User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Optimizing Patient Care With Teledermatology: Improving Access, Efficiency, and Satisfaction

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology

Studies generally have shown very high patient satisfaction rates and shorter wait times with teledermatology vs in-person visits; for example, in a systematic review of 15 teledermatology studies including 7781 patients, more than 80% of participants reported high satisfaction with their telemedicine visit, with up to 92% reporting that they would choose to do a televisit again.4 In a retrospective analysis of 615 Zocdoc physicians, 65% of whom were dermatologists, mean wait times were 2.4 days for virtual appointments compared with 11.7 days for in-person appointments.5 Similarly, in a retrospective single-institution study, mean wait times for televisits were 14.3 days compared with 34.7 days for in-person referrals.6

Follow-Up Visits for Nail Disorders Via Teledermatology

Teledermatology may be particularly well suited for treating patients with nail disorders. In a prospective observational study, Onyeka et al7 accessed 813 images from 63 dermatology patients via teledermatology over a 6-month period to assess distance, focus, brightness, background, and image quality; of them, 83% were rated as high quality. Notably, images of nail disorders, skin growths, or pigmentation disorders were rated as having better image quality than images of inflammatory skin conditions (odds ratio [OR], 4.2-12.9 [P<.005]).7 In a retrospective study of 107 telemedicine visits for nail disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with longitudinal melanonychia were recommended for in-person visits for physical examination and dermoscopy, as were patients with suspected onychomycosis, who required nail plate sampling for diagnostic confirmation; however, approximately half of visits did not require in-person follow-up, including those patients with confirmed onychomycosis.8 Onychomycosis patients could be examined for clinical improvement and counseled on medication compliance via telemedicine. Other patients who did not require in-person follow-ups were those with traumatic nail disorders such as subungual hematoma and retronychia as well as those with body‐focused repetitive behaviors, including habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania.8

Patients undergoing nail biopsies to rule out malignancies or to diagnose inflammatory nail disorders also may be managed via telemedicine. Patients for whom nail biopsies are recommended often are anxious about the procedure, which may be due to portrayal of nail trauma in the media9 or lack of accurate information on nail biopsies online.10 Therefore, counseling via telemedicine about the details of the procedure in a patient-friendly way (eg, showing an animated video and narrating it11) can allay anxiety without the inconvenience, cost, and time missed from work associated with traveling to an in-person visit. In addition, postoperative counseling ideally is performed via telemedicine because complications following nail procedures are uncommon. In a retrospective study of 502 patients who underwent a nail biopsy at a single academic center, only 14 developed surgical site infections within 8 days on average (range, 5–13 days), with a higher infection risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P<.0003).12

Advantages and Limitations

There are many benefits to incorporating telemedicine into dermatology practices, including reduced overhead costs, convenience and time saved for patients, and flexibility and improved work-life balance for dermatologists. In addition, because the number of in-person visits seen generally is fixed due to space constraints and work-hour restrictions, delegating follow-up visits to telemedicine can free up in-person slots for new patients and those needing procedures. However, there also are some inherent limitations to telemedicine: technology access, vision or hearing difficulties or low digital health literacy, or language barriers. In the prospective observational study by Onyeka et al7 analyzing 813 teledermatology images, patients aged 65 to 74 years sent in more clinically useful images (OR, 7.9) and images that were more often in focus (OR, 2.6) compared with patients older than 85 years.

Final Thoughts

Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice is a valuable tool for triaging patients with acute issues, improving patient care and health care access, making practices more efficient, and improving dermatologist flexibility and work-life balance. Further development of teledermatology to provide access to underserved populations prioritizing dermatologist reimbursement and progress on technologic innovations will make teledermatology even more useful in the coming years.

- He A, Ti Kim T, Nguyen KD. Utilization of teledermatology services for dermatological diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1059-1062.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Wang RH, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL, et al. Synchronous and asynchronous teledermatology: a narrative review of strengths and limitations. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28:533-538.

- Miller J, Jones E. Shaping the future of teledermatology: a literature review of patient and provider satisfaction with synchronous teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1903-1909.

- Gu L, Xiang L, Lipner SR. Analysis of availability of online dermatology appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:517-520.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an eConsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;83:1633-1638.

- Onyeka S, Kim J, Eid E, et al. Quality of images submitted by older patients to a teledermatology platform. Abstract presented at the Society of Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting; May 15-18, 2024; Dallas, TX.

- Chang MJ, Stewart CR, Lipner SR. Retrospective study of nail telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14630.

- Albucker SJ, Falotico JM, Lipner SR. A real nail biter: a cross-sectional study of 75 nail trauma scenes in international films and television series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:288-291.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Hill RC, Ho B, Lipner SR. Assuaging patient anxiety about nail biopsies with an animated educational video. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online March 29, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.031.

- Axler E, Lu A, Darrell M, et al. Surgical site infections are uncommon following nail biopsies in a single-center case-control study of 502 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.017

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology

Studies generally have shown very high patient satisfaction rates and shorter wait times with teledermatology vs in-person visits; for example, in a systematic review of 15 teledermatology studies including 7781 patients, more than 80% of participants reported high satisfaction with their telemedicine visit, with up to 92% reporting that they would choose to do a televisit again.4 In a retrospective analysis of 615 Zocdoc physicians, 65% of whom were dermatologists, mean wait times were 2.4 days for virtual appointments compared with 11.7 days for in-person appointments.5 Similarly, in a retrospective single-institution study, mean wait times for televisits were 14.3 days compared with 34.7 days for in-person referrals.6

Follow-Up Visits for Nail Disorders Via Teledermatology

Teledermatology may be particularly well suited for treating patients with nail disorders. In a prospective observational study, Onyeka et al7 accessed 813 images from 63 dermatology patients via teledermatology over a 6-month period to assess distance, focus, brightness, background, and image quality; of them, 83% were rated as high quality. Notably, images of nail disorders, skin growths, or pigmentation disorders were rated as having better image quality than images of inflammatory skin conditions (odds ratio [OR], 4.2-12.9 [P<.005]).7 In a retrospective study of 107 telemedicine visits for nail disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with longitudinal melanonychia were recommended for in-person visits for physical examination and dermoscopy, as were patients with suspected onychomycosis, who required nail plate sampling for diagnostic confirmation; however, approximately half of visits did not require in-person follow-up, including those patients with confirmed onychomycosis.8 Onychomycosis patients could be examined for clinical improvement and counseled on medication compliance via telemedicine. Other patients who did not require in-person follow-ups were those with traumatic nail disorders such as subungual hematoma and retronychia as well as those with body‐focused repetitive behaviors, including habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania.8

Patients undergoing nail biopsies to rule out malignancies or to diagnose inflammatory nail disorders also may be managed via telemedicine. Patients for whom nail biopsies are recommended often are anxious about the procedure, which may be due to portrayal of nail trauma in the media9 or lack of accurate information on nail biopsies online.10 Therefore, counseling via telemedicine about the details of the procedure in a patient-friendly way (eg, showing an animated video and narrating it11) can allay anxiety without the inconvenience, cost, and time missed from work associated with traveling to an in-person visit. In addition, postoperative counseling ideally is performed via telemedicine because complications following nail procedures are uncommon. In a retrospective study of 502 patients who underwent a nail biopsy at a single academic center, only 14 developed surgical site infections within 8 days on average (range, 5–13 days), with a higher infection risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P<.0003).12

Advantages and Limitations

There are many benefits to incorporating telemedicine into dermatology practices, including reduced overhead costs, convenience and time saved for patients, and flexibility and improved work-life balance for dermatologists. In addition, because the number of in-person visits seen generally is fixed due to space constraints and work-hour restrictions, delegating follow-up visits to telemedicine can free up in-person slots for new patients and those needing procedures. However, there also are some inherent limitations to telemedicine: technology access, vision or hearing difficulties or low digital health literacy, or language barriers. In the prospective observational study by Onyeka et al7 analyzing 813 teledermatology images, patients aged 65 to 74 years sent in more clinically useful images (OR, 7.9) and images that were more often in focus (OR, 2.6) compared with patients older than 85 years.

Final Thoughts

Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice is a valuable tool for triaging patients with acute issues, improving patient care and health care access, making practices more efficient, and improving dermatologist flexibility and work-life balance. Further development of teledermatology to provide access to underserved populations prioritizing dermatologist reimbursement and progress on technologic innovations will make teledermatology even more useful in the coming years.

Telemedicine interest, which was relatively quiescent prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, has surged in popularity in the past few years.1 It can now be utilized seamlessly in dermatology practices to deliver exceptional patient care while reducing costs and travel time and offering dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance. Teledermatology applications include synchronous, asynchronous, and hybrid platforms.2 For synchronous teledermatology, patient visits are carried out in real time with audio and video technology.3 For asynchronous teledermatology—also known as the store-and-forward model—the dermatologist receives the patient’s history and photographs and then renders an assessment and treatment plan.2 Hybrid teledermatology uses real-time audio and video conferencing for history taking, assessment and treatment plan, and patient education, with photographs sent asynchronously.3 Telemedicine may not be initially intuitive or easy to integrate into clinical practice, but with time and effort, it will complement your dermatology practice, making it run more efficiently.

Patient Satisfaction With Teledermatology

Studies generally have shown very high patient satisfaction rates and shorter wait times with teledermatology vs in-person visits; for example, in a systematic review of 15 teledermatology studies including 7781 patients, more than 80% of participants reported high satisfaction with their telemedicine visit, with up to 92% reporting that they would choose to do a televisit again.4 In a retrospective analysis of 615 Zocdoc physicians, 65% of whom were dermatologists, mean wait times were 2.4 days for virtual appointments compared with 11.7 days for in-person appointments.5 Similarly, in a retrospective single-institution study, mean wait times for televisits were 14.3 days compared with 34.7 days for in-person referrals.6

Follow-Up Visits for Nail Disorders Via Teledermatology

Teledermatology may be particularly well suited for treating patients with nail disorders. In a prospective observational study, Onyeka et al7 accessed 813 images from 63 dermatology patients via teledermatology over a 6-month period to assess distance, focus, brightness, background, and image quality; of them, 83% were rated as high quality. Notably, images of nail disorders, skin growths, or pigmentation disorders were rated as having better image quality than images of inflammatory skin conditions (odds ratio [OR], 4.2-12.9 [P<.005]).7 In a retrospective study of 107 telemedicine visits for nail disorders during the COVID-19 pandemic, patients with longitudinal melanonychia were recommended for in-person visits for physical examination and dermoscopy, as were patients with suspected onychomycosis, who required nail plate sampling for diagnostic confirmation; however, approximately half of visits did not require in-person follow-up, including those patients with confirmed onychomycosis.8 Onychomycosis patients could be examined for clinical improvement and counseled on medication compliance via telemedicine. Other patients who did not require in-person follow-ups were those with traumatic nail disorders such as subungual hematoma and retronychia as well as those with body‐focused repetitive behaviors, including habit-tic nail deformity, onychophagia, and onychotillomania.8

Patients undergoing nail biopsies to rule out malignancies or to diagnose inflammatory nail disorders also may be managed via telemedicine. Patients for whom nail biopsies are recommended often are anxious about the procedure, which may be due to portrayal of nail trauma in the media9 or lack of accurate information on nail biopsies online.10 Therefore, counseling via telemedicine about the details of the procedure in a patient-friendly way (eg, showing an animated video and narrating it11) can allay anxiety without the inconvenience, cost, and time missed from work associated with traveling to an in-person visit. In addition, postoperative counseling ideally is performed via telemedicine because complications following nail procedures are uncommon. In a retrospective study of 502 patients who underwent a nail biopsy at a single academic center, only 14 developed surgical site infections within 8 days on average (range, 5–13 days), with a higher infection risk in patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus (P<.0003).12

Advantages and Limitations

There are many benefits to incorporating telemedicine into dermatology practices, including reduced overhead costs, convenience and time saved for patients, and flexibility and improved work-life balance for dermatologists. In addition, because the number of in-person visits seen generally is fixed due to space constraints and work-hour restrictions, delegating follow-up visits to telemedicine can free up in-person slots for new patients and those needing procedures. However, there also are some inherent limitations to telemedicine: technology access, vision or hearing difficulties or low digital health literacy, or language barriers. In the prospective observational study by Onyeka et al7 analyzing 813 teledermatology images, patients aged 65 to 74 years sent in more clinically useful images (OR, 7.9) and images that were more often in focus (OR, 2.6) compared with patients older than 85 years.

Final Thoughts

Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice is a valuable tool for triaging patients with acute issues, improving patient care and health care access, making practices more efficient, and improving dermatologist flexibility and work-life balance. Further development of teledermatology to provide access to underserved populations prioritizing dermatologist reimbursement and progress on technologic innovations will make teledermatology even more useful in the coming years.

- He A, Ti Kim T, Nguyen KD. Utilization of teledermatology services for dermatological diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1059-1062.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Wang RH, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL, et al. Synchronous and asynchronous teledermatology: a narrative review of strengths and limitations. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28:533-538.

- Miller J, Jones E. Shaping the future of teledermatology: a literature review of patient and provider satisfaction with synchronous teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1903-1909.

- Gu L, Xiang L, Lipner SR. Analysis of availability of online dermatology appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:517-520.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an eConsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;83:1633-1638.

- Onyeka S, Kim J, Eid E, et al. Quality of images submitted by older patients to a teledermatology platform. Abstract presented at the Society of Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting; May 15-18, 2024; Dallas, TX.

- Chang MJ, Stewart CR, Lipner SR. Retrospective study of nail telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14630.

- Albucker SJ, Falotico JM, Lipner SR. A real nail biter: a cross-sectional study of 75 nail trauma scenes in international films and television series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:288-291.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Hill RC, Ho B, Lipner SR. Assuaging patient anxiety about nail biopsies with an animated educational video. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online March 29, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.031.

- Axler E, Lu A, Darrell M, et al. Surgical site infections are uncommon following nail biopsies in a single-center case-control study of 502 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.017

- He A, Ti Kim T, Nguyen KD. Utilization of teledermatology services for dermatological diagnoses during the COVID-19 pandemic. Arch Dermatol Res. 2023;315:1059-1062.

- Lee JJ, English JC 3rd. Teledermatology: a review and update. Am J Clin Dermatol. 2018;19:253-260.

- Wang RH, Barbieri JS, Kovarik CL, et al. Synchronous and asynchronous teledermatology: a narrative review of strengths and limitations. J Telemed Telecare. 2022;28:533-538.

- Miller J, Jones E. Shaping the future of teledermatology: a literature review of patient and provider satisfaction with synchronous teledermatology during the COVID-19 pandemic. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2022;47:1903-1909.

- Gu L, Xiang L, Lipner SR. Analysis of availability of online dermatology appointments during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2021;84:517-520.

- Wang RF, Trinidad J, Lawrence J, et al. Improved patient access and outcomes with the integration of an eConsult program (teledermatology) within a large academic medical center. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;83:1633-1638.

- Onyeka S, Kim J, Eid E, et al. Quality of images submitted by older patients to a teledermatology platform. Abstract presented at the Society of Investigative Dermatology Annual Meeting; May 15-18, 2024; Dallas, TX.

- Chang MJ, Stewart CR, Lipner SR. Retrospective study of nail telemedicine visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Dermatol Ther. 2021;34:E14630.

- Albucker SJ, Falotico JM, Lipner SR. A real nail biter: a cross-sectional study of 75 nail trauma scenes in international films and television series. J Cutan Med Surg. 2023;27:288-291.

- Ishack S, Lipner SR. Evaluating the impact and educational value of YouTube videos on nail biopsy procedures. Cutis. 2020;105:148-149, E1.

- Hill RC, Ho B, Lipner SR. Assuaging patient anxiety about nail biopsies with an animated educational video. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online March 29, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.03.031.

- Axler E, Lu A, Darrell M, et al. Surgical site infections are uncommon following nail biopsies in a single-center case-control study of 502 patients. J Am Acad Dermatol. Published online May 15, 2024. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2024.05.017

Practice Points

- Incorporation of telemedicine into dermatologic practice can improve patient access, reduce costs, and offer dermatologists flexibility and improved work-life balance.

- Patient satisfaction with telemedicine is exceedingly high, and teledermatology may be particularly well suited for caring for patients with nail disorders.

