User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Diffuse Pustular Eruption Following Computed Tomography

The Diagnosis: Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

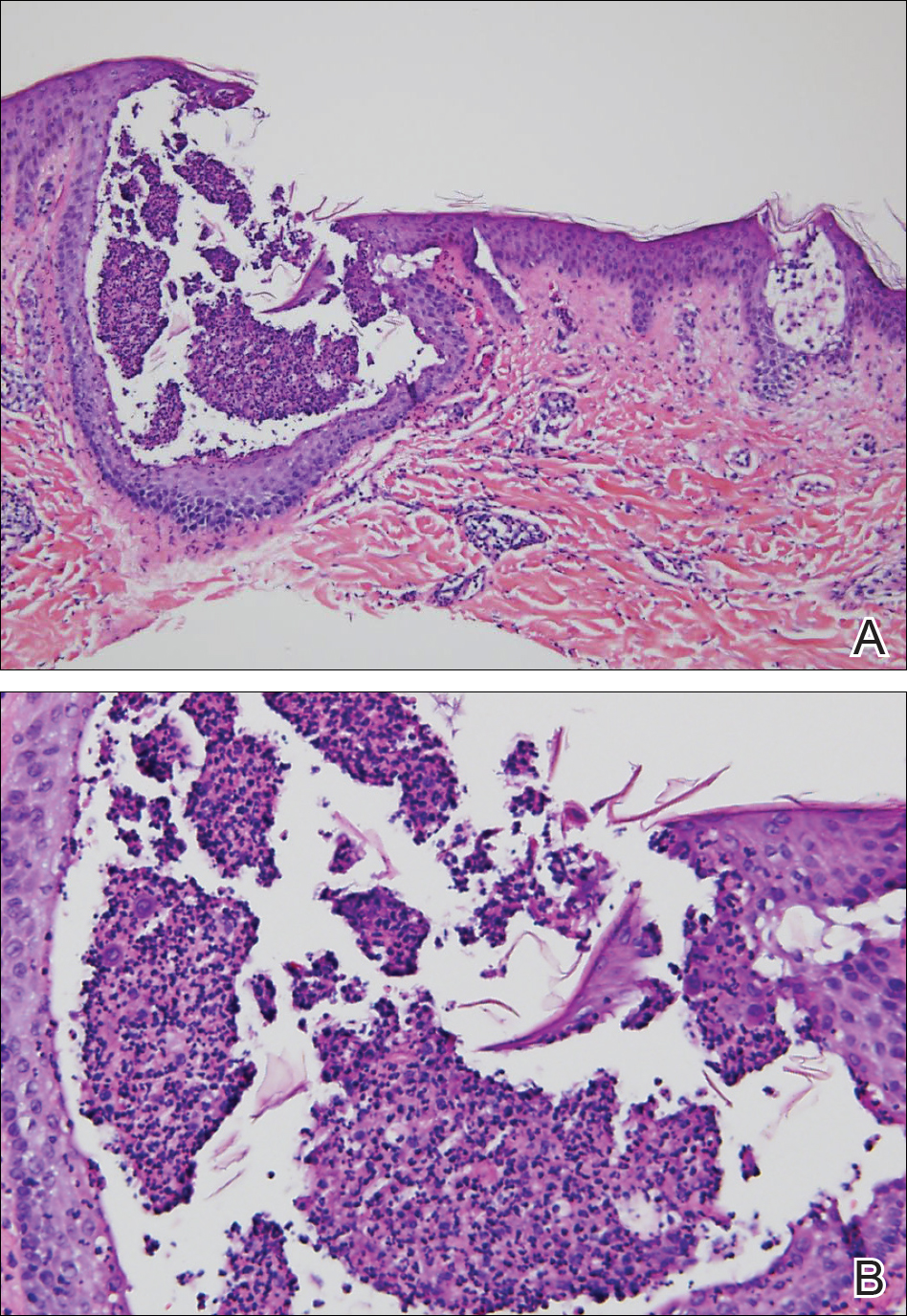

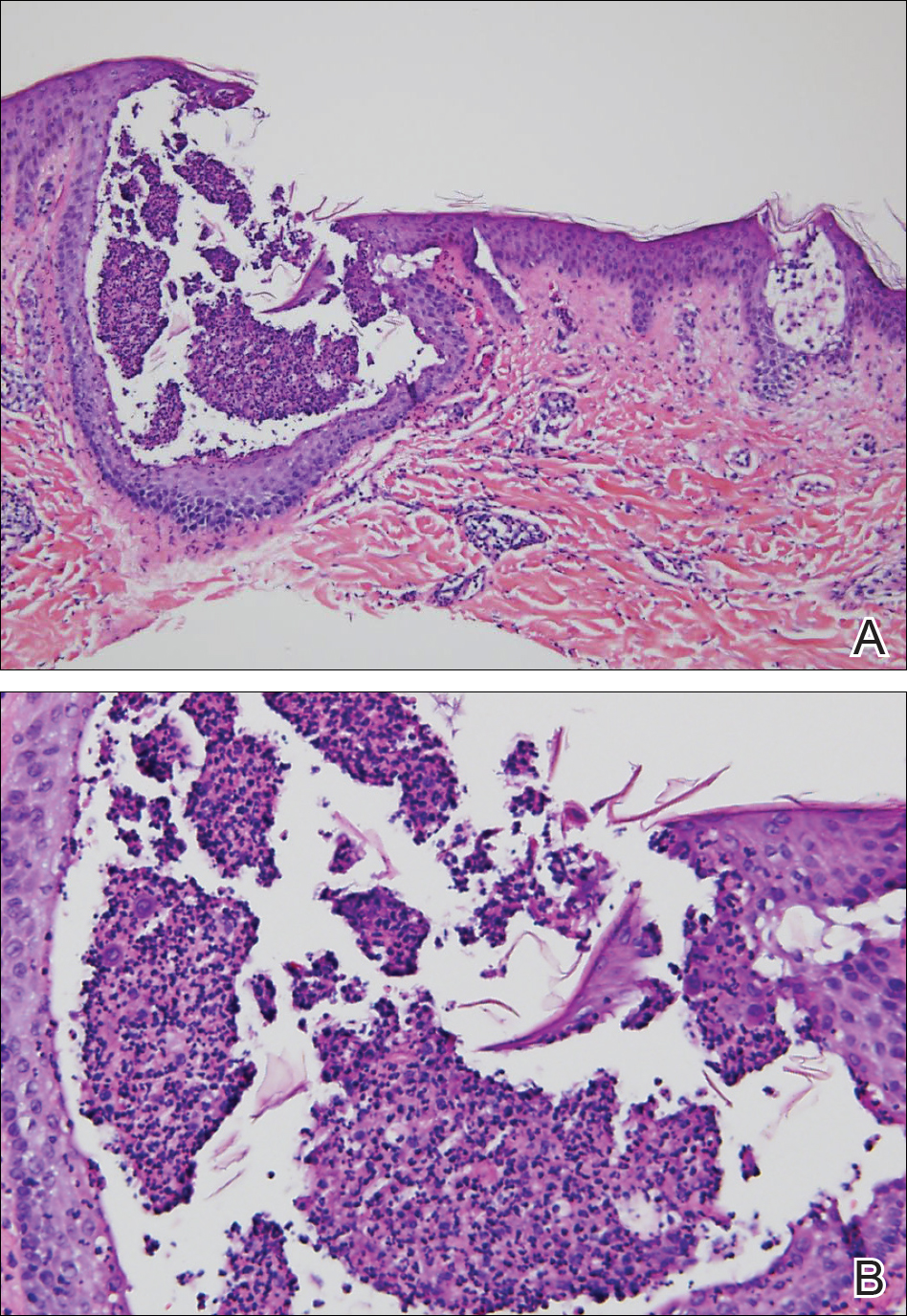

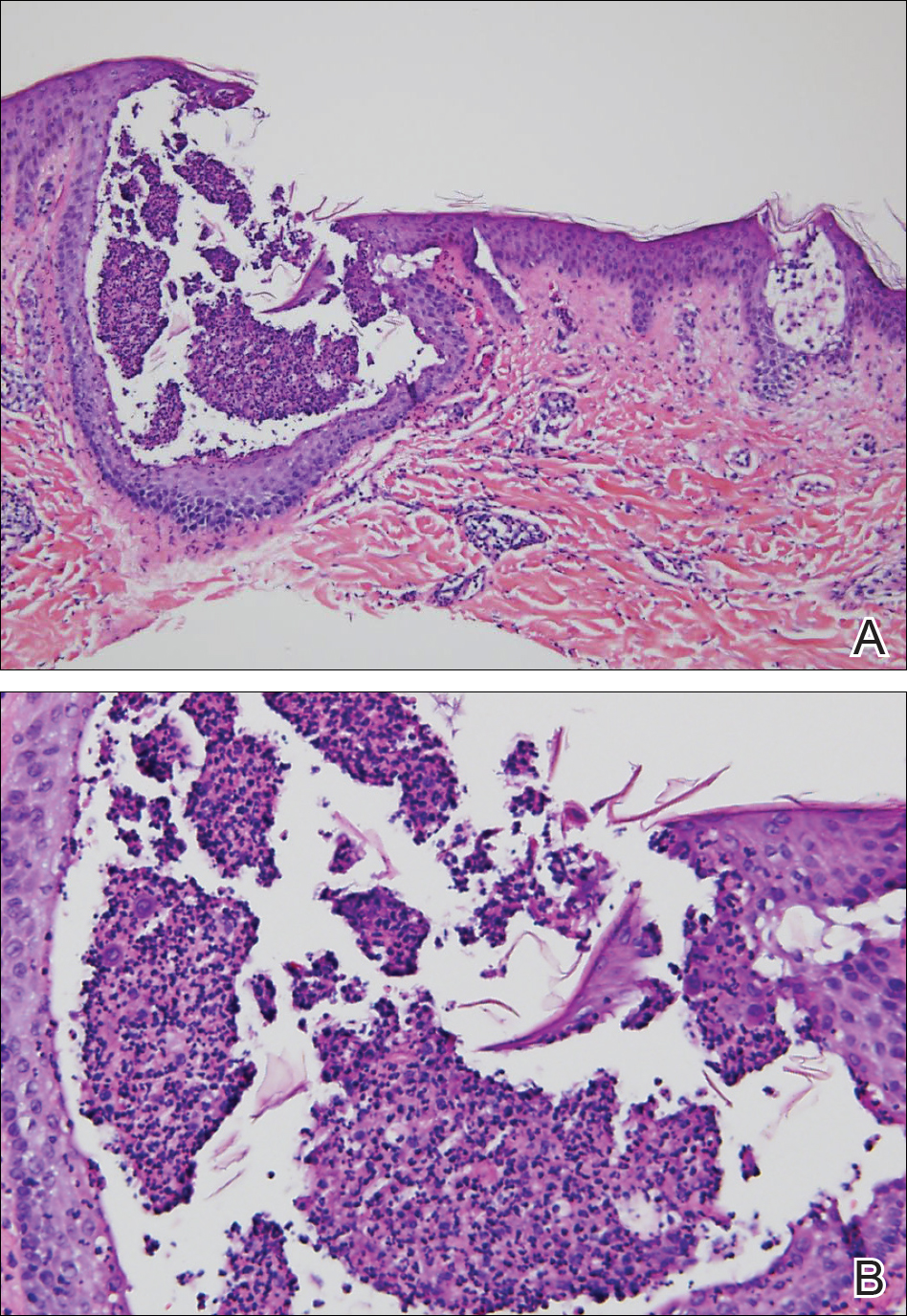

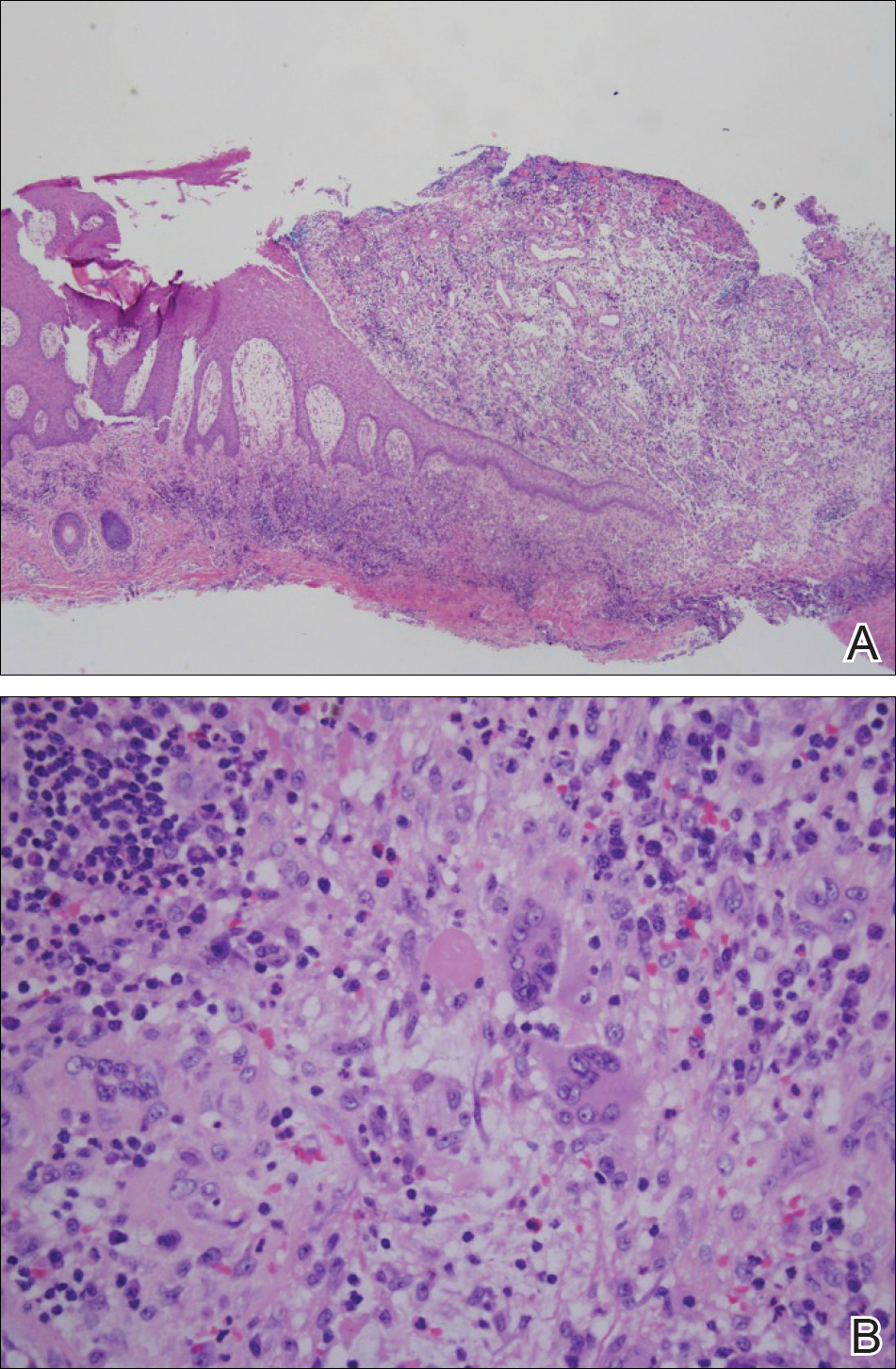

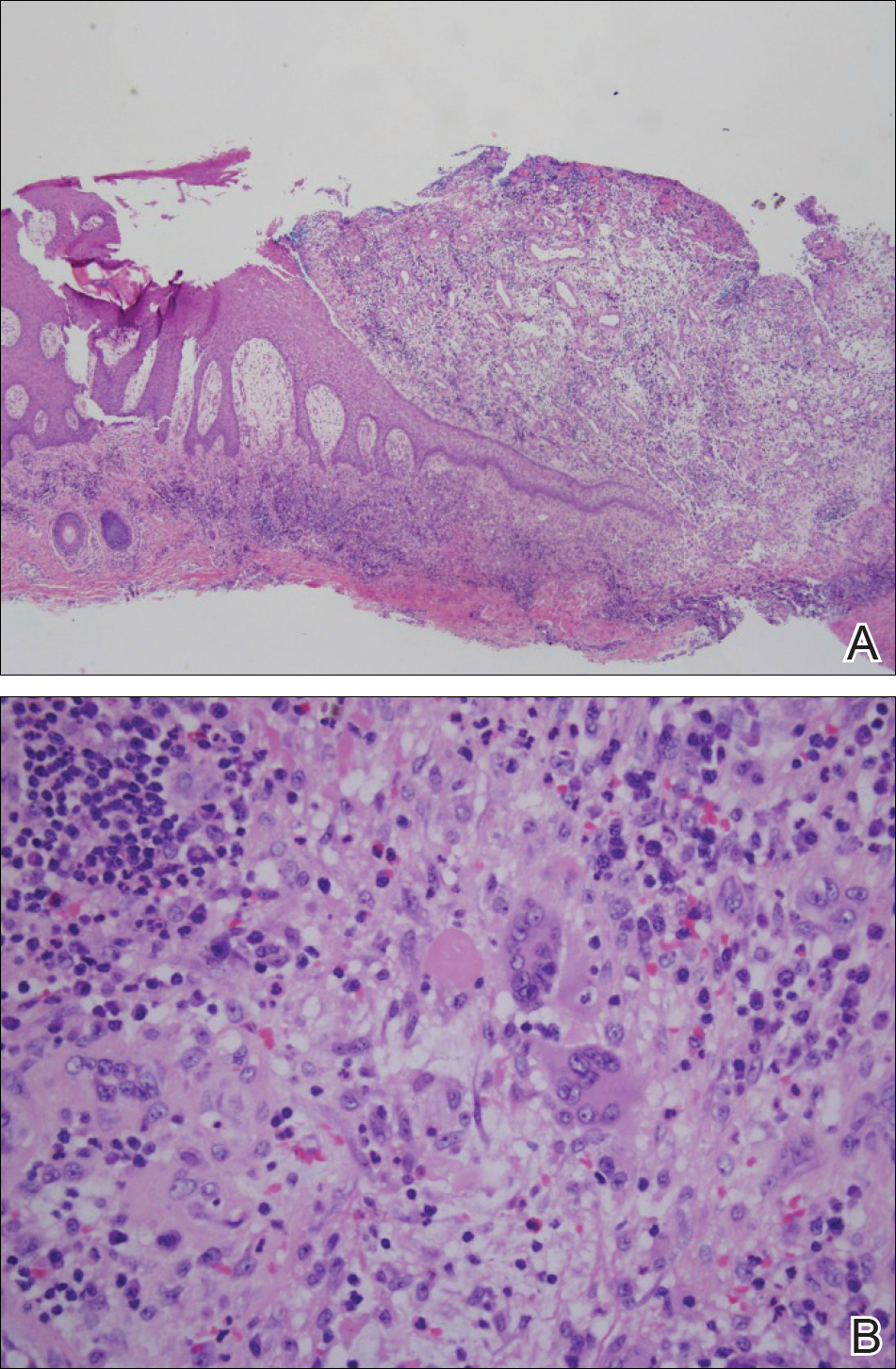

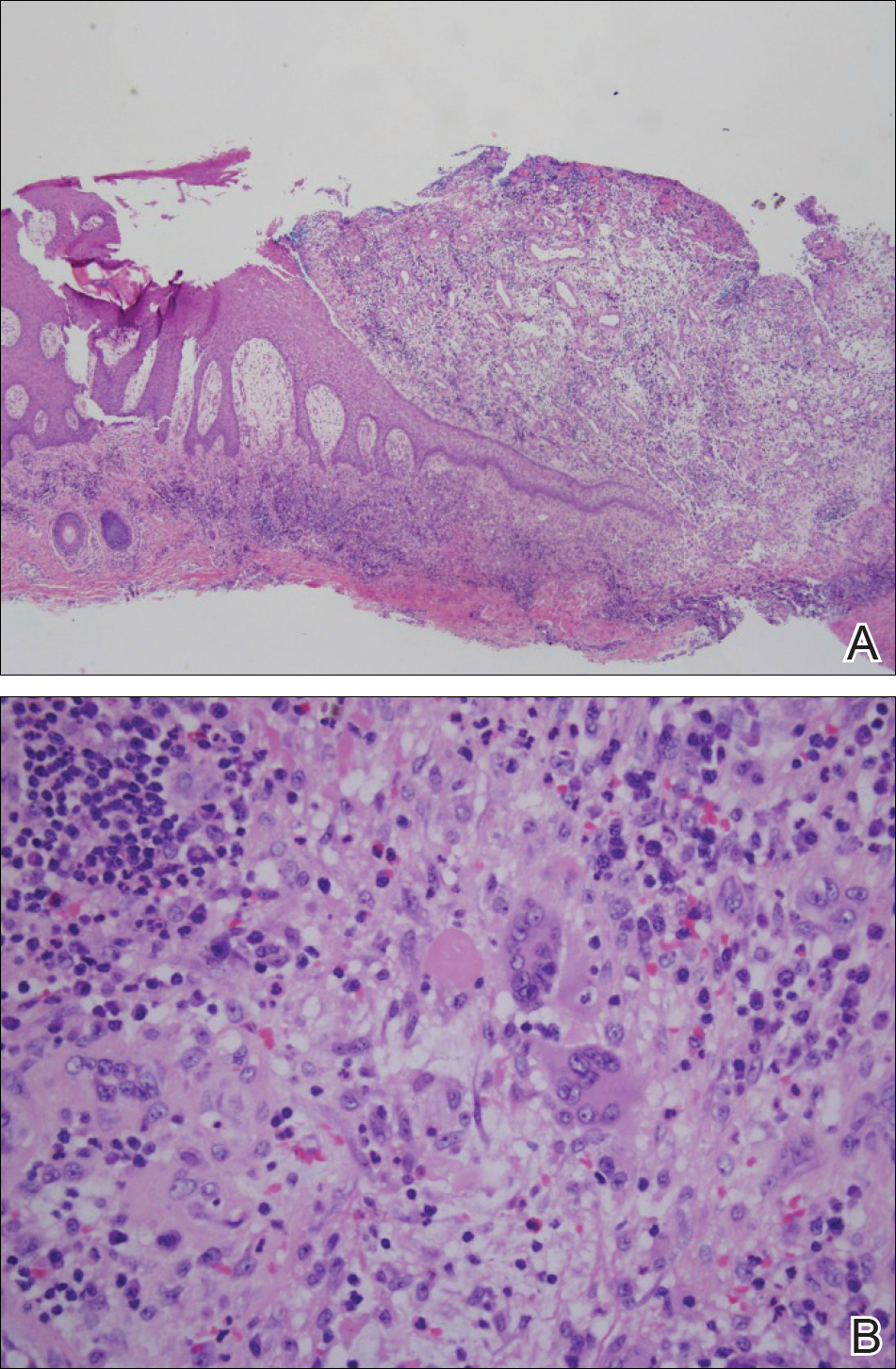

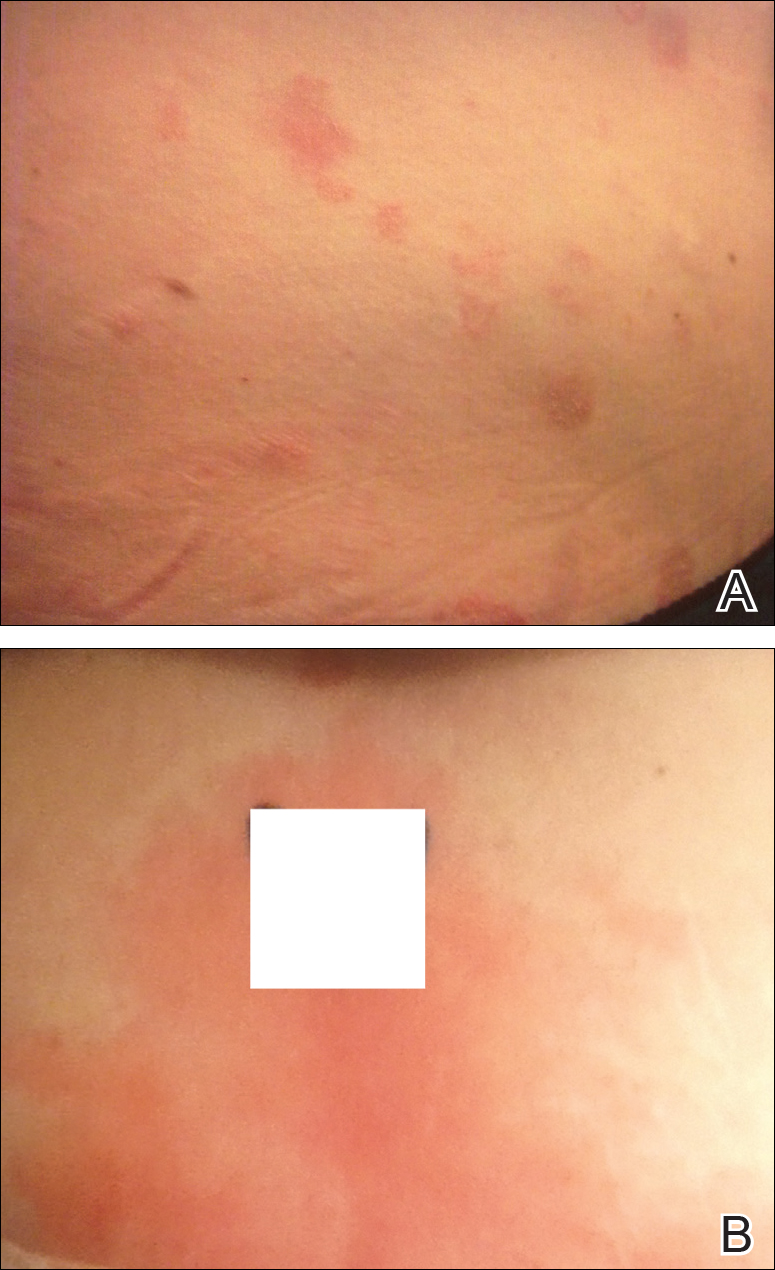

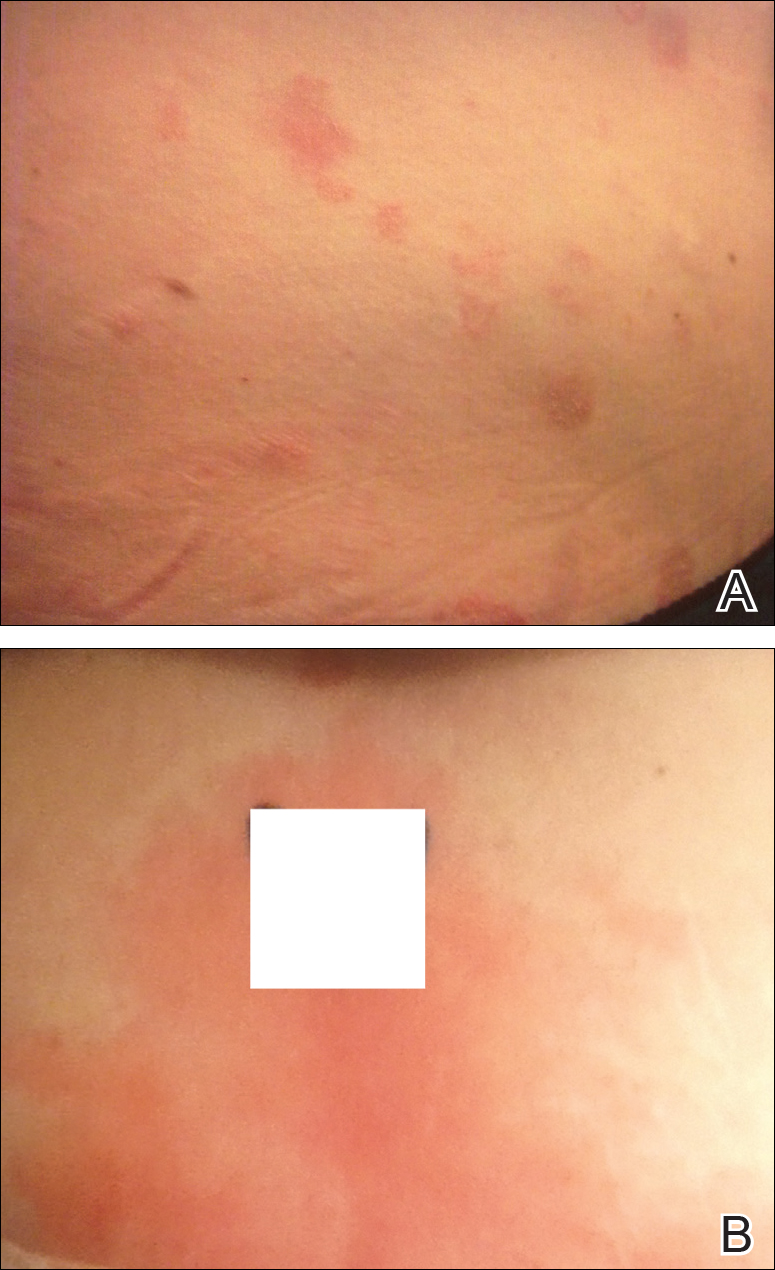

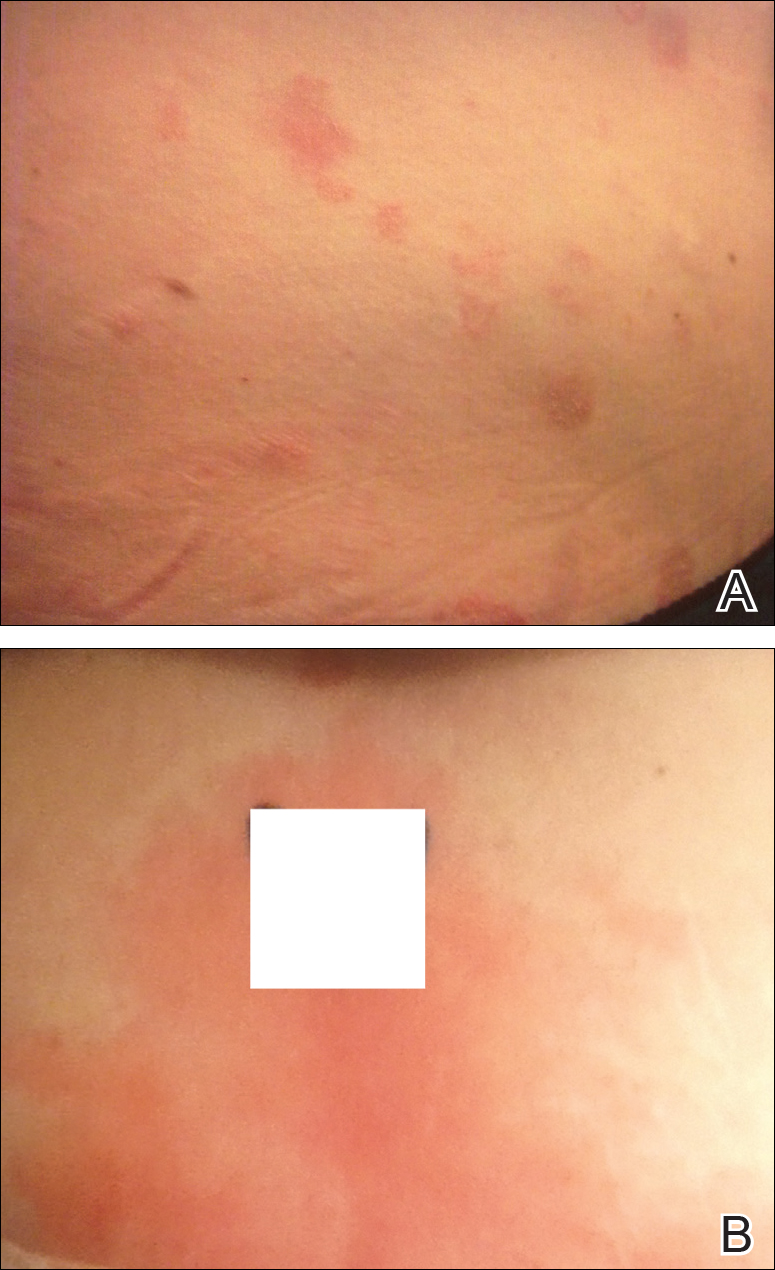

Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal pustules and an overlying basket-weave pattern stratum corneum. There was mild papillary dermal edema with scattered dermal neutrophils and rare eosinophils (Figure). The patient's clinical presentation and histopathology were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). The inciting agent in this case was the contrast medium iopamidol. The patient was treated with a short course of prednisone, triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and acetaminophen. Within 1 week the pustules and erythema had resolved.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon T cell-mediated cutaneous reaction characterized by widespread progressive erythema with numerous nonfollicular pinpoint pustules. The patient usually is well appearing; however, he/she often will have concurrent fever and facial edema. Mucous membranes rarely are involved. Laboratory results typically are notable only for leukocytosis with neutrophilia.

