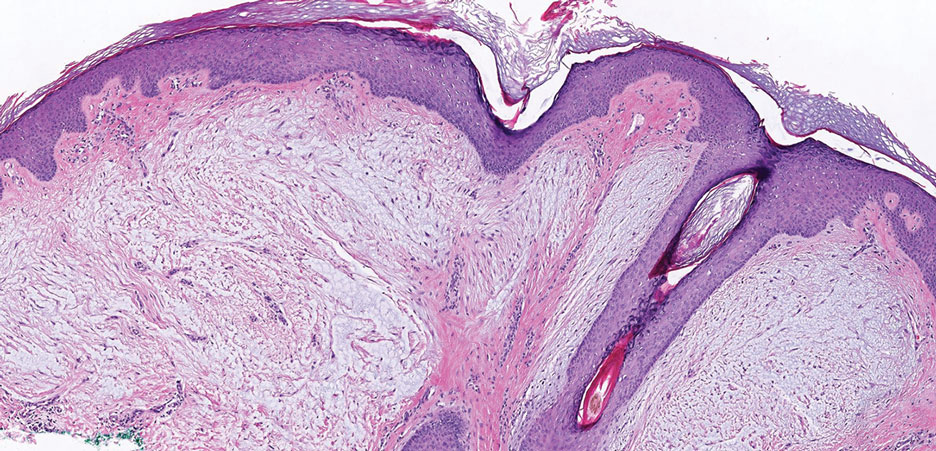

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

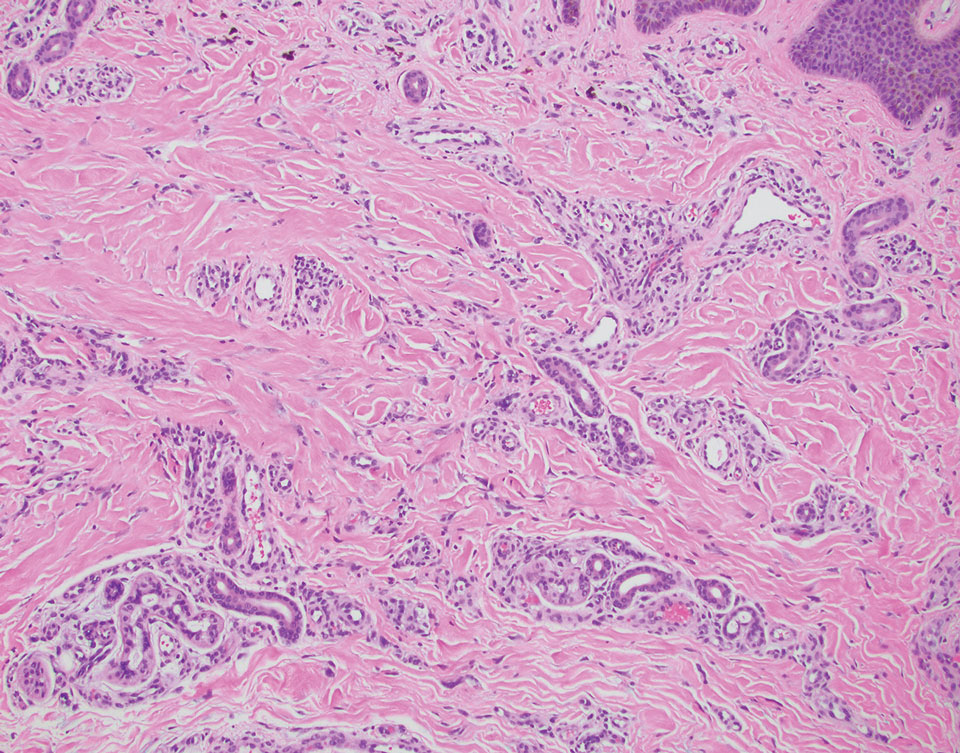

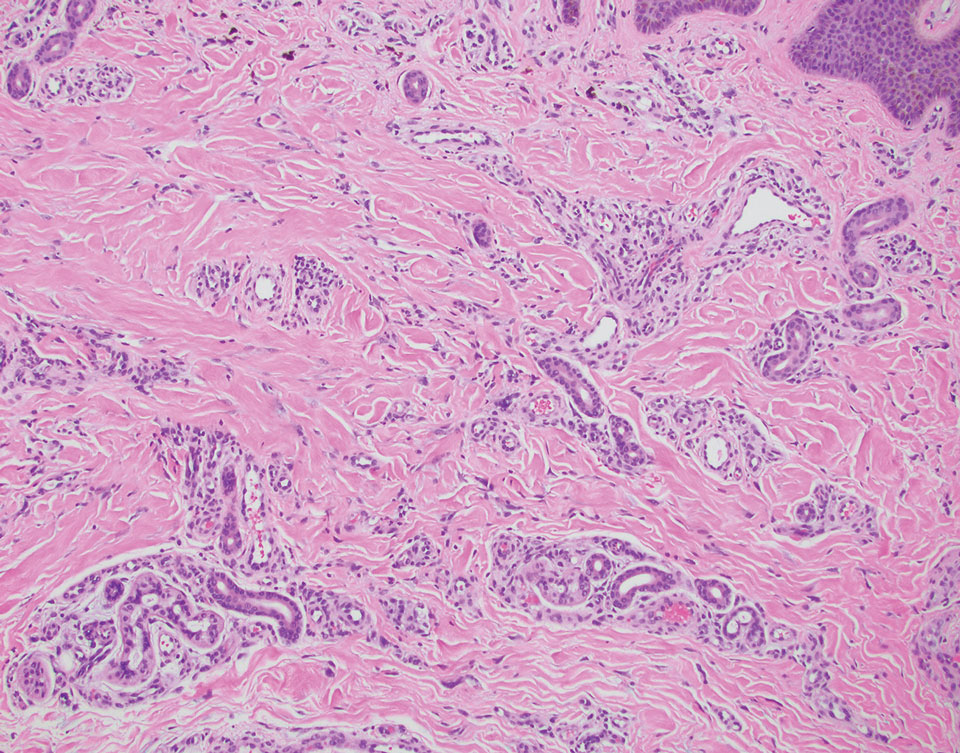

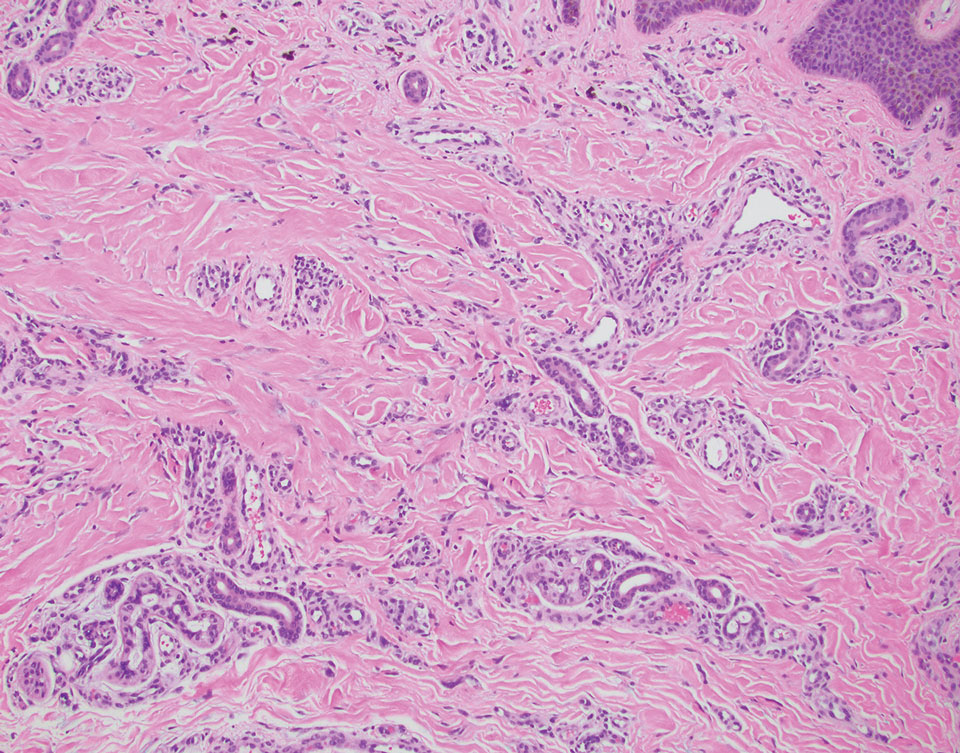

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

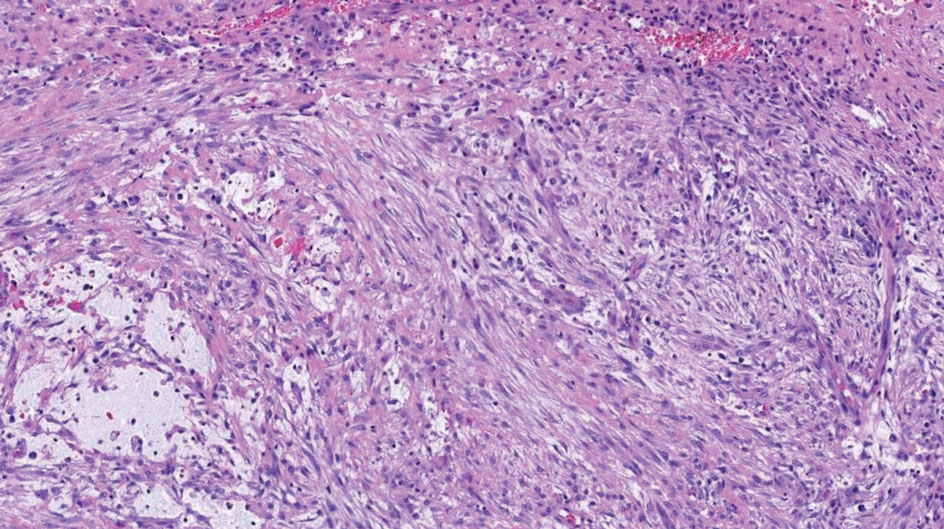

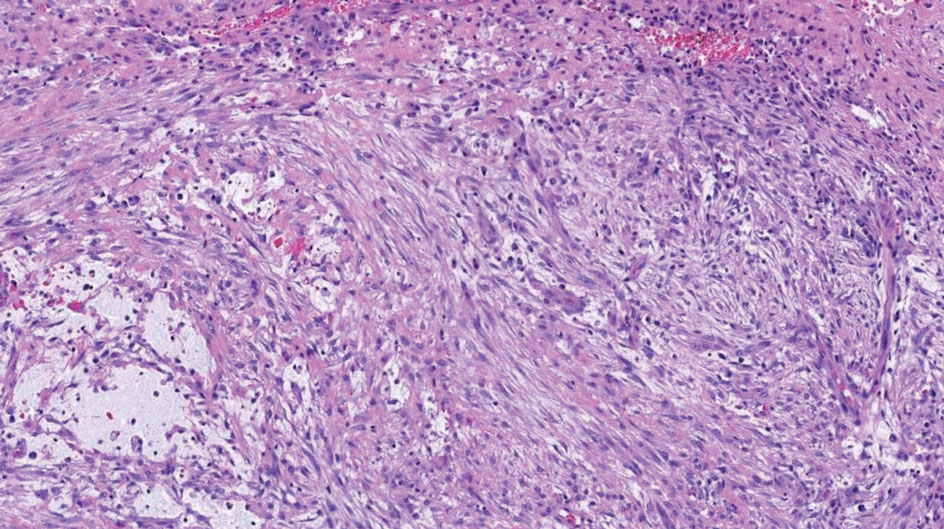

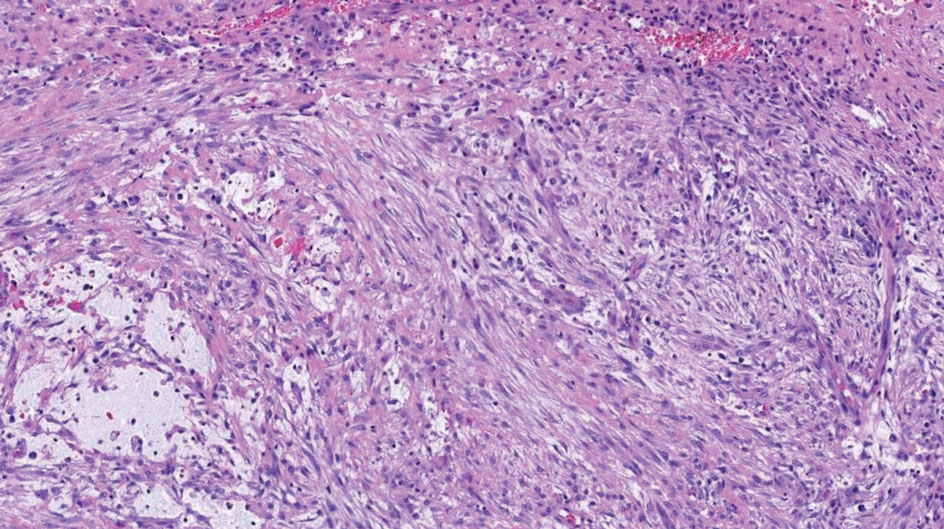

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

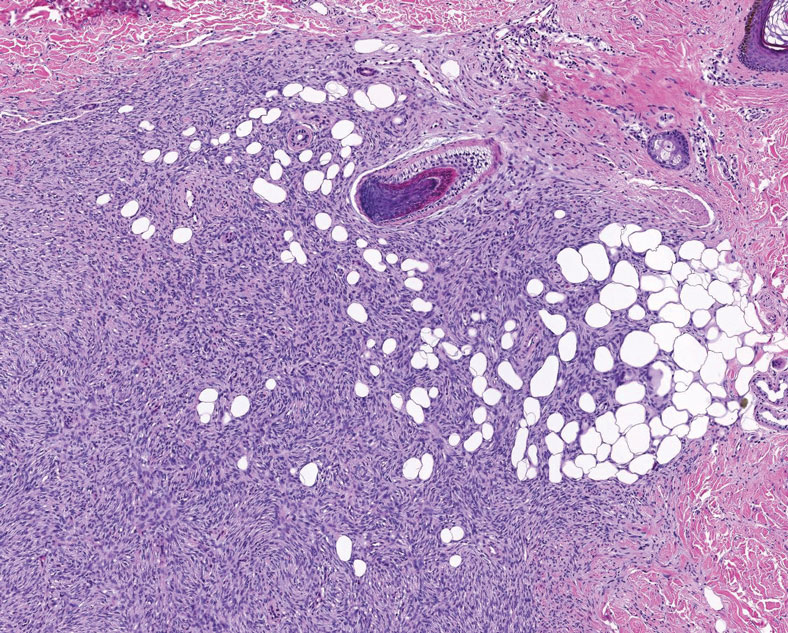

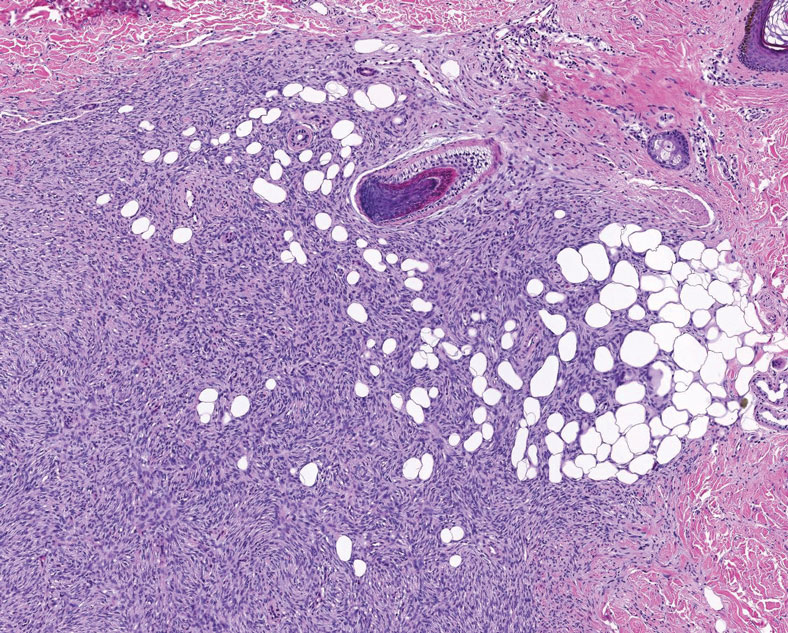

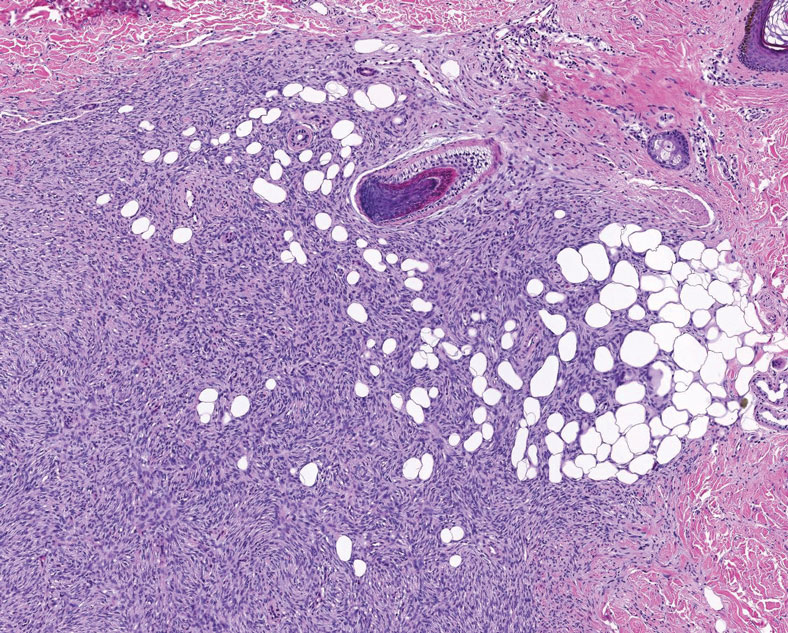

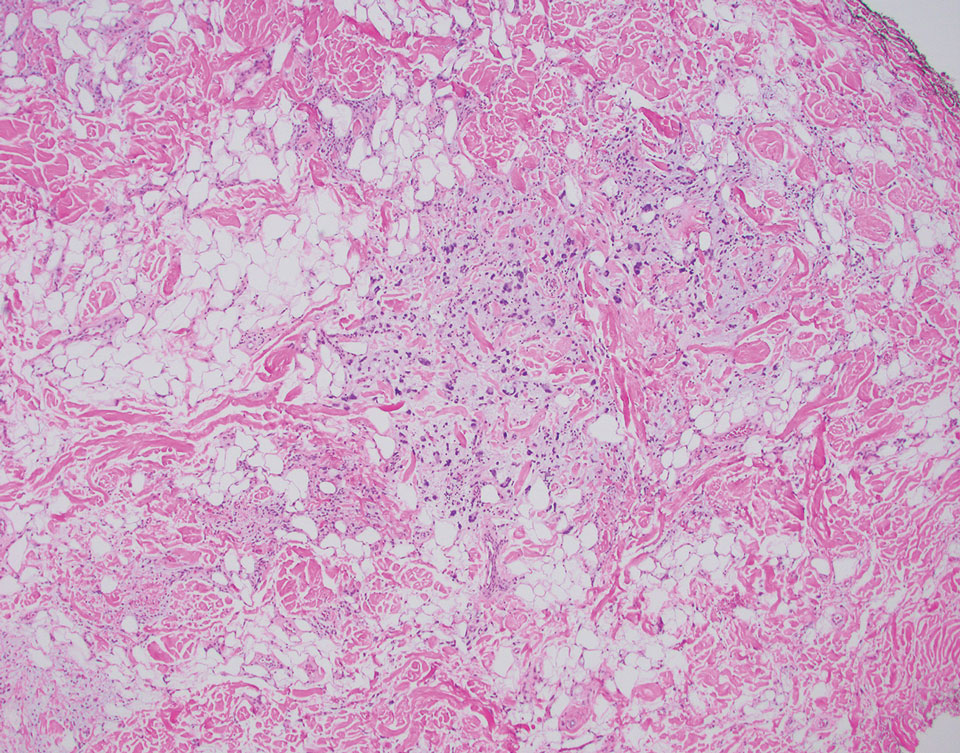

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

The Diagnosis: Pleomorphic Lipoma

Pleomorphic lipoma is a rare, benign, adipocytic neoplasm that presents in the subcutaneous tissues of the upper shoulder, back, or neck. It predominantly affects men aged 50 to 70 years. Most lesions are situated in the subcutaneous tissues; few cases of intramuscular and retroperitoneal tumors have been reported.1 Clinically, pleomorphic lipomas present as painless, well-circumscribed lesions of the subcutaneous tissue that often resemble a lipoma or occasionally may be mistaken for liposarcoma. Histopathologic examination of ordinary lipomas reveals uniform mature adipocytes. However, pleomorphic lipomas consist of a mixture of multinucleated floretlike giant cells, variable-sized adipocytes, and fibrous tissue (ropy collagen bundles) with some myxoid and spindled areas.1,2 The most characteristic histologic feature of pleomorphic lipoma is multinucleated floretlike giant cells. The nuclei of these giant cells appear hyperchromatic, enlarged, and disposed to the periphery of the cell in a circular pattern. Additionally, tumors frequently contain excess mature dense collagen bundles that are strongly refractile in polarized light. Numerous mast cells are present. Atypical lipoblasts and capillary networks commonly are not visible in pleomorphic lipoma.3 The spindle cells express CD34 on immunohistochemistry. Loss of Rb-1 expression is typical.4

Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans is a slow-growing soft tissue sarcoma that commonly begins as a pink or violet plaque on the trunk or upper limbs. Involvement of the head or neck accounts for only 10% to 15% of cases.5 This tumor has low metastatic potential but is highly infiltrative of surrounding tissues. It is associated with a translocation between chromosomes 22 and 17, leading to the fusion of the platelet-derived growth factor subunit β, PDGFB, and collagen type 1α1, COL1A1, genes.5 Clinically, patients often report that the lesion was present for several years prior to presentation with general stability in size and shape. Eventually, untreated lesions progress to become nodules or tumors and may even bleed or ulcerate. Histology reveals a storiform spindle cell proliferation throughout the dermis with infiltration into subcutaneous fat, commonly appearing in a honeycomblike pattern (Figure 1). Numerous histologic variants exist, including myxoid, sclerosing, pigmented (Bednar tumor), myoid, atrophic, or fibrosarcomatous dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans, as well as a giant cell fibroblastoma variant.6 These tumor subtypes can exist independently or in association with one another, creating hybrid lesions that can closely mimic other entities such as pleomorphic lipoma. The spindle cells stain positively for CD34. Treatment of these tumors involves complete surgical excision or Mohs micrographic surgery; however, recurrence is common for tumors involving the head or neck.5

