User login

Cutis is a peer-reviewed clinical journal for the dermatologist, allergist, and general practitioner published monthly since 1965. Concise clinical articles present the practical side of dermatology, helping physicians to improve patient care. Cutis is referenced in Index Medicus/MEDLINE and is written and edited by industry leaders.

ass lick

assault rifle

balls

ballsac

black jack

bleach

Boko Haram

bondage

causas

cheap

child abuse

cocaine

compulsive behaviors

cost of miracles

cunt

Daech

display network stats

drug paraphernalia

explosion

fart

fda and death

fda AND warn

fda AND warning

fda AND warns

feom

fuck

gambling

gfc

gun

human trafficking

humira AND expensive

illegal

ISIL

ISIS

Islamic caliphate

Islamic state

madvocate

masturbation

mixed martial arts

MMA

molestation

national rifle association

NRA

nsfw

nuccitelli

pedophile

pedophilia

poker

porn

porn

pornography

psychedelic drug

recreational drug

sex slave rings

shit

slot machine

snort

substance abuse

terrorism

terrorist

texarkana

Texas hold 'em

UFC

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden')]

section[contains(@class, 'nav-hidden active')

A peer-reviewed, indexed journal for dermatologists with original research, image quizzes, cases and reviews, and columns.

Cutaneous Metastasis of Endometrial Carcinoma: An Unusual and Dramatic Presentation