Customized Dermal Curette: An Alternative and Effective Shaving Tool in Nail Surgery

Practice Gap

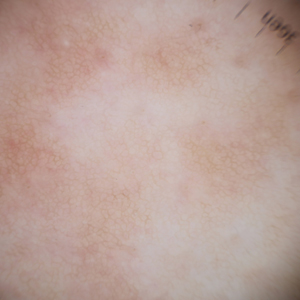

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

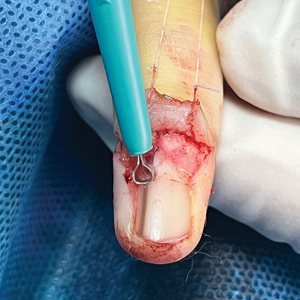

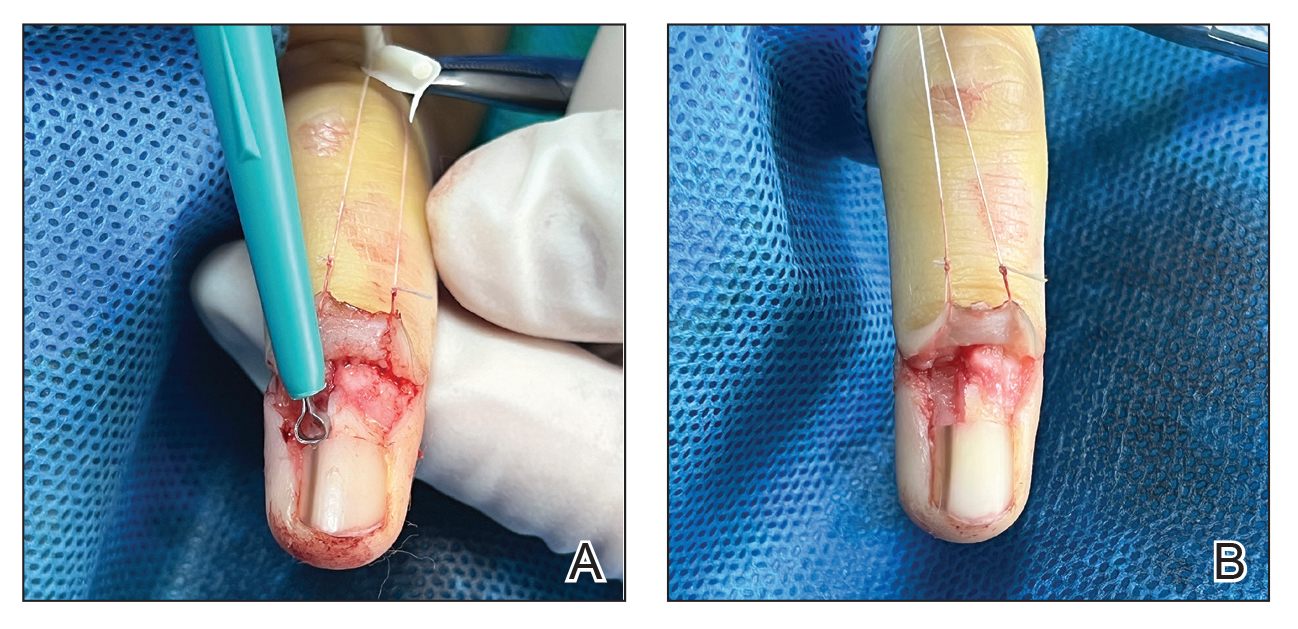

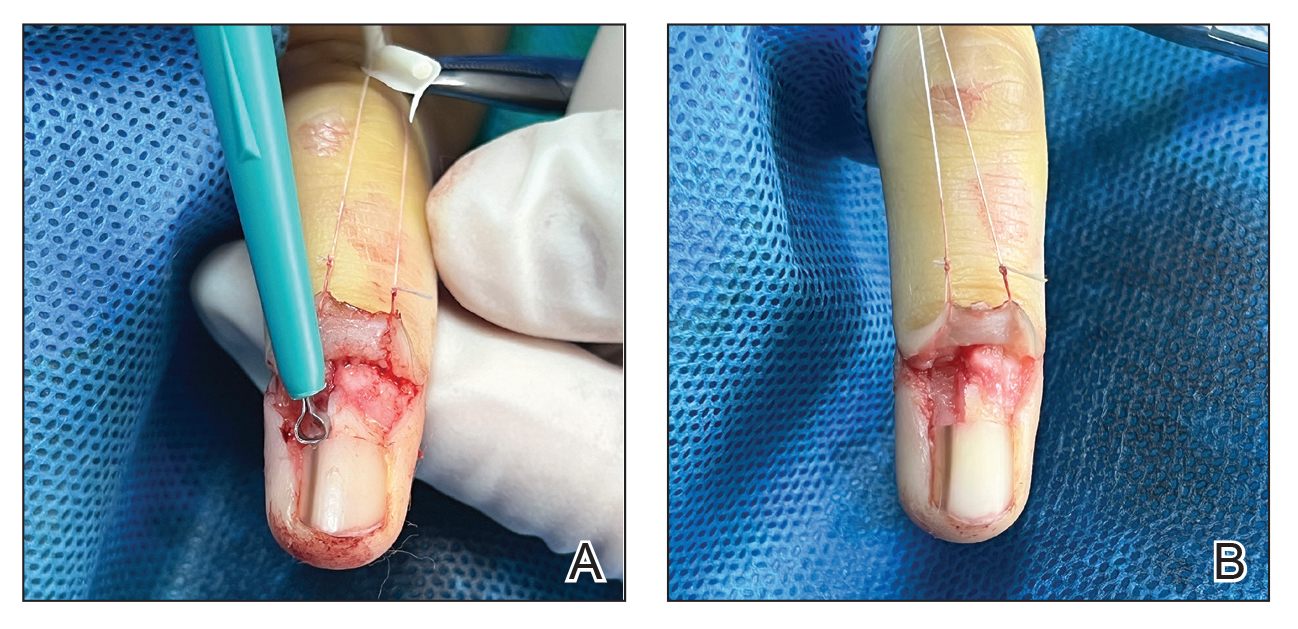

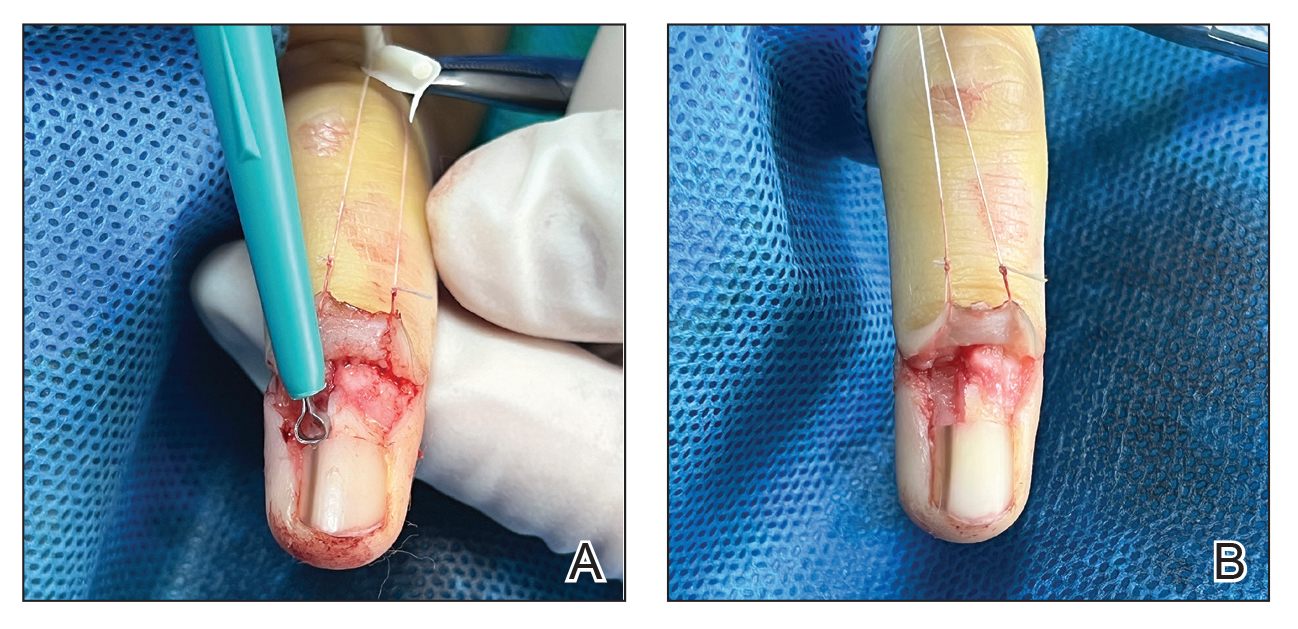

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

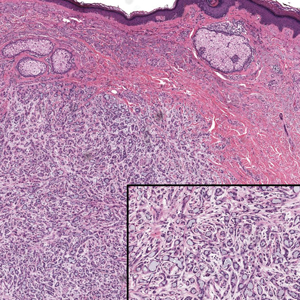

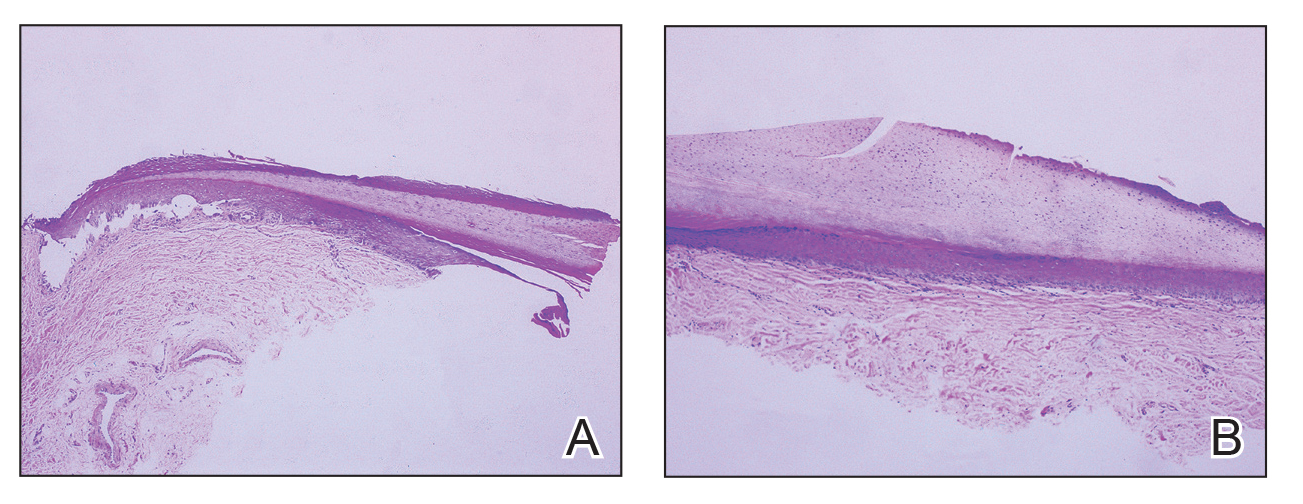

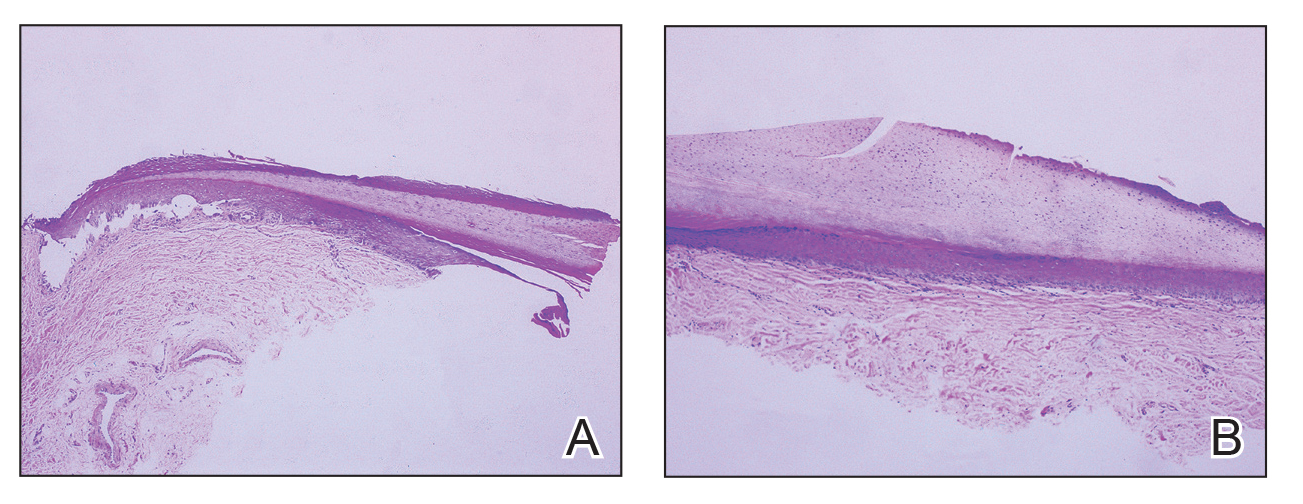

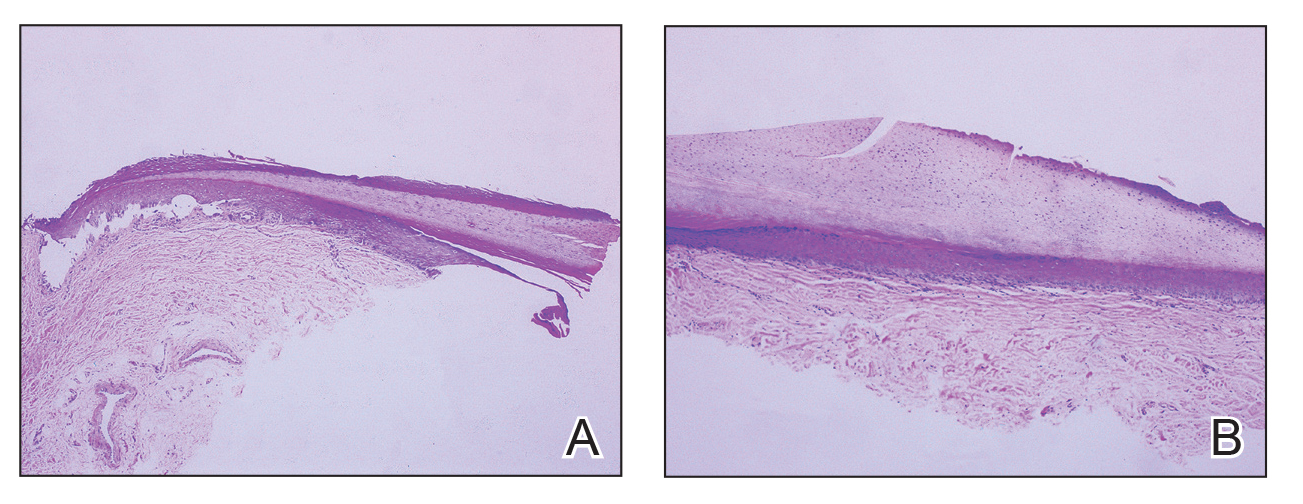

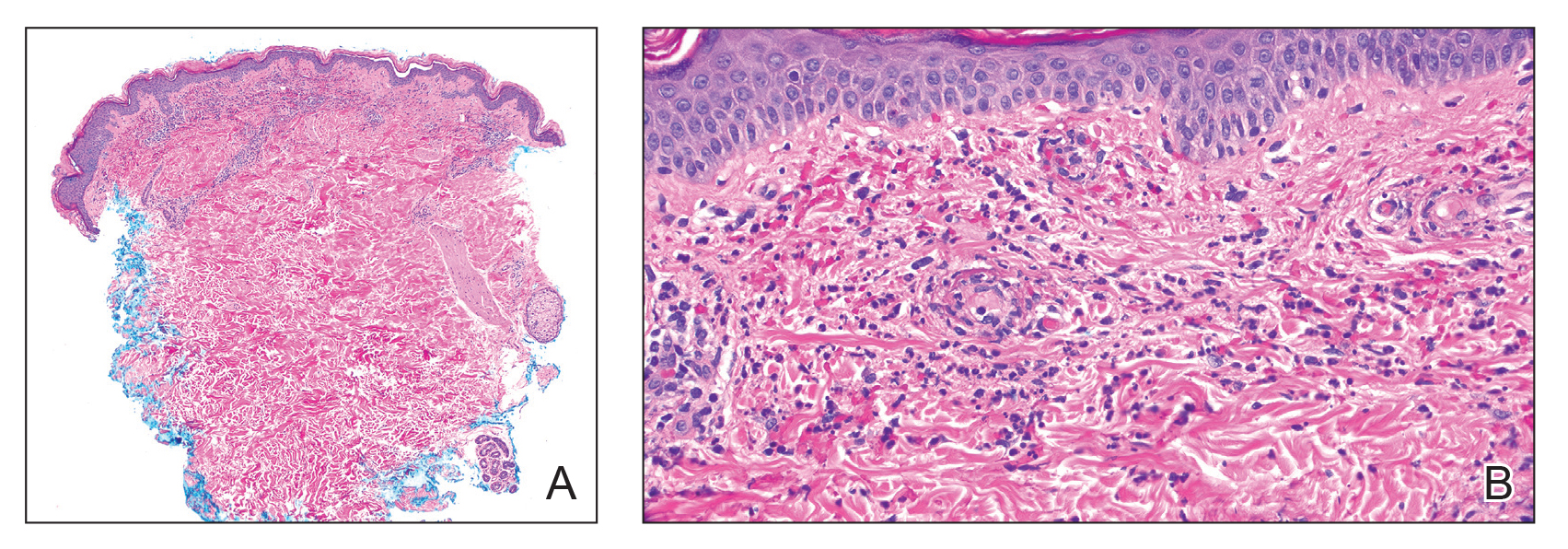

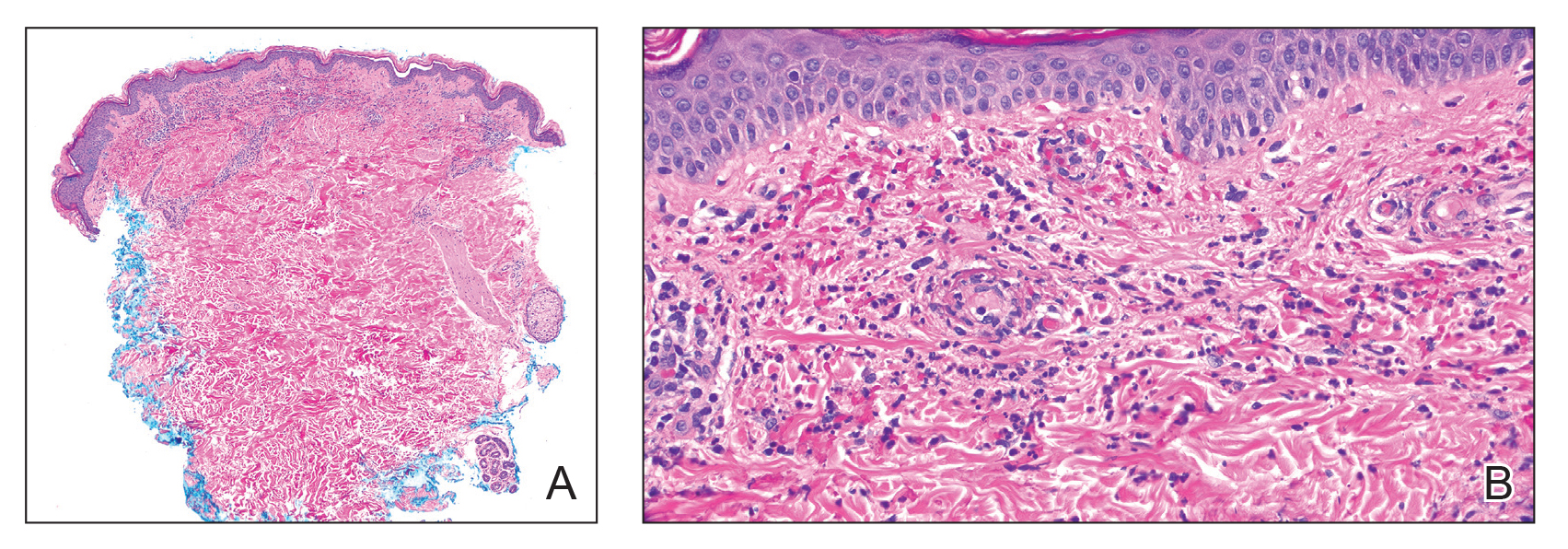

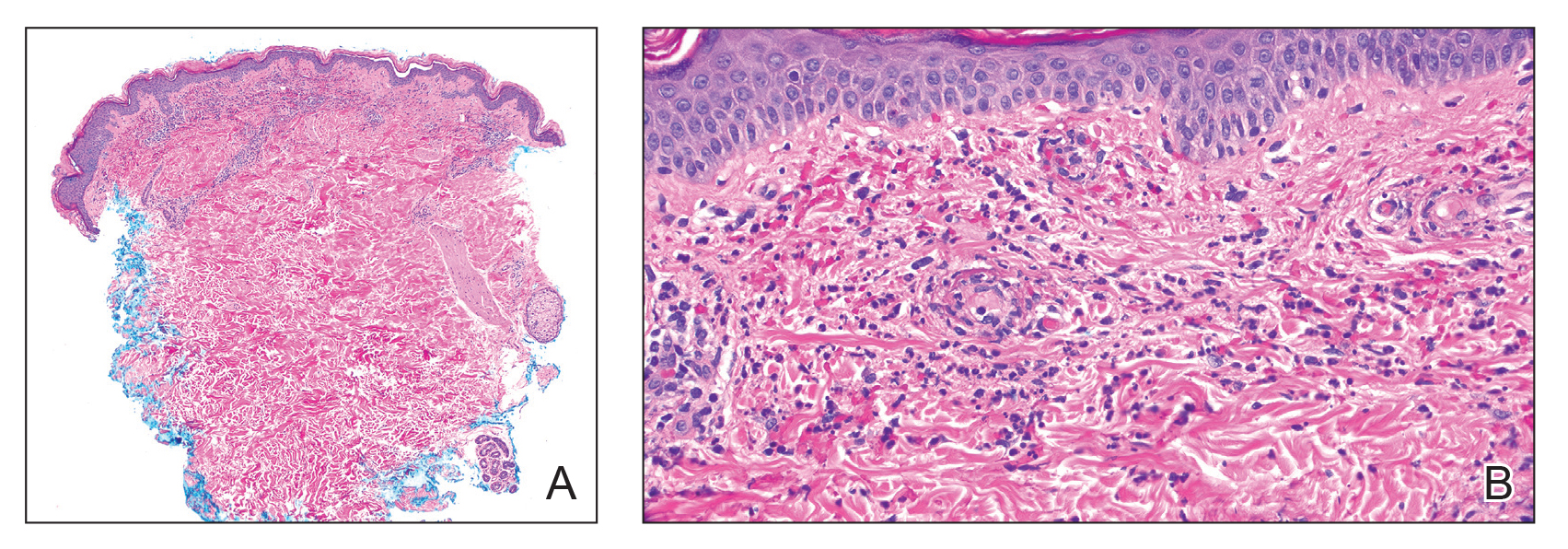

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

Practice Gap

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

Practice Gap

Longitudinal melanonychia (LM) is characterized by the presence of a dark brown, longitudinal, pigmented band on the nail unit, often caused by melanocytic activation or melanocytic hyperplasia in the nail matrix. Distinguishing between benign and early malignant LM is crucial due to their similar clinical presentations.1 Hence, surgical excision of the pigmented nail matrix followed by histopathologic examination is a common procedure aimed at managing LM and reducing the risk for delayed diagnosis of subungual melanoma.

Tangential matrix excision combined with the nail window technique has emerged as a common and favored surgical strategy for managing LM.2 This method is highly valued for its ability to minimize the risk for severe permanent nail dystrophy and effectively reduce postsurgical pigmentation recurrence.

The procedure begins with the creation of a matrix window along the lateral edge of the pigmented band followed by 1 lateral incision carefully made on each side of the nail fold. This meticulous approach allows for the complete exposure of the pigmented lesion. Subsequently, the nail fold is separated from the dorsal surface of the nail plate to facilitate access to the pigmented nail matrix. Finally, the target pigmented area is excised using a scalpel.

Despite the recognized efficacy of this procedure, challenges do arise, particularly when the width of the pigmented matrix lesion is narrow. Holding the scalpel horizontally to ensure precise excision can prove to be demanding, leading to difficulty achieving complete lesion removal and obtaining the desired cosmetic outcomes. As such, there is a clear need to explore alternative tools that can effectively address these challenges while ensuring optimal surgical outcomes for patients with LM. We propose the use of the customized dermal curette.

The Technique

An improved curette tool is a practical solution for complete removal of the pigmented nail matrix. This enhanced instrument is crafted from a sterile disposable dermal curette with its top flattened using a needle holder(Figure 1). Termed the customized dermal curette, this device is a simple yet accurate tool for the precise excision of pigmented lesions within the nail matrix. Importantly, it offers versatility by accommodating different widths of pigmented lesions through the availability of various sizes of dermal curettes (Figure 2).

Histopathologically, we have found that the scalpel technique may lead to variable tissue removal, resulting in differences in tissue thickness, fragility, and completeness (Figure 3A). Conversely, the customized dermal curette consistently provides more accurate tissue excision, resulting in uniform tissue thickness and integrity (Figure 3B).

Practice Implications

Compared to the traditional scalpel, this modified tool offers distinct advantages. Specifically, the customized dermal curette provides enhanced maneuverability and control during the procedure, thereby improving the overall efficacy of the excision process. It also offers a more accurate approach to completely remove pigmented bands, which reduces the risk for postoperative recurrence. The simplicity, affordability, and ease of operation associated with customized dermal curettes holds promise as an effective alternative for tissue shaving, especially in cases involving narrow pigmented matrix lesions, thereby addressing a notable practice gap and enhancing patient care.

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

- Tan WC, Wang DY, Seghers AC, et al. Should we biopsy melanonychia striata in Asian children? a retrospective observational study. Pediatr Dermatol. 2019;36:864-868. doi:10.1111/pde.13934

- Zhou Y, Chen W, Liu ZR, et al. Modified shave surgery combined with nail window technique for the treatment of longitudinal melanonychia: evaluation of the method on a series of 67 cases. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2019;81:717-722. doi:10.1016/j.jaad.2019.03.065