The pustular eruption typically occurs within 1 to 2 days after exposure to an inciting agent1; however, this latent period can range from 1 hour to nearly 4 weeks in some studies.2 Systemic medications are the cause in approximately 90% of cases, with antibiotics being the most common category. Frequently implicated medications include β-lactams, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, proton pump inhibitors, hydroxychloroquine, terbinafine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diltiazem, ketoconazole, and fluconazole. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis also has been rarely reported following contact with mercury, viral and bacterial infections, and spider bites.3

Iodinated contrast agents have long been known to cause immediate and delayed adverse cutaneous reactions. However, one consensus study indicated that these reactions occur in only 0.05% to 0.10% of patients.4 Although rare, iodinated contrast media (eg, iopamidol, iohexol, ioversol, iodixanol, iomeprol, iobitridol, iopromide) have been reported as a cause of AGEP. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, contrast, iodine, and iodinated revealed 10 adult cases reported in 6 articles in the English-language literature.1,5-9 The most recent articles focus on methods to identify the causative agent. If the etiology of the reaction is unclear, patch or intradermal testing can help to confirm the causative agent. These tests also can help determine similar agents to which the patient may cross-react.4,5

It can be difficult to differentiate AGEP from other cutaneous drug reactions and other nonfollicular pustular conditions. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome typically presents with facial edema and a morbilliform rash. Although it can present with pustules, the latent period is longer (2-6 weeks), and there frequently are signs of multiorgan involvement including hepatic dysfunction, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and lymphadenopathy. Patients with generalized pustular psoriasis often have a history of plaque psoriasis; the pustules are more concentrated in flexural sites; the eruption is gradual in onset; and histologically there tends to be features of psoriasis including parakeratosis, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels.10 Subcorneal pustular dermatosis also is more concentrated in flexural sites and frequently has an annular or serpiginous configuration. The onset also is gradual, and it follows a more chronic course than AGEP. Exfoliative erythroderma presents with widespread erythema and superficial desquamating scale. It often occurs in association with systemic symptoms and can be the result of a drug reaction or underlying inflammatory dermatosis such as psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, or pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks and is associated with a superficial desquamation as it clears. Appropriate treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent; monitoring for systemic involvement; and treating the patient's symptoms with antihistamines, analgesics, topical steroids, and emollients. In more severe or persistent cases, treatment with systemic steroids and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors has been attempted, though their efficacy remains unclear. We report a case of iopamidol-induced AGEP that highlights the importance of eliciting a history of contrast exposure from a patient with suspected AGEP.

- Hammerbeck AA, Daniels NH, Callen JP. Ioversol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:683-687.

- Thienvibul C, Vachiramon V, Chanprapaph K. Five-year retrospective review of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:1-8.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;73:843-848.

- Rosado Ingelmo A, Doña Diaz I, Cabañas Moreno R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2016;26:144-155.

- Grandvuillemin A, Ripert C, Sgro C, et al. Iodinated contrast media-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by delayed skin tests. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:805-806.

- Bavbek S, Sözener ZÇ, Aydin Ö, et al. First case report of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to intravenous iopromide. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:66-67.

- Kim SJ, Lee T, Lee YS, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by radiocontrast media. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:492-493.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:198-201.

- Atasoy M, Erdem T, Sari RA. A case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) possibly induced by iohexol. J Dermatol. 2003;30:723-726.

- Halevy S, Kardaun S, Davidovici B, et al; EuroSCAR and RegiSCAR Study Group. The spectrum of histopathological features in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a study of 102 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2010:163:1245-1252.

The Diagnosis: Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal pustules and an overlying basket-weave pattern stratum corneum. There was mild papillary dermal edema with scattered dermal neutrophils and rare eosinophils (Figure). The patient's clinical presentation and histopathology were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). The inciting agent in this case was the contrast medium iopamidol. The patient was treated with a short course of prednisone, triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and acetaminophen. Within 1 week the pustules and erythema had resolved.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon T cell-mediated cutaneous reaction characterized by widespread progressive erythema with numerous nonfollicular pinpoint pustules. The patient usually is well appearing; however, he/she often will have concurrent fever and facial edema. Mucous membranes rarely are involved. Laboratory results typically are notable only for leukocytosis with neutrophilia.

The pustular eruption typically occurs within 1 to 2 days after exposure to an inciting agent1; however, this latent period can range from 1 hour to nearly 4 weeks in some studies.2 Systemic medications are the cause in approximately 90% of cases, with antibiotics being the most common category. Frequently implicated medications include β-lactams, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, proton pump inhibitors, hydroxychloroquine, terbinafine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diltiazem, ketoconazole, and fluconazole. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis also has been rarely reported following contact with mercury, viral and bacterial infections, and spider bites.3

Iodinated contrast agents have long been known to cause immediate and delayed adverse cutaneous reactions. However, one consensus study indicated that these reactions occur in only 0.05% to 0.10% of patients.4 Although rare, iodinated contrast media (eg, iopamidol, iohexol, ioversol, iodixanol, iomeprol, iobitridol, iopromide) have been reported as a cause of AGEP. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, contrast, iodine, and iodinated revealed 10 adult cases reported in 6 articles in the English-language literature.1,5-9 The most recent articles focus on methods to identify the causative agent. If the etiology of the reaction is unclear, patch or intradermal testing can help to confirm the causative agent. These tests also can help determine similar agents to which the patient may cross-react.4,5

It can be difficult to differentiate AGEP from other cutaneous drug reactions and other nonfollicular pustular conditions. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome typically presents with facial edema and a morbilliform rash. Although it can present with pustules, the latent period is longer (2-6 weeks), and there frequently are signs of multiorgan involvement including hepatic dysfunction, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and lymphadenopathy. Patients with generalized pustular psoriasis often have a history of plaque psoriasis; the pustules are more concentrated in flexural sites; the eruption is gradual in onset; and histologically there tends to be features of psoriasis including parakeratosis, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels.10 Subcorneal pustular dermatosis also is more concentrated in flexural sites and frequently has an annular or serpiginous configuration. The onset also is gradual, and it follows a more chronic course than AGEP. Exfoliative erythroderma presents with widespread erythema and superficial desquamating scale. It often occurs in association with systemic symptoms and can be the result of a drug reaction or underlying inflammatory dermatosis such as psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, or pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks and is associated with a superficial desquamation as it clears. Appropriate treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent; monitoring for systemic involvement; and treating the patient's symptoms with antihistamines, analgesics, topical steroids, and emollients. In more severe or persistent cases, treatment with systemic steroids and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors has been attempted, though their efficacy remains unclear. We report a case of iopamidol-induced AGEP that highlights the importance of eliciting a history of contrast exposure from a patient with suspected AGEP.

The Diagnosis: Acute Generalized Exanthematous Pustulosis

Histopathology demonstrated spongiosis with subcorneal pustules and an overlying basket-weave pattern stratum corneum. There was mild papillary dermal edema with scattered dermal neutrophils and rare eosinophils (Figure). The patient's clinical presentation and histopathology were consistent with acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP). The inciting agent in this case was the contrast medium iopamidol. The patient was treated with a short course of prednisone, triamcinolone cream, diphenhydramine, and acetaminophen. Within 1 week the pustules and erythema had resolved.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis is an uncommon T cell-mediated cutaneous reaction characterized by widespread progressive erythema with numerous nonfollicular pinpoint pustules. The patient usually is well appearing; however, he/she often will have concurrent fever and facial edema. Mucous membranes rarely are involved. Laboratory results typically are notable only for leukocytosis with neutrophilia.

The pustular eruption typically occurs within 1 to 2 days after exposure to an inciting agent1; however, this latent period can range from 1 hour to nearly 4 weeks in some studies.2 Systemic medications are the cause in approximately 90% of cases, with antibiotics being the most common category. Frequently implicated medications include β-lactams, macrolides, quinolones, sulfonamides, proton pump inhibitors, hydroxychloroquine, terbinafine, nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, diltiazem, ketoconazole, and fluconazole. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis also has been rarely reported following contact with mercury, viral and bacterial infections, and spider bites.3

Iodinated contrast agents have long been known to cause immediate and delayed adverse cutaneous reactions. However, one consensus study indicated that these reactions occur in only 0.05% to 0.10% of patients.4 Although rare, iodinated contrast media (eg, iopamidol, iohexol, ioversol, iodixanol, iomeprol, iobitridol, iopromide) have been reported as a cause of AGEP. A PubMed search of articles indexed for MEDLINE using the terms acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis, contrast, iodine, and iodinated revealed 10 adult cases reported in 6 articles in the English-language literature.1,5-9 The most recent articles focus on methods to identify the causative agent. If the etiology of the reaction is unclear, patch or intradermal testing can help to confirm the causative agent. These tests also can help determine similar agents to which the patient may cross-react.4,5

It can be difficult to differentiate AGEP from other cutaneous drug reactions and other nonfollicular pustular conditions. Drug-induced hypersensitivity syndrome typically presents with facial edema and a morbilliform rash. Although it can present with pustules, the latent period is longer (2-6 weeks), and there frequently are signs of multiorgan involvement including hepatic dysfunction, eosinophilia, atypical lymphocytosis, and lymphadenopathy. Patients with generalized pustular psoriasis often have a history of plaque psoriasis; the pustules are more concentrated in flexural sites; the eruption is gradual in onset; and histologically there tends to be features of psoriasis including parakeratosis, Munro microabscesses, and dilated blood vessels.10 Subcorneal pustular dermatosis also is more concentrated in flexural sites and frequently has an annular or serpiginous configuration. The onset also is gradual, and it follows a more chronic course than AGEP. Exfoliative erythroderma presents with widespread erythema and superficial desquamating scale. It often occurs in association with systemic symptoms and can be the result of a drug reaction or underlying inflammatory dermatosis such as psoriasis, mycosis fungoides, or pityriasis rubra pilaris.

Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis usually resolves spontaneously within 2 weeks and is associated with a superficial desquamation as it clears. Appropriate treatment includes discontinuing the offending agent; monitoring for systemic involvement; and treating the patient's symptoms with antihistamines, analgesics, topical steroids, and emollients. In more severe or persistent cases, treatment with systemic steroids and tumor necrosis factor α inhibitors has been attempted, though their efficacy remains unclear. We report a case of iopamidol-induced AGEP that highlights the importance of eliciting a history of contrast exposure from a patient with suspected AGEP.

- Hammerbeck AA, Daniels NH, Callen JP. Ioversol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:683-687.

- Thienvibul C, Vachiramon V, Chanprapaph K. Five-year retrospective review of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:1-8.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;73:843-848.

- Rosado Ingelmo A, Doña Diaz I, Cabañas Moreno R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2016;26:144-155.

- Grandvuillemin A, Ripert C, Sgro C, et al. Iodinated contrast media-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by delayed skin tests. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:805-806.

- Bavbek S, Sözener ZÇ, Aydin Ö, et al. First case report of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to intravenous iopromide. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:66-67.

- Kim SJ, Lee T, Lee YS, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by radiocontrast media. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:492-493.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:198-201.

- Atasoy M, Erdem T, Sari RA. A case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) possibly induced by iohexol. J Dermatol. 2003;30:723-726.

- Halevy S, Kardaun S, Davidovici B, et al; EuroSCAR and RegiSCAR Study Group. The spectrum of histopathological features in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a study of 102 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2010:163:1245-1252.

- Hammerbeck AA, Daniels NH, Callen JP. Ioversol-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Arch Dermatol. 2009;145:683-687.

- Thienvibul C, Vachiramon V, Chanprapaph K. Five-year retrospective review of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis. Dermatol Res Pract. 2015;2015:1-8.

- Szatkowski J, Schwartz RA. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP): a review and update. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2016;73:843-848.

- Rosado Ingelmo A, Doña Diaz I, Cabañas Moreno R, et al. Clinical practice guidelines for diagnosis and management of hypersensitivity reactions to contrast media. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2016;26:144-155.

- Grandvuillemin A, Ripert C, Sgro C, et al. Iodinated contrast media-induced acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis confirmed by delayed skin tests. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2014;2:805-806.

- Bavbek S, Sözener ZÇ, Aydin Ö, et al. First case report of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis due to intravenous iopromide. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol. 2014;24:66-67.

- Kim SJ, Lee T, Lee YS, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis caused by radiocontrast media. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2010;105:492-493.

- Peterson A, Katzberg RW, Fung MA, et al. Acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis as a delayed dermatotoxic reaction to IV-administered nonionic contrast media. Am J Roentgenol. 2006;187:198-201.

- Atasoy M, Erdem T, Sari RA. A case of acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis (AGEP) possibly induced by iohexol. J Dermatol. 2003;30:723-726.

- Halevy S, Kardaun S, Davidovici B, et al; EuroSCAR and RegiSCAR Study Group. The spectrum of histopathological features in acute generalized exanthematous pustulosis: a study of 102 cases. Br J Dermatol. 2010:163:1245-1252.

A 31-year-old man presented with a rapidly progressive, burning rash of 1 day's duration, along with malaise, nausea, and dizziness. At the time of presentation, he was hemodynamically stable and afebrile. Laboratory analysis revealed mild leukocytosis with neutrophilia. A complete metabolic panel was within normal limits. He had no chronic medical conditions and was taking no medications or supplements. One day prior to onset of the rash, he underwent contrast-enhanced (iopamidol) computed tomography of the abdomen. Physical examination revealed large edematous plaques on the face, neck, and trunk (top) that were studded with numerous pinpoint pustules (bottom). He also had subtle facial edema. There was relative sparing of the flexural sites and no involvement of the palms, soles, or mucous membranes. A shave biopsy was obtained from a pustular area on the neck.

Google Search Results for Diet and Psoriasis: Advice Patients Get on the Internet

Innovations in Dermatology: Sarecycline Approved for Acne

Inpatient Dermatology: Developing Standards of Care for Hospitalized Patients With Skin Disease