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

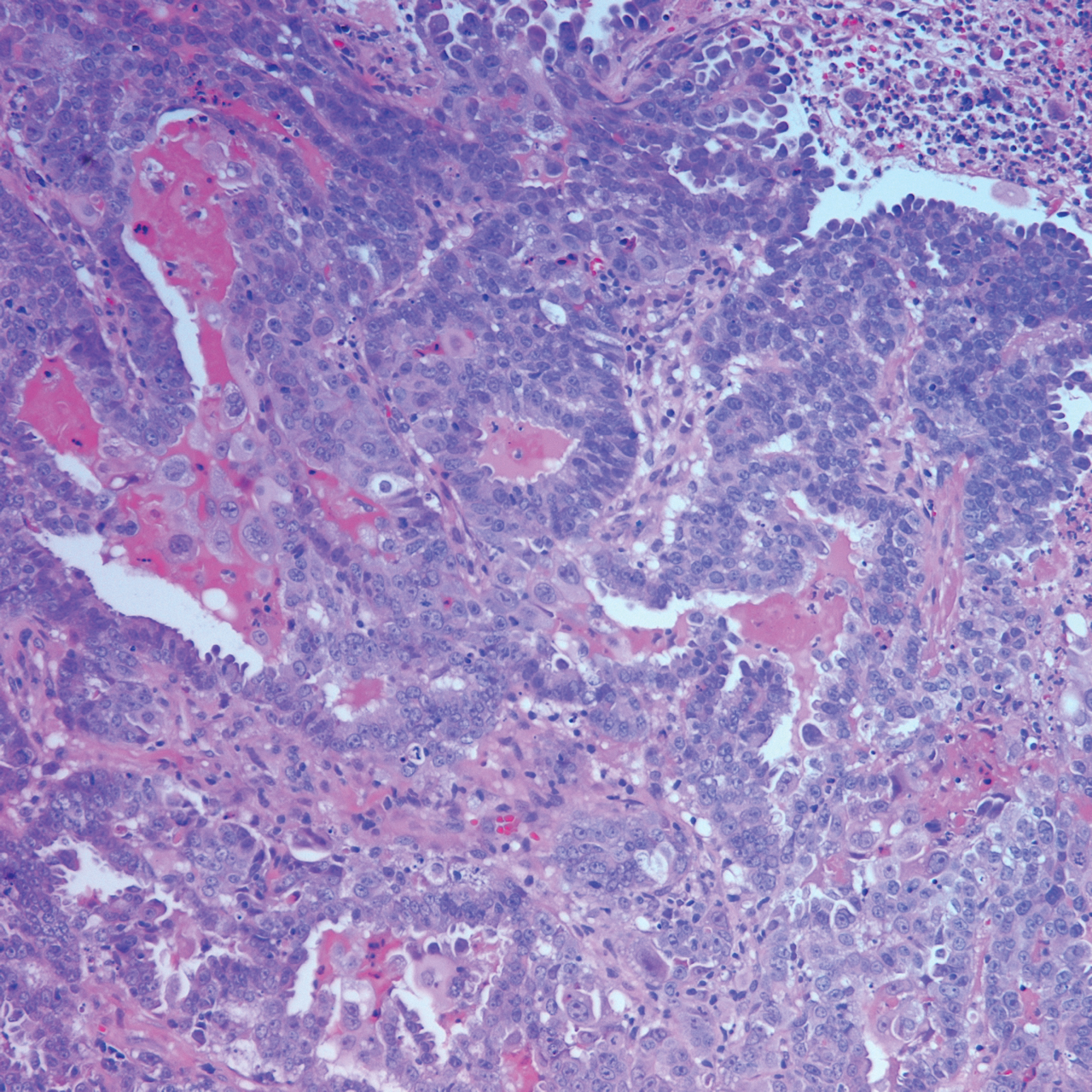

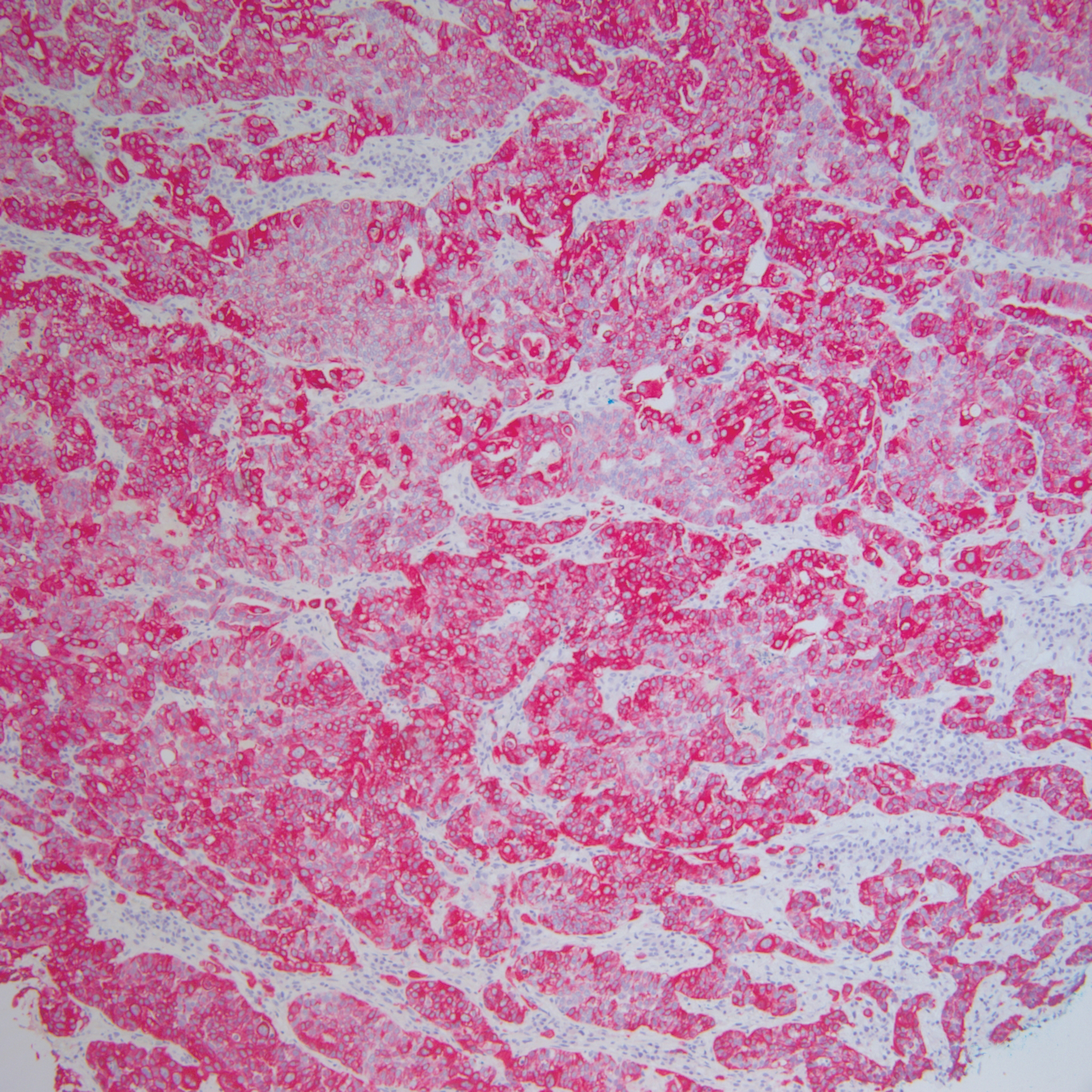

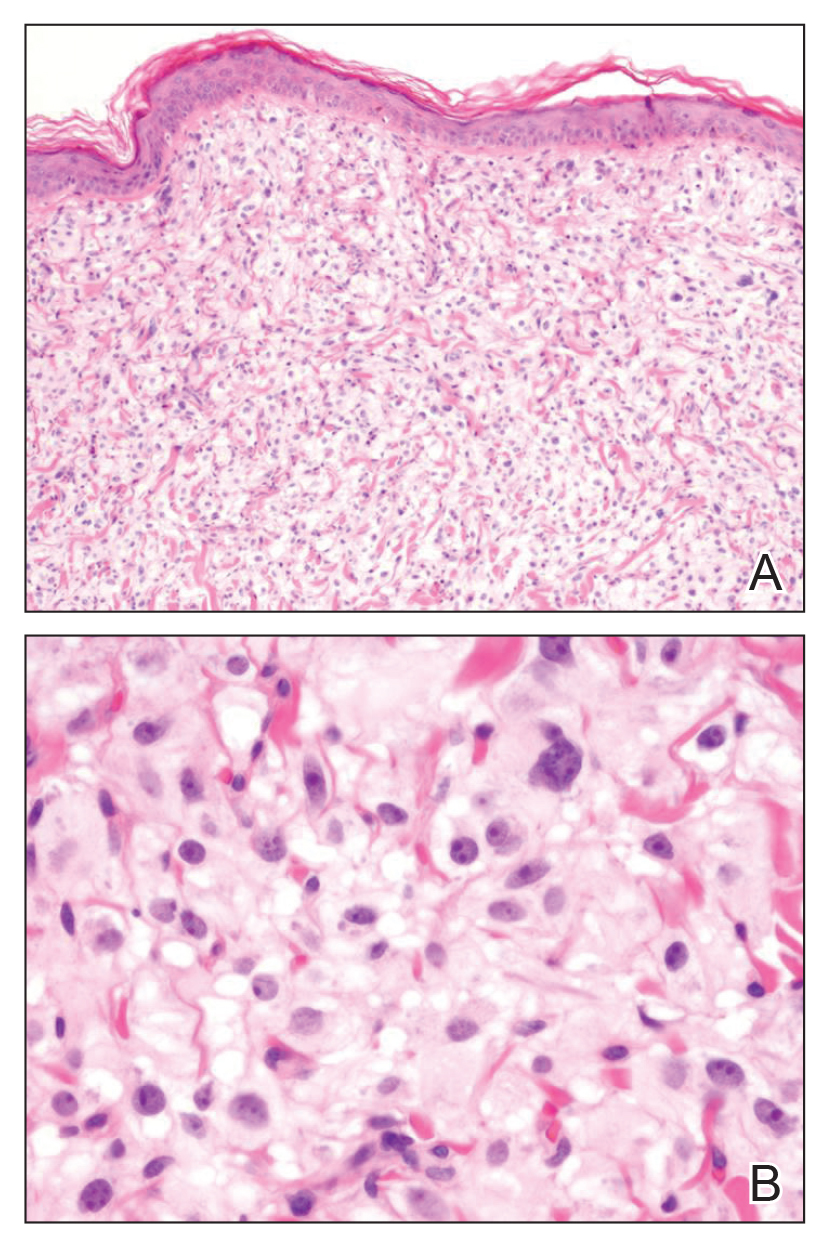

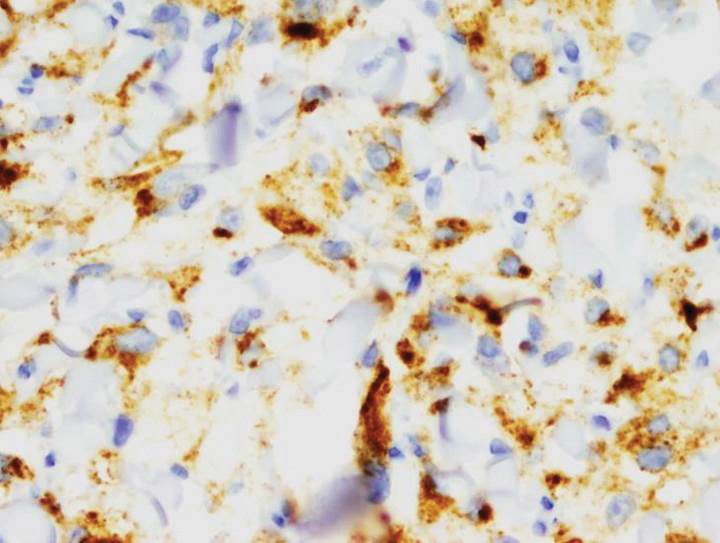

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

Case Report

A 62-year-old woman presented with multiple large friable tumors of the abdominal panniculus. The patient also reported an unintentional 75-lb weight loss over the last 9 months as well as vaginal bleeding and fecal discharge from the vagina of 2 weeks’ duration. The patient had a surgical and medical history of a robotic-assisted hysterectomy and bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy performed 4 years prior to presentation. Final surgical pathology showed complex atypical endometrial hyperplasia with no adenocarcinoma identified.

Physical examination revealed multiple large, friable, exophytic tumors of the left side of the lower abdominal panniculus within close vicinity of the patient’s abdominal hysterectomy scars (Figure 1). The largest lesion measured approximately 6 cm in length. Laboratory values were elevated for carcinoembryonic antigen (5.9 ng/mL [reference range, <3.0 ng/mL]) and cancer antigen 125 (202 U/mL [reference range, <35 U/mL]). Computed tomography of the abdomen and pelvis revealed diffuse metastatic disease.

Comment

Incidence and Pathogenesis

Endometrial carcinoma is the most common gynecologic malignancy in the United States, but it rarely progresses to disseminated disease because of routine gynecologic examinations and the low threshold for surgical intervention. Cutaneous metastases represent one of the rarest presentations of disseminated disease, occurring in only 0.8% of those diagnosed with endometrial carcinoma.1 Cutaneous metastases occur almost exclusively in women older than 50 years and typically appear several months to years after hysterectomy. Although the exact pathogenesis is unknown, it is theorized that small foci of malignant cells may be seeded during surgery, leading to visceral and cutaneous involvement.

Clinical Presentation

Lesions vary morphologically, most commonly presenting as nonspecific, painless, hemorrhagic nodules. Lesions typically present in areas of direct local extension; prior radiotherapy; or areas of initial surgery, as was the case with our patient.2 Approximately 20 cases of umbilical involvement (Sister Mary Joseph nodule) have been reported in the literature. These cases are thought to occur from direct local spread of disease from the peritoneum.3 Hematogenous and lymphatic spread to distant sites such as the scalp and mandible also have been reported. More than 50% of patients will have underlying visceral metastatic disease at the time of diagnosis.3

Histopathologic Findings

Histopathology varies with the morphology of the underlying primary tumor, with endometrioid adenocarcinoma being the most common form associated with cutaneous metastasis, as was the case with our patient.4 Histology is characterized by dermal proliferation of atypical glandular epithelium with diffuse hemorrhage. Staining typically is positive for CK7 and negative for CK20 and CDX2.5 Histopathology and immunohistochemical staining are not specific for diagnosis and must be correlated with clinical history.

Management and Prognosis

Similar to cutaneous metastasis in other internal malignancies, prognosis is poor, as widespread dissemination of the underlying malignancy typically is present. Mean life expectancy is 4 to 12 months.6 Treatment is primarily palliative, as chemotherapy and radiotherapy are largely ineffective.

Conclusion

Our patient represents a dramatic form of cutaneous extension of a common disease. Dermatologists often are consulted because of the nonspecific nature of the lesions and must be conscious of this entity. As with other cutaneous metastases, a thorough medical and surgical history in conjunction with histopathology are necessary for an accurate diagnosis.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

- Atallah D, el Kassis N, Lutfallah F, et al. Cutaneous metastasis in endometrial cancer: once in a blue moon—case report. World J Surg Oncol. 2014;12:86.

- Temkin SM, Hellman M, Lee YC, et al. Surgical resection of vulvar metastases of endometrial cancer: a presentation of two cases. J Low Genit Tract Dis. 2007;11:118-121.

- Kushner DM, Lurain JR, Fu TS, et al. Endometrial adenocarcinoma metastatic to the scalp: case report and literature review. Gynecol Oncol. 1997;65:530-533.

- El M’rabet FZ, Hottinger A, George AC. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma: a case report and literature review. J Clin Gynecol Obstet. 2012;1:19-23.

- Stonard CM, Manek S. Cutaneous metastasis from an endometrial carcinoma: a case history and review of the literature. Histopathology. 2003;43:201-203

- Damewood MD, Rosenshein NB, Grumbine FC, et al. Cutaneous metastasis of endometrial carcinoma. Cancer. 1980;46:1471-1477.

Practice Points

- Cutaneous metastases of endometrial carcinoma are extremely rare and typically present in areas of direct local spread.

- As with other cutaneous metastases, lesions often are nonspecific, making history and histopathology essential for diagnosis.