Superficial angiomyxoma is a slow-growing papule that most commonly appears on the trunk, head, or neck in middle-aged adults. Occasionally, patients with Carney complex also can develop lesions on the external ear or breast.7 Histologically, superficial angiomyxoma is a hypocellular tumor characterized by abundant myxoid stroma, thin blood vessels, and small spindled and stellate cells with minimal cytoplasm (Figure 2).8 Superficial angiomyxoma and pleomorphic lipoma present differently on histology; superficial angiomyxoma is not associated with nuclear atypia or pleomorphism, whereas pleomorphic lipoma characteristically contains multinucleated floretlike giant cells and pleomorphism. Frequently, there also is loss of normal PRKAR1A gene expression, which is responsible for protein kinase A regulatory subunit 1-alpha expression.8

Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma is a rare benign proliferation that presents with numerous red-violet asymptomatic papules that commonly appear on the upper and lower extremities of women aged 40 to 70 years. Lesions feature both a fibrohistiocytic and vascular component.9 Histologic examination commonly shows multinucleated cells with angular outlining in the superficial dermis accompanied by fibrosis and ectatic small-caliber vessels (Figure 3). Although both pleomorphic lipoma and multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma have similar-appearing multinucleated giant cells, the latter has a proliferation of narrow vessels in thick collagen bundles and lacks an adipocytic component, which distinguishes it from the former.10 Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma also is characterized by a substantial number of factor XIIIa–positive fibrohistiocytic interstitial cells and vascular hyperplasia.9

Nodular fasciitis is a benign lesion involving the rapid proliferation of myofibroblasts and fibroblasts in the subcutaneous tissue and most commonly is encountered on the extremities or head and neck regions. Many cases appear at sites of prior trauma, especially in patients aged 20 to 40 years. However, in infants and children the lesions typically are found in the head and neck regions.11 Clinically, lesions present as subcutaneous nodules. Histology reveals an infiltrative and poorly circumscribed proliferation of spindled myofibroblasts associated with myxoid stroma and dense collagen depositions. The spindled cells are loosely associated, rendering a tissue culture–like appearance (Figure 4). It also is common to see erythrocyte extravasation adjacent to myxoid stroma.11 Positive stains include vimentin, smooth muscle actin, and CD68, though immunohistochemistry often is not necessary for diagnosis.12 There often is abundant mitotic activity in nodular fasciitis, especially in early lesions, and the differential diagnosis includes sarcoma. Although nodular fasciitis is mitotically active, it does not show atypical mitotic figures. Nodular fasciitis commonly harbors a gene translocation of the MYH9 gene’s promoter region to the USP6 gene’s coding region.13

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

- Sakhadeo U, Mundhe R, DeSouza MA, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma: a gentle giant of pathology. J Cytol. 2015;32:201-203. doi:10.4103 /0970-9371.168904

- Shmookler BM, Enzinger FM. Pleomorphic lipoma: a benign tumor simulating liposarcoma. a clinicopathologic analysis of 48 cases. Cancer. 1981;47:126-133.