Slowly Enlarging Nodule on the Neck

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

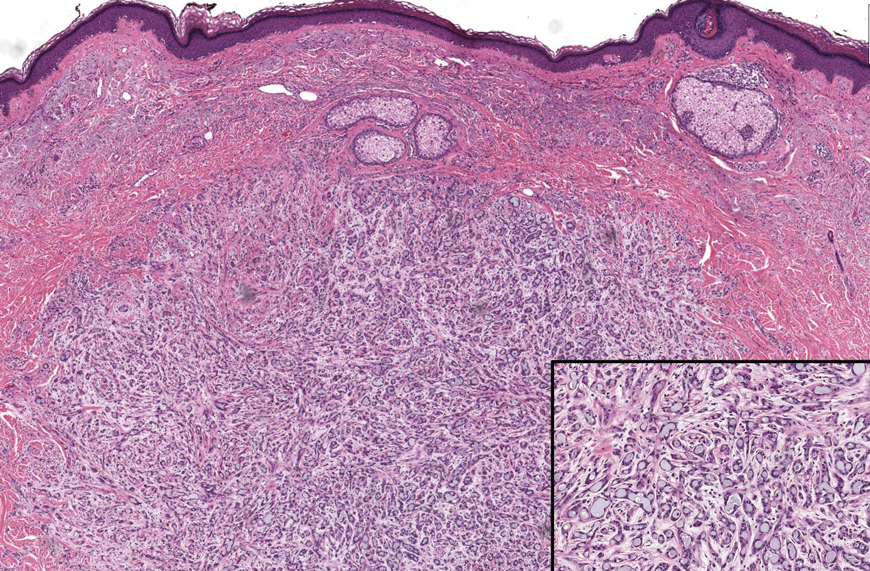

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

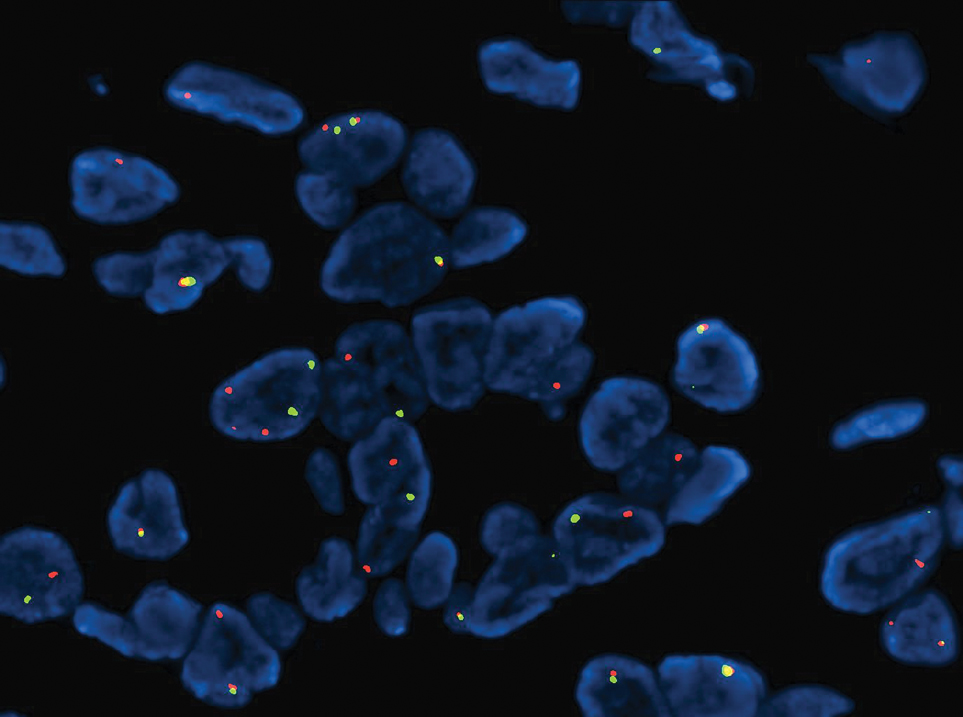

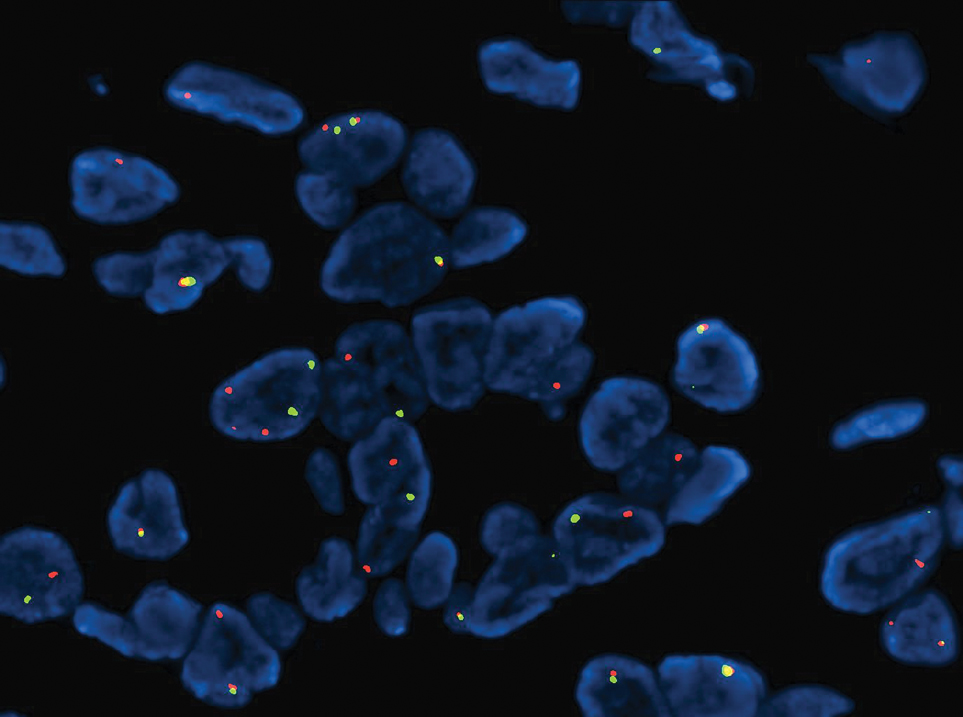

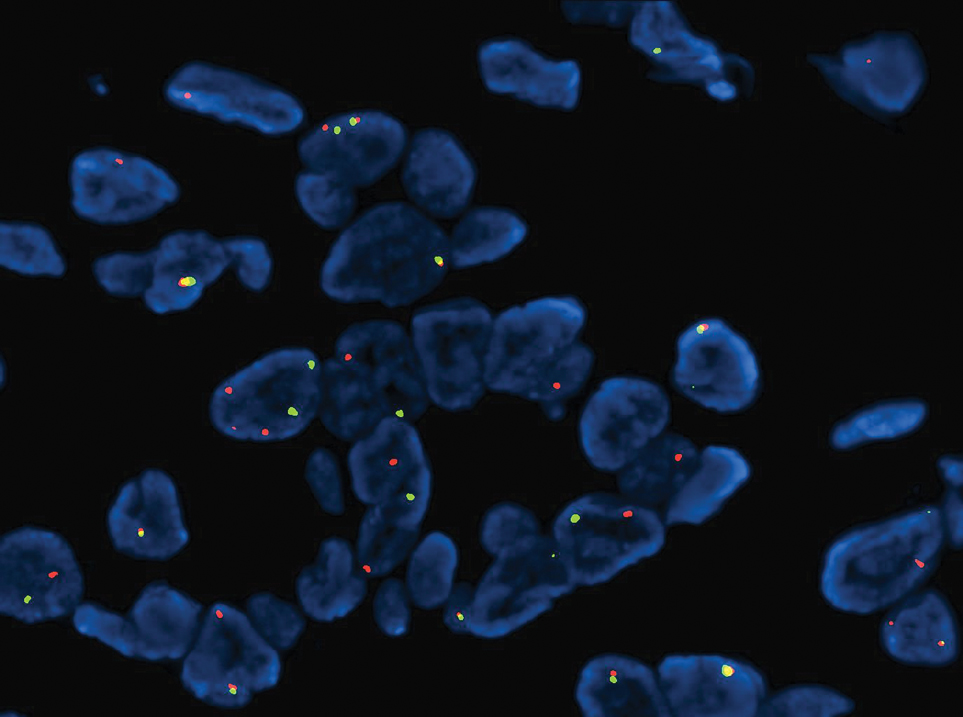

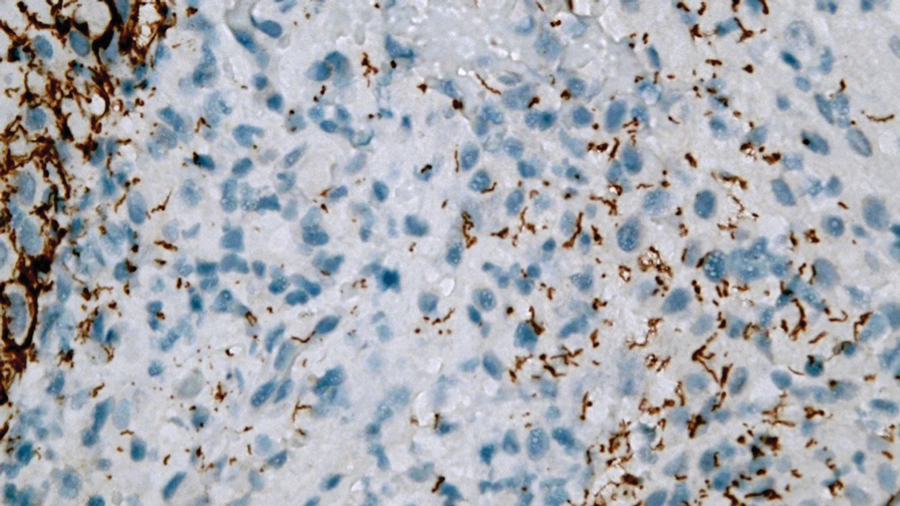

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

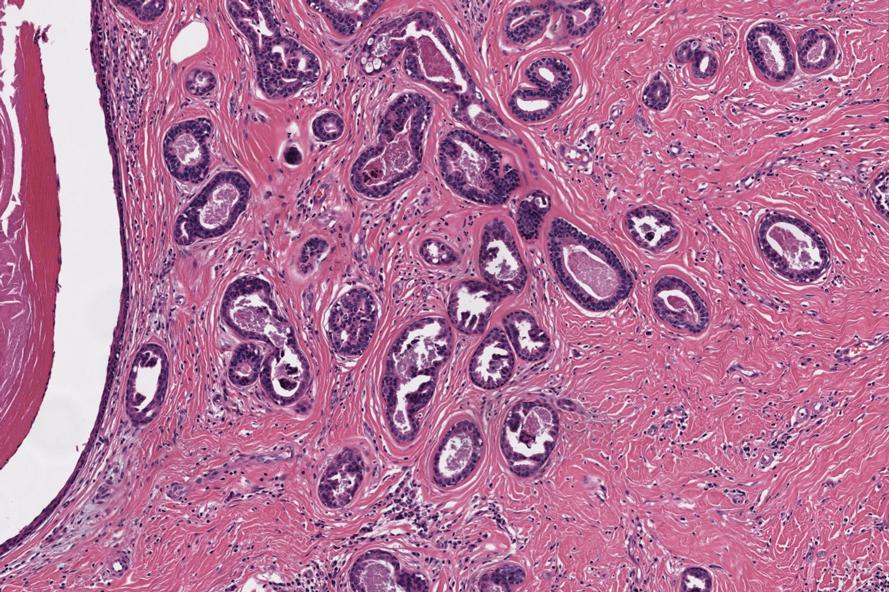

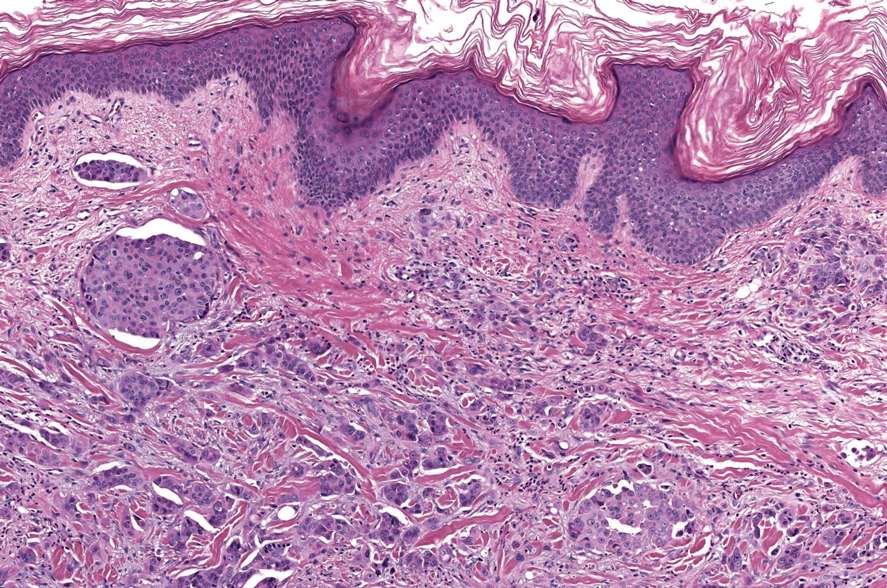

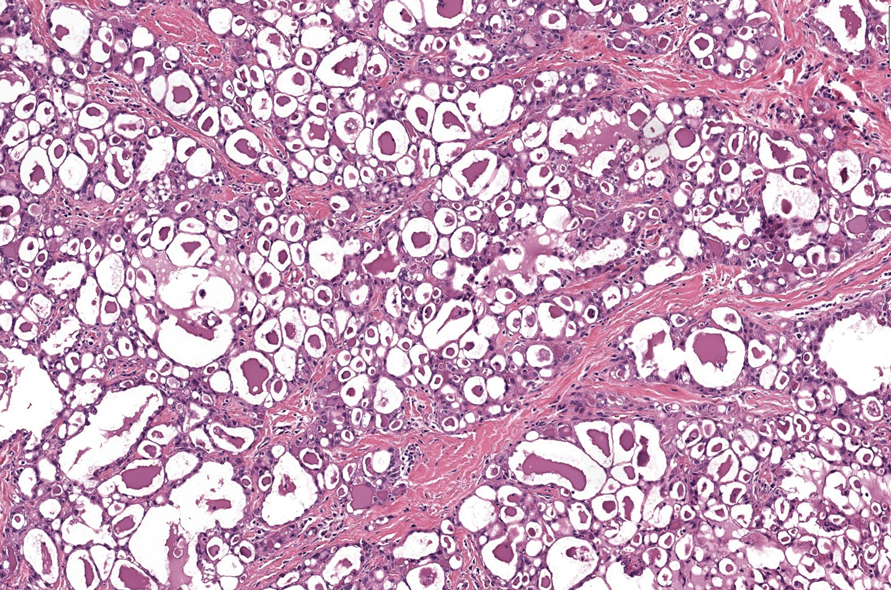

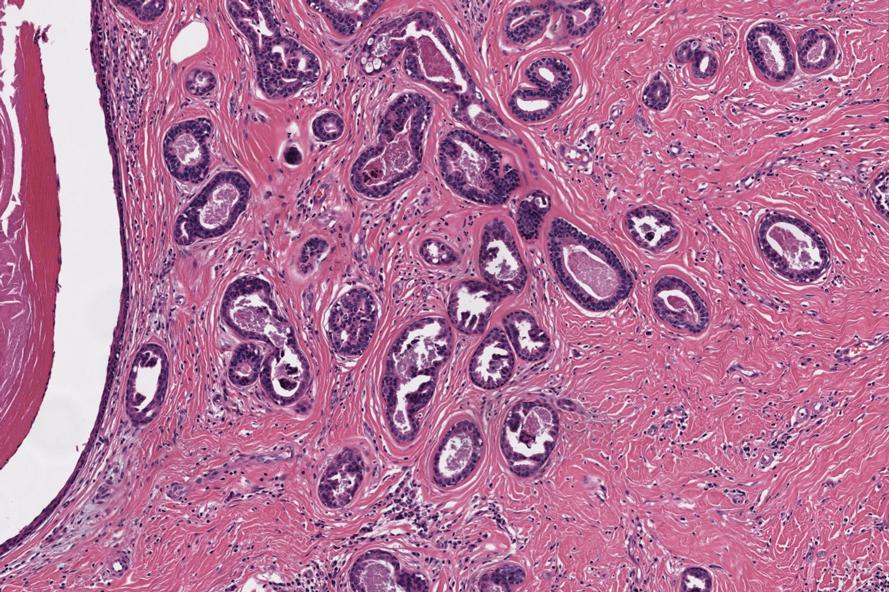

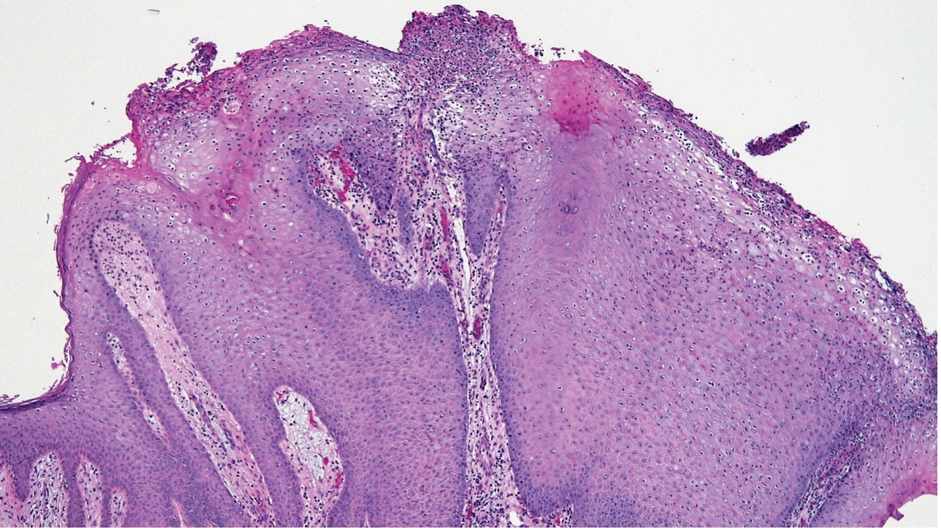

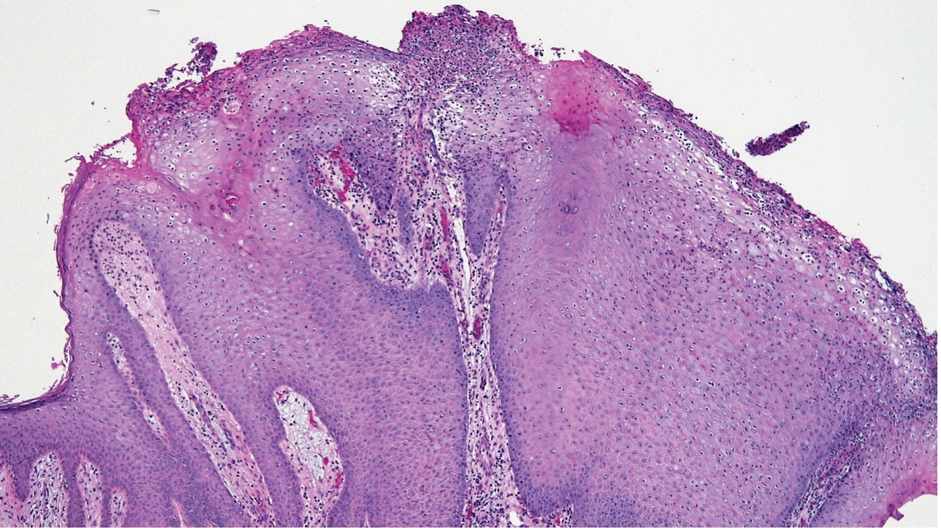

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

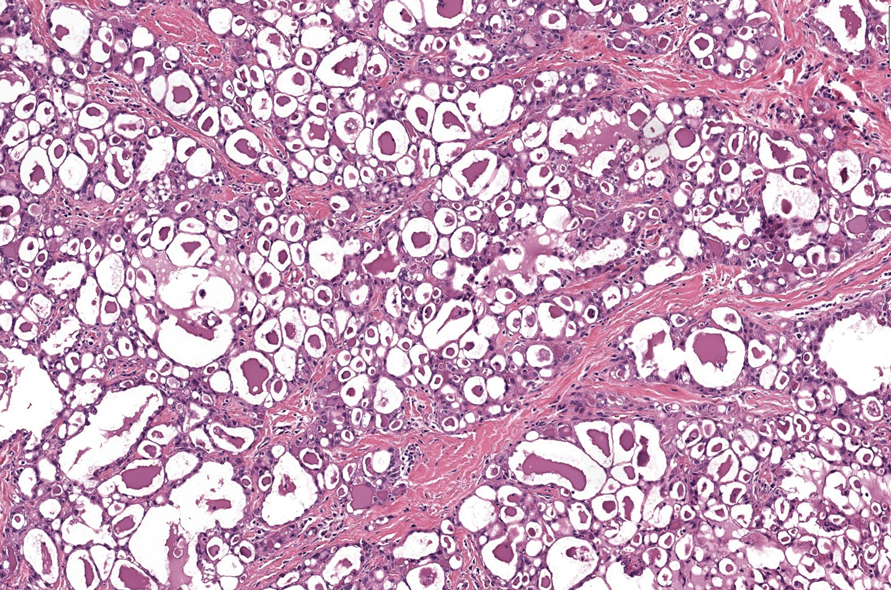

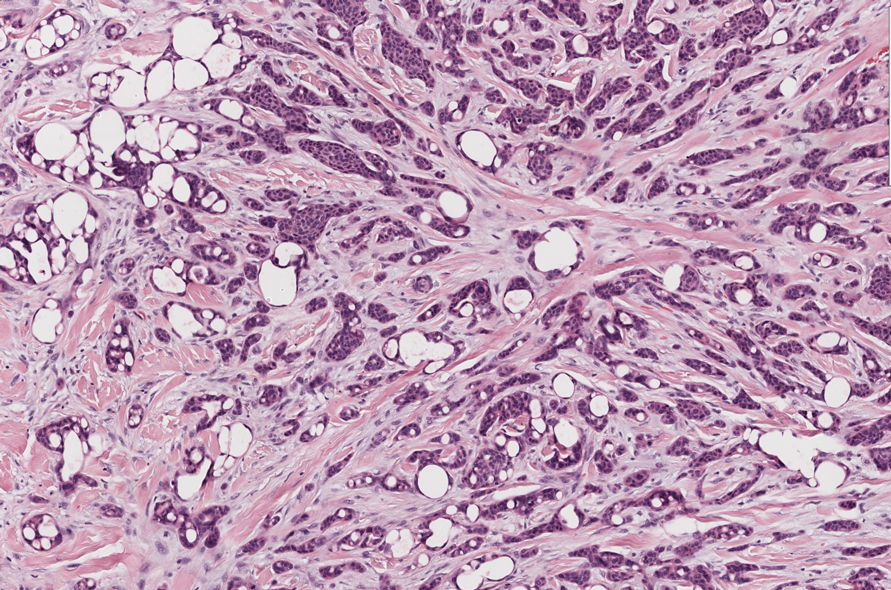

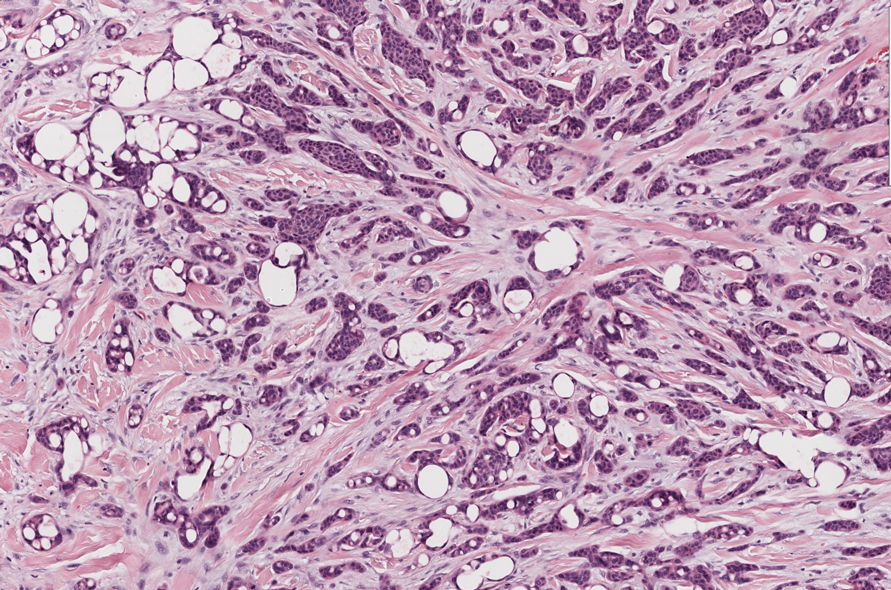

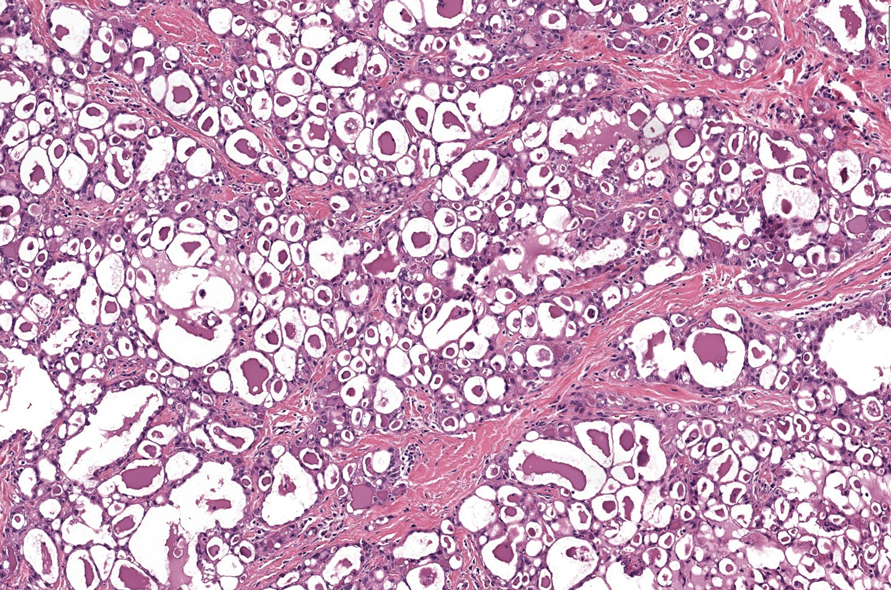

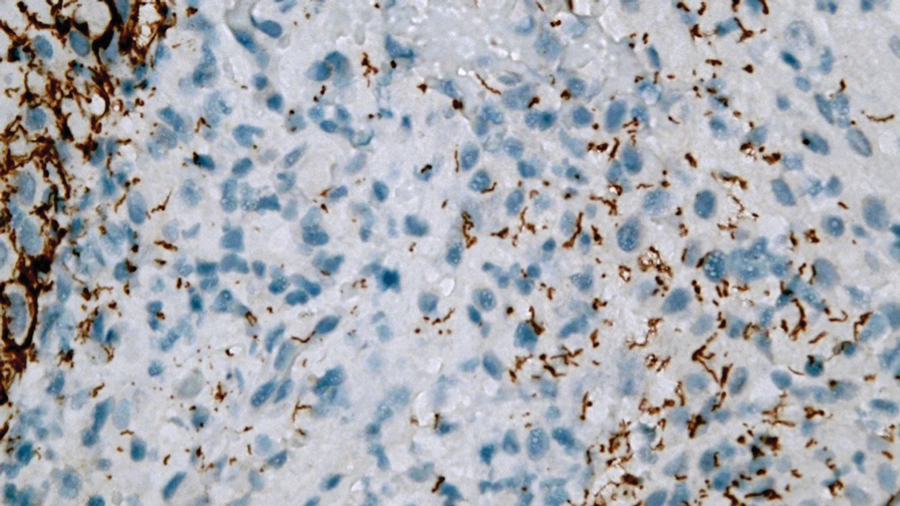

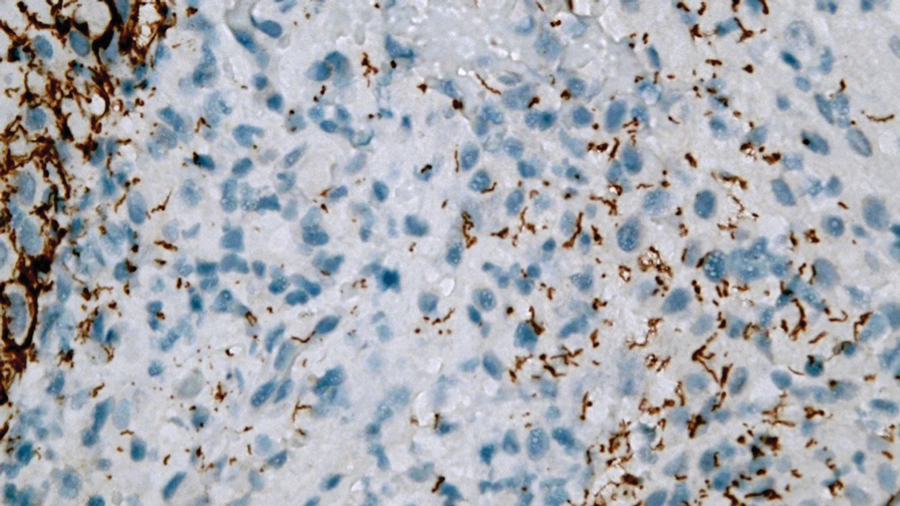

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

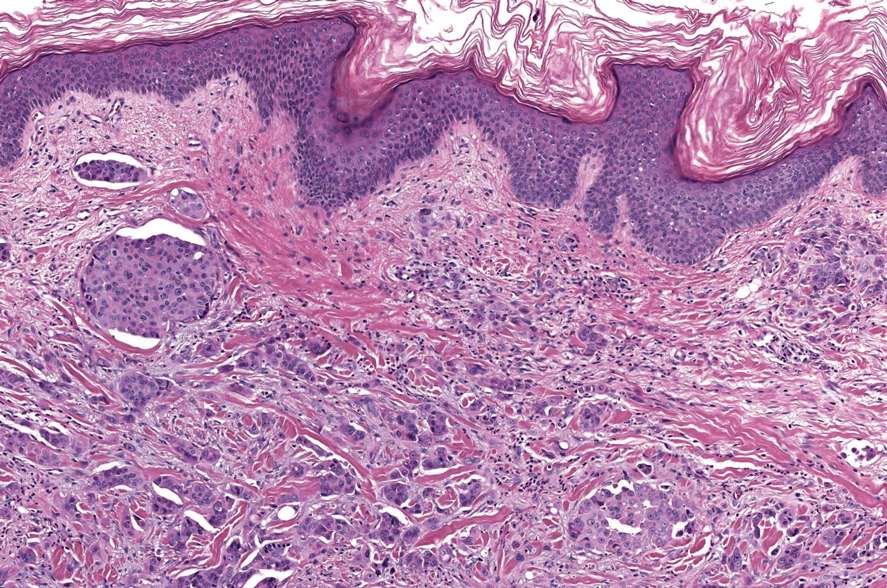

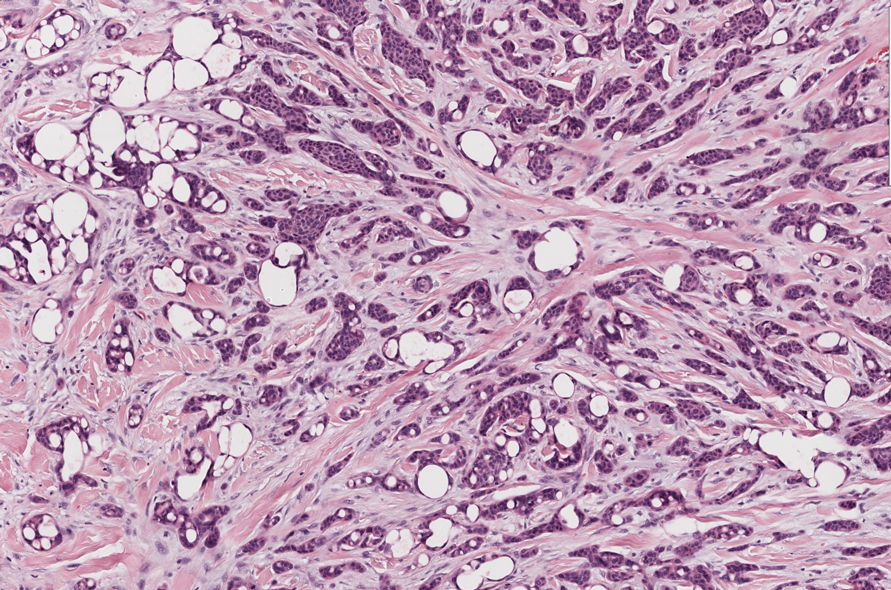

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

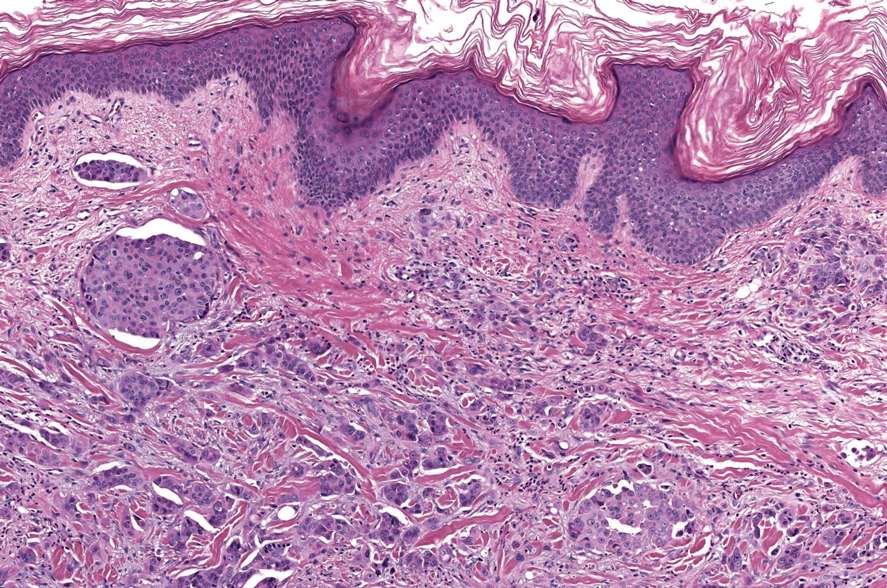

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

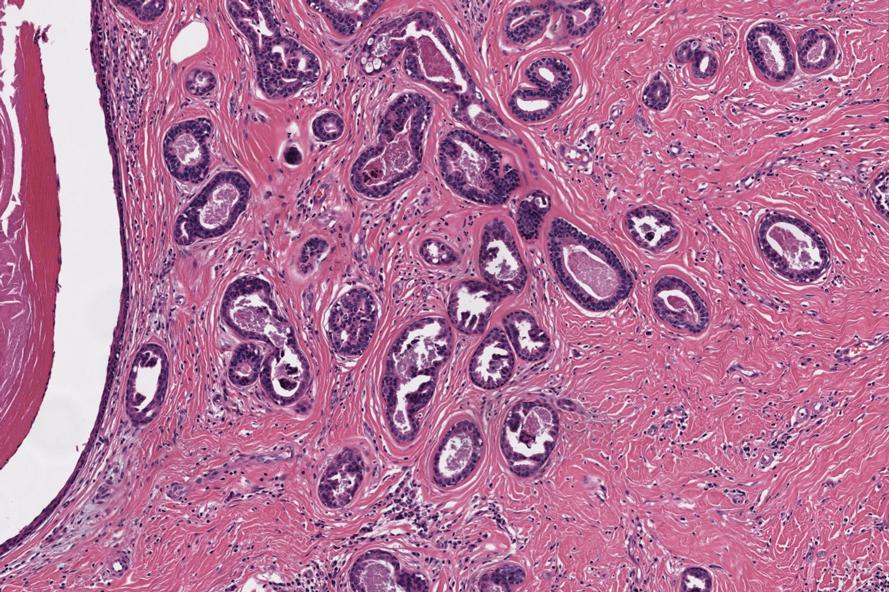

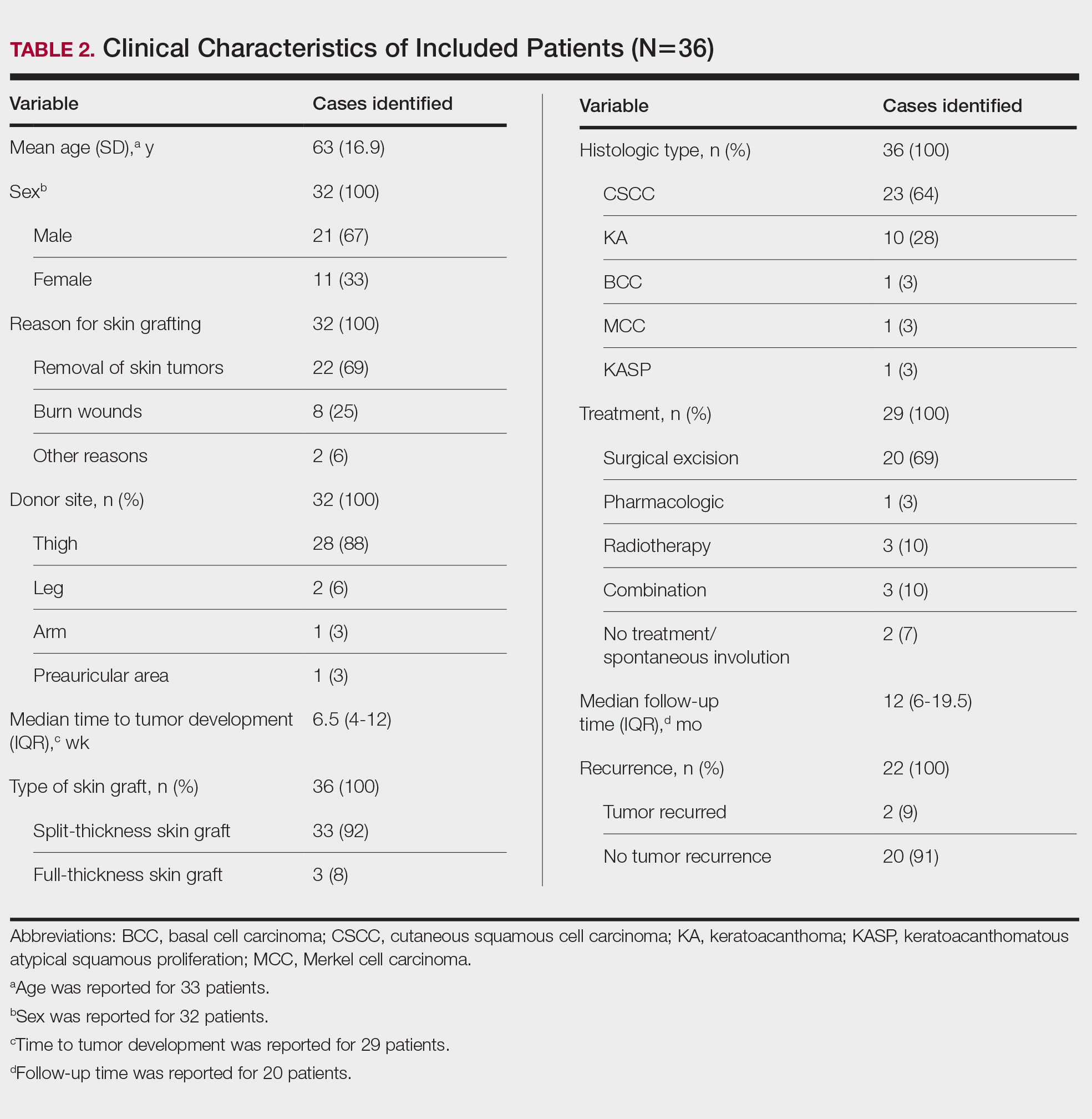

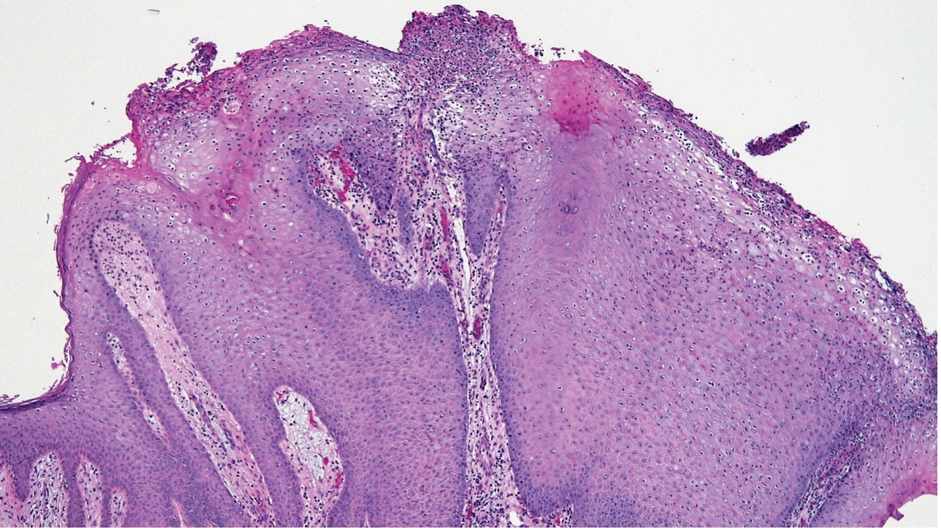

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

The Diagnosis: Microsecretory Adenocarcinoma

Microscopically, the tumor was relatively well circumscribed but had irregular borders. It consisted of microcysts and tubules lined by flattened to plump eosinophilic cells with mildly enlarged nuclei and intraluminal basophilic secretions. Peripheral lymphocytic aggregates also were seen in the mid and deep reticular dermis. Tumor necrosis, lymphovascular invasion, and notable mitotic activity were absent. Immunohistochemistry was diffusely positive for cytokeratin (CK) 7 and CK5/6. Occasional tumor cells showed variable expression of alpha smooth muscle actin, S-100 protein, and p40 and p63 antibodies. Immunohistochemistry was negative for CK20; GATA binding protein 3; MYB proto-oncogene, transcription factor; and insulinoma-associated protein 1. A dual-color, break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization probe identified a rearrangement of the SS18 (SYT) gene locus on chromosome 18. The nodule was excised with clear surgical margins, and the patient had no evidence of recurrent disease or metastasis at 2-year follow-up.

In recent years, there has been a growing recognition of the pivotal role played by gene fusions in driving oncogenesis, encompassing a diverse range of benign and malignant cutaneous neoplasms. These investigations have shed light on previously unknown mechanisms and pathways contributing to the pathogenesis of these neoplastic conditions, offering invaluable insights into their underlying biology. As a result, our ability to classify and diagnose these cutaneous tumors has improved. A notable example of how our current understanding has evolved is the discovery of the new cutaneous adnexal tumor microsecretory adenocarcinoma (MSA). Initially described by Bishop et al1 in 2019 as predominantly occurring in the intraoral minor salivary glands, rare instances of primary cutaneous MSA involving the head and neck regions also have been reported.2 Microsecretory adenocarcinoma represents an important addition to the group of fusion-driven tumors with both salivary gland and cutaneous adnexal analogues, characterized by a MEF2C::SS18 gene fusion. This entity is now recognized as a group of cutaneous adnexal tumors with distinct gene fusions, including both relatively recently discovered entities (eg, secretory carcinoma with NTRK fusions) and previously known entities with newly identified gene fusions (eg, poroid neoplasms with NUTM1, YAP1, or WWTR1 fusions; hidradenomatous neoplasms with CRTC1::MAML2 fusions; and adenoid cystic carcinoma with MYB, MYBL1, and/or NFIB rearrangements).3