Analysis of Nail-Related Content in the Basic Dermatology Curriculum

Patients frequently present to dermatologists with nail disorders as their chief concern. Alternatively, nail conditions may be encountered by the examining physician as an incidental finding that may be a clue to underlying systemic disease. Competence in the diagnosis and treatment of nail diseases can drastically improve patient quality of life and can be lifesaving,1 but many dermatologists find management of nail diseases challenging.2 Bridging this educational gap begins with dermatology resident and medical student education. In a collaboration with dermatology educators, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) prepared a free online core curriculum for medical students that covers the essential concepts of dermatology. We sought to determine the integration of nail education in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum was conducted to determine nail disease content. The curriculum modules were downloaded in June 2018,

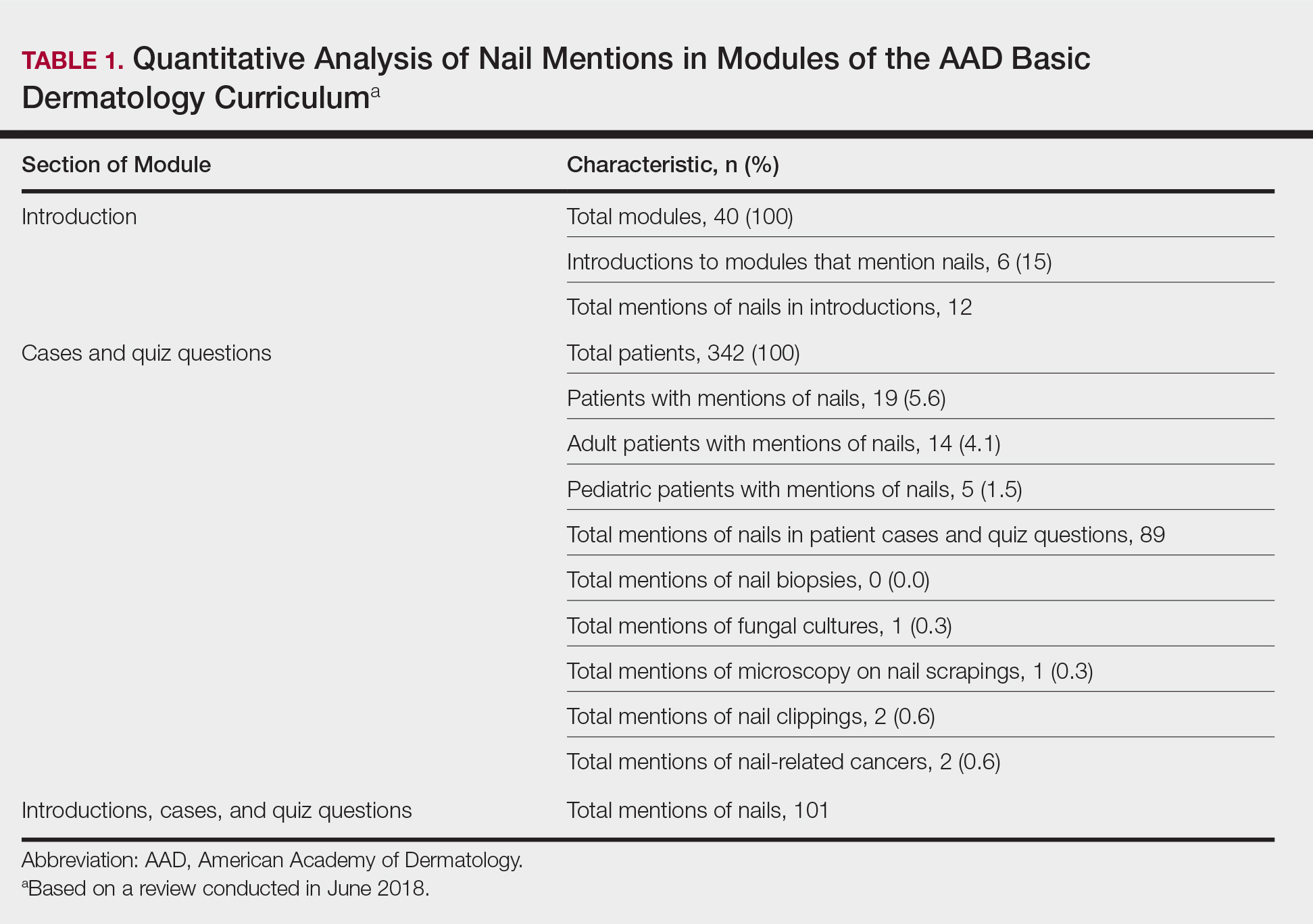

Results

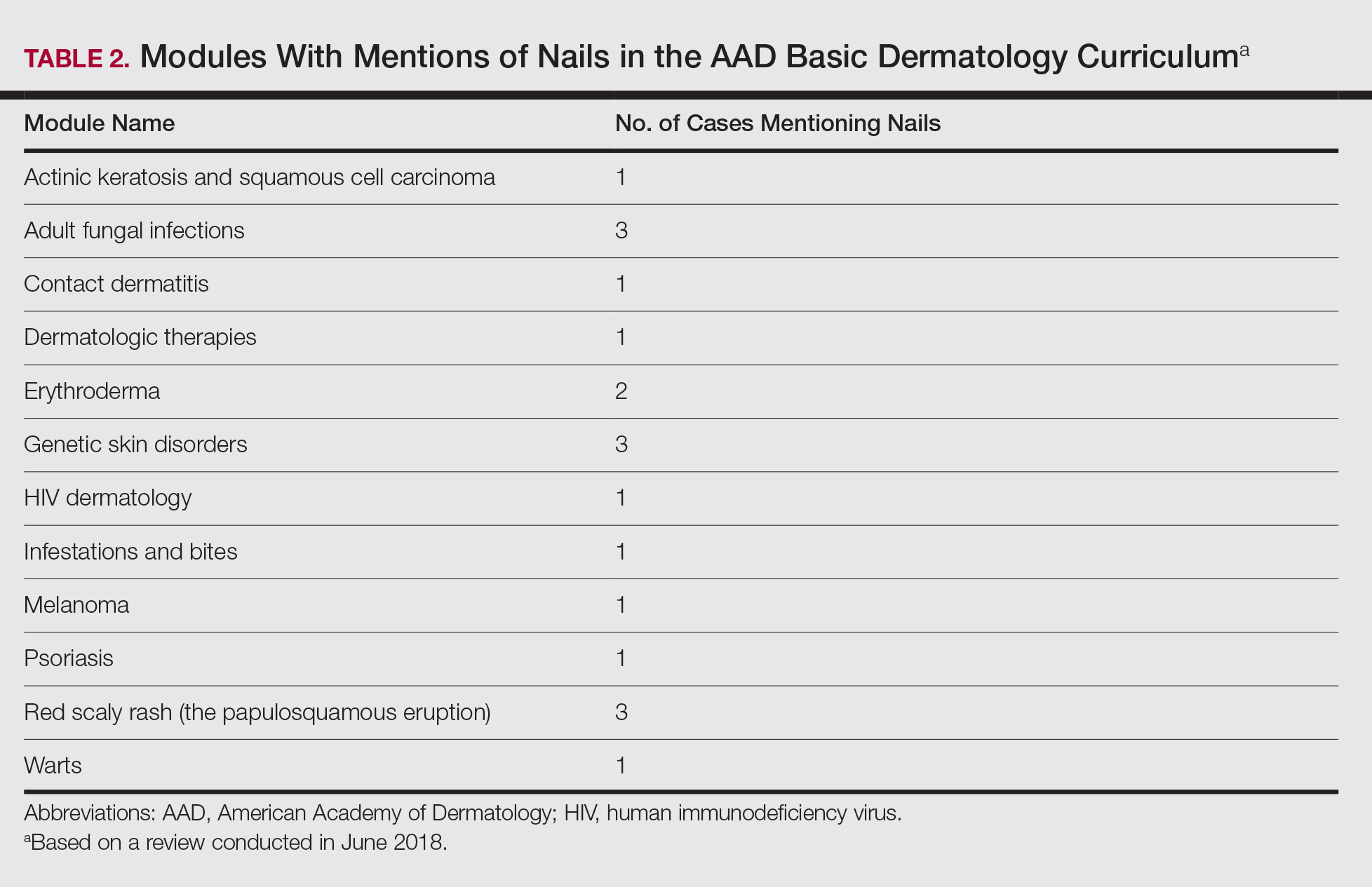

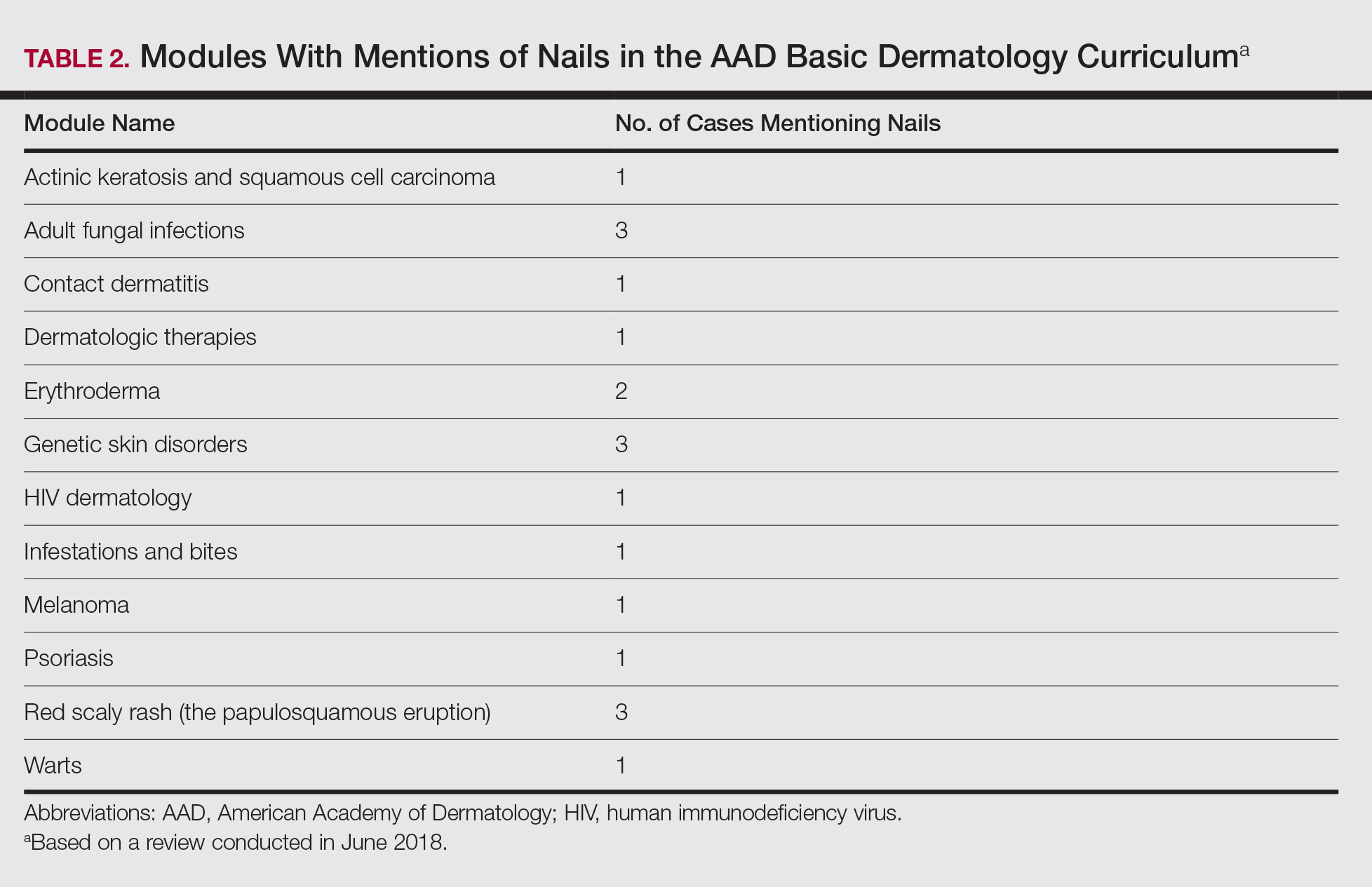

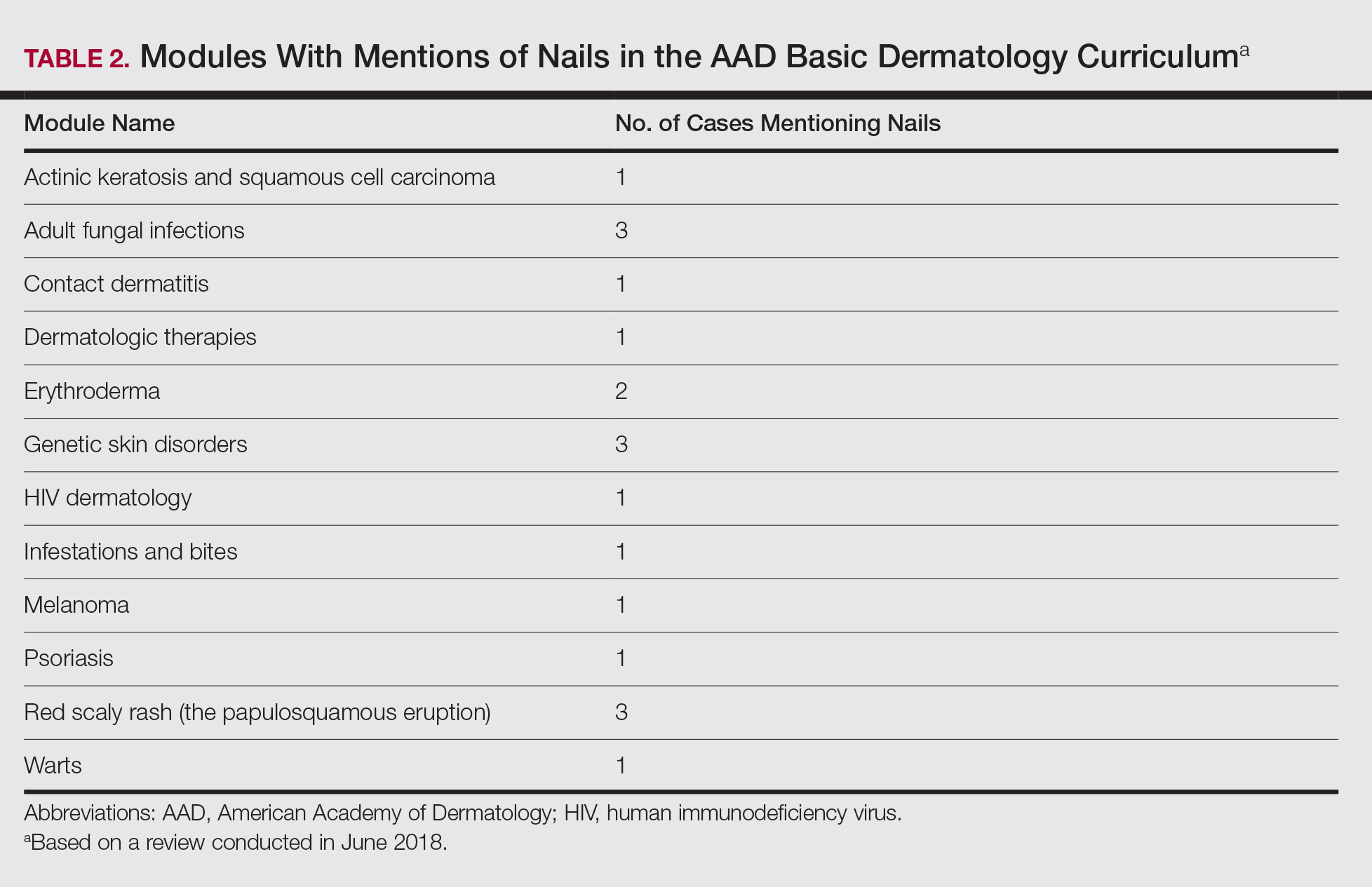

Of 342 patients discussed in cases and quizzes, nails were mentioned for 19 patients (89 times total)(Table 1). Additionally, there were 2 mentions each of nail clippings and nail tumors, 0 mentions of nail biopsies, and 1 mention each of fungal cultures and microscopy on nail scrapings (Table 1). Of the 40 modules, nails were mentioned in 12 modules (Table 2) and 6 introductions to the modules (Table 1). There were no mentions of the terms nails, subungual, or onychomycosis in the learning objectives.3

Comment

Our study demonstrates a paucity of content relevant to nails in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum. Medical students are missing an important opportunity to learn about diagnosis and management of nail conditions and may incorrectly conclude that nail expertise is not essential to becoming a competent board-certified dermatologist.

Particularly concerning is the exclusion of nail examinations in the skin exam module addressing full-body skin examinations (0 mentions in 31 slides). This curriculum may negatively influence medical students and may then follow at the resident level, with a study reporting that 50.3% (69/137) of residents examine nails only when the patient brings it to their attention.4

Most concerning was the inadequate coverage of nail unit melanoma in the melanoma module (1 mention in 53 slides). Furthermore, the ABCDE—asymmetry, border, color, diameter, and evolving—mnemonic for cutaneous melanoma was covered in 6 slides in this module, and the ABCDEF—family history added—mnemonic for nail unit melanoma was completely excluded. Not surprisingly, resident knowledge of melanonychia diagnosis is deficient, with a prior study demonstrating that 62% (88/142) of residents were not confident diagnosing and managing patients with melanonychia, and only 88% (125/142) of residents were aware of the nail melanoma mnemonic.4