- Azzopardi JG, Iocco J, Salm R. Pleomorphic lipoma: a tumour simulating liposarcoma. Histopathology. 1983;7:511-523. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2559.1983.tb02264.x

- Jäger M, Winkelmann R, Eichler K, et al. Pleomorphic lipoma. J Dtsch Dermatol Ges. 2018;16:208-210. doi:10.1111/ddg.13422

- Allen A, Ahn C, Sangüeza OP. Dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans. Dermatol Clin. 2019;37:483-488. doi:10.1016/j.det.2019.05.006

- Socoliuc C, Zurac S, Andrei R, et al. Multiple histological subtypes of dermatofibrosarcoma protuberans occurring in the same tumor. Rom J Intern Med. 2015;53:79-88. doi:10.1515/rjim-2015-0011

- Abarzúa-Araya A, Lallas A, Piana S, et al. Superficial angiomyxoma of the skin. Dermatol Pract Concept. 2016;6:47-49. doi:10.5826 /dpc.0603a09

- Hornick J. Practical Soft Tissue Pathology A Diagnostic Approach. 2nd ed. Elsevier Health Sciences; 2017.

- Rato M, Monteiro AF, Parente J, et al. Case for diagnosis. multinucleated cell angiohistiocytoma. An Bras Dermatol. 2018;93:291-293. doi:10.1590 /abd1806-4841.20186821

- Grgurich E, Quinn K, Oram C, et al. Multinucleate cell angiohistiocytoma: case report and literature review. J Cutan Pathol. 2019;46:59-61. doi:10.1111/cup.13361

- Zuber TJ, Finley JL. Nodular fasciitis. South Med J. 1994;87:842-844. doi:10.1097/00007611-199408000-00020

- Yver CM, Husson MA, Friedman O. Pathology clinic: nodular fasciitis involving the external ear [published online March 18, 2021]. Ear Nose Throat J. doi:10.1177/01455613211001958

- Erickson-Johnson M, Chou M, Evers B, et al. Nodular fasciitis: a novel model of transient neoplasia induced by MYH9-USP6 gene fusion. Lab Invest. 2011;91:1427-1433. https://doi.org/10.1038 /labinvest.2011.118

An otherwise healthy 56-year-old man with a family history of lymphoma presented with a raised lesion on the postauricular neck. He first noticed the nodule 3 months prior and was unsure if it was still getting larger. It was predominantly asymptomatic. Physical examination revealed a 1.5×1.5-cm, mobile, subcutaneous nodule. An incisional biopsy was performed and submitted for histologic evaluation.

Disparities in Melanoma Demographics, Tumor Stage, and Metastases in Hispanic and Latino Patients: A Retrospective Study

To the Editor:

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer with a high rate of metastasis and poor prognosis.1 Historically, Hispanic and/or Latino patients have presented with more advanced-stage melanomas and have lower survival rates compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients.2 In this study, we evaluated recent data from the last decade to investigate if disparities in melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and risk for metastases continue to exist in the Hispanic and/or Latino population.

We conducted a retrospective review of melanoma patients at 2 major medical centers in Los Angeles, California—Keck Medicine of USC and Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center—from January 2010 to January 2020. The data collected from electronic medical records included age at melanoma diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance type, Breslow depth of lesion, presence of ulceration, and presence of lymph node or distant metastases. Melanoma tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Patients who self-reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino were designated to this group regardless of their reported race. Those patients who reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino and reported their race as White were designated as non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Southern California (Los Angeles). Data analysis was performed using the Pearson χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test. Statistical significance was determined at P<.05.