Microsecretory adenocarcinoma exhibits a high degree of morphologic consistency, characterized by a microcystic-predominant growth pattern, uniform intercalated ductlike tumor cells with attenuated eosinophilic to clear cytoplasm, monotonous oval hyperchromatic nuclei with indistinct nucleoli, abundant basophilic luminal secretions, and a variably cellular fibromyxoid stroma. It also shows rounded borders with subtle infiltrative growth. Occasionally, pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia, tumor-associated lymphoid proliferation, or metaplastic bone formation may accompany MSA. Perineural invasion is rare, necrosis is absent, and mitotic rates generally are low, contributing to its distinctive histopathologic features that aid in accurate diagnosis and differentiation from other entities. Immunohistochemistry reveals diffuse positivity for CK7 and patchy to diffuse expression of S-100 in tumor cells as well as variable expression of p40 and p63. Highly specific SS18 gene translocations at chromosome 18q are useful for diagnosing MSA when found alongside its characteristic appearance, and SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization can serve reliably as an accurate diagnostic method (Figure 1).4 Our case illustrates how molecular analysis assists in distinguishing MSA from other cutaneous adnexal tumors, exemplifying the power of our evolving understanding in refining diagnostic accuracy and guiding targeted therapies in clinical practice.

The differential diagnosis of MSA includes tubular adenoma, secretory carcinoma, cribriform tumor (previously carcinoma), and metastatic adenocarcinoma. Tubular adenoma is a rare benign neoplasm that predominantly affects females and can manifest at any age in adulthood. It typically manifests as a slow-growing, occasionally pedunculated nodule, often measuring less than 2 cm. Although it most commonly manifests on the scalp, tubular adenoma also may arise in diverse sites such as the face, axillae, lower extremities, or genitalia.

Notably, scalp lesions often are associated with nevus sebaceus of Jadassohn or syringocystadenoma papilliferum. Microscopically, tubular adenoma is well circumscribed within the dermis and may extend into the subcutis in some cases. Its distinctive appearance consists of variably sized tubules lined by a double or multilayered cuboidal to columnar epithelium, frequently displaying apocrine decapitation secretion (Figure 2). Cystic changes and intraluminal papillae devoid of true fibrovascular cores frequently are observed. Immunohistochemically, luminal epithelial cells express epithelial membrane antigen and carcinoembryonic antigen, while the myoepithelial layer expresses smooth muscle markers, p40, and S-100 protein. BRAF V600E mutation can be detected using immunohistochemistry, with excellent sensitivity and specificity using the anti-BRAF V600E antibody (clone VE1).5 Distinguishing tubular adenoma from MSA is achievable by observing its larger, more variable tubules, along with the consistent presence of a peripheral myoepithelial layer.