Treatment Options for Pilonidal Sinus

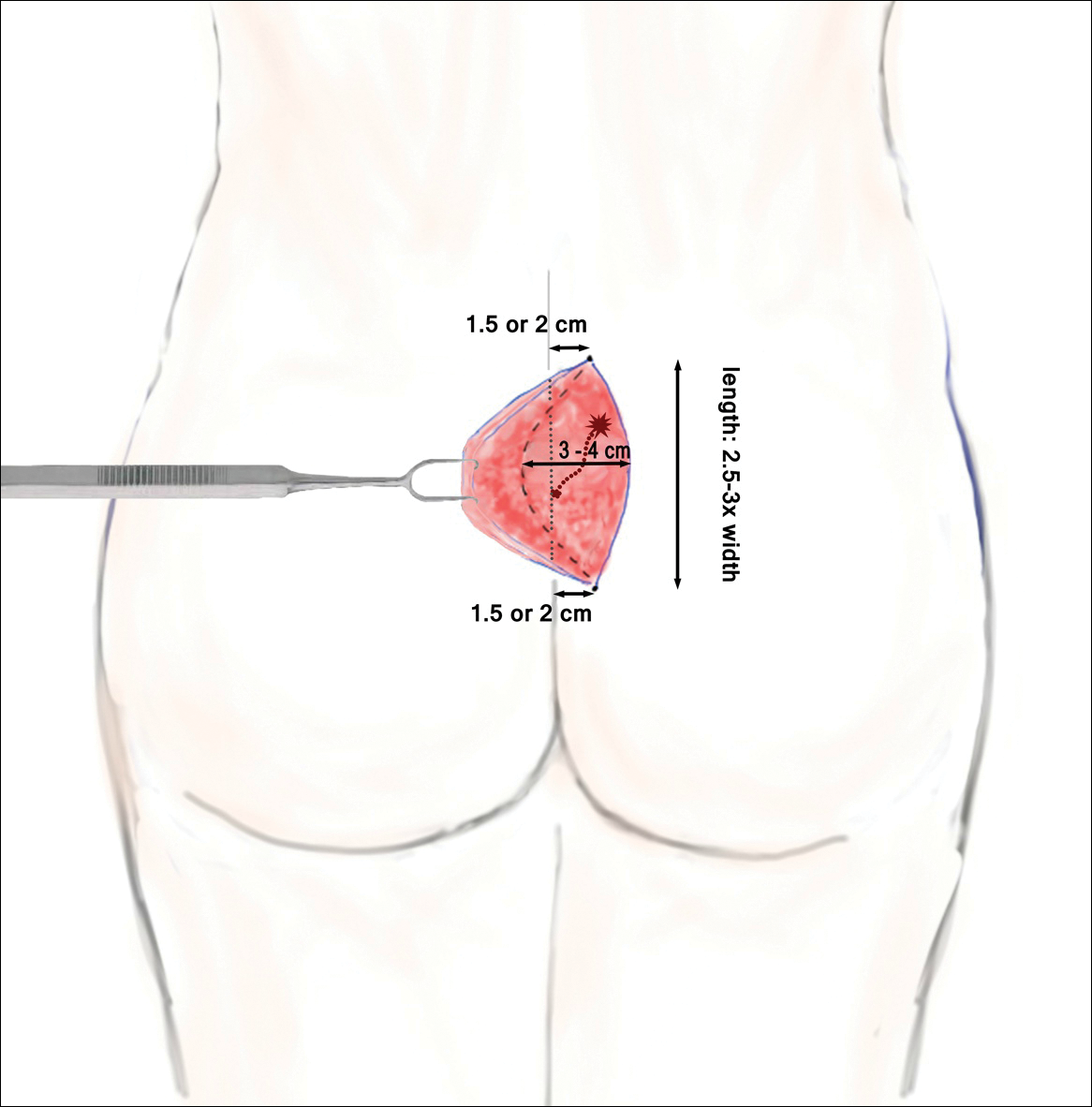

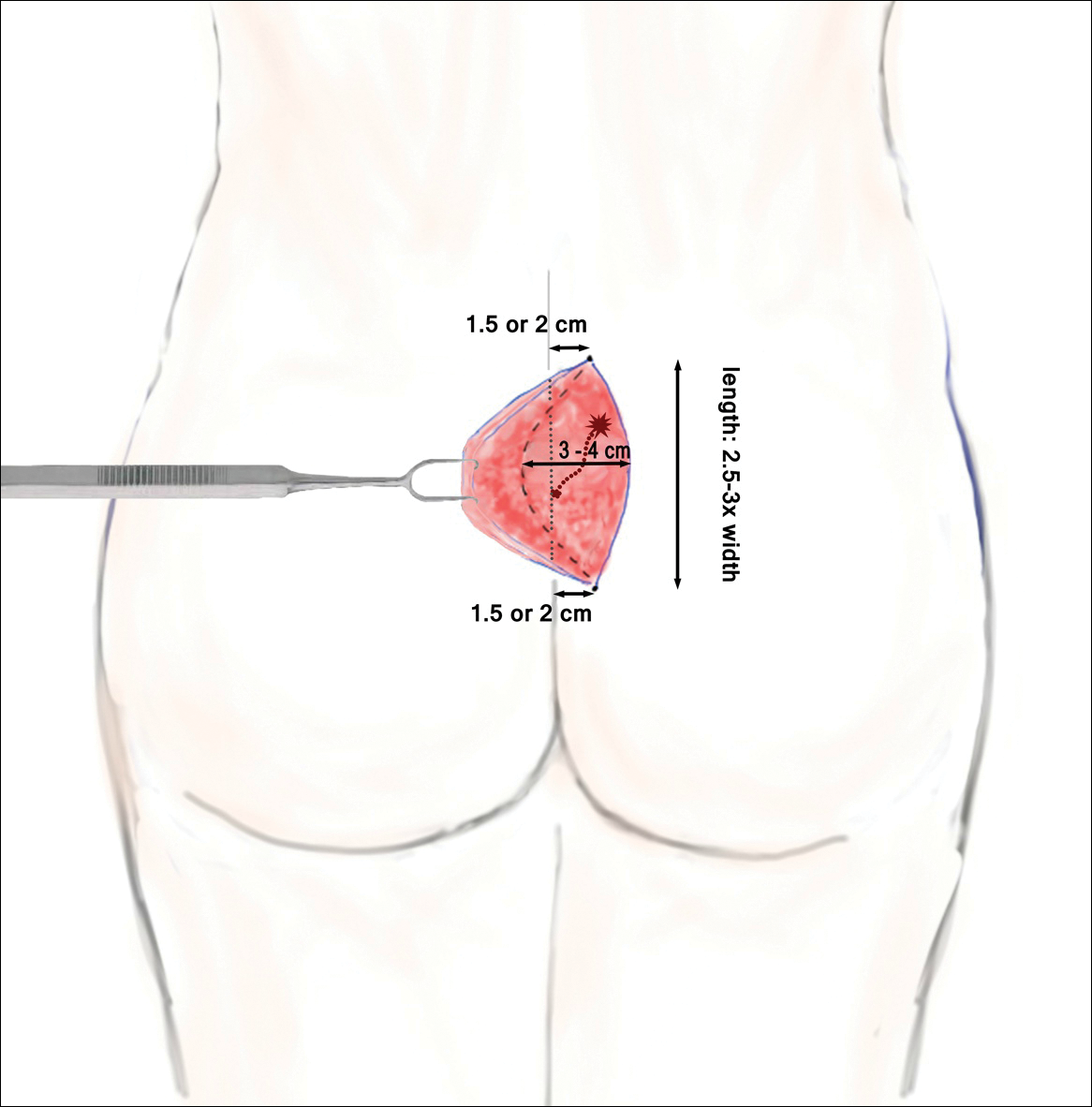

Pilonidal disease was first described by Mayo1 in 1833 who hypothesized that the underlying etiology is incomplete separation of the mesoderm and ectoderm layers during embryogenesis. In 1880, Hodges2 coined the term pilonidal sinus; he postulated that sinus formation was incited by hair.2 Today, Hodges theory is known as the acquired theory: hair induces a foreign body response in surrounding tissue, leading to sinus formation. Although pilonidal cysts can occur anywhere on the body, they most commonly extend cephalad in the sacrococcygeal and upper gluteal cleft (Figure 1).3,4 An acute pilonidal cyst typically presents with pain, tenderness, and swelling, similar to the presentation of a superficial abscess in other locations; however, a clue to the diagnosis is the presence of cutaneous pits along the midline of the gluteal cleft.5 Chronic pilonidal disease varies based on the extent of inflammation and scarring; the underlying cavity communicates with the overlying skin through sinuses and often drains with pressure.6

Pilonidal sinuses are rare before puberty or after 40 years of age7 and occur primarily in hirsute men. The ratio of men to women affected is between 3:1 and 4:1.8 Although pilonidal sinuses account for only 15% of anal suppurations, complications arising from pilonidal sinuses are a considerable cause of morbidity, resulting in loss of productivity in otherwise healthy individuals.9 Complications include chronic nonhealing wounds,10 as recurrent pilonidal sinuses tend to become colonized with gram-positive and facultative anaerobic bacteria, whereas primary pilonidal cysts more commonly become infected with anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria.11 Long-standing disease increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma arising within sinus tracts.10,12

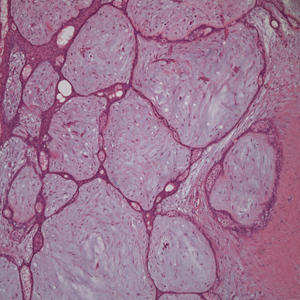

Histopathologically, pilonidal cysts are not true cysts because they lack an epithelial lining. Examination of the cavity commonly reveals hair, debris, and granulation tissue with surrounding foreign-body giant cells (Figure 2).5

The preferred treatment of pilonidal cysts continues to be debated. In this article, we review evidence supporting current modalities including conservative and surgical techniques as well as novel laser therapy for the treatment of pilonidal disease.

Conservative Management Techniques

Phenol Injections

Liquid or crystallized phenol injections have been used for treatment of mild to moderate pilonidal cysts.13 Excess debris is removed by curettage, and phenol is administered through the existing orifices or pits without pressure. The phenol remains in the cavity for 1 to 3 minutes before aspiration. Remaining cyst contents are removed through tissue manipulation, and the sinus is washed with saline. Mean healing time is 20 days (range, +/−14 days).13

Classically, phenol injections have a failure rate of 30% to 40%, especially with multiple sinuses and suppurative disease6; however, the success rate improves with limited disease (ie, no more than 1–3 sinus pits).3 With multiple treatment sessions, a recurrence rate as low as 2% over 25 months has been reported.14 Phenol injection also has been proposed as an adjuvant therapy to pit excision to minimize the need for extensive surgery.15

Simple Incision and Drainage

Simple incision and drainage has a crucial role in the treatment of acute pilonidal disease to decrease pain and relieve tension. Off-midline incisions have been recommended for because the resulting closures fared better against sheer forces applied by the gluteal muscles on the cleft.6 Therefore, the incision often is made off-midline from the gluteal cleft even when the cyst lies directly on the gluteal cleft.

Rates of healing vary widely after incision and drainage, ranging from 45% to 82%.6 Primary pilonidal cysts may respond well, particularly if the cavity is abraded; in one series, 79% (58/73) of patients did not have a recurrence at the average follow-up of 60 months.16

Excision and Unroofing

Techniques for excision and unroofing without primary closure include 2 variants: wide and limited. The wide technique consists of an inwardly slanted excision that is deepest in the center of the cavity. The inward sloping angle of the incision aids in healing because it allows granulation to progress evenly from the base of the wound upward. The depth of the incision should spare the fascia and leave as much fatty tissue as possible while still resecting the entire cavity and associated pits.6 Limited incision techniques aim to shorten the healing period by making smaller incisions into the sinuses, pits, and secondary tracts, and they are frequently supplemented with curettage.6 Noteworthy disadvantages include prolonged healing time, need for professional wound management, and extended medical observation.5 The average duration of wound healing in a study of 300 patients was 5.4 weeks (range, +/−1.1 weeks),17 and the recurrence rate has ranged from 5% to 13%.18,19 Care must be taken to respond to numerous possible complications, including excessive exudation and granulation, superinfection, and walling off.6

Although the cost of treatment varies by hospital, location, and a patient’s insurance coverage, patient reports to the Pilonidal Support Alliance indicate that the cost of conservative management ranges from $500 to $2000.20

Excision and Primary Closure

An elliptical excision that includes some of the lateral margin is excised down to the level of the fascia. Adjacent lateral tracts may be excised by expanding the incision. To close the wound, edges are approximated with placement of deep and superficial sutures. Wound healing typically occurs faster than secondary granulation, as seen in one randomized controlled trial with a mean of 10 days for primary closure compared to 13 weeks for secondary intention.21 However, as with any surgical procedure, postoperative complications can delay wound healing.19 The recurrence rate after primary closure varies considerably, ranging from 10% to 38%.18,21-23 The average cost of an excision ranges from $3000 to $6000.20