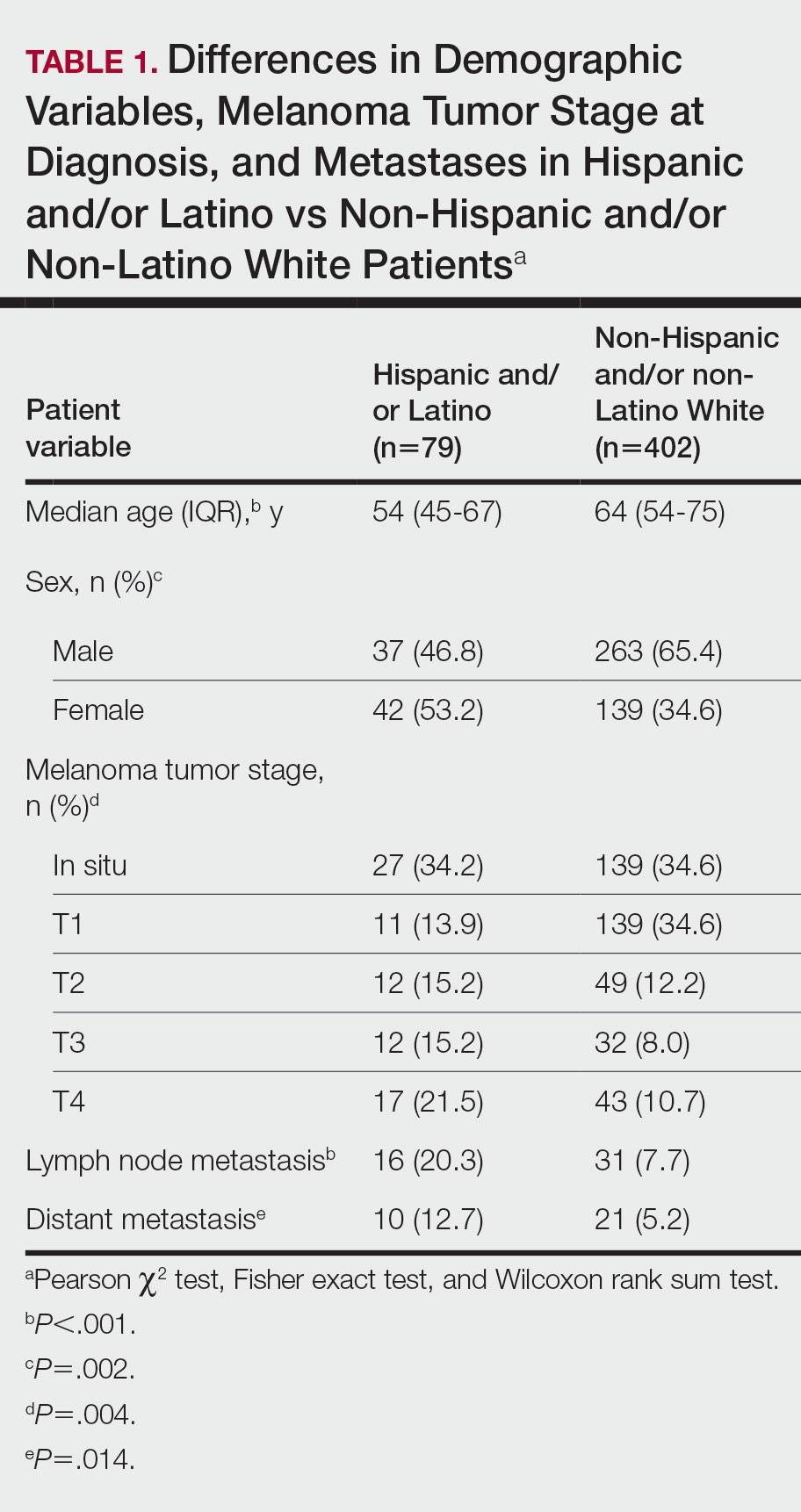

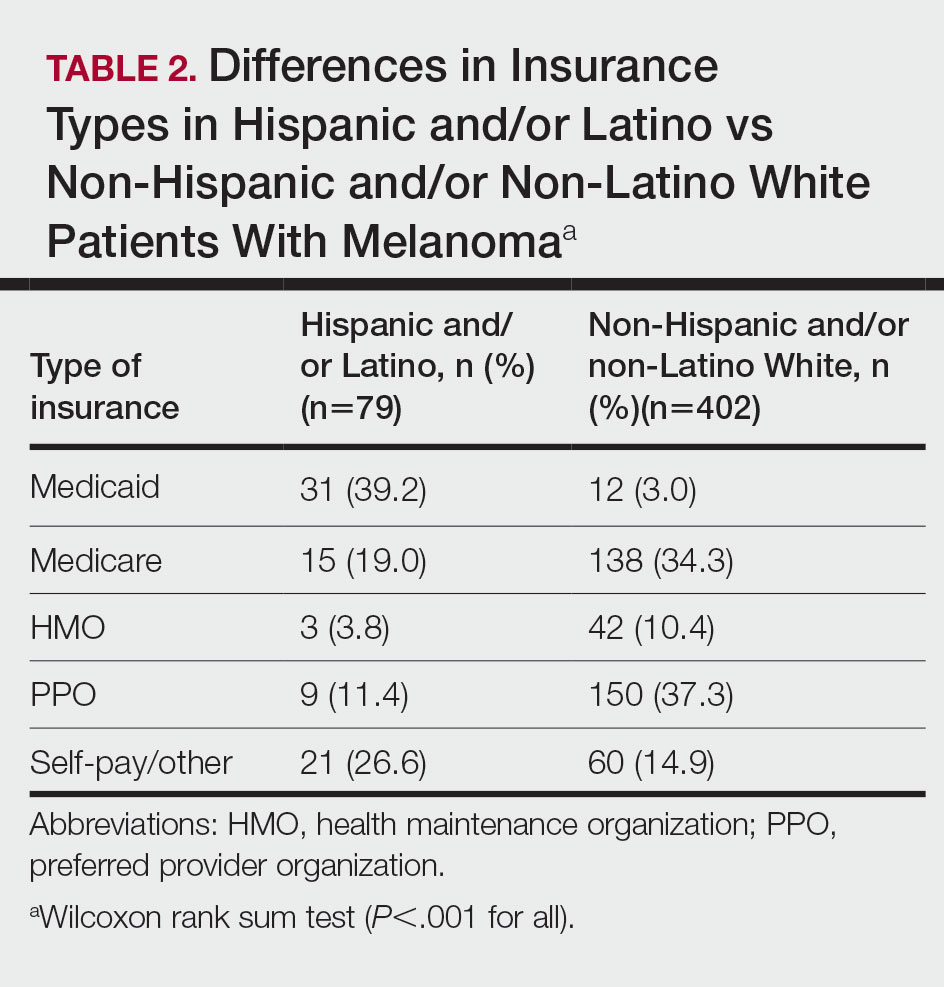

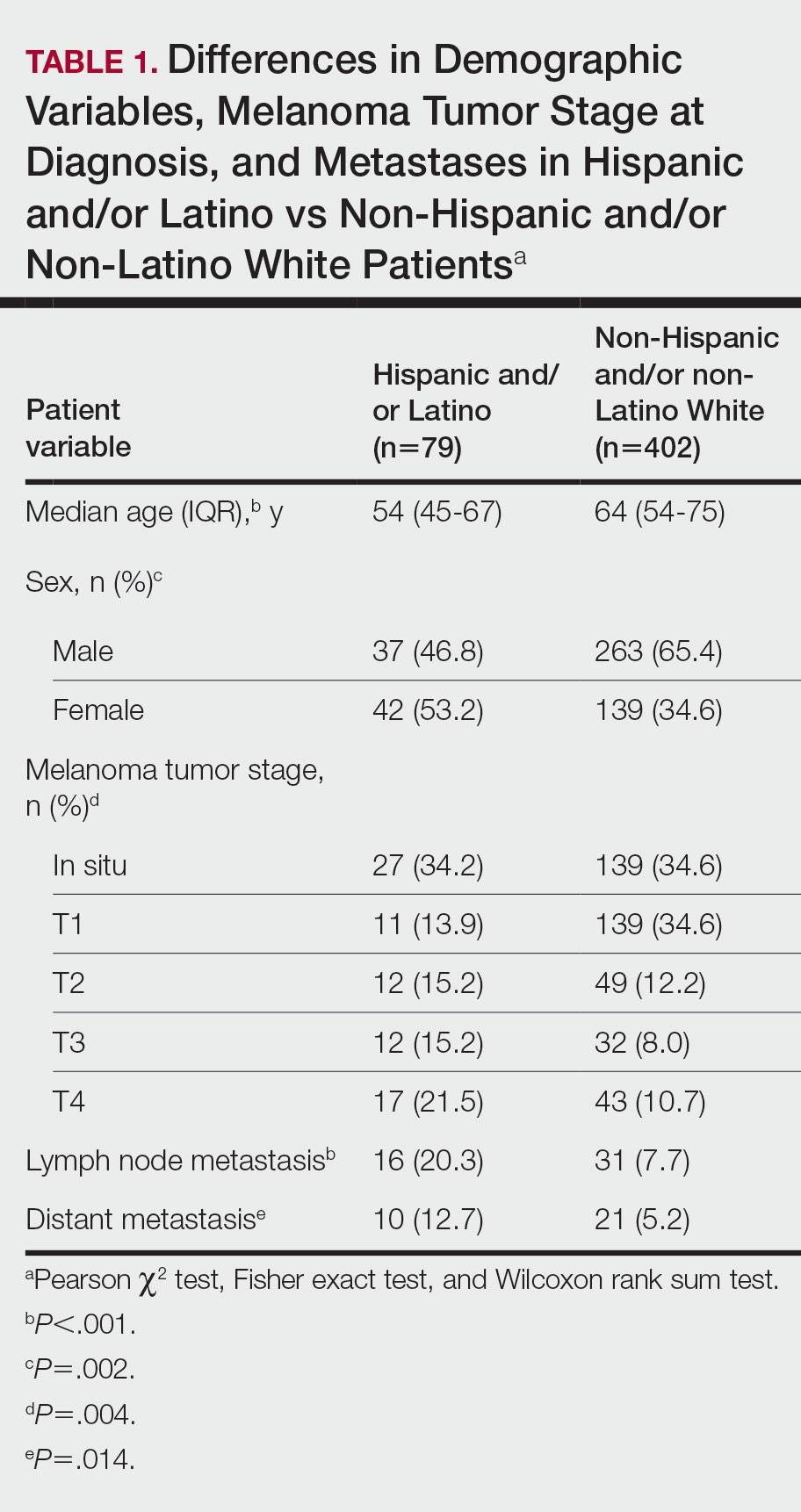

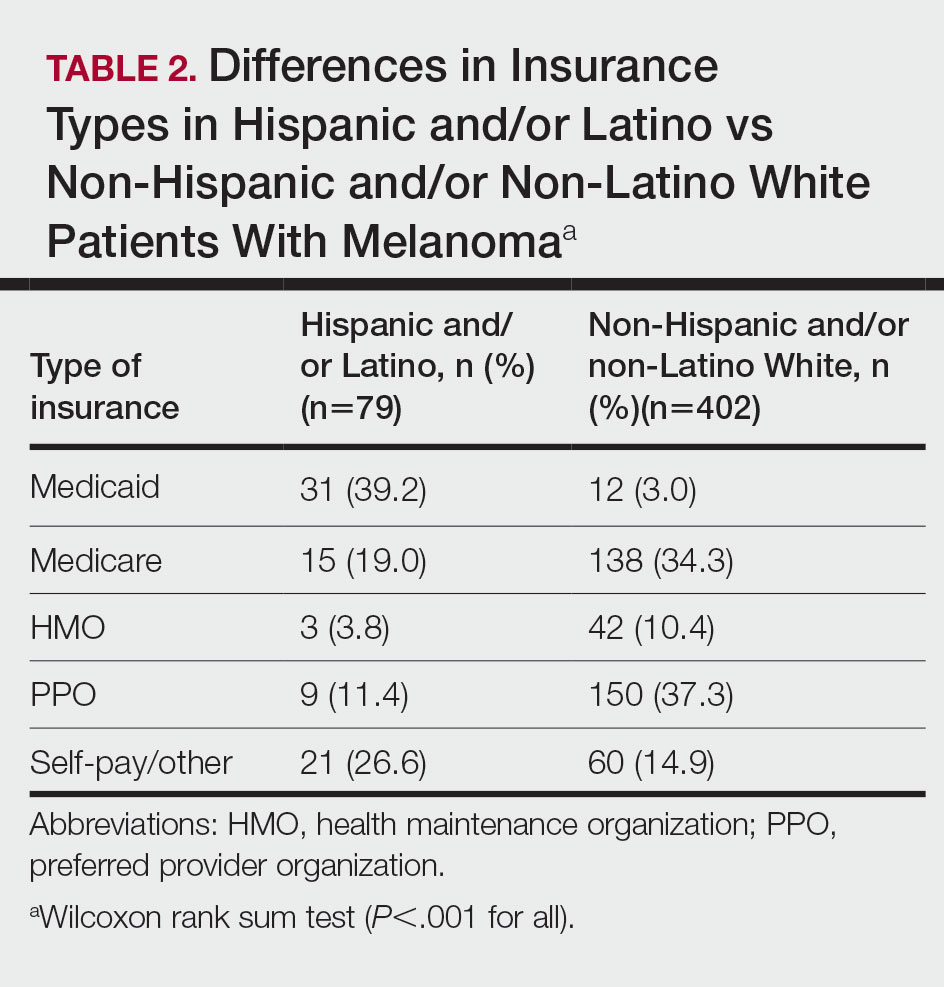

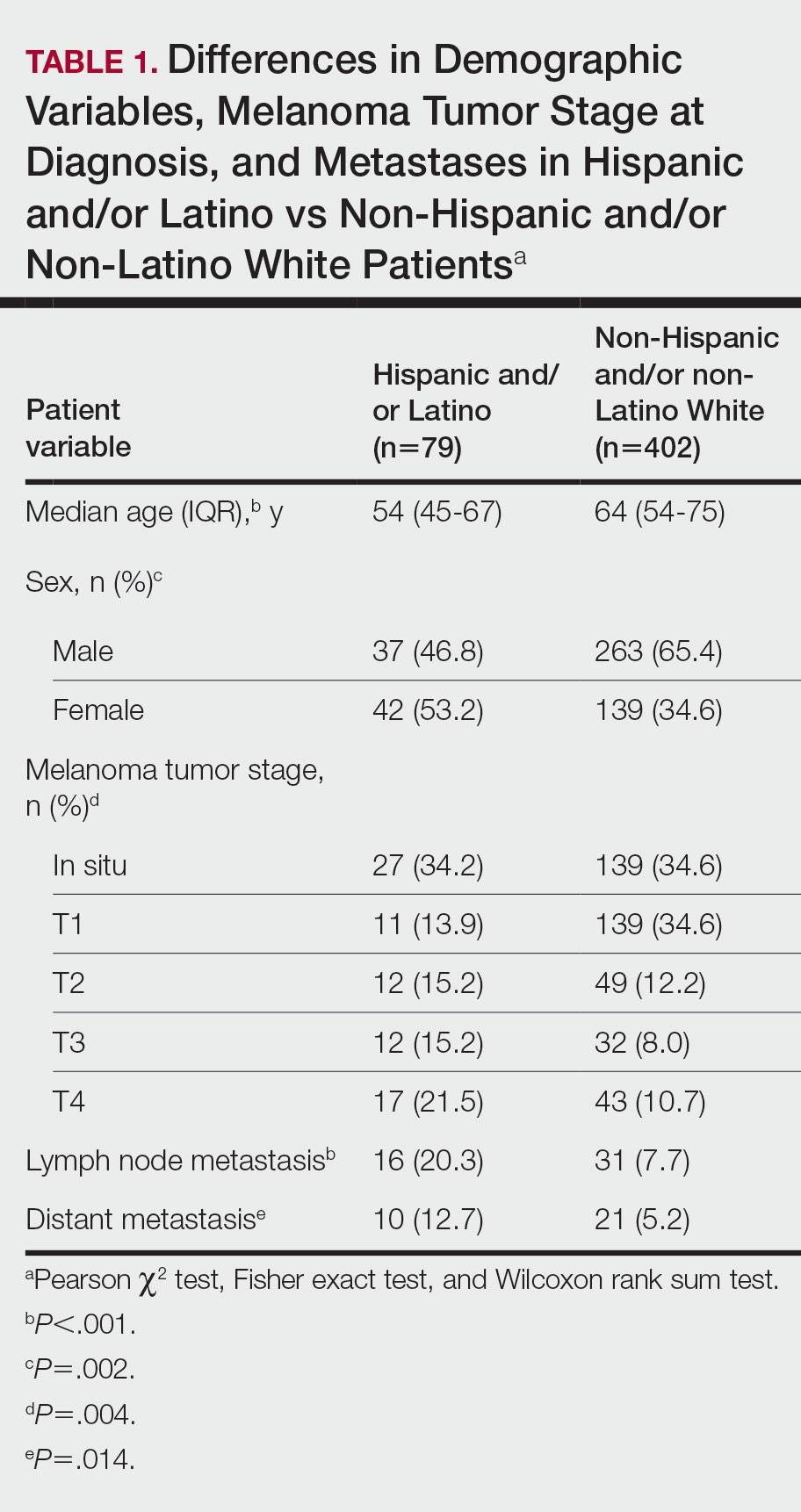

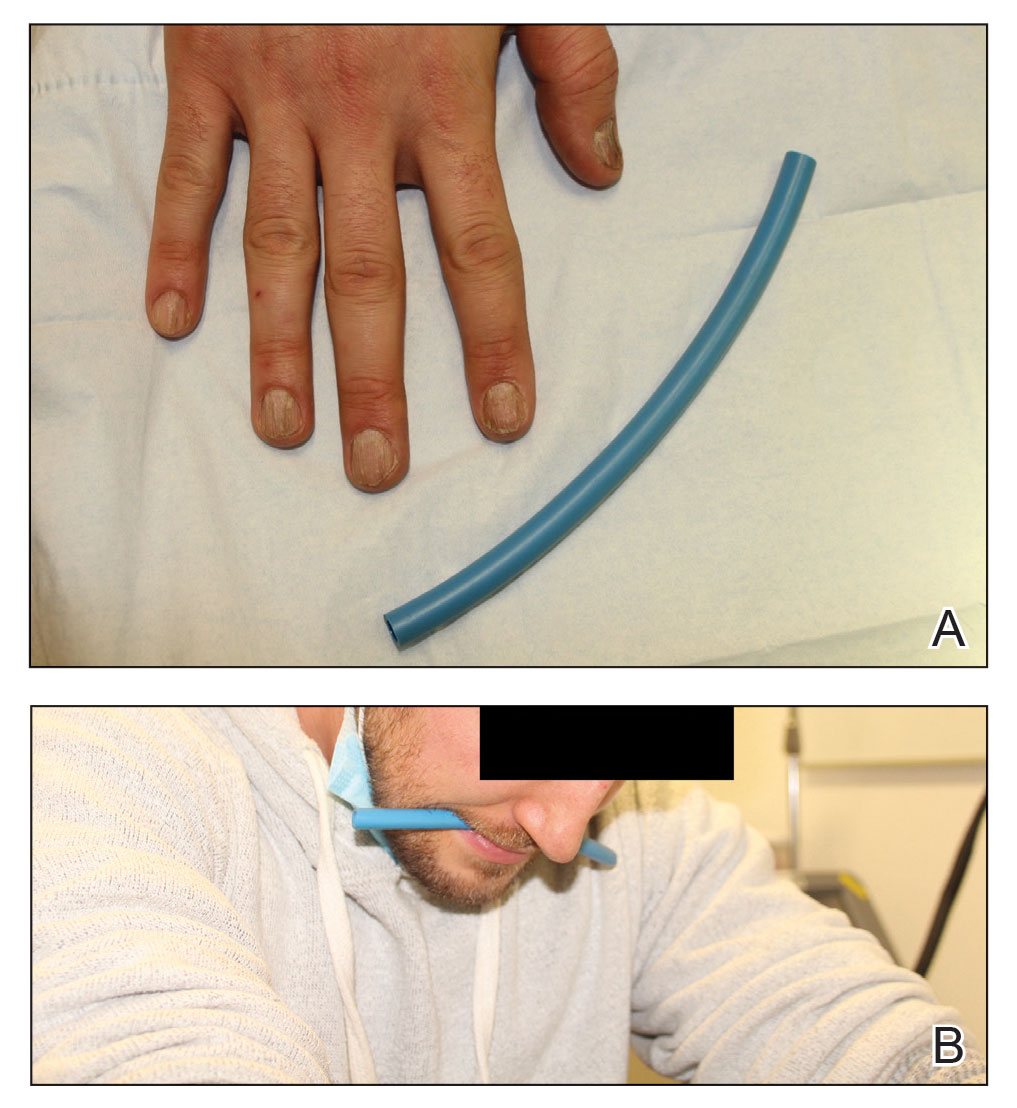

The final cohort of patients included 79 Hispanic and/or Latino patients and 402 non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. The median age for the Hispanic and/or Latino group was 54 years and 64 years for the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (P<.001). There was a greater percentage of females in the Hispanic and/or Latino group compared with the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (53.2% vs 34.6%)(P=.002). Hispanic and/or Latino patients presented with more advanced tumor stage melanomas (T3: 15.2%; T4: 21.5%) compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (T3: 8.0%; T4: 10.7%)(P=.004). Furthermore, Hispanic and/or Latino patients had higher rates of lymph node metastases compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (20.3% vs 7.7% [P<.001]) and higher rates of distant metastases (12.7% vs 5.2% [P=.014])(Table 1). The majority of Hispanic and/or Latino patients had Medicaid (39.2%), while most non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients had a preferred provider organization insurance plan (37.3%) or Medicare (34.3%)(P<.001)(Table 2).