Similarly, nail biopsy for melanonychia diagnosis was excluded from the curriculum, whereas skin biopsy was thoroughly discussed in the context of a cutaneous melanoma diagnosis. This deficient teaching may track to the dermatology resident curriculum, as a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, and one-third of residents felt incompetent in nail surgery.5

We acknowledge that the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum is simply an introduction to dermatology. However, given that dermatologists are among the major specialists who care for nail patients, we advocate for more content on nail diseases in this curriculum. Nails can easily be incorporated into existing modules, and a new module specifically dedicated to nail disease should be added. Moreover, we envision that our findings will positively reflect on competence in treating nail disease for dermatology residents.

- Lipner SR. Ulcerated nodule of the fingernail. JAMA. 2018;319:713-714.

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Basic Dermatology Curriculum. https://www.aad.org/education/basic-derm-curriculum. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483, 483.e1-5.

Patients frequently present to dermatologists with nail disorders as their chief concern. Alternatively, nail conditions may be encountered by the examining physician as an incidental finding that may be a clue to underlying systemic disease. Competence in the diagnosis and treatment of nail diseases can drastically improve patient quality of life and can be lifesaving,1 but many dermatologists find management of nail diseases challenging.2 Bridging this educational gap begins with dermatology resident and medical student education. In a collaboration with dermatology educators, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) prepared a free online core curriculum for medical students that covers the essential concepts of dermatology. We sought to determine the integration of nail education in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum was conducted to determine nail disease content. The curriculum modules were downloaded in June 2018,

Results

Of 342 patients discussed in cases and quizzes, nails were mentioned for 19 patients (89 times total)(Table 1). Additionally, there were 2 mentions each of nail clippings and nail tumors, 0 mentions of nail biopsies, and 1 mention each of fungal cultures and microscopy on nail scrapings (Table 1). Of the 40 modules, nails were mentioned in 12 modules (Table 2) and 6 introductions to the modules (Table 1). There were no mentions of the terms nails, subungual, or onychomycosis in the learning objectives.3

Comment

Our study demonstrates a paucity of content relevant to nails in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum. Medical students are missing an important opportunity to learn about diagnosis and management of nail conditions and may incorrectly conclude that nail expertise is not essential to becoming a competent board-certified dermatologist.