A

Surgical Techniques

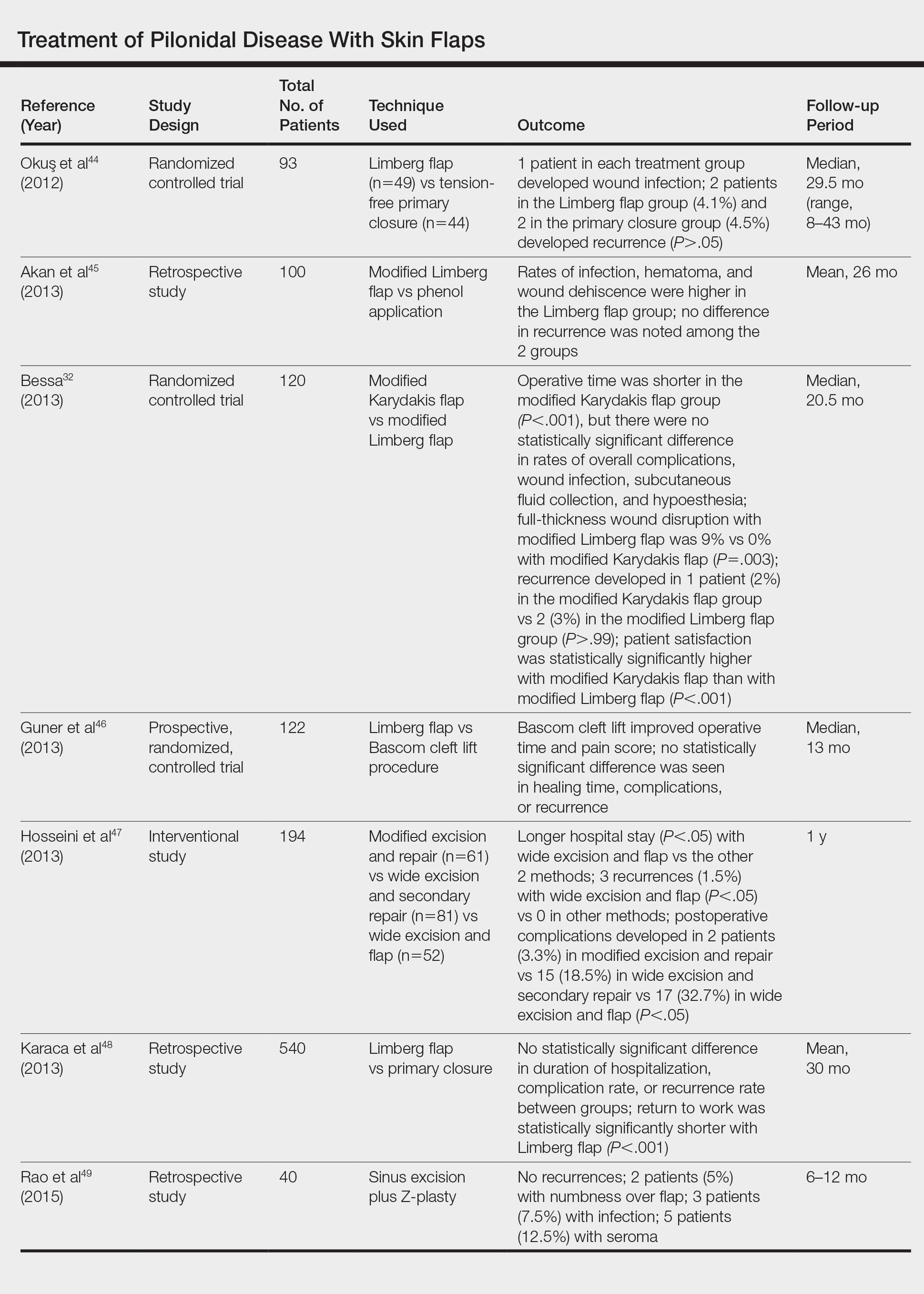

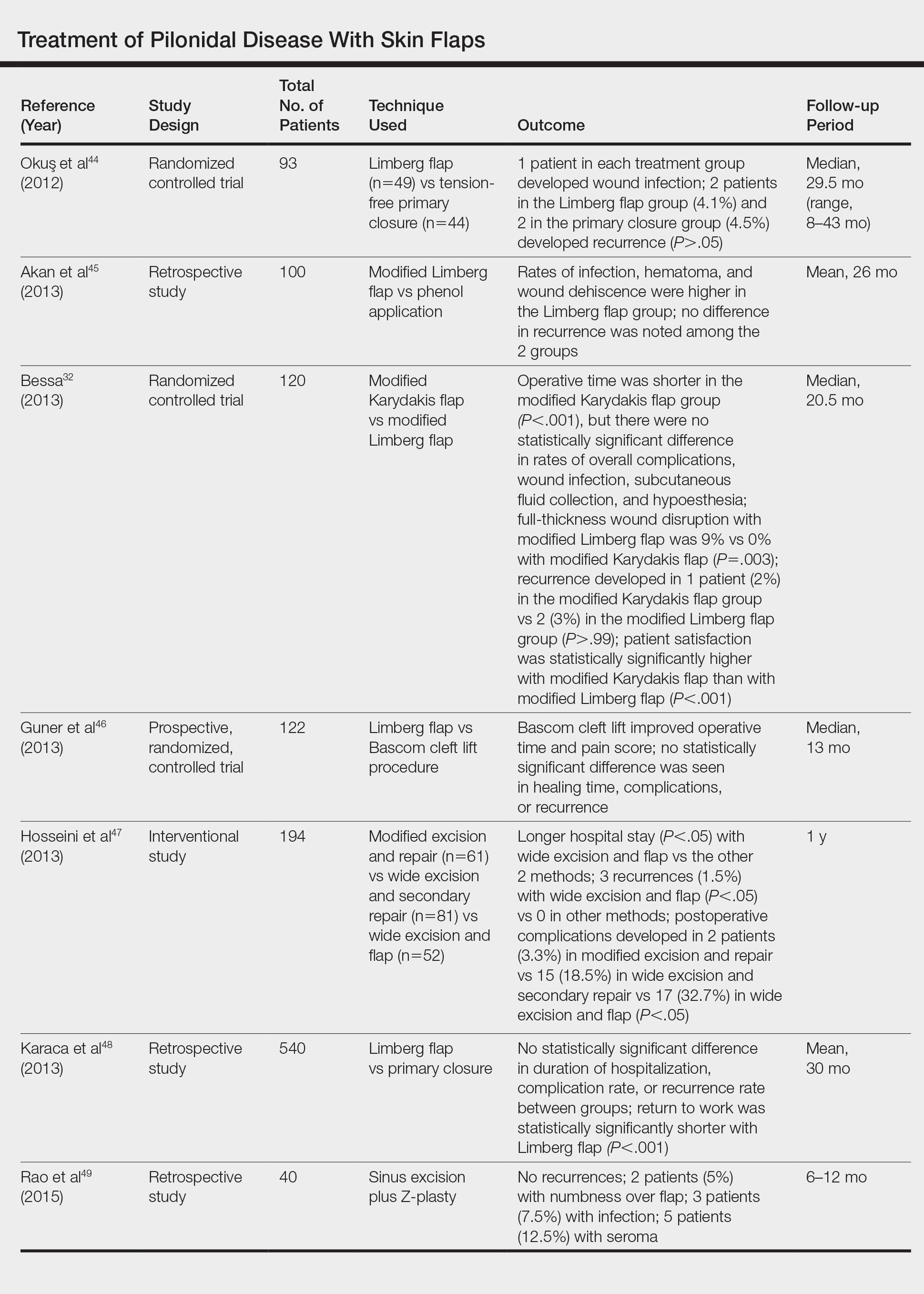

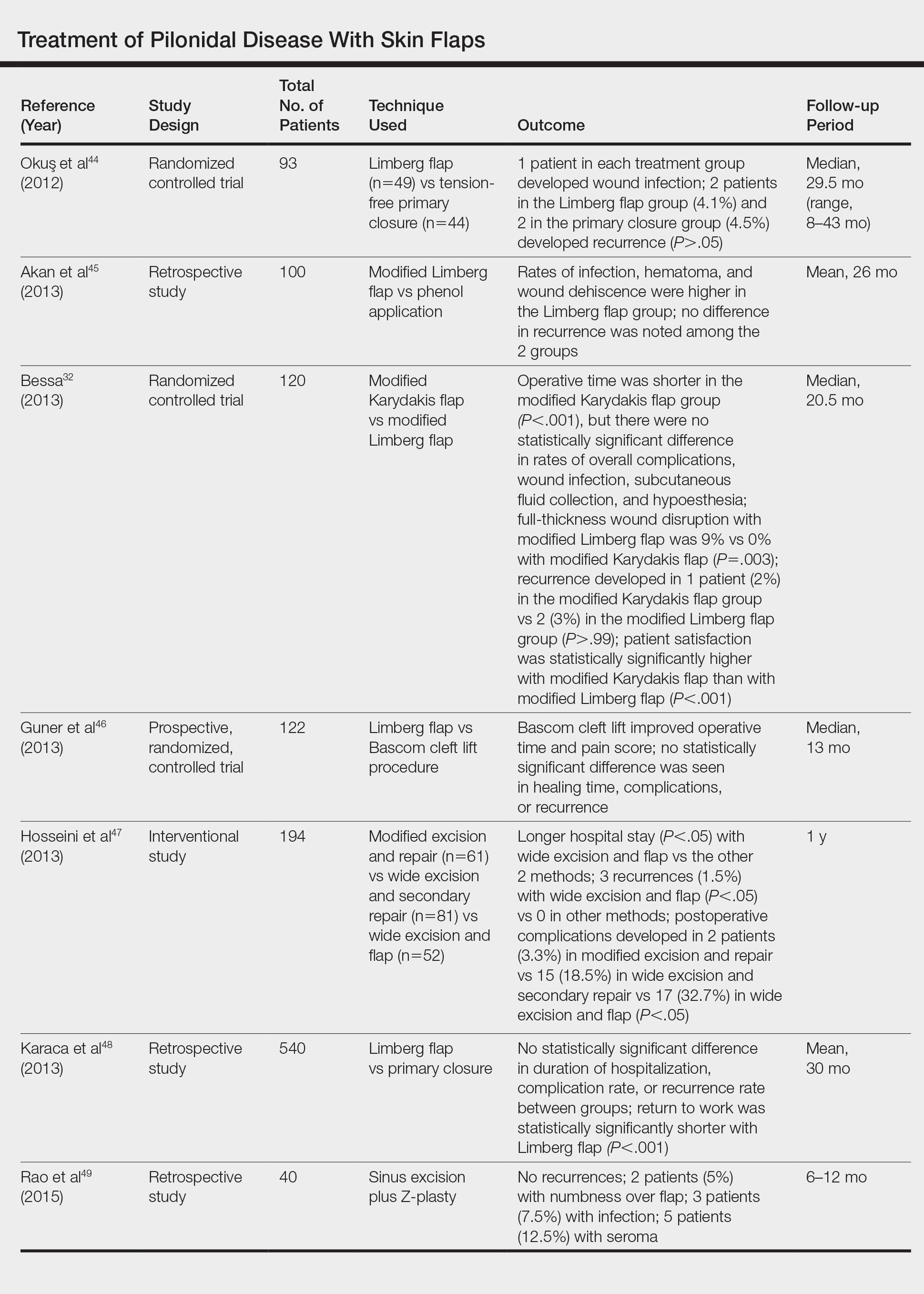

For severe or recurrent pilonidal disease, skin flaps often are required. Several flaps have been developed, including advancement, Bascom cleft lift, Karydakis, and modified Limberg flap. Flaps require a vascular pedicle but allow for closure without tension.26 The cost of a flap procedure, ranging from $10,000 to $30,000, is greater than the cost of excision or other conservative therapy20; however, with a lower recurrence rate of pilonidal disease following flap procedures compared to other treatments, patients may save more on treatment over the long-term.

Advancement Flaps

The most commonly used advancement flaps are the V-Y advancement flap and Z-plasty. The V-Y advancement flap creates a full-thickness V-shaped incision down to gluteal fascia that is closed to form a postrepair suture line in the shape of a Y.5 Depending on the size of the defect, the flaps may be utilized unilaterally or bilaterally. A defect as large as 8 to 10 cm can be covered unilaterally; however, defects larger than 10 cm commonly require a bilateral flap.26 The V-Y advancement flap failed to show superiority to primary closure techniques based on complications, recurrence, and patient satisfaction in a large randomized controlled trial.27

Performing a Z-plasty requires excision of diseased tissue with recruitment of lateral flaps incised down to the level of the fascia. The lateral edges are transposed to increase transverse length.26 No statistically significant difference in infection or recurrence rates was noted between excision alone and excision plus Z-plasty; however, wounds were reported to heal faster in patients receiving excision plus Z-plasty (41 vs 15 days).28

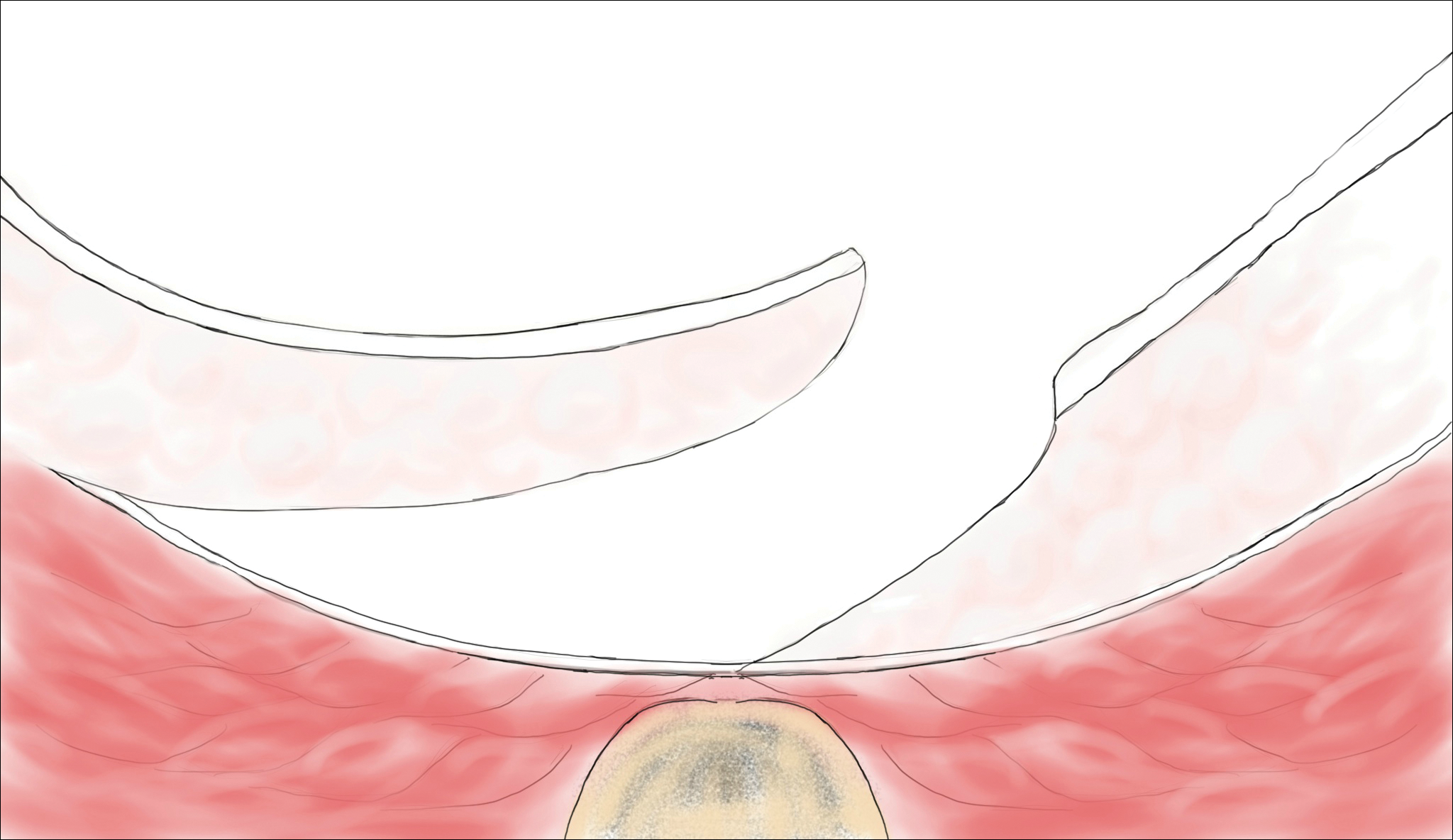

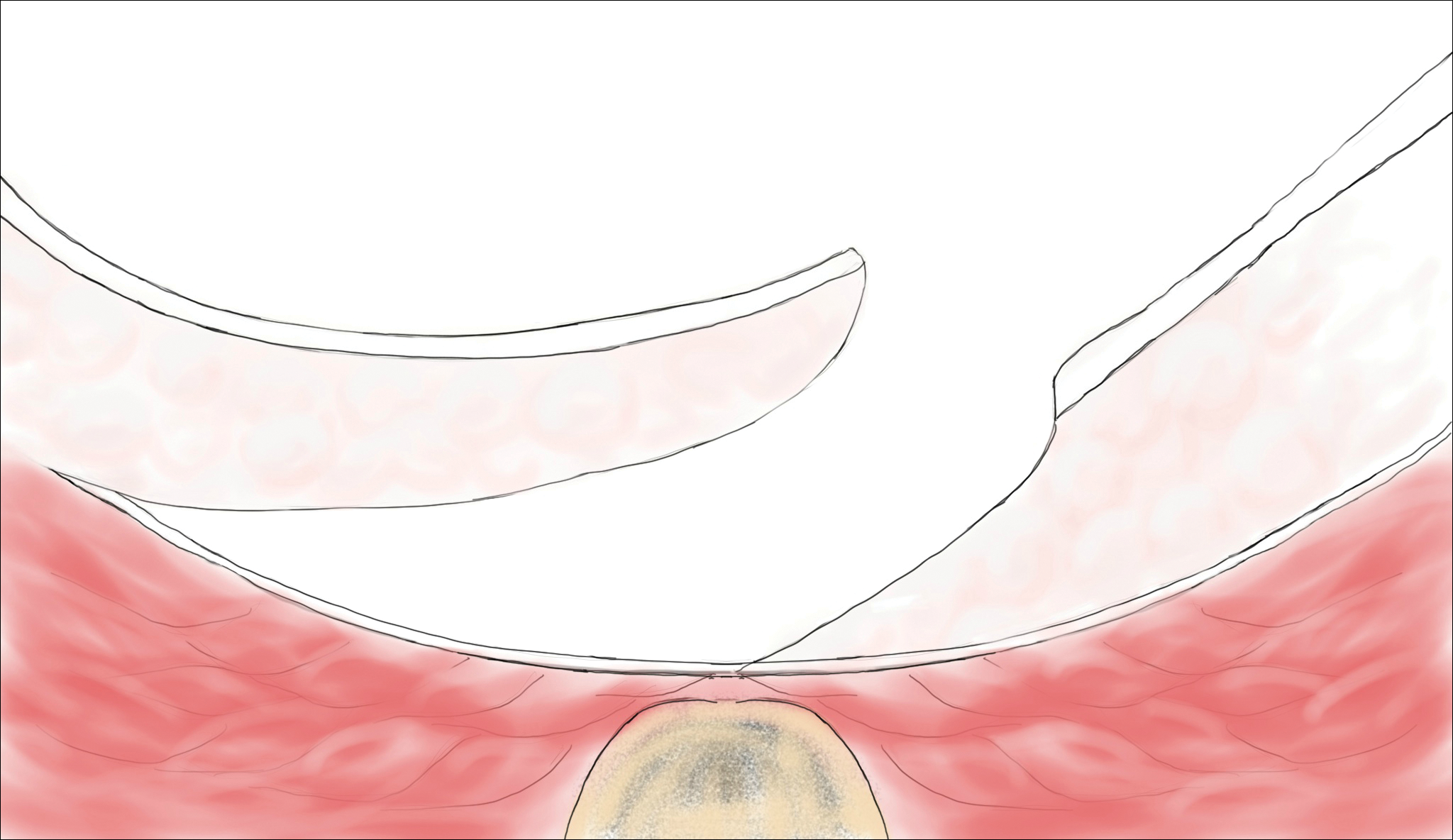

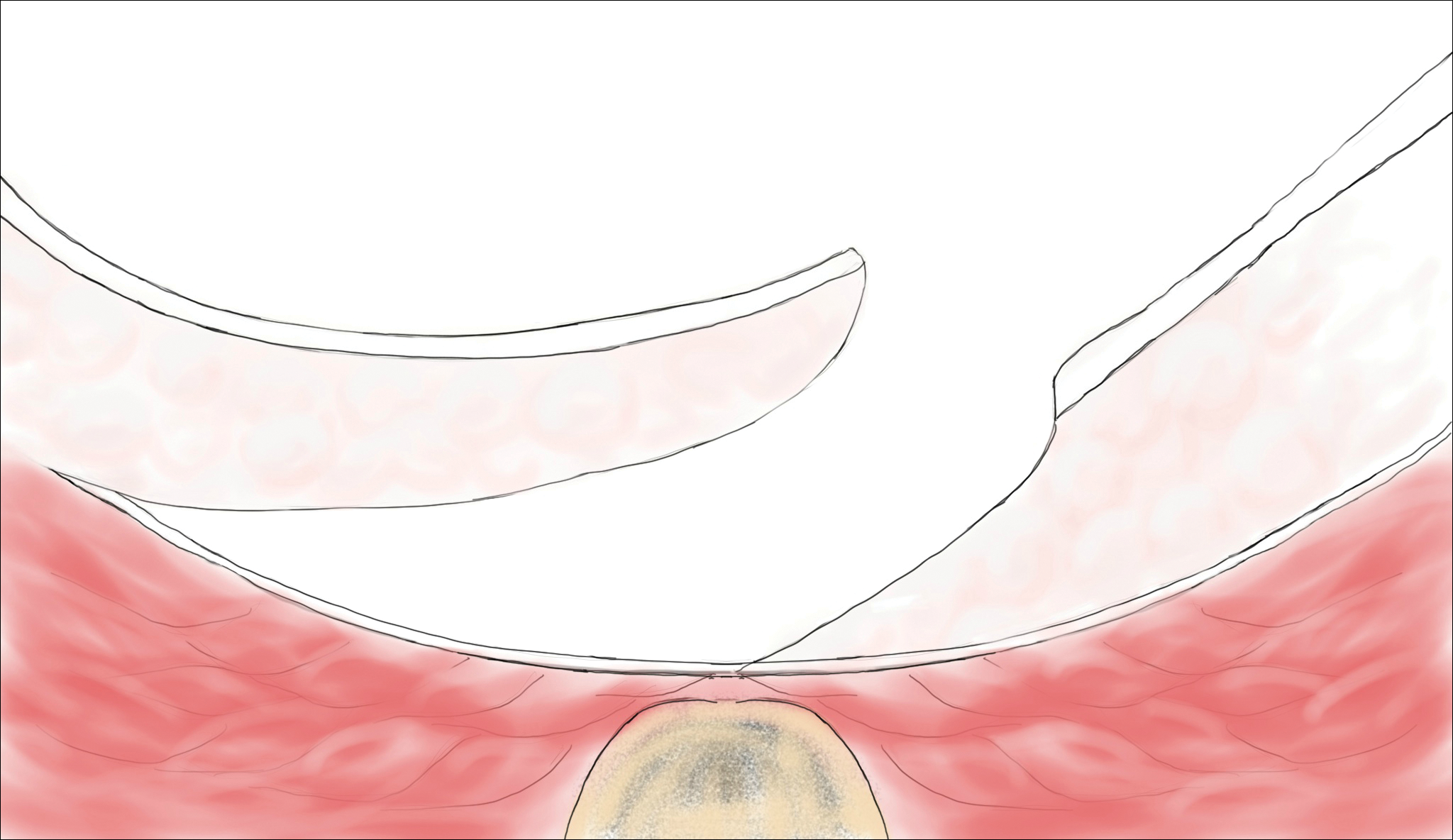

Cleft Lift Closure

In 1987, Bascom29 introduced the cleft lift closure for recurrent pilonidal disease. This technique aims to reduce or eliminate lateral gluteal forces on the wounds by filling the gluteal cleft.5 The sinus tracts are excised and a full-thickness skin flap is extended across the cleft and closed off-midline. The adipose tissue fills in the previous space of the gluteal cleft. In the initial study, no recurrences were reported in 30 patients who underwent this procedure at 2-year follow-up; similarly, in another case series of 26 patients who underwent the procedure, no recurrences were noted at a median follow-up of 3 years.30 Compared to excision with secondary wound healing and primary closure on the midline, the Bascom cleft lift demonstrated a decrease in wound healing time (62, 52, and 29 days, respectively).31