This retrospective study analyzing nearly 10 years of recent melanoma data found that disparities in melanoma diagnosis and treatment continue to exist among Hispanic and/or Latino patients. Compared to non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, Hispanic and/or Latino patients were diagnosed with melanoma at a younger age and the proportion of females with melanoma was higher. Cormier et al2 also reported that Hispanic patients were younger at melanoma diagnosis, and females represented a larger majority of patients in the Hispanic population compared with the White population. Hispanic and/or Latino patients in our study had more advanced melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and a higher risk of lymph node and distant metastases, similar to findings reported by Koblinksi et al.3

Our retrospective cohort study demonstrated that the demographics of Hispanic and/or Latino patients with melanoma differ from non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, specifically with a greater proportion of younger and female patients in the Hispanic and/or Latino population. We also found that Hispanic and/or Latino patients continue to experience worse melanoma outcomes compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. Further studies are needed to investigate the etiologies behind these health care disparities and potential interventions to address them. In addition, there needs to be increased awareness of the risk for melanoma in Hispanic and/or Latino patients among both health care providers and patients.

Limitations of this study included a smaller sample size of patients from one geographic region. The retrospective design of this study also increased the risk for selection bias, as some of the patients may have had incomplete records or were lost to follow-up. Therefore, the study cohort may not be representative of the general population. Additionally, patients’ skin types could not be determined using standardized tools such as the Fitzpatrick scale, thus we could not assess how patient skin type may have affected melanoma outcomes.

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Koblinski JE, Maykowski P, Zeitouni NC. Disparities in melanoma stage at diagnosis in Arizona: a 10-year Arizona Cancer Registry study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1776-1779. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.045

To the Editor:

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer with a high rate of metastasis and poor prognosis.1 Historically, Hispanic and/or Latino patients have presented with more advanced-stage melanomas and have lower survival rates compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients.2 In this study, we evaluated recent data from the last decade to investigate if disparities in melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and risk for metastases continue to exist in the Hispanic and/or Latino population.

We conducted a retrospective review of melanoma patients at 2 major medical centers in Los Angeles, California—Keck Medicine of USC and Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center—from January 2010 to January 2020. The data collected from electronic medical records included age at melanoma diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance type, Breslow depth of lesion, presence of ulceration, and presence of lymph node or distant metastases. Melanoma tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Patients who self-reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino were designated to this group regardless of their reported race. Those patients who reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino and reported their race as White were designated as non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Southern California (Los Angeles). Data analysis was performed using the Pearson χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test. Statistical significance was determined at P<.05.

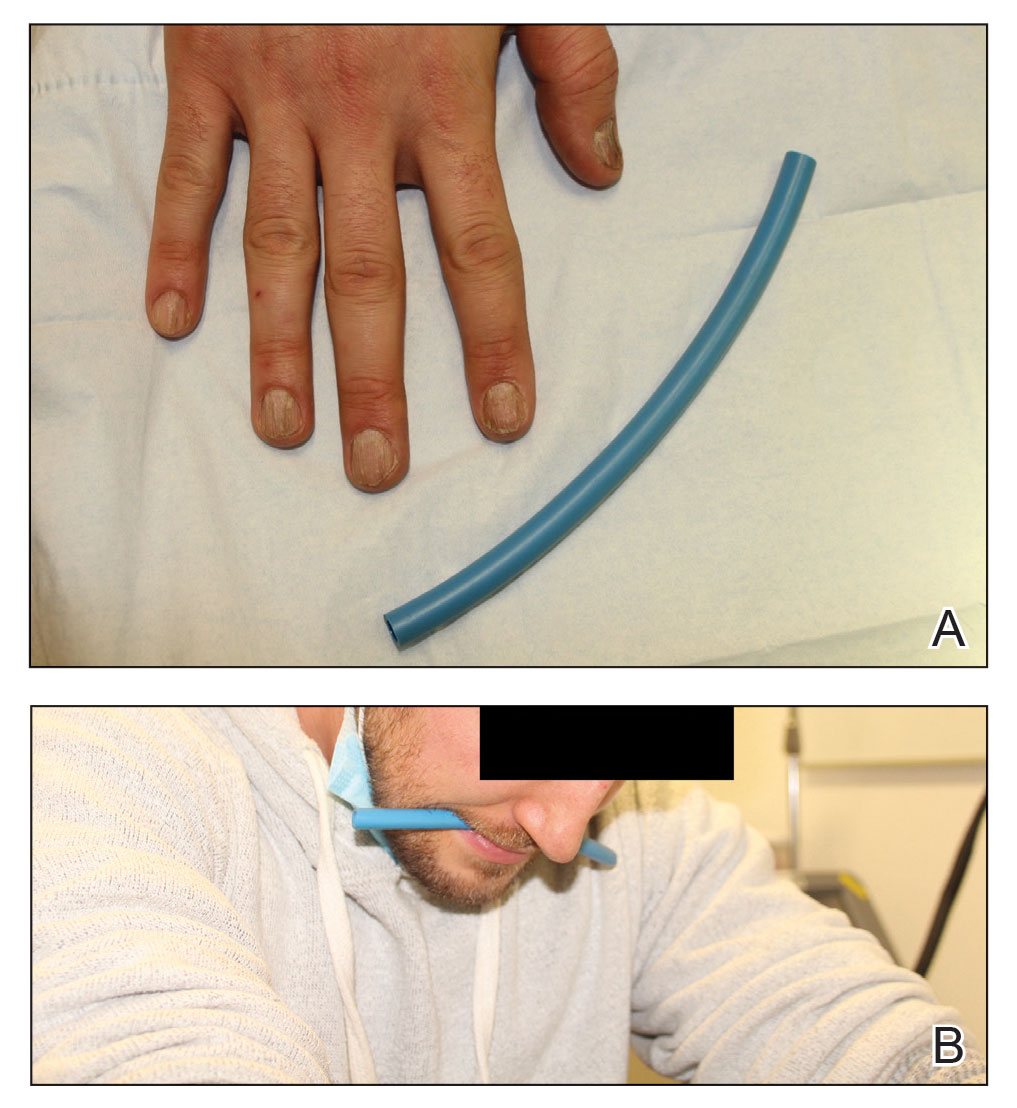

The final cohort of patients included 79 Hispanic and/or Latino patients and 402 non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. The median age for the Hispanic and/or Latino group was 54 years and 64 years for the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (P<.001). There was a greater percentage of females in the Hispanic and/or Latino group compared with the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (53.2% vs 34.6%)(P=.002). Hispanic and/or Latino patients presented with more advanced tumor stage melanomas (T3: 15.2%; T4: 21.5%) compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (T3: 8.0%; T4: 10.7%)(P=.004). Furthermore, Hispanic and/or Latino patients had higher rates of lymph node metastases compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (20.3% vs 7.7% [P<.001]) and higher rates of distant metastases (12.7% vs 5.2% [P=.014])(Table 1). The majority of Hispanic and/or Latino patients had Medicaid (39.2%), while most non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients had a preferred provider organization insurance plan (37.3%) or Medicare (34.3%)(P<.001)(Table 2).

This retrospective study analyzing nearly 10 years of recent melanoma data found that disparities in melanoma diagnosis and treatment continue to exist among Hispanic and/or Latino patients. Compared to non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, Hispanic and/or Latino patients were diagnosed with melanoma at a younger age and the proportion of females with melanoma was higher. Cormier et al2 also reported that Hispanic patients were younger at melanoma diagnosis, and females represented a larger majority of patients in the Hispanic population compared with the White population. Hispanic and/or Latino patients in our study had more advanced melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and a higher risk of lymph node and distant metastases, similar to findings reported by Koblinksi et al.3

Our retrospective cohort study demonstrated that the demographics of Hispanic and/or Latino patients with melanoma differ from non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, specifically with a greater proportion of younger and female patients in the Hispanic and/or Latino population. We also found that Hispanic and/or Latino patients continue to experience worse melanoma outcomes compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. Further studies are needed to investigate the etiologies behind these health care disparities and potential interventions to address them. In addition, there needs to be increased awareness of the risk for melanoma in Hispanic and/or Latino patients among both health care providers and patients.

Limitations of this study included a smaller sample size of patients from one geographic region. The retrospective design of this study also increased the risk for selection bias, as some of the patients may have had incomplete records or were lost to follow-up. Therefore, the study cohort may not be representative of the general population. Additionally, patients’ skin types could not be determined using standardized tools such as the Fitzpatrick scale, thus we could not assess how patient skin type may have affected melanoma outcomes.

To the Editor:

Melanoma is an aggressive form of skin cancer with a high rate of metastasis and poor prognosis.1 Historically, Hispanic and/or Latino patients have presented with more advanced-stage melanomas and have lower survival rates compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients.2 In this study, we evaluated recent data from the last decade to investigate if disparities in melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and risk for metastases continue to exist in the Hispanic and/or Latino population.

We conducted a retrospective review of melanoma patients at 2 major medical centers in Los Angeles, California—Keck Medicine of USC and Los Angeles County-USC Medical Center—from January 2010 to January 2020. The data collected from electronic medical records included age at melanoma diagnosis, sex, race and ethnicity, insurance type, Breslow depth of lesion, presence of ulceration, and presence of lymph node or distant metastases. Melanoma tumor stage was determined using the American Joint Committee on Cancer classification. Patients who self-reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino were designated to this group regardless of their reported race. Those patients who reported their ethnicity as not Hispanic and/or Latino and reported their race as White were designated as non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White. This study was approved by the institutional review board of the University of Southern California (Los Angeles). Data analysis was performed using the Pearson χ2 test, Fisher exact test, and Wilcoxon rank sum test. Statistical significance was determined at P<.05.

The final cohort of patients included 79 Hispanic and/or Latino patients and 402 non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. The median age for the Hispanic and/or Latino group was 54 years and 64 years for the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (P<.001). There was a greater percentage of females in the Hispanic and/or Latino group compared with the non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White group (53.2% vs 34.6%)(P=.002). Hispanic and/or Latino patients presented with more advanced tumor stage melanomas (T3: 15.2%; T4: 21.5%) compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (T3: 8.0%; T4: 10.7%)(P=.004). Furthermore, Hispanic and/or Latino patients had higher rates of lymph node metastases compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients (20.3% vs 7.7% [P<.001]) and higher rates of distant metastases (12.7% vs 5.2% [P=.014])(Table 1). The majority of Hispanic and/or Latino patients had Medicaid (39.2%), while most non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients had a preferred provider organization insurance plan (37.3%) or Medicare (34.3%)(P<.001)(Table 2).

This retrospective study analyzing nearly 10 years of recent melanoma data found that disparities in melanoma diagnosis and treatment continue to exist among Hispanic and/or Latino patients. Compared to non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, Hispanic and/or Latino patients were diagnosed with melanoma at a younger age and the proportion of females with melanoma was higher. Cormier et al2 also reported that Hispanic patients were younger at melanoma diagnosis, and females represented a larger majority of patients in the Hispanic population compared with the White population. Hispanic and/or Latino patients in our study had more advanced melanoma tumor stage at diagnosis and a higher risk of lymph node and distant metastases, similar to findings reported by Koblinksi et al.3

Our retrospective cohort study demonstrated that the demographics of Hispanic and/or Latino patients with melanoma differ from non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients, specifically with a greater proportion of younger and female patients in the Hispanic and/or Latino population. We also found that Hispanic and/or Latino patients continue to experience worse melanoma outcomes compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients. Further studies are needed to investigate the etiologies behind these health care disparities and potential interventions to address them. In addition, there needs to be increased awareness of the risk for melanoma in Hispanic and/or Latino patients among both health care providers and patients.

Limitations of this study included a smaller sample size of patients from one geographic region. The retrospective design of this study also increased the risk for selection bias, as some of the patients may have had incomplete records or were lost to follow-up. Therefore, the study cohort may not be representative of the general population. Additionally, patients’ skin types could not be determined using standardized tools such as the Fitzpatrick scale, thus we could not assess how patient skin type may have affected melanoma outcomes.

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Koblinski JE, Maykowski P, Zeitouni NC. Disparities in melanoma stage at diagnosis in Arizona: a 10-year Arizona Cancer Registry study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1776-1779. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.045

- Aggarwal P, Knabel P, Fleischer AB. United States burden of melanoma and non-melanoma skin cancer from 1990 to 2019. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;85:388-395. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.03.109

- Cormier JN, Xing Y, Ding M, et al. Ethnic differences among patients with cutaneous melanoma. Arch Intern Med. 2006;166:1907. doi:10.1001/archinte.166.17.1907

- Koblinski JE, Maykowski P, Zeitouni NC. Disparities in melanoma stage at diagnosis in Arizona: a 10-year Arizona Cancer Registry study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:1776-1779. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2021.02.045

Practice Points

- Hispanic and/or Latino patients often present with more advanced-stage melanomas and have decreased survival rates compared with non-Hispanic and/or non-Latino White patients.

- More education and awareness on the risk for melanoma as well as sun-protective behaviors in the Hispanic and/or Latino population is needed among both health care providers and patients to prevent diagnosis of melanoma in later stages and improve outcomes.