Secretory carcinoma is recognized as a low-grade gene fusion–driven carcinoma that primarily arises in salivary glands (both major and minor), with occasional occurrences in the breast and extremely rare instances in other locations such as the skin, thyroid gland, and lung.6 Although the axilla is the most common cutaneous site, diverse locations such as the neck, eyelids, extremities, and nipples also have been documented. Secretory carcinoma affects individuals across a wide age range (13–71 years).6 The hallmark tumors exhibit densely packed, sievelike microcystic glands and tubular spaces filled with abundant eosinophilic intraluminal secretions (Figure 3). Additionally, morphologic variants, such as predominantly papillary, papillary-cystic, macrocystic, solid, partially mucinous, and mixed-pattern neoplasms, have been described. Secretory carcinoma shares certain features with MSA; however, it is distinguished by the presence of pronounced eosinophilic secretions, plump and vacuolated cytoplasm, and a less conspicuous fibromyxoid stroma. Immunohistochemistry reveals tumor cells that are positive for CK7, SOX-10, S-100, mammaglobin, MUC4, and variably GATA-3. Genetically, secretory carcinoma exhibits distinct characteristics, commonly showing the ETV6::NTRK3 fusion, detectable through molecular techniques or pan-TRK immunohistochemistry, while RET fusions and other rare variants are less frequent.7

In 1998, Requena et al8 introduced the concept of primary cutaneous cribriform carcinoma. Despite initially being classified as a carcinoma, the malignant potential of this tumor remains uncertain. Consequently, the term cribriform tumor now has become the preferred terminology for denoting this rare entity.9 Primary cutaneous cribriform tumors are observed more commonly in women and typically affect individuals aged 20 to 55 years (mean, 44 years). Predominant locations include the upper and lower extremities, especially the thighs, knees, and legs, with additional cases occurring on the head and trunk. Microscopically, cribriform tumor is characterized by a partially circumscribed, unencapsulated dermal nodule composed of round or oval nuclei displaying hyperchromatism and mild pleomorphism. The defining aspect of its morphology revolves around interspersed small round cavities that give rise to the hallmark cribriform pattern (Figure 4). Although MSA occasionally may exhibit a cribriform architectural pattern, it typically lacks the distinctive feature of thin, threadlike, intraluminal bridging strands observed in cribriform tumors. Similarly, luminal cells within the cribriform tumor express CK7 and exhibit variable S-100 expression. It is recognized as an indolent neoplasm with uncertain malignant potential.

The histopathologic features of metastatic carcinomas can overlap with those of primary cutaneous tumors, particularly adnexal neoplasms.10 However, several key features can aid in the differentiation of cutaneous metastases, including a dermal-based growth pattern with or without subcutaneous involvement, the presence of multiple lesions, and the occurrence of lymphovascular invasion (Figure 5). Conversely, features that suggest a primary cutaneous adnexal neoplasm include the presence of superimposed in situ disease, carcinoma developing within a benign adnexal neoplasm, and notable stromal and/or vascular hyalinization within benign-appearing areas. In some cases, it can be difficult to determine the primary site of origin of a metastatic carcinoma to the skin based on morphologic features alone. In these cases, immunohistochemistry can be helpful. The most cost-effective and time-efficient approach to accurate diagnosis is to obtain a comprehensive clinical history. If there is a known history of cancer, a small panel of organ-specific immunohistochemical studies can be performed to confirm the diagnosis. If there is no known history, an algorithmic approach can be used to identify the primary site of origin. In all circumstances, it cannot be stressed enough that acquiring a thorough clinical history before conducting any diagnostic examinations is paramount.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

- Bishop JA, Weinreb I, Swanson D, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma: a novel salivary gland tumor characterized by a recurrent MEF2C-SS18 fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2019;43:1023-1032.

- Bishop JA, Williams EA, McLean AC, et al. Microsecretory adenocarcinoma of the skin harboring recurrent SS18 fusions: a cutaneous analog to a newly described salivary gland tumor. J Cutan Pathol. 2023;50:134-139.

- Macagno N, Sohier Pierre, Kervarrec T, et al. Recent advances on immunohistochemistry and molecular biology for the diagnosis of adnexal sweat gland tumors. Cancers (Basel). 2022;14:476.

- Bishop JA, Koduru P, Veremis BM, et al. SS18 break-apart fluorescence in situ hybridization is a practical and effective method for diagnosing microsecretory adenocarcinoma of salivary glands. Head Neck Pathol. 2021;15:723-726.

- Liau JY, Tsai JH, Huang WC, et al. BRAF and KRAS mutations in tubular apocrine adenoma and papillary eccrine adenoma of the skin. Hum Pathol. 2018;73:59-65.

- Chang MD, Arthur AK, Garcia JJ, et al. ETV6 rearrangement in a case of mammary analogue secretory carcinoma of the skin. J Cutan Pathol. 2016;43:1045-1049.

- Skalova A, Baneckova M, Thompson LDR, et al. Expanding the molecular spectrum of secretory carcinoma of salivary glands with a novel VIM-RET fusion. Am J Surg Pathol. 2020;44:1295-1307.

- Requena L, Kiryu H, Ackerman AB. Neoplasms With Apocrine Differentiation. Lippencott-Raven; 1998.

- Kazakov DV, Llamas-Velasco M, Fernandez-Flores A, et al. Cribriform tumour (previously carcinoma). In: WHO Classification of Tumours: Skin Tumours. 5th ed. International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024.

- Habaermehl G, Ko J. Cutaneous metastases: a review and diagnostic approach to tumors of unknown origin. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2019;143:943-957.

A 74-year-old man presented with an asymptomatic nodule on the left neck measuring approximately 2 cm. An excisional biopsy was obtained for histopathologic evaluation.

Epidermal Tumors Arising on Donor Sites From Autologous Skin Grafts: A Systematic Review

Skin grafting is a surgical technique used to cover skin defects resulting from the removal of skin tumors, ulcers, or burn injuries.1-3 Complications can occur at both donor and recipient sites and may include bleeding, hematoma/seroma formation, postoperative pain, infection, scarring, paresthesia, skin pigmentation, graft contracture, and graft failure.1,2,4,5 The development of epidermal tumors is not commonly reported among the complications of skin grafting; however, cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites during the postoperative period have been reported.6-12

We performed a systematic review of the literature for cases of epidermal tumor development on skin graft donor sites in patients undergoing autologous skin graft surgery. We present the clinical characteristics of these cases and discuss the nature of these tumors.

Methods

Search Strategy and Study Selection—A literature search was conducted by 2 independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) for articles published before December 2022 in the following databases: MEDLINE/PubMed, Web of Science, Scopus, Cochrane Library, OpenGrey, Google Scholar, and WorldCat. Search terms included all possible combinations of the following: keratoacanthoma, molluscum sebaceum, basal cell carcinoma, squamous cell carcinoma, acanthoma, wart, Merkel cell carcinoma, verruca, Bowen disease, keratosis, skin cancer, cutaneous cancer, skin neoplasia, cutaneous neoplasia, and skin tumor. The literature search terms were selected based on the World Health Organization classification of skin tumors.13 Manual bibliography checks were performed on all eligible search results for possible relevant studies. Discrepancies were resolved through discussion and, if needed, mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). To be included, a study had to report a case(s) of epidermal tumor(s) that was confirmed by histopathology and arose on a graft donor site in a patient receiving autologous skin grafts for any reason. No language, geographic, or report date restrictions were set.