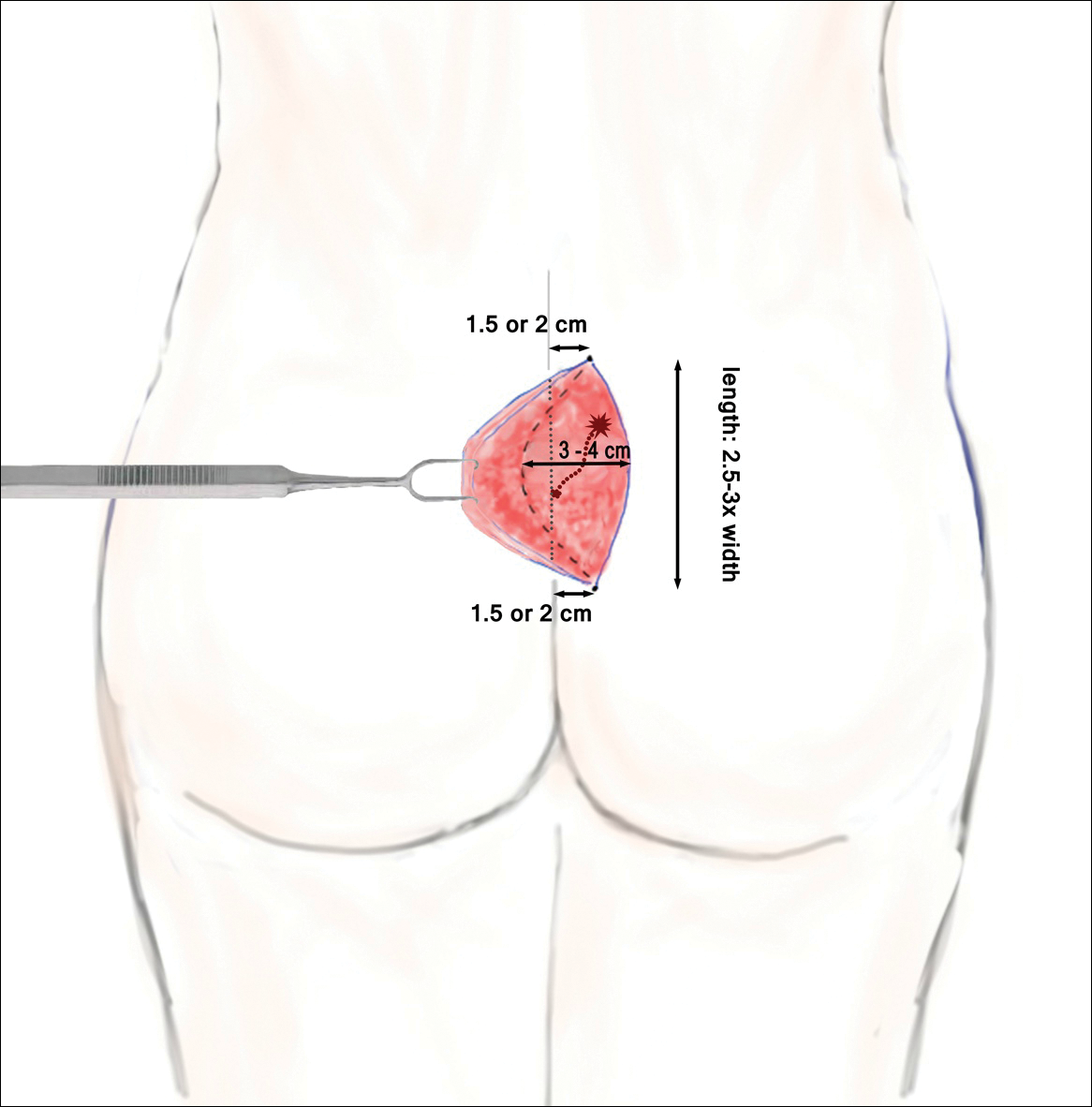

The classic Karydakis flap consists of an oblique elliptical excision of diseased tissue with fixation of the flap base to the sacral fascia (Figures 4 and 5). The flap is closed by suturing the edge off-midline.32 This technique prevents a midline wound and aims to remodel and flatten the natal cleft. Karydakis33 performed the most important study for treatment of pilonidal disease with the Karydakis flap, which included more than 5000 patients. The results showed a 0.9% recurrence rate and an 8.5% wound complication rate over a 2- to 20-year follow-up.33 These results have been substantiated by more recent studies, which produced similar results: a 1.8% to 5.3% infection rate and a recurrence rate of 0.9% to 4.4%.34,35

In the modified Karydakis flap, the same excision and closure is performed without tacking the flap to the sacral fascia, aiming to prevent formation of a new vulnerable raphe by flattening the natal cleft. The infection rate was similar to the classic Karydakis flap, and no recurrences were noted during a 20-month follow-up.36

Limberg Flap

The Limberg flap is derived from a rhomboid flap. In the classic Limberg flap, a midline rhomboid incision to the presacral fascia including the sinus is performed. The flap gains mobility by extending the excision laterally to the fascia of the gluteus maximus muscle. A variant of the original flap includes the modified Limberg flap, which lateralizes the midline sutures and flattens the intergluteal sulcus. Compared to the traditional Limberg approach, the modified Limberg flap was associated with a lower failure rate at both early and late time points and a lower rate of infection37,38; however, based on the data it is unclear when primary closure should be favored over a Limberg flap. Several studies show the recurrence rate to be identical; however, hospital stay and pain were reduced in the Limberg flap group compared to primary closure.39,40

Results from randomized controlled trials comparing the modified Limberg flap to the Karydakis flap vary. One of the largest prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing the 2 flaps included 269 patients.Results showed a lower postoperative complication rate, lower pain scores, shorter operation time, and shorter hospital stay with the Karydakis flap compared to the Limberg flap, though no difference in recurrence was noted between the 2 groups.41

Tw

Overall, larger prospective trials are needed to clarify the differences in outcomes between flap techniques. In

Laser Therapy

Lasers are emerging as primary and adjuvant treatment options for pilonidal sinuses. Depilation with alexandrite, diode, and Nd:YAG lasers has demonstrated the most consistent evidence.50-54 Th

Large randomized controlled trials are needed to fully determine the utility of laser therapy as a primary or adjuvant treatment in pilonidal disease; however, given that laser therapies address the core pathogenesis of pilonidal disease and generally are well tolerated, their use may be strongly considered.

Conclusion

With mild pilonidal disease, more conservative measures can be employed; however, in cases of recurrent or suppurative disease or extensive scarring, excision with flap closure typically is required. Although no single surgical procedure has been identified as superior, one review demonstrated that off-midline procedures are statistically superior to midline closure in healing time, surgical site infection, and recurrence rate.24 Novel techniques continue to emerge in the management of pilonidal disease, including laser therapy. This modality shows promise as either a primary or adjuvant treatment; however, large randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm early findings.

Given that pilonidal disease most commonly occurs in the actively employed population, we recommend that dermatologic surgeons discuss treatment options with patients who have pilonidal disease, taking into consideration cost, length of hospital stay, and recovery time when deciding on a treatment course.

- Mayo OH. Observations on Injuries and Diseases of the Rectum. London, England: Burgess and Hill; 1833.

- Hodges RM. Pilonidal sinus. Boston Med Surg J. 1880;103:485-486.

- Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Ozkan OV, et al. Interdigital pilonidal sinus: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1400-1403.

- Stone MS. Cysts with a lining of stratified epithelium. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Limited; 2012:1917-1929.

- Khanna A, Rombeau JL. Pilonidal disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:46-53.

- de Parades V, Bouchard D, Janier M, et al. Pilonidal sinus disease. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:237-247.

- Harris CL, Laforet K, Sibbald RG, et al. Twelve common mistakes in pilonidal sinus care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:325-332.

- Lindholt-Jensen C, Lindholt J, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG laser treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Oueidat D, Rizkallah A, Dirani M, et al. 25 years’ experience in the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Open J Gastro. 2014;4:1-5.

- Gordon P, Grant L, Irwin T. Recurrent pilonidal sepsis. Ulster Med J. 2014;83:10-12.

- Ardelt M, Dittmar Y, Kocijan R, et al. Microbiology of the infected recurrent sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Int Wound J. 2016;13:231-237.

- Eryilmaz R, Bilecik T, Okan I, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma arising in a neglected pilonidal sinus: report of a case and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:446-450.

- Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Review of phenol treatment in sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:189-193.

- Dag A, Colak T, Turkmenoglu O, et al. Phenol procedure for pilonidal sinus disease and risk factors for treatment failure. Surgery. 2012;151:113-117.

- Olmez A, Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Treatment of pilonidal disease by combination of pit excision and phenol application. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:201-206.

- Jensen SL, Harling H. Prognosis after simple incision and drainage for a first-episode acute pilonidal abscess. Br J Surg. 1988;75:60-61.

- Kepenekci I, Demirkan A, Celasin H, et al. Unroofing and curettage for the treatment of acute and chronic pilonidal disease. World J Surg. 2010;34:153-157.

- Søndenaa K, Nesvik I, Anderson E, et al. Recurrent pilonidal sinus after excision with closed or open treatment: final results of a randomized trial. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:237-240.

- Spivak H, Brooks VL, Nussbaum M, et al. Treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1136-1139.

- Pilonidal surgery costs. Pilonidal Support Alliance website. https://www.pilonidal.org/treatments/surgical-costs/. Updated January 30, 2016. Accessed October 14, 2018.21. al-Hassan HK, Francis IM, Neglén P. Primary closure or secondary granulation after excision of pilonidal sinus? Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:695-699.

- Khaira HS, Brown JH. Excision and primary suture of pilonidal sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:242-244.

- Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the post anal (pilonidal) sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:201-203.

- Al-Khamis A, McCallum I, King PM, et al. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD006213.

- McCallum I, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:868-871.

- Lee PJ, Raniga S, Biyani DK, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Colorect Dis. 2008;10:639-650.

- Nursal TZ, Ezer A, Calişkan K, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing V-Y advancement flaps with primary suture methods in pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;199:170-177.

- Fazeli MS, Adel MG, Lebaschi AH. Comparison of outcomes in Z-plasty and delayed healing by secondary intention of the wound after excision in the sacral pilonidal sinus: results of a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Col Rectum. 2006;49:1831-1836.

- Bascom JU. Repeat pilonidal operations. Am J Surg. 1987;154:118-122.

- Nordon IM, Senapati A, Cripps NP. A prospective randomized controlled trial of simple Bascom’s technique versus Bascom’s cleft closure in the treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2009;197:189-192.

- Dudnik R, Veldkamp J, Nienhujis S, et al. Secondary healing versus midline closure and modified Bascom natal cleft lift for pilonidal sinus disease. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:110-113.

- Bessa SS. Comparison of short-term results between the modified Karydakis flap and the modified Limberg flap in the management of pilonidal sinus disease: a randomized controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:491-498.

- Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:385-389.

- Kitchen PR. Pilonidal sinus: excision and primary closure with a lateralised wound - the Karydakis operation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1982;52:302-305.

- Akinci OF, Coskun A, Uzunköy A. Simple and effective surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus: asymmetric excision and primary closure using suction drain and subcuticular skin closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:701-706.

- Bessa SS. Results of the lateral advancing flap operation (modified Karydakis procedure) for the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1935-1940.

- Mentes BB, Leventoglu S, Chin A, et al. Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Surg Today. 2004;34:419-423.

- Cihan A, Ucan BH, Comert M, et al. Superiority of asymmetric modified Limberg flap for surgical treatment of pilonidal cyst disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:244-249.

- Muzi MG, Milito G, Cadeddu F, et al. Randomized comparison of Limberg flap versus modified primary closure for treatment of pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:9-14.

- Tavassoli A, Noorshafiee S, Nazarzadeh R. Comparison of excision with primary repair versus Limberg flap. Int J Surg. 2011;9:343-346.

- Ates M, Dirican A, Sarac M, et al. Short and long-term results of the Karydakis flap versus the Limberg flap for treating pilonidal sinus disease: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2011;202:568-573.

- Can MF, Sevinc MM, Hancerliogullari O, et al. Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with saccrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:318-327.

- Ersoy E, Devay AO, Aktimur R, et al. Comparison of short-term results after Limberg and Karydakis procedures for pilonidal disease: randomized prospective analysis of 100 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:705-710.

- Okuş A, Sevinç B, Karahan O, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and tension-free primary closure during pilonidal sinus surgery. World J Surg. 2012;36:431-435.

- Akan K, Tihan D, Duman U, et al. Comparison of surgical Limberg flap technique and crystallized phenol application in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a retrospective study. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2013;29:162-166.

- Guner A, Boz A, Ozkan OF, et al. Limberg flap versus Bascom cleft lift techniques for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: prospective, randomized trial. World J Surg. 2013;37:2074-2080.

- Hosseini H, Heidari A, Jafarnejad B. Comparison of three surgical methods in treatment of patients with pilonidal sinus: modified excision and repair/wide excision/wide excision and flap in RASOUL, OMID and SADR hospitals (2004-2007). Indian J Surg. 2013;75:395-400.

- Karaca AS, Ali R, Capar M, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease, in terms of quality of life and complications. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:236-239.

- Rao J, Deora H, Mandia R. A retrospective study of 50 cases of pilonidal sinus with excision of tract and Z-plasty as treatment of choice for both primary and recurrent cases. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(suppl 2):691-693.

- Landa N, Aller O, Landa-Gundin N, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent pilonidal sinus with laser epilation. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:726-728.

- Oram Y, Kahraman D, Karincaoğlu Y, et al. Evaluation of 60 patients with pilonidal sinus treated with laser epilation after surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:88-91.

- Benedetto AV, Lewis AT. Pilonidal sinus disease treated by depilation using an 800 nm diode laser and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:587-591.

- Lindholt-Jensen CS, Lindholt JS, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Jain V, Jain A. Use of lasers for the management of refractory cases of hidradenitis suppurativa and pilonidal sinus. J Cutan Aesthet. 2012;5:190-192.