Botanical Briefs: Handling the Heat From Capsicum Peppers

Cutaneous Manifestations

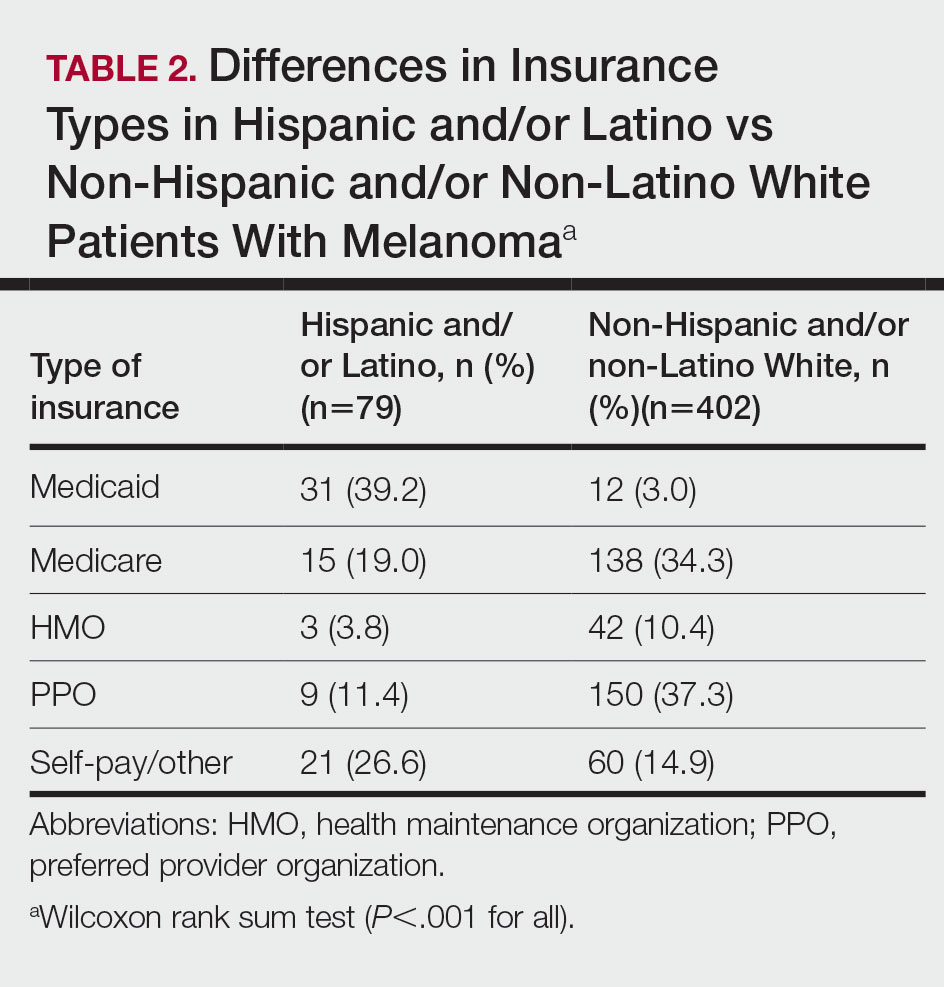

Capsicum peppers are used worldwide in preparing spicy dishes. Their active ingredient—capsaicin—is used as a topical medicine to treat localized pain. Capsicum peppers can cause irritant contact dermatitis with symptoms of erythema, cutaneous burning, and itch.1

Irritant contact dermatitis is a common occupational skin disorder. Many cooks have experienced the sting of a chili pepper after contact with the hands or eyes. Cases of chronic exposure to Capsicum peppers with persistent burning and pain have been called Hunan hand syndrome.2 Capsicum peppers also have induced allergic contact dermatitis in a food production worker.3

Capsicum peppers also are used in pepper spray, tear gas, and animal repellents because of their stinging properties. These agents usually cause cutaneous tingling and burning that soon resolves; however, a review of 31 studies showed that crowd-control methods with Capsicum-containing tear gas and pepper spray can cause moderate to severe skin damage such as a persistent skin rash or erythema, or even first-, second-, or third-degree burns.4

Topical application of capsaicin isolate is meant to cause burning and deplete local neuropeptides, with a cutaneous reaction that ranges from mild to intolerable.5,6 Capsaicin also is found in other products. In one published case report, a 3-year-old boy broke out in facial urticaria when his mother kissed him on the cheek after she applied lip plumper containing capsaicin to her lips.7 Dermatologists should consider capsaicin an active ingredient that can irritate the skin in the garden, in the kitchen, and in topical products.

Obtaining Relief

Capsaicin-induced dermatitis can be relieved by washing the area with soap, detergent, baking soda, or oily compounds that act as solvents for the nonpolar capsaicin.8 Application of ice water or a high-potency topical steroid also may help. If the reaction is severe and persistent, a continuous stellate ganglion block may alleviate the pain of capsaicin-induced contact dermatitis.9

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The Capsicum genus includes chili peppers, paprika, and red peppers. Capsicum peppers are native to tropical regions of the Americas (Figure). The use of Capsicum peppers in food can be traced to Indigenous peoples of Mexico as early as 7000

Capsicum belongs to the family Solanaceae, which includes tobacco, tomatoes, potatoes, and nightshade plants. There are many varieties of peppers in the Capsicum genus, with 5 domesticated species: Capsicum annuum, Capsicum baccatum, Capsicum chinense, Capsicum frutescens, and Capsicum pubescens. These include bell, poblano, cayenne, tabasco, habanero, and ají peppers, among others. Capsicum species grow as a shrub with flowers that rotate to stellate corollas and rounded berries of different sizes and colors.12 Capsaicin and other alkaloids are concentrated in the fruit; therefore, Capsicum dermatitis is most commonly induced by contact with the flesh of peppers.

Irritant Chemicals

Capsaicin (8-methyl-6-nonanoyl vanillylamide) is a nonpolar phenol, which is why washing skin that has come in contact with capsaicin with water or vinegar alone is insufficient to solubilize it.13 Capsaicin binds to the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a calcium channel on neurons that opens in response to heat. When bound, the channel opens at a lower temperature threshold and depolarizes nerve endings, leading to vasodilation and activation of sensory nerves.14 Substance P is released and the individual experiences a painful burning sensation. When purified capsaicin is frequently applied at an appropriate dose, synthesis of substance P is diminished, resulting in reduced local pain overall.15

Capsaicin does not affect neurons without TRPV1, and administration of capsaicin is not painful if given with anesthesia. An inappropriately high dose of capsaicin destroys cells in the epidermal barrier, resulting in water loss and inducing release of vasoactive peptides and inflammatory cytokines.1 Careful handling of Capsicum peppers and capsaicin products can reduce the risk for irritation.

Medicinal Use

On-/Off-Label and Potential Uses—Capsaicin is US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in arthritis and musculoskeletal pain. It also is used to treat diabetic neuropathy,5 postherpetic neuralgia,6 psoriasis,16 and other conditions. Studies have shown that capsaicin might be useful in treating trigeminal neuralgia,17 fibromyalgia,18 migraines,14 cluster headaches,9 and HIV-associated distal sensory neuropathy.5

Delivery of Capsaicin—Capsaicin preferentially acts on C-fibers, which transmit dull, aching, chronic pain.19 The compound is available as a cream, lotion, and large bandage (for the lower back), as well as low- and high-dose patches. Capsaicin creams, lotions, and the low-dose patch are uncomfortable and must be applied for 4 to 6 weeks to take effect, which may impact patient adherence. The high-dose patch, which requires administration under local anesthesia by a health care worker, brings pain relief with a single use and improves adherence.11 Synthetic TRPV1-agonist injectables based on capsaicin have undergone clinical trials for localized pain (eg, postoperative musculoskeletal pain); many patients experience pain relief, though benefit fades over weeks to months.20,21

Use in Traditional Medicine—Capsicum peppers have been used to aid digestion and promote healing in gastrointestinal conditions, such as dyspepsia.22 The peppers are a source of important vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A, C, and E; many of the B complex vitamins; and magnesium, calcium, and iron.23

Use as Cancer Therapy—Studies of the use of capsaicin in treating cancer have produced controversial results. In cell and animal models, capsaicin induces apoptosis through downregulation of the Bcl-2 protein; upregulation of oxidative stress, tribbles-related protein 3 (TRIB3), and caspase-3; and other pathways.19,24-26 On the other hand, consumption of Capsicum peppers has been associated with cancer of the stomach and gallbladder.27 Capsaicin might have anticarcinogenic properties, but its mechanism of action varies, depending on variables not fully understood.

Final Thoughts

Capsaicin is a neuropeptide-active compound found in Capsicum peppers that has many promising applications for use. However, dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of a skin reaction to this compound from handling peppers and using topical medicines. Exposure to capsaicin can cause irritant contact dermatitis that may require clinical care.

- Otang WM, Grierson DS, Afolayan AJ. A survey of plants responsible for causing irritant contact dermatitis in the Amathole district, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:274-284. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.002

- Weinberg RB. Hunan hand. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1020.

- Lambrecht C, Goossens A. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by capsicum. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:252-253. doi:10.1111/cod.12345

- Haar RJ, Iacopino V, Ranadive N, et al. Health impacts of chemical irritants used for crowd control: a systematic review of the injuries and deaths caused by tear gas and pepper spray. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:831. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4814-6

- Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J, Van J, et al. Capsaicin 8% patch in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2017;18:42-53. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.09.008

- Yong YL, Tan LT-H, Ming LC, et al. The effectiveness and safety of topical capsaicin in postherpetic neuralgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:538. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00538

- Firoz EF, Levin JM, Hartman RD, et al. Lip plumper contact urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:861-863. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.028

- Jones LA, Tandberg D, Troutman WG. Household treatment for “chile burns” of the hands. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1987;25:483-491. doi:10.3109/15563658708992651

- Saxena AK, Mandhyan R. Multimodal approach for the management of Hunan hand syndrome: a case report. Pain Pract. 2013;13:227-230. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00567.x

- Cordell GA, Araujo OE. Capsaicin: identification, nomenclature, and pharmacotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:330-336. doi:10.1177/106002809302700316

- Baranidharan G, Das S, Bhaskar A. A review of the high-concentration capsaicin patch and experience in its use in the management of neuropathic pain. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:287-297. doi:10.1177/1756285613496862

- Carrizo García C, Barfuss MHJ, Sehr EM, et al. Phylogenetic relationships, diversification and expansion of chili peppers (Capsicum, Solanaceae). Ann Bot. 2016;118:35-51. doi:10.1093/aob/mcw079

- Basharat S, Gilani SA, Iftikhar F, et al. Capsaicin: plants of the genus Capsicum and positive effect of Oriental spice on skin health. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;33:331-341. doi:10.1159/000512196

- Hopps JJ, Dunn WR, Randall MD. Vasorelaxation to capsaicin and its effects on calcium influx in arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;681:88-93. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.02.019

- Burks TF, Buck SH, Miller MS. Mechanisms of depletion of substance P by capsaicin. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2531-2534.

- Ellis CN, Berberian B, Sulica VI, et al. A double-blind evaluation of topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:438-442. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70208-b

- Fusco BM, Alessandri M. Analgesic effect of capsaicin in idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:375-377. doi:10.1213/00000539-199203000-00011

- Casanueva B, Rodero B, Quintial C, et al. Short-term efficacy of topical capsaicin therapy in severely affected fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2665-2670. doi:10.1007/s00296-012-2490-5

- Bley K, Boorman G, Mohammad B, et al. A comprehensive review of the carcinogenic and anticarcinogenic potential of capsaicin. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:847-873. doi:10.1177/0192623312444471

- Jones IA, Togashi R, Wilson ML, et al. Intra-articular treatment options for knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15:77-90. doi:10.1038/s41584-018-0123-4

- Campbell JN, Stevens R, Hanson P, et al. Injectable capsaicin for the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. Molecules. 2021;26:778.