Particularly concerning is the exclusion of nail examinations in the skin exam module addressing full-body skin examinations (0 mentions in 31 slides). This curriculum may negatively influence medical students and may then follow at the resident level, with a study reporting that 50.3% (69/137) of residents examine nails only when the patient brings it to their attention.4

Most concerning was the inadequate coverage of nail unit melanoma in the melanoma module (1 mention in 53 slides). Furthermore, the ABCDE—asymmetry, border, color, diameter, and evolving—mnemonic for cutaneous melanoma was covered in 6 slides in this module, and the ABCDEF—family history added—mnemonic for nail unit melanoma was completely excluded. Not surprisingly, resident knowledge of melanonychia diagnosis is deficient, with a prior study demonstrating that 62% (88/142) of residents were not confident diagnosing and managing patients with melanonychia, and only 88% (125/142) of residents were aware of the nail melanoma mnemonic.4

Similarly, nail biopsy for melanonychia diagnosis was excluded from the curriculum, whereas skin biopsy was thoroughly discussed in the context of a cutaneous melanoma diagnosis. This deficient teaching may track to the dermatology resident curriculum, as a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, and one-third of residents felt incompetent in nail surgery.5

We acknowledge that the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum is simply an introduction to dermatology. However, given that dermatologists are among the major specialists who care for nail patients, we advocate for more content on nail diseases in this curriculum. Nails can easily be incorporated into existing modules, and a new module specifically dedicated to nail disease should be added. Moreover, we envision that our findings will positively reflect on competence in treating nail disease for dermatology residents.

Patients frequently present to dermatologists with nail disorders as their chief concern. Alternatively, nail conditions may be encountered by the examining physician as an incidental finding that may be a clue to underlying systemic disease. Competence in the diagnosis and treatment of nail diseases can drastically improve patient quality of life and can be lifesaving,1 but many dermatologists find management of nail diseases challenging.2 Bridging this educational gap begins with dermatology resident and medical student education. In a collaboration with dermatology educators, the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) prepared a free online core curriculum for medical students that covers the essential concepts of dermatology. We sought to determine the integration of nail education in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum.

Methods

A cross-sectional study of the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum was conducted to determine nail disease content. The curriculum modules were downloaded in June 2018,

Results

Of 342 patients discussed in cases and quizzes, nails were mentioned for 19 patients (89 times total)(Table 1). Additionally, there were 2 mentions each of nail clippings and nail tumors, 0 mentions of nail biopsies, and 1 mention each of fungal cultures and microscopy on nail scrapings (Table 1). Of the 40 modules, nails were mentioned in 12 modules (Table 2) and 6 introductions to the modules (Table 1). There were no mentions of the terms nails, subungual, or onychomycosis in the learning objectives.3

Comment

Our study demonstrates a paucity of content relevant to nails in the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum. Medical students are missing an important opportunity to learn about diagnosis and management of nail conditions and may incorrectly conclude that nail expertise is not essential to becoming a competent board-certified dermatologist.

Particularly concerning is the exclusion of nail examinations in the skin exam module addressing full-body skin examinations (0 mentions in 31 slides). This curriculum may negatively influence medical students and may then follow at the resident level, with a study reporting that 50.3% (69/137) of residents examine nails only when the patient brings it to their attention.4

Most concerning was the inadequate coverage of nail unit melanoma in the melanoma module (1 mention in 53 slides). Furthermore, the ABCDE—asymmetry, border, color, diameter, and evolving—mnemonic for cutaneous melanoma was covered in 6 slides in this module, and the ABCDEF—family history added—mnemonic for nail unit melanoma was completely excluded. Not surprisingly, resident knowledge of melanonychia diagnosis is deficient, with a prior study demonstrating that 62% (88/142) of residents were not confident diagnosing and managing patients with melanonychia, and only 88% (125/142) of residents were aware of the nail melanoma mnemonic.4

Similarly, nail biopsy for melanonychia diagnosis was excluded from the curriculum, whereas skin biopsy was thoroughly discussed in the context of a cutaneous melanoma diagnosis. This deficient teaching may track to the dermatology resident curriculum, as a survey of third-year dermatology residents (N=240) showed that 58% performed 10 or fewer nail procedures, and one-third of residents felt incompetent in nail surgery.5

We acknowledge that the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum is simply an introduction to dermatology. However, given that dermatologists are among the major specialists who care for nail patients, we advocate for more content on nail diseases in this curriculum. Nails can easily be incorporated into existing modules, and a new module specifically dedicated to nail disease should be added. Moreover, we envision that our findings will positively reflect on competence in treating nail disease for dermatology residents.

- Lipner SR. Ulcerated nodule of the fingernail. JAMA. 2018;319:713-714.

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Basic Dermatology Curriculum. https://www.aad.org/education/basic-derm-curriculum. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483, 483.e1-5.

- Lipner SR. Ulcerated nodule of the fingernail. JAMA. 2018;319:713-714.

- Hare AQ, Rich P. Clinical and educational gaps in diagnosis of nail disorders. Dermatol Clin. 2016;34:269-273.

- American Academy of Dermatology. Basic Dermatology Curriculum. https://www.aad.org/education/basic-derm-curriculum. Accessed March 25, 2019.

- Halteh P, Scher R, Artis A, et al. A survey-based study of management of longitudinal melanonychia amongst attending and resident dermatologists. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2017;76:994-996.

- Lee EH, Nehal KS, Dusza SW, et al. Procedural dermatology training during dermatology residency: a survey of third-year dermatology residents. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2011;64:475-483, 483.e1-5.

Practice Points

- Competence in the diagnosis and treatment of nail diseases can drastically improve patient quality of life and can be lifesaving.

- Education on diagnosis and management of nail conditions is deficient in the American Academy of Dermatology (AAD) Basic Dermatology Curriculum.

- Increased efforts are needed to incorporate relevant nail education materials into the AAD Basic Dermatology Curriculum.

Leukemia Cutis–Associated Leonine Facies and Eyebrow Loss

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

To the Editor:

I read with interest the informative Cutis case report by Krooks and Weatherall1 in which the authors not only described the case of a 66-year-old man whose diagnosis of bone marrow biopsy–confirmed acute myeloid leukemia (AML) presented concurrently with skin biopsy–confirmed leukemia cutis but also discussed the poor prognosis of individuals with acute myelogenous leukemia cutis. Their patient died within 5 weeks of establishing the diagnosis. In addition, lateral and frontal photographs of the patient’s face demonstrated diffuse infiltrative plaques of leukemia cutis; he had swollen eyelids and lips with distortion of the nose secondary to dermal infiltration of leukemic myeloid cells.1 Although not emphasized by the authors, the patient appeared to have a leonine facies and at least partial loss of the lateral eyebrows.

Malignancy-associated leonine facies resulting from infiltration of the skin by neoplastic cells has been reported in a patient with metastatic breast carcinoma.2,3 However, it predominantly occurs in patients with hematologic dyscrasias such as leukemia cutis, lymphoma (ie, cutaneous B cell, cutaneous T cell, Hodgkin), plasmacytoma, and systemic mastocytosis.3,4 The report by Krooks and Weatherall1 adds AML-associated leukemia cutis to the previously observed types of leukemia cutis–related leonine facies in patients with acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and chronic lymphocytic leukemia.3,4

Partial or complete loss of eyebrows in the setting of leonine facies has a limited differential diagnosis.3,5 In addition to cancer, the associated disorders include adnexal mucin deposition (alopecia mucinosis), granulomatous conditions (sarcoidosis), infectious diseases (leprosy), inherited syndromes (Setleis syndrome), photoallergic dermatoses (actinic reticuloid), and viral conditions (viral-associated trichodysplasia).3-9 Neoplasms associated with leonine facies and eyebrow loss include lymphomas (mycosis fungoides and unspecified cutaneous T-cell lymphoma), systemic mastocytosis and leukemia cutis secondary to acute lymphocytic leukemia, acute myelomonocytic leukemia, and now AML.1,3-5

The eyebrow loss associated with leonine facies often is not reversible once the causative cell of the associated condition (eg, granulomas of mycobacteria-infected histiocytes in leprosy, neoplastic lymphocytes in cutaneous T-cell lymphoma) has infiltrated the area of the eyebrows and abolished the preexisting hair follicles; however, follow-up descriptions of patients after treatment of other conditions that cause eyebrow loss usually are not reported. Indeed, there was partial reappearance of the eyebrows in a woman with systemic mastocytosis–associated loss of the eyebrows after malignancy-related treatment was reinitiated and the infiltrative facial plaques that had created her leonine facies had decreased in size.5 It is reasonable to speculate that the eyebrows may have reappeared in the patient reported by Krooks and Weatherall1 and his leonine facies–associated facial plaques may have resolved if he had underwent and responded to treatment with antineoplastic chemotherapy.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

- Krooks JA, Weatherall AG. Leukemia cutis in acute myeloid leukemia signifies a poor prognosis. Cutis. 2018;102:266, 271-272.

- Jin CC, Martinelli PT, Cohen PR. What are these erythematous skin lesions? leukemia cutis. The Dermatologist. 2012;20:46-50.

- Chodkiewicz HM, Cohen PR. Systemic mastocytosis-associated leonine facies and eyebrow loss. South Med J. 2011;104:236-238.

- Cohen PR, Rapini RP, Beran M. Infiltrated blue-gray plaques in a patient with leukemia. Chloroma (granulocytic sarcoma). Arch Dermatol. 1987;123:251, 254.

- Cohen PR. Leonine facies associated with eyebrow loss. Int J Dermatol. 2014;53:e148-e149.

- Ravic-Nikolic A, Milicic V, Ristic G, et al. Actinic reticuloid presented as facies leonine. Int J Dermatol. 2012;51:234-236.