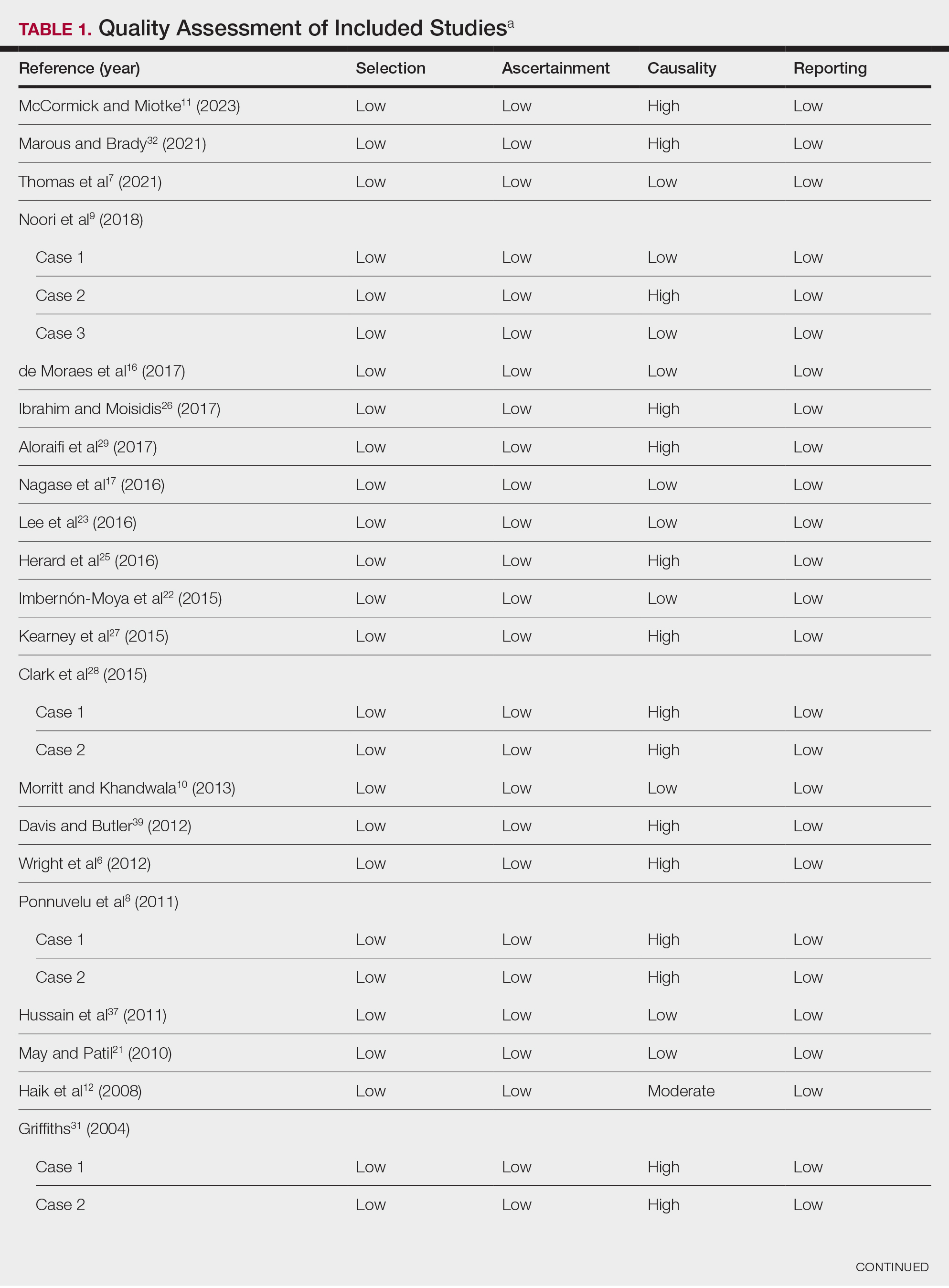

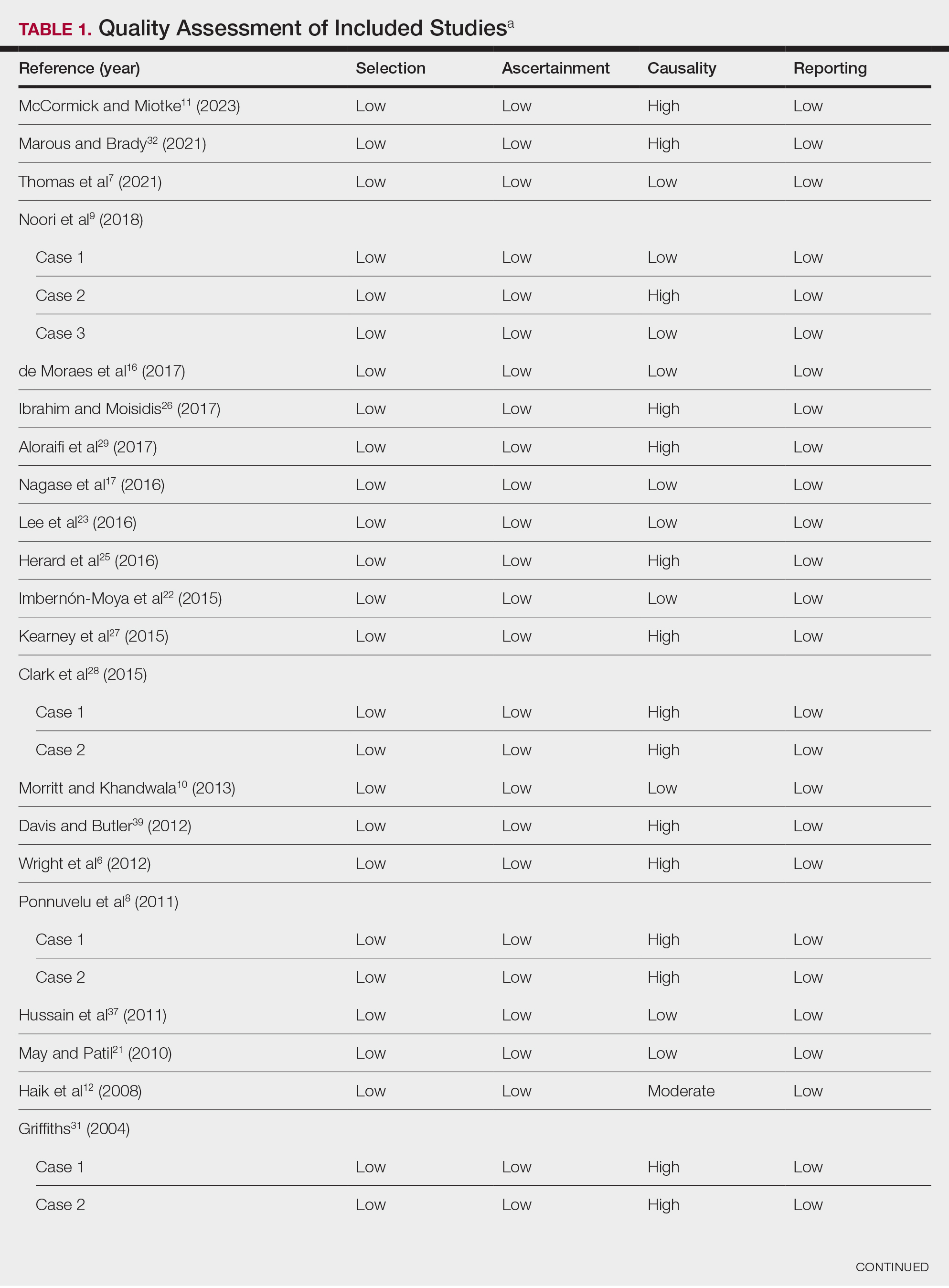

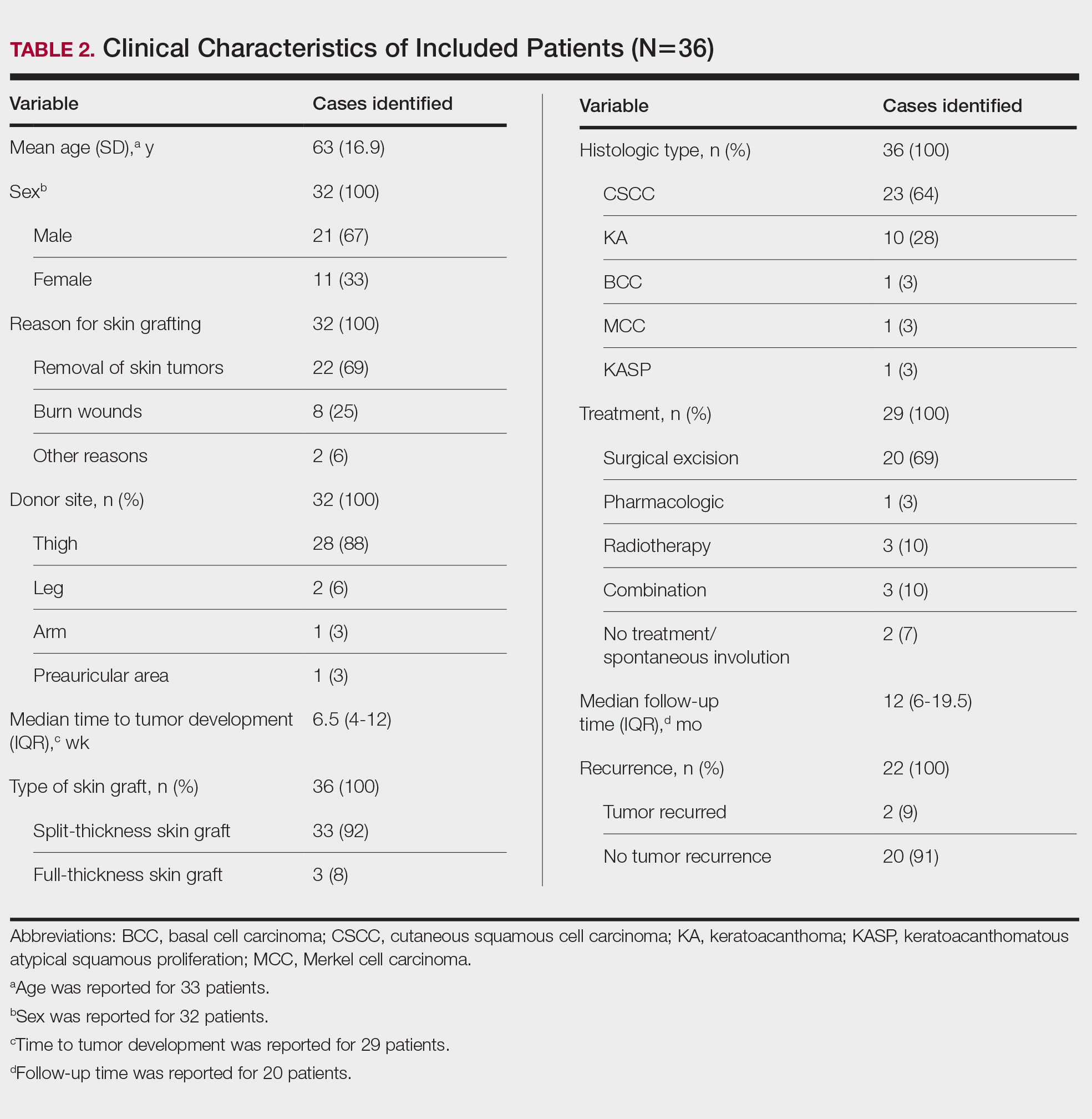

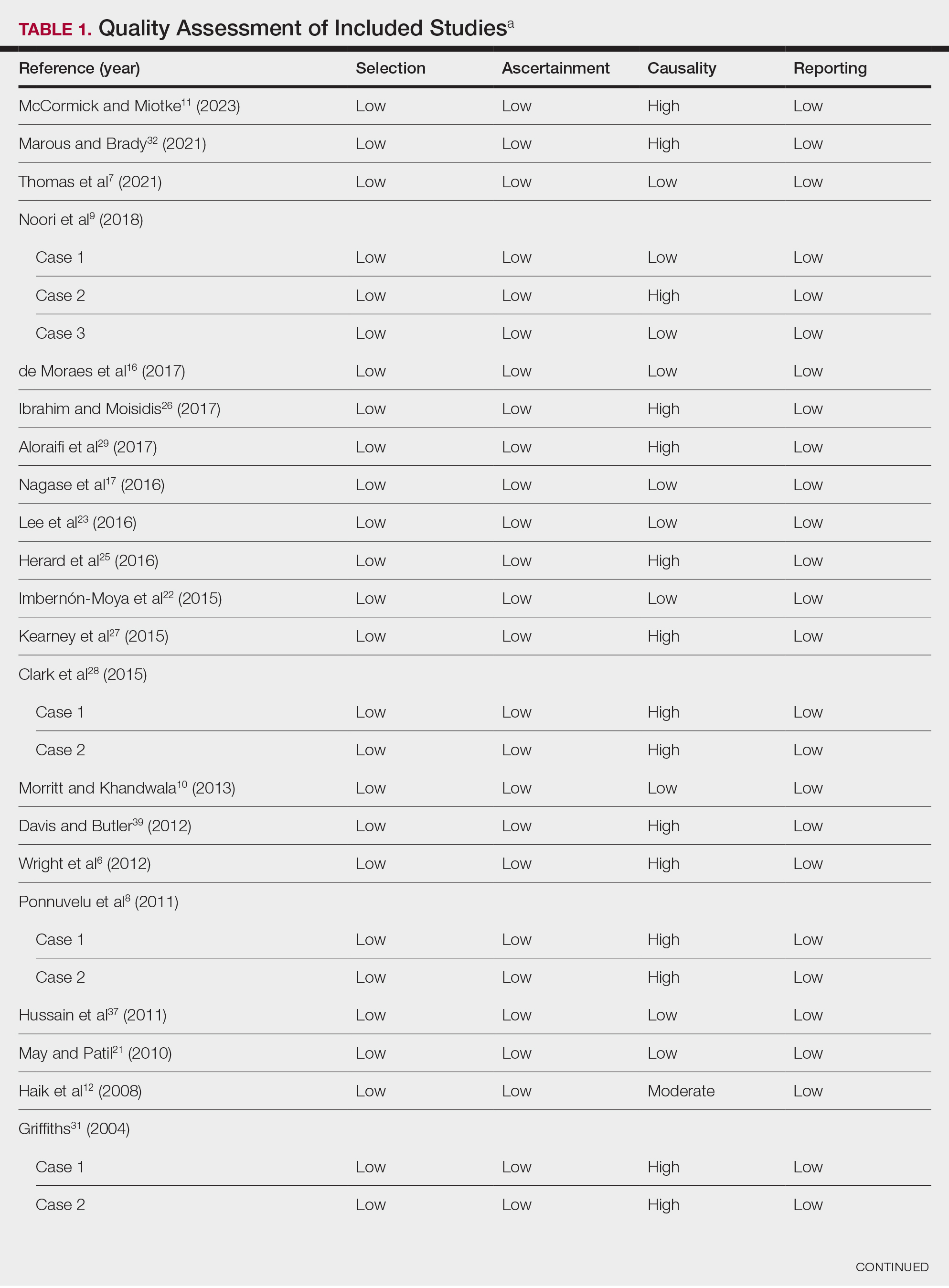

Data Extraction, Quality Assessment, and Statistical Analysis—We adhered to the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.14 Two independent researchers (Z.P. and V.P.) retrieved the data from the included studies. We have used the terms case and patient interchangeably, and 1 month was measured as 4 weeks for simplicity. Disagreements were resolved by discussion and mediation by a third researcher (N.C.). The quality of the included studies was assessed by 2 researchers (M.P. and V.P.) using the tool proposed by Murad et al.15

We used descriptive statistical analysis to analyze clinical characteristics of the included cases. We performed separate descriptive analyses based on the most frequently reported types of epidermal tumors and compared the differences between different groups using the Mann-Whitney U test, χ2 test, and Fisher exact test. The level of significance was set at P<.05. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS (version 29).

Results

Literature Search and Characteristics of Included Studies—The initial literature search identified 1378 studies, which were screened based on title and abstract. After removing duplicate and irrelevant studies and evaluating the full text of eligible studies, 31 studies (4 case series and 27 case reports) were included in the systematic review (Figure).6-12,16-39 Quality assessment of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