- Maji AK, Banerji P. Phytochemistry and gastrointestinal benefits of the medicinal spice, Capsicum annum L. (chilli): a review. J Complement Integr Med. 2016;13:97-122. doi:10.1515jcim-2015-0037

- Baenas N, Belovié M, Ilie N, et al. Industrial use of pepper (Capsicum annum L.) derived products: technological benefits and biological advantages. Food Chem. 2019;274:872-885. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.047

- Lin RJ, Wu IJ, Hong JY, et al. Capsaicin-induced TRIB3 upregulation promotes apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4237-4248. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S162383

- Jung MY, Kang HJ, Moon A. Capsaicin-induced apoptosis in SK-Hep-1 hepatocarcinoma cells involves Bcl-2 downregulation and caspase-3 activation. Cancer Lett. 2001;165:139-145. doi:10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00426-8

- Ito K, Nakazato T, Yamato K, et al. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cells by homovanillic acid derivative, capsaicin, through oxidative stress: implication of phosphorylation of p53 at Ser-15 residue by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1071-1078. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1670

- Báez S, Tsuchiya Y, Calvo A, et al. Genetic variants involved in gallstone formation and capsaicin metabolism, and the risk of gallbladder cancer in Chilean women. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:372-378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.372

Cutaneous Manifestations

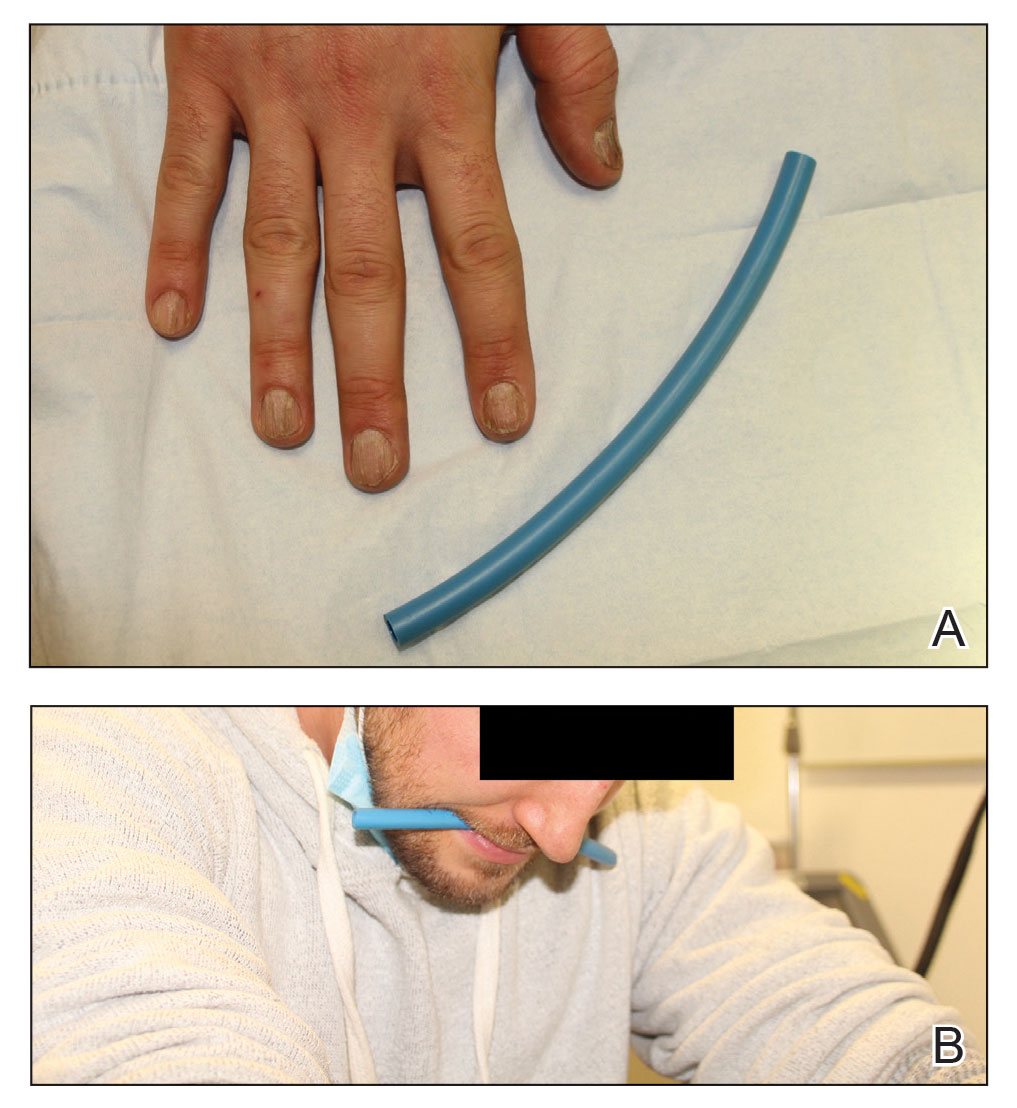

Capsicum peppers are used worldwide in preparing spicy dishes. Their active ingredient—capsaicin—is used as a topical medicine to treat localized pain. Capsicum peppers can cause irritant contact dermatitis with symptoms of erythema, cutaneous burning, and itch.1

Irritant contact dermatitis is a common occupational skin disorder. Many cooks have experienced the sting of a chili pepper after contact with the hands or eyes. Cases of chronic exposure to Capsicum peppers with persistent burning and pain have been called Hunan hand syndrome.2 Capsicum peppers also have induced allergic contact dermatitis in a food production worker.3

Capsicum peppers also are used in pepper spray, tear gas, and animal repellents because of their stinging properties. These agents usually cause cutaneous tingling and burning that soon resolves; however, a review of 31 studies showed that crowd-control methods with Capsicum-containing tear gas and pepper spray can cause moderate to severe skin damage such as a persistent skin rash or erythema, or even first-, second-, or third-degree burns.4

Topical application of capsaicin isolate is meant to cause burning and deplete local neuropeptides, with a cutaneous reaction that ranges from mild to intolerable.5,6 Capsaicin also is found in other products. In one published case report, a 3-year-old boy broke out in facial urticaria when his mother kissed him on the cheek after she applied lip plumper containing capsaicin to her lips.7 Dermatologists should consider capsaicin an active ingredient that can irritate the skin in the garden, in the kitchen, and in topical products.

Obtaining Relief

Capsaicin-induced dermatitis can be relieved by washing the area with soap, detergent, baking soda, or oily compounds that act as solvents for the nonpolar capsaicin.8 Application of ice water or a high-potency topical steroid also may help. If the reaction is severe and persistent, a continuous stellate ganglion block may alleviate the pain of capsaicin-induced contact dermatitis.9

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The Capsicum genus includes chili peppers, paprika, and red peppers. Capsicum peppers are native to tropical regions of the Americas (Figure). The use of Capsicum peppers in food can be traced to Indigenous peoples of Mexico as early as 7000

Capsicum belongs to the family Solanaceae, which includes tobacco, tomatoes, potatoes, and nightshade plants. There are many varieties of peppers in the Capsicum genus, with 5 domesticated species: Capsicum annuum, Capsicum baccatum, Capsicum chinense, Capsicum frutescens, and Capsicum pubescens. These include bell, poblano, cayenne, tabasco, habanero, and ají peppers, among others. Capsicum species grow as a shrub with flowers that rotate to stellate corollas and rounded berries of different sizes and colors.12 Capsaicin and other alkaloids are concentrated in the fruit; therefore, Capsicum dermatitis is most commonly induced by contact with the flesh of peppers.

Irritant Chemicals

Capsaicin (8-methyl-6-nonanoyl vanillylamide) is a nonpolar phenol, which is why washing skin that has come in contact with capsaicin with water or vinegar alone is insufficient to solubilize it.13 Capsaicin binds to the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a calcium channel on neurons that opens in response to heat. When bound, the channel opens at a lower temperature threshold and depolarizes nerve endings, leading to vasodilation and activation of sensory nerves.14 Substance P is released and the individual experiences a painful burning sensation. When purified capsaicin is frequently applied at an appropriate dose, synthesis of substance P is diminished, resulting in reduced local pain overall.15

Capsaicin does not affect neurons without TRPV1, and administration of capsaicin is not painful if given with anesthesia. An inappropriately high dose of capsaicin destroys cells in the epidermal barrier, resulting in water loss and inducing release of vasoactive peptides and inflammatory cytokines.1 Careful handling of Capsicum peppers and capsaicin products can reduce the risk for irritation.

Medicinal Use

On-/Off-Label and Potential Uses—Capsaicin is US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in arthritis and musculoskeletal pain. It also is used to treat diabetic neuropathy,5 postherpetic neuralgia,6 psoriasis,16 and other conditions. Studies have shown that capsaicin might be useful in treating trigeminal neuralgia,17 fibromyalgia,18 migraines,14 cluster headaches,9 and HIV-associated distal sensory neuropathy.5

Delivery of Capsaicin—Capsaicin preferentially acts on C-fibers, which transmit dull, aching, chronic pain.19 The compound is available as a cream, lotion, and large bandage (for the lower back), as well as low- and high-dose patches. Capsaicin creams, lotions, and the low-dose patch are uncomfortable and must be applied for 4 to 6 weeks to take effect, which may impact patient adherence. The high-dose patch, which requires administration under local anesthesia by a health care worker, brings pain relief with a single use and improves adherence.11 Synthetic TRPV1-agonist injectables based on capsaicin have undergone clinical trials for localized pain (eg, postoperative musculoskeletal pain); many patients experience pain relief, though benefit fades over weeks to months.20,21

Use in Traditional Medicine—Capsicum peppers have been used to aid digestion and promote healing in gastrointestinal conditions, such as dyspepsia.22 The peppers are a source of important vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A, C, and E; many of the B complex vitamins; and magnesium, calcium, and iron.23

Use as Cancer Therapy—Studies of the use of capsaicin in treating cancer have produced controversial results. In cell and animal models, capsaicin induces apoptosis through downregulation of the Bcl-2 protein; upregulation of oxidative stress, tribbles-related protein 3 (TRIB3), and caspase-3; and other pathways.19,24-26 On the other hand, consumption of Capsicum peppers has been associated with cancer of the stomach and gallbladder.27 Capsaicin might have anticarcinogenic properties, but its mechanism of action varies, depending on variables not fully understood.

Final Thoughts

Capsaicin is a neuropeptide-active compound found in Capsicum peppers that has many promising applications for use. However, dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of a skin reaction to this compound from handling peppers and using topical medicines. Exposure to capsaicin can cause irritant contact dermatitis that may require clinical care.

Cutaneous Manifestations

Capsicum peppers are used worldwide in preparing spicy dishes. Their active ingredient—capsaicin—is used as a topical medicine to treat localized pain. Capsicum peppers can cause irritant contact dermatitis with symptoms of erythema, cutaneous burning, and itch.1

Irritant contact dermatitis is a common occupational skin disorder. Many cooks have experienced the sting of a chili pepper after contact with the hands or eyes. Cases of chronic exposure to Capsicum peppers with persistent burning and pain have been called Hunan hand syndrome.2 Capsicum peppers also have induced allergic contact dermatitis in a food production worker.3

Capsicum peppers also are used in pepper spray, tear gas, and animal repellents because of their stinging properties. These agents usually cause cutaneous tingling and burning that soon resolves; however, a review of 31 studies showed that crowd-control methods with Capsicum-containing tear gas and pepper spray can cause moderate to severe skin damage such as a persistent skin rash or erythema, or even first-, second-, or third-degree burns.4

Topical application of capsaicin isolate is meant to cause burning and deplete local neuropeptides, with a cutaneous reaction that ranges from mild to intolerable.5,6 Capsaicin also is found in other products. In one published case report, a 3-year-old boy broke out in facial urticaria when his mother kissed him on the cheek after she applied lip plumper containing capsaicin to her lips.7 Dermatologists should consider capsaicin an active ingredient that can irritate the skin in the garden, in the kitchen, and in topical products.

Obtaining Relief

Capsaicin-induced dermatitis can be relieved by washing the area with soap, detergent, baking soda, or oily compounds that act as solvents for the nonpolar capsaicin.8 Application of ice water or a high-potency topical steroid also may help. If the reaction is severe and persistent, a continuous stellate ganglion block may alleviate the pain of capsaicin-induced contact dermatitis.9

Identifying Features and Plant Facts

The Capsicum genus includes chili peppers, paprika, and red peppers. Capsicum peppers are native to tropical regions of the Americas (Figure). The use of Capsicum peppers in food can be traced to Indigenous peoples of Mexico as early as 7000

Capsicum belongs to the family Solanaceae, which includes tobacco, tomatoes, potatoes, and nightshade plants. There are many varieties of peppers in the Capsicum genus, with 5 domesticated species: Capsicum annuum, Capsicum baccatum, Capsicum chinense, Capsicum frutescens, and Capsicum pubescens. These include bell, poblano, cayenne, tabasco, habanero, and ají peppers, among others. Capsicum species grow as a shrub with flowers that rotate to stellate corollas and rounded berries of different sizes and colors.12 Capsaicin and other alkaloids are concentrated in the fruit; therefore, Capsicum dermatitis is most commonly induced by contact with the flesh of peppers.

Irritant Chemicals

Capsaicin (8-methyl-6-nonanoyl vanillylamide) is a nonpolar phenol, which is why washing skin that has come in contact with capsaicin with water or vinegar alone is insufficient to solubilize it.13 Capsaicin binds to the transient receptor potential vanilloid 1 (TRPV1), a calcium channel on neurons that opens in response to heat. When bound, the channel opens at a lower temperature threshold and depolarizes nerve endings, leading to vasodilation and activation of sensory nerves.14 Substance P is released and the individual experiences a painful burning sensation. When purified capsaicin is frequently applied at an appropriate dose, synthesis of substance P is diminished, resulting in reduced local pain overall.15

Capsaicin does not affect neurons without TRPV1, and administration of capsaicin is not painful if given with anesthesia. An inappropriately high dose of capsaicin destroys cells in the epidermal barrier, resulting in water loss and inducing release of vasoactive peptides and inflammatory cytokines.1 Careful handling of Capsicum peppers and capsaicin products can reduce the risk for irritation.