- Jacob Raja SA, Raja JJ, Vijayashree R, et al. Evaluation of oral and periodontal status of leprosy patients in Dindigul district. J Pharm Bioallied Sci. 2016;8(suppl 1):S119-S121.

- McGaughran J, Aftimos S. Setleis syndrome: three new cases and a review of the literature. Am J Med Genet. 2002;111:376-380.

- Benoit T, Bacelieri R, Morrell DS, et al. Viral-associated trichodysplasia of immunosuppression: report of a pediatric patient with response to oral valganciclovir. Arch Dermatol. 2010;146:871-874.

Clinical Pearl: Kinesiology Tape for Onychocryptosis

Practice Gap

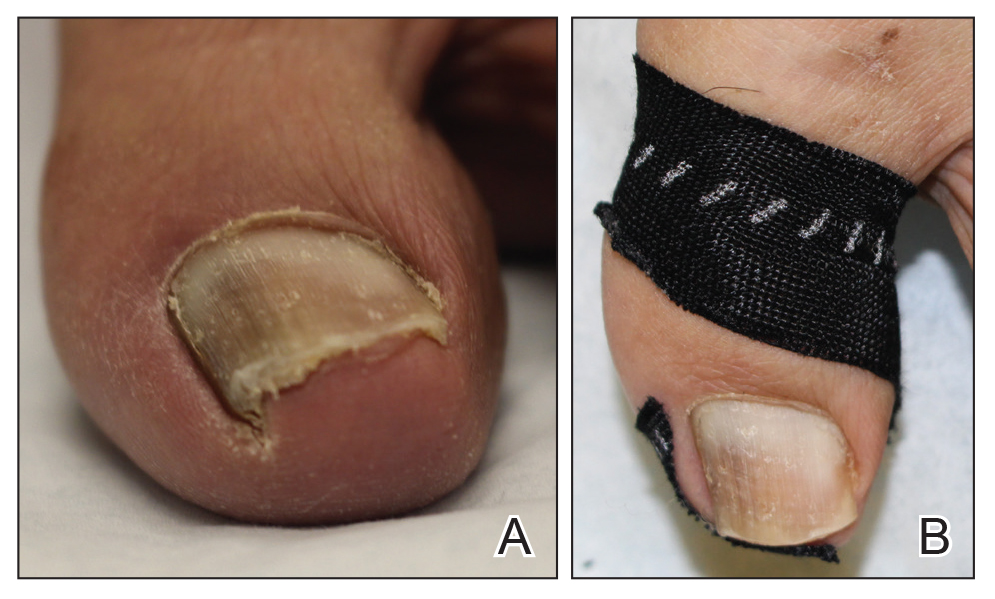

Onychocryptosis, or ingrown toenail, is a highly prevalent nail condition characterized by penetration of the periungual skin by the nail plate (Figure, A). Patients may report pain either while at rest or walking, which may be debilitating in severe cases and may adversely affect daily living. Treatment may be approached using conservative or surgical therapies. Conservative methods are noninvasive and appropriate for mild cases but require excellent compliance. Although nail trimming is the simplest method, it may necessitate cutting soft tissue, particularly when the nail is anchored deep within the periungual skin. Another conservative method is taping, which aims to separate the nail fold from the offending nail edge by using an adhesive. In common practice, the adhesive often detaches within a few hours, which is further exacerbated by moisture from sweating or bathing.1 Therefore, for effective treatment of onychocryptosis, the tape typically must be reapplied multiple times per day, limiting compliance.

Tools

We propose using kinesiology tape to treat onychocryptosis. Kinesiology tape is a highly elastic adhesive that was originally employed by athletes to relieve pain while supporting muscles, tendons, and ligaments during strenuous activity. We hypothesized that its stronger adherent properties and greater elasticity would be advantageous for treatment of onychocryptosis compared to standard tape.

The Technique

A strip of tape is cut to approximately 10 to 15 mm×5 cm and is applied once daily to the lateral nail fold, pulling it away from the nail plate in oblique and proximal directions and then wrapping it around the plantar surface dorsally (Figure, B). Kinesiology tape properties allow for less frequent application and greater tension to be applied to the nail fold while reducing the risk for

Practice Implications

Kinesiology tape adheres more firmly than other tapes and requires less frequent applications. Use of kinesiology tape for onychocryptosis therapy often is effective and may negate the need for more invasive procedures and improve quality of life during and after treatment.

1. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails [published online May 20, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924.

Practice Gap

Onychocryptosis, or ingrown toenail, is a highly prevalent nail condition characterized by penetration of the periungual skin by the nail plate (Figure, A). Patients may report pain either while at rest or walking, which may be debilitating in severe cases and may adversely affect daily living. Treatment may be approached using conservative or surgical therapies. Conservative methods are noninvasive and appropriate for mild cases but require excellent compliance. Although nail trimming is the simplest method, it may necessitate cutting soft tissue, particularly when the nail is anchored deep within the periungual skin. Another conservative method is taping, which aims to separate the nail fold from the offending nail edge by using an adhesive. In common practice, the adhesive often detaches within a few hours, which is further exacerbated by moisture from sweating or bathing.1 Therefore, for effective treatment of onychocryptosis, the tape typically must be reapplied multiple times per day, limiting compliance.

Tools

We propose using kinesiology tape to treat onychocryptosis. Kinesiology tape is a highly elastic adhesive that was originally employed by athletes to relieve pain while supporting muscles, tendons, and ligaments during strenuous activity. We hypothesized that its stronger adherent properties and greater elasticity would be advantageous for treatment of onychocryptosis compared to standard tape.

The Technique

A strip of tape is cut to approximately 10 to 15 mm×5 cm and is applied once daily to the lateral nail fold, pulling it away from the nail plate in oblique and proximal directions and then wrapping it around the plantar surface dorsally (Figure, B). Kinesiology tape properties allow for less frequent application and greater tension to be applied to the nail fold while reducing the risk for

Practice Implications

Kinesiology tape adheres more firmly than other tapes and requires less frequent applications. Use of kinesiology tape for onychocryptosis therapy often is effective and may negate the need for more invasive procedures and improve quality of life during and after treatment.

Practice Gap

Onychocryptosis, or ingrown toenail, is a highly prevalent nail condition characterized by penetration of the periungual skin by the nail plate (Figure, A). Patients may report pain either while at rest or walking, which may be debilitating in severe cases and may adversely affect daily living. Treatment may be approached using conservative or surgical therapies. Conservative methods are noninvasive and appropriate for mild cases but require excellent compliance. Although nail trimming is the simplest method, it may necessitate cutting soft tissue, particularly when the nail is anchored deep within the periungual skin. Another conservative method is taping, which aims to separate the nail fold from the offending nail edge by using an adhesive. In common practice, the adhesive often detaches within a few hours, which is further exacerbated by moisture from sweating or bathing.1 Therefore, for effective treatment of onychocryptosis, the tape typically must be reapplied multiple times per day, limiting compliance.

Tools

We propose using kinesiology tape to treat onychocryptosis. Kinesiology tape is a highly elastic adhesive that was originally employed by athletes to relieve pain while supporting muscles, tendons, and ligaments during strenuous activity. We hypothesized that its stronger adherent properties and greater elasticity would be advantageous for treatment of onychocryptosis compared to standard tape.

The Technique

A strip of tape is cut to approximately 10 to 15 mm×5 cm and is applied once daily to the lateral nail fold, pulling it away from the nail plate in oblique and proximal directions and then wrapping it around the plantar surface dorsally (Figure, B). Kinesiology tape properties allow for less frequent application and greater tension to be applied to the nail fold while reducing the risk for

Practice Implications

Kinesiology tape adheres more firmly than other tapes and requires less frequent applications. Use of kinesiology tape for onychocryptosis therapy often is effective and may negate the need for more invasive procedures and improve quality of life during and after treatment.

1. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails [published online May 20, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924.

1. Haneke E. Controversies in the treatment of ingrown nails [published online May 20, 2012]. Dermatol Res Pract. 2012;2012:783924.