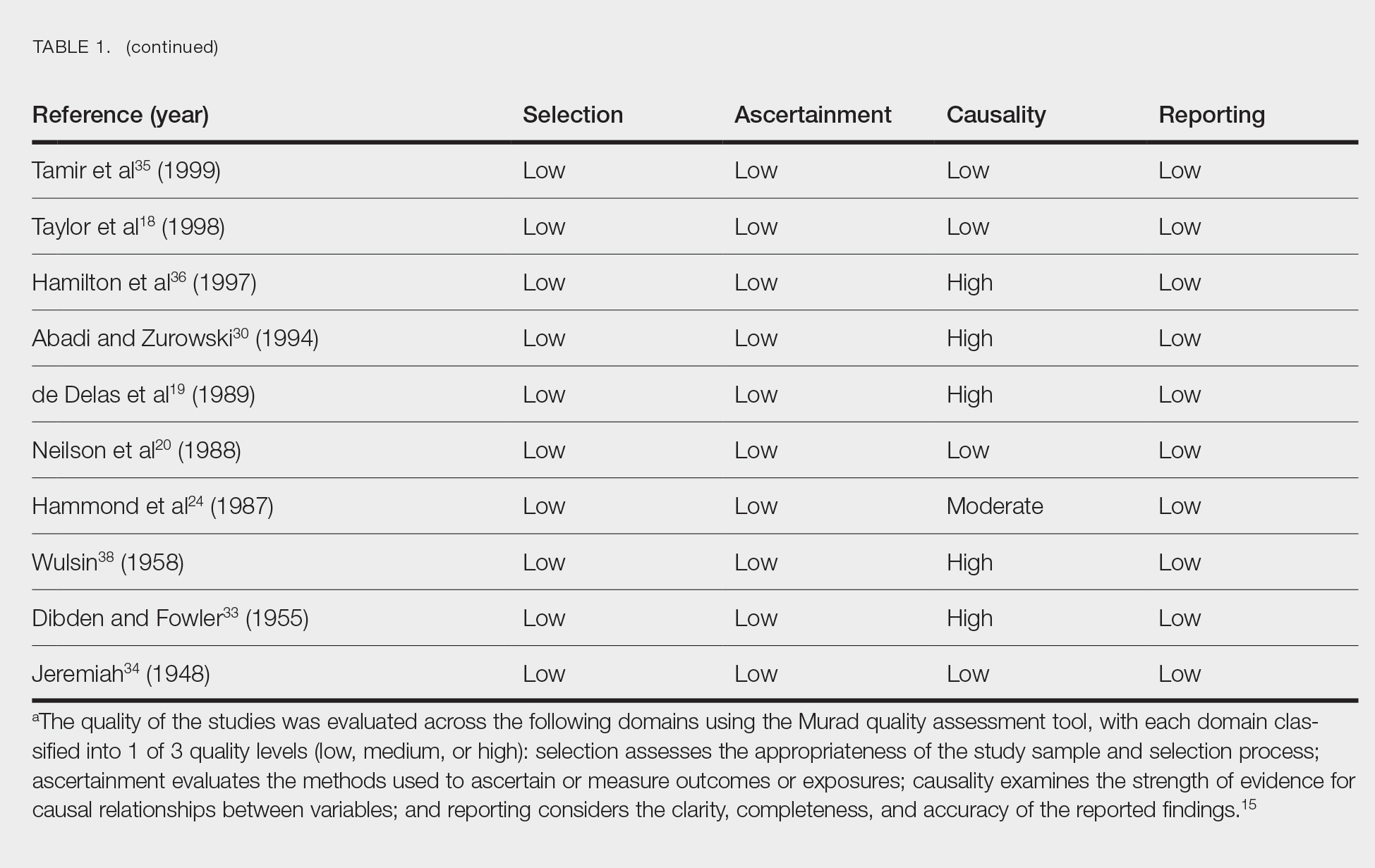

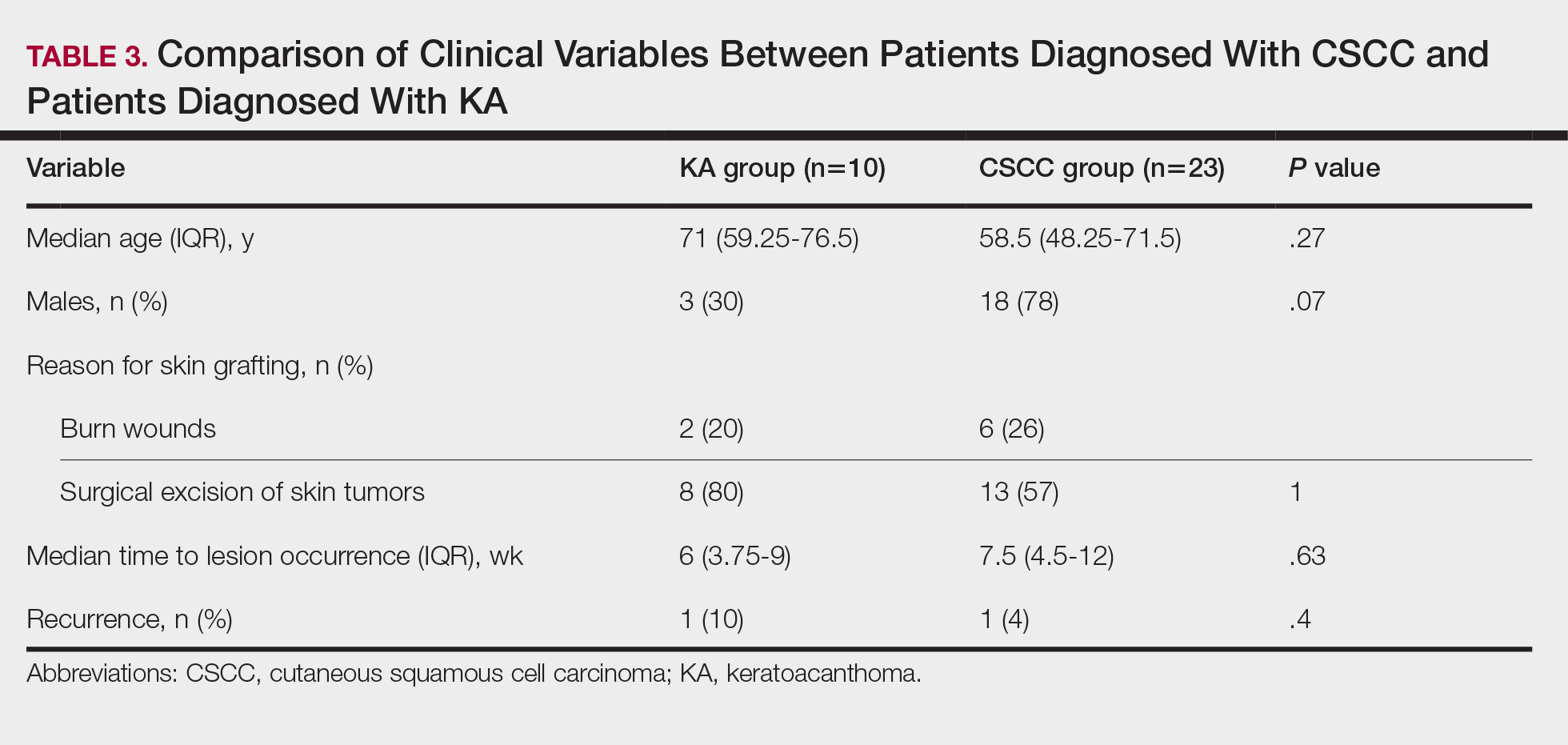

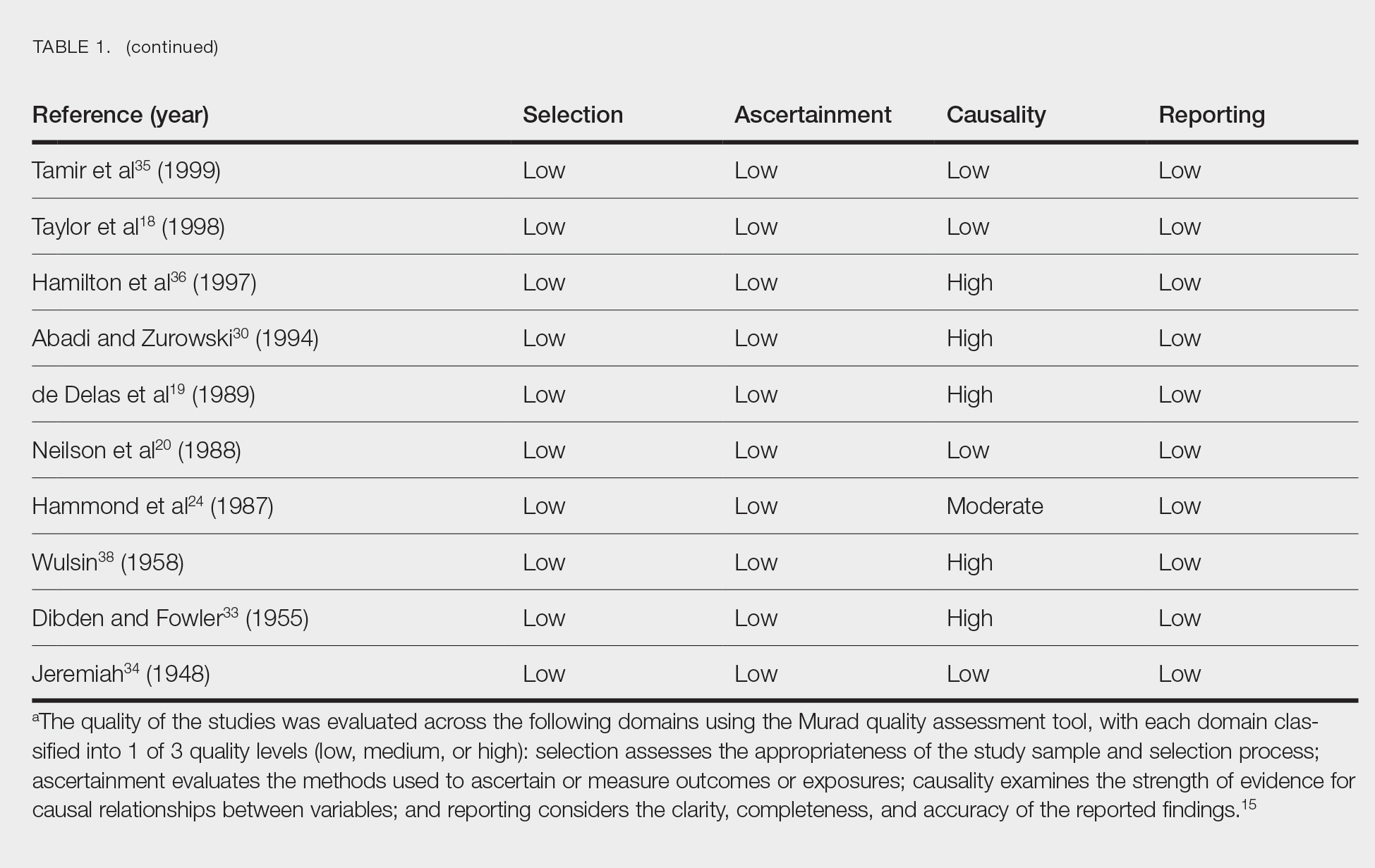

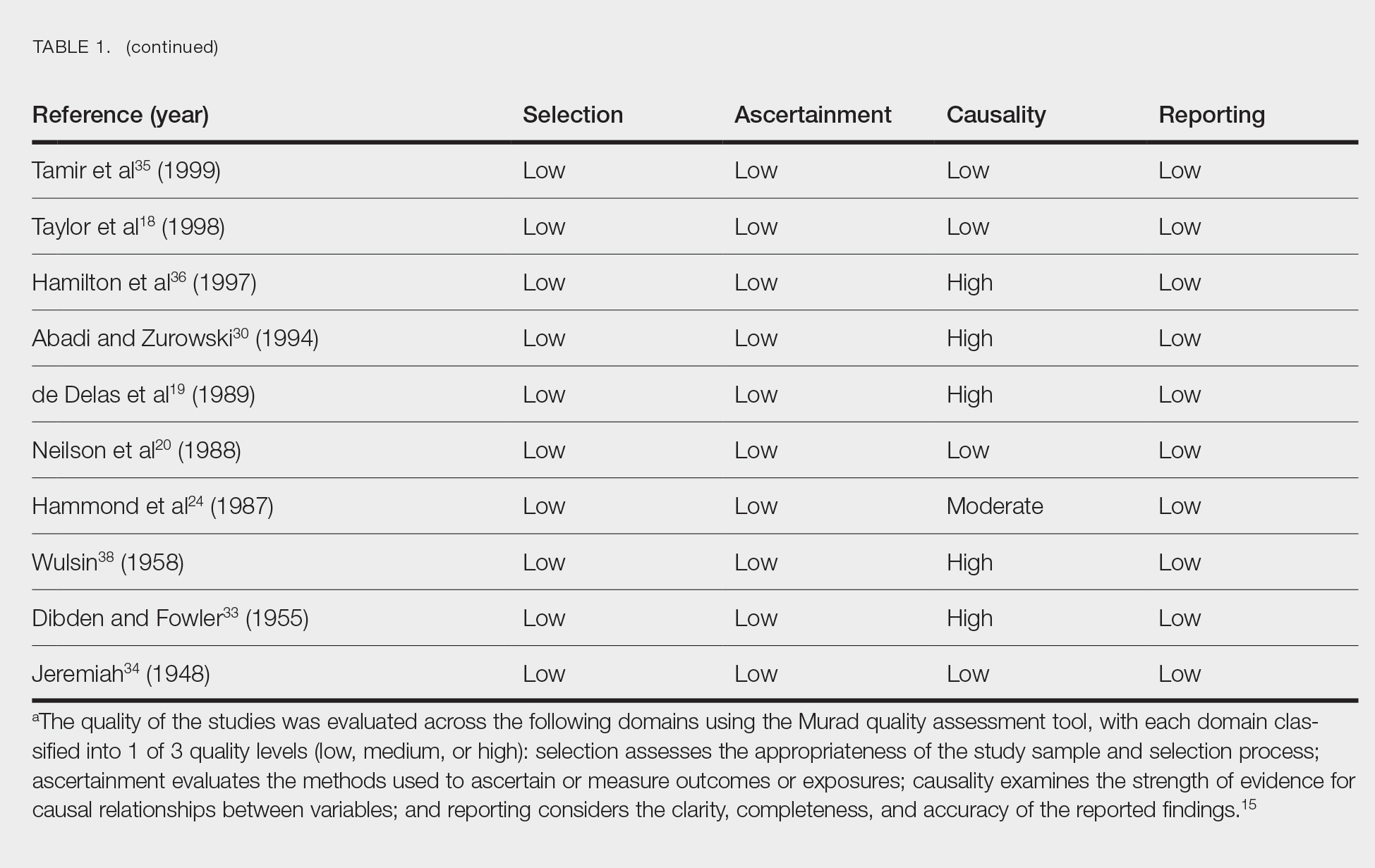

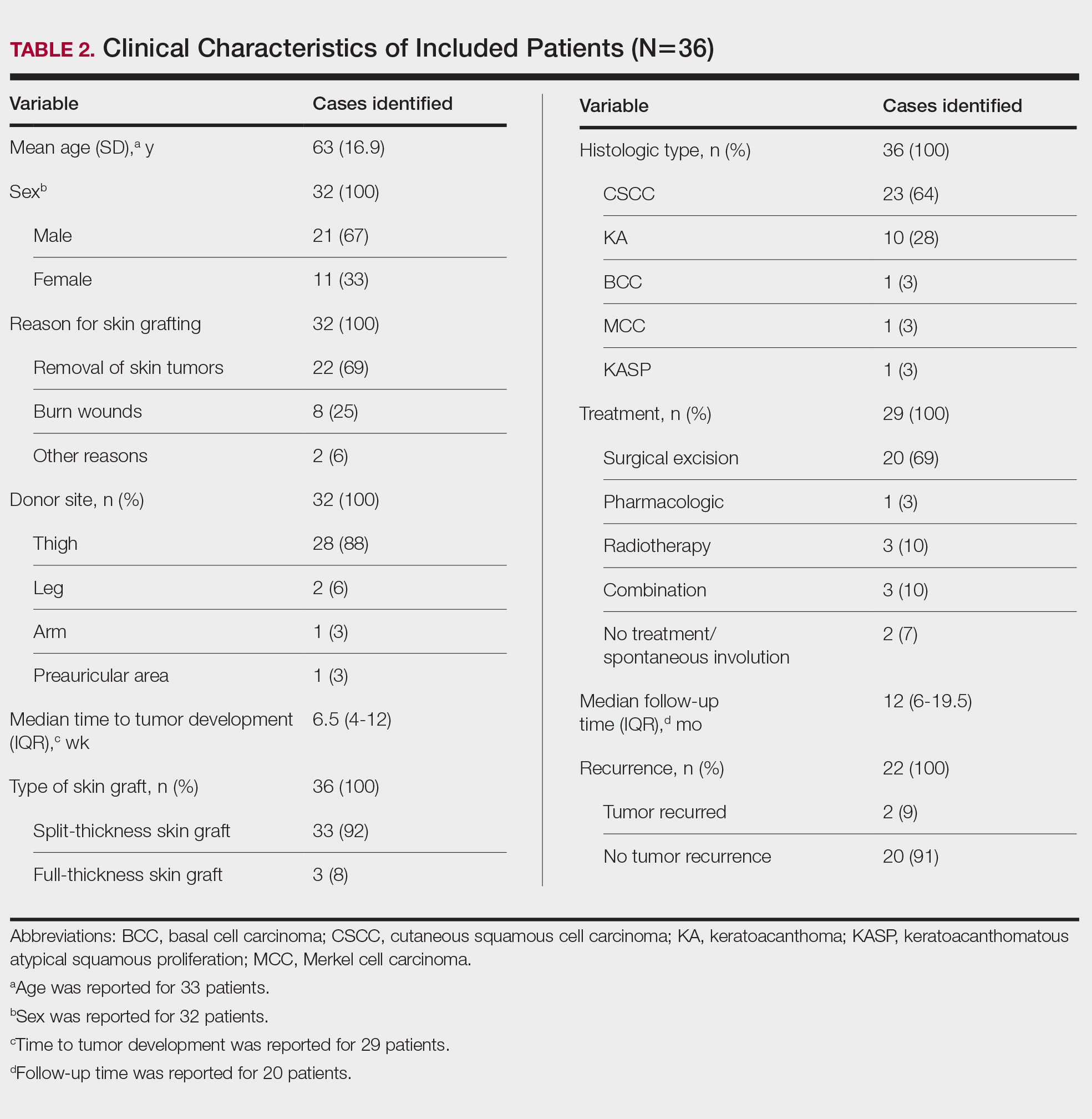

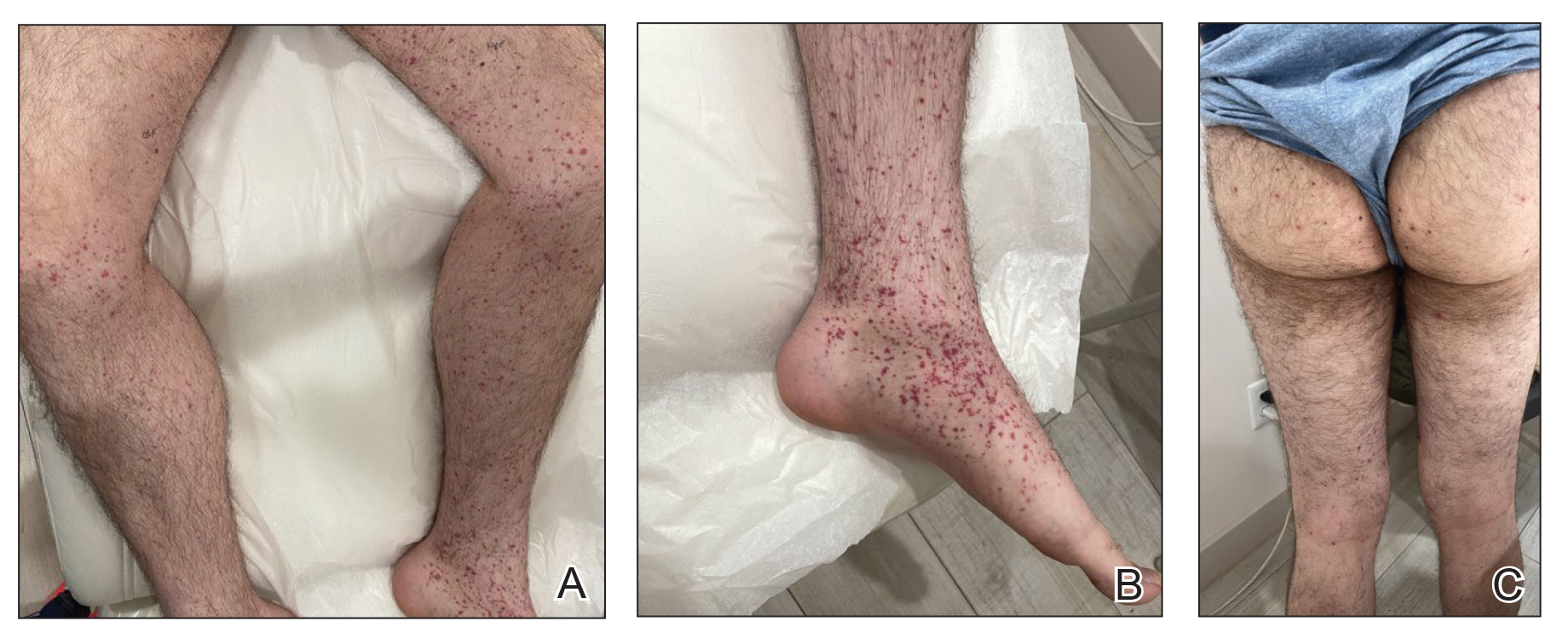

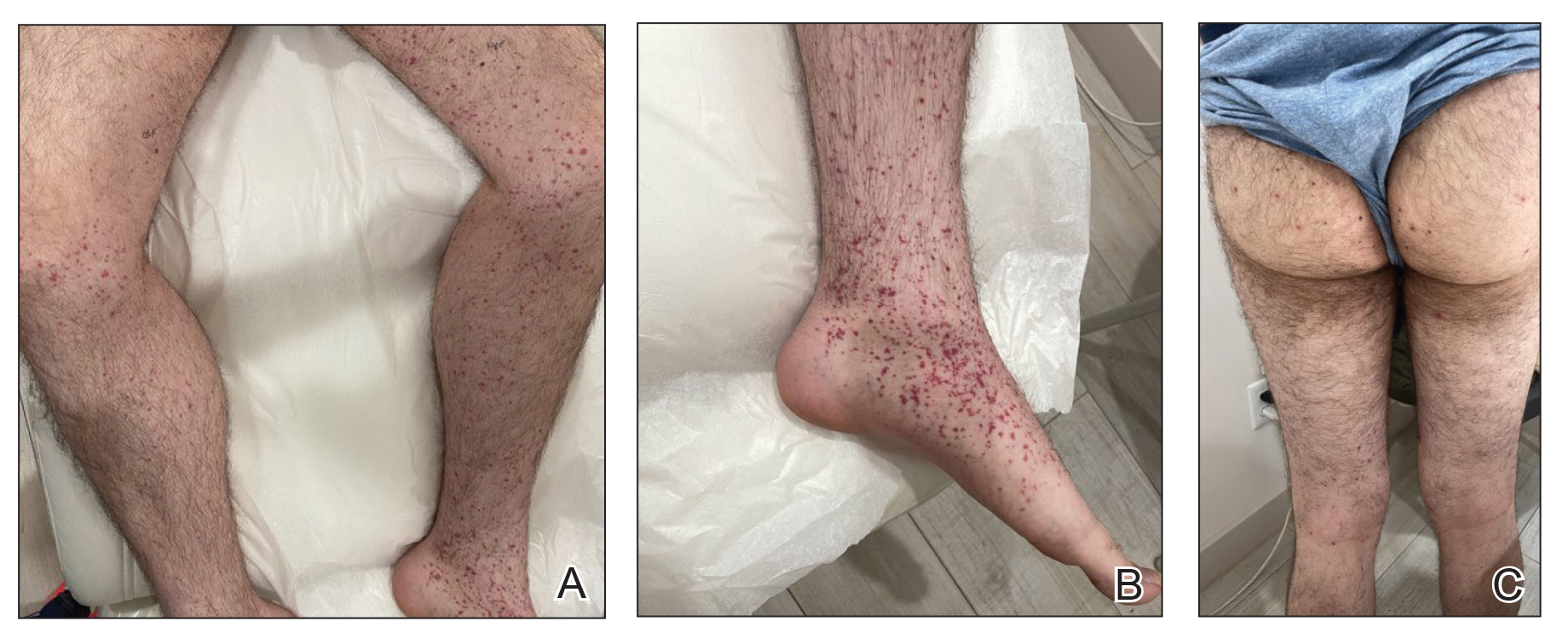

Clinical Characteristics of Included Patients—Our systematic review included 36 patients with a mean age of 63 years and a male to female ratio of 2:1. The 2 most common causes for skin grafting were burn wounds and surgical excision of skin tumors. Most grafts were harvested from the thighs. The development of a solitary lesion on the donor area was reported in two-thirds of the patients, while more than 1 lesion developed in the remaining one-third of patients. The median time to tumor development was 6.5 weeks. In most cases, a split-thickness skin graft was used.

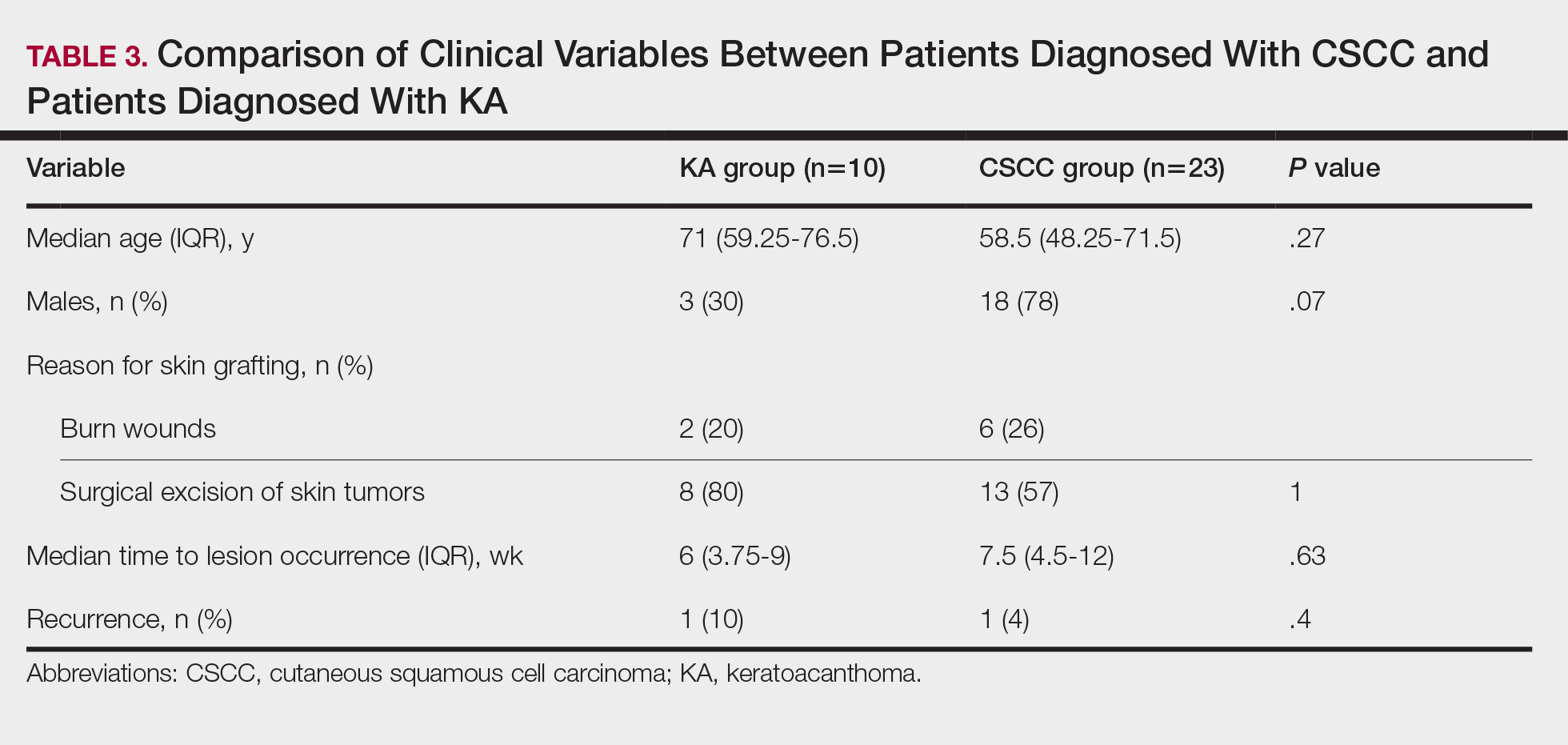

Cutaneous squamous cell carcinomas (CSCCs) were found in 23 patients, with well-differentiated CSCCs in 19 of these cases. Additionally, keratoacanthomas (KAs) were found in 10 patients. The majority of patients underwent surgical excision of the tumor. The median follow-up time was 12 months, during which recurrences were noted in a small percentage of cases. Clinical characteristics of included patients are presented in Table 2.

Comment

Reasons for Tumor Development on Skin Graft Donor Sites—The etiology behind epidermal tumor development on graft donor sites is unclear. According to one theory, iatrogenic contamination of the donor site during the removal of a primary epidermal tumor could be responsible. However, contemporary surgical procedures dictate the use of different sets of instruments for separate surgical sites. Moreover, this theory cannot explain the occurrence of epidermal tumors on donor sites in patients who have undergone skin grafting for the repair of burn wounds.37

Another theory suggests that hematogenous and/or lymphatic spread can occur from the site of the primary epidermal tumor to the donor site, which has increased vascularization.16,37 However, this theory also fails to provide an explanation for the development of epidermal tumors in patients who receive skin grafts for burn wounds.

A third theory states that the microenvironment of the donor site is key to tumor development. The donor site undergoes acute inflammation due to the trauma from harvesting the skin graft. According to this theory, acute inflammation could promote neoplastic growth and thus explain the development of epidermal tumors on the donor site.8,26 However, the relationship between acute inflammation and carcinogenesis remains unclear. What is known to date is that the development of CSCC has been documented primarily in chronically inflamed tissues, whereas the development of KA—a variant of CSCC with distinctive and more benign clinical characteristics—can be expected in the setting of acute trauma-related inflammation.13,40,41