Medicinal Use

On-/Off-Label and Potential Uses—Capsaicin is US Food and Drug Administration approved for use in arthritis and musculoskeletal pain. It also is used to treat diabetic neuropathy,5 postherpetic neuralgia,6 psoriasis,16 and other conditions. Studies have shown that capsaicin might be useful in treating trigeminal neuralgia,17 fibromyalgia,18 migraines,14 cluster headaches,9 and HIV-associated distal sensory neuropathy.5

Delivery of Capsaicin—Capsaicin preferentially acts on C-fibers, which transmit dull, aching, chronic pain.19 The compound is available as a cream, lotion, and large bandage (for the lower back), as well as low- and high-dose patches. Capsaicin creams, lotions, and the low-dose patch are uncomfortable and must be applied for 4 to 6 weeks to take effect, which may impact patient adherence. The high-dose patch, which requires administration under local anesthesia by a health care worker, brings pain relief with a single use and improves adherence.11 Synthetic TRPV1-agonist injectables based on capsaicin have undergone clinical trials for localized pain (eg, postoperative musculoskeletal pain); many patients experience pain relief, though benefit fades over weeks to months.20,21

Use in Traditional Medicine—Capsicum peppers have been used to aid digestion and promote healing in gastrointestinal conditions, such as dyspepsia.22 The peppers are a source of important vitamins and minerals, including vitamins A, C, and E; many of the B complex vitamins; and magnesium, calcium, and iron.23

Use as Cancer Therapy—Studies of the use of capsaicin in treating cancer have produced controversial results. In cell and animal models, capsaicin induces apoptosis through downregulation of the Bcl-2 protein; upregulation of oxidative stress, tribbles-related protein 3 (TRIB3), and caspase-3; and other pathways.19,24-26 On the other hand, consumption of Capsicum peppers has been associated with cancer of the stomach and gallbladder.27 Capsaicin might have anticarcinogenic properties, but its mechanism of action varies, depending on variables not fully understood.

Final Thoughts

Capsaicin is a neuropeptide-active compound found in Capsicum peppers that has many promising applications for use. However, dermatologists should be aware of the possibility of a skin reaction to this compound from handling peppers and using topical medicines. Exposure to capsaicin can cause irritant contact dermatitis that may require clinical care.

- Otang WM, Grierson DS, Afolayan AJ. A survey of plants responsible for causing irritant contact dermatitis in the Amathole district, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:274-284. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.002

- Weinberg RB. Hunan hand. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1020.

- Lambrecht C, Goossens A. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by capsicum. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:252-253. doi:10.1111/cod.12345

- Haar RJ, Iacopino V, Ranadive N, et al. Health impacts of chemical irritants used for crowd control: a systematic review of the injuries and deaths caused by tear gas and pepper spray. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:831. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4814-6

- Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J, Van J, et al. Capsaicin 8% patch in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2017;18:42-53. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.09.008

- Yong YL, Tan LT-H, Ming LC, et al. The effectiveness and safety of topical capsaicin in postherpetic neuralgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:538. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00538

- Firoz EF, Levin JM, Hartman RD, et al. Lip plumper contact urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:861-863. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.028

- Jones LA, Tandberg D, Troutman WG. Household treatment for “chile burns” of the hands. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1987;25:483-491. doi:10.3109/15563658708992651

- Saxena AK, Mandhyan R. Multimodal approach for the management of Hunan hand syndrome: a case report. Pain Pract. 2013;13:227-230. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00567.x

- Cordell GA, Araujo OE. Capsaicin: identification, nomenclature, and pharmacotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:330-336. doi:10.1177/106002809302700316

- Baranidharan G, Das S, Bhaskar A. A review of the high-concentration capsaicin patch and experience in its use in the management of neuropathic pain. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:287-297. doi:10.1177/1756285613496862

- Carrizo García C, Barfuss MHJ, Sehr EM, et al. Phylogenetic relationships, diversification and expansion of chili peppers (Capsicum, Solanaceae). Ann Bot. 2016;118:35-51. doi:10.1093/aob/mcw079

- Basharat S, Gilani SA, Iftikhar F, et al. Capsaicin: plants of the genus Capsicum and positive effect of Oriental spice on skin health. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;33:331-341. doi:10.1159/000512196

- Hopps JJ, Dunn WR, Randall MD. Vasorelaxation to capsaicin and its effects on calcium influx in arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;681:88-93. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.02.019

- Burks TF, Buck SH, Miller MS. Mechanisms of depletion of substance P by capsaicin. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2531-2534.

- Ellis CN, Berberian B, Sulica VI, et al. A double-blind evaluation of topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:438-442. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70208-b

- Fusco BM, Alessandri M. Analgesic effect of capsaicin in idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:375-377. doi:10.1213/00000539-199203000-00011

- Casanueva B, Rodero B, Quintial C, et al. Short-term efficacy of topical capsaicin therapy in severely affected fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2665-2670. doi:10.1007/s00296-012-2490-5

- Bley K, Boorman G, Mohammad B, et al. A comprehensive review of the carcinogenic and anticarcinogenic potential of capsaicin. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:847-873. doi:10.1177/0192623312444471

- Jones IA, Togashi R, Wilson ML, et al. Intra-articular treatment options for knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15:77-90. doi:10.1038/s41584-018-0123-4

- Campbell JN, Stevens R, Hanson P, et al. Injectable capsaicin for the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. Molecules. 2021;26:778.

- Maji AK, Banerji P. Phytochemistry and gastrointestinal benefits of the medicinal spice, Capsicum annum L. (chilli): a review. J Complement Integr Med. 2016;13:97-122. doi:10.1515jcim-2015-0037

- Baenas N, Belovié M, Ilie N, et al. Industrial use of pepper (Capsicum annum L.) derived products: technological benefits and biological advantages. Food Chem. 2019;274:872-885. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.047

- Lin RJ, Wu IJ, Hong JY, et al. Capsaicin-induced TRIB3 upregulation promotes apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4237-4248. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S162383

- Jung MY, Kang HJ, Moon A. Capsaicin-induced apoptosis in SK-Hep-1 hepatocarcinoma cells involves Bcl-2 downregulation and caspase-3 activation. Cancer Lett. 2001;165:139-145. doi:10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00426-8

- Ito K, Nakazato T, Yamato K, et al. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cells by homovanillic acid derivative, capsaicin, through oxidative stress: implication of phosphorylation of p53 at Ser-15 residue by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1071-1078. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1670

- Báez S, Tsuchiya Y, Calvo A, et al. Genetic variants involved in gallstone formation and capsaicin metabolism, and the risk of gallbladder cancer in Chilean women. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:372-378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.372

- Otang WM, Grierson DS, Afolayan AJ. A survey of plants responsible for causing irritant contact dermatitis in the Amathole district, Eastern Cape, South Africa. J Ethnopharmacol. 2014;157:274-284. doi:10.1016/j.jep.2014.10.002

- Weinberg RB. Hunan hand. N Engl J Med. 1981;305:1020.

- Lambrecht C, Goossens A. Occupational allergic contact dermatitis caused by capsicum. Contact Dermatitis. 2015;72:252-253. doi:10.1111/cod.12345

- Haar RJ, Iacopino V, Ranadive N, et al. Health impacts of chemical irritants used for crowd control: a systematic review of the injuries and deaths caused by tear gas and pepper spray. BMC Public Health. 2017;17:831. doi:10.1186/s12889-017-4814-6

- Simpson DM, Robinson-Papp J, Van J, et al. Capsaicin 8% patch in painful diabetic peripheral neuropathy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. J Pain. 2017;18:42-53. doi:10.1016/j.jpain.2016.09.008

- Yong YL, Tan LT-H, Ming LC, et al. The effectiveness and safety of topical capsaicin in postherpetic neuralgia: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Pharmacol. 2016;7:538. doi:10.3389/fphar.2016.00538

- Firoz EF, Levin JM, Hartman RD, et al. Lip plumper contact urticaria. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2009;60:861-863. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2008.09.028

- Jones LA, Tandberg D, Troutman WG. Household treatment for “chile burns” of the hands. J Toxicol Clin Toxicol. 1987;25:483-491. doi:10.3109/15563658708992651

- Saxena AK, Mandhyan R. Multimodal approach for the management of Hunan hand syndrome: a case report. Pain Pract. 2013;13:227-230. doi:10.1111/j.1533-2500.2012.00567.x

- Cordell GA, Araujo OE. Capsaicin: identification, nomenclature, and pharmacotherapy. Ann Pharmacother. 1993;27:330-336. doi:10.1177/106002809302700316

- Baranidharan G, Das S, Bhaskar A. A review of the high-concentration capsaicin patch and experience in its use in the management of neuropathic pain. Ther Adv Neurol Disord. 2013;6:287-297. doi:10.1177/1756285613496862

- Carrizo García C, Barfuss MHJ, Sehr EM, et al. Phylogenetic relationships, diversification and expansion of chili peppers (Capsicum, Solanaceae). Ann Bot. 2016;118:35-51. doi:10.1093/aob/mcw079

- Basharat S, Gilani SA, Iftikhar F, et al. Capsaicin: plants of the genus Capsicum and positive effect of Oriental spice on skin health. Skin Pharmacol Physiol. 2020;33:331-341. doi:10.1159/000512196

- Hopps JJ, Dunn WR, Randall MD. Vasorelaxation to capsaicin and its effects on calcium influx in arteries. Eur J Pharmacol. 2012;681:88-93. doi:10.1016/j.ejphar.2012.02.019

- Burks TF, Buck SH, Miller MS. Mechanisms of depletion of substance P by capsaicin. Fed Proc. 1985;44:2531-2534.

- Ellis CN, Berberian B, Sulica VI, et al. A double-blind evaluation of topical capsaicin in pruritic psoriasis. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;29:438-442. doi:10.1016/0190-9622(93)70208-b

- Fusco BM, Alessandri M. Analgesic effect of capsaicin in idiopathic trigeminal neuralgia. Anesth Analg. 1992;74:375-377. doi:10.1213/00000539-199203000-00011

- Casanueva B, Rodero B, Quintial C, et al. Short-term efficacy of topical capsaicin therapy in severely affected fibromyalgia patients. Rheumatol Int. 2013;33:2665-2670. doi:10.1007/s00296-012-2490-5

- Bley K, Boorman G, Mohammad B, et al. A comprehensive review of the carcinogenic and anticarcinogenic potential of capsaicin. Toxicol Pathol. 2012;40:847-873. doi:10.1177/0192623312444471

- Jones IA, Togashi R, Wilson ML, et al. Intra-articular treatment options for knee osteoarthritis. Nat Rev Rheumatol. 2019;15:77-90. doi:10.1038/s41584-018-0123-4

- Campbell JN, Stevens R, Hanson P, et al. Injectable capsaicin for the management of pain due to osteoarthritis. Molecules. 2021;26:778.

- Maji AK, Banerji P. Phytochemistry and gastrointestinal benefits of the medicinal spice, Capsicum annum L. (chilli): a review. J Complement Integr Med. 2016;13:97-122. doi:10.1515jcim-2015-0037

- Baenas N, Belovié M, Ilie N, et al. Industrial use of pepper (Capsicum annum L.) derived products: technological benefits and biological advantages. Food Chem. 2019;274:872-885. doi:10.1016/j.foodchem.2018.09.047

- Lin RJ, Wu IJ, Hong JY, et al. Capsaicin-induced TRIB3 upregulation promotes apoptosis in cancer cells. Cancer Manag Res. 2018;10:4237-4248. doi:10.2147/CMAR.S162383

- Jung MY, Kang HJ, Moon A. Capsaicin-induced apoptosis in SK-Hep-1 hepatocarcinoma cells involves Bcl-2 downregulation and caspase-3 activation. Cancer Lett. 2001;165:139-145. doi:10.1016/s0304-3835(01)00426-8

- Ito K, Nakazato T, Yamato K, et al. Induction of apoptosis in leukemic cells by homovanillic acid derivative, capsaicin, through oxidative stress: implication of phosphorylation of p53 at Ser-15 residue by reactive oxygen species. Cancer Res. 2004;64:1071-1078. doi:10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-1670

- Báez S, Tsuchiya Y, Calvo A, et al. Genetic variants involved in gallstone formation and capsaicin metabolism, and the risk of gallbladder cancer in Chilean women. World J Gastroenterol. 2010;16:372-378. doi:10.3748/wjg.v16.i3.372

Practice Points

- Capsicum peppers—used worldwide in food preparation, pepper spray, and cosmetic products—can cause irritant dermatitis from the active ingredient capsaicin.

- Capsaicin, which is isolated as a medication to treat musculoskeletal pain, postherpetic neuralgia, and more, can cause a mild local skin reaction.

Cutaneous Signs of Malnutrition Secondary to Eating Disorders

Eating disorders (EDs) and feeding disorders refer to a wide spectrum of complex biopsychosocial illnesses. The spectrum of EDs encompasses anorexia nervosa (AN), bulimia nervosa (BN), binge eating disorder, and other specified feeding or eating disorders. Feeding disorders, distinguished from EDs based on the absence of body image disturbance, include pica, rumination syndrome, and avoidant/restrictive food intake disorder (ARFID).1