What’s Eating You? Millipede Burns

Clinical Presentation

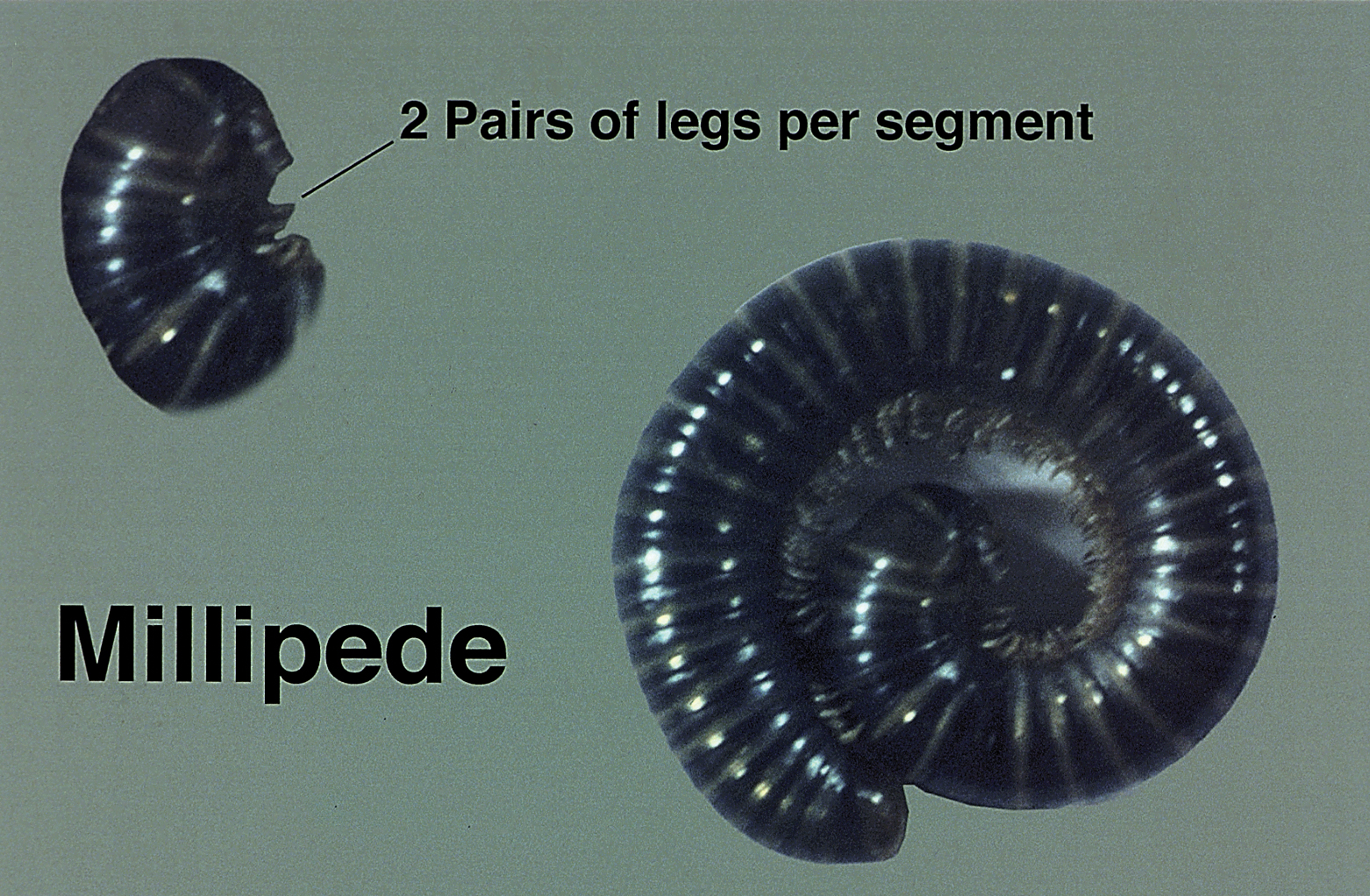

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

Clinical Presentation

Millipedes secrete a noxious toxin implicated in millipede burns. The toxic substance is benzoquinone, a strong irritant secreted from the repugnatorial glands contained in each segment of the arthropod (Figure 1). This compound serves as a natural insect repellant, acting as the millipede’s defense mechanism from potential predators.1 On human skin, benzoquinone causes localized pigmentary changes most commonly presenting on the feet and toes. Local lesions may be associated with pain or burning, but there are no known reports of adverse systemic effects.2 Affected patients experience cutaneous pigmentary changes, which may be dark red, blue, or black, and spontaneously resolve over time.2 The degree of pigment change may be associated with duration of skin contact with the toxin. The affected areas may resemble burns, dermatitis, or skin necrosis. More distal lesions may present similarly to blue toe syndrome or acute arterial occlusion but can be differentiated by the presence of intact peripheral pulses and lack of temperature discrepancy between the feet.3,4 Histologic evaluation of the lesions generally reveals nonspecific full-thickness epidermal necrosis, making clinical suspicion and physical examination paramount to the diagnosis of millipede burns.5

Diagnostic Difficulties

Accurate diagnosis of millipede burns is more difficult when the burn involves an unusual site. The most common site of involvement is the foot (Figure 2), followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes.2,3,6,7 Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected, requiring the arthropod to gain access via infiltration of clothing, often when hanging on a clothesline. In these cases, burns may be mistaken for child abuse, especially if certain areas of the body are involved, such as the groin and genitals.2 The well-defined arcuate lesions of the burns may resemble injuries from a wire or belt to the unsuspecting observer.

Conclusion

Although millipedes often are regarded as harmless, they are capable of causing adverse reactions through the secretion of toxic chemicals. Millipede burns cause localized pigmentary changes that may be associated with pain or burning in some patients. Because these burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

- Kuwahara Y, Omura H, Tanabe T. 2-Nitroethenylbenzenes as naturalproducts in millipede defense secretions. Naturwissenschaften. 2002;89:308-310.

- De Capitani EM, Vieira RJ, Bucaretchi F, et al. Human accidents involving Rhinocricus spp., a common millipede genus observed in urban areas of Brazil. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2011;49:187-190.

- Heeren Neto AS, Bernardes Filho F, Martins G. Skin lesions simulating blue toe syndrome caused by prolonged contact with a millipede. Rev Soc Bras Med Trop. 2014;47:257-258.

- Lima CA, Cardoso JL, Magela A, et al. Exogenous pigmentation in toes feigning ischemia of the extremities: a diagnostic challenge brought by arthropods of the Diplopoda class (“millipedes”). An Bras Dermatol. 2010;85:391-392.

- Dar NR, Raza N, Rehman SB. Millipede burn at an unusual site mimicking child abuse in an 8-year-old girl. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2008;47:490-492.

- Hendrickson RG. Millipede exposure. Clin Toxicol (Phila). 2005;43:211-212.

- Verma AK, Bourke B. Millipede burn masquerading as trash foot in a paediatric patient [published online October 29, 2013]. ANZ J Surg. 2014;84:388-390.

Practice Points

- The most common site of involvement of millipede burns is the foot, followed by other commonly exposed areas such as the arms, face, and eyes. Covered parts of the body are much less commonly affected.

- Millipede burns may resemble child abuse in pediatric patients; therefore, physicians should be aware of this diagnosis when unusual parts of the body are involved.

Parabens: The 2019 Nonallergen of the Year

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) names an allergen of the year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the allergen of the year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). In 2019, the ACDS chose parabens as the “nonallergen” of the year to draw attention to their low rate of associated ACD despite high public interest in limiting exposure to parabens.1

What types of products contain parabens?

Parabens are preservatives commonly found in many different categories of personal care products. Preservatives inhibit microbial growth and are necessary ingredients in water-based products. The 4 most common parabens used in personal care products are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.1 Parabens are metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and are excreted in urine. When parabens are applied topically, there is minimal penetration through intact human skin.2 In the United States, parabens are allowed as preservatives in cosmetics at concentrations up to 0.4% when used alone or up to 0.8% when used in combination with other parabens.3

Consumers are exposed to parabens in a wide variety of personal care products. The Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) is a system owned and managed by the ACDS that typically is used to generate lists of safe personal care products for patients and also can be queried for the presence of individual chemicals in products. According to a 2018 query of the CAMP, parabens were found in 19% of all products.1 A more recent query of CAMP (http://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) in March 2019 showed parabens were present in 39.3% of makeup products, especially in eye products, foundations, and concealers; parabens also were found in 34% of moisturizers, 11.5% of soaps, and 19% of sunscreens. Notably, 14.8% of prescription topical steroids listed in the CAMP contained a paraben. Another method for evaluating chemical contents of personal care products is a review of the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program, a US Food and Drug Administration–based registry for cosmetic products. Survey data from the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program in 2018 documented methylparaben in 11,626 formulations.4 Other parabens included propylparaben (8885 products), butylparaben (3915 products), and ethylparaben (3860 products). Parabens were reported more frequently in leave-on rather than rinse-off products.4

In medications, parabens are recommended at concentrations of no more than 0.1%.1 Fransway et al1 compiled a list of medications that contain parabens, including commonly prescribed dermatologic topical medications such as corticosteroids, several acne preparations, eflornithine, fluorouracil, hydroquinone, imiquimod, urea, and sertaconazole. Oral and parenteral medications including local anesthetics and corticosteroids also may contain parabens.

Consumers also may be exposed to parabens through foodstuffs. Methylparaben and propylparaben have been classified as generally recognized as safe in foods by the US Food and Drug Administration.5 The acceptable daily intake of parabens in food is 0 to 10 mg/kg of body weight,1 and the estimated dietary intake for a typical adult is 307 mg/kg of body weight daily.6 Several studies on paraben content in foodstuffs have confirmed their presence in both natural and processed foods.1,6 Systemic contact dermatitis caused by ingestion of parabens is rare. In general, individuals with positive patch test reactions to parabens should not routinely avoid them in foods or oral medications,1 but they should, of course, be avoided in topical medications.

What is the rate of ACD with parabens?

One of the main reasons that parabens were designated as the ACDS nonallergen of the year is the very low rate of ACD associated with parabens. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group, a research group with members in the United States and Canada, reported a 0.6% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 12%,7 which closely compares with a 0.8% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 16% using the Mayo Clinic standard series.8 From the standpoint of ACD, this very low patch test reaction rate makes parabens one of the safest preservative options for use in cosmetic products.

Are there health risks associated with parabens?

The paraben controversy in the scientific literature and in the lay press centers around potential health risks and endocrine disruption. We will focus on the conversation regarding parabens and the risk for endocrine disruption and association with breast cancer.

Parabens have been reported to have estrogenic effects; however, the bulk of the data is limited to in vitro and animal studies, with less evidence of endocrine disruption in humans.2 In vitro studies have demonstrated that the estrogenic potency of parabens is much less than that of estrogen. In one study, parabens were shown to be 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol9; in a separate study, they had a maximum potency of only 1/4000 that of estrogen.10 Additionally, an in vitro study showed varying ability for parabens to bind estrogen receptors, with a greater ability to bind with longer alkyl side chains.11 The result is decreased or increased estrogen activity, dependent on side chain length and type of receptor.2 Finally, some studies add conflicting results that parabens may actually create an antiestrogenic effect in human breast cancer cells.12 From the standpoint of estrogen mimicry, there are no known studies in humans confirming harmful effects associated with paraben exposure.