Pilonidal disease was first described by Mayo1 in 1833 who hypothesized that the underlying etiology is incomplete separation of the mesoderm and ectoderm layers during embryogenesis. In 1880, Hodges2 coined the term pilonidal sinus; he postulated that sinus formation was incited by hair.2 Today, Hodges theory is known as the acquired theory: hair induces a foreign body response in surrounding tissue, leading to sinus formation. Although pilonidal cysts can occur anywhere on the body, they most commonly extend cephalad in the sacrococcygeal and upper gluteal cleft (Figure 1).3,4 An acute pilonidal cyst typically presents with pain, tenderness, and swelling, similar to the presentation of a superficial abscess in other locations; however, a clue to the diagnosis is the presence of cutaneous pits along the midline of the gluteal cleft.5 Chronic pilonidal disease varies based on the extent of inflammation and scarring; the underlying cavity communicates with the overlying skin through sinuses and often drains with pressure.6

Pilonidal sinuses are rare before puberty or after 40 years of age7 and occur primarily in hirsute men. The ratio of men to women affected is between 3:1 and 4:1.8 Although pilonidal sinuses account for only 15% of anal suppurations, complications arising from pilonidal sinuses are a considerable cause of morbidity, resulting in loss of productivity in otherwise healthy individuals.9 Complications include chronic nonhealing wounds,10 as recurrent pilonidal sinuses tend to become colonized with gram-positive and facultative anaerobic bacteria, whereas primary pilonidal cysts more commonly become infected with anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria.11 Long-standing disease increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma arising within sinus tracts.10,12

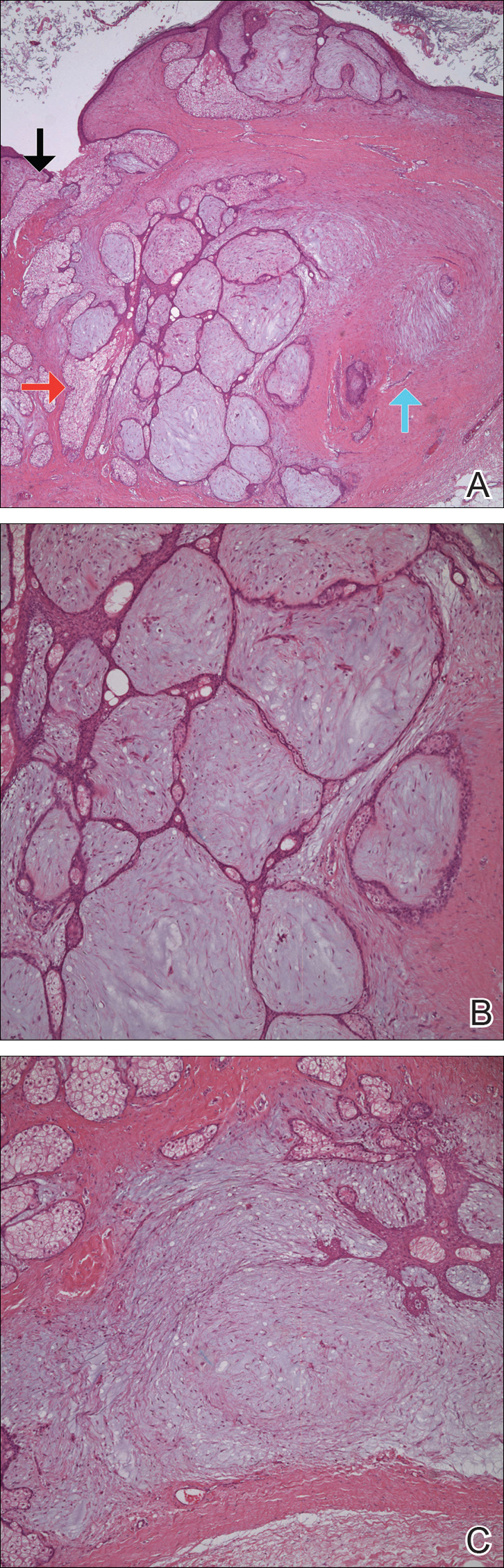

Histopathologically, pilonidal cysts are not true cysts because they lack an epithelial lining. Examination of the cavity commonly reveals hair, debris, and granulation tissue with surrounding foreign-body giant cells (Figure 2).5

The preferred treatment of pilonidal cysts continues to be debated. In this article, we review evidence supporting current modalities including conservative and surgical techniques as well as novel laser therapy for the treatment of pilonidal disease.

Conservative Management Techniques

Phenol Injections

Liquid or crystallized phenol injections have been used for treatment of mild to moderate pilonidal cysts.13 Excess debris is removed by curettage, and phenol is administered through the existing orifices or pits without pressure. The phenol remains in the cavity for 1 to 3 minutes before aspiration. Remaining cyst contents are removed through tissue manipulation, and the sinus is washed with saline. Mean healing time is 20 days (range, +/−14 days).13

Classically, phenol injections have a failure rate of 30% to 40%, especially with multiple sinuses and suppurative disease6; however, the success rate improves with limited disease (ie, no more than 1–3 sinus pits).3 With multiple treatment sessions, a recurrence rate as low as 2% over 25 months has been reported.14 Phenol injection also has been proposed as an adjuvant therapy to pit excision to minimize the need for extensive surgery.15

Simple Incision and Drainage

Simple incision and drainage has a crucial role in the treatment of acute pilonidal disease to decrease pain and relieve tension. Off-midline incisions have been recommended for because the resulting closures fared better against sheer forces applied by the gluteal muscles on the cleft.6 Therefore, the incision often is made off-midline from the gluteal cleft even when the cyst lies directly on the gluteal cleft.

Rates of healing vary widely after incision and drainage, ranging from 45% to 82%.6 Primary pilonidal cysts may respond well, particularly if the cavity is abraded; in one series, 79% (58/73) of patients did not have a recurrence at the average follow-up of 60 months.16

Excision and Unroofing

Techniques for excision and unroofing without primary closure include 2 variants: wide and limited. The wide technique consists of an inwardly slanted excision that is deepest in the center of the cavity. The inward sloping angle of the incision aids in healing because it allows granulation to progress evenly from the base of the wound upward. The depth of the incision should spare the fascia and leave as much fatty tissue as possible while still resecting the entire cavity and associated pits.6 Limited incision techniques aim to shorten the healing period by making smaller incisions into the sinuses, pits, and secondary tracts, and they are frequently supplemented with curettage.6 Noteworthy disadvantages include prolonged healing time, need for professional wound management, and extended medical observation.5 The average duration of wound healing in a study of 300 patients was 5.4 weeks (range, +/−1.1 weeks),17 and the recurrence rate has ranged from 5% to 13%.18,19 Care must be taken to respond to numerous possible complications, including excessive exudation and granulation, superinfection, and walling off.6

Although the cost of treatment varies by hospital, location, and a patient’s insurance coverage, patient reports to the Pilonidal Support Alliance indicate that the cost of conservative management ranges from $500 to $2000.20

Excision and Primary Closure

An elliptical excision that includes some of the lateral margin is excised down to the level of the fascia. Adjacent lateral tracts may be excised by expanding the incision. To close the wound, edges are approximated with placement of deep and superficial sutures. Wound healing typically occurs faster than secondary granulation, as seen in one randomized controlled trial with a mean of 10 days for primary closure compared to 13 weeks for secondary intention.21 However, as with any surgical procedure, postoperative complications can delay wound healing.19 The recurrence rate after primary closure varies considerably, ranging from 10% to 38%.18,21-23 The average cost of an excision ranges from $3000 to $6000.20

A

Surgical Techniques

For severe or recurrent pilonidal disease, skin flaps often are required. Several flaps have been developed, including advancement, Bascom cleft lift, Karydakis, and modified Limberg flap. Flaps require a vascular pedicle but allow for closure without tension.26 The cost of a flap procedure, ranging from $10,000 to $30,000, is greater than the cost of excision or other conservative therapy20; however, with a lower recurrence rate of pilonidal disease following flap procedures compared to other treatments, patients may save more on treatment over the long-term.

Advancement Flaps

The most commonly used advancement flaps are the V-Y advancement flap and Z-plasty. The V-Y advancement flap creates a full-thickness V-shaped incision down to gluteal fascia that is closed to form a postrepair suture line in the shape of a Y.5 Depending on the size of the defect, the flaps may be utilized unilaterally or bilaterally. A defect as large as 8 to 10 cm can be covered unilaterally; however, defects larger than 10 cm commonly require a bilateral flap.26 The V-Y advancement flap failed to show superiority to primary closure techniques based on complications, recurrence, and patient satisfaction in a large randomized controlled trial.27

Performing a Z-plasty requires excision of diseased tissue with recruitment of lateral flaps incised down to the level of the fascia. The lateral edges are transposed to increase transverse length.26 No statistically significant difference in infection or recurrence rates was noted between excision alone and excision plus Z-plasty; however, wounds were reported to heal faster in patients receiving excision plus Z-plasty (41 vs 15 days).28

Cleft Lift Closure

In 1987, Bascom29 introduced the cleft lift closure for recurrent pilonidal disease. This technique aims to reduce or eliminate lateral gluteal forces on the wounds by filling the gluteal cleft.5 The sinus tracts are excised and a full-thickness skin flap is extended across the cleft and closed off-midline. The adipose tissue fills in the previous space of the gluteal cleft. In the initial study, no recurrences were reported in 30 patients who underwent this procedure at 2-year follow-up; similarly, in another case series of 26 patients who underwent the procedure, no recurrences were noted at a median follow-up of 3 years.30 Compared to excision with secondary wound healing and primary closure on the midline, the Bascom cleft lift demonstrated a decrease in wound healing time (62, 52, and 29 days, respectively).31

The classic Karydakis flap consists of an oblique elliptical excision of diseased tissue with fixation of the flap base to the sacral fascia (Figures 4 and 5). The flap is closed by suturing the edge off-midline.32 This technique prevents a midline wound and aims to remodel and flatten the natal cleft. Karydakis33 performed the most important study for treatment of pilonidal disease with the Karydakis flap, which included more than 5000 patients. The results showed a 0.9% recurrence rate and an 8.5% wound complication rate over a 2- to 20-year follow-up.33 These results have been substantiated by more recent studies, which produced similar results: a 1.8% to 5.3% infection rate and a recurrence rate of 0.9% to 4.4%.34,35

In the modified Karydakis flap, the same excision and closure is performed without tacking the flap to the sacral fascia, aiming to prevent formation of a new vulnerable raphe by flattening the natal cleft. The infection rate was similar to the classic Karydakis flap, and no recurrences were noted during a 20-month follow-up.36

Limberg Flap

The Limberg flap is derived from a rhomboid flap. In the classic Limberg flap, a midline rhomboid incision to the presacral fascia including the sinus is performed. The flap gains mobility by extending the excision laterally to the fascia of the gluteus maximus muscle. A variant of the original flap includes the modified Limberg flap, which lateralizes the midline sutures and flattens the intergluteal sulcus. Compared to the traditional Limberg approach, the modified Limberg flap was associated with a lower failure rate at both early and late time points and a lower rate of infection37,38; however, based on the data it is unclear when primary closure should be favored over a Limberg flap. Several studies show the recurrence rate to be identical; however, hospital stay and pain were reduced in the Limberg flap group compared to primary closure.39,40

Results from randomized controlled trials comparing the modified Limberg flap to the Karydakis flap vary. One of the largest prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing the 2 flaps included 269 patients.Results showed a lower postoperative complication rate, lower pain scores, shorter operation time, and shorter hospital stay with the Karydakis flap compared to the Limberg flap, though no difference in recurrence was noted between the 2 groups.41

Tw

Overall, larger prospective trials are needed to clarify the differences in outcomes between flap techniques. In

Laser Therapy

Lasers are emerging as primary and adjuvant treatment options for pilonidal sinuses. Depilation with alexandrite, diode, and Nd:YAG lasers has demonstrated the most consistent evidence.50-54 Th

Large randomized controlled trials are needed to fully determine the utility of laser therapy as a primary or adjuvant treatment in pilonidal disease; however, given that laser therapies address the core pathogenesis of pilonidal disease and generally are well tolerated, their use may be strongly considered.

Conclusion

With mild pilonidal disease, more conservative measures can be employed; however, in cases of recurrent or suppurative disease or extensive scarring, excision with flap closure typically is required. Although no single surgical procedure has been identified as superior, one review demonstrated that off-midline procedures are statistically superior to midline closure in healing time, surgical site infection, and recurrence rate.24 Novel techniques continue to emerge in the management of pilonidal disease, including laser therapy. This modality shows promise as either a primary or adjuvant treatment; however, large randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm early findings.

Given that pilonidal disease most commonly occurs in the actively employed population, we recommend that dermatologic surgeons discuss treatment options with patients who have pilonidal disease, taking into consideration cost, length of hospital stay, and recovery time when deciding on a treatment course.

Pilonidal disease was first described by Mayo1 in 1833 who hypothesized that the underlying etiology is incomplete separation of the mesoderm and ectoderm layers during embryogenesis. In 1880, Hodges2 coined the term pilonidal sinus; he postulated that sinus formation was incited by hair.2 Today, Hodges theory is known as the acquired theory: hair induces a foreign body response in surrounding tissue, leading to sinus formation. Although pilonidal cysts can occur anywhere on the body, they most commonly extend cephalad in the sacrococcygeal and upper gluteal cleft (Figure 1).3,4 An acute pilonidal cyst typically presents with pain, tenderness, and swelling, similar to the presentation of a superficial abscess in other locations; however, a clue to the diagnosis is the presence of cutaneous pits along the midline of the gluteal cleft.5 Chronic pilonidal disease varies based on the extent of inflammation and scarring; the underlying cavity communicates with the overlying skin through sinuses and often drains with pressure.6

Pilonidal sinuses are rare before puberty or after 40 years of age7 and occur primarily in hirsute men. The ratio of men to women affected is between 3:1 and 4:1.8 Although pilonidal sinuses account for only 15% of anal suppurations, complications arising from pilonidal sinuses are a considerable cause of morbidity, resulting in loss of productivity in otherwise healthy individuals.9 Complications include chronic nonhealing wounds,10 as recurrent pilonidal sinuses tend to become colonized with gram-positive and facultative anaerobic bacteria, whereas primary pilonidal cysts more commonly become infected with anaerobic and gram-negative bacteria.11 Long-standing disease increases the risk of squamous cell carcinoma arising within sinus tracts.10,12

Histopathologically, pilonidal cysts are not true cysts because they lack an epithelial lining. Examination of the cavity commonly reveals hair, debris, and granulation tissue with surrounding foreign-body giant cells (Figure 2).5

The preferred treatment of pilonidal cysts continues to be debated. In this article, we review evidence supporting current modalities including conservative and surgical techniques as well as novel laser therapy for the treatment of pilonidal disease.

Conservative Management Techniques

Phenol Injections

Liquid or crystallized phenol injections have been used for treatment of mild to moderate pilonidal cysts.13 Excess debris is removed by curettage, and phenol is administered through the existing orifices or pits without pressure. The phenol remains in the cavity for 1 to 3 minutes before aspiration. Remaining cyst contents are removed through tissue manipulation, and the sinus is washed with saline. Mean healing time is 20 days (range, +/−14 days).13

Classically, phenol injections have a failure rate of 30% to 40%, especially with multiple sinuses and suppurative disease6; however, the success rate improves with limited disease (ie, no more than 1–3 sinus pits).3 With multiple treatment sessions, a recurrence rate as low as 2% over 25 months has been reported.14 Phenol injection also has been proposed as an adjuvant therapy to pit excision to minimize the need for extensive surgery.15

Simple Incision and Drainage

Simple incision and drainage has a crucial role in the treatment of acute pilonidal disease to decrease pain and relieve tension. Off-midline incisions have been recommended for because the resulting closures fared better against sheer forces applied by the gluteal muscles on the cleft.6 Therefore, the incision often is made off-midline from the gluteal cleft even when the cyst lies directly on the gluteal cleft.

Rates of healing vary widely after incision and drainage, ranging from 45% to 82%.6 Primary pilonidal cysts may respond well, particularly if the cavity is abraded; in one series, 79% (58/73) of patients did not have a recurrence at the average follow-up of 60 months.16

Excision and Unroofing

Techniques for excision and unroofing without primary closure include 2 variants: wide and limited. The wide technique consists of an inwardly slanted excision that is deepest in the center of the cavity. The inward sloping angle of the incision aids in healing because it allows granulation to progress evenly from the base of the wound upward. The depth of the incision should spare the fascia and leave as much fatty tissue as possible while still resecting the entire cavity and associated pits.6 Limited incision techniques aim to shorten the healing period by making smaller incisions into the sinuses, pits, and secondary tracts, and they are frequently supplemented with curettage.6 Noteworthy disadvantages include prolonged healing time, need for professional wound management, and extended medical observation.5 The average duration of wound healing in a study of 300 patients was 5.4 weeks (range, +/−1.1 weeks),17 and the recurrence rate has ranged from 5% to 13%.18,19 Care must be taken to respond to numerous possible complications, including excessive exudation and granulation, superinfection, and walling off.6

Although the cost of treatment varies by hospital, location, and a patient’s insurance coverage, patient reports to the Pilonidal Support Alliance indicate that the cost of conservative management ranges from $500 to $2000.20

Excision and Primary Closure

An elliptical excision that includes some of the lateral margin is excised down to the level of the fascia. Adjacent lateral tracts may be excised by expanding the incision. To close the wound, edges are approximated with placement of deep and superficial sutures. Wound healing typically occurs faster than secondary granulation, as seen in one randomized controlled trial with a mean of 10 days for primary closure compared to 13 weeks for secondary intention.21 However, as with any surgical procedure, postoperative complications can delay wound healing.19 The recurrence rate after primary closure varies considerably, ranging from 10% to 38%.18,21-23 The average cost of an excision ranges from $3000 to $6000.20

A

Surgical Techniques

For severe or recurrent pilonidal disease, skin flaps often are required. Several flaps have been developed, including advancement, Bascom cleft lift, Karydakis, and modified Limberg flap. Flaps require a vascular pedicle but allow for closure without tension.26 The cost of a flap procedure, ranging from $10,000 to $30,000, is greater than the cost of excision or other conservative therapy20; however, with a lower recurrence rate of pilonidal disease following flap procedures compared to other treatments, patients may save more on treatment over the long-term.

Advancement Flaps

The most commonly used advancement flaps are the V-Y advancement flap and Z-plasty. The V-Y advancement flap creates a full-thickness V-shaped incision down to gluteal fascia that is closed to form a postrepair suture line in the shape of a Y.5 Depending on the size of the defect, the flaps may be utilized unilaterally or bilaterally. A defect as large as 8 to 10 cm can be covered unilaterally; however, defects larger than 10 cm commonly require a bilateral flap.26 The V-Y advancement flap failed to show superiority to primary closure techniques based on complications, recurrence, and patient satisfaction in a large randomized controlled trial.27

Performing a Z-plasty requires excision of diseased tissue with recruitment of lateral flaps incised down to the level of the fascia. The lateral edges are transposed to increase transverse length.26 No statistically significant difference in infection or recurrence rates was noted between excision alone and excision plus Z-plasty; however, wounds were reported to heal faster in patients receiving excision plus Z-plasty (41 vs 15 days).28

Cleft Lift Closure

In 1987, Bascom29 introduced the cleft lift closure for recurrent pilonidal disease. This technique aims to reduce or eliminate lateral gluteal forces on the wounds by filling the gluteal cleft.5 The sinus tracts are excised and a full-thickness skin flap is extended across the cleft and closed off-midline. The adipose tissue fills in the previous space of the gluteal cleft. In the initial study, no recurrences were reported in 30 patients who underwent this procedure at 2-year follow-up; similarly, in another case series of 26 patients who underwent the procedure, no recurrences were noted at a median follow-up of 3 years.30 Compared to excision with secondary wound healing and primary closure on the midline, the Bascom cleft lift demonstrated a decrease in wound healing time (62, 52, and 29 days, respectively).31

The classic Karydakis flap consists of an oblique elliptical excision of diseased tissue with fixation of the flap base to the sacral fascia (Figures 4 and 5). The flap is closed by suturing the edge off-midline.32 This technique prevents a midline wound and aims to remodel and flatten the natal cleft. Karydakis33 performed the most important study for treatment of pilonidal disease with the Karydakis flap, which included more than 5000 patients. The results showed a 0.9% recurrence rate and an 8.5% wound complication rate over a 2- to 20-year follow-up.33 These results have been substantiated by more recent studies, which produced similar results: a 1.8% to 5.3% infection rate and a recurrence rate of 0.9% to 4.4%.34,35

In the modified Karydakis flap, the same excision and closure is performed without tacking the flap to the sacral fascia, aiming to prevent formation of a new vulnerable raphe by flattening the natal cleft. The infection rate was similar to the classic Karydakis flap, and no recurrences were noted during a 20-month follow-up.36

Limberg Flap

The Limberg flap is derived from a rhomboid flap. In the classic Limberg flap, a midline rhomboid incision to the presacral fascia including the sinus is performed. The flap gains mobility by extending the excision laterally to the fascia of the gluteus maximus muscle. A variant of the original flap includes the modified Limberg flap, which lateralizes the midline sutures and flattens the intergluteal sulcus. Compared to the traditional Limberg approach, the modified Limberg flap was associated with a lower failure rate at both early and late time points and a lower rate of infection37,38; however, based on the data it is unclear when primary closure should be favored over a Limberg flap. Several studies show the recurrence rate to be identical; however, hospital stay and pain were reduced in the Limberg flap group compared to primary closure.39,40

Results from randomized controlled trials comparing the modified Limberg flap to the Karydakis flap vary. One of the largest prospective, randomized, controlled trials comparing the 2 flaps included 269 patients.Results showed a lower postoperative complication rate, lower pain scores, shorter operation time, and shorter hospital stay with the Karydakis flap compared to the Limberg flap, though no difference in recurrence was noted between the 2 groups.41

Tw

Overall, larger prospective trials are needed to clarify the differences in outcomes between flap techniques. In

Laser Therapy

Lasers are emerging as primary and adjuvant treatment options for pilonidal sinuses. Depilation with alexandrite, diode, and Nd:YAG lasers has demonstrated the most consistent evidence.50-54 Th

Large randomized controlled trials are needed to fully determine the utility of laser therapy as a primary or adjuvant treatment in pilonidal disease; however, given that laser therapies address the core pathogenesis of pilonidal disease and generally are well tolerated, their use may be strongly considered.

Conclusion

With mild pilonidal disease, more conservative measures can be employed; however, in cases of recurrent or suppurative disease or extensive scarring, excision with flap closure typically is required. Although no single surgical procedure has been identified as superior, one review demonstrated that off-midline procedures are statistically superior to midline closure in healing time, surgical site infection, and recurrence rate.24 Novel techniques continue to emerge in the management of pilonidal disease, including laser therapy. This modality shows promise as either a primary or adjuvant treatment; however, large randomized controlled trials are needed to confirm early findings.

Given that pilonidal disease most commonly occurs in the actively employed population, we recommend that dermatologic surgeons discuss treatment options with patients who have pilonidal disease, taking into consideration cost, length of hospital stay, and recovery time when deciding on a treatment course.

- Mayo OH. Observations on Injuries and Diseases of the Rectum. London, England: Burgess and Hill; 1833.

- Hodges RM. Pilonidal sinus. Boston Med Surg J. 1880;103:485-486.

- Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Ozkan OV, et al. Interdigital pilonidal sinus: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1400-1403.

- Stone MS. Cysts with a lining of stratified epithelium. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Limited; 2012:1917-1929.

- Khanna A, Rombeau JL. Pilonidal disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:46-53.

- de Parades V, Bouchard D, Janier M, et al. Pilonidal sinus disease. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:237-247.

- Harris CL, Laforet K, Sibbald RG, et al. Twelve common mistakes in pilonidal sinus care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:325-332.

- Lindholt-Jensen C, Lindholt J, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG laser treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Oueidat D, Rizkallah A, Dirani M, et al. 25 years’ experience in the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Open J Gastro. 2014;4:1-5.

- Gordon P, Grant L, Irwin T. Recurrent pilonidal sepsis. Ulster Med J. 2014;83:10-12.

- Ardelt M, Dittmar Y, Kocijan R, et al. Microbiology of the infected recurrent sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Int Wound J. 2016;13:231-237.

- Eryilmaz R, Bilecik T, Okan I, et al. Recurrent squamous cell carcinoma arising in a neglected pilonidal sinus: report of a case and literature review. Int J Clin Exp Med. 2014;7:446-450.

- Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Review of phenol treatment in sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Tech Coloproctol. 2009;13:189-193.

- Dag A, Colak T, Turkmenoglu O, et al. Phenol procedure for pilonidal sinus disease and risk factors for treatment failure. Surgery. 2012;151:113-117.

- Olmez A, Kayaalp C, Aydin C. Treatment of pilonidal disease by combination of pit excision and phenol application. Tech Coloproctol. 2013;17:201-206.

- Jensen SL, Harling H. Prognosis after simple incision and drainage for a first-episode acute pilonidal abscess. Br J Surg. 1988;75:60-61.

- Kepenekci I, Demirkan A, Celasin H, et al. Unroofing and curettage for the treatment of acute and chronic pilonidal disease. World J Surg. 2010;34:153-157.

- Søndenaa K, Nesvik I, Anderson E, et al. Recurrent pilonidal sinus after excision with closed or open treatment: final results of a randomized trial. Eur J Surg. 1996;162:237-240.

- Spivak H, Brooks VL, Nussbaum M, et al. Treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 1996;39:1136-1139.

- Pilonidal surgery costs. Pilonidal Support Alliance website. https://www.pilonidal.org/treatments/surgical-costs/. Updated January 30, 2016. Accessed October 14, 2018.21. al-Hassan HK, Francis IM, Neglén P. Primary closure or secondary granulation after excision of pilonidal sinus? Acta Chir Scand. 1990;156:695-699.

- Khaira HS, Brown JH. Excision and primary suture of pilonidal sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1995;77:242-244.

- Clothier PR, Haywood IR. The natural history of the post anal (pilonidal) sinus. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 1984;66:201-203.

- Al-Khamis A, McCallum I, King PM, et al. Healing by primary versus secondary intention after surgical treatment for pilonidal sinus. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;1:CD006213.

- McCallum I, King PM, Bruce J. Healing by primary closure versus open healing after surgery for pilonidal sinus: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2008;336:868-871.

- Lee PJ, Raniga S, Biyani DK, et al. Sacrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Colorect Dis. 2008;10:639-650.

- Nursal TZ, Ezer A, Calişkan K, et al. Prospective randomized controlled trial comparing V-Y advancement flaps with primary suture methods in pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;199:170-177.

- Fazeli MS, Adel MG, Lebaschi AH. Comparison of outcomes in Z-plasty and delayed healing by secondary intention of the wound after excision in the sacral pilonidal sinus: results of a randomized, clinical trial. Dis Col Rectum. 2006;49:1831-1836.

- Bascom JU. Repeat pilonidal operations. Am J Surg. 1987;154:118-122.

- Nordon IM, Senapati A, Cripps NP. A prospective randomized controlled trial of simple Bascom’s technique versus Bascom’s cleft closure in the treatment of chronic pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2009;197:189-192.

- Dudnik R, Veldkamp J, Nienhujis S, et al. Secondary healing versus midline closure and modified Bascom natal cleft lift for pilonidal sinus disease. Scand J Surg. 2011;100:110-113.

- Bessa SS. Comparison of short-term results between the modified Karydakis flap and the modified Limberg flap in the management of pilonidal sinus disease: a randomized controlled study. Dis Colon Rectum. 2013;56:491-498.

- Karydakis GE. Easy and successful treatment of pilonidal sinus after explanation of its causative process. Aust N Z J Surg. 1992;62:385-389.

- Kitchen PR. Pilonidal sinus: excision and primary closure with a lateralised wound - the Karydakis operation. Aust N Z J Surg. 1982;52:302-305.

- Akinci OF, Coskun A, Uzunköy A. Simple and effective surgical treatment of pilonidal sinus: asymmetric excision and primary closure using suction drain and subcuticular skin closure. Dis Colon Rectum. 2000;43:701-706.

- Bessa SS. Results of the lateral advancing flap operation (modified Karydakis procedure) for the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2007;50:1935-1940.

- Mentes BB, Leventoglu S, Chin A, et al. Modified Limberg transposition flap for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus. Surg Today. 2004;34:419-423.

- Cihan A, Ucan BH, Comert M, et al. Superiority of asymmetric modified Limberg flap for surgical treatment of pilonidal cyst disease. Dis Colon Rectum. 2006;49:244-249.

- Muzi MG, Milito G, Cadeddu F, et al. Randomized comparison of Limberg flap versus modified primary closure for treatment of pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:9-14.

- Tavassoli A, Noorshafiee S, Nazarzadeh R. Comparison of excision with primary repair versus Limberg flap. Int J Surg. 2011;9:343-346.

- Ates M, Dirican A, Sarac M, et al. Short and long-term results of the Karydakis flap versus the Limberg flap for treating pilonidal sinus disease: a prospective randomized study. Am J Surg. 2011;202:568-573.

- Can MF, Sevinc MM, Hancerliogullari O, et al. Multicenter prospective randomized trial comparing modified Limberg flap transposition and Karydakis flap reconstruction in patients with saccrococcygeal pilonidal disease. Am J Surg. 2010;200:318-327.

- Ersoy E, Devay AO, Aktimur R, et al. Comparison of short-term results after Limberg and Karydakis procedures for pilonidal disease: randomized prospective analysis of 100 patients. Colorectal Dis. 2009;11:705-710.

- Okuş A, Sevinç B, Karahan O, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and tension-free primary closure during pilonidal sinus surgery. World J Surg. 2012;36:431-435.

- Akan K, Tihan D, Duman U, et al. Comparison of surgical Limberg flap technique and crystallized phenol application in the treatment of pilonidal sinus disease: a retrospective study. Ulus Cerrahi Derg. 2013;29:162-166.

- Guner A, Boz A, Ozkan OF, et al. Limberg flap versus Bascom cleft lift techniques for sacrococcygeal pilonidal sinus: prospective, randomized trial. World J Surg. 2013;37:2074-2080.

- Hosseini H, Heidari A, Jafarnejad B. Comparison of three surgical methods in treatment of patients with pilonidal sinus: modified excision and repair/wide excision/wide excision and flap in RASOUL, OMID and SADR hospitals (2004-2007). Indian J Surg. 2013;75:395-400.

- Karaca AS, Ali R, Capar M, et al. Comparison of Limberg flap and excision and primary closure of pilonidal sinus disease, in terms of quality of life and complications. J Korean Surg Soc. 2013;85:236-239.

- Rao J, Deora H, Mandia R. A retrospective study of 50 cases of pilonidal sinus with excision of tract and Z-plasty as treatment of choice for both primary and recurrent cases. Indian J Surg. 2015;77(suppl 2):691-693.

- Landa N, Aller O, Landa-Gundin N, et al. Successful treatment of recurrent pilonidal sinus with laser epilation. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:726-728.

- Oram Y, Kahraman D, Karincaoğlu Y, et al. Evaluation of 60 patients with pilonidal sinus treated with laser epilation after surgery. Dermatol Surg. 2010;36:88-91.

- Benedetto AV, Lewis AT. Pilonidal sinus disease treated by depilation using an 800 nm diode laser and review of the literature. Dermatol Surg. 2005;31:587-591.

- Lindholt-Jensen CS, Lindholt JS, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Jain V, Jain A. Use of lasers for the management of refractory cases of hidradenitis suppurativa and pilonidal sinus. J Cutan Aesthet. 2012;5:190-192.

- Mayo OH. Observations on Injuries and Diseases of the Rectum. London, England: Burgess and Hill; 1833.

- Hodges RM. Pilonidal sinus. Boston Med Surg J. 1880;103:485-486.

- Eryilmaz R, Okan I, Ozkan OV, et al. Interdigital pilonidal sinus: a case report and literature review. Dermatol Surg. 2012;38:1400-1403.

- Stone MS. Cysts with a lining of stratified epithelium. In: Bolognia JL, Jorizzo JL, Schaffer JV, eds. Dermatology. 3rd ed. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Limited; 2012:1917-1929.

- Khanna A, Rombeau JL. Pilonidal disease. Clin Colon Rectal Surg. 2011;24:46-53.

- de Parades V, Bouchard D, Janier M, et al. Pilonidal sinus disease. J Visc Surg. 2013;150:237-247.

- Harris CL, Laforet K, Sibbald RG, et al. Twelve common mistakes in pilonidal sinus care. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2012;25:325-332.

- Lindholt-Jensen C, Lindholt J, Beyer M, et al. Nd-YAG laser treatment of primary and recurrent pilonidal sinus. Lasers Med Sci. 2012;27:505-508.

- Oueidat D, Rizkallah A, Dirani M, et al. 25 years’ experience in the management of pilonidal sinus disease. Open J Gastro. 2014;4:1-5.

- Gordon P, Grant L, Irwin T. Recurrent pilonidal sepsis. Ulster Med J. 2014;83:10-12.