The reported association between parabens and breast cancer is closely related to their theoretical estrogenic effects. The conversation regarding parabens and breast cancer has been fueled by the identification of parabens in human breast tumors and their presence in concentrations similar to what is needed to stimulate in vitro breast cancer cells.2 The existing data do not confirm causation. An association with parabens in topical axillary personal care products has been theorized but not confirmed; for example, it was shown that paraben levels were highest in the axillary region of breast cancer tissue, including women who had never used deodorant. It was concluded that the presence of axillary parabens was due to sources other than topical axillary personal care products.13 Another study confirmed there was not an increased risk for breast cancer in patients who applied personal care products to the axillary area within an hour of shaving.14 The existing data do not support topical paraben exposure as a risk for breast cancer.

Final Thoughts

Parabens are preservatives frequently found in personal care products and exhibit a very low rate of associated ACD. Consumers may be exposed to parabens through foods, cosmetics, and medications. Although there have been consumer concerns regarding endocrine disruption or carcinogenicity associated with parabens, definite evidence of their harm is lacking in the scientific literature, and many studies confirm their safety.2 With their high prevalence in personal care products and low rates of associated contact allergy, parabens remain ideal preservative agents.

Ultimately, contact dermatitis is a common yet often underrecognized dermatologic condition. To address this knowledge gap in clinical practice, we are proud to launch Final Interpretation, a new column in Cutis covering emerging trends in contact dermatitis. We will address pearls, pitfalls, and updates in contact dermatitis. Although our primary focus will be ACD, other important causes of contact dermatitis will be highlighted. Look for the inaugural column in the June 2019 issue of Cutis.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Parabens: contact (non)allergen of the year. Dermatitis. 2019;30:3-31.

- Fransway AF, Fransway PJ, Belsito DV, et al. Paraben toxicology. Dermatitis. 2019;30:32-45.

- Final amended report on the safety assessment of methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, isopropylparaben, butylparaben, isobutylparaben, and benzylparaben as used in cosmetic products. Int J Toxicol. 2008;27(suppl 4):1-82.

- Cosmetic Ingredient Review. Amended safety assessment of parabens as used in cosmetics. https://www.cir-safety.org/sites/default/files/Parabens.pdf. Published August 29, 2018. Accessed March 12, 2019.

- Methylparaben. Fed Regist. 2018;21(3):1490. To be codified at 21 CFR §184.

- Liao C, Liu F, Kannan K. Occurrence of and dietary exposure to parabens in foodstuffs from the United States. Environ Sci Technol. 2013;47:3918-3925.

- DeKoven JG, Warshaw EM, Zug KA, et al. North American Contact Dermatitis Group Patch Test Results: 2015-2016. Dermatitis. 2018;29:297-309.

- Veverka KK, Hall MR, Yiannias JA, et al. Trends in patch testing with the Mayo Clinic standard series, 2011-2015. Dermatitis. 2018;29:310-315.

- Routledge EJ, Parker J, Odum J, et al. Some alkyl hydroxy benzoate preservatives (parabens) are estrogenic. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 1998;153:12-19.

- Miller D, Brian B, Wheals BB, et al. Estrogenic activity of phenolic additives determined by an in vitro yeast bioassay. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109:133-138.

- Blair RM, Fang H, Branham WS. The estrogen receptor relative binding affinities of 188 natural and xenochemicals: structural diversity of ligands. Toxicol Sci. 2000;54:138-153.

- van Meeuwen JA, van Son O, Piersma AH, et al. Aromatase inhibiting and combined estrogenic effects of parabens and estrogenic effects of other additives in cosmetics. Toxicol Appl Pharmacol. 2008;230:372-382.

- Barr L, Metaxas G, Harbach CA, et al. Measurement of paraben concentrations in human breast tissue at serial locations across the breast from axilla to sternum. J Appl Toxicol. 2012;32:219-232.

- Mirick DK, Davis S, Thomas DB. Antiperspirant use and the risk of breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:1578-1580

.

Each year, the American Contact Dermatitis Society (ACDS) names an allergen of the year with the purpose of promoting greater awareness of a key allergen and its impact on patients. Often, the allergen of the year is an emerging allergen that may represent an underrecognized or novel cause of allergic contact dermatitis (ACD). In 2019, the ACDS chose parabens as the “nonallergen” of the year to draw attention to their low rate of associated ACD despite high public interest in limiting exposure to parabens.1

What types of products contain parabens?

Parabens are preservatives commonly found in many different categories of personal care products. Preservatives inhibit microbial growth and are necessary ingredients in water-based products. The 4 most common parabens used in personal care products are methylparaben, ethylparaben, propylparaben, and butylparaben.1 Parabens are metabolized to 4-hydroxybenzoic acid and are excreted in urine. When parabens are applied topically, there is minimal penetration through intact human skin.2 In the United States, parabens are allowed as preservatives in cosmetics at concentrations up to 0.4% when used alone or up to 0.8% when used in combination with other parabens.3

Consumers are exposed to parabens in a wide variety of personal care products. The Contact Allergen Management Program (CAMP) is a system owned and managed by the ACDS that typically is used to generate lists of safe personal care products for patients and also can be queried for the presence of individual chemicals in products. According to a 2018 query of the CAMP, parabens were found in 19% of all products.1 A more recent query of CAMP (http://www.contactderm.org/resources/acds-camp) in March 2019 showed parabens were present in 39.3% of makeup products, especially in eye products, foundations, and concealers; parabens also were found in 34% of moisturizers, 11.5% of soaps, and 19% of sunscreens. Notably, 14.8% of prescription topical steroids listed in the CAMP contained a paraben. Another method for evaluating chemical contents of personal care products is a review of the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program, a US Food and Drug Administration–based registry for cosmetic products. Survey data from the Voluntary Cosmetic Registration Program in 2018 documented methylparaben in 11,626 formulations.4 Other parabens included propylparaben (8885 products), butylparaben (3915 products), and ethylparaben (3860 products). Parabens were reported more frequently in leave-on rather than rinse-off products.4

In medications, parabens are recommended at concentrations of no more than 0.1%.1 Fransway et al1 compiled a list of medications that contain parabens, including commonly prescribed dermatologic topical medications such as corticosteroids, several acne preparations, eflornithine, fluorouracil, hydroquinone, imiquimod, urea, and sertaconazole. Oral and parenteral medications including local anesthetics and corticosteroids also may contain parabens.

Consumers also may be exposed to parabens through foodstuffs. Methylparaben and propylparaben have been classified as generally recognized as safe in foods by the US Food and Drug Administration.5 The acceptable daily intake of parabens in food is 0 to 10 mg/kg of body weight,1 and the estimated dietary intake for a typical adult is 307 mg/kg of body weight daily.6 Several studies on paraben content in foodstuffs have confirmed their presence in both natural and processed foods.1,6 Systemic contact dermatitis caused by ingestion of parabens is rare. In general, individuals with positive patch test reactions to parabens should not routinely avoid them in foods or oral medications,1 but they should, of course, be avoided in topical medications.

What is the rate of ACD with parabens?

One of the main reasons that parabens were designated as the ACDS nonallergen of the year is the very low rate of ACD associated with parabens. The North American Contact Dermatitis Group, a research group with members in the United States and Canada, reported a 0.6% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 12%,7 which closely compares with a 0.8% positive reaction rate when patch testing with paraben mix 16% using the Mayo Clinic standard series.8 From the standpoint of ACD, this very low patch test reaction rate makes parabens one of the safest preservative options for use in cosmetic products.

Are there health risks associated with parabens?

The paraben controversy in the scientific literature and in the lay press centers around potential health risks and endocrine disruption. We will focus on the conversation regarding parabens and the risk for endocrine disruption and association with breast cancer.

Parabens have been reported to have estrogenic effects; however, the bulk of the data is limited to in vitro and animal studies, with less evidence of endocrine disruption in humans.2 In vitro studies have demonstrated that the estrogenic potency of parabens is much less than that of estrogen. In one study, parabens were shown to be 10,000-fold less potent than 17β-estradiol9; in a separate study, they had a maximum potency of only 1/4000 that of estrogen.10 Additionally, an in vitro study showed varying ability for parabens to bind estrogen receptors, with a greater ability to bind with longer alkyl side chains.11 The result is decreased or increased estrogen activity, dependent on side chain length and type of receptor.2 Finally, some studies add conflicting results that parabens may actually create an antiestrogenic effect in human breast cancer cells.12 From the standpoint of estrogen mimicry, there are no known studies in humans confirming harmful effects associated with paraben exposure.

The reported association between parabens and breast cancer is closely related to their theoretical estrogenic effects. The conversation regarding parabens and breast cancer has been fueled by the identification of parabens in human breast tumors and their presence in concentrations similar to what is needed to stimulate in vitro breast cancer cells.2 The existing data do not confirm causation. An association with parabens in topical axillary personal care products has been theorized but not confirmed; for example, it was shown that paraben levels were highest in the axillary region of breast cancer tissue, including women who had never used deodorant. It was concluded that the presence of axillary parabens was due to sources other than topical axillary personal care products.13 Another study confirmed there was not an increased risk for breast cancer in patients who applied personal care products to the axillary area within an hour of shaving.14 The existing data do not support topical paraben exposure as a risk for breast cancer.

Final Thoughts